Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Context

- Foliation theory: The vector field , subject to the Frobenius integrability condition , defines a codimension-one foliation of the spacetime manifold M. This induces a global decomposition , where each leaf inherits both geometric and topological structure from the embedding. Time becomes an emergent field parameter, tied to the integral curves of , consistent with frameworks in foliation geometry [16,58].

- Structure group reduction and symmetry breaking: The unit-norm constraint breaks local Lorentz invariance , reducing the orthonormal frame bundle to a subbundle with spatial rotation structure group. The residual internal symmetry is a subgroup corresponding to rotations in the orthogonal 2-plane transverse to . This reduction of the frame bundle follows the formalism developed in [6,47], and yields an effective principal bundle associated with internal phase transport.

- Homotopy and soliton charge: The normalized spatial projection of the vector field defines a continuous map from the spatial boundary at infinity (modeled as ) to the unit sphere , encoding the direction of . Such maps are classified by the homotopy group , yielding topologically protected winding numbers that correspond to quantized electric charges [14]. This mechanism parallels quantization structures in nonlinear sigma models and Skyrme fields [55].

- Topological currents and cohomological interpretation: Electric charge conservation arises from a topological current constructed as a closed 3-form , where K is built from derivatives of and satisfies identically. The integral of this current over a Cauchy surface yields an integer-valued topological invariant, interpretable as a degree class in . This connects conserved charges to de Rham cohomology and to generalized Chern–Simons-like structures [6,57].

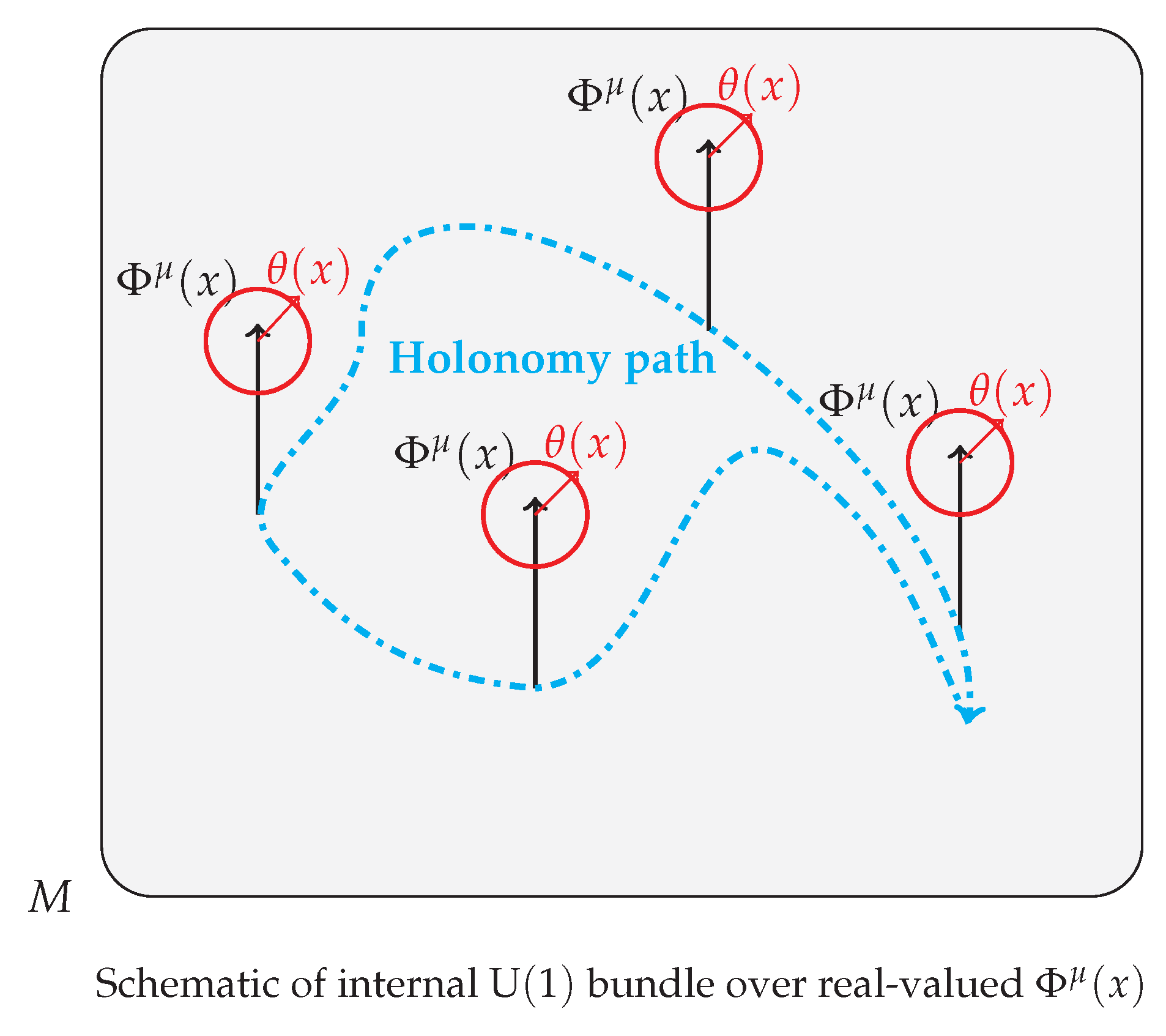

- Gauge emergence from internal holonomy: Rather than postulating a complex scalar field, the theory constructs the gauge potential directly from the real-valued internal phase associated with infinitesimal rotations around . The resulting gauge field is exact but nontrivial on topologically nontrivial manifolds. Its curvature arises from internal phase holonomy and satisfies Maxwell-type field equations derived from the unified action principle. This formulation echoes the geometric description of connections and holonomies in principal bundles [6,70].

3. Geometric and Field-Theoretic Foundations

3.1. Lorentzian Spacetime and the Timelike Vector Field

3.2. Unit-Norm Constraint and Foliation via Frobenius Theorem

4. Internal Structure and Emergent Gauge Dynamics

4.1. Intrinsic Phase from Fiber Geometry

4.2. Definition of Holonomy and Gauge Field from Real-Valued

4.3. Emergence of , and

4.4. Visualization of U(1) Holonomy

5. Topological Origin of Electric Charge

5.1. Compactification and Homotopy Classifications

5.2. Winding Number and Solitonic Charge Configurations

5.3. Topological Current and Charge Conservation

5.4. Quantization via

6. Unified Variational Principle

6.1. Lagrangian Construction and Constraint Enforcement

- R is the Ricci scalar curvature, governing gravitational dynamics via Einstein–Hilbert terms.

- is a scalar field enforcing the constraint .

- is the emergent U(1) gauge potential arising from the internal phase geometry of .

- is the associated field strength.

- includes optional Chern–Simons or Pontryagin terms discussed below.

- is the gravitational coupling constant.

- 1.

- Generally covariant, due to the scalar density .

- 2.

- Gauge-invariant under internal phase shifts , which imply , leaving invariant.

6.2. Derivation of Field Equations

(i) Variation with respect to :

(ii) Variation with respect to :

(iii) Variation with respect to the metric :

(iv) Variation with respect to :

6.3. Optional Topological Terms: Chern–Simons and Pontryagin

(i) Abelian Chern–Simons Term:

(ii) Gravitational Pontryagin Term:

7. Emergent Geometry and Light Propagation

7.1. Effective Metric from Field-Induced Foliation

7.2. Phase Excitations as Goldstone Modes

7.3. Derivation of the Universal Light Speed

8. Emergent Gravitational Waves

8.1. Metric Fluctuations from

8.2. ADM Decomposition and TT Modes

8.3. Dynamical Equivalence of Gravitational and Electromagnetic Speeds

9. Experimental Consequences

9.1. Lorentz-Violating Corrections and Dispersion

9.2. Cosmic Birefringence and Anisotropic Light Propagation

10. Discussion

10.1. Comparison to Kaluza–Klein, Weyl, and Einstein–Cartan Frameworks

Kaluza–Klein Unification.

Weyl Geometry.

Einstein–Cartan Theory.

Ontological and Topological Contrast.

- A foliation from Frobenius-integrable field lines of ,

- An internal U(1) gauge symmetry from residual SO(2) rotations orthogonal to ,

- Topologically quantized electric charge from nontrivial maps ,

- Gravitational and electromagnetic waves as excitations propagating within the foliation geometry.

10.2. Ontological Implications of Time and Charge

- Time from foliation-inducing normalization constraints on ,

- Charge from topological nontriviality of its internal phase geometry.

10.3. Role of Topological Solitons in Matter Genesis

11. Conclusions

- A Frobenius-integrable foliation of spacetime into spatial hypersurfaces , inducing an intrinsic temporal ordering and a geometric realization of simultaneity [31];

- An emergent internal symmetry from real-valued phase rotations in the 2-plane orthogonal to , arising from spontaneous breaking of Lorentz invariance;

- A gauge potential and curvature , built from internal phase holonomy rather than from complex matter fields [14];

- A unified variational principle yielding the coupled Einstein–Maxwell field equations, with the unit-norm constraint imposed dynamically;

- A universal light cone and propagation speed for both gravitational and electromagnetic excitations, identified as gapless Goldstone modes within the foliation geometry [45].

- Ultra-precise constraints on arrival-time discrepancies between gravitational and electromagnetic signals from multimessenger events [1].

Future directions

- Quantum dynamics of : Developing a quantization scheme for in topologically nontrivial sectors, potentially yielding soliton-based particle spectra and insights into quantum gravity [5];

- Non-Abelian generalizations: Exploring whether emergent SU(2) or SU(3) gauge symmetries can arise via fiber bundle extensions, symmetry-breaking cascades, or mappings into higher homotopy spaces;

- Topology-changing processes: Analyzing tunneling events, instanton transitions, or domain wall collisions that could change the winding number Q, with implications for early-universe dynamics and high-energy phenomenology [26].

Author Contributions

Funding

Appendix A. Second-Order Perturbative Analysis of Φ μ

Appendix A.1. Perturbative Setup

Appendix A.2. Second-Order Contributions to the Effective Action

Appendix A.3. Emergent Dispersion Relations and Stability

Appendix A.4. Conclusion of Perturbative Consistency

- Constraint Preservation: The norm constraint is maintained to second order via induced longitudinal terms;

- Propagating Modes: Only three transverse components propagate as physical degrees of freedom;

- Causal Consistency: All propagating modes obey Lorentz-invariant dispersion relations at leading order;

- Stability: No ghosts or instabilities appear in the second-order expansion.

Appendix B. Explicit Coefficients for Gauge and Gravitational Sectors

Appendix B.1. Gauge Sector: Effective Phase Field Coefficients

- : phase inertia (temporal rigidity),

- : spatial stiffness under internal phase gradients.

Effective Gauge Coupling.

Appendix B.2. Gravitational Sector: Metric Fluctuation Coefficients

- : kinetic (inertial) coefficient,

- : gradient (elastic) coefficient.

Coupling Ratio and Universality.

Appendix B.3. Cross-Coupling and Mixed Terms

Appendix B.4. Summary

- : temporal inertia of internal phase,

- : spatial stiffness of emergent gauge sector,

- : gravitational response coefficients,

- : curvature–gauge interaction parameters.

Appendix C. Topology and Global U(1) Bundles

Appendix C.1. Normal Bundle Structure and U(1) Phase Fiber

Appendix C.2. Bundle Classification via Cohomology

Appendix C.3. Winding Numbers and Homotopy Classes π 3 (S 2 )

Appendix C.4. Transition Functions and Čech Cohomology

Appendix C.5. Physical Consequences

- Electric charge is identified with topological winding number , i.e., the degree of the spatial map .

- Electromagnetic field strengthF is globally defined via a connection on a nontrivial bundle, ensuring gauge-invariant dynamics even in the presence of topological obstructions.

- Charge quantization follows from the integrality of the Chern class , unifying topological and physical descriptions.

- Solitonic stability of charged configurations is ensured by the nontrivial homotopy class and conservation of Q.

Appendix C.6. Conclusion

Appendix C.7. Map into S2 and Computation of Winding Number

- is the standard area 2-form on ,

- A is a U(1) connection 1-form on the associated bundle,

- is the pullback of the area form by ,

- The wedge product is a globally defined 3-form on .

References

- B. P. Abbott et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration), “GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 119, no. 16, p. 161101, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Arnowitt, S. Deser, and C. W. Misner, “The Dynamics of General Relativity,” in Gravitation: An Introduction to Current Research, ed. L. Witten, Wiley, 1962.

- M. M. Anber and J. F. Donoghue, “On the running of the gauge coupling in the presence of massless particles,” Physical Review D, vol. 73, 045012, 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Atiyah, Geometry of Yang-Mills Fields, Lezioni Fermiane, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, 1978.

- M. Atiyah, “The geometry of classical particles,” in The Legacy of Niels Henrik Abel, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004, pp. 1–8. [Preprint: arXiv:hep-th/0101009].

- J. C. Baez and J. P. Muniain, Gauge Fields, Knots and Gravity, World Scientific, 1994.

- D. Baumann, “TASI Lectures on Inflation,” in Proceedings of the Theoretical Advanced Study Institute in Elementary Particle Physics (TASI 2009): Physics of the Large and the Small, eds. C. Csáki and S. Dodelson, World Scientific, 2011, pp. 523–686. arXiv:0907.5424 [hep-th]. [CrossRef]

- C. Barceló, S. Liberati, and M. Visser, “Analogue gravity,” Living Reviews in Relativity, vol. 14, no. 1, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Barbour, The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Physics, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- J. F. Barbero G., “Real Ashtekar variables for Lorentzian signature space-times,” Physical Review D, vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 5507–5510, 1995. [CrossRef]

- D. Blas, O. Pujolàs, and S. Sibiryakov, “Models of non-relativistic quantum gravity: The good, the bad and the healthy,” Journal of High Energy Physics, vol. 2011, no. 4, 018, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Bleecker, Gauge Theory and Variational Principles, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1981. ISBN: 978-0201043956.

- R. Bluhm, S.-H. Fung, and V. A. Kostelecký, “Spontaneous Lorentz and Diffeomorphism Violation, Massive Modes, and Gravity,” Physical Review D, vol. 71, 065008, 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. Bott and L. W. Tu, Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 82, Springer, 1982.

- R. Bousso, “The Holographic Principle,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 74, 2002. [CrossRef]

- A. Candel and L. Conlon, Foliations I, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, Vol. 23, American Mathematical Society, 2000.

- S. M. Carroll, G. B. Field, and R. Jackiw, “Limits on a Lorentz and parity violating modification of electrodynamics,” Physical Review D, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 1231–1240, 1990. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Carroll, Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity, Addison-Wesley, San Francisco, 2004. ISBN: 978-0-8053-8732-2.

- S. S. Chern, “A Simple Intrinsic Proof of the Gauss–Bonnet Formula for Closed Riemannian Manifolds,” Ann. Math., vol. 45, pp. 747–752, 1944. [CrossRef]

- Y. Choquet-Bruhat, General Relativity and the Einstein Equations, Oxford University Press, 2000.

- S. Deser, R. Jackiw, and S. Templeton, “Three-dimensional massive gauge theories,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 48, no. 15, pp. 975–978, 1982. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Donoghue, “General relativity as an effective field theory: The leading quantum corrections,” Physical Review D, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 3874–3888, 1994. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Duff, “Kaluza-Klein theory in perspective,” arXiv:hep-th/9410046, 1994.

- T. Eguchi, P. B. Gilkey, and A. J. Hanson, “Gravitation, gauge theories and differential geometry,” Phys. Rep., vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 213–393, 1980. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Faddeev and A. J. Niemi, “Stable knot-like structures in classical field theory,” Nature, vol. 387, pp. 58–61, 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Coleman, “The fate of the false vacuum. 1. Semiclassical theory,” Physical Review D, vol. 15, no. 10, pp. 2929–2936, 1977. [CrossRef]

- B. Z. Foster, “Radiation damping in Einstein-aether theory,” Physical Review D, vol. 73, no. 10, 104012, 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. Frankel, The Geometry of Physics: An Introduction, 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- D. S. Freed and M. J. Hopkins, “Reflection positivity and invertible topological phases,” arXiv:1604.06527, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Garfinkle, “The 3+1 formalism in general relativity,” Classical and Quantum Gravity, vol. 23, no. 22, pp. S529–S552, 2006.

- R. Geroch, “Domain of dependence,” Journal of Mathematical Physics, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 437–449, 1970. [CrossRef]

- E. Gourgoulhon, 3+1 Formalism in General Relativity: Bases of Numerical Relativity, Lecture Notes in Physics, vol. 846, Springer, Berlin, 2012. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Gripaios, “Modified gravity via spontaneous symmetry breaking,” Journal of High Energy Physics, vol. 2004, no. 10, 069, 2004. [CrossRef]

- A. Hatcher, Algebraic Topology, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- S. W. Hawking and G. F. R. Ellis, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, Cambridge University Press, 1973.

- F. W. Hehl, P. von der Heyde, G. D. Kerlick, and J. M. Nester, “General Relativity with Spin and Torsion: Foundations and Prospects,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 48, p. 393, 1976. [CrossRef]

- G. W. Horndeski, “Second-order scalar-tensor field equations in a four-dimensional space,” Int. J. Theor. Phys., vol. 10, pp. 363–384, 1974. [CrossRef]

- B. L. Hu, “Can spacetime be a condensate?” Int. J. Theor. Phys., vol. 44, no. 11, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Jacobson, “Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 75, no. 7, pp. 1260–1263, 1995. [CrossRef]

- T. Jacobson and D. Mattingly, “Gravity with a dynamical preferred frame,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 64, p. 024028, 2001. [CrossRef]

- T. Jacobson, “Einstein–aether gravity: a status report,” PoS QG-PH, 020 (2007). [CrossRef]

- R. Jackiw and C. Rebbi, “Solitons with Fermion Number 1/2,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 13, no. 12, 1976. [CrossRef]

- N. Kaloper and L. Sorbo, “A natural framework for chaotic inflation,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 102, 121301, 2009. [CrossRef]

- T. Kaluza, “Zum Unitätsproblem der Physik,” Sitzungsberichte der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1921.

- T. W. B. Kibble, “Topology of cosmic domains and strings,” J. Phys. A: Math. Gen., vol. 9, p. 1387, 1976. [CrossRef]

- O. Klein, “Quantum Theory and Five-Dimensional Theory of Relativity,” Z. Phys., vol. 37, pp. 895–906, 1926. [CrossRef]

- S. Kobayashi and K. Nomizu, Foundations of Differential Geometry, Vol. I, Wiley-Interscience, 1963.

- V. A. Kostelecký, “Gravity, Lorentz violation, and the standard model,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 69, p. 105009, 2004. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Kostelecký and N. Russell, “Data Tables for Lorentz and CPT Violation,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 83, p. 11, 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Lawson and M.-L. Michelsohn, Spin Geometry, Princeton University Press, 1989.

- J. M. Lee, Introduction to Smooth Manifolds, 2nd ed., Springer, 2013.

- B. P. Abbott et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration), “GW170817: Observation of gravitational waves from a binary neutron star inspiral,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 119, no. 16, 161101, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Lim, “Can we see Lorentz-violating vector fields in the CMB?” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 71, 063504, 2005. [CrossRef]

- A. Lue, L. M. Wang, and M. Kamionkowski, “Cosmological Signature of New Parity-Violating Interactions,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 83, p. 1506, 1999. [CrossRef]

- N. Manton and P. Sutcliffe, Topological Solitons, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- D. Mattingly, “Modern Tests of Lorentz Invariance,” Living Rev. Relativity, vol. 8, 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Milnor and J. D. Stasheff, Characteristic Classes, Princeton University Press, 1974.

- I. Moerdijk and J. Mrčun, Introduction to Foliations and Lie Groupoids, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- G. L. Naber, Topology, Geometry and Gauge Fields, Springer, 1997.

- M. Nakahara, Geometry, Topology and Physics, 2nd ed., CRC Press, 2003.

- C. Nash and S. Sen, Topology and Geometry for Physicists, Academic Press, 1983.

- Planck Collaboration, “Planck 2018 results. XI. Polarized dust foregrounds,” Astron. Astrophys., vol. 641, A11, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Rajaraman, Solitons and Instantons, North-Holland, 1982.

- C. Rovelli, Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- L. H. Ryder, Quantum Field Theory, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- A. D. Sakharov, “Vacuum Quantum Fluctuations in Curved Space and the Theory of Gravitation,” Sov. Phys. Dokl., vol. 12, 1967.

- I. M. Singer, “Some remarks on the Gribov ambiguity,” Commun. Math. Phys., vol. 60, pp. 7–12, 1978. [CrossRef]

- T. H. R. Skyrme, “A Nonlinear Field Theory,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, vol. 260, no. 1300, pp. 127–138, 1961. [CrossRef]

- T. H. R. Skyrme, “A unified field theory of mesons and baryons,” Nuclear Phys., vol. 31, pp. 556–569, 1962. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Steenrod, The Topology of Fibre Bundles, Princeton Mathematical Series, vol. 14, Princeton University Press, 1951.

- R. E. Stong, Notes on Cobordism Theory, Princeton University Press, 1968.

- R. Utiyama, “Invariant theoretical interpretation of interaction,” Phys. Rev., vol. 101, pp. 1597–1607, 1956. [CrossRef]

- V. Vasileiou, A. Jacholkowska, F. Piron, et al., “Constraints on Lorentz invariance violation from Fermi-Large Area Telescope observations of gamma-ray bursts,” Physical Review D, vol. 87, no. 12, 122001, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. E. Volovik, The Universe in a Helium Droplet, Oxford University Press, 2003.

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity, University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- X. G. Wen, Quantum Field Theory of Many-Body Systems, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- H. Weyl, “Gravitation und Elektrizität,” Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 465–480, 1918.

- T. T. Wu and C. N. Yang, “Concept of Nonintegrable Phase Factors and Global Formulation of Gauge Fields,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 12, pp. 3845–3857, 1975. [CrossRef]

- C. N. Yang and R. L. Mills, “Conservation of Isotopic Spin and Isotopic Gauge Invariance,” Phys. Rev., vol. 96, no. 1, pp. 191–195, 1954. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).