1. Introduction

Quantum theory remains unmatched in predictive success, yet its conceptual foundations continue to raise long–standing tensions [

13,

72]. Puzzles and paradoxes persist—the measurement problem [

103,

112], wave–particle duality [

18,

36], Schrödinger’s cat [

93], and the nonlocal correlations revealed by Bell’s theorem [

12]. Each of these signals a mismatch between the quantum formalism and the background spacetime structure inherited from classical physics.

The

measurement problem remains the most prominent example. In standard quantum mechanics, states evolve unitarily under the Schrödinger equation, yet measurements yield single, definite outcomes. Copenhagen–type accounts [

18,

57] introduce a collapse tied to a classical observer, but without a well-defined quantum–classical boundary. The Many–Worlds Interpretation [

34,

106] preserves unitarity at the price of postulating a vast multiplicity of parallel worlds, but still can’t recover the Born rule without circularity [

91]. Decoherence–based accounts [

92,

115] explain interference suppression in practice, but can’t explain why a single result is experienced.

Wave–particle duality presents a familiar difficulty. In the double–slit experiment, an undisturbed particle yields an interference pattern, while path detection eliminates the fringes and leaves localized impacts [

36]. Conventional accounts explain this by invoking either nonlocal collapse or the proliferation of branches, but neither option integrates well with a relativistic and ontologically economical framework.

This paper develops

Chronon Field Theory (CFT), a covariant geometric framework designed to reframe these foundational problems. CFT begins with a microscopic timelike field

, whose coarse–graining across many fine–grained regions produces a smooth, future–directed macroscopic field

, the

chronon field. Recent results show that both the Lorentzian signature of

and the unit–norm property

arise dynamically and uniquely from a broad class of microscopic chronon models (

Appendix A, Ref. [

69]). In the same spirit, the Born rule is no longer an assumed axiom but follows from CFT’s intrinsic locality, symmetry, and coarse–graining structure (

Appendix L, Ref. [

70]).

Alignment Structure in CFT

A central organising principle of CFT is the distinction between microscopic and macroscopic alignment:

Fine–grained quantum regions: Each small spacetime region in the quantum regime has a well–defined local timelike , but orientations are generally uncorrelated between regions.

Potential average alignment: Within a given region, microscopic fluctuations exhibit a statistical bias toward some local direction.

Macroscopic correlation: In a stable apparatus, many regions share a robust global alignment that defines the apparatus’s causal geometry.

Measurement as alignment locking: During measurement, the potential average directions of a microscopic system become aligned with the apparatus’s , producing a definite outcome without nonlocal collapse or many–world branching.

Uncertainty from statistical geometry: The quantum uncertainty principle arises as a statistical constraint on chronon fluctuation coherence, with the Planck constant ℏ emerging dynamically as the variance of action across coarse-grained chronon ensembles.

Within this framework, Schrödinger’s cat is a straightforward macro–micro coupling: the cat’s macroscopic is already aligned long before the trigger event, so no long–lived macroscopic superposition exists. Entanglement is reinterpreted as two subsystems sharing a –thread ancestry, so that measurement in one domain constrains correlations in the other without superluminal influence. The double–slit experiment is explained similarly: multiple –thread configurations can coexist within a small coherence domain, sustaining interference; path detection couples one thread to a macro–coherent domain, breaking cross–thread phase coherence.

Scope and Status of the Present Work

With Appendices A and T addressing the emergence of spacetime structure and the Born rule, CFT now offers a covariant, ontologically economical framework in which both features are derived from underlying dynamics. In the main text, we present qualitative, conceptual accounts of three central quantum phenomena: the measurement problem (

Section 4), the double–slit experiment (

Section 5), and entanglement (

Section 6.2). For each, the corresponding mathematical formulation and rigorous derivations are deferred to dedicated appendices:

Appendix E (measurement problem),

Appendix J (double slit), and

Appendix K (entanglement). This separation allows the main text to remain accessible while providing full technical detail for specialists.

Open directions include the formulation of a fully general action principle and a complete quantisation of and . The theory yields scale–dependent predictions such as nonlinear decoherence and curvature–sensitive timing shifts, offering concrete opportunities for experimental test.

The paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 situates CFT within the wider interpretative landscape.

Section 4 develops the account of measurement as geometric embedding.

Section 5 treats the double–slit experiment.

Section 6.1 and

Section 6.2 discuss Schrödinger’s cat and entanglement.

Section 10 presents potential empirical probes.

Section 12 summarises and compares CFT with Copenhagen, Many–Worlds, and QBist/Relational approaches.

2. Theoretical Context

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) grows out of a long–standing tension between the roles of time and geometry in quantum theory and in relativity. In textbook quantum mechanics, time is an external parameter—a background clock carried over from classical mechanics. In general relativity, it is one coordinate in a dynamical spacetime. Bridging this gap has driven decades of work on quantum gravity and related formalisms [

60,

65].

CFT, as developed here, is not yet a full theory from first principles. It is a covariant geometric framework that replaces both the background notion of time and the assumption of a fixed spacetime geometry with a single dynamical causal field. Within this picture, quantum phenomena such as interference and measurement arise from interactions between regions whose fine–grained alignment properties differ—particularly between domains in which local chronon orientations are only statistically biased toward a direction, and those in which such biases are strongly correlated over macroscopic scales.

2.1. Time, Geometry, and Causality as Scale–Dependent

In the standard formulation, time lies outside the Hilbert space and remains fixed, while space and time are treated asymmetrically. That description falters in regimes without a global time coordinate—early–universe cosmology, black hole interiors, and other strongly curved settings.

Relational–time approaches [

86] and internal–clock models [

80] recover time from correlations between variables, but still assume a fixed Lorentzian background. CFT goes further: both causal order and smooth geometry emerge from a dynamical timelike field

whose microscopic behaviour is disordered. At Planck scales

fluctuates strongly and no stable causal structure exists. At quantum scales,

any fine–grained region—whether in empty space or inside a detector—is never perfectly aligned; instead, it exhibits a

potential average alignment direction obtained via coarse–graining. In stable macroscopic systems, these local potential averages are highly correlated, producing a globally aligned, future–directed, unit–norm field

that defines a local arrow of time and the emergent Lorentzian metric. Between these extremes lie regimes with partial causal–geometric coherence, in which multiple alignment domains can coexist.

2.2. Measurement Without Collapse or Branching

The standard measurement problem—how definite outcomes arise—remains unresolved. Collapse models [

10,

46] introduce stochastic terms at the cost of Lorentz covariance. Many–Worlds [

34,

106] keeps unitarity but multiplies ontology. Relational and epistemic views [

40,

87] economise on ontology but risk reducing the quantum state to bookkeeping.

CFT stays single–world and observer–independent [

42,

63]. A measurement is the

alignment–locking of a microscopic domain’s potential average chronon orientation to the global alignment of a macroscopic apparatus. Before interaction, each fine–grained region of the microscopic system has only a statistical bias toward a direction; after interaction, those biases become correlated with the apparatus’s already coherent

. The apparatus does not impose a perfect microscopic order, but rather synchronises the existing statistical tendencies so that subsequent evolution is referenced to its stable geometry. What appears as “collapse” is, in this view, a boundary–induced stabilisation of alignment and local geometry (

Appendix E).

2.3. Relation to Geometric Approaches

Quantum theory has long been framed in geometric terms—the projective Hilbert space with its Fubini–Study metric [

6,

64], Berry’s phase [

14], symplectic and contact structures [

21]. Quantum–gravity programs—causal sets [

17], loop quantum gravity [

88], spin foams [

81]—build spacetime from discrete or algebraic data and give causal order a primary role.

CFT shares the focus on causal geometry but takes the generator to be a smooth, dynamical timelike vector field producing both intrinsic time and the macroscopic metric. When is globally uniform, standard quantum mechanics in a fixed background is recovered. When it varies, domains can exist in which causal and geometric structure are only partially formed and the fine–grained chronon orientations remain statistically disordered.

2.4. Place in the Landscape

The chronon field unifies three strands of foundational work:

Relational, dynamical time–geometry: absolute time and fixed metric are replaced by a field–driven, scale–dependent causal structure that can fluctuate or fail at small scales.

Covariant geometric formulation: the framework is background–independent, Lorentz–compatible, and naturally extendable toward quantum–gravity regimes.

Minimal ontology with dynamical outcome selection: definite results emerge from bias–lock stabilization without branching worlds or ad hoc collapse rules.

With spacetime causal structure and the Born rule derivable from chronon dynamics, CFT has moved beyond a purely heuristic template toward a coherent, testable framework. Open directions include deriving ’s dynamics from a fully general action principle, quantising and , and characterising departures from perfect causal–geometric coherence. Such deviations could yield observable signatures in high–precision interferometry, relativistic quantum information protocols, and potentially in quantum–gravity–scale experiments.

3. Chronon Field Theory: Core Framework

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is a covariant, background–independent reformulation of quantum mechanics in which the effective spacetime geometry—both its temporal structure and causal order—emerges, at sufficiently coarse–grained scales, from a smooth, future–directed, unit–norm timelike vector field

[

73,

104]. This

chronon field replaces the role of external time in conventional formulations, while also generating the Lorentzian metric structure in which events are embedded. In this view, the familiar large–scale geometry of spacetime is not presupposed at the microscopic level, but appears as an ordered phase of the chronon field.

Recent rigorous results (

Appendix A, Ref. [

69]) show that both the Lorentzian signature

of

and the unit–norm property

arise dynamically and uniquely from a broad class of microscopic chronon dynamics, replacing earlier postulates. At sub–Planckian or quantum scales, the underlying causal field

can fluctuate strongly, with norms and directions varying significantly between regions. In such fine–grained domains, no perfect alignment exists; instead, each exhibits only a

statistical bias or

potential average toward a local time direction. The smooth

of CFT is thus an

emergent, coarse–grained descriptor encoding the correlated average alignment of many microscopic regions. In a macroscopic apparatus, these local biases are strongly correlated, yielding a robust global

; in a microscopic quantum system, correlations are weaker and the average alignment less stable.

3.1. The Effective Chronon Field

We consider a smooth, future–directed vector field

satisfying

throughout the coarse–grained domain of validity. The integral curves of

—

chronon threads—define the intrinsic time direction and generate proper–time evolution. The metric

appearing here is the large–scale geometry compatible with

and, in CFT, emerges alongside it from microscopic dynamics (

Appendix A).

For a rigorous statement of the conditions under which such a

yields a global time function, spacelike foliation, and proper time, see

Appendix A.

3.2. Emergent Temporal and Geometric Foliation

Given a sufficiently smooth , one can define a family of spacelike hypersurfaces orthogonal to , labelled by a scalar function interpreted as intrinsic proper time. In CFT, these hypersurfaces are part of the emergent geometry generated by the large–scale ordering of itself, not embedded in a pre–existing background.

When

is hypersurface–orthogonal, the twist tensor vanishes [

38]:

where

projects orthogonally to

.

In that case,

satisfies:

with lapse function:

The

then act as intrinsic time–slices for quantum evolution. A proof that such a foliation and proper–time structure emerge under the stated regularity and integrability conditions is given in

Appendix A. In regions where

loses coherence—because the microscopic

fluctuations fail to yield a stable average—the foliation and effective metric may break down.

3.3. Action Principle and Dynamical Foundations

While the preceding discussion treats

and its induced geometry at the effective, coarse–grained level, a natural next step is to formulate CFT within a fully covariant variational framework.

Appendix B presents a candidate

general action principle in which the chronon field couples to curvature and gauge sectors via geometric invariants built from

,

, and their derivatives. In this construction, the unit–norm property of

is enforced dynamically through a Lagrange multiplier, while the gravitational and gauge dynamics arise from curvature terms and covariant field strengths projected along and orthogonal to

.

The purpose of this appendix is not to claim a definitive microscopic completion, but to provide a coherent starting point from which both classical and quantum equations of motion can be derived, and to clarify how known field theories may emerge as special limits of the chronon–field dynamics.

3.4. Quantum Dynamics Along Causal Threads

In CFT, quantum evolution proceeds in intrinsic proper time

along

’s integral curves, rather than in an external coordinate time. Each

carries a Hilbert space

, and we

postulate an evolution law:

where

depends on the matter content and the

–induced geometry.

In the ADM (3+1) decomposition [

3],

is expressed via the unit normal

to

and a shift

:

In synchronous gauge (

), the Hamiltonian takes the form:

A full derivation from a CFT–specific microscopic action remains for future work.

3.5. Relational Status of the Hilbert Space

As shown in

Appendix C,

is defined

relationally—with respect to the foliation and metric structure induced by

—and may fail to exist in regions where

loses coherence. This is a departure from the global, time–independent Hilbert space of standard QM. Features include:

Local definition tied to the domain of coherent and its induced geometry.

Adaptation to dynamically evolving causal and metric structure.

Interpretation as a correlation space, not a primitive, background object.

3.6. Gauge and Constraint Structure

As a covariant theory, CFT enforces first–class constraints:

including Gauss, diffeomorphism, and Hamiltonian constraints [

59]. Compatibility of a dynamical

and its emergent

with this algebra is assumed at present; proof of closure is an open technical question.

3.7. Recovery of Standard QM in Smooth Limits

When

is constant and spacetime is flat,

coincides with coordinate time

t, and the standard Schrödinger equation is recovered:

Thus CFT reduces to conventional QM in the fully coherent, smooth limit—while offering a framework to handle regimes where causal

and geometric order are incomplete or scale–dependent.

4. Measurement as Local Geometric Stabilization

In standard quantum theory, a measurement is described either as a sudden “collapse” of the wavefunction [

103], or—more recently—as the result of environmental decoherence in a larger Hilbert space [

92,

115]. CFT takes a different starting point: a measurement is neither an epistemic update nor an external “intervention,” but a local and scale–dependent reconfiguration of causal geometry. It occurs when the

average potential alignment direction of a microscopic domain—initially fluctuating and only statistically biased—locks into the

global alignment of a macro–coherent apparatus.

At the fine–grained level, no region is perfectly aligned: the microscopic field exhibits fluctuations in both norm and direction. What distinguishes a macro–coherent apparatus from an isolated quantum system is not the absence of fluctuations, but the strong correlation of local potential averages. In a macroscopic device, many small subregions have potential alignment directions that are themselves closely aligned, producing a robust global . In a microscopic quantum system, these correlations are weak; neighbouring subregions can have differing biases, so the coarse–grained average is unstable.

Measurement, in this framework, is the process by which the microscopic domain’s coarse–grained average chronon orientation becomes correlated with—and stabilized by—the apparatus’s global . This is not merely a choice of a time direction, but the embedding of the system’s causal microstructure into the apparatus’s stable spacetime patch. Once this embedding is complete, subsequent evolution proceeds relative to the apparatus’s emergent geometry.

A central result of this account is that, under general locality, symmetry, and coarse–graining conditions natural to CFT, the statistical distribution of possible stabilized outcomes obeys the Born rule.

Appendix L (Ref. [

70]) summarises the derivation, showing that the rule emerges from the geometric alignment mechanism itself, without being imposed as an independent axiom. Thus, in CFT, both the occurrence of definite outcomes and the quantitative probabilities governing them follow from the same underlying chronon dynamics.

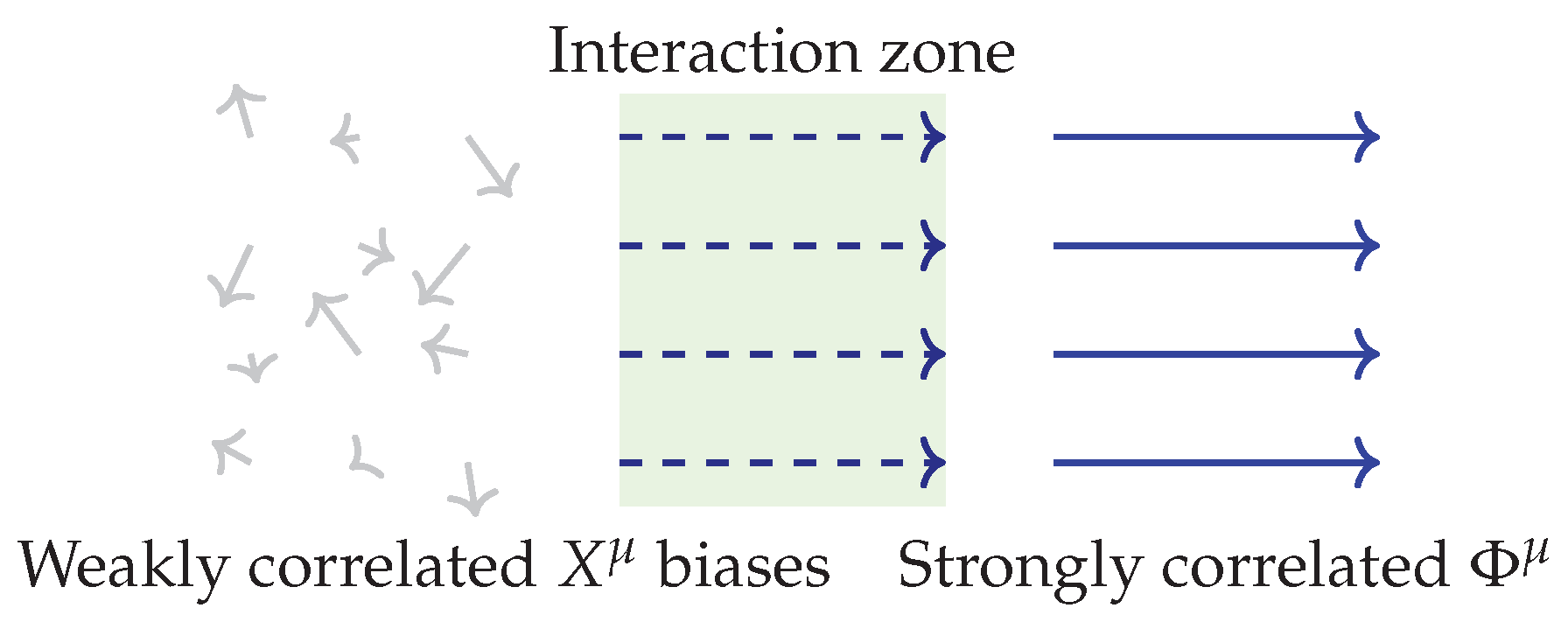

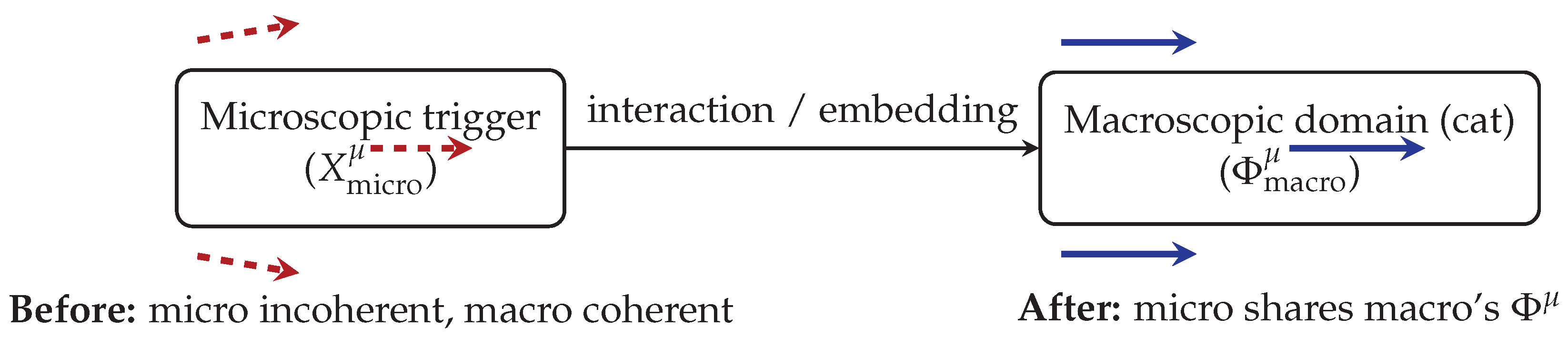

Figure 1.

Measurement as bias correlation: a microdomain with locally fluctuating chronon orientations (left) enters the coarse–graining scale of a macro–coherent apparatus (right). Within the interaction zone, the microdomain’s potential alignment directions become correlated with the apparatus’s global , stabilizing its average time direction and embedding it in the apparatus’s causal geometry.

Figure 1.

Measurement as bias correlation: a microdomain with locally fluctuating chronon orientations (left) enters the coarse–graining scale of a macro–coherent apparatus (right). Within the interaction zone, the microdomain’s potential alignment directions become correlated with the apparatus’s global , stabilizing its average time direction and embedding it in the apparatus’s causal geometry.

4.1. Pre-measurement: Locally Biased, Globally Incoherent

Before interaction, the microscopic domain is described by a fluctuating timelike field

that does

not satisfy the unit–norm constraint and whose preferred directions vary from one fine–grained subregion to another:

The norm and direction vary across the region, producing only short–range correlations and no stable global

. The geometry in this regime is statistical and short–lived, resembling a “pre–causal foam” [

109]. Quantum indeterminacy here reflects the multiplicity of compatible coarse–grainings of these local biases into different potential alignment directions.

4.2. Scale–Dependent Coupling to the Apparatus

When the microdomain interacts with a macro–coherent apparatus, the effective coarse–graining scale increases. Local biases in

first align with their immediate neighbours, then with larger correlated regions, until they are locked to the apparatus’s global

. This multi–scale locking process is gradual:

In this picture, what standard QM calls “wavefunction collapse” corresponds to the point at which the correlation extends across the entire microdomain, leaving no room for incompatible alignment histories.

4.3. Hierarchy of Stabilization Scales

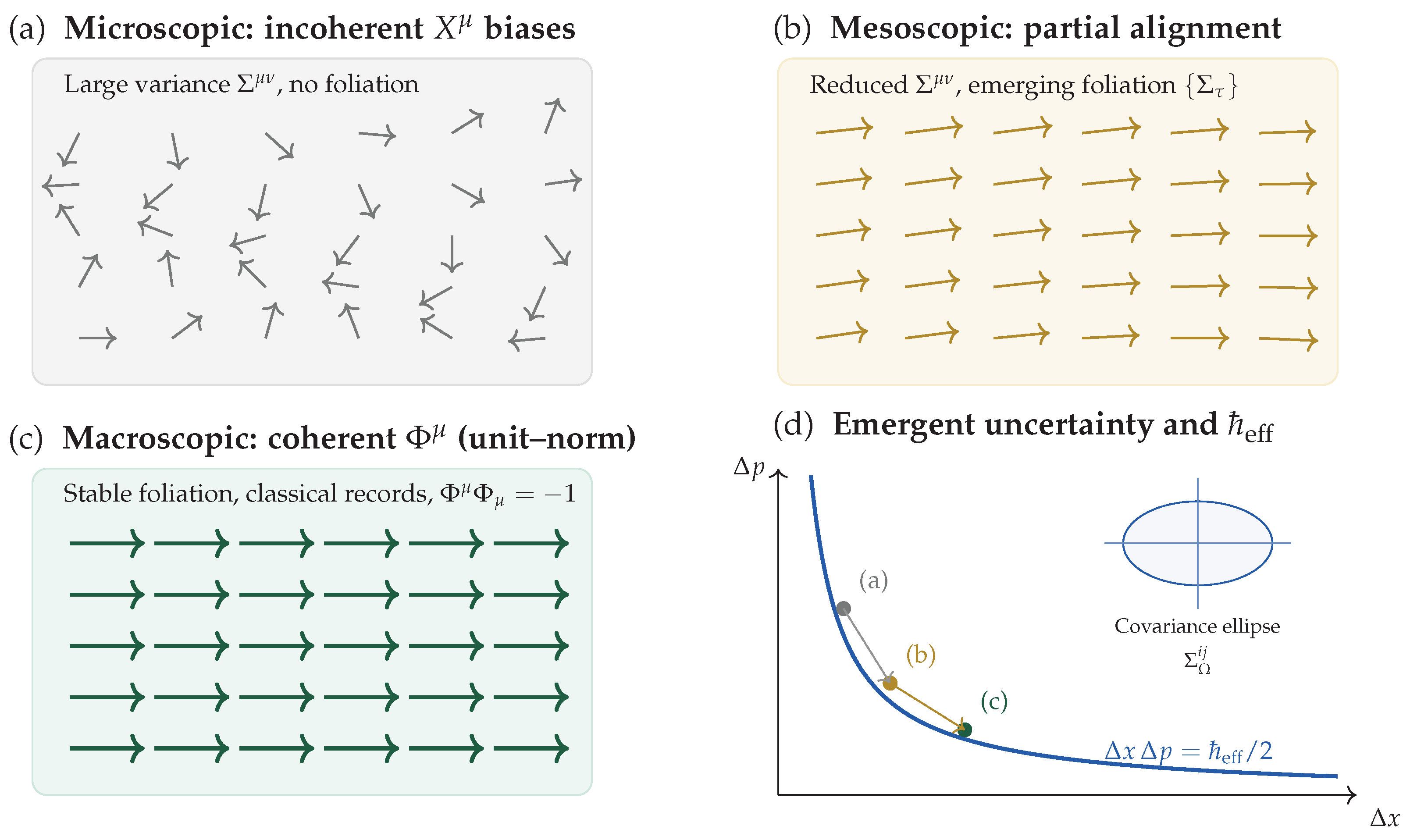

The stabilization process can be viewed as a hierarchy of scales:

Microscopic: fine–grained subregions with fluctuating , weakly biased.

Mesoscopic: intermediate domains where local averages are partially correlated.

Macroscopic: global apparatus with strong long–range correlation.

Measurement is complete when correlations have percolated from the microscopic to the macroscopic scale, embedding the system’s causal structure into that of the apparatus.

CFT models the emergence of classicality as a hierarchy:

Planck scale: maximal disorder; no persistent bias or geometry.

Quantum scale: weakly correlated local biases; interference possible between regions of different potential alignment.

Mesoscopic scale: intermediate correlation; some directions stabilized, others fluctuating.

Macroscopic scale: strongly correlated biases; global stable under perturbations, defining a persistent causal geometry.

Measurement is the embedding of a weakly correlated bias structure into a strongly correlated one, forcing the smaller system into the latter’s global alignment and thereby producing a definite outcome without requiring nonlocal collapse or branching worlds.

5. The Double-Slit Experiment in Chronon Field Theory

The double-slit experiment remains one of the clearest demonstrations of quantum coherence [

36]. In conventional accounts, a particle is said to display “wave–particle duality,” with collapse or branching invoked when a which–path detector is present. CFT reframes this entirely in terms of the causal–geometric properties of

: interference occurs when the local

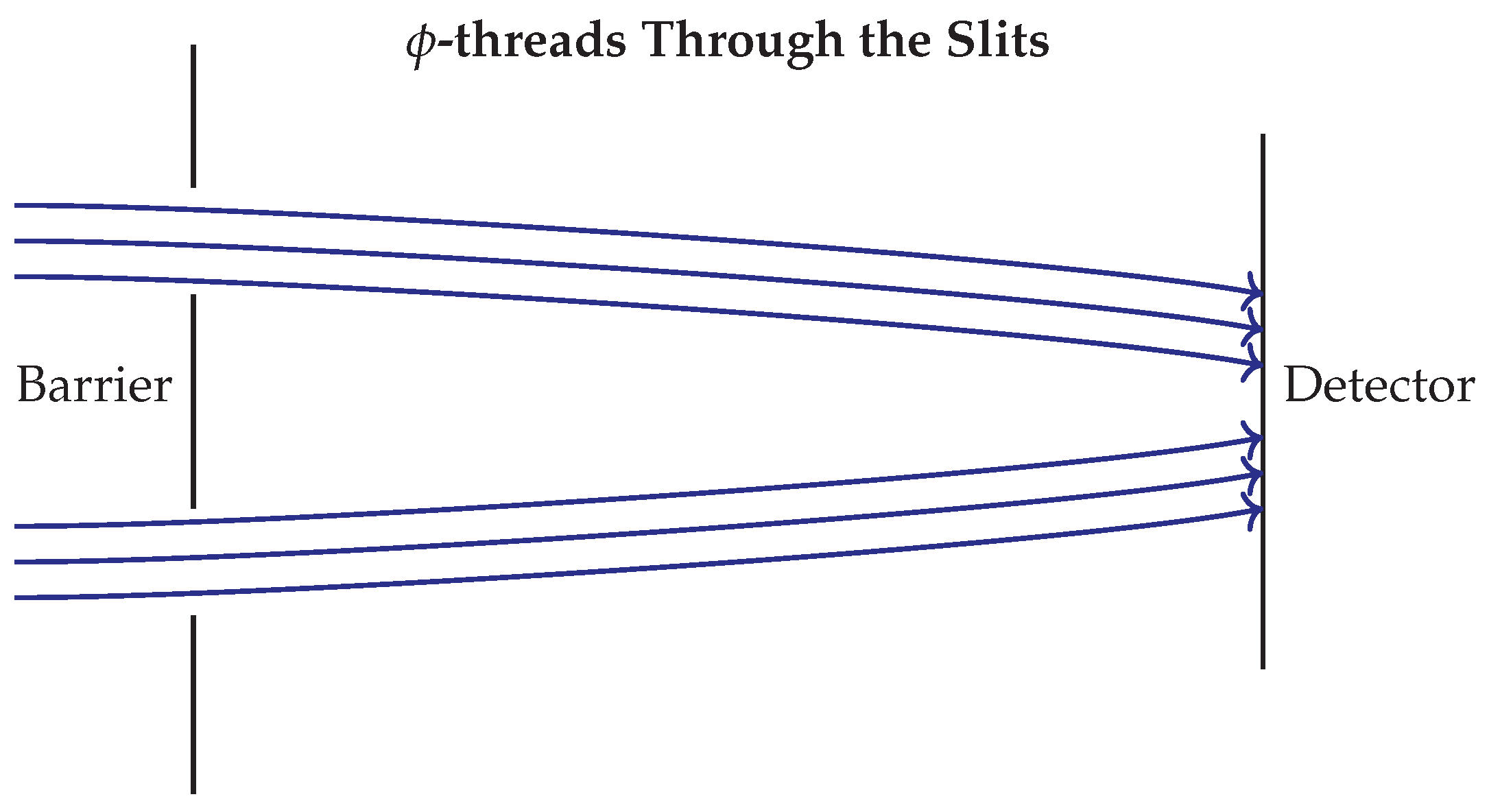

potential average alignment directions of the chronon field remain sufficiently correlated across both paths at the experiment’s scale, and disappears when those correlations are broken by embedding one path into the macro–coherent domain of a detector. See

Figure 2.

5.1. Two Levels of Chronon Correlation

We distinguish between:

Microscopic (local) correlation: Within a small spacetime region, the fine–grained field fluctuates, but the distribution of its orientations can be biased in such a way that phase relations are maintained across multiple paths. This bias correlation—though far from perfect alignment—is sufficient to sustain interference if preserved over the relevant path separation.

Macroscopic (global) correlation: Across a large domain, the local potential averages themselves are strongly correlated in direction, yielding a stable, coarse–grained that defines a single time orientation and supports persistent, classical records.

In a detector–free double–slit setup, the “microsystem”—the quantum excitation plus the narrow regions of bias along each path—remains in the first regime. The bias orientations along the two paths remain correlated enough to sustain a shared phase reference, since no macroscopic causal boundary forces them into different alignments.

5.2. Interference as Correlated Bias Histories

The apparent “superposition” is reinterpreted as the joint evolution of bias–correlated

–threads—integral curves of the coarse–grained

—through both slits inside a single, locally correlated microstructure. Let

and

be two such bias–carrying threads from the source

to a point

on the screen. The detection amplitude is modeled heuristically as:

where

encodes the stability of the bias correlation along that thread. Interference occurs when both threads retain a mutual phase reference defined by their shared bias correlation.

5.3. Detector Interaction: Bias Lock–in to Macro Alignment

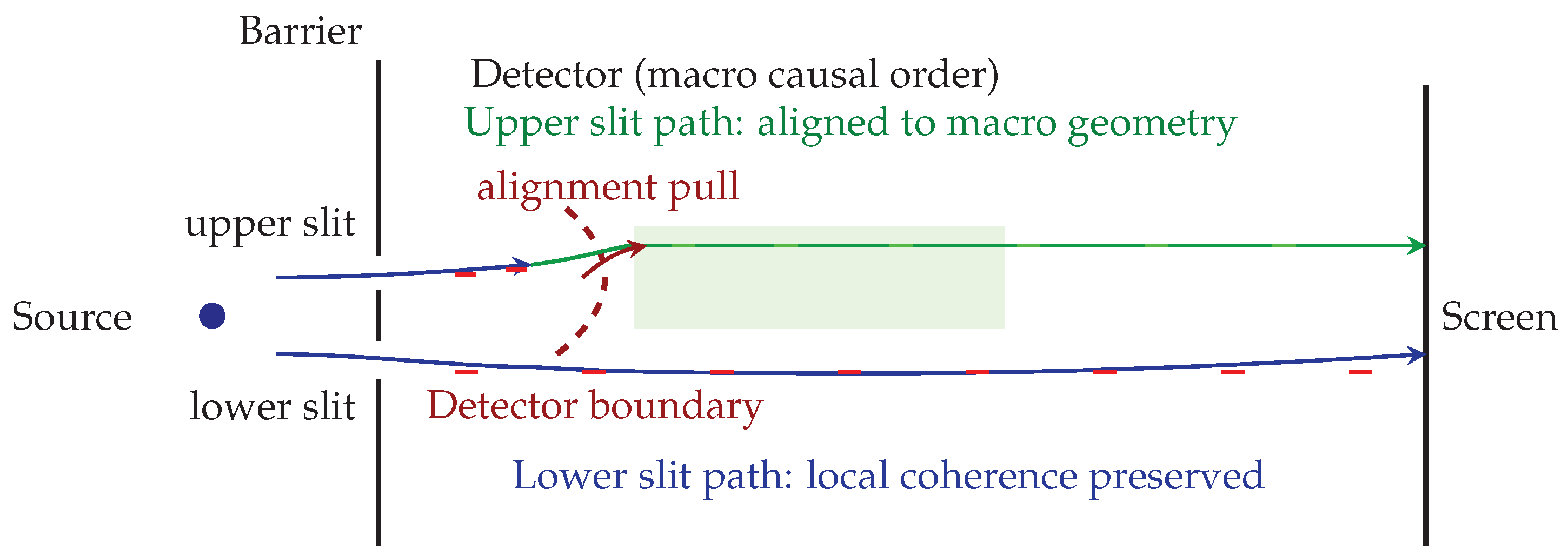

Placing a which–path detector at one slit changes the bias–correlation structure at the experiment’s scale. The detector belongs to a macroscopic apparatus whose is already in the strong–correlation phase. When a microscopic bias–carrying thread encounters this domain, the boundary interaction locks its local potential average orientation to the apparatus’s global .

This locking process destroys the original bias correlation between the two paths: the aligned path now shares the apparatus’s global orientation, while the unmeasured path retains its original local bias. From the coarse–grained viewpoint, the allowed histories

reduce to a single bias–compatible thread. Interference disappears—not through nonlocal collapse, but because causal–geometric bias correlations have been severed at the relevant scale, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

5.4. Summary

In CFT, interference requires only the persistence of correlated local potential averages across both paths—not global unit–norm alignment of . A measurement corresponds to the irreversible coupling of one path’s bias orientation to a macro–coherent domain, fixing its large–scale time orientation and eliminating the shared phase reference needed for interference. This explains how a microsystem can exhibit interference in one configuration yet yield a definite outcome when one path is monitored.

6. Other Foundational Puzzles in CFT

The double–slit experiment shows how CFT replaces the usual “wave–particle” story with a scale–dependent causal–geometric one. Two other famous puzzles—Schrödinger’s cat and quantum entanglement—pose the same conceptual challenge in different limits: (1) the junction between microscopic and macroscopic domains, and (2) correlations maintained across spacelike separation. In CFT, both can be reframed in terms of local bias correlations in the fine–grained chronon field and the persistence of shared causal ancestry.

6.1. Schrödinger’s Cat: Macro–Micro Bias Coupling

In the usual account [

93], a microscopic quantum event (e.g. a decay) triggers a macroscopic consequence (a cat’s life or death). Linear quantum evolution then seems to extend the superposition to the cat—something never seen in actual macroscopic systems.

In CFT, the setup contains two domains with very different correlation scales:

Macroscopic domain (cat, detector, box): strongly correlated local biases; at the coarse–graining scale of the apparatus, the emergent is smooth, future–directed, and stable under perturbations.

Microscopic trigger (nucleus, emitted particle): small–scale domain where fluctuates and only exhibits short–range bias correlations; no single alignment direction spans the macro region.

Before interaction, the microdomain’s

evolves with bias orientations uncorrelated with

. When coupled through the detector, the coarse–graining scale grows to include the microdomain: its local bias distribution is

locked to the apparatus’s global bias orientation, i.e. to

. As shown in

Figure 4, this bias lock–in fixes one stable causal geometry inside the cat’s domain, and with it, one definite physiological outcome.

Two viewpoints:

Inside the box: The cat’s body is already a macro–coherent domain. As soon as the trigger interacts, the microdomain’s bias orientation locks to the cat’s , and the cat’s physiology follows one definite trajectory (alive or dead) in its own causal frame. There is no stage where the cat is “both” from its own perspective.

Outside the box: An external observer’s is uncorrelated with until the box is opened. From outside, the description may be an “entangled superposition,” but in CFT this represents ignorance of which bias–locked macro geometry already exists inside. Opening the box couples the observer’s to , revealing the outcome without invoking a real collapse.

Thus, the “paradox” becomes a simple matter of when and where bias correlations stabilize across scales.

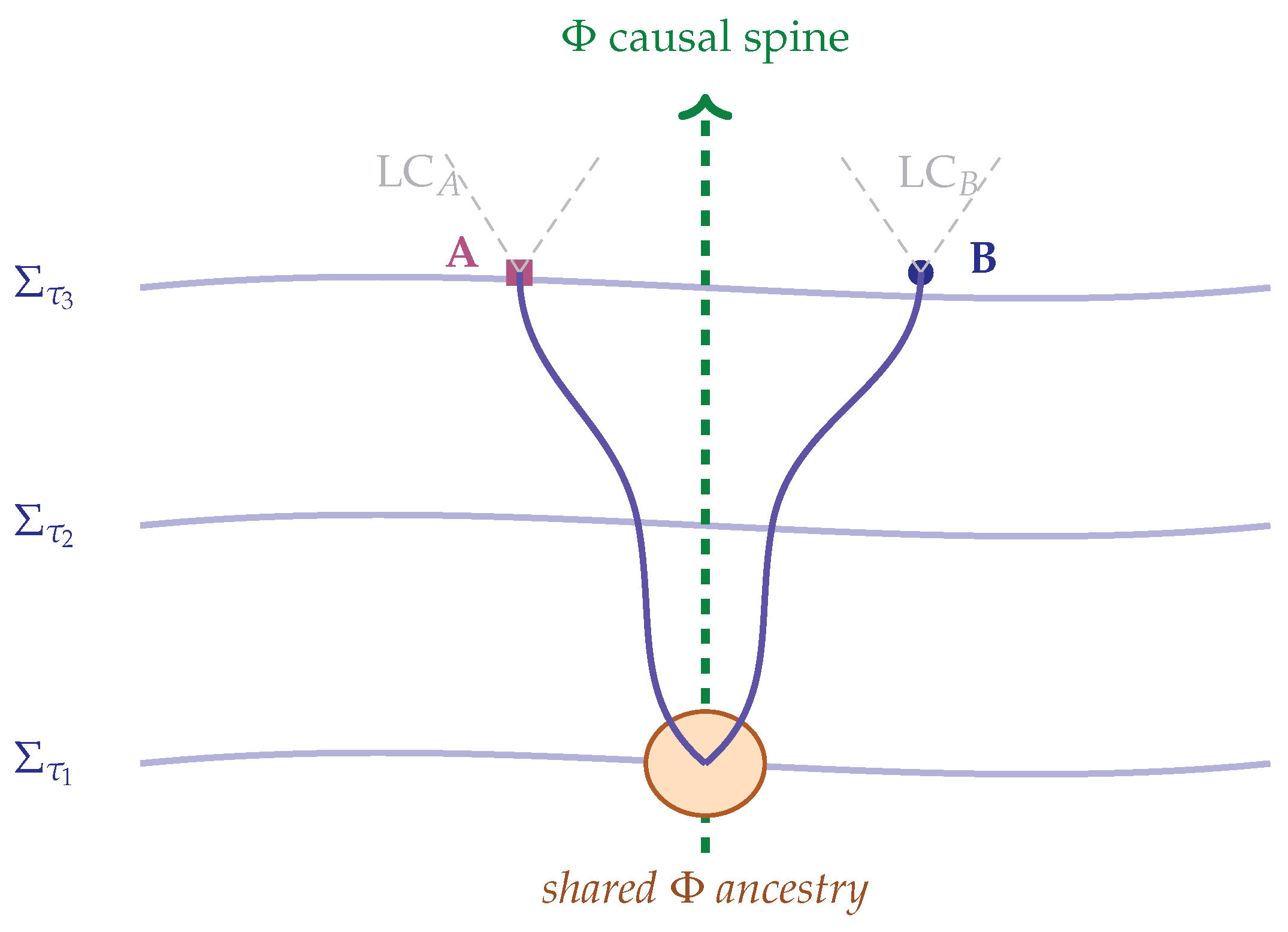

6.2. Entanglement: Correlated Bias Ancestry Across Separation (Rigorous Formulation)

In the standard story [

12,

33], entanglement seems to require nonlocal influences or many–world branching. In CFT, as illustrated in

Figure 5, the correlations arise from the

shared bias ancestry of the subsystems’ chronon fields: two subsystems are correlated because their local bias orientations originated in the same connected microstructure of

.

Preparation.

When A and B are produced, their microscopic chronon fields form a connected bias-correlated network within . Relative phase information is defined within this common structure.

Separation.

As A and B move apart, their bias distributions remain statistically linked via the shared ancestry, even though continues to fluctuate locally.

Measurement.

Lock-in of A’s local bias to the apparatus constrains B’s bias through the pre-existing correlations. This fixes the joint statistics without superluminal signalling.

Bell violations.

Let

M be the variational distance

Then for local, deterministic outcome maps

,

one finds the bound

A quantum-maximal value

requires

. An explicit toy model realising this bound is given in

Appendix K.

7. No Need for Many Worlds or Wave–Particle Duality

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) aims to describe all quantum phenomena within a single, scale–dependent geometric framework in which every region—no matter how small—retains microscopic

fluctuations and is never perfectly classically aligned. What changes with scale is the

statistical bias of those fluctuations: in large, stable domains, local bias directions correlate strongly enough to form an emergent, unit–norm

at the coarse–graining scale. With the emergence of Lorentzian signature and unit–norm

now derived from chronon dynamics (

Appendix A), and the Born rule shown to follow from CFT’s locality, symmetry, and coarse–graining assumptions (

Appendix L), neither the Many–Worlds Interpretation (MWI) nor the standard wave–particle duality is required [

18,

34,

111]. Instead of parallel realities or disjoint regimes, CFT treats quantum behaviour as arising from the bias–correlation structure of a single spacetime.

7.1. Many–Worlds: Points of Departure

MWI preserves unitarity by letting all possible outcomes occur in separate branches of a universal wavefunction [

34,

106], at the cost of postulating an empirically inaccessible branching multiverse.

CFT departs from MWI on several points:

- (i)

Ontological economy: MWI multiplies entire universes [

99]; CFT posits one spacetime with one fluctuating

field whose bias correlations vary by scale.

- (ii)

Basis choice: MWI branches depend on decoherence to define a preferred basis; CFT outcomes are tied to the foliation fixed when local bias correlations lock into a macro–coherent .

- (iii)

Probabilities: Born–rule derivations in MWI [

27,

106] risk circularity. In CFT, outcome frequencies follow from the relative measure of stabilized bias configurations in the chronon path integral, as shown in

Appendix L, with no independent probability postulate.

- (iv)

Branch dynamics: MWI has no local mechanism for when/where branches split. CFT replaces this with boundary–driven bias–lock transitions in one causal geometry.

7.2. Minimal Ontology

The ontology is a Lorentzian manifold plus a chronon field

whose fine–grained fluctuations are ever–present, and whose coarse–grained bias orientation

becomes well–defined only above certain scales. In a complete theory,

would follow from a covariant action [

73]. Measurement is a dynamical bias–correlation process: a micro–domain’s local bias locks to a macro–coherent

through interaction, producing outcome statistics in accordance with the Born rule (

Appendix L).

7.3. Replacing Wave–Particle Duality

In the double–slit story, one alternates between wave and particle models. CFT uses a single model:

Without macro–scale bias lock–in, local coherence can extend across multiple paths, preserving phase correlations (“wave–like” behaviour).

Coupling one path to a macro–coherent domain locks its bias to that domain, breaking phase correlation and producing a discrete hit (“particle–like” behaviour).

Both limits emerge from one chronon field with scale–dependent bias correlations, with the Born-rule probabilities arising from the measure over compatible chronon configurations.

7.4. Path Integrals and Relational Links

In a path–integral view [

36], only histories whose

fluctuations are compatible with the

–defined causal structure at the relevant scale contribute. This incorporates the bias–geometry directly into amplitude calculations. Unlike relational [

87] or QBist [

40] interpretations,

is an observer–independent physical field; the wavefunction is defined relative to its foliation, not to an agent’s beliefs. See

Appendix G for details.

7.5. Outlook

If successful, CFT would unify time, measurement, and the quantum–classical transition: time as a local dynamical property, measurement as bias lock–in to a macro–coherent

, and “wave” versus “particle” as two regimes of one causal–bias structure. Its geometric foundation makes it naturally compatible with covariant quantum–gravity frameworks [

52,

75].

8. The Ontological Status of the Wavefunction

Since the beginnings of quantum theory [

7,

28,

56], there has been debate over whether the wavefunction

is ontic or epistemic. In CFT,

is neither a universal field on configuration space nor mere knowledge—it is a

foliation–dependent functional that appears only after local bias correlations have stabilized into a coarse–grained, unit–norm

.

8.1. Wavefunctions as Foliation–Dependent Functionals

Let

be hypersurfaces orthogonal to

in a stabilized domain. The wavefunction

encodes correlations across

:

where

depends on the matter content and the induced geometry.

is undefined in pre–stabilization regions where no coherent foliation exists.

8.2. Between Ontic and Epistemic

CFT’s :

has physical content—its domain and correlations are fixed by the stabilized and the local bias distribution;

but is derived—it emerges only after the geometric/bias structure is fixed, and is not a fundamental object in its own right.

8.3. Collapse as Bias–Lock Transition

Because

exists only after

bias–lock to

, there is no need to

postulate collapse [

102]. What appears as collapse is a geometric stabilization (

Section 4) in which fine–grained bias fluctuations become highly correlated to a macro–scale orientation. After stabilization,

Appendix A and

Appendix C show how

is well–defined.

8.4. Born Rule from Statistical Geometry

In CFT, the Born rule is not assumed but

derived (

Appendix L, Ref. [

70]) from the statistical measure over stabilized bias configurations, subject to CFT’s locality, symmetry, and coarse–graining conditions. If

is the set of

fields yielding a given outcome, then:

with the path integral restricted to admissible pre–lock

fields. In the smooth–foliation limit, this reduces exactly to

, while allowing for small, testable deviations in cases of incomplete stabilization.

8.5. Summary

In CFT:

is emergent—appearing only after coarse–grained bias correlations stabilize;

it is relational—defined relative to the foliation from ;

it is causally grounded—reflecting structures in spacetime;

and derived—a secondary description, not a primary element of ontology.

9. Emergent Uncertainty Relations in Chronon Field Theory

In conventional quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle arises from the non-commutativity of operators associated with canonically conjugate observables (e.g., position and momentum) [

56,

85]. In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), however, neither operators nor observables are fundamental. Instead, physical quantities and their statistical correlations emerge from the coarse-graining of a fine-grained, dynamically fluctuating timelike vector field

. In this section, we develop a formulation of the uncertainty principle in CFT as a geometric-statistical constraint on the fluctuations and correlations of pre-stabilized chronon configurations.

9.1. Pre-Stabilization Fluctuations and Bias Variance

Prior to macroscopic stabilization, the chronon field

exhibits local fluctuations in both magnitude and direction. Let

denote a coarse-grained average over a region of scale

, and define the local potential alignment direction (bias vector) as:

The emergent macroscopic chronon field

arises in the limit where bias correlations become stable and long-ranged [

69]:

Fluctuations in

across a spacetime domain

can be characterized by the variance tensor:

The nonzero components of

quantify the statistical spread in directionality of the chronon field. In particular, in regions where

or

are large, no stable foliation (and hence no classical evolution) exists.

9.2. Conjugate Observables and Emergent Uncertainty Bounds

Once coarse–graining yields a smooth foliation

orthogonal to

[

104], we can define effective relational observables such as position

on

and the associated momentum

with respect to the induced metric

. Their statistical uncertainties are defined by

Theorem. In any stabilized domain, the Peierls bracket induced by the

–adapted effective action satisfies

Quantization with respect to the emergent Planck scale

(

Appendix I) then yields the uncertainty relation

where

quantifies curvature–induced deviations from flat foliation [

5,

52].

Proof sketch. The Robertson–Schrödinger inequality gives

. From the path–integral weight

one obtains

, which establishes (

21).

A complete proof, including the Peierls–to–commutator correspondence, is provided in

Appendix I.4.

Physical intuition. Measuring

uses data on a single leaf

, yielding a coarse–grained position average. By contrast,

is the generator of translations along

and operationally requires comparing positions across two nearby leaves

and

. At the fine–grained level, causal alignment between these leaves is not exact, so the fluctuations that enter the position estimator and those that enter the momentum estimator cannot be perfectly correlated. Their product therefore has a nonzero lower floor, set by the action–variance density of chronon ensembles—that is, by

. In the limit of globally coherent

and vanishing curvature this reduces to the standard Heisenberg relation, while in general the bound receives corrections from decoherence gradients and causal inhomogeneities [

32].

Importantly, if two observables are not canonically conjugate in the –induced symplectic structure, then the commutator term vanishes at leading order and no universal –scaled bound exists: only model–dependent covariance terms remain.

9.3. Statistical Interpretation

The uncertainty bound above should be interpreted not as a fundamental kinematic limit, but as a statistical constraint on the coarse-grainability of local chronon configurations. It quantifies the trade-off between positional localization (requiring tight alignment of

vectors across space) and momentum definition (requiring coherence of phase correlations across proper time evolution) [

19,

45].

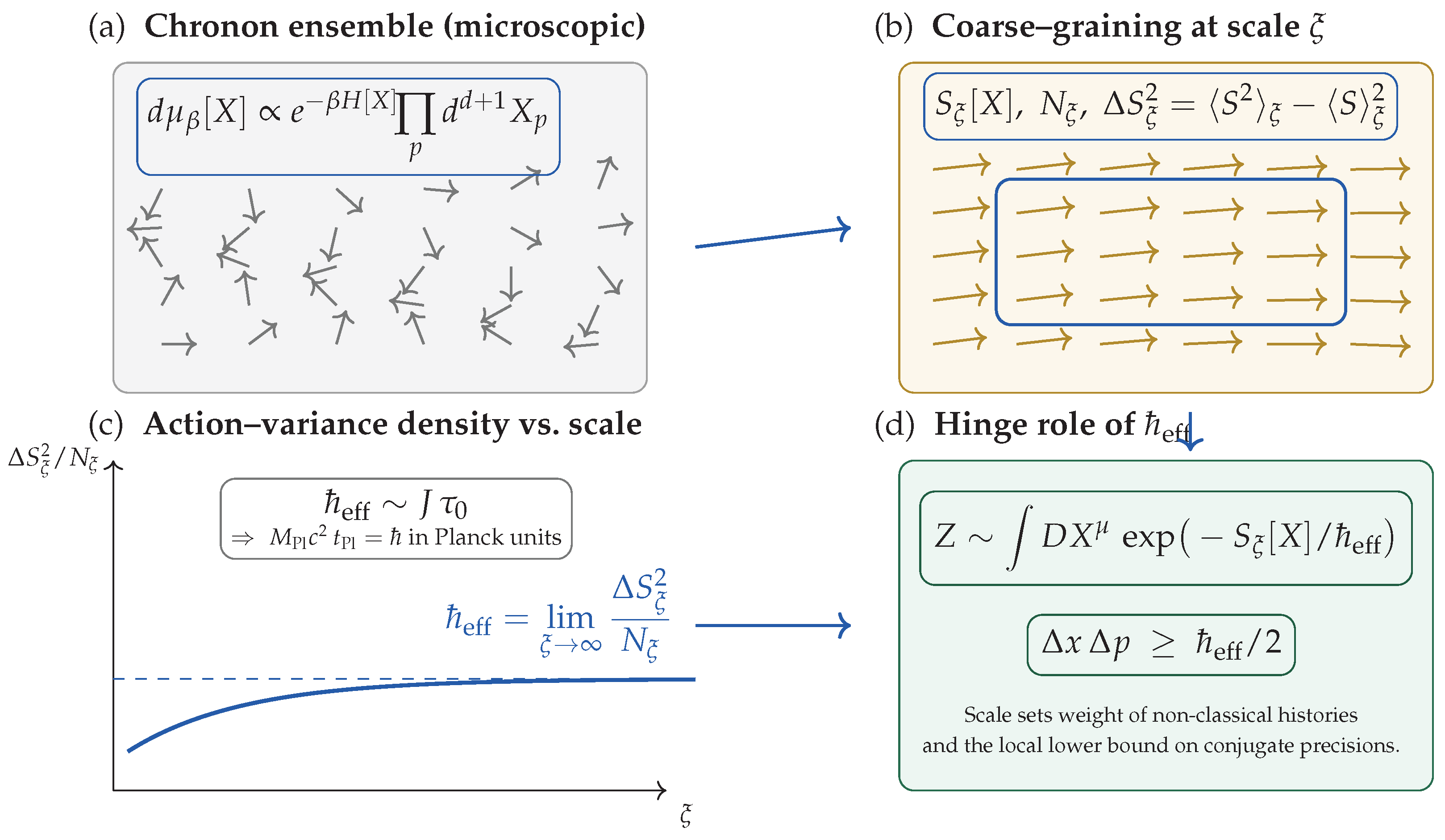

In this sense, uncertainty is a manifestation of incomplete causal-geometric coherence in a domain. It reflects the finite capacity of chronon ensembles to support simultaneous sharp structure in both spatial foliation and directional flow. For a schematic illustration, see

Figure 6.

9.4. Outlook

Future work will develop a more precise derivation of the uncertainty bound by integrating the chronon fluctuation statistics into the full path integral formulation of CFT [

75]. In particular, we aim to compute higher-order corrections and quantify deviations from standard quantum mechanics in partially stabilized domains.

In

Appendix I, we establish a geometric-statistical definition of

and discuss its possible computation from chronon ensemble dynamics.

10. Experimental Outlook

Because CFT links quantum phenomena to the scale–dependent bias correlations of and the emergent , each predicted deviation from standard QM has a concrete causal–geometric interpretation. In every case, no region is perfectly aligned at the fine–grained level; observable effects arise when residual microscopic bias fluctuations or incomplete macro–scale correlation leave small but systematic signatures.

Potential probes include:

Weak–measurement bias asymmetry: Test for small, systematic shifts in pointer statistics arising from incomplete

bias–lock in weak–coupling regimes [

1]. In CFT, a persistent offset would reflect a pre–measurement bias–correlation skew due to chronon fluctuations.

Interferometry in gravitational gradients: Use long–baseline atom or photon interferometers to detect curvature–induced phase drifts linked to perturbations in the coarse–grained

orientation, quantified by

[

83,

114]. Here, spacetime curvature modulates bias correlations in a way that slightly distorts coherence.

Causal–order tests under engineered bias shifts: Implement quantum–switch protocols [

78] while varying local EM or gravitational potentials to induce controlled bias–correlation changes in

. Any alteration in indefinite–order statistics would suggest that bias orientation participates directly in process–order constraints.

Vacuum–noise anisotropy: Search for small, direction–dependent variations in zero–point noise spectra [

22] inside well–stabilized laboratory regions. In CFT, a macro–scale

bias orientation can subtly break local isotropy, leading to detectable spectral anisotropies.

These proposals are exploratory, but each ties a measurable effect directly to the degree and stability of bias–correlation in the chronon field, offering a concrete route to falsification or confirmation of the CFT framework.

11. Future Work and Open Questions

CFT is a framework proposal rather than a complete theory. Key steps ahead include:

Quantizing the chronon field: Incorporate quantum fluctuations of and its couplings to matter and gravity, and clarify how these fluctuations interact with the causal–geometric constraints.

Deriving the full stabilization dynamics: Obtain conditions, timescales, and uniqueness from a first–principles dynamics of bias–correlation alignment, including the role of boundaries, interactions, and noise.

Proving the coarse–graining property: Demonstrate from explicit models that the unit–norm feature of emerges only as a coarse–grained property, even when all fine–grained regions remain imperfectly aligned. This entails defining a suitable averaging procedure over local bias vectors and showing analytically and/or numerically that the effective field approaches in the large–scale limit.

Numerical studies: Simulate interference loss, decoherence rates, and boundary–induced alignment in lattice or semiclassical models, explicitly tracking the evolution of bias–correlation statistics across scales.

Coupling to curvature and gauge fields: Test consistency with GR and QFT in curved backgrounds, and quantify how perturbations alter coherence, bias alignment, and emergent foliation.

Experimental tests: Develop the proposals in

Section 10—weak–measurement bias asymmetry, curvature–induced phase drift, causal–order perturbations, and vacuum–noise anisotropy—into precise, falsifiable experiments.

Several aspects of CFT are already on firm ground—for example, the dynamical emergence of Lorentzian signature and unit–norm

(

Appendix A), and the derivation of the Born rule from locality, symmetry, and coarse–graining (

Appendix L). Other ingredients, including a full quantisation scheme and a complete dynamics from an action principle, are still missing. These gaps are to be expected at this early stage. Even so, the present results suggest that a covariant and economical account of time, causality, and measurement is possible within this framework. Given CFT’s potential, we encourage further work by the research community to strengthen the mathematics, extend the physical scope, and test the predictions experimentally.

Table 1.

Conceptual Comparison of Chronon Field Theory with Major Interpretations

Table 1.

Conceptual Comparison of Chronon Field Theory with Major Interpretations

| Aspect |

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) |

Many-Worlds (MWI) |

Relational QM / QBism |

Copenhagen |

| Time |

Emergent from chronon field ; locally foliated |

Background global time for unitary evolution |

External or relational time between agents/systems |

Classical background time as external parameter |

| Measurement |

Local geometric phase transition; stabilization of

|

Branching into decohered world-histories |

Belief update or relational event correlation |

Causes discontinuous collapse; observer-dependent |

| Causality |

Dynamically generated by ; defines intrinsic arrow of time |

Emergent from unitary branching |

Observer-relative or undefined |

Undefined; collapse introduces acausality |

| Decoherence |

Foliation breakdown as geometric decoherence |

Environment-induced decoherence between branches |

Agent’s loss of predictive coherence |

Collapse is postulated; decoherence added heuristically |

| Unitarity |

Preserved locally on leaves ; generalized conservation |

Globally preserved for the universal wavefunction |

Internal to agent’s system; belief evolution |

Broken by measurement collapse |

| Wavefunction |

Relational functional over foliation; not ontic |

Ontic and complete universal state |

Epistemic or agent-relative tool |

Epistemic state of knowledge; collapses on observation |

| Uncertainty & Planck Constant |

Statistical bound from chronon fluctuations; ℏ emerges as coarse–grained action variance () |

Fixed axiom of Hilbert space structure |

Epistemic information limit; ℏ taken as background constant |

Postulated universal scale in measurement theory |

| Born Rule |

Statistical law of stabilized chronon ensembles; derived from locality and coarse–graining |

Postulated branch–weight rule for the universal wavefunction |

Agent’s subjective probability update rule |

Fundamental axiom without derivation |

| Ontology |

Field realism: and matter fields fundamental; wavefunction foliation–relative |

Ontic universal wavefunction; all branches real |

Epistemic/agent–relative; no objective state |

Dualistic split: quantum system + classical apparatus |

| Philosophy |

Covariant realism: time and causality as physical structures |

Multiverse realism with maximal ontology |

Pragmatic anti–realism; subjective epistemology |

Instrumentalist positivism; predictive rules over realism |

12. Conclusion

We have presented Chronon Field Theory (CFT) as a covariant, geometric framework in which the role of fixed background time is replaced by a dynamical, future–directed vector field . In this picture, quantum evolution, measurement, and the emergence of classicality all follow from the local behaviour of this field—specifically, from the scale–dependent transition between incoherent chronon configurations and stabilized, unit–norm causal order .

The chronon field has a dual role: it fixes the local direction of proper time and generates a foliation of spacetime into intrinsic hypersurfaces

along which quantum states evolve. We have proposed that measurement is a

local geometric phase transition, where a microscopic, partly coherent domain is irreversibly embedded into a macro–coherent causal structure. If correct, this yields definite outcomes without the machinery of observer–triggered collapse, proliferating worlds, or other extra ontological layers [

34,

41,

106].

Within this framework, the double–slit experiment is read as interference between phase–coherent –threads along multiple causal routes; a detector breaks this coherence by aligning one path with a macroscopic domain. The usual “wave–particle duality” is replaced by a single causal geometry whose behaviour depends on the scale and stability of .

Other standard paradoxes take on a similar form. Schrödinger’s cat becomes a case of micro–macro causal embedding, with macroscopic stability ruling out extended superposition. Entanglement reflects a shared –thread ancestry between distant systems, where correlations follow from the coherence of a single causal network rather than superluminal influence.

A major conceptual advancement of this framework is that both the

uncertainty principle and

Planck’s constant are emergent phenomena. The uncertainty principle arises as a statistical constraint on the coarse–grainability of chronon fluctuations, with bounds controlled by the effective action variance of chronon ensembles. Planck’s constant

ℏ is not an ontological universal scale, but as an emergent asymptote

defined by the large–scale limit of chronon action fluctuations (

Appendix I). This dual emergence links the structure of quantum indeterminacy directly to the statistical geometry of spacetime itself.

We have shown that CFT departs from standard quantum mechanical interpretations by framing spacetime geometry and causal order as emergent properties of coarse–grained chronon fluctuations; grounding measurement in the scale–dependent stabilization of rather than in observers or many–world branching; replacing background Hilbert–space evolution with evolution on hypersurfaces determined dynamically by ; deriving the Born rule as a theorem of stabilized chronon ensembles rather than postulating it; and identifying both the uncertainty principle and Planck’s constant as emergent features of chronon ensemble statistics rather than as fundamental axioms.

Author Contributions

Bin Li is the sole author

Funding

This research received no external funding

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Appendix A. Emergence and Exclusivity of Lorentzian Unit–Norm Structure in CFT

A foundational feature of Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is the large–scale causal and metric structure of spacetime—Lorentzian signature

and a future–directed, unit–norm timelike field

. In this appendix we summarise recent rigorous results [

69] showing that these properties arise naturally from a class of random microscopic chronon dynamics, and that they are

the only structures compatible with physically realizable observers under broad axioms.

Physical intuition. Random chronon fluctuations have no preferred scale or signature, but when coarse–grained they tend to align, much like spins in a ferromagnet. This alignment naturally stabilizes a future–directed, unit–norm timelike field, and only the Lorentzian signature allows finite propagation speeds and consistent observer records. Other signatures are dynamically unstable or observationally incoherent, so the theorems below show why the Lorentzian, unit–norm structure is the unique large–scale outcome.

Appendix A.1. Framework

Microscopic chronon variables

are placed on a lattice or locally finite point set, with nearest–neighbour couplings

and a local potential

where

pins the norm toward

in the emergent metric

. Configurations are sampled from the Gibbs measure

with

the interaction energy and

the inverse temperature.

Coarse–graining at scale

yields an effective macroscopic field

with an

–invariant effective action of the form

Appendix A.2. Theorem A (Existence)

For sufficiently low temperature (), there exists a positive–measure phase in which:

- (i)

and uniformly on a percolating domain ,

- (ii)

has Lorentzian signature on D,

- (iii)

the twist tensor on D, allowing a global foliation and proper–time function.

The proof combines renormalization–group arguments for –invariant ferromagnets, Ising–type percolation for time–orientation, and suppression of twist in the ordered phase. Foliation follows from standard orthogonality theorems.

Appendix A.3. Theorem B (Exclusivity)

Under the following general axioms:

- (i)

well–posed local dynamics for second–order PDEs (Hadamard sense),

- (ii)

finite–speed signal propagation,

- (iii)

acyclic causal order,

- (iv)

existence of stable records in finite subsystems,

the only compatible metric–vector field pairs are those with Lorentzian signature and a globally defined, future–directed, unit–norm timelike . Euclidean signatures violate (ii) and (iii), ultrahyperbolic signatures violate (i), and non–unit–norm timelike fields violate (iv).

Appendix A.4. Theorem C (Boundary-Induced Selection, Uniqueness, Exponential Convergence, and Front Propagation)

Let

have boundary

, and suppose the exterior contains an ordered domain

with

satisfying

,

, and

. For the effective action

of

Appendix A with

,

,

, impose Dirichlet data

. Then:

(i) There exists a unique minimizer of with . Moreover, a.e. in and , hence defines a proper–time foliation in compatible with that of .

(ii) The –gradient flow with converges exponentially to in .

(iii) For the underlying Gibbs ensemble at inverse temperature , the probability that the coarse–grained field differs from by more than on any ball is .

(iv) In slab geometries with a moving interface , there is such that the aligned phase invades any finite subregion at speed at least (up to logarithmic transients).

Appendix A.5. Implications for CFT

These results elevate the Lorentzian/unit–norm structure from a postulate to a theorem within CFT for a broad class of microscopic models. Measurement, in this framework, is reinterpreted as a boundary–induced embedding of a disordered chronon domain into the unique observer–compatible Lorentzian/unit–norm phase.

Full details: For full proofs of the above theorems A–C and extended discussion, see Ref. [

69].

Appendix B. General Chronon Action Principle

A fully general formulation of Chronon Field Theory (CFT) requires a covariant action from which the large–scale field, its couplings to matter and gauge fields, and the emergent spacetime geometry all follow. In this appendix, we provide a preliminary proposal.

Appendix B.1. Action Structure

Let

be a four–dimensional Lorentzian manifold with metric signature

, equipped with a fundamental chronon vector field

. The coarse–grained, unit–norm

emerges in the large–scale limit via the bias–correlation mechanism described in the main text. At the fundamental level, the action takes the form:

where each term is described below.

Chronon sector.

The pure chronon field contribution is

where

sets the preferred norm in the low–energy limit,

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing the norm constraint at the coarse–grained level, and

is a coupling constant with dimensions of [mass]

2. The first term governs the stiffness of

and penalises rapid variation; the constraint term ensures that in the emergent limit

.

Gravitational sector.

Spacetime curvature is dynamical, with

where

R is the Ricci scalar and

the cosmological constant. This term itself can arise from integrating out microscopic chronon degrees of freedom.

Gauge sector.

Gauge interactions are included via

where

are the field strengths of the gauge fields

. In a unified formulation of CFT, a local U(1) gauge field can be interpreted as Goldstone modes of broken symmetries associated with

alignment, demonstrating the emergence of the like of a photon and electromagnetism.

Matter sector.

The matter Lagrangian couples minimally to the emergent metric

and can also couple directly to

:

Direct

couplings allow for curvature–sensitive decoherence rates and alignment effects, as discussed in

Section 10.

Appendix B.2. Field Equations

Varying

with respect to

,

,

, the gauge fields, and the matter fields yields:

together with the usual matter field equations. Here

is the stress–energy tensor of

derived from Eq. (

A2).

Appendix B.3. Status and Open Issues

The action above is the most general low–energy form consistent with:

Lorentz covariance at the coarse–grained scale,

a dynamical chronon field whose norm is fixed only emergently,

minimal coupling to curvature and gauge fields.

Open problems include:

In the meantime, Eq. (

A2)–(A.5) provide a concrete starting point for analysing CFT’s predictions, connecting its conceptual framework to a Lagrangian field theory suitable for both analytical and numerical investigation.

Appendix C. Hilbert Space Construction and Generalized Unitarity

Appendix C.1. Hilbert Space Tied to a Dynamical Foliation

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), the Hilbert space is not simply taken for granted. It is defined

relative to a foliation of spacetime that emerges from the dynamics of a future-directed, unit-norm timelike vector field

[

6,

60]. When

is in a stable configuration—something we take here as a postulate—it slices spacetime into a one-parameter family of spacelike hypersurfaces

, each orthogonal to

. These slices act as “moments of simultaneity” for the causal geometry set by

.

Given a slice

, the associated Hilbert space is

with inner product

where

is the functional integration measure over field configurations on

[

65]. The idea is similar to canonical quantization on a fixed time slice [

29], except that here the slice itself is picked out dynamically by

.

Appendix C.2. Generalized Schrödinger Evolution

Once a foliation

is fixed, quantum states evolve according to

where

comes from projecting the field Lagrangian density

onto

, with all dependence on the foliation carried through

[

105]. This makes sense as long as

remains smooth and timelike in the region being considered.

Appendix C.3. Path Integral Viewpoint

The same evolution can be written in terms of a path integral over histories compatible with the chronon field:

with the action

evaluated along the

-induced foliation. Only histories consistent with the causal structure of the classical chronon field are included [

36,

98].

Appendix C.4. Unitarity Without Global Time

In ordinary quantum mechanics, unitarity is framed in terms of a global time evolution operator

obeying

. CFT replaces this with a statement about conservation of the inner product along the foliation:

valid whenever

changes smoothly between

and

and no measurement-induced stabilization occurs. If a stabilization event happens, the foliation changes and so does the Hilbert space; in that case, the relevant object is a transition probability obtained from a path integral over possible

configurations (see

Section 6).

Appendix C.5. Summary

In this formulation:

The Hilbert space is defined relative to the foliation set by , not as a universal background.

Unitarity becomes a local-in-foliation conservation law.

The familiar global picture of quantum mechanics is recovered when is constant and defines a global simultaneity surface.

Whether this construction remains consistent under a full quantization of is an open question, and one of the natural next steps for the theory.

Appendix D. Toward Field Quantization of Φ μ (x)

In the main discussion, the chronon field

has been treated as a

classical object: a future-directed, unit-norm timelike vector field acting as an order parameter for local temporal geometry. If CFT is to become part of a fully dynamical, background-independent quantum theory, we will eventually need to face the question of how to

quantize itself. What follows is not a completed construction, but a sketch of possible approaches, their associated constraints, and how they might fit into the larger quantum-gravity landscape [

59,

88].

Appendix D.1. Constraint Surface and Configuration Space

The field obeys a non-linear, pointwise constraint

so its allowed configurations form a section of the future unit-hyperboloid bundle over the spacetime manifold

M:

Any quantization scheme must work either directly on this constraint surface or via a consistent extension from it. This is reminiscent of non-linear sigma models [

24] and Nambu–Goldstone modes [

108], where the target space geometry is fixed by symmetry breaking.

Appendix D.2. Canonical (Dirac) Quantization

One direct route is to pick a candidate Lagrangian

for

, define the canonical momentum

, and note the primary constraint

together with any secondary constraints required to preserve

in time. Dirac’s procedure [

30] then leads to operator relations

on the unconstrained phase space, with the

enforced either on states (“weakly”) or by solving them outright. Residual gauge freedoms—such as reparametrizations along

—must be fixed or factored out to keep the algebra consistent.

Appendix D.3. Covariant Path Integrals and BRST Methods

A more covariant option is to build the constraint into the functional measure from the outset:

with

the Faddeev–Popov determinant for the chosen gauge [

35]. If reparametrization or other local symmetries are present, BRST quantization [

11,

101] becomes natural: one introduces ghost fields and a nilpotent

satisfying

In a semiclassical regime, stabilized

configurations could then appear as BRST-cohomology classes.

Appendix D.4. Connections to Quantum-Gravity Programs

Because directly determines a causal foliation, it sits naturally alongside several existing approaches:

Relational clocks in LQG: acting as a physical time variable in loop quantum gravity or spin-foam models, analogous to scalar reference fields [

31,

89].

Causal set theory: serving as a coarse-grained “arrow of time” map on the causal poset [

17].

Order parameters in group field theory: potentially signalling spontaneous breaking of time-reversal or boost symmetry [

77].

On the cosmology side, a quantum

could in principle help set the arrow of time in the early universe or contribute to effective stress–energy in inflationary and dark-energy phases [

9].

Appendix D.5. Where This Leaves Us

Quantizing is an open technical problem. Among the issues that would need to be settled are:

writing down a compelling consistent with Lorentz covariance and the norm constraint,

ensuring that the constraint algebra closes once quantized,

understanding how a quantum couples to matter and gravity without violating causality.

A resolution would bring CFT closer to a fully quantum, background-independent theory—one in which causal structure itself is a dynamical, quantized field.

Appendix E. Measurement as Boundary–Induced Alignment: A Toy–Model Derivation

In the main text (

Section 4), we described measurement in CFT as the irreversible embedding of a partially coherent chronon configuration

into a macro–coherent domain’s

[

27,

115]. Here we present a simple mean–field derivation of this

alignment effect from a phenomenological effective action [

23,

67], with the important caveat that in CFT any fine–grained “quantum” region is

never perfectly aligned and does not satisfy the unit–norm condition pointwise. Instead, the

field of the macro–domain represents a coarse–grained average over many such regions, and the emergence of

is itself a conjectured

large–scale property to be proved from the microscopic dynamics.

Appendix E.1. Setup

Consider two adjacent spacetime domains:

We model the interface between them as a narrow transition zone of thickness , across which the chronon field interpolates between the fluctuating and the coarse–grained .

Appendix E.2. Effective Action with Interface Term

Let the scale–dependent effective action be

where

penalizes deviations from

coarse–grained unit norm and

penalizes spatial/temporal gradients in

[

50]. Here

denotes the coarse–graining scale: for small

the “unit–norm” term acts only weakly, reflecting that fine–scale configurations are not strictly aligned and that

fluctuates around

.

At the interface, we add a coupling term favouring alignment with the macro–domain average:

where

h is the induced metric on the interface, and

measures the strength of the coupling to the macro–coherent field.

Appendix E.3. Euler–Lagrange Equations and Alignment

Varying

with respect to

gives

where

is a Dirac delta supported on the interface.

In the static limit near the interface and neglecting curvature of

, the dominant terms balance as

with

n the proper distance orthogonal to

.

Integrating Eq. (

A22) across

yields the jump condition

Appendix E.4. Energy Minimization and Stability

In the bulk of

,

is large at the coarse–graining scale of the apparatus, forcing

and

on average. The interface term lowers the total action whenever

has a positive projection onto

, and the gradient penalty

ensures that this alignment penetrates into

over a length scale

For exceeding the micro–domain size, the average over that domain is drawn into alignment, yielding in the coarse–grained sense. Pointwise fine–scale fluctuations remain, but their net effect is suppressed, producing the stable causal order associated with “measurement” in CFT.

Appendix E.5. Interpretation

This toy calculation shows that, given a simple gradient–plus–norm–penalty effective action and a local interface coupling, the energetically preferred configuration is one where the coarse–grained aligns with across the micro–domain. The alignment length sets the scale over which “measurement”—in the CFT sense of boundary–induced geometric stabilization—occurs.

The large–scale Lorentzian signature and timelike nature of are ontological starting points, but unit–norm and full foliation are emergent. Here the interface model illustrates how the emergent part—the stable norm and long–range coherence—can be enforced dynamically by coupling to an already coherent macro–domain, without assuming perfect microscopic order at any scale. A complete theory must still derive the large–scale limit from the underlying disordered dynamics.

Appendix F. Scale–Dependent Decoherence from Chronon–Field Fluctuations

In

Section 4 and

Section 5 of the main text, we described the emergence of classicality in CFT as a

scale–dependent stabilization of the effective chronon field

as the coarse–graining length

increases [

62,

115]. Here we provide a simple quantitative estimate of the

coherence length and its impact on interference visibility, using standard methods from effective field theory and statistical mechanics [

23,

67].

As in

Appendix E, we emphasise that in CFT the

unit–norm condition is

not imposed microscopically. It is instead conjectured to emerge dynamically after coarse–graining from the underlying fluctuating field

. Proving this emergence from the

dynamics remains an open problem (see

Section 11).

Appendix F.1. Linearized Fluctuation Spectrum

Let

be a perfectly stabilized, coarse–grained, unit–norm configuration in a macro–coherent domain. In a micro–coherent or partially coherent region, we write

where

are small fluctuations satisfying

to preserve the norm constraint to first order

at the coarse–graining scale.

Expanding the effective action (Eq. (12) in the main text) to quadratic order in

yields

where

acts as a

scale–dependent mass term for coarse–grained chronon–field fluctuations [

50].

Appendix F.2. Coherence Length

In flat spacetime, the fluctuation equation reads

The equal–time spatial correlator then decays as [

15]

with the

coherence length

As increases, grows—suppressing coarse–grained norm deviations—and changes more slowly. Thus decreases with scale: large coarse–graining produces stronger macro–coherence but shorter spatial reach of compatible chronon orientations.

Appendix F.3. Impact on Interference Visibility

In a two–path interferometer with path separation

d, the interference visibility

is proportional to the chronon–orientation correlator between the two paths:

where

is the ideal (perfect–coherence) visibility.

Thus:

Appendix F.4. Interpretation

This result formalizes the “gradual stabilization” picture: as the coarse–graining scale increases, grows, shrinks, and the system transitions from long–range bias correlation (quantum–like) to short–range bias correlation (classical–like).

In CFT terms:

Both lengths collapse to the same scale in the large– limit where approaches a smooth, unit–norm field.

A full derivation of

from microscopic

dynamics, together with a proof that

at large

, would close the gap between this phenomenological EFT treatment and the foundational postulate of

Section 2.

Appendix G. Path–Integral Restriction to Φ μ –Compatible Histories

In

Section 5 and

Section 7.4 of the main text, we described interference as arising only from histories compatible with the causal–geometric structure set by

[

62,

115]. Here we define this restriction explicitly and illustrate its effect on a simple propagator, using the Feynman path–integral formalism [

37] and ideas from restricted/coarse–grained histories [

43].

Appendix G.1. Admissible Histories

Let

be a smooth, future–directed, unit–norm timelike field in a stabilized domain. For a timelike worldline

parametrized by

, define its

tangent misalignment angle via

where

and the minus sign ensures

for perfect alignment.

We define the

admissible set of

–compatible histories as

with

a tolerance parameter reflecting the residual fluctuation scale of the stabilized chronon field.

Appendix G.2. Restricted Propagator

For a scalar particle of mass

m in flat spacetime with constant

, the unrestricted Feynman propagator is

with

the standard action.

In the

–restricted case, we insert a projector

into the path integral:

where

Appendix G.3. Gaussian Tolerance

A smoother implementation replaces

by a Gaussian weight:

with

controlling the allowed spread of misalignment [

51].

In this case, the restricted propagator can be evaluated perturbatively. For small , paths with large are exponentially suppressed, reducing the interference between geometrically incompatible histories.

Appendix G.4. Effect on Interference

In a double–slit setup with both slits in a micro–coherent domain, is approximately constant and both path families lie in , so and full interference is recovered.

If a which–path detector aligns one slit path to a macro–coherent domain with a different , the cross–term between the two path families involves when their tangent fields differ by , eliminating interference. This suppression is purely geometric in origin, as per the CFT account.

Appendix G.5. Interpretation

The formal restriction (

A33)–(

A37) makes precise the statement that “only

–compatible histories contribute”. It provides a calculable mechanism by which macroscopic causal alignment reduces the contributing history set, breaking phase links and reproducing the phenomenology of measurement without invoking nonlocal collapse [

43,

115].

Appendix H. Stability of the Emergent Chronon Field from Microscopic Dynamics

In

Section 2 and

Section 6, we treated the chronon field

as an emergent, coarse–grained order parameter built from microscopic “chronon” degrees of freedom, each carrying a local timelike orientation. Here we outline a simple block–spin style derivation showing how such a field can remain macroscopically coherent over long times, and how the

unit–norm property naturally appears as the minimum of the coarse–grained potential. This derivation should be viewed as heuristic: it motivates the postulate that

under coarse–graining, but does not constitute a general proof from the full

dynamics (see

Section 11).

Appendix H.1. Microscopic Chronon Model

We model the microscopic spacetime as discretized into cells of volume

, each containing a chronon with a timelike orientation vector

, where

n labels the cell. A minimal interaction Lagrangian is

where:

Appendix H.2. Coarse–Graining to a Field Theory

For a block of side

containing

chronons, define the coarse–grained field

Using standard spin–wave and gradient expansions [

23], the long–wavelength limit of Eq. (

A38) yields

with

and

.

The quartic term has a unique minimum at provided , so the unit–norm property emerges as the low–energy equilibrium condition of the coarse–grained theory. Whether this holds for all plausible microscopic dynamics remains to be established.

Appendix H.3. Linear Stability Analysis

Perturb around a uniform timelike background

with

and

. To quadratic order in

, Eq. (

A40) becomes

In flat space, the mode equation is

with dispersion relation

The stability conditions are therefore

Appendix H.4. Physical Interpretation

The microscopic coupling

sets

, the stiffness against spatial distortions of

. The curvature

of the local potential sets

, the restoring force toward unit norm. When both are positive, the emergent

is linearly stable, persistent, and timelike at scales

. The decay time for small perturbations is

which can be macroscopic if

J is large and

is modest.

Thus, under reasonable microscopic couplings, the coarse–grained behaves as a robust macro–coherent order parameter. However, the derivation here still assumes a specific form of the microscopic alignment potential; removing that assumption remains a key target for a general proof of emergent unit norm in CFT.

Appendix I. Emergent Planck Constant from Chronon Ensemble Statistics

In standard quantum theory, Planck’s constant

ℏ appears as a universal scale relating action and probability amplitudes [

37]. In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), where observables and evolution emerge from the statistical geometry of a fluctuating vector field

,

ℏ must itself be derived from more fundamental quantities. This appendix defines and motivates an emergent Planck scale

in CFT.

Appendix I.1. Chronon Ensemble and Gibbs Measure

Recall that chronon configurations are sampled from a Gibbs distribution of the form:

where

is an interaction energy functional and

controls the strength of fluctuations [

48,

95]. The variance of

within a domain

defines an effective action dispersion:

We define the emergent Planck constant as the action variance per chronon volume:

where

is the number of chronon degrees of freedom in the coarse-grained region of scale

.

Appendix I.2. Dimensional Estimate and Interpretation

Let

J be the typical coupling strength between chronons (dimension: energy) and

the microscopic time scale. Then a natural emergent action scale is:

If one identifies

and

, then:

consistent with known quantum dynamics [

74,