Introduction:

Buildings are responsible for approximately 40% of total global energy consumption with a significant portion dedicated to Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems that regulate indoor environmental quality (IEQ) [

1,

2]. This demand is propelled by rapid urbanization and climate change, accentuating the urgent need to align architectural practices with international sustainability frameworks linked to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 3 (Health and Well-being), SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) [

3,

4]. The study revealed that people spend more than 80% of their time in an indoor activity [

5]

. Indoor environments that embrace thermal comfort, air quality, and daylighting exert a significant impact on health, productivity, and overall well-being [

6]. In this context, windows play as a key architectural element in addressing the dual challenge of energy efficiency and IEQ, which is interlinked with the building’s physical, operational, environmental, and socio-behavioral aspects. Previous studies have shown that window-related factors such as geometric design, glazing technologies, shading systems, and a range of control strategies - ranging from manual adjustments to artificial intelligence (AI) driven systems - directly influence fundamental building physics, including thermal insulation, solar heat gain, airflow dynamics, and ventilation strategies like natural and mixed-mode airflow regimes [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Strategic window design significantly enhances natural ventilation performance [

13], while optimized placement can substantially improve thermal comfort [

14]. Even simple modifications to window parameters, such as size and orientation, have been shown to reduce air temperature by 2.5% and increase air velocity by a factor of six [

15]

. In the technological era, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Energy Plus simulations can help substantiate the performance and limitations of these strategies, reinforcing the critical role of windows in enabling sustainable, occupant-focused building design [

16].

Recent studies underline the importance of adaptive design strategies that enhance IEQ through robust occupant-window interactions, merging socio-behavioral insights with environmental responsiveness. For instance, entire openings coupled with wind from the south and southeast directions can improve the indoor environment for occupants engaged in various activities [

12]. Passive techniques, particularly when combined with ventilation and roofing materials in sustainable systems, have been shown to increase thermal comfort by up to 16% in hot and humid climates, thereby reducing reliance on energy-intensive HVAC systems [

17]. These findings align with the historical significance of passive design approaches, which have long been used to maintain thermal comfort in a cost-effective manner [

18]. The strategic placement, orientation, and intelligent control systems of windows - such as AI-driven adjustments and occupants’ behavior, can enhance natural ventilation efficiency and thermal comfort by aligning airflow patterns with both climatic conditions and user preferences [

5,

19,

20,

21]. Integrating adaptive thermal comfort models with user-operated mechanisms, such as dynamic shading, has been shown to reduce HVAC energy consumption up to 30% in mixed-mode buildings while improving perceived comfort [

22,

23]. Moreover, proper ventilation reduces indoor pollutant concentrations, thereby improving health outcomes while supporting energy savings [

24]. This amalgamation of passive design strategies and occupant engagement outlines windows as dynamic interfaces that translate human behavior into sustainable performance, effectively supporting the SDGs 3, 7, and 11 through context-aware and occupant-centric architectural design.

Window operational behavior is influenced by five major factors: environmental, contextual, psychological, physiological, and social milieus [

25]. The linkage of window behavior and energy performance highlighted that understanding occupants’ behavior assists in developing design strategies to improve the indoor environment. While existing studies emphasize context-specific benefits, there is limited field validation across diverse climatic zones, particularly in tropical and arid regions, where solar heat gain and ventilation dynamics vary significantly. In addition, the impact of geometric design parameters - such as window-to-wall ratios, orientation, and shading integration - is often investigated in isolation rather than holistically, overlooking their combined effect on thermal comfort, particularly room-specific functions. Spaces having specific functions, such as kitchens, living rooms, and bedrooms, have distinct thermal, ventilation, and daylighting needs; yet most studies do not tailor window design or operation strategies according to room usage.

Despite advancements in adaptive window design and occupant-centric strategies, critical gaps remain in understanding the complex interplay between multi-climate adaptability, the interrelations between window interferences and occupants’ behavior, and occupants’ roles in window design strategies linked to building energy performance. This review aims to analyze the historical significance of thermal comfort, the correlations between thermal comfort and windows’ behavior, the occupants’ role in windows’ behavior along the design strategies, its impact on building energy performance, and the sustainability practice underlying windows’ behavior.

Methodology:

This study adopted a systematic review of the literature protocol to investigate the effects of window behavior on indoor thermal comfort, with a focus on behavioral patterns and methods. The review aimed to identify, scrutinize, and synthesize relevant peer-reviewed studies, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of the current research landscape. The Scopus database was selected for its extensive indexing of peer-reviewed literature across engineering, architecture, and environmental sciences. Its multidisciplinary scope makes it an ideal resource for retrieving studies pertinent to thermal comfort, ventilation strategies, window behaviour, design strategies, and emerging trends.

The literature search was conducted in the Scopus database by targeting article titles, abstracts, and keywords. The search strategy was developed using four distinct keyword clusters. These clusters, shown in

Table 1, were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR) to capture a wide range of relevant studies, restricting results to English-language articles. To ensure the quality and relevance of the reviewed literature, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Inclusion criteria encompassed peer-reviewed journal articles, review papers, and book chapters published between 2000 and 2025 that focused on thermal comfort and window behavior in buildings while employing building simulation or CFD methodologies. Exclusion criteria eliminated conference papers, editorials, non-peer-reviewed sources, articles not in English, and studies unrelated to window behavior, ventilation, or thermal comfort.

The initial Scopus search retrieved 225 articles studies, which formed the basis for the bibliometric and scientometric analyses. A rigorous screening process based on relevance, methodological clarity, and data completeness refined dataset of 112 articles for detailed content analysis. This final set comprised 28 studies from the original bibliometric dataset and 84 additional studies identified through targeted searches outside the Scopus query. This approach ensured comprehensive coverage of both indexed and non-indexed but relevant literature.

Bibliometric and Scientometric Analysis:

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the research landscape on the importance of window behavior and its impact on indoor thermal comfort, bibliometric and scientometric analyses were conducted using VOSviewer. These methodologies facilitated the identification of key research themes, influential authors, global research collaboration patterns, and the most cited works in this domain, thereby offering valuable insights into the evolution of research trends and interdisciplinary linkages.

1.1. Thematic Analysis Using Keyword Co-Occurrence:

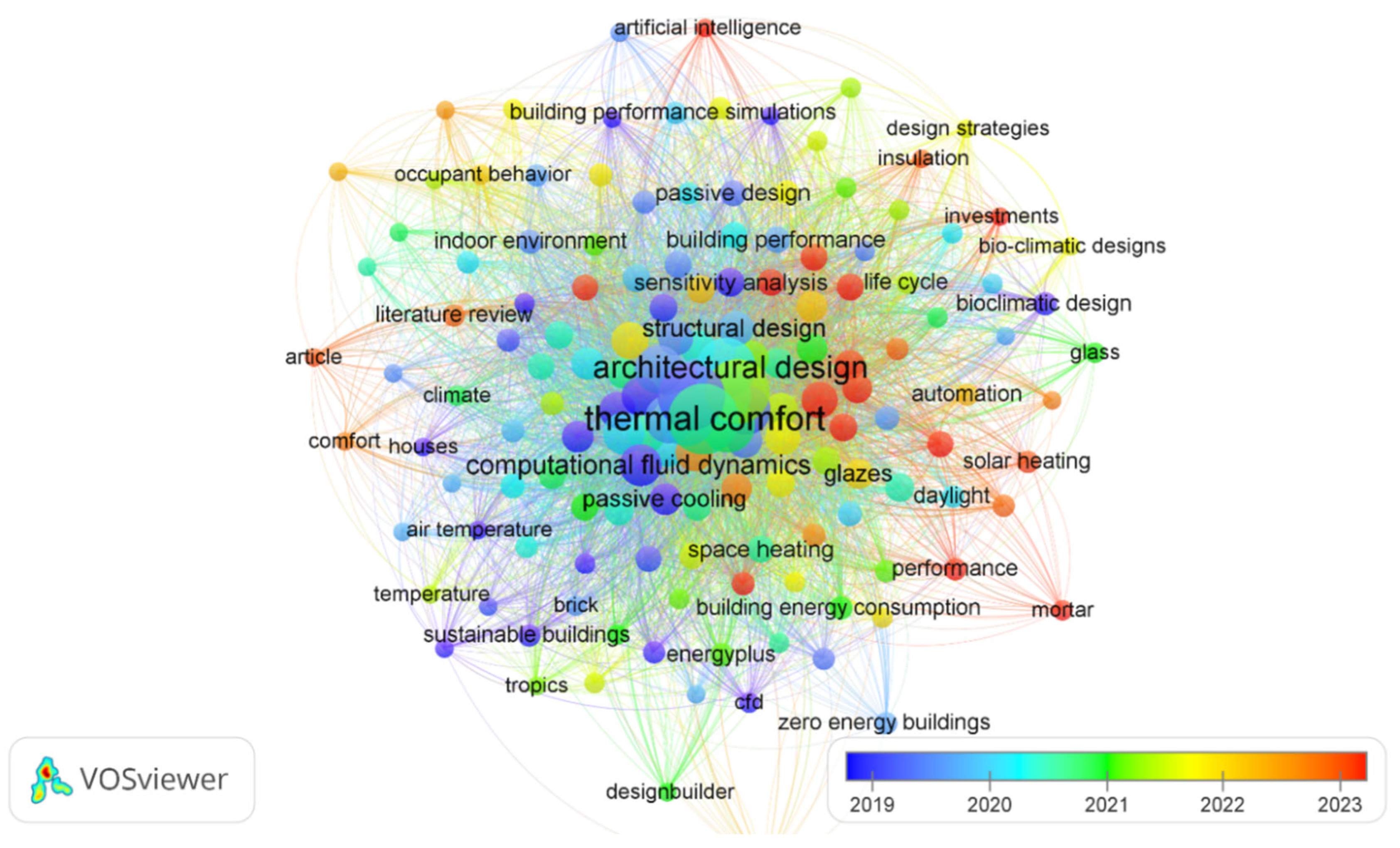

A keyword co-occurrence analysis was performed to identify key research themes within the study of window behavior and its impact on indoor thermal comfort. The analysis considered all keywords from 225 selected papers, establishing a minimum occurrence threshold of five. Out of 1,931 keywords, 152 met the threshold, and the results, illustrated in the keyword co-occurrence map (

Figure 1), revealed four principal research clusters: Thermal Comfort, Window Strategies and Window Operations, Computational Modeling, and Emerging Technologies as Design Strategies and Sustainability.

The Thermal Comfort cluster highlights the significance of cooling strategies in enhancing indoor environmental conditions. Dominant keywords such as “thermal comfort” (92 occurrences, total link strength 864), “air quality” (24 occurrences, total link strength 258), “daylighting” (13 occurrences, total link strength 92), “indoor thermal environments” (6 occurrences, total link strength 63), and “occupant behavior” (5 occurrences, total link strength 55) indicate a strong research focus on optimizing temperature, humidity, and air movement to improve occupant well-being. This cluster underscores the development of both passive and active cooling strategies aimed at improving indoor comfort.

The Ventilation Strategies and Window Operations cluster emphasizes the critical role of behaviour in different climates. Keywords such as “natural ventilation” (54 occurrences, total link strength 452), “passive cooling” (16 occurrences, total link strength 147), “smart windows” (10 occurrences, total link strength 85), and “window openings” (5 occurrences, total link strength 60) reflect an increasing research emphasis on airflow dynamics, temperature regulation, and energy efficiency through optimized window operations. Studies in this cluster investigate the impact of various window configurations, opening schedules, and occupant interaction patterns on indoor climate control.

The Computational Modeling cluster signifies the growing reliance on numerical simulations to assess window behavior and its effects on thermal comfort linked to building energy performance. Keywords such as “CFD” (29 occurrences, total link strength 287) and “EnergyPlus” (8 occurrences, total link strength 67) indicate a strong dependence on simulation tools and building performance modeling. Computational approaches in this domain facilitate the assessment of window operations under varying environmental conditions, optimizing both thermal comfort and energy efficiency through data-driven analyses.

The Emerging Technologies cluster represents an increasing interest in integrating advanced methodologies to optimize window performance. Keywords such as “intelligent buildings” (50 occurrences, total link strength 510), “sustainability” (29 occurrences, total link strength 864), “green buildings” (20 occurrences, total link strength 227), “sustainable buildings” (7 occurrences, total link strength 61), “machine learning” (22 occurrences, total link strength 235), and “bioclimatic design” (8 occurrences, total link strength 54) highlight the exploration of artificial intelligence, predictive modeling, and sustainable design principles. The incorporation of AI and machine learning is expected to enhance adaptive window control strategies, fostering the development of innovative and effective energy-efficient building environments.

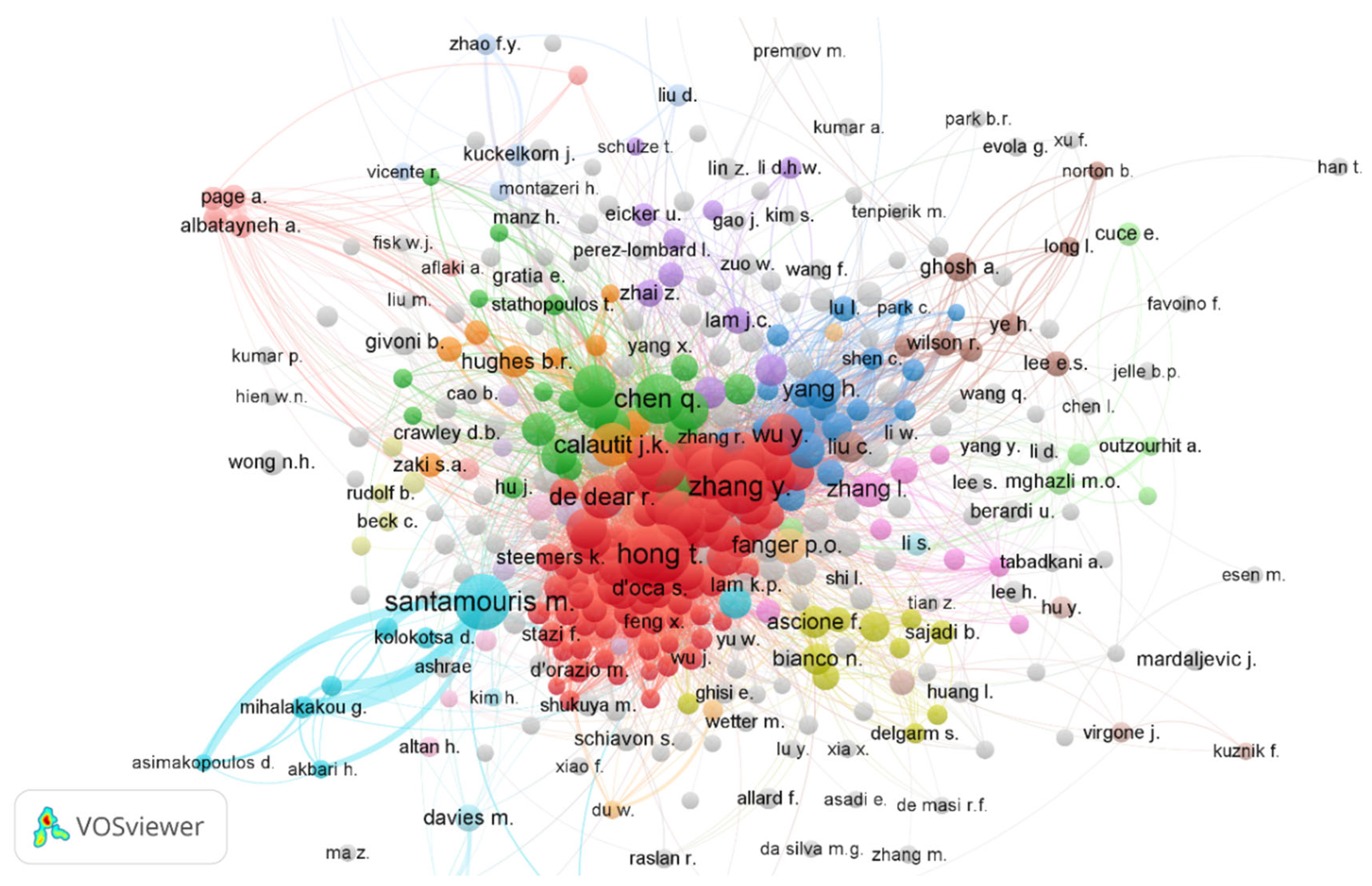

3.2. Key Contributors and Collaboration Networks:

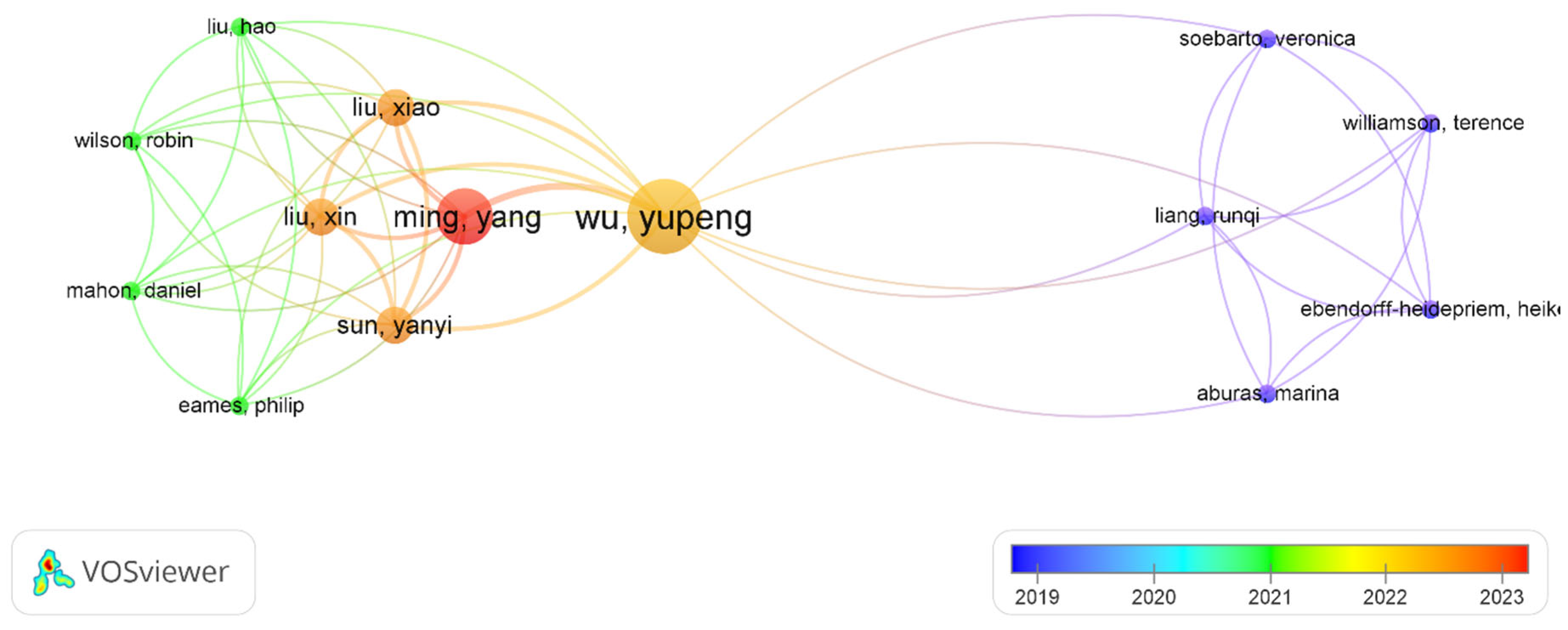

An author co-authorship analysis was conducted to identify influential contributors and collaborative networks in the study of window behavior and indoor thermal comfort. The analysis considered authors with a minimum of one publication and at least ten citations, ensuring the inclusion of impactful researchers. Out of 805 authors, 371 met the threshold, reflecting a relatively small yet highly influential group driving research advancements in this field.

Chen Xi and Yang Hongxing emerged as among the most influential researchers, with five publications and 321 citations. Their extensive collaborations emphasize significant contributions to passive cooling strategies and computational modeling, particularly in advancing simulation-based approaches for optimizing indoor thermal comfort. Malkawi Ali and Wu Yupeng also surfaced as key contributors, with four publications and 562 and 361 citations, respectively, focusing on window performance, energy efficiency, and ventilation strategies. Additionally, Chen Yujiao, with three publications and 558 citations, demonstrated substantial contributions through data-driven methodologies and advanced modeling techniques, further enriching the understanding of window behavior and indoor climate regulation.

The co-authorship network (

Figure 2) illustrates key researchers and their collaborative linkages, revealing a well-structured research community where established scholars actively engage with emerging researchers. The largest connected network comprises 14 authors, demonstrating the extent of research collaboration within this domain. The presence of highly interconnected researchers underscores the dynamic nature of the field, where interdisciplinary partnerships facilitate methodological integration across computational modeling, field measurements, and AI-driven predictive modeling.

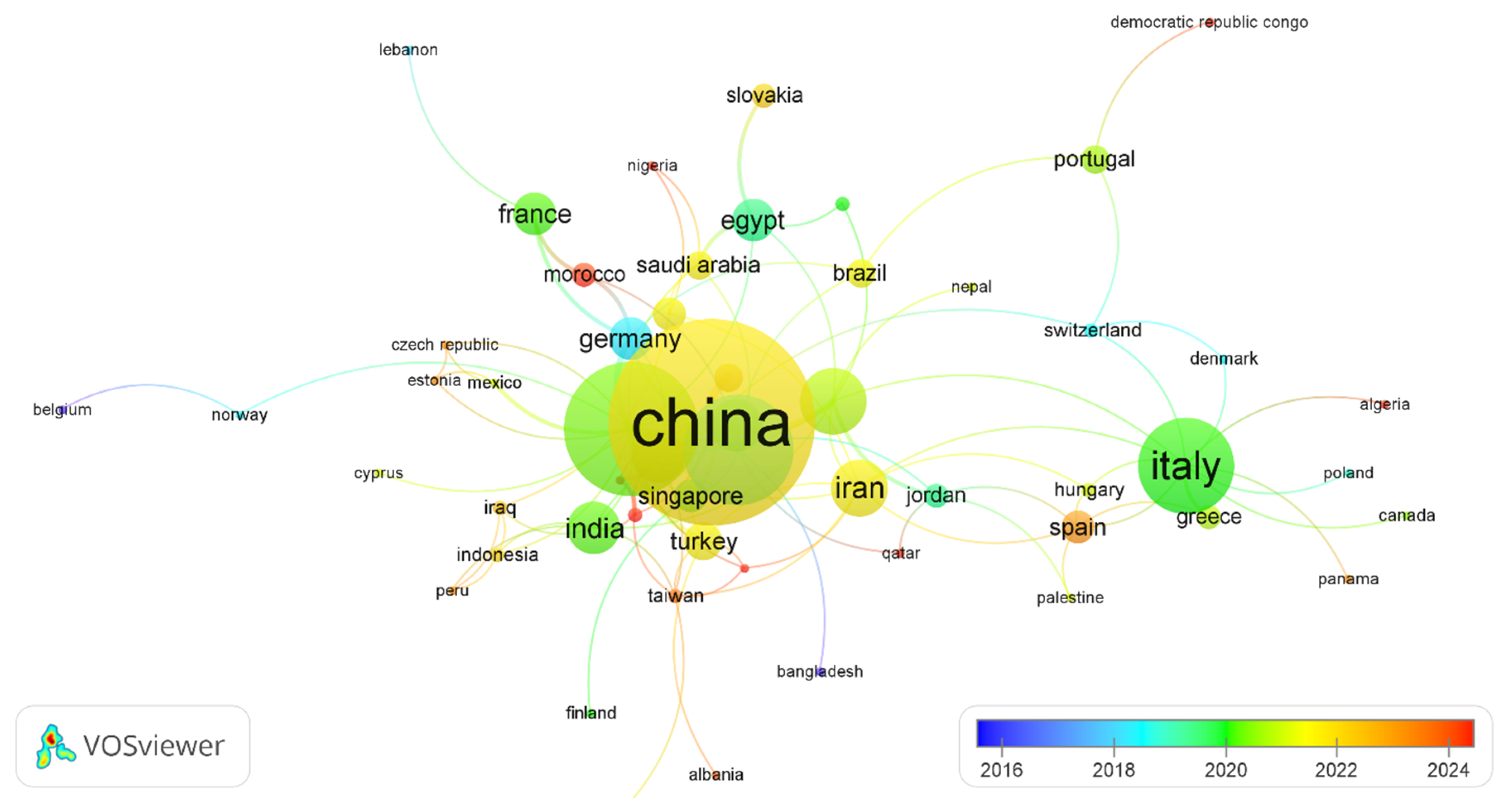

3.3. Global Research Collaboration:

A country co-authorship analysis was performed to explore global collaboration patterns in window behavior research. The analysis, conducted using a minimum threshold of one publication and one citation per country, identified 62 qualifying countries out of 66. The results, visualized in the country co-authorship map (

Figure 3), highlights strong international engagement and a well-connected research network in this domain.

China emerged as the leading research hub, with 43 published papers, 932 citations, and a total link strength of 29, reflecting the country’s strong emphasis on building energy efficiency and occupant comfort. The United Kingdom followed closely, with 28 publications, 1,040 citations, and a total link strength of 28, demonstrating significant contributions to computational modeling and passive cooling strategies. The United States also played a pivotal role, with 23 papers, 1,168 citations, and a total link strength of 14, emphasizing data-driven optimization of window performance and emerging technologies for energy-efficient buildings.

Beyond individual country contributions, strong cross-border partnerships are evident, facilitating knowledge exchange and the development of universally applicable sustainable solutions. The increasing interconnectedness of researchers from different geographical regions underscores the importance of collaborative efforts in advancing the field of indoor thermal comfort and window behavior.

3.4. Publication Trends over Time:

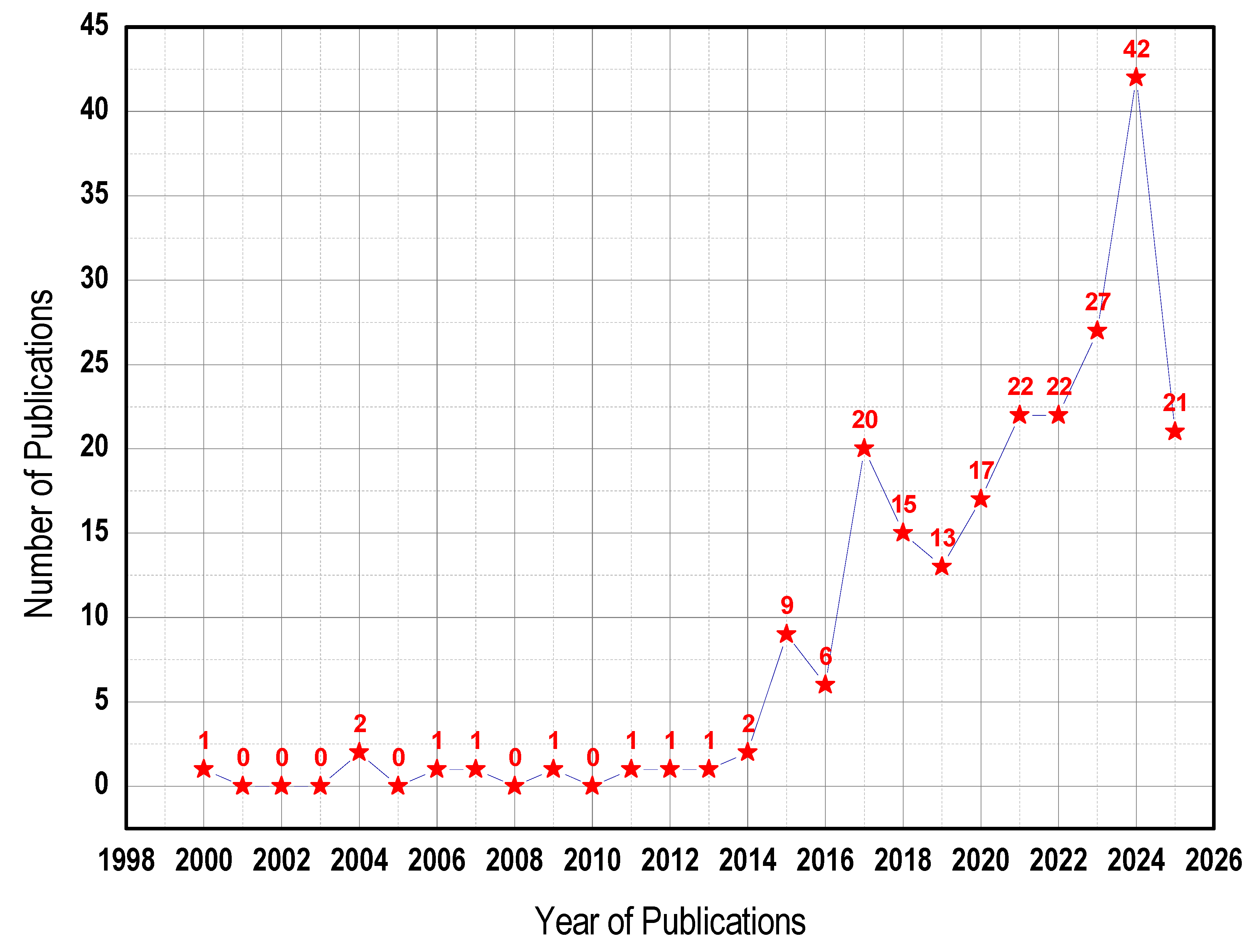

An analysis of publication trends from 2000 to 2025, as illustrated in

Figure 4, reveals a consistent increase in research activity within this domain. The early years, from 2000 to 2011, saw minimal publications, with a peak of two publications in 2004. A gradual increase began in 2012, followed by a sharp rise between 2015 and 2017, reaching 20 publications in 2017. Research output continued to grow exponentially from 2020 onward, with the highest number of 42 publications recorded in 2024. In early 2025, 21 publications have already been recorded, indicating sustained research momentum. The overall trend underscores the growing interest and advancements in window behavior research, particularly in recent years.

3.5. Prominent Journals:.

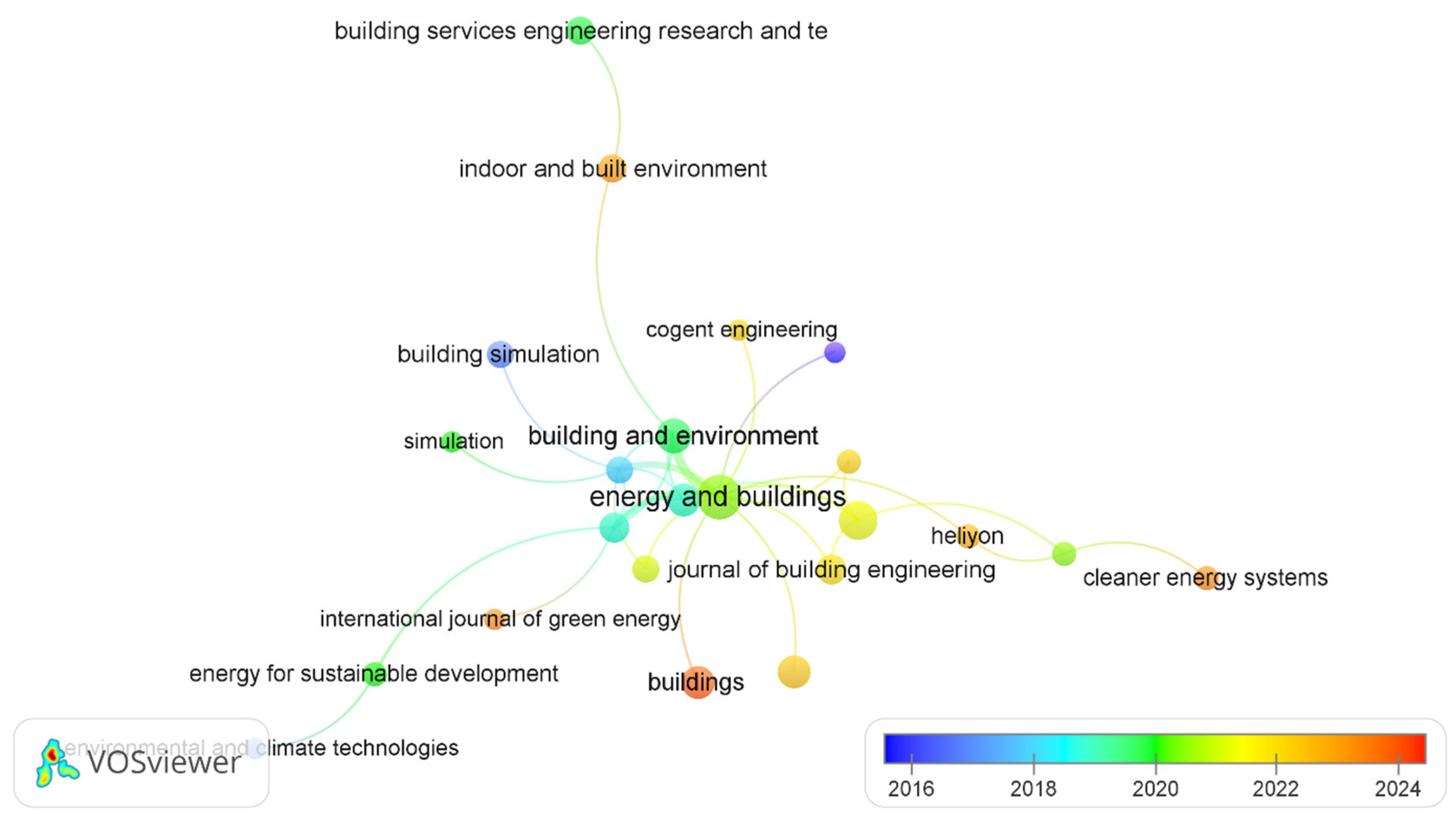

Research on window behavior and indoor thermal comfort is primarily disseminated through several high-impact journals, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The analysis was based on citation counts, with the source counting method applied. A minimum threshold of one document per source and at least one citation per source was set for inclusion. Out of 96 sources, 79 met these criteria, with the largest connected set comprising 23 sources.

Building and Environment follows closely with 11 publications, 465 citations, and a total link strength of 8. This journal is essential in advancing knowledge on indoor environmental quality, building physics, and the interactions between occupants and fenestration systems. It plays a critical role in bridging the gap between theoretical modeling and practical applications of window behavior in various climatic conditions.

Sustainability has published 18 papers with 184 citations and a total link strength of 5, highlighting its growing influence in exploring innovative approaches to optimize window design and operation. The presence of multiple publications in these journals underscores the interdisciplinary nature of the research, which integrates architecture, mechanical engineering, and computational modeling. The concentration of studies in these respected journals reflects the significance of window behavior research within the broader context of energy-efficient building design and indoor thermal comfort optimization.

3.6. Influential Papers:

A co-citation analysis was conducted to identify the most influential studies shaping the field of window behavior and indoor thermal comfort. This analysis was based on co-citation, with the unit of analysis set to cited authors. A minimum citation threshold of 10 was applied, and out of 15,578 sources, 398 met these criteria.

Figure 6 illustrated the strong co-citation links among these studies, emphasizing their pivotal role in establishing the theoretical and empirical foundation for ongoing research in this domain.

Among the most frequently co-cited works are those by Hong T. et al. (91 citations, total link strength 9,082) and Zhang Y. et al. (82 citations, total link strength 5,539). These studies have made significant contributions to the understanding of thermal comfort, building ventilation, and passive cooling strategies. Their findings have provided critical insights into occupant behavior, environmental interactions, and energy-efficient building design, shaping subsequent research directions. The frequent co-citation of these works suggests that they are essential references for researchers exploring window performance, computational modeling, and adaptive comfort approaches.

The identification of these foundational studies highlights the structured evolution of research in this field, demonstrating how past findings continue to influence contemporary advancements. The strong interlinkages between these works indicate a well-established knowledge base that supports ongoing innovations in improving indoor thermal comfort through optimized window operations.

4. Results and Discussions:

The systematic literature review identifies five primary areas of discussion: the historical importance of the relationship between thermal comfort and its indices, the relationship between thermal comfort and window behavior, the role of occupants’ behavior in shaping window operation and influencing design strategies; the connection between window behavior and building energy performance; and the influence of climatic context and thermal comfort on building design strategies within a sustainability framework.

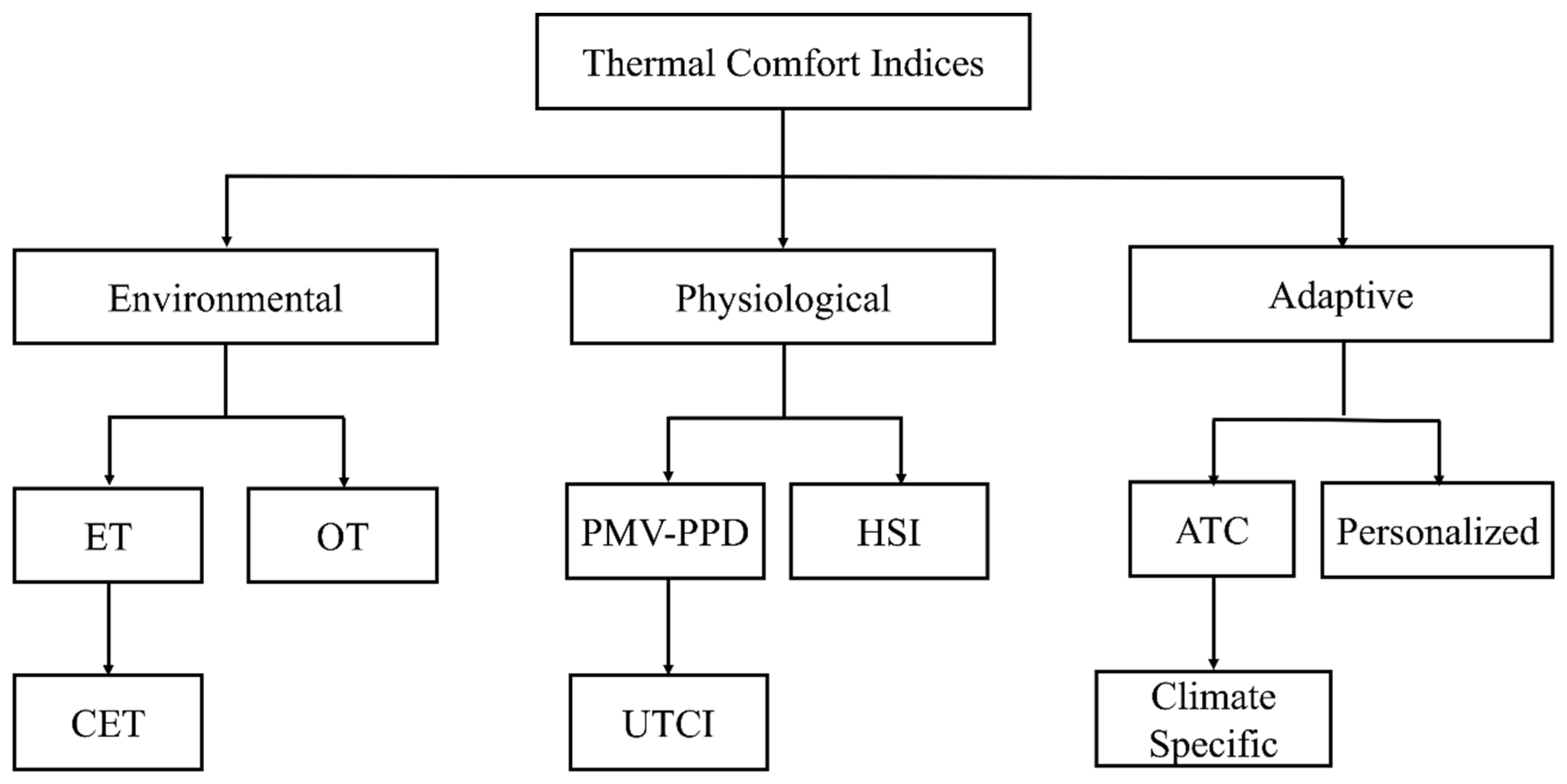

4.1. Historical Significance of Thermal Comfort and Its Indices:

The quantification of thermal comfort has long been a subject of research across various disciplines, including environmental engineering, human physiology, and architectural design. This research has led to the development of numerous thermal comfort indices, aiming to portray the interplay between environmental parameters, such as air temperature, humidity, air velocity, and radiant temperature; and human factors, including clothing insulation, metabolic rate, and behavioral adaptations. These indices have extended from simplistic environmental models to sophisticated frameworks that integrate physiological responses, adaptive behaviors, and real-time data.

Table 2 illustrates a chronological overview of key thermal comfort indices, highlighting their methodological basis, primary developers, and the key contributors and improvements made over time.

To systematically analyze the progression of thermal comfort indices, a taxonomy tree categorizing these indices by methodological approach is presented in

Figure 7. This taxonomy distinguishes between indices based on environmental determinism (e.g., Effective Temperature, Operative Temperature), physiological response models (e.g., P4SR, HSI), human-centric adaptive models (e.g., Adaptive Thermal Comfort, Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) - Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD)), and modern integrative approaches that incorporate real-time data and sustainability considerations (e.g., UTCI, emerging personalized models).

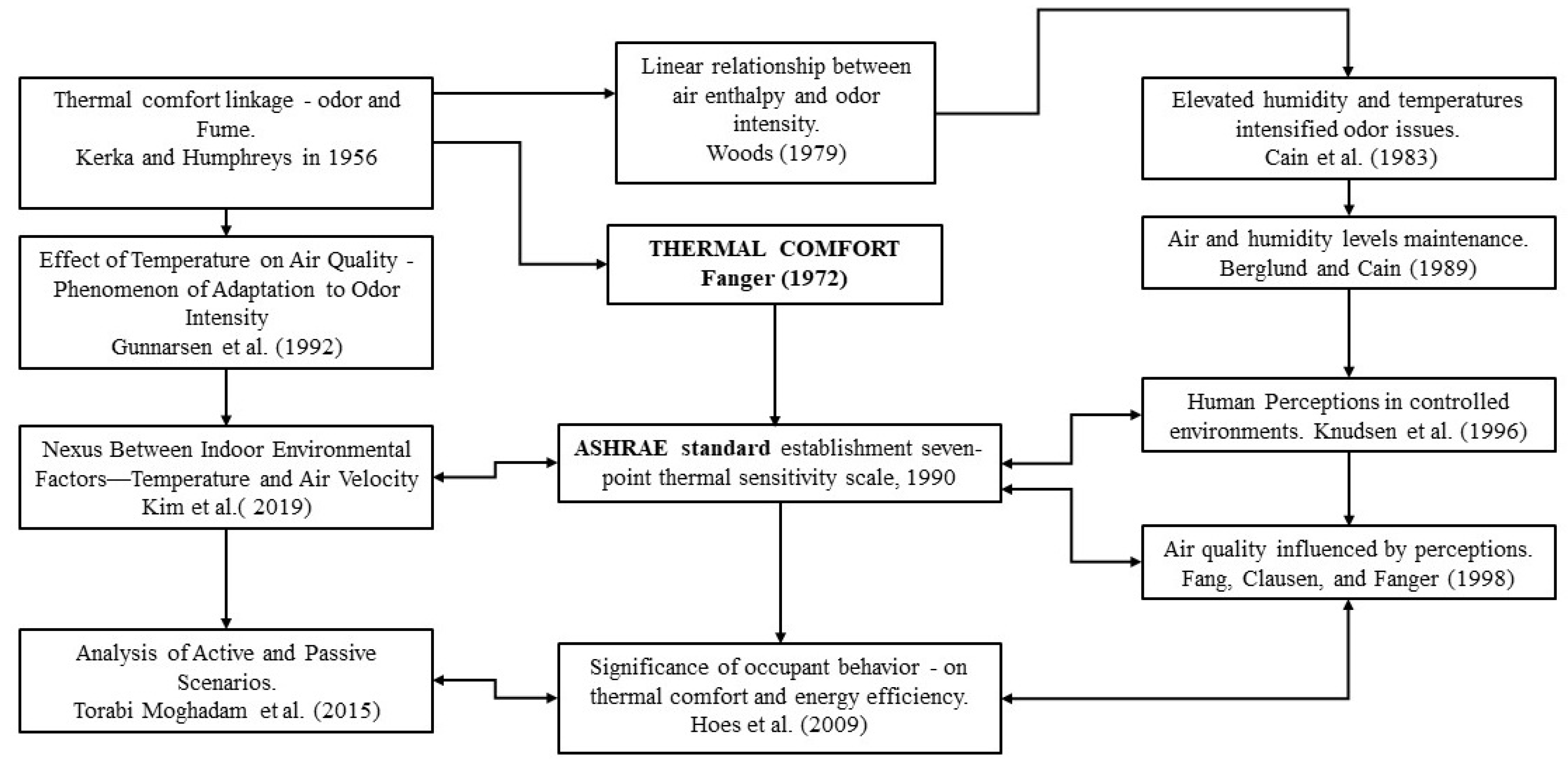

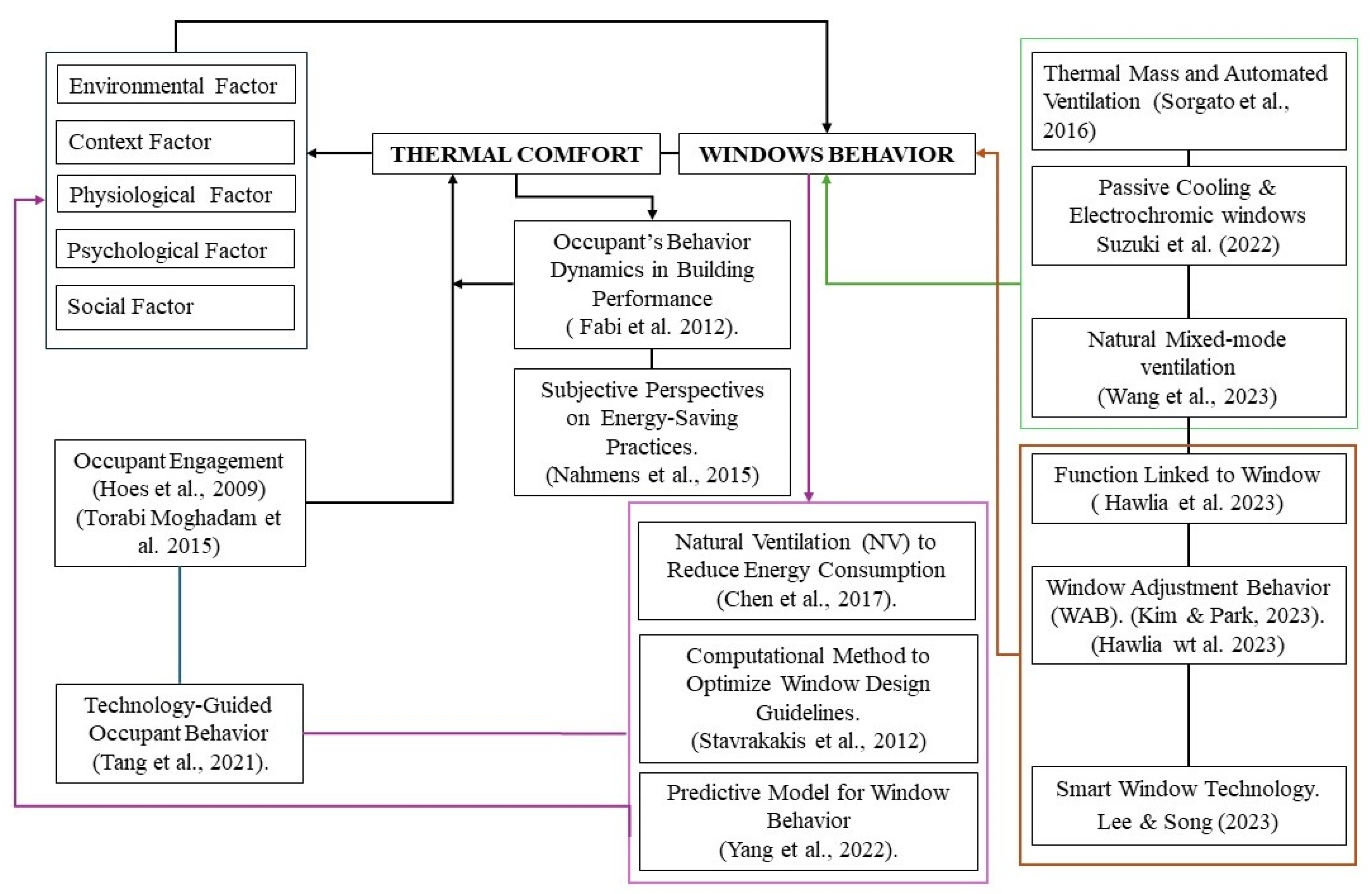

The conceptual framework illustrated in

Figure 8 maps the evolution of thermal comfort research, highlighting key contributions and interlinkages between thermal comfort, air quality, window operations, and smart window technologies.

The study of thermal comfort began with Kerka and Humphreys (1956), who explored the relationship between odor and thermal conditions in indoor environments. Using sensory panels, their study measured the intensity of smoke and fume odors and found that odor strength diminished with increasing temperature for a constant partial vapor pressure and atmospheric humidity. This was followed by Woods (1979), who established a linear relationship between air enthalpy and odor intensity, emphasizing the thermodynamic basis of indoor environmental perception [

39].

Fanger (1972) significantly advanced the field by defining thermal comfort as a state of equilibrium between material and energy. His work introduced the PMV model, which became the foundation for international standards such as ISO 7730 and ASHRAE Standard 55 [

34]. Further advancing the field, Cain et al. (1983) investigated human adaptation to varying air components and found a general decrease in pollutant perception by approximately 2.5% per second until a threshold of 40% was reached. However, no significant differences were found in overall levels of perception [

40]. Berglund and Cain (1989) found that air acceptability remained stable across various humidity levels when the temperature was maintained at 24°C during the initial hour of exposure[

41].

Gunnarsen et al. (1992) reported on adaptation effects, observing a diminished perception of odors over time [

42]. The ASHRAE (1990) standard formalized thermal comfort parameters through a seven-point thermal sensitivity scale, incorporating metabolic rate and clothing insulation [

43,

44]. This comfort equation established a framework for identifying optimal conditions for varying activities and apparel combinations [

45]. Knudsen et al. (1996) [

48] examined human airflow perception in stable thermal environments, whereas Fang, Clausen, and Fanger (1998) [

46] demonstrated that initial air quality impressions significantly influence perception, even in pollutant-free environments. In the following decade, Hoes et al. (2009) [

47] emphasized the critical role of occupant behavior in influencing both comfort and energy efficiency, which was further supported by Fabi et al. (2012) [

48], who highlighted the importance of window operation behaviors. Torabi Moghadam et al. (2015) [

49] made a significant contribution by analyzing active and passive ventilation strategies, offering practical guidance for energy-efficient building design.

4.2. Coalition of Thermal Comfort with Windows Behavior

Windows’ behavior has a crucial role in maintaining healthy thermal comfort in buildings, directly impacting on the air change rate in indoor environments. Window behavior represents the behavior of occupants’ interaction with windows, including activities such as opening, closing, duration, and frequency of use. As illustrated in

Figure 9, windows behavior is strongly influenced by five primary determinants: environmental, contextual, physiological, psychological, and social factors. Environmental factors consider meteorological variables such as RH, wind speed, rainfall, and solar radiation. Contextual factors encompass building features such as area, floor level, window orientation, and user type that affect window operation behavior. Physiological factors link to the comfort levels and health conditions that drive occupants’ choices regarding window use. Psychological factors pertain to individual preferences and behavioral habits that can influence how and when windows are operated. Social factors involve social norms and cultural influences on shape occupants’ behavior regarding window operation [

50].

Numerous studies highlight that window operation, shading control, lighting adjustments, thermostat settings, and appliance usage, as part of window operation, have a direct impact on the air change rate in indoor environments [

50]. As illustrated in

Figure 9, Kim et al. [

50] examined the nexus between indoor environmental factors (operative temperature and air velocity) and outdoor conditions (air temperature and wind gust intensity) regarding window-opening behavior. Their results showed that increased solar radiation elevated indoor wet-bulb globe temperatures, which subsequently influenced the probability of window opening. Additionally, higher outdoor wind gusts produced improved indoor air velocity, thus reducing the likelihood of occupants choosing to open windows.

Yang et al. [

5] developed a predictive model for window-opening behavior in residential buildings in China, employing multivariate analysis. They found that indoor temperature correlated positively with the window opening, whereas indoor CO

2 concentration and outdoor RH were negatively interlinked [

5]. Fabi et al. (2012) [

48] extended the investigation by demonstrating the dynamics of occupant behaviors linked to window operation and emphasized the importance of energy performance in residential buildings.

Understanding the dynamics of occupant behavior and building energy consumption, Torabi Moghadam et al. (2015) [

49] analyzed active and passive scenarios and emphasized the importance of occupant engagement with building control systems on energy outcomes. Wang & Greenberg (2015) [

24] examined the impact of window operations across natural ventilation, mixed-mode ventilation, and conventional Variable Air Volume (VAV) systems in a medium-sized office building. Their results, based on the adaptive comfort standard, confirmed potential HVAC energy savings of 17 - 47% by using mixed-mode ventilation during the summer months across different climates. In a culturally specific context, Foruzanmehr (2015) studied the loggia, a vernacular passive cooling system in Iranian architecture, through user perception. The findings highlight its effectiveness in facilitating passive ventilation and provide guidance for integrating traditional design practices into energy-efficient modern buildings [

51].

In Brazilian residential contexts, Sorgato et al. (2016) [

52]evaluated the window-opening control and the thermal mass of buildings on HVAC energy consumption. The study summarized that buildings with moderate thermal inertia could achieve satisfactory user comfort, particularly when regulated ventilation control mechanisms were in place, thereby significantly curtailing HVAC energy requirements.

Recent advancements in thermal comfort research have focused on integrating smart technologies into building systems. Suzuki et al. (2022) [

53] demonstrated that electrochromic windows could reduce energy consumption by 6.1 - 8.6%, while Lee and Song (2023) [

54] reported that smart window technologies can achieve energy savings of up to 20.5%. Soheil Fathi and Allahbakhsh Kavoosi (2021) [

55] showed that integrating electrochromic windows with advanced glazing, building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) and building energy management systems (BEMS) could result in energy savings of up to 35.57%. Similarly, Zemin He et al. (2023) [

56] found that smart window systems can achieve energy savings as high as 39%, underscoring the growing importance of intelligent, adaptive technologies in modern sustainable building design.

Recent findings suggest that specific factors, including building height, window area, floor level, occupant age and behavior, have a significant influence on window-opening patterns. Hawila et al. (2023) [

50] identified 20 critical drivers influencing window operation and noted the deficiencies in existing research regarding the relationships between these drivers and occupant behavior.

Overall, as illustared in

Figure 9, window behavior is a complex, multi-factor phenomenon influenced by both exogenous and endogenous factors. The integration of advanced materials and intelligent technologies adds new dimensions to decision-making processes for enhancing thermal comfort and improving building energy performance.

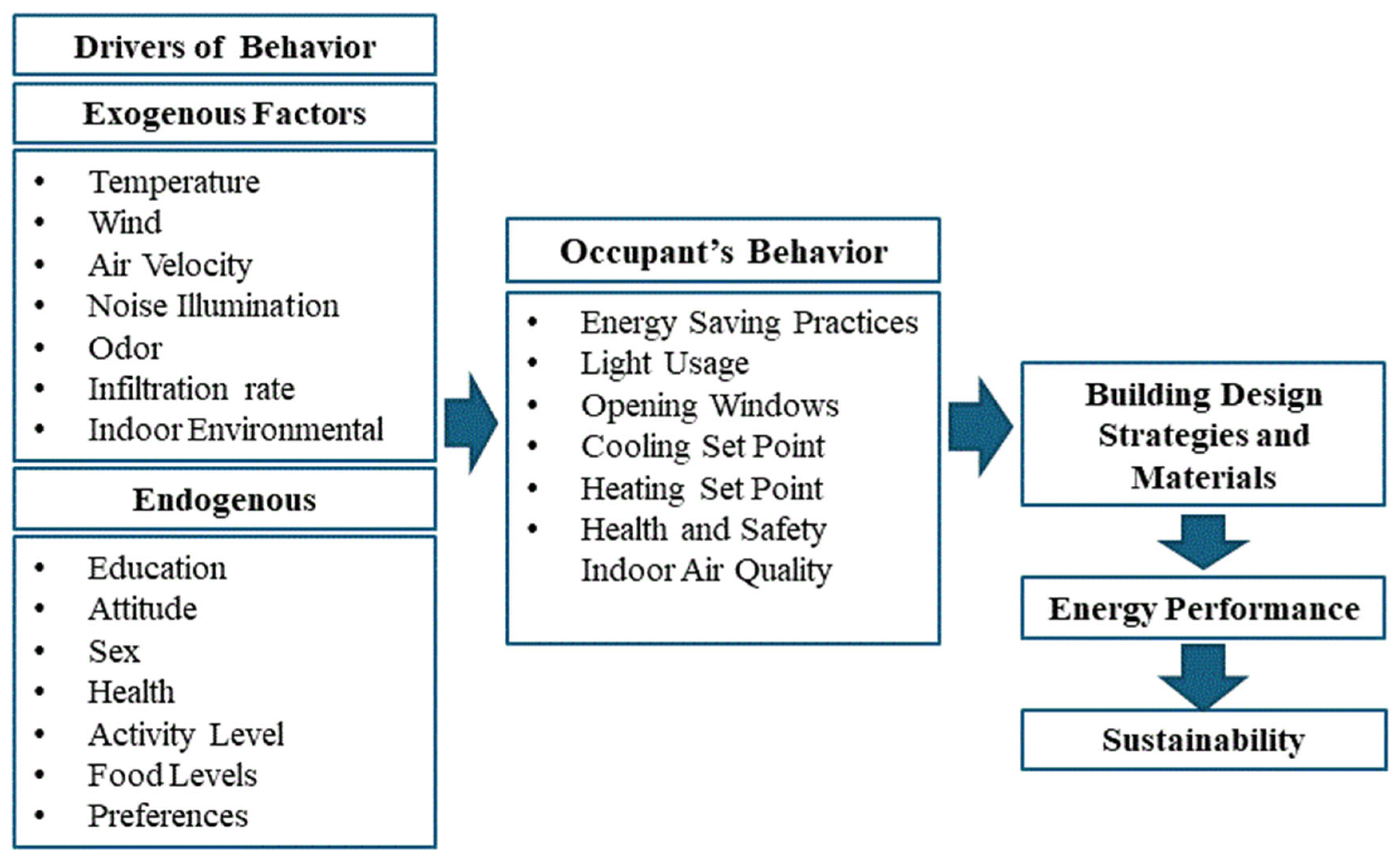

4.3. Role of Occupants’ Behavior in Window Behavior and Design Strategies:

Occupants and their activities have a stronger role in window opening and closing behavior linked to building design. These activities have significant influence on indoor environment conditions such as, thermal comfort, air quality, lighting and noise – through the occupants control actions.

Hoes et al. (2009) [

47] explored the impact of occupant behavior on building performance and highlighted the importance of considering such behavior in the design process. Their study showed that occupant activities can substantially affect environmental conditions within buildings and that control actions taken by users are critical in maintaining comfort. Furthermore, simple design evaluations using numerical tools can provide valuable insights into how users interact with buildings. The study emphasized the importance of accounting for both current and anticipated occupant behavior in simulation models to optimize overall building performance.

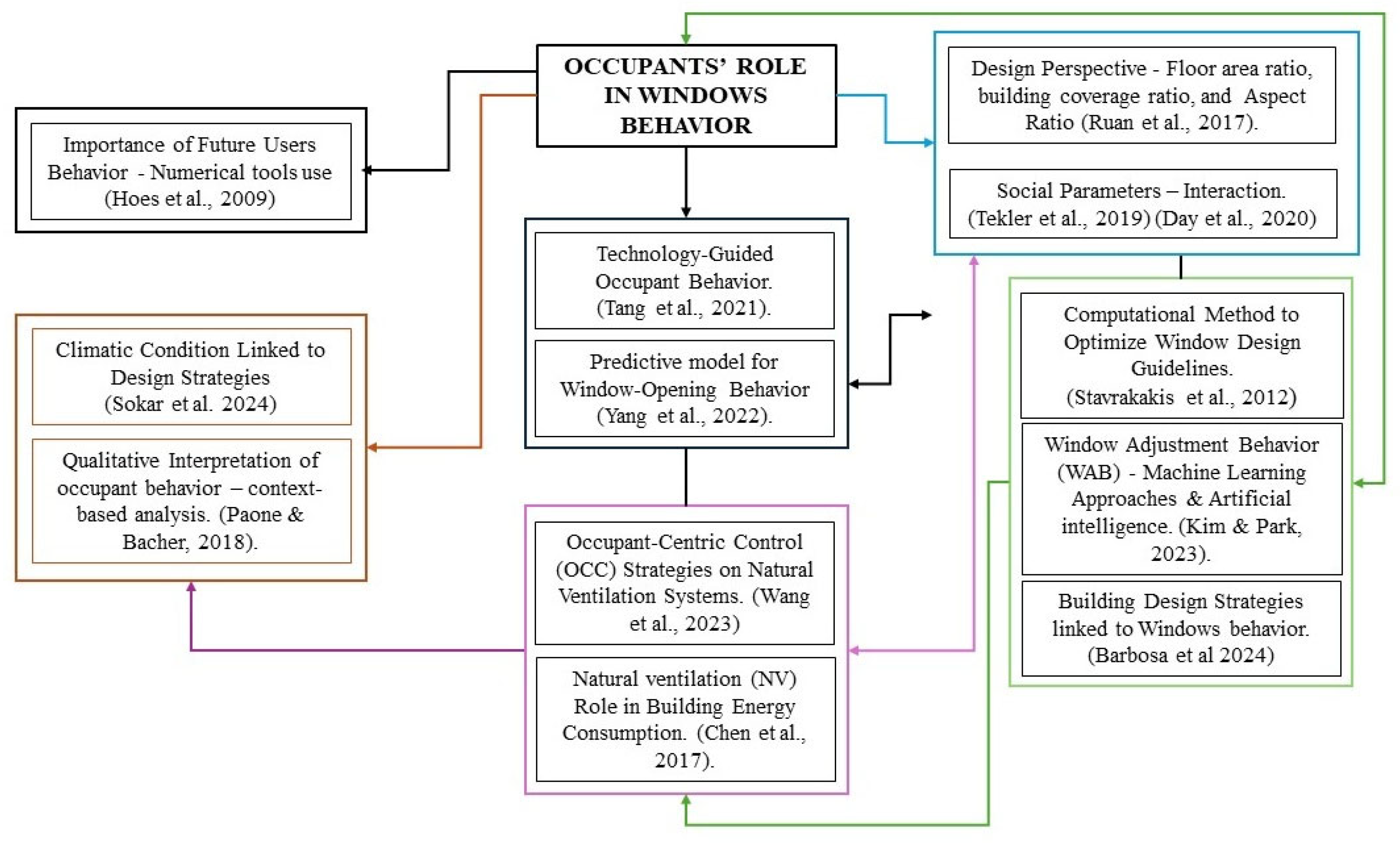

As illustrated in

Figure 10, existing research identifies two main categories of drivers shaping occupant window-use patterns. Exogenous factors deals with outdoor environmental conditions and indoor air quality. While endogenous factors links with contextual elements, psychological influences, and personal preferences. These factors have a direct impact on occupants behavior and thermal comfort influencing to building energy performance with the use of appropriate building design strategies and materials to achieve sustainability.

Reinforcing this linkage, previous studies demonstrated that outdoor temperature has a strong effect on occupants’ behavior on frequency of opening windows [

48,

58]. Research showed that external temperature alone conveyed more than 70% of the variations in the number of ventilation and windows opening, and 10% could be associated with wind speed [

59]. Similarly, Wallace et al. (2002) [

60], Herkel et al. (2008) [

61]; Yun et al. (2008) [

62] uncovered a strong seasonal effect impact on windows opening and closing patterns.

Ruan et al. (2017) [

63] investigated the role of occupant behavior in low-carbon-oriented community planning and found that the age of occupants may significantly affect dwelling time and air conditioner use. They emphasized that urban planning design parameters such as floor area ratio, building coverage ratio, and aspect ratio are essential to add to energy simulation models. The study also highlight that the building aspect ratio is more important than its height for space cooling and heating, with the optimal aspect ratio depending intensely on occupants characteristics and the type of HVAC system. Older occupants, who generally require more heating energy, are better suited to buildings with a lower aspect ratio. Likewise, communities with a district heating system and a decentralized cooling system need a lower aspect ratio than those with other types of HVAC systems. These findings, illustrated in

Figure 11, offer valuable guidance for integrating occupant behavior into low-carbon residential community design.

In technology-integrated contexts, Tang et al. (2021) [

64] investigated the coordination between occupant behavior and energy-efficient technologies, introducing the concept of “technology-guided occupant behavior” to enhance building energy control systems. In a Hong Kong study, such guidance reduced central air-conditioning energy by 23.5%, which accounts for the inconveniences of occupants due to the interference of technologies.

Similarly, Wang et al. (2023) [

65] focused on Occupant-Centric Control (OCC) strategies for natural ventilation using AI powered cameras and deep learning to capture real-time occupant profiles and window operations. Their findings showed heating energy savings of 0.6–29% and indoor comfort improvements of up to 58.8% compared to conventional strategies.

To advance new applications in window operating system, window adjustment behaviour (WAB) has neen identified as a critical factor in predicting building energy consumption. Numerous studies have undertaken to develop a reliable WAB model that considers three key issues: reliance on an “average occupant” fashion, which overlooks variability of individual preferences, the need to assess how occupants respond to both environmental and non-environmental factors and the diversity of predictive modeling approaches, including probabilistic methods and machine learning techniques, each with distinct strengths and limitations in terms of adaptability, complexity, and explainability. In this contexts, Kim & Park (2023) [

66] focused on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) to quantitatively examine these issues. Their findings revealed that WAB influenced by the following factors. First, different people have different personal preferences for window operation and employing customized WAB model is better than a universal one. Second, the personal preferences of occupants on WAB cannot be labelled by a single environmental factor because WAB is an responsive to environmental, psychological, social, and other undefined factors. Finally, the current complex black-box model can be elaborated by applying XAI techniques regarding feature influence.

From an optimization perspective, Stavrakakis et al. (2012) [

12] presented a computational method to optimize window design, achieving thermal comfort in naturally ventilated buildings along the design guidelines. The proposed methodology provides optimal window designs that correspond to the best objective variables for both single and multiple activity levels.

From a design perspective, Barbosa et al. (2024) [

67] studied semi-detached houses and showed that improving occupant behavior could lead to energy savings of 4 - 30%. Building simulations revealed that unoccupied rooms experienced a variation of up to 7% in discomfort hours while lighting usage varied by approximately 4%. Solar orientation significantly impacted energy consumption patterns, with the north-facing orientation performing superiorly in 79% of cases evaluated, compared to south-facing orientations (21%).

As illustrated in

Figure 11, occupants activities have a stronger role in window behaviour; however, as technology development and use of machine learning system have enhanced WAB to improve thermal comfort. It has helped to improve building design perspective and strategy development for the sustainable approach. Influencing strategies linked to building occupant behaviors include eco-feedback, social interaction, and gamification. For instance, Paone & Bacher (2018) [

68] emphasized that maintaining energy-efficient behavior without compromising the comfort of building occupants endures a challenge despite the development of new technologies and strategies. Thus, understanding occupant-driven window operation and its impact on building energy savings is imperative for achieving sustainability in a holistic approach.

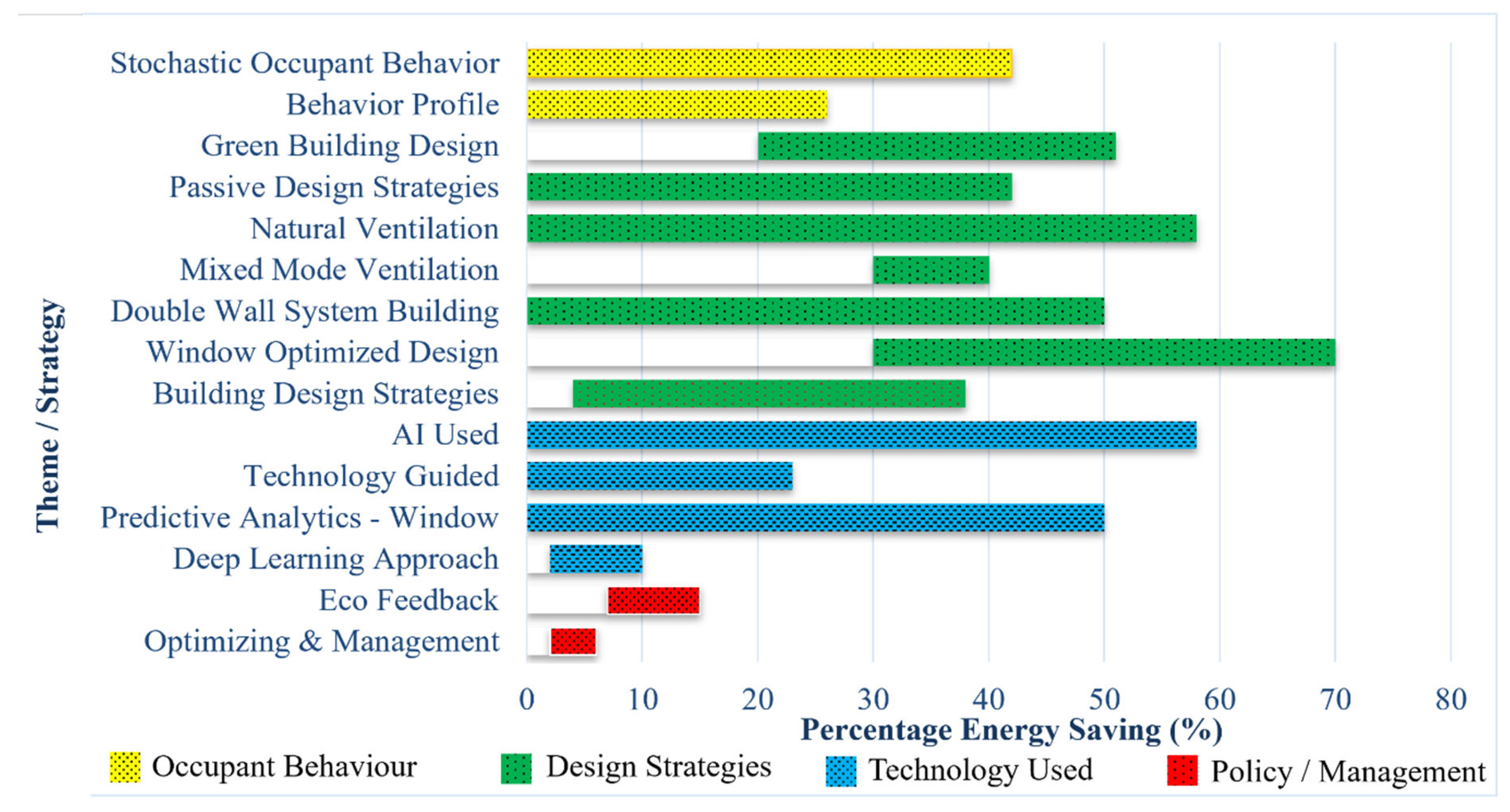

4.4. Window Behaviour Linked to Building Energy Performance:

Studies showed that user behavior can improve energy efficiency and different design strategies can support to enhance window behavior [

68]. Hawila et al. (2023) [

25] investigated occupants’ window-opening behavior in office buildings and found that the frequency of window openings declined when outdoor temperatures exceeded 27°C. In contrast, the probability of opening windows increases significantly at outdoor temperatures above 20 °C. Complementary studies employing artificial neural networks for natural ventilation control have indicated that the likelihood of window opening becomes minimal when indoor temperatures drop below 24 °C. The preferred indoor temperature range for ventilation comfort in Japan was identified as 24-30 °C [

69].

Recent research highlights the substantial impact of occupant behavior on window operation patterns and overall building energy consumption across various climatic and building typologies. Yoon et al. (2024) [

70] developed an innovative window scheduler algorithm that explored natural ventilation and thermal mass to optimize energy use and control smart home environments, demonstrating the ability to manage window operations and reduce energy consumption, maintaining indoor comfort. Similarly, El Khattabi et al. (2024) [

71] analyzed the impact of shutter control in double-walled residential buildings using the NoMASS simulation framework. Their results showed that shutter operation reduced solar gains through windows by 13% and decreased occupant discomfort by 52% via enhanced natural ventilation. However, the NoMASS model elevated 65% heating requirements compared to the Standard Fixed Scenario (SFS), exploring the trade-offs inherent in passive cooling strategies as illustrated in

Figure 12.

The evolution of predictive analytics, employing deep neural networks, has enabled the forecasting of window opening behavior and its impact on HVAC energy consumption. Pandey and Dong (2023) [

72] reported a 50% reduction in monthly cooling energy when the indoor setpoint temperature was increased from 20 °C to 27 °C in Sub-Saharan Africa. Their UK-based study achieved an accuracy of 77.8% in predicting window states. Furthermore, simulations conducted across five U.S. cities showed that mixed-mode ventilation strategies could achieve cooling energy savings ranging from 45% to 94%. Temperature thresholds have a significant influence on window operation patterns. It is also observed that window openings become more frequent when outdoor temperatures exceed 12°C, with prolonged openings above 28 °C. The probability of a bedroom window opening crossing the Behavioral Likelihood Ratio (BLR) threshold of 0.50 lies within the 13 -19 °C range, whereas living room windows reach this threshold between 26 °C and 27 °C.

In educational settings in Budapest, Belafi et al. (2018) [

73] found that window-opening behavior was driven more by occupant activities rather than environmental parameters. Their study highlighted that incorporating dynamic occupant behavior simulations and adopting behavioral profiles could reduce ventilation energy consumption by up to 26%. Furthermore, Naspi et al. (2018) [

73] analyzed the probability of window opening relative to indoor temperatures. While compared standard versus behavioral ventilation patterns, the discrepancy was notably higher in north-facing oriented classrooms. Employing behavioral profiles has improved modeling by 28 % energy saving. Roccotelli et al. (2020) [

74] evaluated stochastic occupant behavior for building energy management, highlighting that passive strategies such as natural ventilation and solar shading could reduce energy consumption by an average of 42 %. Additionally, Tien et al. (2022) [

75] utilized a deep learning approach for real-time occupancy and window activity detection, achieving 85.63% accuracy in occupant activity recognition and 92.20% for window operation detection. Their findings suggest that 2–6% of HVAC energy savings are feasible through optimized occupancy and window management.

In addition, the comparative analyses between green-rated and non-rated buildings revealed that occupant behavior exerts a more pronounced impact on energy consumption in non-green buildings. Almeida et al. (2020) [

76] observed that occupants in non-rated buildings had an 11% greater influence on cooling energy use compared to occupants in green-rated counterparts. Occupants in non-rated buildings also exhibited a higher propensity to open and close windows - 36% versus 51% in green buildings—contributing to an overall 6% higher energy consumption attributable to occupant behavior as shown in

Figure 12.

Eco-feedback programs have shown promise as behavioral interventions. Paone & Bacher (2018) [

68] reported energy savings of 7 - 15% as illustrated in

Figure 12. Eco-feedback is an effective way to influence behavior, and gamification presents a new prospect to elicit behavioral change. The factors affecting human behavior are numerous and multi-fold approaches are needed to provide new insights into the activity dynamics of occupants’ energy behavior. In addition, Paleni et al. (2023) [

77] emphasized the importance of different occupant behavior group based on socio-demographic and economic characteristics and their energy-use profiles to better control and monitor building energy consumption, such as gender, age, and education, which also impact efficient living behavior as a process. For the energy saving intervention as behavior transformation, incentives to occupants are prone to change to keep their good energy consumption behavior.

As illustrated in

Figure 12, technology-guided and AI building modelling can improve energy performance up to 23 - 58%. While using different building design strategies (window optimization, double glazed window, mixed mode ventilation,etc.) can improve energy saving by up to 30 - 70%. Currently, reviews claim to have insights into the multifaceted nature of occupant interactions with windows and their impact on building energy performance. It demands extensive research to adopt a holistic approach to address existing knowledge gaps and grasp the comprehensive variety of factors interacting in different climatic contexts and influencing window operation and occupant behavior to achieve sustainable approaches.

4.5. Climatic Context, Thermal Comfort Linked to Building Design Strategies and Sustainability Approach :

Appropriate thermal comfort design strategies may vary depending on different climatic contexts and have varying impacts on building energy performance. The evaluation and effectiveness of different bioclimatic design strategies on building energy performance in various climatic contexts and their sustainability are important to understand, especially after revealing the crucial role of occupant behavior in window operation. This understanding is crucial for maximizing energy efficiency and promoting sustainability.

In Mediterranean climate, Elaouzy & EI Fadar (2022) [

78] demonstared that an increased window-to-wall ratio leads to a lower annual heating requirement but also a higher cooling demand due to increased solar heat gain. However, a more extended overhang depth can reduce the cooling load. The study also revealed that cooling loads increase and heating loads decrease with the augmentation of solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC). Similarly, windows with a high SHGC is recommended for areas with a cold climate. The effective strategy in the building to increase thermal performance is the addition of thermal insulation. The study suggested that by initiating new regulations and encouraging programs that provide efficient and advanced materials at lower prices can motivate citizens to adopt bio-climatic designs with shortened payback periods. This contributes to improving countries’ sustainability in mitigating climate change with significant cost savings.

Hany & Alaa (2021) [

79] examined bioclimatic strategies in Alexandria, Egypt, focusing on architectural elements like low-pitched roofs and chimney vents, which improved thermal comfort by up to 13% in winter and 12.6% in summer. The results revealed that improvement on the passive design for cooling is more important compared to heating that allowed wind flow for maximum natural ventilation using chimneys and other similar elements. Similarly, the use of ventilated pitched roof spaces is more beneficial for cooling the house. The sun shading elements such as pergolas and projected porches in the proper facades and angles can advantage of the sun protection elements as well as the architectural aesthetics, preferably moveable and interchangeable shading elements to function in both summer and winter. The research also suggested that exploring the socio-economic impacts of implementing bioclimatic designs and investigating their scalability in urban contexts is crucial as illustrated in

Table 3 [

79].

In hot and humid climate, Chen et al. (2017) [

80] conducted a parametric study of passive design strategies in high-rise residential buildings, incorporating sensitivity analysis to consider multiple indoor environmental indices and impact factors related to natural ventilation. The results showed that the window SHGC, window-to-ground ratio, external obstruction angle, and overhang projection fraction are the most influential factors over the indoor illuminance level, operative temperature, humidity ratio, and stable comfort. Similarly, Alibaba (2016) [

81] in Famagusta, Cyprus focused on optimizing the window-to-wall ratio and window opening percentages for a naturally ventilated room. The study revealed that horizontal shading is more effective than vertical shading in reducing energy consumption and providing better solar radiation, especially during the summer months. The most optimal window opening percentage for thermal comfort is approximately 20 %. Both studies suggest that combining WWR, shading devices, and natural ventilation strategies is essential for designing energy-efficient buildings in hot and humid climates.

For temperate and arid zones, Miao et al. (2024) [

82] revealed that Sustainable Architecture for Future Climates in Multi-Objective Design focuses on optimizing the parameters of building elements. The parameters including cooling and heating setpoints, air change rates, shading device depths, window visible transmittance, and window types are considered to balance energy consumption and comfort. These parameters are based on simulations using future weather data for the years 2020, 2050, and 2080. The results demonstrated a discernible trend towards increased cooling energy consumption and discomfort hours, likely due to rising temperatures, underscoring the need for climate-responsive building designs and efficient cooling systems. At the same time, the heat energy pattern suggests the need for adaptable heating solutions. It emphasized the importance of sustainable and resilient architectural practices that prioritize both energy efficiency and occupant comfort, responsive to climatic conditions. Balancing the solar transmittance with advanced shading and glazing technologies is crucial in optimizing energy efficiency and comfort in future-proof building designs.

Harkouss et al. (2018) [

83] explored the passive design optimization across in different cold, temperate, and hot climates through an implementation approach in four phases of building energy simulation; optimization; Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM); sensitivity study; and finally, an adaptive comfort analysis. Their results indicated potential energy savings of up to 54% in cooling, 87% in heating, and 52% in lifecycle costs through optimized building envelope [

83]. Notably, severely cold regions require high insulation (walls, roofs, ground U-values ~ 0.2 W/m²K), while hot climates benefit from moderate insulation levels. Mixed climates require balanced insulation, allowing ground heat evacuation in summer. Kim et al. (2024) [

84] outlined the optimized themal comfort and sustainability approach through passive cooling and eco-friendly materials for Indoor Temperature Reduction. Wood and red clay brick as building materials in building construction has the potential to mitigate the temperature effect with the provision of natural ventilation. The time it took for the wood to reach 26 °C from the initial experiment temperature of 30.7 °C was 9 hours, while the time for the red clay brick was 8 hours. Similarly, use of lower window ventilation system resulted in a slower air exchange rate compared to a standard side window, indicating that both the size and placement of the window play critical roles to improve effective natural ventilation.

New technologies are also shaping sustainable building design. Nguyen et al. (2025) [

85] evaluated algae-based window systems, which can reduce energy costs by up to 12% compared to single glazing and mitigate up to 20% of overall energy consumption in buildings like the World Trade Center skyscraper. Public awareness and supportive policies are vital for adopting such innovations. Nadarajan and Kirubakaran (2017) [

86] explored the potential of sustainable building materials to enhance thermal comfort in Indian residential buildings, with a focus on stabilized mud block-walled construction. Their study highlighted that mud block walls effectively minimize heat conductivity from the external environment to the interior, enabling self-cooling properties in buildings. The study employed CFD analysis in ANSYS to assess the suitability of various sustainable materials for walls, roofs, floors, and other building components to enhance comfort in housing and promote sustainable development in the rural building sector. A comparative analysis of model rural residential houses revealed that a home with burnt brick walls and another with mud block walls exhibited an average air temperature difference of 0.7°C, a maximum local temperature difference of 6°C, and an average wall temperature difference of 3°C.

Ebuy et al. (2023) [

87] conducted a review focusing on building sustainability performance from the construction to the design stage, analyzing energy consumption patterns. Menezes et al. (2012) [

88] and Ledo et al. (2020) [

89] found that discrepancies between actual and expected energy consumption in functional buildings, such as schools, offices, and universities, ranged from 60% to 85%. Yan et al. (2015) [

90] noted that occupant behavior can lead to differences in building energy performance as high as 300%. While Sonderegger (1977) [

91] suggested that oversimplifying occupant behavior models can result in variations in energy demand of up to 70%. Erickson et al. (2016) [

92] highlighted that integrating real-time occupancy data into HVAC work schedules can achieve annual energy savings of 42%. Yousefi et al. (2017) [

93] noted that variations in heating and cooling demands in residential buildings due to changes in window types could reach up to 20%. To illustrate the influence of occupants, Gaetani et al. (2016) [

94] and Muroni et al. (2019)[

94] demonstrated that refining occupant behavior models improved total electricity consumption predictions, reducing the average deviation from measurements from 22.9% to 1.7% when comparing ideal and worst-case scenarios. Similarly, Klein and Kavulya (2012) [

95] found that integrating modeling and simulation tools for occupant behavior—specifically controlling lights, windows, shades, and temperature set points - can enhance occupant comfort by 5%.

Gladdys et al. (2025) [

96] investigated the sustainable strategies for humanitarian housing in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of Burundi. The study highlighted the impact of wall material reflectance and window-to-floor ratio (WFR) on daylight and thermal comfort. A WFR of 20%, with well-placed windows, improved light distribution and glare control. The prototype shelter showed a 52% boost in material efficiency, 37.15% increase in energy efficiency, and reduced CO₂ emissions (0.04 tons/month/house). Adobe walls improved thermal comfort by 20 - 24% during peak heat hours, while reflective materials and roof overhangs helped maintain indoor temperatures between 20°C and 25°C for 80% of occupancy. The study emphasized the importance of using local materials suited to the climate.

Yousuf and Taleb (2018) [

97] conducted a simulation-based study on UAE residential buildings, showing that double and triple glazing reduced cooling loads by 8.63% and 13.22%, and in solar heat gain by 16.7% and 28.3%, respectively. Electricity consumption was also reduced by 5.1% and 7.7%. Their study emphasized meeting a minimum daylight factor of 2% or 200 lx for 20% of living space under the Pearl Rating System. Tzempelikos and Athienitis (2017) [

98] demonstrated that shading devices can save total energy by up to 50% while preventing at least 12% of solar and heat gain. Palmero-Marrero and Armas (2010) [

99] found that vertical louvers are more effective for east and west façades, while horizontal louvers optimize energy efficiency on south façades. Ebrahimpour and Maerefat (2011) [

100] reported that external shading devices, such as overhangs and side fins, outperform advanced glazing (e.g., double clear pane or low-E pane) for windows in any orientation. Lai (2011) [

101] and Zhu (2006) [

102] showed that improved wall insulation and window shading could achieve energy savings of 11.31% to 11.55% in air-conditioned buildings. Cuce et al. (2019) [

103] nalyzed sustainable ventilation strategies in Chinese university buildings using CFD. The study found that natural ventilation could reduce annual cooling and heating energy use by up to 55% compared to mechanically ventilated buildings. Improved ventilation also boosted annual productivity by 3–18%. Even without solar chimneys, cross-ventilation via windward and leeward windows provided effective airflow. However, passive cooling alone was less suitable in extreme climates or polluted areas. In such cases, hybrid systems—combining natural and mechanical ventilation—were recommended. The study also noted CFD limitations, as it doesn’t account for conduction and radiation, limiting accurate simulation of combined ventilation effects.

Chen et al. (2017) [

104] explored the potential of natural ventilation to improve indoor conditions and energy efficiency, noting that effectiveness varies by region. Using Building Energy Simulation (BES) across 1854 locations in the 60 largest cities worldwide, they found that subtropical highland climates - such as in South-Central Mexico, Southwest China, and the Ethiopian Highlands - are most suitable for natural ventilation due to stable, mild weather. Mediterranean climates also showed good natural ventilation potential, while desert regions benefited from night-purge ventilation. In contrast, hot and humid regions like Singapore and Malaysia offered little to no natural ventilation potential. These insights guide climate-specific natural ventilation strategies. Sokar et al. (2024) [

105] examined hot semi-arid climates and found that dehumidification is crucial when humidity exceeds 70%, especially during cool mornings. Maintaining humidity between 30–70% and temperatures between 18–28°C or 20–26°C reduced annual thermal loads to about 22.3 kWh/m², compared to 56 kWh/m² in uncontrolled settings. The study emphasized the impact of occupant behavior on indoor environmental quality and energy use.

5. Existing Research Trends and Methodological Limitations (Gaps):

As outlined in Section 2, a refined dataset of 112 studies formed the basis for analyzing methodological limitations and research gaps in the field of window technologies and occupant-window behaviour. Building upon the findings presented in

Section 4, this review highlights key research trends and persistent shortcomings. Although bibliometric and scientometric analyses indicate a rapidly expanding research field with increasing interdisciplinary collaboration, several imbalances and omissions constrain the generalizability and applicability of existing findings. The analysis of these 112 studies reveals distinct pattern in research approaches, limited climatic and contextual diversity and insufficient focus on demographic and spatial considerations.

Approximately 33.03% of the reviewed studies relied solely on simulation tools such as EnergyPlus, CFD, and DesignBuilder to assess window performance and thermal comfort, while only 16.96% combined simulations with experiments. Additionally, 21.42% studies accounted for algorithm-based approaches. This distribution reveals a clear imbalance, with the majority of research depending on simulated or model-driven data. Although simulations and algorithms provide valuable control over variables and experimental flexibility, they often fail to capture the complexity and variability of real-world occupant-window interactions. The comparatively lower proportion of exclusive experimental studies (18.33%) and hybrid approaches highlights the need for more field-based validation and integration of empirical data into models to improve reliability and real-world applicability.

Out of all studies, 43.75% incorporated empirical behavioral data, yet only 2.67% combined such data with statistical prediction or analysis methods. This limited integration of behavioral insights into predictive models contributes to the persistent gap between modeled and observed window operation patterns.

Climate diversity represents another significant research gap, with fewer than 9.82% of studies validating findings across multiple climatic zones. While some research focuses on specific climates, such as hot and humid (e.g. Hong Kong and Sudan) or temperate regions (e.g. Romania and China), cross-climatic validation are rare. This limitation is also reflected in collaboration networks showing minimal co-authorship between researchers working in different climatic regions, hindering the development of globally applicable window solutions.

Demographic variables, particularly gender, are significantly underexplored. Only

3.57% of research addresses gender-specific factors, despite well-documented differences in thermal comfort preferences - for instance, women generally prefer indoor temperatures 1-2°C warmer than men [

106,

107,

108,

109,

110]. Similarly, spatial-functional differentiation remains largely overlooked. Only

12.5% of studies specifically analyze rooms with unique thermal and ventilation demands, such as kitchens or utility areas. This oversight restricts the practical applicability of current models, particularly in multifunctional or high-load thermal zones.

Table 4 illustrated a quantitative overview of these methodological and contextual research gaps. It categorizes the gap into five domains: simulation reliance, behavioural data integration, climate diversity, gender-specific analysis, and room-specific design. Each category includes the percentage of studies addressing the gap and exemplar studies.

6. Emerging Trends in Research and Development:

The previous section highlighted the connection between thermal comfort, window behaviour and sustainability. Current research in thermal comfort is broad, lacking the necessary depth in specific areas. To address this, future research needs to expand into specific sub-themes of energy, indoor air quality, technology, and economic perspectives on window behavior for enhanced sustainability.

Table 5 provides a structured overview of key research themes, associated sub-themes, and existing gaps. It highlights that while energy and air quality perspectives have gained attention, the health dimension remains underexplored, especially in sensitive environments like hospitals. For instance, Niu et al. (2022) [

111] demonstrated that window operation significantly impacts both energy consumption and airborne infection rates in a maternity hospital. This underscores the critical need to investigate windows not only from an energy standpoint but also from a functional and health-related perspective. In the context of windows behavior, most studies have focused on predictive modeling based on factor analysis. However, a quantitative, standardized approach remains lacking. The research objectives - whether targeting “window opening behavior” or “window status”—are often inconsistently defined, leading to confusion and limited comparability across studies.

Furthermore, studies rarely explore how technology-linked design can be adapted to cultural context, spatial orientation, or behavioral diversity. Integrating tools like artificial neural networks (ANN) can offer promising pathways to simulate real-time behavioral dynamics and inform algorithm-driven adaptive strategies. Similarly, linking thermal comfort with economic and sustainability perspectives requires greater attention to socio-demographic variables such as gender, age, and geographical climate zones. These aspects remain underrepresented in existing literature. In addition, current research tends to overlook

social-behavioral dynamics, which are crucial to understanding how building design, occupancy patterns, and user interaction influence indoor environmental quality [

112].

In summary, future research should adopt an interdisciplinary and context-sensitive approach, integrating technological innovations, AI applications, and social behavior modeling to address the knowledge gaps identified in

Table 4.

7. Conclusions:

Thermal comfort is not a new topic; however, it has been less considered in relation to occupant behavior and window configuration. This review aims to fill the gap with the following conclusion, drawn from a rigorous review of the previous literature.

Window operation behavior depends on an occupant’s activities, including opening, closing, duration, and frequency of use. It is influenced mainly by five factors: environmental, contextual, physiological, psychological, and socio-cultural factors.

In the window behavior, building thermal mass, type of ventilation using mixed-mode methods, and HVAC system has an additional impact on achieving thermal comfort, along with the energy performance of the building.

The use of parametric simulation in previous studies has demonstrated that electrochromic windows can yield energy savings ranging from 6.1 to 8.6%.

Smart technology used in window behavior has proven to save up to 20 % in cooling energy.

An automatic smart system is more effective in both visual and maintaining indoor thermal comfort. However, window behavior is strongly influenced by room floor height, occupant age, and activities.

The buildings, along with the window design strategies, impact the building’s energy performance. Integration of behavioral models in design strategies is crucial to enhance thermal comfort to achieve building sustainability, and it can provide a more comprehensive bioclimatic design performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S., Y.R and R.S. ; Methodology, B.S. and R.S.; Software, R.S.; Validation, B.S., H.B.R. and R.S.; Formal Analysis, B.S., Y.R. and R.S.; Investigation, B.S., Y.R., H.B.R. and R.S.; Resources, B.S. and R.S.; Data Curation, B.S., Y.R. and R.S.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, B.S., Y.R. and R.S.; Writing – Review and Editing, B.S., H.B.R. and R.S.; Visualization, B.S., Y.R., H.B.R. and R.S.; Supervision, B.S. and R.S.; Project Administration, B.S. and R.S., Funding Acquisition, B.S. and R.S.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Innovation Centre, Manmohan Technical University, Morang, Nepal, and by the Research, Development & Innovation (RDI), Kathmandu University, Dhulikhel, Nepal.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Department of Mechanical Engineering and the Department of Architecture, School of Engineering, Kathmandu University, Nepal.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahmad, M.W.; Mourshed, M.; Yuce, B.; Rezgui, Y. Computational Intelligence Techniques for HVAC Systems: A Review. Build Simul 2016, 9, 359–398.

- D’oca, S.; Hong, T.; Langevin, J. The Human Dimensions of Energy Use in Buildings: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2018, 81, 731–742.

- Földváry Ličina, V.; Cheung, T.; Zhang, H.; de Dear, R.; Parkinson, T.; Arens, E.; Chun, C.; Schiavon, S.; Luo, M.; Brager, G.; et al. Development of the ASHRAE Global Thermal Comfort Database II. Build Environ 2018, 142, 502–512. [CrossRef]

- 2020; 4. Franco IB; Chatterji T; Derbyshire E; Tracey J Science for Sustainable Societies, Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact, Towards Sustainability Science, Policy, Education and Practice; Springer, 2020;

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Meng, Q.; Wei, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wu, M.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lian, Y. Window Opening Behavior of Residential Buildings during the Transitional Season in China’s Xi’an. Complexity 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, B.W. The Philosophy behind EN15251: Indoor Environmental Criteria for Design and Calculation of Energy Performance of Buildings. Energy Build 2007, 39, 740–749. [CrossRef]

- Elghamry, R.; Hassan, H. Impact of Window Parameters on the Building Envelope on the Thermal Comfort, Energy Consumption and Cost and Environment. International Journal of Ventilation 2020, 19, 233–259. [CrossRef]

- Aldawoud, A. Windows Design for Maximum Cross-Ventilation in Buildings. Advances in Building Energy Research 2017, 11, 67–86.

- Asif, M.; Muneer, T.; Kubie, J. Sustainability Analysis of Window Frames. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology 2005, 26, 71–87. [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y. Thermal Performance of an Advanced Smart Fenestration Systems for Low-Energy Buildings. Appl Therm Eng 2024, 244. [CrossRef]

- Hemaida, A.; Ghosh, A.; Sundaram, S.; Mallick, T.K. Evaluation of Thermal Performance for a Smart Switchable Adaptive Polymer Dispersed Liquid Crystal (PDLC) Glazing. Solar Energy 2020, 195, 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Stavrakakis, G.M.; Zervas, P.L.; Sarimveis, H.; Markatos, N.C. Optimization of Window-Openings Design for Thermal Comfort in Naturally Ventilated Buildings. Appl Math Model 2012, 36, 193–211. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Deng, X. An Optimised Window Control Strategy for Naturally Ventilated Residential Buildings in Warm Climates. Sustain Cities Soc 2020, 57, 102118. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.A.; Wongpanyathaworn, K. Optimising Louver Location to Improve Indoor Thermal Comfort Based on Natural Ventilation. In Proceedings of the Procedia Engineering; Elsevier Ltd, 2012; Vol. 49, pp. 169–178.

- Elshafei, G.; Negm, A.; Bady, M.; Suzuki, M.; Ibrahim, M.G. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of the Impacts of Window Parameters on Indoor Natural Ventilation in a Residential Building. Energy Build 2017, 141, 321–332. [CrossRef]

- Allocca, C.; Chen, Q.; Glicksman, L.R. Design Analysis of Single-Sided Natural Ventilation. Energy Build 2003, 35, 785–795. [CrossRef]

- Borge-Diez, D.; Colmenar-Santos, A.; Pérez-Molina, C.; Castro-Gil, M. Passive Climatization Using a Cool Roof and Natural Ventilation for Internally Displaced Persons in Hot Climates: Case Study for Haiti. Build Environ 2013, 59, 116–126. [CrossRef]

- de Abreu-Harbich, L. V.; Chaves, V.L.A.; Brandstetter, M.C.G.O. Evaluation of Strategies That Improve the Thermal Comfort and Energy Saving of a Classroom of an Institutional Building in a Tropical Climate. Build Environ 2018, 135, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi Rizi, R.; Sangin, H.; Haghighatnejad Chobari, K.; Eltaweel, A.; Phipps, R. Optimising Daylight and Ventilation Performance: A Building Envelope Design Methodology. Buildings 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Heiselberg, P.; Perino, M. Short-Term Airing by Natural Ventilation - Implication on IAQ and Thermal Comfort. Indoor Air 2010, 20, 126–140. [CrossRef]

- Ogundiran, J.; Asadi, E.; Gameiro da Silva, M. A Systematic Review on the Use of AI for Energy Efficiency and Indoor Environmental Quality in Buildings. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16.

- Nicol, J.F.; Humphreys, M.A. Adaptive Thermal Comfort and Sustainable Thermal Standards for Buildings; 2002;

- Kim, A.; Wang, S.; Kim, J.E.; Reed, D. Indoor/Outdoor Environmental Parameters and Window-Opening Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Buildings 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Greenberg, S. Window Operation and Impacts on Building Energy Consumption. Energy Build 2015, 92, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Hawila, A.A.W.; Diallo, T.M.O.; Collignan, B. Occupants’ Window Opening Behavior in Office Buildings: A Review of Influencing Factors, Modeling Approaches and Model Verification. Build Environ 2023, 242.

- Koenigshberger OH; Ingersoll TG; Mayhew A; Szokolay SV Manual of Tropical Housing and Building: Climatic Design; 1984;

- Deosthali, V. Assessment of Impact of Urbanization on Climate: An Application of Bio-Climatic Index. Atmos Environ 1999, 33, 4125–4133.

- Auliciems, Andris.; Szokolay, S.V.. Thermal Comfort; PLEA in association with Dept. of Architecture, University of Queensland, 1997; ISBN 0867767294.

- Cooper I Comfort Theory and Practice: Barriers to the Conservation of Energy by Building Occupants. Appl Energy 1982, 11, 243–288.

- Winslow, C.-E.A.; Herrington, L.P.; Gagge, A.P. Physiological Reactions of the Human Body to Varying Environmental Temperatures. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 1937, 1, 1–22.

- Gagge AP; Stolwijk JA; Nishi Y Memoirs of the Faculty of Engineering, Hokkaido University. May 1972, pp. 21–36.

- Graveling RA; Morris LA; Graves RJ Working in Hot Conditions in Mining: A Literature Review.; 1988;

- Moran, D.S.; Shitzer, A.; Pandolf, K.B. A Physiological Strain Index to Evaluate Heat Stress; 1998; Vol. 275;.

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering; McGraw-Hill Inc.,US, 1972;

- De Dear Richard; Brager GS. Developing an Adaptive Model of Thermal Comfort and Preference. ASHRAE Trans 1988, 104, Part 1.

- Jendritzky, G.; de Dear, R.; Havenith, G. UTCI-Why Another Thermal Index? Int J Biometeorol 2012, 56, 421–428. [CrossRef]

- Havenith, G.; Fiala, D. Thermal Indices and Thermophysiological Modeling for Heat Stress. Compr Physiol 2016, 6, 255–302. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.F.; Vásquez, N.G.; Lamberts, R. A Review of Human Thermal Comfort in the Built Environment. Energy Build 2015, 105, 178–205.

- Fang, L.; Clausen, G.; Fanger, P. 0 Impact of Temperature and Humidity on Perception of Indoor Air Quality During Immediate and Longer Whole-Body Exposures. J AIVC 11795 Indoor Air 1998, 8, 276–284.

- Charles, K.E. Fanger’s Thermal Comfort and Draught Models; 2003;

- Berglund, L.G.; Cain, W.S. Perceived Air Quality and the Thermal Environment. 1989.

- Gunnarsen, L.; Fanger, P.O. Adaptation to Indoor Air Pollution. Environ Int 1992, 18, 43–54.

- ASHRAE. ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2004: Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. Supersedes ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-1992. Atlanta, GA: ASHRAE 2004.

- ASHRAE ADDENDA ANSI/ASHRAE Addendum d to ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2017 Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy.; 2020;

- Cain, W.; Berglund LG; Duffee RA; Turk A Ventilation and Odor Control: Prospects for Energy Efficiency. Final Report of Phase I; 1979;

- Simons, B.; Koranteng, C.; Adinyira, E.; Ayarkwa, J. An Assessment of Thermal Comfort in Multi Storey Office Buildings in Ghana. Journal of Building Construction and Planning Research 2014, 02, 30–38. [CrossRef]

- Hoes, P.; Hensen, J.L.M.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; de Vries, B.; Bourgeois, D. User Behavior in Whole Building Simulation. Energy Build 2009, 41, 295–302. [CrossRef]

- Fabi, V.; Andersen, R.V.; Corgnati, S.; Olesen, B.W. Occupants’ Window Opening Behaviour: A Literature Review of Factors Influencing Occupant Behaviour and Models. Build Environ 2012, 58, 188–198. [CrossRef]

- Torabi Moghadam, S.; Soncini, F.; Fabi, V.; Corgnati, S. Simulating Window Behaviour of Passive and Active Users. In Proceedings of the Energy Procedia; Elsevier Ltd, November 1 2015; Vol. 78, pp. 621–626.

- Al-Waheed Hawila, A.; Diallo, T.M.; Collignan, B. Occupants’ Window Opening Behavior in Office Building: A Review 1 of Influencing Factors, Modeling Approaches and Verification of 2 Literature Models Occupants’ Window Opening Behavior in Office Building: A Review 9 of Influencing Factors, Modeling Approaches and Verification Of; 2023;

- Foruzanmehr, A. People’s Perception of the Loggia: A Vernacular Passive Cooling System in Iranian Architecture. Sustain Cities Soc 2015, 19, 61–67. [CrossRef]

- Sorgato, M.J.; Melo, A.P.; Lamberts, R. The Effect of Window Opening Ventilation Control on Residential Building Energy Consumption. Energy Build 2016, 133, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, E.H.; Lofrano, F.C.; Kurokawa, F.A.; Prado, R.T.A.; Leite, B.C.C. Decision-Making Process for Thermal Comfort and Energy Efficiency Optimization Coupling Smart-Window and Natural Ventilation in the Warm and Hot Climates. Energy Build 2022, 266. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Song, S.Y. Energy Efficiency, Visual Comfort, and Thermal Comfort of Suspended Particle Device Smart Windows in a Residential Building: A Full-Scale Experimental Study. Energy Build 2023, 298. [CrossRef]

- Fathi, S.; Kavoosi, A. Effect of Electrochromic Windows on Energy Consumption of High-Rise Office Buildings in Different Climate Regions of Iran. Solar Energy 2021, 223, 132–149. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Yu, P.; Gao, J.; Ma, C.; Xu, J.; Duan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Miao, Z. An Energy-Efficient and Low-Driving-Voltage Flexible Smart Window Enhanced by POSS and CsxWO3. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2023, 250. [CrossRef]

- Nahmens, I.; Joukar, A.; Cantrell, R. Impact of Low-Income Occupant Behavior on Energy Consumption in Hot-Humid Climates. Journal of Architectural Engineering 2015, 21. [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, G. Ventilation: A Behavioural Approach. ENERGY RESEARCH 1977, I, 289–298.

- Dick, J.; Thomas, D. Ventilation Research in Occupied Houses. Journal of the Institution of Heating and Ventilating Engineers 1951, 306–326.

- Wallace, L.A.; Emmerich, S.J.; Howard-Reed, C. Continuous Measurements of Air Change Rates in an Occupied House for 1 Year: The Effect of Temperature, Wind, Fans, and Windows. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 2002, 12, 296–306. [CrossRef]

- Herkel, S.; Knapp, U.; Pfafferott, J. Towards a Model of User Behaviour Regarding the Manual Control of Windows in Office Buildings. Build Environ 2008, 43, 588–600. [CrossRef]

- Yun, G.Y.; Steemers, K. Time-Dependent Occupant Behaviour Models of Window Control in Summer. Build Environ 2008, 43, 1471–1482. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Cao, J.; Feng, F.; Li, Z. The Role of Occupant Behavior in Low Carbon Oriented Residential Community Planning: A Case Study in Qingdao. Energy Build 2017, 139, 385–394. [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Wang, S.; Sun, S. Impacts of Technology-Guided Occupant Behavior on Air-Conditioning System Control and Building Energy Use. Build Simul 2021, 14, 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Calautit, J.; Tien, P.W.; Wei, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Xia, L. An Occupant-Centric Control Strategy for Indoor Thermal Comfort, Air Quality and Energy Management. Energy Build 2023, 285. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, C.S. Quantification of Occupant Response to Influencing Factors of Window Adjustment Behavior Using Explainable AI. Energy Build 2023, 296. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, K.H.; Scolaro, T.P.; Ghisi, E. Enhancing Building Sustainability: Integrating User Behaviour and Solar Orientation in the Thermal Performance of Houses. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Paone, A.; Bacher, J.P. The Impact of Building Occupant Behavior on Energy Efficiency and Methods to Influence It: A Review of the State of the Art. Energies (Basel) 2018, 11.

- Srisamranrungruang, T.; Hiyama, K. Application of Artificial Neural Network for Natural Ventilation Schemes to Control Operable Windows. Heliyon 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.; Norford, L.; Wetter, M.; Malkawi, A. Development of Window Scheduler Algorithm Exploiting Natural Ventilation and Thermal Mass for Building Energy Simulation and Smart Home Controls. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 82. [CrossRef]

- El Khattabi, S.; Fraisse, G.; Leconte, A.; Rouchier, S. Impact of Occupant Behavior on Optimal Multi-Objective Solutions for the Design of Low-Energy Buildings. Energy Build 2024, 317. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.R.; Dong, B. Prediction of Window Opening Behavior and Its Impact on HVAC Energy Consumption at a Residential Dormitory Using Deep Neural Network. Energy Build 2023, 296. [CrossRef]

- Naspi, F.; Arnesano, M.; Stazi, F.; D’Orazio, M.; Revel, G.M. Measuring Occupants’ Behaviour for Buildings’ Dynamic Cosimulation. J Sens 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Roccotelli, M.; Rinaldi, A.; Fanti, M.P.; Iannone, F. Article Building Energy Management for Passive Cooling Based on Stochastic Occupants Behavior Evaluation. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Tien, P.W.; Wei, S.; Calautit, J.K.; Darkwa, J.; Wood, C. Real-Time Monitoring of Occupancy Activities and Window Opening within Buildings Using an Integrated Deep Learning-Based Approach for Reducing Energy Demand. Appl Energy 2022, 308. [CrossRef]