Submitted:

15 September 2024

Posted:

16 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

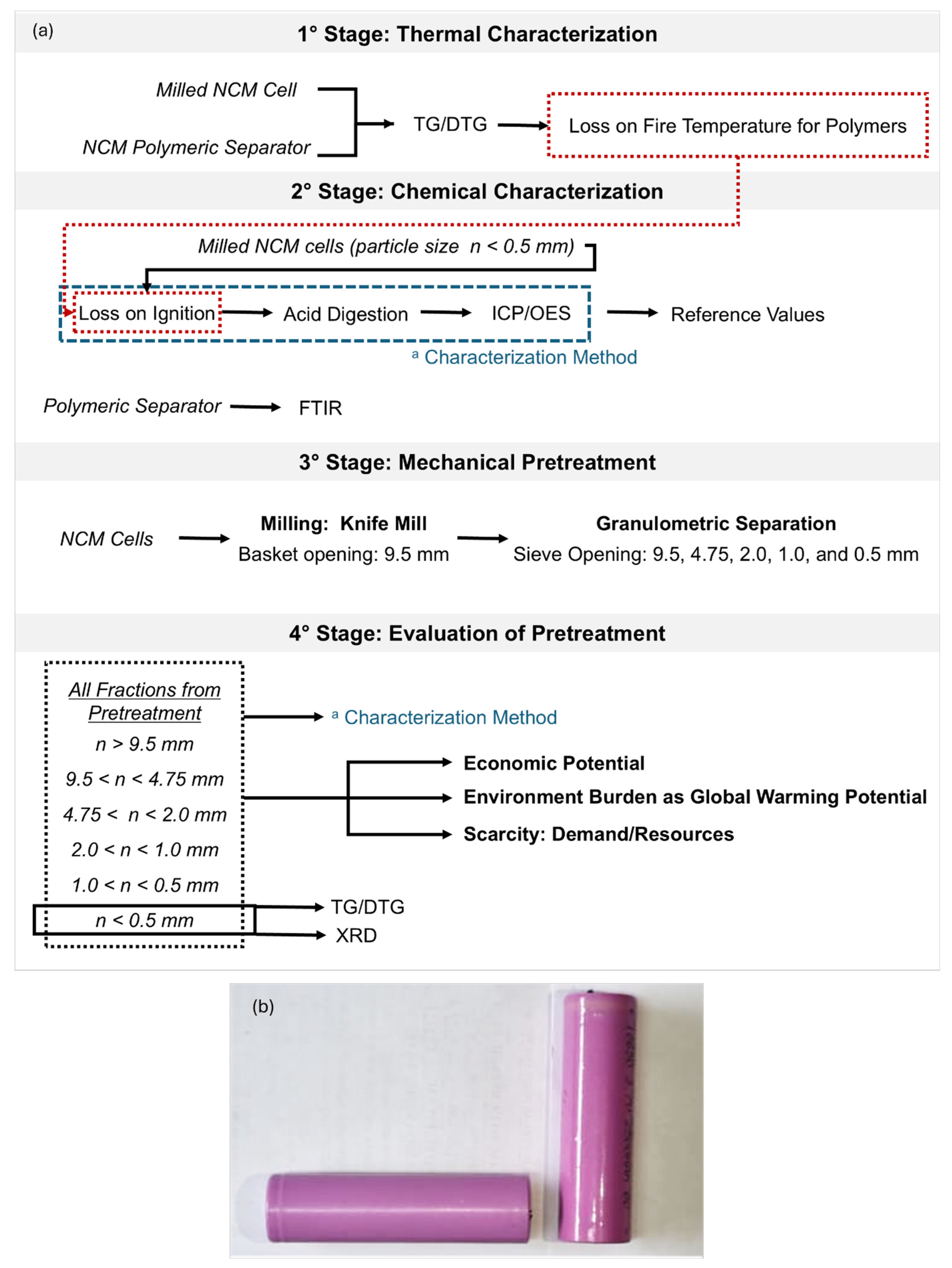

2.1. Characterization of NCM Cells

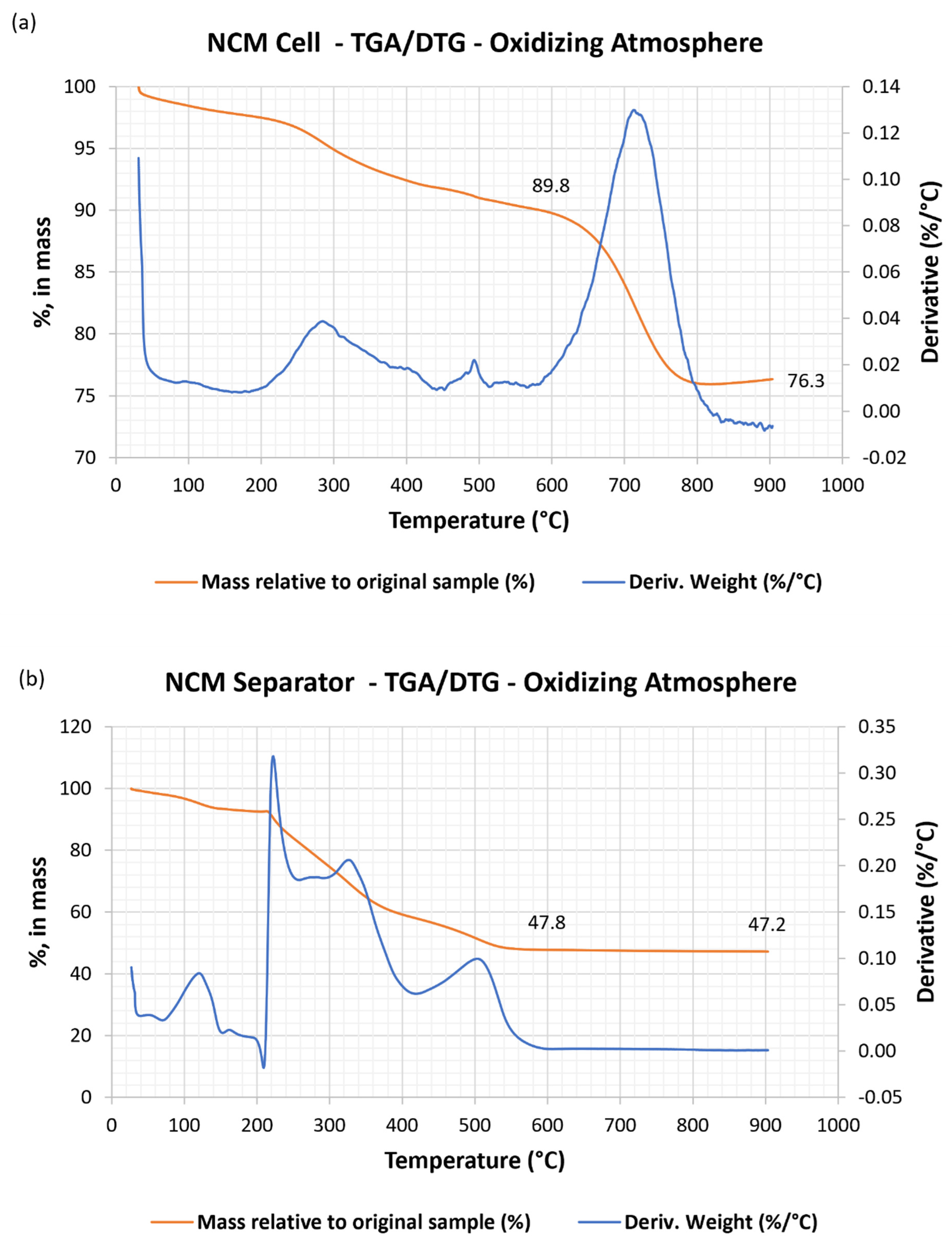

2.1.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis and Loss on Ignition Temperature

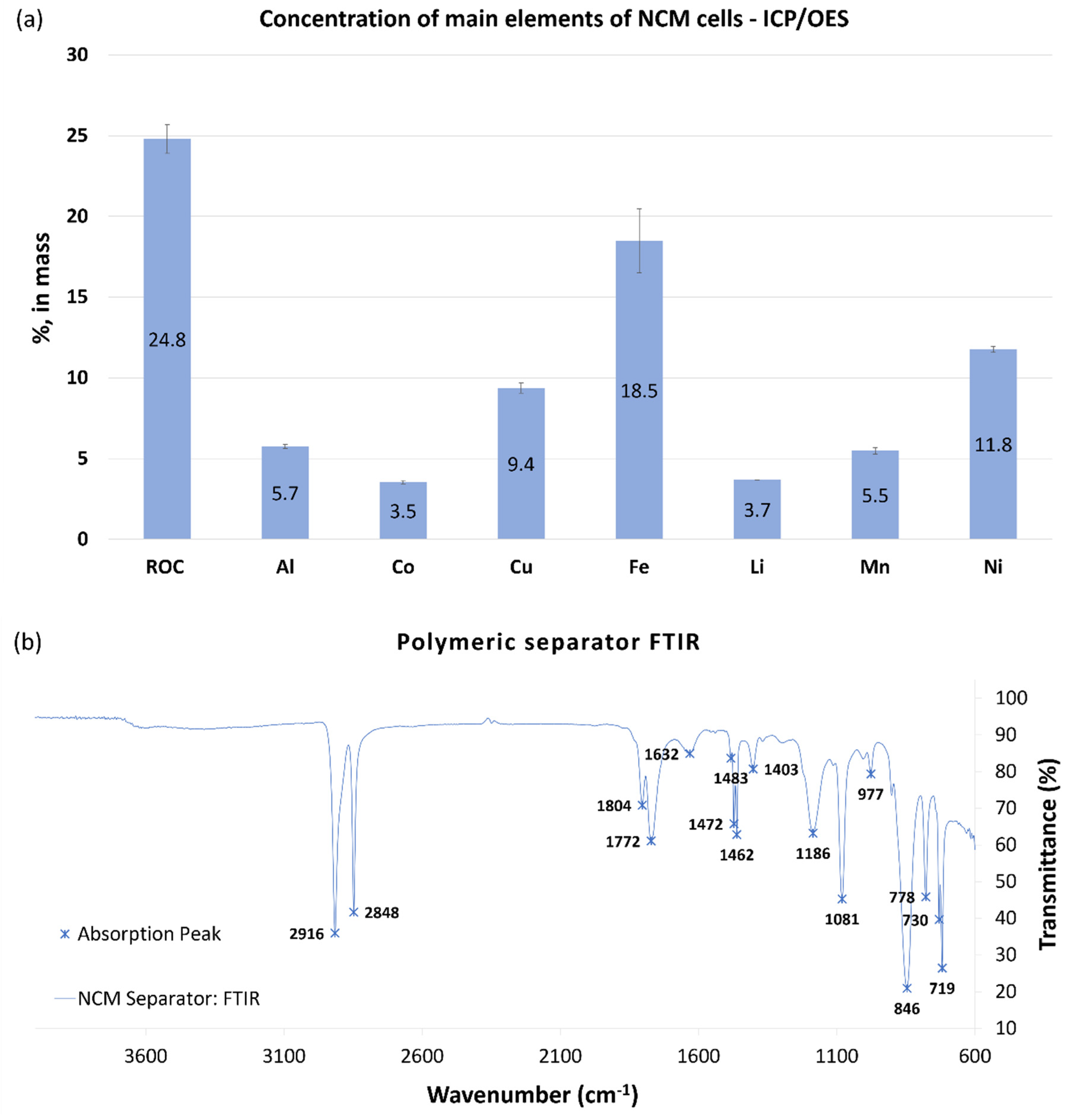

2.1.2. Chemical Characterization of NCM Cells

2.2. Mechanical Pre-Treatment for Recycling

2.2.1. Chemical Evaluation of All Fractions

2.2.2. Black Mass (Fraction < 0.5mm): TG/DTG and X-ray Diffraction

2.2.3. Economic, Environmental, and Scarcity Potential Evaluation

2.2.3.1. Economic Potential

| Element | Material | Mass Conversion Factor | Market Value (USD/kg) |

| Al | Aluminum | 1 | 2.290 1 |

| Co | Cobalt | 1 | 26.625 1 |

| Cu | Copper | 1 | 9.10 1 |

| Fe | Steel Rebar | 1 | 0.425 1 |

| Li | Li2CO3 | 5.322 | 11.78 1 |

| Mn | Mn2O3 | 4.260 | 1.25 2 |

| Ni | Nickel | 1 | 15.80 1 |

2.2.3.2. Environmental Burden as Global Warming Potential

2.2.3.3. Scarcity

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of NCM Cells

3.1.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis and Loss on Ignition Temperature

3.1.2. Chemical Characterization of NCM Cells

3.2. Mechanical Pre-Treatment for Recycling

3.2.1. Chemical Evaluation of All Fractions

3.2.2. Black Mass (Fraction < 0.5mm): TG/DTG and X-ray Diffraction

3.2.3. Economic, Environmental, and Scarcity Potential Evaluation

3.2.3.1. Economic Potential

3.2.3.2. Environmental Burden as Global Warming Potential

3.2.3.3. Scarcity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- IEA, I.E.A. Global EV Outlook 2023. Geo 2023, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, C.; Zhou, L.; Wu, X.; Sun, W.; Yi, L.; Yang, Y. Technology for Recycling and Regenerating Graphite from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chinese J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 39, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armand, M.; Axmann, P.; Bresser, D.; Copley, M.; Edström, K.; Ekberg, C.; Guyomard, D.; Lestriez, B.; Novák, P.; Petranikova, M.; et al. Lithium-Ion Batteries – Current State of the Art and Anticipated Developments. J. Power Sources 2020, 479, 228708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2023. 2023, 210. [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.-J.; Youn, S.; Yoon, C.S.; Sun, Y.-K. Comparison of the Structural and Electrochemical Properties of Layered Li[NixCoyMnz]O2 (x = 1/3, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 and 0.85) Cathode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2013, 233, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, S.-M.; Hu, E.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, X.; Senanayake, S.D.; Cho, S.-J.; Kim, K.-B.; Chung, K.Y.; Yang, X.-Q.; Nam, K.-W. Structural Changes and Thermal Stability of Charged LiNi x Mn y Co z O 2 Cathode Materials Studied by Combined In Situ Time-Resolved XRD and Mass Spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 22594–22601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCalla, E.; Carey, G.H.; Dahn, J.R. Lithium Loss Mechanisms during Synthesis of Layered LixNi2−xO2 for Lithium Ion Batteries. Solid State Ionics 2012, 219, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, M.; Du, R.; Yang, W.; Liu, Z.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Sun, X. Stability of Li 2 CO 3 in Cathode of Lithium Ion Battery and Its Influence on Electrochemical Performance. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 19233–19237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkrob, I.A.; Gilbert, J.A.; Phillips, P.J.; Klie, R.; Haasch, R.T.; Bareño, J.; Abraham, D.P. Chemical Weathering of Layered Ni-Rich Oxide Electrode Materials: Evidence for Cation Exchange. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A1489–A1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. The Challenges, Solutions and Development of High Energy Ni-Rich NCM/NCA LiB Cathode Materials. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1347, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Hua, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, H.; Yuan, Z. Assessment of End-of-Life Electric Vehicle Batteries in China: Future Scenarios and Economic Benefits. Waste Manag. 2021, 135, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, L.; Linh, D.; Shui, L.; Peng, X.; Garg, A.; LE, M.L.P.; Asghari, S.; Sandoval, J. Metallurgical and Mechanical Methods for Recycling of Lithium-Ion Battery Pack for Electric Vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Luo, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, C.; Guo, J.; Cheali, P.; Xia, X. Progress, Challenges, and Prospects of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries Recycling: A Review. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 89, 144–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Kendall, A.; Slattery, M. Electric Vehicle Lithium-Ion Battery Recycled Content Standards for the US – Targets, Costs, and Environmental Impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuol, D.A.; Toniasso, C.; Jiménez, B.M.; Meili, L.; Dotto, G.L.; Tanabe, E.H.; Aguiar, M.L. Application of Spouted Bed Elutriation in the Recycling of Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 275, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuis, M.; Aluzoun, A.; Keppeler, M.; Melzig, S.; Kwade, A. Direct Recycling of Lithium-Ion Battery Production Scrap – Solvent-Based Recovery and Reuse of Anode and Cathode Coating Materials. J. Power Sources 2024, 593, 233995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colledani, M.; Gentilini, L.; Mossali, E.; Picone, N. A Novel Mechanical Pre-Treatment Process-Chain for the Recycling of Li-Ion Batteries. CIRP Ann. 2023, 72, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yuan, X.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T.; Xie, W. Recent Advances in Pretreating Technology for Recycling Valuable Metals from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.; Jung, Y.; Jo, M.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Yang, D.; Rhee, K.; An, E.M.; Sohn, J.; Kwon, K. Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Battery Cathode Materials by Ammoniacal Leaching. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 313, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM-E473 Standard Terminology Relating to Thermal Analysis and Rheology. ASTM Int. 2014, 1–3.

- ASTM-E1131 Standard Test Method for Compositional Analysis by Thermogravimetry. ASTM Int. 2015, 08, 6.

- Camargo, P.S.S.; Gomes Osório Torres, G.; Pacheco, J.A.S.; Cenci, M.P.; Kasper, A.C.; Veit, H.M. Mechanical Methods for Materials Concentration of Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) Cells and Product Potential Evaluation for Recycling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily Metal Prices Metal Price Charts 2024.

- Business Analytiq Manganese Price July 2024 2024.

- Ortego, A.; Calvo, G.; Valero, A.; Iglesias-Émbil, M.; Valero, A.; Villacampa, M. Assessment of Strategic Raw Materials in the Automobile Sector. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, A.; Valero, A.; Calvo, G.; Ortego, A. Material Bottlenecks in the Future Development of Green Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, J.; Qin, Y. Recycling Hazardous and Valuable Electrolyte in Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries: Urgency, Progress, Challenge, and Viable Approach. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 8718–8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miandad, R.; Rehan, M.; Barakat, M.A.; Aburiazaiza, A.S.; Khan, H.; Ismail, I.M.I.; Dhavamani, J.; Gardy, J.; Hassanpour, A.; Nizami, A.S. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Plastic Waste: Moving toward Pyrolysis Based Biorefineries. Front. Energy Res. 2019, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.B.; Kim, J.S. Pyrolysis Products from Various Types of Plastics Using TG-FTIR at Different Reaction Temperatures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 171, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slough, G. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Powdered Graphite for Lithium-Ion Batteries. TA Instruments, 1–5.

- Nazarov, V.I.; Makarenkov, D.A.; Retivov, V.M.; Popov, A.P.; Aflyatunova, G.R.; Sivachenko, L.A.; Sotnik, L.L. Features of the Pyrolysis Process of Waste Batteries Using Carbon Black as an Additive in the Construction Industry. Constr. Mater. Prod. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, A.V.M.; Santana, M.P.; Tanabe, E.H.; Bertuol, D.A. Recovery of Valuable Materials from Spent Lithium Ion Batteries Using Electrostatic Separation. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 169, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegan, D.P.; Cooper, S.J.; Tjaden, B.; Taiwo, O.O.; Gelb, J.; Hinds, G.; Brett, D.J.L.; Shearing, P.R. Characterising the Structural Properties of Polymer Separators for Lithium-Ion Batteries in 3D Using Phase Contrast X-Ray Microscopy. J. Power Sources 2016, 333, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mahdavi, H. Recent Development of Polyolefin-Based Microporous Separators for Li−Ion Batteries: A Review. Chem. Rec. 2020, 20, 570–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulmine, J. V.; Janissek, P.R.; Heise, H.M.; Akcelrud, L. Polyethylene Characterization by FTIR. Polym. Test. 2002, 21, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signoret, C.; Edo, M.; Caro-Bretelle, A.S.; Lopez-Cuesta, J.M.; Ienny, P.; Perrin, D. MIR Spectral Characterization of Plastic to Enable Discrimination in an Industrial Recycling Context: III. Anticipating Impacts of Ageing on Identification. Waste Manag. 2020, 109, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brogly, M.; Bistac, S.; Bindel, D. Advanced Surface FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of Poly(Ethylene)-Block-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Thin Film Adsorbed on Gold Substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Jordi FTIR for Identification of Contamination. Jordi 2017.

- Martins, P.; Lopes, A.C.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Electroactive Phases of Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride): Determination, Processing and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviello, D.; Toniolo, L.; Goidanich, S.; Casadio, F. Non-Invasive Identification of Plastic Materials in Museum Collections with Portable FTIR Reflectance Spectroscopy: Reference Database and Practical Applications. Microchem. J. 2016, 124, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pražanová, A.; Kočí, J.; Míka, M.H.; Pilnaj, D.; Plachý, Z.; Knap, V. Pre-Recycling Material Analysis of NMC Lithium-Ion Battery Cells from Electric Vehicles. Crystals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C.; Kaas, A.; Peuker, U.A. Influence of the Cell Type on the Physical Processes of the Mechanical Recycling of Automotive Lithium-Ion Batteries. Metals (Basel). 2023, 13, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinegar, H.; Smith, Y.R. End-of-Life Lithium-Ion Battery Component Mechanical Liberation and Separation. JOM 2019, 71, 4447–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C.; Kaas, A.; Peuker, U.A. Influence of the Cell Type on Yield and Composition of Black Mass Deriving from a Mechanical Recycling Process of Automotive Lithium-Ion Batteries. Next Sustain. 2024, 4, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankemeyer, S.; Wiens, D.; Wiese, T.; Raatz, A.; Kara, S. Investigation of the Potential for an Automated Disassembly Process of BEV Batteries. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concentrations of the fractions obtained by mechanical pre-treatment (%, in mass) | |||||||

| n > 9.5 mm | 4.75 < n < 9.5 mm | 2 < n < 4.75 mm | 1 < n < 2 mm | 0.5 < n < 1 mm | n < 0.5 mm | ||

| ROC | 37.8 ± 5.6 | 12.2 ±0.6 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 9.8 ± 1.6 | 22.3 ± 1.6 | 39.2 ± 1.8 | |

| Al | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 21.1 ± 1.4 | 11.3 ± 1.4 | 11.7 ± 1.4 | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | |

| Co | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 1.3 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | |

| Cu | 6.4 ± 1.1 | 15.2 ± 10.6 | 17.5 ± 2.3 | 23.4 ± 2.4 | 7.7 ± 1.8 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | |

| Fe | 23.7 ± 1.7 | 47.9 ± 5.4 | 17.1 ± 2.6 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | |

| Li | < LD | < LD | 1.9 ±0.3 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | |

| Mn | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 1.4 | 8.8 ± 1.8 | |

| Ni | 6.1 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 16.4 ± 1.2 | 15.1 ± 1.5 | 16.7 ± 1.7 | 22.7 ± 1.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).