Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Crabs Collection and Mating

2.3. RNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.4. SMRT Sequencing Data Processing

2.5. Collapsing Redundant Transcripts Isoforms

2.6. Completeness and Characteristics Analysis of Reconstructed Transcriptomes

2.7. Gene Functional Annotation

2.8. Alternative Splicing (AS) Events Analysis

2.9. Quantification of Identified Transcripts

2.10. Differential Alternative Splicing (DAE) Events, Differential Expressed Transcripts (DETs) and Their Enrichment Analysis

2.11. Validation of Differentially Expressed Genes

3. Results

3.1. Summary of PacBio Iso-Seq Data and Collapsing Redundant Isoforms

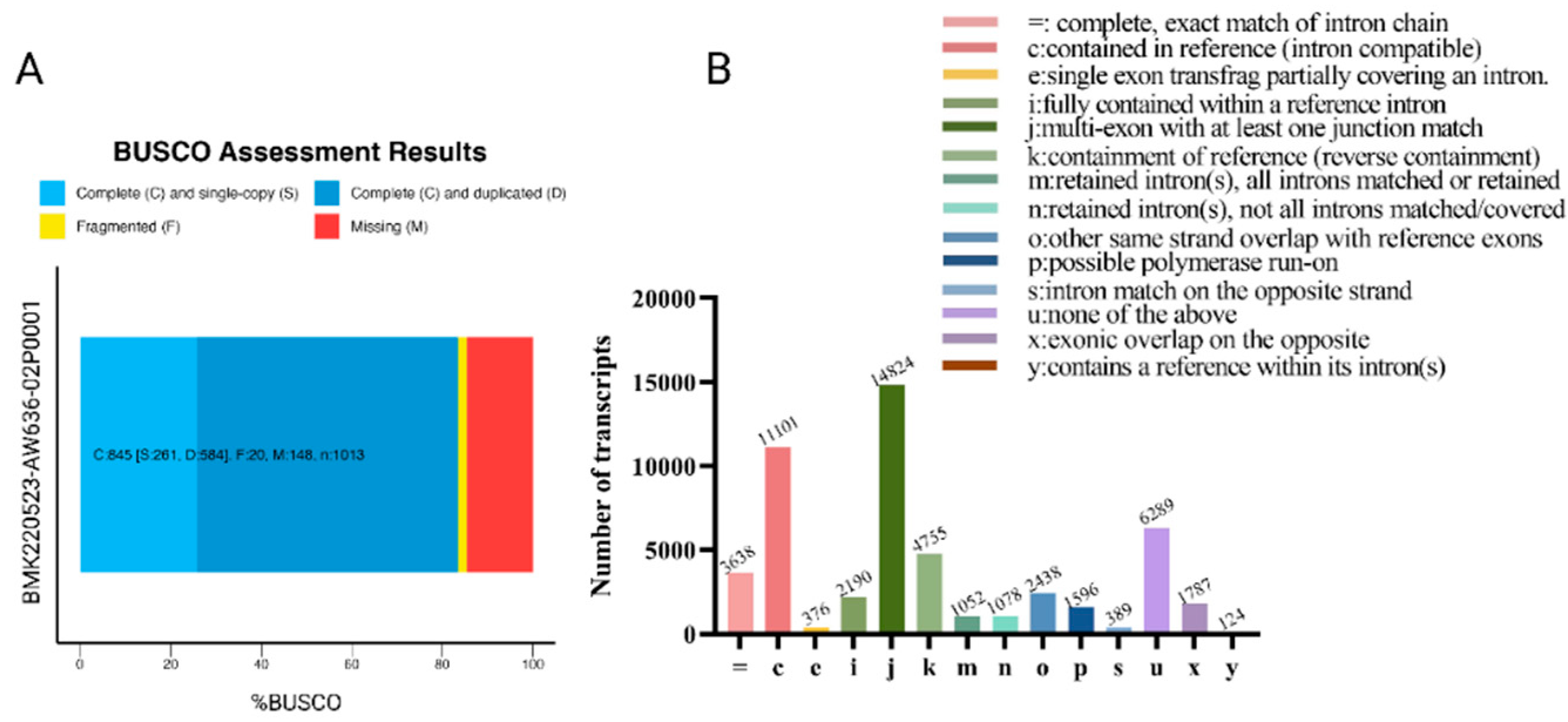

3.2. Evaluation of Reconstructed Transcriptomes

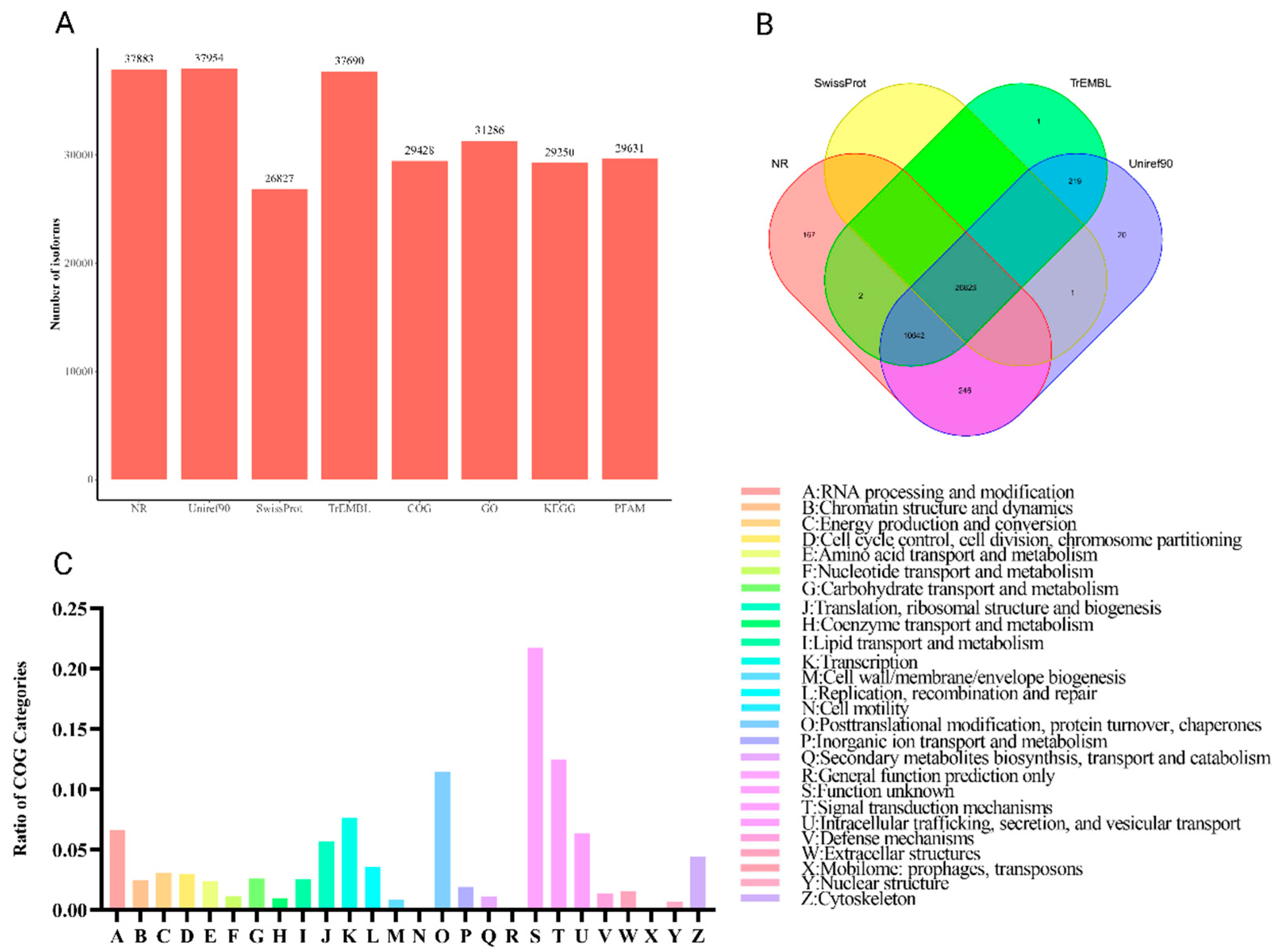

3.3. Functional Annotation

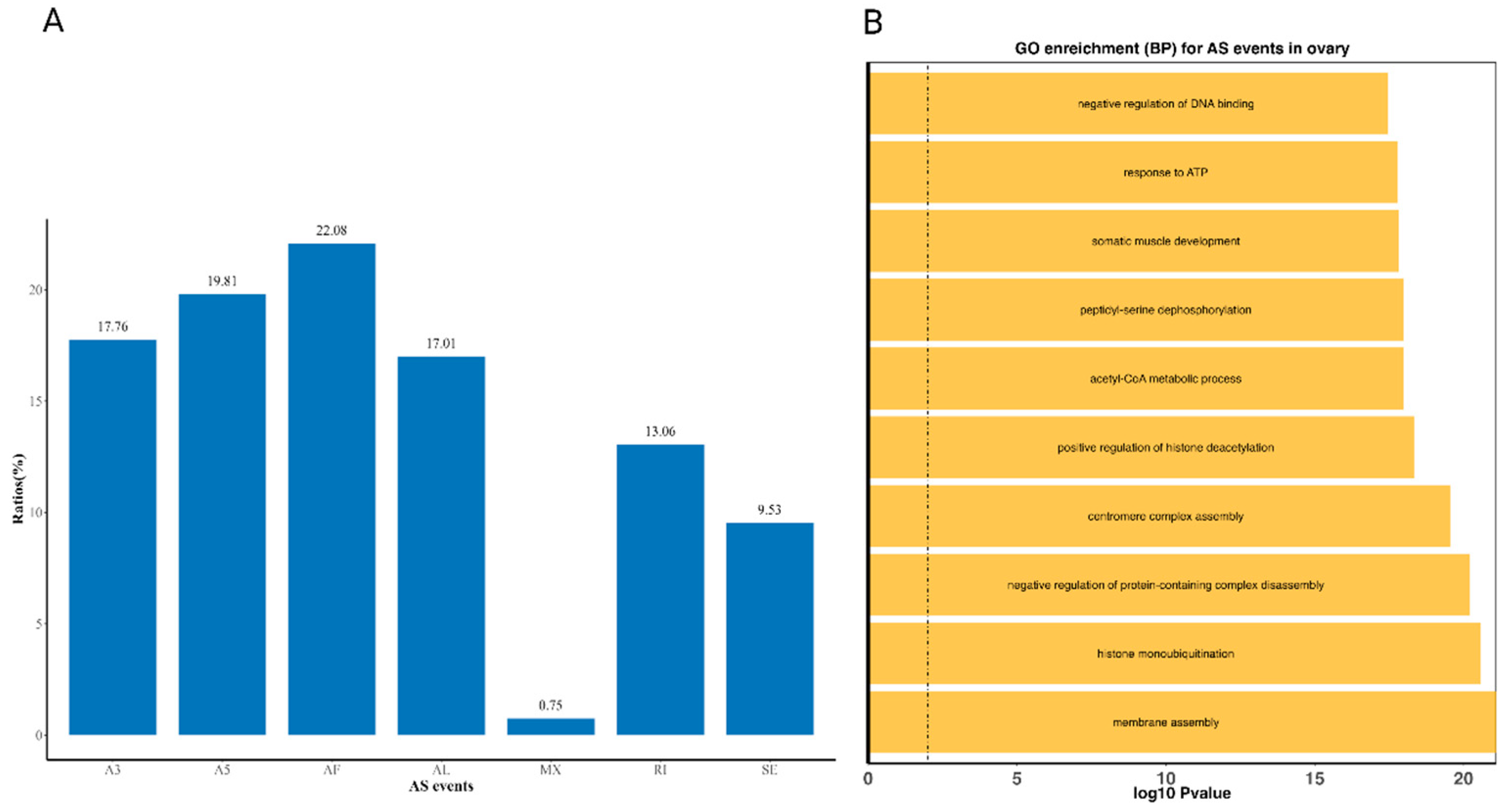

3.4. Alternative Splicing Events

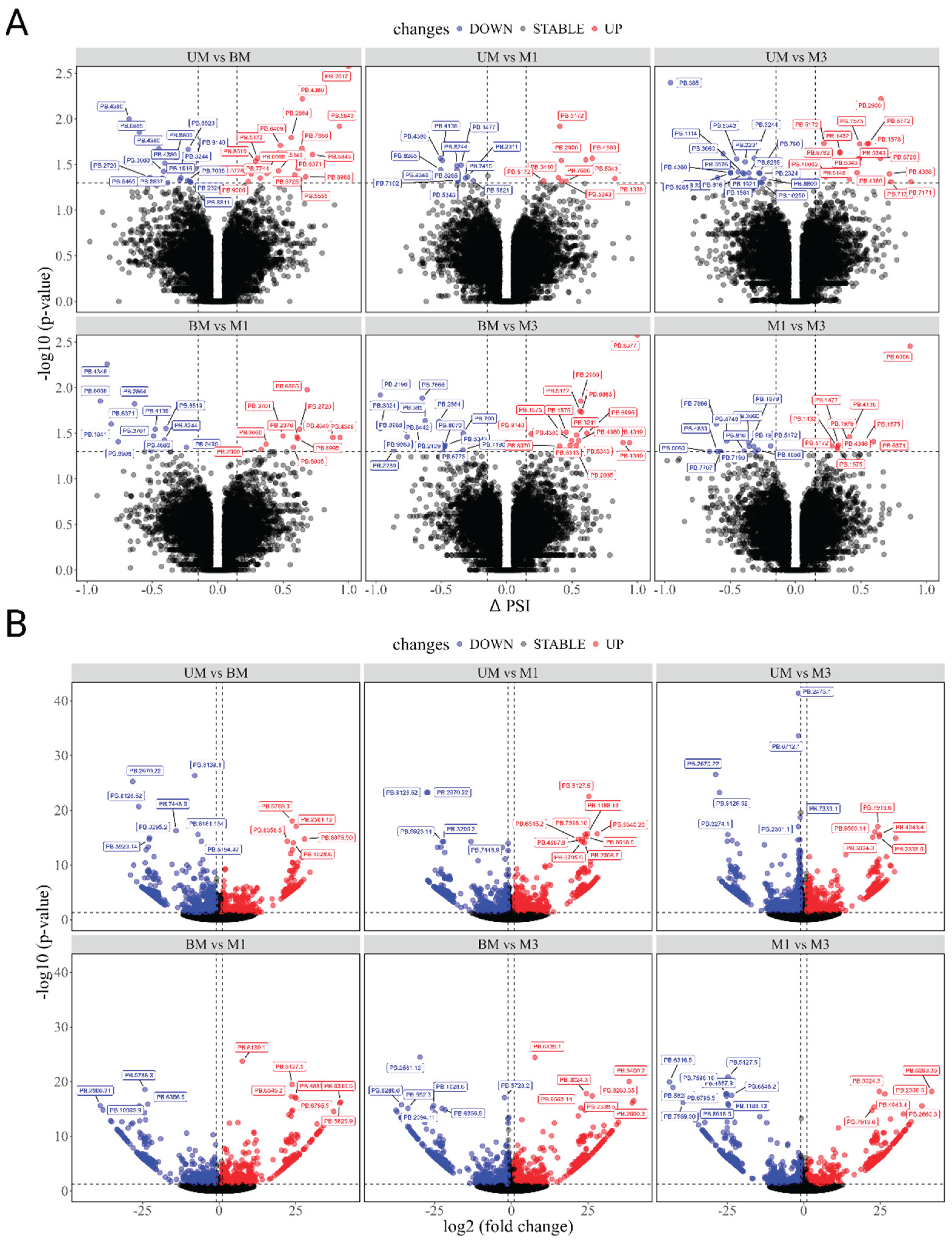

3.5. Differential Alternative Splicing (DAS) Events, Differential Expressed Transcripts (DETs), and Their Enrichment Analysis

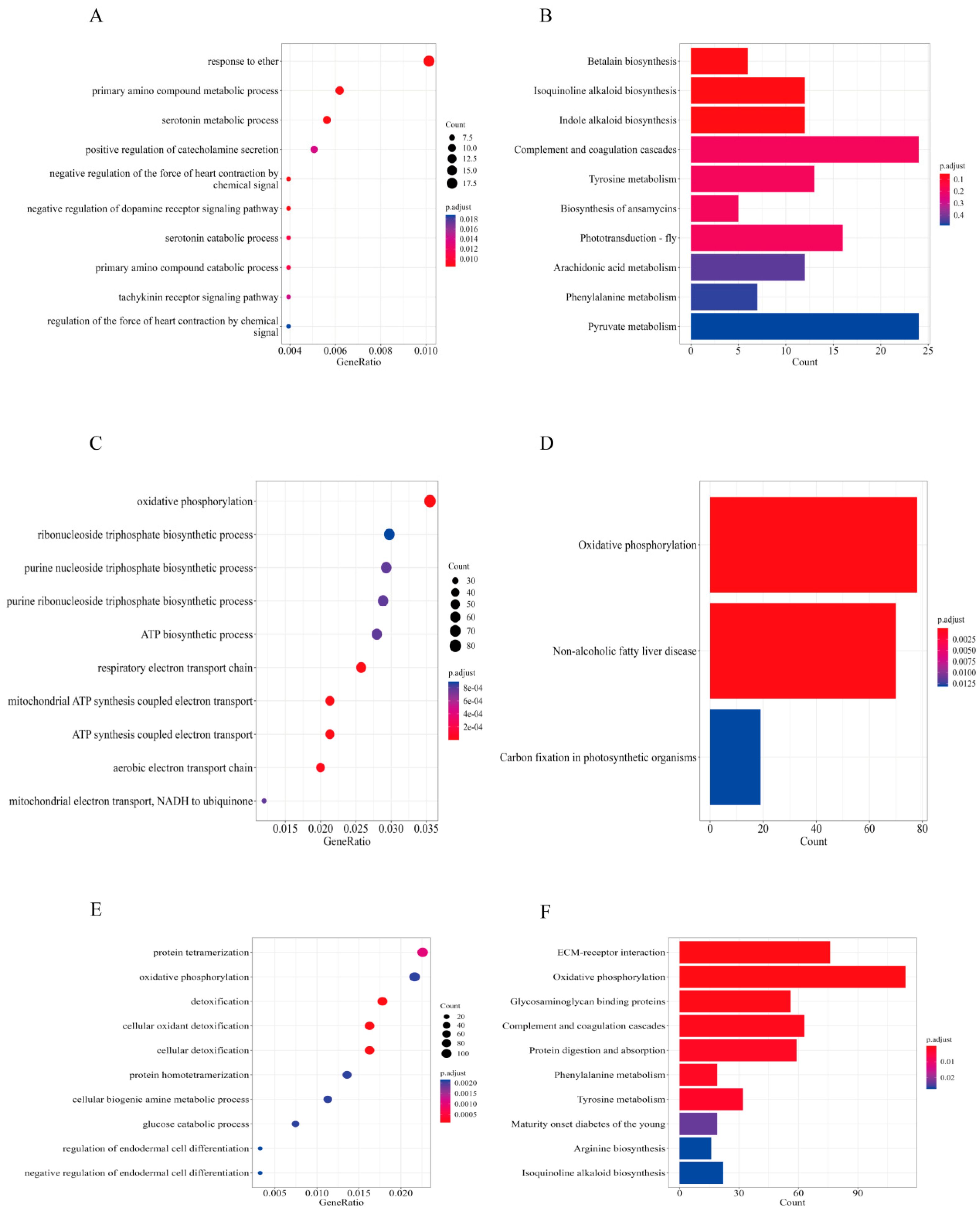

3.6. DAS and DETs Enrichment Analysis

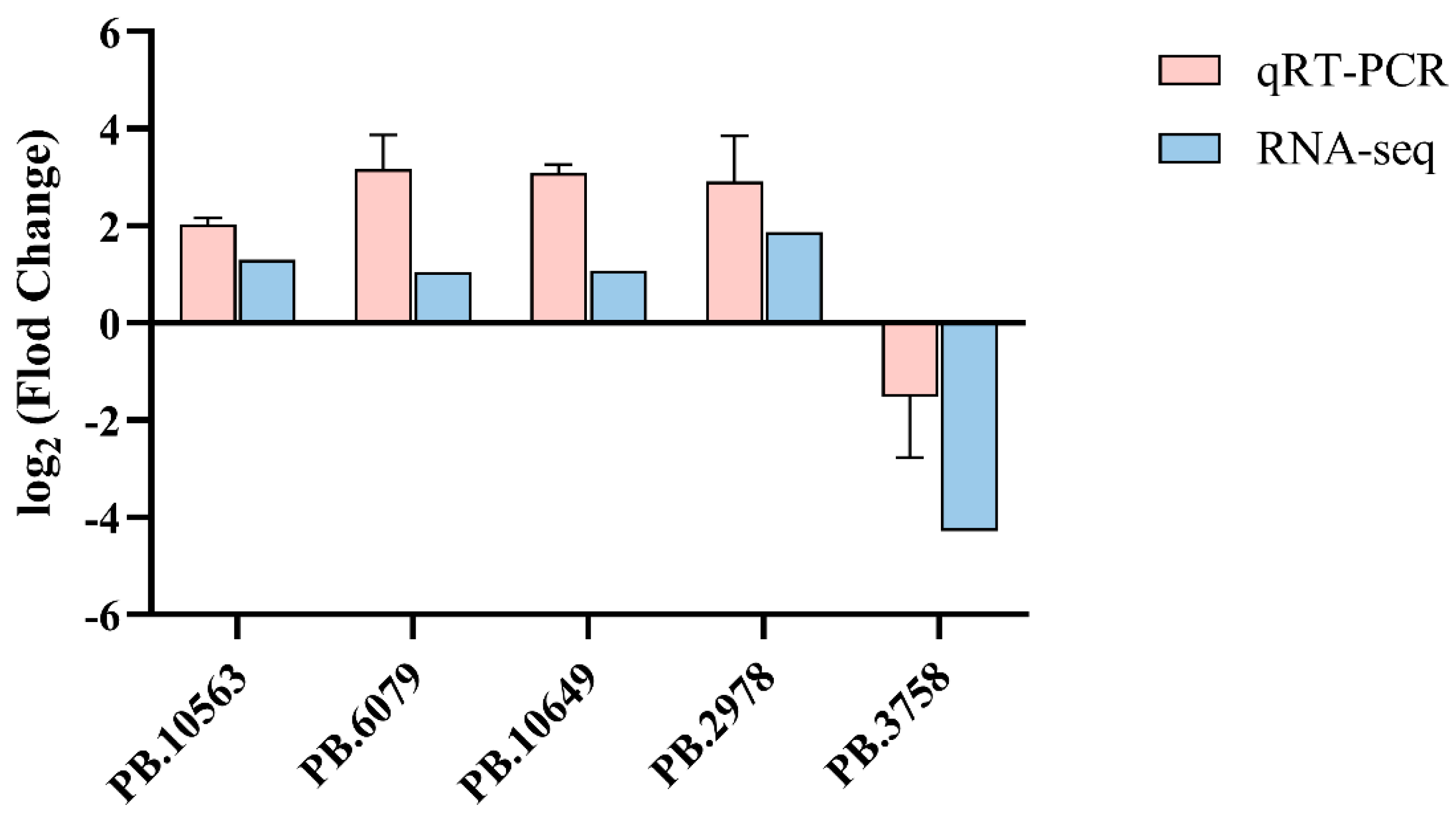

3.7. Validation of Significant Differential Expression Transcripts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanda, T.; Shimizu, T.; Iwasaki, T.; Dan, S.; Hamasaki, K. Effect of Temperature on Survival, Intermolt Period, and Growth of Juveniles of Two Mud Crab Species, Scylla Paramamosain and Scylla Serrata (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae), under Laboratory Conditions. Nauplius 2022, 30, e2022012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Waqas, W.; Cui, W.; Ye, S.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Zhu, D.; Lin, F.; Ikhwanuddin, M. Comparative Analysis of Embryonic Development and Growth Performance among Two Mud Crab Species and Their Hybrids. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Tao, Y.; Wang, G.; Lin, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, S. Experimental Nursery Culture of the Mud Crab Scylla Paramamosain (Estampador) in China. Aquac. Int. 2011, 19, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghia, T.T.; Wille, M.; Binh, T.C.; Thanh, H.P.; Van Danh, N.; Sorgeloos, P. Improved Techniques for Rearing Mud Crab Scylla Paramamosain (Estampador 1949) Larvae. Aquac. Res. 2007, 38, 1539–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishery Bureau of Ministry of Agriculture of China. China Fishery Statistical Yearbook 2024. Chinese Agricultural Press, Beijing, June, 2024.

- Quinitio, E.T.; De Pedro, J.; Parado-Estepa, F.D. Ovarian Maturation Stages of the Mud Crab Scylla Serrata. Aquac. Res 2007, 38, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, J.H. Timing of Hatching and Release of Larvae by Brachyuran Crabs: Patterns, Adaptive Significance and Control. Integr. and Comp. Biol. 2011, 51, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiho, K.; Fazhan, H.; Shahreza, M.S.; Moh, J.H.Z.; Noorbaiduri, S.; Wong, L.L.; Sinnasamy, S.; Ikhwanuddin, M. Transcriptome Analysis and Differential Gene Expression on the Testis of Orange Mud Crab, Scylla Olivacea, during Sexual Maturation. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.S.; Gardner, C.; Hochmuth, J.D.; Linnane, A. Environmental Effects on Fished Lobsters and Crabs. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2014, 24, 613–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, N.; Ma, H.; Kadri, S.; Tocher, D.R. Protein and Lipid Nutrition in Crabs. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1499–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpo, K.D.; López-Greco, L.S. Dynamics of Energy Reserves and the Cost of Reproduction in Female and Male Fiddler Crabs. Zoology 2018, 126, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Li, A.; Wu, D.; Qinyan, Y.; Yi, L.X.; He, G.; Lu, H. The Functional Role of lncRNAs as ceRNAs in Both Ovarian Processes and Associated Diseases. Non-coding RNA Res. 2024, 9, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Ye, H. Inhibitory Role of the Mud Crab Short Neuropeptide F in Vitellogenesis and Oocyte Maturation via Autocrine/paracrine Signaling. Front. Endocrinol 2018, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Kodama, K.; Kurokora, H. Ovarian Development of the Mud Crab Scylla Paramamosain in a Tropical Mangrove Swamps, Thailand. J. Sci. Res. 2010, 2, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Song, P.; Ma, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, G. Changes in Progesterone Levels and Distribution of Progesterone Receptor during Vitellogenesis in the Female Mud Crab (Scylla Paramamosain). MAR FRESHW BEHAV PHY 2010, 43, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifian, S.; Kamrani, E.; Safaie, M.; Sharifian, S. Oogenesis and Ovarian Development in the Freshwater Crab Sodhiana Iranica (Decapoda: Gecarcinuaidae) from the South of Iran. TISSUE CELL 2015, 47, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazhan, H.; Waiho, K.; Wan Norfaizza, W.I.; Megat, F.H.; Ikhwanuddin, M. Inter-Species Mating among Mud Crab Genus Scylla in Captivity. Aquaculture 2017, 471, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolkalya, S.; Thapanand, T.; Tunkijjanujij, S.; Havanont, V.; Jutagate, T. Aspects in Spawning Biology and Migration of the Mud Crab Scylla Olivacea in the Andaman Sea, Thailand. FISHERIES MANAG ECOL 2006, 13, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, C.L.; López Greco, L.S. A Hypothesis about the Origin of Sperm Storage in the Eubrachyura, the Effects of Seminal Receptacle Structure on Mating Strategies and the Evolution of Crab Diversity: How Did a Race to Be First Become a Race to Be Last? Zool. Anz. 2011, 250, 378–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, C.L.; Becker, C. Reproduction in Brachyura. Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Crustacea, 2015, 9, 185–243. [Google Scholar]

- Kulski, J.K. Next-Generation Sequencing — An Overview of the History, Tools, and “Omic” Applications. Next Generation Sequencing - Advances, Applications and Challenges 2016, 3-60.

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Jung, H.; Rotllant, G.; Hurwood, D.; Mather, P.; Ventura, T. Guidelines for RNA-Seq Projects: Applications and Opportunities in Non-Model Decapod Crustacean Species. Hydrobiologia 2018, 825, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykles, D.L.; Burnett, K.G.; Durica, D.S.; Joyce, B.L.; McCarthy, F.M.; Schmidt, C.J.; Stillman, J.H. Resources and Recommendations for Using Transcriptomics to Address Grand Challenges in Comparative Biology. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2016, 56, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, M.; Salzberg, S.L. Bioinformatics Challenges of New Sequencing Technology. TRENDS GENET 2008, 24, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, A.M.; Peluso, P.; Rowell, W.J.; Chang, P.C.; Hall, R.J.; Concepcion, G.T.; Ebler, J.; Fungtammasan, A.; Kolesnikov, A.; Olson, N.D.; et al. Accurate Circular Consensus Long-Read Sequencing Improves Variant Detection and Assembly of a Human Genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Chen, Z. jian; Wei, F. gang; Liu, Y. long; Gao, L.Z. SMRT- and Illumina-Based RNA-Seq Analyses Unveil the Ginsinoside Biosynthesis and Transcriptomic Complexity in Panax Notoginseng. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Yu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tan, H.; Song, J.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Farhadi, A.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; et al. Full-Length Transcriptome Reconstruction Reveals the Genetic Mechanisms of Eyestalk Displacement and Its Potential Implications on the Interspecific Hybrid Crab (Scylla Serrata ♀ × S. Paramamosain ♂). Biology. 2022, 11, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, A.; Cole, C.; Volden, R.; Vollmers, C. Realizing the Potential of Full-Length Transcriptome Sequencing. PHILOS T R. SOC B 2019, 374, 20190097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Cui, W.; Ye, S.; Fazhan, H.; Waiho, K.; Ikhwanuddin, M. Whole Transcriptome RNA Sequencing Provides Novel Insights into the Molecular Dynamics of Ovarian Development in Mud Crab, Scylla Paramamosain after Mating. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 2024, 51, 101247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. yun; Hao, H.; Wang, K.J. Internal Carbohydrates and Lipids as Reserved Energy Supply in the Pubertal Molt of Scylla Paramamosain. Aquaculture 2022, 549, 737736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, A.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H. A Novel Imprinted Gene (Sp-Pol) With Sex-Specific SNP Locus and Sex-Biased Expression Pattern Provides Insights Into the Gonad Development of Mud Crab (Scylla Paramamosain). Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 727607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yu, Y.; Gao, W.; Xiang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Fazhan, H.; Waiho, K.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H. Dynamic Changes Characteristics of the Spermatozoon during the Reproductive Process of Mud Crab (Scylla Paramamosain): From Spermatophore Formation, Transportation to Dispersion. Aquac. Reports 2023, 33, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; Qiu, B.; Wu, F.; Tocher, D.; Zhang, J.; Ye, S.; Cui, W.; et al. High-resolution chromosome-level genome of Scylla paramamosain provides molecular insights into adaptive evolution in crabs. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise Alignment for Nucleotide Sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Niu, B.; Gao, Y.; Fu, L.; Li, W. CD-HIT Suite: A Web Server for Clustering and Comparing Biological Sequences. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 680–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Update, B. Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 10–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriventseva, E. V.; Kuznetsov, D.; Tegenfeldt, F.; Manni, M.; Dias, R.; Simão, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. OrthoDB v10: Sampling the Diversity of Animal, Plant, Fungal, Protist, Bacterial and Viral Genomes for Evolutionary and Functional Annotations of Orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D807–D811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, G.; Pertea, M. GFF Utilities: GffRead and GffCompare. F1000Res 2020, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Forslund, K.; Coelho, L.P.; Szklarczyk, D.; Jensen, L.J.; Von Mering, C.; Bork, P. Fast Genome-Wide Functional Annotation through Orthology Assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trincado, J.L.; Entizne, J.C.; Hysenaj, G.; Singh, B.; Skalic, M.; Elliott, D.J.; Eyras, E. SUPPA2: Fast, Accurate, and Uncertainty-Aware Differential Splicing Analysis across Multiple Conditions. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon Provides Fast and Bias-Aware Quantification of Transcript Expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. ClusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes among Gene Clusters. Omi. A J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Francis, D.S.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, X. Effects of Fattening Period on Ovarian Development and Nutritional Quality of Adult Female Chinese Mitten Crab Eriocheir Sinensis. Aquaculture 2020, 519, 734748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.R.; Atallah, J.; Plachetzki, D.C. The Importance of Tissue Specificity for RNA-Seq: Highlighting the Errors of Composite Structure Extractions. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumova, O.Y.; Lee, M.; Rychkov, S.Y.; Vlasova, N. V.; Grigorenko, E.L. Gene Expression in the Human Brain: The Current State of the Study of Specificity and Spatiotemporal Dynamics. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Jia, X.; Zou, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. The Single-Molecule Long-Read Sequencing of Scylla Paramamosain. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioken, D.N.; Ozgul, I.; Erson-Bensan, A.E. The 3′ End of the Tale—neglected Isoforms in Cancer. FEBS Lett. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.X.; Chen, D.; Smagghe, G.; Wang, J.J.; Wei, D. Functional Characterization of a Glutathione S-Transferase Gene GSTe10 That Contributes to Ovarian Development in Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel). Entomol. Gen. 2022, 42, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, M.; Shi, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, J. The Ovarian Development Genes of Bisexual and Parthenogenetic Haemaphysalis Longicornis Evaluated by Transcriptomics and Proteomics. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 783404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.N.S.; Barcelos, R.M.; Vidigal, P.M.P.; Klein, R.C.; Montandon, C.E.; Maciel, T.E.F.; Carrizo, J.F.A.; Costa de Lima, P.H.; Soares, A.C.; Martins, M.M.; et al. A Deep Insight into the Whole Transcriptome of Midguts, Ovaries and Salivary Glands of the Amblyomma Sculptum Tick. Parasitol. Int. 2017, 66, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, J.; Almunia, C.; Gaillard, J.C.; Pible, O.; Chaumot, A.; Geffard, O.; Armengaud, J. Proteogenomic Insights into the Core-Proteome of Female Reproductive Tissues from Crustacean Amphipods. J. Proteomics 2016, 135, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepiz-Plascencia, G.; Vargas-Albores, F.; Higuera-Ciapara, I. Penaeid Shrimp Hemolymph Lipoproteins. Aquaculture 2000, 191, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, L.J.G.; Volpato, G.L.; Barreto, R.E.; Coldebella, I.; Ferreira, D. Chemical Communication of Handling Stress in Fish. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 103, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, G.K.; Nagabhushanam, R.; Amaldoss, G.; Jaiswal, R.G.; Fingerman, M. In Vivo Stimulation of Ovarian Development in the Red Swamp Crayfish, Procambarus Clarkii (Girard), by 5-Hydroxytryptamine. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 1992, 21, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Leng, X.; Du, H.; Wu, J.; He, S.; Luo, J.; Liang, X.; Liu, H.; Wei, Q.; et al. Metabolomics and Gene Expressions Revealed the Metabolic Changes of Lipid and Amino Acids and the Related Energetic Mechanism in Response to Ovary Development of Chinese Sturgeon (Acipenser Sinensis). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, N.; Kadri, S.; Kumar, V.; Ma, H. Serotonin: A Multifunctional Molecule in Crustaceans. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e70046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppe, L.; Edvardsen, R.B.; Furmanek, T.; Taranger, G.L.; Wargelius, A. Global Transcriptome Analysis Identifies Regulated Transcripts and Pathways Activated during Oogenesis and Early Embryogenesis in Atlantic Cod. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2014, 81, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inigo, M.; Deja, S.; Burgess, S.C. Ins and Outs of the TCA Cycle: The Central Role of Anaplerosis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hou, C.; Wang, C.; Mu, C. Analysis of cDNA microarrays revealed the effects of mating on the ovary and hepatopancreas of female swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus) during the late stage of ovarian develoment. COMP BIOCHEM PHYS D 2025, 55, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagyová, E.; Němcová, L.; Camaioni, A. Cumulus Extracellular Matrix Is an Important Part of Oocyte Microenvironment in Ovarian Follicles: Its Remodeling and Proteolytic Degradation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, T.E.; Osteen, K.G. The Matrix Metalloproteinase System: Changes, Regulation, and Impact throughout the Ovarian and Uterine Reproductive Cycle. Endocr. Rev. 2003, 24, 428–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Lyu, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Wen, H.; Shi, B. Integrated lncRNA and mRNA Transcriptome Analyses in the Ovary of Cynoglossus Semilaevis Reveal Genes and Pathways Potentially Involved in Reproduction. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 671729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreeger, P.K.; Deck, J.W.; Woodruff, T.K.; Shea, L.D. The in Vitro Regulation of Ovarian Follicle Development Using Alginate-Extracellular Matrix Gels. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tan, S.; Qi, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Sha, Z. Genome-Wide Characterization of Integrin (ITG) Gene Family and Their Expression Profiling in Half-Smooth Tongue Sole (Cynoglossus Semilaevis) upon Vibrio Anguillarum Infection. COMP BIOCHEM PHYS D 2023, 47, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhu, B.; Dong, T.; Wang, W.; Hu, M.; Yan, X.; Xu, S.; Hu, H. Whole-Genome Resequencing Reveals Selection Signatures for Caviar Yield in Russian Sturgeon (Acipenser Gueldenstaedtii). Aquaculture 2023, 568, 739312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, A.; Pereira, M.T.; Schuler, G.; Bleul, U.; Kowalewski, M.P. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF1alpha) Inhibition Modulates Cumulus Cell Function and Affects Bovine Oocyte Maturation in Vitro. Biol. Reprod. 2021, 104, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Peng, S.; Feng, J.; Zou, P.; Wang, Y. Immune Function Modulation during Artificial Ovarian Maturation in Japanese Eel (Anguilla Japonica): A Transcriptome Profiling Approach. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 131, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.J.; Peng, S.; Wang, Y.L. Dynamic Transcriptome Analysis of Ovarian Follicles in Artificial Maturing Japanese Eel (Anguilla Japonica). Theriogenology 2022, 180, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazali, A.; Azra, M.N.; Noordin, N.M.; Abol-Munafi, A.B.; Ikhwanuddin, M. Ovarian Morphological Development and Fatty Acids Profile of Mud Crab (Scylla Olivacea) Fed with Various Diets. Aquaculture 2017, 468, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Ríos, E.; León-Galván, M.A.; Mercado, P.E.; López-Wilchis, R.; Cervantes, D.L.M.I.; Rosado, A. Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase, and Glutathione Peroxidase in the Testis of the Mexican Big-Eared Bat (Corynorhinus Mexicanus) during Its Annual Reproductive Cycle. COMP BIOCHEM PHYS A 2007, 148, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, H.R.; Kodaman, P.H.; Preston, S.L.; Gao, S. Oxidative Stress and the Ovary. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2001, 8, S40–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y. A Novel and Compact Review on the Role of Oxidative Stress in Female Reproduction. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.D.; Yang, Q. Bin; Jiang, S.; Jiang, S.G.; Zhou, F.L. Transcriptome Analysis of Metapenaeus Affinis Reveals Genes Involved in Gonadal Development. ISR J AQUACULT - BAMID 2022, 74, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class code | Description |

|---|---|

| = | complete, exact match of intron chain |

| c | contained in reference (intron compatible) |

| k | containment of reference (reverse containment) |

| m | retained intron(s), all introns matched or retained |

| n | retained intron(s), not all introns matched/covered |

| j | multi-exon with at least one junction match |

| e | single exon transfrag partially covering an intron.possible pre-mRNA fragment |

| o | other same strand overlap with reference exons |

| s | intron match on the opposite strand (likely amapping error) |

| x | exonic overlap on the opposite strand (like o or ebut on the opposite strand) |

| i | fully contained within a reference intron |

| y | contains a reference within its intron(s) |

| p | possible polymerase run-on (no actual overlap) |

| r | repeat (at least 50% bases soft-masked) |

| u | none of the above (unknown, intergenic) |

| Types | Numbers of Sequences | Length of Isoforms | N506 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Mean | Max | |||

| Subreads | 59,566,665 | 51 | 1,705.6 | 240,063 | 2,300 |

| CCS1 | 880,044 | 97 | 2,222.4 | 14,561 | 2,721 |

| FL2 | 717,465 | 51 | 2,057.4 | 10,605 | 2,681 |

| FLCN3 | 713,486 | 50 | 2,012.4 | 10,573 | 2,654 |

| HQ4 | 59,156 | 51 | 2,074.8 | 8,730 | 2,769 |

| LQ5 | 36 | 140 | 2,293.1 | 8,310 | 3,319 |

| Numbers of Transcript Isoforms after Collapsing Redundants | Length of Collapsing Redundant Isoforms | N501 | |||||

| Reference Genome | Fake Genome | Unmap-Ped | Merge | Min | Max | Mean | |

| 50,170 | 1,483 | 25 | 51,637 | 82 | 8,730 | 2,056 | 2,761 |

| AS events | A3 | A5 | AF | AL | MX | RI | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | 2400 | 2676 | 2983 | 2298 | 101 | 1764 | 1288 |

| Group | DAS | DETs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers | upregulated | downregulated | Protein-coding Genes | numbers | upregulated | downregulated | |

| UM vs BM | 34 | 18 | 16 | 30 | 1032 | 490 | 542 |

| UM vs M1 | 21 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 1157 | 575 | 582 |

| UM vs M3 | 34 | 16 | 18 | 27 | 1963 | 1004 | 959 |

| BM vs M1 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 19 | 975 | 515 | 460 |

| BM vs M3 | 32 | 17 | 15 | 26 | 1245 | 664 | 581 |

| M1 vs M3 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 18 | 921 | 457 | 464 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).