Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results & Discussion

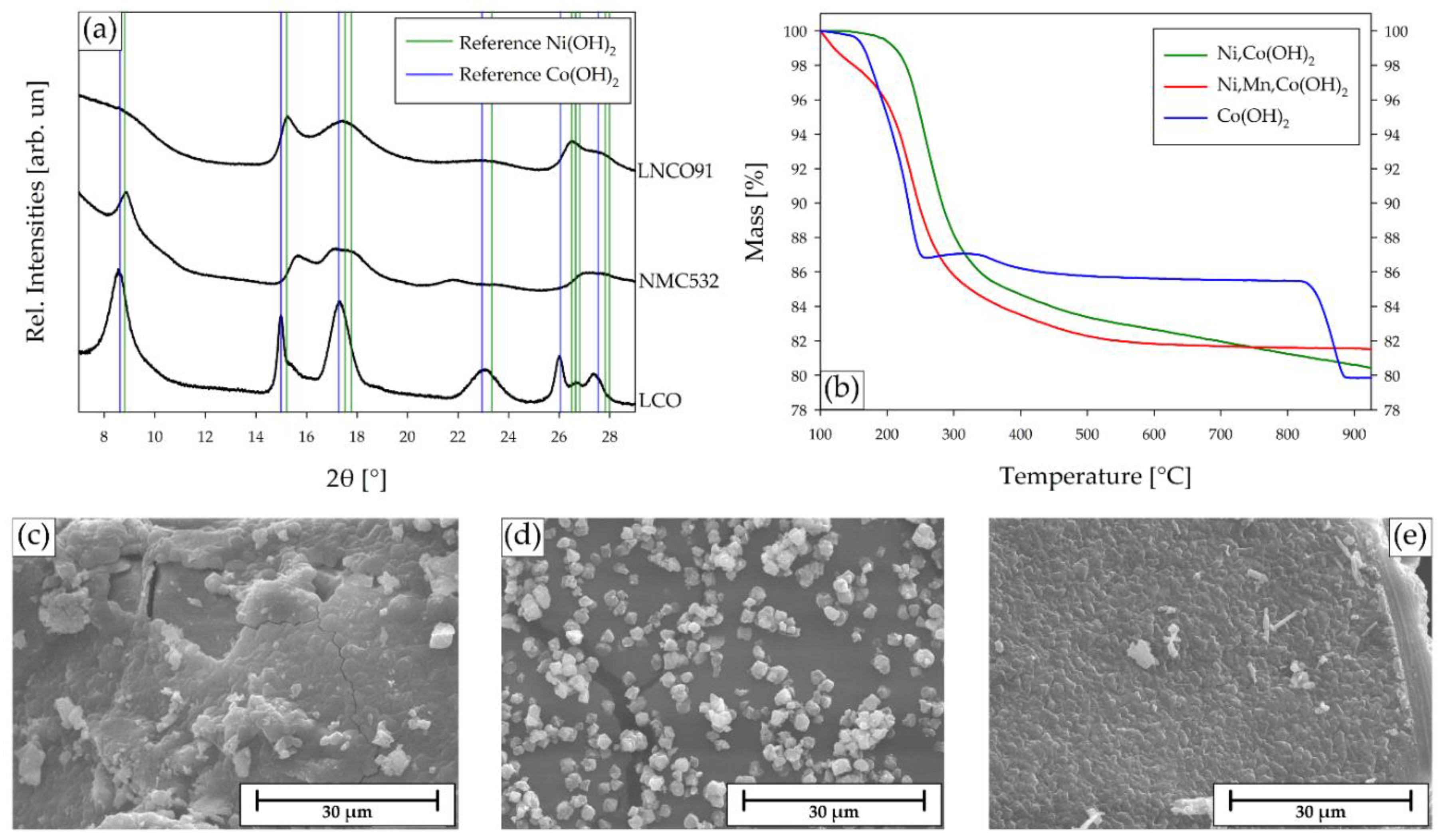

2.1. Spent Cathodes Identification

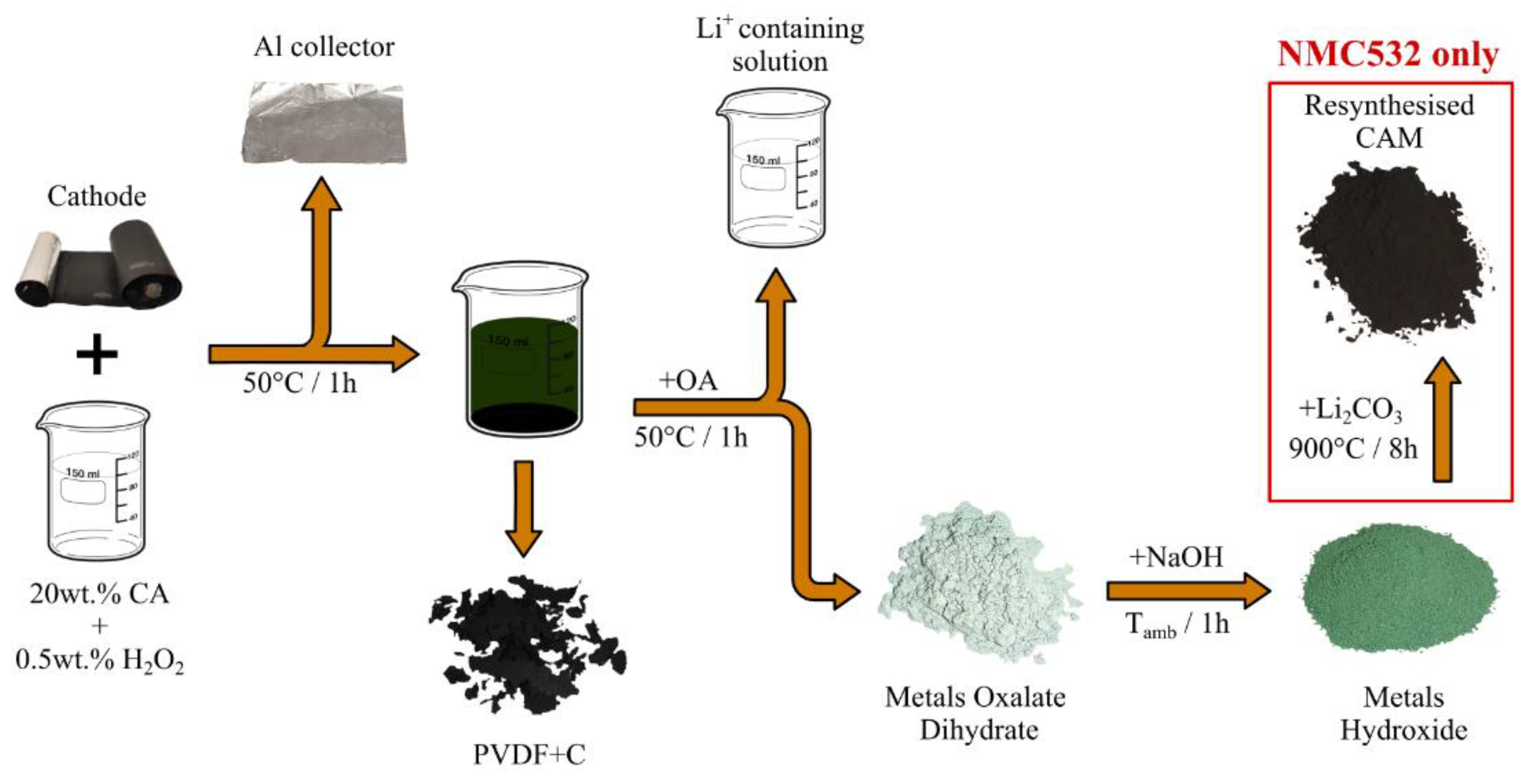

2.2. The Recycling Process

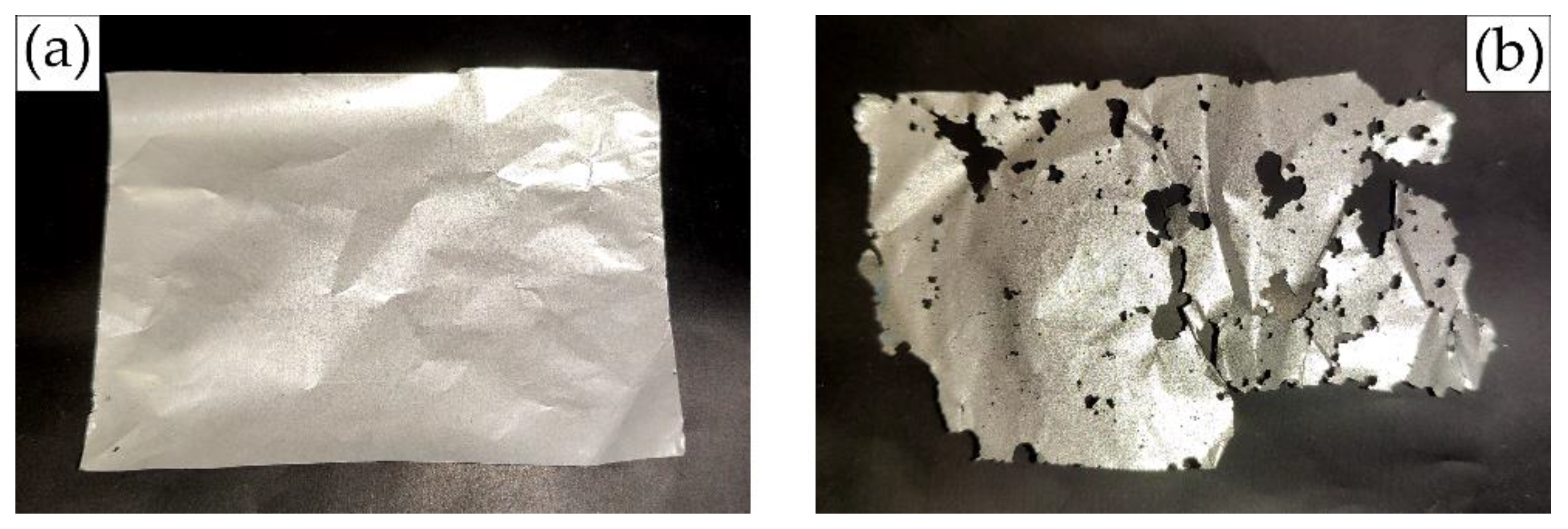

2.3. Delamination & Leaching

2.4. PVDF+C Mixture

2.5. Precipitation of the CAM Precursors

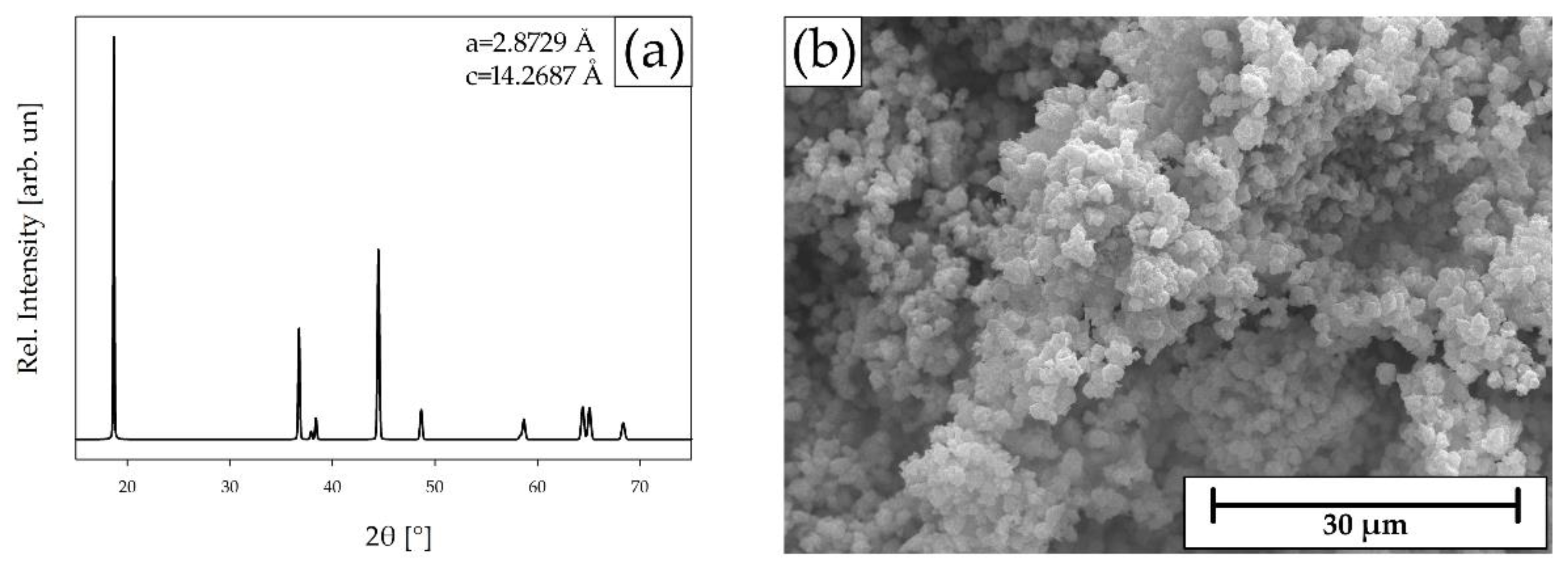

2.6. Resynthesis of the NMC532 CAM from the Recovered Precursors

3. Materials & Methods

3.1. Deactivation & Disassembling

3.2. Recycling Process

3.3. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interests

References

- Zion Market Research. Lithium-Ion Battery Market Size, Share by Type, by Industry, and By Region - Global And Regional Industry Overview, Market Intelligence, Comprehensive Analysis, Historical Data, And Forecasts 2022-2028; ZMR-2165; 2022.

- Facts & Factors. Lithium-Ion Battery Market Size, Share, Growth Analysis Report by Application, by Type, by Capacity, and by Region - Global and Regional Industry Insights, Overview, Comprehensive Analysis, Trends, Statistical Research, Market Intelligence, Historical Data and Forecast 2022-2030; FAF-2228; 2022.

- Grand View Research. Lithium-Ion Battery Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Product, by Application, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2024-2030; GVR-1-68038-601-1; 2024. grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/lithium-ion-battery-market.

- Global Market Insights. Lithium-Ion Battery Market Size - by Chemistry, Component, Application & Forecast, 2024-2032; GMI1135; 2024. gminsights.com/industry-analysis/lithium-ion-battery-market.

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1252 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024 Establishing a Framework for Ensuring a Secure and Sustainable Supply of Critical Raw Materials and Amending Regulations (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020. Official Journal of the European Union. May 3, 2024. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1252/oj (accessed 2024-05-29).

- Mrozik, W.; Rajaeifar, M. A.; Heidrich, O.; Christensen, P. Environmental Impacts, Pollution Sources and Pathways of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 6099–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G. D. J.; Kendrick, E.; Anderson, P. A.; Mrozik, W.; Christensen, P.; Lambert, S.; Greenwood, D.; Das, P. K.; Ahmeid, M.; Milojevic, Z.; Du, W.; Brett, D. J. L.; Shearing, P. R.; Rastegarpanah, A.; Stolkin, R.; Sommerville, R.; Zorin, A.; Durham, J. L.; Abbott, A. P.; Thompson, D.; Browning, N. D.; Mehdi, B. L.; Bahri, M.; Schanider-Tontini, F.; Nicholls, D.; Stallmeister, C.; Friedrich, B.; Sommerfeld, M.; Driscoll, L. L.; Jarvis, A.; Giles, E. C.; Slater, P. R.; Echavarri-Bravo, V.; Maddalena, G.; Horsfall, L. E.; Gaines, L.; Dai, Q.; Jethwa, S. J.; Lipson, A. L.; Leeke, G. A.; Cowell, T.; Farthing, J. G.; Mariani, G.; Smith, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Golmohammadzadeh, R.; Sweeney, L.; Goodship, V.; Li, Z.; Edge, J.; Lander, L.; Nguyen, V. T.; Elliot, R. J. R.; Heidrich, O.; Slattery, M.; Reed, D.; Ahuja, J.; Cavoski, A.; Lee, R.; Driscoll, E.; Baker, J.; Littlewood, P.; Styles, I.; Mahanty, S.; Boons, F. Roadmap for a Sustainable Circular Economy in Lithium-Ion and Future Battery Technologies. J. Phys. Energy 2023, 5, 021501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Solving Spent Lithium-Ion Battery Problems in China: Opportunities and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslow, K. M.; Laux, S. J.; Townsend, T. G. A Review on the Growing Concern and Potential Management Strategies of Waste Lithium-Ion Batteries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; Ruffo, R.; Quartarone, E.; Mustarelli, P. Circular Economy and the Fate of Lithium Batteries: Second Life and Recycling. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Bang, J.; Yoo, J.; Shin, Y.; Bae, J.; Jeong, J.; Kim, K.; Dong, P.; Kwon, K. A Comprehensive Review on the Pretreatment Process in Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colledani, M.; Gentilini, L.; Mossali, E.; Picone, N. A Novel Mechanical Pre-Treatment Process-Chain for the Recycling of Li-Ion Batteries. CIRP Ann. 2023, 72, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woeste, R.; Drude, E.-S.; Vrucak, D.; Klöckner, K.; Rombach, E.; Letmathe, P.; Friedrich, B. A Techno-Economic Assessment of Two Recycling Processes for Black Mass from End-of-Life Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Hyde, C.; Hartley, J. M.; Abbott, A. P.; Anderson, P. A.; Harper, G. D. J. To Shred or Not to Shred: A Comparative Techno-Economic Assessment of Lithium Ion Battery Hydrometallurgical Recycling Retaining Value and Improving Circularity in LIB Supply Chains. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Meng, Q.; Dong, P.; Zhang, Y. The Latest Research on the Pre-Treatment and Recovery Methods of Spent Lithium-Ion Battery Cathode Material. Ionics 2024, 30, 623–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.-P.; Sun, S.-Y.; Song, X.-F.; Yu, J.-G. Recovery of Cathode Materials and Al from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries by Ultrasonic Cleaning. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw-Stewart, J.; Alvarez-Reguera, A.; Greszta, A.; Marco, J.; Masood, M.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E. Aqueous Solution Discharge of Cylindrical Lithium-Ion Cells. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2019, 22, e00110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E.; Driscoll, L.; Slater, P.; Stolkin, R.; Walton, A.; Christensen, P.; Heidrich, O.; Lambert, S.; Abbott, A.; Ryder, K.; Gaines, L.; Anderson, P. Recycling Lithium-Ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles. Nature 2019, 575, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanisch, C.; Loellhoeffel, T.; Diekmann, J.; Markley, K. J.; Haselrieder, W.; Kwade, A. Recycling of Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Novel Method to Separate Coating and Foil of Electrodes. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.-P.; Sun, S.-Y.; Song, X.-F.; Yu, J.-G. Leaching Process for Recovering Valuable Metals from the LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 Cathode of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Jafvert, C. T.; Zyaykina, N. N.; Zhao, F. Decomposition of PVDF to Delaminate Cathode Materials from End-of-Life Lithium-Ion Battery Cathodes. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Muralidharan, N.; Li, J.; Essehli, R.; Belharouak, I. Sustainable Direct Recycling of Lithium-Ion Batteries via Solvent Recovery of Electrode Materials. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 5664–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Hawley, W. B.; Jafta, C. J.; Muralidharan, N.; Polzin, B. J.; Belharouak, I. Sustainable Recycling of Cathode Scraps via Cyrene-Based Separation. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2020, 25, e00202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B. B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J. M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B. W.; Gurkan, B.; Maginn, E. J.; Ragauskas, A.; Dadmun, M.; Zawodzinski, T. A.; Baker, G. A.; Tuckerman, M. E.; Savinell, R. F.; Sangoro, J. R. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Tan, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, J. A Low-Toxicity and High-Efficiency Deep Eutectic Solvent for the Separation of Aluminum Foil and Cathode Materials from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 380, 120846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Jafvert, C. T.; Zhao, F. Degradation of Cathode in Air and Its Influences on Direct Recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives, 2008.

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste, 2018.

- Makuza, B.; Tian, Q.; Guo, X.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Yu, D. Pyrometallurgical Options for Recycling Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Comprehensive Review. J. Power Sources 2021, 491, 229622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Hoseyni, S. M.; Cordiner, J. Safety Considerations for Hydrometallurgical Metal Recovery from Lithium-ion Batteries. Process Saf. Prog. 2024, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmohammadzadeh, R.; Faraji, F.; Rashchi, F. Recovery of Lithium and Cobalt from Spent Lithium Ion Batteries (LIBs) Using Organic Acids as Leaching Reagents: A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larba, R.; Boukerche, I.; Alane, N.; Habbache, N.; Djerad, S.; Tifouti, L. Citric Acid as an Alternative Lixiviant for Zinc Oxide Dissolution. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 134–135, 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dunn, J. B.; Zhang, X. X.; Gaines, L.; Chen, R. J.; Wu, F.; Amine, K. Recovery of Metals from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries with Organic Acids as Leaching Reagents and Environmental Assessment. J. Power Sources 2013, 233, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musariri, B.; Akdogan, G.; Dorfling, C.; Bradshaw, S. Evaluating Organic Acids as Alternative Leaching Reagents for Metal Recovery from Lithium Ion Batteries. Miner. Eng. 2019, 137, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.; Jung, Y.; Jo, M.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Yang, D.; Rhee, K.; An, E.-M.; Sohn, J.; Kwon, K. Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Battery Cathode Materials by Ammoniacal Leaching. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 313, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J. J.; Cao, B.; Madhavi, S. A Review on the Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries (LIBs) by the Bioleaching Approach. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 130944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, P.; Callegari, D.; Merli, D.; Tealdi, C.; Vadivel, D.; Milanese, C.; Kapelyushko, V.; D’Aprile, F.; Quartarone, E. Sorting, Characterization, Environmentally Friendly Recycling, and Reuse of Components from End-of-Life 18650 Li Ion Batteries. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2023, 7, 2300161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, K.; Sugiyama, J.; Aoki, Y. Structural, Magnetic, and Electrochemical Studies on Lithium Insertion Materials LiNi1−xCoxO2 with 0≤x≤0. 25. J. Solid State Chem. 2010, 183(7), 1726–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xie, T.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Xu, M.; Wang, W.; Lai, Y.; Li, J. The Impact of Vanadium Substitution on the Structure and Electrochemical Performance of LiNi0. 5Co0.2Mn0.3O2. Electrochimica Acta 2014, 135, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummow, R.; Liles, D.; Thackeray, M.; David, W. A Reinvestigation of the Structures of Lithium-Cobalt-Oxides with Neutron-Diffraction Data. Mater. Res. Bull. 1993, 28(11), 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattarin, S.; Guerriero, P.; Musiani, M.; Tuissi, A.; Vázquez-Gómez, L. Electrochemical Etching of NiTi Alloy in a Neutral Fluoride Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2009, 156, C428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayilgan, E.; Kukrer, T.; Yigit, N. O.; Civelekoglu, G.; Kitis, M. Acidic Leaching and Precipitation of Zinc and Manganese from Spent Battery Powders Using Various Reductants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, T. Hydrometallurgical Process for the Recovery of Metal Values from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries in Citric Acid Media. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2014, 32, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, U.; Su, C.; Hocheng, H. Leaching of Metals from Large Pieces of Printed Circuit Boards Using Citric Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 24384–24392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, P. Use of Glucose as Reductant to Recover Co from Spent Lithium Ions Batteries. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerrillo-Gonzalez, M. D. M.; Paz-Garcia, J. M.; Muñoz-Espinosa, M.; Rodriguez-Maroto, J. M.; Villen-Guzman, M. Extraction and Selective Precipitation of Metal Ions from LiCoO2 Cathodes Using Citric Acid. J. Power Sources 2024, 592, 233870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyrieux, R.; Berro, C.; Peneloux, A. Contribution a l’étude Des Oxalates de Certains Métaux Bivalents. III. Structure Cristalline Des Oxalates Dihydratés de Manganèse, de Cobalt, de Nickel et de Zinc. Polymorphisme Des Oxalates Dihydratés de Cobalt et de Nickel. Bull. Société Chim. Fr. 1973, 25–34.

- Hall, D. S.; Lockwood, D. J.; Bock, C.; MacDougall, B. R. Nickel Hydroxides and Related Materials: A Review of Their Structures, Synthesis and Properties. Proc. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 471, 20140792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, C.; Tessier, C. Stacking Faults in the Structure of Nickel Hydroxide: A Rationale of Its High Electrochemical Activity. J. Mater. Chem. 1997, 7, 1439–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, M.; Ghaemi, M.; Sabour, B.; Dalvand, S. Electrochemical Preparation of Alpha-Ni(OH)2 Ultrafine Nanoparticles for High-Performance Supercapacitors. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2014, 18, 1569–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Matsuki, K.; Sugawara, M.; Endo, T. Pyrolysis of gamma-Manganese Hydroxide Oxide. Nippon Kagaku Kaishi 1973, 9, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzade, H.; Khayati, G. R.; Schaffie, M. Preparation and Kinetic Modeling of Beta-Co(OH)2 Nanoplates Thermal Decomposition Obtained from Spent Li-Ion Batteries. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 2779–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metal molar content | Sample name | ||||

| Ni | Mn | Co | Li | ||

| Cell #1 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.94 | LNCO91 |

| Cell #2 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.83 | NMC532 |

| Cell #3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | LCO |

| Sample | Crystal system | SG (no.) | a [Å] | b [Å] | c [Å] | β [°] |

| (Ni0.9Co0.1)C2O4 ∙ 2H2O | Monoclinic | C2/c (15) | 11.7927 | 5.3231 | 9.7454 | 126.8160 |

| (Ni0.5Mn0.3Co0.2)C2O4 ∙ 2H2O | Monoclinic | C2/c (15) | 11.9229 | 5.4360 | 9.8012 | 127.140 |

| CoC2O4 ∙ 2H2O | Monoclinic | C2/c (15) | 11.8516 | 5.4248 | 9.7568 | 126.933 |

| Starting CAM | Product | Element fractions | ||

| Ni | Mn | Co | ||

| LNCO91 | (Ni0.90Co0.10)C2O4 ∙ 2H2O | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| (Ni0.90Co0.10)(OH)2 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.10 | |

| NMC532 | (Ni0.49Mn0.31Co0.20)C2O4 ∙ 2H2O | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.20 |

| (Ni0.51Mn0.29Co0.20)(OH)2 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.20 | |

| LCO | CoC2O4 ∙ 2H2O | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Co(OH)2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).