1. Introduction and Main Contributions

Recently published work on

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) introduces a single smooth, unit–norm, future–directed timelike field

whose integral curves define a preferred temporal flow and induce a foliation

with an emergent Lorentzian metric

[

9,

82,

83,

115]. On stabilized domains (defined below), this structure provides: (i) causal cones and an ADM–like

decomposition, (ii) a relational Hilbert space

supporting Schrödinger evolution in intrinsic time

[

38,

41], and (iii) a covariant stress–energy tensor

derived from the CFT action [

91].

The purpose of the present paper is to demonstrate that, within this background–independent framework, one can construct a rigorous and self–contained account of

mass,

matter, and an emergent Abelian

gauge sector, together with the familiar physical constants

, all arising as

derived geometric invariants rather than postulated inputs [

10,

116].

Standing Conventions

We work in dimensions with signature , set units so that the emergent light speed is , and keep the emergent action unit explicit. Greek indices run over spacetime components; spatial operations are performed with the projector ; denotes the induced spatial covariant derivative on a leaf. Unless stated otherwise, fields are smooth and decay so that boundary terms vanish on .

Stabilized Domains

A spacetime region is

stabilized if

is smooth, strictly timelike with

, and its gradients are bounded so that (a) the foliation

is well defined, (b) the field equations are hyperbolic with respect to the induced time, and (c) the Peierls bracket reduces to canonical commutators on

up to controllable

corrections [

38,

95]. All results below are stated and proved on stabilized domains.

On Local Lorentz Symmetry

The chronon field selects a unit timelike direction and thus a preferred foliation in vacuum. As a result,

local Lorentz symmetry is spontaneously broken even though the action is written in a Lorentz–covariant and diffeomorphism–invariant form. We therefore regard the framework as an æther–like effective field theory on stabilized domains and explicitly track the induced preferred–frame operators and propagation effects [

72,

73]. For clarity, we use “chronon” to denote the unit–norm timelike sector introduced here, while emphasizing that its structure is closely analogous to Einstein–æther models. In the infrared, these deformations are parametrically suppressed and compatible with existing constraints (PPN preferred–frame bounds [

120,

121], gravitational–wave equal–speed tests [

1,

2], and birefringence limits [

31,

79,

85]), so that the dynamics reduce to Einstein–Maxwell up to small, controlled corrections. Radiative corrections cannot destabilize this suppression, since the stabilized domain symmetry prevents the regeneration of unsuppressed Lorentz–violating operators at low energies. We map the leading operators to standard test frameworks (SME/PPN) [

78,

79] and state parameter priors accordingly; any phenomenology beyond these bounds is confined to strongly curved or topological regions where the foliation is highly distorted. For completeness, we also outline in Appendix N a broader interpretation—the

Co-Moving Concealment Mechanism—in which all matter and observers emerge from the chronon foliation itself, so that local Lorentz violation is fundamentally present but operationally concealed. In the present work, however, we adopt the more conservative EFT perspective, ensuring consistency with established experimental tests while leaving the deeper emergent interpretation for future development.

On Emergent Metrics and Causal Structure

The chronon sector deforms propagation operators in a manner that can be usefully recast in terms of an induced or “emergent” effective metric. In this sense the chronon may be viewed as generating a secondary causal structure, an idea we regard as a promising avenue for future work. In the present paper, however, we restrict to the more conservative interpretation: an æther-like effective field theory defined on the background spacetime metric , with chronon-induced operators systematically mapped to SME/PPN test frameworks. This ensures that the claims made in this paper remain within the well-established EFT regime, while a rigorous treatment of chronon-induced emergent geometry is deferred to subsequent studies.

1.1. Main Results

- (C1)

Covariant local mass/energy density. Definition and positivity of

connects to the dominant energy condition [

64,

115].

- (C2)

GR as an IR fixed point with controlled deviations. Effective field theory reasoning follows [

73,

116], with constraints informed by PPN tests [

121].

- (C3)

Existence of finite–energy solitons. Existence and stability of topological solitons connect to Skyrme-type and Derrick arguments [

39,

86,

105].

- (C4)

Spin–statistics for solitons via FR/Berry holonomy. The Finkelstein–Rubinstein mechanism and Berry phase arguments [

20,

48] underpin the soliton spin–statistics connection.

- (C5)

Emergent Abelian gauge sector from chronon holonomy. Parallel transport and holonomy yielding emergent gauge fields relates to work on gauge connections and Berry bundles [

89,

123].

- (C6)

Emergent fundamental constants and parameter constraints. The idea that

G,

ℏ,

e,

c may emerge rather than be postulated resonates with Sakharov’s induced gravity [

101] and effective action derivations in quantum field theory [

125].

1.2. Intuition and Roadmap: From Chronon Flow to Coherent Quantized Geometry

Starting Picture

Envision the chronon field

as a locally defined “clock vector” that threads spacetime, picking out at each point a preferred timelike direction. Imposing the unit–norm constraint

accomplishes two tasks simultaneously: it fixes the intrinsic “rate” of this local clock (no arbitrary rescalings) and cleanly defines the orthogonal complement

. Geometrically, this splits the tangent space into a one–dimensional time direction spanned by

and a three–dimensional space orthogonal to it. Integrating

yields a foliation of spacetime into spatial leaves

, with

measuring intrinsic time along the chronon flow. Observers comoving with

measure the local energy density

and we call a region

stabilized when

and fluctuations of

remain bounded. A stabilized domain is therefore a portion of spacetime with a coherent local clock and well–behaved spatial slices—the precondition for causal and quantum structure to emerge.

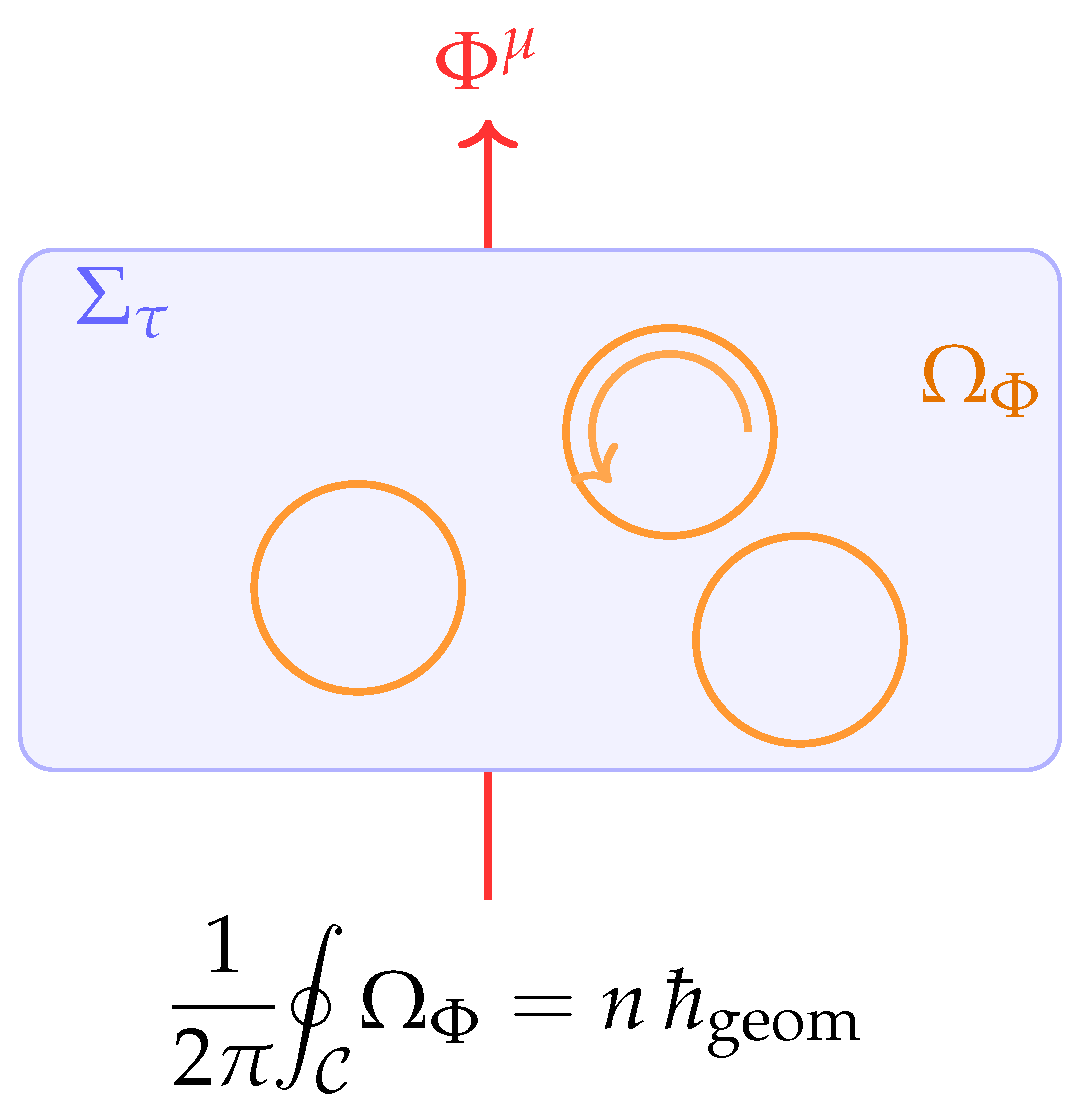

Why Compact Holonomy Is Natural

Within a stabilized domain, parallel transport around a closed loop rotates any spatial vector by an angle in the plane orthogonal to . Because is unit timelike, the induced metric on is positive definite, so these rotations form a compact group. The smallest such group is the circle : transporting an internal pointer around C accumulates a phase . This geometric phase is the origin of the emergent Abelian gauge structure: the internal phase of acts as a compact fiber coordinate, whose holonomy defines a circle bundle over .

From Phases to Gauge Fields

To keep track of these rotations, one assigns to each infinitesimal path a phase factor and requires consistency under composition. Locally, this data is encoded by a one–form connection A, whose line integral around C gives the accumulated phase . The curvature two–form then measures the infinitesimal twist per unit area: the “vorticity” of the chronon field on the leaves. In the continuum limit, holonomy consistency enforces Maxwell–like equations for A on the emergent metric , linking the chronon kinematics to classical electrodynamics.

Why the Unit Norm Really Matters

Keeping is not merely aesthetic. It ensures that: (i) the projector is a genuine projector onto , (ii) the holonomy group remains compact (rotations, not boosts), guaranteeing a circle fiber and phase quantization, and (iii) amplitude and phase decouple cleanly—norm fluctuations remain geometric rather than gauge. This separation underlies flux quantization, stability, and the emergence of a universal action quantum .

The 2 Twist: Root of Spin, Charge, and Quantization

Because the fiber is a circle, winding the chronon phase by around a loop cannot be undone continuously: it defines a topological sector, . Spatial textures of carrying this winding behave as solitons with integer charge and half–integer spin. A full twist in the temporal phase of yields the Finkelstein–Rubinstein sign change responsible for spin– statistics, while the same twist viewed in the spatial projection gives the quantized holonomy identified with electric charge. The action increment for each completed twist, , thus encodes quantization itself. Spin, charge, and the quantum of action all stem from this single geometric phase twist of the chronon manifold.

Interactions as Coherence Enforcement

When multiple solitons coexist, their temporal phases must remain coherent to preserve causal consistency. The emergent gauge field plays precisely this role: it mediates synchronization of chronon phases across space, enforcing global temporal coherence. Electromagnetic and gravitational interactions thus represent collective coherence modes of the chronon condensate—not external forces, but the dynamical self–organization of the underlying time–flow field.

Roadmap

The technical development of this paper mirrors this geometric intuition:

Kinematics from the clock: impose , construct the induced metric and define stabilized domains through .

Holonomy structure: follow parallel transport on and establish the compact bundle structure.

Gauge dynamics: identify A and F as local curvature data and derive Maxwell–type equations for A on .

Topological matter: classify solitons by integer winding, derive flux quantization and spin–charge correspondence.

Emergent constants: show that ℏ, e, G, and c arise as curvature invariants, fixed by the stabilized chronon phase.

Unified picture: Section 9 develops the synthesis: spin, charge, quantization, and interaction as facets of one

symplectic twist in the chronon field.

Technical Notes

The foliation gives a natural reduction of the frame bundle on ; the connection one–form arises as the leafwise Berry connection for the chronon fiber; compactness and the unit normalization guarantee that the Čech cocycles land in and that the resulting Abelian sector is globally well defined.

Analogy

Think of the chronon medium as a fluid with an internal compass. The unit norm fixes the clock; the compass’s angle is the gauge phase. Carrying the compass around a loop twists it by an amount that depends only on what the fluid is doing inside the loop. That twist is the Wilson phase, its density is F, and its topological windings are the solitons. The rest of the paper turns this picture into geometry and equations.

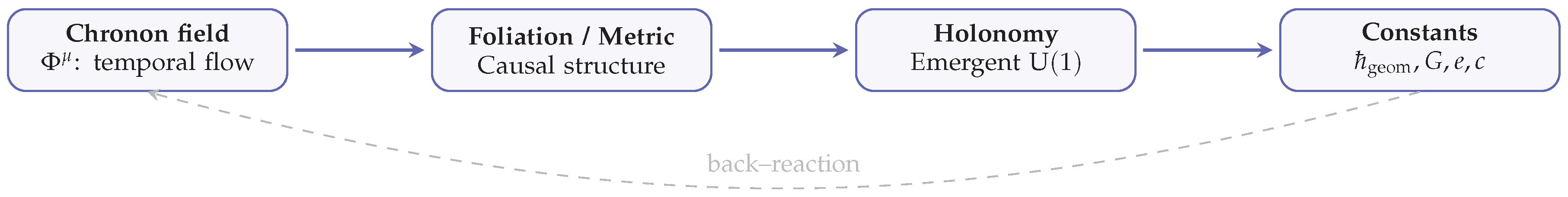

Figure 1.

Schematic flow of Chronon Field Theory. The pre–geometric chronon field induces foliation and metric structure; its holonomy produces an emergent sector, and the resulting geometric invariants yield the physical constants .

Figure 1.

Schematic flow of Chronon Field Theory. The pre–geometric chronon field induces foliation and metric structure; its holonomy produces an emergent sector, and the resulting geometric invariants yield the physical constants .

2. Background and Setup

2.1. Chronon Field, Foliation, and Emergent Geometry

We postulate a smooth, unit timelike vector field

on a four-dimensional spacetime manifold

, satisfying

The integral curves of

define a preferred time function

(unique up to affine reparameterization) and a foliation by Cauchy hypersurfaces

[

33,

54,

115]. The orthogonal projector onto the tangent bundle of each leaf is

which is a positive-definite metric on

[

59,

115]. The Levi–Civita connection ∇ of

g induces a

leafwise covariant derivative on tensor fields

X by

Kinematic invariants of the congruence

are defined as

and obey the standard Raychaudhuri/Ehlers relations for timelike congruences [

44,

100,

115]. The extrinsic curvature of the leaves is

, with the decomposition

[

59]. Throughout we work on

stabilized domains: regions where

is smooth, strictly timelike, and

is uniformly bounded so that (i) the foliation exists, (ii) the Cauchy problem for the field equations is well posed in the intrinsic time

, and (iii) equal-time operator algebras on

are well defined up to controllable

corrections [

33,

38,

95].

Role of the Unit–Norm Constraint in the Abelian Sector

Throughout Paper I we impose

on stabilized domains. This normalization has three indispensable consequences for the emergence of the

sector. First, it fixes the chronon flow as a unit timelike congruence, so the orthogonal projector

is a true projector and the induced leaf metric

is Riemannian [

59,

115]. In particular,

is then the physical energy density in the comoving frame, providing a clean, scale–independent criterion for stabilized domains. Second, restricting parallel transport to

preserves

h and yields a compact residual isotropy

on the internal fiber, so that holonomy produces a genuine circle bundle rather than a noncompact

symmetry; this compactness underlies flux quantization and the integer winding of solitonic defects (

) [

89,

123]. Third, the unit baseline separates angular (phase) and radial (amplitude) degrees of freedom: the former define the emergent

connection and Berry–like holonomy on leaves, while the latter encode norm–restoring fluctuations of

without contaminating gauge phases [

20]. If the norm were allowed to drift, the projector would cease to be idempotent without ad hoc rescaling,

would pick up spurious conformal factors, and leafwise holonomy would no longer be guaranteed to land in a compact Abelian group, obstructing the

construction. Related unit-timelike constructions appear in Einstein–æther–type effective theories [

72,

73].

2.2. Dynamics and Stress Tensor

We take a local, diffeomorphism-invariant CFT action for

on

truncated at mass-dimension

(parity-even sector):

Here

is the Ricci tensor, and

enforces the unit-norm constraint (one may alternatively use a steep potential). The structure mirrors familiar unit-timelike vector EFTs (e.g., Einstein–æther) while remaining background independent in our setting [

72,

73]. Variation with respect to

yields the Euler–Lagrange equations

with

fixed by contracting (

6) with

and using

. The symmetric (Hilbert) stress tensor is defined by

which is conserved on shell,

, by diffeomorphism invariance [

115]. The

covariant local mass/energy density measured by comoving observers is

and the leafwise total (rest) mass is

, where the volume element is induced by

[

115]. Positivity and conservation properties of

are established in §4.

2.3. Geometric Action Unit and Operator Algebra

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), the universal action scale—identified with Planck’s constant—does not arise from coarse–graining or statistical variance, but from the intrinsic

curvature geometry of the chronon manifold itself [

13,

51,

82]. The fundamental symplectic structure of the theory is encoded in the chronon two–form curvature

whose scalar contraction

defines the intrinsic curvature density of the temporal field [

77,

88]. On stabilized domains this curvature becomes uniform, and its invariant integral furnishes the natural unit of action:

where

is a dimensionless matching constant fixed by normalization,

is the chronon length scale, and

denotes the stabilized curvature average. Equation (

10) expresses

as a universal curvature invariant: it is the symplectic area of a fundamental curvature cell of the chronon field. Once the curvature condenses into a stable phase,

becomes spatially constant and numerically identical to the observed Planck constant

ℏ [

83,

90].

The corresponding covariant path measure is therefore

in which the weighting factor

originates directly from the phase of the curvature two–form rather than from ensemble averaging [

47,

117]. The geometric constant

thus defines the fundamental symplectic volume element of the chronon manifold.

Kinematically, Poisson brackets of gauge–invariant functionals

are defined on each stabilized leaf

by contraction with the inverse of the symplectic form

[

38,

42,

95]:

Quantization promotes these to operators on the leaf Hilbert space

with commutator

so that the canonical algebra is recovered in the strong–stabilization limit

[

13,

51]. Together with the energy–density definition (21), this establishes the geometric foundation of the uncertainty relations and of all quantum corrections developed in

Section 7.

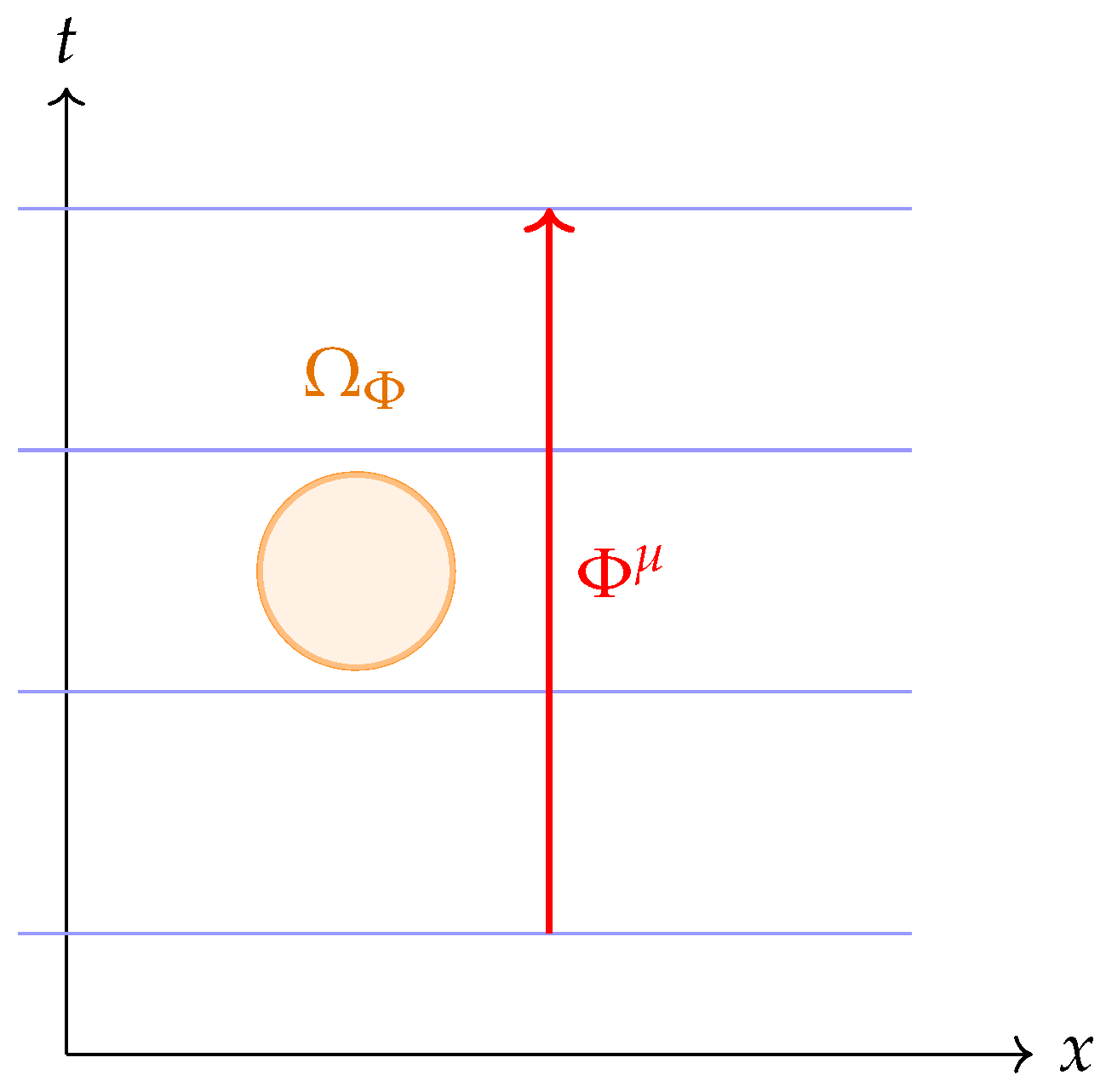

Figure 2.

Chronon curvature geometry on a stabilized leaf . The unit timelike flow defines spatial slices, while the curvature two–form endows each leaf with a symplectic area element whose invariant magnitude fixes the geometric Planck constant .

Figure 2.

Chronon curvature geometry on a stabilized leaf . The unit timelike flow defines spatial slices, while the curvature two–form endows each leaf with a symplectic area element whose invariant magnitude fixes the geometric Planck constant .

2.4. EFT and Power Counting

Beyond the two-derivative truncation, the low-energy action on stabilized domains reads

where

are æther-like two-derivative invariants built from

(shear, expansion, acceleration) and

are higher-derivative operators. On stabilized leaves with small

,

are naturally suppressed, while

scale as

. This organizes deviations from GR in a controlled expansion [

29,

43,

73,

116].

3. Emergent from Chronon Holonomy

3.1. Holonomy Phase and Connection

We work on a stabilized domain (cf. §2.1). Parallel transport of the unit timelike field

along smooth curves

(with Levi–Civita connection of

g) induces a rotation in the two–plane orthogonal to

. This defines a principal

bundle over each leaf [

51,

77,

88]. Locally on a chart

, choose a smooth section and let

be the associated

holonomy phase. We then define a spacetime one–form whose leafwise pullback equals the leaf connection:

A change of section shifts

for some smooth

, hence

and the curvature two–form is the exterior derivative

which coincides with the holonomy two–form of the induced

bundle on each leaf [

77,

89,

123]. In covariant notation we write

and raise indices with the emergent metric

[

115]. A geometric phase interpretation of

aligns with Berry’s phase in adiabatic settings [

20] (here realized leafwise by the chronon fiber).

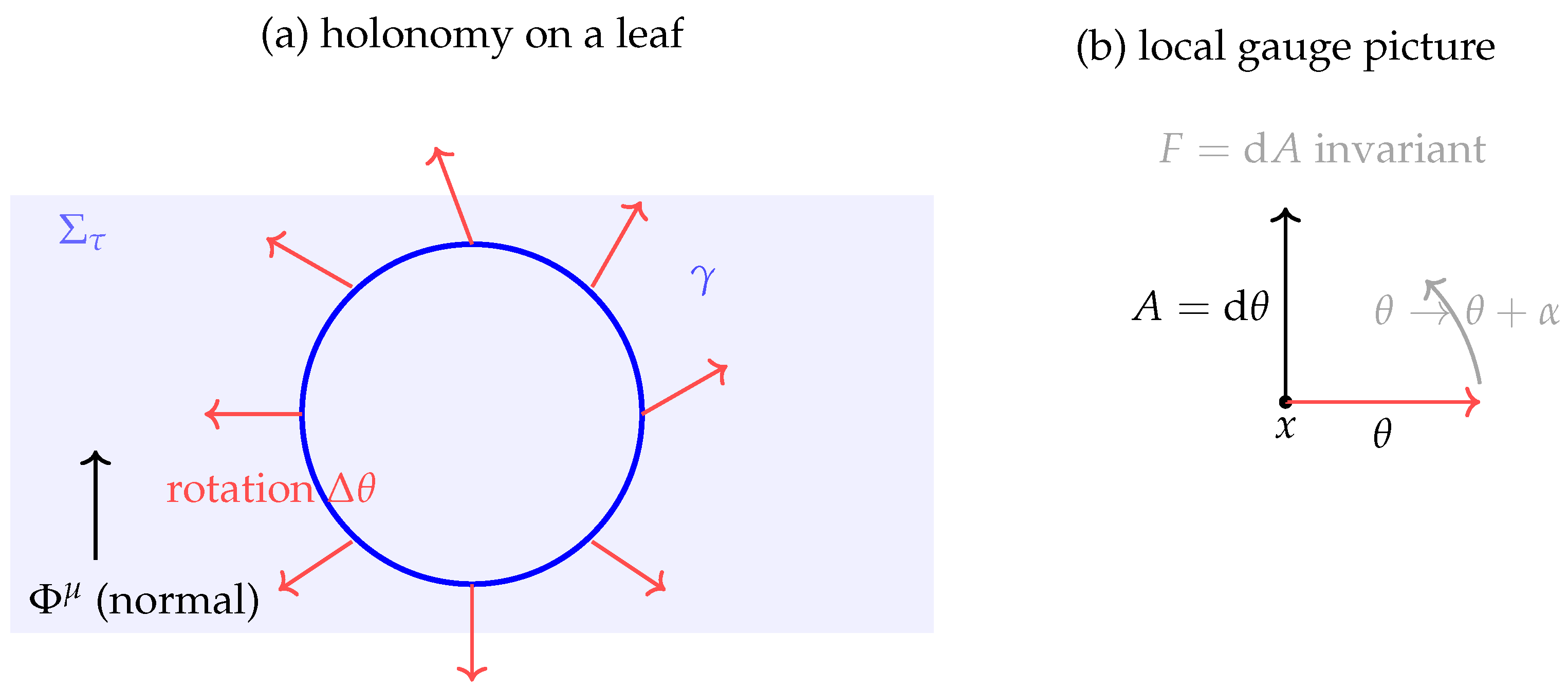

Figure 3.

Emergent from chronon holonomy. (a) On a stabilized spatial leaf , transporting the local orthonormal frame once around a closed loop produces a net rotation of the transverse basis vectors by an angle . This angle records the holonomy of the connection induced by the chronon flow, and defines a compact phase variable identified modulo . The normal vector indicates the timelike direction singled out by the chronon field. (b) In the local gauge description, the rotation angle serves as a coordinate on the internal fiber. Its derivative acts as the Abelian gauge potential, and a gauge shift changes A by a pure gradient while leaving the curvature invariant. In this way, the geometric holonomy of chronon transport is reinterpreted as an emergent electromagnetic gauge symmetry.

Figure 3.

Emergent from chronon holonomy. (a) On a stabilized spatial leaf , transporting the local orthonormal frame once around a closed loop produces a net rotation of the transverse basis vectors by an angle . This angle records the holonomy of the connection induced by the chronon flow, and defines a compact phase variable identified modulo . The normal vector indicates the timelike direction singled out by the chronon field. (b) In the local gauge description, the rotation angle serves as a coordinate on the internal fiber. Its derivative acts as the Abelian gauge potential, and a gauge shift changes A by a pure gradient while leaving the curvature invariant. In this way, the geometric holonomy of chronon transport is reinterpreted as an emergent electromagnetic gauge symmetry.

3.2. Gauge Invariance and Maxwell Limit

Under

, the curvature

is invariant. In the canonical normalization (after

), the minimal diffeomorphism– and gauge–invariant action for the Abelian sector on

is

whose variation with respect to

yields the source–free Maxwell equations on the emergent geometry:

the latter being the Bianchi identity (

) [

70,

115]. Coupling to matter proceeds by minimal substitution on the relevant bundles (e.g. the soliton bundle of §5), giving

with

as the Noether current conservation law for the

gauge symmetry [

91,

97]. In the infrared, the dynamics are Maxwellian with two transverse polarizations; the photon corresponds to a Goldstone–like fluctuation of the internal time–phase encoded by

[

10].

Reference Maxwell Limit on Stabilized Domains

A precise EFT statement quantifying when (

17) governs the dynamics is given in Appendix L, Proposition A1. On twist–free, slowly varying backgrounds

(“stabilized domains”), one finds

with deviations organized by the small parameters

,

, and

, as well as any æther–like couplings

:

The leading non–Maxwell operators in

are æther–like parity–even contractions

and

, and higher–derivative/curvature terms such as

and

(see (2)); their coefficients are suppressed by

,

,

, and

, respectively. Hence birefringence and anisotropy effects are parametrically small on stabilized domains (consistent with photon–sector bounds, cf. [

78,

79]).

4. Covariant Local Mass/Energy Density

A central requirement for any background–independent field theory that aims to reproduce relativistic matter and interactions is a covariant and observer–independent notion of mass/energy density [

64,

115]. In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), this role is played by the scalar quantity

defined pointwise on stabilized domains. Equation (21) has three immediate virtues: (i) it is manifestly covariant, depending only on the stress tensor

and the dynamical timelike unit vector

; (ii) it reduces to the conventional energy density

in the comoving frame aligned with

[

80]; and (iii) it is intrinsically nonnegative and conserved under mild regularity conditions, as we prove below.

Assumption 4.1 (Regular domain). Solutions of the CFT field equations admit stabilized leaves

with induced metric

and smooth stress tensor

. Moreover, the Lagrangian density is invariant under flow along

(quasi–stationarity):

on the domain.

The quasi–stationarity condition expresses the fact that translations along the chronon flow

act as an isometry of the stabilized domain, ensuring that the associated Noether current [

91] coincides with the natural energy current. This parallels the role of Killing vectors in conventional general relativity [

115], but here arises dynamically from the unit–norm constraint and stabilization.

theorem 4.2 (Positivity and conservation of

)

. Let Theorem 4.1 hold and assume the induced dominant energy condition (DEC), i.e.

Then on any stabilized leaf :

-

(i)

;

-

(ii)

the energy current is conserved, ;

-

(iii)

-

consequently, the total mass

is finite for finite–energy data and independent of the leaf label τ.

Proof. (i) Positivity. Since

is a future–directed unit timelike vector, the induced DEC immediately yields

establishing

pointwise [

64,

115].

(ii) Conservation. Diffeomorphism invariance of the CFT action ensures

[

91]. Contracting with

gives

The first term vanishes on shell. The second term vanishes under Theorem 4.1: invariance under

–flow identifies

as the Noether current associated to translations along

, hence conserved [

91,

115].

(iii) Leaf–independence of . Integrate

over the spacetime slab bounded by two leaves

and

and apply the divergence theorem [

54]:

Here

is the unit normal to the integration surfaces, and

denotes the timelike boundary of the slab. On

,

, so the flux reduces to

as in (

22). The boundary term over

vanishes for finite–energy configurations by the assumed decay of fields. Thus

proving constancy of the total mass across leaves. □

Remarks

The functional

furnishes a covariant, background–independent definition of inertial and gravitational mass in CFT, reducing to the ADM mass [

9] in asymptotically flat settings where

aligns with the asymptotic time translation.

Unlike canonical Hamiltonian formulations, no reference to a preferred coordinate system is required: the chronon flow supplies the intrinsic time direction and defines the foliation .

The conservation of ensures stability of solitonic excitations and provides the basis for identifying the rest mass in topological sectors (Section 5).

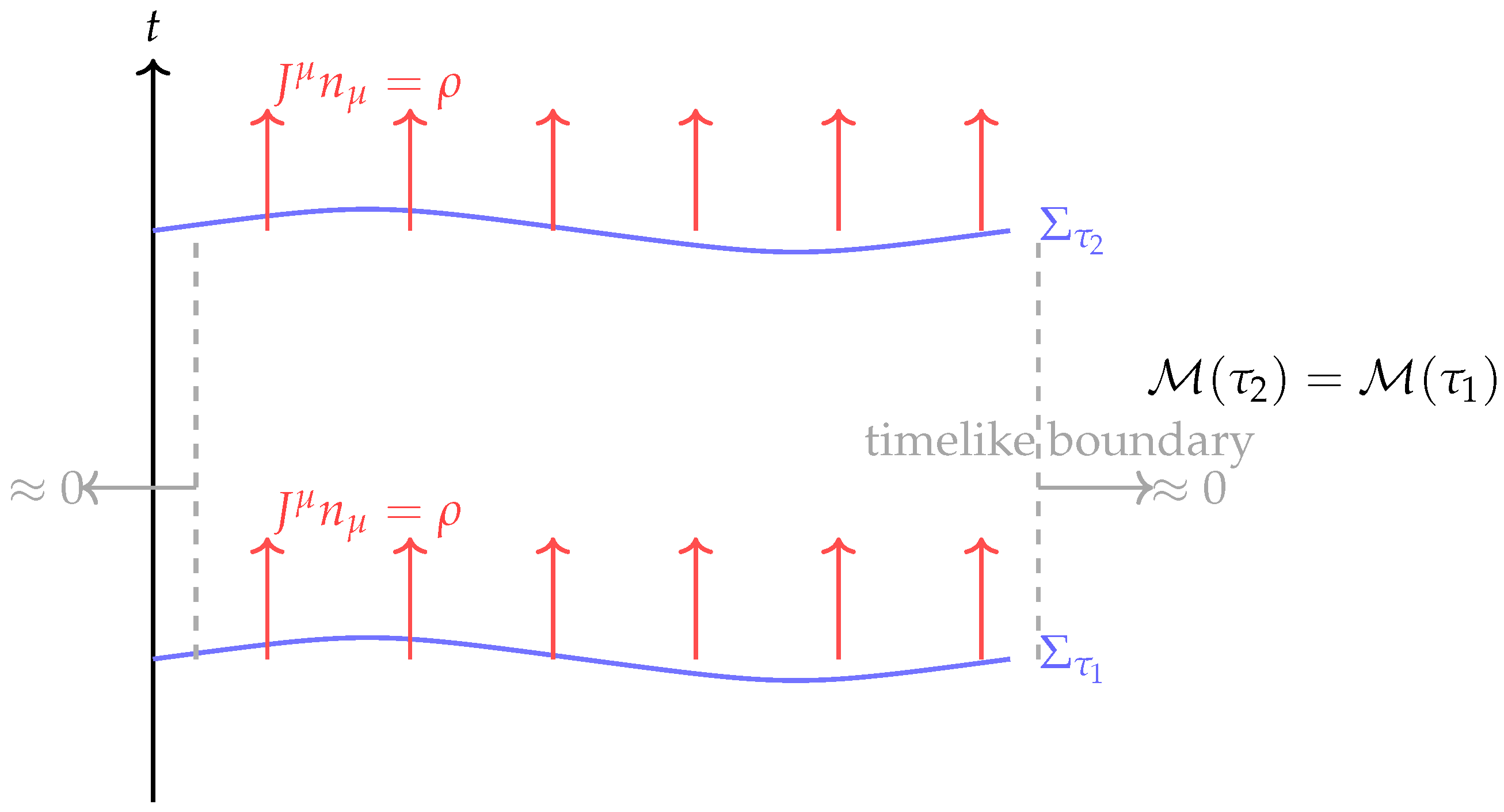

Figure 4.

Covariant mass and conserved flux in Chronon Field Theory. The diagram shows a spacetime slab bounded by two stabilized spatial leaves and (blue curves) and vertical timelike boundaries (dashed gray lines). The energy current flows across the leaves with flux density (red arrows). Because the flux through and is equal, and because finite–energy configurations produce negligible flux through the timelike boundaries, the total mass functional is conserved between leaves: . This figure provides a geometric visualization of the conservation law proved in Appendix A: the red vertical arrows depict the flow of energy density across the slices, while the gray side arrows vanish, ensuring that the integrated mass remains constant across time.

Figure 4.

Covariant mass and conserved flux in Chronon Field Theory. The diagram shows a spacetime slab bounded by two stabilized spatial leaves and (blue curves) and vertical timelike boundaries (dashed gray lines). The energy current flows across the leaves with flux density (red arrows). Because the flux through and is equal, and because finite–energy configurations produce negligible flux through the timelike boundaries, the total mass functional is conserved between leaves: . This figure provides a geometric visualization of the conservation law proved in Appendix A: the red vertical arrows depict the flow of energy density across the slices, while the gray side arrows vanish, ensuring that the integrated mass remains constant across time.

5. Solitonic Matter: Existence and Properties

In Chronon Field Theory, localized matter excitations are not introduced as independent quantized fields but arise as

topologically stable solitons of the chronon field

. These solitons correspond to nontrivial elements of the homotopy group

[

62], ensuring stability under smooth deformations. In this section we define the relevant configuration and moduli spaces, establish existence of finite–energy minimizers in the nontrivial sector

, and outline their inertial properties and quantization.

Functional Setting

Throughout this section we work in the Sobolev class at fixed topological degree w, with the Skyrme-type energy described below. The precise function spaces, constraints, and the existence result for the sector are summarized in Appendix M.

5.1. Topological Sectors and Configuration Spaces

To define solitonic sectors we impose asymptotic boundary conditions. On each stabilized leaf

, we require

so that spatial infinity is compactified to a point. This compactification identifies

, and the unit–norm constraint

restricts the target space of

to

. Thus any static configuration defines a continuous map

Such maps are classified by the winding number

which serves as a topological charge. Physically,

w measures how many times the spatial slice wraps around the unit hyperboloid of admissible chronon vectors.

Configuration and Moduli Spaces

For each

, define the configuration space

i.e. smooth finite–energy chronon fields with topological charge

w. The corresponding moduli space is

where

denotes diffeomorphisms connected to the identity and

denotes residual internal symmetries preserving the unit–norm constraint.

parametrizes physically inequivalent solitons [

86].

By the existence result established in Appendix M for , we may fix a minimizer in the admissible class and analyze its properties.

theorem 5.1 (Existence of a finite–energy minimizer for

).

Let the CFT couplings satisfy the coercivity and regularity conditions of Assumption 4.1, and impose boundary condition (23). Then the energy functional

admits a smooth finite–energy minimizer in the topological class . This minimizer is stable against small perturbations.

Strategy. The proof follows the direct method in the calculus of variations [

46,

109]:

- (a)

Coercivity. Gradient and curvature terms in the CFT action provide a coercive bound , preventing loss of compactness.

- (b)

Lower semicontinuity. The integrand of (

26) is convex in

, implying weak lower semicontinuity of

E on

.

- (c)

Compactness. By Rellich’s theorem, minimizing sequences admit weakly convergent subsequences modulo spatial translations and gauge rotations [

46].

- (d)

Topological constraint. The winding number

w is preserved under weak convergence in

, ensuring the limit lies in

[

62].

- (e)

Regularity. Standard elliptic estimates upgrade weak minimizers to smooth solutions of the Euler–Lagrange equations [

55].

Positivity of

(Theorem 4.2) ensures finite energy, while the second variation of

E is nonnegative in directions tangent to

, guaranteeing stability under small perturbations [

86]. □

5.2. Rest Mass and Collective Modes

The rest mass of the fundamental soliton is defined by evaluating the conserved mass functional (Section 4) on the

minimizer:

This provides the intrinsic inertial/gravitational mass of the soliton, independent of the foliation label

.

Collective Coordinates

The moduli space

admits low–energy deformations corresponding to translations, global

phase rotations, and internal isorotations. Quantization of these modes proceeds via the collective–coordinate method [

7,

86]: one promotes the moduli parameters to slowly varying quantum degrees of freedom, substitutes into the action, and derives an effective Hamiltonian. For a single internal rotor with moment of inertia

I, the leading energy splitting scales as

This scaling parallels that of Skyrmion quantization in nuclear physics [

7,

105], but here

is the emergent action unit derived from chronon microdynamics (Appendix L).

Figure 5.

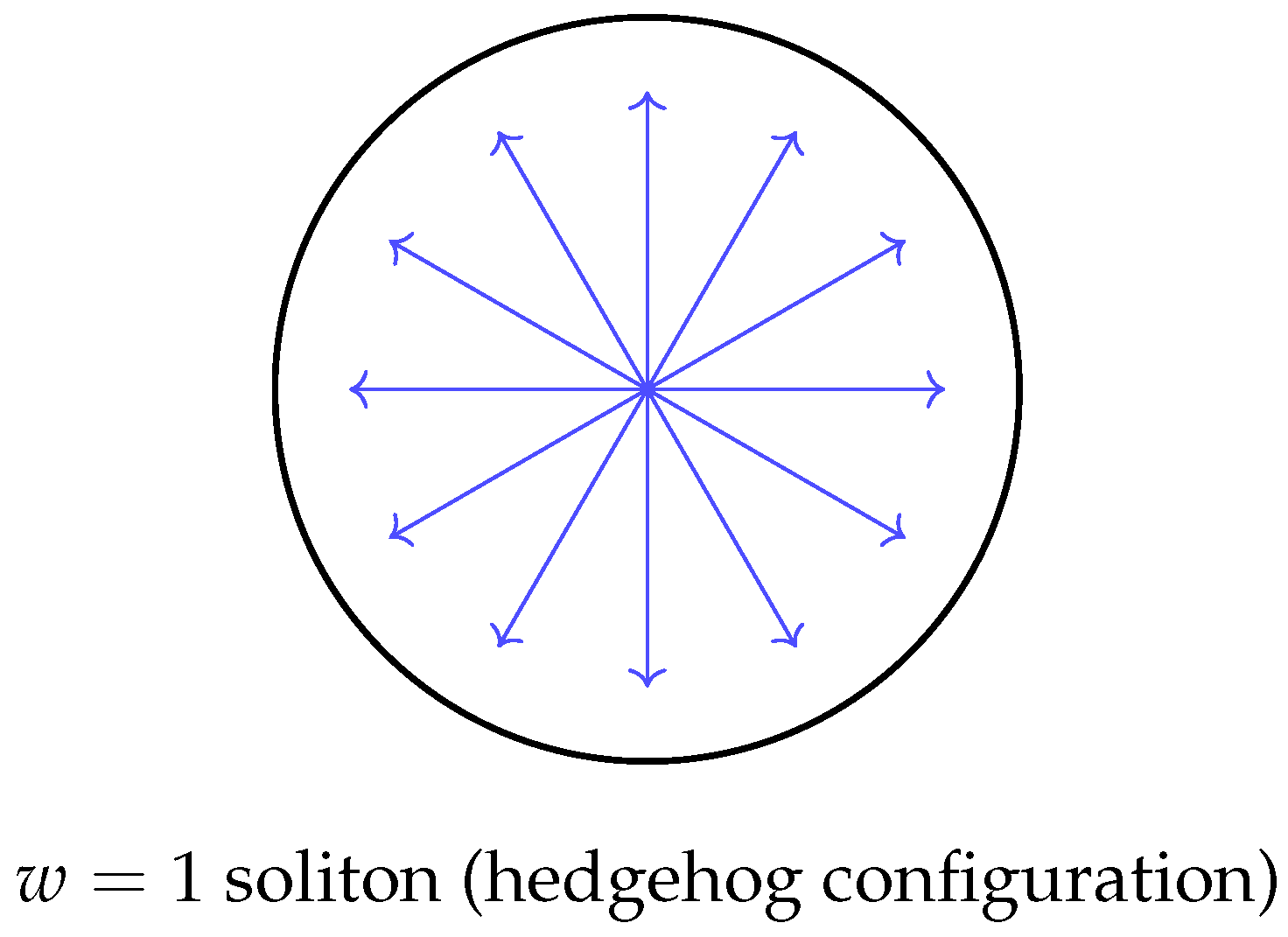

Schematic illustration of a unit–charge () soliton. The chronon field is constrained to have unit norm and thus maps spatial infinity to a fixed point on the internal target space . A representative configuration is shown as a hedgehog map, where spatial directions (arrows radiating outward) are aligned with internal directions of . As one traverses the enclosing in real space, the field winds exactly once around a great circle of , realizing topological degree one. This winding number protects the soliton from decay into the trivial vacuum. The hedgehog pattern is a canonical visualization of how topological charge is encoded in the spatial profile of the chronon field.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of a unit–charge () soliton. The chronon field is constrained to have unit norm and thus maps spatial infinity to a fixed point on the internal target space . A representative configuration is shown as a hedgehog map, where spatial directions (arrows radiating outward) are aligned with internal directions of . As one traverses the enclosing in real space, the field winds exactly once around a great circle of , realizing topological degree one. This winding number protects the soliton from decay into the trivial vacuum. The hedgehog pattern is a canonical visualization of how topological charge is encoded in the spatial profile of the chronon field.

Remark (Uniqueness and Spectrum in )

Under the hypotheses of Theorem 5.1 the

sector admits at least one smooth, finite–energy minimizer. In the minimal CFT (two–derivative, stabilized domain) we expect this minimizer to be

unique up to symmetries [

86]: translations in

, a global

phase, and (only if the profile is not spherically symmetric) spatial rotations. Formally, let

denote the second–variation (Hessian) operator around the minimizer

; then the Morse index is zero and

with

the global

zero mode and

the generators of infinitesimal spatial rotations. Quantization of the corresponding collective coordinates, together with low–lying vibrational modes (eigenfunctions of

with small positive eigenvalues), produces an excitation tower

within the

sector [

7,

86]; all such states carry the same topological/electric charge

. Multiple local minima (“isomers”) in

can exist for special choices of couplings

; these would constitute distinct solitonic species sharing

and charge

but differing in mass and internal structure.

Summary

The existence of stable solitons, their identification with localized lumps of conserved mass , and the quantization of their collective modes together establish a concrete mechanism by which fermionic matter arises in CFT. The spin–statistics connection will be demonstrated in Section 6, completing the interpretation of solitons as particle–like excitations with spin– and Fermi–Dirac statistics.

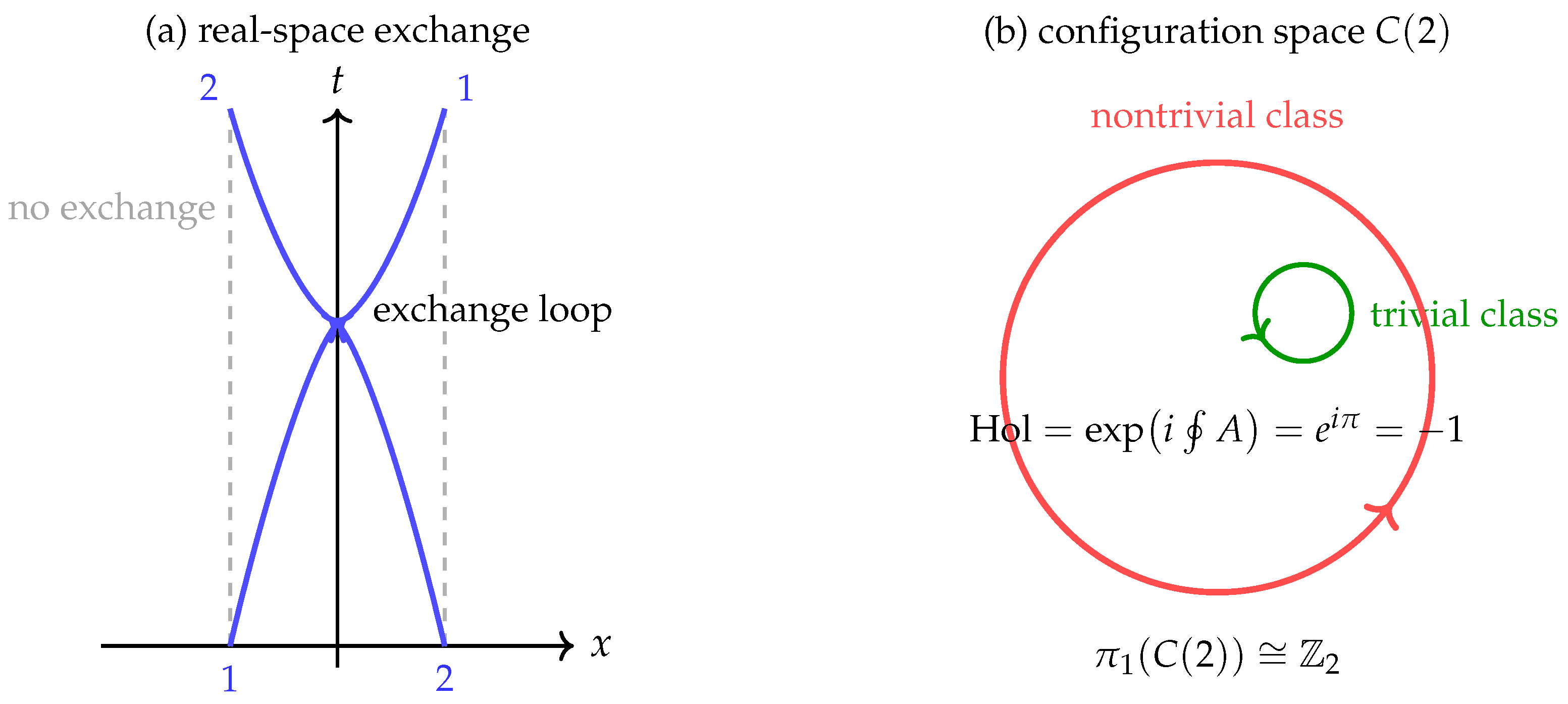

6. Spin–Statistics via FR/Berry and Bundle Matching

The emergence of fermionic behavior in CFT rests on the topology of the soliton moduli space and its associated quantum bundle. The central fact is that both a spatial rotation of a single soliton and the exchange of two identical solitons correspond to nontrivial loops in configuration space, carrying a holonomy. Quantization over this space therefore enforces spin- transformation properties and Fermi–Dirac statistics. We formalize this statement below.

6.1. Topology of and Exchange Space

Let

denote the moduli space of static finite–energy solitons with topological charge

, modulo diffeomorphisms and residual gauge transformations. Standard results on Skyrme–type solitons [

48,

86] adapt directly: the boundary condition

at spatial infinity fixes an internal reference frame, and the residual action of

on spatial coordinates induces a nontrivial

.

The nontrivial loop corresponds to a

spatial rotation of the soliton, which cannot be continuously deformed to the identity without violating the topological constraint [

48].

Similarly, consider the unordered two–soliton configuration space

where

permutes the solitons. One finds

with the nontrivial loop given by exchanging two identical solitons along a closed trajectory in configuration space [

88]. This exchange loop is homotopically distinct from the trivial path and represents the generator of

.

theorem 6.1 (FR/Berry fermionic sector). A spatial rotation of a single soliton and the exchange loop of two identical solitons each represent the nontrivial element of . Quantization over the corresponding Hilbert bundle assigns a holonomy to these loops, so soliton wavefunctionals transform as spin- objects under rotation and acquire a minus sign under exchange. Thus the solitons exhibit Fermi–Dirac statistics.

Sketch The argument follows the Finkelstein–Rubinstein (FR) construction [

48,

49]. Quantization is defined not on configuration space

itself but on its universal cover

. Wavefunctionals

are required to satisfy the FR constraint

for any loop

, where

is a one–dimensional representation. Since

, there are two possible representations; physical consistency with the Berry phase calculation below selects the nontrivial representation. Thus

for the generator, enforcing fermionic behavior. In particular, a

rotation or an exchange loop both generate

, yielding the minus sign. □

6.2. Berry Connection and Bundle Matching

The FR sign can be identified with a geometric phase arising from parallel transport of soliton states along loops in configuration space. This provides a bridge between the topological classification and the emergent gauge structure of CFT.

Proposition 6.2 (Bundle–matching). Let A be the emergent spacetime connection defined in Section 3. Consider the soliton configuration bundle whose fiber carries soliton wavefunctionals. Then the pullback reproduces the FR holonomy class: transport around the nontrivial loop of accumulates a Berry phase of π. Consequently, the geometric phase along an exchange loop is exactly , matching the fermionic sector of Theorem 6.1.

Sketch. On stabilized domains, the emergent

connection

A is locally given by

for the chronon holonomy phase

. When restricted to soliton configurations,

is defined modulo

, so transport around a loop

yields

This corresponds to a Berry phase

[

20,

104]. Thus the pullback bundle

carries exactly the nontrivial

holonomy of the FR construction. The consistency of the two perspectives—topological (FR) and geometric (Berry phase)—establishes the equivalence of spin-

statistics with the holonomy of the emergent gauge sector. □

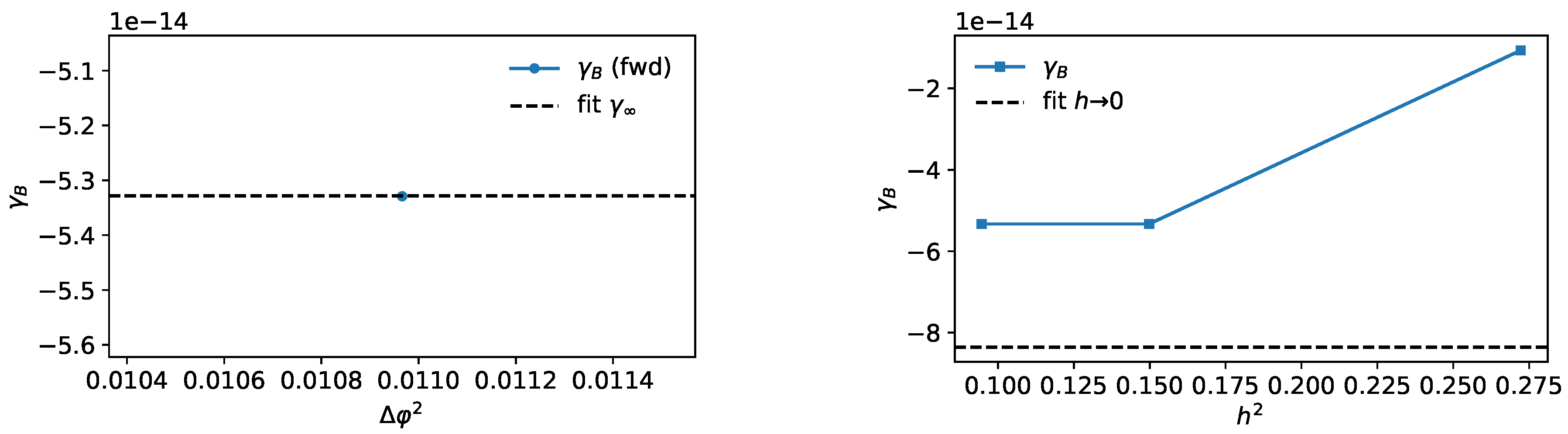

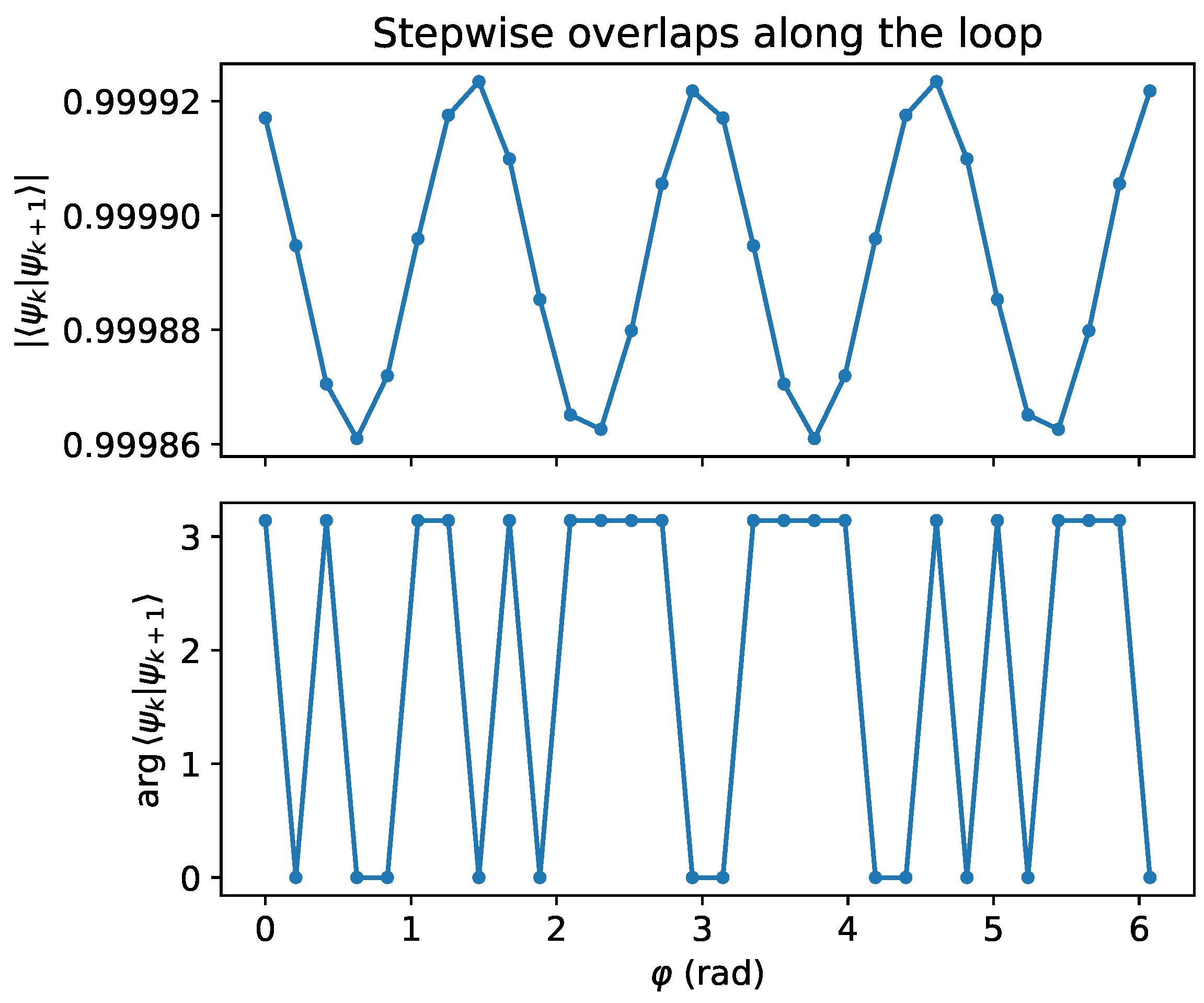

(Computed numerically: , , , anisotropy ; see Appendix L for Maxwell-limit details and Appendix D–D.5 for the convergence study, yielding .)

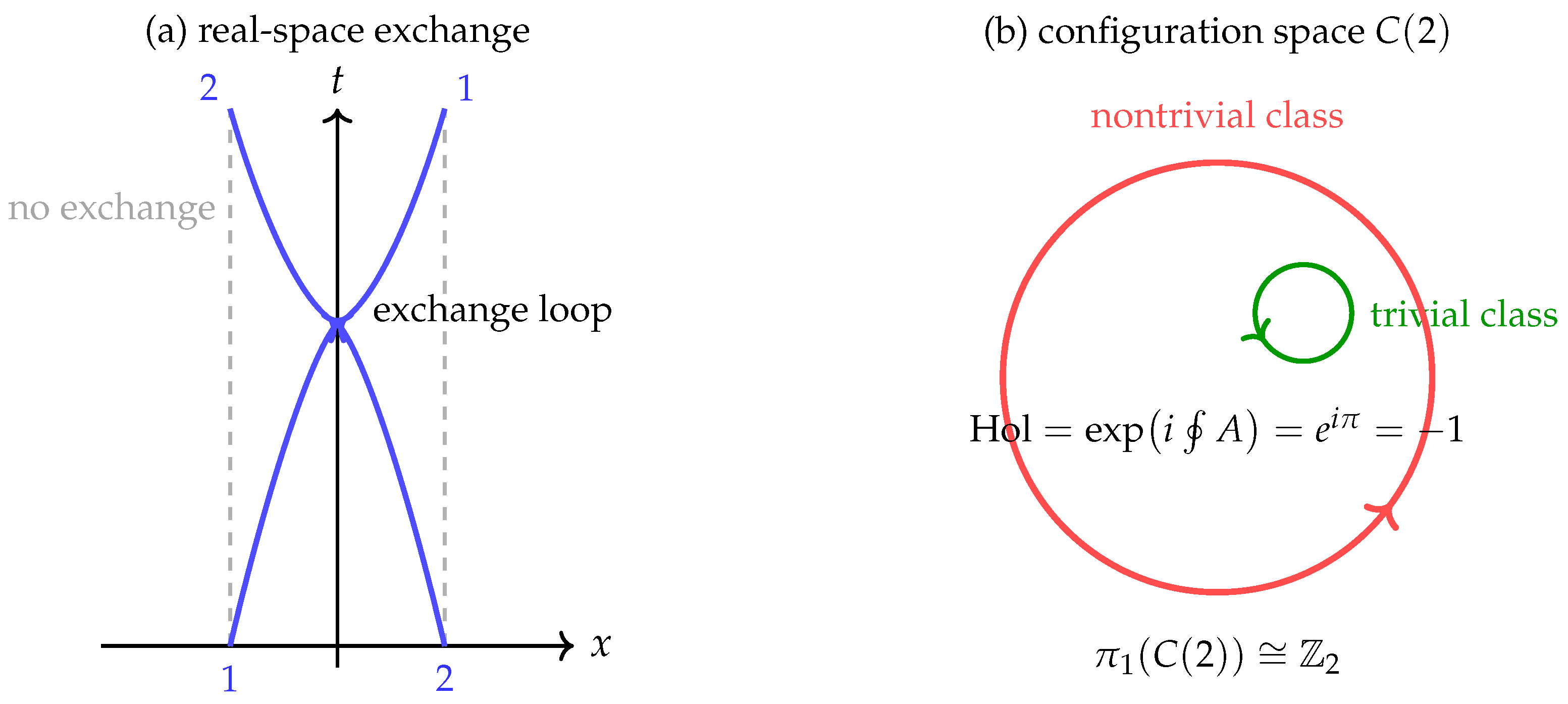

Figure 6.

Exchange statistics from soliton worldlines and configuration–space topology. (a) In real spacetime, two identical solitons follow worldlines (blue curves) that braid around one another as time flows upward. This exchange path cannot be continuously deformed to the trivial “no-exchange’’ case (gray dashed vertical lines) without the worldlines crossing, so it defines a distinct loop, the exchange loop. (b) In the two-particle configuration space , the exchange corresponds to a nontrivial loop in . The trivial class (green) represents no exchange, while the nontrivial class (red) represents a full braid of the two particles. On the soliton ground-state line bundle, the Berry connection assigns holonomy to the nontrivial loop. This geometric phase is precisely the fermionic minus sign: exchanging two identical solitons multiplies the wavefunction by . The figure therefore demonstrates the emergence of Fermi–Dirac statistics from the FR/Berry mechanism in Chronon Field Theory, showing that solitons behave as fermions due to topological and geometric phases.

Figure 6.

Exchange statistics from soliton worldlines and configuration–space topology. (a) In real spacetime, two identical solitons follow worldlines (blue curves) that braid around one another as time flows upward. This exchange path cannot be continuously deformed to the trivial “no-exchange’’ case (gray dashed vertical lines) without the worldlines crossing, so it defines a distinct loop, the exchange loop. (b) In the two-particle configuration space , the exchange corresponds to a nontrivial loop in . The trivial class (green) represents no exchange, while the nontrivial class (red) represents a full braid of the two particles. On the soliton ground-state line bundle, the Berry connection assigns holonomy to the nontrivial loop. This geometric phase is precisely the fermionic minus sign: exchanging two identical solitons multiplies the wavefunction by . The figure therefore demonstrates the emergence of Fermi–Dirac statistics from the FR/Berry mechanism in Chronon Field Theory, showing that solitons behave as fermions due to topological and geometric phases.

Summary

The FR constraint and Berry holonomy coincide in CFT: the nontrivial topology of soliton moduli space enforces a representation, while the emergent gauge connection provides the geometric mechanism by which wavefunctionals accumulate a phase. Together these results prove that solitons behave as fermions, thereby establishing the spin–statistics connection intrinsically within the chronon framework.

7. Quantum Corrections and Emergent Geometric Action Unit

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is a classically covariant, background–independent field theory whose quantum regime arises when the curvature two–form of the chronon manifold stabilizes at a universal magnitude [

13,

51,

82]. In this stabilized phase, the intrinsic symplectic area of the chronon curvature,

defines a constant action unit

. This curvature invariant provides the universal scale controlling quantum fluctuations, operator commutators, and the excitation spectra of solitonic matter [

25,

88,

117]. We summarize below the geometric operator algebra, path–integral weighting, and the resulting spectral corrections.

Physical Intuition

At the microscopic level, the emergence of

can be viewed as a phase–locking transition of the pre–geometric chronon field [

76,

83,

90]. In the disordered regime, chronon orientations fluctuate incoherently and no universal quantum of action exists. As curvature condenses, local chronon phases align and the field attains global coherence: the symplectic flux through a minimal chronon cell becomes quantized in integer multiples of a fundamental unit. Each

winding of the chronon phase corresponds to a complete symplectic twist of a stable soliton configuration, yielding a discrete increment of action

. Quantization therefore originates not from statistical coarse–graining but from the topological stability of these phase windings—an intrinsic property of the condensed curvature manifold [

86,

114]. Only configurations containing an integer number of such

twists are dynamically stable. The emergence of a universal

thus marks a genuine phase transition: spacetime evolves from a pre–geometric, fluctuating medium into a coherent, quantized geometry. In this view, quantization is a manifestation of geometric coherence—the formation of discrete, topologically protected excitation modes—rather than the mechanism by which matter is created.

7.1. Leafwise Operator Algebra

On a stabilized leaf

, the chronon curvature

induces a natural symplectic form on the space of gauge–invariant functionals

:

in analogy with the standard Poisson bracket of symplectic geometry [

38,

42,

95]. Quantization proceeds by promoting these to operators

on the leaf Hilbert space

, yielding the commutator

so that in the strong–stabilization limit

, the canonical equal–time algebra is recovered [

13,

51]. The geometric Planck constant

thus sets the symplectic scale of the chronon manifold and fixes the unit of non–commutativity among observables.

7.2. Geometric Path Integral and Curvature Weighting

The quantum measure is defined directly from the curvature phase of the chronon manifold [

47,

117]. For any stabilized spacetime domain

,

where

is the chronon action,

the emergent

sector action, and

the minimal coupling term. The weighting factor

is not a statistical Boltzmann factor but the phase of the intrinsic curvature flux

, and perturbative corrections to classical saddle points are organized by powers of

, which serves as the loop–expansion parameter of the curvature phase field rather than a phenomenological constant.

7.3. Implications for Spectra

Solitonic excitations in nontrivial topological sectors

acquire quantum corrections governed by (

33)–(

34) [

86,

116]. Two principal effects appear.

Collective–Coordinate Quantization

As detailed in Section 5, translational, internal

, and isorotational zero modes of a soliton become quantum collective variables. Their spectra exhibit energy splittings

where

I is the geometric moment of inertia of the soliton configuration [

7]. This scaling parallels the quantization of Skyrmions but with

determined by the curvature of the chronon field, linking rotational spectra directly to the geometry of time.

Zero–Point and Loop Corrections

Fluctuations around the classical minimizer

contribute a zero–point energy shift of order

, while higher–loop corrections are suppressed by higher powers of

[

25,

113]. The semiclassical expansion remains controlled provided the soliton rest mass satisfies

, ensuring that curvature-induced quantum effects remain perturbative.

7.4. Summary

The geometric action unit

plays the same structural role in CFT as Planck’s constant in conventional quantum theory, but its origin is purely geometric: it measures the invariant symplectic area of the chronon curvature manifold. Quantum commutators, curvature phases, and spectral splittings all follow from this fixed curvature invariant rather than from statistical coarse–graining [

51,

88]. In this way, quantization in CFT arises as a manifestation of geometry— a phase of spacetime curvature where the symplectic flux of the chronon field becomes universal and constant.

8. Emergent Fundamental Constants: , G, e, and c

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), the familiar constants of Nature—Planck’s constant

ℏ, Newton’s constant

G, the elementary charge

e, and the speed of light

c—are not postulated but arise as geometric and dynamical invariants of the chronon field. They appear as the normalization coefficients of the low–energy effective action [

101,

116].

Effective Action

At long wavelengths, coarse chronon dynamics induces an Einstein–Maxwell–Dirac–like action

where the coefficients

are determined by the curvature and holonomy structure of the chronon field rather than imposed externally [

25,

93].

8.1. Planck’s Constant as a Geometric Curvature Invariant

As established in Section 7, the universal action unit of CFT,

, originates from the intrinsic symplectic geometry of the chronon field. The curvature two–form

defines the scalar invariant

whose stabilized expectation value fixes the symplectic area of a fundamental chronon cell. Planck’s constant is thus a curvature invariant,

where

is the intrinsic chronon correlation length and

a dimensionless normalization fixed by

.

When curvature condensation stabilizes across spacetime, becomes constant, marking the transition from a pre–geometric phase to a quantum regime with a universal quantum of action. Identifying gives for , reproducing the observed Planck constant. Thus, is the symplectic imprint of spacetime curvature—a fixed geometric invariant rather than a statistical parameter.

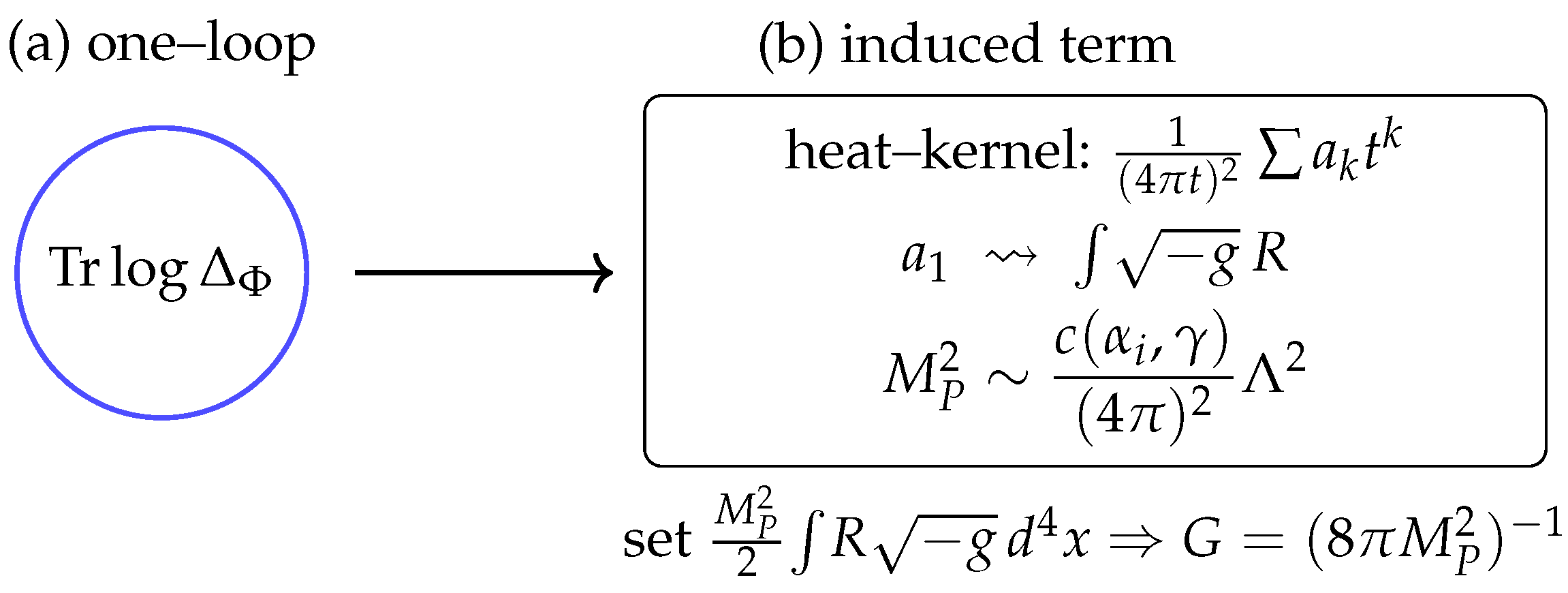

8.2. Newton’s Constant G

The coefficient of the Einstein–Hilbert term arises either directly through the

coupling or radiatively via the Sakharov induced–gravity mechanism [

8,

25,

93,

101,

113]. In both descriptions,

with

determined by the chronon couplings

and the UV cutoff

. Explicit heat–kernel computations in Appendix G show that

where

encodes the integrated curvature response of the stabilized background.

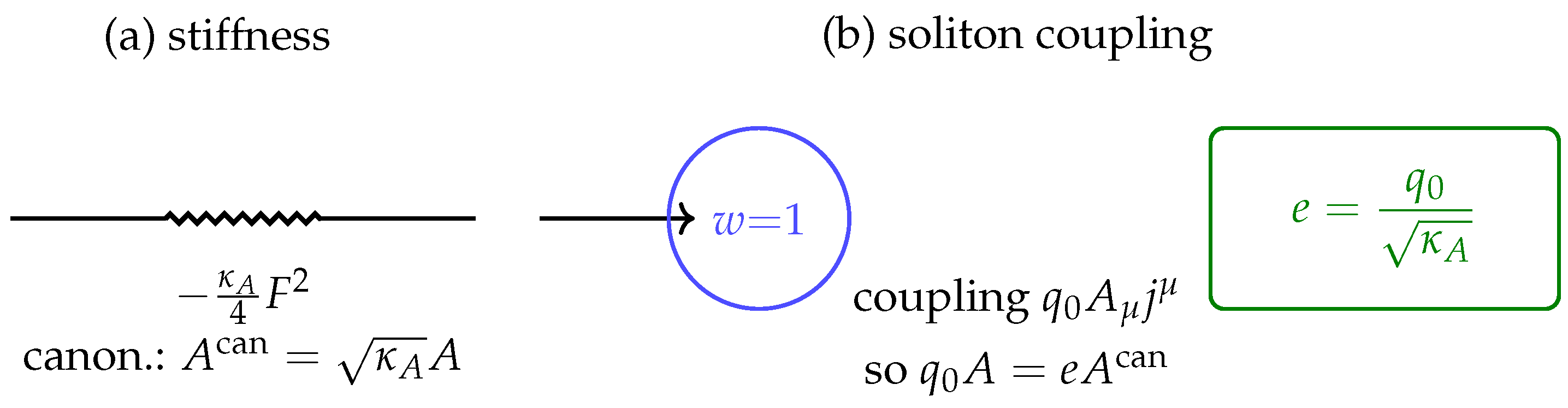

8.3. Electric Charge e and the Coulomb Law

The emergent

gauge field arises as the holonomy of the chronon connection. Its kinetic term,

, is canonically normalized by

[

70,

97]. Solitons couple to

with integer topological charge

determined by the FR/Berry class, giving

In the static limit the gauge field satisfies a Poisson equation, yielding

The observed fine–structure constant

therefore fixes the holonomy stiffness:

For

and

, one finds

, consistent with the Coulomb normalization derived in Appendix J.

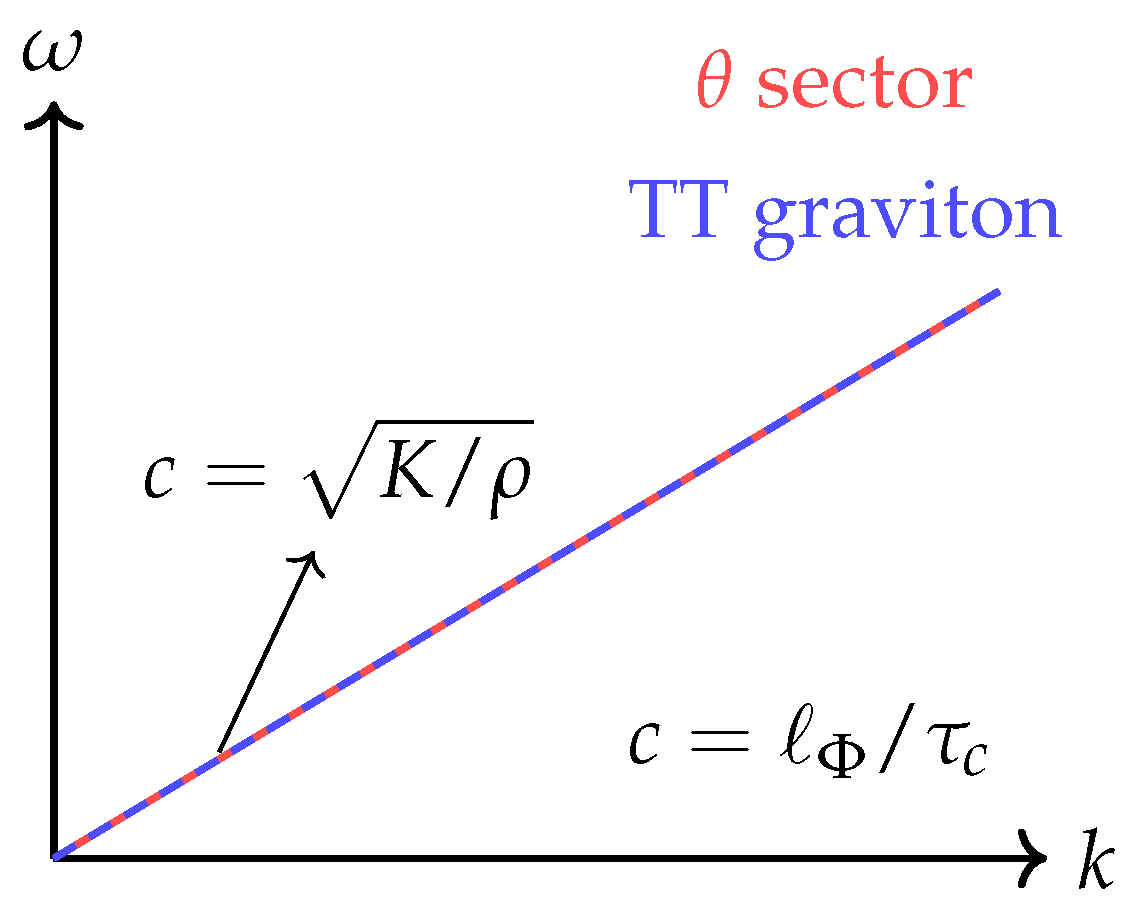

8.4. Speed of Light c

Chronon foliation provides a natural

decomposition with spatial projector

. Quadratic fluctuations of the Goldstone phase

and of transverse–traceless graviton modes yield wave equations of the generic form

with phase velocity

In the stabilized, hypersurface–orthogonal regime the coefficients coincide across matter and gravitational sectors,

ensuring a universal limiting velocity. Equivalently, at the microscopic level,

fixing the conversion between spatial and temporal units [

72,

73,

115]. This equality defines the chronon correlation ratio whose stabilization guarantees Lorentz symmetry at observable scales.

8.5. Physical Interpretation and Representative Scales

The chronon field

represents the coarse–grained velocity field of microscopic temporal excitations [

82,

83]. Its integral curves define the local direction of time flow, while its fluctuations encode the internal degrees of freedom of spacetime itself. In the disordered (pre–geometric) regime, chronon orientations fluctuate incoherently and causal structure is ill–defined. As curvature condenses,

attains macroscopic alignment, giving rise to a well–defined foliation, causal cones, and an emergent Lorentzian metric

[

9,

51,

115]. Small perturbations

around a stabilized background behave as collective modes with dispersion determined by the kinetic and curvature couplings

, while the ultraviolet scale

sets the cutoff of the effective theory [

29,

116].

Representative parameter hierarchy. Table 1 summarizes the physical interpretation and indicative magnitudes of the chronon couplings and scales. These are benchmark values consistent with the emergent relations (

118) and the observational constraints discussed in Section 11.

Numerical illustration. For representative couplings

,

, and

, Eq. (

118) gives

. Using

and

yields

reproducing the observed Planck constant to leading order [

51,

90]. These benchmark values demonstrate that the chronon couplings need not be fine–tuned: natural

parameters reproduce the observed constants of Nature once curvature condensation establishes the stabilized chronon phase.

Interpretation. This analysis anchors the chronon field’s microphysics to physically interpretable scales. The dimensionless parameters

govern the stiffness and curvature coupling of

, while

sets the ultraviolet domain where chronon fluctuations become statistically uncorrelated. When

and

approach the Planck scales, the emergent constants

coincide with their measured values, confirming that CFT requires no additional microscopic tuning [

116,

121]. Quantization, in this view, is a manifestation of spacetime coherence—arising when the chronon field locks into its globally stabilized phase [

82,

114].

9. Unified Origin of Spin, Charge, Quantization, and Interaction

A central outcome of Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is that the fundamental quantum attributes of matter— spin, charge, and quantization itself—share a single geometric origin in the topology of the chronon field. In this framework, the chronon field

supports stable solitonic configurations labeled by an integer winding number

, each representing a complete

rotation of the chronon phase within the internal curvature manifold. This intrinsic phase twist not only gives rise to spin and charge but also determines the universal action unit

, while interactions emerge as the enforcement of temporal coherence among chronon domains [

7,

20,

48,

82,

105,

114].

9.1. Common Geometric Origin

A chronon soliton with winding number

embodies a full

rotation of the chronon phase, encoded in the curvature two–form

This twist projects differently along the temporal and spatial components of the chronon manifold:

Temporal aspect (spin). A

rotation of the local time–flow field

generates a Berry/ Finkelstein–Rubinstein holonomy on the leaf

[

20,

48,

104]. Under this rotation,

returns to itself up to a sign,

, producing spin–

behavior and the fermionic phase factor

. Spin therefore originates from the

temporal holonomy of the chronon’s symplectic twist.

Topological aspect (charge). Viewed through the spatial connection induced by

, the same curvature twist defines a

holonomy,

corresponding to an integer multiple of the elementary charge. Charge thus represents the

spatial projection of the same

twist—the circulation of the chronon connection around a closed spatial loop [

76,

86,

88,

123].

Spin and charge are therefore complementary manifestations of one geometric phenomenon: the complete phase rotation of the chronon field within the spacetime curvature manifold. The chronon soliton is a unified excitation whose internal temporal holonomy yields spin, while its spatial holonomy defines charge.

9.2. Quantization from Topological Stability

Because the chronon curvature manifold admits only globally coherent configurations with integer multiples of

phase winding, the corresponding action increments are quantized:

This equation expresses

as the invariant symplectic area of a fundamental curvature cell of the chronon field. Quantization thus arises not from coarse–graining or statistical averaging, but from the

topological stability of completed

phase twists—the only dynamically stable excitations in the condensed curvature phase [

42,

47,

98,

114,

117]. This intrinsic discreteness of the symplectic flux defines the universal quantum of action.

9.3. Interactions as Temporal Coherence

Interactions among chronon solitons emerge as the dynamical enforcement of phase coherence across neighboring domains. The gauge field

functions as a Lagrange multiplier mediating synchronization of local chronon phases, transporting temporal curvature and maintaining global alignment of

. Electromagnetic and gravitational couplings thus appear as collective modes of the chronon condensate that preserve temporal coherence [

10,

31,

72,

73,

79]. In this sense,

interaction is not a fundamental force but a manifestation of curvature–induced synchronization—the self–organization of the chronon field into a globally coherent state.

9.4. Interpretive Summary

Table 2 summarizes the geometric correspondence between the temporal and spatial aspects of the

chronon twist and their associated physical observables.

9.5. Conceptual Synthesis

In summary, the discrete quantum of action

, spin, charge, and interaction all originate from a single geometric principle: the condensation of the chronon field into a coherent, topologically twisted phase of spacetime curvature. This unified interpretation connects the four pillars of microphysics—fermionic spin, electric charge, quantization, and force mediation—to one curvature–driven mechanism: the

symplectic twist of the chronon manifold that stabilizes the temporal fabric of the Universe [

82,

83,

86,

114].

10. Phenomenology and Tests

We outline concrete, falsifiable consequences of CFT at laboratory and cosmological scales. Two classes of effects are especially clean: (i) achromatic birefringence in the emergent gauge sector sourced by weak gradients of the chronon field, and (ii) exchange–phase interferometry for solitons revealing the FR/Berry phase . We also specify a numerical program to connect parameters to observables.

Deviations from GR: observables and bounds CFT predicts controlled departures parameterized by

. (i)

PPN preferred-frame coefficients from æther-like terms; (ii)

GW dispersion/equal-speed tests and

corrections; (iii)

vacuum birefringence/dispersion from

-dependent gauge operators. We map these to data in Appendix K and require compatibility with present bounds [

2,

79,

121].

-

Achromatic birefringence from –dependent couplings. On stabilized domains, gauge invariance and diffeomorphism invariance allow, beyond the Maxwell term, parity–odd and parity–even operators that couple

to slowly varying chronon backgrounds.

1 Two representative classes are:

with

. Here

is a pseudoscalar functional and

a symmetric rank–2 tensor functional built from

and its derivatives (e.g.

,

,

), normalized so that

on stabilized leaves. Both operators preserve

gauge invariance;

violates parity and time reversal, while

is parity–even but anisotropic [

31,

85].

Geometric–optics limit. Let

with wave–covector

,

at leading order. To first nontrivial order in

and the couplings

, the polarization

obeys a parallel–transport equation modified by (48)–(49). For (

48) one finds an

achromatic (CPT–odd) polarization rotation for a linearly polarized wave propagating along a null curve

:

independent of frequency to this order.

2 For (49), birefringence arises from a small

anisotropic phase–velocity split between orthogonal linear polarizations relative to the projector

:

with

an orthonormal polarization basis transported along

. To leading order this rotation is also achromatic if

varies only on scales

(the wavelength) [

31,

85].

Constraints and forecasts. Equations (

50)–(

51) provide direct parameterizations for data analyses:

where

labels the line–of–sight and

is comoving distance. Cosmic microwave background and radio/optical polarimetry constrain the sky–averaged and multipole–dependent rotation

; the distinguishing feature here is

achromaticity (no

Faraday scaling). Forecasts can be obtained via a Fisher analysis on the

and

spectra with

treated as a parameter or a field, using

and the covariance from instrumental noise and lensing

B–modes [

75,

85]. Laboratory constraints follow by inserting

over a baseline

L, giving

, measurable with high–finesse cavities or resonant optical gyroscopes [

106].

-

Exchange–phase interferometry for solitons: geometric phase . The FR/Berry analysis (Section 6) predicts a topological phase for adiabatic exchange of two identical solitons. We outline two protocols that isolate this sign.

Braiding interferometer. Prepare two solitons in a symmetric double–well on a leaf

, with tunnel–coupling

(spectral gap). Define two adiabatic paths between the same initial/final configurations: (i) trivial swap (no exchange), (ii) counter–circulation that implements a single exchange in configuration space

. Equalize dynamical phases by time–reversal–symmetric scheduling (spin–echo style) so that the interferometric contrast depends only on the geometric phase:

For

the output is extinguished, a smoking–gun of the FR sign [

20,

104].

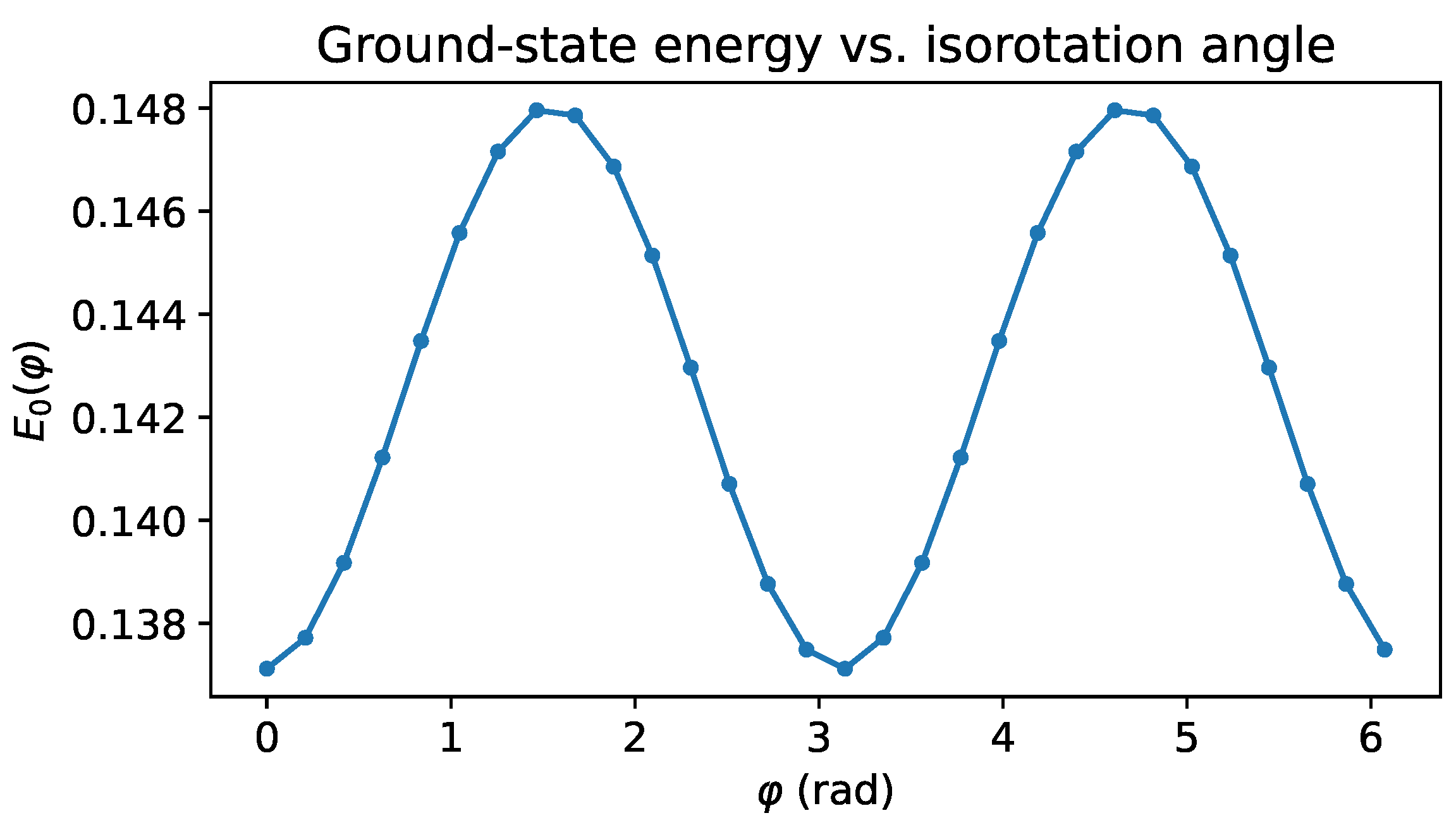

Ramsey–Berry protocol. Treat a collective coordinate

(e.g. relative angle or position on a ring trap) as a slow variable on which the soliton ground state

depends. Drive a closed loop

that realizes the generator of

. The accumulated phase is

while the dynamical phase can be nulled by a spin–echo sequence. Readout via parity oscillations or population imbalance reveals the

shift. Adiabaticity requires

and weak dephasing; robustness follows from the topological nature of

[

20,

104].

-

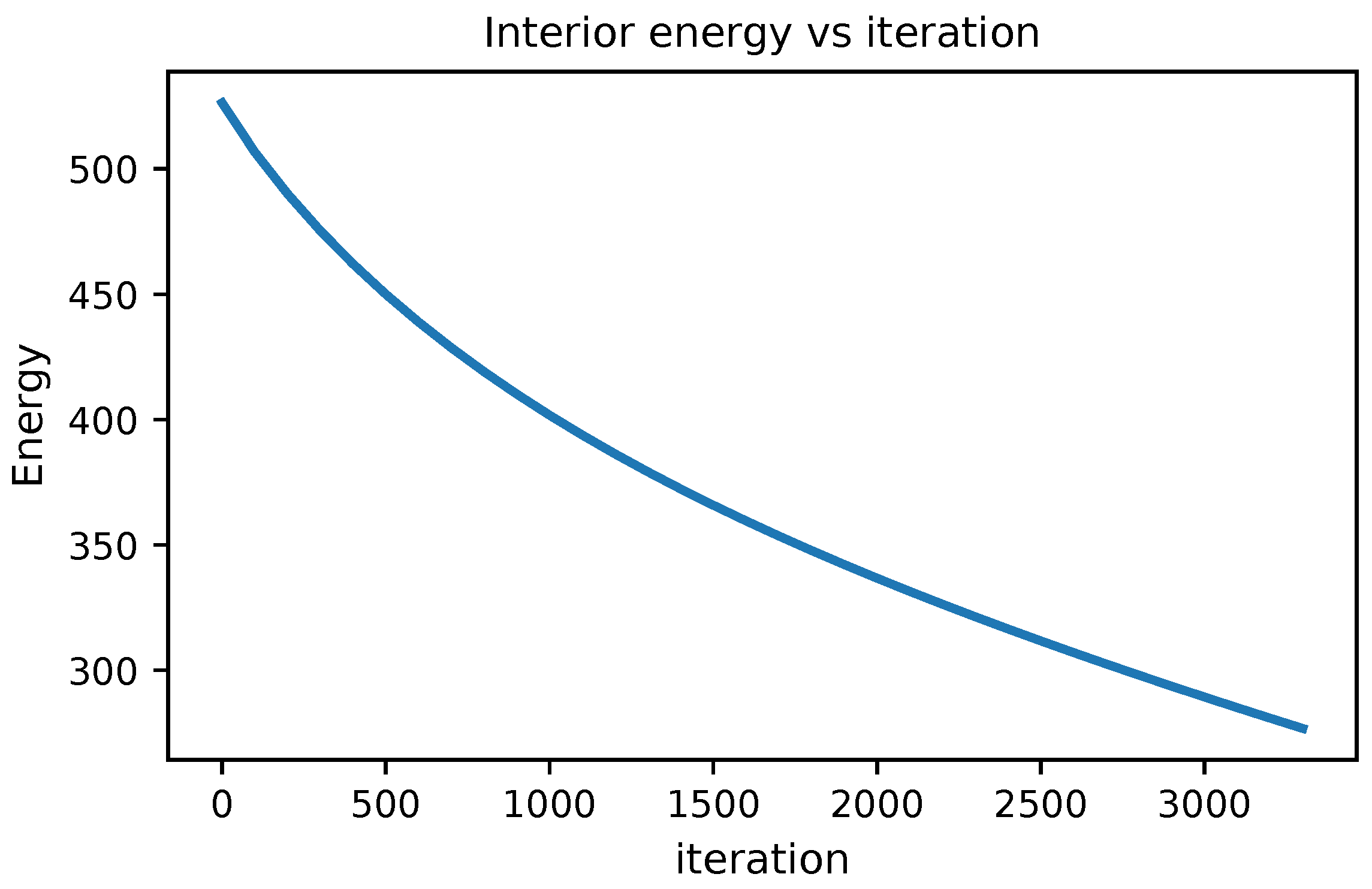

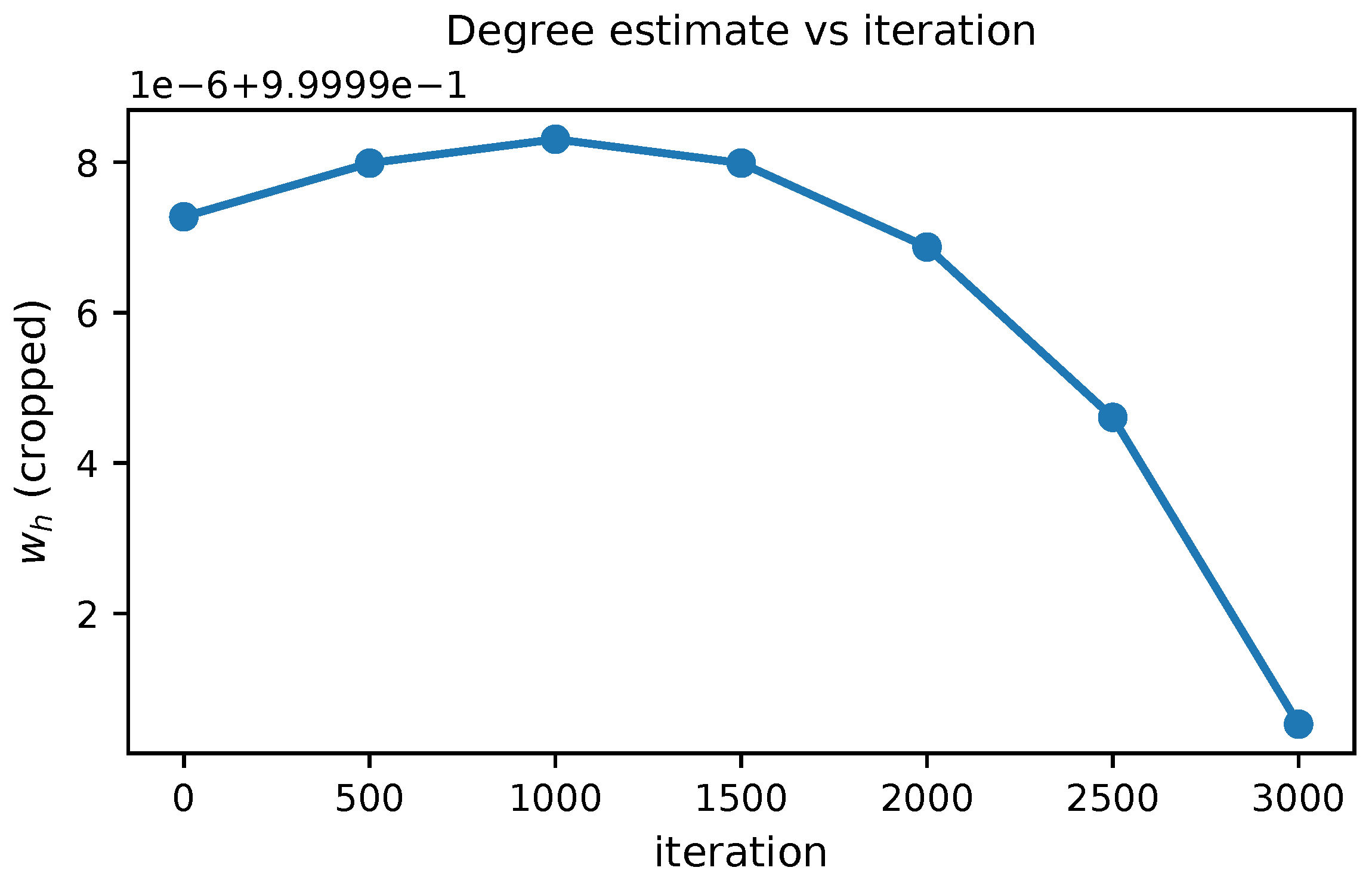

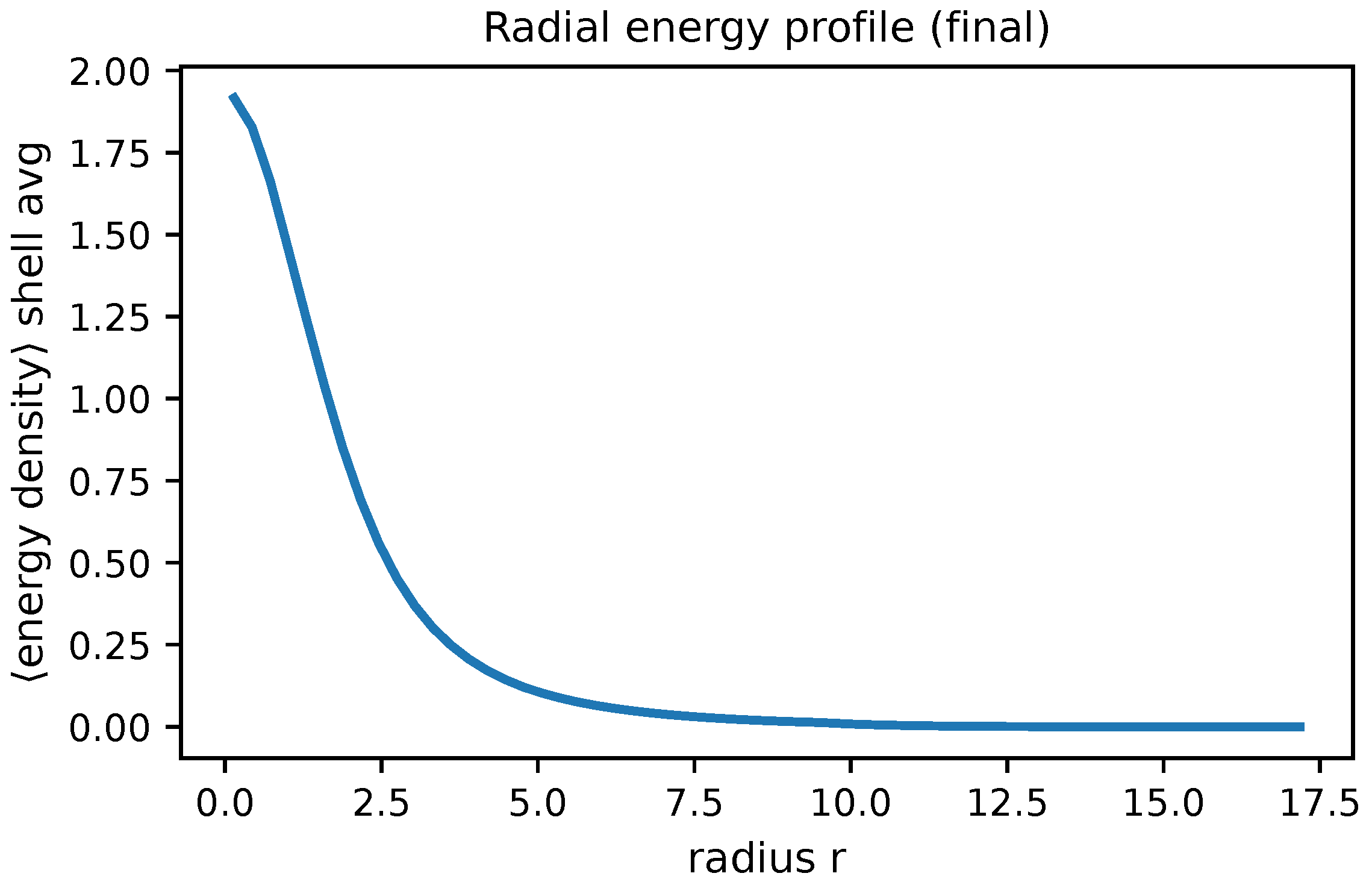

Numerical demo (to include): stable profile, mass vs. couplings; Berry holonomy. We propose a reproducible pipeline to connect CFT parameters to observables:

(a) Static profile and mass. Adopt a spherically symmetric ansatz realizing

on

(e.g. a hedgehog map

in an orthonormal frame). Minimize

via constrained gradient flow with

enforced by a Lagrange multiplier. Convergence certifies existence and furnishes

; scan

to obtain

–versus–coupling surfaces and stability bands (positive second variation) [

86].

(b) Linear spectrum and moments of inertia. Linearize the CFT equations about the minimizer to compute the small–oscillation spectrum and the collective inertia tensor

for zero modes (translations, internal rotations). Predict rotational/vibrational splittings

(Section 7) and compare with interferometric timescales [

7,

86].

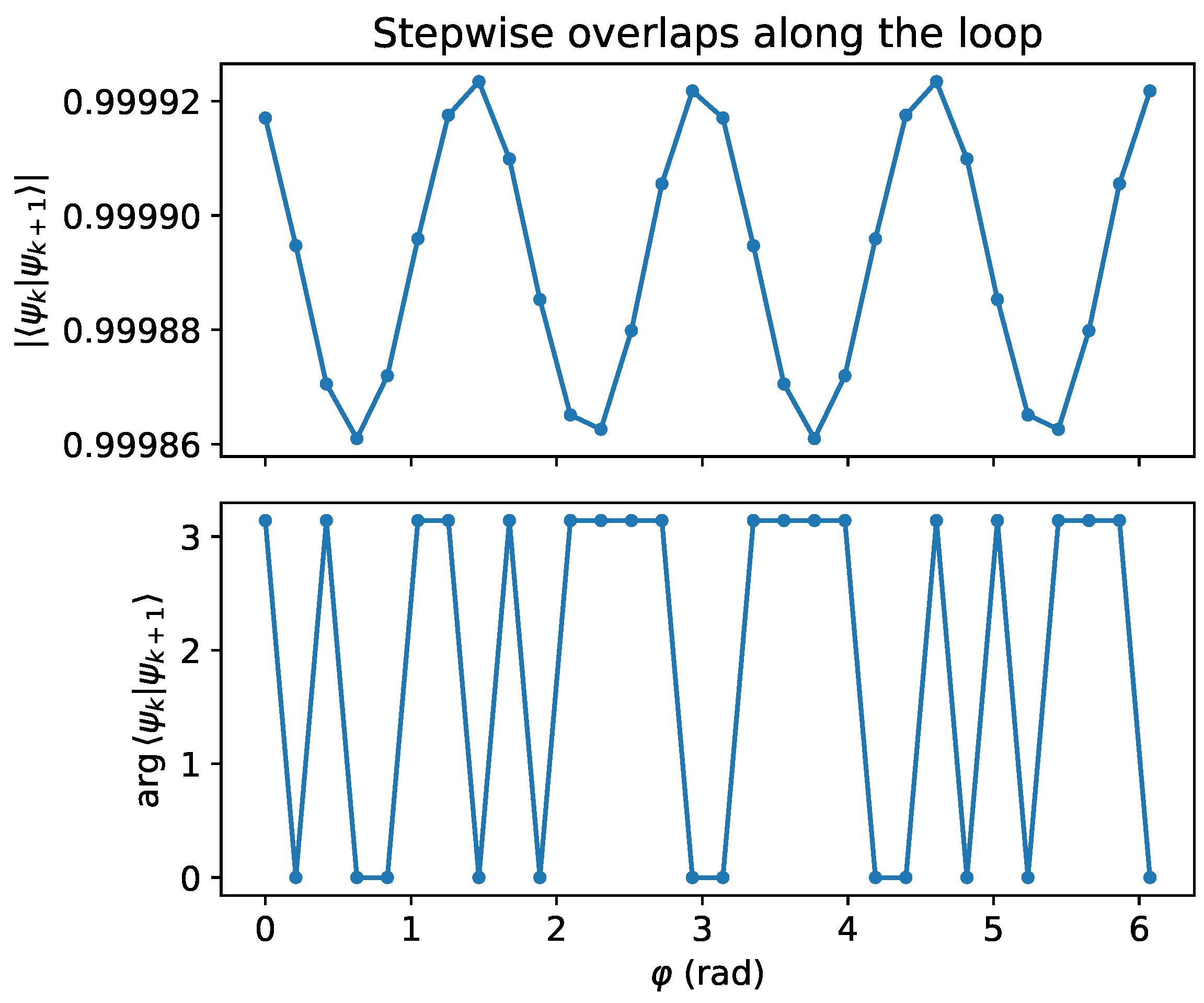

(c) Berry holonomy computation. Discretize a loop

in

(e.g. a

rotation or exchange path) and evaluate the gauge–invariant discretized Berry phase

One should obtain

within numerical tolerance, with convergence under refinement and robustness to local gauge choices in the solver [

52,

92].

Outlook

The achromaticity and geometric protection of the predicted signals make them resilient to common systematics (frequency–dependent Faraday rotation; path–dependent dynamical phases). A combined program—cosmological birefringence constraints/forecasts via (

52) and controlled soliton interferometry implementing (

53)–(

54)—provides a stringent testbed for CFT at both infrared and mesoscopic scales.

11. Discussion and Outlook

The results of this paper establish a consistent, covariant, and background–independent framework in which (i) a conserved and geometrically defined mass–energy density is formulated [

115], (ii) solitonic excitations exist and are stable in the minimal topological sector

[

86], (iii) the spin–statistics connection arises from the topology of configuration space and its Berry holonomy [

20,

48,

104], and (iv) an Abelian

gauge sector appears naturally as a holonomy of the chronon curvature field [

77,

88]. Together, these results support the interpretation of CFT solitons as fermionic matter coupled to emergent electrodynamics.

Crucially, the constants of Nature—

ℏ,

G,

e, and

c—are not postulated but

derived geometric invariants. In particular, the Planck constant

arises as the invariant symplectic area of the chronon curvature manifold, as shown in Section 7 and Appendix F. It is given by a purely geometric relationship:

so that quantization itself becomes a manifestation of stabilized curvature. In this sense, CFT realizes quantum mechanics as the macroscopic phase of a condensed curvature geometry.

GR as Infrared Limit

We treat General Relativity (GR) as the infrared universality class of CFT. Section 8.6 states this limit precisely, while Section 9 and Appendix K quantify the power–suppressed deviations and their observational bounds [

73,

116,

121]. The induced–gravity mechanism (Appendix G) links Newton’s constant to the same curvature–symplectic invariants that fix

, showing that

G and

ℏ share a common geometric origin.

Table 3.

Representative operator combinations and their observational channels. Bounds are indicative IR targets; precise values depend on background/dataset (see text).

Table 3.

Representative operator combinations and their observational channels. Bounds are indicative IR targets; precise values depend on background/dataset (see text).

| Operator / coeff. |

Physical channel |

Observable / bound |

Comment |

|

,

|

PPN (preferred frame) |

,

|

Suppress shear/accel. terms on stabilized leaves |

|

GW dispersion (tensor) |

,

|

High–k tail in waveforms; multimessenger tests [2] |

|

Photon dispersion |

|

Time–of–flight constraints (pulsars/GRBs/FRBs) |

|

Vacuum birefringence (parity–odd) |

Polarization rotation

|

CMB/AGN polarization; achromatic tests [31,79,85] |

|

Induced EH (gravity) |

|

G fixes (Appendix G) [101,113] |

|

,

|

Coulomb law /

|

,

|

Fixes gauge stiffness (Appendix J) |

|

Soliton mass (electron) |

|

Pins a combo of (Appendix K) |

Limitations

- (a)

Absence of non–Abelian sectors. The present construction realizes only an Abelian

holonomy. Extending the curvature bundle to higher–rank structures is required for

and

sectors, a task undertaken in Paper II [

51,

88].

- (b)

Massless vector modes. The emergent photon is a curvature–Goldstone excitation and hence massless. Realizing massive vector bosons (, ) will require introducing additional topological order or condensates within the chronon manifold.

- (c)

Microscopic completion of . Although has been derived geometrically from the stabilized curvature two–form, a full microscopic treatment of curvature condensation—analogous to an order–parameter potential—remains to be formulated.

- (d)

One–loop gravity matching. Appendix G identifies the induced–gravity mechanism and the relation

, but an explicit heat–kernel computation of

on stabilized curvature backgrounds remains open, together with a complete PPN analysis [

113,

121].

- (e)

Numerical demonstration. Existence and stability have been shown variationally, but explicit numerical minimizers, dispersion extractions (

), Coulomb fits, and Berry–holonomy computations are ongoing. Their completion is essential for quantitative parameter inference [

86].

Beyond Apparent Lorentz Violation

The EFT analysis presented here maps chronon–induced operators to SME/PPN frameworks, confirming compatibility with stringent experimental bounds. However, this EFT viewpoint does not capture the deeper mechanism by which CFT preserves operational Lorentz invariance. In subsequent work we develop the Co–Moving Concealment Mechanism (CCM): since all matter, fields, and observers are excitations of the same stabilized chronon foliation, they are intrinsically comoving with the universal chronon frame. Preferred–frame parameters such as therefore lack operational meaning, removing the need for fine tuning. The EFT analysis serves only as a conservative check, while CCM provides the fundamental geometric resolution, to be elaborated in Papers II–IV.

Connections to Subsequent Work

Paper II will generalize the holonomy construction to non–Abelian gauge groups, realizing and curvature sectors and providing the groundwork for electroweak and QCD–like dynamics. Paper III will study confinement, chiral symmetry breaking, and hadronic bound states in this non–Abelian CFT framework. Together with the present results, these constitute a three–part program: (I) fermionic solitons and emergent with derived and Coulomb law, (II) non–Abelian holonomies and symmetry breaking, and (III) strong–interaction phenomenology.

Open Problems

Parameter inference and consistency. Using the derived observables in Appendix K (e.g. , , , hydrogenic spectra, , PPN bounds), perform a global fit of and verify consistency with the Coulomb constraint on .

Higher–derivative EFT and renormalization. Establish the symmetry–allowed higher–derivative basis, compute loop–induced running of

and associated Wilson coefficients, and constrain them via birefringence and dispersion tests [

29,

43,

79,

116].

Strong–field and cosmological regimes. Quantify nonlinear corrections and their effects on gravitational sources, and study background solutions with small

for cosmological applications [

121].

Matter spectroscopy. Compute collective–mode spectra (splittings ), gyromagnetic ratios, and radiative corrections (), comparing them with high–precision data.

Conclusion

This first part of the program demonstrates that fermionic matter, electrodynamics, and the observed constants can emerge from a single dynamical temporal field without postulating quantized matter fields or external time. Quantization itself is reinterpreted as a geometric phase of stabilized chronon curvature, with as the universal symplectic invariant. The framework is covariant, ontologically minimal, and testable through numerical, spectral, and observational signatures. Realizing the non–Abelian sector and completing the parameter–inference program are decisive next steps toward a chronon–geometric foundation for quantum field theory and particle physics.

Appendix A. Derivation of and Field Equations

In this appendix we give the explicit variations leading to the field equations and to the Hilbert stress tensor for the chronon sector introduced in §2, and we supply the full proof details underlying Theorem 4.2.

Appendix A.1. Action, Kinematic Tensors, and Conventions

We work with the parity–even, mass–dimension

chronon action on a stabilized domain:

The Lagrange multiplier

enforces the unit–norm constraint

. We define the basic kinematic tensors

and introduce the linear differential current

We use the Levi–Civita connection of

g, with

, and the Ricci variation identities (Palatini) [

30,

115]:

Appendix A.2. Euler–Lagrange Equations for Φ and λ

Varying (

56) with respect to

and integrating by parts (discarding boundary terms on the stabilized domain) yields

so the Euler–Lagrange equations are

Explicitly, using (

58),

Variation with respect to

enforces the unit–norm constraint

Contracting (

61) with

gives an on–shell expression for

:

(Using

, one may eliminate

from algebraic appearances if desired.)

Appendix A.3. Metric Variation and Hilbert Stress Tensor

The (symmetric) Hilbert stress tensor is defined by

where the last term accounts for the

g–dependence of the connection through (

59). A convenient organization—familiar from Einstein–Æther theory— is to separate the contributions from the

sector and from the non–minimal Ricci coupling [

72,

73]. Writing

and

, one finds

with the constraint term simplifying on shell by (

63).

Derivative Sector

Introduce

from (

58). A standard computation (vary

g in index contractions and in the Levi–Civita connection, integrate by parts, and use symmetry of

) yields [

72,

115]

This is algebraically equivalent to the Einstein–Æther stress tensor with

(no explicit

term), under the identifications

,

,

[

72,

73].

Non–Minimal Ricci Coupling

For the variation of

we use (

59) and discard boundary terms. A standard identity gives, for any symmetric tensor

[

30,

115],

Setting

we obtain

Equations (

67) and (

69) together with (

66) give the full Hilbert stress tensor.

On–shell conservation. Diffeomorphism invariance implies

upon using the field equations (

61)–(

63). Equivalently, one may verify directly by differentiating (

67) and (

69), using Bianchi identities and the

–equations of motion; the Noether–charge formulation makes this manifest [

69].

Appendix K.1. Proof Details for Theorem 4.2

Recall and .

(i) Positivity

Under the induced dominant energy condition (DEC),

for all future–directed causal

. As

is future–directed unit timelike, taking

yields

pointwise [

115].

(ii) Conservation of Jμ

We present a Noether derivation using quasi–stationarity. Consider an infinitesimal diffeomorphism generated by

, with variations

and

. Diffeomorphism invariance gives

Choose

. By Assumption 4.1 (quasi–stationarity),

, hence

and we infer

(The Noether–charge proof gives an equivalent statement [

69].)

(iii) Leafwise Constancy of M(τ)=∫ Σ τ ρd 3 x.

Integrate (

71) over the spacetime slab bounded by two stabilized leaves

and

and a timelike boundary

:

On

, the unit normal is

, so

. The flux through

vanishes for finite–energy configurations (fields decay sufficiently fast), thereby proving

.

(iv) Finiteness for Finite–Energy Data

By (

67)–(

69),

is a quadratic expression in

,

K, and

plus total divergences. On stabilized leaves

with the boundary condition

as

, finite–energy data have

and

, ensuring

[

46,

55].

Remarks. (1) The compact form (

61) in terms of

is useful for existence and stability analyses (§5). (2) The Ricci–coupling contribution (

69) can be recast, via the commutator

, into combinations of

terms plus total divergences; we keep the manifestly covariant form to streamline conservation proofs [

30,

115].

Appendix B. Functional Framework and Regularity

This appendix establishes the variational setting and regularity theory used in the proof of Theorem 5.1. We fix a stabilized leaf as a smooth, oriented, three–dimensional Riemannian manifold. For existence, it is convenient to work on the compactification (achieved by the asymptotic boundary condition at spatial infinity, cf. §5), endowed with the induced metric h. All constants below may depend on and the couplings but not on the field .

Appendix B.1. Function Spaces and Degree

Let

be the Sobolev space of

vector fields with weak first derivatives in

[

6,

27]. We impose the unit–norm constraint pointwise and define manifold–valued Sobolev maps

(Here

is the Euclidean norm on

; this choice is consistent with the use of

as the target under compactification in §5.) Smooth maps

are dense in

within each homotopy class [

21,

60]. The

degree of

is

taking values in

[

26,

62]. For

,

is defined by approximation: choose

with

strongly in

, and set

; this is well defined and independent of the approximating sequence [

21,

109]. For

let

be the configuration class of degree

w. The

moduli space is obtained from

by quotienting by diffeomorphisms connected to the identity and residual gauge symmetries preserving the constraint.

Appendix B.2. Energy Functional and Structural Assumptions

Recall the energy on a leaf

,

with

given in Appendix A. In the static setting on

,

is a quadratic form in first derivatives of

plus lower–order terms coming from curvature couplings. Concretely, one can write

where the coefficients are smooth in

, bounded on

, and depend linearly on the couplings

.

We impose the following uniform ellipticity and boundedness hypotheses (they are satisfied for an open cone in the coupling space including the positive–definite case):

-

(S1) Strong ellipticity.

There exists

such that for all

, all

, and all

,

tangent to

at

,

-

(S2) Controlled lower–order terms.

There exist constants

such that

In particular, (S1)–(S2) yield the

coercivity and

growth estimates

for some constant

[

36,

46].

Appendix B.3. Lower Semicontinuity and Compactness

Lemma A1 (Weak lower semicontinuity)

. Let with weakly in . Under (S1)

–(S2)

,

Proof. The principal part is a convex quadratic form in

by (

78), hence weakly lower semicontinuous. The lower–order terms obey (

79) and are bounded in

by the

bound, so they pass to the limit along a subsequence by Rellich–Kondrachov and dominated convergence [

6,

46]. □

Lemma A2 (Weak closedness of the constraint and degree preservation). Let satisfy and weakly in . Then (up to a subsequence) and .

Proof. The embedding

is compact for

in 3D, hence

strongly in

for all

, and a.e. along a subsequence (Rellich–Kondrachov). Since

a.e., we obtain

a.e., i.e.

and the constraint set is weakly closed [

21,

60]. For degree, approximate each

by smooth

with

strongly in

as

, and use the continuity of (

74) under strong

convergence and the compactness

in 3D to pass to the limit

, preserving

[