Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (A)

- Studying the overall effect on building energy performance of different factors such as building characteristics, weather condition, and building’s orientation. For example, [14] assessed the effect of orientation on energy consumption of a small building by Building Information Modeling (BIM);

- (B)

- Studying on the energy performance of building components individually, such as wall, roof, windows, control system, HVAC system, and insulation; and

- (C)

- A synthesis of two approaches above, in which components of the building are studied with considering the features of the buildings.

2. Materials and Methods

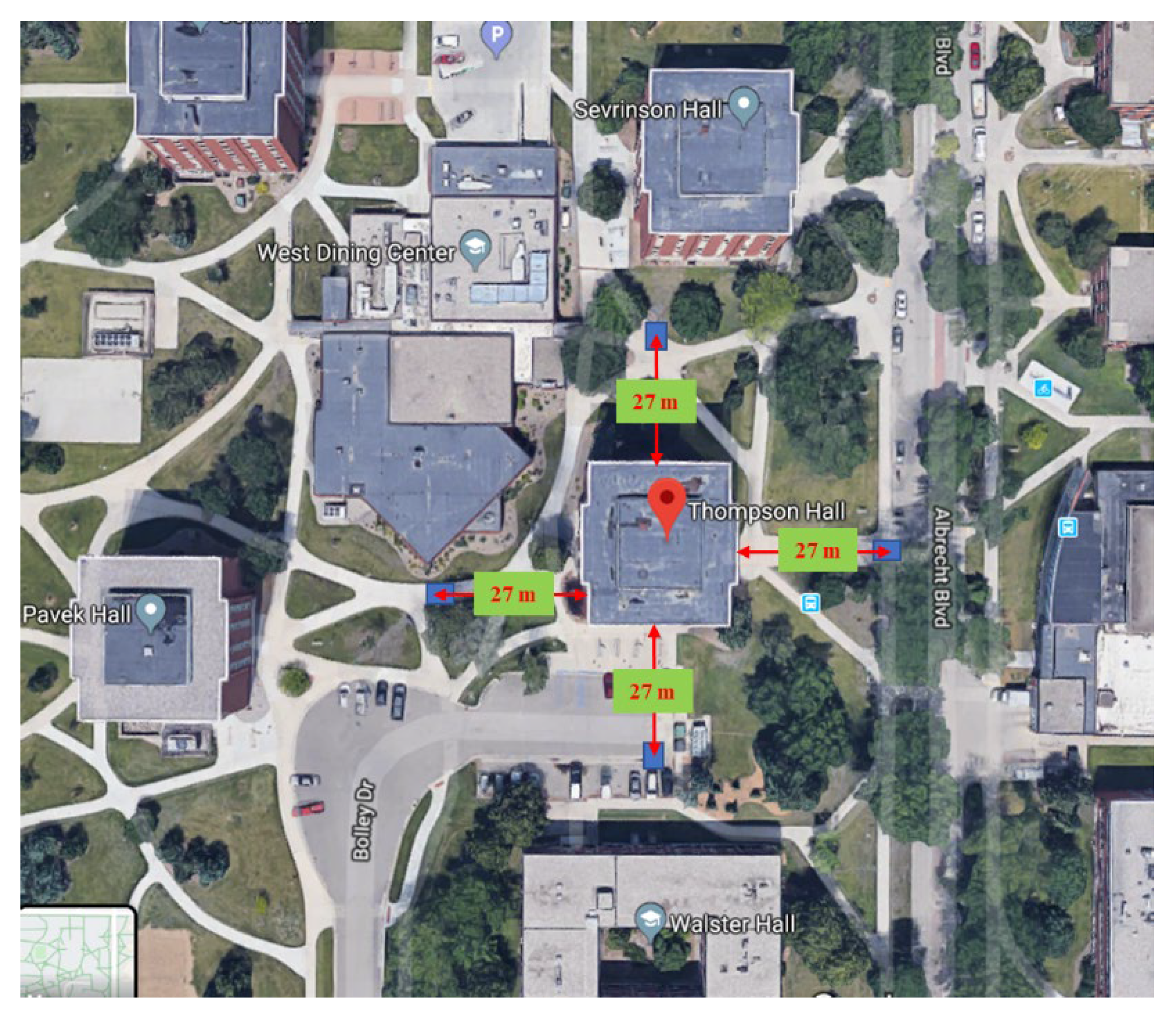

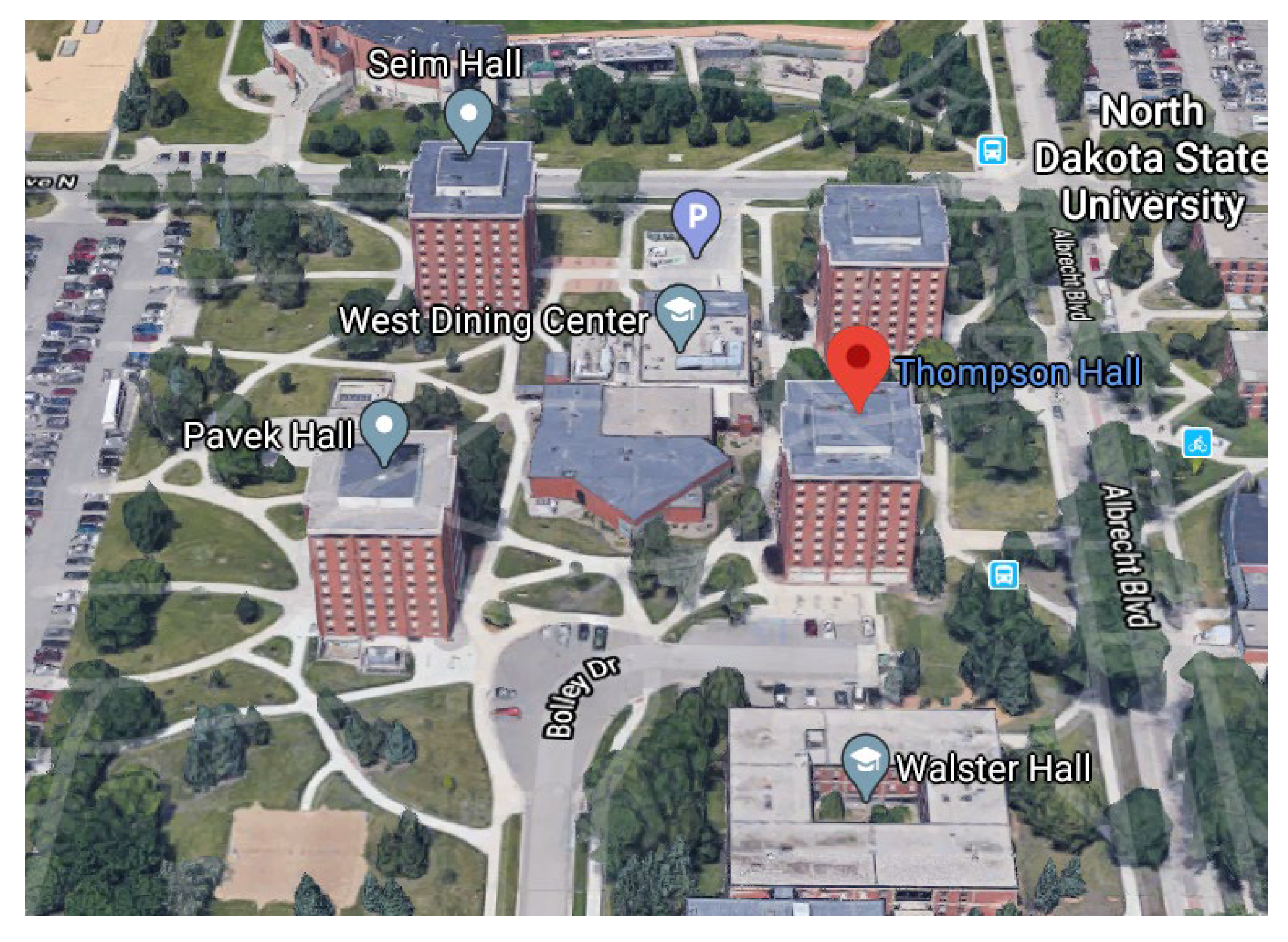

2.1. Study Site

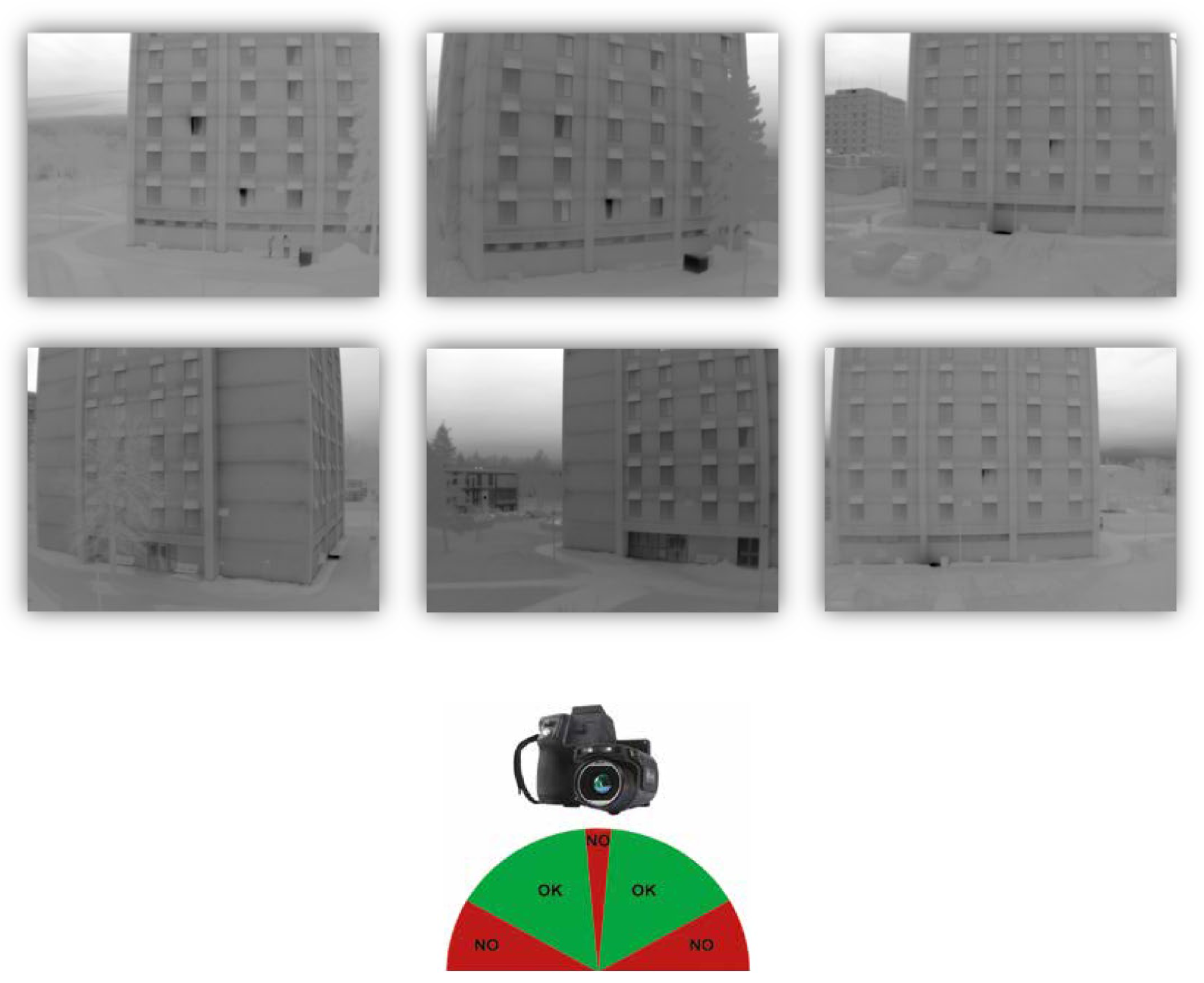

2.2. Measuring Equipment

- ICI infrared camera with a spectral sensitivity of 7 μm to 14 μm and accuracy of ±1 ℃ (Table 2).

- A measuring tape to measure the camera-object distance,

- 2” PVC pipe to hold the board in each image, and

- A 9 m (30 ft) pole to attach the camera and raise it to the desired height.

| Characteristics | Description |

|---|---|

| Name | ICI 9640 |

| Detector Array | UFPA (VOx) |

| Pixel Pitch | 17 μm |

| Pixel Resolution | 640x480 |

| Spectral Band | 7 μm to 14 μm |

| Thermal Sensitivity (NETD) | < 0.02 °C at 30 °C (20 mK) |

| Frame Rate | 30 Hz P-Series |

| Dynamic Range | 14-bit |

| Temperature Range | -40 °C to 140 °C |

| Operation Range | -40 °C to 80 °C |

| Storage Range | -40 °C to 70 °C |

| Accuracy | ± 1 °C |

| Pixel Operability | > 99 %75 G Shock / 4 G Vibration |

| Dimensions (without lens) | 34 x 30 x 34 mm (H x W x D ± .5 mm) |

| Power | < 1 W |

| Weight (without lens) | 37 g |

| USB 2.0 for Power & DataBuilt-in ShutterAluminum Enclosure |

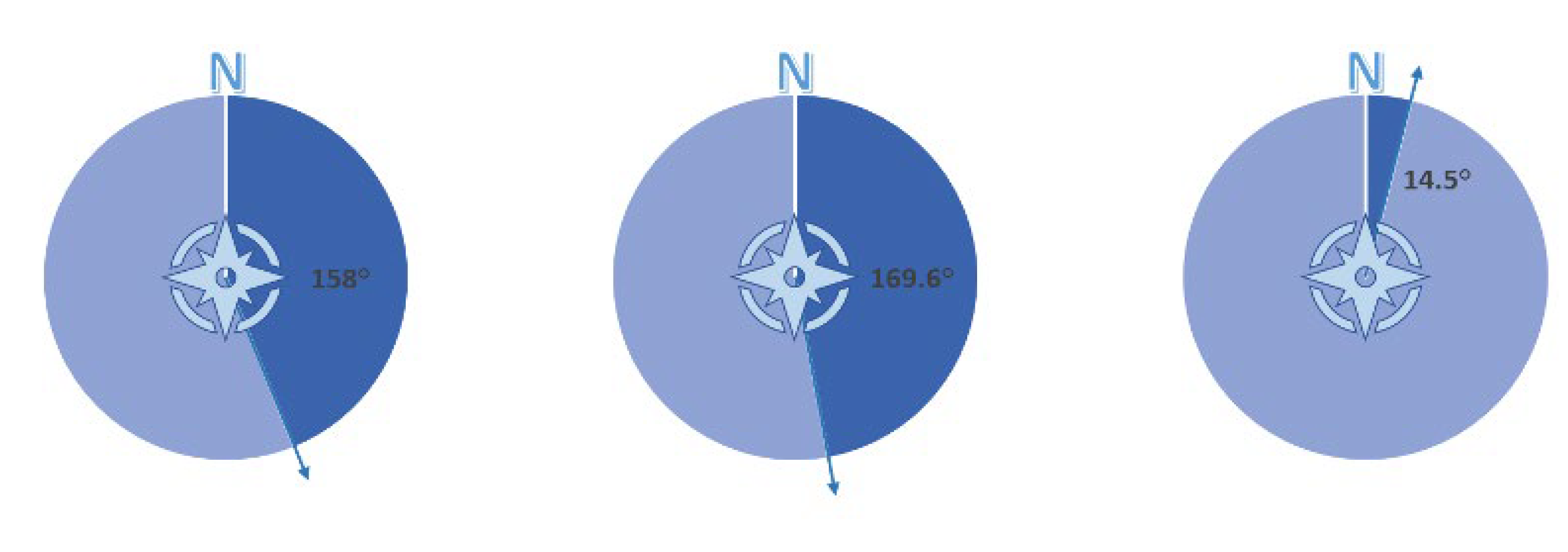

2.3. Weather Condition

2.4. Measurement Criteria and Procedure

3. Results

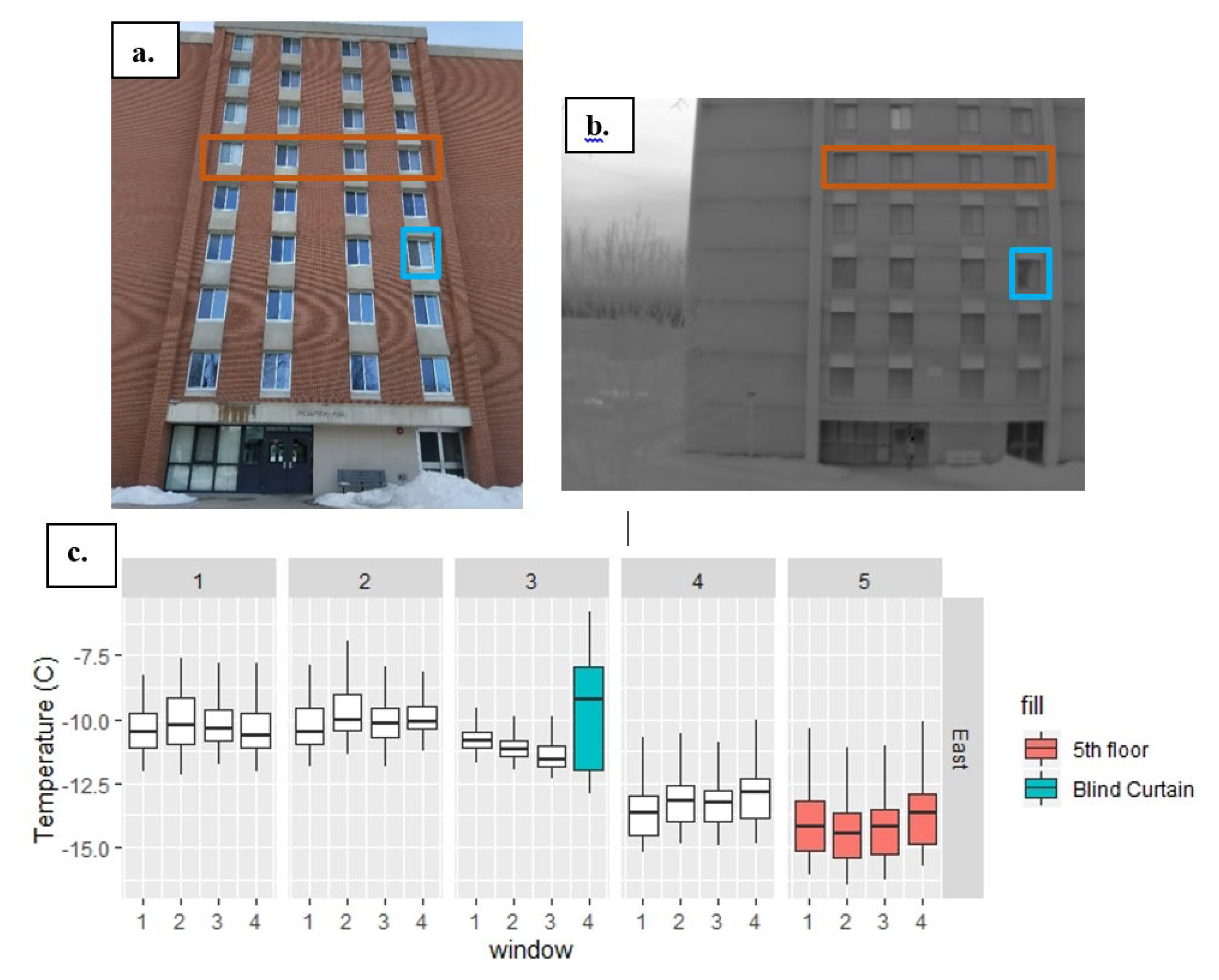

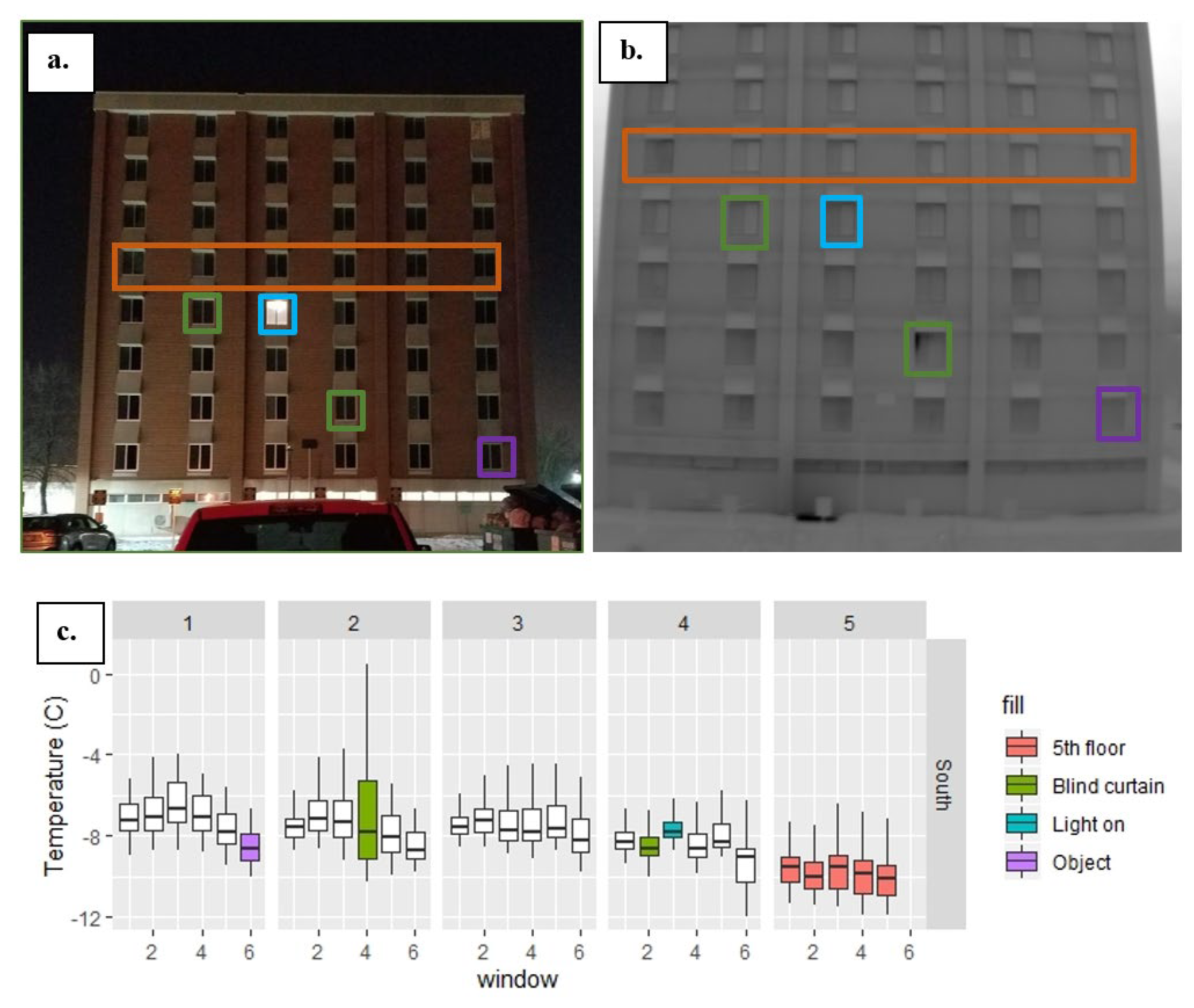

3.1. Effect of Blind Curtain and Light Reflection

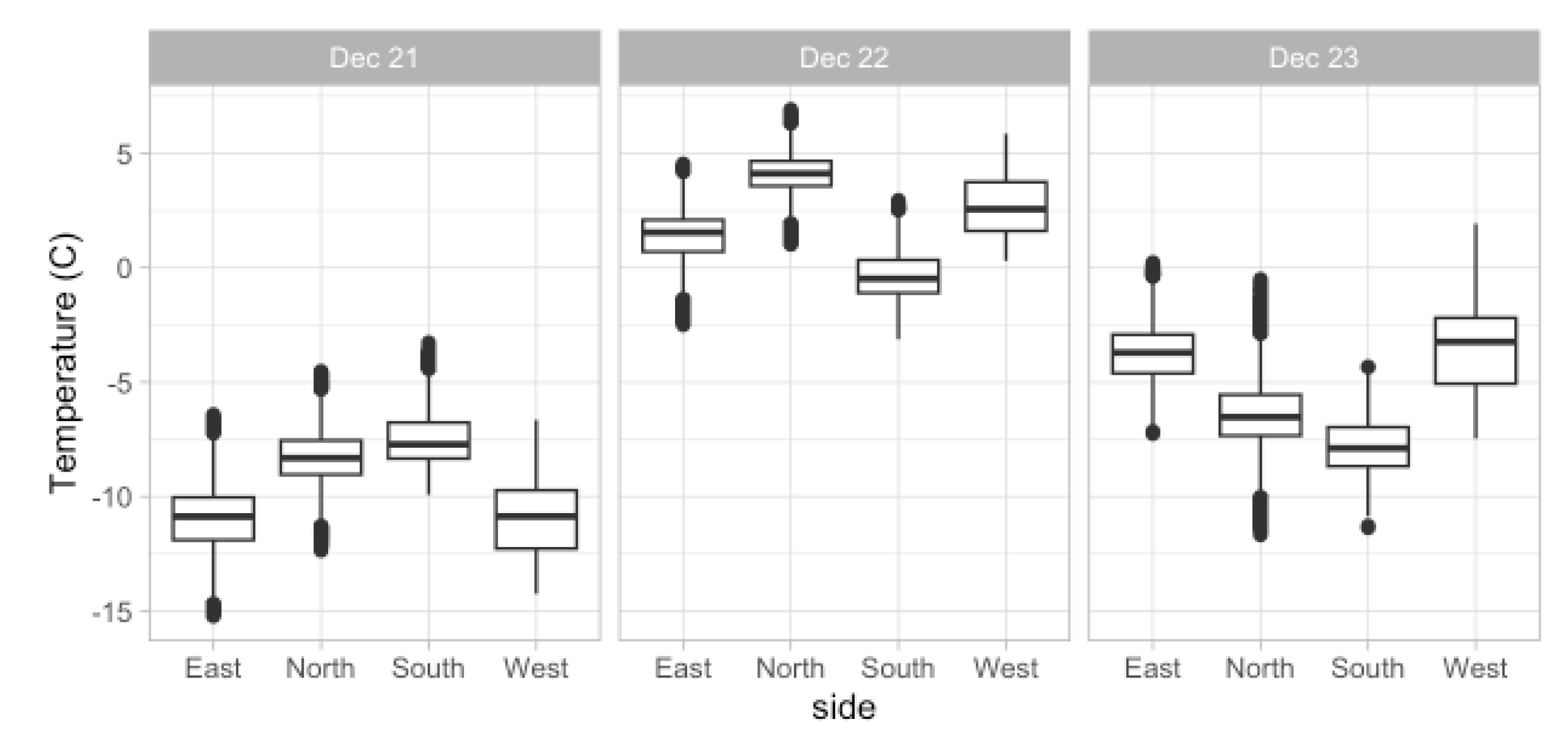

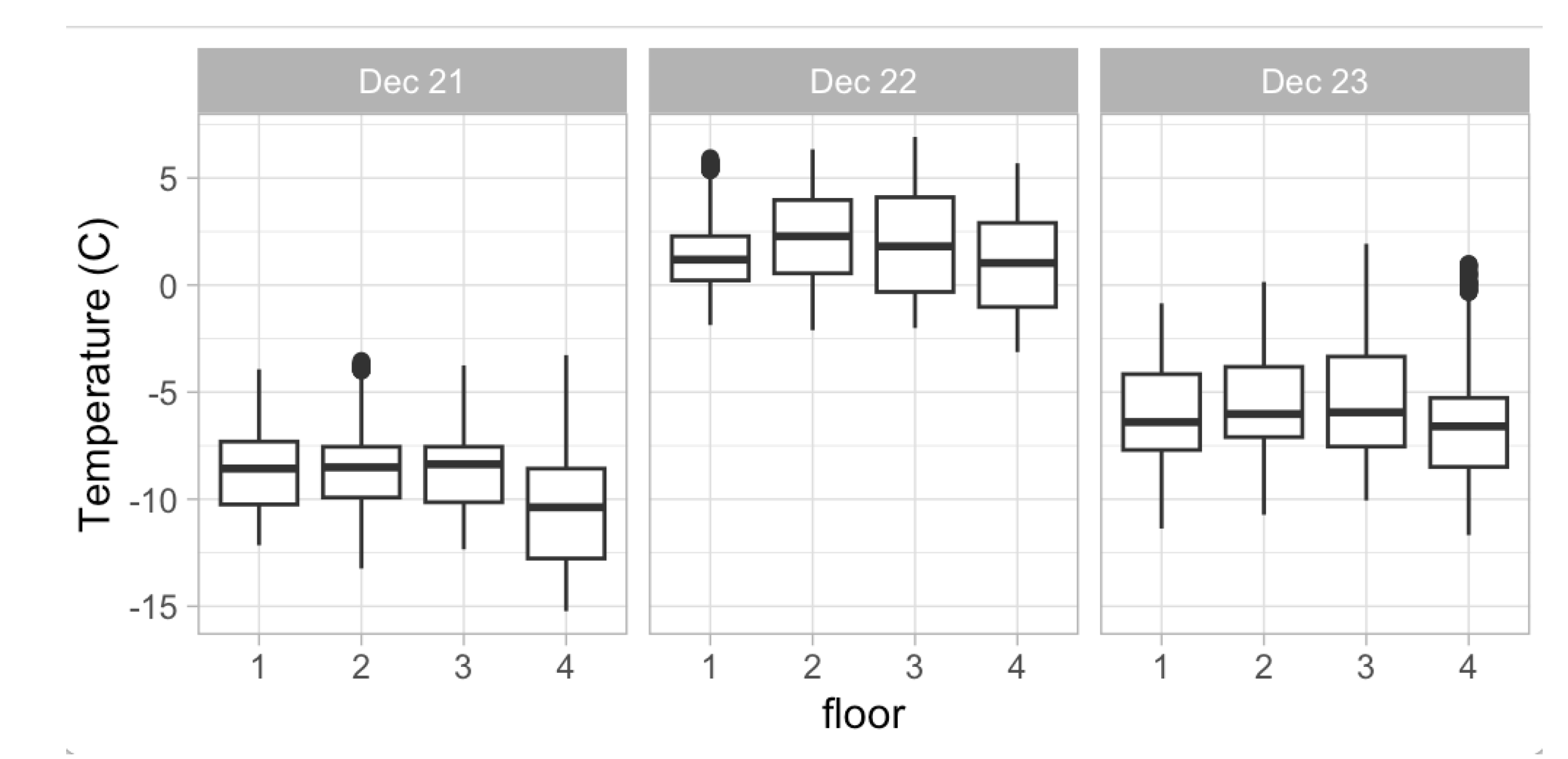

3.2. Day-by-Day Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- Lior, N. Sustainable Energy Development: The Present (2011) Situation and Possible Paths to the Future. Energy 2012, 43, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.S.; Hassan, M.Y.; Abdullah, M.P.; Rahman, H.A.; Hussin, F.; Abdullah, H.; Saidur, R. A Review on Applications of ANN and SVM for Building Electrical Energy Consumption Forecasting. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 33, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.X.; Magoulès, F. A Review on the Prediction of Building Energy Consumption. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 3586–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shah, N.; Papageorgiou, L.G. Efficient Energy Consumption and Operation Management in a Smart Building with Microgrid. Energy Conversion and Management 2013, 74, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stumpf, A.; Kim, W. Analysis of an Energy Efficient Building Design through Data Mining Approach. Automation in Construction 2011, 20, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grynning, S.; Gustavsen, A.; Time, B.; Jelle, B.P. Windows in the Buildings of Tomorrow: Energy Losers or Energy Gainers? Energy and Buildings 2013, 61, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Departament of Energy 2011 Buildings Energy Data Book. Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy 2012.

- Zeng, R.; Chini, A.; Srinivasan, R.S.; Jiang, P. Energy Efficiency of Smart Windows Made of Photonic Crystal. International Journal of Construction Management 2017, 17, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, O. Conjugate Heat Transfer Analysis of Double Pane Windows. Building and Environment 2006, 41, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, C.; Moretti, E. Glazing Systems with Silica Aerogel for Energy Savings in Buildings. Applied Energy 2012, 98, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Niu, J. lei; Chung, T. ming Comprehensive Analysis on Thermal and Daylighting Performance of Glazing and Shading Designs on Office Building Envelope in Cooling-Dominant Climates. Applied Energy 2014, 134, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, A.; Roos, A. Evaluation of Control Strategies for Different Smart Window Combinations Using Computer Simulations. Solar Energy 2010, 84, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.R.; Duer, K.; Svendsen, S. Energy Performance of Glazings and Windows. Solar Energy 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanda, F.H.; Byers, L. An Investigation of the Impact of Building Orientation on Energy Consumption in a Domestic Building Using Emerging BIM (Building Information Modelling). Energy 2016, 97, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaras, C.A.; Argiriou, A.A. Infrared Thermography for Building Diagnostics. Energy and Buildings 2002, 34, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’O’, G.; Sarto, L.; Sanna, N.; Martucci, A. Comparison between Predicted and Actual Energy Performance for Summer Cooling in High-Performance Residential Buildings in the Lombardy Region (Italy). Energy and Buildings 2012, 54, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.R.R.; McCann, D.M.M.; Forde, M.C.C. Application of Infrared Thermography to the Non-Destructive Testing of Concrete and Masonry Bridges. In Proceedings of the NDT and E International; Elsevier, June 1 2003; Vol. 36, pp. 265–275.

- Lucchi, E. Applications of the Infrared Thermography in the Energy Audit of Buildings: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariwoola, R.T.; Uddin, M.M.; Johnson, K. V. Use of Drone for a Campus Building Envelope Study.; 2016.

- Mauriello, M.L.; Froehlich, J.E. Towards Automated Thermal Profiling of Buildings at Scale Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and 3D-Reconstruction.; 2014; pp. 119–122.

- Krawczyk, J.; Mazur, A.; Sasin, T.; Stokłosa, A. Infrared Building Inspection with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Transactions of the Institute of Aviation 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, B.M.; Muñoz, N.; Thomas, L.P. Estimation of the Surface Thermal Resistances and Heat Loss by Conduction Using Thermography. Applied Thermal Engineering 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.; Wakili, K.G.; Frank, T.; Collado, B.V.; Tanner, C. Effects of Individual Climatic Parameters on the Infrared Thermography of Buildings. Applied Energy 2013, 110, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.; Coley, D.; Goodhew, S.; De Wilde, P. Thermography Methodologies for Detecting Energy Related Building Defects; Pergamon, 2014; Vol. 40, pp. 296–310;

- Fox, M.; Goodhew, S.; De Wilde, P. Building Defect Detection: External versus Internal Thermography. Building and Environment 2016, 105, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, J.W. NORTH DAKOTA TOPOGRAPHIC, CLIMATIC, AND AGRICULTURAL OVERVIEW By John W. Enz, January 16, 2003 Topographic Features: North Dakota Is Subdivided into Four Main Physiographic Regions: The; 2003.

- Dall’O’, G.; Sarto, L.; Panza, A. Infrared Screening of Residential Buildings for Energy Audit Purposes: Results of a Field Test. Energies 2013, 6, 3859–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FLIR Systems Thermal Imaging Guidebook for Building and Renewable Energy Applications; 2011.

- Pisello, A.L.; Castaldo, V.L.; Poli, T.; Cotana, F. Simulating the Thermal-Energy Performance of Buildings at the Urban Scale: Evaluation of Inter-Building Effects in Different Urban Configurations. Journal of Urban Technology 2014, 21, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Omar, N.A.; Syed Fadzil, S.F. Analysis of Building Envelope Thermal Behaviour Using Time Sequential Thermography.; 2014.

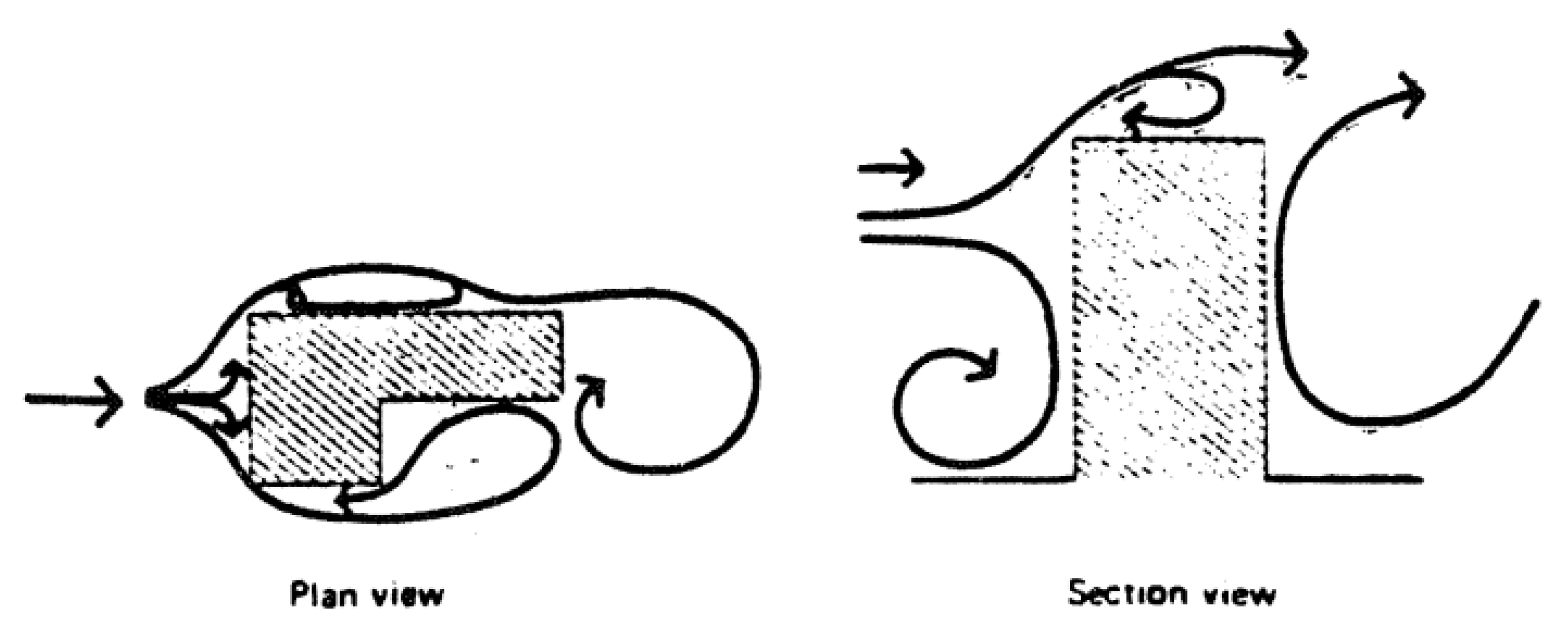

- Fleming, S. Buildings and Wind, Waterloo, CA, 2015.

| Case study project | Thompson Hall |

|---|---|

| Built date | 1965-1966 |

| Windows | Architectural Window/AW class, NAFS-08 Fixed Sash Screen Frame: Aluminum |

| Glazing | DSB sheet glass set in vinyl glazing channel |

| Size of window | 4’ x 5’(1.21 m x 1.52 m) |

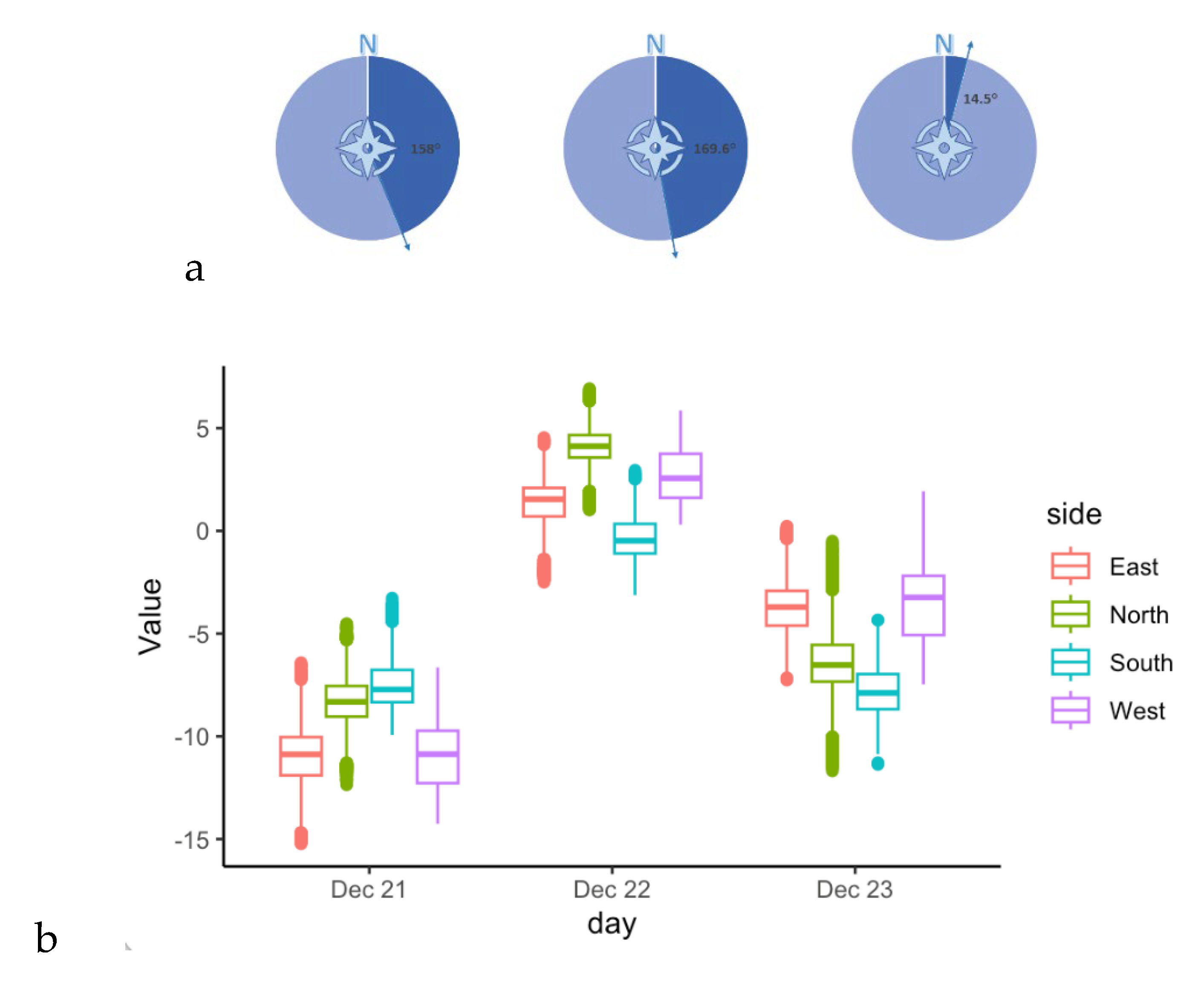

| Day (last week of Dec.) |

Air Temp (oC) |

Air Temp at 9 m (oC) |

Wind Chill (oC) |

Wind Speed (m/s) |

Wind Speed at 10 m (m/s) |

Wind Direction (degree) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturday | -8.7 | -8.5 | -14.5 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 158 |

| Sunday | -3.1 | -2.7 | -8.7 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 169.6 |

| Monday | -5.6 | -5.4 | -11.3 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 14.5 |

| Factors | Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F value | P-value | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

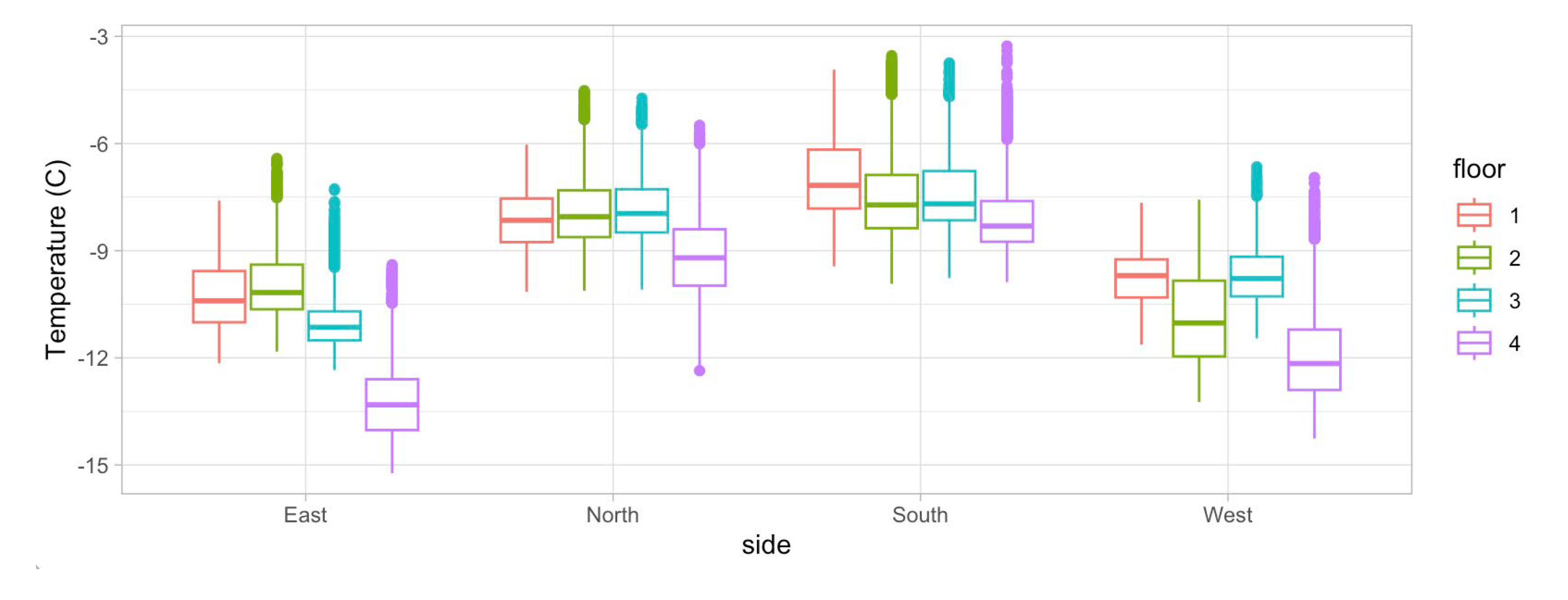

| Floor | 3 | 28725 | 9575 | 7655 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Side | 3 | 91941 | 30647 | 24501 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Floor: Side | 9 | 7630 | 848 | 678 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Residuals | 37000 | 46281 | 1 |

| Avg. (oC) | SD (oC) | Min (oC) | Max (oC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side | ||||

| East | -11.1d | 1.7 | -15.2 | -6.4 |

| North | -8.3b | 1.3 | -12.4 | -4.5 |

| South | -7.5a | 1.2 | -9.9 | -3.3 |

| West | -10.9c | 1.6 | -14.3 | -6.6 |

| Floor | ||||

| 1 | -8.6A | 1.8 | -12 | -3.9 |

| 2 | -8.6A | 1.7 | -13 | -3.5 |

| 3 | -8.7A | 1.8 | -12 | -3.8 |

| 4 | -10.6B | 2.4 | -15 | -3.3 |

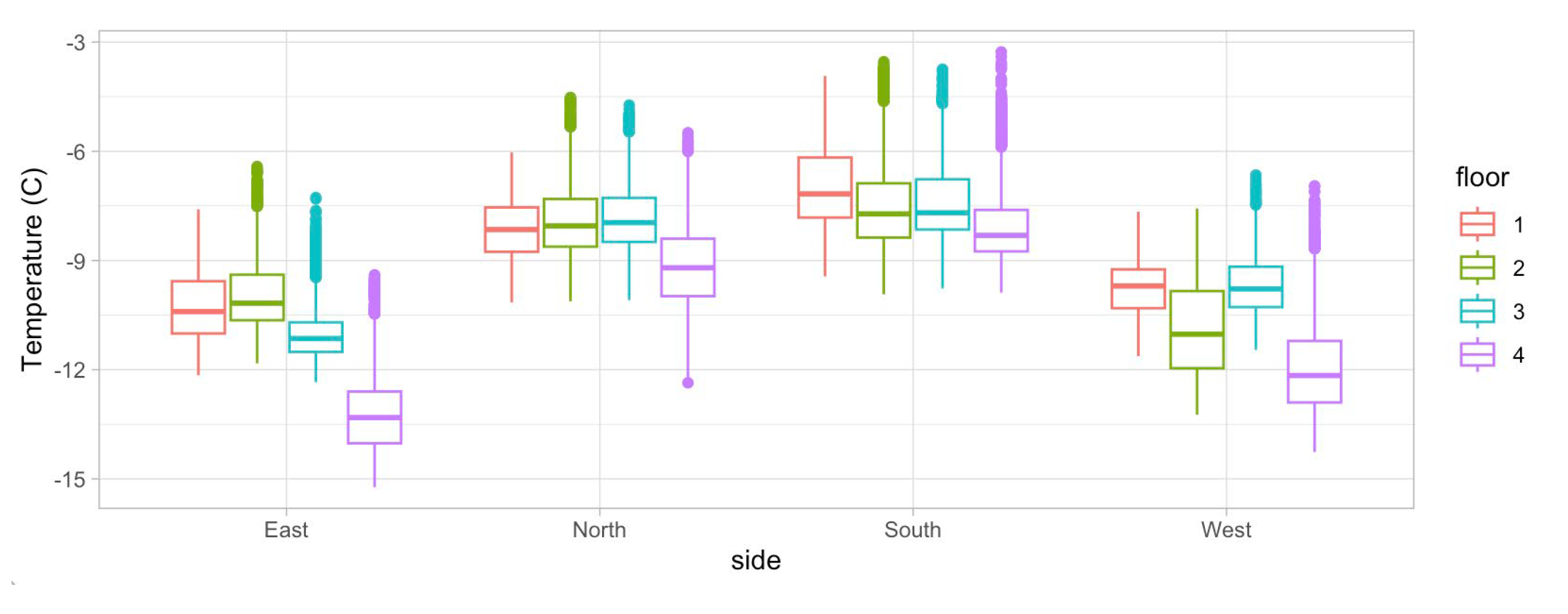

| Factors | Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F value | P-value | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floor | 3 | 9080 | 3027 | 3948 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Side | 3 | 106714 | 35571 | 46398 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Floor: Side | 9 | 3982 | 569 | 742 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Residuals | 31054 | 23808 | 1 |

| Factor | Avg. (oC) | SD (oC) | Min (oC) | Max (oC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side | ||||

| North | 4.11a* | 0.84 | 1.0 | 6.9 |

| West | 2.68b | 1.25 | 0.3 | 5.9 |

| East | 1.24c | 1.39 | -2.5 | 4.5 |

| South | -0.37d | 1.12 | -3.1 | 3.0 |

| Floor | ||||

| 1 | 1.42C | 1.5 | -1.9 | 5.9 |

| 2 | 2.27A | 2.0 | -2.1 | 6.3 |

| 3 | 2.05B | 2.3 | -2.0 | 6.9 |

| 4 | 0.96D | 2.3 | -3.1 | 5.7 |

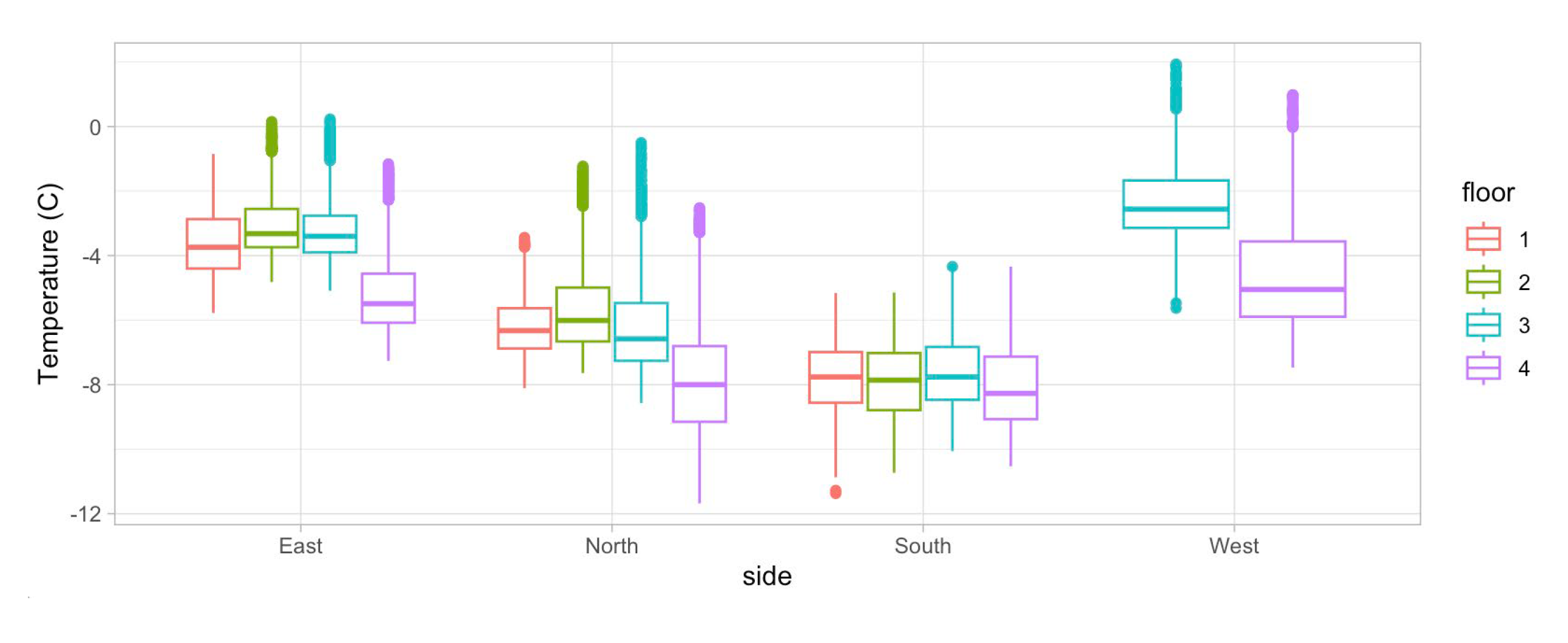

| Response/Value | Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F | P-value | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floor | 3 | 7417 | 2472 | 1400 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Side | 3 | 104547 | 34849 | 19734 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Floor: Side | 7 | 4299 | 614 | 348 | <2e-16 | Yes |

| Residuals | 32364 | 57152 | 2 |

| Factor | Avg. (oC) | SD (oC) | Min (oC) | Max (oC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side | ||||

| East | -3.8b* | 1.4 | -7.3 | 0.23 |

| North | -6.4c | 1.8 | -11.7 | -0.5 |

| South | -7.8d | 1.2 | -11.4 | -4.34 |

| West | -3.4a | 1.9 | -7.5 | 1.93 |

| Floor 1 |

-6.0C | 2.1 | -11 | -0.85 |

| 2 | -5.7B | 2.2 | -11 | 0.15 |

| 3 | -5.5A | 2.5 | -10 | 1.93 |

| 4 | -6.7D | 2.2 | -12 | 0.98 |

| Side | Avg. (oC) | SD (oC) | n | Min. (oC) | Max. (oC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | -4.5 a* | 5.4 | 12 | -13.1 | 2.1 |

| North | -3.5 b | 5.7 | 12 | -9.2 | 4.5 |

| South | -5.2 c | 3.6 | 12 | -8 | 0.3 |

| West | -5.4 c | 6.1 | 8 | -11.9 | 4 |

| Floors | Difference (oC) | Lower (oC) | Upper (oC) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 0.005 | -0.61 | 0.62 | 1 |

| 1-3 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 1.48 | 0* |

| 1-4 | -0.67 | -1.26 | -0.09 | 0.02* |

| 2-3 | 0.88 | 0.3 | 1.48 | 0* |

| 2-4 | -0.67 | -1.26 | -0.09 | 0.02* |

| 3-4 | -1.56 | -2.13 | -1.01 | 0* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).