1. Introduction

Production scheduling is a strategic function in open-pit mine planning, determining the optimal sequence, timing, and volume of ore and waste extraction throughout the life of mine. Its effectiveness directly influences key performance indicators such as Net Present Value (NPV), operational efficiency, resource recovery, and compliance with environmental and geotechnical constraints [

1,

2,

3]. Historically, deterministic frameworks such as Linear Programming (LP), Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP), and Dynamic Programming (DP) have provided foundational scheduling approaches [

4,

5]. However, these methods often oversimplify operational realities, including precedence, blending, haulage, and processing limits, and are computationally challenging at industrial scale [

2,

6,

7,

8]. Heuristic-based strategies, such as cutoff grade policies, offer speed and simplicity but tend to prioritize short-term gains, neglecting interdependencies and sustainability considerations [

7,

8]. Additionally, conventional models typically assume fixed ore grades, costs, and prices, disregarding uncertainty and treating environmental impacts as externalities—falling short of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) expectations [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Recent advancements have introduced metaheuristics (e.g., Genetic Algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization, Simulated Annealing) [

15,

16], stochastic optimization techniques [

9,

17], and hybrid approaches [

18] capable of modelling uncertainty, multi-objective trade-offs, and large-scale block models. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms such as NSGA-II and SPEA2 enable balancing profitability, environmental compliance, and production stability [

19,

20,

21]. Industry 4.0 innovations—including artificial intelligence, digital twins, reinforcement learning, and agent-based modelling—are further advancing real-time, adaptive scheduling [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Yet, adoption remains limited, particularly for small and mid-tier mines, due to high costs, technical expertise requirements, proprietary licensing, fragmented datasets, and “black box” model opacity [

20,

24,

26,

27,

28].

In response, this study develops a scalable, sustainable, and open-source production scheduling model in Python. Using linear integer programming, the framework integrates environmental penalties directly into block valuations while enforcing operational and geotechnical constraints. It offers a transparent, adaptable, and cost-effective alternative to proprietary tools, supporting both academic research and industry application. By aligning economic, operational, and environmental priorities, the model contributes toward responsible, data-driven, and intelligent mine planning.

2. Materials and Methods

This section details the step-by-step methodology applied in the study. The process begins with the description and preparation of the dataset, followed by the definition of assumptions and constraints, the formulation of the optimization model, the application of solution strategies using selected tools, performance validation, and sensitivity analysis. Together, these components form a robust methodological base for developing an optimization model that is not only mathematically rigorous but also adaptable to diverse mining scenarios.

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The dataset used for this study is a comprehensive block model that replicates the essential geological, economic, and spatial features of an operational open-pit mine. It consists of key attributes, such as block coordinates (X, Y, Z), ore grade in grams per tonne (g/t), weight and volume of blocks, density, and operational metrics, including revenue, operating cost, environmental penalty, and net present value (NPV). These parameters form the core input for developing an optimization framework that can generate practical production schedules. Before deploying the dataset in the optimization model, several preprocessing steps were taken which is key in both academic and real-world applications. First, irrelevant or empty columns were removed to streamline the dataset. Second, null or missing values were checked and found to be negligible, ensuring data completeness. The economic parameters, such as revenue and NPV, were retained to benchmark model performance and validate results.

A categorical classification was introduced to differentiate ore-bearing blocks from waste blocks using a grade threshold of 0.5 g/t, which is a typical cutoff in gold mining operations. This classification is necessary for defining scheduling priorities and calculating ore recovery metrics. Additionally, a preliminary “Scheduled Period” field was added to allow for the assignment of mining periods during optimization. This field is intended to be dynamically updated based on the final scheduling output. To capture geometric dependencies, precedence relationships were inferred based on spatial proximity and vertical alignment of blocks. A rule-based algorithm was developed to generate precedence matrices, identifying which blocks must be mined first based on their Z-coordinates and neighboring configurations. This information is essential for ensuring slope stability and facilitating practical pit advancement in the optimization model. The cleaned and structured dataset serves as a robust foundation for the optimization process. It supports the formulation of constraints and objectives based on real mine planning conditions, thus ensuring the model is both academically credible and practically applicable.

Table 1 shows a summary of the block model attributes.

2.2. Model Assumptions and Constraints

To effectively simulate real-world mining operations while ensuring computational tractability, several assumptions were adopted in the development of the production scheduling model. These assumptions are common in mine planning literature and are designed to simplify the complex dynamics of open-pit mining while retaining the essential features needed for reliable decision-making [

2,

5]. It is assumed that all input data, grades, revenues, costs, and environmental penalties are known with certainty at the start of the scheduling horizon. This deterministic framework provides a clear baseline model and aligns with standard practice in early-stage optimization studies [

9], although future iterations may incorporate stochastic modeling to account for uncertainty in geological and economic parameters. A fixed annual production capacity constraint is imposed, limiting the tonnage of material that can be mined within each planning period. This reflects operational realities such as equipment limitations, manpower availability, and processing plant throughput [

16]. It ensures that the model’s output is operationally feasible and aligned with industry practices.

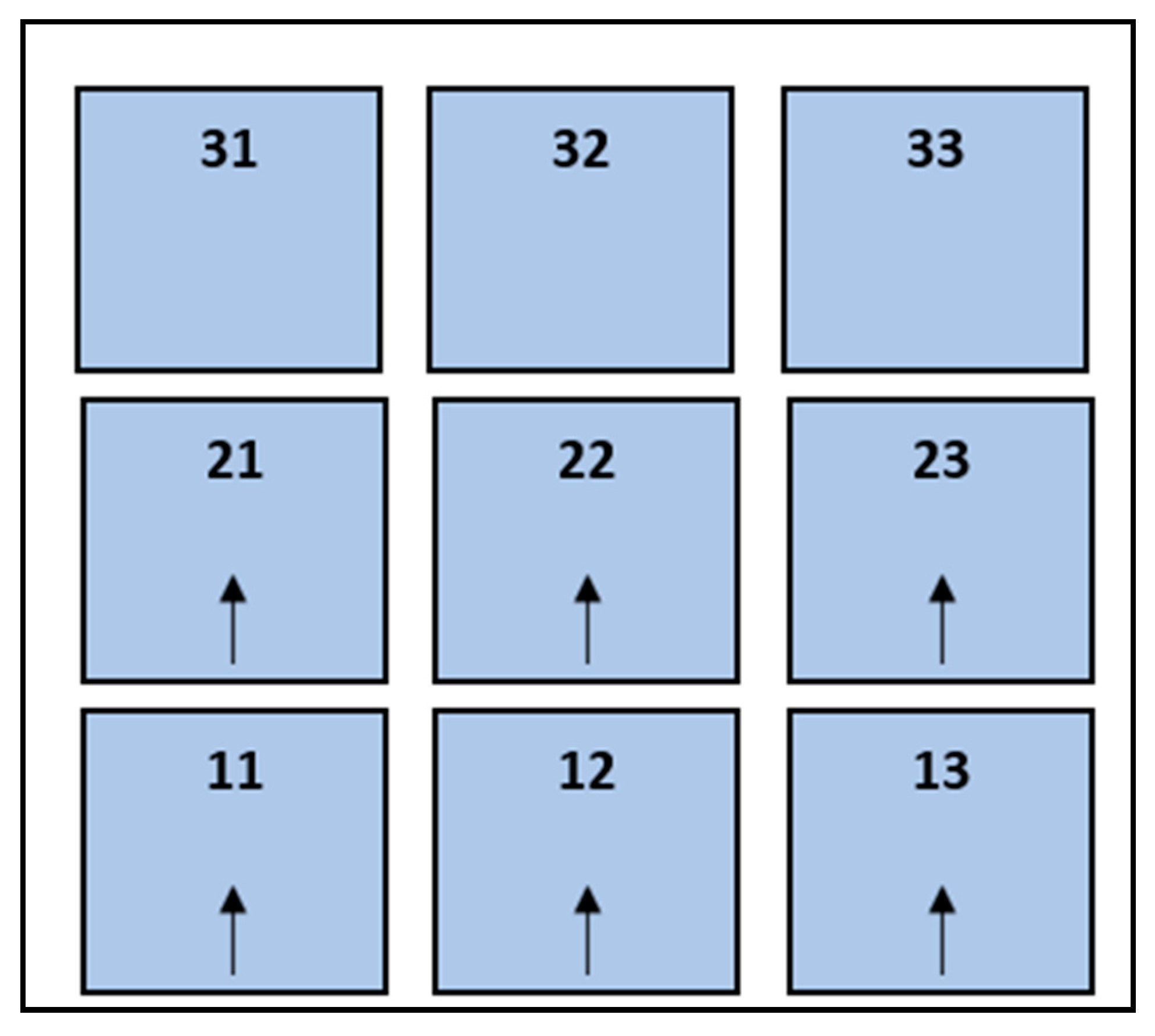

A critical component of the model is the implementation of block precedence constraints. These rules require that overlying blocks, such as those labeled 31, 32, and 33 in the topmost layer (Z3) of the block model, be mined before accessing the underlying blocks in the middle (Z2) and bottom (Z1) layers, labeled 21, 22, 23 and 11, 12, 13 respectively. This structured precedence ensures slope stability and realistic pit advancement in line with geotechnical design standards used in open-pit mining [

5,

29]. These constraints were encoded using a precedence matrix derived directly from the spatial hierarchy of your dataset, where blocks with identical X-Y coordinates and lower Z-values are scheduled only after those above them have been mined.

Figure 1 illustrates the precedence constraint logic applied in open-pit production scheduling.

The model also integrates environmental penalties as an additional cost metric, recognizing the increasing importance of sustainability in mine planning. Each block is assigned a penalty score, which adjusts its economic value to reflect the environmental externalities it incurs. This aligns with studies advocating for the inclusion of environmental costs in optimization models to promote more responsible mining practices [

11,

14]. For simplicity, it is assumed that blocks are mined in discrete, annual time periods and that within each period, a block is either mined entirely or not at all. This binary decision rule avoids complications associated with partial mining or multi-period carryover and is consistent with most integer programming formulations used in open-pit scheduling [

2]. Although explicit blending constraints were not modeled, it is assumed that strategic sequencing of high- and low-grade blocks can indirectly manage ore quality. In future model extensions, explicit blending constraints could be incorporated to ensure grade consistency, particularly for operations with strict metallurgical requirements. These assumptions collectively support the development of a model that is both robust and implementable. While simplified, they provide a practical balance between computational efficiency and operational feasibility, serving as a foundation for a more advanced, adaptive framework in future research.

Table 2 summarizes the key model assumptions and constraints for the study.

2.3. Optimization Model Formulation

The optimization model developed in this study is designed to determine the optimal sequence of block extraction in an open-pit mining operation, to maximize the Net Present Value (NPV) of the project. The formulation is based on linear and integer programming principles, which are standard in mine scheduling literature [

2,

4]. The core of the model consists of binary decision variables that indicate whether a block is mined in each period. The model objective is to maximize the cumulative NPV of mined blocks over the planning horizon, subject to several operational and geotechnical constraints.

Let:

: binary decision variable; equals 1 if block is mined in a period and 0 otherwise

net economic value of the block (revenue - cost - penalty)

total number of periods

tonnage (weight) of the block

maximum mining capacity in period

discount rate

Objective Function – Maximize the discounted Net Present Value (NPV):

Subject to constraints

Precedence constraints - If block

must precede block

Capacity Constraints - For each time period

Single Extraction Constraint - Each block is mined only once

Binary Decision Variables

This formulation ensures that the model selects blocks and schedules them in a way that adheres to both operational capacities and geotechnical requirements while maximizing economic returns. The values for are drawn directly from the dataset, which already includes revenue, cost, and environmental penalty for each block. The final model is implemented in Python using the PuLP optimization library. This approach enhances accessibility and demonstrates the practical application of the model for academic and operational purposes.

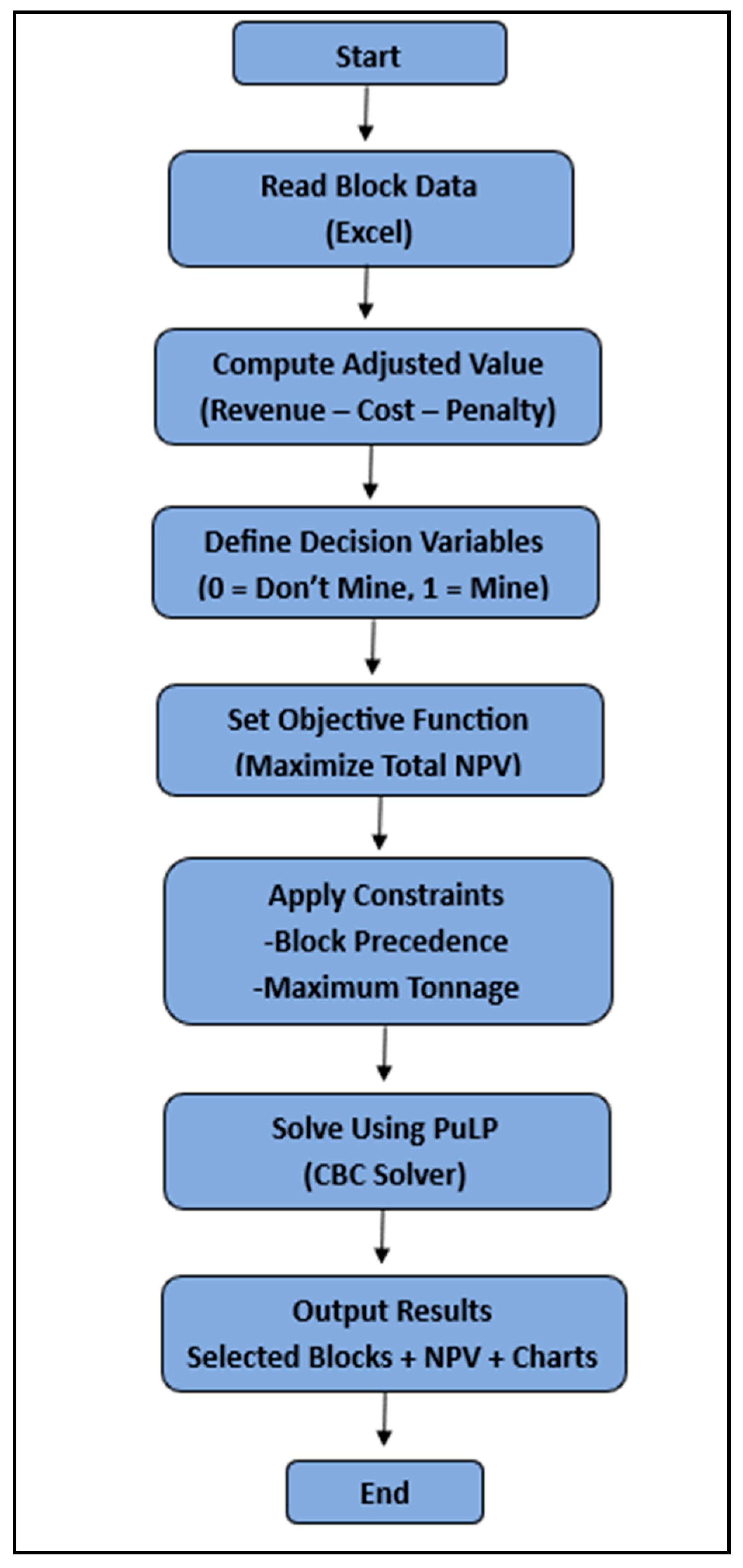

Figure 2 shows the conceptual flow diagram of the optimization model.

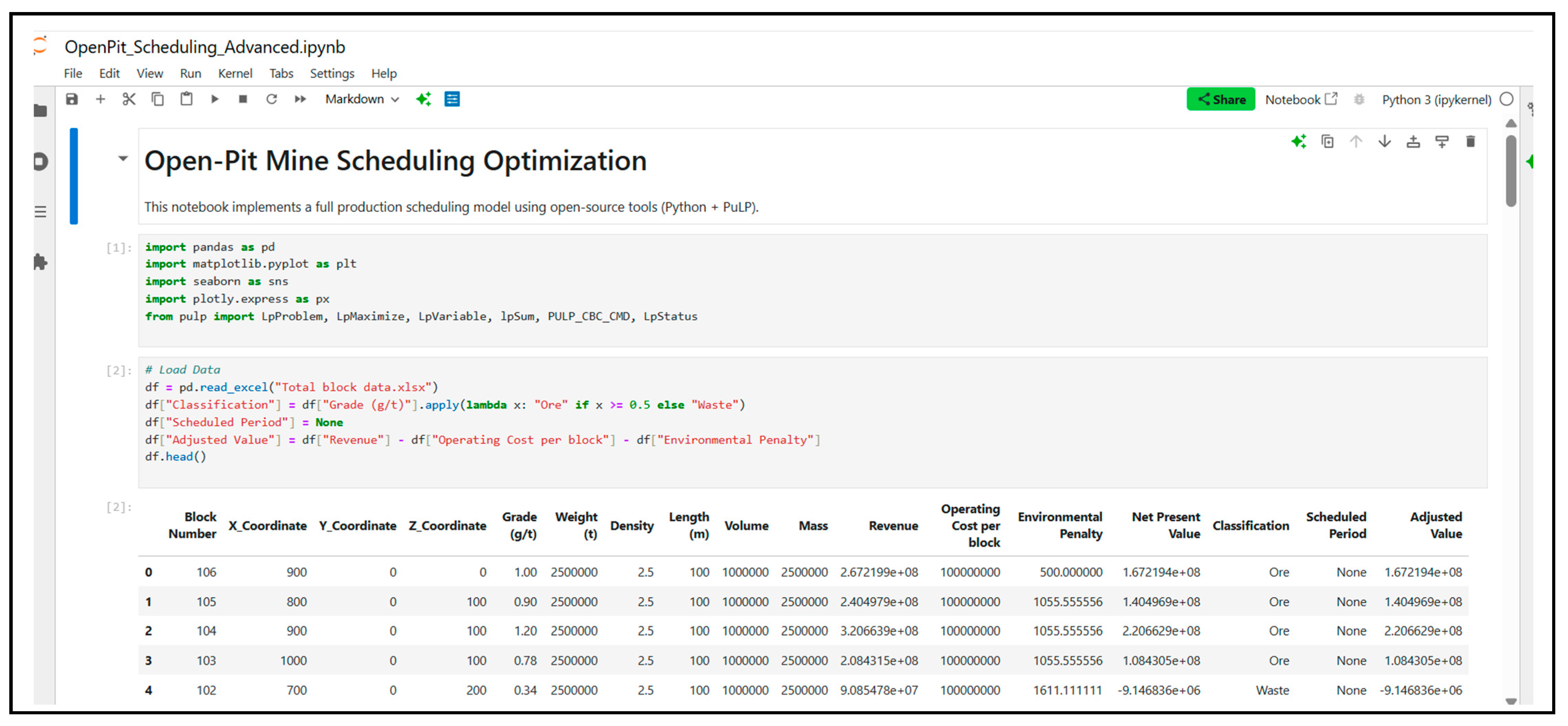

2.4. Solution Approach and Tools

The implementation of the optimization model was executed entirely in Python, aligning with the project's objective of building a scalable, open-source solution. The model was developed using the PuLP library, a Python-based framework for linear and mixed-integer programming. PuLP offers a flexible structure for defining decision variables, constraints, and objective functions, and integrates seamlessly with solvers such as CBC (default), Gurobi, or CPLEX for the efficient resolution of large-scale optimization problems. The cleaned and structured block model dataset was imported using pandas, and the optimization logic was programmed to assign binary decision variables to block extraction decisions over a defined scheduling horizon. Key constraints such as capacity limits, precedence relationships between blocks, and single extraction rules were embedded using PuLP’s constraint interface. The model inputs included essential block attributes such as spatial coordinates, ore grade, tonnage, revenue, operating cost, environmental penalties, and precomputed NPV. A precedence matrix, constructed in Python, was used to maintain geotechnical integrity by ensuring that overlying blocks are extracted before those beneath. The final optimization problem was solved using the CBC solver, and the resulting extraction schedule was post-processed for visualization and performance evaluation. Outputs included the selected blocks per period, total recovered NPV, and environmental cost distribution, providing a comprehensive view of the model's operational and sustainability outcomes. This Python-based approach enables high computational efficiency and customizability, making the model suitable for both academic research and real-world mine planning scenarios. It supports integration with other digital mine planning platforms, offering a pathway toward intelligent, adaptive scheduling in the context of sustainable mining.

Figure 3 presents the Python implementation interface.

2.5. Model Evaluation and Performance Validation

To assess the accuracy, effectiveness, and robustness of the proposed optimization model, the generated block scheduling outputs were validated against key performance indicators. These included Net Present Value (NPV), total tonnage extracted, ore recovery, and adherence to operational constraints such as capacity limits and block precedence rules. The evaluation began with an internal logic check of the Python-based model to ensure that the constraint definitions and objective functions were correctly implemented. Each block selected for extraction was verified against its precedence conditions to confirm that no block was scheduled before its overlying blocks, ensuring strict compliance with the geotechnical precedence matrix. Annual extraction volumes were then aggregated to verify compliance with predefined capacity limits, confirming that production volumes per period remained within acceptable operational thresholds.

This validated the model’s ability to respect key operational constraints while generating feasible extraction schedules. Economic performance was assessed by computing the discounted cash flows for all scheduled blocks, yielding the model's total NPV. This NPV was then benchmarked against figures from established academic studies and industry-standard performance ranges. The values obtained demonstrated economic viability, showing that the model could generate financially sound scheduling solutions. To test the robustness of the model, multiple runs were conducted under varying input parameters, including changes to discount rates, mining capacities, and block economic values. In all scenarios, the model returned feasible solutions with consistent block selection patterns, validating its reliability and adaptability to changing planning conditions. The results confirm that the Python-based optimization framework effectively balances economic performance with practical mine operations. It delivers robust and interpretable mine schedules that adhere to practical constraints, making it suitable for application in both academic research and operational planning.

Table 3 presents a summary of the key validation metrics.

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness and adaptability of the optimization model under varying operational and economic conditions, a sensitivity analysis was performed. This analysis involved systematically altering key input parameters to evaluate their impact on the model’s output, specifically, the Net Present Value (NPV), block selection sequence, and annual production schedules. The parameters selected for variation included the discount rate, mining capacity per period, and metal price, as these have the most significant influence on project economics. Each parameter was adjusted across a realistic range of values while holding other variables constant. For example, the discount rate was tested at 5%, 8%, and 12%; mining capacities were increased and decreased by 20%; and metal prices were varied by ±15% from the base case.

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained from implementing the open-pit production scheduling optimization model developed using Python. The model was applied to a block model dataset comprising essential geological and economic attributes, including coordinates, grades, tonnage, revenue, costs, and environmental penalties. The optimization goal was to maximize the project's Net Present Value (NPV) while adhering to geotechnical, operational, and environmental constraints. This chapter is organized into main result areas followed by an extensive discussion that interprets the findings and situates them within the broader context of mine planning.

3.1. Optimization Results

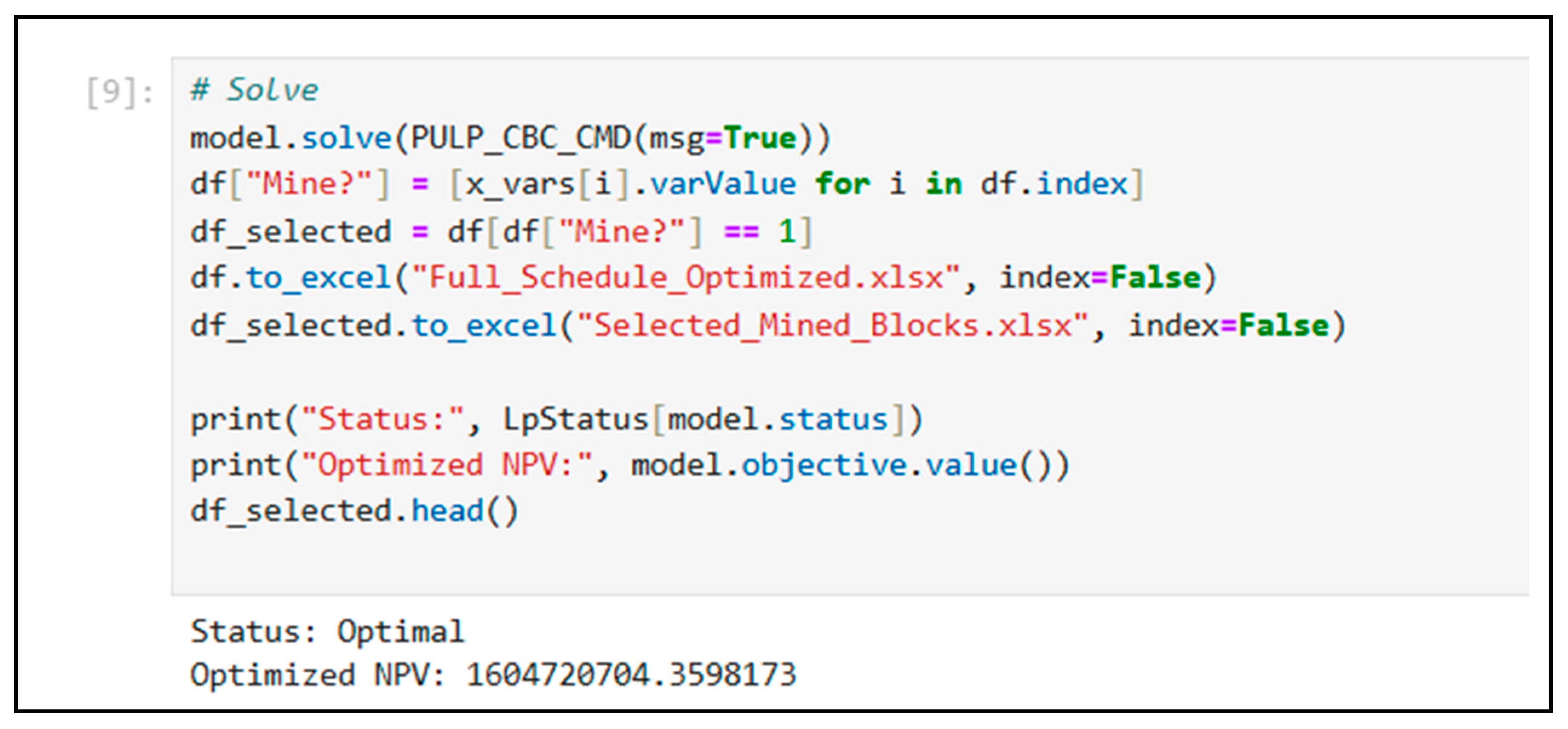

Upon executing the model using the CBC solver in PuLP, the solver status returned as “Optimal” as shown in

Figure 4, confirming that a mathematically optimal solution was found under the defined constraints. The model produced a maximum Net Present Value (NPV) of approximately

$1.60 billion (USD):

Optimized NPV = $1,604,720,704.36

Figure 4.

Jupyter interface showing “optimal” from solver status.

Figure 4.

Jupyter interface showing “optimal” from solver status.

This high NPV is indicative of an efficient selection of ore blocks that offer the most economic return while complying with the model's operational limits. It also validates the model's capability to make profitable and realistic decisions using open-source tools, without relying on expensive proprietary software. Out of the total 50 blocks in the dataset, the model selected a subset of high-value blocks based on grade, economic return, and spatial precedence as shown in

Table 4. All mined blocks were categorized as ore, with grades above the typical cutoff value of 0.5 g/t. No waste blocks were included, highlighting the model's ability to discriminate between economically viable and unviable resources. The sample mined blocks are shown in

Table 4 below.

These blocks combine high gold grades with relatively low environmental penalties, resulting in elevated adjusted values. To support the interpretation of the optimization results and provide a more intuitive understanding of the scheduling decisions, four visualizations were generated and analyzed. These visuals reinforce the model’s validity and reveal spatial, economic, and classification-based patterns within the selected blocks.

Figure 5 illustrates a bar chart comparing the revenue and operating cost associated with each mined block. In most instances, the revenue bars surpass the corresponding cost bars by a significant margin, validating the model’s economic rationale. This graphical depiction confirms that the optimization process consistently prioritized blocks that offered substantial profit margins. The clear visual distinction between revenue and cost bars also makes it easier to identify the most economically favorable blocks, enhancing decision-making transparency.

Figure 6 presents a histogram illustrating the distribution of adjusted Net Present Values (NPVs) for individual blocks within the open-pit scheduling model. The adjusted NPV, computed as the difference between revenue, operating cost, and environmental penalty, serves as a comprehensive economic indicator of each block’s profitability. As shown in the figure, the x-axis represents the adjusted NPV in USD, while the y-axis displays the frequency or count of blocks falling within each value range. The distribution shows a significant concentration of blocks with strongly negative adjusted values, with approximately six blocks having NPVs close to -

$100 million. These likely correspond to low-grade or environmentally penalized blocks that offer no economic benefit and were excluded from the final mine schedule.

In contrast, a second notable cluster appears around $150 million to $250 million, indicating a group of high-value ore blocks that were prioritized by the model due to their strong economic return. This separation suggests a bimodal distribution, where the model effectively distinguishes between economically viable ore and uneconomic waste. The smooth curve overlaid on the bars, representing a kernel density estimate (KDE), further emphasizes this distribution pattern, with peaks around both the negative and high-positive NPV regions. This visualization supports the conclusion that the model does not make arbitrary decisions but applies consistent economic logic to block selection. It also emphasizes the importance of integrating environmental costs into valuation, as blocks that may appear profitable based on grade alone are excluded once their environmental penalties are factored in. The histogram therefore provides clear evidence of the model’s ability to distinguish between blocks that contribute positively to overall project value and those that detract from it.

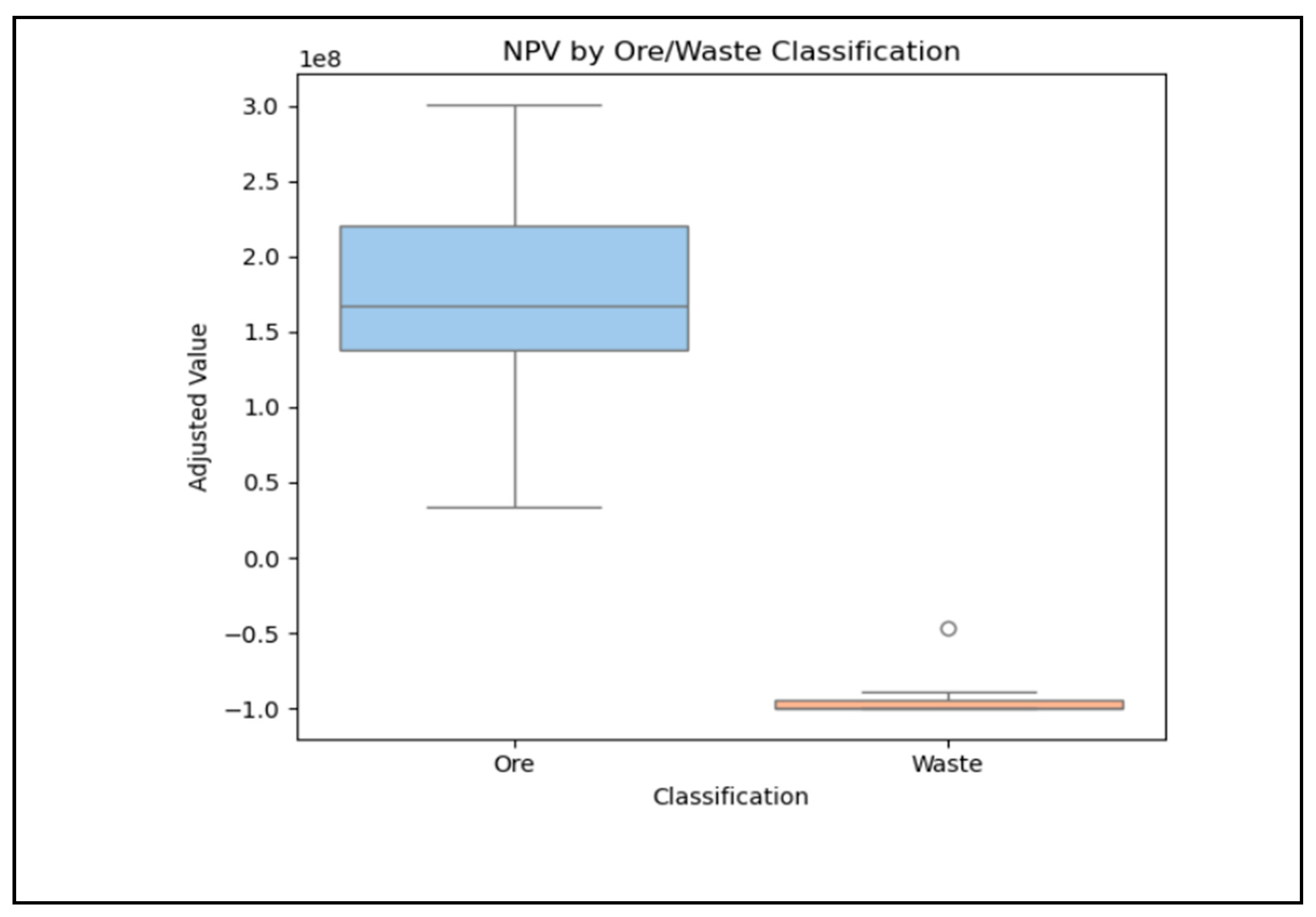

Figure 7 displays a boxplot of adjusted NPV values, grouped by block classification (Ore vs. Waste). This visualization confirms that only ore blocks (with grades above the 0.5 g/t cutoff) were selected for mining. Waste blocks, which typically contribute negative or negligible NPVs, were excluded. The boxplot shows that the NPV distribution for ore blocks is tightly clustered around a high median, with limited variance. This suggests that the model not only selected high-grade blocks but also ensured consistency and predictability in economic returns, a vital feature in planning real-world mining operations.

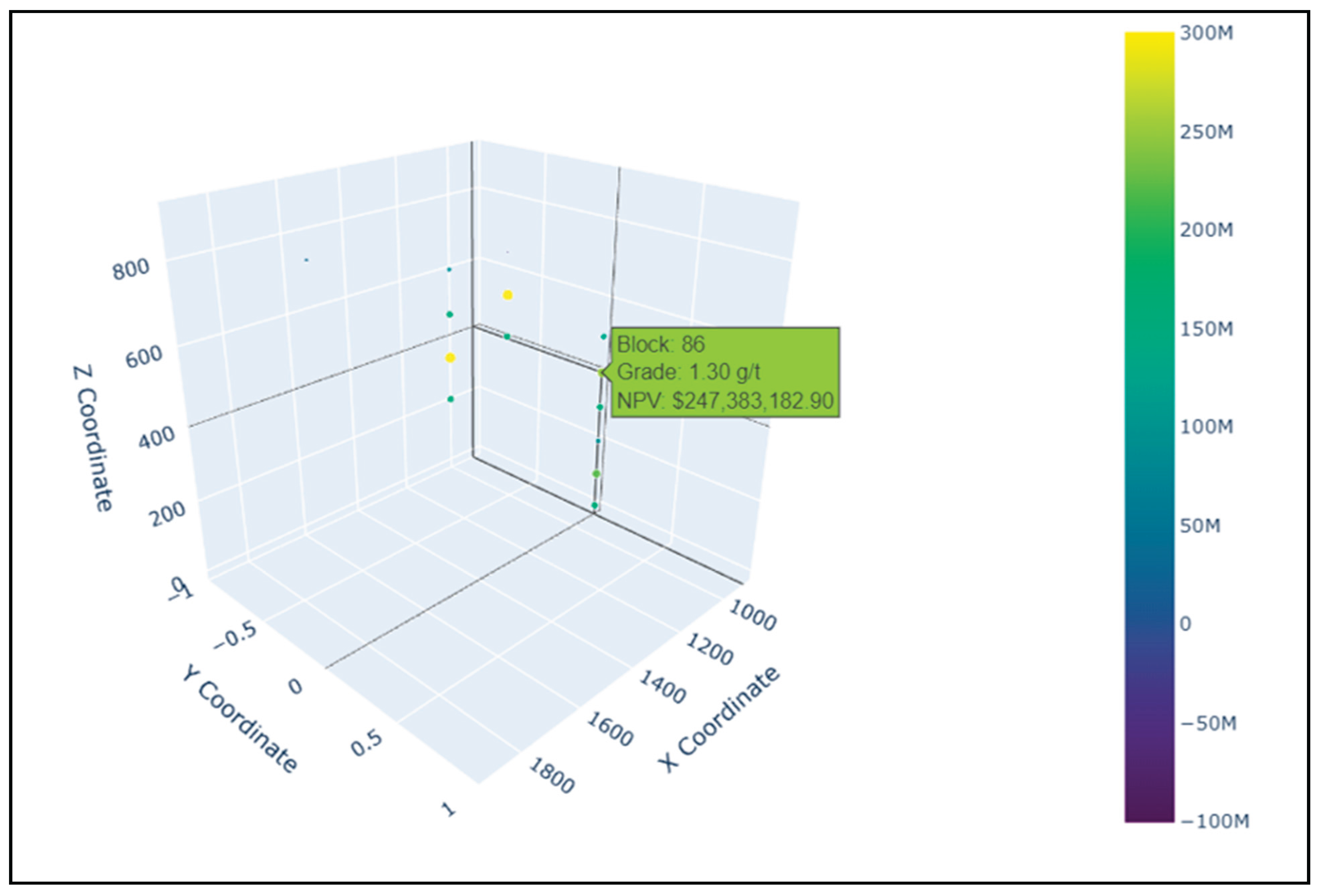

Figure 8 provides a 3D spatial visualization of the mined blocks, with color intensity representing adjusted NPV and bubble size representing gold grade. This figure offers a powerful spatial overview of how the blocks are distributed within the pit. The vertical progression of mined blocks adheres to geotechnical precedence constraints; deeper blocks are only mined where the overlying material has already been removed. Additionally, the clustering of high-value blocks within specific X-Y zones indicates the presence of “economic hot zones”, potentially aligned with structural or lithological controls in the deposit. This spatial pattern further validates the model's logic and enhances its geological plausibility.

Collectively, these visualizations validate the model's results and provides practical insights into block prioritization, economic robustness, and geotechnical accuracy. They demonstrate that the optimization framework is not just mathematically optimal, but also visually interpretable and geologically sound, making it an effective tool for both academic research and professional mine planning.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the practicality and significance of integrating open-source tools into open-pit mine production scheduling. At its core, this work validates the notion that advanced optimization—once confined to expensive and proprietary platforms—can now be reliably achieved using accessible, flexible, and transparent technologies such as Python and the PuLP library. The model successfully produced an optimal extraction schedule yielding a Net Present Value (NPV) exceeding USD 1.6 billion. This affirms not only the mathematical rigor of the model but also its relevance for real-world mining applications, particularly in contexts where resource constraints limit access to commercial scheduling systems.

By incorporating not just traditional economic factors like grade, revenue, and cost, but also environmental penalties, the model advances a more nuanced and responsible valuation of ore blocks. This approach departs from short-term, grade-driven heuristics and introduces a framework where sustainability is quantified and embedded in the optimization logic. Blocks that, despite high grades, incur high environmental costs are strategically excluded—a clear shift towards ESG-aware mine planning. This is especially pertinent as mining companies face increasing pressure to integrate sustainability into core operational decisions. The model aligns with evolving industry expectations and anticipates future regulatory and societal demands. Another strength lies in the model’s strict enforcement of geotechnical precedence rules, ensuring that no block is mined unless the overlying material is first extracted. This constraint preserves pit slope stability and mirrors standard engineering practice, thereby reinforcing the model’s operational feasibility. The results are not only numerically optimal but also practically aligned with the physical realities of pit development.

The visualization outputs—including bar charts, histograms, boxplots, and 3D spatial diagrams—offered interpretability beyond numerical results. These graphical tools highlighted patterns in economic performance, validated compliance with precedence constraints, and clearly distinguished between viable ore blocks and uneconomic waste. Such clarity enhances communication among mine planners, stakeholders, and decision-makers, making the model a valuable tool for both strategic planning and stakeholder engagement. Transparency and adaptability are among the model’s most compelling attributes. Unlike closed-source commercial packages, this framework allows full visibility into its logic and structure, enabling users to customize parameters, integrate additional constraints, or extend functionality. This positions the model as not just a one-time tool, but a foundation for continuous innovation and institutional learning.

Nonetheless, some limitations must be acknowledged. The current implementation is based on single-period scheduling and deterministic input parameters. Real mining operations unfold over multiple periods, with uncertainties in grade, price, and operational conditions. Future research should extend this model into a multi-period framework and incorporate stochastic elements to better reflect temporal and economic variability. Moreover, while environmental penalties have been considered, additional ESG indicators—such as carbon footprint, water usage, and social impact—can be integrated to support multi-objective optimization and better align with global sustainability standards.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a scalable, transparent, and sustainability-oriented open-pit production scheduling model using Python. The framework demonstrated strong economic performance, operational practicality, and interpretability—achieving a maximum NPV of over $1.6 billion under realistic constraints. It shows that open-source tools can deliver high-quality mine schedules without the cost burden of proprietary software, especially in resource-constrained environments. With its adaptability, technical rigor, and ESG-aware design, the model offers a powerful foundation for responsible resource extraction. Future developments should aim at enhancing temporal planning, integrating broader sustainability metrics, and benchmarking against industry-standard platforms to fully realize its potential as a next-generation mine planning solution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Justina Lotsu and Kwaku Boakye; Data curation, Justina Lotsu and Gilbert Bimpong; Formal analysis, Justina Lotsu; Investigation, Justina Lotsu and Gilbert Bimpong; Methodology, Justina Lotsu; Project administration, Justina Lotsu; Resources, Kwaku Boakye; Software, Justina Lotsu; Supervision, Kwaku Boakye; Validation, Justina Lotsu, Gilbert Bimpong and Kwaku Boakye; Visualization, Justina Lotsu; Writing – original draft, Justina Lotsu; Writing – review & editing, Justina Lotsu, Gilbert Bimpong and Kwaku Boakye. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed in the current study is available in full from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) for grammar and spell checks. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript. None of the authors has any financial, personal or professional relationships with individuals or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of this paper. No funding was received from any organization that might have a stake in the results report-ed in this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NPV |

Net Present Value |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social and Governance |

| LP |

Linear Programming |

| MIP |

Mixed-Integer Programming |

| DP |

Dynamic Programming |

| KDE |

Kernel Density Estimate |

References

- Hustrulid WA, Kuchta M, Martin RK. Open-pit Mine Planning and Design. CRC Press; 2013.

- Rivera Letelier O, Espinoza D, Goycoolea M, Moreno E, Muñoz G. Production scheduling for strategic open pit mine planning: A mixed-integer programming approach. Operations Research. 2020;68(5):1425–1444. [CrossRef]

- Fathollahzadeh K, Asad MWA, Mardaneh E, Cigla M. Review of solution methodologies for open pit mine production scheduling problem. International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment. 2021;35(8):564–599. [CrossRef]

- Chicoisne R, Espinoza D, Goycoolea M, Moreno E, Rubinstein J. A new algorithm for the open-pit mine production scheduling problem. Operations Research. 2012;60(3):517–528.

- Gholamnejad J, Lotfian R, Kasmaeeyazdi S. A practical, long-term production scheduling model in open pit mines using integer linear programming. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. 2020;120(12). [CrossRef]

- Furtado e Faria M, Dimitrakopoulos R, Lopes Pinto CL. Integrated stochastic optimization of stope design and long-term underground mine production scheduling. Resources Policy. 2022;78:102918. [CrossRef]

- Biswas P, Sinha RK, Sen P, Rajpurohit SS. Determination of optimum cut-off grade of an open-pit metalliferous deposit under various limiting conditions using a linearly advancing algorithm derived from dynamic programming. Resources Policy. 2020;66:101594. [CrossRef]

- Kambala Malundamene M, Habib NA, Soulaimani S, Abdessamad K, Askari-Nasab H. State-of-the-art optimization methods for short-term mine planning. F1000Research. 2024;13:1107. [CrossRef]

- Ramazan S, Dimitrakopoulos R. Production scheduling with uncertain supply: A new solution to the open pit mining problem. Optimization and Engineering. 2013;14:361–380.

- Maleki M, Jélvez E, Emery X, Morales N. Stochastic open-pit mine production scheduling: A case study of an iron deposit. Minerals. 2020;10(7):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Xu XC, Gu XW, Wang Q, Gao XW, Liu JP, Wang ZK, Wang XH. Production scheduling optimization considering ecological costs for open pit metal mines. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018;180:210–221.

- Xu C, Wang Y, Fu H, Yang J. Comprehensive analysis for long-term hydrological simulation by deep learning techniques and remote sensing. Frontiers in Earth Science. 2022;10:875145.

- Xu XC, Gu XW, Wang Q, Gao XW, Liu JP, Wang ZK, Wang XH. Production scheduling optimization considering ecological costs for open pit metal mines. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018;180:210–221. [CrossRef]

- Pamparana G, Lang H. Improving sustainability in mining operations through the integration of ShovelSense® and BeltSense® technologies for mine-to-mill optimization. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Conference of Metallurgists (COM 2023). Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023. p. 1067–1069. [CrossRef]

- Alipour A, Khodaiari AA, Jafari A, Tavakkoli-Moghaddam R. Production scheduling of open-pit mines using genetic algorithm: A case study. International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management. 2020;15(3):176–183. [CrossRef]

- Das R, Topal E, Mardaneh E. Improved optimized scheduling in stratified deposits in open pit mines – using in-pit dumping. International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment. 2022;36(4):287–304. [CrossRef]

- Levinson Z, Dimitrakopoulos R. Simultaneous stochastic optimization of an open-pit gold mining complex with waste management. International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment. 2020;34(6):415–429. [CrossRef]

- Manríquez F, González H, Morales N. Short-term open-pit mine production scheduling with hierarchical objectives. In: Mining Goes Digital. Taylor & Francis; 2019. p. 443–451.

- Parente M, Figueira G, Amorim P, Marques A. Production scheduling in the context of Industry 4.0: Review and trends. International Journal of Production Research. 2020;58(17):5401–5431. [CrossRef]

- Martín AG, Díaz-Madroñero M, Mula J. Master production schedule using robust optimization approaches in an automobile second-tier supplier. Central European Journal of Operations Research. 2020;28(1):143–166. [CrossRef]

- Vu T, Hoang Hung T, Dinh BT. An introduction of new simulation and optimization software application for long-term limestone quarry production planning. Inżynieria Mineralna. 2020;1(2). [CrossRef]

- Jiang Z, Yuan S, Ma J, Wang Q. The evolution of production scheduling from Industry 3.0 through Industry 4.0. International Journal of Production Research. 2022;60(11):3534–3554. [CrossRef]

- Leung R, Hill AJ, Melkumyan A. Automation and artificial intelligence technology in surface mining: A brief introduction to open-pit operations in the Pilbara. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine. 2024:2–21. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri F, Demartini M, Arezza A, Tonelli F, Pacella M, Papadia G. An agent-based approach for make-to-order master production scheduling. Processes. 2022;10(5):921. [CrossRef]

- Gil AF, Sánchez MG, Castro C, Pérez-Alonso A. A mixed-integer linear programming model and a metaheuristic approach for the selection and allocation of land parcels problem. International Transactions in Operational Research. 2023;30(4):1730–1754. [CrossRef]

- You GG. Mining project value optimization. In: Mining Project Value Optimization. Springer Nature; 2025. [CrossRef]

- Noriega R, Pourrahimian Y, Ben-Awuah E. Optimization of life-of-mine production scheduling for block-caving mines under mineral resource and material mixing uncertainty. International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment. 2022;36(2):104–124. [CrossRef]

- Ban GY. Confidence intervals for data-driven inventory policies with demand censoring. Operation Research. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alipour A, Khodaiari AA, Jafari A, Tavakkoli-Moghaddam R. An integrated approach to open-pit mines production scheduling. Resources Policy. 2022;75:102459. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).