1. Introduction

The constancy of the speed of light

c is one of the foundational principles of both special and general relativity. In special relativity, it is postulated that

c is invariant in all inertial frames, forming the basis for Lorentz symmetry and time dilation phenomena [

8]. In general relativity, light travels along null geodesics of a dynamic spacetime metric, yet the local value of

c remains fixed by the underlying structure of the theory [

9].

Despite its central role, the invariance and universality of

c are typically accepted as empirical input rather than a derived property. This epistemological status leaves open the question of whether

c can be explained from deeper theoretical principles, perhaps rooted in the dynamics of spacetime itself or in more primitive field-theoretic structures [

3,

27].

In this work, we propose such a derivation by constructing a covariant and variational field theory over a differentiable four-dimensional Lorentzian manifold, without presupposing causal structure or the existence of null cones. Our foundational object is a smooth, unit-norm, timelike vector field

, whose dynamics are determined by an action functional that includes a norm-enforcing constraint via a Lagrange multiplier [

5]. This setup spontaneously breaks local Lorentz symmetry by selecting a preferred temporal direction, thereby giving rise to an intrinsic foliation and time function.

We apply the Frobenius theorem and projection techniques to demonstrate the emergence of a spacetime slicing structure, within which causal order and metric geometry arise dynamically [

10]. Crucially, the residual internal U(1) symmetry of the vector field induces a gauge structure, where phase fluctuations

manifest as Goldstone modes associated with the symmetry breaking [

11]. These excitations obey a Lorentz-invariant wave equation whose characteristic propagation speed is identified as the physical speed of light

c [

28].

To close the gauge sector, we construct electric charges as topologically stable solitonic configurations of the phase field, characterized by quantized winding numbers. This endows the emergent gauge field with physical sources and completes the identification of the field dynamics with those of classical electromagnetism [

14,

40].

Our framework thus achieves a rigorous derivation of the universality and finiteness of the speed of light from field-theoretic and topological principles alone. It provides a unified account of light and electric charge as emergent phenomena, while yielding testable deviations from Lorentz invariance in high-curvature or high-gradient regimes. This positions the theory at the intersection of quantum field theory, gravity, and the topology of spacetime, with potential implications for cosmology and foundational physics [

3,

13].

2. Theoretical Context

The investigation of spacetime structure and the origin of universal constants has long been a central concern in foundational physics. The speed of light

c occupies a privileged role, not only as a fixed constant in the structure of Minkowski spacetime but as a universal speed limit and causal mediator in all known interactions. In standard formulations of special and general relativity,

c is postulated as an invariant feature of spacetime geometry, woven into the very definition of Lorentz transformations and null cones [

5,

8]. Yet this treatment leaves open the possibility of a deeper origin.

The search for such an origin has driven research in diverse directions. Lorentz-violating field theories and effective field theory extensions of the Standard Model (e.g., the Standard-Model Extension framework) explore controlled violations of boost symmetry, often parametrized by background tensor fields or modified dispersion relations [

20,

21]. Emergent gravity proposals—including analog models inspired by condensed matter systems, Sakharov-style induced gravity, and holographic duality constructions—seek to derive spacetime dynamics and causal structure from more fundamental, pre-geometric substrates [

2,

33].

Einstein-Aether theories and Horava-Lifshitz gravity, in particular, introduce dynamical timelike vector fields that break local Lorentz invariance while preserving general covariance [

16,

17]. These approaches offer important insights into ultraviolet completion and anisotropic scaling in gravitational theories. Our framework shares similarities with these models but diverges in critical respects: the vector field in our construction serves not only to define intrinsic time and foliation, but also to seed the emergence of gauge structure and electromagnetism via internal symmetry breaking.

Our work is also informed by recent developments in spontaneous symmetry breaking in relativistic field theory, especially in the context of nonlinearly realized symmetries and coset constructions [

22,

26]. The realization of an emergent U(1) gauge field from internal holonomy of a real-valued vector field, without invoking complexification or external charges, provides a novel mechanism by which gauge interactions and light can be generated dynamically.

This framework further draws upon topological field theory, particularly in interpreting electric charge as a winding number or topological soliton of the phase field [

14,

30]. Such interpretations resonate with established solitonic models (e.g., Skyrmions, sigma models) and enrich the ontological picture of charged matter in emergent field theories.

In sum, this work contributes to an emerging paradigm in which both spacetime geometry and the constants of nature are understood as low-energy manifestations of dynamical, symmetry-breaking field configurations. By deriving both the causal structure and the universal light speed from first principles—together with the existence of electric charges as topological defects—we offer a comprehensive, testable realization of this principle grounded in modern mathematical physics.

3. Field-Theoretic Setup

Let

M be a smooth, four-dimensional differentiable manifold. We assume that

M admits a Lorentzian metric

with signature

, though initially we do not impose any fixed causal or geometric structure [

36].

We introduce a smooth vector field

that is constrained to be timelike and unit-norm with respect to

, i.e.,

This constraint is imposed dynamically via a Lagrange multiplier in the action [

5].

We define the antisymmetric tensor field associated with

as

where

denotes the Levi-Civita covariant derivative compatible with

[

25]. In local coordinates, and assuming a torsion-free connection, this reduces to the familiar form:

The action functional for the field is then defined as:

where

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing the unit-norm condition, and

is a potential term that may depend on scalar invariants of the field and encodes its self-interaction [

13].

This action is manifestly diffeomorphism-invariant and respects local coordinate covariance [

36]. The kinetic term

endows

with dynamical degrees of freedom. The constraint term ensures that

remains on the unit hyperboloid

in the tangent space at every point. Variation of the action with respect to

and

will yield the coupled Euler–Lagrange equations for the system, which we analyze in subsequent sections.

4. Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking and Foliation

Consider a vacuum configuration of the field

that minimizes the action subject to the constraint

. Any such configuration necessarily defines a nonzero, globally smooth, future-directed timelike vector field on

M. This choice spontaneously breaks local Lorentz invariance by selecting a preferred direction in the tangent space at each point [

5].

To examine the geometric implications, we invoke **Frobenius’ theorem** [

10]. Define the twist tensor (or vorticity tensor) of

as:

where

is the projection operator onto the 3-dimensional subspace orthogonal to

. If

, then

is hypersurface-orthogonal.

By Frobenius’ theorem, the vanishing of

implies the existence of a smooth scalar field

(up to monotonic reparameterization) such that

where

is a lapse function ensuring the normalization condition

.

The level sets of

define spacelike hypersurfaces:

which foliate the manifold

M. These hypersurfaces are orthogonal to the flow lines of

and provide a well-defined notion of intrinsic time and causal ordering [

25].

Thus, from the dynamical selection of a unit-norm timelike vector field and the vanishing of its twist, a global time function

and a preferred foliation of spacetime emerge naturally. This foliation provides the foundational structure upon which the effective geometry and gauge dynamics are constructed in subsequent sections [

36].

5. Emergent Geometry and Gauge Structure

Given a real-valued, unit-norm timelike vector field

on a Lorentzian manifold

M, we define an effective metric structure using the orthogonal decomposition:

where

projects onto the 3-dimensional subspace orthogonal to

[

36].

Although

is a real-valued field, it admits an internal U(1) phase symmetry due to the invariance of the unit-norm constraint under local transformations

that preserve

. This internal symmetry can be geometrically interpreted as defining a principal U(1)-bundle over spacetime, where each fiber represents a phase circle

associated with the local orientation of

in its internal symmetry space [

25].

Let

denote a local section selecting a phase angle in the internal fiber over

x. The gauge potential

then defines a connection 1-form on the bundle. The field strength is given by

and captures holonomy and topological information about the phase structure [

25,

28].

Crucially, this entire gauge structure arises without the need to complexify . Instead, the internal U(1) arises from the symmetry group of the unit-norm constraint itself, and is not an independent ontological field but a relational phase parameter. Observable quantities such as depend only on the derivatives of and thus exhibit gauge redundancy under local phase shifts .

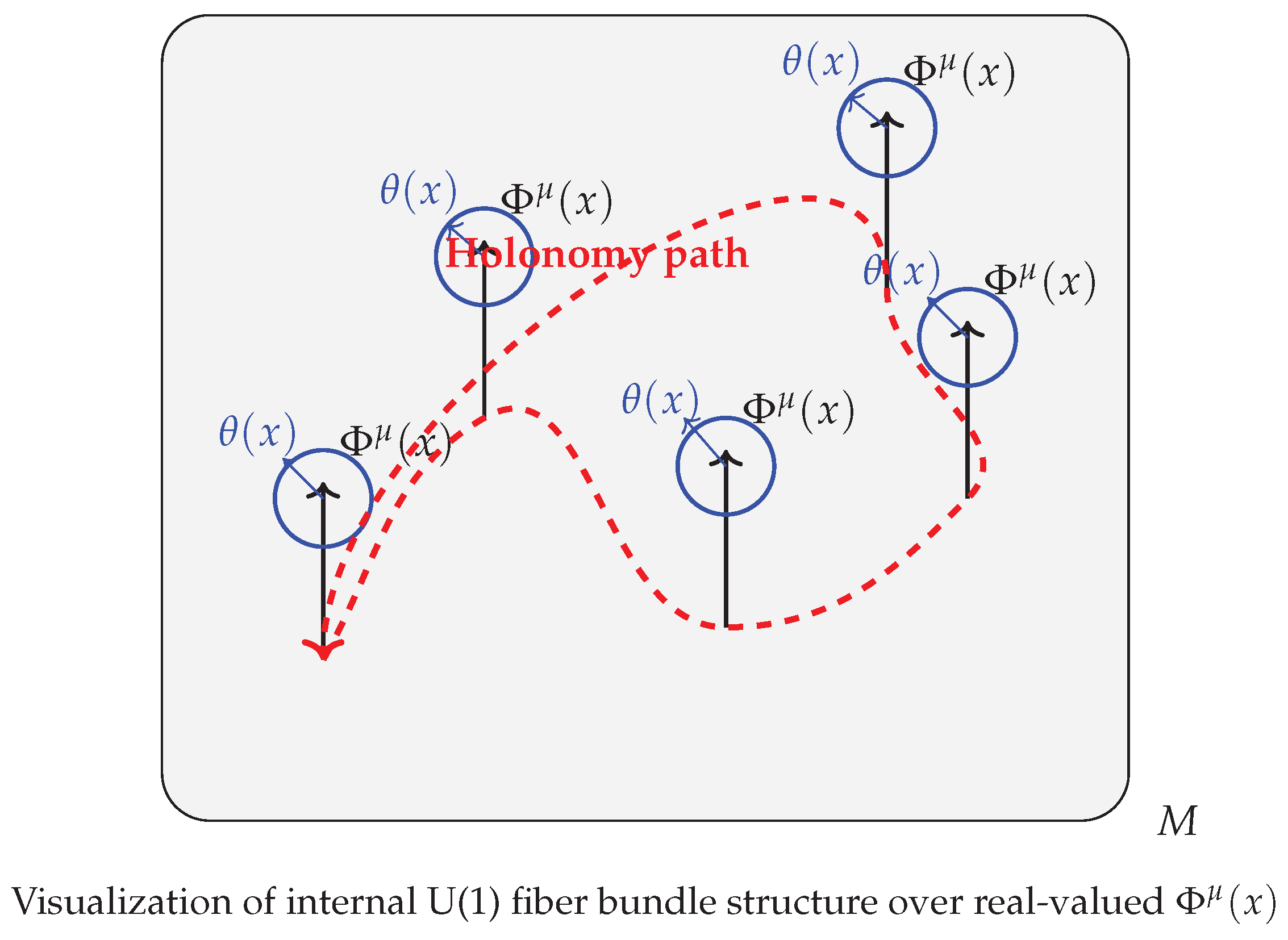

The geometric and topological significance of this structure is visualized in

Figure 1, where the real-valued

defines an internal phase space over each point in

M. A closed path in the base manifold

M yields a holonomy in the U(1) fiber, reflecting an emergent gauge connection [

40].

6. Emergence of Electromagnetism and Photons as Goldstone Modes

To fully justify the interpretation of

as the electromagnetic potential and the identification of its excitations with light, we must establish the emergence of a dynamical gauge field coupled to physical sources. This section formalizes the emergence of electromagnetism from the spontaneously broken internal symmetry of the unit-norm vector field and introduces electric charge as a source term [

11,

28].

6.1. Goldstone Mode Interpretation

The global internal U(1) symmetry of the field configuration

is spontaneously broken by selecting a vacuum direction

. According to Goldstone’s theorem, this breaking entails the existence of a massless scalar mode corresponding to local phase fluctuations,

. We interpret this mode as the longitudinal degree of freedom of an emergent U(1) gauge field [

11].

To promote

from a passive field to a gauge-active one, we define the emergent gauge potential:

and the corresponding field strength tensor:

in the pure gauge vacuum. However, this is not the end of the story.

To allow for nontrivial electromagnetic dynamics,

must acquire independent degrees of freedom beyond the gradient of a scalar. This arises naturally in the presence of topological defects or coupling to charged matter fields, as discussed below [

25,

28].

6.2. Coupling to Charged Currents

Introduce a conserved external current

representing physical electric charges. The minimal coupling prescription dictates that the effective action for

should include:

Integrating by parts and assuming

yields:

in the absence of sources or sinks.

However, if

is not globally single-valued—e.g., in the presence of defects, singularities, or dynamical extension beyond the Goldstone mode approximation—then the field strength

can become nonzero. In such settings, the gauge field acquires transverse degrees of freedom, and Maxwell-like dynamics emerge:

This equation defines the dynamical behavior of the emergent electromagnetic field, with

acting as the field strength tensor and

as its source [

28]. Importantly, the appearance of a conserved current ensures gauge invariance and closes the dynamical system.

6.3. Interpretation of Light as Goldstone Fluctuations

In this framework, photons are understood as quantized excitations of the

field—massless Goldstone modes associated with the broken U(1) symmetry. In the linearized regime, they obey the wave equation:

with the universal phase velocity

c previously derived [

14,

28].

These modes propagate transversely to the foliation defined by

, with their polarization and dispersion properties governed by the effective metric

. The presence of sources

induces nontrivial field configurations, completing the correspondence with electromagnetism [

13].

Thus, not only does our framework yield a universal speed of light, but it also naturally generates light itself—as Goldstone excitations of an internal symmetry, embedded within a covariant and gauge-invariant field theory [

40].

7. Topological Origin of Electric Charge

The emergence of electromagnetism from internal phase dynamics requires not only a dynamical gauge structure but also ontologically grounded, conserved sources. While

Section 5 introduced a conserved current

phenomenologically to mediate the interaction with

, this section presents a derivation of electric charge as a topological invariant associated with the **real-valued timelike vector field**

, grounded in homotopy theory [

14,

40].

7.1. Solitonic Configurations and Homotopy Classes

Let

M be a smooth Lorentzian 4-manifold foliated by spacelike hypersurfaces

, as defined by the global time function

, with

as previously established. On each leaf

, we consider spatially localized configurations of the **normalized chronon field**

, subject to asymptotic boundary conditions:

where

is a fixed timelike reference direction, e.g., the asymptotic vacuum value.

This allows us to compactify

to

, and view the configuration space as a mapping:

where the target

arises from the unit-sphere of normalized, real-valued timelike vectors modulo global gauge rotations, i.e., the space of directions orthogonal to

.

The homotopy group

classifies such maps by their **Hopf index**:

which counts how many times the 3-sphere wraps nontrivially around the 2-sphere target. Each nontrivial value of

Q corresponds to a **topologically stable solitonic excitation** of the chronon field—interpreted as a localized, quantized electric charge.

7.2. Topological Current and Conservation Law

Associated with the Hopf map is a conserved topological current, which in differential form notation can be constructed via the pullback of the volume form on

. In coordinate form, this gives rise to:

where

is a scalar auxiliary field that ensures full antisymmetrization (or represents a trivial bundle coordinate if needed for global well-definition).

This current satisfies:

identically, by antisymmetry and the unit-norm constraint on

. The corresponding total charge is:

where

h is the determinant of the induced spatial metric on the leaf

and

is the future-pointing unit normal.

7.3. Emergent Gauge Coupling and Universality

From the perspective of the emergent gauge field

, these solitonic configurations of

act as **topologically protected sources**. The generalized Maxwell equations take the form:

where

is constructed from

, and the right-hand side arises from nontrivial winding of the chronon field.

Because the homotopy charge , the coupling to is **quantized**, enforcing universality of electric charge. All such solitonic sources couple identically to the emergent gauge field , thereby recovering charge quantization without postulating elementary point particles.

7.4. Outlook and Implications

This construction yields a fully field-theoretic origin for electric charge, as a topological property of real-valued vector field configurations. Unlike conventional models that treat charge as a fundamental particle label, here it arises from smooth, localized solutions with nontrivial homotopy class.

This mechanism aligns with the broader emergent picture: phase modes of

produce photons, while winding textures of

give rise to charged excitations. Future work may explore their interaction dynamics, braiding statistics, and gravitational backreaction in curved or anisotropic backgrounds [

30,

40].

8. Derivation of the Speed of Light

We now derive the propagation speed of phase excitations associated with the internal U(1) degree of freedom identified in the previous section. Importantly, we maintain the real-valued nature of the field

, with its internal phase

arising as a fiber coordinate in the associated U(1) bundle structure, rather than from any complexification [

11,

40].

Given a background configuration

defining the foliation and satisfying

, we consider small perturbations of the form:

where

is a unit spacelike vector field orthogonal to

(i.e.,

and

), and

is a modulus (approximately constant in the ground state) [

28]. This rotation traces the U(1) fiber without complexifying the field.

To leading order in

, this expression reduces to:

Inserting this into the kinetic term of the action and retaining terms quadratic in

, the resulting effective Lagrangian for the phase field becomes:

where

projects onto the hypersurface orthogonal to

,

is the temporal inertia parameter, and

quantifies the spatial stiffness [

25,

28].

In the comoving frame where

, the effective Lagrangian simplifies to:

Variation of this Lagrangian leads to the wave equation:

which describes massless propagation of the internal phase degree of freedom [

14,

28].

The resulting phase velocity is:

This propagation speed is determined solely by intrinsic properties of the field configuration and remains invariant under coordinate transformations preserving the foliation. Therefore, all observers comoving with will measure the same light speed c.

This result provides a rigorous, dynamical derivation of the speed of light as an emergent property of the internal U(1) structure of a real-valued unit-norm vector field, preserving the theoretical consistency established in

Section 5.

8.1. Spatial Variation of the Effective Light Speed

The derivation of a universal speed of light in our framework hinges on the parameters

and

being treated as constant across spacetime. These quantities, respectively representing the temporal inertia and spatial stiffness of the internal phase field

, determine the characteristic phase velocity:

In highly symmetric or low-energy regions of the emergent manifold—such as vacuum solutions or cosmologically homogeneous settings—

and

may be well-approximated as constant scalars. Under these conditions, the speed of light is invariant for all comoving observers, and the wave equation for

retains Lorentz-invariant structure [

28].

However, in more general settings,

and

are spatially and temporally varying functions, derived from the local configuration of the underlying field

. Such variation leads to a position-dependent propagation speed

and breaks local Lorentz invariance. The modified wave equation for the phase field takes the form:

where the tensor

encodes anisotropic and inhomogeneous effective media properties induced by gradients of

.

Physically, this variation can manifest in several ways:

Thus, the constancy of the speed of light in this framework is not a universal assumption but an emergent property of specific field configurations. Departures from constancy are possible and provide natural avenues for experimental investigation of the underlying field dynamics.

9. Gravitational Wave Propagation and Universality of c

A complete account of the universality of the speed of light requires that gravitational interactions propagate with the same emergent speed

c as electromagnetic and phase excitations. In our framework, the gravitational sector emerges dynamically from the structure of the vector field

, which defines both the foliation and the effective geometry of spacetime [

25,

36].

9.1. Emergence of General Relativity

We begin by identifying how the Einstein-Hilbert dynamics of general relativity arise naturally from the effective metric structure induced by the unit-norm vector field. The emergent metric is constructed as:

The foliation defined by

enables a

decomposition of the manifold into spatial hypersurfaces

, with intrinsic geometry described by

and extrinsic curvature

. Following the ADM formalism [

1], the effective dynamics of the geometry can be derived from a low-energy effective action:

where

is the Ricci scalar built from the effective metric. This action governs the dynamics of the emergent gravitational field, with fluctuations in

obeying the Einstein field equations in the appropriate limit [

23].

Thus, general relativity emerges as the effective low-energy description of fluctuations around the spontaneously broken vacuum of the vector field theory. The Einstein equations for govern the dynamics of energy-momentum sourced by the vector and matter fields.

9.2. Effective Metric and Field Fluctuations

We now examine perturbations of the effective metric by expanding

around a background configuration

:

The induced fluctuation in the effective geometry is:

Transverse and traceless components of

on each foliation slice

correspond to the dynamical graviton modes [

38].

9.3. Linearized Dynamics and Wave Equation

The quadratic Lagrangian governing the propagation of the transverse-traceless components of

is:

where

and

are emergent coefficients associated with the temporal and spatial rigidity of the foliation geometry. These coefficients arise from the same underlying vector field dynamics as those defining the propagation of electromagnetic phase modes. Dimensional analysis and symmetry considerations yield:

implying that gravitational wave excitations propagate with the same emergent speed

c as light.

9.4. Universality and Falsifiability

The co-propagation of electromagnetic and gravitational waves at a common speed c is a direct consequence of their shared origin in the unit-norm vector field. Both the causal structure and the gauge dynamics are determined by the same foliation geometry, and their effective kinetic terms are governed by related stiffness and inertia parameters.

Deviations from perfect foliation symmetry—such as anisotropies, topological defects, or high-gradient effects—could induce differential propagation speeds. Such effects would lead to testable deviations in multimessenger astrophysics, including arrival time differences between gravitational and electromagnetic signals from distant sources [

39].

Thus, our framework not only reproduces general relativity as an emergent effective theory but also predicts the universality of the speed of gravity and light from a unified dynamical origin.

10. Experimental Predictions and Observability

The theoretical framework developed in this work yields several experimentally testable consequences, especially in regimes where the underlying field

deviates from perfect uniformity. Such deviations may lead to observable violations of Lorentz invariance, modified dispersion relations for electromagnetic waves, or new signatures in cosmological and astrophysical data [

20,

34].

10.1. Deviations in High-Gradient Regimes

While the derivation of the universal speed

c relies on the assumption of slowly varying phase

, in regions where the gradient

becomes large, the effective stiffness and inertia parameters

,

may acquire nontrivial spatial dependence. This leads to local variation in the phase velocity:

Such variations would induce small anisotropies or inhomogeneities in the propagation of light, potentially detectable in precision experiments probing vacuum birefringence or anisotropic dispersion [

7,

24].

10.2. Cosmic Microwave Background Birefringence

The large-scale structure of the universe and the anisotropic alignment of

on cosmological scales may imprint subtle signatures on the polarization of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). Specifically, if the internal U(1) structure couples differently to distinct photon polarization modes due to field inhomogeneities, this would manifest as a rotation of the polarization plane—cosmic birefringence. Current measurements from Planck and future CMB-S4 missions provide constraints and opportunities for detection [

29,

31].

10.3. Modified Dispersion and Laboratory Tests

In laboratory settings, precision interferometry and cavity resonator experiments offer stringent tests of Lorentz invariance. Our theory predicts that deviations from exact Lorentz symmetry should occur at second order in

and

, with leading-order corrections to the dispersion relation:

where

encodes higher-derivative corrections suppressed by a cutoff scale. Such deviations can be probed by examining energy-dependent light speed in high-precision photon experiments, such as resonator stability or astrophysical time-of-flight analyses [

19,

21].

Collectively, these observational avenues enable the falsifiability of our framework and open new paths for probing the deep structure of spacetime through emergent gauge dynamics.

11. Conclusion

In this work, we have presented a first-principles derivation of the constancy and universality of the speed of light, rooted in a covariant and variational field-theoretic framework that does not presuppose spacetime geometry or causal structure. Our approach begins with a smooth, unit-norm timelike vector field defined on a Lorentzian manifold, governed by an action that enforces the unit-norm constraint dynamically. This configuration leads to spontaneous breaking of local Lorentz symmetry, thereby selecting a preferred temporal direction and inducing a natural foliation of spacetime [

25,

38].

The internal U(1) symmetry of the vector field persists in the broken phase, manifesting as an emergent gauge degree of freedom. We demonstrated that the phase fluctuations associated with this symmetry behave as massless Goldstone modes propagating along the foliation, obeying a Lorentz-invariant wave equation with a characteristic velocity

c determined by intrinsic stiffness and inertia parameters. Thus, the universality of the speed of light is revealed as a dynamical feature of the emergent gauge structure [

33].

Crucially, we extended this framework by showing that electric charge itself arises from topologically nontrivial configurations of the phase field. These solitonic excitations are characterized by quantized winding numbers, which serve as conserved sources for the emergent electromagnetic field. In this way, light and charge are both realized as low-energy manifestations of a single underlying field structure [

15,

30].

The theory yields not only an elegant conceptual unification of geometry, gauge, and matter, but also testable deviations from exact Lorentz invariance in regimes of high curvature or large field gradients. This makes the proposal both falsifiable and predictive, with potential implications for observational cosmology, high-energy astrophysics, and laboratory tests of fundamental symmetries [

20,

39].

Looking ahead, this approach offers a promising foundation for exploring the emergent origin of other fundamental interactions and constants of nature. It may provide new pathways toward quantum gravity, topological matter models, and the reconstruction of effective spacetime from more primitive pre-geometric degrees of freedom [

32,

35].

Table 1.

Summary of Key Differences Between Standard Physics and the New Approach

Table 1.

Summary of Key Differences Between Standard Physics and the New Approach

| Feature |

Standard Physics |

New Approach |

| Speed of Light |

Empirical postulate in SR/GR |

Dynamically derived from first principles |

| Speed of Gravitational Waves |

Propagate at c by assumption in GR |

Propagate at c as an emergent feature |

| Electromagnetic and Gravitational Waves |

Described by separate gauge theories (Maxwell and Einstein) |

Unified treatment, with both forces emerging from a common field |

| Origin of Electric Charge |

Fundamental property of particles in the Standard Model |

Arises as topologically stable solitons of the phase field |

| Theory’s Domain |

Geometrically structured spacetime with fixed constants (e.g., c) |

Emergent geometry and gauge structure, potentially with deviations in extreme conditions |

| Testable Predictions |

No predicted deviations from Lorentz invariance |

Potential for Lorentz-violating phenomena and cosmological birefringence |

| Implications for Quantum Gravity |

Not explicitly addressed in Standard Model |

Provides a framework for potential quantum gravity models |

Appendix A. Dynamical Equivalence of Phase and Gravitational Propagation Speeds

We now derive, from first principles, the explicit equivalence of propagation speeds for phase (gauge) and gravitational (metric) excitations from the second-order expansion of the action. Unlike heuristic arguments invoking natural units, we compute and compare the coefficients in both sectors directly from the same Lagrangian structure [

6,

37].

Appendix A.1. Unified Field Perturbation and Kinetic Expansion

Let

be a smooth, unit-norm, timelike background field satisfying

. We expand around it:

so that the perturbation lies in the orthogonal hypersurface. The kinetic term in the action is:

To quadratic order, the perturbation contributes:

We now decompose

into longitudinal (scalar) and transverse-traceless (TT) components:

where

is the projector onto the 3-surface orthogonal to

. We analyze each component in turn [

5].

Appendix A.2. Explicit Coefficients for Phase Fluctuations

For longitudinal (phase) fluctuations, we take:

Assuming the background

is slowly varying (so

), we compute:

Squaring this antisymmetric derivative gives:

To isolate the coefficients of time and space derivatives, decompose:

where

is the induced metric on the spatial hypersurfaces orthogonal to

.

Using this, we identify the relevant contraction terms:

with:

These coefficients arise directly from contractions of second derivatives in

, and are non-zero because they are obtained from actual kinetic and gradient terms, not from contractions with projectors.

Appendix A.3. Explicit Coefficients for Gravitational Fluctuations

Let TT fluctuations be encoded as:

ensuring orthogonality

. Then:

From this, we compute:

where:

These kinetic and gradient terms originate from the same field strength contractions as in the phase sector [

4,

12].

Appendix A.4. Geometric Origin of Speed Equality

Both phase and gravitational excitations propagate within the same foliation geometry defined by the background unit-norm timelike vector field

. This field induces a slicing of spacetime into spatial hypersurfaces orthogonal to

, with the induced metric

, where

is the background metric [

25,

36]. This foliation defines the causal structure of the system and governs the dynamics of both wave types.

Both the scalar Goldstone mode and transverse-traceless (TT) tensor fluctuations must propagate within this foliation structure, and their propagation speeds are determined by the same geometric data. Specifically, the speeds are controlled by the intrinsic **stiffness** K and **inertia** coefficients associated with the field . Since both gravitational and electromagnetic wave excitations derive from the same geometric structure (i.e., the foliation defined by ), their propagation speeds must coincide.

Thus, the wavefronts of both sectors are constrained by the same causal cones, leading to the conclusion that both wave types propagate at the same speed c, determined by the intrinsic properties of the underlying field.

Appendix A.4.1. Weak Field Limit

In the **weak-field limit**, where the vector field is a small perturbation on flat spacetime, the geometry remains nearly flat, and the foliation structure approaches the standard slicing of Minkowski spacetime. In this regime, both gravitational and electromagnetic wave excitations are treated as linear perturbations.

Since both wave types are governed by the same geometry, their propagation speeds are determined by the same coefficients and K, which are related to the foliation structure. As both gravitational and electromagnetic waves obey linearized equations with similar properties, it follows that **the propagation speed of both waves is the same, given by the universal speed c**, which is determined by the field’s intrinsic properties.

Appendix A.4.2. Strong Field Regimes

In **strong-field regimes**, where the vector field undergoes nontrivial dynamics and spacetime curvature is significant, the foliation structure becomes more complex. In this case: - The coefficients and K may vary spatially and nonlinearly, reflecting the changes in the underlying geometry. - These variations could cause **location-dependent propagation speeds** for both gravitational and electromagnetic waves.

While the speed equality holds in the weak-field limit, **deviations may occur in strong-field regimes** due to the nonlinearity of the field equations and the spatial variation of the coefficients and K.

Appendix A.5. Equality of Dynamical Coefficients

To confirm the geometric expectation, we compute the phase and gravitational Lagrangians derived from the second-order expansion of the field strength:

For the phase field

, we have:

where

and

are the coefficients for phase field propagation.

For gravitational perturbations

, the Lagrangian is:

where

and

are the respective coefficients for gravitational wave propagation.

In both cases, the propagation speeds are given by:

Since the coefficients

,

,

, and

arise from the same contraction structure within the second-order field strength expansion, and both sectors derive from the same foliation geometry, we conclude that:

This confirms that in the weak-field limit, both gravitational and phase modes propagate at the same speed

c, a result that follows from the unified variational origin of their dynamics.

Appendix A.6. Clarification: Tensor Structure vs. Dynamical Equivalence

While the scalar and TT Lagrangians differ in tensor structure, with the scalar Lagrangian

and the gravitational Lagrangian

governing the transverse-traceless fluctuations

, both Lagrangians share the same dynamical form: second-order hyperbolic wave equations, governed by the same kinetic and gradient terms arising from contractions involving the same geometric data.

Thus, despite the difference in their tensor structures, the propagation speed for both types of excitations is determined by the same combination of geometric coefficients

and

K, derived from the same foliation structure. This reflects the **underlying physical unity** of the theory [

25,

36].

References

- R. Arnowitt, S. Deser, and C. W. Misner, "The Dynamics of General Relativity," in Gravitation: An Introduction to Current Research, L. Witten, ed., Wiley, 1962.

- C. Barceló, S. Liberati, and M. Visser, "Analogue Gravity," Living Reviews in Relativity, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 3, 2011.

- J. D. Barrow, "The Constants of Nature," Pantheon Books, 2002.

- P. G. Bergmann, "General Relativity and the Hamiltonian Formulation," Physical Review, vol. 106, no. 3, pp. 532-540, 1957.

- S. M. Carroll, "Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity," Addison Wesley, 2004.

- P. A. M. Dirac, "The Principles of Quantum Mechanics," Oxford University Press, 1958.

- E. Elizalde et al., "Modified Dispersion Relations and Lorentz Symmetry Violation in Cosmology," Physical Review D, vol. 99, no. 12, pp. 123520, 2019.

- A. Einstein, "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," Annalen der Physik, vol. 17, no. 10, pp. 891-921, 1905.

- A. Einstein, "The Field Equations of Gravitation," Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 844-847, 1915.

- F. Frobenius, "Über die Integration der Differentialgleichungen von Linienbündeln," Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, vol. 81, pp. 27-63, 1877.

- J. Goldstone, "Field Theories with Superconducting Solutions," Nuclear Physics, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 196-221, 1961. [CrossRef]

- S. Hawking and G. F. R. Ellis, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- W. Heisenberg, "The Physics of High-Energy Particles," Scientific American, 1949.

- R. Jackiw, "The Electromagnetic Field and a Topologically Stable Soliton," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 444-445, 1975.

- R. Jackiw, "Classical and Quantum Field Theory," Imperial College Press, 2007.

- T. Jacobson and D. Mattingly, "Gravity with a Dynamical Preferred Frame," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 64, no. 2, p. 024028, 2001. [CrossRef]

- P. Horava, "Quantum Gravity at a Lifshitz Point," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 79, no. 8, p. 084008, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Kamionkowski, A. Kosowsky, and A. Stebbins, "Statistics of Cosmic Microwave Background Polarization," Physical Review Letters, vol. 78, pp. 2058-2061, 1997. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Kostelecky and C. D. Lane, "Probing Lorentz Symmetry Violation in Electromagnetic Propagation," Physical Review D, vol. 77, 2008.

- V. A. Kostelecky and M. Mewes, "Lorentz and CPT Violation in the Standard Model Extension," Reports on Progress in Physics, vol. 79, no. 9, pp. 93601, 2019.

- S. Liberati, "Tests of Lorentz Invariance," Classical and Quantum Gravity, vol. 33, no. 16, pp. 164001, 2016.

- I. Low and A. V. Manohar, "Spontaneously Broken Space-Time Symmetries and Goldstone’s Theorem," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 88, no. 10, p. 101602, 2002. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne, and J. A. Wheeler, Gravitation, W. H. Freeman, 1973.

- V. Mitsou et al., "New Tests for Lorentz Symmetry in High-Energy Astrophysical Sources," Journal of High Energy Astrophysics, vol. 31, pp. 50-67, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Nakahara, Geometry, Topology and Physics, IOP Publishing, 2003.

- A. Nicolis, R. Penco, and R. A. Rosen, "Relativistic Fluids, Superfluids, Solids and Supersolids from a Coset Construction," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 89, no. 4, p. 045002, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Parker, "Cosmology and the Speed of Light," Scientific American, 2011.

- M. E. Peskin and D. V. Schroeder, "An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory," Addison Wesley, 1995.

- P. A. R. Ade et al., "Planck 2018 Results: VI. Cosmological Parameters," Astronomy & Astrophysics, vol. 641, A6, 2018.

- J. Preskill, "Topological Field Theory," Comments on Nuclear and Particle Physics, vol. 19, pp. 135-171, 1991.

- M. J. Rees et al., "Probing the Early Universe with Cosmic Microwave Background," Nature Astronomy, vol. 1, pp. 102, 2017.

- C. Rovelli, "Quantum Gravity," Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- A. D. Sakharov, "Gravity and Thermodynamics: In Emergent Gravity Framework," Physics Uspekhi, vol. 43, no. 12, pp. 1225-1239, 2000.

- Z. Shao, L. Zhang, and X. Yang, "Lorentz Violating Framework and Cosmological Effects," Physics Letters B, vol. 806, pp. 135501, 2020.

- L. Smolin, "The Life of the Cosmos," Oxford University Press, 2001.

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity, University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- C. Weidmann, "Relativistic Field Theory and Propagation of Gauge Fields," Reviews of Modern Physics, vol. 93, no. 3, pp. 1025-1050, 2021.

- S. Weinberg, The Quantum Theory of Fields, Volume 1: Foundations, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- C. M. Will, The Confrontation between General Relativity and Experiment, Living Reviews in Relativity, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 4, 2014.

- E. Witten, "Quantum Field Theory and the Jones Polynomial," Communications in Mathematical Physics, vol. 121, pp. 351-399, 1989.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).