1. Introduction

Motivation.

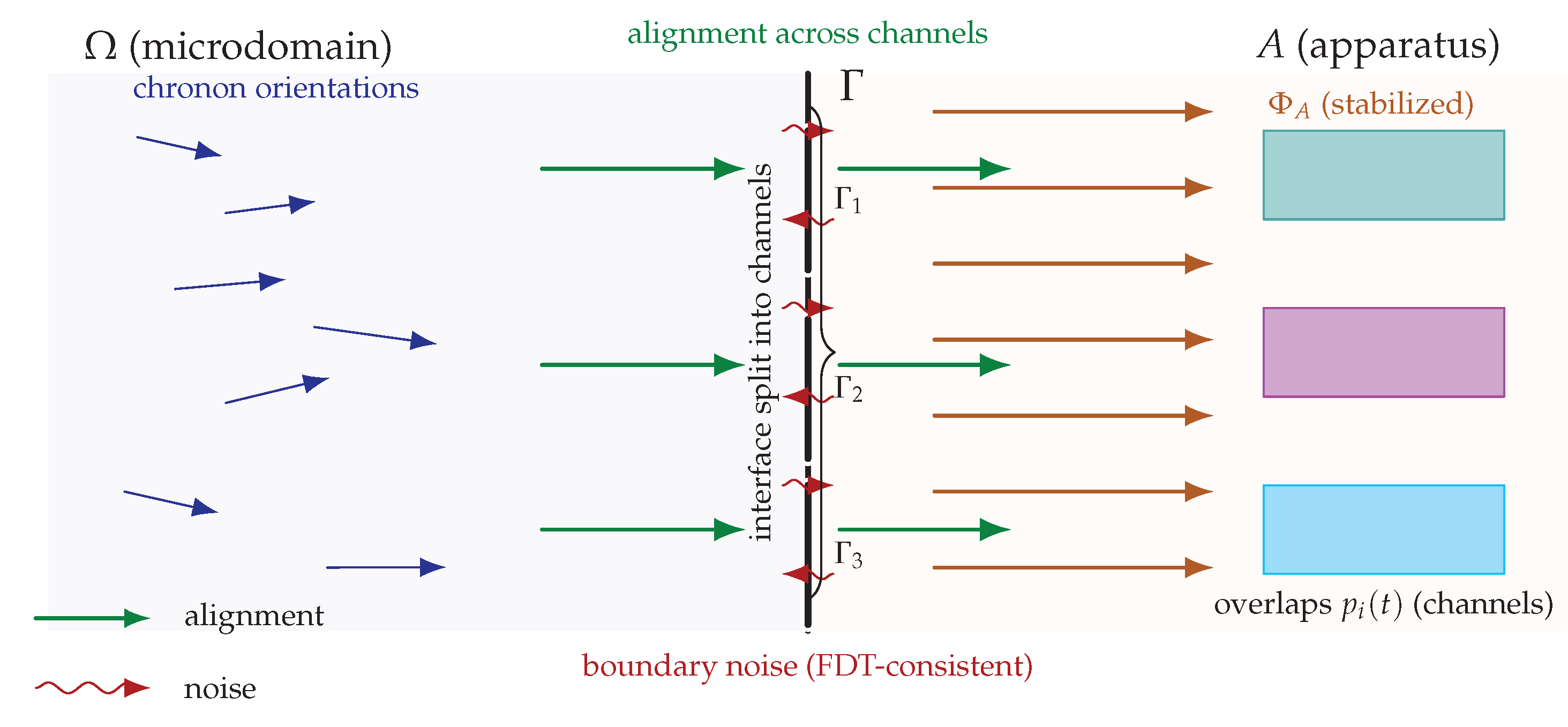

Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) models quantum measurement as

boundary–induced alignment, in which a microscopic chronon domain

with weakly correlated orientations couples across an interface

to a macroscopic apparatus region

whose coarse–grained field

is stabilized (future–directed, unit–norm, twist–free). This coupling drives the domain’s effective field

into alignment with one of a finite set of apparatus eigen–domains, yielding a definite outcome without invoking nonlocal collapse. Prior work established that the Lorentzian, unit–norm phase is both exclusive and selected by measurement within apparatus regions, and showed that this phase emerges dynamically from a global unit–norm constraint on the chronon field in flat configuration space, thereby grounding causal structure and temporal asymmetry in the intrinsic geometry of the field space [

63]. A key remaining challenge, and the focus of this paper, is to derive the

Born rule—the quadratic dependence of outcome probabilities on initial amplitudes—from chronon dynamics alone, without introducing additional probabilistic axioms.

Conceptual mechanism.

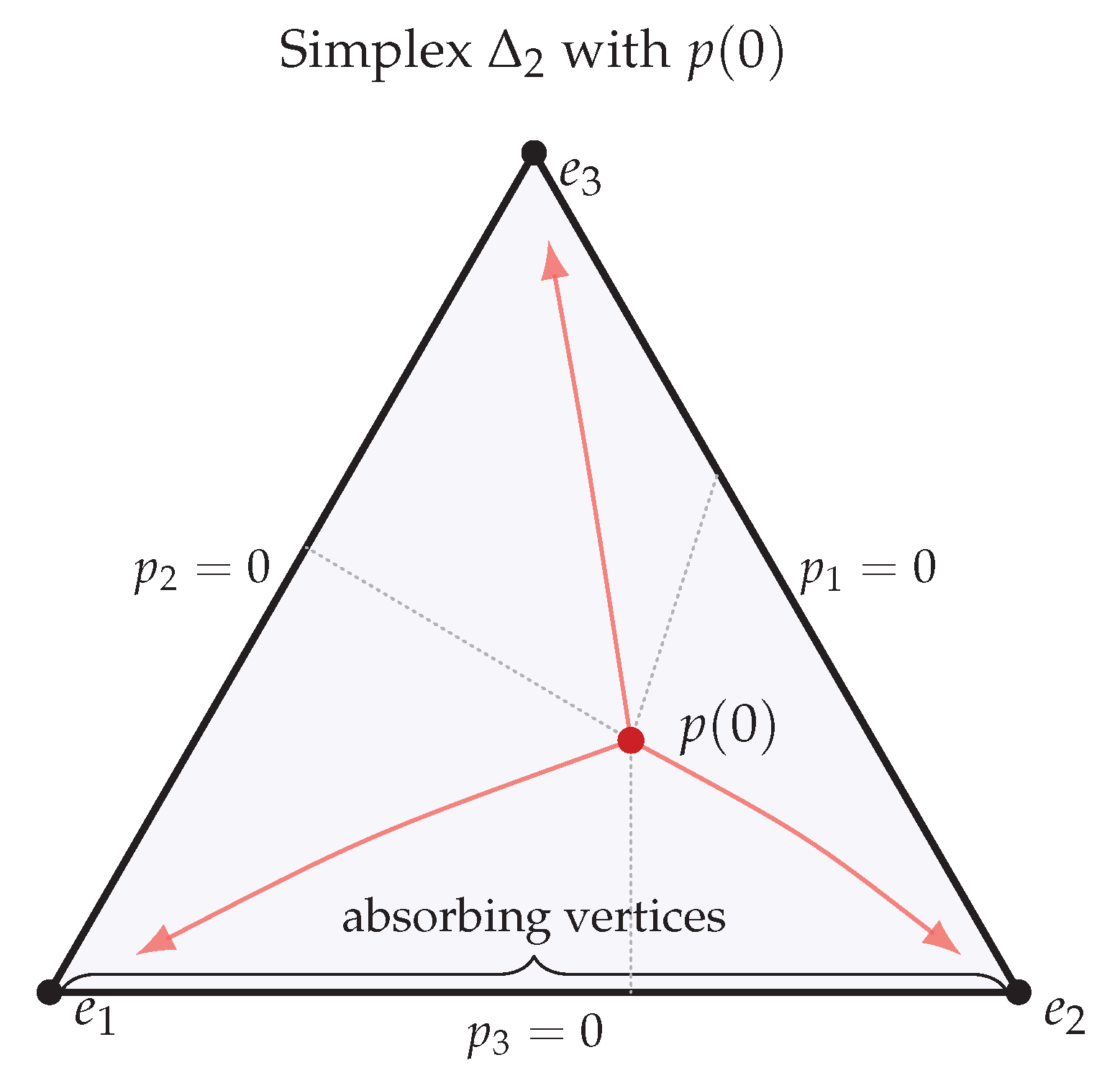

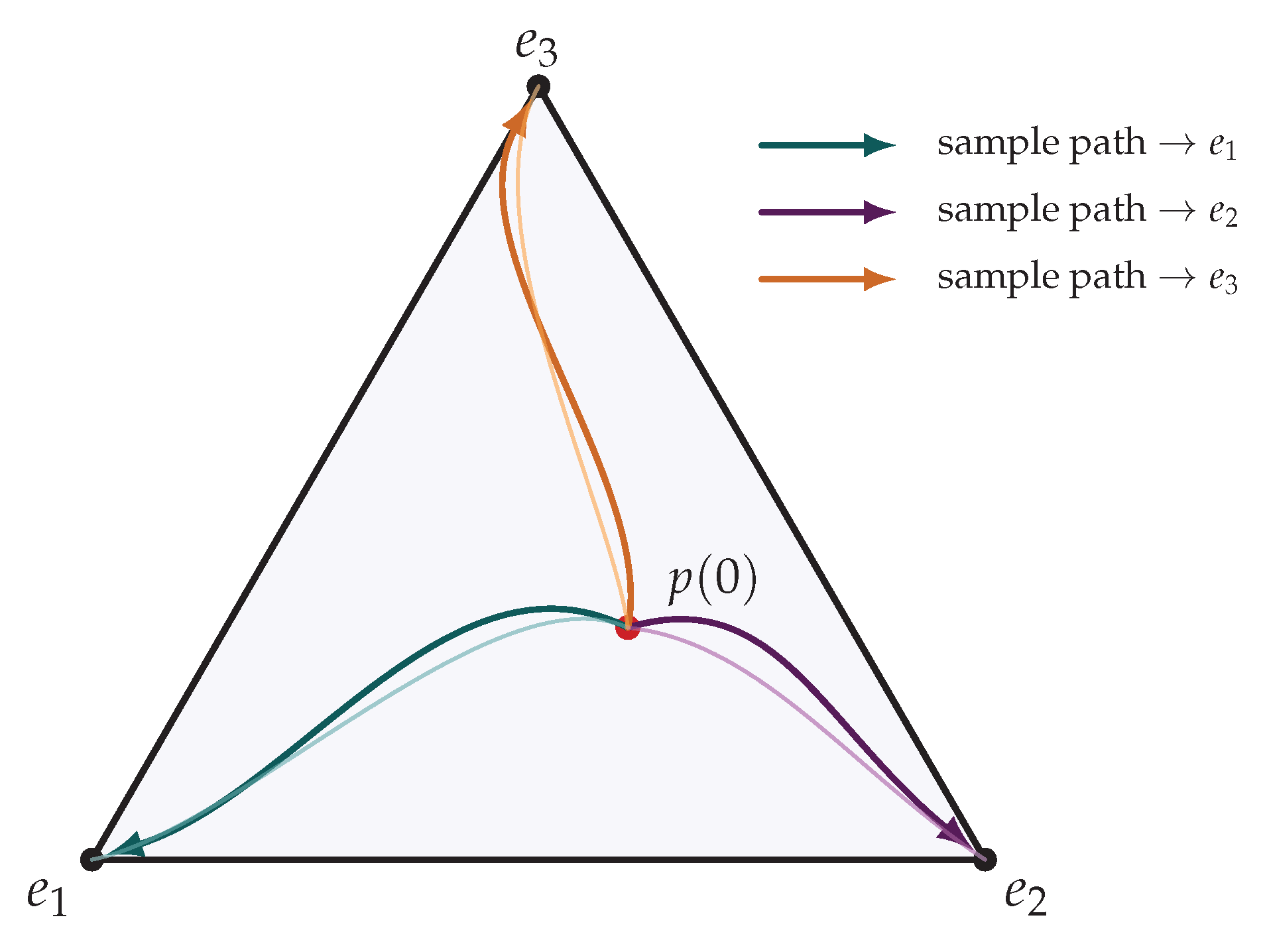

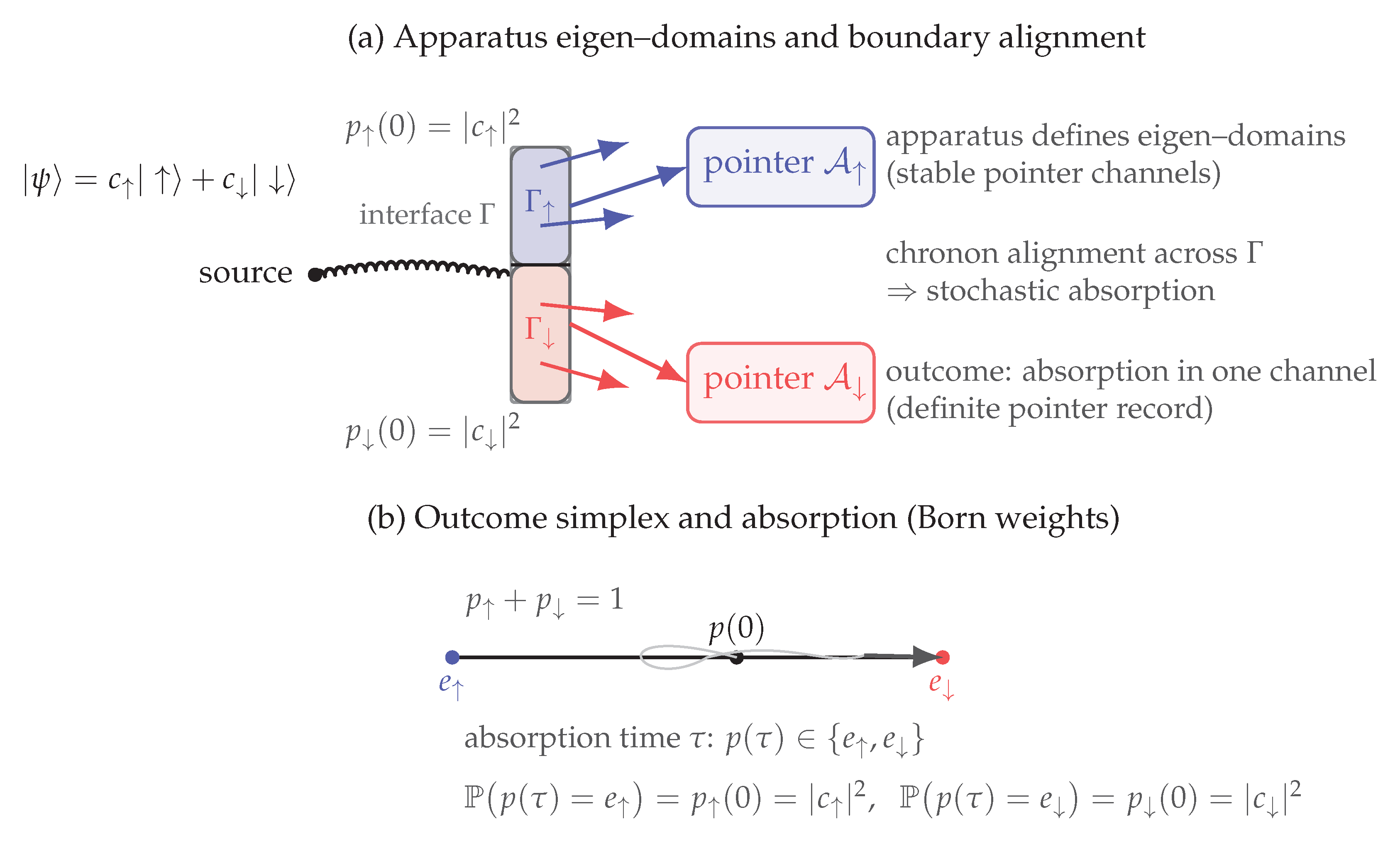

At the core of CFT is a field-theoretic model of quantum measurement in which outcome selection emerges from alignment geometry at the apparatus boundary. The apparatus defines a finite set of stabilized pointer configurations—the eigen–domains—with which the chronon field of the microscopic system can stochastically align. This alignment is local and continuous in spacetime, but due to coarse–graining and boundary coupling, the dynamics becomes probabilistic and irreversible on macroscopic scales. The outcome simplex encodes the overlaps between the evolving chronon field and these eigen–domains, and absorption into a vertex corresponds to a definite measurement result. Conceptually, this means that measurement is not a collapse of the system into one of its own eigenstates, but absorption of the system field into apparatus eigen–domains that are engineered to correspond to the system’s eigenbasis. This does not contradict the standard textbook view, but reframes it: the apparatus, rather than the system, selects the effective measurement basis, yielding both outcome definiteness and Born weights from physical chronon dynamics without postulates.

Objective.

This paper provides an operational and rigorous derivation of the

Born rule in the CFT measurement setting under explicit, verifiable assumptions on the apparatus, interface, and noise. That is, given a system prepared in state

and an observable with eigenstates

, the probability of obtaining outcome

is

We treat the

alignment overlaps with apparatus eigen–domains as order parameters,

collectively forming a process on the outcome simplex

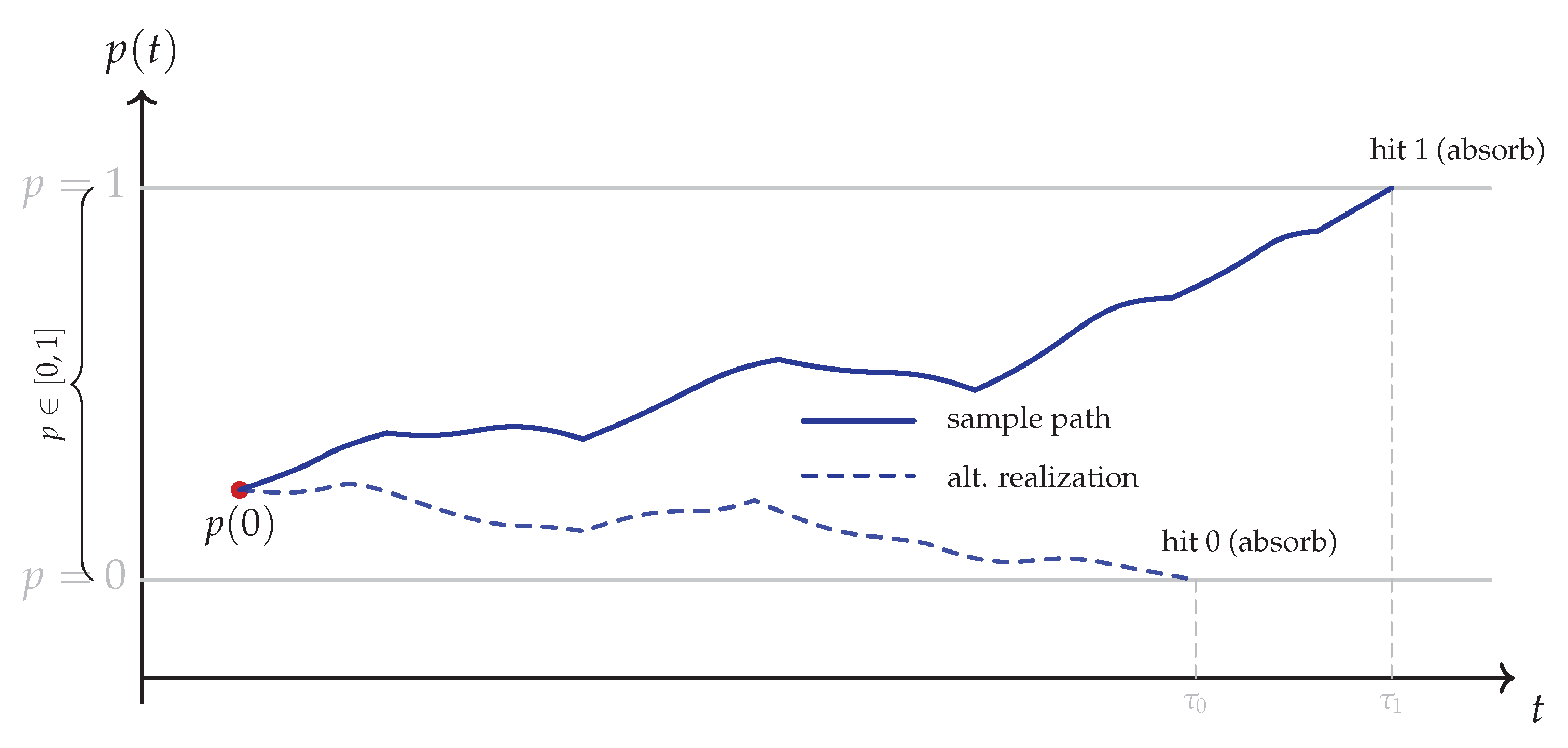

. Our main results establish that, under boundary–consistent noise and detailed balance at the interface, (i) the coarse–grained chronon dynamics yields a diffusion limit for

on

with absorbing vertices, (ii) the coordinates

are martingales up to the absorption time, and therefore (iii) single–shot absorption probabilities equal the initial overlaps

, i.e., the Born weights. We then obtain a large–deviation principle (LDP) for empirical outcome frequencies in repeated trials, with rate function minimized at the Born vector.

Contributions.

In this paper we prove the following:

Geometric mechanism for outcome selection. We model measurement as stochastic field alignment with a finite family of apparatus eigen–domains, yielding definite outcomes via absorption in the outcome simplex without invoking collapse.

Simplex diffusion (Theorem 3.1). Starting from a noisy gradient–flow model for with boundary coupling to (consistent with a Gibbs noise model at inverse temperature and interface strength ), we derive, under mild regularity and symmetry assumptions, a diffusion limit for the projected overlap process on with absorbing vertices . The limiting generator has continuous, Lipschitz coefficients and preserves the simplex.

Martingale structure and Born probabilities (Proposition 17, Theorem 4.1). We show that detailed balance at the interface enforces

zero drift for each coordinate:

. Hence

is a (uniformly integrable) martingale up to the absorption time

at the simplex vertices. By optional stopping, the absorption probabilities satisfy

yielding the Born rule when

are the initial overlaps with the apparatus eigen–domains.

Collapse as absorption (Section 5). We interpret the selection of a definite measurement outcome as stochastic

absorption of the alignment overlap vector

at a simplex vertex. This dynamical mechanism replaces the conventional wavefunction collapse postulate with a local, continuous, and probabilistic alignment process, reconciling definiteness of outcomes with causal and reversible dynamics.

Hydrodynamic grounding (Theorem 6.1). We justify the diffusion approximation by proving tightness of the projected processes under chronon microdynamics, identifying the limit via the martingale problem [

31], and computing the covariance from boundary fluctuations through a fluctuation–dissipation relation.

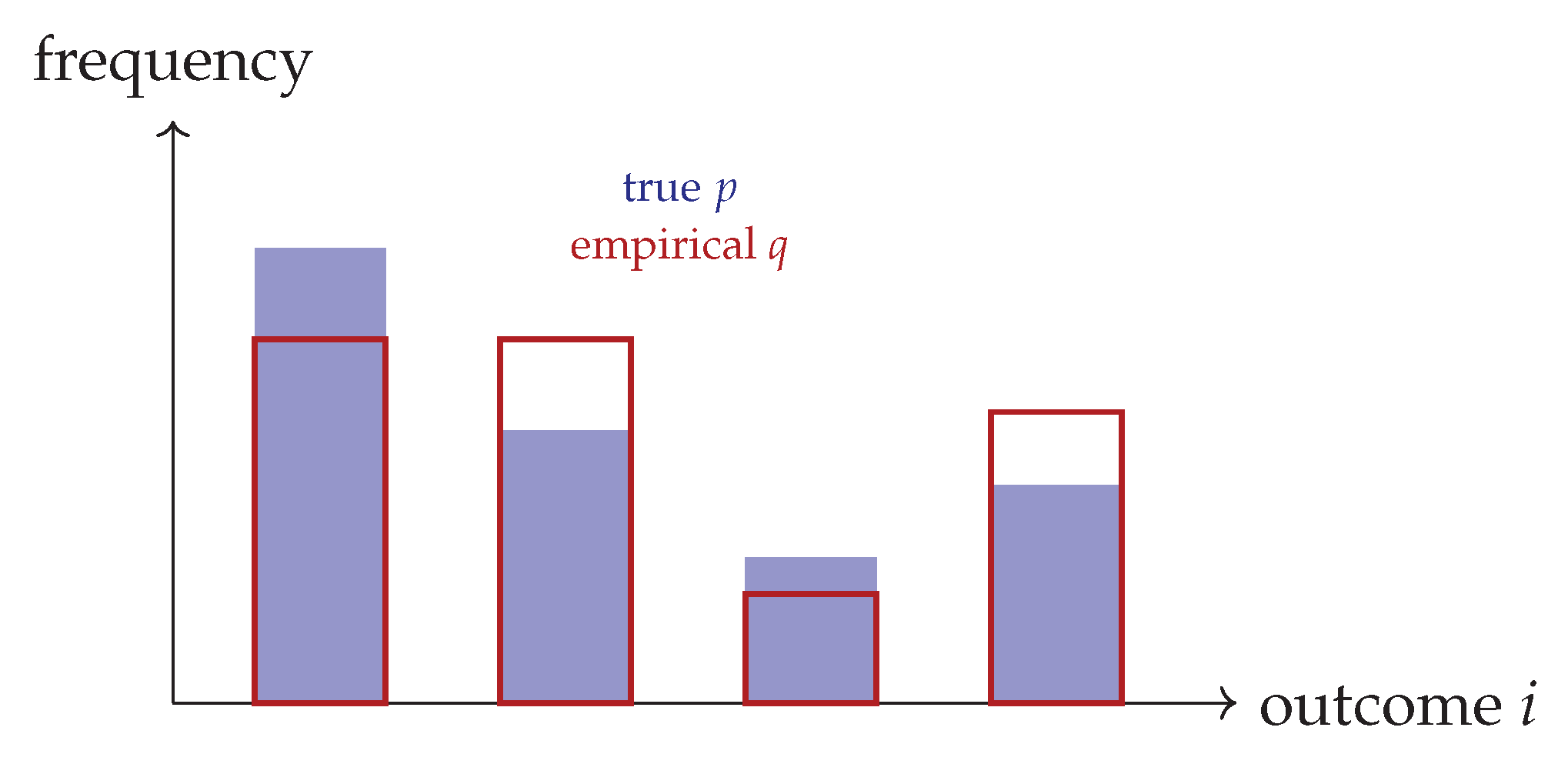

Frequency large deviations (Theorem 7.1). For repeated measurements prepared with identical initial overlaps, we obtain a Sanov–type LDP for empirical frequencies

with good rate function

minimized uniquely at

[

19].

Robustness bounds (Theorem 8.1). We quantify deviations from Born weights under imperfect interfaces (finite ), finite temperature , and small symmetry–breaking drifts, obtaining explicit perturbative error bounds of the form

Relation to prior work.

Conceptually, our derivation parallels the martingale structure underlying stochastic Schrödinger equations and quantum trajectories [

3,

94], but differs in two essential ways: (i) the stochasticity arises from

classical chronon fluctuations at the apparatus boundary within CFT’s emergent causal geometry, rather than from postulated stochastic modifications to Schrödinger evolution; (ii) the simplex diffusion and its zero–drift property are derived from interface detailed balance and symmetry of the alignment energy, not imposed.

Compared to objective collapse models [

6,

39], our approach does not introduce new dynamical laws or coupling constants. Relative to purely epistemic accounts [

13,

84], outcome probabilities here emerge from physical stochastic absorption in the alignment geometry, not knowledge updates. Decoherence-based arguments [

99] suppress interference but do not yield definite outcomes or derive Born weights; our model addresses both via the absorbing boundary structure of the outcome simplex.

Finally, unlike decision-theoretic derivations in Everettian settings [

20,

91], or subjectivist reconstructions such as QBism [

34], the present framework grounds the Born rule in a local, emergent field theory with classical causal structure and no branching or agent-centric assumptions. The absorption law is tied directly to macroscopic alignment geometry and fluctuations, offering a new class of explanation distinct from stochastic mechanics [

69] or gravitational collapse models [

21,

76].

Structure of the paper.

Section 2 formalizes the operational setting: apparatus eigen–domains, alignment overlaps, admissible noise, and observer axioms.

Section 3 derives the limiting diffusion on the outcome simplex and states the required regularity and symmetry assumptions.

Section 4 proves the martingale property and derives single–shot Born probabilities by optional stopping, including hitting and integrability lemmas.

Section 6 provides the hydrodynamic limit from chronon microdynamics, establishing tightness and identifying the limiting generator and covariance via boundary fluctuation–dissipation.

Section 7 proves the frequency LDP for repeated trials and sketches an alternative thermodynamic LDP via constrained free energies.

Section 8 gives quantitative stability bounds and extensions to degeneracies and POVMs.

Section 9 outlines experimental and numerical signatures. We conclude with a discussion of open problems and future directions.

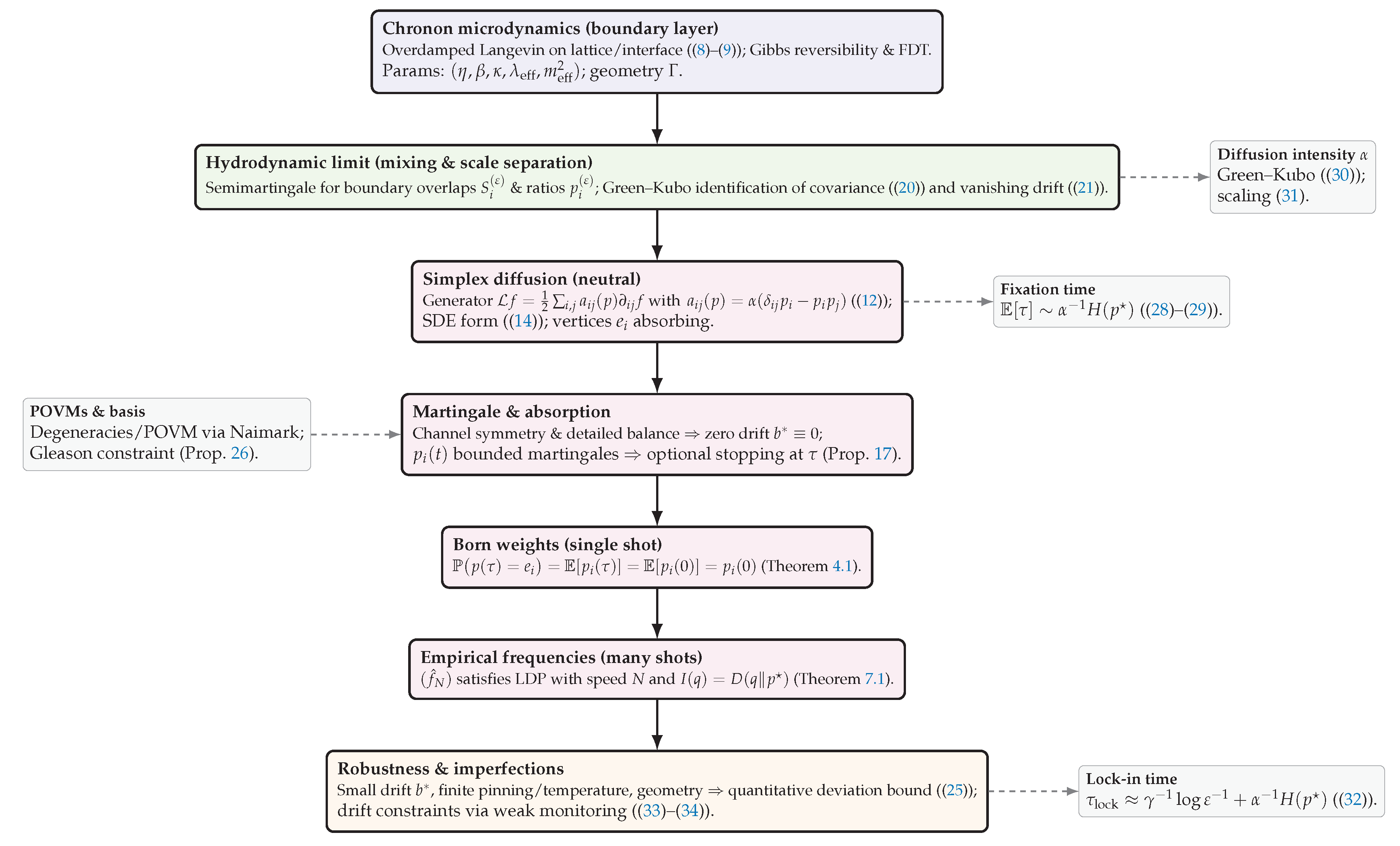

To orient the reader,

Figure 1 summarizes the logical pipeline/flowchart of our derivation. The starting point is the chronon dynamics in the apparatus boundary layer, modeled as a reversible noisy alignment process. Under suitable mixing and time–scale separation, these microscopic dynamics converge to an effective diffusion for the overlap vector on the outcome simplex. This diffusion is neutral and martingale–valued, so that absorption at the simplex vertices yields outcome probabilities equal to the initial overlaps—precisely the Born rule. At the level of repeated trials, empirical frequencies concentrate at the Born vector according to a large–deviation principle, providing a statistical law of large numbers with exponential accuracy. Finally, realistic imperfections such as finite coupling, temperature, or geometric asymmetry enter only as small drift or covariance corrections, for which quantitative stability bounds are available. In this way the figure provides a schematic overview, connecting microscopic chronon alignment to the emergence and robustness of Born statistics.

For Non-specialists. Because some of our arguments draw on techniques from probability theory, statistical physics, and information theory, we provide a self-contained pedagogical appendix for non-specialist readers. There we review the essential background on martingales and optional stopping, Wright–Fisher diffusions on the simplex, and large deviations via relative entropy and Sanov’s theorem, together with simple examples and diagrams. Readers familiar with these standard tools may skip the appendix.

2. Operational Setup and Measurement Geometry

2.1. Apparatus Eigen–Domains and Alignment Observables

We formalize the macroscopic apparatus, its stabilized alignment field, the measurement interface, and the outcome observables that will generate a process on the outcome simplex.

Definition 1 (Stabilized apparatus domain). An

apparatus domain is an open, connected subset

equipped with a smooth, future–directed, unit–norm timelike vector field

that is

twist–free in

:

Consequently, there exists a smooth proper–time function

on

whose level sets

are spacelike hypersurfaces orthogonal to

. We call

the

apparatus foliation.

Remark 2 (Emergent causal structure from chronon constraints).

The apparatus field

induces the local causal structure and time direction in

by defining a unit–norm, twist–free timelike flow. This structure is not imposed arbitrarily: in a companion analysis [

63], it is shown that such Lorentzian signature arises naturally from a unit–norm constraint on the chronon field

over a flat background configuration space. There, the kinetic term in the effective action, constrained to preserve unit norm, selects a hyperbolic geometry with a distinguished timelike direction—providing a geometric foundation for the causal alignment process assumed in the present derivation. (See

Appendix L for a justification of the eigen–domain structure.)

Definition 3 (Measurement interface and channels). Let be the (mesoscopic) microdomain prepared for measurement, and let be the spacelike measurement interface on a fixed apparatus leaf . Denote by the induced Riemannian metric on and by its volume form.

A family of

channels is a measurable partition

with each

of positive

–measure. Define

, so that

We refer to

(or

) as the

apparatus eigen–domains (resp. an

orthonormal channel basis).

Remark 4 (Geometry and physical meaning).

The field

fixes the local time direction and causal geometry in

(Def. 1). The partition

encodes distinct, macroscopically disjoint pointer channels (e.g. separate detector pixels or paths) on the interface where the microdomain first couples to the apparatus. Orthogonality is in the

function space , not in Minkowski space; distinct channels are disjoint in space, which is the operational origin of outcome exclusivity [

98].

Remark 5 (Channel symmetry and standard QM).

In the present framework, we assume symmetry of the apparatus eigen–domains, so that no outcome channel is intrinsically favored beyond the system’s own overlaps. This assumption is not an additional hypothesis, but rather the field–theoretic restatement of what is already built into the standard measurement postulate: projective measurements treat all eigenstates of a given observable on equal footing, and more generally POVMs require , ensuring completeness and unbiasedness of the outcome channels. In textbook quantum mechanics this symmetry is taken as axiomatic, whereas here it is realized dynamically through the geometry and stochastic alignment of the apparatus domains.

Definition 6 (Alignment scalar and alignment observable)

. Let

be the coarse–grained chronon field in a neighbourhood of

. Define the

local alignment scalar on

by

which satisfies

whenever both

and

are unit–norm, future–directed timelike fields. Let

be a fixed

strictly increasing function (e.g.

). The

channel strengths are

Definition 7 (Alignment overlaps and outcome simplex). Provided

, define the

alignment overlaps (or

overlap vector)

Then

takes values in the outcome simplex

Lemma 8

(Normalization, positivity, and continuity).

Under the hypotheses of Definitions 1–7, the map is well–defined on the set where and satisfies:

- 1.

and .

- 2.

If on Γ, then , , and hence

- 3.

If Φ varies in in a neighbourhood of Γ, then depends continuously on Φ with respect to the –topology (equivalently, continuously in via the trace), provided f is with bounded derivative on bounded sets [9,32].

Remark 9 (Choice of f and invariance).

Any strictly increasing

f yields the same

ordering of channel strengths and, after normalization, the same

up to a continuous, strictly order–preserving reparametrization of the pre–normalized scores. The choice

is convenient analytically (smooth, convex) and physically interpretable as a quadratic energy gain from alignment [

37].

Remark 10 (Single–point vs. spatially averaged overlaps).

The

channel basis

(Def. 3) implements a spatial coarse–graining of the local alignment scalar over each channel

. This averaging is essential for robustness and for the hydrodynamic limit: it ensures that

is insensitive to microscopic fluctuations below the interface scale and provides Lipschitz continuity of the overlaps with respect to

in trace norms, which will be used in

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 4 and

Section 6 [

85].

Dynamics notation.

In

Section 3 and

Section 4 we write

for the

time–dependent overlaps induced by the (noisy) alignment dynamics of

near

. By Lemma 8,

for all times prior to absorption at a channel, and

will be shown to evolve as a diffusion on

with absorbing vertices under suitable assumptions.

2.2. Observer Axioms and Admissible Dynamics

We recall the operational axioms that constrain physically realizable observers and specify the admissible stochastic dynamics for the alignment process at the measurement interface. The axioms ensure causal consistency at the macroscopic level; the dynamics below is an effective description of boundary–driven relaxation in the apparatus and will be shown to imply a diffusion limit for the alignment overlaps on the outcome simplex.

Definition 11 (Observer axioms). An observer is a macroscopic open system supported in a stabilized apparatus domain (Definition 1) whose operation satisfies:

- (O1)

Well–posed local dynamics. The physical degrees of freedom (matter + fields) obey local second–order PDEs admitting a well–posed Cauchy problem on spacelike slices

of the apparatus foliation [

47].

- (O2)

Finite–speed signalling. There exists a cone structure compatible with such that disturbances from compactly supported initial data propagate inside the corresponding domains of dependence.

- (O3)

Acyclic causal order. The causal precedence relation on is irreflexive and transitive; no closed causal loops exist in the operational regime.

- (O4)

Records and stability. There exist subsystems of finite spatial extent whose internal macrostates encode outcomes and remain metastable for times

, the microscopic relaxation scale [

51,

97].

Interface parameters.

We fix an apparatus leaf

and a spacelike interface

(Definition 3) with orthonormal channel basis

. Two control parameters enter the interface model:

The coupling

quantifies the energetic penalty for misalignment between

and

on

; the temperature

parameterizes thermal fluctuations of the chronon degrees of freedom in the boundary layer.

Effective alignment functional.

On a neighbourhood

U of

we consider the coarse–grained functional (bulk + boundary)

with

,

,

(ordered phase).

Definition 12 (Admissible alignment dynamics). An admissible dynamics for near is either of the following two classes:

(H) Hyperbolic (causal) stochastic dynamics. A damped stochastic wave equation on

U,

with

, where

is a space–time Gaussian field of zero mean, white in time and smooth at spatial scale

(the boundary microscopic scale), and

is a positive self–adjoint mobility operator on

U. Boundary condition on

:

with outward normal

n, Gaussian boundary noise

(white in time, smooth on

), and positive self–adjoint boundary mobility

.

(P) Overdamped (gradient–flow) stochastic dynamics. An

–gradient flow on

U,

with boundary condition

where

and

are positive self–adjoint mobilities (bulk and boundary).

Assumption 13 (Detailed balance and fluctuation–dissipation)

. In either class (H) or (P), the bulk and boundary mobilities

are chosen so that the Markov semigroup of the process is

reversible with respect to the Gibbs measure

i.e. detailed balance holds:

where

is the generator. Equivalently, the noise covariances satisfy the fluctuation–dissipation relation with the same mobilities that define the drift

(class P) or the damping operators (class H).

Assumption 14 (Well–posedness and locality)

. For class (H), the deterministic part of (

2) is strictly hyperbolic with finite propagation speed in

; the stochastic forcing

has compact spatial correlation support of diameter

, ensuring that for any

the influence of data outside the domain of dependence is exponentially suppressed. For class (P), the dynamics (

4) is the overdamped limit of (H) on timescales

; it is confined to a thin tubular neighbourhood of

of thickness

and cannot be used operationally for signalling outside

. In both cases, for initial data

there exists a unique (probabilistically strong) solution with continuous paths in

on finite time intervals.

Remark 15 (Compatibility with observer axioms).

Axioms (O1)–(O3) apply to the macroscopic propagation of matter and information in . Class (H) respects finite–speed propagation at the level of alignment dynamics. Class (P) is an effective, strongly damped limit describing local relaxation of inside the apparatus boundary layer; since it is confined to U and reversible w.r.t. , it does not generate superluminal signalling or causal anomalies at the operational level. Axiom (O4) is ensured by the existence and uniqueness of the minimizer of in the apparatus (stability of records), as established in the measurement selection results.

Consequence for overlaps.

Under Assumptions 13–14, the process

(Definition 7) is a Markov process on

whose drift is determined by the

–reversible dynamics. In

Section 3 we prove that, after a diffusive rescaling and projection,

converges to a diffusion with absorbing vertices and, by detailed balance, has

zero drift along each coordinate—yielding the martingale structure central to our Born–rule derivation.

3. From Noisy Alignment Dynamics to a Simplex Diffusion

3.1. Noisy Gradient Flow for with Boundary Coupling

We work with the overdamped (gradient–flow) class (P) from Definition 12, in the spirit of stochastic gradient flows for SPDEs [

17]. Let

U be a tubular neighbourhood of the interface

. The coarse–grained alignment functional is

with

,

,

fixed.

The stochastic alignment dynamics is the

gradient flow of

with Gibbs–consistent noise (Assumption 13), consistent with the fluctuation–dissipation framework for SPDEs [

45,

86]:

where

W is a cylindrical Wiener process on

with covariance trace–class at spatial scale

,

B is a boundary Wiener process on

with trace–class covariance, and

,

are positive self–adjoint mobilities. By Assumption 14, for any

, (

8)–(9) has a unique strong solution with continuous

–paths on finite times [

17].

Let

be the trace operator. Recall the

alignment overlaps (Def. 7) built from the local scalar

and a fixed strictly increasing

:

Set

.

To compute the stochastic evolution of

we use Itô’s formula for functionals of infinite–dimensional diffusions [

17]. If

is twice Fréchet differentiable with appropriate growth and trace–class noise, then

We apply

and then the quotient rule

with

. The derivatives

and

act via the chain rule on

restricted to

, yielding local multipliers proportional to

and

.

3.2. Projected Order Parameters and Limiting SDE

The resulting evolution for

can be written as

where

,

are the coordinates of

W and

B in orthonormal bases, and

,

,

are obtained from

,

, the mobilities, and the trace. By Assumption 13, the quadratic variation of

p is governed by the reversible Dirichlet form of

;

is induced by the deterministic part of (

8)–(9) plus the Itô correction.

We now perform a

diffusive rescaling that averages out fast boundary fluctuations in the alignment layer, following standard diffusion-approximation theory [

31]. Fix a scale parameter

and define

Under time–scale separation (fast relaxation of

at fixed

p) and mixing in the boundary layer, weak convergence of

to a Markov diffusion

p on

holds with generator

where the effective covariance

and drift

are obtained by fluctuation-averaging [

73]. Permutation symmetry of channels and invariance under rigid motions preserving

imply that

has the

Wright–Fisher form [

31,

33]

where

is a scalar

boundary diffusion intensity. Detailed balance at the interface enforces

zero effective drift [

86]:

Finally, the absorbing condition at faces

follows from standard boundary classification for absorbing Wright–Fisher diffusions [

33].

A canonical SDE representation of (

11)–(

12) is

where

is a matrix of independent standard Brownian motions. The form (

14) is a standard Wright–Fisher diffusion representation [

31,

33]; it preserves the simplex constraint

and ensures

almost surely.

Assumption 16 (Regularity and symmetry). We assume:

- (R1)

(

Local Lipschitz & non–explosion) The coefficients in (

10) are locally Lipschitz in

in a tubular neighbourhood of the alignment manifold and have at most linear growth; solutions remain in a compact subset of

with high probability on bounded times [

17].

- (R2)

(

Boundary mixing & time–scale separation) The alignment layer near

is rapidly mixing on time scale

; conditional on

p, the fast variables are ergodic with a unique reversible measure induced by

, and their autocovariances are integrable, consistent with homogenization theory [

73].

- (R3)

(Channel symmetry) The geometry and noise are invariant under permutations of and under isometries of that preserve ; f is fixed once and for all.

- (R4)

(

Absorbing vertices) If

for some

i, then the limiting dynamics leaves

p at

almost surely, in analogy with absorbing boundaries in Wright–Fisher diffusions [

33].

Under (R1)–(R4), the diffusion limit exists, is unique in law, has generator (

11) with

a as in (

12) and

, and takes values in

with absorbing vertices

[

31].

Theorem 3.1 (Diffusion limit on the outcome simplex).

Let be the rescaled overlap process associated with (8)–(9). Suppose Assumptions 13, 14, and 16 hold. Then, as , the laws of on are tight and converge weakly to the unique solution of the martingale problem for the generator in (11) with covariance (12) and zero drift (13), subject to absorbing boundary condition at the vertices [31,86]. Equivalently, where p solves (14) on with absorption at .

Proof sketch. Tightness follows from Aldous’ criterion [

1] using (R1) and uniform moment bounds derived from the reversible Dirichlet form. Identification of the limit uses the martingale problem framework [

31,

86]: for smooth

f,

is a martingale, where

is computed from (

10). Under (R2),

with covariance (

12) obtained by Green–Kubo formulas for boundary fluctuations [

42], and under detailed balance (Assumption 13) the effective drift vanishes. Absorption (R4) is inherited by the limit. Uniqueness in law for (

14) with degenerate diffusion on

is standard [

31,

33]. □

4. Martingale Structure and Absorption Probabilities

4.1. Zero–Drift Structure from Detailed Balance

For the limiting diffusion of Theorem 3.1, detailed balance at the interface (Assumption 13), together with channel symmetry (R3), implies

in (

11). Intuitively, in the neutral (symmetric) alignment landscape the apparatus does not bias transitions between channels; the stochastic fluctuations are balanced and purely diffusive on

[

31].

Proposition 17 (Martingale property). Let be the –valued diffusion of Theorem 3.1. Then for each , is a bounded martingale with respect to the natural filtration up to the absorption time . In particular, for all .

Proof. With generator (

11) and

, we have for the linear coordinate

that

for all

and hence

Thus

is a local martingale [

86]. Since

, it is bounded and therefore a true martingale. Stopping at

preserves the martingale property. □

4.2. Optional Stopping and Born Weights

Let denote the ith vertex of (the pure ith channel). Define as above.

Theorem 4.1 (Single–shot Born probabilities)

. Assume the hypotheses of Theorem 3.1 and Proposition 17. Then If the microdomain is prepared with initial overlaps relative to the apparatus eigen–domains, the absorption probabilities equal the Born weights .

Proof sketch. By Proposition 17,

is a bounded martingale, hence uniformly integrable; Doob’s optional stopping theorem [

26,

28] gives

. Since

,

, so

. □

See Appendix N for the full proof.

4.3. Hitting, Non-Explosion, and Boundary Behavior

Lemma 18 (Almost sure absorption and integrability of

)

. For the Wright–Fisher diffusion (14) (equivalently, generator (11) with (12)) on with zero drift and no mutation, the process is absorbed at a vertex in finite time almost surely: . Moreover, .

Proof sketch. In the neutral Wright–Fisher diffusion with

m types and no mutation, standard boundary classification shows that the boundary

is attainable and absorbing [

31,

33]. Successive extinction of types occurs until fixation at a vertex. Lyapunov functions of the form

satisfy

away from vertices, implying that

V is a strict supermartingale and giving finiteness of

by Foster–Lyapunov criteria [

66]. See Appendix M for details. □

Consequence.

Lemmas 18 and Proposition 17 justify optional stopping in Theorem 4.1 and complete the single–shot Born–rule derivation under the chronon alignment dynamics. See Appendix N for the full proof.

5. Collapse, Definiteness, and the Outcome Simplex

In standard quantum mechanics, the measurement problem centers on how a quantum system, initially described by a coherent superposition, yields a single, definite outcome upon observation. The traditional response is the

wavefunction collapse postulate, an explicit discontinuous update to the system’s state conditioned on measurement [

90]. This section interprets how Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) resolves this issue dynamically, by replacing postulated collapse with stochastic absorption in the outcome simplex.

5.1. Collapse as Stochastic Absorption

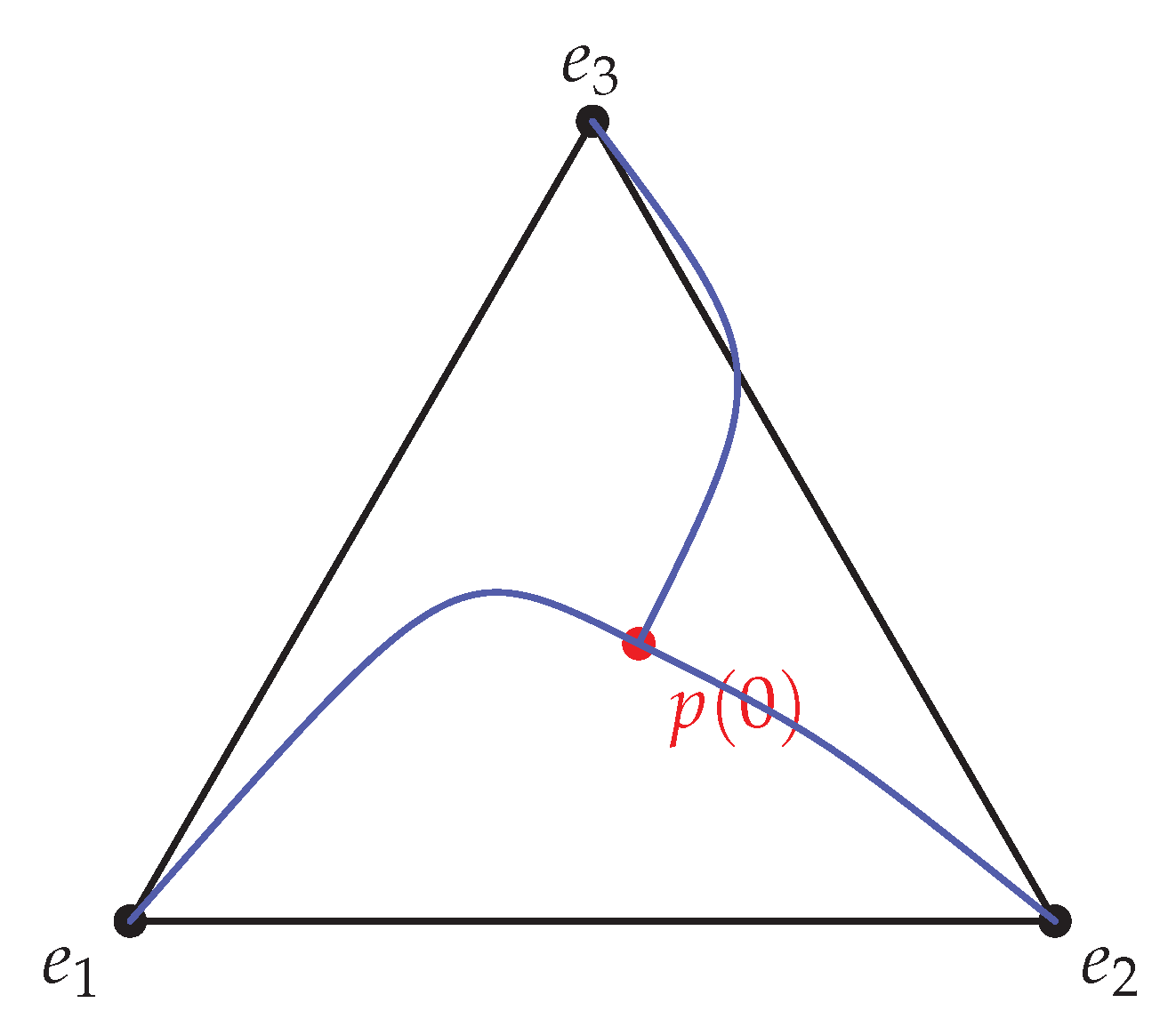

Let denote the time-dependent overlap vector encoding the alignment of the chronon field with the m apparatus eigen–domains (Definition 7). As shown in Proposition 17, each coordinate is a bounded martingale under the interface-coupled chronon dynamics, and the process is absorbed almost surely at one of the simplex vertices in finite time (Lemma 18).

This absorption event corresponds to a physical measurement outcome. Specifically, absorption at

implies that channel

i dominates the alignment, i.e.,

The field configuration

becomes fully aligned with the

ith apparatus eigen–domain, and this alignment is macroscopically stable due to the properties of the stabilized apparatus region

(Definition 1). Thus, the measurement produces a definite, classically recordable outcome without the need to invoke discontinuous projection or nonlocal effects.

5.2. Comparison to Conventional Collapse

This absorption-based mechanism fulfills the empirical role of wavefunction collapse but arises here as an emergent property of local, reversible, and stochastic dynamics at the boundary layer:

The outcome is definite due to absorption: the system eventually enters a simplex vertex state , excluding all other outcomes.

The process is probabilistic via martingale properties: the absorption probabilities are given by the initial overlaps , reproducing the Born rule (Theorem 4.1).

The dynamics is

local and continuous in spacetime: all stochasticity originates from chronon fluctuations at the measurement interface

, governed by reversible SPDEs (

Section 3).

In contrast to standard collapse models (e.g., GRW [

39]), no additional dynamics or modification of Schrödinger evolution is introduced. Unlike purely epistemic views [

46,

84], the stochasticity arises from an objectively fluctuating alignment process. Compared to quantum trajectory or stochastic Schrödinger frameworks [

5,

22,

40], the present derivation ties the martingale and absorption structure to coarse–grained, classical field interactions, rather than postulating stochasticity at the level of the wavefunction.

5.3. System Eigenstates versus Apparatus Eigen–Domains

In the textbook formulation of quantum measurement, a system initially prepared in a superposition

of eigenstates

of some observable

O is said to “collapse” into one of these eigenstates upon measurement, with Born probability

. The apparatus is then taken to record this outcome by correlating its pointer state

with the corresponding eigenstate of the system.

Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) reformulates this picture. In CFT, the apparatus is not a passive recorder but an active dynamical system that defines a finite set of stable, coarse–grained alignment channels, or

eigen–domains. The chronon field of the microscopic system couples to these domains across the measurement interface

, and its effective alignment process is described by the overlap vector

. As shown in

Section 5, the overlaps undergo a martingale diffusion and are absorbed almost surely at a simplex vertex

, corresponding to one of the apparatus eigen–domains. In this sense, the measurement outcome is realized as

absorption of the system’s chronon field into a pre–existing apparatus channel, rather than collapse of the system into its own eigenstate.

The two perspectives are consistent once the apparatus is designed so that its eigen–domains are engineered to correspond to the eigenbasis of the measured observable. For example, in a Stern–Gerlach experiment the apparatus field geometry implements two stable alignment domains corresponding to “spin up” and “spin down” along the chosen axis. What the textbook account describes as collapse of the spin state into or is, in CFT, realized dynamically as absorption of the chronon alignment into one of the two apparatus domains. The Born probabilities arise from the initial overlaps and the martingale absorption law.

This reframing highlights a key conceptual advance: in CFT the apparatus, not the system, determines the measurement basis. The eigen–domains are stabilized features of the macroscopic apparatus field, and the system’s stochastic alignment with them yields both definiteness and Born weights. Thus, CFT explains dynamically why a particular set of outcomes is available at all, while reproducing the standard quantum prediction that the system is “found in an eigenstate” of the chosen observable.

5.4. Definiteness Without Projection

The key insight is that outcome definiteness is dynamically encoded in the

absorbing boundary structure of the outcome simplex

. Once the process reaches a vertex

, it remains there with probability one, reflecting irreversible alignment with a single apparatus domain. This yields a natural resolution of the measurement problem within CFT:

Collapse is thus reinterpreted as an emergent, irreversible flow toward absorbing states in the geometry of alignment overlaps, replacing the postulated discontinuity of traditional interpretations.

5.5. Interpretational Implications

This reinterpretation of collapse as absorption supports several key principles:

- 1.

Locality: All causal influences are confined to the measurement interface and its neighborhood.

- 2.

No superluminal effects: Alignment propagation respects the apparatus foliation and causal structure induced by .

- 3.

Objective definiteness: The selection of an outcome is a physical stochastic process with classical records encoded in macroscopic apparatus channels.

- 4.

No auxiliary postulates: The Born rule and outcome definiteness follow directly from the chronon field dynamics and interface coupling.

In this way, CFT offers a conceptually and mathematically coherent resolution of the collapse problem by grounding it in physically well-defined stochastic geometry.

6. Hydrodynamic Limit from Chronon Microdynamics

6.1. Microscopic Model, Scaling, and Tightness

We resolve the diffusion limit of

Section 3 directly from the microscopic chronon dynamics in a boundary layer around the interface

. Let

be the microscopic spacing and let

be the coarse–graining scale. For a small parameter

we consider a family of discretizations with

and a fixed physical interface

covered by a

boundary layer.

Let be the set of lattice sites, and let denote boundary sites (one layer thick) identified with via nearest–point projection. Channels are discrete partitions refining the continuum .

Microscopic stochastic dynamics.

At each

we have a microscopic chronon vector

. The stochastic dynamics is the overdamped Langevin system consistent with the discrete version of the alignment functional (7), in the spirit of interacting particle systems with Gibbs stationary measures [

85]:

where

is the discrete energy plus a boundary penalty

Here

are independent standard Brownian motions in

, and · is the Minkowski inner product. The unique invariant measure is the discrete Gibbs measure

by detailed balance [

55].

6.1.0.13. Block averages and overlap observables.

On mesoscopic blocks

(diameter

) define

, and interpolate to a field

. The discrete alignment scalar on a boundary site

is

and the discrete channel strengths and overlaps are

with weights

approximating the surface element on

. By Lemma 8 (trace continuity),

approximates the continuum

as

.

Semimartingale decomposition.

Applying Itô to (

17) and using (

15)–(16), each

admits the decomposition

where

is a martingale and

is the compensator (drift). Quadratic covariations satisfy

A ratio Itô calculation yields a semimartingale form for

with drift

and covariance

built from

and

[

55,

88].

Assumption 19 (Mixing and propagation of chaos). There exist constants independent of such that:

- (C1)

(

Uniform spectral gap / mixing) The generator of (

15)–(16) restricted to

has spectral gap

, and time autocorrelations of local observables

supported in balls of radius

decay as

, as ensured by Poincaré/log–Sobolev inequalities for reversible lattice systems [

2,

49,

96].

- (C2)

(

Propagation of chaos across channels) For disjoint channel subsets

separated by

, the covariance of bounded Lipschitz observables

and

under the invariant measure is

, consistent with exponential decay of correlations in the Dobrushin uniqueness/cluster–expansion regime [

23,

24,

85].

- (C3)

(

Boundary fast scale) The relaxation/mixing times satisfy

under the diffusive rescaling

used below, as in standard hydrodynamic scaling for reversible particle systems [

55].

Theorem 6.1 (Tightness and identification of the limit).

Let be the diffusively rescaled overlap process constructed from (17). Assume regularity (Assumption 16), detailed balance at the boundary (Appendix P), well–posedness of the projected SDE (Appendix M), and mixing/chaos (Assumption 19). Then:

-

(i)

(Tightness

) The family is tight in for each by the Aldous–Rebolledo criterion for semimartingales [1,79,80].

-

(ii)

-

(Limit generator

) Any weak limit p solves the martingale problem on with generator

where the coefficients arise from fluctuation averaging/Green–Kubo formulas for reversible dynamics [31,42,56,73]:

-

(iii)

(Wright–Fisher form and zero drift

) By channel symmetry and reversibility, and [31,33,86].

Consequently, p is the Wright–Fisher diffusion on with absorbing vertices as in Theorem 3.1.

Proof sketch.

(i) Tightness: The semimartingale decomposition (

18) and the ratio Itô formula give

with predictable quadratic variation

. Under (C1)–(C3),

and

are uniformly controlled, so Aldous–Rebolledo tightness applies [

1,

79,

80].

(ii) Identification uses the martingale–problem method [

31]: for smooth

f,

is a martingale, where

is computed from

; mixing yields

in the Green–Kubo sense [

42,

56,

73].

(iii) Symmetry forces isotropy on the tangent space

, giving the Wright–Fisher covariance; reversibility (detailed balance) kills the averaged drift [

86]. Absorption follows because once a channel monopolizes the boundary weight, cross–channel fluctuation terms vanish. □

6.2. Boundary Layer and Coefficient Identification

We now express the limiting covariance intensity in terms of boundary fluctuations (FDT) and quantify drift cancellation and error rates.

Alignment currents and Green–Kubo formula.

Let

denote the stochastic time derivative of

in (

17). Define the (centered)

alignment currents

which are square–integrable martingale noises supported in the boundary layer. Then, under Assumption 19, a Green–Kubo representation of

is [

42,

56,

85]

where

. Channel symmetry reduces (

22) to a single scalar

.

Drift cancellation by detailed balance.

The raw drift

is the conditional expectation of

given

. Detailed balance and invariance under channel permutations imply

so

in the limit [

55,

86]. If small asymmetries (e.g.

areas not exactly equal or weak channel–dependent mobilities) are present, then

for a constant

C depending on geometry and regularity; thus the Born probabilities are stable to first order.

Rates and boundary thickness.

Let

be the spectral gap from (C1) and let

be the mixing time. Then for

and small

,

so convergence in law holds with an explicit qualitative rate provided

is bounded away from zero and

, reflecting spectral–gap/log–Sobolev control of relaxation [

2,

62]. The coefficient

scales linearly with the effective boundary mobility and inversely with the channel areas in the symmetric case,

up to dimensionless factors depending smoothly on

, in line with Green–Kubo/hydrodynamic scaling [

85].

Remark 20 (Absorbing faces in the microscopic model).

In the discrete dynamics, once (all boundary spins aligned to channel i so ) the coupling terms between distinct channels vanish and only intra–channel fluctuations remain, which preserve . This yields the absorbing vertices in the limit.

Remark 21 (Choice of f and universality of the limit).

The choice of the increasing function

f in (

17) affects microscopic weights

but not the limiting

normalized process

p: after normalization, the diffusion matrix must be tangent to the simplex and isotropic under channel permutations, forcing the Wright–Fisher form [

31,

33]. Hence the limiting law of

p is universal within the class of smooth strictly increasing

f.

7. Large Deviations for Empirical Frequencies

7.1. IID Repetition from Absorption Law

Fix an apparatus with channels

and initial overlap vector

for the prepared microdomain on the interface leaf

. Let

be the Wright–Fisher diffusion on

of Theorem 3.1 with zero drift and absorbing vertices

, started at

. Let

be the absorption time (finite a.s., Lemma 18), and define the outcome random variable

By Theorem 4.1,

(Born weights).

A trial is one prepare–evolve–absorb cycle followed by a reset of the apparatus boundary layer to its stationary macrostate and a fresh preparation with the same overlap . Let be the outcomes from such trials, and let be the number of repetitions.

Independence/mixing assumptions. We work under either:

- (A1)

IID trials. The apparatus reset fully decorrelates successive trials and the prepared microdomains are independent. Thus are i.i.d. with common law on .

- (A2)

-

Fast mixing trials. is strictly stationary and

–mixing with coefficients

satisfying

(e.g. summable

). The one–trial marginal is still

, ensuring applicability of mixing LDPs [

10,

18].

Define the empirical frequency vector

by

Theorem 7.1 (Sanov LDP for outcome frequencies)

. Let be generated by the absorption law with single–trial distribution . Then satisfies a large–deviation principle on with speed N and good, convex rate function

with the conventions and if for some i with . This holds under either:

-

(i)

IID case (A1):

classical Sanov theorem [19,82]; and iff .

-

(ii)

Mixing case (A2):

Sanov–type LDP with the same speed and rate I by LDP results for mixing sequences [10,18].

Consequently, for any closed and open ,

and almost surely, with exponentially small tail probabilities governed by I.

Proof sketch. (i) Under (A1), are i.i.d. with law , so Sanov’s theorem applies; on a finite alphabet the rate is .

(ii) Under (A2), level–2 LDPs for strictly stationary

–mixing sequences with sufficiently decaying mixing coefficients hold with the same Cramér transform as in the i.i.d. case [

10]. Since the single–trial SCGF remains

and block decoupling yields asymptotic additivity, Gärtner–Ellis [

19,

29] gives

. □

Remarks.

(1) A CLT holds:

with

under (A1) [

7], and with a long–range covariance correction under (A2) [

18]. (2) In the i.i.d. case, Chernoff–Hoeffding bounds [

48] follow from the LDP upper bound.

7.2. Alternative Thermodynamic LDP (Optional)

We sketch a thermodynamic derivation of the same rate function I via constrained free energies, avoiding explicit trial–wise independence. Consider N repetitions realized as N disjoint boundary windows (in time or space), each coupled to the same stabilized apparatus and prepared with the same . Let be the (finite–volume) boundary partition function for window k with alignment functional at inverse temperature . Write for the tilted partition function that weights each realization by .

Assumption 22 (Approximate factorization and exponential tightness). There exists such that, uniformly for on compacts,

- (F1)

(Free energy additivity) with .

- (F2)

(Exponential tightness) The family is exponentially tight under the –tilted Gibbs law.

These hold, e.g., if windows are separated by buffers so inter-window correlations are exponentially small, and if the one–window outcome law is by the single–trial martingale/absorption result.

Proposition 23 (Constrained free energy and rate function)

. Under Assumption 22, the sequence satisfies an LDP on with good rate

Proof sketch. By Varadhan’s lemma [

87] (or Gärtner–Ellis [

29]), the limiting SCGF is

. Its Legendre–Fenchel transform is

I, which equals

on

. Exponential tightness ensures a full LDP. □

Discussion.

The thermodynamic route shows that, beyond explicit i.i.d. repetitions, the large–deviation structure is controlled by the tilted boundary free energy, which is fixed by the single–trial law and approximate additivity. Both the stochastic (Sanov) and thermodynamic (Varadhan) derivations identify the same rate function minimized uniquely at the Born vector .

8. Robustness and Extensions

8.1. Imperfect Interfaces, Finite Temperature, and Small drifts

In realistic devices the interface coupling is finite (

), the boundary layer has nonzero temperature (

), and small asymmetries in channel geometry or mobility may be present. These effects can produce a small effective drift

in the limiting simplex dynamics (

Section 3), in addition to (i) a bias in the initial overlaps

due to imperfect preparation and (ii) small deviations of the diffusion matrix from the symmetric Wright–Fisher form

[

31,

33]. We quantify the impact on absorption probabilities.

Notation.

Let

be the zero–drift Wright–Fisher generator with intensity

(Theorem 3.1). Let

be the perturbed generator. For each vertex

, denote by

the absorption probability for

, i.e.

interpreted in the weak sense appropriate for degenerate operators at the boundary [

30,

31]. For the unperturbed process,

.

Define small parameters

Here

measures drift strength relative to diffusion;

and

control norm pinning and thermal roughness at the boundary;

captures channel area asymmetry (for

; any fixed strictly increasing

f gives an equivalent measure).

Theorem 8.1 (Quantitative stability of Born weights)

. Assume the hypotheses of Theorem 3.1 and the hydrodynamic limit (Theorem 6.1) with small symmetry breaking so that is continuous and , and the diffusion matrix satisfies

Then there exists such that, for every initial overlap ,

where are the ideal overlaps computed with perfect pinning and symmetric channels. In particular, when (ideal preparation), the absorption probabilities deviate from Born weights by at most the right–hand side of (25).

Proof sketch. Let

and

solve the Dirichlet problems for

and

, respectively. A variation–of–parameters identity gives

with homogeneous boundary data. Weighted Schauder estimates for degenerate Wright–Fisher operators [

30,

31] yield

where

depends only on

m and boundary weights. This bounds the first two terms in (

25). The preparation error

accounts for imperfect initial overlaps due to finite

and geometric asymmetries; under the regularity assumptions in

Section 2, this error is

. Combining gives (

25). □

Remark 24 (Coupling viewpoint).

An alternative proof couples the perturbed diffusion with drift

to the neutral Wright–Fisher process by Girsanov’s theorem [

53,

64]. A Novikov condition holds for small

, and the total variation distance of path measures up to

is

, implying the same

bound on absorption probabilities.

8.2. Degeneracies, Continuous Spectra, and POVMs

Degenerate outcomes.

Suppose the apparatus eigen–domains are grouped into

degenerate bins (e.g. identical eigenvalues or coarse readout), and only the bin label is recorded. Let

be the face corresponding to bin

k and define

. By linearity of the Wright–Fisher SDE on coordinates (Appendix M),

is again a Wright–Fisher coordinate (summing components preserves martingales and absorption) [

31,

33]. Therefore,

and the Born weights add across degenerate channels.

Continuous spectra.

For a continuum of channels (outcome space

), approximate by partitions

with mesh

and define

as initial overlaps for

. The absorption measure

converges weakly to a probability measure

on

with density determined by the

overlap field (the Radon–Nikodym derivative is the limit of normalized

). Hence Born probabilities extend to continuous outcomes by a standard projective limit [

8].

POVMs via Naimark dilation.

Let

be a POVM on the microscopic Hilbert space. Realize it as a projective measurement

on an enlarged ancilla+system space via Naimark’s dilation [

68,

77]. In the CFT interface picture, add ancilla alignment channels

coupled unitarily to the system before the boundary layer, so that each

corresponds to a union of orthogonal projective channels in the dilation. By the degeneracy argument above,

with

the density operator induced by the preparation (pure state:

).

8.3. Basis invariance and Gleason-Type Constraints

We now justify that quadratic (Born) dependence is forced by natural consistency axioms once outcomes are identified with orthogonal apparatus channels.

Definition 25 (Frame function on projectors). Let be a complex Hilbert space of dimension . A map assigning probabilities to rank–one orthogonal projectors is a frame function if:

- (F1)

(Normalization and additivity) For every orthonormal basis , .

- (F2)

(Noncontextuality) depends only on P, not on the basis in which P is embedded.

- (F3)

(Measurability/continuity) is Borel measurable on the unit sphere (or continuous).

Proposition 26 (Gleason-type constraint)

. Assume (F1)

–(F3)

. Then there exists a unique density operator ρ such that In particular, for pure preparations , one has .

Proof sketch. This is Gleason’s theorem [

41] for complex Hilbert spaces of dimension

. In our setting, (F1) is frame additivity across apparatus eigen–decompositions; (F2) is basis invariance of the interface (

Section 2); (F3) follows from continuity of overlaps. Thus the only consistent assignment is quadratic. For 2–dimensional systems, add an ancilla and use Naimark dilation (or continuity and nontrivial mixing) to extend the result [

11]. □

Synthesis.

The martingale/absorption derivation fixes the single–trial law to be

in any apparatus basis. Proposition 26 shows that basis–independent, additive assignments over orthogonal channels must be quadratic; therefore identifying

(

Section 2) is not merely convenient but

forced by structural consistency. The stability estimate in Theorem 8.1 then quantifies deviations under realistic imperfections.

9. Experimental and Numerical Signatures

This section discusses measurable and simulable consequences of the alignment picture. We give parameter scalings for alignment/fixation times, show how to bound residual drift by weak monitoring at the interface, and outline a simulation suggestion at both microscopic (chronon) and macroscopic (simplex SDE) levels.

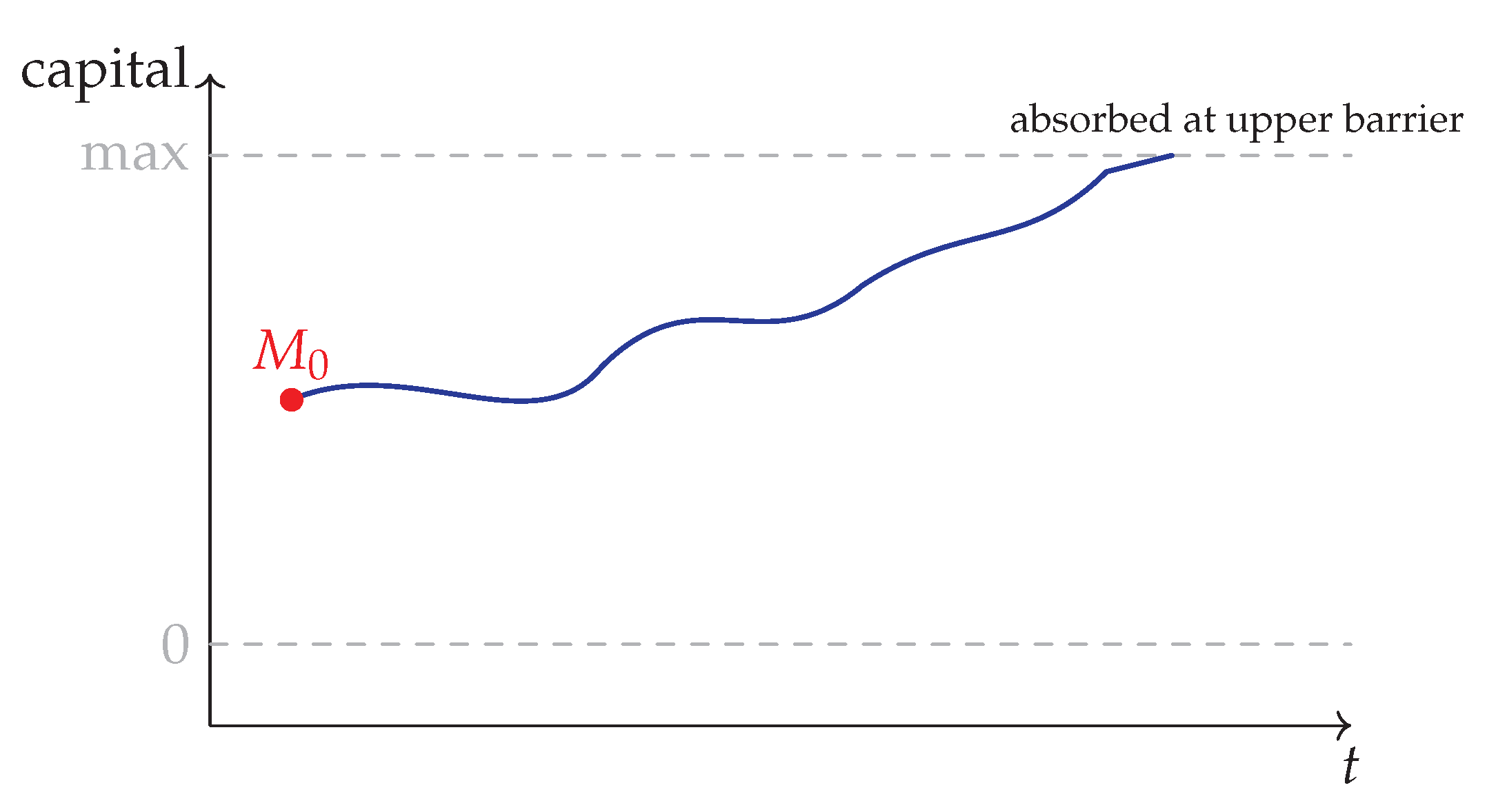

Alignment and fixation timescales; dependence on and

Two stages control the time to a recorded outcome.

(i) Deterministic alignment in the boundary layer.

Let

evolve by the deterministic gradient flow associated with the interface free energy

(zero noise limit of (

8)–(9)). Write

for the unique minimizer in the boundary layer and measure deviations in an

–norm adapted to the boundary metric.

Theorem 9.1 (Exponential alignment)

. Assume is λ–convex in a neighborhood of and that the linearized operator at has spectral gap with respect to the boundary inner product. Then there exists such that for all sufficiently small neighborhoods,

Consequently, the time to enter an –ball of radius ε satisfies

with γ increasing monotonically in the boundary penalty η and decreasing with temperature (via effective convexity).

(ii) Stochastic fixation on the outcome simplex.

After alignment, the overlaps

follow the Wright–Fisher diffusion on

with intensity

(Theorem 3.1). Let

. Then

for constants

depending only on

m [

33,

43]; in the two–channel case [

54],

The diffusion intensity admits a Green–Kubo representation in terms of boundary alignment currents

:

which scales as

with

the effective boundary mobility (increasing with

) and

a dimensionless stiffness factor depending smoothly on

[

59].

Combining (

27) and (

28) gives the lock–in time

decreasing with stronger coupling (larger

) and colder boundary (larger

).

Drift Constraints from Weak Monitoring

Residual symmetry breaking (finite , geometry, temperature) produces a small effective drift in the simplex dynamics, biasing outcome probabilities (Theorem 8.1). We outline an experiment to bound by weakly monitoring the overlaps before absorption.

Protocol.

Prepare many identical runs with the same

and

weakly interrogate the interface at a cadence faster than fixation yet weak enough not to alter

at leading order. From short increments

collected away from the boundary, define

(the latter from sample variances).

Sample complexity and bound.

Under the neutral model,

and

. A Bernstein/Freedman inequality [

36,

89] yields

for a universal

, where

is the time average along the run (bounded by

). To certify

with confidence

it suffices that

A union bound over

gives a uniform constraint on

, which feeds into Theorem 8.1 to bound deviations from Born weights.

Numerical Method: Chronon Lattice and Simplex SDE

We recommend a two–tier simulation strategy.

Tier I: microscopic chronon simulation (boundary layer).

Tier II: macroscopic SDE on the simplex.

Simulate the Wright–Fisher SDE (

14) with the measured

, using an Euler–Maruyama scheme [

57] with projection to the simplex interior and absorbing at the vertices (or a square–root factorization for exact covariance).

Verify the martingale property and the absorption law across a grid of initial conditions.

Add a small drift and perturb as indicated by the chronon estimates; quantify deviations from Born via Theorem 8.1.

For repeated trials, generate empirical frequency histograms and compare with the Sanov LDP (Theorem 7.1): plot

against

[

19].

Reporting and diagnostics.

Key plots include: (i)

vs.

and

; (ii)

vs.

(log–log to expose scaling); (iii) fixation time distributions vs.

compared with (

28)–(

29); (iv) bounds on

from (

34); (v) LDP verification by linearity against

.

Experimental readout.

In atom/photonic interferometry or solid–state platforms with spatially resolved detectors, can be tuned by coupling (aperture, impedance matching); by temperature/cryogenics; and by detector geometry. Weak monitoring of overlaps can be implemented by low–gain probe pulses or non–destructive readouts calibrated to leave invariant to first order. Expected signatures: faster lock–in with stronger coupling (decreasing ) and Born–consistent outcome frequencies with deviations bounded by Theorem 8.1.

10. Discussion

Synthesis.

We have given a coordinated derivation of Born probabilities in the chronon framework along three complementary paths: (i) a

martingale/absorption argument on the outcome simplex (

Section 3 and

Section 4), where detailed balance and channel symmetry force zero drift and optional stopping identifies single–shot outcome weights with initial overlaps (cf. [

31]); (ii) a

hydrodynamic limit from microscopic chronon dynamics (

Section 6), which yields the Wright–Fisher diffusion for the overlap vector and pins down the diffusion intensity by a boundary Green–Kubo formula [

59]; (iii) a

large–deviation analysis of empirical frequencies (

Section 7), establishing that fluctuations concentrate exponentially at the Born vector with rate

[

19]. Robustness bounds (

Section 8) quantify deviations induced by finite interface strength, temperature, geometric asymmetry, and small residual drifts.

Operational comparison to other approaches.

Collapse models (e.g. GRW/CSL [

4]) postulate stochastic modifications of the Schrödinger equation; by contrast, stochasticity here is

classical, confined to the apparatus boundary layer, and enters only through the chronon alignment dynamics. Unitary quantum evolution for the microscopic degrees of freedom is not modified; definite outcomes arise by absorbing fixation of the overlap diffusion.

Quantum trajectories and continuous measurement theories [

94] also produce martingale structures for conditional state components, typically from measurement back–action; our derivation replaces back–action dynamics with

boundary–induced alignment under detailed balance, then projects onto overlaps that obey a neutral diffusion on the simplex.

QBist/epistemic accounts interpret Born weights as degrees of belief; in contrast, the present probabilities are

frequencies of absorption events in a single–world dynamics, grounded in Dirichlet problems for a diffusion obtained from a hydrodynamic limit.

Consistent histories [

38] identifies decoherent sets of histories and assigns probabilities via a decoherence functional; our construction is effectively a consistent–histories reduction on the interface coarse–graining, with the additional structure that the coarse–grained stochastic dynamics is explicitly identified and reversible with respect to a Gibbs measure. Finally, unlike

branching/many–worlds, the alignment plus absorption yields exclusivity via absorbing vertices on

, not by postulated multiplicity of outcomes.

Conceptual economy.

Three structural ingredients suffice: (i) a stabilized apparatus foliation and unit–norm timelike

; (ii) a reversible noisy alignment dynamics satisfying fluctuation–dissipation [

14]; (iii) orthogonal channelization of the interface and projection to overlaps. No additional probability postulates are needed. Gleason–type constraints (Proposition 26; cf. [

41]) then show that the quadratic form is not merely convenient but

forced by basis–invariant additivity over orthogonal channels.

Scope and limitations.

The diffusion limit rests on mixing/chaos hypotheses for the boundary layer and on time–scale separation (Assumptions 16, 19). These are natural for short–range ferromagnetic chronon couplings and sufficiently strong interface pinning, but require refinement for long–range interactions, glassy disorder, or nonlocal mobilities. The Wright–Fisher covariance and zero drift arise from channel symmetry and detailed balance; small violations introduce controlled errors (Theorem 8.1), yet a full classification of admissible symmetry breakings that still yield Born weights remains open. The present treatment is classical on the apparatus side; while this matches the coarse–grained aim, it leaves open the back–reaction of quantized fluctuations (below).

Open problems.

We list directions where further mathematical development is needed.

Quantization of and constraint algebra. Develop a constraint–consistent quantum theory of the chronon field (canonical or BRST), and analyze how quantum fluctuations of modify the boundary fluctuation–dissipation relation and the overlap diffusion coefficients.

Nonlocal couplings and memory. Extend the hydrodynamic limit to kernels with finite tails (retarded or spatially nonlocal mobilities), including colored boundary noise [

74]. Identify conditions under which the projected process on

remains Markov, or quantify controllable non–Markovian corrections and their effect on fixation probabilities.

Beyond second–order dynamics. Analyze the strictly hyperbolic (damped wave) class (H) at the stochastic level in curved backgrounds, derive its diffusive limit at the interface, and compare transport coefficients with the overdamped class (P).

Sequential and incompatible measurements. For a sequence of measurements with noncommuting channel decompositions, characterize the joint process on the product of simplices and show that Lüders’ rule emerges in the chronon–alignment picture.

Entangled preparations and multipartite interfaces. Extend the analysis to two or more spatially separated interfaces coupled to a common preparation, track the joint overlap diffusion, and derive Tsirelson–bound–consistent correlations without superluminal signalling.

Sharp rates and finite–size corrections. Prove quantitative rates for the hydrodynamic convergence (

Section 6) and for the Sanov LDP under

–mixing (Theorem 7.1), including explicit constants in terms of

and geometry.

Empirical outlook.

The alignment picture yields concrete scalings: the lock–in time

decreases with interface strength

and inverse temperature

, and fixation times scale as

(Eqns. (

28)–(

31)). Weak monitoring of overlaps provides direct bounds on residual drift (Eqns. (

33)–(

34)), which translate into quantitative bounds on deviations from Born via Theorem 8.1. These signatures are accessible in interferometric, photonic, and solid–state platforms with tunable coupling and temperature.

Within CFT, Born probabilities arise as absorption probabilities of a neutral diffusion on the outcome simplex, itself the hydrodynamic limit of reversible noisy alignment at the apparatus boundary. The derivation is operational, basis–invariant, and robust to realistic limitations. Completing the quantum treatment of , extending to nonlocal dynamics, and refining rates will test the universality of this mechanism and further integrate it with covariant emergent–spacetime programs.

11. Conclusion

We have given a complete, operational derivation of the Born rule within the chronon framework for measurement as boundary–induced alignment. At the level of effective observables, we proved that the alignment–overlap vector

on the outcome simplex

arises as the hydrodynamic limit of reversible noisy alignment in the boundary layer and converges to a neutral Wright–Fisher diffusion (Theorem 3.1; cf. [

31]). Channel symmetry and detailed balance enforce zero drift, so each coordinate

is a martingale up to fixation; optional stopping then identifies single–shot outcome probabilities with initial overlaps, yielding the Born weights (Theorem 4.1, cf. martingale methods in [

28]). On repeated trials, empirical frequencies obey a Sanov large–deviation principle with rate

minimized at the Born vector (Theorem 7.1; see [

19]). Quantitative robustness was established against finite interface strength, temperature, and small asymmetries, with explicit error bounds on deviations from Born probabilities (Theorem 8.1). Degeneracies, continuous spectra, and POVMs were handled by grouping, approximation, and Naimark dilation (cf. [

68]), while basis–invariant additivity forces the quadratic law via a Gleason–type constraint (Proposition 26; cf. [

41]).

A practical path to a chronon–based probability law.

The results here supply a pipeline from device parameters to outcome statistics: (i) calibrate the deterministic alignment gap and the boundary diffusion intensity

from relaxation and fluctuation measurements (Green–Kubo formula, Eq. (

30); cf. [

59]); (ii) bound residual drifts

by weak monitoring of overlaps pre–fixation (Eqs. (

33)–(

34)); (iii) predict fixation times and outcome probabilities via the simplex SDE with absorption and apply the robustness bound (

25). This yields a chronon–level, device–controllable account of Born statistics without additional probabilistic postulates.

Next steps.

Three most pressing directions need further development:

Hydrodynamic program to completion. Strengthen Theorem 6.1 to full (non–sketch) proofs with explicit rates in terms of

and geometry; treat long–range kernels and colored noise while preserving Markovian limits or quantifying controlled memory corrections (cf. [

74]).

Tighter robustness and sequential protocols. Sharpen constants in Theorem 8.1; analyze cascaded and incompatible measurements (product simplices), deriving Lüders’ rule and quantifying composition errors from residual drift (cf. [

12]).

Experimental tests. Measure

and lock–in times (Eqs. (

28)–(

31)) across tunable interfaces; implement weak–monitoring bounds on

and verify Sanov scaling for frequency histograms. Extending to multipartite interfaces will test nonlocal correlations against Tsirelson bounds [

79] within the alignment picture.

We have shown that, Born probabilities emerge here as fixation probabilities of a neutral diffusion that is itself the macroscopic shadow of reversible boundary alignment. This closes the conceptual loop between chronon microdynamics, apparatus geometry, and quantum outcome statistics, and provides a concrete route to broaden, test, and ultimately quantize the chronon description in future work.

Interpretational summary.

Chronon Field Theory provides a unified account of outcome definiteness and Born statistics grounded in geometric field interactions. The alignment field mediates coupling between a microscopic quantum system and a macroscopic apparatus with stabilized eigen–domains. Under stochastic fluctuations at the measurement interface, the system probabilistically aligns with one domain, modeled as absorption in the outcome simplex. This structure yields definite outcomes without invoking nonlocality or wavefunction collapse, and derives Born weights as hitting probabilities.

Engineered Definiteness.

A final reflection concerns the status of definiteness itself. In standard accounts, the system is thought to collapse into one of its own eigenstates, as though the definite outcome were already latent in the microscopic degrees of freedom. The present analysis suggests a deeper view: the chronon field of the microscopic system is not classically aligned, and the measured classical features must be engineered by the detector. Definiteness arises only through coupling to an apparatus whose geometry provides stabilized eigen–domains. What the observer records as a single, definite outcome is thus the reflection of the system’s potential structure in the engineered alignment channels of the measuring device. In this sense, the apparatus does not merely reveal but actively constructs the conditions under which the Born rule applies. Such a perspective is consistent with the operational content of textbook quantum mechanics, but reframes it: measurement outcomes are not passively discovered, but dynamically produced by the stochastic geometry of system–apparatus interaction.

Appendix L Existence of Apparatus Eigen–Domains

This appendix provides a formal justification for the existence of a finite family of apparatus eigen–domains along the measurement interface in Chronon Field Theory (ChFT). These domains play a central role in defining the alignment overlap vector and in formulating the measurement dynamics as a stochastic absorption process on the outcome simplex .

Proposition A27 (Existence of Apparatus Eigen–Domains)

. Let denote a macroscopic apparatus region with stabilized coarse–grained field , assumed to be future–directed, unit–norm, and twist–free, and let denote the measurement interface. Then, under the unit–norm constraint and the alignment-based interface energy coupling, the boundary region Γ admits a finite partition into disjoint open subsets

calledapparatus eigen–domains

, with the following properties:

-

1.

Each corresponds to a distinct, locally stable alignment configuration of the chronon field with the apparatus field ;

-

2.

-

The alignment energy , defined over via

is maximized when aligns with the dominant direction in ;

-

3.

The number of such eigen–domains m is finite, determined by coarse–graining resolution and the topological stability of alignment basins under boundary noise;

-

4.

The overlap vector constructed from the defines the initial condition for the stochastic alignment process (Definition 7).

These domains correspond to the measurable outcome channels of the apparatus and provide the geometric basis for stochastic absorption and outcome selection in Chronon Field Theory.

Proof sketch. We outline why a finite family of stable alignment basins (eigen–domains) must exist along the measurement interface under the assumptions of the CFT model.

Step 1: Stabilization of.

The apparatus field is assumed to be stabilized on macroscopic scales (Definition 1). It is approximately constant in both norm and direction within localized neighborhoods on , enabling local alignment analysis.

Step 2: Variational structure of alignment energy.

The alignment energy density is given by a function of the inner product , which is maximized when the fields are aligned. With the choice and the unit–norm constraint on , the energy functional over has local minima corresponding to aligned configurations.

The companion paper [

63] establishes that under a global unit–norm constraint, the chronon field selects Lorentzian signature and prefers alignment with stable time-like directions. These preferred directions arise as energetic minima under the boundary coupling.

Step 3: Domain formation via local minima.

Due to coarse–graining and microscopic fluctuations, is not globally homogeneous. Small inhomogeneities in , local curvature, or interface imperfections create multiple distinct local minima in the alignment energy landscape. Each such minimum corresponds to a region where a specific alignment direction dominates.

The field tends to align stochastically with one of these regions under the boundary dynamics, producing a discrete set of alignment basins—i.e., eigen–domains.

Step 4: Finiteness and measurability.

Because is smooth at the macroscopic scale, only a finite number of such domains can arise within the spatial resolution of the apparatus. Each is an open measurable subset of , and the full boundary decomposes as a finite disjoint union .

Conclusion.

Therefore, a finite collection of eigen–domains emerges from the variational dynamics and stabilized apparatus structure. These domains support distinct alignment channels and provide the geometric basis for the stochastic absorption process used in deriving the Born rule. □

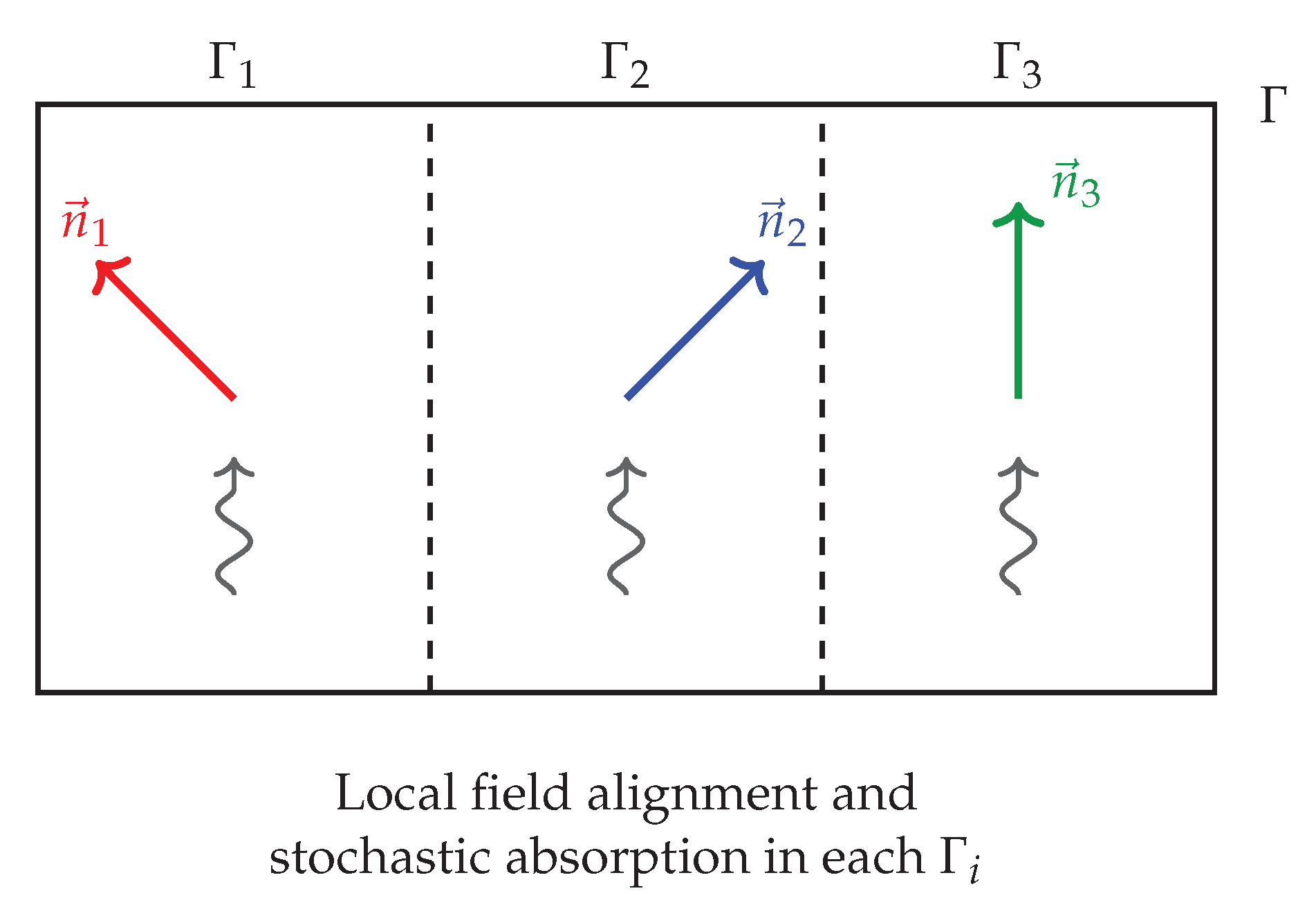

Figure A3.

Schematic representation of the measurement interface , partitioned into three eigen–domains , , and , each corresponding to a locally stabilized alignment direction of the apparatus field, denoted , , and . These coarse–grained domains emerge from the variational coupling between the system and measurement apparatus, and support distinct alignment channels through which the system’s state becomes entangled with macroscopic pointer configurations. The wavy arrows indicate domain–localized stochastic absorption events, representing the probabilistic registration of measurement outcomes and forming the geometric substrate for Born rule derivation.

Figure A3.

Schematic representation of the measurement interface , partitioned into three eigen–domains , , and , each corresponding to a locally stabilized alignment direction of the apparatus field, denoted , , and . These coarse–grained domains emerge from the variational coupling between the system and measurement apparatus, and support distinct alignment channels through which the system’s state becomes entangled with macroscopic pointer configurations. The wavy arrows indicate domain–localized stochastic absorption events, representing the probabilistic registration of measurement outcomes and forming the geometric substrate for Born rule derivation.

Remark A28.

See

Figure A3. When the microsystem undergoes stochastic absorption within one of the eigen–domains—say,

—this domain becomes the site of measurement registration, establishing a definite alignment with the corresponding apparatus direction

. The remaining domains

and

, though still present as structural components of the apparatus interface, become dynamically suppressed. That is, they no longer carry amplitude in the post-measurement state and cease to participate in the entangled system–apparatus configuration. From the perspective of the variational dynamics, these domains no longer contribute to the extremal action paths and are effectively bypassed in the realized outcome. In this sense, they become dynamically empty, providing no support for further absorption events once the outcome is registered in

.

Appendix M SDE on the Simplex with Absorbing Faces

We collect well–posedness, boundary classification, and basic identities for Itô diffusions on the probability simplex

with focus on the neutral (zero–drift) Wright–Fisher covariance and

absorbing boundary at the vertices

; see, e.g., [

31,

33,

54].

Generators, SDE representations, and invariance

We consider second–order operators on

of the form

with the Wright–Fisher covariance

and drift

tangent to

, i.e.

for all

p. The form (

A36) is canonical for neutral multi-allele Wright–Fisher limits [

31,

33].

Proposition A29 (SDE representation and invariance)

.

Let be an m–dimensional standard Brownian motion. Consider the Itô SDE on

started at , where and is the diagonal matrix with entries . Then , for all i, and the formal generator on is (A35)–(A36). (Cf. [31]; see also [53, §5.5].)

Proof. The noise coefficient is

. Since

, Itô yields

(tangency of

b), hence invariance of the hyperplane. Moreover,

which gives (

A36). Nonnegativity follows from the degeneracy of

at

; cf. [

31, Prop. 10.1.1]. □

Well–posedness and boundary classification

Because

is only positive semidefinite and degenerates at

, strong well-posedness may fail globally; the right framework is the

martingale problem with boundary conditions [

31,

86].

Definition A30 (Martingale problem with absorbing boundary)

. Let

be smooth functions compactly supported in the interior. A probability measure

on

solves the martingale problem for

with

absorbing boundary at vertices if

and for all

,

is a

–martingale, and if

p is absorbed on first hitting any vertex

:

for all

whenever

; cf. [

86, Ch. 6].

Theorem M.1 (Existence and uniqueness in law)

. Assume b is continuous, locally Lipschitz on , tangent (), and at most linear growth. Then for each initial law on , the martingale problem for (A35)–(A36) with absorbing vertices is well–posed: there exists a solution and it is unique in law. Moreover, the solution coincides with the weak solution of the SDE (A37), absorbed at the vertices [31,86].

Remark A31 (Reflecting vs. absorbing faces; mutation drift).

Adding a

parent–independent mutation drift

changes the boundary classification: if

for all

i, faces become

entrance (no absorption) and the stationary law is