1. Introduction

Developments in energy storage technologies have brought significant transformations across various sectors and have become crucial for achieving a sustainable future. Moreover, the rising energy demand, increased use of renewable energy sources, and extensive adoption of electric vehicle (EV) technologies have contributed to the need for advanced energy storage systems. In particular, high fossil fuel consumption and the necessity to reduce environmental damage have driven efforts to develop renewable and sustainable energy sources such as high-quality batteries, wind turbines, fuel cells, and solar panels [

1,

2,

3].

LiBs are characterized by their compact size, lightweight design, high energy density and voltage, extended lifespan, absence of memory effect, efficient operation across a wide temperature range, and eco-friendly properties [

1,

4]. The growing use of EVs and consumer electronics has significantly increased the demand for LiBs, resulting in a substantial rise in the volume of EoL batteries requiring disposal [

5]. For example, China produced approximately 15 billion LiBs in 2014, and by 2024, its annual production capacity surpassed 1,170 GWh, representing around 76% of global output [

6]. This surge in LiB demand highlights their critical role in energy storage, EV charging infrastructure, and large-scale battery energy storage systems (BESS). Consequently, the projected increase in LiB production is expected to lead to a significant volume of EoL batteries.

Incorrect disposal of spent LiBs poses severe environmental problems, including soil and water contamination from leakage of heavy metals and hazardous compounds. Beyond environmental and economic benefits, exploiting the resource potential of battery scraps is essential for conserving natural resources and promoting the sustainable development of metals and related industries [

7,

8]. Additionally, EoL LiBs contain many components with high economic value, such as lithium (Li), cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), aluminum (Al), nickel (Ni), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and graphite [

9,

10].

LiBs are manufactured to meet specific application requirements, with the most variation occurring in the active cathode material. Several types of LiBs have been developed, including lithium cobalt oxide (LCO), nickel cobalt manganese oxide (NMC), nickel cobalt aluminum oxide (NCA), lithium manganese oxide (LMO), lithium iron phosphate (LFP), and lithium titanate oxide (LTO). Among these, NMC, LCO, LFP, and LMO batteries are the most widely used in commercial applications [

11]. NMC based LiBs generally comprise 5–20% Co, 5–7% lithium, 7-10% Cu, 10-15% Al, 4-5% Ni, 4-5% Mn, around 15% organic compounds, and approximately 7% plastic materials, indicating considerable potential for resource recovery [

12,

13]. Therefore, EoL LiBs are increasingly regarded as strategic secondary raw materials. Recycling these batteries enables the reclamation of critical metals, thus promoting sustainable resource management and contributing to the circular economy [

14,

15].

Driven by technological advancements, increasing market demand, and the growing volume of waste batteries, global battery recycling capacity has expanded from 9 GWh in 2019 to 50 GWh in 2024, and it is projected to exceed 230 GWh by 2030 [

16]. Recycling LiBs facilitates the recovery of critical metals, reducing dependency on mining, conserving natural resources, and supporting sustainable production models. It is estimated that recycling 500,000 tons of LiBs could recover approximately 45,000 tons of Cu, 15,000 tons of Al, 90,000 tons of Fe, 75,000 tons of Li, 60,000 tons of Co, and 35,000 tons of plastic materials [

17].

The recycling process of LiBs typically begins with a series of pre-treatment steps designed to prepare dismantled EoL battery packs for main recovery. These steps are crucial for purifying core components such as cathode and anode materials, enhancing the efficiency and safety of subsequent processing [

18]. The primary aim of pre-treatment is to achieve effective and safe separation of battery components, which is particularly important for hydrometallurgical recovery and direct recycling methods [

19]. Due to the structural complexity and hazardous nature of LiBs, pre-treatment is essential to mitigate safety risks and facilitate selective recovery of valuable materials. Standard pre-treatment operations include deep discharging to eliminate residual charge, mechanical size reduction, particle classification, physical component separation, thermal and chemical treatments, and cathode material isolation [

19,

20,

21]. This stage establishes foundational conditions to ensure high recovery yields and environmental compliance in advanced recycling technologies.

Size reduction is crucial for effective liberation of electrode materials and directly influences the efficiency of subsequent purification and enrichment stages. Shredders, hammer mills, and impact crushers are commonly used to break down battery cells into smaller fragments [

8,

14,

22,

23]. Further size reduction, if needed, can be performed by grinding into a fine powder. Screening systems then classify materials by particle size, separating fine fractions, rich in Li, Co, and graphite, from coarser fractions containing plastics, Fe, Cu, and Al. The fine fraction (undersize) constitutes valuable black mass (BM) suitable for hydrometallurgical or direct recovery, while the coarse fraction (oversize) can be further processed or recycled depending on composition.

The primary recycling technologies for LiBs include pyrometallurgical, hydrometallurgical, and direct recovery methods [

24,

25]. Pyrometallurgical processes operate at high temperatures, leading to high energy consumption and emission of harmful gases [

26]. Hydrometallurgical methods are favored for lower energy use, higher recovery efficiency, and reduced environmental impact [

27]. These acid leaching processes typically use sulfuric acid, with recent research focusing on replacing traditional reducing agents like hydrogen peroxide with environmentally friendly organic compounds such as glucose, tea waste, and grape seed extracts [

2]. Despite their benefits, these methods often involve complex chemical steps, high energy demands, or limited recovery yields.

Flotation separates materials based on their hydrophobic (water-repelling) and hydrophilic (water-attracting) properties by causing some particles to float while others sink. Originally used for ore beneficiation, flotation has recently been applied effectively for the direct recycling of EoL LiBs [

28]. This method is advantageous due to its low energy consumption, minimal chemical requirements, and ability to separate graphite from cathode metal oxides based on surface characteristics. The naturally hydrophobic graphite anode facilitates the separation of carbon-based materials in black mass [

29]. In flotation, graphite particles attach to bubbles and float, while mostly hydrophilic cathode materials like LCO and NMC sink to the bottom fraction [

30].

Despite growing interest in LiB recycling, studies focusing on the selective recovery of coarse metallic fractions such as Cu, Al, Fe, and Ni are scarce. Saneie et al. [

31] demonstrated effective separation of Cu and Al foils in the –4+1 mm size range from 18650-type spent LiBs using a two-stage flotation process involving initial plastic removal followed by Cu flotation. However, to our knowledge, no studies have addressed flotation-based separation of metal and plastic fractions from mixed NMC and LCO-type spent LiBs used in electric vehicles. Prior research on flotation-based recovery from waste printed circuit boards (PCBs) [

32,

33,

34] suggests that liberated plastic particles can be effectively separated from each other and metallic components in coarse fractions using froth flotation, indicating promising potential for LiB recycling.

Accordingly, this study focuses on the selective separation of plastics, Cu, Al, and structural metals from NMC and LCO-type LiBs through the application of various surface-active reagents. After initial black mass separation from the metallic fraction via sequential size reduction and sieving across four stages, the first flotation step targeted the selective removal of naturally hydrophobic plastics using a frother (Methyl Isobutyl Carbinol, MIBC). In the subsequent flotation stage, the effect of different collectors on Cu recovery was examined by promoting hydrophobic Cu particles to the froth phase, allowing hydrophilic Al and structural metal particles to remain in the pulp.

2. Experimental Studies

2.1. Materials

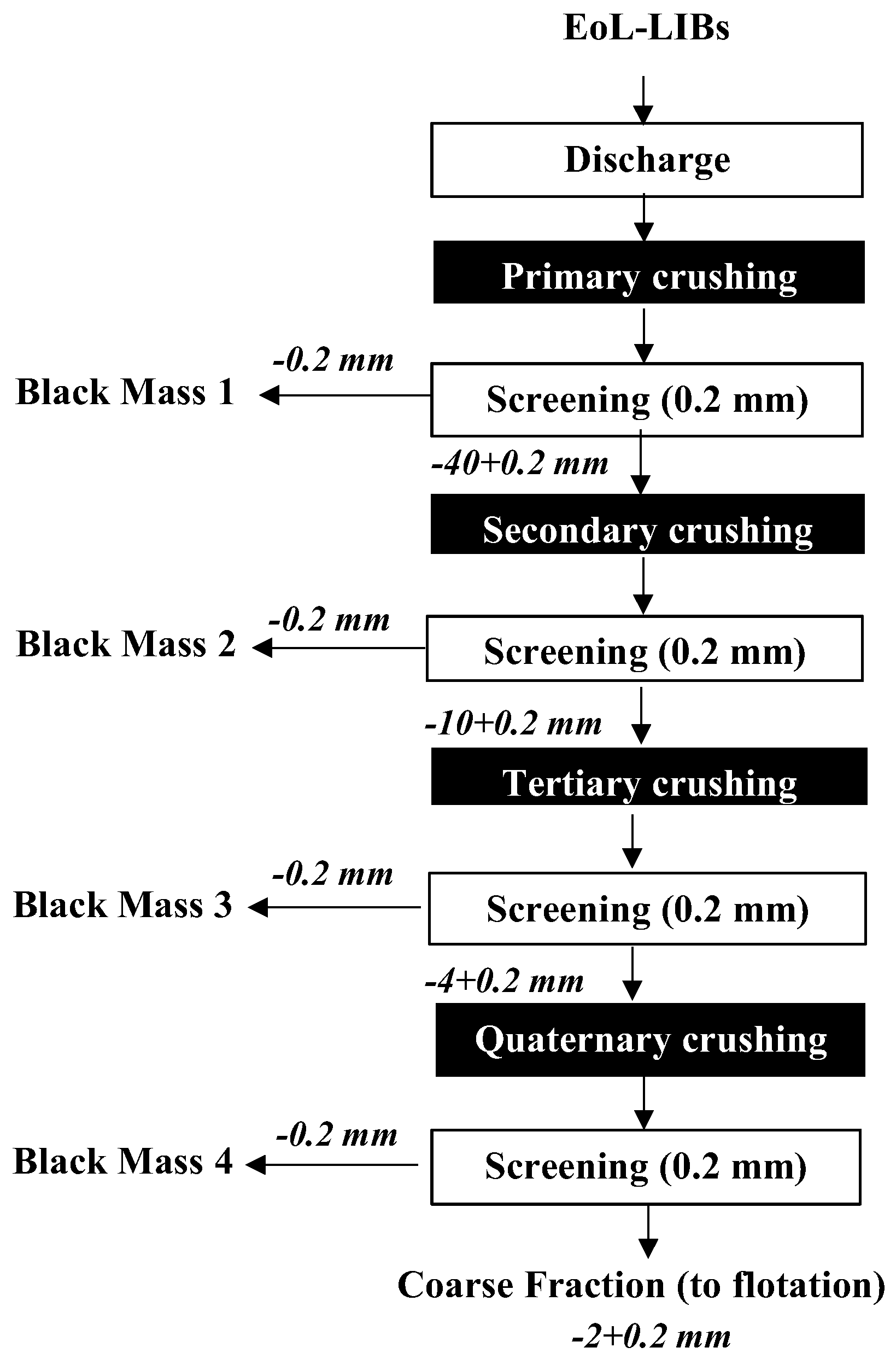

In this study, approximately 60 kg of mixed NMC and LCO-type EoL EV LiBs were supplied by Exitcom Co., located in Kocaeli, Türkiye. A multistage size reduction and classification system was applied, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Initially, the batteries were fully discharged for 48 hours using a 5% NaCl solution, and then air-dried. Following this, primary crushing was performed using a dual-shaft shredder at the recycling company to ensure safety. The crushed material (particles smaller than 40 mm) was then transferred to the Mineral Processing Engineering Department’s Prof. Dr. Güven Önal Pilot Plant at Istanbul Technical University for subsequent comminution processes.

The black mass 1 sample was initially separated using a 0.2 mm sieve, and the coarse fraction was subsequently reduced to particles smaller than 10 mm using a shredder. The crushed material was screened again with a 0.2 mm sieve, and the oversized fraction was fed into a four-blade cutting mill (RAM200 model, supplied by RANTEK Co.) to further scrape off the residual BM adhering to the current collectors. This cutting mill is designed to uniformly crush elastic, soft, medium-hard, fibrous, and heterogeneous materials. The shear forces reduce particle size while maintaining the flat surface shape of the material, which is advantageous for the flotation process. Particle size adjustment was achieved by using interchangeable sieves (6, 4, 2 mm, etc.) located in the lower compartment of the mill. The BM adhering to the surfaces of the current collectors was further collected using a 0.2 mm sieve and preserved for characterization and future studies.

The coarse fraction (–2+0.2 mm), constituting approximately 32% of the feed material, mainly consisted of Cu foils, Al foils, battery casings, plastics, and separators, and was used in characterization and flotation experiments. KAX (Potassium Amyl Xanthate) and Aerophine-3418A (Solvay Group), Aero-3739, Aerofloat-242, Aerofloat-211 (Syensqo), and MIBC (DOW Chemical Company) were employed as collectors and frother, respectively, in the flotation tests.

2.2. Characterization Studies

After quartering the comminuted material, a representative sample was collected, and sieve analysis was conducted using an electric shaker with standard sieves. The experimental data were interpreted based on product content and recovery. The compositions of major and trace elements were studied via BRUKER S8 TIGER model wavelength dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (WDXRF) at the Geochemistry Research Laboratory of the ITU Department of Geological Engineering. For this research, milled samples were homogenized with wax at a 1:5 (w/w) ratio and pelletized using a HERZOG model pelletizer to create homogenous discs suitable for XRF measurements. The Loss on Ignition (LOI) study was performed in two consecutive stages to ascertain the volatile content of the samples. Initially, 2–3 g of material was combusted at 500 °C for 2 hours to quantify organic matter and polymeric binders, including PVDF and separator residues. Thereafter, the identical samples were combusted at 1000 °C for an additional 2 hours to evaluate the total volatile content, encompassing carbonates and other thermally unstable constituents. This two-step LOI methodology facilitated a more thorough assessment of both organic and inorganic volatiles, especially in the black mass and flotation-derived products.

XRF is constrained in its ability to detect light elements (Z<11), including carbon, lithium, oxygen, and fluorine, owing to the low-energy characteristics of their X-rays and matrix absorption phenomena [

35]. Consequently, other methodologies were employed: lithium was measured via inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis using a PerkinElmer Avio 200 instrument, whereas carbon, oxygen, and fluorine were aggregated under the "others" group.

The recovery (

R) used in result interpretation was calculated by Eq. (1):

where

C is the weight of the concentrate,

c is the metal content of the concentrate,

F is the weight of the feed, and

f is the metal content in the feed.

To investigate the collector adsorption on Cu and Al electrode foils, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed using a Hitachi SU3500 SEM system (Japan) equipped with an 80 mm² XMaxN silicon drift detector energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) system (Oxford Instruments, UK). Cu collector electrode foils, whose surfaces were mostly cleaned of graphite by brushing from the anode side, and Al collector electrodes with cathode material still attached were used in the SEM studies. Sample preparation ensured that, after comminution and classification, the Cu foil surfaces were largely free of graphite due to the weak binding agent. In contrast, the cathode material is strongly adhered to the Al foil by the PVDF binder, making mechanical removal potentially damaging; therefore, Al samples were used without scraping. The foils were soaked for 10 minutes in 3000 g/t Aerophine 3418A solution. After careful drying, they were cut into 5×5 mm pieces for SEM analysis. Both secondary electron (SE) and backscattered electron (BSE) signals were collected at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV under high vacuum. During BSE-EDS analysis, the detector deadtime was maintained at approximately 25%, and count rates exceeded 40,000 counts per second (cps). The collected data were analyzed using Aztec software (Oxford Instruments, UK) to identify elements present in the samples.

2.3. Beneficiation Methods

Before the flotation experiments, 50 g of the sample was weighed and added to 1000 mL of tap water, then mixed at 1500 rpm for 15 minutes to remove any remaining black mass. The dispersed black mass was separated using a 74 μm sieve, and the oversize material was fed into a 1.5 L self-aerated Denver-type flotation machine operating at an impeller speed of 1200 rpm. No pH modifiers were used to maintain a more environmentally friendly process. City tap water was utilized throughout the experiments, with the natural pulp pH measured at approximately 8.3.

Once the reagents had sufficient contact with the particles, the air valve was opened to introduce an airflow of 3 L/min, and floating particles were collected during a 3-minute flotation period. The first-stage flotation aimed to separate the naturally hydrophobic plastic fraction from the metallic components. MIBC was employed as the frother reagent for plastic flotation, and no collector reagent was applied at this stage. Following plastic separation, Cu particles remaining in the sink fraction were floated using various collector reagents (KAX, Aerophine-3418A, Aero-3739, Aerofloat-242, and Aerofloat-211).

3. Results

3.1. Characterization Studies

Elemental analysis of the LiB sample used in the experimental studies revealed the presence of several key metals. As summarized in

Table 1, the concentrations of Cu, Al, Co, Ni, and Mn in the initial feed material were 10.38%, 15.78%, 26.94%, 4.23%, and 4.01%, respectively. These metals originate primarily from current collectors (Cu, Al) and active electrode materials (Co, Ni, Mn). Following staged comminution and particle size classification, a significant redistribution of these metals was observed across different size fractions. Cu and Al, which serve as the primary current collector foils, became increasingly concentrated in the coarse fraction (−2+0.2 mm), representing approximately 25% of the feed mass. In this fraction, the combined Cu and Al content reached nearly 65 wt.%, demonstrating efficient liberation and size-based separation of the foil materials during mechanical processing.

By contrast, the fine fraction (−0.2 mm), referred to as “black mass,” was significantly enriched in Co, Ni, and Mn, metals associated with cathode materials. The Co content increased steadily in finer black mass fractions as size reduction progressed, rising from 20.83% in BM 1 to 42.90% in BM 4. This marked enrichment indicates progressive liberation and concentration of Co-bearing cathode materials during successive comminution and classification steps. This process likely reflects the effective detachment of Co from Al current collector foils, governed by the breakdown of strong polymeric binders (e.g., PVDF) at later milling stages.

The carbonaceous content (graphite), primarily coated onto Cu foil, was more readily detached during initial crushing steps due to its relatively weak interfacial bonding. This is evidenced by a high “others” fraction (mainly graphite, plastic, and residual binder) of up to 64.07 wt.% in BM 1.

Moreover, it was observed that intensive comminution not only liberated the active materials but also fragmented the Cu and Al foils into fine particles, thereby contaminating the BM. This contamination was particularly pronounced in BM 3 and BM 4, where the intrusion of Cu and Al into the fine fractions increased significantly. These findings indicate that the multi-stage size reduction process causes foil-structured Cu and Al metals to migrate into the fine fractions, leading to contamination of the BM and potentially reducing overall metal recovery efficiency. A particle size distribution analysis was conducted on the oversize fraction, comprising mainly Cu, Al, plastic materials, and casing metals, retained on the sieve after comminution and classification. The particle size characteristics of this material, which was subsequently used in flotation experiments, were quantified by determining the d₈₀ and d₅₀ values, measured at 0.95 mm and 0.62 mm, respectively. These size parameters are critical for optimizing flotation performance, as they affect the hydrodynamic behavior and surface interactions of particles during the separation process.

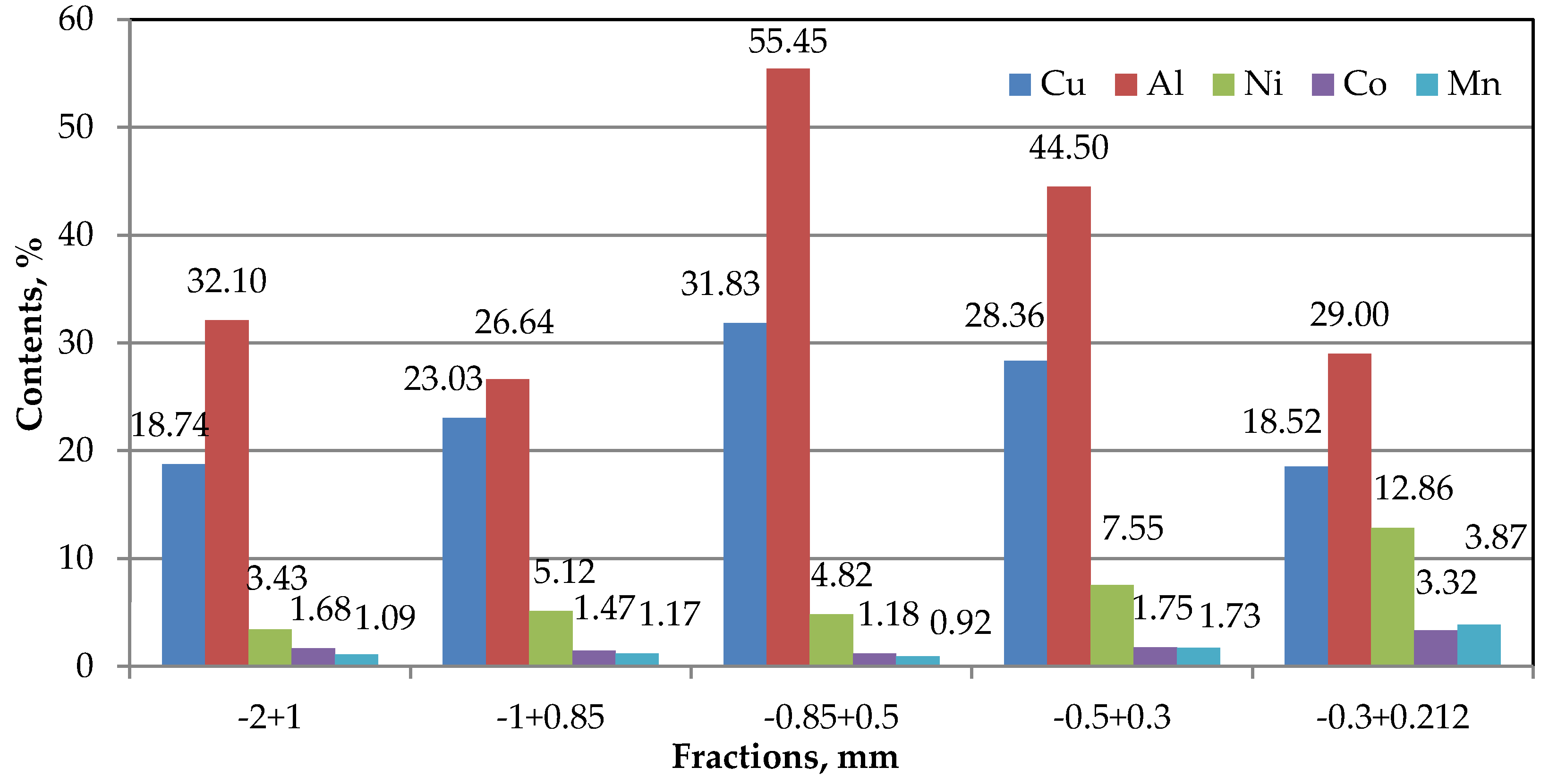

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the highest concentrations of Cu and Al were detected in the −0.8+0.5 mm size fraction. An increasing trend in the content of cathode active metals was observed toward the finer fractions. This suggests that finer Al foil particles retain a considerable amount of unreleased cathode material, indicating incomplete liberation during the comminution process.

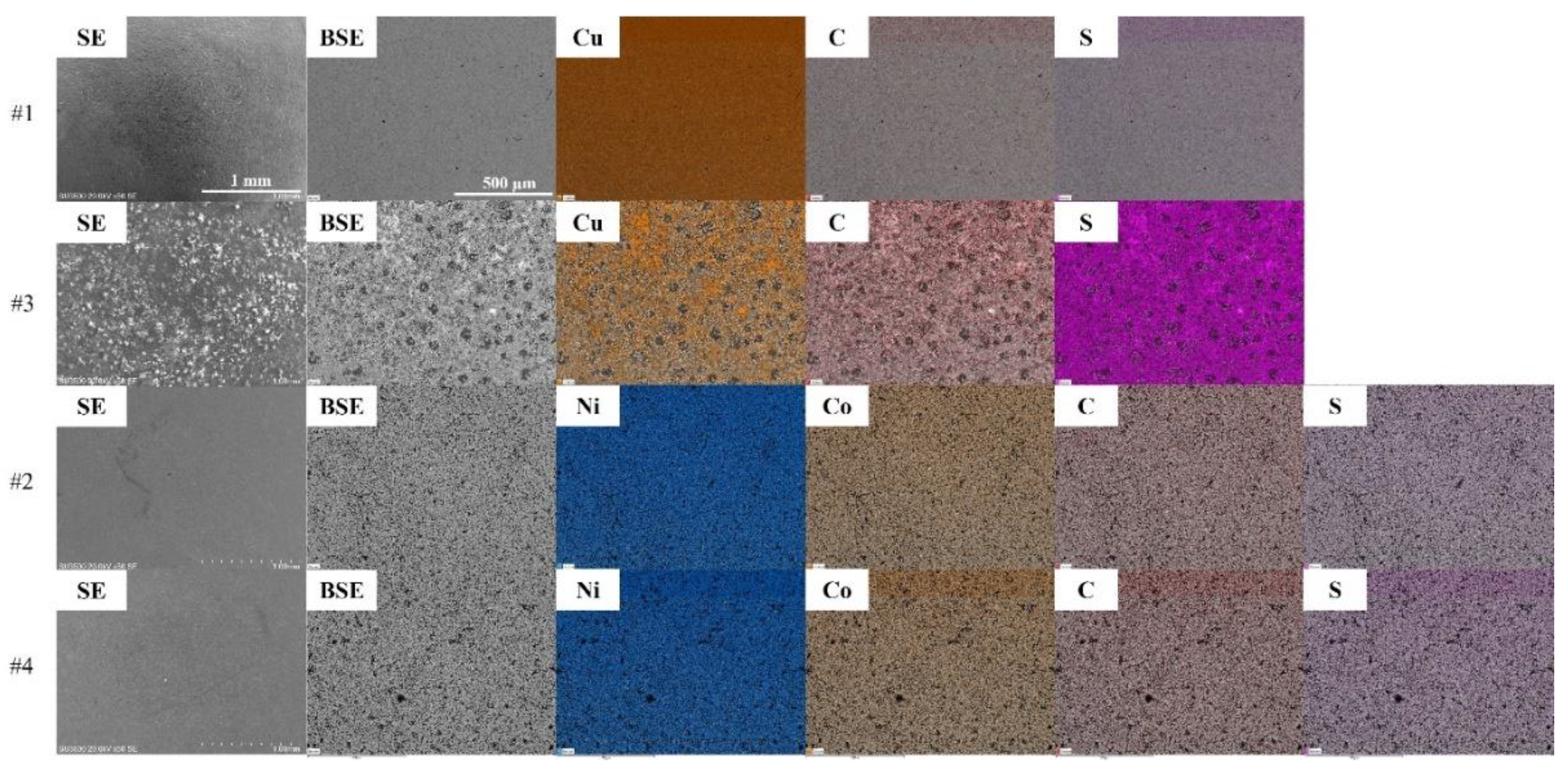

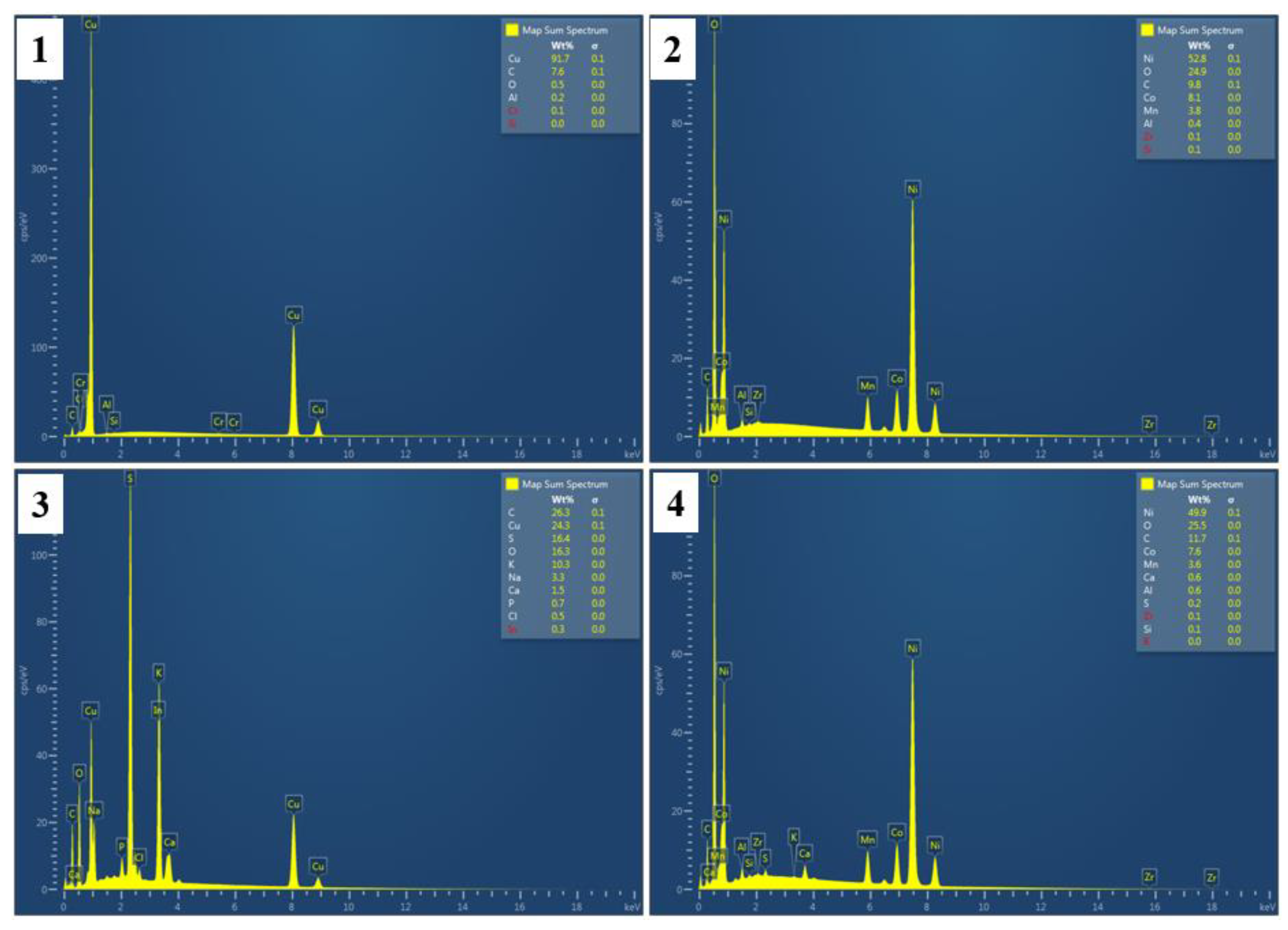

Compared structurally to xanthates, but using phosphorus (P) instead of carbon (C), making Aerophine 3418A a P-based sulfur collector with improved selectivity. Sodium di-isobutyldithiophosphinate-based collector is primarily composed of sodium (Na), phosphorus (P), sulfur (S), carbon (C), and hydrogen (H). Its approximate molecular formula is C₈H₁₈NaPS₂. Due to its phosphorus-sulfur bonding, it exhibits high selectivity and performance in complex sulfide ore systems [

36,

37]. SEM analysis revealed notable changes in surface morphology and composition of the foils after conditioning with Aerophine 3418A. As shown in the SE images in

Figure 3, the surface roughness of Cu foil increased remarkably after conditioning, suggesting the adsorption of 3418A collector. BSE-EDS results support this: as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, after conditioning, the surface C and S contents increased remarkably, from 7.6% to 26.3% and from non-detectable to 16.4%, respectively. Meanwhile, the Cu content decreased from 91.7% to 24.3%. Surface modifications on Cu foil are primarily due to the adsorption of di-isobutyldithiophosphinate species from Aerophine 3418A, where the phosphorus-sulfur functional groups form strong chemisorbed complexes on the mineral surface, altering its flotation behavior. In comparison, no significant changes in the surface roughness and composition could be observed on Al foil after conditioning (as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), suggesting the collector did not adsorb onto its surface.

3.2. Flotation Experiments

Plastics are naturally hydrophobic and possess a much lower specific gravity compared to metals. Fedel et al. [

38] reported that pure PET exhibits a contact angle of 78.9°, confirming its hydrophobic nature. In froth flotation, selective separation is achieved based on differences in particle hydrophobicity. In our previous study on the selective recovery of metals from spent mobile phone LiBs [

39], contact angle measurements were used to assess the surface hydrophobicity of key metallic constituents such as Cu and Al. The relatively low contact angles of unconditioned metallic foils, 50.5° for Cu and 56.1° for Al, support the effectiveness of plastic flotation, where a clear separation between plastics and metals can be realized.

Plastic flotation tests were conducted in five stages: no frother was used in the first stage, followed by four stages with 100 g/t MIBC added each time. Without any frother, about 12% of the total plastics floated, increasing to approximately 79% flotation recovery with 200 g/t of MIBC. The cumulative weight of floated plastics systematically increased, reaching 95% at 400 g/t. Due to size reduction processes dominated by shear forces, metal and plastic components adopted plate-like morphologies and became largely liberated from one another. This morphological transformation provides a significant advantage during flotation, facilitating effective separation of plastic particles, which exhibit substantially higher hydrophobicity than metals, even at relatively coarse particle sizes.

As shown in

Table 2, approximately 16% of the feed material to the first flotation stage was recovered as a plastic product. Approximately 5% by weight of fine-sized Al particles, which exhibit greater floatability than Cu, were transferred to the floated product, whereas Cu particles, with lower floatability than Al, accounted for around 1.5%. A small portion of cathode active materials, still attached to Al foils reported to the plastic fraction.

Particle surface wettability, whether hydrophilic or hydrophobic, can be effectively changed through surface chemical modifications [

40]. Although Al particle surfaces are initially more hydrophobic than Cu surfaces before reagent addition, the hydrophobicity of Cu increases significantly (~95°) and surpasses that of Al (~78°) upon addition of collectors originally designed for natural Cu ore flotation [

39]. In EoL LiBs, Cu and Al are typically present as thin, flat monolayer foils (see

Fig. 5).

This unique morphology enables efficient separation through flotation techniques at significantly coarser particle sizes compared to those typically employed in the flotation of primary ores. Subsequently, the residual material within the cell, following plastic flotation, was processed through the Cu flotation circuit by introducing an appropriate dosage of collector and frother to facilitate the selective recovery of Cu-bearing components.

A copper concentrate assaying 65.13% Cu was successfully obtained with a 96.4% Cu recovery rate when Aerophine 3418A was used. Another commercial reagent commonly preferred in the flotation of natural Cu ores, KAX, also yielded successful results, producing a Cu concentrate assaying 62.47% Cu with a 95.8% Cu recovery. Although the other three collectors produced concentrates with similar Cu grades, their recovery rates were lower due to the reduced quantity of floated material.

When evaluated based on Al content, the best performance was again achieved with the 3418A collector. A sink product containing approximately 77% Al was obtained with a 72.6% Al recovery. The relatively lower Al recovery compared to Cu is attributed to the loss of small-sized Al particles entrained in the Cu concentrate.

Graphite is not typically used in Al current collectors; however, it is predominantly employed as an anode material on Cu surfaces. Considering that some graphite remains adhered to Cu particles after comminution and screening, the “others” category for Cu and Al in

Table 2 likely includes polymer-based separator fragments that were not effectively removed during the initial plastic flotation stage. With the addition of a collector in the Cu flotation circuit, a portion of these particles was recovered, whereas more fibrous and irregularly shaped separator fragments remained in the sink product, often attached to metallic particles. As a potential solution, these insulating plastic materials can be removed either by feeding the material into electrostatic or eddy current separators after drying or by subjecting them to a scavenger flotation circuit in the presence of suitable collectors and frothers.

Based on the characterization and enrichment results, a comprehensive flowsheet was developed for recovering valuable metals from EoL LiBs sourced from EVs (

Fig. 6). Following an initial discharging stage, the EoL LiB sample underwent a four-stage comminution process. The BM, constituting 68.1% of the total weight, was then separated via sieving. The −2+0.2 mm particle size fraction was subjected to froth flotation, during which plastic components were selectively recovered using 500 g/t MIBC as a frother. The floated plastic fraction accounted for 5.0% of the feed and contained negligible metal content, rendering it a discardable waste stream.

The non-floated fraction was further processed in a Cu flotation circuit using 3000 g/t Aerophine 3418A as the collector. This step produced a copper concentrate representing 12.1% of the feed mass, with a Cu grade of 65.13% and a recovery rate of 75.8%. The remaining tailings, constituting 11.6% of the initial feed and primarily composed of Al particles, contained 76.98% Al.

To enhance Cu content and Al recovery, it is recommended to reduce the floatability of Al particles through Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) pre-treatment, followed by feeding them into a cleaning flotation circuit. Alternatively, reshaping the particles into more spherical forms via appropriate grinding techniques may facilitate the separation of Al and Cu using electrostatic or eddy current separation methods. Moreover, the Al-rich sink product obtained after Cu flotation, which remains unfloated due to its low hydrophobicity, can be further processed through magnetic separation to remove associated ferromagnetic metals. This step not only increases the purity of the Al fraction but also enables the production of a marketable magnetic product enriched in Fe and Ni.

4. Conclusion

In the recycling process of EoL LiBs, chemical methods are predominantly employed to obtain battery powder with high economic value. Before these chemical treatments, concentration techniques play a critical role in enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of the overall recovery process. Among such techniques, flotation stands out as a highly effective method for pre-concentrating valuable materials from complex LiB waste streams. Although flotation has been primarily utilized in academic studies for the selective separation of anode and cathode active materials, many of these approaches have yet to reach commercial maturity. Furthermore, the separation of other economically significant components, such as Cu and Al collector electrodes, casing metals, and plastics, has received comparatively little attention.

In this original study, flotation was applied for the recovery of selective metal concentrates from EoL LiBs. Through enrichment processes conducted on a scale considerably larger than that typically applied to natural ores, plastics were separated with high grade and recovery rates, while Cu particles in the remaining metallic fraction were concentrated using commercial Cu flotation reagents. A copper concentrate assaying 65.13% Cu was successfully obtained with a 96.4% Cu recovery rate using Aerophine 3418A.

By obtaining metallic concentrates through ore preparation and enrichment methods that reduce the structural complexity of LiBs, refining capacity can be increased and toxic gas emissions mitigated during thermal processing. Similarly, hydrometallurgical processes can benefit from enhanced capacity and reagent savings. In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest an alternative and efficient flotation-based pre-concentration process that significantly improves the recovery of metal foils, plastics, and casing metals from LiBs, thereby complementing subsequent chemical recycling operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B.; methodology, F.M., N.İ.D. and F.B.; validation, F.M., F.B., Z.S. and R.L.; formal analysis, B.T.K. and R.L..; investigation, F.M., N.İ.D. and F.B.; resources, F.B..; data curation, F.M. and F.B..; writing—original draft preparation, F.M., F.B., Z.S., R.L., and B.T.K.; writing—review and editing, F.B., Z.S., R.L. and B.T.K.; visualization, F.M., F.B. and R.L.; supervision, F.B.; project administration, F.M. and F.B.; funding acquisition, F.M. and F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.