Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

3. The Role of Echocardiography in Assessing Cardiac Geometry

4. Role of Echocardiography in the Assessment of Left Ventricular Systolic Function

5. Evaluation of Pulmonary Congestion Using Lung Ultrasound in Rats

6. Evaluation of RV Geometry and Function and its Association with Pulmonary Hypertension

7. Conventional Assessment of LVEF in Rodent Models

8. Advanced Assessment: Myocardial Deformation (Strain Imaging)

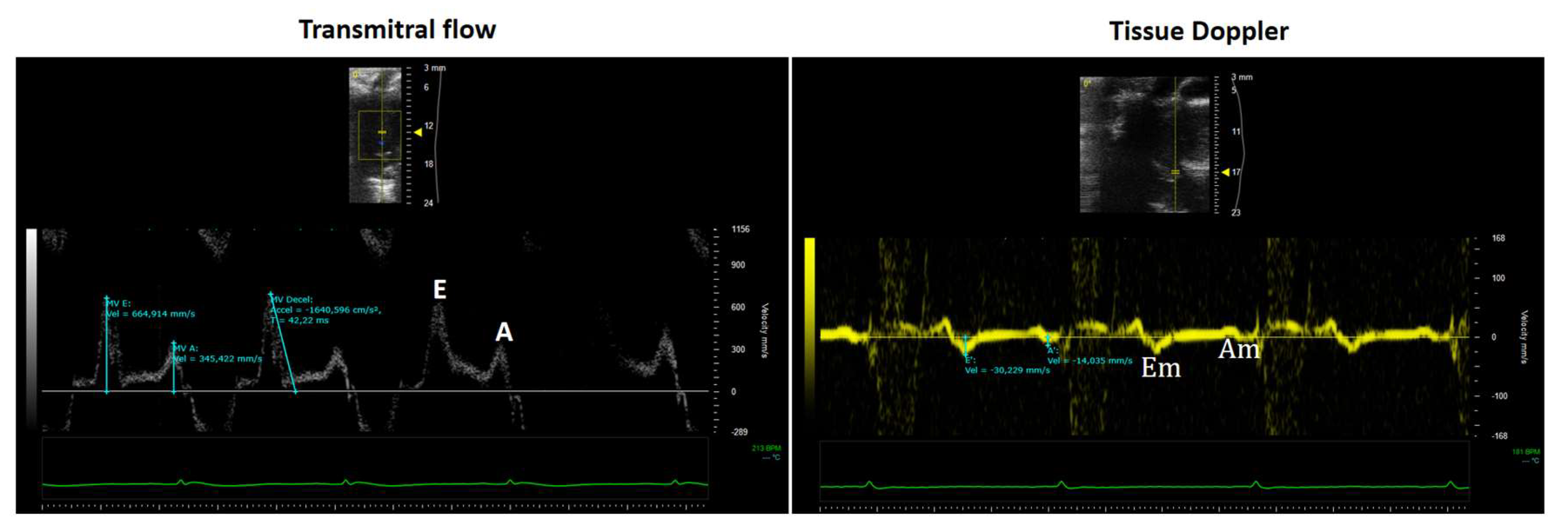

9. Role of Echocardiography in the Assessment of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function

- The E wave represents early diastolic filling driven by the pressure gradient between the left atrium and ventricle.

- The A wave corresponds to atrial contraction and the elastic recoil of the atrium and ventricle during late diastole.

- Mitral Annular Tissue Doppler Imaging (TDI)

- A positive systolic wave (Sm), and

- Two negative diastolic waves: early (Em) and late (Am).

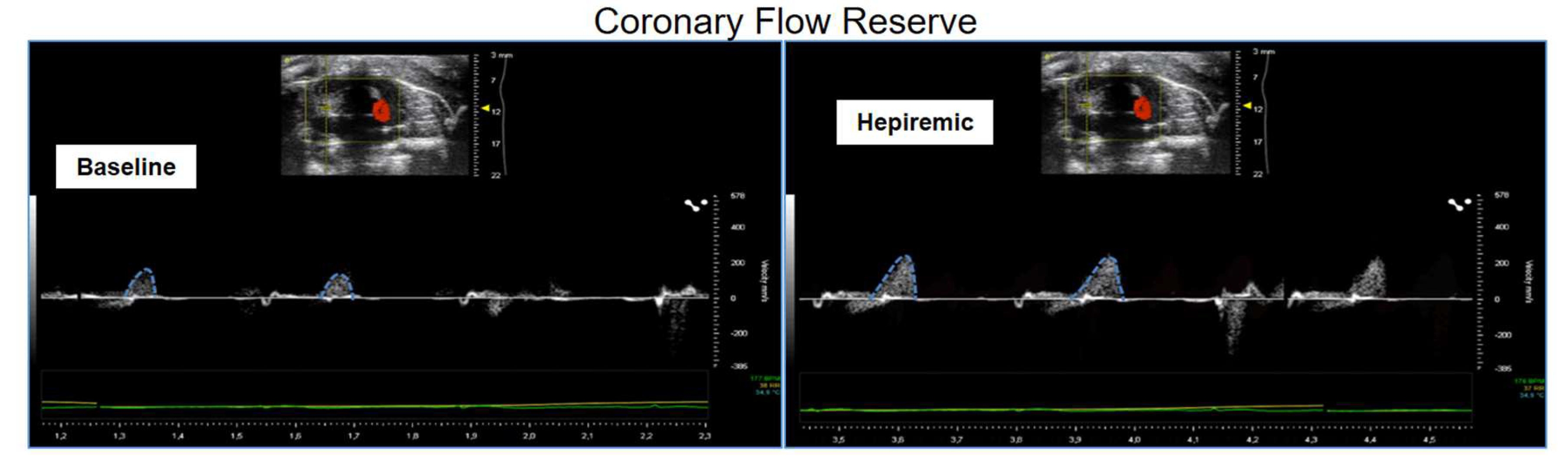

10. Coronary Flow Reserve Assessment in Non-Ischemic Models

11. Challenges in Clinical and Experimental CFR Assessment

Abbreviations

| NIC | Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure preserved ejection fraction |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| IVS | Interventricular septal thickness |

| LVDD | Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter |

| LVPP | Left ventricular posterior wall thickness |

| LA | Left atrium |

| PC | Pulmonary congestion |

| BNP | Natriuretic peptide |

| W/D ratio | wet-to-dry weight ratio of the lung |

| LU | Lung ultrasound |

| RV | Right Ventricle |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| DTI | Doppler tissue imaging |

| ARVC | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| PKG | Protein kinase G |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| PAH | pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| STR | Secondary tricuspid regurgitation |

| TAPSE | Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure reduced ejection fraction |

| FS | Fractional shortening |

| 2D-STE | Two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography |

| PEL | Parasternal long-axis |

| PES | Parasternal short-axis |

| GLS | Global longitudinal strain |

| GRS | Global radial strain |

| GCS | Global circumferential strain |

| Tau | time constant of relaxation |

| DT | Deceleration time |

| IVRT | Isovolumetric relaxation |

| TDI | Mitral annular tissue doppler imaging |

| CFR | Coronary flow reserve |

References

- Chang, A.; Cadaret, L.M.; Liu, K. Machine Learning in Electrocardiography and Echocardiography: Technological Advances in Clinical Cardiology. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2020, 22, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumo, M. Value of Echocardiography in the Treatment of Patients With Acute Heart Failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 740439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, R.M.; Khan, I.A.; Vasavada, B.C.; Sacchi, T.J.; Patel, R. History of the Evolution of Echocardiography. Int. J. Cardiol. 2004, 97, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigenbaum, H. Evolution of Echocardiography. Circulation 1996, 93, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Goyal, A. The Origin of Echocardiography: A Tribute to Inge Edler. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2007, 34, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Edler, I.; Lindström, K. The History of Echocardiography. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2004, 30, 1565–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, V.K.; Sengupta, P.P.; Gentile, F.; Khandheria, B.K. History of Echocardiography and Its Future Applications in Medicine: Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, S309–S313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, L.D.; Marcoff, L. Echocardiography: Past, Present, and Future. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.G.; Mukherjee, M.; Dala, P.; Young, H.A.; Tracy, C.M.; Katz, R.J.; Lewis, J.F. Interpretation of Remotely Downloaded Pocket-Size Cardiac Ultrasound Images on a Web-Enabled Smartphone: Validation Against Workstation Evaluation. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2011, 24, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reef, V.B. Advances in Echocardiography. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 1991, 7, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, R.; Mickelsen, D.M.; Theodoropoulos, C.; Blaxall, B.C. New Approaches in Small Animal Echocardiography: Imaging the Sounds of Silence. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H1765–H1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Chang, C.-F.; Liu, B.; Gong, C.; Ji, J.; Zhang, B.Z.; Wang, Y.; Xinhu Ren, M.; et al. High-Frequency Wearable Ultrasound Array Belt for Small Animal Echocardiography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2024, 71, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchigna, S.; Paldino, A.; Falcão-Pires, I.; Daskalopoulos, E.P.; Dal Ferro, M.; Vodret, S.; Lesizza, P.; Cannatà, A.; Miranda-Silva, D.; Lourenço, A.P.; et al. Towards Standardization of Echocardiography for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Function in Adult Rodents: A Position Paper of the ESC Working Group on Myocardial Function. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabs, M.; Rose, A.J.; Lehmann, L.H.; Taylor, J.; Moll, I.; Sijmonsma, T.P.; Herberich, S.E.; Sauer, S.W.; Poschet, G.; Federico, G.; et al. Inhibition of Endothelial Notch Signaling Impairs Fatty Acid Transport and Leads to Metabolic and Vascular Remodeling of the Adult Heart. Circulation 2018, 137, 2592–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, S.-G.; Lee, W.H.; Huang, M.; Dey, D.; Kodo, K.; Sanchez-Freire, V.; Gold, J.D.; Wu, J.C. Cross Talk of Combined Gene and Cell Therapy in Ischemic Heart Disease: Role of Exosomal MicroRNA Transfer. Circulation 2014, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, X.; Fassett, J.; Kwak, D.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Falls, T.J.; Bell, J.C.; Li, H.; Bitterman, P.; et al. Double-Stranded RNA–Dependent Protein Kinase Deficiency Protects the Heart From Systolic Overload-Induced Congestive Heart Failure. Circulation 2014, 129, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, R.A.; Iekushi, K.; Lechner, S.; Seeger, T.; Fischer, A.; Heydt, S.; Kaluza, D.; Tréguer, K.; Carmona, G.; Bonauer, A.; et al. MicroRNA-34a Regulates Cardiac Ageing and Function. Nature 2013, 495, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, M.L.; Bolli, R.; Canty, J.M.; Du, X.-J.; Frangogiannis, N.G.; Frantz, S.; Gourdie, R.G.; Holmes, J.W.; Jones, S.P.; Kloner, R.A.; et al. Guidelines for Experimental Models of Myocardial Ischemia and Infarction. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H812–H838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, M.L.; Kassiri, Z.; Virag, J.A.I.; De Castro Brás, L.E.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M. Guidelines for Measuring Cardiac Physiology in Mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H733–H752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachon, R.E.; Scharf, B.A.; Vatner, D.E.; Vatner, S.F. Best Anesthetics for Assessing Left Ventricular Systolic Function by Echocardiography in Mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H1525–H1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, D.G.; Kiriazis, H.; Du, X.-J.; Marwick, T.H.; McMullen, J.R. Improving the Quality of Preclinical Research Echocardiography: Observations, Training, and Guidelines for Measurement. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H58–H70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, D.M.; Romano, M.M.D.; Carvalho, E.E.V.; Oliveira, L.F.L.; Souza, H.C.D.; Maciel, B.C.; Salgado, H.C.; Fazan-Júnior, R.; Simões, M.V. Effect of Different Anesthetic Agents on Left Ventricular Systolic Function Assessed by Echocardiography in Hamsters. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, e5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzi, L.; Buongiorno, F.; Narciso, V.; Florimonte, D.; Forzano, I.; Castiello, D.S.; Sperandeo, L.; Paolillo, R.; Verde, N.; Spinelli, A.; et al. Acute Heart Failure and Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathies: A Comprehensive Review and Critical Appraisal. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barja, N.; Rozado, J.; Martín, M. Ischemic or Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy? JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, H.; Song, J. Accurate Classification of Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1299–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Kesteven, S.; Wu, J.; Aidery, P.; Gawaz, M.; Gramlich, M.; Feneley, M.P.; Harvey, R.P. Pressure Overload by Transverse Aortic Constriction Induces Maladaptive Hypertrophy in a Titin-Truncated Mouse Model. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, Y.; Mano, T.; Sakata, Y.; Ohtani, T.; Takeda, Y.; Tamaki, S.; Omori, Y.; Ikeya, Y.; Saito, Y.; Ishii, R.; et al. A Novel Heart Failure Mice Model of Hypertensive Heart Disease by Angiotensin II Infusion, Nephrectomy, and Salt Loading. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 305, H1658–H1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carll, A.P.; Willis, M.S.; Lust, R.M.; Costa, D.L.; Farraj, A.K. Merits of Non-Invasive Rat Models of Left Ventricular Heart Failure. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2011, 11, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doris, P.A. Genetics of Hypertension: An Assessment of Progress in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat. Physiol. Genomics 2017, 49, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredersdorf, S.; Thumann, C.; Ulucan, C.; Griese, D.P.; Luchner, A.; Riegger, G.A.J.; Kromer, E.P.; Weil, J. Myocardial Hypertrophy and Enhanced Left Ventricular Contractility in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2004, 13, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Gorodny, N.; Gomez, L.F.; Gangadharmath, U.; Mu, F.; Chen, G.; Walsh, J.C.; Szardenings, K.; Kolb, H.C.; Tamarappoo, B. Noninvasive Molecular Imaging of Apoptosis in a Mouse Model of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leerink, J.M.; Van De Ruit, M.; Feijen, E.A.M.; Kremer, L.C.M.; Mavinkurve-Groothuis, A.M.C.; Pinto, Y.M.; Creemers, E.E.; Kok, W.E.M. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Animal Models of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiomyopathy: A Meta-Analysis. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 99, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, B.L. Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Models in Mice and Rats. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gounarides, J.S.; Korach-André, M.; Killary, K.; Argentieri, G.; Turner, O.; Laurent, D. Effect of Dexamethasone on Glucose Tolerance and Fat Metabolism in a Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, J.L.; Romano, M.M.D.; Campos Pulici, E.C.; Carvalho, E.E.V.; De Souza, F.R.; Tanaka, D.M.; Maciel, B.C.; Salgado, H.C.; Fazan-Júnior, R.; Rossi, M.A.; et al. Short-Term and Long-Term Models of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy in Rats: A Comparison of Functional and Histopathological Changes. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 69, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, E.C.; Romano, M.M.D.; Prado, C.M.; Rossi, M.A. Isoproterenol Induces Primary Loss of Dystrophin in Rat Hearts: Correlation with Myocardial Injury. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2008, 89, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouanes-Besbes, L.; El Atrous, S.; Nouira, S.; Aubrey, N.; Carayon, A.; El Ayeb, M.; Abroug, F. Direct vs. Mediated Effects of Scorpion Venom: An Experimental Study of the Effects of a Second Challenge with Scorpion Venom. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, L.E.; Lages-Silva, E.; Soares Junior, J.M.; Chapadeiro, E. The Hamster (Mesocricetus Auratus) as Experimental Model in Chagas’ Disease: Parasitological and Histopathological Studies in Acute and Chronic Phases of Trypanosoma Cruzi Infection. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 1994, 27, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Thibault, H.B. Echocardiography in Translational Research: Of Mice and Men. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2008, 21, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, S.E.; Katz, S.E.; Weinberg, E.O.; Lorell, B.H.; Aurigemma, G.P.; Douglas, P.S. Serial Echocardiographic-Doppler Assessment of Left Ventricular Geometry and Function in Rats With Pressure-Overload Hypertrophy: Chronic Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibition Attenuates the Transition to Heart Failure. Circulation 1995, 91, 2642–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduch, M.C.D.; Assad, R.S.; Mathias Jr., W.; Aiello, V.D. The Echocardiography in the Cardiovascular Laboratory: A Guide to Research with Animals. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, H.; Cooper, R.; George, K.P.; Augustine, D.X.; Malhotra, A.; Paton, M.F.; Robinson, S.; Oxborough, D. The Athlete’s Heart: Insights from Echocardiography. Echo Res. Pract. 2023, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, A.; Oláh, A.; Lux, Á.; Mátyás, C.; Németh, B.T.; Kellermayer, D.; Ruppert, M.; Török, M.; Szabó, L.; Meltzer, A.; et al. Strain and Strain Rate by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography Correlate with Pressure-Volume Loop-Derived Contractility Indices in a Rat Model of Athlete’s Heart. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H743–H748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manca, P.; Nuzzi, V.; Cannatà, A.; Merlo, M.; Sinagra, G. Contemporary Etiology and Prognosis of Dilated Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2022, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jiang, Y.-P.; Cohen, I.S.; Lin, R.Z.; Mathias, R.T. Pressure-Overload-Induced Angiotensin-Mediated Early Remodeling in Mouse Heart. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0176713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D.; Gil, A.; Gómez, J.; Ruiz, L.; Llano, M.; García, R.; Hurlé, M.A.; Nistal, J.F. Experimental Modelling of Cardiac Pressure Overload Hypertrophy: Modified Technique for Precise, Reproducible, Safe and Easy Aortic Arch Banding-Debanding in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, D.L.; Goldstein, B.M.; Lizzo, F.H.; Lozito, R.J.; Cervoni, P. Development of an Animal Model for Investigating Disparate Myocardial Effects of Obesity and Hypertension. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988, 64, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, E.D.; Susic, D. Pressure Overload. Heart Fail. Clin. 2012, 8, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S. Regression of Cardiac Hypertrophy Experimental Animal Model. Am. J. Med. 1983, 75, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.M.; Rolett, E.L. Heart Failure: When Form Fails to Follow Function. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, H.; Kuwahara, F.; Tokuda, K.; Imaizumi, T. Diastolic Dysfunction in Hypertensive Hearts: Roles of Perivascular Inflammation and Reactive Myocardial Fibrosis. Hypertens. Res. 2005, 28, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite-Moreira, A. Afterload Induced Changes in Myocardial Relaxation A Mechanism for Diastolic Dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999, 43, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Samaan, K.; Asfour, A.; Baghdady, Y.; Samaan, A.A. Ventricular Remodeling and Hemodynamic Changes in Heart Failure Patients with Non-Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy Following Dapagliflozin Initiation. Egypt. Heart J. 2024, 76, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereux, R.B.; De Simone, G.; Ganau, A.; Koren, M.J.; Mensah, G.A.; Roman, M.J. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 1993, 15, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, G.; Hermosillo-Rodriguez, J.; Pham, T.; Granillo, A.; Hartley, C.J.; Reddy, A.; Osuna, P.M.; Entman, M.L.; Taffet, G.E. Left Atrial Volume and Pulmonary Artery Diameter Are Noninvasive Measures of Age-Related Diastolic Dysfunction in Mice. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishniw, M.; Erb, H.N. Evaluation of Four 2-Dimensional Echocardiographic Methods of Assessing Left Atrial Size in Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2000, 14, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichholz, L.E.; Kreulen, T.; Herman, M.V.; Gorlin, R. Problems in Echocardiographic Volume Determinations: Echocardiographic-Angiographic Correlations in the Presence or Absence of Asynergy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1976, 37, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, D.M.; O’Connell, J.L.; Fabricio, C.G.; Romano, M.M.D.; Campos, E.C.; Oliveira, L.F.L.D.; Schmidt, A.; Carvalho, E.E.V.D.; Simões, M.V. Efficacy of Different Cumulative Doses of Doxorubicin in the Induction of a Dilated Cardiomyopathy Model in Rats. ABC Heart Fail. Cardiomyopathy 2022, 2, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Gheorghiade, M.; Triposkiadis, F.; Solomon, S.D.; Pieske, B.; Butler, J. Left Atrium in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Structure, Function, and Significance. Circ. Heart Fail. 2014, 7, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.S.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, C.M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Böhm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 352–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição, G.; Heinonen, I.; Lourenço, A.P.; Duncker, D.J.; Falcão-Pires, I. Animal Models of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Neth. Heart J. 2016, 24, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.C.; Townsley, M.I. Evaluation of Lung Injury in Rats and Mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004, 286, L231–L246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacher, P.; Nagayama, T.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Bátkai, S.; Kass, D.A. Measurement of Cardiac Function Using Pressure–Volume Conductance Catheter Technique in Mice and Rats. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigendum to: Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Humans and Mice: Embracing Clinical Complexity in Mouse Models. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 1940–1940. [CrossRef]

- Picchi, M.G.; Mattos, A.M.D.; Barbosa, M.R.; Duarte, C.P.; Gandini, M.D.A.; Portari, G.V.; Jordão, A.A. A High-Fat Diet as a Model of Fatty Liver Disease in Rats. Acta Cir. Bras. 2011, 26, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J.R. Use of High-Fat Diets to Study Rodent Obesity as a Model of Human Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1491–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiske, B.L.; O’Donnell, M.P.; Keane, W.F. The Zucker Rat Model of Obesity, Insulin Resistance, Hyperlipidemia, and Renal Injury. Hypertension 1992, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, J.A.; Mauro, A.G.; Carbone, S.; Marchetti, C.; Gill, R.; Mezzaroma, E.; Valle Raleigh, J.; Salloum, F.N.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Abbate, A.; et al. A Mouse Model of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Due to Chronic Infusion of a Low Subpressor Dose of Angiotensin II. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 309, H771–H778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Huang, D.; Zhang, M.; Huang, X.; Ma, S.; Mao, S.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L. Lung Ultrasound Is a Reliable Method for Evaluating Extravascular Lung Water Volume in Rodents. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015, 15, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, S.; Gavazzi, A.; Campana, C.; Inserra, C.; Klersy, C.; Sebastiani, R.; Arbustini, E.; Recusani, F.; Tavazzi, L. Independent and Additive Prognostic Value of Right Ventricular Systolic Function and Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, F.; Doyle, R.; Murphy, D.J.; Hunt, S.A. Right Ventricular Function in Cardiovascular Disease, Part II: Pathophysiology, Clinical Importance, and Management of Right Ventricular Failure. Circulation 2008, 117, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorter, T.M.; Hoendermis, E.S.; Van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Voors, A.A.; Lam, C.S.P.; Geelhoed, B.; Willems, T.P.; Van Melle, J.P. Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 1472–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longobardo, L.; Suma, V.; Jain, R.; Carerj, S.; Zito, C.; Zwicke, D.L.; Khandheria, B.K. Role of Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography Strain in the Assessment of Right Ventricular Systolic Function and Comparison with Conventional Parameters. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 937–946.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addetia, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Amuthan, V.; Citro, R.; Daimon, M.; Gutierrez Fajardo, P.; Kasliwal, R.R.; Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Monaghan, M.J.; Muraru, D.; et al. Normal Values of Three-Dimensional Right Ventricular Size and Function Measurements: Results of the World Alliance Societies of Echocardiography Study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2023, 36, 858–866.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresian, H. The Clinical Anatomy of the Right Ventricle. Clin. Anat. 2016, 29, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Veerdonk, M.C.; Marcus, J.T.; Bogaard, H.; Noordegraaf, A.V. State of the Art: Advanced Imaging of the Right Ventricle and Pulmonary Circulation in Humans (2013 Grover Conference Series). Pulm. Circ. 2014, 4, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudski, L.G.; Lai, W.W.; Afilalo, J.; Hua, L.; Handschumacher, M.D.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Solomon, S.D.; Louie, E.K.; Schiller, N.B. Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Heart in Adults: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 685–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, L.E.P.; Montera, M.W.; Bocchi, E.A.; Clausell, N.O.; Albuquerque, D.C.D.; Rassi, S.; Colafranceschi, A.S.; Freitas Junior, A.F.D.; Ferraz, A.S.; Biolo, A.; et al. Diretriz Brasileira de Insuficiência Cardíaca Crônica e Aguda. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.Y.T.; Meyer, D.M.; Tazelaar, H.D.; Grande, J.P.; Burnett Jr, J.C.; Housmans, P.R.; Redfield, M.M. Load Versus Humoral Activation in the Genesis of Early Hypertensive Heart Disease. Circulation 2001, 104, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A Novel Paradigm for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirinos, J.A.; Segers, P.; Gupta, A.K.; Swillens, A.; Rietzschel, E.R.; De Buyzere, M.L.; Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Gillebert, T.C.; Wang, Y.; Keane, M.G.; et al. Time-Varying Myocardial Stress and Systolic Pressure-Stress Relationship: Role in Myocardial-Arterial Coupling in Hypertension. Circulation 2009, 119, 2798–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taube, A.; Schlich, R.; Sell, H.; Eckardt, K.; Eckel, J. Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction: Links to Cardiovascular Diseases. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H2148–H2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Heerebeek, L.; Hamdani, N.; Falcão-Pires, I.; Leite-Moreira, A.F.; Begieneman, M.P.V.; Bronzwaer, J.G.F.; Van Der Velden, J.; Stienen, G.J.M.; Laarman, G.J.; Somsen, A.; et al. Low Myocardial Protein Kinase G Activity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2012, 126, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, A.; Thaik, C.M.; Takahashi, N.; Chang, D.L.; Colucci, W.S. Nitric Oxide, Atrial Natriuretic Peptide, and Cyclic GMP Inhibit the Growth-Promoting Effects of Norepinephrine in Cardiac Myocytes and Fibroblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 101, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takimoto, E.; Champion, H.C.; Li, M.; Belardi, D.; Ren, S.; Rodriguez, E.R.; Bedja, D.; Gabrielson, K.L.; Wang, Y.; Kass, D.A. Chronic Inhibition of Cyclic GMP Phosphodiesterase 5A Prevents and Reverses Cardiac Hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassis, N.; Layoun, H.; Goyal, A.; Dong, T.; Saad, A.M.; Puri, R.; Griffin, B.P.; Heresi, G.A.; Tonelli, A.R.; Kapadia, S.R.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into Tricuspid Regurgitation Secondary to Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 175, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, J.P.; Heallen, T.; Zhang, M.; Rahmani, M.; Morikawa, Y.; Hill, M.C.; Segura, A.; Willerson, J.T.; Martin, J.F. Hippo Pathway Deficiency Reverses Systolic Heart Failure after Infarction. Nature 2017, 550, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, Y.; Canseco, D.C.; Thet, S.; Abdisalaam, S.; Asaithamby, A.; Santos, C.X.; Shah, A.M.; Zhang, H.; Faber, J.E.; Kinter, M.T.; et al. Hypoxia Induces Heart Regeneration in Adult Mice. Nature 2017, 541, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heerebeek, L.; Paulus, W.J. Understanding Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Where Are We Today? Neth. Heart J. 2016, 24, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, D.; Lindner, D.; Kasner, M.; Zietsch, C.; Savvatis, K.; Escher, F.; Von Schlippenbach, J.; Skurk, C.; Steendijk, P.; Riad, A.; et al. Cardiac Inflammation Contributes to Changes in the Extracellular Matrix in Patients With Heart Failure and Normal Ejection Fraction. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.D.; MacPhail, B.; Harrison, M.R.; Lenhoff, S.J.; DeMaria, A.N. Value and Limitations of Transesophageal Echocardiography in Determination of Left Ventricular Volumes and Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 19, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottdiener, J.S. Overview of Stress Echocardiography: Uses, Advantages, and Limitations. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2003, 28, 485–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Omae, Y.; Harada, T.; Sorimachi, H.; Yuasa, N.; Kagami, K.; Murakami, F.; Naito, A.; Tani, Y.; Kato, T.; et al. Exercise Stress Echocardiography–Based Phenotyping of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2024, 37, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, S.W.; Ferrara, J.; Chalian, A.; Tighe, D.A.; Aurigemma, G.P.; Goldberg, R.J. Are Ejection Fraction Measurements by Echocardiography and Left Ventriculography Equivalent? Am. Heart J. 2009, 158, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.W.; Choy, J.B.; Nanda, N.C.; Becher, H. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction and Volumes: It Depends on the Imaging Method. Echocardiography 2014, 31, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Kagami, K.; Kato, T.; Obokata, M. Echocardiography in the Diagnostic Evaluation and Phenotyping of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, V.T.; Rassi, D.D.C.; Pena, J.L.B.; Vieira, M.L.C.; Rodrigues, A.C.T.; Cardoso, J.N.; Ramires, F.J.A.; Nastari, L.; Mady, C.; Fernandes, F. Análise Crítica e Limitações Do Diagnóstico de Insuficiência Cardíaca Com Fração de Ejeção Preservada (ICFEp). Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loai, S.; Cheng, H.-L.M. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: The Missing Pieces in Diagnostic Imaging. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 25, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorcsan, J.; Tanaka, H. Echocardiographic Assessment of Myocardial Strain. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1401–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, F.; Jamal, F.; Sutherland, G.R.; Claus, P.; Kowalski, M.; Hatle, L.; De Scheerder, I.; Bijnens, B.; Rademakers, F.E. Myocardial Function Defined by Strain Rate and Strain during Alterations in Inotropic States and Heart Rate. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002, 283, H792–H799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, J.-U.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Lysyansky, P.; Marwick, T.H.; Houle, H.; Baumann, R.; Pedri, S.; Ito, Y.; Abe, Y.; Metz, S.; et al. Definitions for a Common Standard for 2D Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: Consensus Document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to Standardize Deformation Imaging. Eur. Heart J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiseth, O.A.; Rider, O.; Cvijic, M.; Valkovič, L.; Remme, E.W.; Voigt, J.-U. Myocardial Strain Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 18, 340–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, J.-U.; Cvijic, M. 2- and 3-Dimensional Myocardial Strain in Cardiac Health and Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijnens, B.H.; Cikes, M.; Claus, P.; Sutherland, G.R. Velocity and Deformation Imaging for the Assessment of Myocardial Dysfunction. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2008, 10, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.W.; So, E.K.; Wong, W.H.; Cheung, Y. Myocardial Deformation Imaging by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography for Assessment of Cardiotoxicity in Children during and after Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 629–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Phelan, D.; Klein, A. A Test in Context: Myocardial Strain Measured by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitia, S. Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: A New Approach to Myocardial Function. World J. Cardiol. 2010, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquatella, H. Echocardiography in Chagas Heart Disease. Circulation 2007, 115, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, S.A.M.; Chetrit, M.; Jankowski, M.; Desai, M.; Falk, R.H.; Weiner, R.B.; Klein, A.L.; Phelan, D.; Grogan, M. Practical Points for Echocardiography in Cardiac Amyloidosis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, A31–A40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, W.C.; Oh, J.K. Echocardiographic Evaluation of Diastolic Function Can Be Used to Guide Clinical Care. Circulation 2009, 120, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleton, C.P.; Hatle, L.K.; Popp, R.L. Relation of Transmitral Flow Velocity Patterns to Left Ventricular Diastolic Function: New Insights from a Combined Hemodynamic and Doppler Echocardiographic Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1988, 12, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvagh, S.; Quin̄ones, M.A.; Kleiman, N.S.; Jorge Cheirif, B.; Zoghbi, W.A. Estimation of Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Pressure from Doppler Transmitral Flow Velocity in Cardiac Patients Independent of Systolic Performance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 20, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleton, C.P.; Firstenberg, M.S.; Garcia, M.J.; Thomas, J.D. THE ECHO-DOPPLER EVALUATION OF LEFT VENTRICULAR DIASTOLIC FUNCTION. Cardiol. Clin. 2000, 18, 513–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, M.; Dini, F.L.; Temporelli, P.L.; Colonna, P.; de Simone, G. [Doppler echocardiography for the assessment of left ventricular diastolic function: methodology, clinical and prognostic value]. Ital. Heart J. Suppl. Off. J. Ital. Fed. Cardiol. 2004, 5, 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Middleton, K.J.; Kopelen, H.A.; Zoghbi, W.A.; Quiñones, M.A. Doppler Tissue Imaging: A Noninvasive Technique for Evaluation of Left Ventricular Relaxation and Estimation of Filling Pressures. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 30, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yip, G.W.K.; Wang, A.Y.M.; Zhang, Y.; Ho, P.Y.; Tse, M.K.; Lam, P.K.W.; Sanderson, J.E. Peak Early Diastolic Mitral Annulus Velocity by Tissue Doppler Imaging Adds Independent and Incremental Prognostic Value. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.P.; Gould, K.L.; Di Carli, M.F.; Taqueti, V.R. Invasive FFR and Noninvasive CFR in the Evaluation of Ischemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2772–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taqueti, V.R.; Shah, A.M.; Everett, B.M.; Pradhan, A.D.; Piazza, G.; Bibbo, C.; Hainer, J.; Morgan, V.; Carolina Do A., H. De Souza, A.; Skali, H.; et al. Coronary Flow Reserve, Inflammation, and Myocardial Strain. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2023, 8, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, C.J.; Berry, C.; Oldroyd, K.G.; Rocchiccioli, J.P.; Lindsay, M.M.; Touyz, R.M.; Murphy, C.L.; Ford, T.J.; Sidik, N.; McEntegart, M.B.; et al. Prevalence of Coronary Artery Disease and Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taqueti, V.R.; Di Carli, M.F. Coronary Microvascular Disease Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2625–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, J.R.; Kanagala, P.; Budgeon, C.A.; Jerosch-Herold, M.; Gulsin, G.S.; Singh, A.; Khan, J.N.; Chan, D.C.S.; Squire, I.B.; Ng, L.L.; et al. Prevalence and Prognostic Significance of Microvascular Dysfunction in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryer, K.; Gajjar, M.; Narang, N.; Lee, M.; Paul, J.; Shah, A.P.; Nathan, S.; Butler, J.; Davidson, C.J.; Fearon, W.F.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H1033–H1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.F.; Hussain, S.; Mirzoyev, S.A.; Edwards, W.D.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Redfield, M.M. Coronary Microvascular Rarefaction and Myocardial Fibrosis in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2015, 131, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, C.; Sykes, R. Microvascular Dysfunction in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1012–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | Wall movement | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal/hyperkinesia | Normal systolic movement and thickening |

| 2 | Hypokinesia | Reduced systolic motion or thickening |

| 3 | Acinese | Absence of systolic inward movement or thickening |

| 4 | Dyskinesia or Aneurysm | Paradoxical (“bulging”) or outward movement |

| Left atrium | Left ventricle | Right ventricle | Overload and congestion |

|---|---|---|---|

| LA volume | IVS | RV basal dimension | Pericardial effusion |

| LA-area | LVDD | (Apical 4-chamber) | B-lines (Lulmonary congestion) |

| LA-diameter | LVSD | Proximal dimension of the RV outflow tract | ICV collapsibility indices |

| Aort-Dimension | PPw | (Parasternal short axis, anterior to the aortic valve) | (Animal breathing spontaneously) |

| Relation LA/Ao | Relative thickness | Fractional area change RV | IVC distensibility indices |

| LV mass | (Apical 4-chamber) | (Animal on mechanical ventilation) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).