1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

The building sector is a significant contributor to global climate change and energy consumption, accounting for approximately 40% of worldwide energy usage and 36% of CO

2 emissions [

1]. In China, this challenge is particularly acute, with buildings responsible for nearly 50% of national carbon emissions, a figure projected to peak at 5,139 million tons of CO

2 by 2030, representing a 4.4% increase from 2020 levels [

2].

Educational buildings account for a substantial proportion of energy use. In China, primary and secondary schools occupy over 840 million square meters, while higher education institutions encompass an additional 929 million square meters [

3]. The Guangzhou metropolitan area alone hosts more than 3,200 educational facilities, including 16 international schools, serving a population of over 2 million students [

4]. However, only approximately 2% of new educational buildings in China have attained green building certification [

5], highlighting the pressing need for more energy-efficient design approaches.

School buildings in hot-humid climates, such as those in southern China, face unique energy management and thermal comfort challenges. Highly variable energy demands, influenced by factors like class schedules, seasonal breaks, and diverse space utilization, necessitate critical energy optimization considerations. For instance, Tianjin school buildings exhibit the lowest public building energy consumption at 24.53 kWh/ (m

2·a), yet further optimization is possible through enhanced design strategies [

6]. The hot-humid climate, characterized by high temperatures and elevated humidity, exacerbates cooling energy demands, driving higher energy consumption.

The present study proposes a multi-objective optimization framework for the design of windows in school buildings situated in hot-humid climates. The framework seeks to balance energy efficiency and thermal comfort through the integration of evolutionary algorithms and rule-based decision-making. The goal is to identify optimal window configurations that minimize energy consumption while enhancing occupant thermal comfort.

1.2. Literature Review and Research Gap

Designing school buildings in hot-humid climates poses distinct challenges in achieving energy efficiency and thermal comfort. While many studies have optimized building performance, few have employed multi-objective optimization, particularly for educational buildings in these climates. These studies often overlook the simultaneous consideration of key design parameters like window-to-wall ratio (WWR) and shading coefficient (SC), crucial for optimizing energy use and occupant comfort [

7]. Despite extensive research on individual design factors, comprehensive optimization frameworks integrating window design, shading, and building orientation are rare [

8,

9].

Figure 1.

Keyword co-occurrence network multi-objective optimization. It presents a keyword co-occurrence network, demonstrating the growing interest in adaptive thermal comfort and genetic algorithms, with increasing focus on school buildings and indoor air quality.

Figure 1.

Keyword co-occurrence network multi-objective optimization. It presents a keyword co-occurrence network, demonstrating the growing interest in adaptive thermal comfort and genetic algorithms, with increasing focus on school buildings and indoor air quality.

Hwang et al. [

10] investigated the application of phase change materials (PCMs) on school rooftops in Taiwan, demonstrating a decrease in indoor temperatures. Their study, however, was limited to roofs and did not consider integrating PCMs with window designs, which are vital for comprehensive building performance [

11,

13]. Similarly, Mba et al. [

12] assessed the effect of building orientation on natural ventilation in Nigerian schools, achieving notable enhancements in ventilation efficiency. Nonetheless, their research excluded mechanical cooling systems, essential for hot-humid climates [

7,

13]. These omissions underscore the necessity for integrated strategies that combine both passive and active cooling techniques.

Yi et al. [

14] examined cooling strategies for classrooms in Guangzhou, achieving a 16.6% reduction in energy consumption. Notably, their study lacked the application of optimization algorithms, such as evolutionary algorithms, which could systematically explore design variables. This highlights the need for multi-objective optimization to enhance window configurations for both energy efficiency and thermal comfort [

14,

15]. Similarly, Sorooshnia et al. [

15] proposed a kinetic shading system for residential buildings but overlooked the varying occupancy patterns of educational buildings [

7,

15].

The thermal comfort of occupants in educational facilities has been extensively examined. A study by Lala et al. [

16] found that 95.1% of primary school students in India reported satisfaction with thermal conditions, even in high heat-risk environments. However, this work did not propose specific interventions to optimize comfort, underscoring the need for targeted design strategies in educational buildings [

16,

17]. Conversely, Liu et al. [

17] optimized the window-to-wall ratio (WWR) for residential buildings in China’s hot-summer and cold-winter climate, suggesting an optimal range of 20-30% to minimize energy consumption. Yet, this investigation did not integrate other critical window parameters, such as shading geometry and glazing properties, which are crucial considerations for school buildings [

17].

The application of multi-objective optimization in the design of school buildings within hot-humid climates remains underexplored. While evolutionary algorithms, such as NSGA-II, have proven successful in optimizing competing objectives in various building types, their utilization in the context of window design for schools has not been thoroughly investigated. Previous studies have incorporated occupant behavior into multi-objective optimization, demonstrating the potential to reduce energy consumption while maintaining thermal comfort [

18]. However, these methods have yet to be applied to school buildings, which exhibit distinct occupancy patterns [

13].

Li et al. [

19] optimized HVAC systems in commercial buildings, but neglected to consider passive design elements such as window configurations, which are crucial for school buildings with substantial cooling requirements [

13,

19]. Song et al. [

20] compared radiant cooling systems with conventional systems, demonstrating that personalized cooling could reduce energy consumption while maintaining comfort. However, this approach did not address the practical implementation in educational buildings, which face budgetary constraints [

13,

20].

While substantial progress has been made in building design optimization, research has predominantly focused on individual parameters, often overlooking their interdependencies. Additionally, the majority of studies emphasize residential or office buildings, failing to account for the distinct operational requirements of educational facilities. This study aims to bridge these gaps by creating a multi-objective optimization framework tailored to window design in school buildings situated in hot-humid climates.

1.3. Research Objectives and Significance

Optimizing window design in school buildings located in hot-humid climates remains a significant challenge, despite advancements in building energy optimization and thermal comfort research. Previous studies have often focused on individual parameters, such as window-to-wall ratio (WWR), while overlooking the complex interactions with other factors like shading, glazing, and thermal mass [

21,

22]. Furthermore, the majority of optimization efforts have been directed towards residential or office buildings, neglecting the unique operational patterns and comfort requirements of educational facilities [

23,

24]. These gaps highlight the need for comprehensive, multi-objective optimization approaches to address the design of school buildings in hot-humid climates.

This study aims to develop a comprehensive multi-objective optimization framework tailored specifically for window design in school buildings situated in hot-humid climates. The key objectives of this research are:

To develop an integrated parametric modeling and optimization workflow, combining Rhino/Grasshopper with the NSGA-II algorithm to optimize window configurations for school buildings.

To identify optimal window configurations that balance energy efficiency and thermal comfort, particularly for schools in Guangzhou’s hot-humid climate, while considering crucial factors such as shading, glazing, and WWR.

To analyze the trade-offs between energy efficiency and thermal comfort, offering actionable design insights for architects and engineers.

To validate the optimization framework through a case study of a representative school building in Guangzhou, China, demonstrating the framework’s real-world applicability.

This study aims to optimize school building design in hot-humid climates, offering valuable guidance for architects and engineers seeking to balance energy efficiency and thermal comfort. By focusing on the most impactful window design parameters, the research provides Pareto-optimal solutions that achieve the best trade-offs between energy use and occupant comfort [

25,

26].

2. Methodology

This study comprises four principal phases. Leveraging prior climate analysis, the initial phase entails the development of a parametric modeling framework and performance simulation. The second phase applies multi-objective optimization to derive Pareto-optimal solutions. The third phase employs sensitivity analysis, elucidating the influence and interrelationships of diverse physical parameters on energy use and thermal comfort in school classrooms.The forth phase use machine learning techniques for model verification

Figure 2.

Research Framework for Multi-objective Optimization in School Building Design. The figure illustrates the step-by-step process used in this study, starting from identifying performance metrics and design variables, followed by sensitivity analysis, multi-objective optimization, and machine learning techniques. This framework integrates energy consumption, thermal comfort, and optimization strategies to generate optimal window configurations for school buildings in hot-humid climates.

Figure 2.

Research Framework for Multi-objective Optimization in School Building Design. The figure illustrates the step-by-step process used in this study, starting from identifying performance metrics and design variables, followed by sensitivity analysis, multi-objective optimization, and machine learning techniques. This framework integrates energy consumption, thermal comfort, and optimization strategies to generate optimal window configurations for school buildings in hot-humid climates.

2.1. Climate Background

Guangzhou, situated in southern China, exhibits a characteristic hot-humid climate with consistently high temperatures and elevated humidity levels throughout the year. The average annual temperature ranges from 16°C in winter to 35°C in summer, with peak values recorded from May to September. The region experiences high relative humidity, frequently exceeding 80% during the summer, which substantially impacts the cooling energy demands of buildings [

27].

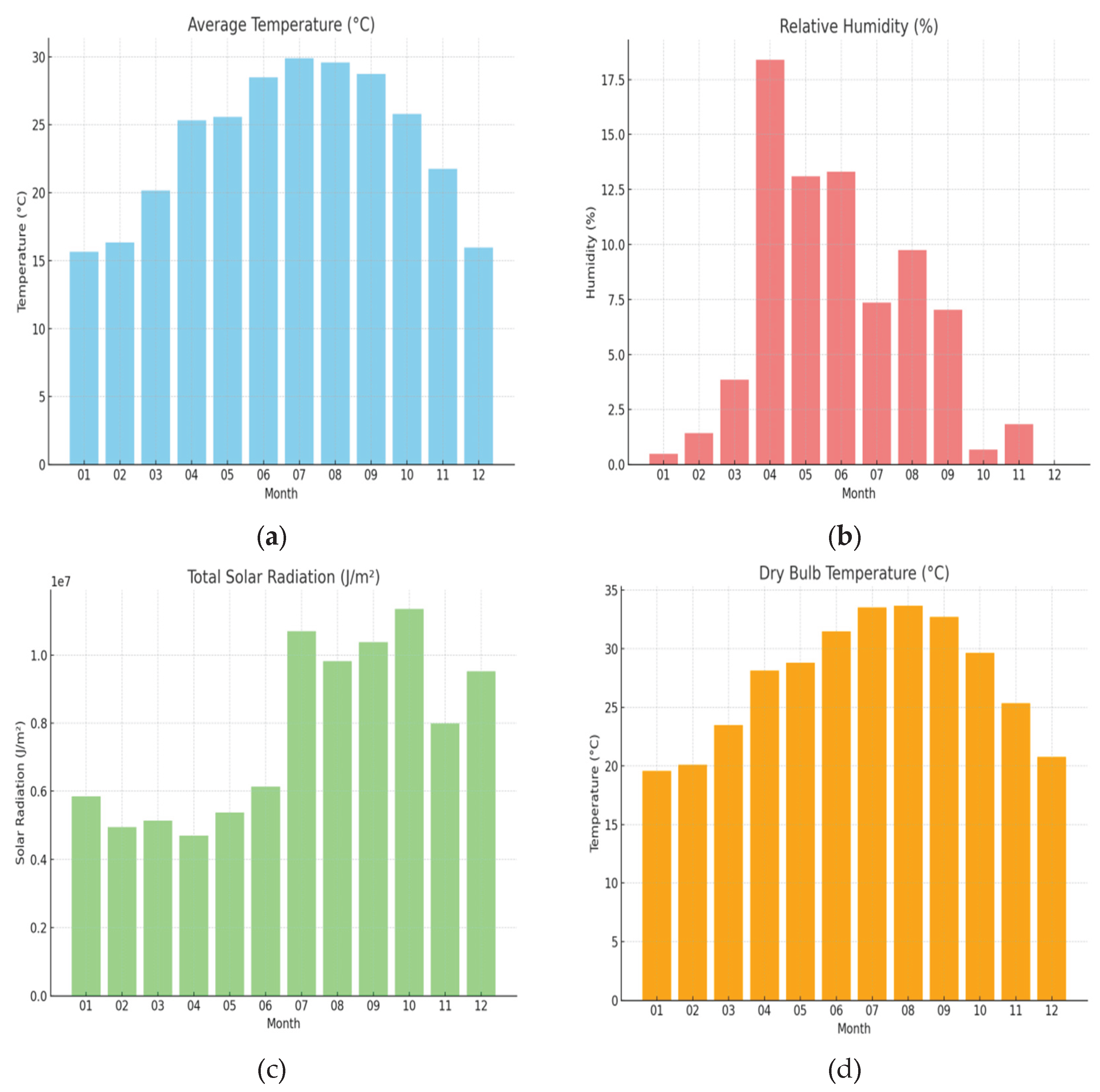

Figure 3 (a) illustrates the monthly average temperature ranging from 16°C in winter to 35°C in summer, highlighting significant seasonal variations that affect building cooling demands.

Figure 3 (b) depicts the relative humidity trend, exceeding 80% in summer, underscoring the difficulty of maintaining comfortable indoor environments without high energy consumption. These climatic factors are pivotal in shaping thermal comfort and energy use patterns in this region’s buildings.

Guangzhou’s hot-humid climate significantly impacts building energy use and thermal comfort. Cooling demands are heavily influenced by solar radiation, shading, and thermal mass. Excessive heat gain through windows, exacerbated by insufficient shading, leads to increased energy consumption, underscoring the critical role of window design in enhancing energy efficiency and occupant comfort [

28].

The choice of window design, particularly the Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR), shading devices, and glazing properties, is crucial for managing the thermal performance of buildings in hot-humid climates. Well-designed windows can mitigate solar heat gain during summer while ensuring sufficient daylighting. These considerations are especially important for school buildings, which often experience high internal heat loads due to occupancy, lighting, and equipment use. Therefore, the optimization of window parameters is essential for achieving energy efficiency and thermal comfort in schools situated in hot-humid regions.

The present study investigates energy-efficient window design strategies to address the substantial cooling demands imposed by Guangzhou’s climate. Employing a multi-objective optimization approach, this work develops a framework for optimizing window design in school buildings, tailored to the region’s climatic characteristics, as depicted in

Figure 3 (c), which illustrates the relationship between total solar radiation and cooling load.

2.2. Performance Simulation Methods

This study leverages EnergyPlus and Honeybee models to comprehensively evaluate building energy performance and thermal comfort. The models assess the impact of key design parameters, including Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR), Shading Coefficient (SC), a Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC), Shading Angle and Shading Width, on Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR). Energy Use Intensity (EUI), calculated as the total annual energy consumption per unit floor area, serves as the primary metric for assessing energy consumption, as expressed by the equation:

where:

- -

is the total energy consumed by the building in kilowatt-hours per year (kWh/year).

- -

is the total floor area of the building in square meters ().

The energy use intensity (EUI) is a widely adopted metric for evaluating the energy efficiency of buildings. It provides a standardized measure that enables the comparative assessment of energy performance across diverse building types and configurations [

29,

30]. This metric plays a pivotal role in identifying energy inefficiencies and guiding optimization efforts in building design, particularly with respect to energy consumption per unit of floor area.

The Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) is used to assess thermal comfort by calculating the percentage of time indoor conditions align with acceptable thermal comfort standards. The TCTR equation is:

where:

- -

represents the comfort index at time t, indicating whether the indoor environment meets thermal comfort standards. If = 1, the indoor environment meets the comfort standards, while if = 0, it does not.

- -

is the total time period being considered, typically one year.

is the thermal comfort time ration, representing the percentage of time that the indoor environment remains within thermal comfort conditions.

TCTR is frequently employed in building simulations to evaluate indoor comfort, especially in educational environments where occupant comfort is paramount [

31,

32]. It is extensively used in research examining the impact of environmental factors like temperature and humidity on occupant comfort over time. The TCTR formula ensures indoor climates remain within acceptable limits, crucial for optimizing building designs in hot-humid climates.

The study employs simulation tools to identify key parameters, thereby streamlining the optimization process. This method enables practical assessment and expedites the optimization of window configurations, offering actionable insights for architects and engineers aiming to enhance energy efficiency and thermal comfort in school buildings situated in hot-humid climates.

2.3. Multi-Objective Optimization

This study utilizes the NSGA-II algorithm, combined with Grasshopper, to optimize window configurations in school buildings. The multi-objective optimization seeks to minimize Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and maximize the Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR), both critical indicators of sustainable building design. The objective functions for EUI and TCTR are defined as follows:

where:

- -

Energy Use Intensity function (EUI)

- -

Thermal Comfort time percentage function (TC)

The inherent conflict between energy efficiency and thermal comfort necessitates the use of a robust multi-objective optimization approach. The well-established NSGA-II algorithm, a genetic algorithm for multi-objective optimization, is employed to efficiently generate a set of Pareto-optimal solutions. This enables a balanced assessment of the competing objectives of energy efficiency and occupant comfort [

33]. The application of NSGA-II in building design optimization has been extensively documented, particularly in scenarios where objectives such as energy use and occupant well-being require careful trade-offs [

34].

In addition to the optimization process, the crowding distance metric is used to maintain diversity in the Pareto-optimal solutions. The crowding distance,

, of a solution

is calculated by evaluating the density of neighboring solutions in the objective space. The formula for crowding distance is given by:

where:

- -

is the crowding distance of the -th solution,

- -

and are the objective values of the neighboring solutions on the -th objective,

- -

and are the maximum and minimum values of the -th objective.

This metric preserves a diverse set of Pareto-optimal solutions, preventing the optimization process from narrowly focusing on improving individual objectives and instead maximizing the spread of solutions across the Pareto front.

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis and Machine Learning Models

This study employs Sobol sensitivity analysis and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to evaluate the influence of key design parameters on building Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR). Sobol sensitivity analysis, a prominent global sensitivity analysis technique, partitions the variance in model outputs to elucidate how input parameters affect the system’s behavior. This methodology has been widely adopted in building energy simulations to pinpoint critical design variables that significantly impact building performance [

35].

The Sobol sensitivity analysis was conducted using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS), a robust statistical method that ensures efficient and representative sampling across the input space. LHS divides each parameter range into intervals and samples one point from each, thereby maintaining the accuracy of the analysis while capturing the variability of input parameters [

36].

The Sobol sensitivity indices offer a quantitative assessment of the contribution of each input parameter to the overall variance in the model output. The first-order sensitivity index

captures the direct effect of a given parameter, while the total-order sensitivity index

accounts for both direct effects and interactions between parameters [

37]. Mathematically, these indices are defined as: Equation (5) This formulation enables a comprehensive evaluation of parameter importance and the identification of the key drivers of model output uncertainty.

where:

- -

is the conditional expectation of Y given the input parameter ,

- -

is the variance of the output Y,

- -

represents all input parameters except

The identified indices serve as crucial tools in determining the most impactful parameters for both Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR), thereby guiding the optimization process to prioritize the variables with the greatest influence on building performance.

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is a probabilistic machine learning technique employed to approximate simulation results, thereby enhancing computational efficiency [

38]. GPR provides a non-linear approximation of complex simulation models, enabling faster predictions with an associated measure of uncertainty. This makes GPR suitable for optimization problems where extensive simulations are computationally expensive. By utilizing fewer simulations, GPR reduces the computational burden during the optimization process, facilitating more efficient identification of optimal window configurations.

This study employs Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to minimize the number of simulations necessary for optimization, thereby expediting the process and enhancing its efficiency [

39]. By integrating Sobol sensitivity analysis with GPR, it creates a robust framework for optimizing window designs in school buildings situated in hot-humid climates. Concentrating on the key parameters identified through sensitivity analysis allows for a more precise optimization that balances energy efficiency and thermal comfort.

3. Results

3.1. Model Simulation

3.1.1. Simulation

This study assesses the Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) of school buildings in hot-humid climates, emphasizing optimal window configurations. Building morphology and window placement critically influence thermal comfort and energy consumption [

40,

41]. A digital model of a representative school building in Guangzhou, measuring 120 by 80 meters and centered around a courtyard, was constructed. Classrooms are predominantly south-facing to enhance natural lighting and ventilation [

42].

Figure 4.

3D Model of the Representative School Building Used for Simulation. This 3D model represents a typical school building in Guangzhou, designed to evaluate energy consumption and thermal comfort. The building layout is based on typical school buildings with a central courtyard, where classrooms are oriented south for optimal natural lighting and ventilation.

Figure 4.

3D Model of the Representative School Building Used for Simulation. This 3D model represents a typical school building in Guangzhou, designed to evaluate energy consumption and thermal comfort. The building layout is based on typical school buildings with a central courtyard, where classrooms are oriented south for optimal natural lighting and ventilation.

This simulation examines six crucial window parameters—Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR), Shading Coefficient (SC), Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC), Heat Transfer Coefficient (K), Shading Width, and Shading Angle—due to their direct impact on energy consumption and comfort. These parameters significantly affect both energy use and the indoor thermal environment [

43,

44]. The study employs these factors to develop configurations aimed at optimizing the Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) metrics.

Energy Use Intensity (EUI) quantifies a building’s annual energy consumption per unit of floor area, while Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) evaluates the extent to which indoor conditions meet comfort standards [

45]. These performance metrics guide the optimization framework, enabling the identification of window designs that minimize energy use while maximizing thermal comfort.

The present study streamlines the simulation process by omitting minor design elements and concentrating on the core parameters that exert the most significant influence on building performance. This approach enables more practical evaluation and accelerated optimization, yielding actionable insights for window design in school facilities.

3.1.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Window Parameter Settings

The study examined the following primary window design parameters: Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR), Shading Coefficient (SC), Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC), Heat Transfer Coefficient (K), Shading Width, and Shading Angle. These variables were selected due to their significant influence on energy use and thermal comfort, as well as their relevance to building energy efficiency standards and the physical attributes of typical school buildings in Guangzhou.

Figure 5.

Window Design Parameters and Their Impact on Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort. This figure illustrates the window design parameters, their corresponding ranges, and their impacts on building energy efficiency and thermal comfort. The parameters such as WWR, SC, and SHGC are optimized to balance the energy consumption and comfort within school buildings in hot-humid climates.

Figure 5.

Window Design Parameters and Their Impact on Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort. This figure illustrates the window design parameters, their corresponding ranges, and their impacts on building energy efficiency and thermal comfort. The parameters such as WWR, SC, and SHGC are optimized to balance the energy consumption and comfort within school buildings in hot-humid climates.

WWR (0.1 to 0.5) governs the amount of daylight, ventilation, and heat transfer within the space, playing a pivotal role in minimizing energy consumption while ensuring adequate indoor lighting [

46].

SC (0.2 to 0.8) defines the fraction of solar heat gain transmitted through shading devices, thus reducing cooling loads by limiting the solar radiation entering the building [

47].

SHGC (0.1 to 0.4) measures the proportion of solar radiation admitted through the window as heat, which influences cooling demand and internal temperature, thereby impacting both energy efficiency and thermal comfort [

48].

K (1.0 to 2.5 W/ (m

2·K)) characterizes the thermal insulation properties of the window system. A lower K value enhances energy efficiency by reducing heat transfer [

49].

Shading Width (0.3 to 2.0 m) measures the horizontal projection length of external shading devices, which is essential for controlling solar gain and optimizing daylight availability [

50].

Shading Angle (0° to 90°) adjusts the angle of shading devices to optimize solar protection throughout the year, based on their seasonal effectiveness in blocking solar radiation [

51].

Table 1.

Window Design Parameters: Physical Meaning, Design Impact, and References.

Table 1.

Window Design Parameters: Physical Meaning, Design Impact, and References.

| Parameter |

Physical Meaning |

Design Impact |

Reference |

| Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) |

Ratio of window area to total wall area. |

Affects daylight, views, ventilation, and heat transfer. |

Sharma et al., 2022 [52]; Wang et al. , 2022 [53] |

| Shading Coefficient (SC) |

Fraction of solar heat gain transmitted through shading device. |

Controls solar gain, reduces cooling loads, enhances shading efficiency. |

Seyedzadeh et al., 2018 [54] |

| Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) |

Fraction of solar radiation admitted through window as heat. |

Influences cooling energy demand, impacts indoor temperature. |

Kalmár, F, 2020 [55]; Alhuwayil et al., 2019 [56] |

| Heat Transfer Coefficient (K) |

Measure of total window system’s heat transmission performance. |

Affects building energy efficiency and thermal insulation. |

Alhuwayil et al., 2018 [56] |

| Shading Width |

Horizontal projection length of the external shading device. |

Provides sun protection, modifies daylight and solar heat gain. |

Tan et al., 2024 [57] |

| Shading Angle |

Angle between the shading device and the horizontal plane. |

Optimizes sun protection seasonally, impacts view and daylight. |

Mazzetto et al., 2025 [58] |

The optimization framework was meticulously designed to navigate the trade-offs between energy efficiency and thermal comfort within the context of conventional school buildings situated in hot-humid environments. The selected parameters facilitated the effective exploration of this balance within the inherent constraints of such building typologies.

3.1.3. Constraints

The optimization process incorporated a series of constraints to ensure the technical feasibility and practical applicability of the generated solutions. These constraints were formulated based on national and local building codes, design standards, and practical experiences from the construction of educational facilities in Guangzhou.

The multi-objective optimization was subjected to the following constraints:

This is example 2 of an equation:

Among these, WWR is the window-to-wall ratio, SC is the shading coefficient, K is the thermal conductivity coefficient, SHGC is the solar heat gain coefficient, and TC is the annual thermal comfort time percentage.

Constraints were directly integrated into the optimization process using Grasshopper/Wallacei alongside the EnergyPlus simulation platform, ensuring the evolutionary algorithm generated only feasible solutions. These constraints were vital in balancing technical specifications with practical application, ensuring designs met Guangzhou’s climatic demands and adhered to relevant building standards.

Table 2.

Constraints.

| Constraint Name |

Value Range/Requirement |

Explanation |

Reference |

| Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) |

0.10–0.50 |

Ensures compliance with national and local building codes for educational buildings. |

GB 50189-2015 [59];Chiesa et al., 2019 [60] |

| Shading Coefficient (SC) |

0.20–0.80 |

Range covers typical external shading devices suitable for hot-humid climates. |

Chandrasekaran, 2022[61]; GB 50033-2013 [62] |

| Heat Transfer Coefficient (K) |

1.0–2.5 W/ (m2·K) |

Follows requirements of the “Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings.” |

GB 50189-2015 [59];Enteria et al., 2022 [63] |

| Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) |

0.10–0.40 |

Matches glazing options recommended for minimizing cooling loads in subtropical schools. |

Rajkumar, 2020 [64]; Sorooshnia et al., 2019 [65] |

| Shading Width |

0.3–2.0 m |

Conforms to feasible engineering practice and construction guidelines for sun shading elements. |

Khalaf et al., 2019 [66]; GB 50096-2011 [67] |

| Shading Angle |

0°–90° |

Reflects adjustable range for horizontal external shading based on climate-responsive design principles. |

da Silvaet al., 2023 [65]; GB 50033-2013 [62] |

| Thermal Comfort (TC) |

≥ 50% |

Ensures compliance with recommended standards for indoor environmental quality in classrooms. |

GB/T 50785-2012 [68]; Yang et al., 2018 [69] |

| Constructability |

Must use standard materials/processes |

Requires all window and shading systems to be easily construction and maintainable in local context. |

GB 50666-2011 [70]; Enteria et al., 2019 [63] |

3.2. Simulation Results Verification and Case Analysis

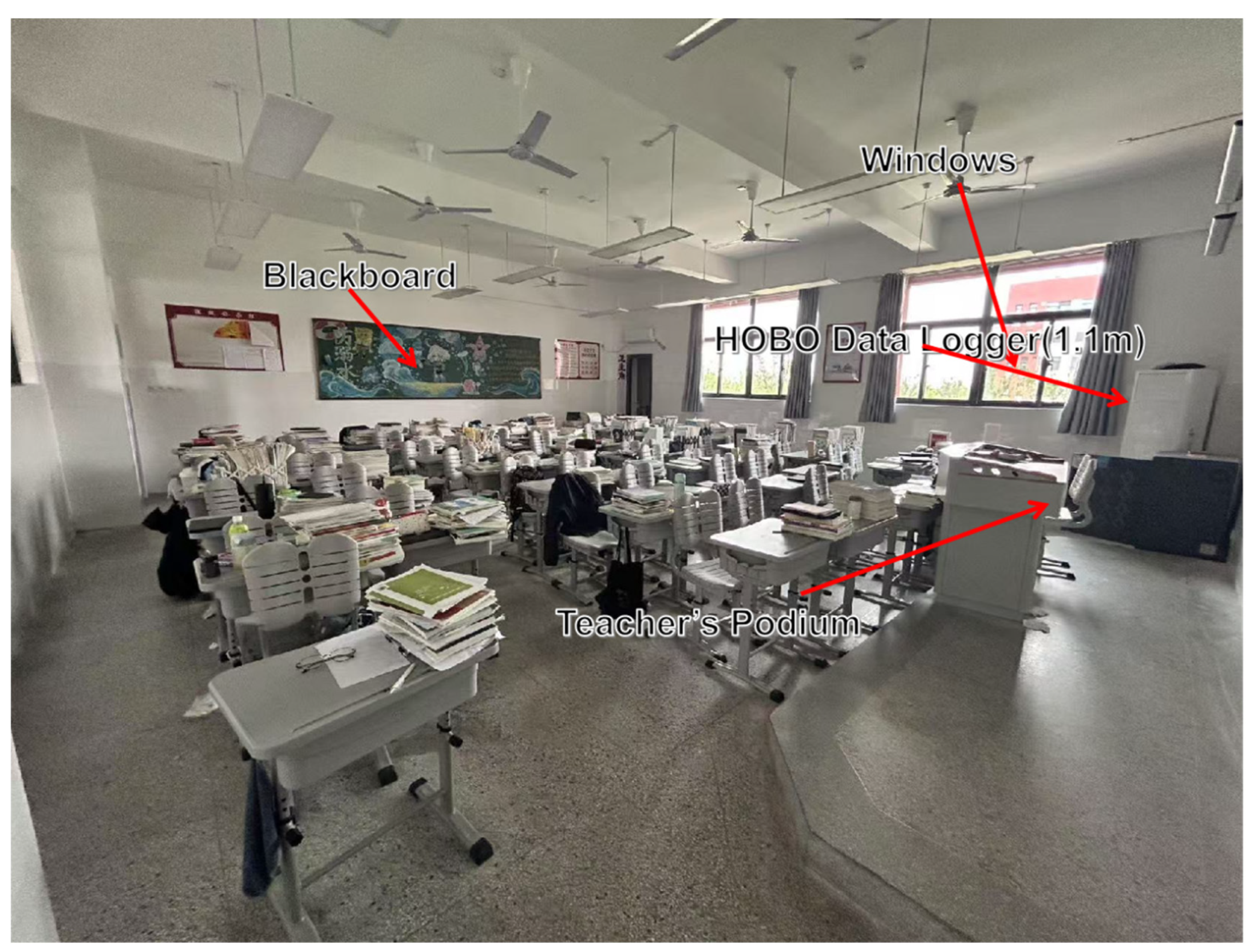

To validate the simulation results from the multi-objective optimization framework, a case study was conducted on a representative school building in Guangzhou’s Huadu District. Indoor environmental parameters, such as temperature and relative humidity, were measured and compared with the simulation data. Measurements were taken over typical summer and winter weeks using a HOBO U12 Data Logger, placed 1.1 meters above the floor, with recordings every 5 minutes. Meteorological data from the China Meteorological Administration’s typical meteorological year (TMY) dataset served as input for the simulation model.

Table 3.

Measurement Equipment Information.

Table 3.

Measurement Equipment Information.

| Parameter |

Instrument |

Model |

Measurement Range |

Accuracy |

Placement |

Sampling Interval |

| Air Temperature |

HOBO Data Logger |

U12013 |

-20°C to 70°C |

±0.35°C (0–50°C) |

Near window, 1.1m above floor |

Every 5 minutes |

| Relative Humidity |

HOBO Data Logger |

U12013 |

5%–95% RH |

±2.5% (10–90% RH typical) |

Near window, 1.1m above floor |

Every 5 minutes |

| Outdoor Climate Data |

China Meteorological Admin |

TMY dataset |

Regional typical values |

— |

Local weather station |

Hourly |

Figure 6.

Monitored Classroom and Sensor Deployment Layout. This figure highlights the placement of the HOBO U12 Data Logger near the windows, providing context for the data collection process used to validate the simulation results.

Figure 6.

Monitored Classroom and Sensor Deployment Layout. This figure highlights the placement of the HOBO U12 Data Logger near the windows, providing context for the data collection process used to validate the simulation results.

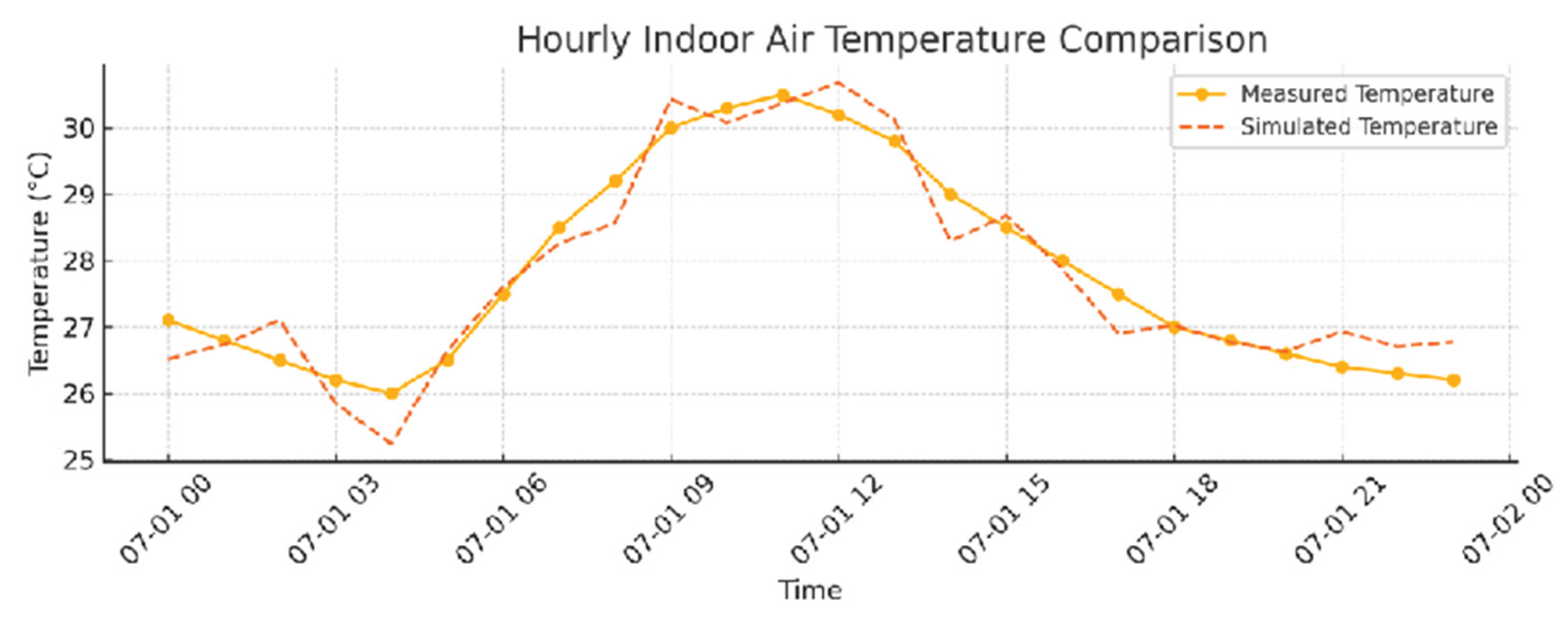

Figure 7.

Hourly Indoor Air Temperature Comparison for a Typical Hot Season Day. This graph compares the simulated and actual measured hourly temperature variations in the classroom during a typical hot season day. The simulation closely matches the observed temperature trends, with minor discrepancies during peak afternoon hours.

Figure 7.

Hourly Indoor Air Temperature Comparison for a Typical Hot Season Day. This graph compares the simulated and actual measured hourly temperature variations in the classroom during a typical hot season day. The simulation closely matches the observed temperature trends, with minor discrepancies during peak afternoon hours.

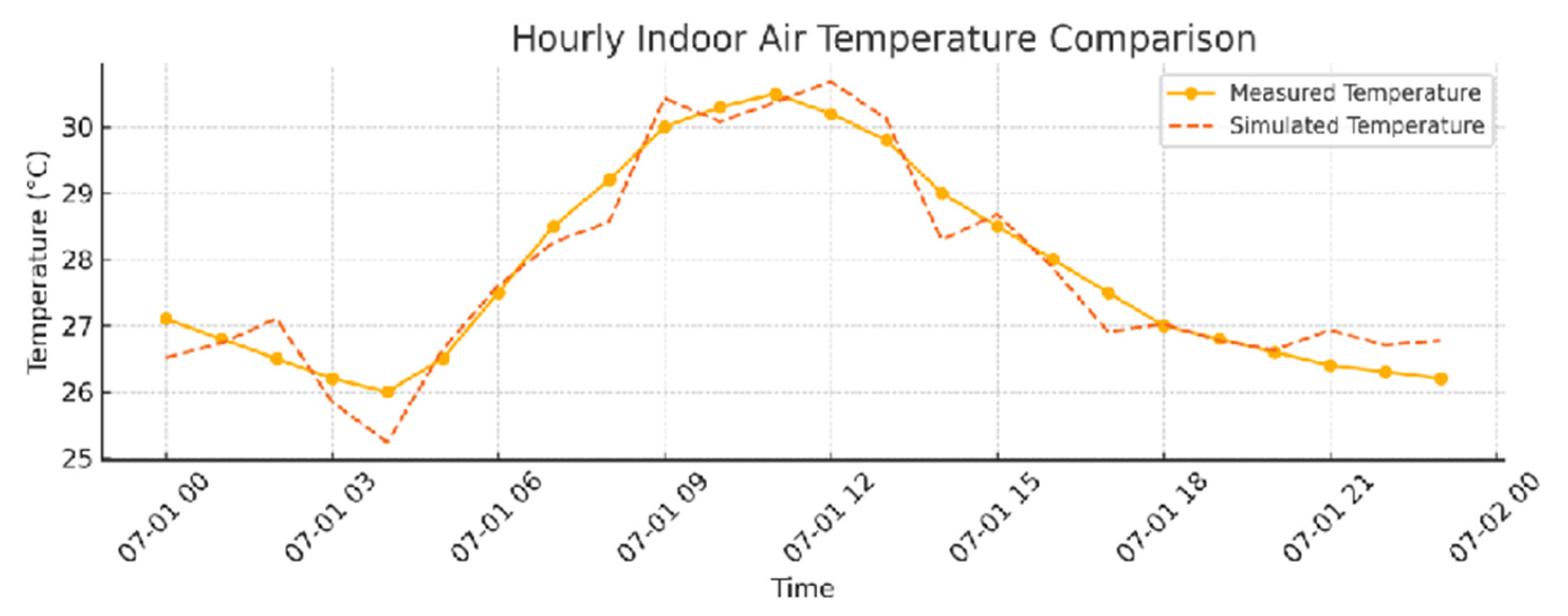

Figure 8.

Hourly Indoor Relative Humidity Comparison for a Typical Hot Season Day. This graph compares the simulated and actual measured hourly relative humidity variations in the classroom. The simulation shows a high degree of accuracy in predicting relative humidity, with minor deviations during peak temperature periods.

Figure 8.

Hourly Indoor Relative Humidity Comparison for a Typical Hot Season Day. This graph compares the simulated and actual measured hourly relative humidity variations in the classroom. The simulation shows a high degree of accuracy in predicting relative humidity, with minor deviations during peak temperature periods.

To validate the simulation results from the multi-objective optimization framework, a case study was conducted on a representative school building in Guangzhou’s Huadu District. Indoor environmental parameters, such as temperature and relative humidity, were measured and compared with the simulation data. Measurements were taken over typical summer and winter weeks using a HOBO U12 Data Logger, placed 1.1 meters above the floor, with recordings every 5 minutes. Meteorological data from the China Meteorological Administration’s typical meteorological year (TMY) dataset served as input for the simulation model.

The findings of this validation study robustly support the application of the multi-objective optimization framework and simulation model for forecasting the indoor climate conditions in school classrooms. These results affirm the model’s utility in designing energy-efficient windows that also ensure thermal comfort in hot-humid environments.

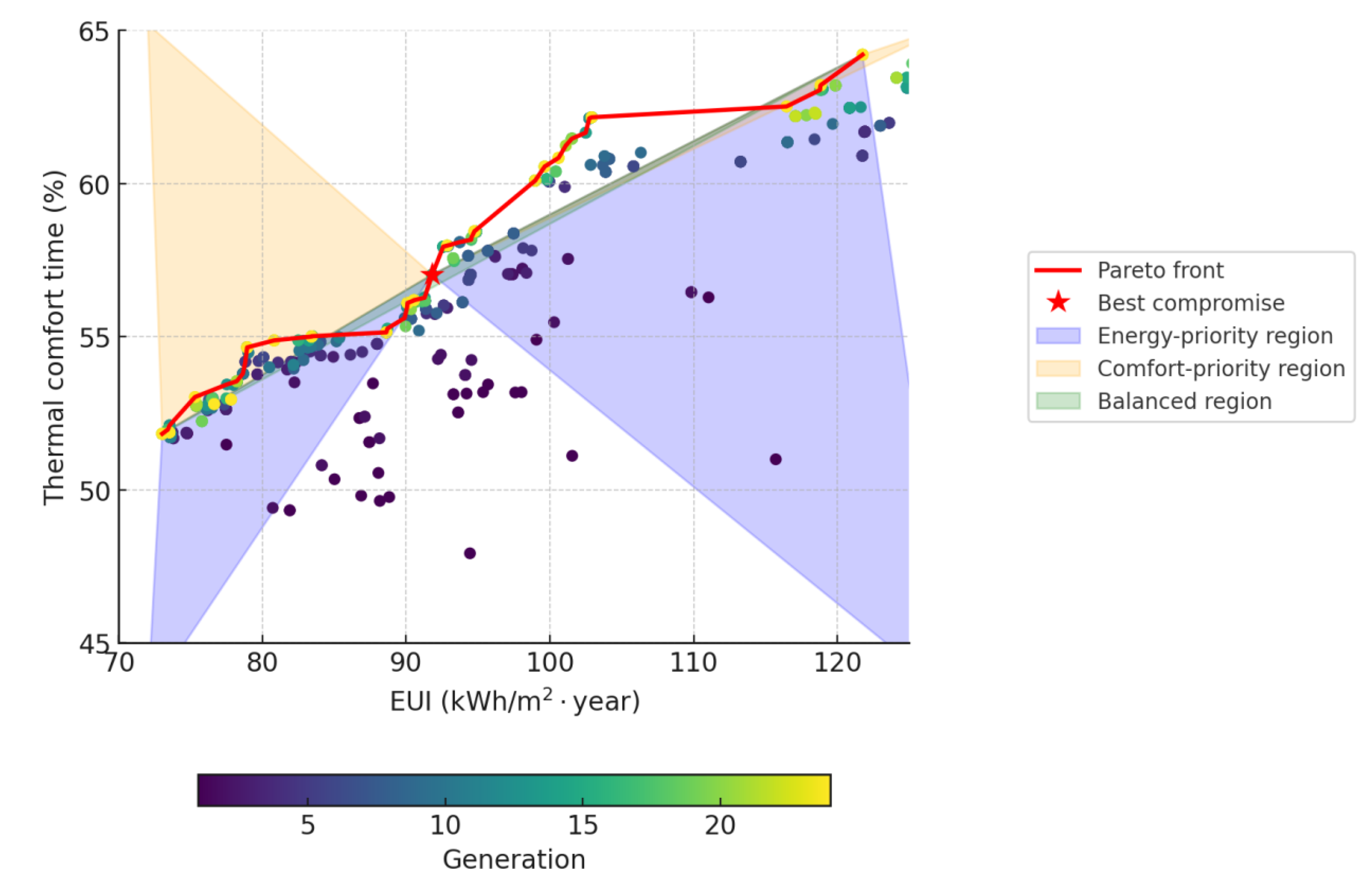

3.3. Multi-Objective Optimization Results

The present study employed a multi-objective optimization framework, leveraging the NSGA-II algorithm and EnergyPlus simulation, to balance energy use intensity (EUI) and thermal comfort time ratio (TCTR) for school buildings in a hot-humid climate. By systematically adjusting 1000 distinct window design configurations, the optimization process generated 70 Pareto-optimal solutions, effectively elucidating the inherent trade-offs between energy efficiency and thermal comfort. The results reveal a non-linear relationship between these two objectives, whereby improvements in one often lead to a concomitant decrease in the other.

Figure 9.

Pareto Front of Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort. This figure illustrates the non-linear relationship between Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR), with the red line representing the Pareto front. The trade-offs between these two objectives are clearly visible across the optimized solutions. This figure helps demonstrate how varying the design parameters results in a balance between energy use and comfort.

Figure 9.

Pareto Front of Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort. This figure illustrates the non-linear relationship between Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR), with the red line representing the Pareto front. The trade-offs between these two objectives are clearly visible across the optimized solutions. This figure helps demonstrate how varying the design parameters results in a balance between energy use and comfort.

The Balanced Solution offers an optimal compromise between the conflicting goals of energy consumption and occupant comfort in educational buildings. This approach is particularly effective for environments like classrooms, where energy efficiency and thermal comfort are crucial for sustainability. The optimization results highlight the necessity of balancing Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Temperature Range (TCTR) in school building design. The Balanced Solution achieves notable enhancements in both energy efficiency and comfort without significant trade-offs, ensuring minimized energy use while maximizing occupant comfort, consistent with sustainable building design objectives [

72,

73].

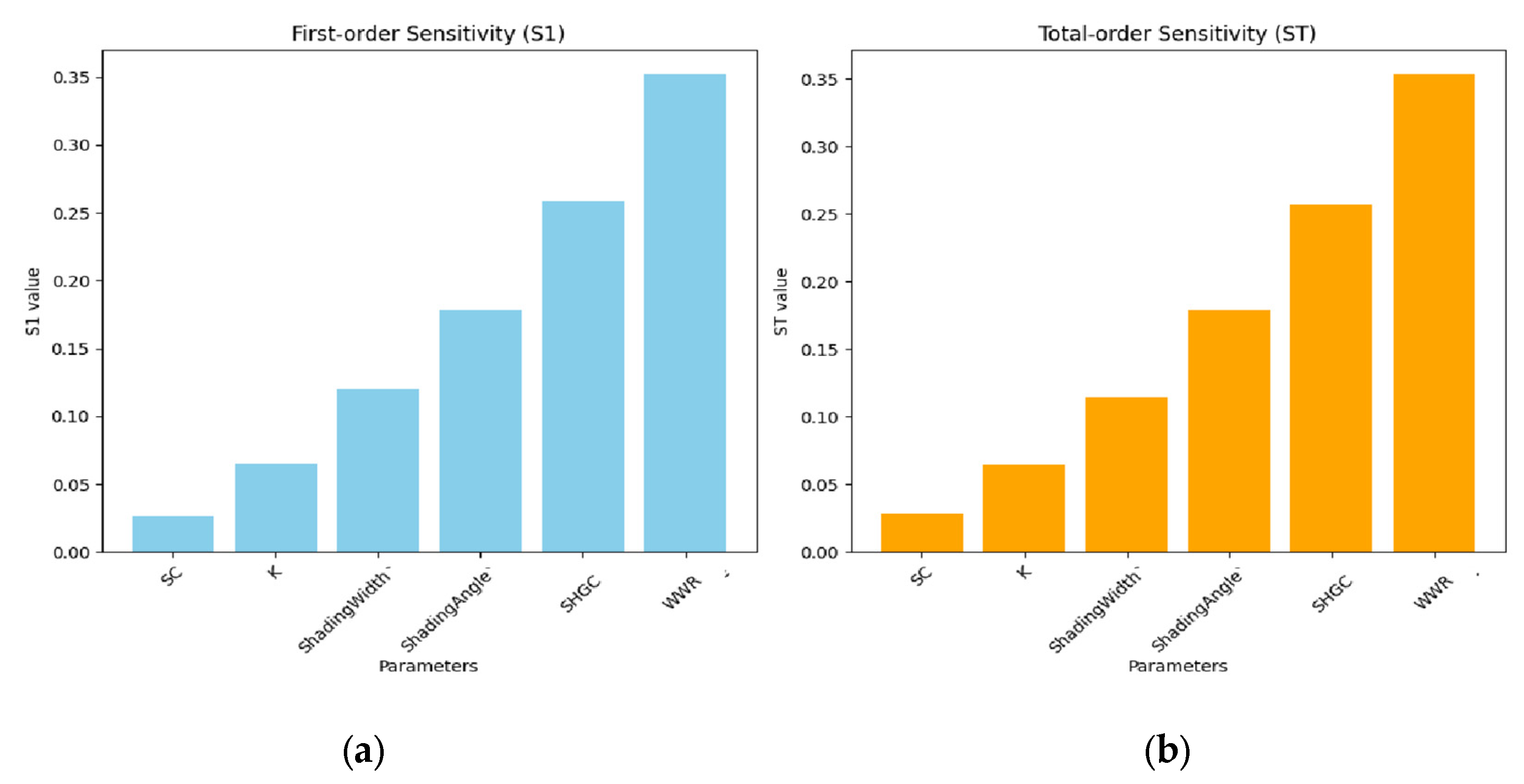

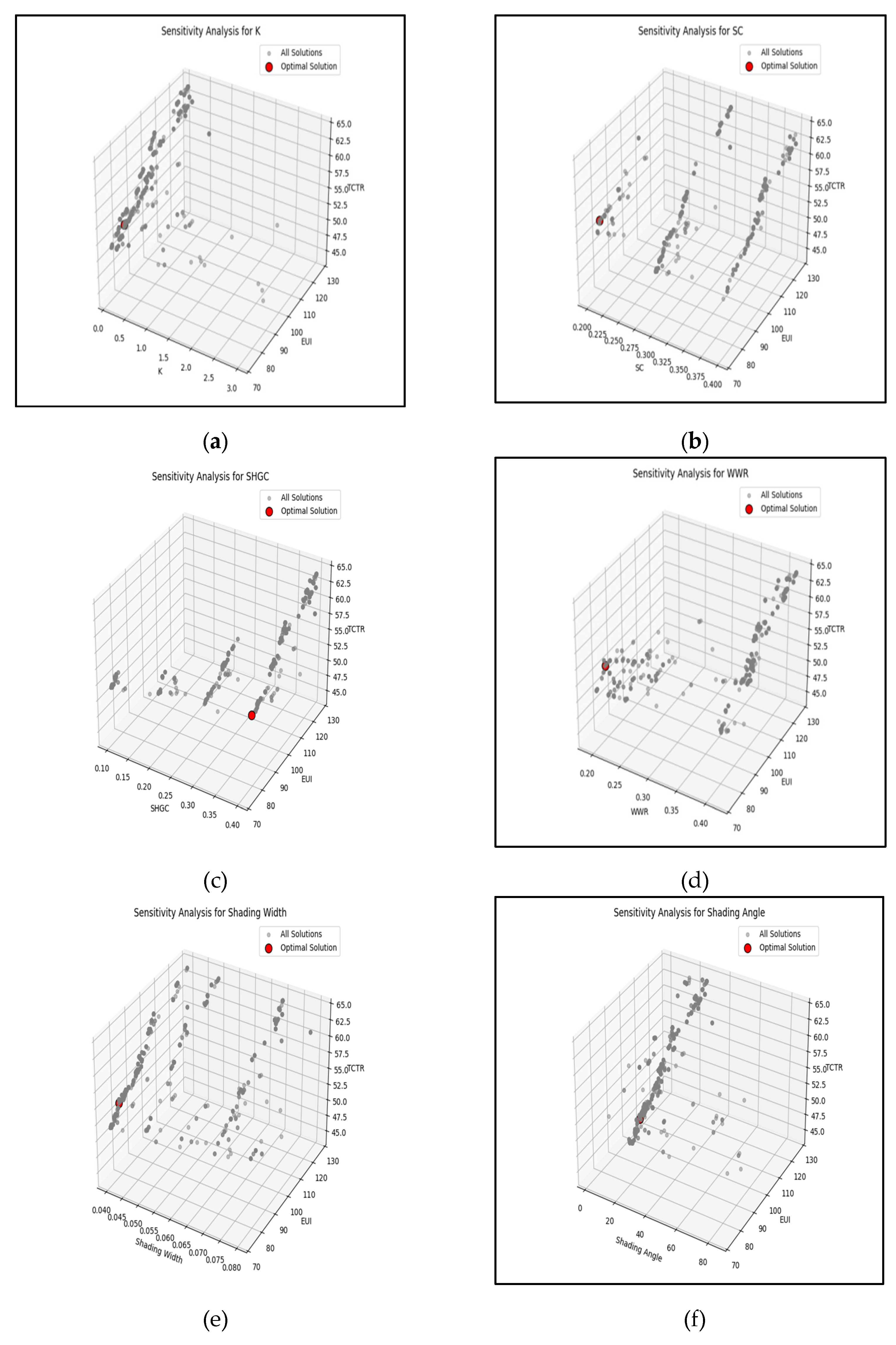

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis Results

Sobol sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of critical window design parameters on Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR). Sobol indices were employed to quantify each input parameter’s contribution to the variance in the outputs. These indices decompose the total variance to evaluate both the direct effect of individual parameters (first-order indices) and the combined effect of parameter interactions (total-order indices) [

74].

First-order Sobol indices reveal that the Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) are the primary factors influencing both Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Total Cooling Thermal Requirement (TCTR). These parameters significantly affect the variance in both objectives, underscoring their importance in optimizing energy efficiency and thermal comfort. Additionally, total-order Sobol indices underscore the interactions between WWR and Shading Coefficient (SC), indicating that their combination markedly impacts both EUI and TCTR [

75].

Figure 10.

First-order and Second-order Sobol Sensitivity Analysis Results. This figure presents the results of the first- and second-order Sobol sensitivity analysis for EUI and TCTR, further revealing the interaction effects among the design parameters. As shown in the graph, WWR and SHGC exhibit the highest sensitivity indices in all solutions, signifying their dominant role in optimizing both energy use and thermal comfort. The figure also highlights the optimal solution location, providing further insights into the influence of each parameter on building energy efficiency and comfort.

Figure 10.

First-order and Second-order Sobol Sensitivity Analysis Results. This figure presents the results of the first- and second-order Sobol sensitivity analysis for EUI and TCTR, further revealing the interaction effects among the design parameters. As shown in the graph, WWR and SHGC exhibit the highest sensitivity indices in all solutions, signifying their dominant role in optimizing both energy use and thermal comfort. The figure also highlights the optimal solution location, providing further insights into the influence of each parameter on building energy efficiency and comfort.

The Sobol sensitivity analysis identified the Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) as the primary factors affecting Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR). Their significant impact on energy efficiency and occupant comfort underscores the need to prioritize these parameters in optimization efforts. The analysis also highlighted the interaction between various parameters, particularly WWR and Shading Coefficient (SC), indicating the necessity of an integrated approach to parameter optimization. Focusing on these critical factors can guide design decisions to improve energy efficiency while maintaining thermal comfort in school buildings in hot-humid climates. These insights provide architects and engineers with practical guidance for balancing energy performance and occupant comfort [

76].

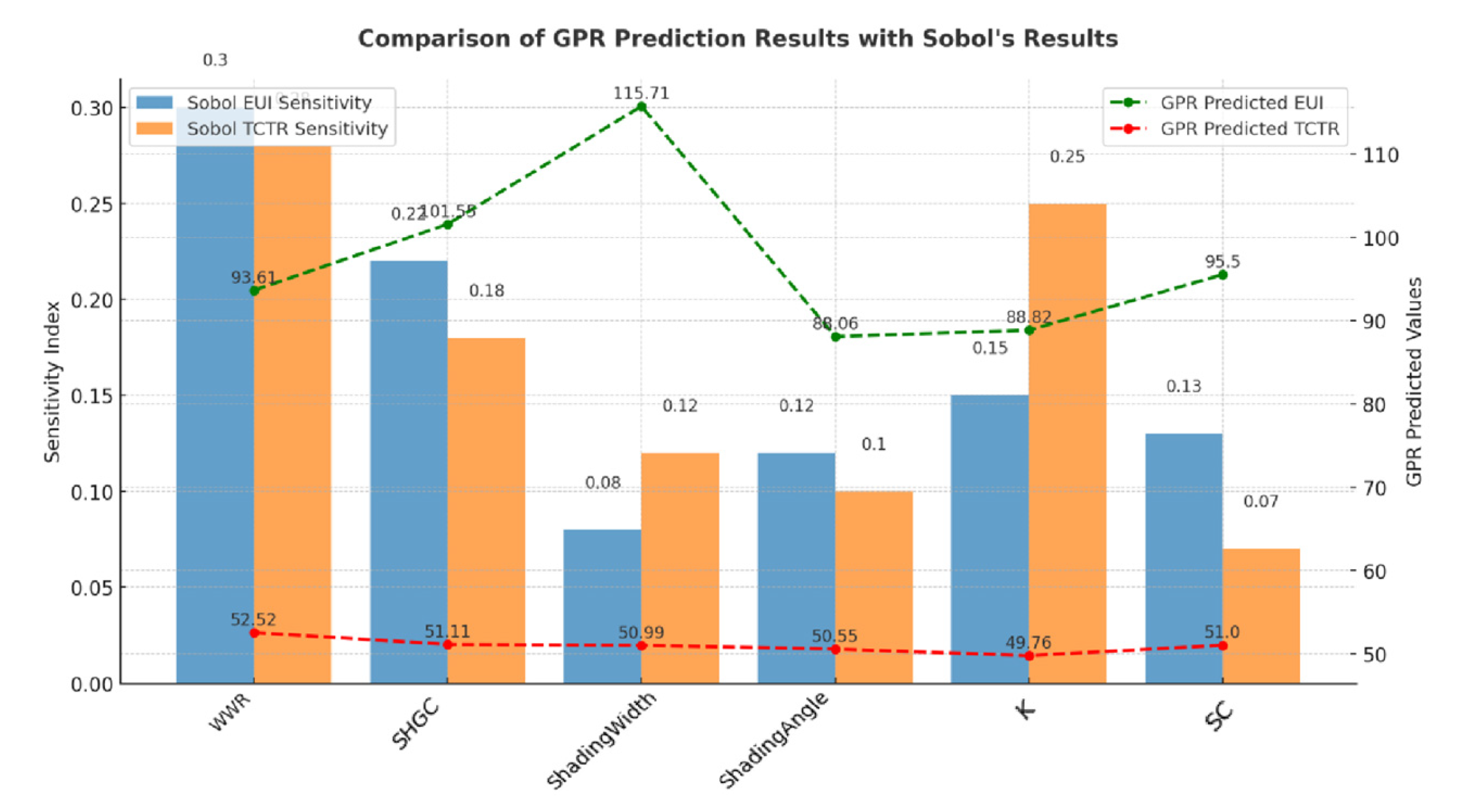

3.5. Machine Learning GPR Verification

The Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model was utilized to predict Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) based on building design parameters. This probabilistic model is especially beneficial in optimization tasks where simulation-based evaluations are computationally intensive. By approximating the simulation model, GPR provides quicker predictions with associated uncertainty, making it well-suited for large-scale optimization challenges [

77].

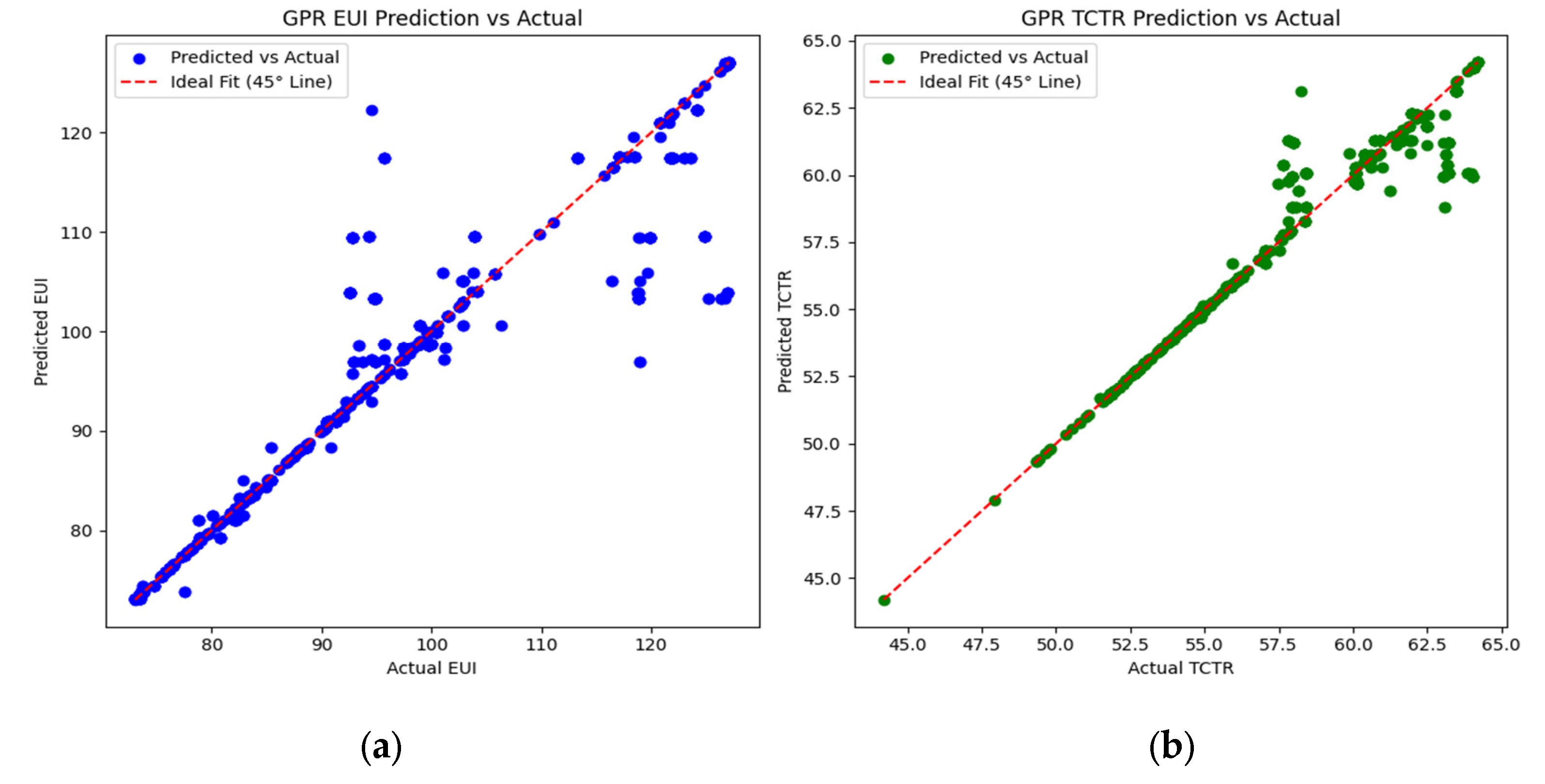

The performance of the Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model was validated by comparing the predicted values to the actual measured data for both Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Temperature Range (TCTR). The validation analysis revealed a strong correlation between the predicted and observed results, with R2 values of 0.91 for EUI and 0.95 for TCTR, confirming the robustness of the model. Additionally, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values for both metrics were low, further substantiating the accuracy of the GPR model in predicting the outcomes.

Table 4.

GPR Model Verification Results.

Table 4.

GPR Model Verification Results.

| Metric |

EUI (R2) |

TCTR (R2) |

EUI (RMSE) |

TCTR (RMSE) |

| Training Set |

0.91 |

0.95 |

4.5 |

2.3 |

| Test Set |

0.89 |

0.94 |

5.1 |

2.7 |

The GPR model was validated using a test set of data, and the residual plot in

Figure 11 illustrates a strong agreement between the predicted and actual values, with no significant bias in the model’s predictions.

SHAP analysis further validated the model, quantifying each input parameter’s contribution to predictions [

78]. The SHAP values confirmed the Sobol sensitivity analysis results, identifying the Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) as the most influential parameters for both EUI and TCTR. These results underscore the importance of these parameters in the optimization process.

The validated Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model exhibits high predictive accuracy for Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Total Carbon Emission (TCTR). The agreement between SHAP analysis and Sobol sensitivity analysis reinforces the GPR model’s reliability in guiding optimization decisions [

79]. These results confirm GPR’s effectiveness as a robust tool for predicting building performance in multi-objective optimization frameworks, facilitating faster and more efficient evaluations during the design phase.

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimization Results

4.1.1. Optimal Solution

The Baseline Classroom Design exhibited an Energy Use Intensity (EUI) of 101.55 kWh/m2·year and a Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) of 51.11%. Comparison with the optimized solutions derived through the multi-objective optimization framework reveals a clear trade-off between energy efficiency and thermal comfort, underscoring the challenges in reconciling these frequently conflicting objectives.

Table 5 illustrates that the Balanced Solution achieves a 6.7% reduction in energy consumption and a 14.3% improvement in thermal comfort. This approach is particularly suitable for educational buildings, like schools, where energy efficiency and occupant comfort are critical.

The analysis reveals a nonlinear trade-off between energy use intensity (EUI) and thermal comfort (TCTR), whereby enhancing one often results in diminished performance of the other. Consequently, identifying a balanced solution becomes crucial. The Balanced Solution provides an optimal equilibrium, achieving substantial improvements in both metrics without necessitating extreme compromises. This is particularly advantageous for school buildings, where thermal comfort and energy efficiency hold equal importance for long-term sustainability.

The findings underscore the pivotal role of the Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) in modulating both Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Temperature Range (TCTR). These parameters must be prioritized in the optimization process. Specifically, WWR regulates the influx of heat into the building, thereby influencing energy consumption, while SHGC is critical in balancing solar heat gain and natural lighting, which directly impacts occupant comfort. Consequently, the judicious management of these parameters is essential to optimize energy efficiency and thermal comfort in hot-humid climates [

80].

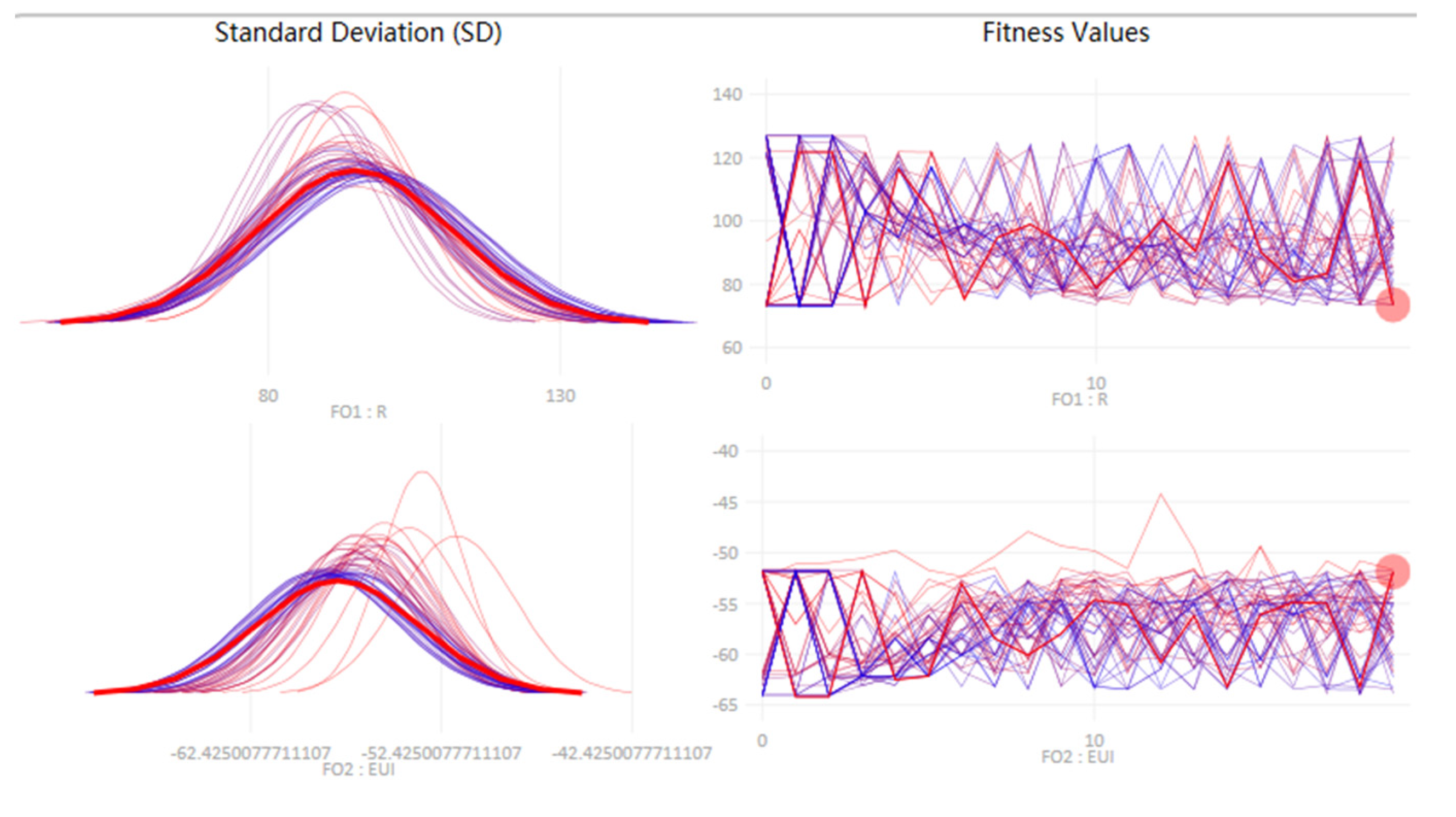

4.1.2. Optimal Solution

The optimization analysis reveals a critical trade-off between Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) inherent to the multi-objective optimization process. Improving energy efficiency often compromises thermal comfort, while prioritizing comfort leads to higher energy use. This non-linear relationship between the two objectives highlights the need to carefully weigh their relative importance based on the specific goals of the project [

81].

Figure 12.

Wallacei Optimization Trend. This figure demonstrates the optimization trend over the course of the multi-objective optimization process. As the generations progress, the average EUI decreases, and the average TCTR increases. The figure also depicts the standard deviations of EUI and TCTR, reflecting both the diversity and the convergence of the solution set over time.

Figure 12.

Wallacei Optimization Trend. This figure demonstrates the optimization trend over the course of the multi-objective optimization process. As the generations progress, the average EUI decreases, and the average TCTR increases. The figure also depicts the standard deviations of EUI and TCTR, reflecting both the diversity and the convergence of the solution set over time.

The analysis identifies the most influential design parameters: Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC). A lower WWR reduces energy consumption by limiting solar heat gain, while a higher SHGC optimizes the balance between heat gain and natural lighting to maintain thermal comfort. These two parameters are crucial for achieving an equilibrium between energy efficiency and thermal comfort in hot-humid climates [

82].

In educational buildings like schools, where thermal comfort and energy efficiency are crucial, the Balanced Solution provides a practical compromise. This approach allows designers to address both energy efficiency and occupant comfort, creating sustainable and comfortable environments without significant sacrifices in either aspect.

The optimization analysis offers crucial insights for designers, highlighting the importance of balancing energy efficiency and thermal comfort through parameters such as WWR and SHGC. The Balanced Solution is especially relevant for educational buildings, significantly enhancing energy use and comfort while minimizing trade-offs between these objectives [

83].

4.2. Sensitivity Index Analysis

The Sobol sensitivity analysis provided valuable insights into the window design parameters that most significantly impact Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) [

84]. The analysis identified Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) as the most influential parameters for both energy efficiency and thermal comfort, highlighting their crucial role in the optimization process.

By optimizing the window-to-wall ratio (WWR) and solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC), designers can effectively balance energy efficiency and occupant comfort. WWR primarily impacts energy consumption by regulating solar heat gain, while SHGC is crucial for maintaining comfort through controlling heat transfer into the building. Furthermore, the interplay between WWR and shading coefficient (SC) was found to be significant, indicating that jointly optimizing these parameters could yield enhanced overall performance [

85].

Figure 13.

(a)~ (f) Sobol Sensitivity Analysis Diagram for Each Parameter. These charts clearly illustrate the sensitivity of each design parameter, with WWR and SHGC exhibiting high sensitivity indices across all solutions, including the optimal solution. This demonstrates that these parameters are pivotal in optimizing EUI and TCTR. Moreover, the charts highlight the optimal solution location, providing further insight into how each parameter impacts building energy efficiency and comfort.

Figure 13.

(a)~ (f) Sobol Sensitivity Analysis Diagram for Each Parameter. These charts clearly illustrate the sensitivity of each design parameter, with WWR and SHGC exhibiting high sensitivity indices across all solutions, including the optimal solution. This demonstrates that these parameters are pivotal in optimizing EUI and TCTR. Moreover, the charts highlight the optimal solution location, providing further insight into how each parameter impacts building energy efficiency and comfort.

The Sobol analysis results aligned with those from Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), reinforcing the significance of WWR and SHGC in optimizing EUI and TCTR. These findings provide designers with critical insights, allowing them to prioritize key parameters when optimizing window designs for school buildings in hot-humid climates [

86].

4.3. GPR Learning Validation

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) was leveraged to forecast Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR) based on the optimization parameters. GPR enables efficient predictions, thereby reducing the need for extensive simulations and expediting the optimization process [

87].

The accuracy of the GPR model was validated by comparing its predictions to empirical measurements of Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and Thermal Comfort Time Ratio (TCTR). The results demonstrated a strong correlation, with R2 values of 0.91 for EUI and 0.95 for TCTR, indicating the model’s high predictive capability. Furthermore, the low Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for both metrics further substantiated the model’s effectiveness.

Figure 14.

Comparison of GPR Predictions and Sobol Sensitivity Analysis. This figure contrasts the GPR model predictions for EUI and TCTR with Sobol sensitivity indices, emphasizing the alignment of both methods in identifying the key parameters, particularly WWR and SHGC.

Figure 14.

Comparison of GPR Predictions and Sobol Sensitivity Analysis. This figure contrasts the GPR model predictions for EUI and TCTR with Sobol sensitivity indices, emphasizing the alignment of both methods in identifying the key parameters, particularly WWR and SHGC.

SHAP analysis corroborated that the Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) are the most influential factors for both EUI and TCTR, aligning with the findings of the Sobol sensitivity analysis. This alignment underscores the pivotal role of these parameters in the optimization process [

88].

4.4. Practical Implications and Physical Applications

This study provides practical guidance for architects and engineers designing school buildings in hot-humid climates. The developed optimization framework offers a comprehensive method to balance energy efficiency and thermal comfort by strategically managing key window parameters, such as Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) [

89].

The design of window configurations in educational buildings can be optimized to minimize energy consumption while maximizing thermal comfort. Specifically, adjusting the window-to-wall ratio (WWR) and solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) in response to the unique climate conditions of hot-humid regions, such as Guangzhou, can significantly reduce cooling energy demand without compromising occupant comfort. This approach can be extended to large-scale educational facilities, providing a sustainable solution to the increasing need for energy-efficient school designs [

90].

The framework outlined in this study is adaptable to various building types and climates, aiding the global effort to reduce building energy consumption. By integrating multi-objective optimization with advanced simulation tools like EnergyPlus and NSGA-II, designers can systematically and efficiently explore design alternatives that balance energy efficiency with occupant comfort, addressing both environmental and human-centered objectives [

91].

By concentrating on key window design parameters, this study offers a practical tool for improving building performance in hot-humid climates. The findings guide architects and lay the groundwork for future research aimed at optimizing building designs to achieve sustainability goals and enhance occupant well-being [

92].

4.5. Limitations

The proposed multi-objective optimization framework exhibits notable robustness, yet several limitations warrant attention. Primarily, the model is based on a simplified classroom layout with fixed window designs, omitting dynamic facade systems and real-time occupant behavior. Although this simplification reduces computational complexity, it may restrict the applicability of the findings to more complex educational buildings or irregularly shaped structures [

93].

The optimization results presented herein may be considered conservative when applied to future climate adaptation designs, as the underlying climate data is derived from the Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) dataset. While this dataset is representative, it does not fully capture the potential impacts of extreme weather events or long-term climate change [

94].

The simulation presupposed a uniform activity pattern and consistent device usage, neglecting the variability inherent in real school occupancy and usage. In practice, variations in occupant density, behavior, and interaction can substantially affect thermal comfort and, thus, the accuracy of the outcomes .

While integrating Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) improved optimization efficiency and reduced computational costs, prediction errors may persist, especially at the design space boundaries. Future research should focus on refining the GPR model by incorporating active learning or adaptive sampling strategies to enhance prediction accuracy [

95].

5. Conclusions

This study presents a multi-objective optimization framework targeting window configurations in school buildings situated in hot-humid climates, aiming to balance energy consumption and thermal comfort. By incorporating evolutionary algorithms, Sobol sensitivity analysis, and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), the research offers essential insights into optimizing window designs to improve building performance.

The optimization process highlights a clear trade-off between energy efficiency (EUI) and thermal comfort (TCTR). The Balanced Solution provides a practical compromise, enhancing both metrics without significant sacrifices. The Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) are identified as the most influential parameters for both EUI and TCTR, a conclusion consistently supported by various analytical methods, including SHAP and Sobol analysis.

This research significantly advances sustainable building design by offering actionable guidelines for optimizing school buildings in hot-humid climates. It provides architects and engineers with a structured framework to enhance energy efficiency while ensuring occupant comfort. Furthermore, the study illustrates the practical use of advanced machine learning models, such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), to refine optimization and lower computational costs.

The framework presented in this study offers the potential for broader application across building typologies and climatic contexts, thereby advancing the field of multi-objective optimization and contributing to the development of sustainable educational infrastructure in regions with demanding environmental conditions.

The optimization analysis offers crucial insights for designers, highlighting the necessity of balancing energy efficiency and thermal comfort through parameters like WWR and SHGC. The Balanced Solution is especially relevant for educational buildings, significantly enhancing energy efficiency and comfort while minimizing trade-offs. Future research should examine the application of these findings to larger-scale commercial and residential buildings in both hot-humid and cold climates. Additionally, adaptive building systems, such as dynamic façades and smart glazing, warrant consideration in future studies to improve performance amid varying occupancy and environmental conditions. Integrating machine learning models could further refine the optimization process, allowing real-time adjustments to building parameters based on fluctuating weather patterns and occupant behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.X.; methodology, T.X.; software, T.X.; validation, T.X.; formal analysis, T.X.; investigation, T.X.; resources, T.X.; data curation, T.X.; writing—original draft preparation, T.X.; writing—review and editing, A.S.A. and N.M.; supervision, A.S.A. and N.M.; project administration, A.S.A. and N.M.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to [reason, e.g., privacy restrictions, ongoing analysis].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Prof. Sr Ts. Dr. Azlan Shah Ali and Associate Prof. Sr Dr. Norhayati Mahyuddin for their invaluable support and guidance throughout the course of this research. Their expertise and constructive feedback have greatly contributed to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| EUI |

Energy Use Intensity |

| TCTR |

Thermal Comfort Time Ratio |

| WWR |

Window-to-Wall Ratio |

| SHGC |

Solar Heat Gain Coefficient |

| SC |

Shading Coefficient |

| NSGA-II |

Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| GPR |

Gaussian Process Regression |

| TMY |

Typical Meteorological Year |

| GB |

Green Building |

| FAR |

Floor Area Ratio |

| SVF |

Sky View Factor |

| BD |

Building Density |

| R2

|

Coefficient of Determination |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| LHS |

Latin Hypercube Sampling |

| GPR |

Gaussian Process Regression |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Building Sector Energy Consumption Report, 2023. https://www.iea.org/reports/building-sectors-energy-consumption.

- You, K.; Ren, H.; Cai, W.; Huang, R.; Li, Y. Modeling carbon emission trend in China’s building sector to year 2060. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2023, 188, 106679. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Report on Smart Education in China. Smart Education in China and Central & Eastern European Countries, Springer, 2023, pp. 11-50. [CrossRef]

- Guangzhou Education Bureau. Guangzhou Educational Statistics Yearbook, 2023.http://www.gzedu.gov.cn/.

- EDGE Buildings. Green Building Certification Standards in China, 2023.https://www.edgebuildings.com/.

- Du, X.; Liu, X.; Gao, F.; Zhou, Z. Energy saving and low carbon oriented renovation framework for educational buildings with Tianjin University case study. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 28822. [CrossRef]

- Al-Saadi, A.; Al-Saadi, S.; Khan, H.; Al-Hashim, A.; Al-Khatri, H. Judicious design solutions for zero energy school buildings in hot climates. Solar Energy 2023, 264, 112050. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.; Tang, W.; Kanjanabootra, S.; Alterman, D. Effect of architectural building design parameters on thermal comfort and energy consumption in higher education buildings. Buildings 2022, 12 (3), 329. [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Bartoli, C.; Conti, P.; Miserocchi, L.; Testi, D. Multi-objective optimization of HVAC operation for balancing energy use and occupant comfort in educational buildings. Energies 2021, 14 (10), 2847. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.-L.; Huang, A.-W.; Chen, W.-A. Considerations on envelope design criteria for hybrid ventilation thermal management of school buildings in hot-humid climates. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 5834–5845. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.; Tahmasebi, F.; Andersen, R. K.; Azar, E.; Chen, D.; Barthelmes, V.; Belafi, Z.; Berger, C.; De Simone, M.; d’Oca, S.; Hong, T.; Jin, Q.; Khovalyg, D.; Lamberts, R.; Novakovic, V.; Park, J. Y.; Plagmann, M.; Rajus, V. S.; Vellei, M.; Verbruggen, S.; Willems, E.; Yan, D.; Zhou, J. An international review of occupant-related aspects of building energy codes and standards. Building and Environment 2020, 179, 106906. [CrossRef]

- Mba, E. J.; Sam-amobi, C. G.; Okeke, F. O. An assessment of orientation on effective natural ventilation for thermal comfort in primary school classrooms in Enugu City, Nigeria. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2022, 11 (2), p.114. [CrossRef]

- Cherier, M. K.; Hamdani, M.; Kamel, E.; Guermoui, M.; Bekkouche, S. M. E. A.; Al-Saadi, S.; Djeffal, R.; Bashir, M. O.; Elshekh, A. E. A.; Drozdova, L.; Kanan, M.; Flah, A. Impact of glazing type, window-to-wall ratio, and orientation on building energy savings quality: A parametric analysis in Algerian climatic conditions. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2024, 61, 104902. [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Xie, Y.; Lin, C. Thermal environment and energy performance of a typical classroom building in a hot-humid region: A case study in Guangzhou, China. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 3226001. [CrossRef]

- Soroshnia, E.; Rahnamayizekavat, P.; Rashidi, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Samali, B. Passive intelligent kinetic external dynamic shade design for improving indoor comfort and minimizing energy consumption. Buildings 2023, 13 (4), 1090. [CrossRef]

- Lala, B.; Murtyas, S.; Hagishima, A. Indoor thermal comfort and adaptive thermal behaviors of students in primary schools located in the humid subtropical climate of India. Sustainability 2022, 14 (12), 7072. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Lu, W.; Li, D.; Kojima, S. Optimization analysis of the residential window-to-wall ratio based on numerical calculation of energy consumption in the hot-summer and cold-winter zone of China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8007. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yan, C.; Wang, G.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, K. A two-stage multi-objective optimization method for envelope and energy generation systems of primary and secondary school teaching buildings in China. Building and Environment 2021, 204, 108142. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qi, Z.; Ma, Q.; Gao, W.; Wei, X. Evolving multi-objective optimization framework for early-stage building design: Improving energy efficiency, daylighting, view quality, and thermal comfort. Building Simulation 2024, 17, 2097–2123. [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Bai, L.; Yang, L. Analysis of the long-term effects of solar radiation on the indoor thermal comfort in office buildings. Energy 2022, 247, 123499. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, J. Evaluating the improvement effect of low-energy strategies on the summer indoor thermal environment and cooling energy consumption in a library building: A case study in a hot-humid and less-windy city of China. Building Simulation 2021, 14, 1423–1437. [CrossRef]

- Mba, E. J.; Okeke, F. O.; Okoye, U. Effects of wall openings on effective natural ventilation for thermal comfort in classrooms of primary schools in Enugu metropolis, Nigeria. JP Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2021, 22 (2), 269–304. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. Optimizing energy efficiency and thermal comfort in building green retrofit. Energy 2021, 237, 121509. [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D. S.; Sivasuriyan, A.; Patchamuthu, P.; Revathy, j. Thermal performance of energy-efficient buildings for sustainable development. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 29, 51130–51142.

- Jun, H.; Fei, H. Research on multi-objective optimization of building energy efficiency based on energy consumption and thermal comfort. Building Services Engineering Research & Technology 2024, 45 (4), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, T. Multi-objective optimization of energy, visual, and thermal performance for building envelopes in China’s hot summer and cold winter climate zone. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 59, 105034. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Huang, G.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, X. Climate-change impacts on electricity demands at a metropolitan scale: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Applied Energy 2020, 261, 114295. [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.; Hassieb, M. M.; Mohamed, A. F. Exploring the impact of window design and ventilation strategies on air quality and thermal comfort in arid educational buildings. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 19596. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hou, J.; Zhang, L.; Dewancker, B. J.; Meng, X.; Hou, C. Research on energy-saving factors adaptability of exterior envelopes of university teaching-office buildings under different climates (China) based on orthogonal design and EnergyPlus. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10056. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Conant-Gilles, D.; Jia, Y.; Carl, B. Rapid modeling of large and complex high-performance buildings using EnergyPlus. 2018 Building Performance Analysis Conference and SimBuild 2018, Chicago, IL, September 26-28, 2018.

- Carlucci, S.; Bai, L.; de Dear, R.; Yang, L. Review of adaptive thermal comfort models in built environmental regulatory documents. Building and Environment 2018, 137, 73–89. [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.-R.; Han, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.-Y.; Lee, C.-C.; Fung, Y.-H. Interaction between thermal comfort, indoor air quality and ventilation energy consumption of educational buildings: A comprehensive review. Buildings 2021, 11 (12), 591. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Wang, S.; Ali, S.; Yue, T.; Liaaen, M. CBGA-ES†: A cluster-based genetic algorithm with non-dominated elitist selection for supporting multi-objective test optimization. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2024, 47 (1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Teoh, B. K.; Zhang, L. Multi-objective optimization for energy-efficient building design considering urban heat island effects. Applied Energy 2024, 376, 124117. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tam, V. W. Y.; Le, K. N. Sensitivity analysis of design variables in life-cycle environmental impacts of buildings. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 65, 105749. [CrossRef]

- McKay, M. D.; Beckman, R. J.; Conover, W. J. A comparison of three methods for selecting values of input variables in the analysis of output from a computer code. Technometrics 1979, 21 (2), 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Nghiem, T.; Morari, M.; Mangharam, R. Learning and control using Gaussian processes. Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE 9th International Conference on Cyber-Physical Systems 2018, 47, 1-10.

- Sun, Y.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Yen, G. G. A new two-stage evolutionary algorithm for many-objective optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2024, 23 (5), 112-124.

- Gao, B.; Zhu, X.; Ren, J.; Ran, J.; Kim, M. K.; Liu, J. Multi-objective optimization of energy-saving measures and operation parameters for a newly retrofitted building in future climate conditions: A case study of an office building in Chengdu. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 2269–2285.

- Obamoh, H. Y., Udeala, R. C., & Obamoh, S. O. (2025). Passive Cooling Techniques in Building Design for Hot Climates: A Nigerian Perspective. Academic World-Journal of Scientific and Engineering Innovation , 2 (1). https://academicworldpublisher.co.uk/index.php/awjsei/article/view/34.

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A. L.; Paço, A. d.; Anholon, R.; Rampasso, I. S.; Ng, A.; Balogun, A. L.; Kondev, B.; Brandli, L. L. A Comparative Study of Approaches Towards Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Use at Higher Education Institutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117728.

- Kolokotsa, D.; Yang, J.; Pantazaras, A. Energy Efficiency and Conservation Consideration for the Design of Buildings for Hot and Humid Regions. In Building in Hot and Humid Regions: Historical Perspective and Technological Advances; Enteria, N., Avbi, H., Santamouris, M., Eds.; Springer: 2019; pp. 107–135.

- Yakut, M. Z.; Esen, S. Impact of energy efficient design parameters on energy consumption in hot-humid climate zones. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2020, 6 (3), 197–206. [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Li, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, J. Optimization of window-to-wall ratio with sunshades in China low latitude region considering daylighting and energy saving requirements. Appl. Energy 2019, 233–234, 62–70. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Mao, F.; Liu, Q. Human Comfort in Indoor Environment: A Review on Assessment Criteria, Data Collection and Data Analysis Methods. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 5296–5310. [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, S.; Hayati, A.; Salmanzadeh, M. Optimization of Window-to-Wall Ratio for Buildings Located in Different Climates: An IDA-Indoor Climate and Energy Simulation Study. Energies 2021, 14 (7), 1974. [CrossRef]

- Merrin, M. J.; Meghana, C.; B., V. Evaluating the efficacy of external shading devices on building energy consumption: A case study in hot climate. Thermal Science 2025, 00, 80-80. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Sangireddy, S. A. R.; Garg, V. An approach to calculate the equivalent solar heat gain coefficient of glass windows with fixed and dynamic shading in tropical climates. J. Building Eng. 2019, 22, 90-100. [CrossRef]

- Triana, M. A.; De Vecchi, R.; Lamberts, R. Building Design for Hot and Humid Climate in a Changing World. In Building in Hot and Humid Regions: Historical Perspective and Technological Advances; Enteria, N.; Awbi, H.; Santamouris, M., Eds.; Springer: 2019; pp 59–73.

- Heidarzadeh, S.; Mahdavinajad, M.; Habib, F. External shading and its effect on the energy efficiency of Tehran’s office buildings. Environ. Prog. Sustainable Energy 2023, 42 (6), e14185. [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, M. Enhancing Daylight Comfort with Climate-Responsive Kinetic Shading: A Simulation and Experimental Study of a Horizontal Fin System. Sustainability 2024, 16 (18), 8156. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. K.; Mohapatra, S.; Sharma, R. C.; Alturjman, S.; Altirjman, C.; Mostarda, L.; Stephan, T. Retrofitting Existing Buildings to Improve Energy Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14 (2), 666. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Luo, Z.; Wang, K.; Shah, S. P. A critical review on phase change materials (PCM) for sustainable and energy efficient building: Design, characteristic, performance and application. Energy Build. 2022, 260, 111923. [CrossRef]

- Seyedzadeh, S.; Pour Rahimian, F.; Glesk, I.; Roper, M. Machine learning for estimation of building energy consumption and performance: a review. Visualization in Engineering 2018, 6, 5. [CrossRef]

- Kalmár, F.; Kalmár, T. Thermal Comfort Aspects of Solar Gains during the Heating Season. Energies 2020, 13 (7), 1702. [CrossRef]

- Alhuwayil, W. K.; Mujeebu, M. A.; Algarny, A. M. M. Impact of external shading strategy on energy performance of multi-story hotel building in hot-humid climate. Energy 2019, 169, 1166–1174. [CrossRef]

- Tan, X. Y.; Mahyuddin, N.; Kamaruzzaman, S. N.; Mat Wajid, N.; Abidin, A. M. Z. Investigation into energy performance of a multi-building complex in a hot and humid climate: efficacy of energy saving measures. Open House International 2024, 49 (3), 489–513. [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Dynamic Integration of Shading and Ventilation: Novel Quantitative Insights into Building Performance Optimization. Buildings 2025, 15 (7), 1123. [CrossRef]

- GB 50189-2015. Code for Design of Energy Efficiency in Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Chiesa, G.; Acquaviva, A.; Grosso, M.; Bottaccioli, L.; Floridia, M.; Pristeri, E.; Sanna, E. M. Parametric Optimization of Window-to-Wall Ratio for Passive Buildings Adopting a Scripting Methodology to Dynamic-Energy Simulation. Sustainability 2019, 11 (11), 3078. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, C.; Sasidhar, K.; Madhumathi, A. Energy-efficient retrofitting with exterior shading device in hot and humid climate—case studies from fully glazed multi-storied office buildings in Chennai, India. J. Asian Architect. Build. Eng. 2022, . [CrossRef]

- GB 50033-2013. Design Code for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2013.http://www.cabp.com.cn/.

- Enteria, N.; Yoshino, H. Energy-efficient and renewable energy-supported buildings in hot and humid regions. In Building in Hot and Humid Regions; Enteria, N., Awbi, H., Santamouris, M., Eds.; Springer: 2019; pp. 185–203.

- Cho, K.-j.; Cho, D.-w. Solar heat gain coefficient analysis of a slim-type double skin window system: Using an experimental and a simulation method. Energies 2018, 11 (1), 115. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.; Veras, J. C. G. A design framework for a kinetic shading device system for building envelopes. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12 (5), 837–854. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, M.; Ashrafian, T.; Demirci, C. Energy efficiency evaluation of different glazing and shading systems in a school building. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 111, 03052. [CrossRef]

- GB 50096-2011. Design Code for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.http://www.cabp.com.cn/.

- GB/T 50785-2012. Indoor Environmental Quality Standard for Classrooms; China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2012.http://www.csbz.org/.

- Yang, B.; Olofsson, T.; Wang, F.; Lu, W. Thermal Comfort in Primary School Classrooms: A Case Study under Subarctic Climate Area of Sweden. Building and Environment 2018, 135, 237–245. [CrossRef]

- GB 50666-2011. Code for Design of Green Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.http://www.cabp.com.cn/.

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Guideline 14-2014: Measurement of Energy Performance of Buildings; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/standards-and-guidelines.

- Guariso, G.; Sangiorgio, M. Improving the Performance of Multiobjective Genetic Algorithms: An Elitism-Based Approach. Information 2020, 11 (12), 587. [CrossRef]

- Javid, A. S.; Aramoun, F.; Bararzadeh, M.; Avami, A. Multi Objective Planning for Sustainable Retrofit of Educational Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 24, 100759. [CrossRef]

- Goffart, J.; Woloszyn, M. EASI RBD-FAST: An Efficient Method of Global Sensitivity Analysis for Present and Future Challenges in Building Performance Simulation. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103129. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Meng, X. A Multi-Objective Optimization Methodology for Window Design Considering Energy Consumption, Thermal Environment, and Visual Performance. Renew. Energy 2019, 134, 1190–1199. [CrossRef]

- Koç, S. G.; Kalfa, S. M. The Effects of Shading Devices on Office Building Energy Performance in Mediterranean Climate Regions. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102653. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Ho, H.; Yu, Y. Prediction of Building Electricity Usage Using Gaussian Process Regression. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101054. [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Rajasekar, E.; Natarajan, S. Multi-Objective Building Design Optimization under Operational Uncertainties Using the NSGA II Algorithm. Buildings 2020, 10 (5), 88. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.; Kristensen, M. H.; Knudsen, M. D. Prerequisites for Reliable Sensitivity Analysis of a High Fidelity Building Energy Model. Energy and Buildings 2019, 183, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Que, Y.; Yang, N.; Yan, C.; Liu, Q. Research on Multi-Objective Optimization Design of University Student Center in China Based on Low Energy Consumption and Thermal Comfort. Energies 2024, 17 (9), 2082. [CrossRef]

- Ghaderian, M.; Veysi, F. Multi-objective optimization of energy efficiency and thermal comfort in an existing office building using NSGA-II with fitness approximation: A case study. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102440. [CrossRef]

- Yue, N.; Li, L.; Morandi, A.; Zhao, Y. A metamodel-based multi-objective optimization method to balance thermal comfort and energy efficiency in a campus gymnasium. Energy Build. 2021, 253, 111513. [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Sadati, S. E.; Gharib, M. R. Effects of different window configurations on energy consumption in building: Optimization and economic analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 102099. [CrossRef]

- Nasouri, M.; Delgarm, N. A new method for simulation-based sensitivity analysis of building efficiency for optimal building energy planning: a case study of Iran. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2024, 10, 202–224.

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jin, X.; Zhou, X.; Si, B.; Shi, X. Towards adoption of building energy simulation and optimization for passive building design: A survey and a review. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1306–1316. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Y.; How, J. P. Gaussian Processes for Learning and Control: A Tutorial with Examples. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2018, 38 (5), 33–50. [CrossRef]