Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Cell Lines

2.3. Measurement of Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER) – Alkaline Comet Assay

2.4. Measurement of the Interstrand Cross-Links Repair

2.5. GSH/GSSG Ratio and Abasic Sites

2.6. Apoptosis Rates

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

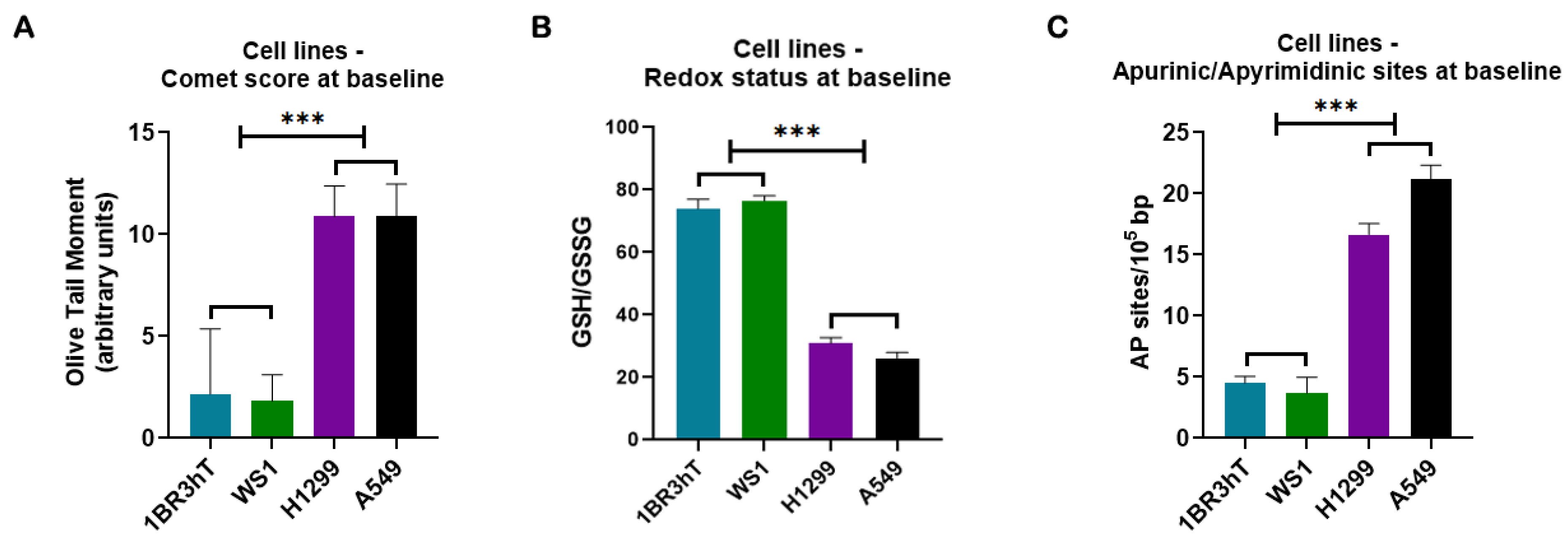

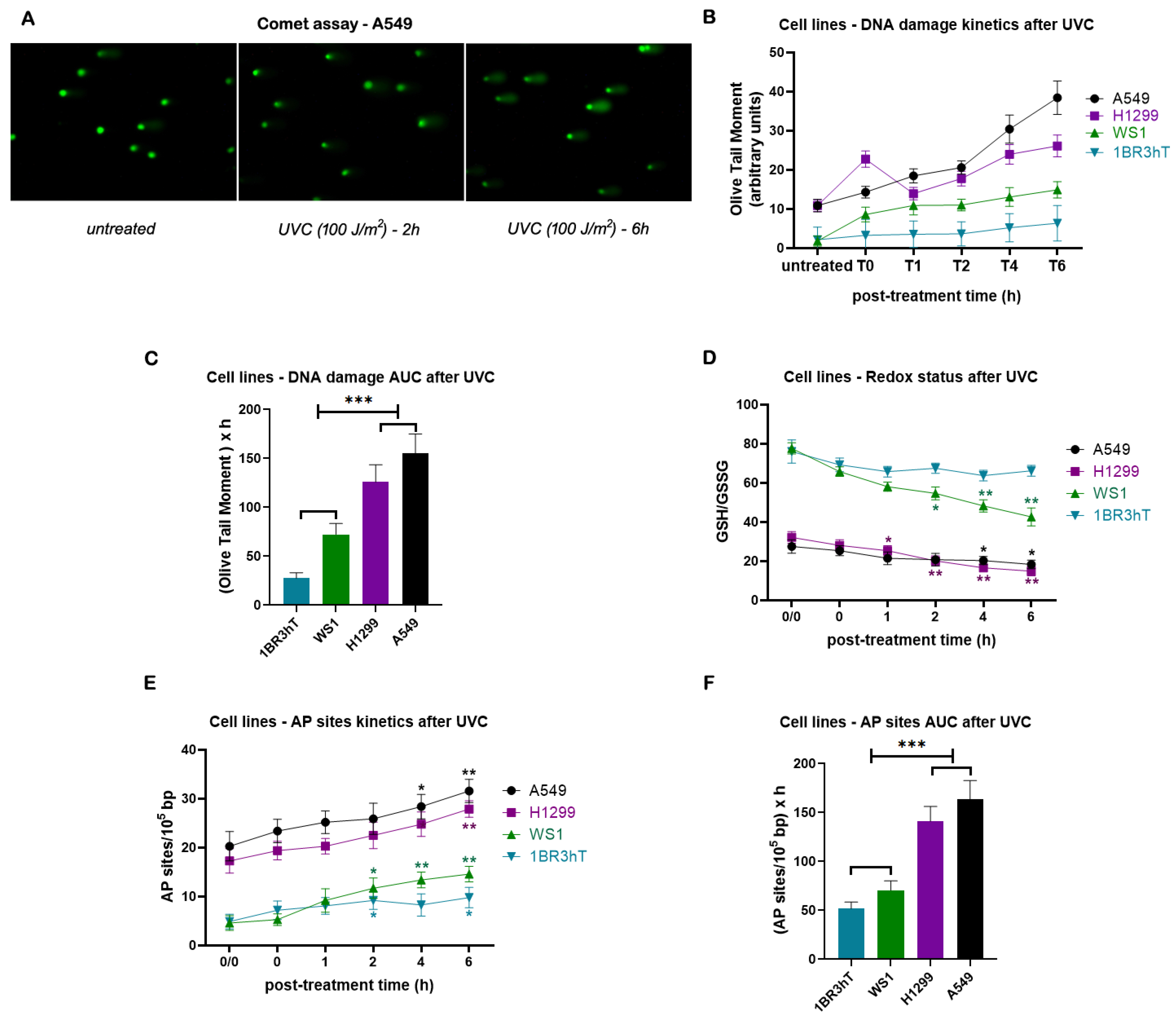

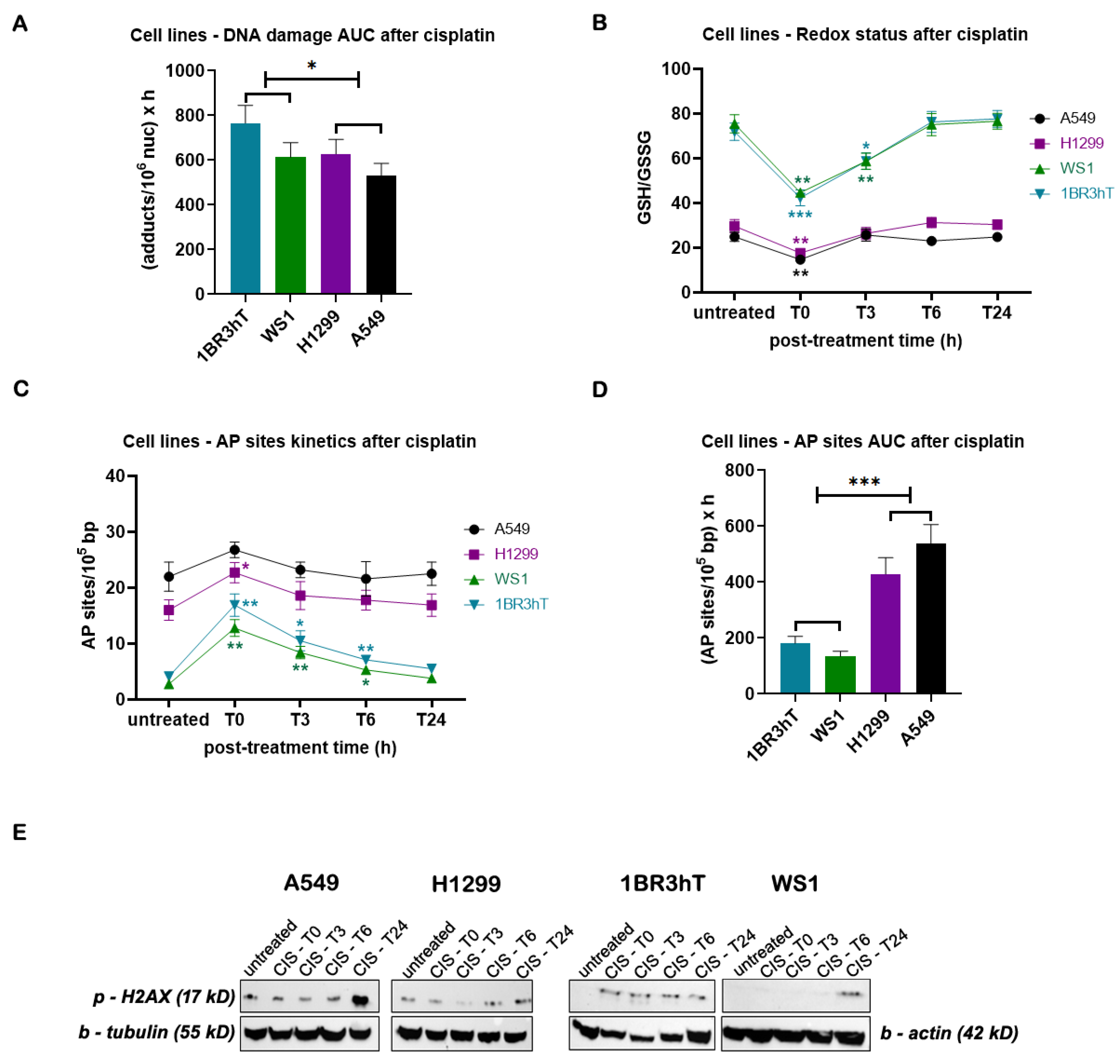

3.1. DDR-Associated Parameters in Lung Cancer Cell Lines

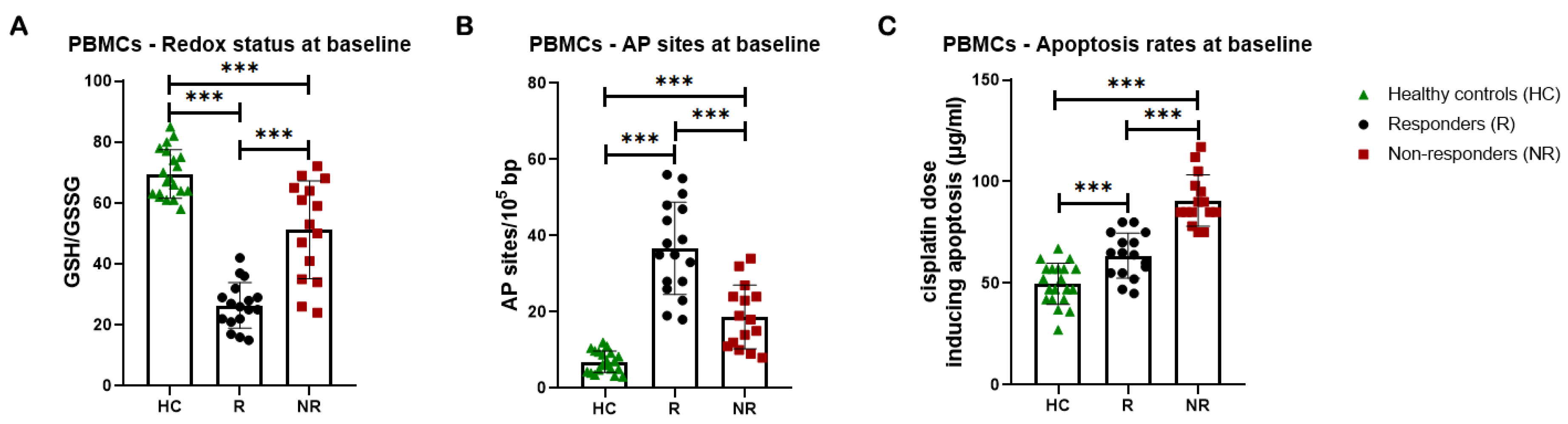

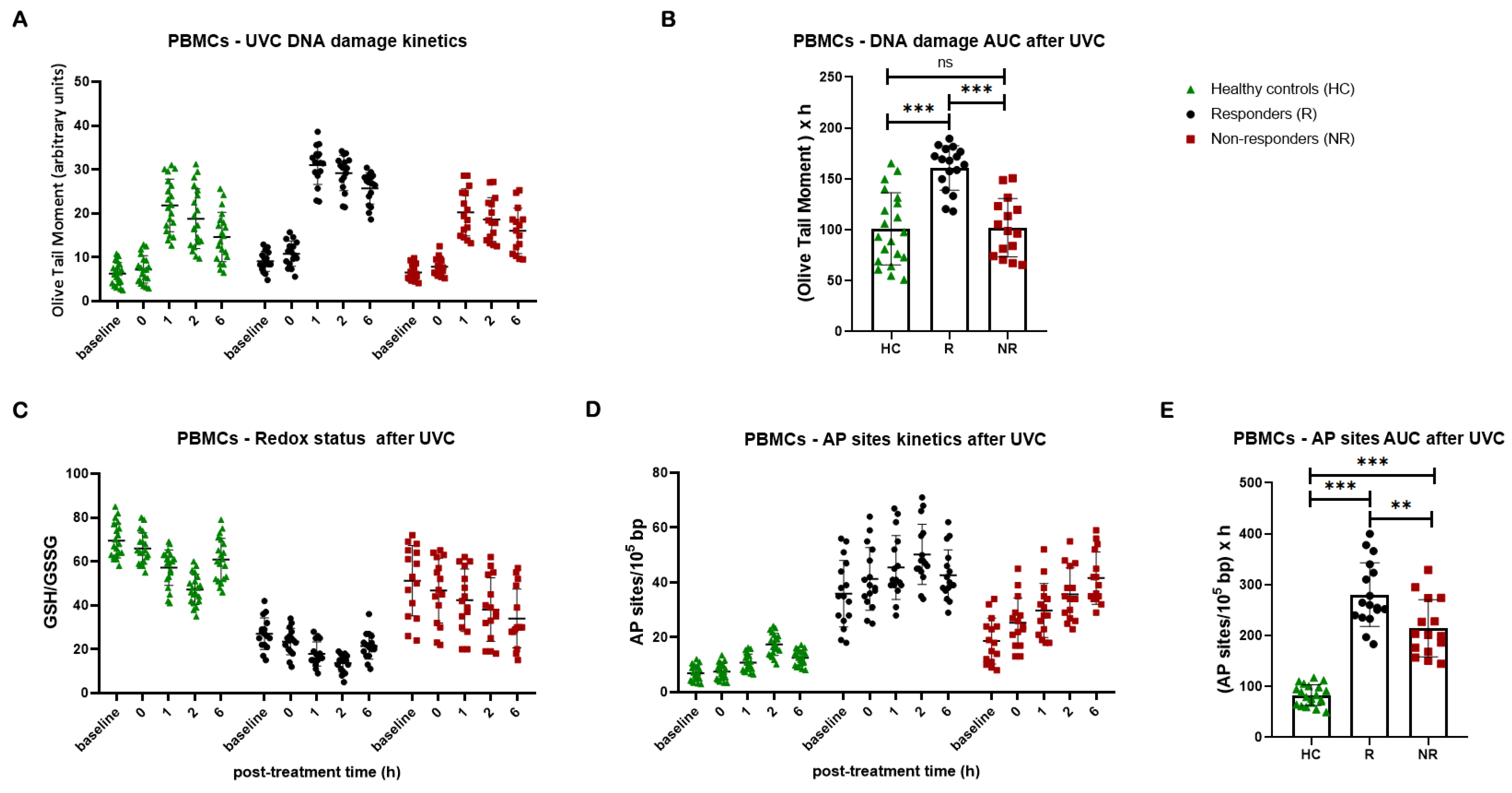

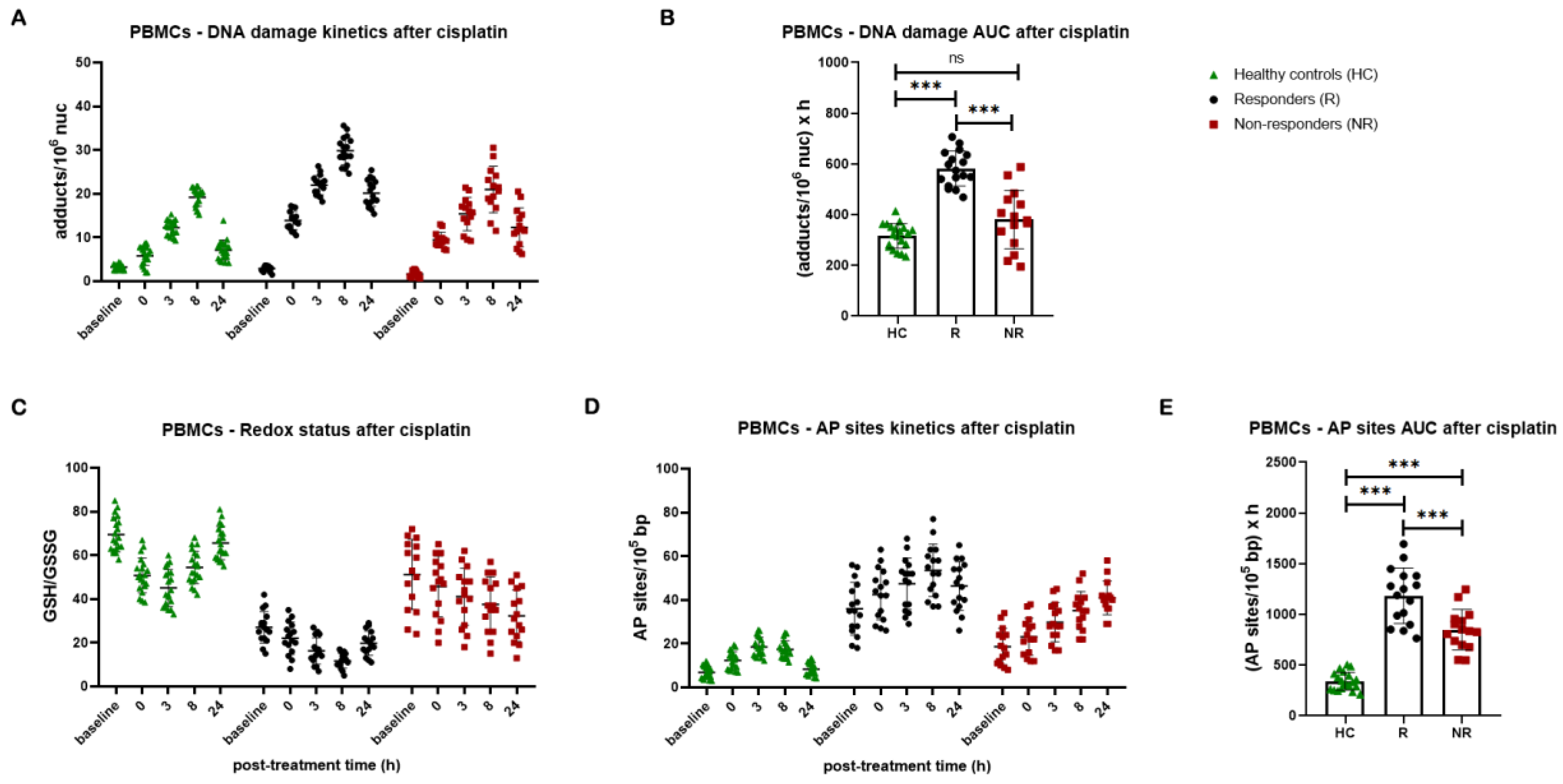

3.2. DDR Signals in PBMCs from Lung Cancer Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thai, A.A.; Solomon, B.J.; Sequist, L.V.; Gainor, J.F.; Heist, R.S. Lung Cancer. The Lancet 2021, 398, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yan, B.; He, S. Advances and Challenges in the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 169, 115891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, C.R.; Mazzone, P.J. Biomarkers in Lung Cancer. Clinics in Chest Medicine 2020, 41, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hecht, S.S. Carcinogenic Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke: A 2022 Update. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2022, 165, 113179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrales, L.; Rosell, R.; Cardona, A.F.; Martín, C.; Zatarain-Barrón, Z.L.; Arrieta, O. Lung Cancer in Never Smokers: The Role of Different Risk Factors Other than Tobacco Smoking. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2020, 148, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, J.C.; García-Pardo, M.; Alessi, J.; Barrios, C.; Singh, N.; Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Loong, H.; Ferriol, M.; Recondo, G.; Mezquita, L. Geographic Differences in Lung Cancer: Focus on Carcinogens, Genetic Predisposition, and Molecular Epidemiology. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2024, 16, 17588359241231260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.; Wagner, J.R. DNA Base Damage by Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidizing Agents, and UV Radiation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2013, 5, a012559–a012559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Walker, G.C. Mechanisms of DNA Damage, Repair, and Mutagenesis. Environ and Mol Mutagen 2017, 58, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houten, B.; Santa-Gonzalez, G.A.; Camargo, M. DNA Repair after Oxidative Stress: Current Challenges. Current Opinion in Toxicology 2018, 7, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganai, R.A.; Johansson, E. DNA Replication—A Matter of Fidelity. Molecular Cell 2016, 62, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubbs, A.; Nussenzweig, A. Endogenous DNA Damage as a Source of Genomic Instability in Cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. The Role of ROS in Tumour Development and Progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2022, 22, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Lian, G. ROS and Diseases: Role in Metabolism and Energy Supply. Mol Cell Biochem 2020, 467, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, A.; Simon, M.C. Glutathione Metabolism in Cancer Progression and Treatment Resistance. Journal of Cell Biology 2018, 217, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, Y.C. Impact of Oxidative Stress on Lung Diseases. Respirology 2009, 14, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dizdaroglu, M. Oxidatively Induced DNA Damage: Mechanisms, Repair and Disease. Cancer Letters 2012, 327, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaudin, X. Reactive Oxygen Species and DNA Damage Response in Cancer. In International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology; Elsevier, 2021; Vol. 364, pp. 139–161 ISBN 978-0-323-85561-7.

- Souliotis, V.L.; Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Pappa, M.; Argyriou, A.; Ntouros, P.A.; Sfikakis, P.P. DNA Damage Response and Oxidative Stress in Systemic Autoimmunity. IJMS 2019, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shen, J.; Deininger, P.; Hunt, J.D. Abasic Sites and Survival in Resected Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Letters 2007, 246, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.; Gu, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, E.; Zhang, Y.; He, L.; Pan, F.; Guo, Z.; Hu, Z. Small-Molecule Inhibition of APE1 Induces Apoptosis, Pyroptosis, and Necroptosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, M.; Hägg, M.; Panaretakis, T.; Havelka, A.M.; Shoshan, M.C.; Linder, S. Acute Apoptosis by Cisplatin Requires Induction of Reactive Oxygen Species but Is Not Associated with Damage to Nuclear DNA. Intl Journal of Cancer 2007, 120, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lian, W.; Yuan, Y.; Li, M. The Synergistic Effects of Oxaliplatin and Piperlongumine on Colorectal Cancer Are Mediated by Oxidative Stress. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loenhout, J.; Peeters, M.; Bogaerts, A.; Smits, E.; Deben, C. Oxidative Stress-Inducing Anticancer Therapies: Taking a Closer Look at Their Immunomodulating Effects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadoni, E.; Valletta, E.; Caddeo, G.; Isaia, F.; Cabiddu, M.G.; Vascellari, S.; Pivetta, T. Competitive Reactions among Glutathione, Cisplatin and Copper-Phenanthroline Complexes. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 2017, 173, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamali, B.; Nakhjavani, M.; Hosseinzadeh, L.; Amidi, S.; Nikounezhad, N.; Shirazi, F.H. Intracellular GSH Alterations and Its Relationship to Level of Resistance Following Exposure to Cisplatin in Cancer Cells. 2015.

- Li, S.; Li, C.; Jin, S.; Liu, J.; Xue, X.; Eltahan, A.S.; Sun, J.; Tan, J.; Dong, J.; Liang, X.-J. Overcoming Resistance to Cisplatin by Inhibition of Glutathione S-Transferases (GSTs) with Ethacraplatin Micelles in Vitro and in Vivo. Biomaterials 2017, 144, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.H.W.; Kuo, M.T. Role of Glutathione in the Regulation of Cisplatin Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy. Metal-Based Drugs 2010, 2010, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasherman, Y.; Sturup, S.; Gibson, D. Is Glutathione the Major Cellular Target of Cisplatin? A Study of the Interactions of Cisplatin with Cancer Cell Extracts. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4319–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.M.; Rocha, C.R.R.; Kinker, G.S.; Pelegrini, A.L.; Menck, C.F.M. The Balance between NRF2/GSH Antioxidant Mediated Pathway and DNA Repair Modulates Cisplatin Resistance in Lung Cancer Cells. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 17639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascellari, S.; Valletta, E.; Perra, D.; Pinna, E.; Serra, A.; Isaia, F.; Pani, A.; Pivetta, T. Cisplatin, Glutathione and the Third Wheel: A Copper-(1,10-Phenanthroline) Complex Modulates Cisplatin–GSH Interactions from Antagonism to Synergism in Cancer Cells Resistant to Cisplatin. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 5362–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon Barroeta, P.; O’Sullivan, M.J.; Zisterer, D.M. The Role of the Nrf2/GSH Antioxidant System in Cisplatin Resistance in Malignant Rhabdoid Tumours. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 8379–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.; Mills, K. The DNA Damage Repair Response. COO 2020, 03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.P.; Bartek, J. The DNA-Damage Response in Human Biology and Disease. Nature 2009, 461, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiehchen, D.; Hsieh, A.; Samstein, R.M.; Lu, T.; Beg, M.S.; Gerber, D.E.; Wang, T.; Morris, L.G.T.; Zhu, H. DNA Repair Gene Mutations as Predictors of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response beyond Tumor Mutation Burden. Cell Reports Medicine 2020, 1, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Nowsheen, S.; Deng, M. DNA Repair Deficiency Regulates Immunity Response in Cancers: Molecular Mechanism and Approaches for Combining Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härtlova, A.; Erttmann, S.F.; Raffi, F.A.; Schmalz, A.M.; Resch, U.; Anugula, S.; Lienenklaus, S.; Nilsson, L.M.; Kröger, A.; Nilsson, J.A.; et al. DNA Damage Primes the Type I Interferon System via the Cytosolic DNA Sensor STING to Promote Anti-Microbial Innate Immunity. Immunity 2015, 42, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Bakhoum, S.F. The Cytosolic DNA-Sensing cGAS–STING Pathway in Cancer. Cancer Discovery 2020, 10, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilger, D.; Seymour, L.W.; Jackson, S.P. Interfaces between Cellular Responses to DNA Damage and Cancer Immunotherapy. Genes Dev. 2021, 35, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Di Maio, M. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Optimal Number of Treatment Cycles. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 2016, 16, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, M.; Ntouros, P.A.; Papanikolaou, C.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Souliotis, V.L.; Tektonidou, M.G. Augmented Oxidative Stress, Accumulation of DNA Damage and Impaired DNA Repair Mechanisms in Thrombotic Primary Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Clinical Immunology 2023, 254, 109693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, V.L.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Episkopou, H.G.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Sfikakis, P.P. Preferential in Vivo DNA Repair of Melphalan-Induced Damage in Human Genes Is Greatly Affected by the Local Chromatin Structure. DNA Repair 2006, 5, 972–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharer, O.D. Nucleotide Excision Repair in Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2013, 5, a012609–a012609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, D.T.; Kouvela, M.; Stellas, D.; Voutetakis, K.; Papadodima, O.; Syrigos, K.; Souliotis, V.L. Oxidative Stress and Deregulated DNA Damage Response Network in Lung Cancer Patients. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahlaei, M. Platinum-Based Drugs in Cancer Treatment: Expanding Horizons and Overcoming Resistance. Journal of Molecular Structure 2023, 1301, 137366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, D.T.; Souliotis, V.L.; Zakopoulou, R.; Liontos, M.; Bamias, A. DNA Damage Repair: Predictor of Platinum Efficacy in Ovarian Cancer? Biomedicines 2021, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peddireddy, V.; Siva Prasad, B.; Gundimeda, S.D.; Penagaluru, P.R.; Mundluru, H.P. Assessment of 8-Oxo-7, 8-Dihydro-2′-Deoxyguanosine and Malondialdehyde Levels as Oxidative Stress Markers and Antioxidant Status in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biomarkers 2012, 17, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, S.; Golubnitschaja, O.; Zhan, X. Chronic Inflammation: Key Player and Biomarker-Set to Predict and Prevent Cancer Development and Progression Based on Individualized Patient Profiles. EPMA Journal 2019, 10, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.-M.; Zavitz, C.C.J.; Chen, B.; Kianpour, S.; Wan, Y.; Stämpfli, M.R. Cigarette Smoke Impairs NK Cell-Dependent Tumor Immune Surveillance. The Journal of Immunology 2007, 178, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yin, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Zha, Z.; Ke, W.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Ge, Z. Intracellular Glutathione-Depleting Polymeric Micelles for Cisplatin Prodrug Delivery to Overcome Cisplatin Resistance of Cancers. Journal of Controlled Release 2018, 273, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Senovilla, L.; Vitale, I.; Michels, J.; Martins, I.; Kepp, O.; Castedo, M.; Kroemer, G. Molecular Mechanisms of Cisplatin Resistance. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1869–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Fang, J. Combination of Chemotherapy and Oxidative Stress to Enhance Cancer Cell Apoptosis. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 3215–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Seo, Y.R. Understanding of ROS-Inducing Strategy in Anticancer Therapy. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2019, 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-I.; Lu, T.-Y.; Yang, Y.-C.; Chang, S.-H.; Chen, H.-H.; Lu, I.-L.; Sabu, A.; Chiu, H.-C. New Combination Treatment from ROS-Induced Sensitized Radiotherapy with Nanophototherapeutics to Fully Eradicate Orthotopic Breast Cancer and Inhibit Metastasis. Biomaterials 2020, 257, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizami, Z.N.; Aburawi, H.E.; Semlali, A.; Muhammad, K.; Iratni, R. Oxidative Stress Inducers in Cancer Therapy: Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Kabeer, A.; Abbas, Z.; Siddiqui, H.A.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cho, W.C. Interplay of Oxidative Stress, Cellular Communication and Signaling Pathways in Cancer. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, F.-F.; Huang, S.-C.; Yu, P.-T.; Chao, T.-H.; Huang, Y.-C. Oxidative Stress Induced by Chemotherapy: Evaluation of Glutathione and Its Related Antioxidant Enzyme Dynamics in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, H.S.; Bae, C.; Wang, J.; Lee, K.-H.; Hankerd, K.M.; Kim, H.K.; Chung, J.M.; La, J.-H. Peripheral and Central Oxidative Stress in Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Mol Pain 2019, 15, 1744806919840098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Zuo, J.; Li, B.; Chen, R.; Luo, K.; Xiang, X.; Lu, S.; Huang, C.; Liu, L.; Tang, J.; et al. Drug-Induced Oxidative Stress in Cancer Treatments: Angel or Devil? Redox Biology 2023, 63, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, B.; Nice, E.C.; Xu, J.; Huang, C. Antioxidant Therapy in Cancer: Rationale and Progress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruseva, I.O.; Evdokimov, A.N.; Lavrik, O.I. Molecular Mechanism of Global Genome Nucleotide Excision Repair. Acta Naturae 2014, 6, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, N.; Goswami, M.; Han, S.G.; Clark, S.; Orren, D.K.; Gairola, C.G.; Mellon, I. Exposure of Human Lung Cells to Tobacco Smoke Condensate Inhibits the Nucleotide Excision Repair Pathway. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjo-Barreiro, J.R.; Ruano-Ravina, A.; Pérez-Ríos, M.; Kelsey, K.; Varela-Lema, L.; Torres-Durán, M.; Parente-Lamelas, I.; Provencio-Pulla, M.; Vidal-García, I.; Piñeiro-Lamas, M.; et al. Radon, Tobacco Exposure and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Risk Related to BER and NER Genetic Polymorphisms. Archivos de Bronconeumología 2022, 58, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Shi, R.; Wang, S. Chemosensitizing Effect of shRNA-Mediated ERCC1 Silencing on a Xuanwei Lung Adenocarcinoma Cell Line and Its Clinical Significance. Oncology Reports 2017, 37, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fikrova, P.; Stetina, R.; Hrnciarik, M.; Hrnciarikova, D.; Hronek, M.; Zadak, Z. DNA Crosslinks, DNA Damage and Repair in Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Platinum Derivatives. Oncology Reports 2014, 31, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobachevsky, P.N.; Bucknell, N.W.; Mason, J.; Russo, D.; Yin, X.; Selbie, L.; Ball, D.L.; Kron, T.; Hofman, M.; Siva, S.; et al. Monitoring DNA Damage and Repair in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of Lung Cancer Radiotherapy Patients. Cancers 2020, 12, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Li, F.; Sun, N.; Shukui, Q.; Baoan, C.; Jifeng, F.; Lu, C.; Zuhong, L.; Hongyan, C.; YuanDong, C.; et al. Polymorphisms in XRCC1 and XPG and Response to Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Lung Cancer 2009, 65, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Ren, S.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.; Su, C.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, J. Predictive Effects of ERCC1 and XRCC3 SNP on Efficacy of Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Advanced NSCLC Patients. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010, 40, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Han, P.; Gao, F.; Dahlstrom, K.R.; Li, G.; Owzar, K.; Zevallos, J.P.; Sturgis, E.M.; Wei, Q. Apoptotic Capacity and Risk of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. European Journal of Cancer 2017, 72, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raturi, V.P.; Wu, C.; Mohammad, S.; Hojo, H.; Bei, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Okumura, M.; Rachi, T.; Singh, R.; Gupta, R.; et al. Could Excision Repair Cross-complementing Group-1 mRNA Expression from Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes Predict Locoregional Failure with Cisplatin Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Laryngeal Cancer? Asia-Pac J Clncl Oncology 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgmann, K.; Röper, B.; El-Awady, R.A.; Brackrock, S.; Bigalke, M.; Dörk, T.; Alberti, W.; Dikomey, E.; Dahm-Daphi, J. Indicators of Late Normal Tissue Response after Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer: Fibroblasts, Lymphocytes, Genetics, DNA Repair, and Chromosome Aberrations. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2002, 64, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela-Fandino, M.; Hitt, R.; Medina, P.P.; Gamarra, S.; Manso, L.; Cortes-Funes, H.; Sanchez-Cespedes, M. DNA-Repair Gene Polymorphisms Predict Favorable Clinical Outcome Among Patients With Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck Treated With Cisplatin-Based Induction Chemotherapy. JCO 2006, 24, 4333–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, E.; Yuspa, S.H.; Zwelling, L.A.; Ozols, R.F.; Poirier, M.C. Quantitation of Cis-Diamminedichloroplatinum 11 (Cisplatin)-DNA-Lntrastrand Adducts in Testicular and Ovarian Cancer Patients Receiving Cisplatin Chemotherapy.

- Stefanou, D.T.; Bamias, A.; Episkopou, H.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Likka, M.; Kalampokas, T.; Photiou, S.; Gavalas, N.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; et al. Aberrant DNA Damage Response Pathways May Predict the Outcome of Platinum Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Souliotis, V.L.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Bamia, C.; Pouli, A.; Baltadakis, I.; Terpos, E.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Sfikakis, P.P. Melphalan-Induced DNA Damage in Vitro as a Predictor for Clinical Outcome in Multiple Myeloma. Haematologica 2007, 92, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkotzamanidou, M.; Terpos, E.; Bamia, C.; Munshi, N.C.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Souliotis, V.L. DNA Repair of Myeloma Plasma Cells Correlates with Clinical Outcome: The Effect of the Nonhomologous End-Joining Inhibitor SCR7. Blood 2016, 128, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkotzamanidou, M.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Bamia, C.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Souliotis, V.L. Chromatin Structure, Transcriptional Activity and DNA Repair Efficiency Affect the Outcome of Chemotherapy in Multiple Myeloma. Br J Cancer 2014, 111, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkotzamanidou, M.; Terpos, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Souliotis, V.L. The Combination of Panobinostat and Melphalan for the Treatment of Patients with Multiple Myeloma. IJMS 2022, 23, 15671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, D.T.; Episkopou, H.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Bamias, A.; Gkotzamanidou, M.; Bamia, C.; Liakou, C.; Bekyrou, M.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Dimopoulos, M.; et al. Development and Validation of a PCR-based Assay for the Selection of Patients More Likely to Benefit from Therapeutic Treatment with Alkylating Drugs. Brit J Clinical Pharma 2012, 74, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients (N=32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | Years | % of Total |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 24 | - | 75 |

| Female | 8 | - | 25 |

| Age | |||

| Median | - | 67.5 | - |

| Range | - | 49-82 | - |

| Histology | |||

| squamous | 10 | - | 31,3 |

| Non-squamous | 17 | - | 53,1 |

| Small cell | 5 | - | 15,6 |

| Stage | |||

| I-II / LD | 4 | - | 12,5 |

| III | 7 | - | 21,9 |

| IV | 21 | - | 65,6 |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 3 | - | 9,3 |

| Current | 3 | - | 9,3 |

| Former | 24 | - | 75 |

| PD-L1 expression | |||

| <1% | 7 | - | 21,9 |

| 1-50% | 7 | - | 21,9 |

| >50% | 7 | - | 21,9 |

| Therapy | |||

| Chemotherapy | 18 | - | 56,2 |

| Chemotherapy – Immunotherapy combination | 14 | - | 43,8 |

| Response | |||

| PR | 17 | - | 53,1 |

| SD | 5 | - | 15,6 |

| PD | 10 | - | 31,3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).