| Contents |

| |

|

1. |

Introduction.................................................................................................................................................................................................... |

2 |

| |

|

2. |

Dynamics of the Causal Alignment Field................................................................................................................................................... |

2 |

| |

|

3. |

Quantization as Holonomy........................................................................................................................................................................... |

3 |

| |

|

4. |

Measurement as Causal Synchronization................................................................................................................................................... |

5 |

| |

|

5. |

Relation to Existing Frameworks.................................................................................................................................................................. |

7 |

| |

|

6. |

Discussion and Outlook................................................................................................................................................................................. |

8 |

|

A. |

Dimensional Analysis and the Coherence Speed....................................................................................................................................... |

9 |

|

A.1. Conventions and Basic Dimensions....................................................................................................................................................... |

9 |

|

A.2. Dimensions of J and λ............................................................................................................................................................................ |

10 |

|

A.3. Effective Inertia χ and the Kinetic Normalization................................................................................................................................. |

10 |

|

A.4. Dispersion and the Coherence Speed..................................................................................................................................................... |

10 |

|

A.5. Natural Units and Consistency Checks................................................................................................................................................... |

11 |

|

B. |

Model of Causal Synchronization Dynamics................................................................................................................................................ |

11 |

|

B.1. Coupled Phase Dynamics........................................................................................................................................................................ |

11 |

|

B.2. Phase Locking and Probabilistic Alignment.......................................................................................................................................... |

11 |

|

B.3. Physical Interpretation.......................................................................................................................................................................... |

11 |

|

C. |

Geometric Derivation of the Action Quantum ћgeom............................................................................................................................. |

12 |

|

C.1. Phase–Only Reduction and Basic Scales................................................................................................................................................ |

12 |

|

C.2. Minimal 2π Soliton and Its Core Energy................................................................................................................................................. |

12 |

|

C.3. Action of a 2π Phase Slip and the Quantum of Action......................................................................................................................... |

13 |

|

C.4. Consistency Checks and Identification with ћ........................................................................................................................................ |

13 |

|

C.5. Relation to Holonomy Quantization........................................................................................................................................................ |

13 |

| |

|

D. References................................................................................................................................................................................................................. |

13 |

1. Introduction

In both classical and quantum physics, time enters as an external parameter rather than an internal dynamical quantity. In nonrelativistic quantum mechanics, the Schrödinger equation

describes unitary evolution in a preexisting temporal background [

12,

56], while in general relativity all events coexist within a four-dimensional Lorentzian manifold [

14,

38], producing a fundamentally static representation of reality. Neither framework accounts for the experiential fact that there exists a unique, ever-advancing “Now” or explains how causal progression is physically instantiated [

5,

50].

A variety of approaches have sought to fill this gap. The Wheeler–DeWitt equation attempts to formulate quantum gravity without an explicit time parameter, leading to the well-known “problem of time” [

11,

23,

28]. Pilot-wave theories, such as those of de Broglie and Bohm, introduce hidden trajectories guided by a wave function defined in configuration space [

8,

9,

22], yet they still rely on an external temporal coordinate. Stochastic mechanics interprets quantum evolution as diffusion in phase space [

17,

41], but similarly presupposes an ambient background time. In all such formulations, temporal order is assumed rather than derived.

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) offers an alternative foundation in which time and causal structure arise dynamically [

35,

36]. The basic variable is a vector field

that represents the local direction of time (causal alignment). Regions of high alignment correspond to coherent spacetime, while disordered regions correspond to pre-geometric or acausal domains. The field evolves according to a variational principle whose self-organization defines both geometry and temporality.

Within this framework, the passage of time corresponds to the propagation of a coherence front—the boundary separating ordered and disordered chronon domains. Quantization emerges from the topological properties of the causal curvature , whose discrete holonomies give rise to the action modulus . Measurement, in turn, is reinterpreted as the synchronization of causal phases between a system and its detector, transforming an indeterminate superposition into a coherent realized domain.

This paper develops the mathematical structure of this causal field theory in the quantum regime. We show that quantization, interference, and measurement arise as different manifestations of a single geometric mechanism—the alignment of causal flow. The resulting picture unifies temporal evolution and quantum discreteness within one continuous, covariant field framework, thereby providing a potential resolution of the “problem of the present” in modern physics.

2. Dynamics of the Causal Alignment Field

The central dynamical entity of Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is the

causal alignment field , a unit timelike vector field that encodes the local direction of causal flow. At each spacetime point, the orientation of

represents the dominant direction in which local microscopic chronon interactions align, establishing both temporal order and the emergent notion of simultaneity [

36]. Regions where

is coherent correspond to well-defined spacetime, whereas regions of random orientation correspond to pre-geometric, disordered phases in which no consistent causal order exists.

The dynamics of

are determined by the variational principle

where

J is the causal stiffness coefficient governing the energy cost of local misalignment, and

enforces the normalization constraint

through spontaneous symmetry breaking [

1,

30]. Variation of the action

yields the Euler–Lagrange field equation [

43]

The antisymmetric tensor

quantifies the local rotational misalignment of causal flow, analogous to a curvature or field-strength tensor [

38,

61]. When

, causal alignment is complete, and the region behaves as a flat Minkowski patch. Nonzero

signifies curvature of the causal manifold, representing the emergence of gravitational and quantum structure from local misalignment.

The first term in Eq. (

1) defines the kinetic energy associated with changes in causal orientation, while the potential term

stabilizes the unit-norm configuration. This structure parallels the Ginzburg–Landau form familiar from condensed matter theory [

18,

59], but with the order parameter interpreted causally rather than spatially. Hence, Eq. (

2) describes the relaxation of an initially disordered chronon ensemble toward coherent causal alignment.

Locally, the dynamics can be understood as a gradient flow that minimizes the causal distortion energy [

21,

44]. Linearization around a nearly aligned background yields a wave-like equation whose characteristic velocity

with

the effective inertia density of the medium, defines the maximum rate at which causal coherence can propagate. In the macroscopic limit, this propagation speed coincides with the invariant constant

c, so that the light cone of relativity corresponds to the natural limit of causal synchronization in the chronon field [

14]. See

Appendix A for details.

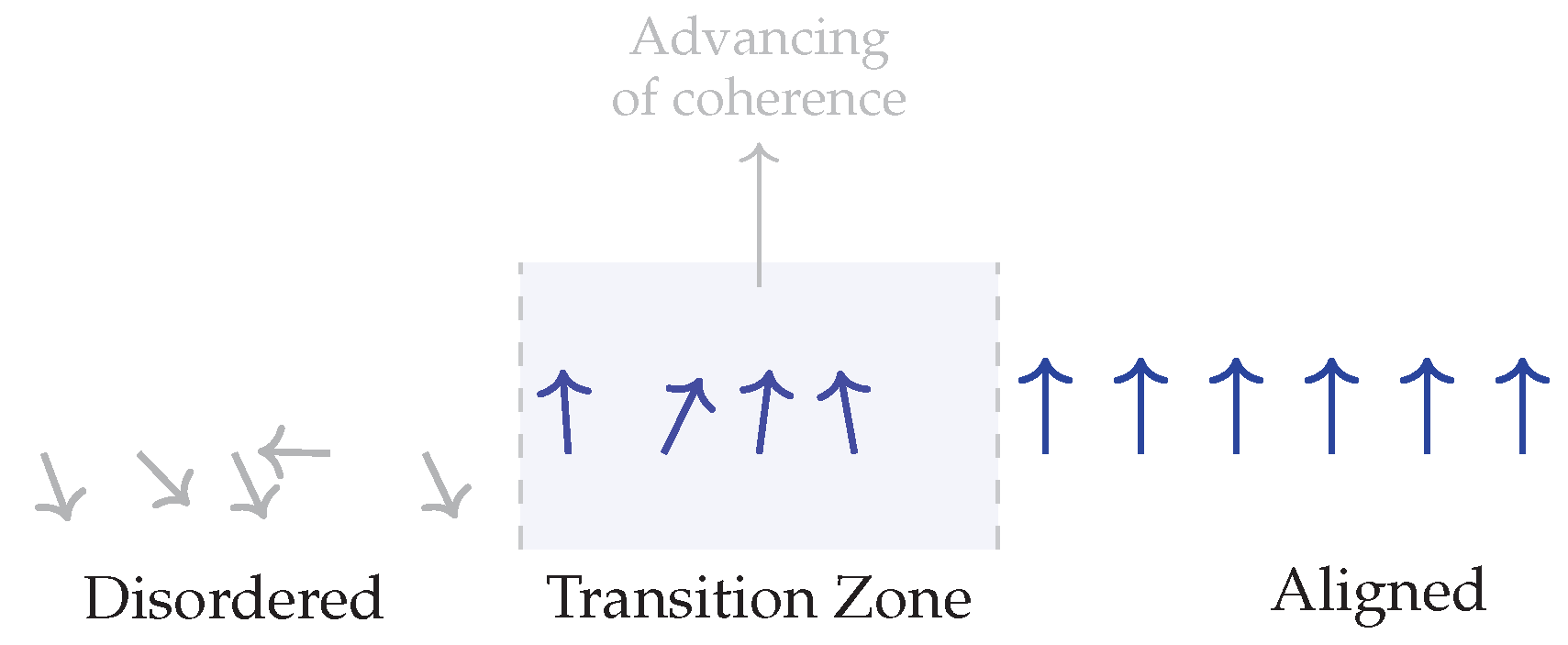

Figure 1.

Causal alignment. Random chronon orientations (left) interact through causal coupling, gradually aligning into coherent temporal flow (right). The shaded transition zone marks the advancing boundary of the “Now,” where disordered regions become causally synchronized.

Figure 1.

Causal alignment. Random chronon orientations (left) interact through causal coupling, gradually aligning into coherent temporal flow (right). The shaded transition zone marks the advancing boundary of the “Now,” where disordered regions become causally synchronized.

3. Quantization as Holonomy

In conventional quantum mechanics, discreteness of energy and action is introduced axiomatically through operator spectra or canonical commutation relations [

12,

32]. Within Chronon Field Theory (CFT), quantization instead emerges as a

topological property of the causal alignment field itself. The antisymmetric curvature tensor

measures the local rotational misalignment of causal flow and serves as a generalized field strength [

38,

61]. It encodes the infinitesimal deviation from perfect alignment of the causal direction

across neighboring regions.

Causal Phase and Holonomy

At each spacetime point, the orientation of

can be expressed in terms of a local

causal phase , defined so that infinitesimal rotations of

in the internal causal plane are generated by gradients of

:

Geometrically,

plays the role of an internal

-like phase angle describing the alignment of local causal orientation. Its circulation around a closed path measures the accumulated twist of the causal connection:

where

is any surface bounded by the loop

.

Quantization of causal curvature

Topological single-valuedness of the phase

requires that its circulation be quantized in integer multiples of

:

Using Eq. (

4), this implies quantization of the integrated causal curvature flux:

where

is a geometric constant with the dimensions of action, defining the minimal unit of causal rotation. Equation (

6) thus expresses the topological compactness of the causal manifold: each

rotation in causal phase carries a quantized flux of curvature through the corresponding surface.

An explicit derivation of

is provided in

Appendix C.

Physical Interpretation

A localized configuration in which the causal field completes one full rotation constitutes a topologically stable excitation of the chronon medium. Such excitations cannot be removed by continuous deformations; they can only be created or annihilated in quantized pairs when the local causal order becomes discontinuous. Each of these elementary excitations carries one unit of action , playing the role of an elementary quantum of the field.

This interpretation parallels quantized flux lines in superconductors [

37,

45] and quantized vortices in superfluids [

13], but with a crucial difference: here the quantized flux represents not electromagnetic or mechanical rotation, but the

fundamental circulation of causality itself. The chronon field therefore acts as a compact causal order parameter, and quantization arises from its topological structure rather than from any imposed operator algebra.

Emergence of Planck’s Constant

The existence of a finite geometric quantum of action ensures that the total phase-space circulation of any physical process is discrete in units of

. Standard quantum mechanics thus appears as the effective, coarse-grained limit of CFT dynamics, with the identification

Microscopic discreteness—of energy, angular momentum, and interference phases—therefore follows not from abstract postulates, but from the intrinsic topology of the causal connection [

7].

In this view, quantization is a manifestation of geometric holonomy: a direct consequence of the compact, orientable nature of causal space.

An explicit derivation of the geometric action quantum in terms of the CFT parameters

, yielding an approximate relation

, is provided in

Appendix C.

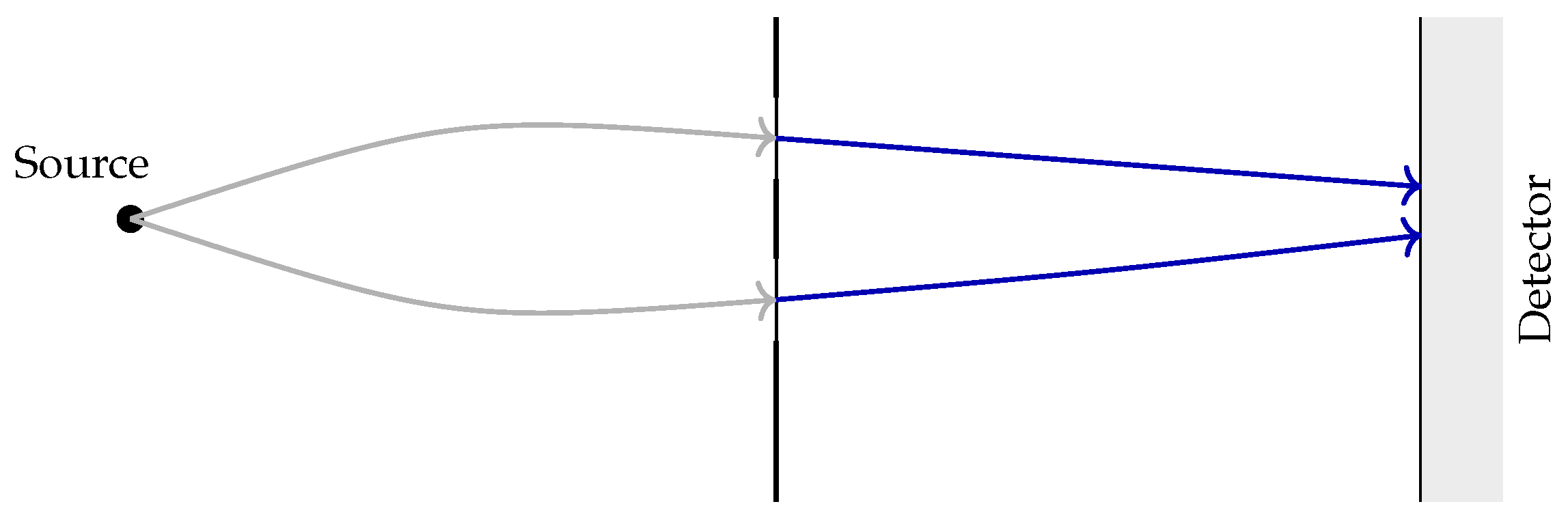

Figure 2.

Topological quantization. A complete twist of the chronon field’s internal phase corresponds to a closed loop in causal space. This loop carries a quantized flux of curvature equal to , the elementary unit of action. Topological stability of these twists gives rise to the discrete spectrum characteristic of quantum phenomena.

Figure 2.

Topological quantization. A complete twist of the chronon field’s internal phase corresponds to a closed loop in causal space. This loop carries a quantized flux of curvature equal to , the elementary unit of action. Topological stability of these twists gives rise to the discrete spectrum characteristic of quantum phenomena.

4. Measurement as Causal Synchronization

In conventional quantum mechanics, measurement introduces a formal discontinuity in unitary evolution: a system described by a superposition of states

is postulated to collapse probabilistically to one outcome through the projection rule [

12,

60]. Chronon Field Theory (CFT) replaces this non-dynamical postulate with a continuous, local process of

causal synchronization. A measurement corresponds to the mutual alignment of causal phases between an initially incoherent chronon region and a macroscopic coherent domain—the detector—whose causal orientation is already stabilized through large-scale phase locking.

Causal Alignment Between System and Detector

Let the local chronon field incident upon a detector be expressed as a superposition of orthogonal causal modes , each characterized by a distinct orientation of its internal phase relative to the detector’s reference phase . The detector itself is represented by a coherent reference field , whose phase defines the local causal frame. Interaction between the system and the detector enforces boundary conditions on the chronon field, driving the phase difference toward one of the stable minima of the local alignment potential. The degree of alignment determines the likelihood that a given mode will be entrained by the detector’s causal frame.

Emergence of the Born Rule from Alignment Bias

The probability that the detector stabilizes onto outcome

i is given by the relative alignment amplitude between the incoming mode and the detector’s coherent domain:

Equation (

8) reproduces the Born rule as an emergent expression of

phase-matching efficiency between causal domains [

55]. The inner product

quantifies the overlap of their causal phase distributions, measuring how effectively the incoming configuration can synchronize with the detector’s stabilized orientation. Normalization expresses the completeness of the synchronization basis: the total probability that alignment occurs with any available detector state is unity.

A quantitative formulation of this causal synchronization mechanism, based on coupled phase dynamics of the system and detector fields, is provided in

Appendix B, where the Born rule emerges as the steady-state distribution of phase locking.

Physical Picture: From Superposition to Realization

Before interaction, the chronon field contains a continuum of partially aligned domains, each representing a metastable causal bias. At the detector boundary, microscopic fluctuations induce nonlinear coupling between these domains and the detector’s macroscopic causal phase. When one subset of chronons achieves resonance (

modulo

), its alignment propagates throughout the local region, suppressing orthogonal components through destructive phase interference. This process constitutes an irreversible

locking of causal phase—the physical analogue of wavefunction collapse—arising from boundary-induced ordering rather than discontinuous projection. The mechanism is analogous to spontaneous symmetry breaking in condensed matter systems, where an external field selects one orientation among degenerate minima [

3,

34].

Causality and Locality of the Synchronization Process

Because synchronization spreads through the chronon medium via the causal alignment field

, the process is strictly local and respects relativistic causality. The apparent nonlocal correlations observed in entangled systems reflect the global constraints imposed by shared causal coherence, not superluminal influences [

4,

6]. The coherence front propagates at the invariant rate

which defines the maximal speed at which causal order can advance.

Thus, what is traditionally interpreted as instantaneous collapse is reinterpreted in CFT as a finite-speed propagation of causal synchronization across the chronon field. No physical entity is transmitted faster than light; only the coherence of causal orientation expands, realigning the chronon domains into a single realized configuration.

Measurement, in this view, is not a separate postulate of quantum theory but a particular mode of causal evolution: a synchronization event between microscopic and macroscopic domains within the same continuous causal field.

Double-Slit Experiment and Causal Synchronization

The double-slit experiment provides a clear illustration of how Chronon Field Theory (CFT) resolves the traditional wave–particle paradox. In CFT, the emission from a microscopic source generates a bundle of chronon threads—localized trajectories of causal flow—each carrying a causal phase that determines its orientation within the global alignment field . As these threads encounter a barrier with two slits, they propagate through both openings as bias-compatible channels of causal alignment. Between the slits and the detector, the chronon ensemble maintains a coherent phase relationship, and the interference pattern arises from the phase difference accumulated along each path. This is not a particle simultaneously traversing two routes, but a field-level superposition of causally correlated domains within a single, continuous medium.

When the chronon field interacts with the detector, the boundary conditions imposed by the detector’s coherent domain drive a rapid process of causal synchronization. One domain of the field achieves phase entrainment with the detector’s reference orientation, while all others decohere and lose causal connection. The resulting detection event thus corresponds to the emergence of a localized coherent region—the physical realization of one of the possible causal phases. The “collapse” of the wavefunction is therefore reinterpreted as a dynamical ordering transition in causal phase space, proceeding locally and continuously at the coherence propagation speed . In this way, the same causal mechanism explains both the extended wave-like interference and the discrete, particle-like detection events, without invoking dual ontologies or nonlocal collapse.

Figure 3.

Double-slit experiment in CFT. Chronon threads traverse both slits as causally coherent trajectories. Interference arises from their phase correlation, while measurement corresponds to phase synchronization with the detector’s causal frame—resolving the wave–particle duality dynamically.

Figure 3.

Double-slit experiment in CFT. Chronon threads traverse both slits as causally coherent trajectories. Interference arises from their phase correlation, while measurement corresponds to phase synchronization with the detector’s causal frame—resolving the wave–particle duality dynamically.

5. Relation to Existing Frameworks

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) retains the mathematical structure of standard quantum mechanics while providing it with a causal–geometric foundation. In this formulation, wavefunctions, operators, and probability amplitudes arise not as postulated entities but as effective descriptions of the underlying alignment dynamics of the chronon field

. The familiar Hilbert-space formalism corresponds to the linearized regime of small perturbations around a coherently aligned causal background, where local excitations of

obey an effective Schrödinger or Dirac-type evolution [

12,

62].

Comparison with Pilot-Wave Theory

In de Broglie–Bohm pilot-wave mechanics [

8,

10], particle trajectories are guided by a nonlocal quantum potential defined on configuration space. CFT differs fundamentally in ontology: it contains no hidden particles or guiding waves. Instead, the causal alignment field itself constitutes the physical substrate, and its local phase orientation encodes the information that the pilot-wave would otherwise carry. Apparent nonlocal correlations in quantum phenomena arise from global constraints on causal coherence [

6], not from instantaneous influences between spatially separated systems. The dynamics remain strictly local in the field

, propagating at the invariant coherence speed

c, consistent with relativistic causality [

4,

34].

Relation to Geometric Quantization and Gauge Theories

Geometric quantization introduces a symplectic structure on phase space by postulating the existence of a closed two-form [

26,

57]. CFT provides a deeper origin for this structure: the antisymmetric curvature

acts as the fundamental symplectic form, whose discrete flux integrals yield the quantization condition in Eq. (

6). Thus, the phase space of conventional quantum theory emerges dynamically as the space of allowed causal configurations, and the Planck constant appears as the minimal quantized flux of

rather than an external constant [

40].

Moreover, gauge interactions acquire a natural geometric interpretation. Parallel transport of the internal causal orientation within coherent domains generates compact holonomy groups that correspond to the familiar

,

, and

symmetries of the Standard Model [

61,

63]. In this sense, both quantization and gauge covariance arise from the same underlying mechanism—compact holonomy of the causal connection.

Summary

CFT thus unifies the predictive content of quantum mechanics and general relativity within a single causal–geometric field theory. It reproduces standard quantum behavior in the limit of small misalignment, recovers relativistic invariance from the universal coherence speed

c, and replaces measurement collapse with causal synchronization. The result is a framework that preserves empirical success while resolving the conceptual disjunction between dynamics, causality, and the physically advancing present [

47].

6. Discussion and Outlook

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) offers a unified causal–geometric foundation for quantum behavior, integrating quantization, interference, and measurement into a single dynamical mechanism. All three phenomena arise from the alignment and synchronization of local causal phases within the chronon field

. When chronon domains interact, their orientations adjust to minimize causal tension, producing discrete topological excitations whose circulation quantizes action in units of

. Interference emerges from the superposition of partially aligned domains, while measurement corresponds to the irreversible locking of one domain’s phase to a stable detector frame [

55].

The characteristic speed of this alignment process,

defines the invariant limit of causal propagation. The dimensional consistency of

J,

, and the derivation of

are summarized in

Appendix A.

It is important to emphasize that, this coherence speed represents an intrinsic causal rate, not the translation of objects through space.

In this framework, the constancy of the speed of light expresses a deeper physical principle: it is the maximal rate at which causal coherence can advance through the universe. Relativistic invariance, quantum discreteness, and the presence of a globally advancing “Now” are not independent postulates but self-consistent aspects of the same causal substrate. The “light cone” of relativity corresponds to the boundary of causal synchronization, and Planck’s constant reflects the quantized holonomy of that same field structure.

Beyond the microscopic regime, CFT suggests a new perspective on macroscopic decoherence and cosmology. Large systems may be described as networks of partially synchronized chronon domains, whose collective dynamics reproduce the transition from quantum superposition to classical determinacy [

24,

65]. At the cosmological scale, the same causal alignment process that governs microscopic coherence could underlie the growth of spacetime itself, with the advancing front of causal synchronization corresponding to the expansion of the universe [

15,

46]. Exploring whether large-scale curvature, entropy gradients, or matter inhomogeneities affect the global coherence rate may provide new observational links between quantum foundations and cosmological evolution.

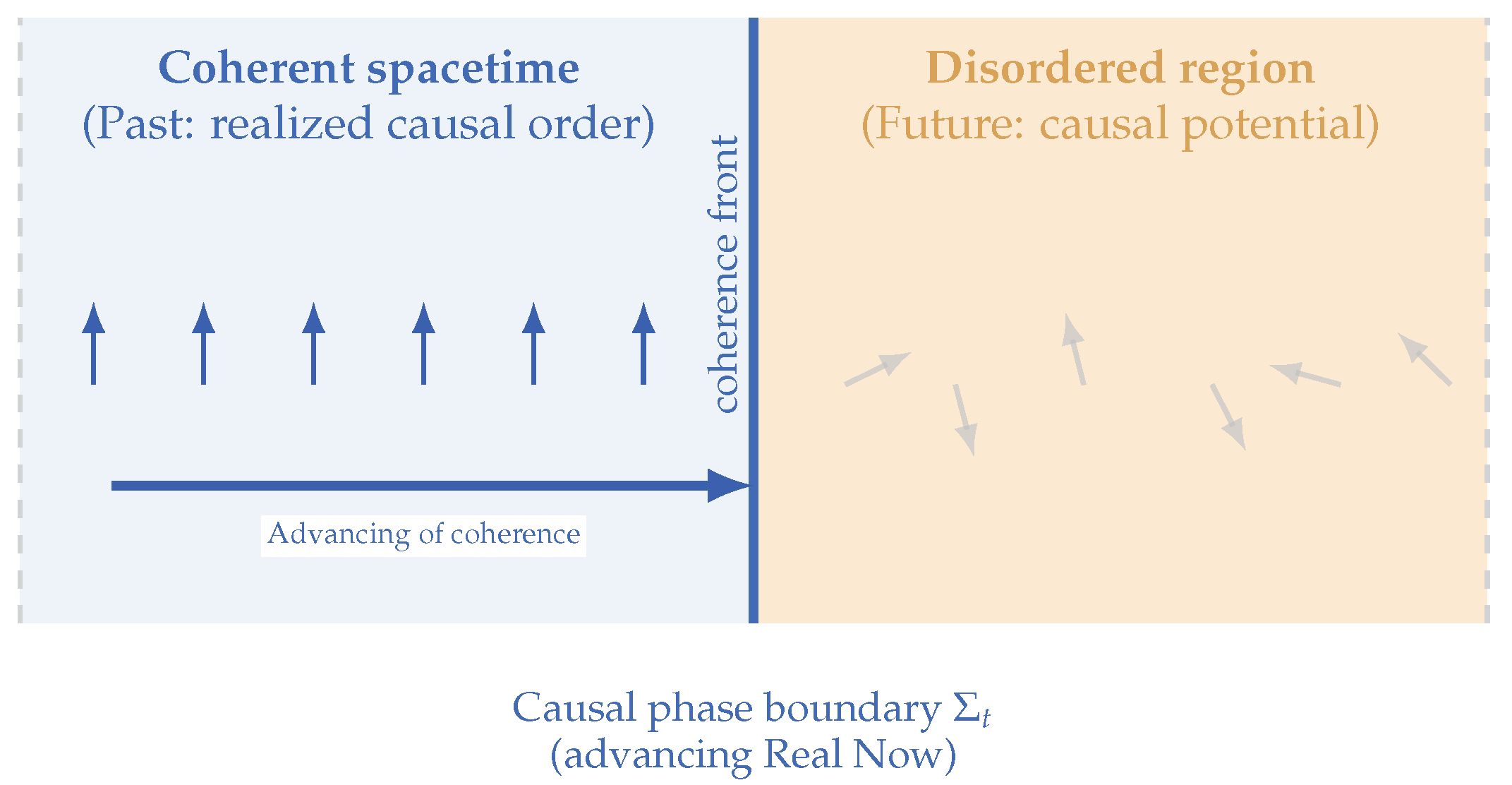

Figure 4.

Advancing of coherence as the physical frontier of the Real Now. The coherent past (left) consists of chronons already aligned into stable causal order—realized spacetime. The disordered future (right) contains incoherent chronons representing unrealized potential. The thick boundary marks the physically real Now, the advancing front of causal coherence. The arrow shows the direction in which coherence propagates; this advancing of coherence constitutes the physical process underlying the advancing of the Real Now.

Figure 4.

Advancing of coherence as the physical frontier of the Real Now. The coherent past (left) consists of chronons already aligned into stable causal order—realized spacetime. The disordered future (right) contains incoherent chronons representing unrealized potential. The thick boundary marks the physically real Now, the advancing front of causal coherence. The arrow shows the direction in which coherence propagates; this advancing of coherence constitutes the physical process underlying the advancing of the Real Now.

Reconstruction of Reality at the Advancing Frontier

Importantly, observers, matter, and all physical structures move with the advancing front of coherence rather than being left behind. Our bodies, memories, and instruments are composed of chronons already entrained within the coherent domain; as the causal boundary advances, the configuration of aligned chronons that defines “us” is continuously reconstructed at the new frontier of coherence. The flow of time therefore does not carry the universe forward through an external parameter—it recreates the universe, moment by moment, at the advancing causal boundary.

From this perspective, all physical evolution is a manifestation of the continual reconstruction of reality at the coherence front. What physics describes as “change”—motion, interaction, decay, and emergence—is precisely this ongoing renewal of causal alignment. The laws of dynamics govern how patterns of coherence are replicated and transformed as the boundary advances. In this sense, Chronon Field Theory reformulates the very aim of physics: to describe the lawful structure of this self-generating process by which the universe reconstitutes its own reality at every instant.

Future work will focus on three main directions:

Developing a full dynamical theory of causal front propagation, including nonlinear stability analysis and entropy production;

Extending the framework to multipartite and entangled systems, formulating measurement as a network of coupled synchronization processes;

Extending the framework to cosmology, where the observed expansion and apparent acceleration of the universe emerge from the advancing chronon–coherence front, whose global dynamics determine the cosmic coherence rate and the growth of spacetime itself.

By grounding quantum mechanics and relativity in the same causal order parameter, CFT restores temporal becoming to physics: the universe is not a static block but a self-organizing process that continuously extends its own coherence—a universe in which time itself is the ongoing advance of causal order [

47,

51].

Data Availability Statement

This study is purely theoretical and does not involve any experimental data. All equations, derivations, and figures are original to the author and are fully contained within the manuscript. No external datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no known financial or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The research was conducted independently and received no specific funding from any agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix A. Dimensional Analysis and the Coherence Speed

Appendix A.1. Conventions and Basic Dimensions

We keep

c and

ℏ explicit throughout. The action is

with dimension

[

31,

62]. Thus, the Lagrangian density has dimension

The chronon field satisfies the unit–timelike constraint

, so it is dimensionless:

Covariant derivatives carry the usual dimensions

Appendix A.2. Dimensions of J and λ

From

the gradient term scales as

. Matching dimensions with

yields

The quartic potential is dimensionless in

, so

These assignments parallel the stiffness and self–coupling in Landau–Ginzburg or nonlinear sigma models [

31,

64].

SI units (for reference).

With

and

L in meters,

Because

represents an action density,

yields an energy density.

Appendix A.3. Effective Inertia χ and the Kinetic Normalization

For small, time–dependent perturbations about an aligned background

with

, we introduce a positive susceptibility

so that the linearized dynamics take the canonical hyperbolic form, analogous to elasticity or field propagation [

20,

62]:

where

is transverse to

and

collects local restoring terms (from the potential curvature). Dimensionally,

Hence

has the dimensions of a

speed squared, analogous to

in elastic media.

Appendix A.4. Dispersion and the Coherence Speed

Inserting a plane wave

into Eq. (

A1) gives

On the (approximately) massless branch or at long wavelengths (

with

a correlation length), the dispersion is linear:

Thus, the characteristic

coherence speed is

with the correct dimensions of velocity. Identifying the emergent causal cone with the relativistic light cone yields the macroscopic equivalence

as proposed in the main text.

Appendix A.5. Natural Units and Consistency Checks

In natural units

,

,

,

, and

. Equation (

A2) reduces to

, which is dimensionless and bounded by unity in the relativistic limit. Restoring

c and

ℏ confirms

, so that

in fully coherent domains.

Summary. With

dimensionless, the stiffness

J carries dimensions of action per area, while the susceptibility

represents an effective inertia density. Their ratio fixes the causal kinematic scale:

identifying the invariant speed of causal synchronization with the relativistic constant

c in the macroscopic coherent limit.

Appendix B. Model of Causal Synchronization Dynamics

Appendix B.1. Coupled Phase Dynamics

Let

and

denote the local causal phases of the system and detector domains, each defined through the alignment field

. Interaction at their boundary introduces a coupling potential analogous to a Kuramoto-type phase-locking term [

29,

58]:

where

measures the strength of causal coupling. Linearizing the Euler–Lagrange equation (

2) for small phase deviations yields the local evolution law

where

is an effective damping rate induced by the detector’s macroscopic coherence, and

and

J are the same inertial and stiffness coefficients introduced in the main text. Equation (

A3) is structurally similar to the damped sine–Gordon or Josephson junction equation [

54], but here it governs the causal phase

rather than an electromagnetic or mechanical variable.

Appendix B.2. Phase Locking and Probabilistic Alignment

Equation (

A3) admits stable fixed points when

, corresponding to fully synchronized causal domains. The probability for a given mode

i to lock onto the detector’s phase is proportional to the squared overlap of their complex amplitudes,

which recovers the Born rule, Eq. (

8), as the steady-state distribution of phase alignment [

55,

65]. Small fluctuations about the locked state decay on a timescale

, so synchronization is effectively instantaneous on laboratory scales but remains causal, limited by

.

Appendix B.3. Physical Interpretation

The detector acts as an attractor in the causal-phase manifold: its macroscopic alignment suppresses incompatible orientations, driving the microscopic chronon modes toward the nearest phase-matched basin. The apparent “collapse” of the wavefunction thus corresponds to reaching a stable fixed point of the coupled phase dynamics, not a non-physical projection [

3,

34]. This synchronization model renders

Section 4 mathematically explicit and clarifies how the Born rule emerges from deterministic causal alignment rather than stochastic postulation. It also links the microscopic mechanism of measurement to general principles of phase-locking and self-organized synchronization ubiquitous in nonlinear physical systems [

48].

Appendix C. Geometric Derivation of the Action Quantum

ℏgeom

Appendix C.1. Phase–Only Reduction and Basic Scales

Starting from the CFT Lagrangian

we consider the aligned phase where the unit–timelike constraint

is enforced by

. On stabilized domains, slow rotations of the causal orientation can be parametrized by a scalar phase

so that transverse reorientations are captured by gradients of

. To quadratic order, the effective phase–only Lagrangian takes the Goldstone form [

19,

33]

whose dispersion

gives

This velocity represents the intrinsic rate of causal alignment, not the translation of matter or information through space.

The core potential accounts for short–distance relaxation when the phase winds non-trivially, analogous to amplitude suppression in Ginzburg–Landau vortices.

Balancing gradient and core energies yields the correlation (core) length

and the associated coherence (front) time

Appendix C.2. Minimal 2π Soliton and Its Core Energy

A minimal topological excitation corresponds to a

phase winding around a line defect (the worldsheet of a pointlike soliton in

D). For

, the phase profile is

, giving

. The gradient energy density

yields the logarithmic contribution per unit length [

27,

42]

Amplitude relaxation within the core removes the

divergence, producing a finite energy [

13]:

For a closed minimal loop of length

, the total energy becomes

where

absorbs finite-size and core effects.

Appendix C.3. Action of a 2π Phase Slip and the Quantum of Action

The minimal action required to realize a

twist equals the energy of the minimal soliton times the coherence time [

52]:

Using

and

from Eqs. (

A5)–(

A6),

with

capturing geometric factors. A full

causal winding therefore defines one quantum of holonomy (Sec.

3),

The action quantum is thus completely fixed by the intrinsic CFT parameters

.

Appendix C.4. Consistency Checks and Identification with

ℏ

Dimensions.

Since , , and , it follows that , confirming dimensional consistency.

Scaling with coherence parameters.

Using

and

, Eq. (

A13) can be rewritten as

, i.e. energy of the minimal core multiplied by its formation time, consistent with the physical interpretation of an action quantum.

Identification.

In the coarse-grained quantum limit,

Both

ℏ and

c therefore emerge from the same microscopic parameters, linking quantum discreteness and relativistic causality within one unified causal–geometric substrate.

Appendix C.5. Relation to Holonomy Quantization

Section 3 established the topological condition

Equation (

A13) shows that this holonomy quantum equals the minimal action required to generate a

causal twist, tying its magnitude directly to the stiffness

J, susceptibility

(via

c), and constraint strength

. Thus the quanta of action and the invariant causal speed are

joint emergent invariants of the chronon medium, analogous to how flux quanta and sound velocity arise together in condensed-matter analogs [

2,

39]

References

- P. W. Anderson, “Plasmons, Gauge Invariance, and Mass,” Phys. Rev., vol. 130, pp. 439–442, 1963.

- P. W. Anderson, Considerations on the flow of superfluid helium, Rev. Mod. Phys. 38, 298–310 (1966).

- P. W. Anderson, “More is Different: Broken Symmetry and the Nature of the Hierarchical Structure of Science,” Science, vol. 177, pp. 393–396, 1972.

- A. Aspect, J. Dalibard, and G. Roger, “Experimental Test of Bell’s Inequalities Using Time-Varying Analyzers,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 49, pp. 1804–1807, 1982.

- J. Barbour, The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Physics, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- J. S. Bell, “On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox,” Physics, vol. 1, pp. 195–200, 1964.

- M. V. Berry, “Quantal Phase Factors Accompanying Adiabatic Changes,” Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A, vol. 392, pp. 45–57, 1984.

- D. Bohm, “A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of Hidden Variables, I and II,” Phys. Rev., vol. 85, pp. 166–193, 1952.

- L. de Broglie, “La mécanique ondulatoire et la structure atomique de la matière et du rayonnement,” J. Phys. Radium, vol. 8, pp. 225–241, 1927.

- L. de Broglie, “La nouvelle dynamique des quanta,” Comptes Rendus, vol. 185, pp. 380–382, 1928.

- B. S. DeWitt, “Quantum Theory of Gravity. I. The Canonical Theory,” Phys. Rev., vol. 160, no. 5, pp. 1113–1148, 1967.

- P. A. M. Dirac, The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, Oxford University Press, 1930.

- R. J. Donnelly, Quantized Vortices in Helium II, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- A. Einstein, “Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation,” Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 844–847, 1915.

- G. F. R. Ellis, “Physics in the Real Universe: Time and Spacetime,” Gen. Rel. Grav., vol. 50, no. 10, 2018.

- R. P. Feynman, “Space–Time Approach to Non-Relativistic Quantum Mechanics,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 20, pp. 367–387, 1948.

- L. Fritsche and M. Haugk, “A New Look at the Derivation of the Schrödinger Equation from Newtonian Mechanics,” Ann. Phys. (Leipzig), vol. 11, pp. 943–982, 2002.

- V. L. Ginzburg and L. D. Landau, “On the Theory of Superconductivity,” Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz., vol. 20, pp. 1064–1082, 1950.

- J. Goldstone, Field theories with “superconductor” solutions, Nuovo Cim. 19, 154–164 (1961).

- J. Goldstone, A. Salam, and S. Weinberg, “Broken Symmetries,” Phys. Rev., vol. 127, pp. 965–970, 1962.

- B. I. Halperin and P. C. Hohenberg, “Theory of Dynamic Critical Phenomena,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 49, pp. 435–479, 1977.

- P. R. Holland, The Quantum Theory of Motion: An Account of the de Broglie–Bohm Causal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- C. J. Isham, “Canonical Quantum Gravity and the Problem of Time,” in Integrable Systems, Quantum Groups, and Quantum Field Theories, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1992.

- E. Joos and H. D. Zeh, “The Emergence of Classical Properties Through Interaction with the Environment,” Z. Phys. B, vol. 59, pp. 223–243, 1985.

- C. Kiefer, Quantum Gravity, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2007.

- B. Kostant, “Quantization and Unitary Representations,” in Lectures in Modern Analysis and Applications III, Springer, 1970.

- J. M. Kosterlitz and D. J. Thouless, Ordering, metastability and phase transitions in two-dimensional systems, J. Phys. C 6, 1181 (1973).

- K. V. Kuchař, “Time and Interpretations of Quantum Gravity,” Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, vol. 20, pp. 3–86, 2011.

- Y. Kuramoto, Self-entrainment of a population of coupled nonlinear oscillators, in International Symposium on Mathematical Problems in Theoretical Physics, Lecture Notes in Physics, vol. 39, Springer, New York (1975), pp. 420–422.

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Statistical Physics, Pergamon, 1958.

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Statistical Physics, Part 1, Pergamon Press, 1980.

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory, Pergamon, 3rd ed., 1977.

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Statistical Physics, Part 1, 3rd ed., Pergamon, Oxford (1980).

- A. J. Leggett, “Macroscopic Quantum Systems and the Quantum Theory of Measurement,” Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl., vol. 69, pp. 80–100, 1980.

- B. Li, “Emergent Gravity and Gauge Interactions from a Dynamical Temporal Field,” Rep. Adv. Phys. Sci. 9, 2550017 (2025). [CrossRef]

- B. Li, “Emergence and Exclusivity of Lorentzian Signature and Unit–Norm Time from Random Chronon Dynamics,” Rep. Adv. Phys. Sci., accepted on September 25, 2025 (2025). In press soon with DOI: S2424942425500227.

- F. London, Superfluids, Vol. I: Macroscopic Theory of Superconductivity, Wiley, 1950.

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne, and J. A. Wheeler, Gravitation, W. H. Freeman, 1973.

- F. R. N. Nabarro, Theory of Crystal Dislocations, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1967).

- M. Nakahara, Geometry, Topology and Physics, 2nd ed., Taylor & Francis, 2003.

- E. Nelson, “Derivation of the Schrödinger Equation from Newtonian Mechanics,” Phys. Rev., vol. 150, pp. 1079–1085, 1966.

- H. B. Nielsen and P. Olesen, Vortex-line models for dual strings, Nucl. Phys. B 61, 45–61 (1973).

- E. Noether, “Invariante Variationsprobleme,” Nachr. König. Ges. Wiss. Göttingen, pp. 235–257, 1918.

- L. Onsager, “Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes I–II,” Phys. Rev., vol. 37, pp. 405–426, 1931.

- L. Onsager, “Magnetic Flux Through a Superconducting Ring,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 7, p. 50, 1959.

- T. Padmanabhan, Sleeping Beauties in Theoretical Physics: 26 Surprising Insights, Springer, 2017.

- R. Penrose, The Emperor’s New Mind, Oxford University Press, 1989.

- A. Pikovsky, M. Rosenblum, and J. Kurths, Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2001).

- M. Planck, “On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum,” Annalen der Physik, vol. 4, pp. 553–563, 1901.

- H. Price, Time’s Arrow and Archimedes’ Point, Oxford University Press, 1996.

- I. Prigogine, From Being to Becoming: Time and Complexity in the Physical Sciences, W. H. Freeman, 1980.

- R. Rajaraman, Solitons and Instantons, North-Holland, Amsterdam (1982).

- M. Schlosshauer, Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition, Springer, 2007.

- A. C. Scott, Active and Nonlinear Wave Propagation in Electronics, Wiley, New York (1970).

- M. Schlosshauer, Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition, Springer, Berlin (2007).

- E. Schrödinger, “Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem,” Annalen der Physik, vol. 79, pp. 361–376, 1926.

- J. M. Souriau, Structure of Dynamical Systems: A Symplectic View of Physics, Birkhäuser, 1997.

- S. H. Strogatz, From Kuramoto to Crawford: exploring the onset of synchronization in populations of coupled oscillators, Physica D 143, 1–20 (2000).

- M. Tinkham, Introduction to Superconductivity, 2nd ed., Dover, 2004.

- J. von Neumann, Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton University Press, 1932.

- S. Weinberg, Gravitation and Cosmology: Principles and Applications of the General Theory of Relativity, Wiley, 1972.

- S. Weinberg, The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 1: Foundations, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- C. N. Yang and R. L. Mills, “Conservation of Isotopic Spin and Isotopic Gauge Invariance,” Phys. Rev., vol. 96, pp. 191–195, 1954.

- J. Zinn-Justin, Quantum Field Theory and Critical Phenomena, 4th ed., Oxford University Press, 2002.

- W. H. Zurek, “Decoherence, Einselection, and the Quantum Origins of the Classical,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 75, pp. 715–775, 2003.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).