Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

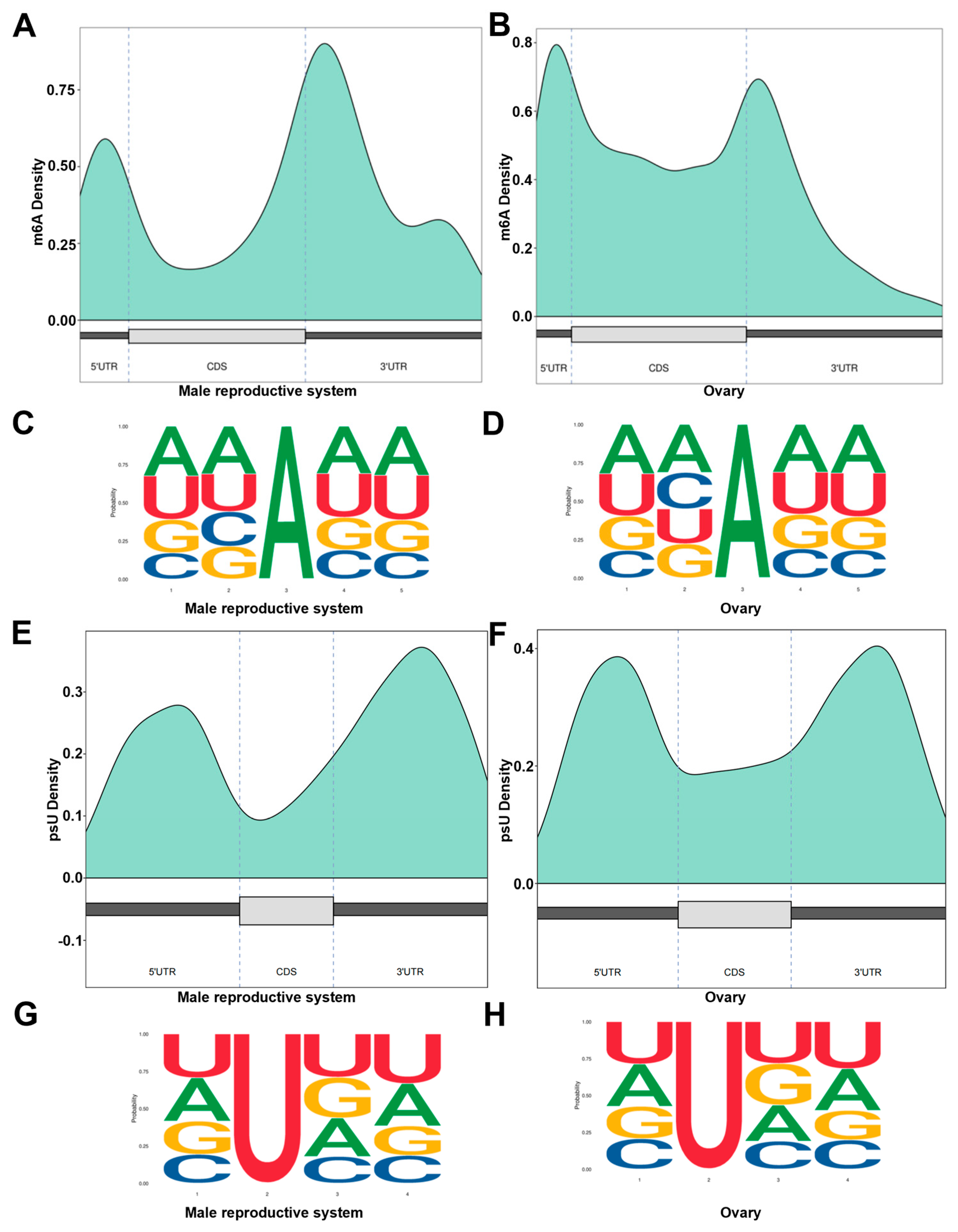

The red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) is a globally important freshwater crustacean that exhibits pronounced sexual dimorphism, with males growing faster than females. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying sex differentiation in crustaceans remain poorly understood. In this study, Oxford Nanopore-based Direct RNA Sequencing (DRS) was employed to analyze the gonadal transcriptomes of male and female P. clarkii, identifying 20,001 previously unannotated genes and revealing extensive sex-specific differences in transcript structure, alternative splicing, and RNA modifications. Ovarian transcripts had shorter polyA tails and more frequent alternative splicing, while male gonads showed greater enrichment of m6A and psU modifications in 3' UTR regions. qPCR validation confirmed the sex-biased expression of key candidate genes, including Dmrt7, FR, Fruitless, IAGBP, RDH, and Vtg. Collectively, these findings provide the first comprehensive epitranscriptomic landscape of P. clarkii gonads, underscoring the pivotal role of post-transcriptional regulation in sex determination and offering valuable insights for mono-sex breeding strategies in aquaculture.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. P. clarkii Sample Collection

2.2. Total RNA Extraction and mRNA Enrichment

2.3. Nanopore Sequencing Library Construction and Sequencing

2.4. Preprocessing, Alignment, and Novel Gene/Transcript Analysis

2.5. Transcript Structure Analysis

2.6. Isoform Poly(A) Length Analysis

2.7. RNA Methylation Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Statistics of DRS Data of the Gonads of P. clarkii

3.2. Differential Gene Expression Analysis Between Gonads

3.3. Structure Analysis of P. clarkii Genders

3.4. RNA Modification Analysis of P. clarkii Gonads

3.5. Verification of Potential Sex-Related Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Aquatic Technology Promotion Station, C.F. Society. China’s Crayfish Industry Development Report (2025); Fishery and Fishery Administration Bureau, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs: Beijing, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, Y. Exploration of an XX/XY Sex Determination System and Development of PCR-Based Sex-Specific Markers in Procambarus Clarkii Based on Next-Generation Sequencing Data. Front Genet 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudie, C.A.; Simco, B.A.; Davis, K.B.; Carmichael, G.J. Growth of Channel Catfish in Mixed Sex and Monosex Pond Culture. Aquaculture 1994, 128, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardmore, J.A.; Mair, G.C.; Lewis, R.I. Monosex Male Production in Finfish as Exemplified by Tilapia: Applications, Problems, and Prospects. Aquaculture, 2: 197.

- Wahl, M.; Hongrath, K.; Thinbanmai, T.; Suriyaworakul, P.; Aflalo, E.D.; Shechter, A.; Sagi, A. Field Validation of an All-Female Monosex Biotechnology for the Freshwater Prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquac Rep 2025, 42, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, M.; Levy, T.; Ventura, T.; Sagi, A. Monosex Populations of the Giant Freshwater Prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii—From a Pre-Molecular Start to the Next Generation Era. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 17433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, T.; Manor, R.; Aflalo, E.D.; Weil, S.; Rosen, O.; Sagi, A. Timing Sexual Differentiation: Full Functional Sex Reversal Achieved Through Silencing of a Single Insulin-Like Gene in the Prawn, Macrobrachium Rosenbergii1. Biol Reprod 2012, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, T.; Rosen, O.; Manor, R.; Dotan, S.; Azulay, D.; Abramov, A.; Sklarz, M.Y.; Chalifa-Caspi, V.; Baruch, K.; Shechter, A.; et al. Production of WW Males Lacking the Masculine Z Chromosome and Mining the Macrobrachium Rosenbergii Genome for Sex-Chromosomes. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, M.; Li, S.; Yuan, J.; Liu, P.; Fang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, F. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Mutation of EcIAG Leads to Sex Reversal in the Male Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, P.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Xiong, Y.; Yuan, H.; Gao, Z.; Gao, X.; Ma, C.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, Y.; et al. Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Hormone Induced Sex Reversal and Molecular Pathways in Macrobrachium Nipponense: Insights into Reproduction, Growth, and Sex Differentiation. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belote, J.M.; Baker, B.S. Sex Determination in Drosophila melanogaster: Analysis of Transformer-2, a Sex-Transforming Locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1982, 79, 1568–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Colbourne, J.K. A Molecular Mechanism for Environmental Sex Determination. Trends in Genetics 2024, 40, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Watanabe, H.; Iguchi, T. Environmental Sex Determination in the Branchiopod Crustacean Daphnia Magna: Deep Conservation of a Doublesex Gene in the Sex-Determining Pathway. PLoS Genet 2011, 7, e1001345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lin, W.; Ma, X.; Jawad, M.; Wu, M.; Qiu, J.; Li, M. A Timecourse Analysis of Gonadal Histology and Transcriptome during the Sexual Development of Yellow Catfish, Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics 2025, 56, 101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaked, S.A.; Levy, T.; Moscovitz, S.; Wattad, H.; Manor, R.; Ovadia, O.; Sagi, A.; Aflalo, E.D. All-Female Crayfish Populations for Biocontrol and Sustainable Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2024, 580, 740377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Xing, Z.; Lu, W.; Qian, Z.; Yu, H.; Li, J. Transcriptome Analysis of Red Swamp Crawfish Procambarus clarkii Reveals Genes Involved in Gonadal Development. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, T.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Lin, H.; Yan, W.; Pan, J.; Tang, J. A Chromosome-Level Reference Genome of Red Swamp Crayfish Procambarus clarkii Provides Insights into the Gene Families Regarding Growth or Development in Crustaceans. Genomics 2021, 113, 3274–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, M.; Xu, M.; Hu, R.; Xu, Z.; Bonvillain, C.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; et al. The Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of the Red Swamp Crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Sci Data 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Younas, L.; Zhou, Q. Evolution and Regulation of Animal Sex Chromosomes. Nat Rev Genet 2025, 26, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śnchez, L.; Granadino, B.; Torres, M. Sex Determination in Drosophila melanogaster : X-linked Genes Involved in the Initial Step of Sex-lethal Activation. Dev Genet 1994, 15, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuchi, T.; Koga, H.; Kawamoto, M.; Shoji, K.; Sakai, H.; Arai, Y.; Ishihara, G.; Kawaoka, S.; Sugano, S.; Shimada, T.; et al. A Single Female-Specific PiRNA Is the Primary Determiner of Sex in the Silkworm. Nature 2014, 509, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salz, H.K. Sex Determination in Insects: A Binary Decision Based on Alternative Splicing. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2011, 21, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stévant, I.; Nef, S. Genetic Control of Gonadal Sex Determination and Development. Trends in Genetics 2019, 35, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Y.J.; Sun, B.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.; Ping, X.L.; Lai, W.Y.; et al. Nuclear M6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates MRNA Splicing. Mol Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussmann, I.U.; Bodi, Z.; Sanchez-Moran, E.; Mongan, N.P.; Archer, N.; Fray, R.G.; Soller, M. M6A Potentiates Sxl Alternative Pre-MRNA Splicing for Robust Drosophila Sex Determination. Nature 2016, 540, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Hon, G.C.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Fu, Y.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Jia, G.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine-Dependent Regulation of Messenger RNA Stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, B.S.; Roundtree, I.A.; Lu, Z.; Han, D.; Ma, H.; Weng, X.; Chen, K.; Shi, H.; He, C. N6-Methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 2015, 161, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlegos, A.E.; Shields, E.J.; Shen, H.; Liu, K.F.; Bonini, N.M. Mettl3-Dependent M6A Modification Attenuates the Brain Stress Response in Drosophila. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalloh, B.; Lancaster, C.L.; Rounds, J.C.; Brown, B.E.; Leung, S.W.; Banerjee, A.; Morton, D.J.; Bienkowski, R.S.; Fasken, M.B.; Kremsky, I.J.; et al. The Drosophila Nab2 RNA Binding Protein Inhibits M6A Methylation and Male-Specific Splicing of Sex Lethal Transcript in Female Neuronal Tissue. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.D. Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation in Development and Beyond. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 1999, 63, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.C.; Fitzgibbon, Q.P.; Smith, G.; Elizur, A.; Ventura, T. Y-Linked IDmrt1 Paralogue (IDMY) in the Eastern Spiny Lobster, Sagmariasus verreauxi: The First Invertebrate Sex-Linked Dmrt. Dev Biol 2017, 430, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Type | Total Base | Total Reads | MaxLen. | Avg.Len. | N50 | L50 | N90 | L90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovary 1 | all | 7,203,329,705 | 7,190,385 | 352,878 | 1,001.8 | 1,333 | 1,586,575 | 587 | 4,685,197 |

| Ovary 1 | pass | 7,035,205,140 | 6,589,671 | 352,878 | 1,067.61 | 1,337 | 1,549,545 | 600 | 4,550,440 |

| Ovary 2 | all | 6,862,036,544 | 7,133,498 | 447,796 | 961.94 | 1,268 | 1,612,176 | 568 | 4,663,799 |

| Ovary 2 | pass | 6,677,586,014 | 6,476,178 | 447,796 | 1,031.09 | 1,270 | 1,567,948 | 581 | 4,509,429 |

| Male reproductive system 1 | all | 6,987,707,818 | 11,667,433 | 426,539 | 598.9 | 1,007 | 2,106,671 | 332 | 6,723,197 |

| Male reproductive system 1 | pass | 6,716,612,138 | 9,971,025 | 426,539 | 673.61 | 1,010 | 2,050,113 | 347 | 6,404,690 |

| Male reproductive system 2 | all | 7,292,510,116 | 12,766,003 | 429,741 | 571.24 | 962 | 2,346,459 | 318 | 7,381,459 |

| Male reproductive system 2 | pass | 7,058,291,748 | 10,676,480 | 429,741 | 661.1 | 971 | 2,279,150 | 333 | 7,031,049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).