1. Introduction

Unifying quantum mechanics and general relativity remains one of the most profound challenges in theoretical physics. While quantum theory is built upon probabilistic dynamics in a fixed spacetime background, general relativity treats spacetime itself as a dynamical entity governed by the Einstein field equations. This tension becomes especially acute in regimes of strong curvature, such as black hole interiors and the early universe, where a consistent theory of quantum gravity is indispensable.

A major conceptual barrier to such a unification is the treatment of time. In standard quantum theory, time is an external parameter, an absolute classical variable that orchestrates the evolution of quantum states. In contrast, general relativity regards time as a coordinate subject to diffeomorphism invariance, with no privileged role. The resulting tension gives rise to the so-called

problem of time [

4,

37,

40], which plagues canonical quantizations of gravity such as the Wheeler–DeWitt framework. These approaches often yield a “frozen formalism,” in which the wavefunctional of the universe appears static, challenging any straightforward interpretation of dynamical evolution.

Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG) offers a radical departure from these conventions. It is grounded in

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) [

43], which postulates that time is not merely a coordinate or external parameter but a physical, dynamical field—a smooth, unit-norm, future-directed timelike vector field

defined on a Lorentzian manifold. This field, termed the

Chronon field, encodes local temporal flow and induces a preferred foliation of spacetime into spatial hypersurfaces orthogonal to

. The orientation and topological structure of this field define causal cones, temporal ordering, and the global arrow of time. Crucially, all observed physical phenomena—including matter fields, gravitational interactions, and quantum behavior—are understood as emergent from the evolution and topology of

.

Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG) is formulated as a background-independent, quantizable, and topologically regularized theory of gravity. Unlike approaches that attempt to quantize geometry directly, CQG treats geometry as emergent from the quantum dynamics of temporal flow. The theory is founded on a constrained vector field Lagrangian with intrinsic topological structure, permitting a well-defined quantization procedure that avoids the pathologies of non-renormalizability and background dependence.

In this paper, we develop the theoretical foundations of CQG and demonstrate its capacity to address key challenges in quantum gravity. We construct a Chronon-adapted Wheeler–DeWitt equation that resolves the frozen time problem. We show that General Relativity emerges in the classical limit as a large-scale manifestation of Chronon alignment. We propose a topological definition of black hole entropy derived from winding numbers of and present a concrete numerical simulation scheme to study the emergence of spacetime and entropy from a disordered temporal substrate. In doing so, CQG offers a coherent, predictive, and empirically accessible framework that reinterprets spacetime, matter, and quantum evolution as manifestations of a deeper temporal ontology.

2. Chronon Field and Quantization

2.1. Fundamentals of the Chronon Field

At the heart of Chronon Quantum Gravity lies the Chronon field

, a smooth, future-directed, timelike unit vector field defined on a Lorentzian manifold

. This field is postulated to be a physical entity, rather than a gauge choice or coordinate artifact, and satisfies the normalization condition

The condition

ensures that

defines a globally consistent arrow of time. The integral curves of

constitute a congruence of timelike worldlines that foliate spacetime into a family of spatial hypersurfaces

, orthogonal to

. These surfaces provide a natural slicing of spacetime that serves as the framework for defining quantum dynamics and causal structure [

60,

72].

Given this temporal foliation, we define an effective metric tensor that encodes the backreaction of

on spacetime geometry:

where

is the background Minkowski metric (or an initial classical spacetime metric), and

is a small coupling parameter controlling the magnitude of temporal backreaction. In highly coherent regions,

can be interpreted as an emergent spacetime geometry induced by the dynamical alignment of temporal flow. In this way, gravitational phenomena emerge not from quantizing geometry directly, but from the evolution and coherent alignment of the Chronon field itself [

9,

51].

2.2. Action and Path Integral Formulation

To define the dynamics of

, we construct a Lorentz-invariant action functional composed of kinetic, constraint, and topological terms. The proposed Chronon Quantum Gravity action is given by

where

is the antisymmetric field strength tensor, and

is a Lagrange-type potential enforcing the unit-norm constraint on

. The term

encodes the topological sector structure of the Chronon field, including contributions from winding number densities, domain wall tensions, and solitonic invariants such as Chern–Simons-like or

charges [

8,

35]. These structures are essential for modeling particle content, causal domain walls, and entropy-carrying defects [

24,

67].

To promote this theory to a quantum framework, we employ a path integral over the configuration space of Chronon fields, integrating over all field configurations that satisfy the normalization and causal orientation conditions:

where the

-function enforces the unit-norm constraint, and

ensures that the field is future-directed. The measure

is taken over all smooth, causally consistent vector fields on the spacetime manifold.

This functional integral defines the quantum dynamics of spacetime and matter in CQG. Crucially, the resulting theory is manifestly background-independent: the temporal structure is not fixed a priori, but dynamically generated [

45,

65]. Moreover, the presence of topological terms provides a natural mechanism for regularization and intrinsic finiteness, potentially circumventing the ultraviolet divergences that plague other quantum gravity approaches [

20,

74].

The formal structure of the theory resembles that of a generalized non-Abelian gauge theory, but with crucial differences:

is not a gauge field in internal space, but a physical field encoding spacetime temporal flow. The corresponding observables are not Wilson loops or curvature invariants, but quantities such as causal shear, winding number, and soliton content—all derived from the topology of temporal coherence [

47,

69].

In the sections that follow, we show that this structure gives rise to effective gravitational dynamics, resolves key issues in canonical quantum gravity, and supports a coherent picture of emergent spacetime.

3. Emergent Gravity and Recovery of General Relativity

In Chronon Quantum Gravity, spacetime geometry is not fundamental but arises dynamically from the coherent alignment of the Chronon field

. In regions where

exhibits large-scale coherence—as expected following the cosmological phase transition described in CPTC [

42]—an effective metric is induced by the Chronon configuration [

10,

36]:

where

is an auxiliary background metric introduced for variational analysis, and

is a small parameter characterizing the strength of temporal backreaction. This effective metric governs causal propagation and geodesic motion for matter and light, which respond to the dynamically evolving structure of

rather than a fixed background [

12,

39].

To derive the emergent gravitational dynamics, we begin with the Chronon action:

where

is the antisymmetric field strength,

V is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing the unit-norm condition

, and

includes topological terms such as winding numbers and solitonic contributions [

8,

35].

The stress-energy tensor is derived by varying the action with respect to the background metric

:

This tensor captures contributions from both the kinetic dynamics of

and its nontrivial topological sector. As

approaches a classical configuration in a semi-coherent phase, one can define the Einstein tensor from the effective metric

. We then obtain the emergent Einstein field equations in the form:

where

is the Einstein tensor constructed from

. This result shows that General Relativity is not a fundamental input, but rather emerges as the large-scale, low-curvature limit of Chronon field dynamics. The subleading corrections

encode deviations from classical GR, which are potentially observable in strong-field regimes such as black hole interiors, early-universe cosmology, and gravitational wave backgrounds [

6,

55].

This emergent gravity framework demonstrates how coherent temporal flow, encoded by a quantized field, can give rise to classical geometric structures—thereby unifying causal structure, gravitational dynamics, and topological matter content in a single field-theoretic setting [

52,

71].

4. Chronon Wheeler–DeWitt Equation

In canonical approaches to quantum gravity, the Wheeler–DeWitt equation imposes a Hamiltonian constraint on the universal wavefunctional:

where

is the spatial 3-metric on a spatial hypersurface

, and

denotes matter fields. This equation arises from the ADM decomposition of general relativity, where the Hamiltonian vanishes due to diffeomorphism invariance [

1,

17]. However, it famously suffers from the “problem of time,” since it lacks any explicit or intrinsic temporal parameter. As a result, the wavefunctional

appears static, with no clear interpretation of dynamical evolution [

37,

41].

Chronon Quantum Gravity addresses this issue by promoting time to a physical, dynamical field: the Chronon field

. The integral curves of

define a preferred global foliation of spacetime into spatial hypersurfaces

orthogonal to

, where

is the proper time along these integral curves. This structure allows for a relational and intrinsic definition of time within a background-independent setting [

60,

65].

To formulate the quantum theory, we construct a canonical Hamiltonian framework adapted to this foliation. Let

and

denote the spatial components of the Chronon field and their conjugate momenta on each hypersurface

. The Chronon Hamiltonian is then defined as:

where

includes kinetic contributions from

, constraint enforcement terms ensuring

, and topological interactions such as solitonic winding densities [

8,

35].

Quantization proceeds by promoting the canonical variables to operators on a Hilbert space of wavefunctionals

, defined over the configuration space of

on each

. The conjugate momenta act as functional derivatives:

The resulting Schrödinger-like equation in Chronon proper time

reads:

where

is the quantum Chronon Hamiltonian operator acting on the field configurations restricted to

.

This formulation restores unitary temporal evolution in quantum gravity by internalizing the flow of time via the Chronon field itself. Unlike standard canonical quantum gravity, where time is external or absent, here evolution is defined intrinsically along the physical foliation determined by

. Observables must be defined relationally, as functionals conditioned on configurations of

, thereby satisfying the requirements of background independence and offering a resolution to the frozen formalism problem [

19,

63].

This Chronon-adapted Wheeler–DeWitt framework also enables the construction of semiclassical limits, time-dependent decoherence, and causal histories explicitly tied to the structure of emergent spacetime geometry [

15,

22]. Future work will explore its consequences for quantum cosmology, black hole interiors, and the quantum-to-classical transition in temporally structured spacetimes.

5. Black Hole Entropy and Chronon Topology

Black hole thermodynamics remains one of the most compelling clues toward a consistent quantum theory of gravity. The Bekenstein–Hawking entropy formula,

where

A is the area of the event horizon, implies that black hole entropy scales with surface area rather than volume, hinting at a holographic character of gravitational degrees of freedom [

11,

31,

70]. However, standard approaches lack a universally accepted microscopic derivation of this entropy in terms of quantized, local field-theoretic entities [

38,

66].

In Chronon Quantum Gravity, entropy arises naturally from the topological sector structure of the Chronon field

near the event horizon. The Chronon field, being a smooth unit-timelike vector field constrained by

, admits nontrivial topological configurations classified by the homotopy group

[

8,

49]. These configurations correspond to solitonic winding modes of

around the horizon 2-surface, stabilized by the field’s normalization and global orientation.

We define the local

winding density as:

where

is the unit normal to the horizon foliation

, and

is a normalization factor fixed by the topological charge quantization condition. This expression is a local analog of the Hopf invariant and captures the density of topologically distinct configurations of

threading the black hole horizon [

35,

57].

The total black hole entropy is then obtained by integrating the winding density over the induced spatial measure on the horizon:

where

is a universal constant set by the Chronon field coupling strength, topological normalization, and fundamental constants. Matching this expression to the Bekenstein–Hawking formula fixes

in terms of

ℏ,

G, and

.

This formulation provides a geometric and statistical basis for black hole entropy: it counts the number of topologically inequivalent Chronon field configurations consistent with the horizon’s causal structure. Unlike models based on string excitations or horizon microstates, CQG interprets entropy as an emergent feature of quantized temporal topology. The unit-norm and future-directed constraints ensure that only causal, stable topological sectors contribute [

7,

61].

Furthermore, this approach predicts the possibility of

quantized fluctuations in entropy during dynamical processes such as black hole mergers or near-extremal transitions, where changes in the topological charge of

across

can occur. These may manifest as discrete entropy steps or modulations in gravitational wave signals, offering potential observational signatures of Chronon topology in strong-field regimes [

16,

23].

The topological entropy model proposed here thus unifies geometry, thermodynamics, and quantum field dynamics in a background-independent framework. It points toward a non-holographic yet inherently quantum-topological structure for spacetime, wherein entropy arises from the quantized degrees of freedom of temporal flow itself.

Surface vs. Volume Entropy: Why the Horizon Counts

Although the Chronon field spans the full black hole interior, entropy in CQG arises from its topological behavior at the boundary—the horizon surface . This is not an imposed holographic principle but follows from the structure of the topological invariant: winding sectors classified by are distinguished by how wraps across the horizon, and only transitions through the surface can alter this topological charge.

This is analogous to topological field theories, such as Chern–Simons, where physical data localize on boundaries. It reflects the physical principle that black hole entropy encodes information inaccessible to external observers, carried by causal, topologically distinct configurations crossing the horizon.

Thus, CQG aligns with the area law through a boundary-based count of quantized temporal sectors, offering a geometric and statistical interpretation of black hole entropy. It further predicts

quantized entropy fluctuations in dynamical processes like mergers or extremal transitions, where changes in Chronon topology across

may yield discrete entropy steps or observable imprints in gravitational wave data [

16,

23].

This framework unifies thermodynamics, geometry, and quantum topology without invoking holography, grounding entropy in the causal, quantized structure of temporal flow itself.

6. Numerical Simulation of Chronon Field Dynamics

To provide empirical support for Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG), we performed a fully discrete

dimensional lattice simulation of the Chronon field

. This simulation tests whether coherent spacetime structure, topological solitons, and causal horizons emerge dynamically from disordered initial conditions, as predicted by the CQG framework. The simulation framework allows quantitative evaluation of the field’s non-perturbative behavior and offers falsifiable predictions [

3,

45,

69].

6.1. Lattice Setup and Constraints

We discretize a spacetime region on a hypercubic lattice with spatial and temporal spacing a. Each lattice site, labeled , carries a unit-norm timelike vector constrained by:

Initial conditions are generated in a high-entropy phase, consisting of randomly oriented (but future-directed) unit timelike vectors, mimicking a pre-coherent, pre-causal phase of the early universe [

25].

6.2. Dynamics and Evolution Scheme

The Chronon field evolves under discrete gradient flow derived from the action

, including topological terms. The update rule is:

where

enforces the unit-norm and causal constraints at each step, and

is an auxiliary evolution parameter. This mimics dissipative minimization in configuration space and stabilizes solitonic sectors [

58,

64]. Boundary conditions are periodic in space and open in time.

Simulations were implemented in Python, using NumPy and Numba for high-performance array operations and just-in-time (JIT) compilation. A lattice of size with 300 time steps was used, corresponding to a discretized spacetime volume . Parallel execution was achieved through multithreading within Numba’s JIT-compiled kernels. Each run evolved the Chronon field over gradient descent steps, with unit-norm and causality constraints enforced at each update. The field configurations converged toward local minima of the discretized Chronon action, allowing detailed tracking of emergent foliation, causal structure, and topological solitons.

6.3. Observables and Diagnostics

The simulation produces a full spacetime field history . The following lattice observables were used to probe emergent structure:

-

Causal horizon radius : Extracted from the spatial two-point correlation function:

The extracted correlation length

is interpreted as the causal horizon radius [

26].

-

Topological soliton count: We compute a discretized winding number density based on the lattice analog of

:

This yields a count of localized topological solitons per unit volume [

49,

57].

Curvature diagnostics: Effective Ricci scalar

and Einstein tensor

are reconstructed using finite-difference derivatives of

[

21].

Entropy density: Estimated via the local spatial disorder and field defect density. Highly variable regions correlate with topological entropy, defined as a measure of winding density per unit area.

Causal cone reconstruction: By tracing the local orientation of across spacetime, we extract the emergent light cone structure and verify approximate Lorentzian propagation within coherent regions.

6.4. Emergence of Causal Order and Topological Structure

To investigate the nonperturbative dynamics of the Chronon field , we performed a dimensional lattice simulation with initial high-entropy configurations and monitored the evolution of entropy, metric structure, correlation length, and topological winding. The results demonstrate the self-organization of the system into a temporally coherent, causally structured phase, consistent with the central predictions of Chronon Quantum Gravity.

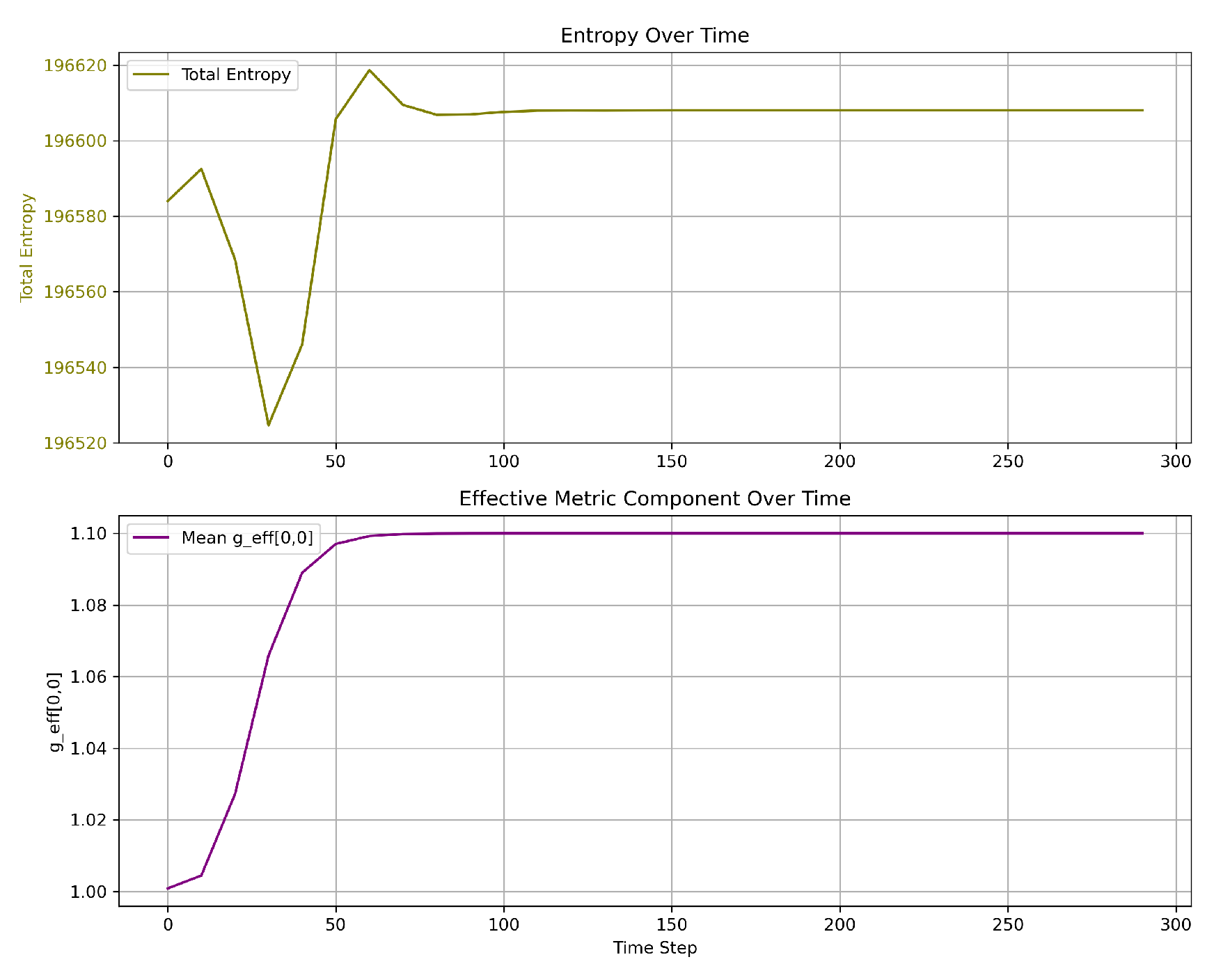

As shown in

Figure 1, the total entropy initially declines, reflecting the suppression of local fluctuations in the Chronon field as coherent domains emerge. The total entropy is modulated by the fixed lattice volume. Concurrently, the temporal component of the effective metric

increases and stabilizes, signaling the alignment of

and the emergence of a global time direction. This behavior is consistent with the formation of a preferred foliation of spacetime, generated dynamically via Chronon alignment.

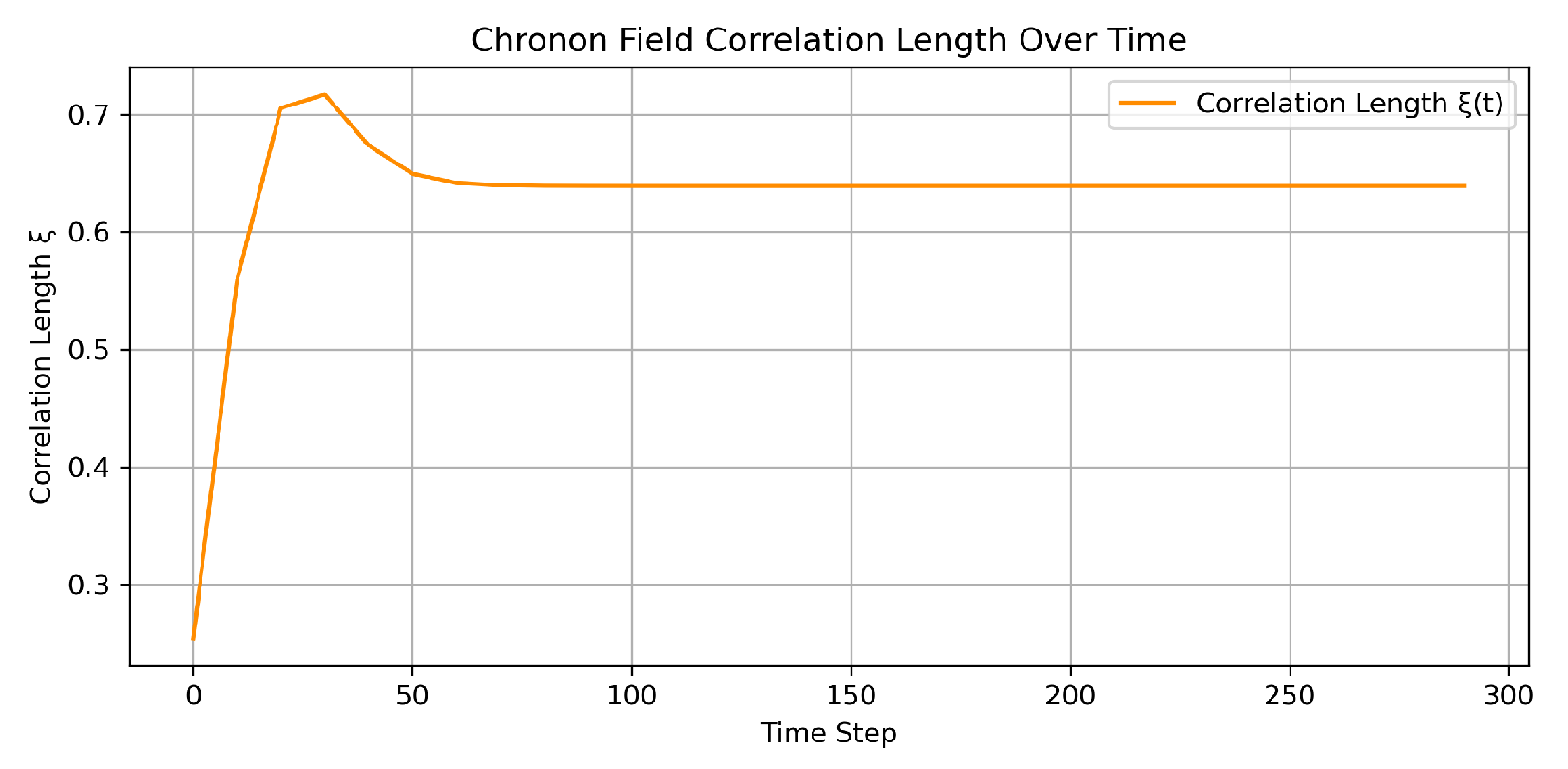

Figure 2 quantifies the growth of causal coherence by tracking the spatial correlation length

. This length characterizes the typical size of regions over which the temporal component

is aligned. The initial rapid rise of

corresponds to the coalescence of disordered patches into a globally foliated structure. The eventual plateau indicates that the causal correlation length saturates, consistent with the emergence of a stable temporal order and an effective causal horizon.

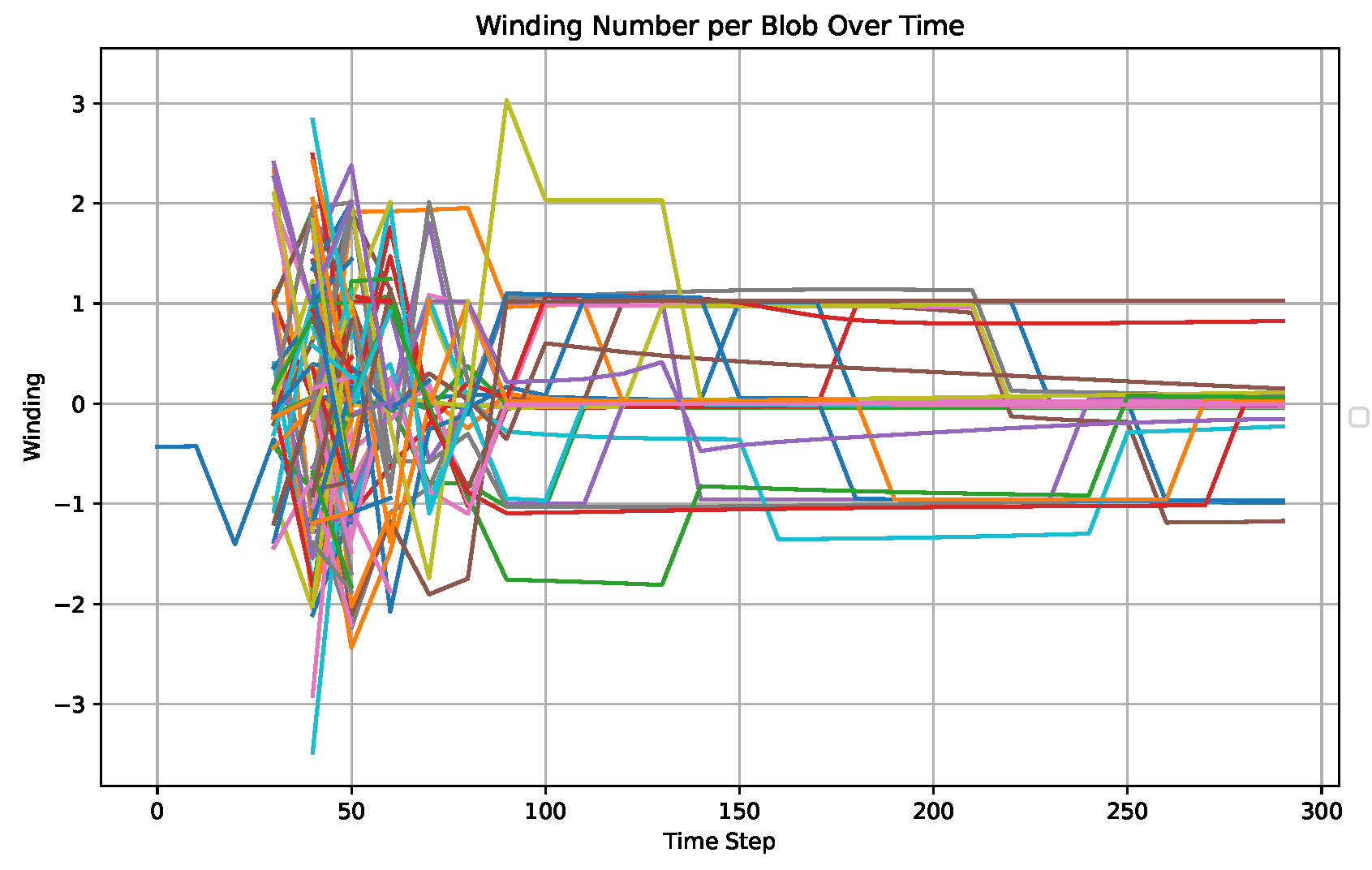

Topologically nontrivial configurations arise naturally in this setting, as seen in

Figure 3. The winding numbers associated with localized energy-density peaks (blobs) remain quantized and stable over time. These structures correspond to topological solitons classified by

and may serve as microscopic degrees of freedom contributing to gravitational entropy and matter content in the CQG framework.

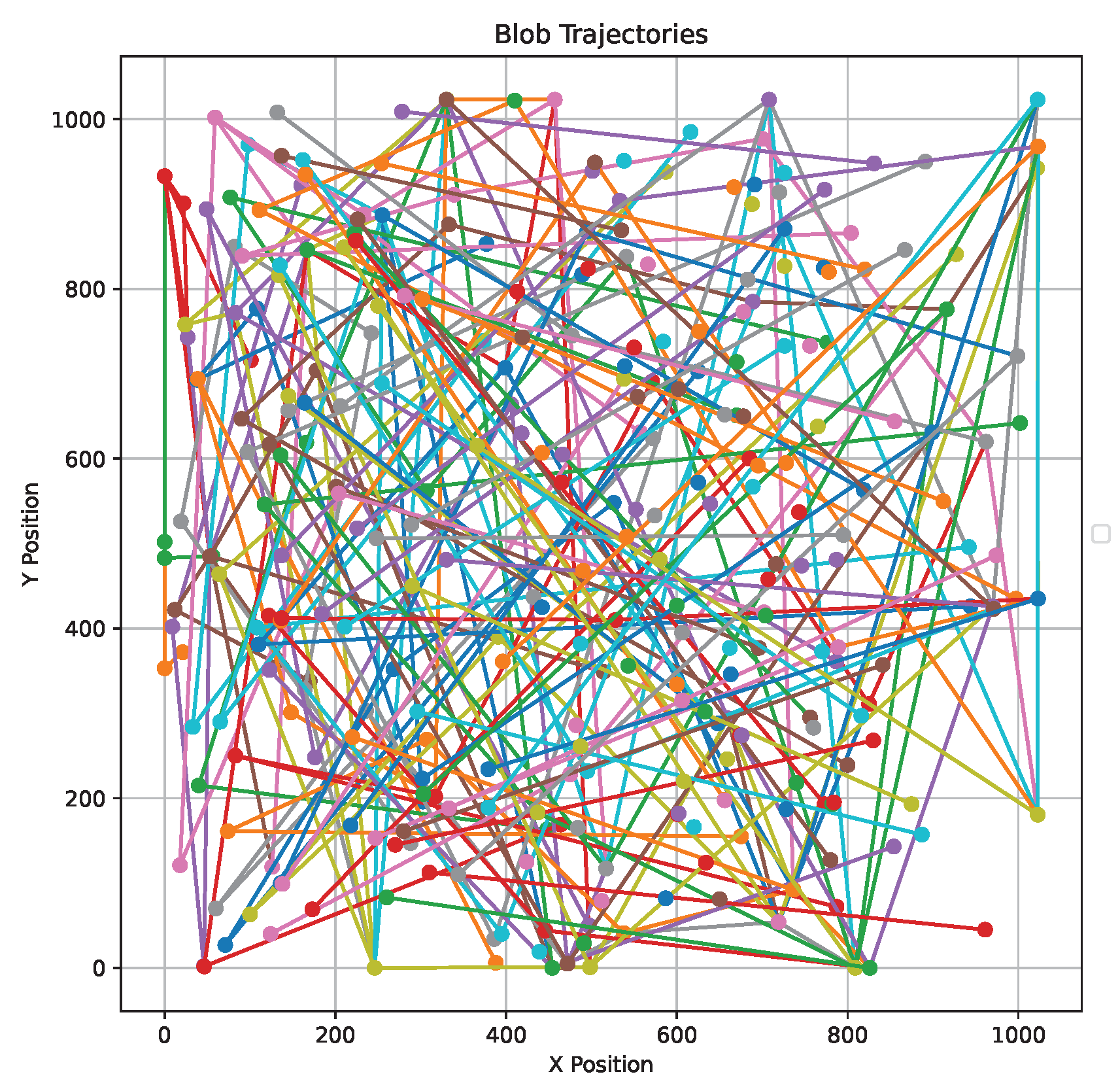

Finally, the spatial trajectories of topological blobs are shown in

Figure 4. Their continuous and coherent motion supports the interpretation of blobs as localized field excitations propagating through the dynamically generated spacetime. These paths are suggestive of particle-like behavior, modulated by the background geometry encoded in

.

6.5. Interpretation: Blob Interactions and Particle Analogues

The simulation also reveals rich dynamical behavior among topological solitons, suggestive of particle-like interactions. Blobs with winding number remain topologically protected throughout their lifetimes and exhibit quantized, stable trajectories, consistent with fermion-like excitations in the Chronon field. By contrast, structures—typically low-energy field concentrations without topological charge—correspond to bosonic excitations or collective metric modes.

Throughout the simulation, we observe several classes of soliton interactions:

Annihilation events, where pairs of oppositely wound blobs ( and ) merge and dissolve, indicating topological charge conservation and localized energy dissipation.

Blob decay, where single blobs lose coherence and vanish, consistent with energy transfer into the background field and metric fluctuations.

Fusion or merger, in which two blobs with the same sign winding number coalesce into a larger, composite excitation.

These behaviors mirror aspects of particle physics, such as conservation laws, decay widths, and interaction cross sections—but within a purely geometric and topological field setting. The analogy between winding number sectors and particle types opens the door to identifying matter content as emergent from coherent temporal topology. Future simulations with larger lattices and increased resolution will aim to quantify blob lifetimes, collision statistics, and their influence on causal structure evolution.

7. Comparison with Competing Quantum Gravity Approaches

Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG) offers a novel framework distinct from established approaches to quantum gravity.

Table 1 summarizes the comparative status of five major programs—string theory, loop quantum gravity (LQG), causal dynamical triangulations (CDT), asymptotic safety, and emergent gravity—across five core criteria: treatment of time, background independence, unification of matter and geometry, renormalizability, and empirical testability.

String Theory

A UV-complete theory built on one-dimensional strings propagating in fixed higher-dimensional spacetimes [

56]. While it unifies gravity and matter through vibrational modes, it retains background dependence and offers no resolution of the problem of time [

37]. Its predictions are largely inaccessible to current experiments. In contrast, CQG is formulated on a fully dynamical temporal field and derives both matter and geometry from topological features of temporal flow.

Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG)

Canonical quantization of GR via spin networks emphasizes background independence but suffers from the frozen time problem and lacks unification with matter [

5,

62]. CQG addresses these limitations by providing a physical clock through

and unifying spacetime and matter through Chronon topology.

Causal Dynamical Triangulations (CDT)

A discrete path integral formulation preserving causal structure via a foliation constraint [

3,

45]. CDT provides numerical evidence for emergent semiclassical spacetimes but includes only minimal matter and lacks a dynamical notion of time. CQG recovers foliation intrinsically via a smooth time field and accommodates solitonic matter structures.

Asymptotic Safety

Posits a nonperturbative UV completion through a fixed point of the gravitational renormalization group flow [

54,

59]. It retains a conventional treatment of time and does not unify matter dynamically. CQG, by contrast, achieves finiteness via topological regularity and ties dynamics to a quantized time field.

Emergent Gravity Paradigms

These include holographic and thermodynamic models where gravity arises from entropic or boundary dynamics [

39,

71]. They often lack locality, dynamical time, and background independence. CQG remains a manifestly local, causal, and quantizable field theory with an internal temporal ontology.

8. Discussion and Outlook

Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG) represents a significant departure from conventional approaches to quantum gravity. Rather than attempting to quantize the spacetime metric or treat time as a coordinate, CQG places a physical, causal, and dynamical time field—the Chronon field

—at the core of its formulation. In this framework, the topology and evolution of

generate not only spacetime geometry and causal structure but also matter content and quantum behavior. This ontological inversion, in which

time begets space, allows CQG to resolve foundational paradoxes that have hindered progress for decades [

37,

41,

65].

Several longstanding obstacles are addressed directly:

Problem of time: The Chronon field supplies a physical clock that defines evolution intrinsically, avoiding the frozen formalism of canonical quantum gravity [

19,

60].

Emergent geometry: Spacetime curvature and geodesic structure arise from the collective behavior of

, unifying matter and geometry as topological features of temporal flow [

26,

52].

Ultraviolet behavior: The solitonic, smooth, and topologically quantized nature of

configurations suggests that the theory is intrinsically finite, potentially eliminating the need for renormalization counterterms [

20,

74].

Black hole entropy: Entropy is reinterpreted as a measure of topological winding density of

across causal boundaries, providing a geometric and statistical foundation for the Bekenstein–Hawking formula [

7,

57].

While the formalism of CQG is internally consistent, certain elements—such as the time-dependent Wheeler–DeWitt equation derived via Chronon projection—remain heuristic at this stage. The full quantum constraint algebra has not yet been demonstrated to close under commutation, and a rigorous construction of the physical Hilbert space and inner product remains an open challenge. These foundational aspects are the subject of ongoing work aimed at embedding CQG in a complete nonperturbative quantum framework.

Beyond theoretical elegance, CQG offers concrete pathways to empirical validation. The lattice simulation program outlined herein enables the direct study of emergent causal structure, topological defects, and dynamical entropy generation from disordered initial conditions [

3,

45]. Such numerical investigations can serve as benchmarks for observable phenomena, including:

Deviations from classical general relativity in strong gravity regimes [

6,

55].

Gravitational wave signals from topological transitions in the Chronon field [

16,

23].

Non-standard decoherence and quantum interference patterns due to foliation fluctuations [

22].

Large-scale cosmological signatures linked to the correlation length dynamics of

[

25].

Future work will aim to deepen the mathematical structure of CQG by formalizing its topological classification scheme, quantization over moduli space of foliations, and coupling to standard model fields. Additionally, strong-field numerical relativity simulations incorporating CQG dynamics near black hole horizons and in early-universe scenarios are expected to yield novel insights.

In summary, CQG offers a coherent and predictive framework that unifies the disparate domains of quantum mechanics, gravitation, and cosmology under a single temporal ontology. By elevating time from a coordinate to a dynamic, quantizable field, it opens a new conceptual paradigm for the structure of physical law.

Author Contributions

Bin Li is the sole author.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CQG |

Chronon Quantum Gravity |

| CFT |

Chronon Field Theory |

Appendix A. Topological Classification and Quantization of Chronon Field Configurations

In this appendix, we formalize the topological structure underlying the Chronon field and demonstrate how its solitonic configurations are classified by quantized winding numbers. This provides the mathematical foundation for the entropy formula presented in Sec. V.

Appendix A.1. Chronon Field as a Map into S3

The Chronon field

is a smooth, future-directed timelike unit vector field on a Lorentzian spacetime

. It satisfies the normalization constraint:

with

ensuring a consistent global time orientation.

On a fixed spatial hypersurface

, this constraint implies that the spatial components of

lie on a 3-sphere:

since the full four-vector

lives on the hyperboloid defined by

in Minkowski space, which is diffeomorphic to

after suitable Wick rotation or embedding [

8,

49].

Thus, on compact spatial regions (e.g., near black hole horizons), the Chronon field defines a continuous map:

where

is assumed to be topologically compact (e.g., a 3-ball or 3-sphere near the horizon neighborhood).

Appendix A.2. Topological Charge and π 3 (S3)

The homotopy group

classifies the distinct homotopy classes of maps from a 3-sphere into itself. Each class corresponds to an integer winding number

, which counts how many times the domain wraps around the target sphere [

46,

68].

This winding number is defined as:

where

are local components of the Chronon field in an orthonormal frame, and the integrand is a Jacobian determinant measuring the volume form pullback from

.

This expression generalizes the Chern–Simons invariant and Hopf index, and is invariant under smooth deformations of

. It is quantized to integer values due to the compactness of the domain and target spaces [

35,

57].

Appendix A.3. Localization and Horizon Winding Density

For applications to black hole entropy, we consider a spatial slice intersecting the black hole horizon

. Assuming topological triviality outside the black hole and a localized nontrivial configuration near the horizon, we define the winding

density:

where

is the unit normal vector to the spatial hypersurface and

is a normalization factor ensuring quantization:

The total entropy is then proportional to the integrated winding density over the horizon 2-surface

:

Appendix A.4. Quantization and Stability

Topologically nontrivial configurations of

with nonzero

are stable under local perturbations, since changing the winding number requires a discontinuous deformation or topological transition (e.g., during black hole mergers). These sectors represent distinct quantum microstates of the gravitational field configuration, consistent with a statistical mechanical interpretation of black hole entropy [

7,

61].

The quantization of

implies that entropy changes in discrete units associated with topological transitions. Such transitions may be accompanied by observable effects, such as bursts or plateaus in gravitational wave emission during horizon topology change events [

16,

23].

Appendix A.5. Outlook

This topological perspective unifies several key ideas: the emergence of spacetime from temporal coherence, the quantization of entropy from field topology, and the stability of gravitational microstates as global features of

. Further work will formalize this structure using the language of fiber bundles, characteristic classes, and index theorems on foliated manifolds [

48].

Appendix B. Canonical Structure and Constraints of the Chronon Field

In this appendix, we derive the canonical structure of Chronon Quantum Gravity by performing a decomposition of the Chronon field and identifying the associated constraint algebra. This formalism lays the groundwork for the Hamiltonian analysis and quantization used in Sec. IV.

Appendix B.1. Chronon Field and 3+1 Decomposition

We begin by foliating the spacetime manifold

into a family of spacelike hypersurfaces

orthogonal to the Chronon field

. The foliation is determined dynamically by the integral curves of

, which serve as physical clocks [

9,

60].

Let

denote the unit future-directed normal vector to

, aligned with

:

We decompose the Chronon field into its temporal and spatial parts relative to the foliation:

where

N is a lapse-like scalar field, and

is a spatial shift vector satisfying

. However, in CQG,

is not a gauge artifact but a dynamical field, so the lapse and shift are not gauge parameters but derived components of

.

Appendix B.2. Canonical Variables and Conjugate Momenta

We define canonical variables on each hypersurface

:

where the dot denotes a derivative with respect to Chronon time

along

. The canonical momentum

is derived from the Lagrangian density:

with

.

The symplectic structure is then:

and all other equal-time Poisson brackets vanish [

33].

Appendix B.3. Primary and Secondary Constraints

The Chronon field is subject to the primary constraint:

enforcing the unit timelike norm. To ensure consistency under time evolution, we compute:

which generates a secondary constraint. The exact form depends on the specific Hamiltonian density

, including contributions from topological and kinetic sectors.

These constraints generate a surface

in phase space. Physical states are those lying on

and preserved under the Hamiltonian flow [

18,

33].

Appendix B.4. Hamiltonian and Constraint Algebra

The total Hamiltonian takes the form:

where

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing the normalization constraint, and

includes topological charges such as:

The full constraint algebra can be organized analogously to Dirac’s treatment of constrained systems. Specifically, the constraint

is second class (due to the nontrivial norm condition), while diffeomorphism constraints can be recovered from spatial reparameterizations on

[

19,

28].

Appendix B.5. Quantization Considerations

Upon quantization, the classical constraints are imposed as operator conditions on wavefunctionals:

Here,

is a functional defined on the configuration space of normalized Chronon field configurations on

. The Hilbert space is thus the space of square-integrable functionals over the constrained field space:

This canonical structure provides a foundation for understanding Chronon dynamics at both classical and quantum levels. Future work will extend this structure to include coupling with matter fields, quantization over topologically nontrivial bundles, and the development of a BRST formalism for constraint quantization [

27,

32].

Appendix C. Coupling of Standard Matter Fields to the Chronon Field

To develop a complete framework for Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG), it is essential to define how standard matter fields couple to the Chronon field

. Since CQG treats

as a dynamical, physical time vector field inducing a preferred foliation of spacetime, all matter couplings must be consistent with this foliation and the constraints of background independence [

9,

63].

Appendix C.1. Minimal Coupling via Effective Metric

A natural way to couple matter fields to the Chronon field is through the effective metric:

where

is a small coupling constant characterizing the backreaction strength of the temporal field. This metric serves as the emergent spacetime geometry in which matter propagates.

For a scalar field

, the action is:

consistent with standard covariant formulations [

13,

53].

This formulation ensures that the scalar field respects the causal and geometric structure induced by . In the classical limit where is coherent, this reproduces standard dynamics on a curved background. In regions of strong Chronon fluctuation, matter evolution becomes nontrivially influenced by the topological and solitonic content of the temporal field.

Appendix C.2. Foliation-Adaptive Field Dynamics

In the canonical formalism, matter fields are evolved on each leaf

of the Chronon foliation. Define

as Chronon proper time and decompose spacetime derivatives accordingly:

where

denotes the covariant derivative on the spatial slice

. The kinetic term splits as:

where

is the induced spatial metric on

[

28].

Thus, the Hamiltonian for matter fields takes the form:

with

as the canonical momentum conjugate to

.

Appendix C.3. Spinor Fields and Chronon-Aligned Dirac Operators

For spinor fields

, one must define a Chronon-adapted vierbein (tetrad) basis

satisfying:

This choice ensures that the spinor Dirac matrices

are defined relative to a locally inertial frame co-moving with the Chronon field. The Dirac action becomes:

where

is the spinor covariant derivative compatible with

. This construction allows spinors to propagate causally in the Chronon-induced spacetime [

53,

72].

Appendix C.4. Gauge Fields and Topological Couplings

Gauge fields

may also couple minimally to

:

Alternatively, one can explore nonminimal and topological couplings where gauge fields interact directly with

:

where

is a coupling constant. Such terms may induce parity violation, chiral anomalies, or contribute to dark sector phenomenology [

2,

35].

Appendix C.5. Summary

Matter fields couple to the Chronon field through:

The effective metric , preserving background independence.

Chronon-induced foliations , providing a preferred temporal evolution frame.

Possible direct topological couplings, yielding new interaction terms and phenomenology.

These couplings preserve the local Lorentz structure but embed matter dynamics within the causal-temporal framework generated by . This allows CQG to support a unified treatment of quantum matter and gravity without requiring an external background or arbitrary clock choice.

Appendix D. Renormalizability and Anomaly Cancellation in Chronon–Matter Couplings

A complete theory of quantum gravity must account for the ultraviolet (UV) behavior of both geometric and matter sectors. In Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG), the Chronon field introduces novel structures and interactions, raising nontrivial questions about renormalizability and anomaly freedom in the presence of standard matter fields.

Appendix D.1. Chronon Sector and UV Behavior

The Chronon field is governed by a constrained vector field action with additional topological terms:

Unlike general relativity, this action is constructed from quantities with mass dimension 4, suggesting that CQG may be renormalizable or asymptotically safe when formulated over a topologically regularized field space [

59,

73]. The presence of topological sectors also implies that UV divergences may be tamed by solitonic quantization or modular compactification of the field configuration space [

8,

74].

Appendix D.2. Matter Coupling and Power Counting

Standard matter fields (scalars, spinors, gauge bosons) are coupled to CQG via the effective metric:

with

controlling the strength of temporal backreaction. Because this coupling is analytic in

, it does not introduce higher-derivative operators, preserving the renormalizability of matter sectors in flat spacetime [

13].

In the absence of dynamical gravity (i.e., assuming

as a fixed background), matter field theories retain their standard renormalization structure. When

is fully dynamical, loop corrections from matter fields may generate effective operators involving curvature of

and derivatives of

. The renormalizability of the combined system then depends on whether these induced operators can be absorbed by field redefinitions or renormalization of Chronon couplings [

53].

Appendix D.3. Anomaly Cancellation

Gauge and gravitational anomalies pose critical constraints on any coupling between matter and background fields. In CQG, potential anomalies include:

Gauge anomalies: arising from fermion loops in the presence of gauge fields and Chronon-induced axial couplings.

Diffeomorphism anomalies: arising from the nontrivial foliation structure and coupling to .

Lorentz anomalies: due to the selection of a preferred time direction by the Chronon field.

The anomaly structure can be controlled by demanding the total effective action remains invariant under local gauge transformations and foliation-preserving diffeomorphisms (FDiffs), which are the symmetry group of the Chronon-adapted slices [

27,

34].

In particular, topological terms of the form:

can potentially generate gauge anomalies unless matched by contributions from matter content (e.g., chiral fermions) that cancel the total anomaly via the standard mechanism of anomaly inflow or the Green–Schwarz-type anomaly counterterms [

2,

29].

Appendix D.4. Topological Regularization and UV Finiteness

An important feature of CQG is that UV divergences in the Chronon sector may be regulated topologically. Since the configuration space of

is constrained by

and compactified by topological sector separation (e.g., distinct

classes), the path integral:

is effectively computed over a stratified moduli space of causal and topologically stable configurations [

8,

50]. This structure may suppress high-frequency fluctuations and serve as a natural UV cutoff.

Appendix D.5. Outlook

While CQG in its current formulation shows signs of being power-counting renormalizable and topologically regularized, a complete proof of renormalizability—particularly in the presence of dynamical matter—is still pending. Key open directions include:

A full heat-kernel expansion for operators defined on with dependence.

The computation of 1-loop effective actions to identify nonrenormalizable divergences.

Anomaly matching conditions for chiral matter in foliated spacetime.

Development of a BRST or BV formalism adapted to Chronon-constrained systems.

In conclusion, the CQG framework is anomaly-safe under specific symmetry assumptions and matter content, and may be rendered UV complete through its topologically constrained structure. This places it among the few background-independent approaches to quantum gravity with a plausible route to renormalizability and empirical viability.

Appendix E. Symmetry-Breaking Case Study: Foliation Violation

In Chronon Quantum Gravity (CQG), the spacetime foliation defined by the Chronon field is central to both the classical and quantum formulations of the theory. It provides an intrinsic time direction, defines spatial hypersurfaces , and supports causal propagation. In this appendix, we examine the consequences of breaking this foliation structure, either explicitly or spontaneously, and analyze its impact on the dynamics, symmetries, and observational viability of the theory.

Appendix E.1. Foliation Symmetry and Chronon Invariance

In the full CQG theory, the action is invariant under:

Foliation-preserving diffeomorphisms (FDiffs): transformations of the form and that preserve the slicing .

Chronon reparameterizations: field redefinitions of that maintain unit-norm and global time orientation.

These symmetries ensure that physical observables are independent of coordinate choices within each spatial slice and respect the intrinsic notion of time defined by the Chronon field [

14,

34].

Appendix E.2. Explicit Foliation Violation: Perturbative Instability

Consider a deformation of the Chronon field by a non-causal fluctuation:

violating the orthogonality and unit-norm constraint. Such a perturbation breaks the foliation-preserving symmetry and allows components of the metric

to evolve outside the causal cone defined by

.

The resulting dynamics generally fail to conserve the Hamiltonian constraint derived under the foliation, leading to a non-closure of the constraint algebra:

This signals a breakdown of unitarity and predictability unless the theory is extended to include compensating degrees of freedom or additional gauge conditions that restore constraint consistency [

18,

33].

Appendix E.3. Spontaneous Foliation Breaking: Topological Phase Transitions

Alternatively, foliation violation may occur spontaneously via topological transitions in , such as:

Formation of domain walls or defects where becomes ill-defined.

Emergence of closed timelike curves in regions where loses global integrability.

Phase transitions where the field undergoes a jump between topologically distinct sectors (e.g., change in winding number).

In such cases, the foliation structure is well-defined almost everywhere but breaks down locally. One can define a defect current or topological obstruction:

which acts as a source term in the Chronon field equation and modifies conservation laws for matter and gravitational flux across defect surfaces [

49,

57].

Appendix E.4. Anomalous Transport and Observables

Violations of foliation symmetry induce anomalous transport phenomena in the matter sector. For instance:

Modified dispersion relations for scalar or spinor fields near foliation-breaking regions.

Local Lorentz-violating interactions, detectable in strong-gravity regimes.

Non-conservation of energy-momentum in effective field theory on a misaligned Chronon background:

where

encodes anomaly-induced current sourced by foliation deviation.

These effects may be constrained observationally via:

Precision gravitational wave measurements detecting local phase shifts [

16].

High-energy astrophysical signals sensitive to causal structure near compact objects [

44].

Cosmological imprints from early-universe foliation instabilities [

26].

Appendix E.5. Restoration via Auxiliary Fields

To maintain consistency, one may introduce an auxiliary Lagrange multiplier field

enforcing foliation stability dynamically:

Alternatively, foliation-breaking terms can be systematically added and controlled using spurion fields that transform under FDiffs but acquire fixed background values [

30].

Appendix E.6. Summary

Foliation symmetry in CQG is critical to its background-independent dynamics. Both explicit and spontaneous violations lead to rich, but potentially problematic, physics: anomalies, breakdown of unitarity, and observational deviations from classical general relativity. While foliation breaking may serve as a probe of quantum gravitational structure, maintaining a consistent constraint algebra likely requires either dynamically enforced foliation preservation or an extended field content that absorbs anomalies. This makes the symmetry-breaking sector a promising frontier for phenomenological tests and theoretical refinements.

References

- R. Arnowitt, S. Deser, and C. W. Misner, “Dynamical structure and definition of energy in general relativity,” Phys. Rev. 116, 1322 (1959). [CrossRef]

- L. Alvarez-Gaumé and E. Witten, “Gravitational anomalies,” Nucl. Phys. B 234, 269 (1984).

- J. Ambjørn, J. Jurkiewicz, and R. Loll, “Dynamically triangulating Lorentzian quantum gravity,” Nucl. Phys. B 610, 347 (2001). [CrossRef]

- E. Anderson, “The problem of time in quantum gravity,” in Class. Quantum Grav. 29, 235015 (2012), arXiv:1206.2403 [gr-qc]. [CrossRef]

- A. Ashtekar and J. Lewandowski, “Background independent quantum gravity: A status report,” Class. Quant. Grav. 21, R53 (2004). [CrossRef]

- A. Ashtekar and B. Gupt, “Quantum gravity in the sky: Interplay between fundamental theory and observations,” Class. Quant. Grav. 38, 043001 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Ashtekar, J. Baez, and K. Krasnov, “Quantum geometry of isolated horizons and black hole entropy,” Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 4, 1–94 (2000).

- J. C. Baez, “Link invariants of finite type and perturbation theory,” Lett. Math. Phys. 26, 43–51 (1994).

- J. Barbour, “The timelessness of quantum gravity: I. The evidence from the classical theory,” Class. Quant. Grav. 11, 2853 (1994).

- C. Barceló, S. Liberati, and M. Visser, “Analogue gravity,” Living Rev. Relativ. 8, 12 (2005).

- J. D. Bekenstein, “Black holes and entropy,” Phys. Rev. D 7, 2333 (1973).

- E. Bianchi and C. Rovelli, “Why all these prejudices against a constant?” Nature 466, 321 (2010).

- N. D. Birrell and P. C. W. Davies, Quantum Fields in Curved Space, Cambridge University Press (1982).

- D. Blas, O. Pujolàs, and S. Sibiryakov, “Models of non-relativistic quantum gravity: The good, the bad and the healthy,” JHEP 2011, 18 (2011).

- M. Bojowald, “Absence of singularity in loop quantum cosmology,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5227 (2001). [CrossRef]

- M. Cabero et al., “Black hole spectroscopy: Testing the no-hair theorem with GW150914,” Phys. Rev. D 100, 104036 (2019).

- B. S. DeWitt, “Quantum theory of gravity. I. The canonical theory,” Phys. Rev. 160, 1113 (1967).

- P. A. M. Dirac, Lectures on Quantum Mechanics, Yeshiva University Press (1964).

- B. Dittrich, “Partial and complete observables for canonical general relativity,” Class. Quant. Grav. 23, 6155 (2006). [CrossRef]

- L. Freidel et al., “Gravitational Frames and the Planck Scale,” arXiv:2301.05917 [hep-th].

- R. Gambini and J. Pullin, “Discrete quantum gravity: applications to cosmology,” Class. Quant. Grav. 20, 3341 (2003).

- R. Gambini and J. Pullin, “The Montevideo interpretation of quantum mechanics: frequently asked questions,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 174, 012003 (2009).

- A. Ghosh, K. Lochan, and D. Pranzetti, “Quantum hair and entropy of dynamical black holes,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 221302 (2022).

- G. W. Gibbons and S. W. Hawking, “Action Integrals and Partition Functions in Quantum Gravity,” Phys. Rev. D 15, 2752 (1977).

- S. Gielen and D. Oriti, “Quantum cosmology from group field theory condensates: a review,” New J. Phys. 16, 123004 (2014).

- S. Gielen and L. Sindoni, “Quantum cosmology from quantum gravity condensates: cosmological variables and lattice-refined dynamics,” Phys. Rev. D 102, 066019 (2020).

- J. Gomis, J. Paris, and S. Samuel, “Antibracket, antifields and gauge-theory quantization,” Phys. Rep. 259, 1 (1995). [CrossRef]

- E. Gourgoulhon, “3+1 formalism and bases of numerical relativity,” arXiv:gr-qc/0703035.

- M. B. Green and J. H. Schwarz, “Anomaly cancellations in supersymmetric D=10 gauge theory and superstring theory,” Phys. Lett. B 149, 117 (1984). [CrossRef]

- G. Gubitosi, F. Piazza, and F. Vernizzi, “The effective field theory of dark energy,” JCAP 1302, 032 (2013), arXiv:1210.0201 [hep-th].

- S. W. Hawking, “Particle creation by black holes,” Commun. Math. Phys. 43, 199–220 (1975).

- M. Henneaux, “Hamiltonian Form of the Path Integral for Theories with a Gauge Freedom,” Phys. Rep. 126, 1 (1985).

- M. Henneaux and C. Teitelboim, Quantization of Gauge Systems, Princeton University Press (1992).

- P. Horava, “Quantum gravity at a Lifshitz point,” Phys. Rev. D 79, 084008 (2009).

- G. T. Horowitz, “Exactly Soluble Diffeomorphism Invariant Theories,” Commun. Math. Phys. 125, 417–437 (1989).

- B. L. Hu and E. Verdaguer, “Stochastic gravity: Theory and applications,” Living Rev. Relativ. 7, 3 (2004).

- C. J. Isham, “Canonical quantum gravity and the problem of time,” in Integrable Systems, Quantum Groups, and Quantum Field Theories, NATO ASI Series C 409, 157–287 (1993).

- T. Jacobson, “Black hole entropy and induced gravity,” Phys. Rev. D 50, R6031 (1994).

- T. Jacobson, “Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1260 (1995).

- K. V. Kuchař, “Time and interpretations of quantum gravity,” in Proceedings of the 4th Canadian Conference on General Relativity and Relativistic Astrophysics, edited by G. Kunstatter, D. Vincent, and J. Williams (World Scientific, Singapore, 1992), pp. 211–314.

- K. V. Kuchař, “Time and interpretations of quantum gravity,” in Proceedings of the 4th Canadian Conference on General Relativity and Relativistic Astrophysics, World Scientific (1992).

- B. Li, “Chronon Phase Transition Cosmology: A Unified Framework for Emergent Spacetime, Dark Matter, and Dark Energy,” Zenodo, 2025. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15358056. [CrossRef]

- B. Li, “Chronon Field Theory: Unification of Gravity and Gauge Interactions via Temporal Flow Dynamics,” (2025), Preprint, Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo.15340460.

- S. Liberati, “Tests of Lorentz invariance: a 2013 update,” Class. Quant. Grav. 30, 133001 (2013).

- R. Loll, “The emergence of spacetime or quantum gravity on your desktop,” Class. Quant. Grav. 25, 114006 (2008).

- N. Manton and P. Sutcliffe, Topological Solitons, Cambridge University Press (2004).

- F. Markopoulou, “Quantum causal histories,” Class. Quant. Grav. 17, 2059 (2000). [CrossRef]

- J. Milnor and J. D. Stasheff, Characteristic Classes, Princeton University Press (1974).

- M. Nakahara, Geometry, Topology and Physics, 2nd ed., CRC Press (2003).

- H. Nicolai, K. Peeters, and M. Zamaklar, “Loop quantum gravity: An outside view,” Class. Quant. Grav. 22, R193 (2005). [CrossRef]

- D. Oriti, “Group field theory and loop quantum gravity,” in Loop Quantum Gravity: The First 30 Years, eds. A. Ashtekar and J. Pullin, World Scientific (2014).

- D. Oriti, “Levels of spacetime emergence in quantum gravity,” in Beyond Spacetime, eds. N. Huggett et al., Cambridge University Press (2018).

- L. Parker and D. Toms, Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime, Cambridge University Press (2009).

- R. Percacci, An Introduction to Covariant Quantum Gravity and Asymptotic Safety, World Scientific (2017).

- A. Perez, “Black holes in loop quantum gravity,” Rept. Prog. Phys. 80, 126901 (2017).

- J. Polchinski, String Theory, Vols. I & II, Cambridge University Press (1998).

- A. F. Ranada, “A topological theory of the electromagnetic field,” Lett. Math. Phys. 18, 97–106 (1989).

- T. Regge, “General relativity without coordinates,” Nuovo Cimento 19, 558 (1961).

- M. Reuter and F. Saueressig, “Quantum Gravity and the Functional Renormalization Group,” Cambridge University Press (2019).

- C. Rovelli, “Time in quantum gravity: An hypothesis,” Phys. Rev. D 43, 442 (1991).

- C. Rovelli, “Black hole entropy from loop quantum gravity,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3288 (1996). [CrossRef]

- C. Rovelli, Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press (2004).

- C. Rovelli, “Relational quantum mechanics,” Int. J. Theor. Phys. 35, 1637–1678 (1996).

- L. Smolin, “Matrix models as non-local hidden variables theories,” hep-th/0201031.

- L. Smolin, “How far are we from the quantum theory of gravity?,” hep-th/0303185.

- S. N. Solodukhin, “Entanglement entropy of black holes,” Living Rev. Relativ. 14, 8 (2011).

- R. D. Sorkin, “Forks in the road, on the way to quantum gravity,” Int. J. Theor. Phys. 36, 2759–2781 (1997). [CrossRef]

- N. Steenrod, The Topology of Fibre Bundles, Princeton University Press (1951).

- S. Surya, “The causal set approach to quantum gravity,” Living Rev. Relativ. 22, 5 (2019).

- L. Susskind, “The World as a hologram,” J. Math. Phys. 36, 6377 (1995). [CrossRef]

- E. Verlinde, “On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton,” JHEP 2011, 29 (2011). [CrossRef]

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity, University of Chicago Press (1984).

- S. Weinberg, “Ultraviolet divergences in quantum theories of gravitation,” in General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey, ed. Hawking and Israel, Cambridge Univ. Press (1979).

- E. Witten, “Topological quantum field theory,” Commun. Math. Phys. 117, 353–386 (1988).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).