1. Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) comprises a diverse collection

of tumors that occur in the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx. These highly immune-infiltrated malignancies are defined by a tumor microenvironment (TME) that is primarily immunosuppressive [

1]. Etiologically, HNSCC is correlated with alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and infections with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) [

2]. HNSCC is a malignancy with severe impact on a patient’s quality of life, mostly due to the severe side effects of treatment [

3]. Standard treatment of HNSCC is a combination of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy [

4]. Nowadays, PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have become the revolutionized standard of treatment of recurrent/metastatic disease, either as monotherapy or in conjunction with chemotherapy agents. Thus, translational research is now focused on the content and pathophysiology of TMEs to fully characterize the unique components and interactions that impact anti-tumor immunity and to identify new biomarkers that can be used to predict the effectiveness of immunotherapy [

5].

Daily our cells accumulate DNA lesions that have the potential to impede fundamental cellular functions, including transcription and genome replication. If these lesions are not correctly repaired, they may also lead to mutations or aberrations in the genome, which are associated with human diseases, including cancer [

6]. These DNA lesions are the result of several exogenous causes, including ultraviolet (UV) and ionizing radiation, various chemical agents, as well as endogenous factors, such as DNA base mismatch, oxidation, hydrolysis, and alkylation of DNA [

7]. Cells have created a complex system of pathways known as the

DNA damage response (DDR

) network to detect and repair damage in response to these alterations in the chemical structure of DNA, safeguarding the integrity of the genome [

8,

9]. DDR is a well-organized system including sensors, mediators, transducers, and effectors that activate different pathways, such as cell cycle regulation and DNA repair. Apoptosis or mutagenesis is triggered if the amount of unrepaired DNA lesions exceeds a predetermined threshold [

10,

11]

. Specifically, the detection of a DNA lesion activates DDR. A signal transduction cascade is triggered, which leads to the induction of complex mechanisms for genome protection (apoptosis, cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair pathways,

transcription and chromatin remodeling). Deregulated DDR, on the contrary, may cause mutagenesis and genomic instability, including

point mutations, chromosomal translocations and gain or loss of chromosomal segments or entire chromosomes [

8]

. As DDR controls the cellular choice of whether to eliminate DNA damage or initiate apoptosis, it plays a role in the onset and progression of multiple diseases, as well as their clinical response to therapy [

12,

13,

14].

Importantly, recent studies have shown that alterations in the tumor-related DDR network affect both immune surveillance and immune responses, potentially augmenting the efficacy of immunotherapy [

15,

16]. There are several ways that a defective DDR network may boost the antitumor immune response. For example, an increase in the burden of tumor mutations (TMB) and an elevated level of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-presented neoantigens, which T lymphocytes can identify, are the results of a deficiency in DNA damage repair [

17]. In addition, DDR failure may result in the induction of cytosolic DNA. This DNA attaches to cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate synthase (cGAS) and then triggers the innate immune response through the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway [

18]. Furthermore, inhibition of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase promotes an innate immune response mediated by interferons in a way that is dependent on the proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase SRC and the TANK Binding Kinase 1 (TBK1) [

19].

Particularly, research on HNSCC has demonstrated that the DNA damage caused by genotoxic drugs and the associated cellular reactions enhances tumor immunogenicity and the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy [

20]

. Collectively, these findings lend credence to the argument that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be more effective against cancers with underlying DNA repair abnormalities and that targeting DDR may be an advantageous approach to increase the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibition [

13]

.

In a similar vein, oxidative stress results from an imbalance between antioxidant defense mechanisms and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. This imbalance can activate proto-oncogenes and inactivate cancer suppressor genes [

21]

. Oxidative stress has the potential to cause oxidative damage to fundamental cellular constituents (proteins, lipids, and DNA), thus advancing the disease’s pathophysiology and progression. Patients with HNSCC in particular have been discovered to have a compromised antioxidant system and elevated oxidative stress [

13,

22,

23]

. Interestingly, oxidative stress influences the phenotype and function of myeloid dendritic cells (DCs) within the TME, and affects the functional behavior of tumor T regulatory cells (Tregs), which in turn diminish the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [

24]

. However, it is still unknown how precisely oxidative stress contributes to the development, course, and response to treatment of HNSCC.

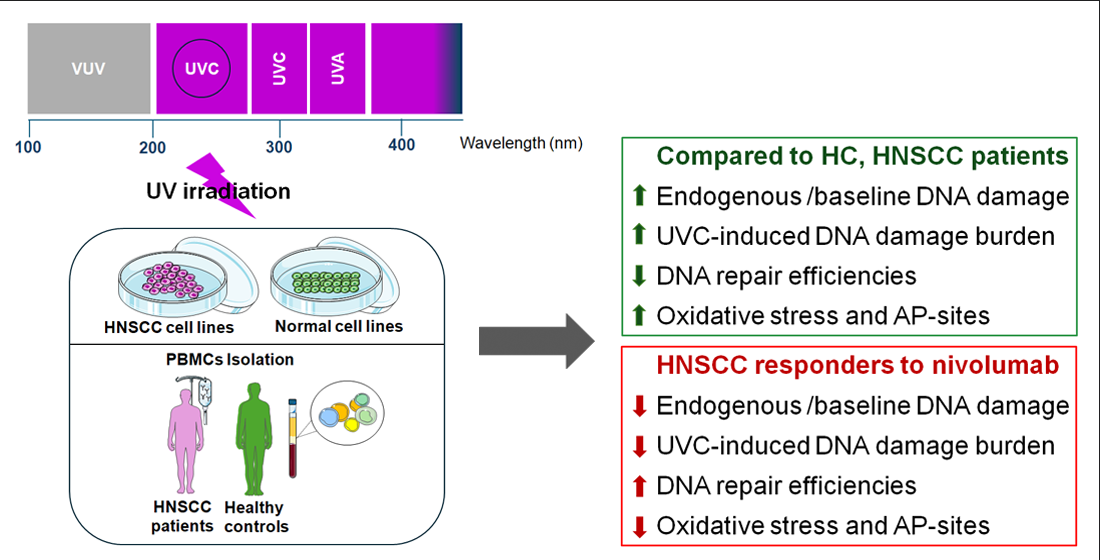

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that oxidative stress and DNA repair efficiencies measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HNSCC patients correlate with the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. We follow a systematic approach to evaluate several DDR parameters in normal and HNSCC cell lines, as well as in PBMCs from healthy controls and HNSCC patients with different response rates to nivolumab therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

A total of 49 recurrent/metastatic (R/M) HNSCC patients (

Table 1; 9 females/40 males; median age 65 years; range 48-93) who participated in a phase II nivolumab trial (NCT03652142; protocol #ΒΠΠΚ, ΕΒΔ 257/18-05-2020) were included in the study. PBMCs were isolated from freshly drawn peripheral blood and purified as previously described [

13]. PBMCs were resuspended in freezing medium (90% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 10% dimethyl sulfoxide) and stored at −80°C until further analysis. PBMCs were obtained from HNSCC patients at baseline. Patients were categorized based on their outcome into the following groups: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD). CR, PR, SD and PD were defined based on revised RECIST criteria version 1.1 [

25]. Fifteen (

n=15) healthy individuals (HC; 6 females/9 males; median age 57.9 years; range, 30–80) were also analyzed (protocol #BΠΠΚ, ΕΒΔ 509/10-07-2023). All participants gave informed consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which had been previously approved by the Ethics Committee of Attikon Hospital, Athens, Greece.

2.2. Cell Lines

Human 1BR-3h-T cells (immortalized normal skin fibroblasts; kindly provided by Dr. Fousteri M., “Alexander Fleming” Biomedical Sciences Research Center, Athens, Greece) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Human RPMI-1788 (immortalized human B lymphocyte cells) were obtained from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, USA) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Human UM-SCC-11A cells (laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma cells; kindly provided by Thomas Carey University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) were maintained in DMEM, supplemented with 1% non-essential amino acids, 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Human CAL-33 cells [tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells acquired from the Leibniz Institute DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany (ACC 447)], were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Human BB49 (floor-of-mouth squamous cell carcinoma cells; kindly provided by Prof. Scorilas A., Department of Biology NKUA, Athens, Greece), were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 2mM glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

2.3. UVC-Treatment

For UV irradiation of HNSCC and normal cell lines, the medium was removed, and cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then irradiated with a total dose of 100 J/m2 with a Philips 6W germicidal lamp (UVC), which emits primarily in the UVC ranges. Accordingly, freshly isolated PBMCs were resuspended in PBS and irradiated with UVC with a total dose of 5 J/m2. All cells were centrifuged, passed into a complete cell culture medium and incubated in a humidified CO2 incubator for the appropriate time points. Cells were then collected in freezing medium and stored at -80°C until further processing. Each sample was afterward analyzed to evaluate UVC-induced DNA damage burden levels.

2.4. Viability Assay

The analysis of drug-induced cytotoxicity and cell proliferation was performed by the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay [

26]. Briefly, cell lines were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 20,000 cells per well, irradiated with UVC with a total dose of 100 J/m

2 and incubated in a complete cell culture medium for 6h. At each well, 1ml of 10% ice-cold Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was carefully added and the plates were incubated for 30min on ice or overnight at 4°C. After washing the plates and drying them, 500μl of 0.4% SRB (Sigma-Aldrich) solution was added. The unbound SRB stain was washed with 1% acetic acid and the stained cells were dissolved with 500μl of 10mM Tris Base (pH 10.5). Absorbance was quantified using a microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) and cell viability was estimated compared to non-irradiated negative control.

2.5. Alkaline Single-Cell Gel Electrophoresis (Comet Assay)

The alkaline single-cell gel electrophoresis assay was performed as previously described [

27]. Untreated or UVC-treated cells were suspended in low melting agarose (1% in PBS) at 37°C and spread onto fully frosted microscope slides pre-coated with a thin layer of 1% normal melting agarose. The cell suspension was immediately covered with a coverglass, and the slides were kept at 4°C for 20-30min to allow solidification of the agarose. After removing the coverglass, cells were exposed to lysis buffer at 4°C for 1h. Then, the slides were placed in a horizontal gel electrophoresis chamber, filled with cold electrophoresis buffer and slides were kept at 4°C for 30min to allow the DNA to unwind. Electrophoresis was performed for 30min (25V, 255mA). After electrophoresis, the slides were washed for 10min with neutralization buffer and 10min with ice-cold distilled H

2O and left to dry overnight. Gels were stained with SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Thermo Fischer Scientific; # S11494) and analyzed with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiophot). Olive Tail Moments [OTM = (Tail Mean-Head Mean) x (% of DNA)/100] of at least 100 cells/treatment condition were evaluated. Comet parameters were analyzed by the ImageJ Analysis/Open Comet software. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.6. Oxidative Stress and Apurinic/Apyrimidinic (Abasic; AP) Sites

Oxidative stress was quantified by a luminescence-based assay (GSH/GSSG-Glo Assay, #V6612, Promega, UK), measuring total glutathione (GSH+GSSG), oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and the GSH/GSSG ratio, according to the manufacturer’s experimental protocol as described previously [

28]. Apurinic/apyrimidinic sites were measured by the OxiSelect Oxidative DNA Damage Quantitation Kit (Cell Biolabs; #STA-324, according to the manufacturer’s experimental protocol, as described previously [

28].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

To compare continuous variables among the groups analyzed, we used unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, when normal distribution did not apply. Mean values ± standard deviations were used to present the results. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

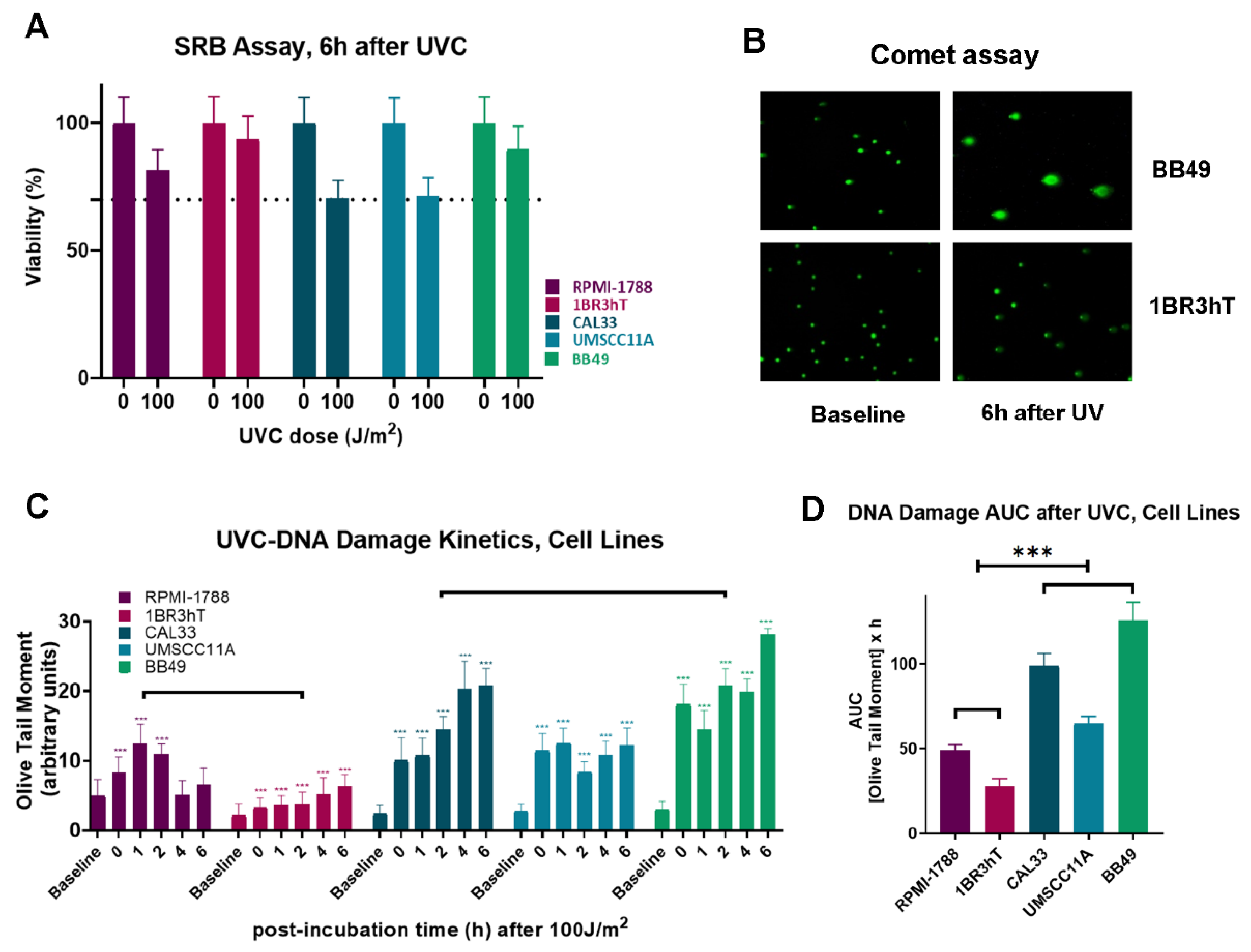

3.1. DNA Damage Repair and Oxidative Stress in HNSCC Cell Lines

The efficiency of DNA damage repair and the oxidative stress were analyzed in three HNSCC (UM-SCC-11A, CAL33, BB49) and two normal cell lines (RPMI-1788, 1BR3hT). First, UVC-induced cytotoxicity and cell proliferation were determined using SRB assay. We found that 6h after UVC irradiation with a total dose of 100 J/m

2 all cell types showed greater than 70% viability (

Figure 1A). Next, cells were irradiated with 100 J/m

2 UVC, incubated for several time points (0, 1, 2, 4 and 6h) in the appropriate culture media and DNA damage was measured using alkaline comet assay, which measures single-strand breaks (SSBs) and/or double-strand breaks (DSBs) (

Figure 1B). Similar results were found for the cell lines of each group. Significant differences in the DNA repair efficiencies were found between malignant and normal cell lines. Indeed, all HNSCC cell lines showed reduced DNA repair efficiencies, compared to normal cells (

Figure 1C), leading to increased UVC-induced DNA damage burden in malignant cells, expressed as the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for DNA damage during the experiment (0-6h;

P < 0.001;

Figure 1D).

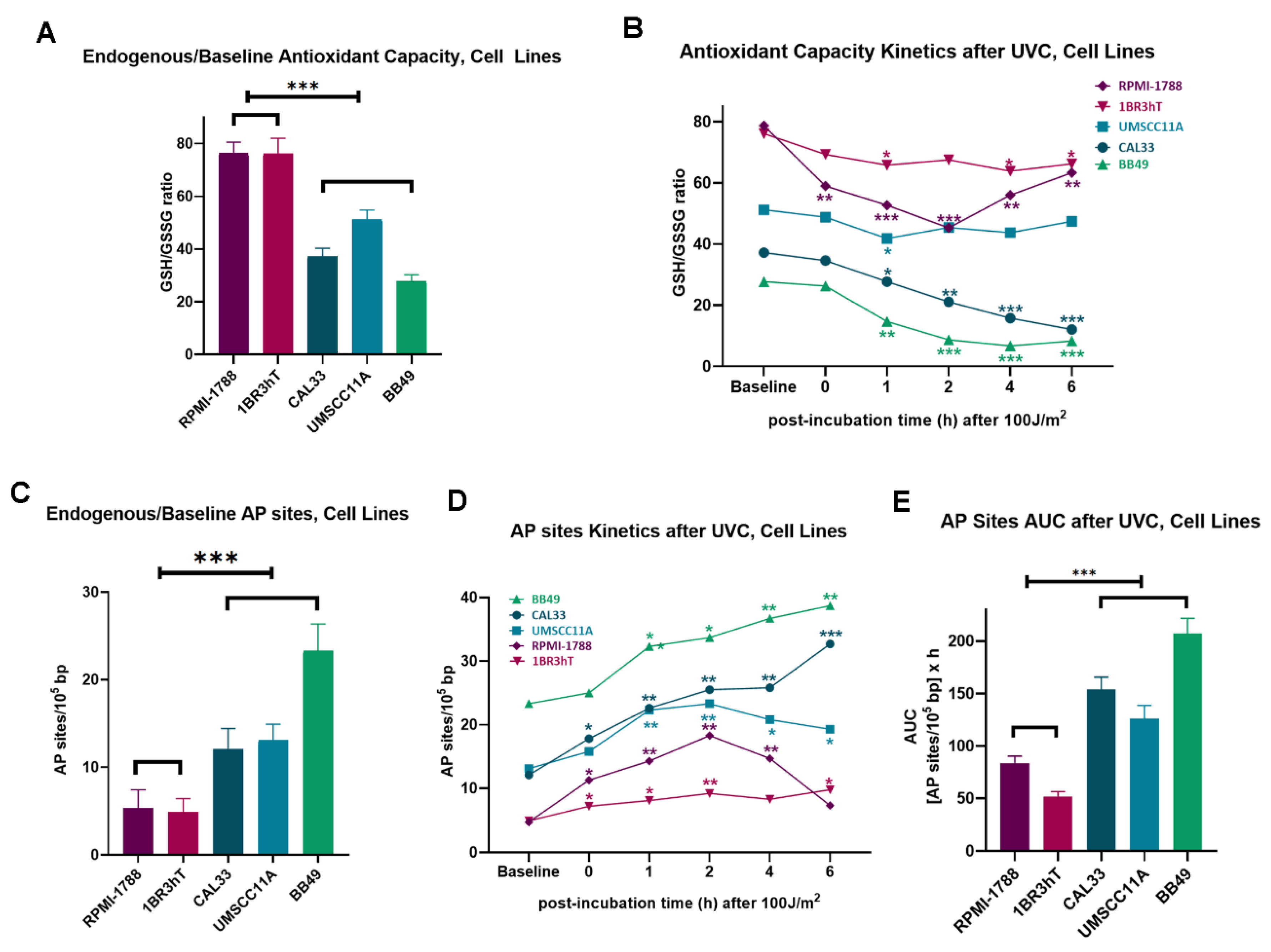

Next, we evaluated critical intracellular factors, namely, oxidative stress and apurinic/apyrimidinic sites that are implicated in the onset and progression of cancer, as well as in cancer therapy. All HNSCC cell lines showed significantly higher levels of endogenous/baseline and UVC-induced oxidative stress than normal cells, as indicated by the reduced GSH/GSSG ratio in the malignant cells (

P < 0.05;

Figure 2A,B). In line with these data, higher levels of both endogenous/baseline and UVC-induced apurinic/apyrimidinic sites (all

P < 0.05;

Figure 2C,D) were observed in HNSCC cell lines, compared to normal cells, resulting in significantly increased accumulation of UVC-induced AP-sites in malignant cells (

P < 0.001;

Figure 2E).

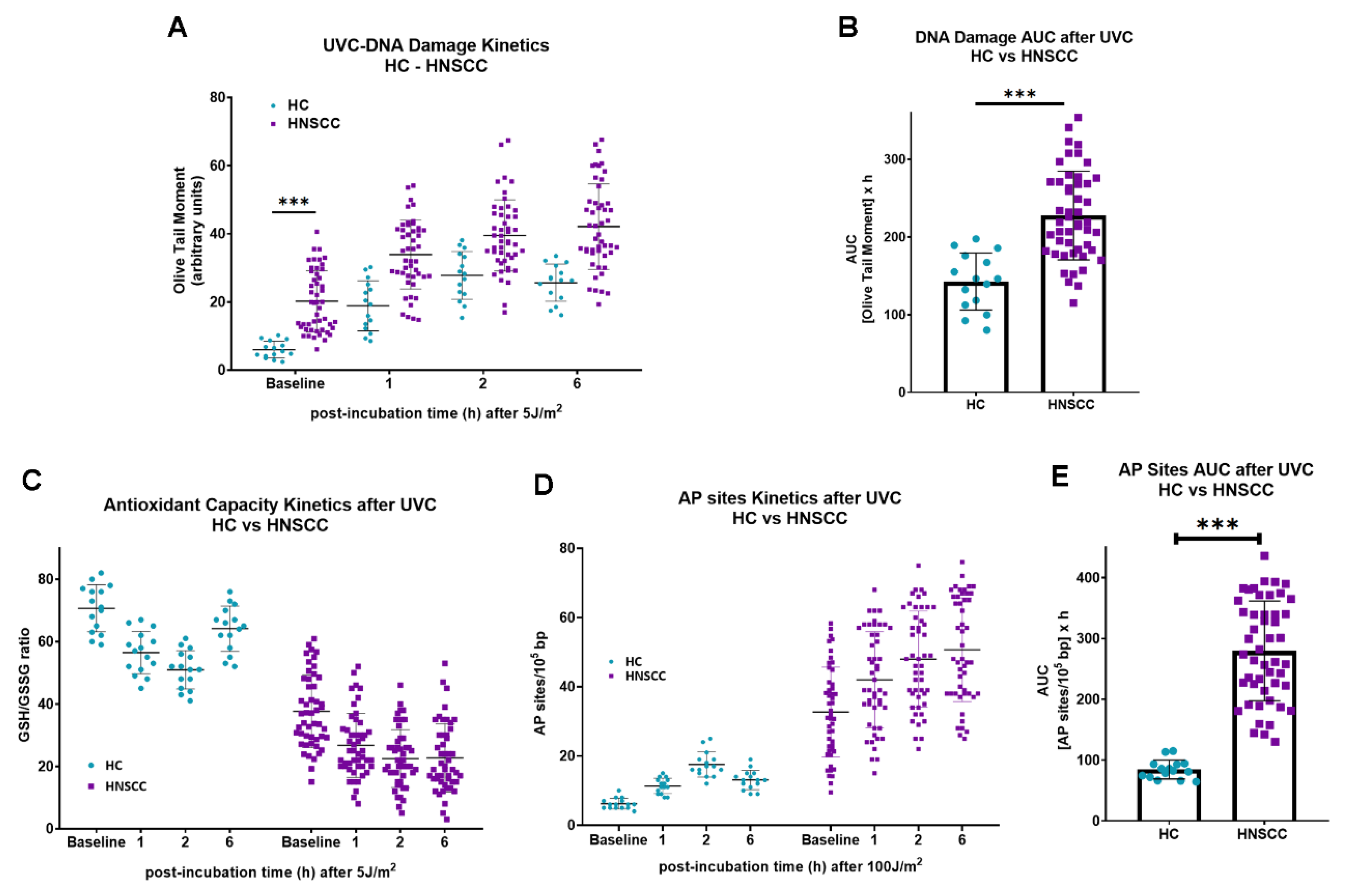

3.2. DNA Damage Repair and Oxidative Stress in PBMCs Derived from HNSCC Patients

To determine whether the results obtained in cell lines can be extrapolated to samples derived from HNSCC patients, changes in the endogenous/baseline DNA damage, the DNA damage repair efficiencies, the oxidative stress and the apurinic/apyrimidinic lesions were also evaluated in PBMCs from 15 healthy controls and 49 recurrent/metastatic HNSCC patients at baseline. Firstly, the endogenous/baseline DNA damage was measured using an alkaline comet assay. We found that the levels of endogenous/baseline DNA damage were significantly higher in PBMCs from HNSCC patients than those from healthy controls (

P < 0.001;

Figure 3A). In line with the cell lines results, following irradiation of PBMCs with 5 J/m

2, HNSCC patients showed decreased DNA repair capacity, compared to those from healthy controls (

P < 0.001;

Figure 3A), resulting in augmented accumulation of UVC-induced DNA damage in PBMCs from malignant patients (

P < 0.001;

Figure 3B). In addition, PBMCs from HNSCC patients exhibited higher endogenous/baseline and UVC-induced oxidative stress and AP-sites than PBMCs from HC (

Figure 3C,D), resulting in significantly increased accumulation of UVC-induced AP-sites in samples from cancer patients (

P < 0.001;

Figure 3E).

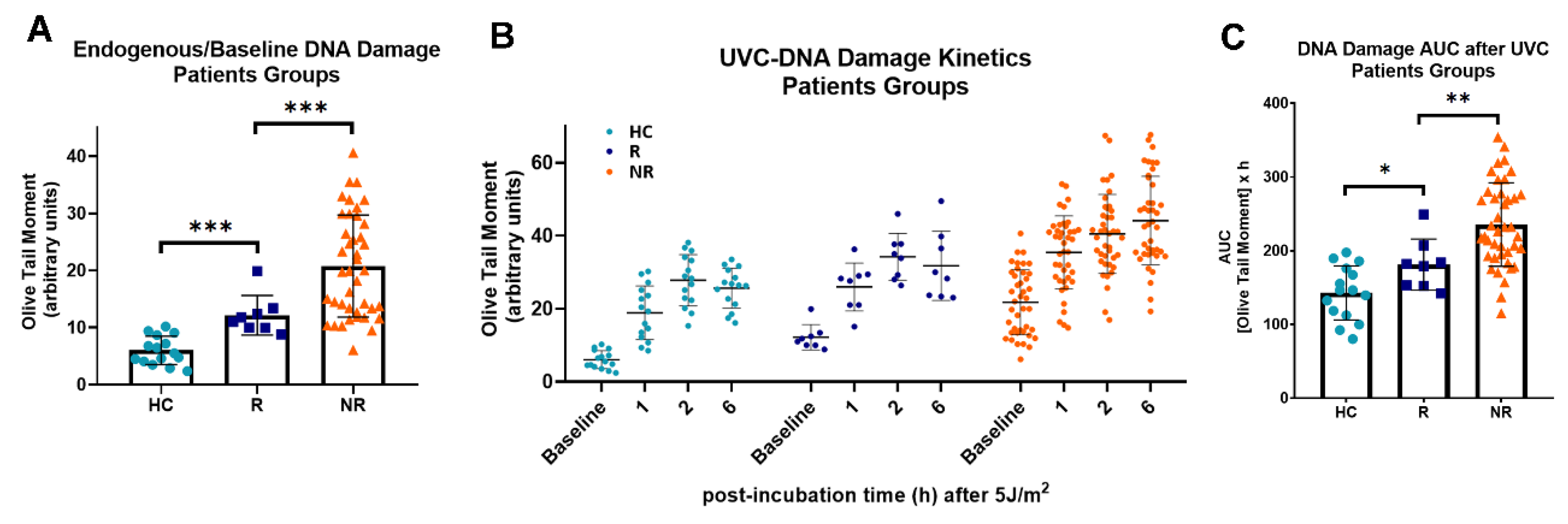

Next, following the stratification of HNSCC patients into responders (

n=8; CR and PR) and non-responders (

n=41; SD and PD), we tested the hypothesis that DNA damage-related parameters are involved in the response to nivolumab therapy. We found that the endogenous/baseline DNA damage was in the order HC < responders < non-responders, suggesting that non-responders HNSCC patients are characterized by higher levels of DNA damage, compared with responders (all

P < 0.001;

Figure 4A). Moreover, the DNA repair capacity of PBMCs was analyzed following irradiation with 5 J/m

2 UVC. Decreased DNA repair capacity was found in PBMCs derived from non-responders than PBMCs from responders (

Figure 4B), resulting in higher UVC-induced DNA damage burden in samples from non-responders’ patients (

P < 0.05;

Figure 4C).

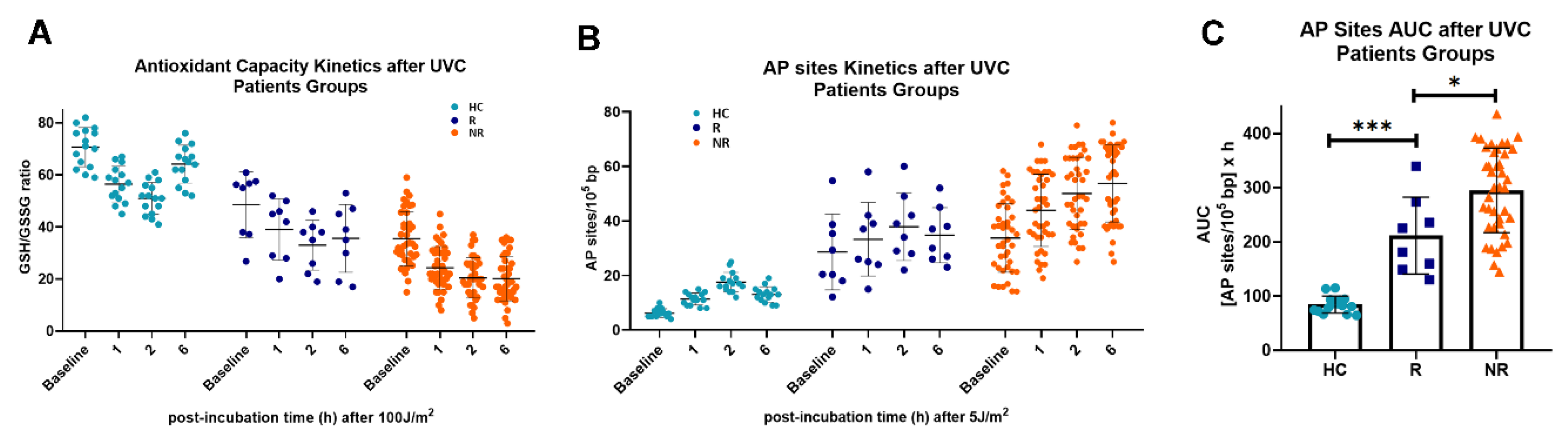

In addition, we observed that PBMCs derived from non-responders to nivolumab therapy exhibited increased endogenous/baseline and UVC-induced oxidative stress and AP-sites (

Figure 5A,B), leading to increased accumulation of UVC-induced apurinic/apyrimidinic lesions in these patients (

P < 0.05;

Figure 5C).

4. Discussion

Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors is a rapidly evolving approach and the standard of care for recurrent and metastatic head and neck cancers [

29,

30]. Although the approval of pembrolizumab and nivolumab represents a significant advancement in the oncology field, only a small proportion of patients derive benefit from blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, raising the need for predictive biomarkers and the study of combination strategies to augment therapeutic efficacy [

30]. Interestingly, recent data have shown that the DDR network interacts strongly with the immune system, regulating host immunological responses and potentially offering a novel tool for improving immunotherapy efficacy [

16]. Hence, herein we studied DDR-related parameters and oxidative stress in HNSCC patients with different responses to immune checkpoint blockage.

Endogenous/baseline DNA damage represents a major threat to cell fate, as it can cause mutagenesis, and genomic instability, and lead to cellular apoptosis [

31]. In the present study, higher levels of endogenous/baseline DNA damage were found in HNSCC patients than in healthy controls, with non-responders to nivolumab therapy showing the highest levels. To better understand the origin of this phenomenon, we first examined the DNA repair capacity of PBMCs from HNSCC patients. We found that these patients showed defective DNA repair capacity, compared with healthy controls, with non-responders showing the lowest DNA repair capacity. These results are consistent with earlier data showing that critical DNA repair mechanisms, such as nucleotide excision repair (NER), double-strand breaks repair (DSB/R), base-excision repair (BER) and mismatch repair (MMR) are defective in HNSCC cells. Indeed, previous reports have shown decreased NER capacity in cancer patients compared with healthy controls, with responders to chemotherapy showing lower NER efficiency than non-responders [

13,

32,

33,

34,

35]. To explain the lower NER capacity of HNSCC patients, other studies have shown that important NER-associated genes, such as ERCC1, ERCC2/ XPD, XPA, and XPC were downregulated in these patients, as compared to healthy controls [

36]. Another research pointed out that polymorphisms in the NER genes ERCC1, ERCC2/XPD, XPA and XPC are linked to the development and course of HNSCC, as well as the response to treatment [

37]. Furthermore, previous studies have also found that the DSB/R mechanism is also deregulated in HNSCC patients. Shammas and colleagues [

38] reported that constitutively activated DSB repair pathway may promote the development and spread of a tumor and the emergence of a drug-resistant phenotype. In line with these data, we previously showed that HNSCC patients had a higher DSB repair capacity than healthy controls and that important genes linked to DSB repair (MRE11A, RAD50, RAD51, XRCC2) were overexpressed in HNSCC patients [

13]. Moreover, according to earlier investigations, DSB repair genes polymorphisms (RAD51, MRE11A, XRCC2, XRCC3) are involved in an increased risk of developing HNSCC [

39,

40]. Furthermore, other studies have shown that the expression of some BER-associated genes (APEX1, XRCC1) was lower in HNSCC patients than in healthy controls, and a number of MMR-related genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH3) were overexpressed. Previous studies also reported that polymorphisms in MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH3) and BER genes (APEX1, XRCC1) may contribute to the progression of HNSCC [

41,

42].

In addition, herein we assessed the induction of oxidative stress and apurinic/apyrimidinic lesions, in order to determine the cause of the elevated formation of DNA damage in HNSCC patients. In line with our previous study [

13], we observed that in comparison to healthy controls, HNSCC patients had higher levels of both these factors. It is generally accepted that oxidative stress plays a crucial role in the onset and progression of HNSCC. Indeed, prior research has demonstrated a strong association between HNSCC and oxidative stress, as tobacco and alcohol—both known to elevate ROS production—are recognized as key etiological factors for this cancer [

13,

43]. Intracellular ROS cause oxidative DNA damage, which leads to single- and double-strand breaks, apurinic/apyrimidinic lesions, and changes of DNA bases, with many of these lesions being hazardous and/or mutagenic [

44]. For example, elevated levels of mutagenic 8-hydroxyguanine lesions are found in cancer and aging cells [

45]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that microsatellite instability, which is found most often in colorectal, endometrial and gastric cancer, may also be caused by H

2O

2-induced oxidative DNA damage [

46]. Importantly, herein we found significant differences in the oxidative stress status between HNSCC patients with different responses to nivolumab treatment, with responders showing significantly lower oxidative stress compared with non-responders. These results are in line with our previous study, which showed that lower oxidative stress correlates with longer progression free survival (PFS) of patients with HNSCC after platinum-based therapy [

13]. Other studies have also reported that HNSCC patients with lower oxidative stress have a reduced risk of local and regional tumor recurrence after concomitant chemoradiotherapy, suggesting that tumors with higher oxidative stress exhibit more aggressive behavior [

47]. Notably, the cell line experiments presented above showed corresponding results on oxidative stress and DNA damage repair-associated signals, confirming the wide application of our findings.

Together, significant differences in the oxidative stress status and the DNA damage repair capacity were observed between responders and non-responders to nivolumab therapy. These results show a strong correlation between deregulated DDR-related parameters in PBMCs from HNSCC patients at baseline and the response to subsequent immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Indeed, extensive observations suggest that the therapeutic effect of the ICIs is directly impacted by the tumors’ altered DDR pathway, which influences immunogenicity and immune cell infiltration [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Currently, the tumor mutational burden (TMB) [

52,

53], microsatellite instability (MSI) or mismatch repair-deficiency (dMMR) [

54], and PD-L1 expression levels [

55] are the main indicators used to predict the impact of ICI therapy on cancer patients. Prior research on solid tumors and hematological malignancies has demonstrated that blood DDR parameters monitoring may help predict patient’s prognosis and forecast the response to chemotherapy treatment [

13,

23,

32,

34,

35,

37,

41,

47,

51]. Therefore, the results presented in the present study open the prospect of evaluating the effectiveness of immune checkpoint blockade by measuring oxidative stress and DNA damage repair status in a readily accessible tissue such as PBMCs.

5. Conclusions

Two important mechanisms for the survival of living organisms are the immune system and the DDR network. Particularly important is the immune system’s activation during the development and progression of cancer, as well as its possible role in the effectiveness of therapeutic outcome. Also, DDR plays a role in the development and progression of a number of diseases as well as in the response to chemotherapy. According to recent data, these two systems work together to support the coordinated operation of multicellular organisms. Thus, in this study we examined the connection between the anticancer activity of the ICI-based treatment and the DDR-related parameters measured in PBMCs from HNSCC patients. Compared to non-responders, we observed that nivolumab therapy responders had lower endogenous/baseline DNA damage, higher DNA repair capacities, less oxidative stress and decreased apurinic/apyrimidinic lesions. These results, when properly validated, can lead to the development of new predictive biomarkers to immunotherapies, and the design of novel combination regimens including DDR-targeted drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Christina Papanikolaou, Amanda Psyrri and Vassilis Souliotis; Data curation, Christina Papanikolaou and Vassilis Souliotis; Formal analysis, Christina Papanikolaou and Vassilis Souliotis; Funding acquisition, Niki Gavrielatou; Investigation, Christina Papanikolaou, Panagiota Economopoulou, Niki Gavrielatou, Dimitra Mavroeidi and Vassilis Souliotis; Project administration, Vassilis Souliotis; Resources, Vassilis Souliotis; Supervision, Amanda Psyrri and Vassilis Souliotis; Validation, Christina Papanikolaou, Panagiota Economopoulou, Amanda Psyrri and Vassilis Souliotis; Visualization, Christina Papanikolaou, Dimitra Mavroeidi and Vassilis Souliotis; Writing – original draft, Christina Papanikolaou and Vassilis Souliotis; Writing – review & editing, Christina Papanikolaou, Panagiota Economopoulou, Niki Gavrielatou, Dimitra Mavroeidi, Amanda Psyrri and Vassilis Souliotis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hellenic Society of Medical Oncology (HeSMO) (9591/19-6-2024 research grant).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Attikon Hospital (protocol #ΒΠΠΚ, ΕΒΔ 257/18-05-2020 and #BΠΠΚ, ΕΒΔ 509/10-07-2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available by specific request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Fousteri and Andreas Scorilas for providing cell lines.

Conflicts of Interest

Amanda Psyrri has received honoraria and research funding from BMS, MSD, Roche, Pfizer, Merck Serono, AstraZeneca and Ipsen. She has also received research support from KURA Oncology.

References

- Du, E.; Mazul, A.L.; Farquhar, D.; Brennan, P.; Anantharaman, D.; Abedi-Ardekani, B.; Weissler, M.C.; Hayes, D.N.; Olshan, A.F.; Zevallos, J.P. Long-term Survival in Head and Neck Cancer: Impact of Site, Stage, Smoking, and Human Papillomavirus Status. The Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 2506–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economopoulou, P.; De Bree, R.; Kotsantis, I.; Psyrri, A. Diagnostic Tumor Markers in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) in the Clinical Setting. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.S.; Pajak, T.F.; Forastiere, A.A.; Jacobs, J.; Campbell, B.H.; Saxman, S.B.; Kish, J.A.; Kim, H.E.; Cmelak, A.J.; Rotman, M.; et al. Postoperative Concurrent Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy for High-Risk Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrielatou, N.; Vathiotis, I.; Economopoulou, P.; Psyrri, A. The Role of B Cells in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.P.; Bartek, J. The DNA-Damage Response in Human Biology and Disease. Nature 2009, 461, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakem, R. DNA-Damage Repair; the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. EMBO J 2008, 27, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Jia, K.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; He, Y.; Zhou, C. Alterations of DNA Damage Repair in Cancer: From Mechanisms to Applications. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 1685–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malamos, P.; Papanikolaou, C.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Terpos, E.; Souliotis, V.L. The Interplay between the DNA Damage Response (DDR) Network and the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling Pathway in Multiple Myeloma. IJMS 2024, 25, 6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pateras, I.S.; Havaki, S.; Nikitopoulou, X.; Vougas, K.; Townsend, P.A.; Panayiotidis, M.I.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Gorgoulis, V.G. The DNA Damage Response and Immune Signaling Alliance: Is It Good or Bad? Nature Decides When and Where. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2015, 154, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, C.; Rapti, V.; Stellas, D.; Stefanou, D.; Syrigos, K.; Pavlakis, G.; Souliotis, V. Delineating the SARS-CoV-2 Induced Interplay between the Host Immune System and the DNA Damage Response Network. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeggo, P.A.; Pearl, L.H.; Carr, A.M. DNA Repair, Genome Stability and Cancer: A Historical Perspective. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psyrri, A.; Gkotzamanidou, M.; Papaxoinis, G.; Krikoni, L.; Economopoulou, P.; Kotsantis, I.; Anastasiou, M.; Souliotis, V.L. The DNA Damage Response Network in the Treatment of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanou, D.T.; Kouvela, M.; Stellas, D.; Voutetakis, K.; Papadodima, O.; Syrigos, K.; Souliotis, V.L. Oxidative Stress and Deregulated DNA Damage Response Network in Lung Cancer Patients. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.C.Y.; Kok, J.S.T.; Teh, B.T.; Lim, K.S. Interplay between the DNA Damage Response and Immunotherapy Response in Cancer. IJMS 2022, 23, 13356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, K.W.; Goldberg, M.S.; Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; D’Andrea, A.D. DNA Damage and Repair Biomarkers of Immunotherapy Response. Cancer Discovery 2017, 7, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarchoan, M.; Johnson, B.A.; Lutz, E.R.; Laheru, D.A.; Jaffee, E.M. Targeting Neoantigens to Augment Antitumour Immunity. Nat Rev Cancer 2017, 17, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motwani, M.; Pesiridis, S.; Fitzgerald, K.A. DNA Sensing by the cGAS–STING Pathway in Health and Disease. Nat Rev Genet 2019, 20, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Green, M.D.; Lang, X.; Lazarus, J.; Parsels, J.D.; Wei, S.; Parsels, L.A.; Shi, J.; Ramnath, N.; Wahl, D.R.; et al. Inhibition of ATM Increases Interferon Signaling and Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer to Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Research 2019, 79, 3940–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenclares, P.; Rullan, A.; Tam, K.; Dunn, L.A.; St. John, M.; Harrington, K.J. Introducing Checkpoint Inhibitors Into the Curative Setting of Head and Neck Cancers: Lessons Learned, Future Considerations. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2022, 511–526. [CrossRef]

- Arfin, S.; Jha, N.K.; Jha, S.K.; Kesari, K.K.; Ruokolainen, J.; Roychoudhury, S.; Rathi, B.; Kumar, D. Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cell Metabolism. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhari, S.K.; Chaudhary, M.; Gadbail, A.R.; Sharma, A.; Tekade, S. Oxidative and Antioxidative Mechanisms in Oral Cancer and Precancer: A Review. Oral Oncology 2014, 50, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavroeidi, D.; Georganta, A.; Stefanou, D.T.; Papanikolaou, C.; Syrigos, K.N.; Souliotis, V.L. DNA Damage Response Network and Intracellular Redox Status in the Clinical Outcome of Patients with Lung Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, T.; Wang, W.; Crespo, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Wei, S.; Zhao, L.; Vatan, L.; Shao, I.; Szeliga, W.; et al. Oxidative Stress Controls Regulatory T Cell Apoptosis and Suppressor Activity and PD-L1-Blockade Resistance in Tumor. Nat Immunol 2017, 18, 1332–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours: Revised RECIST Guideline (Version 1.1). European Journal of Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vichai, V.; Kirtikara, K. Sulforhodamine B Colorimetric Assay for Cytotoxicity Screening. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souliotis, V.L.; Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Pappa, M.; Argyriou, A.; Sfikakis, P.P. DNA Damage Accumulation, Defective Chromatin Organization and Deficient DNA Repair Capacity in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clinical Immunology 2019, 203, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Pappa, M.; Ntouros, P.A.; Nezos, A.; Mavragani, C.P.; Souliotis, V.L.; Sfikakis, P.P. Association Between DNA Damage Response, Fibrosis and Type I Interferon Signature in Systemic Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 582401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, A.; Prasad, V. Estimation of the Percentage of US Patients With Cancer Who Are Eligible for and Respond to Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy Drugs. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e192535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R.W.; Borson, S.; Tsagianni, A.; Zandberg, D.P. Immunotherapy in Recurrent/Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 705614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, I.; Kroemer, G. Spontaneous DNA Damage Propels Tumorigenicity. Cell Res 2017, 27, 720–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkotzamanidou, M.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Bamia, C.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Souliotis, V.L. Chromatin Structure, Transcriptional Activity and DNA Repair Efficiency Affect the Outcome of Chemotherapy in Multiple Myeloma. Br J Cancer 2014, 111, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souliotis, V.L.; Vougas, K.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Sfikakis, P.P. Defective DNA Repair and Chromatin Organization in Patients with Quiescent Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2016, 18, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanou, D.T.; Bamias, A.; Episkopou, H.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Likka, M.; Kalampokas, T.; Photiou, S.; Gavalas, N.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; et al. Aberrant DNA Damage Response Pathways May Predict the Outcome of Platinum Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkotzamanidou, M.; Terpos, E.; Bamia, C.; Munshi, N.C.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Souliotis, V.L. DNA Repair of Myeloma Plasma Cells Correlates with Clinical Outcome: The Effect of the Nonhomologous End-Joining Inhibitor SCR7. Blood 2016, 128, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylawerska, A.; Barczak, W.; Wegner, A.; Golusinski, W.; Suchorska, W.M. Association of DNA Repair Genes Polymorphisms and Mutations with Increased Risk of Head and Neck Cancer: A Review. Med Oncol 2017, 34, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schena, M.; Guarrera, S.; Buffoni, L.; Salvadori, A.; Voglino, F.; Allione, A.; Pecorari, G.; Ruffini, E.; Garzino-Demo, P.; Bustreo, S.; et al. DNA Repair Gene Expression Level in Peripheral Blood and Tumour Tissue from Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer Patients. DNA Repair 2012, 11, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shammas, M.A.; Shmookler Reis, R.J.; Koley, H.; Batchu, R.B.; Li, C.; Munshi, N.C. Dysfunctional Homologous Recombination Mediates Genomic Instability and Progression in Myeloma. Blood 2009, 113, 2290–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, J.H.; Choudhury, B.; Kundu, S.; Ghosh, S.K. Combined Effect of Tobacco and DNA Repair Genes Polymorphisms of XRCC1 and XRCC2 Influence High Risk of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Northeast Indian Population. Med Oncol 2014, 31, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliwinski, T.; Walczak, A.; Przybylowska, K.; Rusin, P.; Pietruszewska, W.; Zielinska-Blizniewska, H.; Olszewski, J.; Morawiec-Sztandera, A.; Jendrzejczyk, S.; Mlynarski, W.; et al. Polymorphisms of the XRCC3 C722T and the RAD51 G135C Genes and the Risk of Head and Neck Cancer in a Polish Population. Experimental and Molecular Pathology 2010, 89, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senghore, T.; Wang, W.-C.; Chien, H.-T.; Chen, Y.-X.; Young, C.-K.; Huang, S.-F.; Yeh, C.-C. Polymorphisms of Mismatch Repair Pathway Genes Predict Clinical Outcomes in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients Receiving Adjuvant Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy. Cancers 2019, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjabeen, I.; Ali, K.; Zhou, X.; Kayani, M.A. Deregulation of Base Excision Repair Gene Expression and Enhanced Proliferation in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 5971–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pandey, P.; Tewari, M.; Pandey, H.; Gambhir, I.; Shukla, H.S. Free Radicals Hasten Head and Neck Cancer Risk A Study of Total Oxidant, Total Antioxidant, DNA Damage, and Histological Grade. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 2016, 62, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, T.B. Biological Consequences of Oxidative Stress-Induced DNA Damage in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32, 3712–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, J.Y.; Park, J.; Jang, E.-S.; Chi, S.W. 8-Oxoguanine: From Oxidative Damage to Epigenetic and Epitranscriptional Modification. Exp Mol Med 2022, 54, 1626–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.L.; Loeb, L.A. Microsatellite Instability Induced by Hydrogen Peroxide in Escherichia Coli. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2000, 447, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dequanter, D.; Dok, R.; Nuyts, S. Basal Oxidative Stress Ratio of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas Correlates with Nodal Metastatic Spread in Patients under Therapy. OTT 2017, Volume 10, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, L. Targeting DNA Damage Repair for Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Applications. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 648687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Lin, A.; Cao, M.; Ding, W.; Mou, W.; Guo, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Luo, P. Activation of the DDR Pathway Leads to the Down-Regulation of the TGFβ Pathway and a Better Response to ICIs in Patients With Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 634741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Qin, K.; Lin, A.; Jiang, A.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Luo, P. The Role of DNA Damage Repair (DDR) System in Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI) Therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022, 41, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jiao, X.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Wei, X.; Liu, C.; Gong, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Peng, Z.; et al. Alterations in DNA Damage Response and Repair Genes as Potential Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Cancer Biology & Medicine 2022, 19, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, G.; Andrini, E.; Sisi, M.; Federico, A.D.; Ricciuti, B. Targeting DNA Damage Response and Repair Genes to Enhance Anticancer Immunotherapy: Rationale and Clinical Implication. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 1751–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, O.; Kee, D.; Markman, B.; Carlino, M.S.; Underhill, C.; Palmer, J.; Power, D.; Cebon, J.; Behren, A. Evaluation of TMB as a Predictive Biomarker in Patients with Solid Cancers Treated with Anti-PD-1/CTLA-4 Combination Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, J.C.; Lin, M.-T.; Le, D.T.; Eshleman, J.R. Microsatellite Instability as a Biomarker for PD-1 Blockade. Clinical Cancer Research 2016, 22, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshow, D.B.; Bhalla, S.; Beasley, M.B.; Sholl, L.M.; Kerr, K.M.; Gnjatic, S.; Wistuba, I.I.; Rimm, D.L.; Tsao, M.S.; Hirsch, F.R. PD-L1 as a Biomarker of Response to Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).