Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

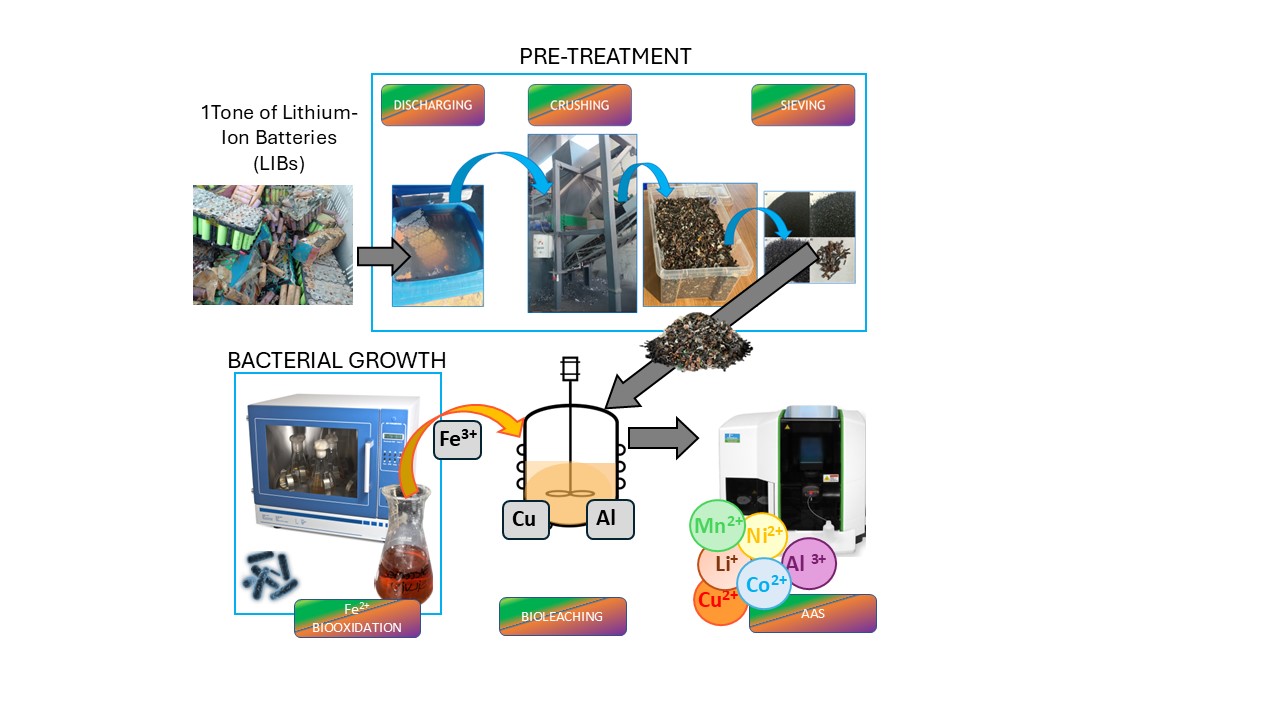

2.1. Spent LIBs: Sample Preparation and Metal Characterization

2.2. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.3. Bioleaching of Coarse Black Mass Fraction >500 microns

2.4. Bioleaching of Fine Black Mass Fraction < 500 microns

2.5. Bioleaching of Unsorted Black Mass

2.6. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BM Metal Characterization

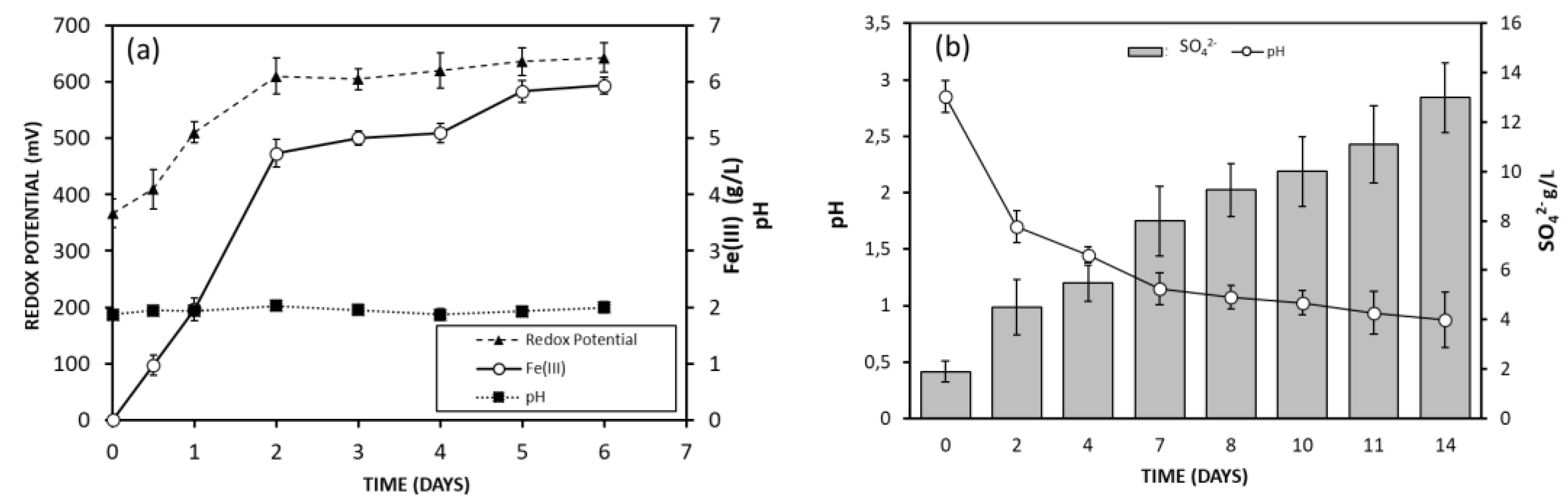

3.2. Fe (III) and Acid Production by Microorganisms

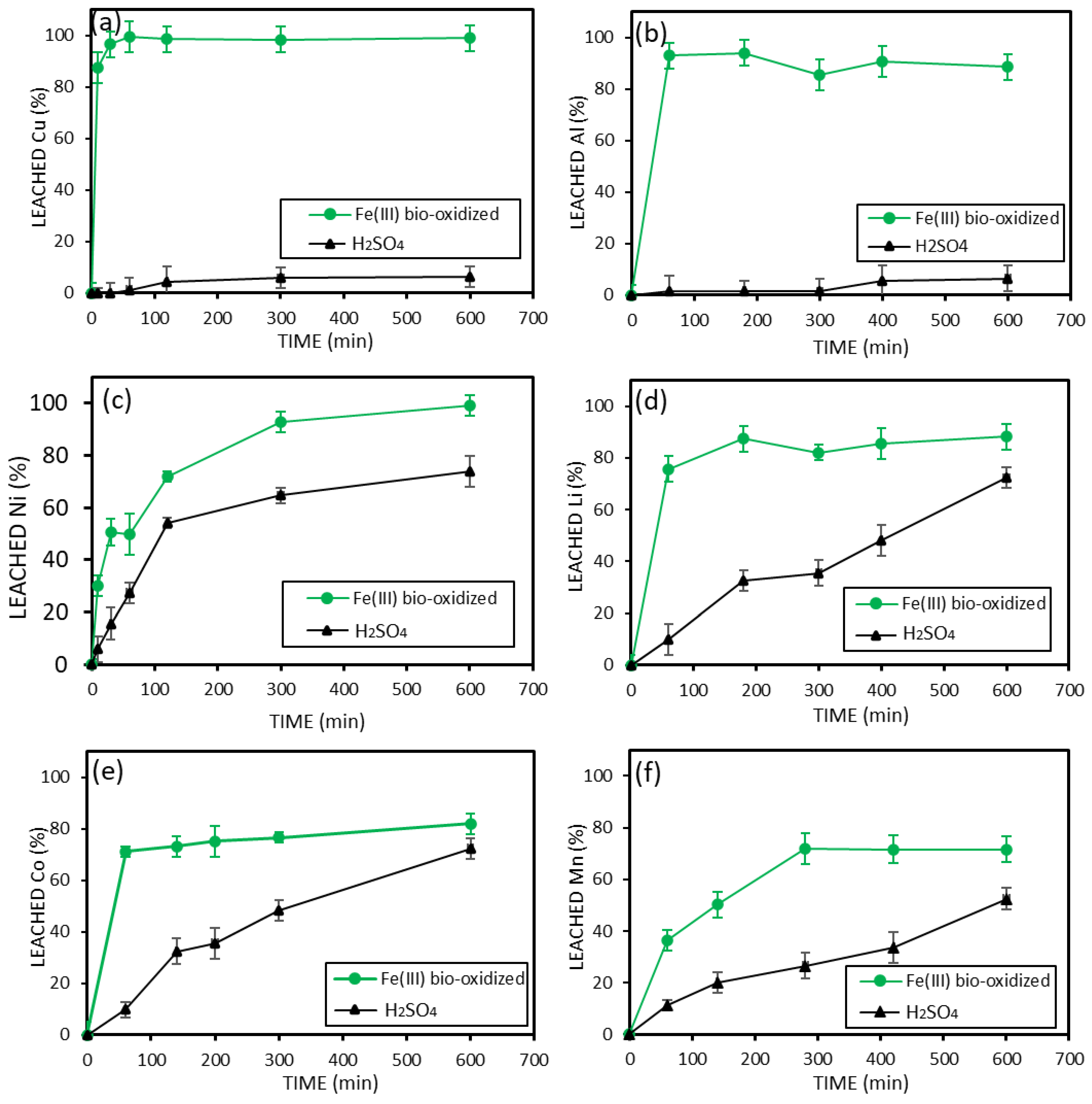

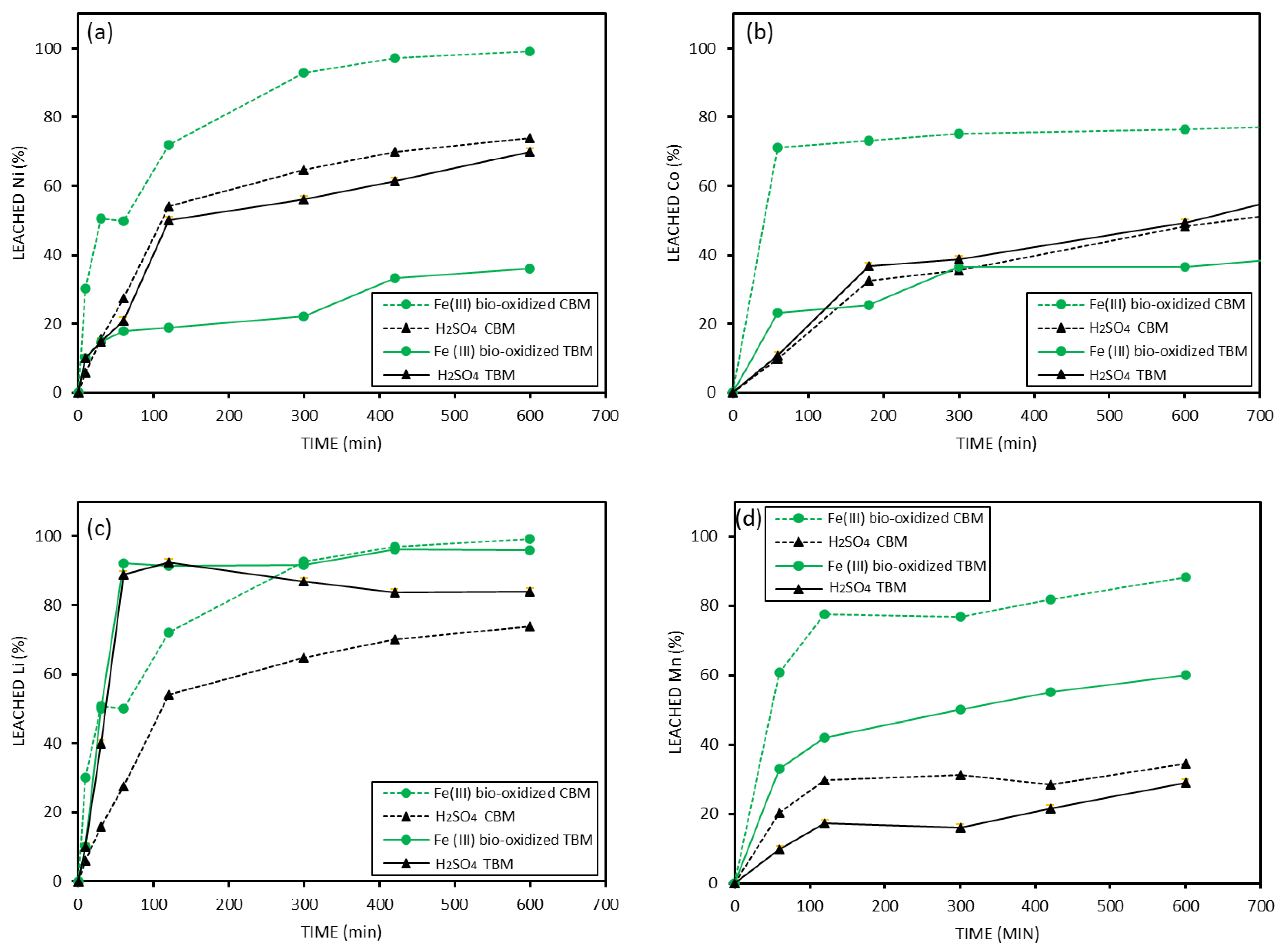

3.3. Metal Leaching from Coarse Black Mass > 500 Microns

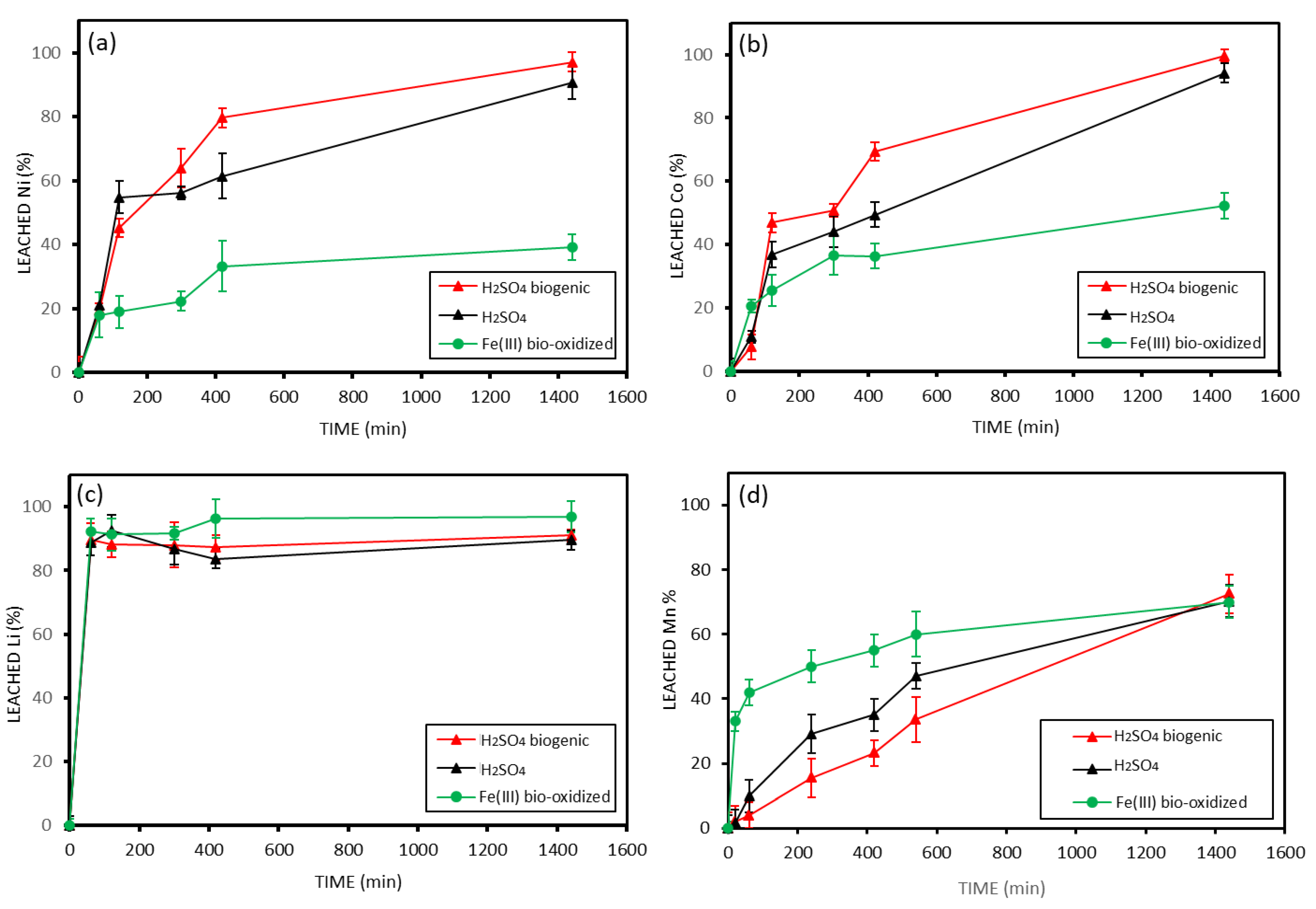

3.4. Leaching Results of Fine Black Mass < 500 Microns

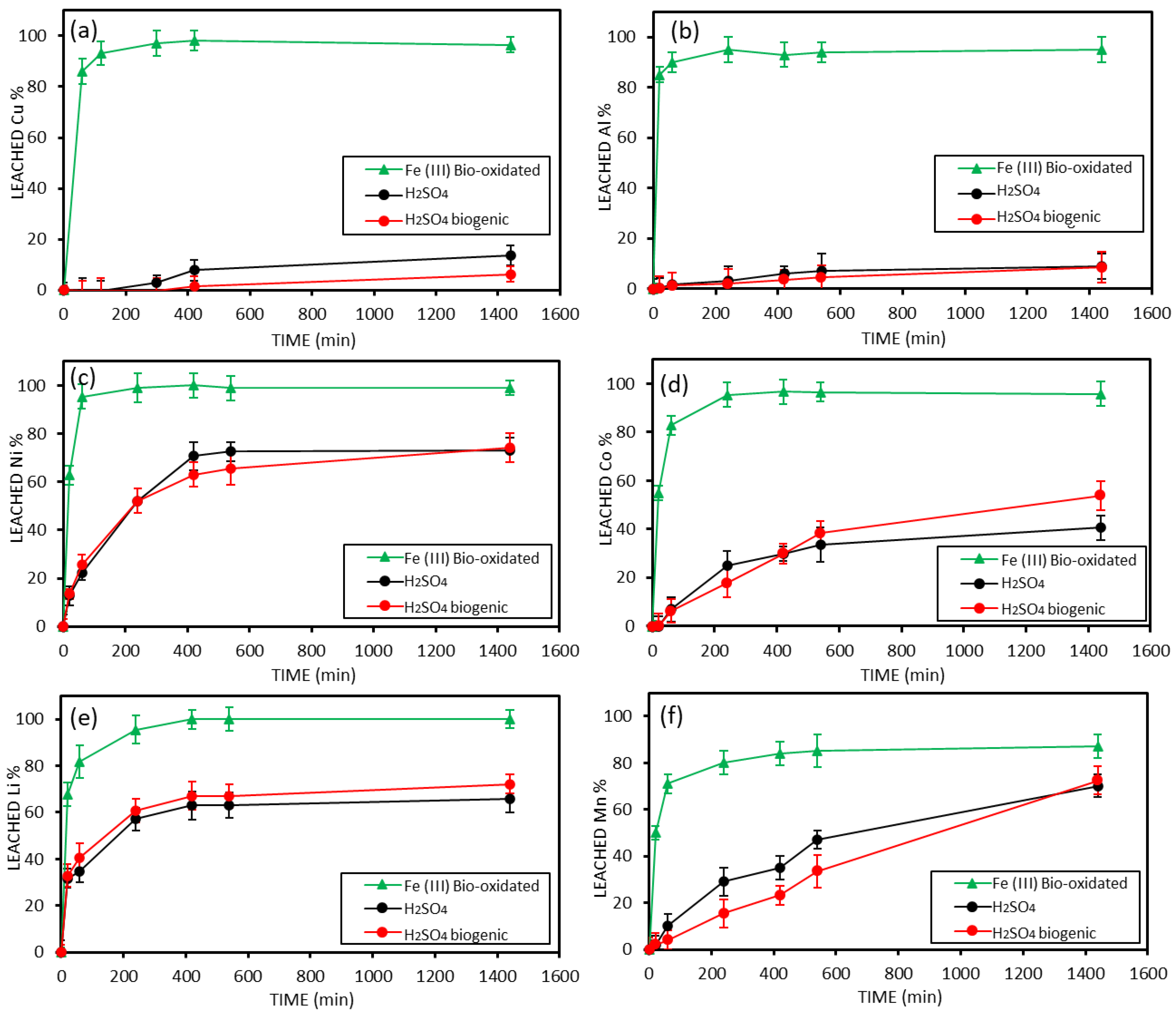

3.5. Leaching Results of Unsorted Black Mass

4. Conclusions

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Okonkwo, E.G.; Huang, G.; Xu, S.; Sun, W.; He, Y. On the sustainability of lithium-ion battery industry – A review and perspective. Energy Storage Materials. 2021, 36, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Chen, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, F.; Guo, Y.; Bhagat, R.; Zheng, Y. Critical review of life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: lifespan perspective. eTransportation. 2022, 12, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosakazemi, F.; Ghassa, S.; Jafari, M.; Chelgani, S.C. Bioleaching for Recovery of Metals from Spent Batteries - A Review. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review. 2022, 44, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianliai, Z.; Jinhui, L.; Narendra, S. Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Battery: A Critical Review. Enviromental Science and Technology. 2014, 44, 1129–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, P.; Boroumand, Y.; Rabiei, P.; Baghgaderani, S. S. , Mokarian, P., Mohagheghian, F., Mohammed, L.J., Razmiou, A. Lithium bioleaching: An emerging approach for the recovery of Li from spent lithium-ion batteries. Chemosphere. 2021, 277, 130196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, J.J.; Rarotra, S.; Krikstolaiyte, V.; Zhuoran, K.W.; Cindy, Y.D.; Tan, X. Y. , Carboni, M., Meyer, D., Yan, Q., Srinivasan, M. Green Recycling Methods to Treat Lithium-Ion Batteries E-waste: A circular Approach to Sustainability. Advanced Materials. 2022, 34, 2103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzal, E.; Solé; M; Lao, C. ; Gamisans, X.; Dorado, A.D. Elemental Copper Recovery from e-Wastes Mediated with a Two-Steps Bioleaching Process. Waste and biomass Valorization, 2020, 11, 5457–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.G.; Silva, M. T. , Días, R. M., Cardoso, V.L., Resende, M.M.. Biolixiviation of Metals from Computer Printed Circuit Boards by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and Bioremoval of Metals by Mixed Culture Subjected to a Magnetic Field. Current Microbiology 2023, 80, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.R.; Ilyas, S.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Trinh, H.B.; Ghauri, A.M.; Ilyas, N. Biotechnological recycling of critical metals from waste printed circuit boards. J. Chem. Technol. Biothechnol. 2020, 95, 2796–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, I.; Burrell, B.; Reed, C.; West, A. C. , Banta S., Metals and minerals as a biotechnology feedstock: engineering biomining microbiology for bioenergy applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. B. , Zhang L. J., Peng J., Ge Y., Tian Z., Sun J. X., Cheng H. N., Zhou H. B. Cleaner utilization of electroplating sludge by bioleaching with a moderately thermophilic consortium: a pilot study. Chemosphere. 2019, 232, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, A.; Hedrich, S.; Vasters, J.; Drobe, M.; Sand, W. Biomining: metal recovery from ores with microorganisms. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2013, 141, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B. K. , Zhang, B. , Tran, P. T. M., Zhang, J., Balasubramanian, R. Recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries for a sustainable future: recent advancements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 5552–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Pan, Z.; Su, X.; An, L. Recycling of lithium-ion batteries: Recent advances and perspectives. Journal of Power Sources. 2018, 399, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isildar, A.; Van Hullebusch, E. D. , Lenz M., Laing, G. D., Marra A., Cesario A., Panda S., Akcil A., Kucuer M. A., Kuchate, K. Biotechnological strategies for the recovery of valuable and critical raw materials from waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) – A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2019, 362, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, N.; Binnemans, K.; Riaño, S. Solvometallurgical recovery of cobalt from lithium-ion battery cathode materials using deep-eutectic solvents. Green chemisty 2020, 22, 4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassa s Farzanegan, A.; Gharabaghi, M.; Abdollahi, H. The reductive leaching of waste lithium-ion batteries in presence of iron ions: Process optimization and kinetics modelling. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 262, 121312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dai, G.; Liu, R.; Wang, S.; Ju, Y.; Jiang, H.; Jiao, S.; Duan, C. Separation and recovery of nickel cobalt manganese lithium from waste ternary lithium-ion batteries. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 306, 122559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawonezvi, T.; Nomnqa, M.; Petrik, L.; Bladergroen, B.J. Recovery and Recycling of Valuable Metals from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Comprehensive Review and Analysis. Energies 2023, 16, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, G. Xu, S., He, Y., Liu, X. 2016. Thermal Treatment Process for the Recovery of Valuable Metals from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 165, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Bang, J.; Yoo, J.; Shin, Y.; Bae, J.; Jeong, J.; Kim, K.; Dong, P.; Kwon, K. A Comprehensive Review on the Pretreatment Process in Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 294, 126329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Ye, M.; Liang, J.; Guan, Z.; Li, S.; Deng, Y.; Gan, Q.; Liu, Z.; Fang, X.; Sun, S. Feasibility of reduced iron species for promoting Li and Co recovery from spent LiCoO2 batteries using mixed-culture bioleaching process. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 830, 154577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, J.J.; Madhavi, S.; Cao, B. Metal extraction from spent lithium-iom batteries (LIBs) at high pulp density by enviromental friendly bioleaching process. Journal of cleaner production 2021, 280, 12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Tan, N.; Zhu, M.; Tan, W.; Daramola, D.; Gu, T. Advances in bioleaching of waste lithium batteries under metal ion stress. Bioresources and Bioprocessing 2023, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Guo, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, F.; Xin, B. Bioleaching of valuable metals Li, Co, Ni and Mn from spent electric vehicle Li-ion batteries for the purpose of recovery. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 116, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, Y.; Chu, H.; Tian, B.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Xin, B. Enhanced metal bioleaching mechanisms of extracellular polymeric substance for obsolete LiNixCoyMn1-x-yO2 at high pulp density. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 318, 115429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, S.; Chen, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, B. Bioleaching waste printed cirduit boards by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and its kinetics aspect. Journal of Biotechnology 2014, 173, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; An, N.; Wen, L.; Jiang, X.; Hou, F.; Liang, J. Recent progress on the recycling technology of Li-ion batteries. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2020, 55, 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li; L; Zhai, L. ; Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, R.; Wu, F.; Amine, K. Recovery of Valuable Metals from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries by Ultrasonic-Assisted Leaching Process. Journal of Power Sources 2014, 262, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranikova, M.; Ebin, B.; Mikhailova, S.; Steenari, B.M. Investigation of the effects of thermal treatment on the leachability of Zn and Mn from discarded alkaline and Zn-C batteries. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 170, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, A.; Mousavi, S.M.; Vakilchap, F.; Baniasadi. Application of a mixed culture of adapted acidophilic bacteria in two-step bioleaching of spent lithium-ion laptop batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 378, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, W.; Zhang, X.; Gu, T.; Zhu, M.; Ran, W. Oxidative Stress Induced by Metal Ion in Bioleacing of LiCoO2 by an Acidophilic Microbial Consortium. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Kim, D.J.; Ralph, D.E.; Ahn, J.G.; Rhee, Y.H. Bioleaching of metals from spent lithium-ion secondary batteries using Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Waste Management 2008, 28, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.; Deng, X.; Luo, S.; Luo, X.; Zou, J. A copper-catalyzed bioleaching process for enhancement of cobalt dissolution from spent lithium-ion batteries. J. of Hazardous Materials 2012, 199-200, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalan, Z.; Xingzhong, Y.; Longbo, J.; Jia w Hou, W.; Renpeng, G.; Jingjing, Z.; Guangming, Z. Regeneration and reutilitzation of cathode materials from spent lithium-ion batteries. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 383, 123089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S. A review on electrolyte additives for lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2006, 162, 1379–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Seyyed, M. M.; Farzane, V.; Mahsa, B. Application of a mixed culture of adapted acidophilic bacteria in two-step bioleaching of spent lithium-ion laptop batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 378, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaloo Horeh, N.; Mousavi, S.M.; Shojaosadati, S.A. Bioleaching of valuable metals from spent lithium-ion mobile phone batteries using Aspergillus niger. Journal of Power Sources 2016, 320, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Sun, S. ; Mu; Y; Song, X. ; Yu, J. Recovery of lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese from spent lithium-ion batteries using L-tartaric acid as leachant. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W. Wang, Z.; Cao, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z. A Critical Review and Analysis on the Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1504–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, T.; Bahaloo-Horeh, N.; Mousavi, S.M. Environmentally friendly recovery of valuable metals from spent coin cells through two-step bioleaching using Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 235, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, B.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, S.; Li, L. Bioleaching mechanism of Co and Li from spent lithium-ion battery by the mixture of acidophilic sulfur-oxidizing and iron-oxidizing bacteria. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 6163–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Cao, H.; Zhao, C.; Lin, X.; Ning, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, W.; Sun, Z. A Closed-Loop Process for Selective Metal Recovery from Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Batteries through Mechanochemical Activation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 9972–9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanfar, M.; Sartaj, M.; Kazemeini, S. A greener method to recover critical metals from spent lithium-ion batteries (LIBs): Synergistic leaching without reducing agents. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 366, 121862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

BLACK MASS METAL CONTENT |

Weight % |

Cu % |

Co % |

Al % |

Ni % |

Mn % | Li % |

| CBM > 500 microns | 86 | (11.1 - 18.1) | (1.8 - 2.8) | (7.2 - 9.0) | (14.0 - 19.0) | (2.2 - 3.4) | (1.4 - 2.3) |

| FBM < 500 microns | 14 | (0.6 - 1.0) | (3.4 - 4.2) | (0.5 - 0.9) | (23.7 - 27.7) | (2.3 - 3.3) | (1.9 - 3.1) |

| UBM | 100 | (9.6 - 15.7) | (2.0 - 5.6) | (6.3 - 7.9) | (15.4 - 20.2) | (2.2 - 3.4) | (1.5 - 3.3) |

|

Microorganism |

LIB Waste Preparation |

Leaching conditions |

Time |

Efficiency |

Method |

REFs |

|

| Bacterial Consortia | |||||||

| A. ferrooxidans (isolated) and A. thiooxidans (isolated) | Manually dismantled. Cathodes treated with NMP at 100ºC for 1-2 h to remove the binder LiNixCoyMn1-x-yO2, LiMn2O4 and LiFePO4. Particle size <150 microns |

pH = 1,5 T = 30ºC Pulp Density 1% (w/v) |

9 days | Li 98%, Ni 97%, Co 96%, Mn 90% | One-step bioleaching |

[25] | |

| Bacterial consortia: A. ferrooxidans (PTCC1647) and A. thiooxidans(PTCC1717) (3/2) | Manually dismantled. Active cathode material an graphite were scratched from CU an Al respectively, then ball milled and sieved. Particle size < 75 microns |

pH = 1,5 T = 32ºC Pulp Density 4% (w/v) |

16 days | Li 99,2%, Co 50,4%, Ni 89,4% | Two-step bioleaching |

[31] | |

| Acidophilic microbial consortium, mainly contained L. ferriphilum and S. thermosulfidooxidans | Purchased LiCoO2 powder of a purity of 99,8%. Particle size 105-130 micron |

pH = 1,25 T = 42ºC Pulp Density 5% (w/v) |

1,5 days | Li 98,1%, Co 96,3% | two-step bioleaching | [32] | |

| A. caldus and Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans | Manually dismantled. Mechanically crushing electrodes. Particle size < 200 microns |

pH = 2,5 T = 30ºC Pulp Density 20 g/L |

12 hours | Li 100%, Co 99% | two-step bioleaching | [22] | |

| Bacterial consortia: A. thiooxidans, L. ferriphilum and A. ferrooxidans | Manually dismantled, Separated cathode parts and treated with N-methylpyrrolidone at 100ºC for 1 h to remove the binder and separate Al. Milled and sieved. Particle size <150 micron |

pH = 1 T = 30ºC Pulp Density 4% (w/v) |

1 day | Li 100%, Ni 42%, Co 40%, Mn 40% | Two-step bioleaching | [26] | |

| Single species bacterium | |||||||

| A. ferrooxidans (ATCC19859) | Manually dismantled. Cathodes milled. Particle size <150 micron |

pH = 2,5 T=30ºC Pulp Density 0,5% (w/v) |

15 days | Li 10%, Co 65% | One-step bioleaching |

[33] | |

| A. ferrooxidans | Manually dismantled. Cathode selected and ground to a particle size < 75 micron | pH = 2 T = 35ºC Pulp Density 1% (w/v) |

6 days | Co 90% | One-step bioleaching | [34] | |

| A. ferrooxidans (DSMZ 1927) | Manually dismantled, electrodes were crashed. Powder was autoclaved to remove binder Particle size < 100 micron |

pH = 2 T = 30ºC Pulp Density 100g/L |

72 hours | Li 60%, Co 94% | two-step bioleaching | [23] | |

| A. ferrooxidans | 1 Tone of various batteries from scooters and e-bikes shredding. Particle size < 5mm |

pH = 1,5 T = Ambient of 27ºC Pulp Density 1% (w/v) |

30 minutes | Cu 97%, Al 96%, Ni 98%, Co 92%, Li Li 90%, Mn 80% | Two-step bioleaching | This work | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).