Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. MM Cell Lines Showed Differential Sensitivity to Genotoxic Insults

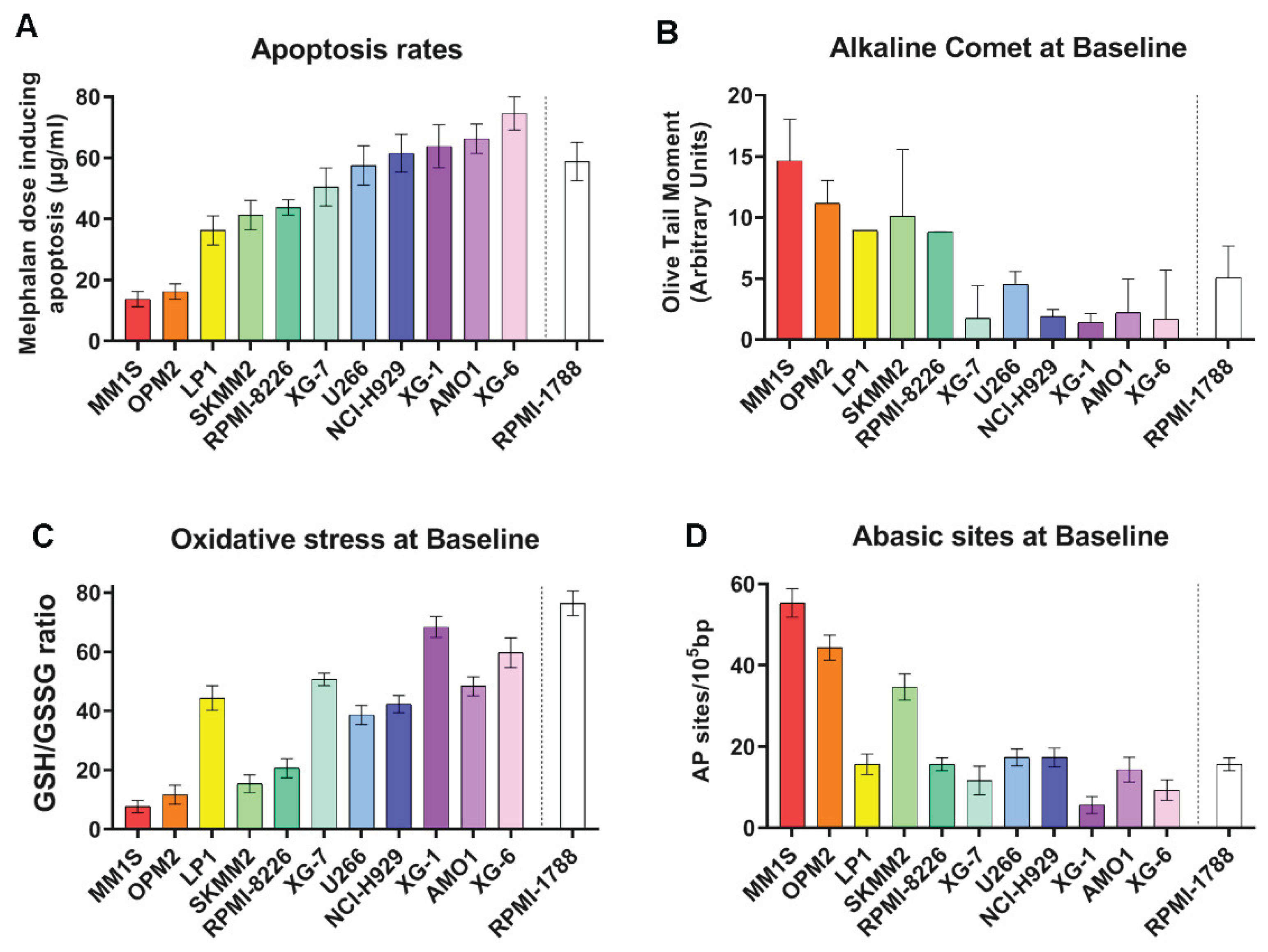

2.2. DDR-Related Parameters in MM Cell Lines at Baseline

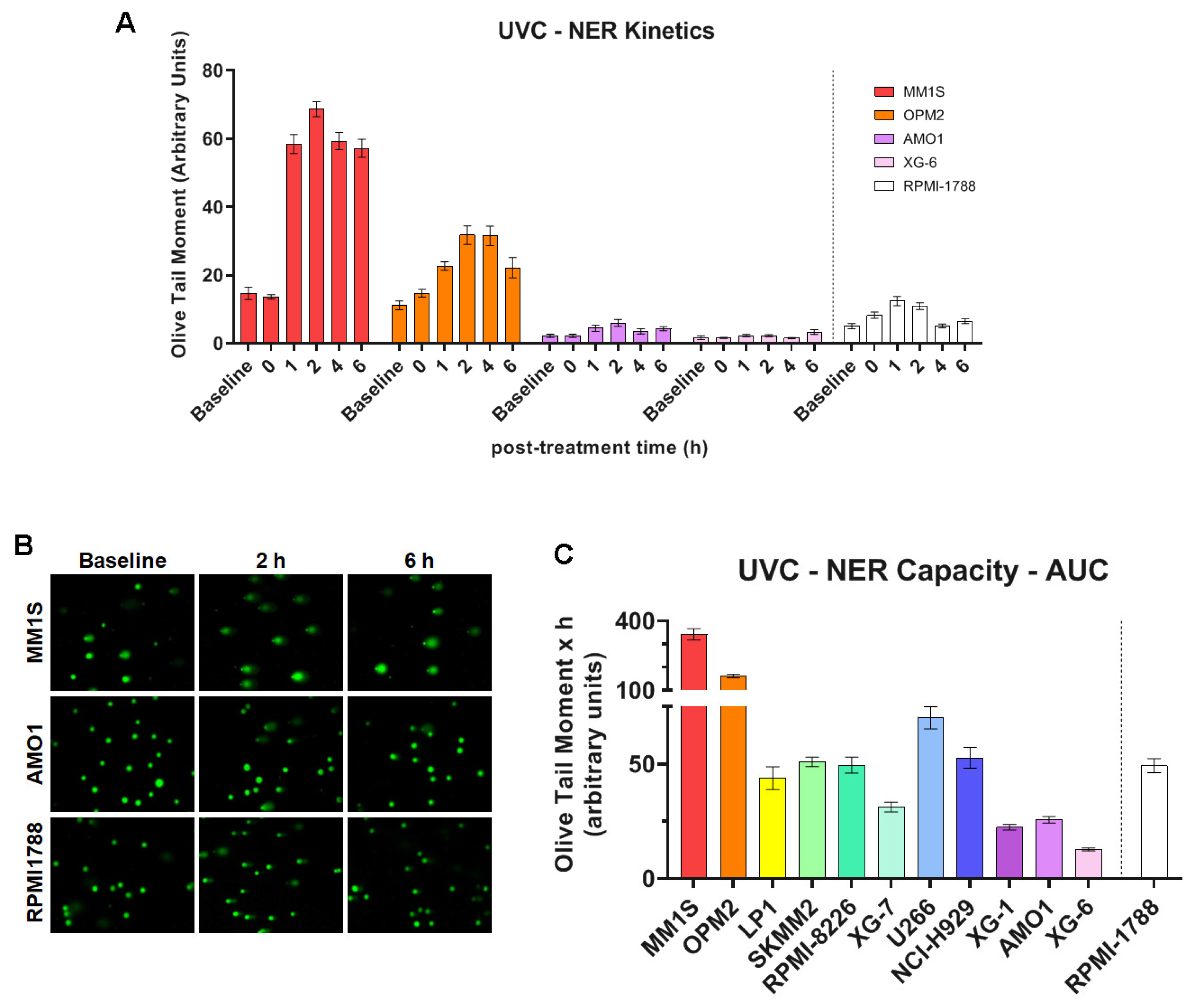

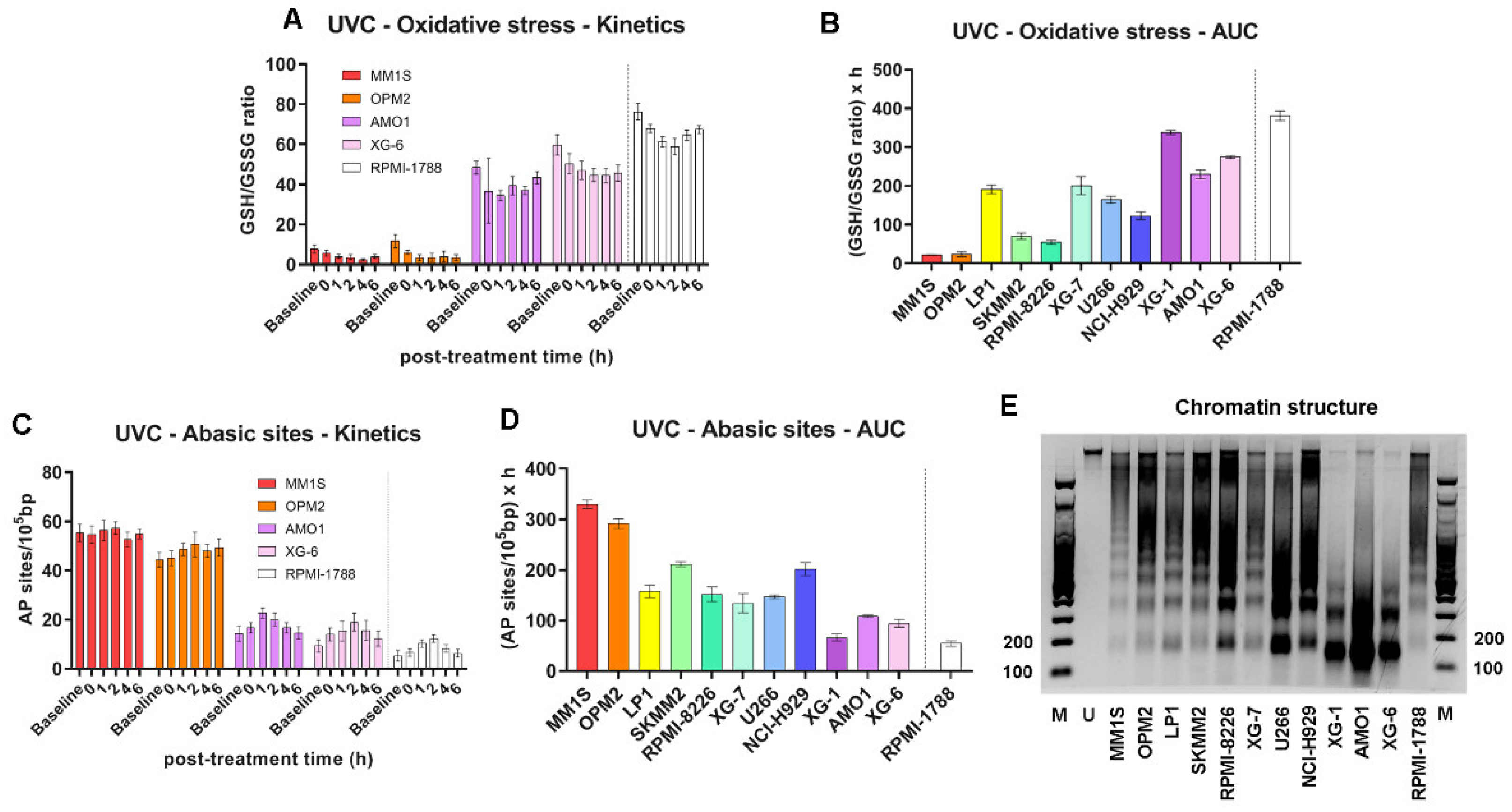

2.3. NER Capacity of MM Cell Lines

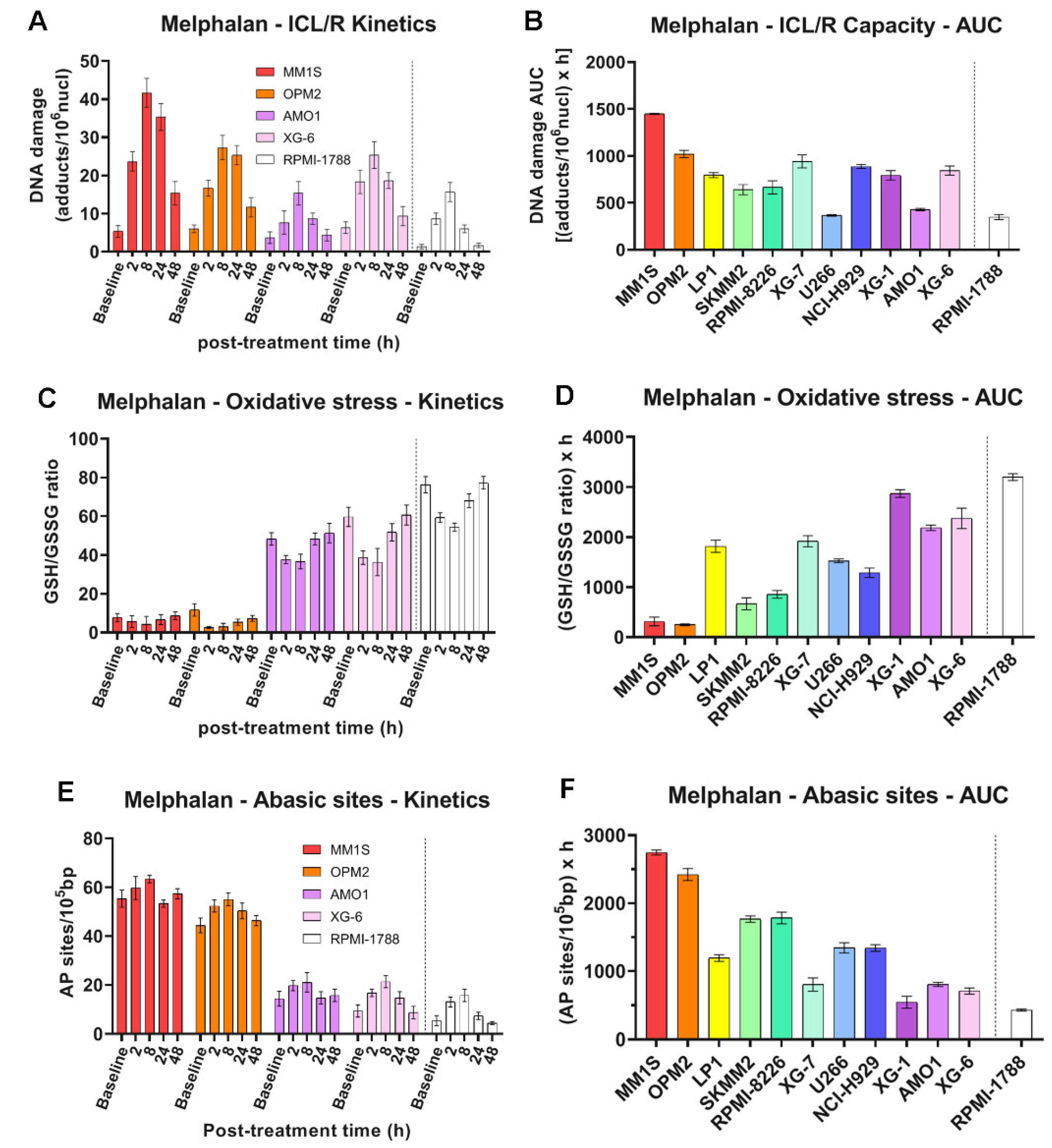

2.4. ICL Formation and Repair Capabilities in MM Cell Lines

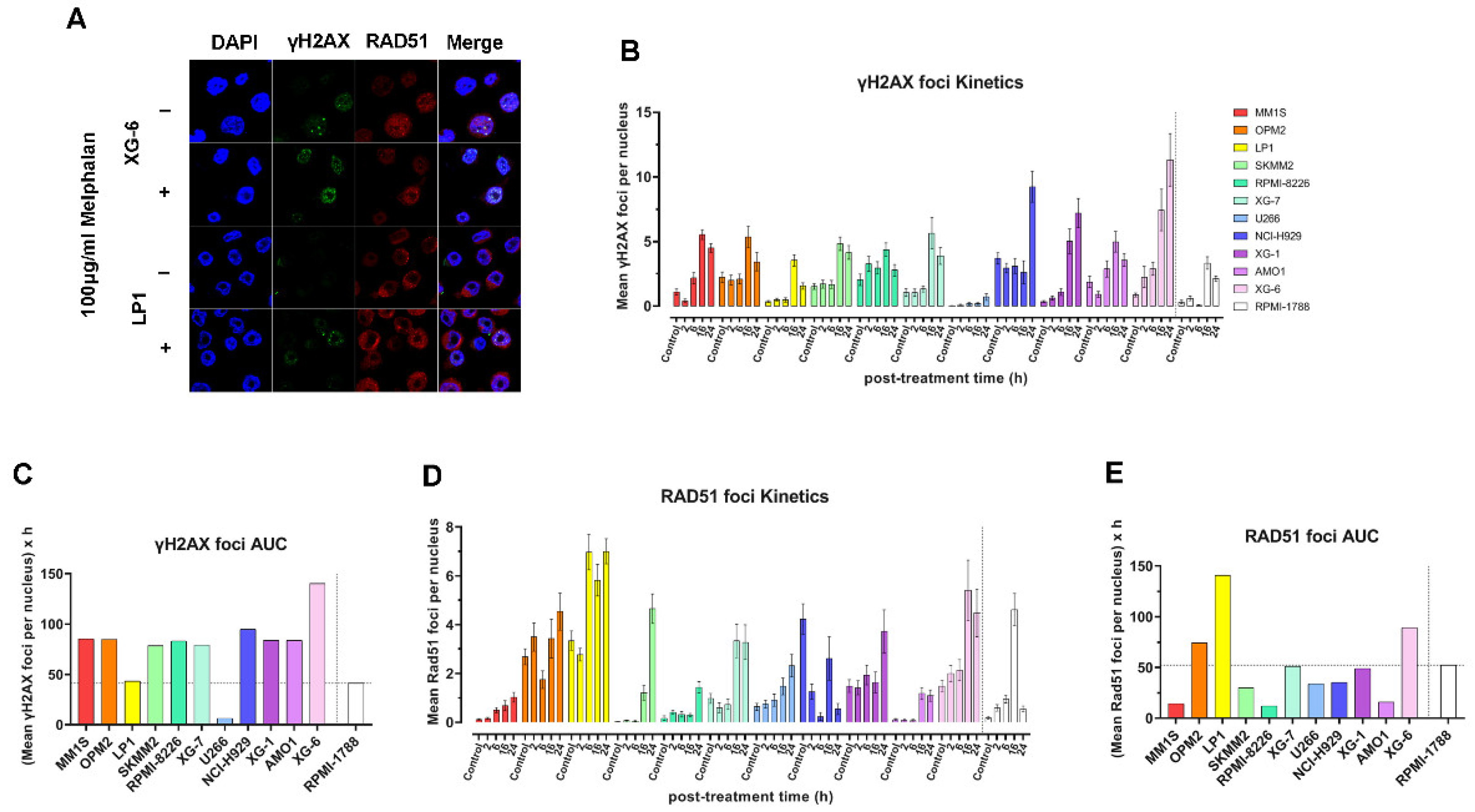

2.5. DSB Repair Capacity of MM Cell Lines

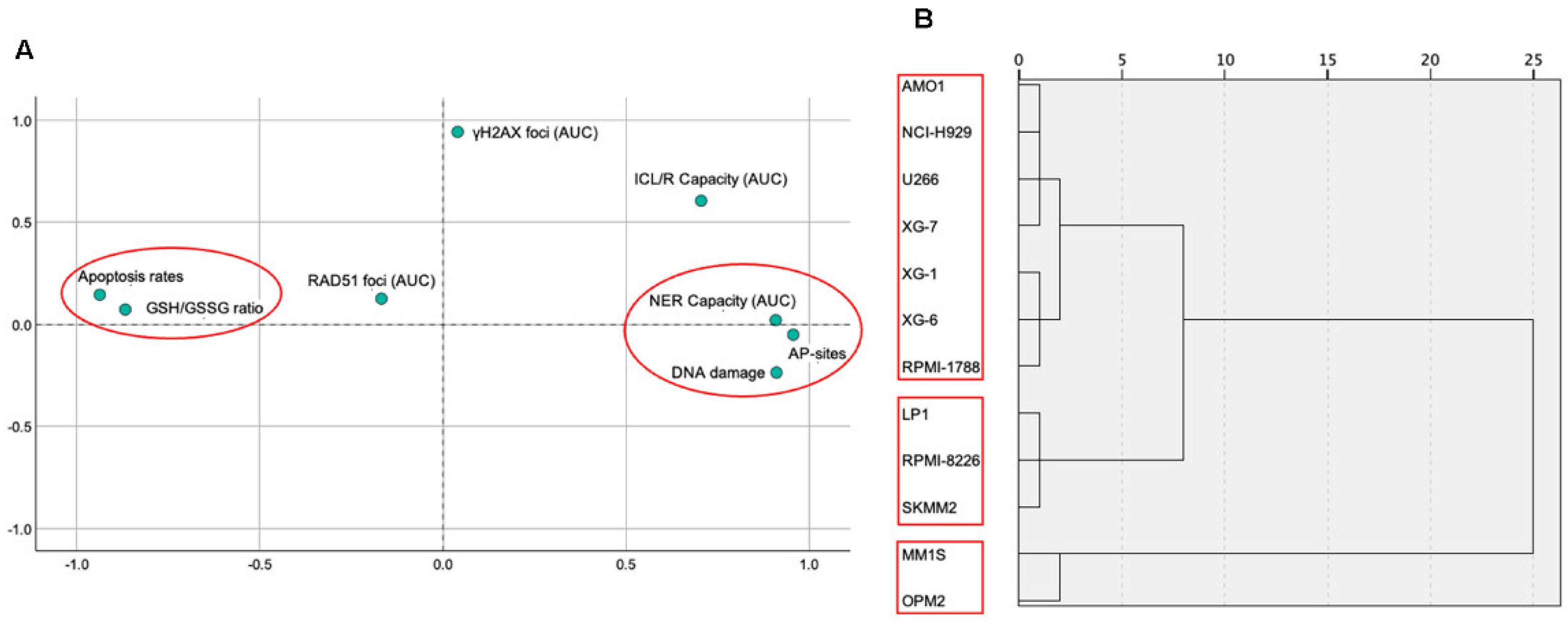

2.6. Statistical Analysis of DDR Parameters Across MM Cell Lines

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines

4.2. MTT Viability Assay

4.3. Measurement of NER

4.4. Measurement of ICL Repair

4.5. Measurement of DSB Repair

4.6. Oxidative Stress and Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Sites Assessment

4.7. Apoptosis Rates

4.8. Measurement of Chromatin Condensation

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saade, C.; Ghobrial, I.M. Updates on Mechanisms of Disease Progression in Precursor Myeloma: Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undermined Significance and Smoldering Myeloma. Presse Méd. 2025, 54, 104268. [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R.A.; Larson, D.R.; Therneau, T.M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kumar, S.; Cerhan, J.R.; Rajkumar, S.V. Long-Term Follow-up of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 241–249. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V. Multiple Myeloma: 2022 Update on Diagnosis, Risk Stratification, and Management. Am. J. Hematol. 2022, 97, 1086–1107. [CrossRef]

- Kazandjian, D. Multiple Myeloma Epidemiology and Survival: A Unique Malignancy. Semin. Oncol. 2016, 43, 676–681. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, H.; Novis Durie, S.; Meckl, A.; Hinke, A.; Durie, B. Multiple Myeloma Incidence and Mortality Around the Globe; Interrelations Between Health Access and Quality, Economic Resources, and Patient Empowerment. Oncologist 2020, 25, e1406–e1413. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, R.; Abouzaid, S.; Bonafede, M.; Cai, Q.; Parikh, K.; Cosler, L.; Richardson, P. Trends in Overall Survival and Costs of Multiple Myeloma, 2000–2014. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1915–1921. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.J.; Walker, B.A.; Davies, F.E. The Genetic Architecture of Multiple Myeloma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 335–348. [CrossRef]

- Malamos, P.; Papanikolaou, C.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Terpos, E.; Souliotis, V.L. The Interplay between the DNA Damage Response (DDR) Network and the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling Pathway in Multiple Myeloma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6991. [CrossRef]

- Elbezanti, W.O.; Challagundla, K.B.; Jonnalagadda, S.C.; Budak-Alpdogan, T.; Pandey, M.K. Past, Present, and a Glance into the Future of Multiple Myeloma Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 415. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.M.L.; Zub, K.A.; Aas, P.A.; Hanssen-Bauer, A.; Demirovic, A.; Sarno, A.; Tian, E.; Liabakk, N.B.; Slupphaug, G. An Inverse Switch in DNA Base Excision and Strand Break Repair Contributes to Melphalan Resistance in Multiple Myeloma Cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55493. [CrossRef]

- Zub, K.A.; Sousa, M.M.L. de; Sarno, A.; Sharma, A.; Demirovic, A.; Rao, S.; Young, C.; Aas, P.A.; Ericsson, I.; Sundan, A.; et al. Modulation of Cell Metabolic Pathways and Oxidative Stress Signaling Contribute to Acquired Melphalan Resistance in Multiple Myeloma Cells. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0119857. [CrossRef]

- Petrilla, C.; Galloway, J.; Kudalkar, R.; Ismael, A.; Cottini, F. Understanding DNA Damage Response and DNA Repair in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 4155. [CrossRef]

- Besse, A.; Besse, L.; Kraus, M.; Mendez-Lopez, M.; Bader, J.; Xin, B.-T.; Bruin, G. de; Maurits, E.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Driessen, C. Proteasome Inhibition in Multiple Myeloma: Head-to-Head Comparison of Currently Available Proteasome Inhibitors. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 340-351.e3. [CrossRef]

- Holstein, S.A.; McCarthy, P.L. Immunomodulatory Drugs in Multiple Myeloma: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Experience. Drugs 2017, 77, 505–520. [CrossRef]

- Sammartano, V.; Franceschini, M.; Fredducci, S.; Caroni, F.; Ciofini, S.; Pacelli, P.; Bocchia, M.; Gozzetti, A. Anti-BCMA Novel Therapies for Multiple Myeloma. Cancer Drug Resist. 2023, 6, 169–181. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R.H.; Lonial, S. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Multiple Myeloma: A Comprehensive Review of Current Data and Implications for Clinical Practice. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 275–285. [CrossRef]

- Devarakonda, S.; Efebera, Y.; Sharma, N. Role of Stem Cell Transplantation in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2021, 13, 863. [CrossRef]

- Lipchick, B.C.; Fink, E.E.; Nikiforov, M.A. Oxidative Stress and Proteasome Inhibitors in Multiple Myeloma. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 105, 210–215. [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou, S.; Kapetanou, M.; Magouritsas, M.G.; Mougkolia, N.; Taouxidou, P.; Papacharalambous, M.; Sakellaridis, F.; Gonos, E. Antioxidant and Antiaging Properties of a Novel Synergistic Nutraceutical Complex: Readouts from an In Cellulo Study and an In Vivo Prospective, Randomized Trial. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 468. [CrossRef]

- Caillot, M.; Dakik, H.; Mazurier, F.; Sola, B. Targeting Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism to Induce Myeloma Cell Death. Cancers 2021, 13, 2411. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Chng, W.-J.; Zhou, J. Crosstalk between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Oxidative Stress: A Dynamic Duo in Multiple Myeloma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 3883–3906. [CrossRef]

- Kul, A.N.; Ozturk Kurt, B. Multiple Myeloma from the Perspective of Pro- and Anti-Oxidative Parameters: Potential for Diagnostic and/or Follow-Up Purposes? J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 221. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Walker, G.C. Mechanisms of DNA Damage, Repair, and Mutagenesis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2017, 58, 235–263. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.J. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 547–560. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, T.; Oda, T. DNA Damage Response in Multiple Myeloma: The Role of the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2021, 13, 504. [CrossRef]

- Alagpulinsa, D.A.; Szalat, R.E.; Poznansky, M.C.; Reis, R.J.S. Genomic Instability in Multiple Myeloma. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 858–873. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Heuck, C.J.; Fazzari, M.J.; Mehta, J.; Singhal, S.; Greally, J.M.; Verma, A. DNA Methylation Alterations in Multiple Myeloma as a Model for Epigenetic Changes in Cancer. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2010, 2, 654–669. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Hu, W.; Chasin, L.A.; Tang, M. Effects of Genomic Context and Chromatin Structure on Transcription-coupled and Global Genomic Repair in Mammalian Cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 5897–5906. [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, C.; Economopoulou, P.; Spathis, A.; Kotsantis, I.; Gavrielatou, N.; Anastasiou, M.; Moutafi, M.; Kyriazoglou, A.; Foukas, G.-R.P.; Lelegiannis, I.M.; et al. Association of DNA Damage Response Signals and Oxidative Stress Status with Nivolumab Efficacy in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 133, 353-364. [CrossRef]

- Gkotzamanidou, M.; Terpos, E.; Bamia, C.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Souliotis, V.L. Progressive Changes in Chromatin Structure and DNA Damage Response Signals in Bone Marrow and Peripheral Blood during Myelomagenesis. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1113–1121. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lai, Y.; Hua, Z.-C. Apoptosis and Apoptotic Body: Disease Message and Therapeutic Target Potentials. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20180992. [CrossRef]

- Enoiu, M.; Jiricny, J.; Schärer, O.D. Repair of Cisplatin-Induced DNA Interstrand Crosslinks by a Replication-Independent Pathway Involving Transcription-Coupled Repair and Translesion Synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 8953–8964. [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, V.L.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Sfikakis, P.P. Gene-Specific Formation and Repair of DNA Monoadducts and Interstrand Cross-Links after Therapeutic Exposure to Nitrogen Mustards. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 4465–4474.

- Herrero, A.B.; Gutiérrez, N.C. Targeting Ongoing DNA Damage in Multiple Myeloma: Effects of DNA Damage Response Inhibitors on Plasma Cell Survival. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 98. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gkotzamanidou, M.; Talluri, S.; Day, M.; Neptune, M.; Potluri, L.B.; Chakraborty, C.; Mills, K.; Shammas, M.A.; Munshi, N.C. Ongoing Spontaneous DNA Damage Creates Synthetic Lethality Targeted By Novel RAD51 Inhibitors in Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2019, 134, 4378. [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.K.; Wu, X.; Tschumper, R.C.; Arendt, B.K.; Huddleston, P.M.; Henderson, K.J.; Dispenzieri, A.; Jelinek, D.F. Evidence for Ongoing DNA Damage in Multiple Myeloma Cells as Revealed by Constitutive Phosphorylation of H2AX. Leukemia 2011, 25, 1344–1353. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Takada, K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer: Current Findings and Future Directions. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3945–3952. [CrossRef]

- Attique, I.; Haider, Z.; Khan, M.; Hassan, S.; Soliman, M.M.; Ibrahim, W.N.; Anjum, S. Reactive Oxygen Species: From Tumorigenesis to Therapeutic Strategies in Cancer. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e70947. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lin, D.; Peng, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, J.; Gu, J. Cancer-Derived Immunoglobulin G Promotes Tumor Cell Growth and Proliferation through Inducing Production of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e945–e945. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-H.; Yin, H.; Marincas, M.; Xie, L.-L.; Bu, L.-L.; Guo, M.-H.; Zheng, X.-L. From DNA Repair to Redox Signaling: The Multifaceted Role of APEX1 (Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Endonuclease 1) in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3034. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.S.; Cortez, D. New Insights into Abasic Site Repair and Tolerance. DNA Repair (Amst) 2020, 90, 102866. [CrossRef]

- Mavroeidi, D.; Georganta, A.; Stefanou, D.T.; Papanikolaou, C.; Syrigos, K.N.; Souliotis, V.L. DNA Damage Response Network and Intracellular Redox Status in the Clinical Outcome of Patients with Lung Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 4218. [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, C.; Economopoulou, P.; Gavrielatou, N.; Mavroeidi, D.; Psyrri, A.; Souliotis, V.L. UVC-Induced Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage Repair Status in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients with Different Responses to Nivolumab Therapy. Biology 2025, 14, 195. [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, V.L.; Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Pappa, M.; Argyriou, A.; Ntouros, P.A.; Sfikakis, P.P. DNA Damage Response and Oxidative Stress in Systemic Autoimmunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 55. [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Pappa, M.; Ntouros, P.A.; Nezos, A.; Mavragani, C.P.; Souliotis, V.L.; Sfikakis, P.P. Association Between DNA Damage Response, Fibrosis and Type I Interferon Signature in Systemic Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 582401. [CrossRef]

- Szalat, R.; Samur, M.K.; Fulciniti, M.; Lopez, M.; Nanjappa, P.; Cleynen, A.; Wen, K.; Kumar, S.; Perini, T.; Calkins, A.S.; et al. Nucleotide Excision Repair Is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Multiple Myeloma. Leukemia 2018, 32, 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Deans, A.J.; West, S.C. DNA Interstrand Crosslink Repair and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 467–480. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Solanki, A.; Ghosh, K.; Vundinti, B.R. DNA Interstrand Cross-Link Repair: Understanding Role of Fanconi Anemia Pathway and Therapeutic Implications. Eur. J. Haematol. 2013, 91, 381–393. [CrossRef]

- Herrero, A.B.; Miguel, J.S.; Gutierrez, N.C. Deregulation of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Multiple Myeloma: Implications for Genome Stability. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0121581. [CrossRef]

- Gourzones-Dmitriev, C.; Kassambara, A.; Sahota, S.; Rème, T.; Moreaux, J.; Bourquard, P.; Hose, D.; Pasero, P.; Constantinou, A.; Klein, B. DNA Repair Pathways in Human Multiple Myeloma. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2760–2773. [CrossRef]

- Gillyard, T.; Davis, J. Chapter Two - DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Cancer: A Path to Achieving Precision Medicine. In International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology; Weyemi, U., Galluzzi, L., Eds.; Chromatin and Genomic Instability in Cancer; Academic Press, 2021; Volume 364, pp. 111–137.

- Chakraborty, C.; Mukherjee, S. Molecular Crosstalk between Chromatin Remodeling and Tumor Microenvironment in Multiple Myeloma. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 9535–9549. [CrossRef]

- Ohguchi, H.; Hideshima, T.; Anderson, K.C. The Biological Significance of Histone Modifiers in Multiple Myeloma: Clinical Applications. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 83. [CrossRef]

- Tigu, A.B.; Ivancuta, A.; Uhl, A.; Sabo, A.C.; Nistor, M.; Mureșan, X.-M.; Cenariu, D.; Timis, T.; Diculescu, D.; Gulei, D. Epigenetic Therapies in Melanoma—Targeting DNA Methylation and Histone Modification. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1188. [CrossRef]

- Avramis, I.A.; Christodoulopoulos, G.; Suzuki, A.; Laug, W.E.; Gonzalez-Gomez, I.; McNamara, G.; Sausville, E.A.; Avramis, V.I. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluations of the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor NSC 680410 against Human Leukemia and Glioblastoma Cell Lines. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2002, 50, 479–489. [CrossRef]

- Lapytsko, A.; Kollarovic, G.; Ivanova, L.; Studencka, M.; Schaber, J. FoCo: A Simple and Robust Quantification Algorithm of Nuclear Foci. BMC Bioinformatics 2015, 16, 392. [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, V.L.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Episkopou, H.G.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Sfikakis, P.P. Preferential in Vivo DNA Repair of Melphalan-Induced Damage in Human Genes Is Greatly Affected by the Local Chromatin Structure. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006, 5, 972–985. [CrossRef]

| Apoptosis rates |

DNA damage |

GSH/GSSG ratio |

AP-sites | NER Capacity (AUC) |

ICL/R Capacity (AUC) |

γH2AX foci (AUC) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA damage | -.918** | ||||||

| GSH/GSSG ratio | .792** | -.804** | |||||

| AP-sites | -.864** | .864** | -.814** | ||||

| NER Capacity (AUC)# | -.792** | .762** | -.648* | .892** | |||

| ICL/R Capacity (AUC) | -.617* | 0.456 | -0.485 | .592* | .707* | ||

| γH2AX foci (AUC) | 0.135 | -0.145 | -0.053 | 0.021 | -0.003 | 0.483 | |

| RAD51 foci (AUC) | -0.032 | -0.033 | 0.286 | -0.215 | -0.244 | 0.073 | -0.03 |

| ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed); * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); # AUC: Area Under the Curve | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).