Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

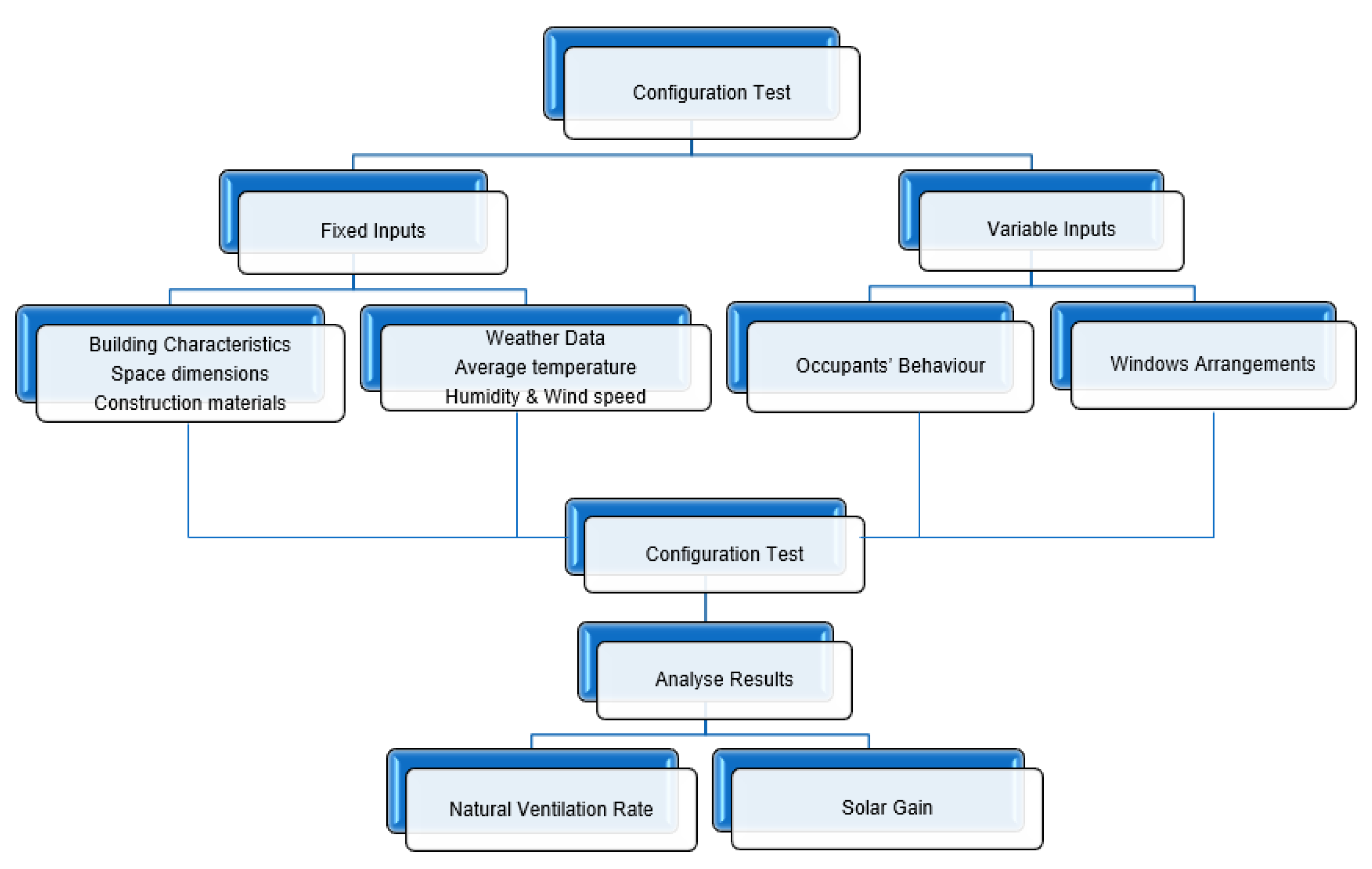

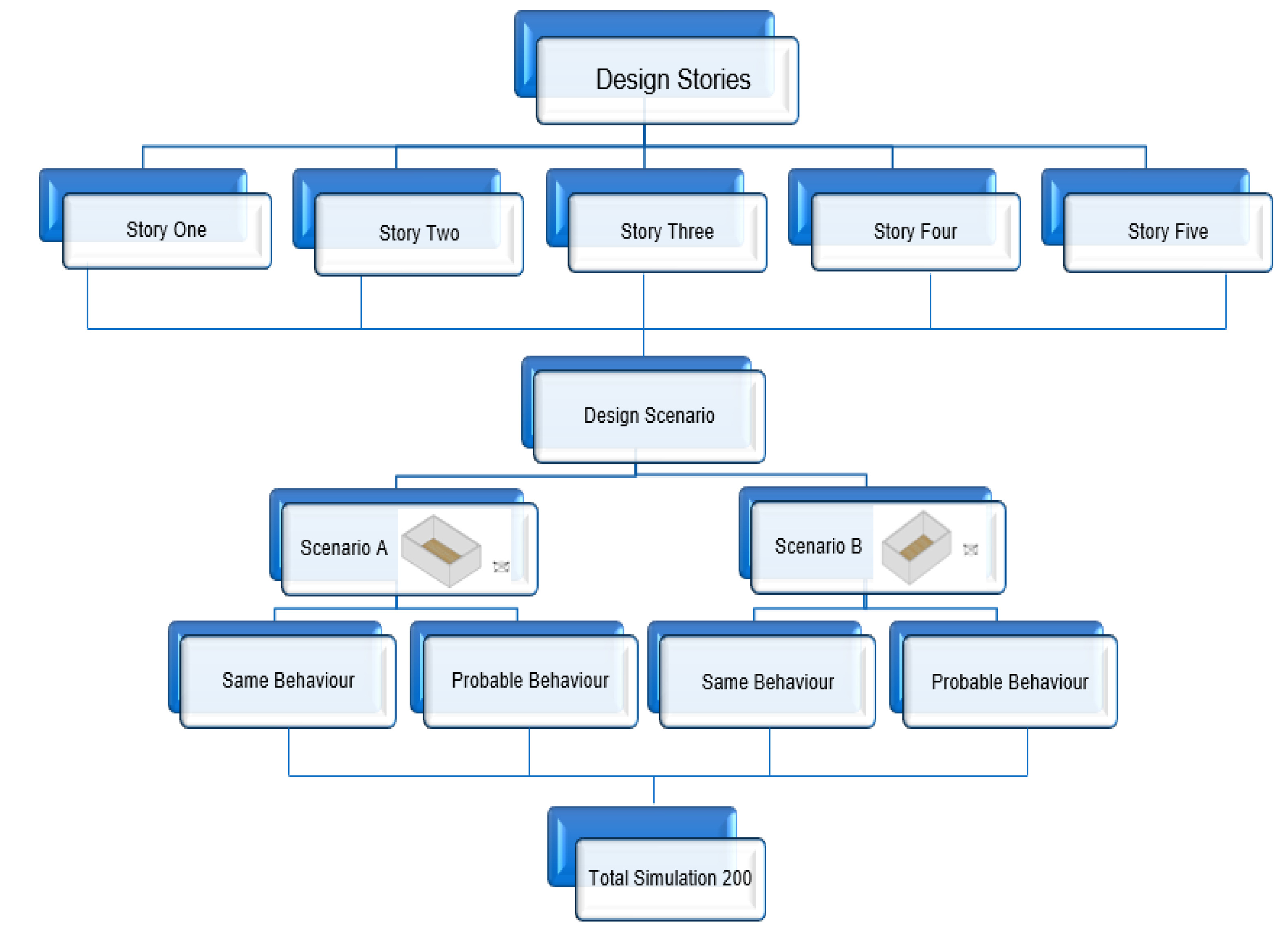

2. Methodology

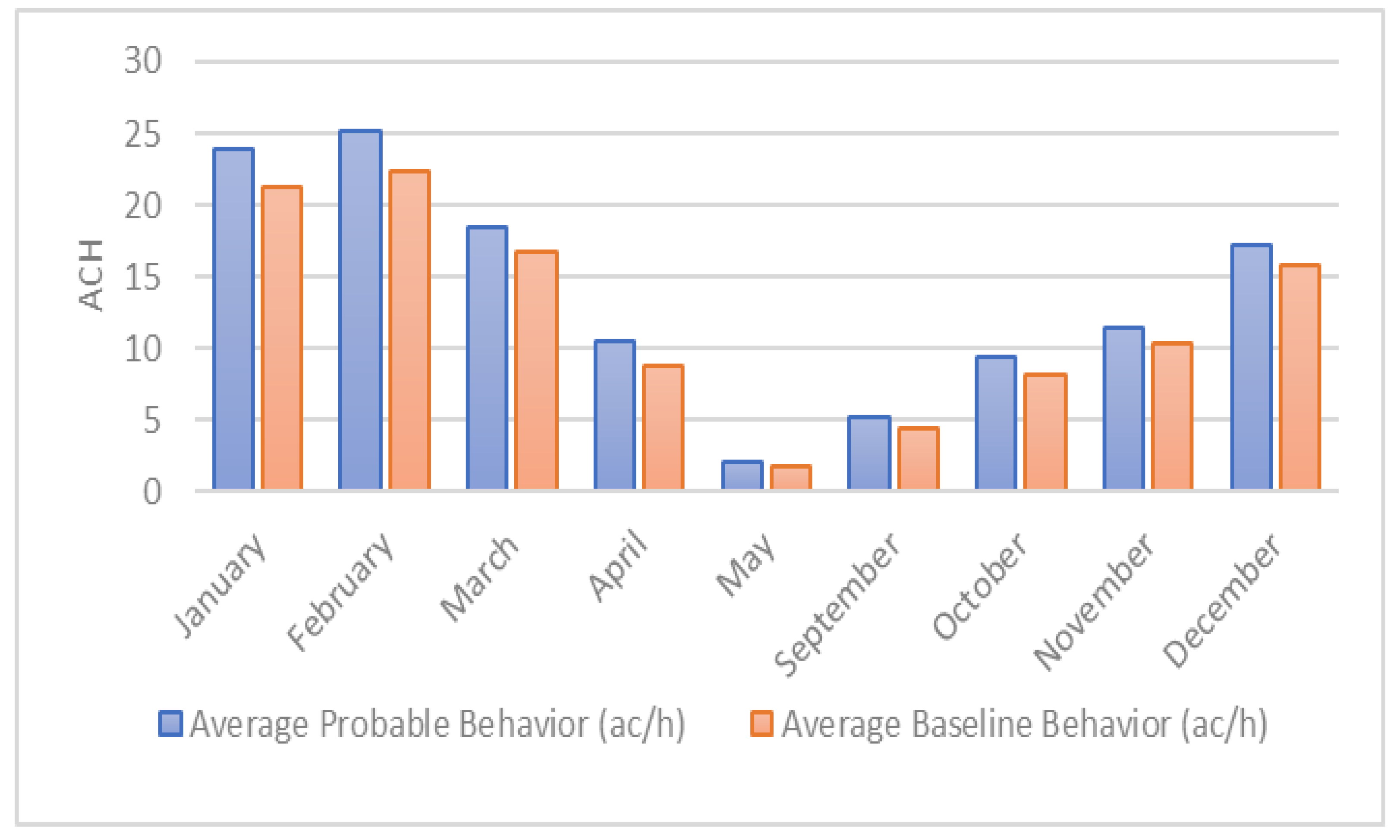

- Same Behavior (SB): a deterministic schedule representing average occupant behavior.

- Probable Behavior (PB): a stochastic (probabilistic) schedule capturing variations due to factors like comfort, privacy, and climate conditions. PB was derived by assigning time-of-day-dependent probabilities to window actions based on survey responses; no thermal comfort models (e.g., Fanger) were used. Further details are available in Appendix A.

2.1. Simulation Model Setup

- Fixed inputs, such as building characteristics, materials, spatial dimensions, and climatic data (temperature, humidity, wind speed), remain constant across all simulations to ensure comparability.

- Variable inputs, window configurations, and occupant behavior schedules change systematically to evaluate their individual and combined impacts on NV performance.

2.1.1. Fixed Inputs

2.1.2. Variable Inputs

2.2. Results Analysis Method

3. Results and Discussion

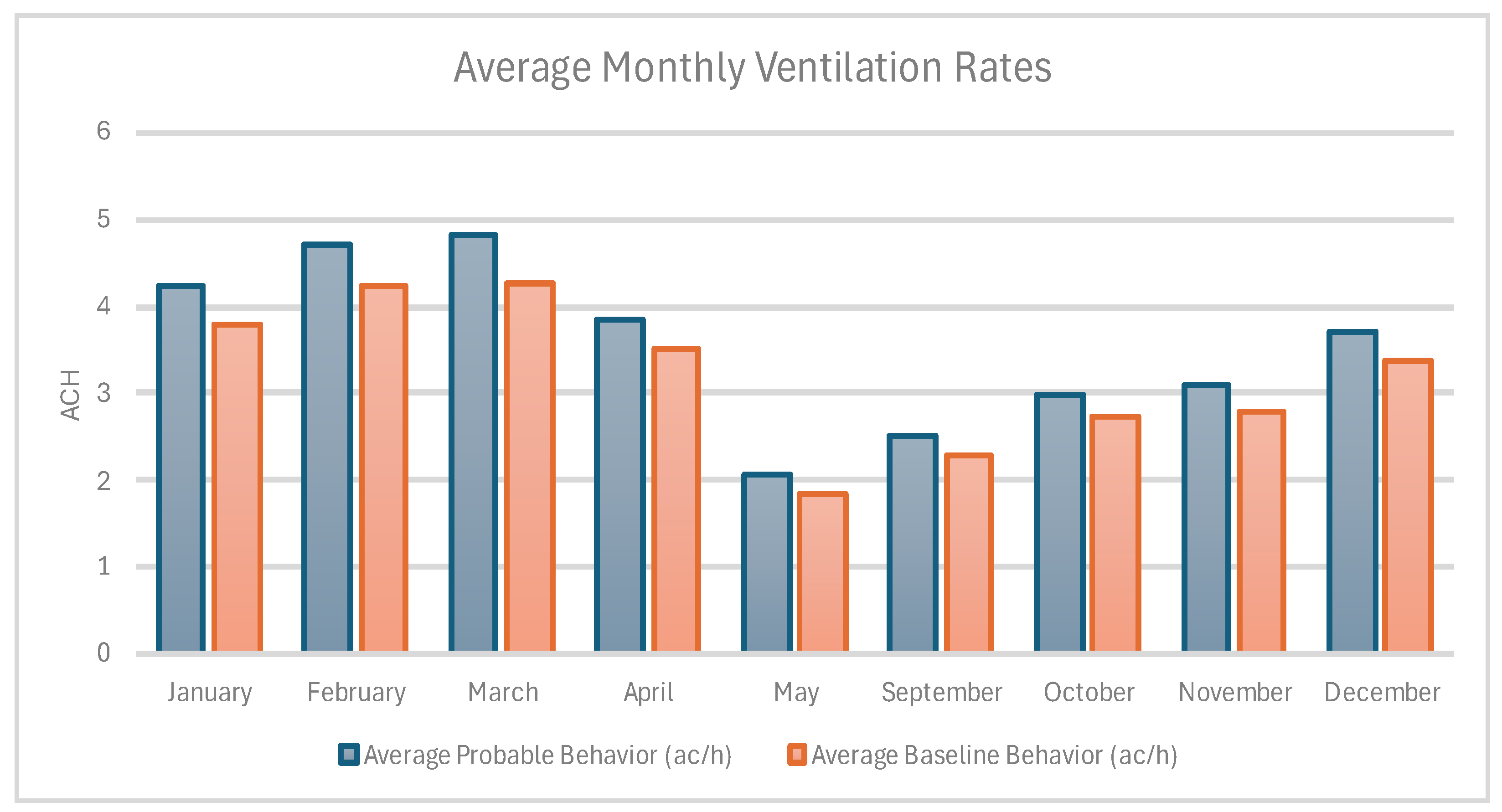

3.1. Design Story One: North-Facing Windows (WWR 45%)

3.1.1. Scenario A: 7.0 m × 2.6 m

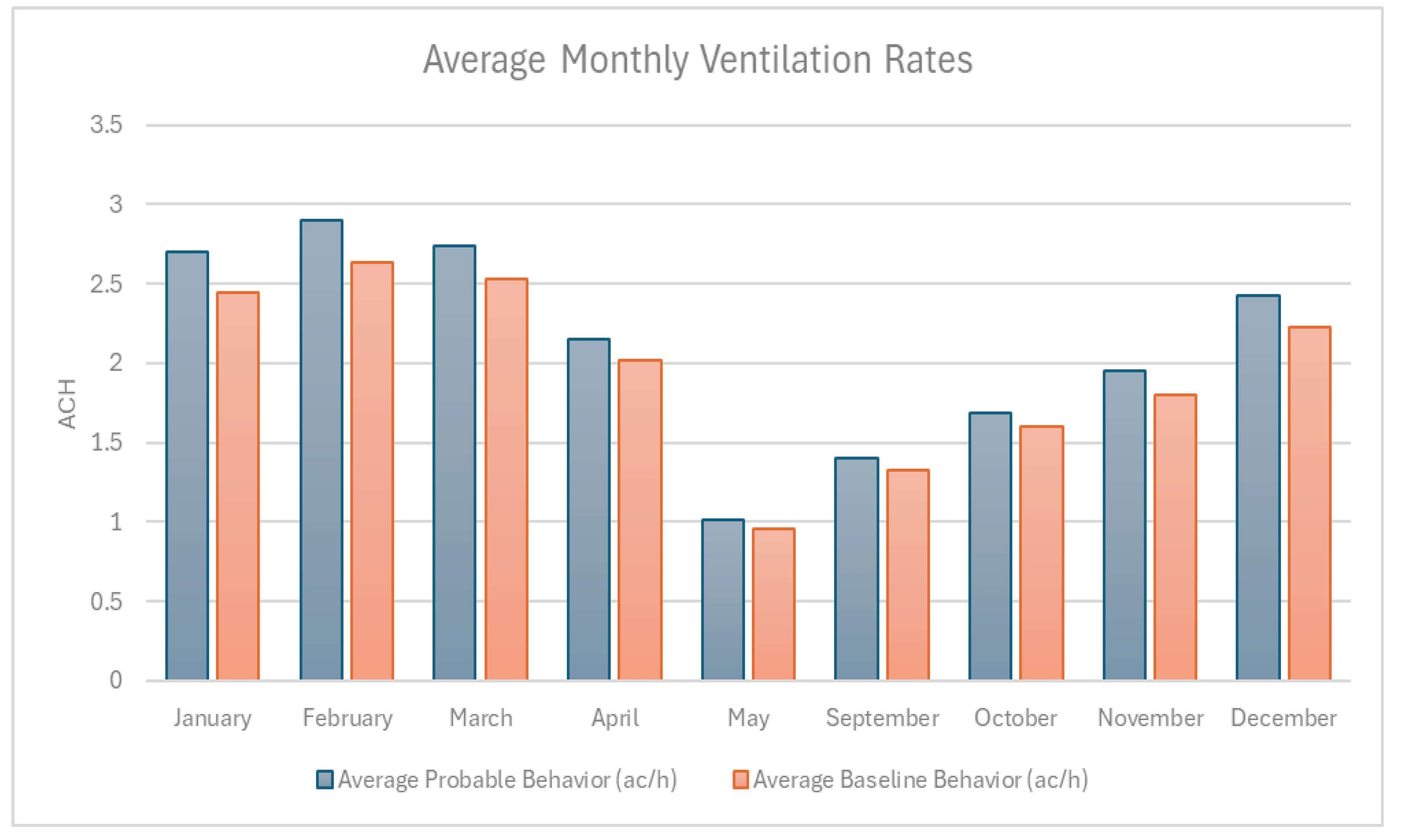

3.1.2. Scenario B: 4.5 m × 2.6 m

3.1.3. Discussion: Design Implications and Behavioral Insights

3.2. Design Story Two-East and Two-West Configuration

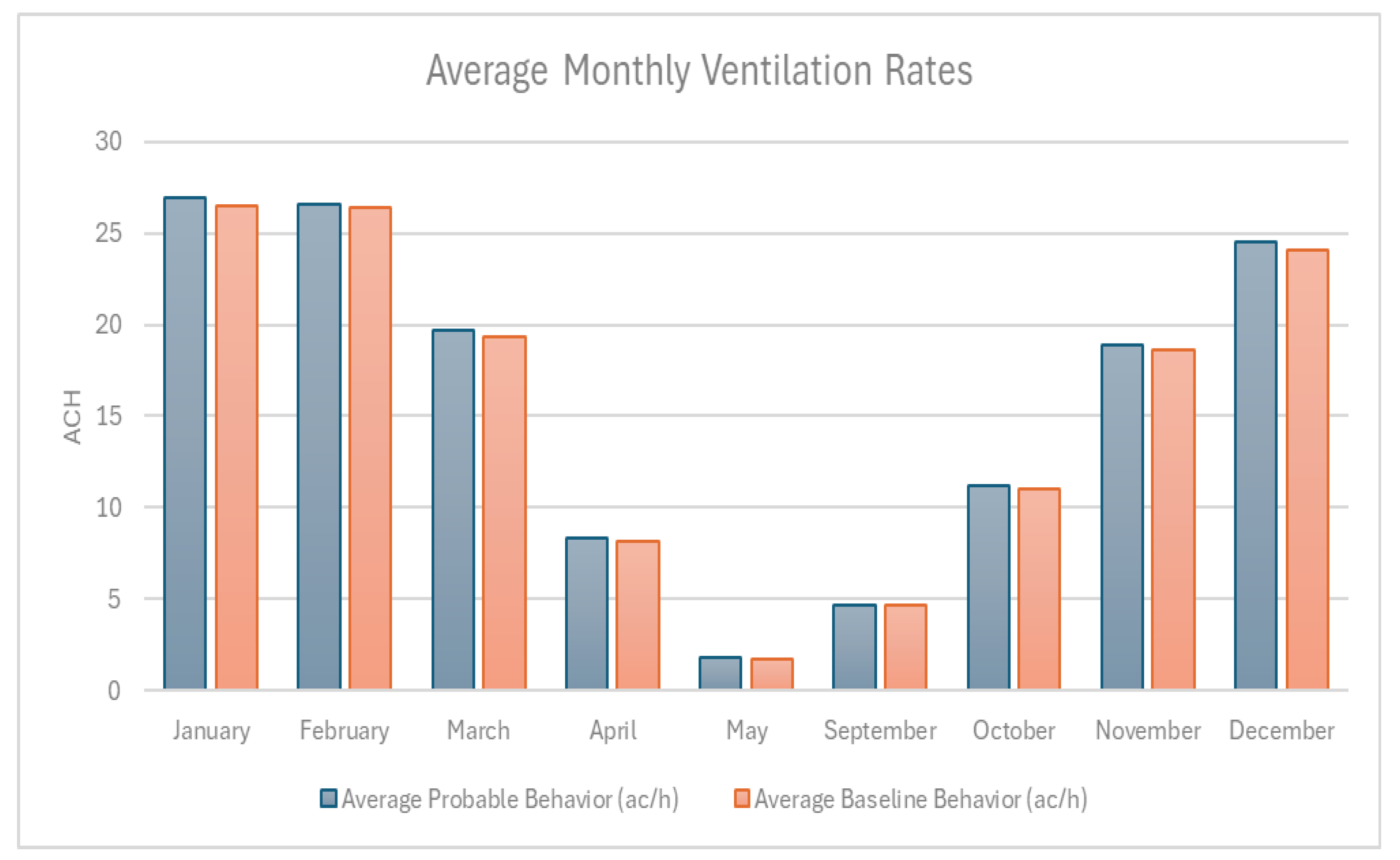

3.2.1. Scenario A: 7 m × 2.6 m East and West Walls

| Month | Highest NV (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 27.22 (5) | 25.40 (6) | 26.53 | 26.94 | +1.5% | 675.85 | 692.78 (5) | 651.07 (6) |

| Feb | 27.08 (5) | 25.27 (6) | 26.37 | 26.62 | +0.9% | 588.15 | 602.76 (5) | 567.72 (6) |

| Mar | 19.90 (5) | 18.44 (6) | 19.30 | 19.65 | +1.8% | 502.96 | 515.37 (5) | 484.88 (6) |

| Apr | 8.29 (3) | 7.83 (6) | 8.16 | 8.36 | +2.5% | 324.56 | 332.28 (5) | 313.24 (6) |

| May | 1.80 (5) | 1.65 (6) | 1.76 | 1.83 | +4.0% | 252.71 | 259.14 (5) | 243.35 (6) |

| Sep | 4.75 (3) | 4.35 (6) | 4.64 | 4.70 | +1.3% | 426.45 | 437.02 (5) | 412.11 (6) |

| Oct | 11.34 (5) | 10.60 (6) | 11.05 | 11.22 | +1.5% | 531.93 | 543.68 (5) | 514.41 (6) |

| Nov | 19.00 (5) | 17.90 (6) | 18.63 | 18.85 | +1.2% | 624.50 | 638.66 (5) | 603.80 (6) |

| Dec | 24.93 (5) | 23.05 (6) | 24.11 | 24.51 | +1.7% | 691.49 | 707.88 (5) | 667.50 (6) |

3.2.2. Scenario B: 4.5 m × 2.6 m East and West Walls

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) (Sep–May) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15.52 (January) | 0.90 (May) | 7.90 |

| 2 | 15.55 (January) | 0.91 (May) | 7.96 |

| 3 | 15.71 (January) | 0.93 (May) | 8.07 |

| 4 | 15.40 (January) | 0.90 (May) | 7.87 |

| 5 | 15.45 (January) | 0.92 (May) | 7.87 |

| 6 | 15.26 (January) | 0.91 (May) | 7.80 |

| 7 | 15.21 (January) | 0.90 (May) | 7.74 |

| 8 | 14.87 (January) | 0.89 (May) | 7.60 |

| 9 | 15.18 (January) | 0.90 (May) | 7.73 |

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

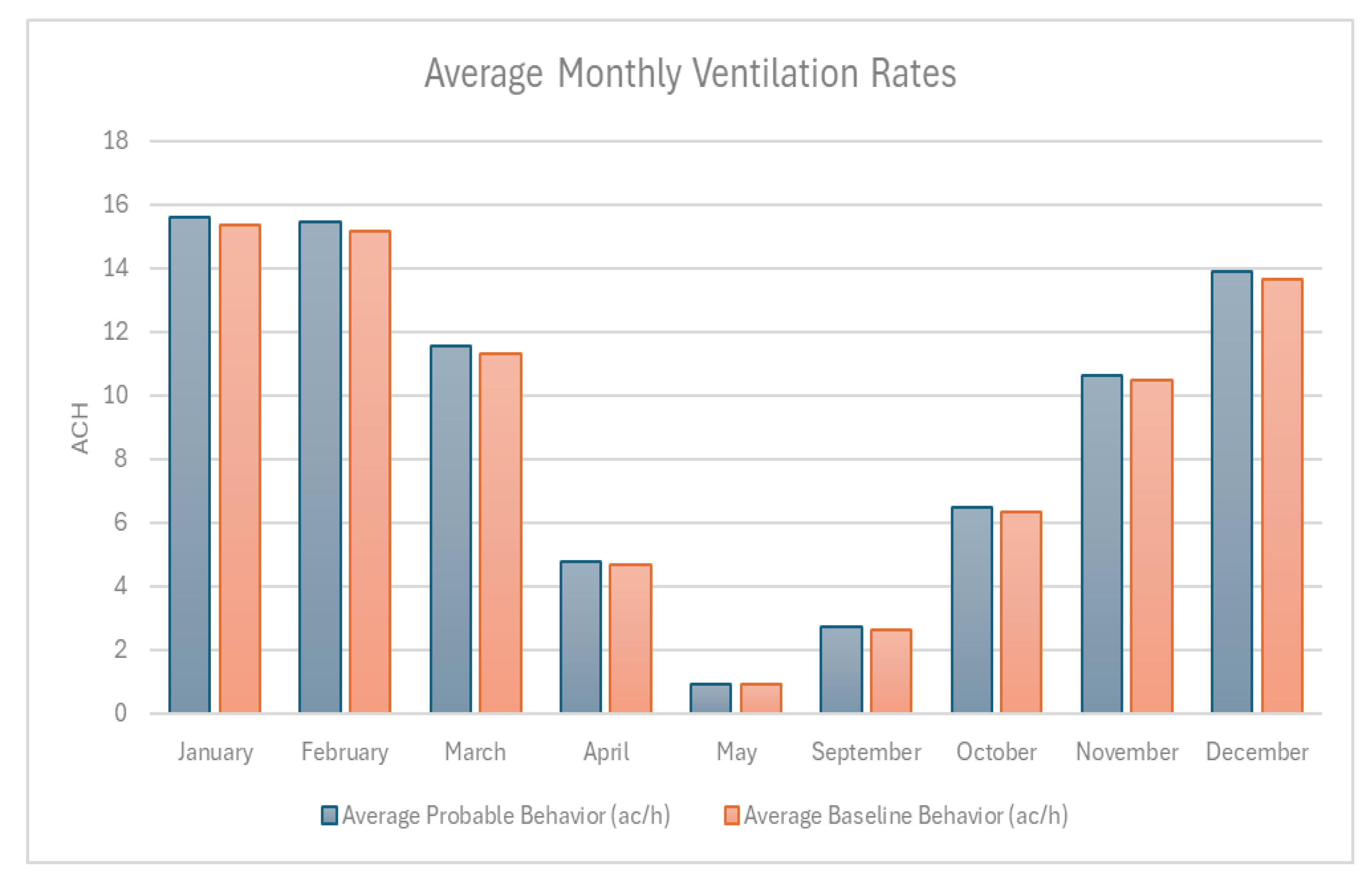

| Jan | 15.71 (3) | 14.87 (8) | 15.35 | 15.62 | +1.8% | 421.33 | 428.61 (3) | 411.11 (8) |

| Feb | 15.49 (3) | 14.65 (8) | 15.14 | 15.45 | +2.0% | 367.55 | 373.29 (3) | 358.56 (8) |

| Mar | 11.64 (3) | 11.04 (8) | 11.31 | 11.54 | +2.0% | 313.62 | 318.93 (3) | 306.37 (8) |

| Apr | 4.84 (3) | 4.52 (8) | 4.67 | 4.79 | +2.6% | 202.74 | 206.07 (3) | 198.15 (8) |

| May | 0.93 (3) | 0.89 (8) | 0.91 | 0.94 | +3.3% | 157.65 | 160.58 (3) | 153.94 (8) |

| Sep | 2.72 (5) | 2.55 (9) | 2.64 | 2.71 | +2.7% | 266.40 | 270.89 (3) | 260.51 (8) |

| Oct | 6.50 (3) | 6.12 (8) | 6.33 | 6.47 | +2.2% | 332.32 | 337.49 (3) | 325.42 (8) |

| Nov | 10.78 (3) | 10.14 (8) | 10.49 | 10.64 | +1.4% | 389.68 | 395.90 (3) | 381.66 (8) |

| Dec | 14.06 (3) | 13.18 (8) | 13.64 | 13.89 | +1.8% | 431.23 | 438.28 (3) | 421.61 (8) |

3.1.3. Discussion: Design Implications and Behavioral Insights

3.3.2. Scenario A: 7.0m × 2.6 m

| Story | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Story 1 | 24.79 (January) | 1.70 (May) | 13.40 |

| Story 2 | 24.76 (January) | 1.69 (May) | 13.38 |

| Story 3 | 24.08 (January) | 1.63 (May) | 12.96 |

| Story 4 | 24.99 (January) | 1.73 (May) | 13.57 |

| Story 5 | 30.07 (January) | 2.27 (May) | 16.67 |

| Story 6 | 23.21 (January) | 1.58 (May) | 12.49 |

| Story 7 | 27.82 (January) | 1.91 (May) | 15.27 |

| Story 8 | 27.60 (January) | 1.94 (May) | 15.17 |

| Story 9 | 21.76 (January) | 1.57 (May) | 11.68 |

| Story 10 | 28.18 (January) | 1.91 (May) | 15.42 |

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

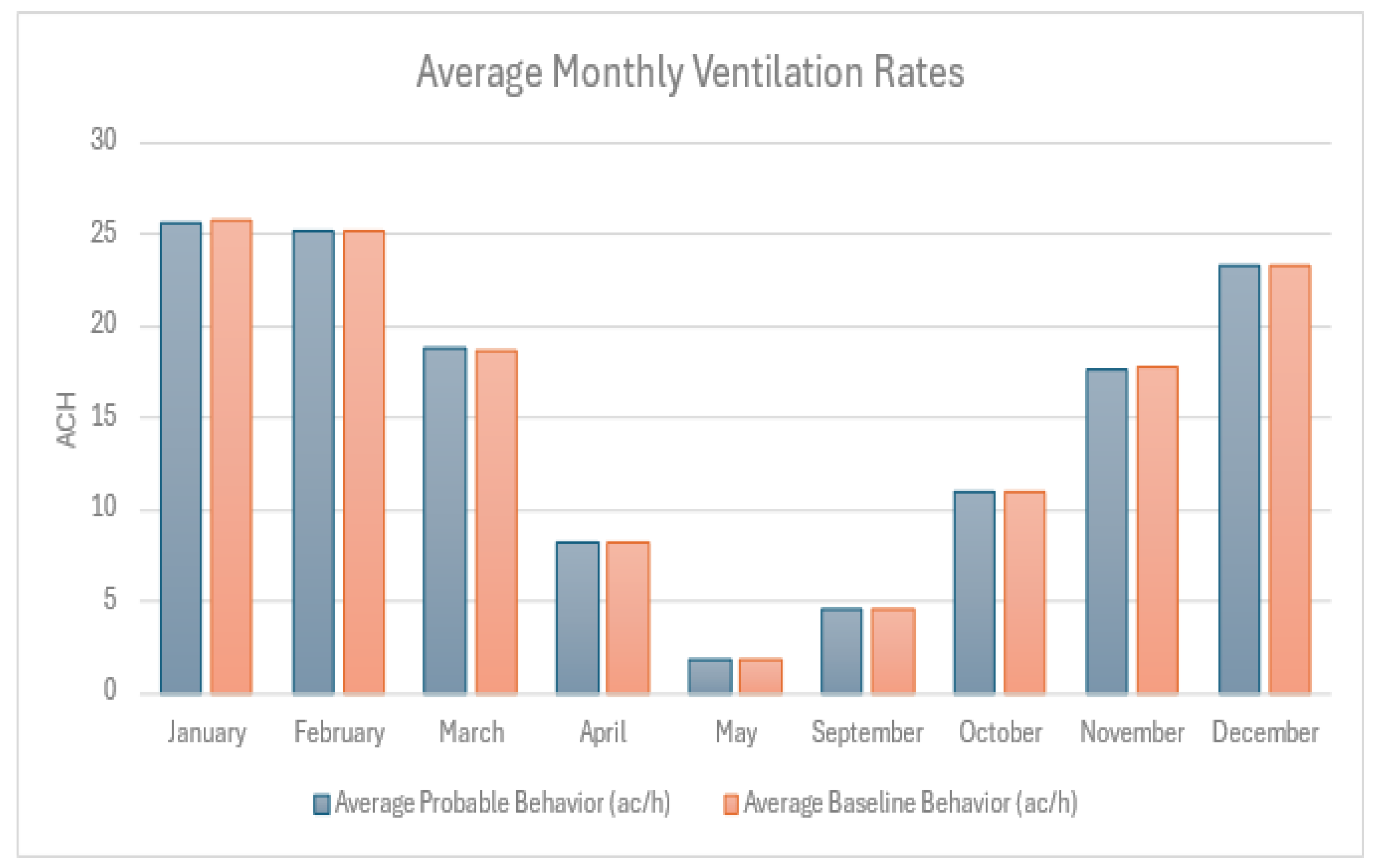

| Jan | 30.07 (5) | 21.76 (9) | 25.75 | 25.70 | -0.2% | 626.69 | 708.39 (5) | 535.21 (9) |

| Feb | 29.64 (5) | 21.46 (9) | 25.20 | 25.22 | +0.1% | 547.62 | 603.69 (5) | 466.66 (9) |

| Mar | 21.86 (5) | 15.92 (9) | 18.61 | 18.89 | +1.5% | 467.46 | 515.69 (5) | 398.63 (9) |

| Apr | 9.62 (5) | 7.00 (9) | 8.16 | 8.18 | +0.2% | 302.59 | 332.61 (5) | 257.57 (9) |

| May | 2.27 (5) | 1.57 (9) | 1.79 | 1.78 | -0.6% | 233.97 | 259.52 (5) | 199.95 (9) |

| Sep | 5.47 (5) | 3.87 (9) | 4.64 | 4.56 | -1.7% | 398.31 | 437.60 (5) | 338.82 (9) |

| Oct | 12.84 (5) | 9.20 (9) | 10.98 | 11.00 | +0.2% | 499.50 | 543.92 (5) | 423.22 (9) |

| Nov | 20.99 (5) | 14.89 (9) | 17.82 | 17.66 | -0.9% | 585.16 | 638.89 (5) | 496.55 (9) |

| Dec | 27.36 (5) | 19.46 (9) | 23.27 | 23.36 | +0.4% | 645.04 | 708.39 (5) | 548.90 (9) |

3.3.2. Scenario B: 4.5 m × 2.6 m

3.3.3. Discussion: Design Implications and Behavioural Insights

3.4. Design Story Four: North-South Window Configuration

3.4.1. Scenario A: 7 m × 2.6 m North and South Walls

3.4.2. Scenario B: 4.5 m × 2.6 m North and South Walls

| Month | Highest NV (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 22.42 (6) | 19.65 (5) | 21.23 | 23.86 | +12.4% | 269.77 | 280.93 (6) | 263.57 (1) |

| Feb | 23.75 (6) | 20.87 (5) | 22.36 | 25.18 | +12.6% | 268.43 | 277.28 (6) | 261.87 (1) |

| Mar | 17.48 (6) | 15.56 (5) | 16.67 | 18.43 | +10.6% | 346.27 | 356.11 (6) | 338.75 (1) |

| Apr | 9.13 (6) | 8.52 (10) | 8.78 | 10.52 | +19.8% | 326.68 | 333.73 (6) | 318.47 (1) |

| May | 1.87 (1) | 1.60 (5) | 1.72 | 2.05 | +19.2% | 338.21 | 344.38 (6) | 329.53 (1) |

| Sep | 4.58 (6) | 4.31 (5) | 4.48 | 5.22 | +16.5% | 337.44 | 345.46 (6) | 329.07 (1) |

| Oct | 8.41 (6) | 7.76 (5) | 8.12 | 9.48 | +16.7% | 309.82 | 318.88 (6) | 302.05 (1) |

| Nov | 10.96 (6) | 9.75 (5) | 10.36 | 11.41 | +10.1% | 266.79 | 277.31 (6) | 260.43 (1) |

| Dec | 16.63 (6) | 14.91 (5) | 15.74 | 17.21 | +9.3% | 274.85 | 287.18 (6) | 268.53 (1) |

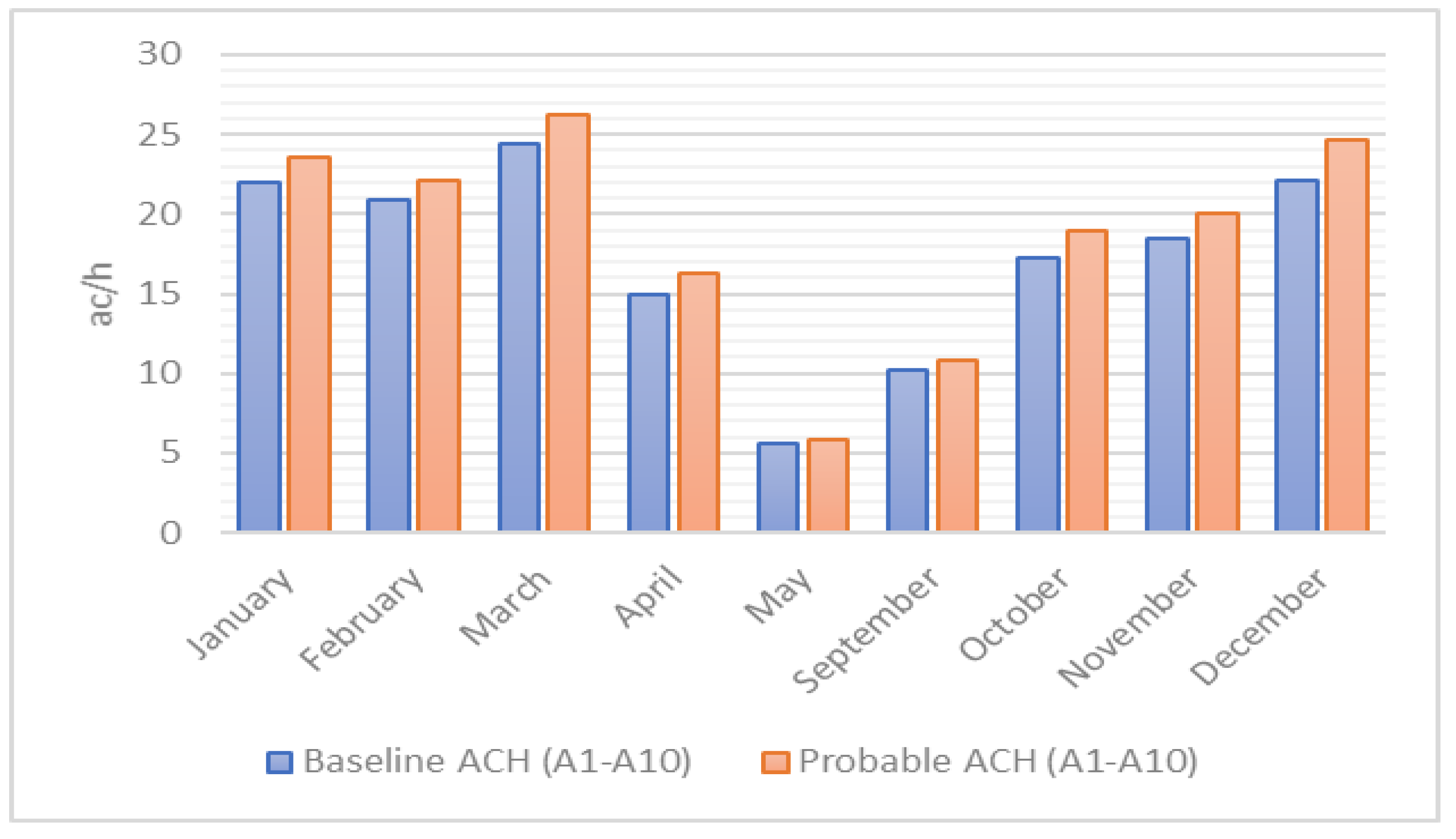

3.5. Design Story 5: North-East Window Configuration

3.5.1. Scenario A: 7 m × 2.6 m North Wall and 4.5 m × 2.6 m East Wall

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 23.81 (March) | 5.36 (May) | 16.22 |

| A2 | 25.39 (March) | 5.89 (May) | 17.32 |

| A3 | 23.86 (March) | 5.39 (May) | 16.25 |

| A4 | 24.09 (March) | 5.38 (May) | 16.37 |

| A5 | 23.66 (March) | 5.30 (May) | 15.95 |

| A6 | 24.08 (March) | 5.38 (May) | 16.29 |

| A7 | 23.73 (March) | 5.38 (May) | 16.07 |

| A8 | 25.18 (March) | 5.87 (May) | 16.92 |

| A9 | 24.06 (March) | 5.43 (May) | 16.24 |

| A10 | 24.73 (March) | 5.82 (May) | 16.58 |

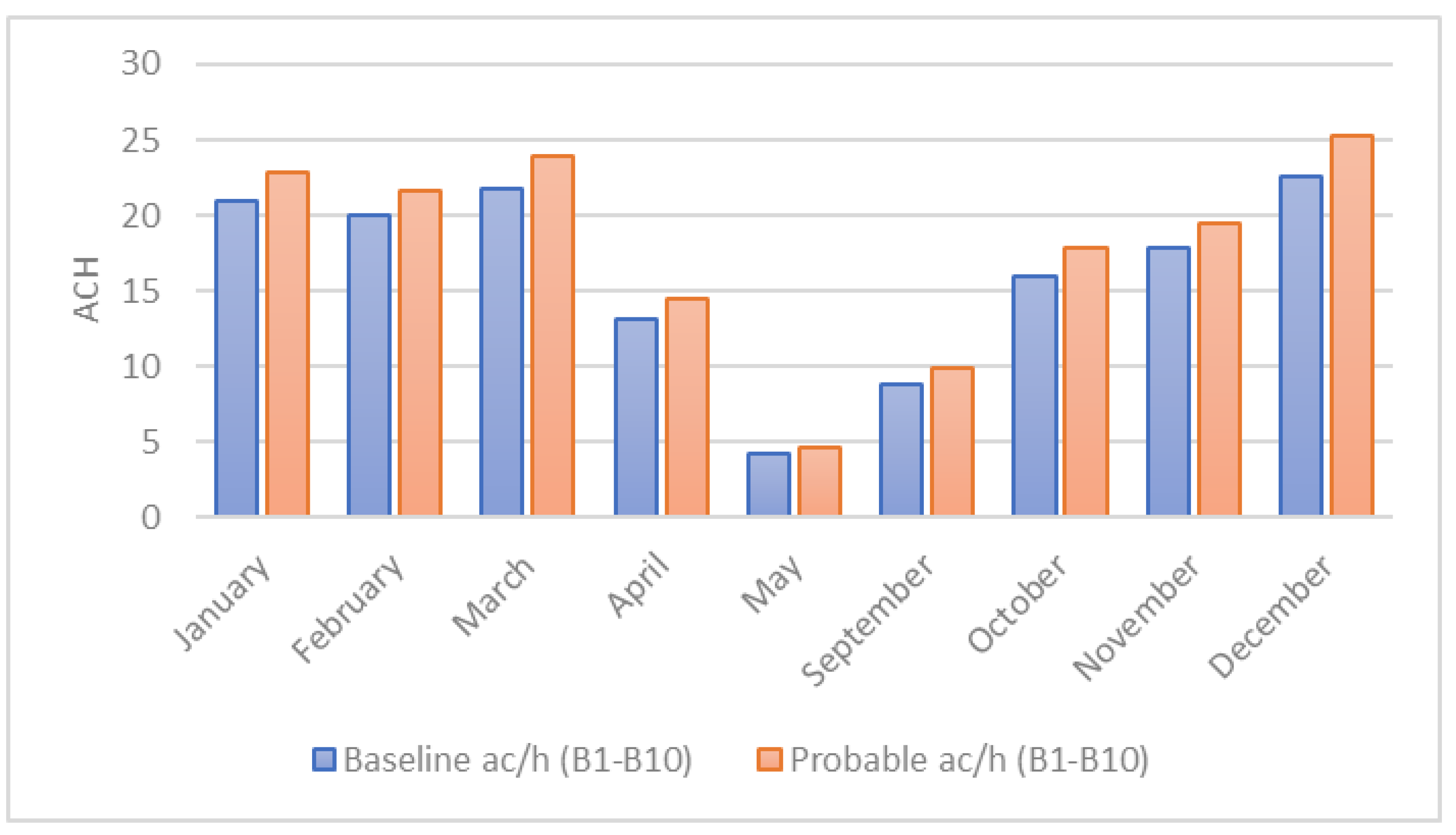

3.5.2. Scenario B: 4.5 m × 2.6 m North Wall and 7 m × 2.6 m East Wall

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 21.32 (5) | 20.34 (7) | 20.89 | 22.80 | +9.1% | 555.42 | 564.86 (1) | 548.82 (9) |

| Feb | 20.42 (3) | 19.66 (7) | 20.02 | 21.61 | +8.0% | 532.91 | 541.37 (1) | 526.73 (9) |

| Mar | 21.87 (3) | 21.43 (7) | 21.70 | 23.91 | +10.2% | 552.50 | 559.62 (1) | 546.51 (9) |

| Apr | 13.22 (3) | 12.87 (7) | 13.09 | 14.52 | +11.0% | 441.47 | 446.34 (1) | 436.76 (9) |

| May | 4.23 (2) | 4.11 (7) | 4.17 | 4.67 | +12.0% | 403.35 | 406.77 (1) | 399.15 (9) |

| Sep | 8.92 (4) | 8.67 (7) | 8.83 | 9.92 | +12.3% | 509.27 | 516.59 (1) | 504.76 (9) |

| Oct | 16.22 (4) | 15.43 (7) | 15.90 | 17.84 | +12.2% | 561.58 | 569.92 (1) | 555.23 (9) |

| Nov | 18.09 (3) | 17.55 (7) | 17.81 | 19.53 | +9.7% | 564.13 | 573.79 (1) | 557.46 (9) |

| Dec | 22.99 (3) | 22.06 (9) | 22.52 | 25.31 | +12.4% | 582.15 | 592.25 (1) | 574.96 (9) |

3.5.3. Discussion: Design Implications and Behavioral Insights

3.5. Broader Applicability and Transferability

3.7. Summary & Guideline

| Orientation | Window Design Strategy | Key Parameters | Behavioral Insight | Simulation Outcome | Final Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Two windows (equal size) | 45% WWR | Frequent opening due to glare-free daylight | High ventilation, low solar gain | ✅ Recommend for daylight + ventilation |

| One large central window | 45% WWR, high placement | Less use due to unreachable height | Medium ventilation, better view | ⚠️ Only if view is priority | |

| South | One large window + two side windows | Total 65% WWR | Overheating during afternoon, limited opening | High solar gain, glare issues | ❌ Not ideal without shading |

| Two medium windows | 45% WWR | Balanced use, easy to open | Moderate ventilation and daylight | ✅ Preferred for comfort | |

| East | Large ceiling height window | 40% WWR | Low opening frequency in morning | Glare issues in early hours | ⚠️ Use only with shading |

| East | Smaller west-facing window | 30% WWR | Opened more in late day | Supports cross ventilation | ✅ Good for morning-evening balance |

| West | One large window | 40% WWR | Often kept shut due to heat | Poor thermal comfort | ❌ Avoid large west-facing glass |

| West | Two smaller splits windows | 45% total WWR | More likely to be opened | Better air flow, lower overheating | ✅ Recommended with shading |

| Orientation | Recommended Window Dimensions | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| North | - Height: 2.0 m - 2.4 m - Width: 1.5 m - 2.0 m - Aspect ratio (H/W): >1.0 (taller than wide) |

- Place operable part within 1.0-1.5 m from floor for easy access - Total WWR: 40-50% - Ideal for maximizing ventilation and daylight with minimal glare |

| East | - Height: 1.8 m - 2.0 m - Width: 2.0 m - 3.0 m - Aspect ratio: <1.0 (wider than tall) |

- Use shading devices e.g., blinds, overhangs to control morning glare - Suitable for capturing morning light and ventilation |

| West | - Height: 1.5 m - 1.8 m - Width: 1.5 m - 2.0 m - Aspect ratio: ~1.0 (square or slightly rectangular) |

- Use external shading or low-E glass to reduce afternoon heat gain - Smaller windows help manage excessive solar exposure |

| South | - Height: 1.8 m - 2.0 m - Width: 1.8 m - 2.5 m - Aspect ratio: ~1.0 (square or slightly rectangular) |

- Provides consistent daylight without excessive heat gain - Suitable for spaces where glare is less of an issue |

4. Limitations and Future Works

5. Conclusion

- Probable Behavior models significantly increased ventilation rates by approximately 5% to over 20% compared to static (Same Behavior) assumptions, highlighting the critical impact of realistic occupant engagement.

- Moderately sized north-facing windows (around 45% WWR) and balanced cross-ventilation designs (e.g., North–South, East–West, North–East) consistently delivered the highest ventilation performance, achieving peak rates around 25–36 ACH in optimal configurations.

- Windows placed within occupant reach (below 1.6 m height) significantly improved usability and thus increased ventilation frequency and effectiveness.

- Large windows placed near ceilings or on west and south orientations resulted in increased solar gain (up to ~700 kWh/month in extreme cases), causing potential overheating and lower window-use frequency.

- Balanced and symmetrical window layouts on the same façade encouraged simultaneous occupant use, enhancing overall ventilation effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

References

- Amasyali, K. , & El-Gohary, N. M. (2018). A review of data-driven building energy consumption prediction studies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 81, 1192-1205.

- Zhan, Sicheng, et al. "Bridging performance gap for existing buildings: The role of calibration and the cascading effect." Building Simulation. Vol. 18. No. 1. Tsinghua University Press, 2025.

- Menezes, A. C. , Cripps, A., Bouchlaghem, D., & Buswell, R. (2012). Predicted vs. actual energy performance of non-domestic buildings. Applied Energy, 97, 355-364.

- de Wilde, P. (2014). The gap between predicted and measured energy performance of buildings: A framework for investigation. Automation in Construction, 41, 40-49.

- van Dronkelaar, C. , Dowson, M., Burman, E., Spataru, C., & Mumovic, D. (2016). A review of the energy performance gap and its underlying causes in non-domestic buildings. Frontiers in Mechanical Engineering, 1, 17.

- Far, Claire, Iftekhar Ahmed, and Jamie Mackee. "Significance of occupant behaviour on the energy performance gap in residential buildings." Architecture 2.2 (2022): 424-433.

- Hong, T. , Taylor-Lange, S. C., D'Oca, S., Yan, D., & Corgnati, S. P. (2016). Advances in research and applications of energy-related occupant behavior in buildings. Energy and Buildings, 116, 694-702.

- Yan, D. , O'Brien, W., Hong. T., Feng, X., Gunay. H. B., Tahmasebi, F., & Mahdavi. A. (2017). Occupant behavior modeling for building performance simulation: Current state and future challenges. Energy and Buildings, 107. 264-278.

- Andersen, R. V., Toftum, J., Andersen, K. K., & Olesen, B. W. (2009). Survey of occupant behavior and control of indoor environment in Danish dwellings. Energy and Buildings, 41(1), 11-16.

- NatHERS Technical Note (Version October 2024) | Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS). (2019). Nathers.gov.au. https://www.nathers.gov.au/publications/nathers-technical-note.

- Zhang, Yan. "Occupant behavior and its impact on energy consumption of urban residential buildings." (2021).

- Mylonas, Angelos, Aris Tsangrassoulis, and Jordi Pascual. "Modelling occupant behaviour in residential buildings: A systematic literature review." Building and Environment (2024): 111959.

- D'Oca, S. , Chen, C. F., Hong, T., & Belafi, Z. (2017). Synthesizing building physics with social psychology: An interdisciplinary framework for context and occupant behavior in office buildings. Energy Research & Social Science, 34, 240-251.

- Schweiker, M., Fuchs, X., Becker, S., & Wagner, A. (2020). Occupant behavior relation to the connected openings of adjacent spaces in a field study. Building and Environment, 173, 106749.

- O'Brien, W. , & Gunay, H. B. (2014). The contextual factors contributing to occupants' adaptive comfort behaviors in offices: A review and proposed modeling framework. Building and Environment, 77, 77-87.

- Reinhart, C. F. , & Voss, K. (2003). Monitoring manual control of electric lighting and blinds. Lighting Research & Technology, 35(3), 243-260.

- Fabi, V. , Andersen, R. V., Corgnati, S. P., & Olesen, B. W. (2012). Occupants' window opening behaviour: A literature review of factors influencing occupant behaviour and models. Building and Environment, 58, 188-198.

- Haldi, F. Haldi, F., & Robinson, D. (2010). On the unification of thermal perception and adaptive actions. Building and Environment, 45(11), 2440-2457.

- Gunay, H. B., O'Brien, W., & Beausoleil-Morrison, I. (2016). Implementation and comparison of existing occupant behavior models in EnergyPlus. Journal of Building Performance Simulation, 9(6), 567-589.

- Pourtangestani, M. , Izadyar, N., Jamei, E., & Vrcelj, Z. (2024). Linking occupant behavior and window design through post-occupancy evaluation: Enhancing natural ventilation and indoor air quality. Buildings, 14(6), 1638. [CrossRef]

- Arethusa, M. T., Kubota, T., Angung, M., Sri, N., Antaryama, I., & Tomoko, U. (2014). Factors influencing window opening behaviour in apartments of Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 30th International PLEA Conference. Sustainable Habitat for Developing Societies: Choosing the Way Forward (pp. 239-246), Volume 1.

- Chelliah, N. S. , Gnanasambandam, N. S., & Tadepalli, S. (2025). Influence of window design and environmental variables on the window opening behavior of occupants and energy consumption in residential buildings. Transactions on Energy Systems and Engineering Applications, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- ΙΕA. (2021). The role of buildings in the post-COVID recovery. International Energy Agency.

- Rouleau, J. , & Gosselin, L. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on building energy consumption and GHG emissions: The case of Québec, Canada. Energy and Buildings, 240, 110924.

- Ferreira, A. , & Barros, N. (2022). COVID-19 and Lockdown: The Potential Impact of Residential Indoor Air Quality on the Health of Teleworkers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6079. [CrossRef]

- Heiselberg, P., Svidt, K., & Nielsen, P. V. (2001). Characteristics of airflow from open windows. Building and Environment, 36(7), 859-869.

- Qi, H. , Sha, D., & Zhang, Y. (2020). A review of high-rise ventilation for energy efficiency and safety. Sustainable Cities and Society, 52, 101841.

- Yang, Q. , Liu, M., Shu, C., Mmereki, D., Uzzal Hossain, Md., & Zhan, X. (2015). Impact Analysis of Window-Wall Ratio on Heating and Cooling Energy Consumption of Residential Buildings in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone in China. Journal of Engineering, 2015, 1-17.

- Goia, F. (2016). Search for the optimal window-to-wall ratio in office buildings in different European climates and the implications on total energy-saving potential. Solar Energy, 132, 467-495.

- Song, G., Ai, Z., Liu, Z., & Zhang, G. (2022). A systematic literature review on smart and personalized ventilation using CO2 concentration monitoring and control. Energy Reports, 8, 6504-6519.

- Bramiana, C. N. , Aminuddin, A. M. R., Ismail, M. A., Widiastuti, R., & Pramesti, P. L. (2023). The Effect of Window Placement on Natural Ventilation Capability in a Jakarta High-Rise Building Unit. Buildings, 13(5), 1141.

- U.S. Department of Energy. Natural ventilation. Energy Saver https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/natural-ventilation.

- Davenport, A. G. , & Wilson, D. J. (1996). Wind engineering for natural ventilation design. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, 65(1-3), 1-12.

- Sacht, H., & Lukiantchuki, M. A. (2017). Windows Size and the Performance of Natural Ventilation. Procedia Engineering, 196, 972-979.

- Xu, P. , Shen, Y., & Zhang, X. (2015). Energy performance optimization of windows in hot climates: A parametric study. Energy and Buildings, 103, 15-25.

- Schulze, T., & Eicker, U. (2013). Controlled natural ventilation for energy efficient buildings. Energy and Buildings, 56, 221-232.

- Vanhoutteghem, L., Skarning, G. C. J., Hviid, C. A., & Svendsen, S. (2015). Impact of window design on energy performance in residential buildings. Energy and Buildings, 92, 141-151.

- Roetzel, A. , Tsangrassoulis, A., Dietrich, U., & Busching, S. (2010). On the influence of window design on energy efficiency in different climates. Building and Environment, 45(5), 1263-1275.

- Feng, X., Yan, D., & Wang, C. (2015). Simulation of occupancy in buildings. Energy and Buildings, 87, 348-360.

- D'Oca, S., & Hong, T. (2015). Occupancy schedules learning process through a data mining framework. Energy and Buildings, 88, 395-408.

- Langevin, J. , Wen, J., & Gurian, P. L. (2015). Simulating the human-building interaction: Development and validation of an agent-based model of office occupant behaviors. Building and Environment, 88, 27-45.

- Gaetani, I., Hoes, P. J., & Hensen, J. L. M. (2016). Estimating the influence of occupant behavior on building heating and cooling energy in one simulation run. Applied Energy, 216, 372-383.

- Wang, Y. , Wang, X., & Yu, S. (2023). Understanding the role of occupant behavior in residential building energy consumption: A review of recent advances. Energy and Buildings, 301, 113938.

- Li, C. , Skitmore, M., & He, T. (2022). The post-occupancy dilemma in green-rated buildings: A performance gap analysis. Journal of Green Building, 17(3), 259-278.

- Gram-Hanssen, K. , & Georg, S. (2022). Energy performance gaps: Promises, people, and practices. Buildings and Cities, 3(1), 51-64.

- Rupp, R. F. , Fornari, R. M., & Ghisi, E. (2022). Adaptive thermal comfort models for naturally ventilated buildings: A critical review and future directions. Building and Environment, 218, 109149.

- Wu, Z., Li, N., Wargocki, P., Peng, J., Li, J., & Cui, H. (2019). Adaptive thermal comfort in naturally ventilated dormitory buildings in Changsha, China. Energy and Buildings, 201, 109400.

- Elsayed, M. , Pelsmakers, S., & Pistore, L. (2023). Post-occupancy evaluation in residential buildings: A systematic literature review of current practices in the EU. Building and Environment, 234, 110755.

- Anderson, K., & Lee, S. H. (2016). An empirically grounded model for simulating normative energy use feedback interventions. Applied Energy, 173, 272-282.

- Artan, D. , Ergen, E., Kula, B., & Guven, G. (2022). Rateworkspace: BIM integrated post-occupancy evaluation system for office buildings. Journal of Information Technology in Construction, 27, 441-485. [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, A. , Tsangrassoulis, A., & Pascual, J. (2024). Modelling occupant behaviour in residential buildings: A systematic literature review. Building and Environment, 265, 111959.

- Heiselberg, P., & Bjørn, E. (2002). Experimental investigation of airflow and temperature distribution in a room with natural ventilation. International Journal of Ventilation, 1(1), 55-68.

- Saadi, S. , Hayati, A., & Salmanzadeh, M. (2021). Optimization of Window-to-Wall Ratio for Buildings Located in Different Climates: An IDA-Indoor Climate and Energy Simulation Study. Energies, 14(7), 1974.

- Veillette, D. , Rouleau, J., & Gosselin, L. (2021). Impact of Window-to-Wall Ratio on Heating Demand and Thermal Comfort When Considering a Variety of Occupant Behavior Profiles. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 3.

- Ali, D. M. T. E. , Motuzienė, V., & Džiugaitė-Tumėnienė, R. (2023). Al-driven innovations in building energy management systems: A review of potential applications and energy savings. Energies, 17(17), 4277.

- Dai, X. , Liu, J., & Zhang, X. (2020). A review of studies applying machine learning models to predict occupancy and window-opening behaviours in smart buildings. Energy and Buildings, 223, 110159.

- Cao, Q. , Li, X., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Predictive analytics for occupant behavior in smart buildings: A review of machine learning techniques. Building and Environment, 245, 110892.

- Lu, W. , Zhang, L., & Liu, Y. (2024). Evaluation of Urban Complex Utilization Based on AHP and MCDM Analysis: A Case Study of China. Buildings, 14(7), 2179.

- Das, P. , Chalabi, Z., Jones, B., Milner, I., Shrubsole, C., Davies, M., & Wilkinson, P. (2016). Multi-objective methods for determining optimal ventilation rates in dwellings. Building and Environment, 109, 170-181.

- Jiang, Y. , Li, N., Yongga, A., & Yan, W. (2022). Short-term effects of natural view and daylight from windows on thermal perception, health, and energy-saving potential. Building and Environment, 219, 109146.

- Aries, M. B. C. , Aarts, M. P. J., & van Hoof, J. (2015). Daylight and health: A review of the evidence and consequences for the built environment. Lighting Research & Technology, 47(1), 6-27.

- Tomrukcu, G. , & Ashrafian, T. (2024). Climate-resilient building energy efficiency retrofit: Evaluating climate change impacts on residential buildings. Energy and Buildings, 316, 114315.

- Mesloub, A. , Alnaim, M. M., Albagawi, G., Alsolami, B. M., Mahboub, M. S., Tsangrassoulis, A., & Doulos, L. T. (2023). The visual comfort, economic feasibility, and overall energy consumption of tubular daylighting device system configurations in deep plan office buildings in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Building Engineering, 68, 106100.

- Burman, E., Mumovic, D., & Kimpian, J. (2014). Towards measurement and verification of energy performance under the framework of the European directive for energy performance of buildings. Energy, 77, 153-163.

- Delzendeh, E. , Wu, S., Lee, A., & Zhou, Y. (2017). The impact of occupants' behaviours on building energy analysis: A research review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 80, 1061-1071.

- Schmidt, M. , Crawford, R. H., & Warren-Myers, G. (2020). Quantifying Australia's life cycle greenhouse gas emissions for new homes. Energy and Buildings, 190, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Australian Building Codes Board. (2022). National Construction Code 2022. Canberra: ABCB.

- Dalton, T. (2011). Australian suburban house building: Industry organisation, practices, and constraints. AHURI Posi-tioning Paper No. 143.

- Australian Institute of Refrigeration, Air Conditioning and Heating (AIRAH). (2019). The Australian HVAC&R Industry Guide. Retrieved from https://www.airah.org.

- Climate statistics for Australian locations: Melbourne monthly climate statistics. Retrieved from: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_086071.

- Xu, X. , Yu, C., & Li, H. (2020). Energy performance of window systems in buildings: A review. Energy and Buildings, 214, 109842.

| Parameter Type | Fixed Inputs | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Building Dimensions | Typical living room, ceiling height 2.4 m | Living room with wider and smaller wall dimensions, which match standard dimensions for Melbourne homes |

| Wall Construction | Brick veneer, air cavity, reflective sarking, plasterboard | Standard local wall construction |

| Window Specifications | Double-glazed low-E glass, thermally broken aluminium frames | U-value: 2.8–3.2 W/m²·K; SHGC: 0.40–0.50 |

| Weather Data | Hourly temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation | Melbourne climate, typical meteorological year |

| Design Story | Orientation | Configuration | WWR | Configuration Rational |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Story 1 | North | Dual window | 45% | -Directly responds to the strongest orientation preferences. -Side-by-side configurations showed high occupant interaction, particularly for achieving fresh air. -Size 45% WWR represents the occupant's desire for ample daylight/view. |

| Story 2 | East-West | Single window | E 40% W 30% |

- Large east-facing window extending towards the ceiling for optimal light, and takes advantage of morning light and passive heating. - The west window helps manage afternoon heat gain. - Providing cross-ventilation. |

| Story 3 | South | Dual window | 30% Each | -Investigate occupant interaction with an orientation known for consistent, diffuse daylight and minimal direct solar heat gain/glare. -Side-by-side configuration, which has high occupant interaction for ventilation and general use. -Moderate 60% WWR, provides substantial natural light, aligning with occupant preference for light/view. |

| Story 4 |

North & South | Dual North Single South |

S 40% N 25% Each |

-Preferred North orientation for potential winter solar gain and ventilation. -The large, ceiling-height south-facing dimension enhances daylight penetration -Design maximizes cross-ventilation potential by utilising both north and south orientations. |

| Story 5 | North &East | Single North Dual South |

N 40% E 25% Each |

Combination of preferred orientations. -The North Window incorporates the strongly preferred North orientation for ventilation and stable daylight. -East Windows: Leverage the benefits of the East morning light |

| Design Story | Orientation | Scenario A | Scenario B | SB Rationale | PB Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Story 1 | North |  |

|

Regular morning and evening openings | On wider walls, it increases morning openings for wind; on smaller walls, less frequent due to limited airflow. |

| Story 2 | East and West |  |

|

Morning openings (east), evening openings (west) | On wider walls, boosts east morning openings for light; on smaller walls, reduces west midday openings for heat control. |

| Story 3 | South |  |

|

Less frequent openings due to limited wind exposure. | On wider walls, reduce midday openings to manage heat; on smaller walls, further limited due to weaker ventilation potential. |

| Story 4 | North and South |  |

|

Frequent openings for cross-ventilation, especially mornings. | On wider walls, enhances morning cross-ventilation; on smaller walls, reduces south midday openings for heat control. |

| Story 5 | North-East |  |

|

East morning openings for light, north for steady ventilation. | On wider walls, boosts east morning openings; on smaller walls, adjusts north for consistent airflow throughout the day. |

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.67 (March) | 1.95 (May) | 3.47 |

| 2 | 4.52 (March) | 1.89 (May) | 3.36 |

| 3 | 4.40 (March) | 1.89 (May) | 3.31 |

| 4 | 4.31 (March) | 1.86 (May) | 3.23 |

| 5 | 3.95 (March) | 1.72 (May) | 2.97 |

| 6 | 4.06 (March) | 1.78 (May) | 3.06 |

| 7 | 4.06 (March) | 1.77 (May) | 3.06 |

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 4.12 (1) | 3.49 (5) | 3.80 | 4.23 | +11.2% | 228.15 | 238.93 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| Feb | 4.63 (1) | 3.90 (5) | 4.24 | 4.72 | +11.3% | 235.29 | 275.27 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| Mar | 4.67 (1) | 3.95 (5) | 4.28 | 4.83 | +12.7% | 294.62 | 408.14 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| Apr | 3.80 (1) | 3.27 (5) | 3.52 | 3.86 | +9.6% | 291.09 | 404.11 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| May | 1.95 (1) | 1.72 (5) | 1.84 | 2.05 | +11.3% | 298.98 | 436.76 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| Sep | 2.41 (1) | 2.16 (5) | 2.29 | 2.51 | +9.5% | 237.18 | 404.32 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| Oct | 2.92 (1) | 2.55 (5) | 2.74 | 2.97 | +8.7% | 246.09 | 336.10 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| Nov | 3.00 (1) | 2.60 (5) | 2.78 | 3.08 | +10.8% | 228.13 | 242.85 (4) | 219.66 (1) |

| Dec | 3.67 (1) | 3.13 (5) | 3.37 | 3.70 | +9.6% | 223.04 | 223.81 (4) | 219.52 (2) |

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 2.86 (February) | 1.00 (May) | 2.09 |

| 10 | 2.67 (February) | 0.96 (May) | 1.97 |

| 11 | 2.58 (February) | 0.95 (May) | 1.92 |

| 12 | 2.44 (February) | 0.92 (May) | 1.84 |

| 13 | 2.79 (February) | 1.00 (May) | 2.06 |

| 14 | 2.52 (February) | 0.95 (May) | 1.89 |

| 15 | 2.52 (February) | 0.94 (May) | 1.89 |

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 2.65 (9) | 2.28 (12) | 2.44 | 2.70 | +10.6% | 148.05 | 149.23 (15) | 146.07 (10) |

| Feb | 2.86 (9) | 2.44 (12) | 2.63 | 2.90 | +10.3% | 171.27 | 171.63 (15) | 168.05 (10) |

| Mar | 2.75 (9) | 2.37 (12) | 2.53 | 2.74 | +8.1% | 251.70 | 254.26 (15) | 248.99 (10) |

| Apr | 2.14 (9) | 1.91 (12) | 2.02 | 2.15 | +6.4% | 249.46 | 251.69 (15) | 246.49 (10) |

| May | 1.00 (9) | 0.92 (12) | 0.96 | 1.01 | +5.1% | 269.41 | 271.97 (15) | 266.36 (10) |

| Sep | 1.41 (9) | 1.29 (12) | 1.33 | 1.40 | +5.2% | 249.51 | 251.86 (15) | 246.65 (10) |

| Oct | 1.70 (9) | 1.51 (12) | 1.60 | 1.69 | +5.5% | 207.85 | 209.49 (15) | 205.12 (10) |

| Nov | 1.92 (9) | 1.70 (12) | 1.80 | 1.95 | +8.6% | 150.15 | 151.62 (15) | 148.42 (10) |

| Dec | 2.40 (9) | 2.10 (12) | 2.23 | 2.43 | +9.0% | 148.62 | 149.94 (15) | 136.96 (10) |

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) | Lowest (ACH) | Average (ACH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26.83 (January) | 1.81 (May) | 13.83 |

| 2 | 26.82 (January) | 1.79 (May) | 13.79 |

| 3 | 26.74 (January) | 1.79 (May) | 13.77 |

| 4 | 26.58 (January) | 1.73 (May) | 13.54 |

| 5 | 27.22 (January) | 1.80 (May) | 14.02 |

| 6 | 25.40 (January) | 1.65 (May) | 12.70 |

| 7 | 26.44 (January) | 1.74 (May) | 13.45 |

| 8 | 26.31 (January) | 1.74 (May) | 13.38 |

| 9 | 26.46 (January) | 1.77 (May) | 13.43 |

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) (Sep–May) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 15.61 (February) | 0.88 (May) | 8.92 |

| 11 | 15.59 (February) | 0.87 (May) | 8.90 |

| 12 | 16.63 (February) | 0.88 (May) | 8.94 |

| 13 | 15.62 (February) | 0.88 (May) | 8.93 |

| 14 | 15.63 (February) | 0.85 (May) | 8.94 |

| 15 | 15.61 (February) | 0.88 (May) | 8.92 |

| 16 | 15.60 (February) | 0.87 (May) | 8.91 |

| 17 | 16.18 (February) | 0.88 (May) | 8.92 |

| 18 | 15.62 (February) | 0.88 (May) | 8.93 |

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 16.47 (12) | 15.95 (17) | 13.82 | 13.47 | -2.5% | 369.65 | 424.69 (3) | 334.32 (5) |

| Feb | 16.63 (12) | 16.18 (17) | 13.91 | 13.74 | -1.2% | 322.39 | 370.33 (3) | 291.50 (5) |

| Mar | 11.89 (12) | 11.49 (17) | 10.17 | 10.11 | -0.6% | 275.41 | 316.28 (3) | 249.11 (5) |

| Apr | 4.76 (12) | 4.59 (17) | 4.09 | 3.92 | -4.2% | 178.04 | 204.54 (3) | 161.06 (5) |

| May | 0.88 (10) | 0.88 (17) | 0.88 | 0.85 | -3.4% | 138.41 | 158.99 (3) | 125.21 (5) |

| Sep | 2.99 (12) | 2.89 (17) | 2.57 | 2.41 | -6.2% | 234.12 | 268.99 (3) | 211.78 (5) |

| Oct | 6.86 (12) | 6.63 (17) | 5.90 | 5.68 | -3.7% | 292.26 | 335.83 (3) | 264.34 (5) |

| Nov | 9.98 (12) | 9.65 (17) | 8.56 | 8.25 | -3.6% | 342.86 | 393.87 (3) | 309.99 (5) |

| Dec | 14.25 (12) | 13.76 (17) | 12.20 | 11.75 | -3.7% | 378.88 | 435.32 (3) | 342.72 (5) |

| Configurations | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 36.24 (February) | 3.38 (May) | 21.48 |

| A2 | 35.95 (February) | 3.33 (May) | 21.21 |

| A3 | 36.18 (February) | 3.35 (May) | 21.56 |

| A4 | 36.05 (February) | 3.33 (May) | 21.33 |

| A5 | 35.82 (February) | 3.30 (May) | 21.01 |

| A6 | 35.92 (February) | 3.33 (May) | 21.14 |

| A7 | 35.93 (February) | 3.36 (May) | 21.14 |

| A8 | 36.10 (February) | 3.35 (May) | 21.36 |

| A9 | 35.76 (February) | 3.34 (May) | 21.07 |

| A10 | 35.75 (February) | 3.32 (May) | 20.93 |

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

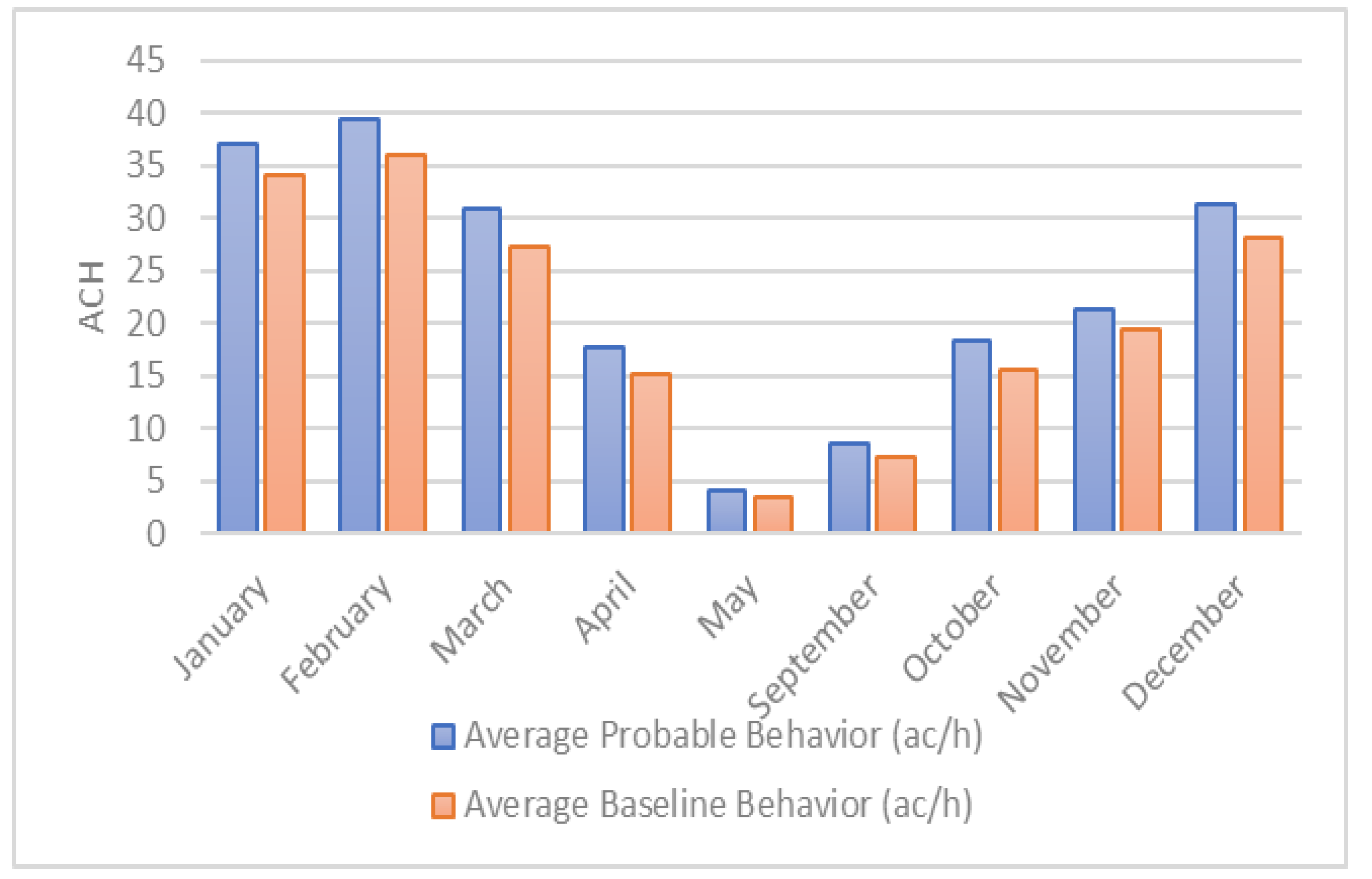

| Jan | 35.90 (1) | 35.75 (10) | 34.04 | 37.00 | +8.7% | 423.94 | 427.89 (3) | 420.58 (10) |

| Feb | 36.24 (1) | 35.75 (10) | 35.97 | 39.41 | +9.6% | 421.31 | 426.44 (3) | 418.49 (10) |

| Mar | 25.60 (1) | 25.40 (10) | 27.31 | 31.00 | +13.5% | 547.37 | 553.22 (3) | 541.82 (10) |

| Apr | 10.25 (1) | 10.15 (10) | 15.09 | 17.71 | +17.4% | 515.99 | 521.83 (3) | 510.71 (10) |

| May | 3.38 (1) | 3.32 (10) | 3.34 | 4.06 | +21.6% | 534.33 | 541.11 (3) | 529.02 (10) |

| Sep | 8.55 (1) | 8.45 (10) | 7.29 | 8.64 | +18.5% | 532.32 | 538.21 (3) | 526.98 (10) |

| Oct | 15.35 (1) | 15.25 (10) | 15.63 | 18.28 | +16.9% | 487.98 | 493.01 (3) | 483.56 (10) |

| Nov | 22.50 (1) | 22.30 (10) | 19.39 | 21.38 | +10.3% | 419.25 | 423.27 (3) | 415.71 (10) |

| Dec | 30.20 (1) | 30.00 (10) | 28.22 | 31.37 | +7.6% | 431.23 | 434.96 (3) | 428.02 (10) |

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) (Sep–May) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 21.41 (January) | 1.87 (May) | 11.22 |

| A2 | 22.58 (February) | 1.63 (May) | 11.45 |

| A3 | 22.30 (February) | 1.64 (May) | 11.05 |

| A4 | 22.44 (February) | 1.72 (May) | 11.33 |

| A5 | 20.87 (February) | 1.60 (May) | 10.47 |

| A6 | 23.75 (February) | 1.77 (May) | 12.09 |

| A7 | 22.12 (February) | 1.64 (May) | 10.88 |

| A8 | 22.57 (February) | 1.75 (May) | 11.28 |

| A9 | 22.26 (February) | 1.66 (May) | 11.11 |

| Month | Highest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Lowest NV Probable (ACH) (Config.) | Avg. NV Baseline (ACH) | Avg. NV Probable (ACH) | % Change | Avg. Solar Gain (kWh) | Peak Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) | Lowest Solar Gain (kWh) (Config.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

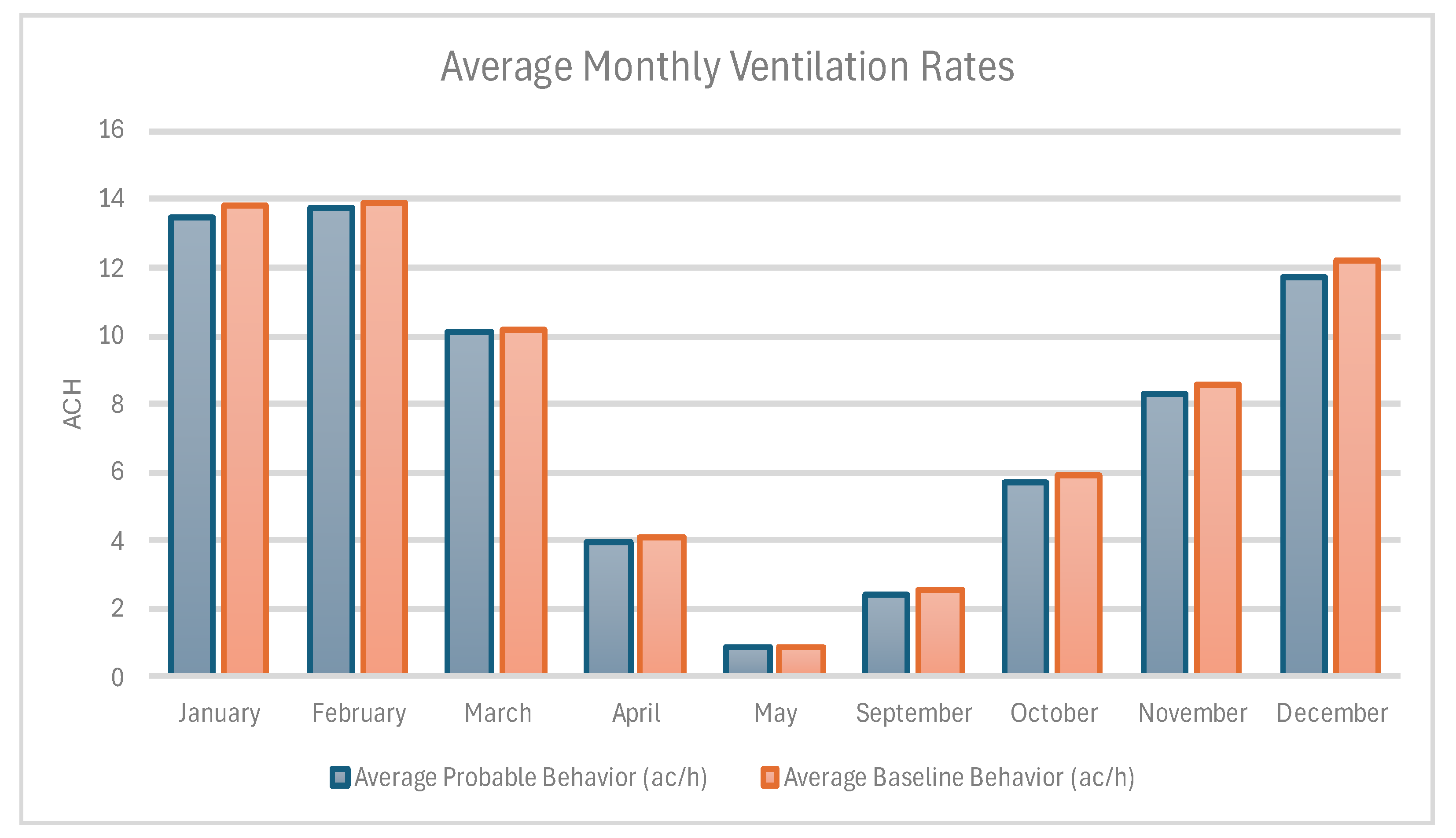

| Jan | 22.72 (2) | 21.29 (5) | 22.00 | 23.57 | +7.1% | 485.17 | 502.49 (2) | 472.70 (5) |

| Feb | 21.77 (2) | 20.38 (5) | 20.88 | 22.05 | +5.6% | 491.50 | 510.64 (2) | 479.15 (5) |

| Mar | 25.39 (2) | 23.66 (5) | 24.36 | 26.18 | +7.5% | 578.86 | 605.23 (2) | 564.66 (5) |

| Apr | 15.63 (2) | 14.42 (5) | 14.90 | 16.28 | +9.3% | 506.61 | 531.74 (2) | 494.55 (5) |

| May | 5.89 (2) | 5.30 (5) | 5.55 | 5.86 | +5.6% | 501.00 | 527.52 (2) | 488.48 (5) |

| Sep | 10.63 (2,10) | 9.93 (5) | 10.23 | 10.79 | +5.5% | 548.05 | 575.75 (2) | 536.79 (5) |

| Oct | 17.83 (2,8) | 16.58 (5) | 17.24 | 18.89 | +9.6% | 543.71 | 566.28 (2) | 530.11 (5) |

| Nov | 19.19 (2) | 18.04 (7) | 18.50 | 20.05 | +8.4% | 492.50 | 510.21 (2) | 479.97 (5) |

| Dec | 23.01 (2) | 21.00 (5) | 22.16 | 24.61 | +11.1% | 493.05 | 509.82 (2) | 480.14 (5) |

| Configuration | Peak (ACH) (Month) | Lowest (ACH) (Month) | Average (ACH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20.62 (January) | 4.18 (May) | 15.47 |

| 2 | 20.92 (January) | 4.23 (May) | 15.56 |

| 3 | 21.87 (March) | 4.20 (May) | 15.99 |

| 4 | 21.73 (March) | 4.14 (May) | 15.85 |

| 5 | 22.94 (December) | 4.12 (May) | 15.93 |

| 6 | 20.87 (January) | 4.21 (May) | 15.48 |

| 7 | 21.43 (March) | 4.11 (May) | 15.32 |

| 8 | 20.98 (January) | 4.19 (May) | 15.54 |

| 9 | 20.47 (January) | 4.13 (May) | 15.41 |

| 10 | 20.80 (January) | 4.19 (May) | 15.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).