1. Introduction

As one of the most common heart diseases in dogs, myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is associated with symptoms that include cough and increased respiratory effort. The typical pathophysiological consequences of mitral valve diseases, regardless of etiology, are left atrial (LA) dilatation and pulmonary hypertension (PH) [

1,

2]. Although direct measurement of PH via transvenous pulmonary artery catheterization is considered the definitive diagnostic approach, this method is invasive and rarely used in veterinary practice. As an alternative, transthoracic echocardiography is frequently employed as a noninvasive screening method to evaluate the presence or absence of PH [

3]. In cases of moderate to severe PH, characteristic echocardiographic signs include pulmonary artery (PA) enlargement and an elevated pulmonary artery-to-aortic (Ao) diameter ratio. [

4]. Additionally, Doppler echocardiography, specifically spectral Doppler analysis of tricuspid or pulmonary valve regurgitation, allows for the estimation of pulmonary arterial pressure using the modified Bernoulli equation. However, quantification may be difficult when regurgitant flow is minimal, and pressure estimation becomes impossible when no regurgitation is present [

5]. As a result, two-dimensional echocardiographic assessments of PA size have been adopted as alternative markers for diagnosing PH in canine patients [

6].

Recent research has increasingly focused on investigating dependable inflammatory biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases, given that inflammation and oxidative stress play key roles in the development of heart failure [

7,

8]. A clinical study in humans revealed that compared with healthy participants, individuals with congestive heart failure (CHF) presented a significantly elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). The NLR, which is derived by dividing the neutrophil count by the lymphocyte count, has emerged as a novel marker of systemic inflammation. Recent findings suggest that a high NLR independently predicts both overall mortality and cardiovascular-related death [

9,

10]. Prior research has also demonstrated a link between an elevated NLR and an increased risk of death or the need for heart transplantation in patients with chronic heart failure. In dogs with CHF, a notable increase in neutrophils and monocytes, along with a reduction in lymphocytes, was also observed [

11,

12,

13].

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) and approachable inflammatory biomarkers, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), are valuable indicators of systemic inflammation and are easily derived from standard blood profiles [

14]. Unlike single types of inflammatory cells, these composite ratios provide a broader assessment of the inflammatory process by reflecting interactions among cell types, thereby yielding a more accurate picture of immune and inflammatory status [

15]. Consequently, they serve as markers of systemic inflammation and are promising as diagnostic and prognostic tools in human medicine for the treatment of various inflammatory disorders and heart diseases. For instance, elevated CRP levels and NLRs have been linked to cardiovascular conditions, including coronary artery disease, stroke, mitral valve disease, and other adverse cardiac outcomes [

16,

17]. Moreover, LA volume is useful for predicting pulmonary artery hypertension in dogs with mitral valve disease [

18]. Pulmonary hypertension is the focus of an ongoing prospective study of the pathophysiology of MMVD in dogs with risk factors for congestive heart failure [

19,

20]. However, data on the relationships among the CRP level, NLR, left atrial (LA) volume, left ventricular diameter, and main pulmonary artery diameter are limited. The aim of this study is to investigate the relationships among inflammatory biomarkers, left atrial (LA) size, and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PH) in dogs with mitral valve degeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

This study retrospectively reviewed electronic medical records of dogs diagnosed with MMVD at the Kasetsart University Veterinary Teaching Hospital and Thonglor Pet Hospital between June 2023 and June 2025. Informed consent was obtained and signed by the patient owners involved in the study. To qualify, dogs needed to have undergone hematology within 24 hours of an echocardiographic exam that confirmed MMVD, regardless of whether clinical symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, coughing, exercise intolerance, or collapse) were present. Dogs were selected based on regular physical and echocardiographic evaluations. Dogs were excluded if they had cardiac diseases unrelated to MMVD, hematologic abnormalities, infectious diseases, inflammatory conditions, or had received medications affecting white blood cell counts, such as corticosteroids, within the past three months. The diagnosis of MMVD was based on echocardiographic findings consistent with the condition, such as valve thickening and/or prolapse, and the presence of mitral regurgitation using color Doppler. Dogs were categorized into disease stages according to the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) classification system [

21,

22].

2.2. Echocardiography

The experienced sonographers conducted echocardiography according to established guidelines to confirm mitral valve disease and exclude other cardiac disorders [

23,

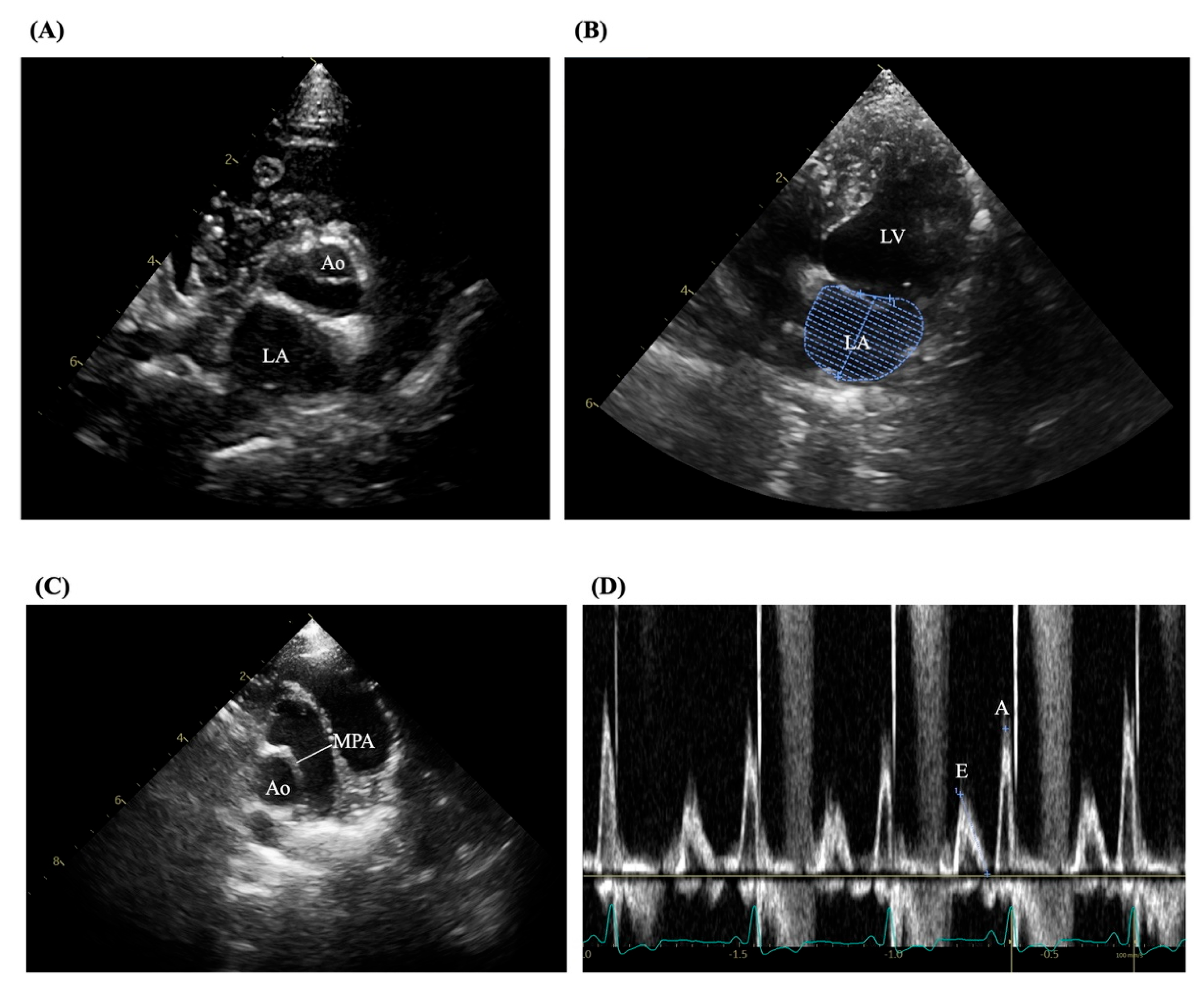

24]. Examinations were performed using a Philips ultrasound machine (Bothell, WA, USA) equipped with 5.0–9.0 MHz phased-array transducers. All assessments followed standardized imaging protocols as outlined by the American Society of Echocardiography and utilized 2D, M-mode, color flow Doppler, and tissue Doppler imaging. Measured variables included LV internal diameters at diastole (LVIDd) and systole (LVIDs), fractional shortening (FS), LA diameter, aortic diameter (Ao), LA volume, and pulmonary artery diameter (MPA). Trans-mitral flow velocities were measured using pulsed-wave Doppler, and the E/A ratio was derived as shown in

Figure 1 (A-D). Tissue Doppler imaging was applied to obtain peak velocities at the lateral mitral annulus.

2.3. Blood Work and Biomarker Evaluation

Venous blood was drawn from the cephalic vein into EDTA tubes for hematological assessment. A hematology analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, USA) was used within one hour of collection to quantify the total white blood cell count, as well as the counts of neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, and platelets. From these data, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were derived.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Results for continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between the MMVD and control groups were assessed using Student’s t-test. To compare MMVD stages and the control group, a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was applied for inter-stage comparisons within MMVD. The Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction was used. The same non-parametric test was used to evaluate differences in echocardiographic parameters between dogs with and without pulmonary hypertension. Pearson’s correlation and linear regression were used to assess relationships between echocardiographic parameters and other biomarkers. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to evaluate the diagnostic performance of biomarkers in detecting the presence and severity of MMVD. For survival analysis, cardiac death was considered the endpoint. A p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Overview

The study included 94 dogs diagnosed with MMVD, with a median age of 11 years. According to the ACVIM classification, eight dogs were in stage B1, 43 dogs were in stage B2, 38 dogs were in stage C, and five dogs were in stage D. The most prevalent breeds among affected dogs were Pomeranians (n = 32; 34.04%), Chihuahuas (n = 27; 28.72%), Shih Tzus (n = 13; 13.83%), Poodles (n = 6; 6.38%), Yorkshire Terriers (n = 3; 3.20%), mixed breeds (n = 7; 7.45%), and other breeds (n = 6; 6.38%). Other breeds had fewer than two dogs. Cardiac remodeling, as indicated by the LA/Ao ratio, significantly increased starting at the MMVD stage B2. General characteristics, blood profiles, and echocardiographic findings are summarized in

Table 1,

Table 2, and

Table 3, respectively.

3.2. Echocardiographic Parameters of the Study Animals

The available echocardiographic parameters of all the animals are given in

Table 2. We found that the variables, consisting of the left atrium, left ventricle, and pulmonary artery, were significantly different. Compared with those in the stage B1 and B2 groups, the left atrium size and main pulmonary artery diameter in the stage C and D groups increased considerably. Compared with those in the stage B group, the LA volume in the stage C and D groups was considerably greater.

3.3. The Correlation Matrix of Inflammatory Biomarkers and Echocardiographic Parameters in Animals

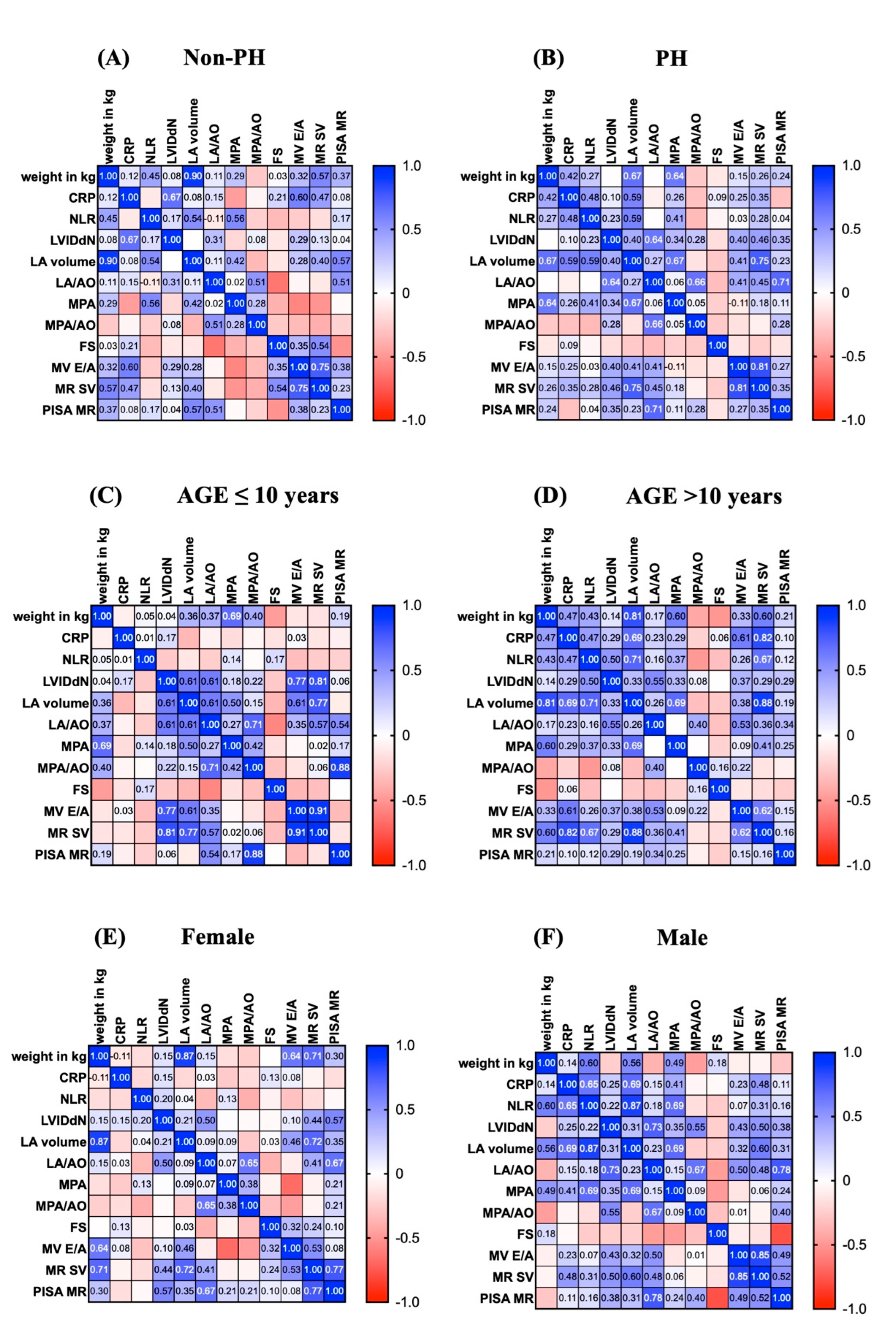

In this study, we created probability matrices that demonstrated the correlations between inflammatory biomarkers and echocardiographic parameters related to pulmonary artery hypertension (PH) (

Figure 2A–F). Compared with those in the non-PH group, the echocardiography parameters and inflammatory markers (CRP) in the PH group were associated with increased LA volume and main pulmonary artery diameter (MPA) (0.59 vs. 0.08 and 0.59 vs. 0.17, respectively) (

Figure 2A–2B). In addition, dogs older than 10 years of age appeared to have a greater likelihood of increasing echocardiographic parameters (

Figure 2C-2D). In addition, male dogs had a higher probability of increased LA and LVIDdN (

Figure 2E-2F). Taken together, these data suggest that male dogs aged more than 10 years are likely to develop PH.

3.4. Inflammatory Biomarkers in Study Animals

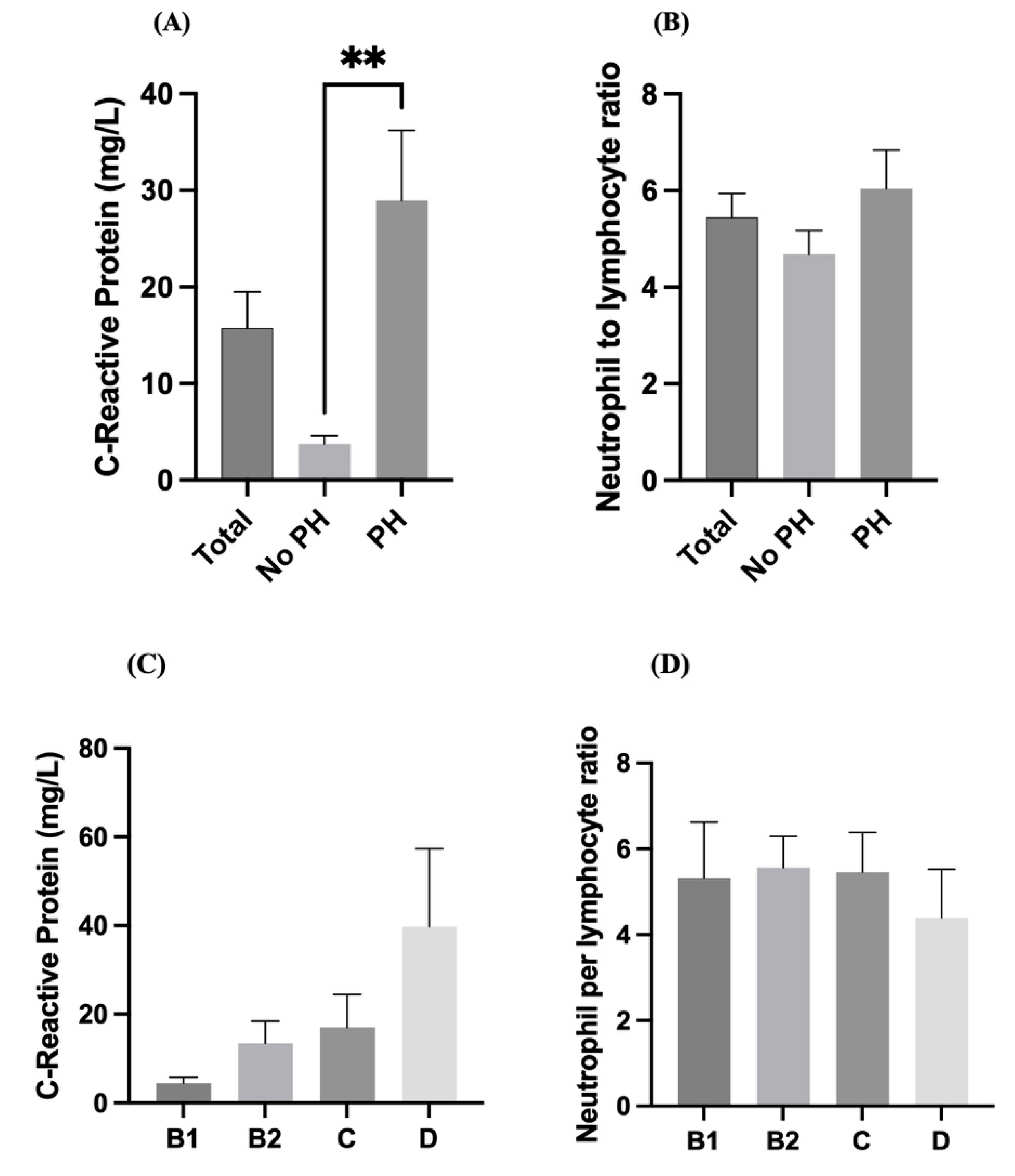

Dogs with pulmonary hypertension (PH) had significantly higher serum CRP levels than those without PH did (p < 0.01). Notably, mean CRP levels in the PH group were greater than 30 mg/L, whereas they remained below 10 mg/L in the non-PH group (

Figure 3A). These findings indicate a strong association between elevated CRP levels and the presence of pulmonary hypertension. Although the NLR was significantly greater in the PH group than in the non-PH group, the difference was not statistically significant. The average NLR remained between 5 and 7 across groups (

Figure 3B), indicating that the NLR may not be a sensitive marker for distinguishing PH in this population. The CRP levels tended to gradually increase across the advancing stages of heart disease (B1 < B2 < C < D), with the highest values observed in Stage D (

Figure 3C). Despite the increasing trend, there is substantial variability in CRP levels, and no statistical significance is indicated. However, the NLR values were relatively consistent across all stages (B1 to D), with no significant differences observed (

Figure 3D). These findings suggest that systemic inflammation measured by the NLR may not change significantly with increasing heart disease stage.

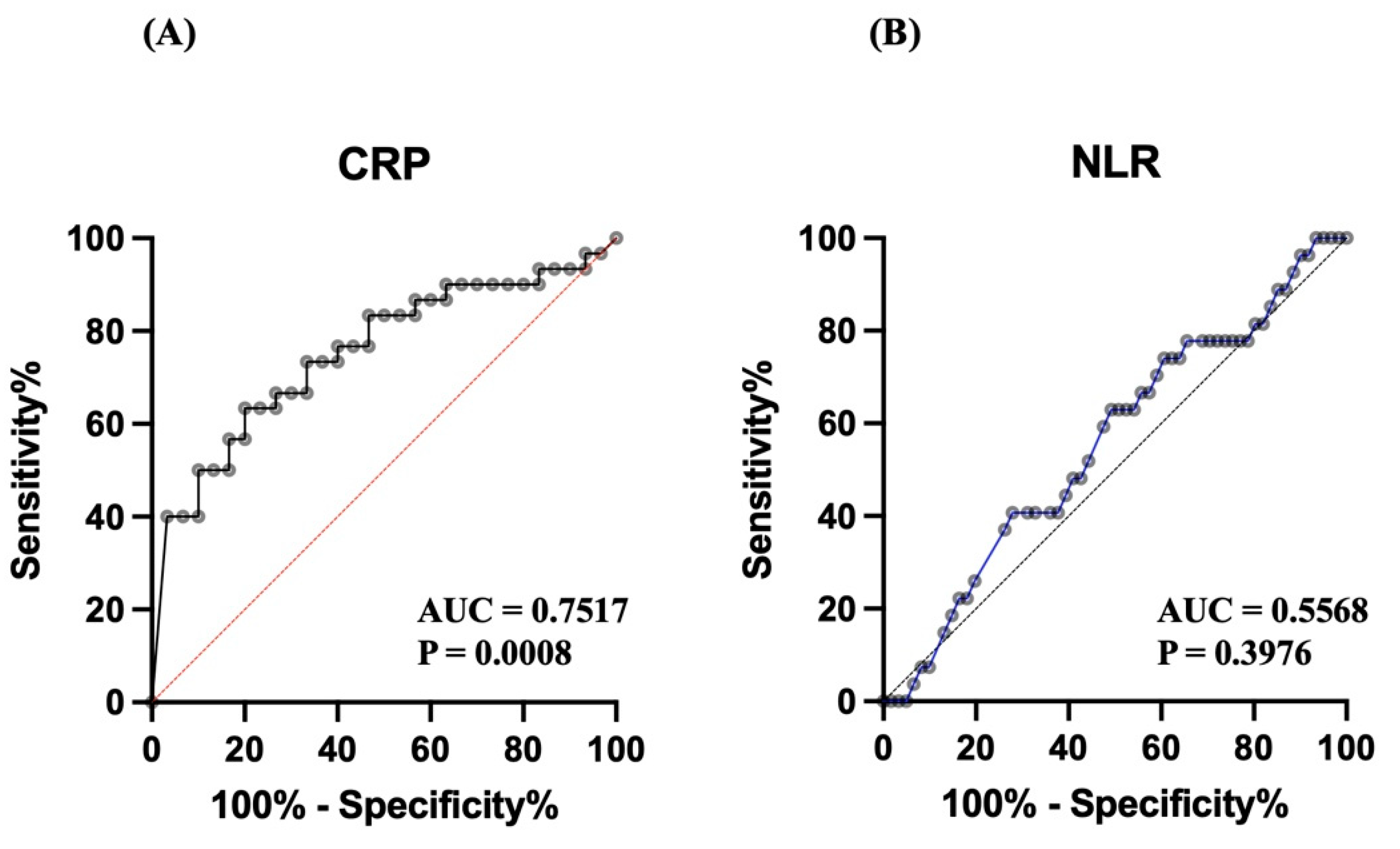

Two biomarkers, C-reactive protein (CRP) level and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), were evaluated for their ability to distinguish between diseased and control subjects using ROC analysis. CRP (

Figure 4A) demonstrated good diagnostic performance, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.7517 (P = 0.0008), indicating that CRP has statistically significant discriminatory power. On the other had, the NLR (

Figure 4B) had poor diagnostic performance, with an AUC of 0.5568 and a nonsignificant P value of 0.3976, suggesting its limited utility as a diagnostic marker in this population of dogs.

3.5. Survival Analysis

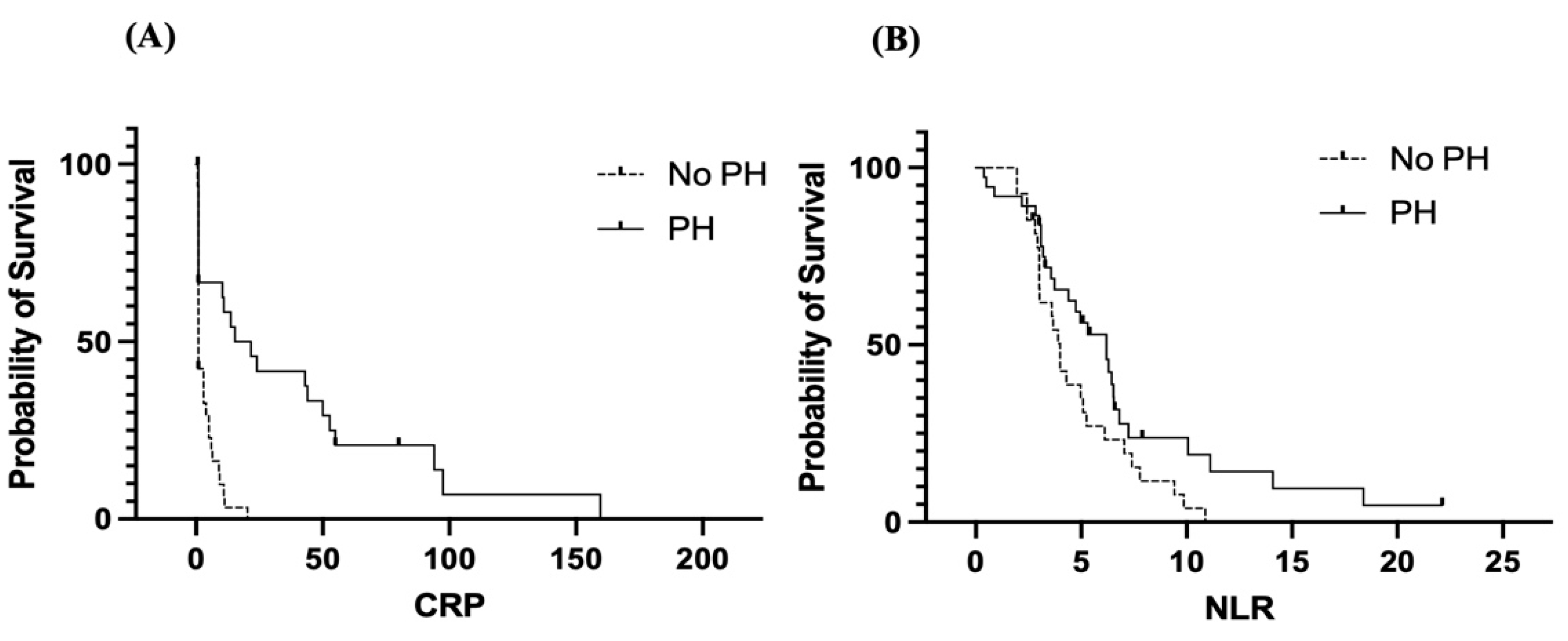

Elevated CRP levels are associated with overall reduced (

Figure 5A). CRP appears to be a stronger predictor of poor outcomes in patients without PH than in those with PH. The inflammatory response reflected by the CRP level might contribute differently to prognosis in these two groups. Dogs with PH (solid line) have a greater survival probability with increasing CRP levels than those without PH (dashed line). Survival in the non-PH group decreased rapidly at low CRP levels and remained near zero, indicating that even mild elevations in CRP are strongly associated with poor outcomes in this group. In contrast, the PH group retained a higher survival probability over a broader CRP range, although survival also decreased with increasing CRP level.

A high NLR was associated with poor survival in both groups (

Figure 5B), supporting its role as a negative prognostic marker. Like the CRP level, the NLR seems to be a more sensitive prognostic indicator in the non-PH group. As a marker of systemic inflammation and immune response, the NLR may reflect disease severity or underlying comorbidities affecting survival. Dogs with MMVD and concurrent PH (solid line) tend to maintain better survival than those without concurrent PH (dashed line) across a range of NLR values. However, in both the non-PH and PH groups, as the NLR increased, the survival probability decreased. Compared with the PH group, the non-PH group had a more rapid decline in survival at lower NLR values.

4. Discussion

This retrospective study involved 94 dogs and revealed significantly elevated CRP concentrations in dogs with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PH), especially in those at advanced MMVD stages. Additionally, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was positively associated with CRP levels and left atrial (LA) volume, indicating its utility in predicting MMVD severity.

Heart failure has recently been recognized as not only a hemodynamic disorder but also a disorder characterized by inflammatory and immune dysregulation. Inflammation contributes to myocardial injury and complications such as endothelial dysfunction and cardiac cachexia [

25]. Neutrophils release inflammatory mediators that may damage the vascular endothelium, whereas lymphopenia, potentially caused by elevated corticosteroids or neurohormonal shifts in heart failure, is associated with poor outcomes. In dogs, reductions in total lymphocyte counts and lymphocyte subsets have been observed more frequently in canine patients with severe CHF. Platelets also participate in the inflammatory cascade and thrombus formation, particularly in conditions such as mitral valve disease, where altered flow dynamics can influence platelet behavior.

Unlike isolated leukocyte counts, the CRP level and the NLR are less affected by confounding variables, such as age and body weight, and are more stable indicators of systemic inflammation. Numerous veterinary studies have evaluated CRP in inflammatory and neoplastic conditions, and only recently has attention turned toward its relevance in canine cardiac disease. In this study, increased neutrophil counts and decreased lymphocyte levels (within the normal range) were observed in dogs with MMVD and concurrent PH, contributing to elevated CRP levels and NLRs. The higher average CRP and NLR values observed here may be attributed to the smaller sample size compared with previous reports. Notably, CRP levels were significantly elevated in dogs with PH, in agreement with findings from human heart failure studies, where CRP is considered a prognostic factor. When hematological parameters across MMVD stages were compared, lymphocyte counts significantly differed between B1 patients and control participants, whereas WBC, neutrophil, and monocyte counts increased in stages C and D compared with earlier stages. Although the median values in stage C remained within reference limits, leukocytosis and neutrophilia in stage D suggest systemic inflammation in late-stage disease. These findings align with earlier studies using the ISACHC classification, which have shown that leukocyte parameters are elevated in more advanced stages of heart failure.

Compared with those in stage B, the CRP level and NLR in stage C increased significantly. While there were no substantial differences between B1 and B2, the NLR differed significantly between stages B and C, reinforcing the association between inflammation and disease progression. This finding aligns with the literature linking elevated CRP levels and NLRs with worsening cardiac conditions [

26,

27,

28]. Compared with individual cell counts, the greater predictive power of CRP suggests its potential as a biomarker in dogs with MMVD complicated by PH. Pulmonary edema, a severe consequence of CHF, results from increased capillary pressure and disruption of the capillary barrier, leading to the release of inflammatory mediators. In this study, the CRP level and NLR were significantly greater in dogs with pulmonary edema, indicating acute alveolar inflammation, which may exacerbate tissue damage. These findings support the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of MMVD.

Moderate correlations exist between CRP levels, the NLR, and LA volume, supporting their involvement in cardiac remodeling. While CRP in humans is strongly linked to LA volume, this study confirmed a similar trend in dogs. Additionally, weak but significant correlations were observed between the NLR and both the VHS and LA/Ao ratios. Unlike previous studies, our data revealed correlations between the NLR and the MLR and fractional shortening (FS), suggesting a relationship with systolic function. These findings highlight CRP levels and the NLR as potential markers of myocardial injury and structural remodeling in MMVD. Although the specificity of the CRP level and NLR was high according to the results of the ROC curve analysis, the sensitivity of these parameters was limited, indicating that the risk of underdiagnosis of PH is low if these parameters are used in isolation. Nevertheless, when used in conjunction with established diagnostics, the CRP level provides additional value in assessing MMVD severity while minimizing false positives.

This study highlights the role of C-reactive protein (CRP) as a potential inflammatory biomarker associated with pulmonary artery hypertension (PH) in dogs. The significantly elevated CRP levels in dogs with PH suggest a strong inflammatory component in the pathophysiology of PH in canine patients. In contrast, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) did not significantly differ between dogs with and without PH or across ACVIM stages, indicating that the NLR may be less sensitive or influenced by other noncardiac factors.

The progressive increase in CRP concentrations across ACVIM stages also suggests that systemic inflammation worsens with the progression of heart disease, especially in end-stage heart failure (Stage D). However, owing to the variability and lack of statistical significance in CRP levels among these stages, further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to confirm these observations. Overall, compared with the NLR, the CRP level appears to be a more reliable marker for evaluating inflammation in dogs with heart disease, particularly those complicated by pulmonary hypertension.

The results of the ROC analysis highlight the differential diagnostic value of the CRP level and the NLR in this study population. The CRP curve yielded an AUC of 0.7517, reflecting a moderate ability to discriminate between affected and nonaffected individuals. The significant P value (<0.001) further supports the potential role of CRP as a useful inflammatory biomarker in clinical diagnosis. These findings are consistent with previous reports that have established CRP as a sensitive marker for systemic inflammation and disease severity.

In contrast, the NLR curve had an AUC close to 0.5 (0.5568), which is only slightly better than chance, and the lack of statistical significance (P = 0.3976) suggests that the NLR may not be a reliable standalone biomarker in this context. While the NLR has been reported to be a prognostic indicator in several human and veterinary conditions, its diagnostic utility may be limited by overlapping values between diseased and control groups, individual variability, or the influence of confounding factors such as stress or concurrent infections. Overall, CRP appears to be a more robust indicator in this study population, whereas the NLR may require combination with other markers or contextual interpretation to be clinically useful.

Survival analysis using Kaplan‒Meier curves further demonstrated that both the CRP level and the NLR are associated with overall survival, with higher values linked to decreased survival probabilities. Interestingly, patients without pulmonary hypertension (non-PH) had consistently worse survival outcomes at lower levels of both biomarkers than those with pulmonary hypertension. These counterintuitive findings may suggest that the non-PH group may have other undetected pathologies, leading to poor outcomes despite lower inflammatory marker levels. Alternatively, PH patients may have received more intensive monitoring or treatment, improving survival despite having higher CRP levels or NLRs. These findings support the use of CRP and the NLR as prognostic indicators but also highlight the need to consider underlying patient conditions when biomarker levels are interpreted.

Research on the role of CRP in canine MMVD is still emerging, although recent investigations have advanced our understanding [

29,

30]. Subclassifying MMVD stages into C and D enabled a more precise analysis of the diagnostic and prognostic role of CRP and the NLR. In this study, their relationships with pulmonary edema were also assessed, suggesting their relevance as prognostic indicators. In feline cardiology, the NLR has been shown to be correlated with shorter survival in feline patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and is considered an independent prognostic factor. Our findings provide novel evidence supporting the use of CRP levels and the NLR as predictors of PH in dogs with MMVD. Given the need for practical and affordable diagnostic tools in clinical settings, especially where comprehensive testing is limited, CRP and the NLR may prove highly beneficial. A key limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which may introduce inherent biases.

4. Limitation

A limitation of the present study is that only a small number of dogs in stages B1 and D were included. In addition, the average age of the dog population in this study was old; further study with a larger sample size is needed, and some data, e.g., systemic illness, BCS, and oxidative stress level, may help to reflect the correlation between inflammatory status and cardiac status. Moreover, we did not validate inflammatory protein expression in these dogs with MMVD using experiments such as Western blotting or proteomics. In addition, we are unable to control the environment and nutrition in these populations, which is a limitation of our study.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed significantly elevated CRP levels and NLRs in dogs with MMVD complicated by PH, with values increasing in parallel with disease progression. Dogs presenting pulmonary edema, a common complication of MMVD, had even higher inflammatory ratios. Both the CRP level and the NLR were moderately correlated with left atrial volume and were valuable for identifying the severity of MMVD. Moreover, elevated levels of these biomarkers were associated with reduced survival, indicating their prognostic value. As inexpensive, accessible markers, CRP and the NLR may be valuable tools for diagnosing and monitoring MMVD with PH, particularly when conventional tests are delayed or unavailable because of financial, compliance, or emergency constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P.; methodology, C.P., S.S., R.T., K.S., S.H., and S.P.; software, C.P. and S.P.; validation, S.P.; formal analysis, S.P.; investigation, C.P., S.S., R.T., K.S., S.H., and S.P.; software, C.P. and S.P.; resources, S.P.; data curation, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, S.P.; visualization, S.P.; supervision, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Kasetsart University, Thailand

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owner of all animals involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Kasetsart University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University, and Thonglor Pet Hospital for providing facilities for the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Atkins, C.E.; Häggström, J. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Chronic Valvular Heart Disease in Dogs. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2009, 11, S93–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgarelli, M.; Buchanan, J.W. Historical Review, Epidemiology and Natural History of Degenerative Mitral Valve Disease. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2012, 14, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L. Diagnosis of Pulmonary Hypertension in Dogs: Echocardiography and Beyond. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2010, 40, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, L.C.; Im, M.K.; Johnson, L.R.; Stern, J.A. Diagnostic Value of Pulmonary Artery/Aorta Ratio Determined by Echocardiography in Dogs with Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellihan, H.B.; Stepien, R.L. Pulmonary Hypertension in Dogs: Diagnosis and Therapy. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2010, 40, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellihan, H.B.; MacDonald, K.A. Echocardiographic Assessment of Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Dogs: Evaluation of a Ratio of Pulmonary Artery to Aortic Diameter. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yndestad, A.; Damås, J.K.; Oie, E.; Ueland, T.; Gullestad, L.; Aukrust, P. Systemic Inflammation in Heart Failure—The Role of Chemokines and Cytokines. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 70, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijter, J.P.G.; Pulskens, W.P.; Schroen, B.; et al. Inflammatory Responses and Cardiac Repair after Myocardial Infarction: Role of Inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014, 11, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeProspero, D. J. , Hess, R. S., & Silverstein, D. C. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is increased in dogs with acute congestive heart failure secondary to myxomatous mitral valve disease compared to both dogs with heart murmurs and healthy controls. JAVMA. 2023, 261, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, D. , Chae, Y., Kim, C., Koo, Y., Lee, D., Yun, T., Chang, D., Kang, B. T., Yang, M. P., & Kim, H. Severity of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs may be predicted using neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio. Ame. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 84, ajvr.23–01.0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaturk, M. , Saril, A., Oz, A. D., Rubio, C. P., Ceron, J. J., & Yilmaz, Z. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and red blood cell distribution width to platelet ratio and their relationships with inflammatory and antioxidant status in dogs with different stages of heart failure due to myxomatous mitral valve disease. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 2477–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domanjko Petrič, A. , Lukman, T., Verk, B., & Nemec Svete, A. (2018). Systemic inflammation in dogs with advanced-stage heart failure. Acta Vet. Scand. 2018, 60, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, C. P. , Saril, A., Kocaturk, M., Tanaka, R., Koch, J., Ceron, J. J., & Yilmaz, Z. Changes of inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers in dogs with different stages of heart failure. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasmans, M.; Smets, P.; Van den Broeck, W.; et al. C-Reactive Protein as a Marker for Inflammation in Dogs with MMVD. Vet. J. 2015, 203, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Corsi, A.; Lauretani, F.; et al. The Origins of Age-Related Proinflammatory State. Blood 2005, 105, 2294–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.A.; Murphy, S.P.; Mallick, A.; et al. CRP and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: The Framingham Study. Am. Heart J. 2016, 171, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafrir, B.; Salman, N.; Shacham, Y.; et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and CRP in Predicting Long-Term Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2016, 105, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, L.C.; Scansen, B.A.; Schober, K.E.; Bonagura, J.D. Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Atrial Size and Function in Dogs. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2019, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellihan, H.B.; Stepien, R.L. Clinical Characterization of Canine Pulmonary Hypertension: 125 Cases (2001–2011). J. Vet. Cardiol. 2012, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, C. C. , Kittleson, M. D., Della Torre, P., Häggström, J., Lombard, C. W., Pedersen, H. D., Vollmar, A., & Wey, A. Allometric scaling of M-mode cardiac measurements in normal adult dogs J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2004, 18, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, B. W., Atkins, C. E., Bonagura, J. D., Fox, P. R., Häggström, J., Fuentes, V. L., Oyama, M. A., Rush, J. E., Stepien, R., Uechi, M. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs . J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1127–1140. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Staveren, M.D.B.; Muis, E.; Szatmári, V. Self-Reported Utilization of International (ACVIM Consensus) Guidelines and the Latest Clinical Trial Results on the Treatment of Dogs with Various Stages of Myxomatous Mitral Valve Degeneration: A Survey among Veterinary Practitioners. Animals. 2024, 14, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, E.; Ettinger, S.J.; Sisson, D.D. Ettinger’s Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine: Diseases of the Dog and the Cat, 8th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.D.; Badano, L.P.; Appleton, C.P.; DeMaria, A.N.; Doppler Quantitation Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the ASE. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2009, 22, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal-Bianco, J.P.; Beaudoin, J.; Handschumacher, M.D.; Levine, R.A. Basic mechanisms of mitral regurgitation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2014, 30, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. L. , Yang, R., Zhu, Y., Shao, Y., Ji, Y., & Wang, F. F. Association between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and risk of in-hospital heart failure and arrhythmia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1275713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. , Li, D., & Du, Y. Prognostic value of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for cardiovascular diseases: research progress. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2025, 17, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Escobar, A. , Vera-Vera, S. , Tébar-Márquez, D., Rivero-Santana, B., Jurado-Román, A., Jiménez-Valero, S., Galeote, G., Cabrera, J. Á., & Moreno, R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio an inflammatory biomarker, and prognostic marker in heart failure, cardiovascular disease and chronic inflammatory diseases: New insights for a potential predictor of anti-cytokine therapy responsiveness. Microvasc. Res. 2023, 150, 104598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, M. J. , Ljungvall, I., Hillström, A., Møller, J. E., Hagman, R., Falk, T., Höglund, K., Häggström, J., & Olsen, L. H. Increased serum C-reactive protein concentrations in dogs with congestive heart failure due to myxomatous mitral valve disease. Vet. J. 2016, 209, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, D. , Chae, Y., Kim, C., Koo, Y., Lee, D., Yun, T., Chang, D., Kang, B. T., Yang, M. P., & Kim, H. Severity of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs may be predicted using neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 84, ajvr.23–01.0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).