Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1)

- Analyze each stage of in-situ PC production and stockyard management

- 2)

- Review BIM and DT applications in the construction industry

- 3)

- Analyze time requirements for each production stage

- 4)

- Simulate integrated production and yard management using BIM for a real logistics center project

- 5)

- Optimize the construction schedule using Crystal Ball based on BIM data

- 6)

- Optimize CO₂ emissions using the same simulation approach

- 7)

- Compare layout scenarios to validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework

2. Literature Review

2.1. Integration of BIM and DT in the Construction Industry

2.2. DT for Predictive Planning and Risk Management

2.3. On-Site Precast Concrete Production and Stockyard Management

2.4. Simulation-Based Optimization of Schedule and Environmental Impact

2.5. Research Gap

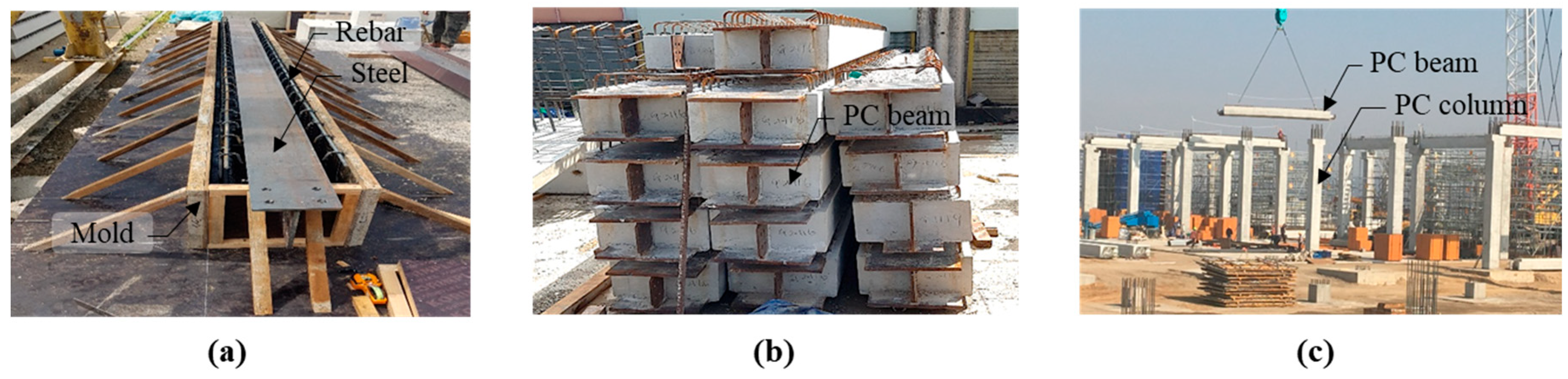

3. Case Application of BIM-Based In-Situ Production

3.1. Selection of the Case Project

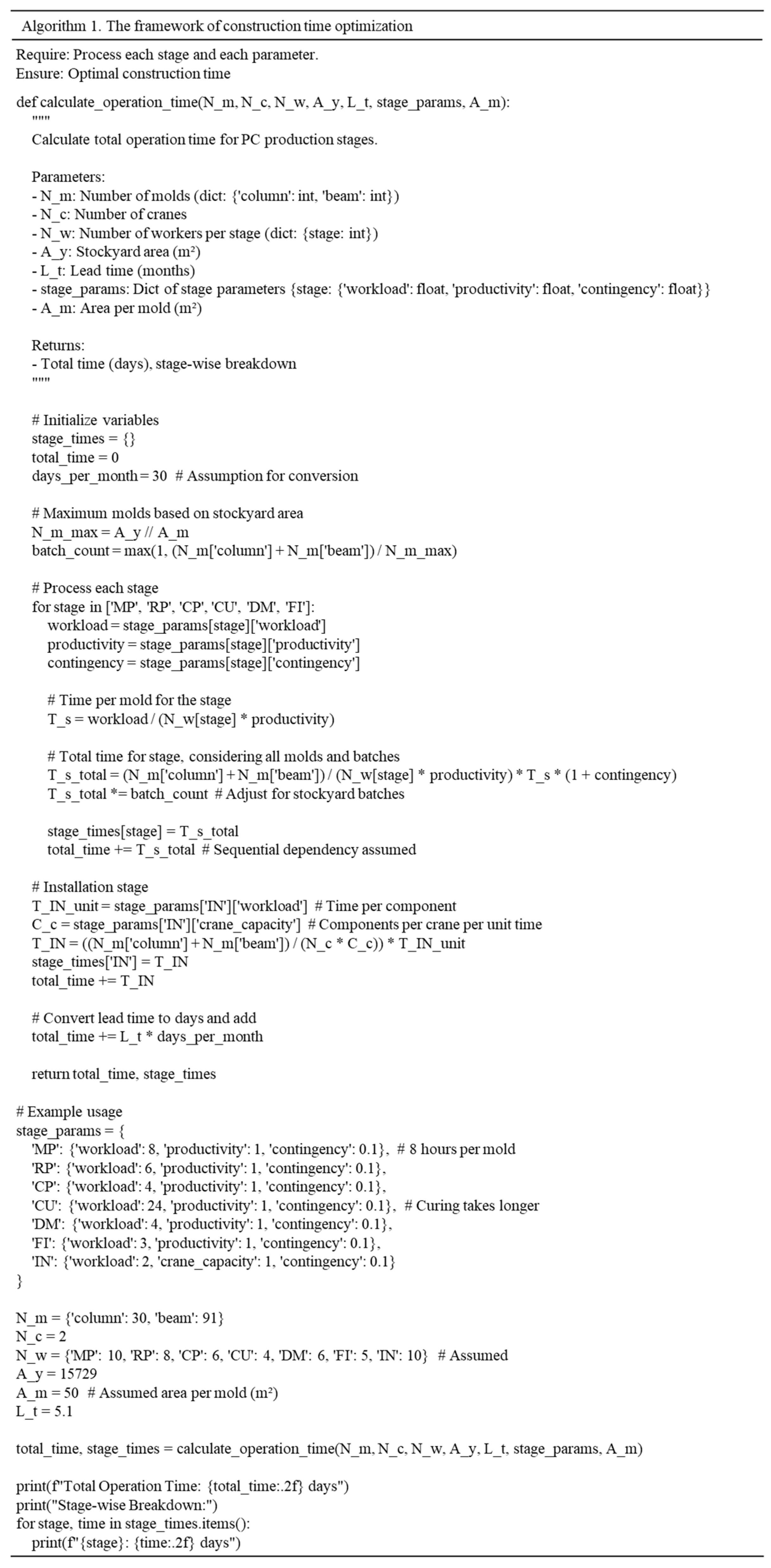

3.2. Analysis of In-Situ Production and Installation Time for PC Components

3.3. Analysis of Yard Layout Planning for In-Situ Produced PC Components

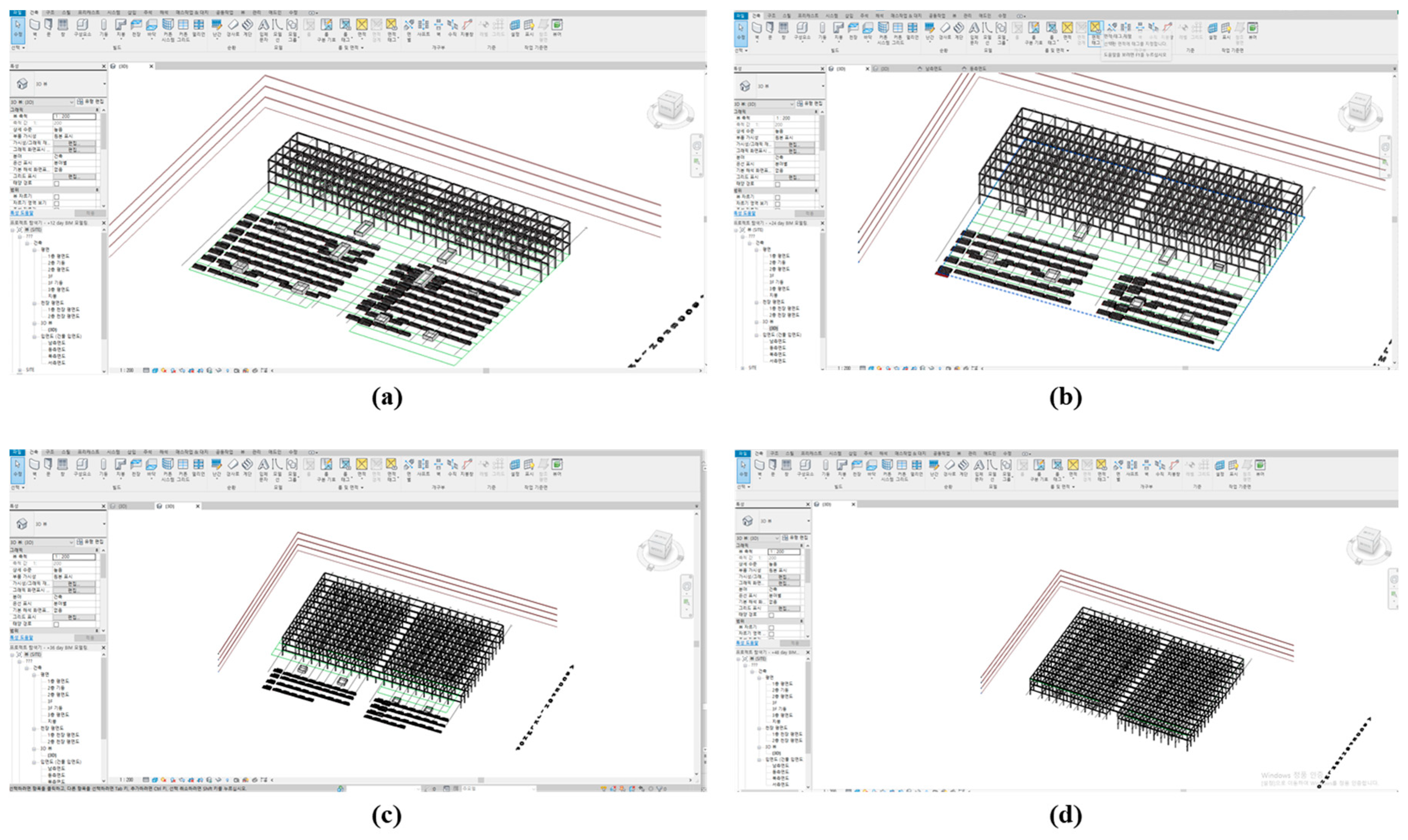

3.4. 4D Simulation Using BIM

| Monthly area | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Production area | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Yard stock area | 2.8 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 11.3 | 13.9 | 8.2 | 4.1 | 0.0 |

4. Optimization of Schedule and CO₂ Emission

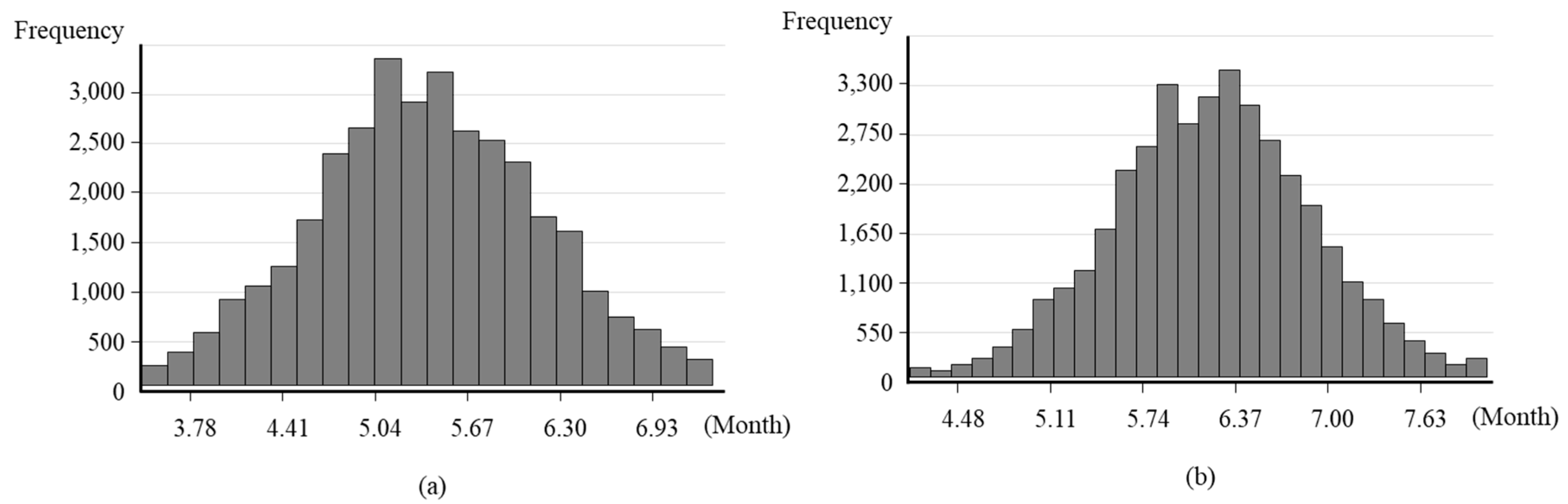

4.1. Schedule Optimization

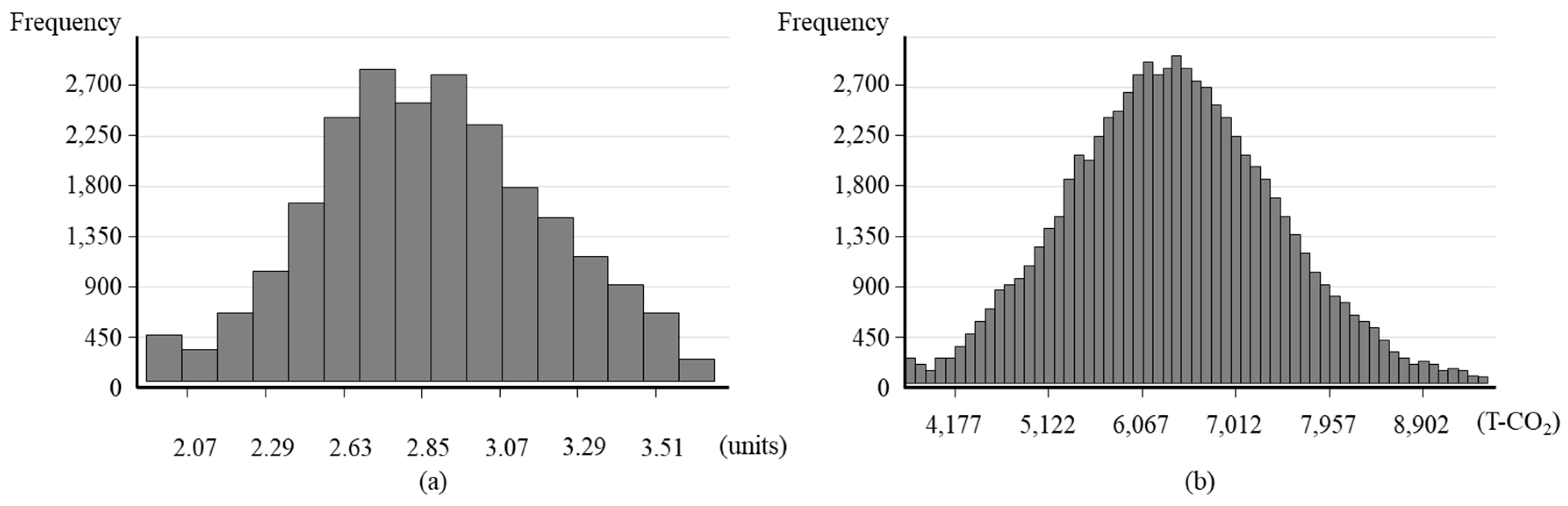

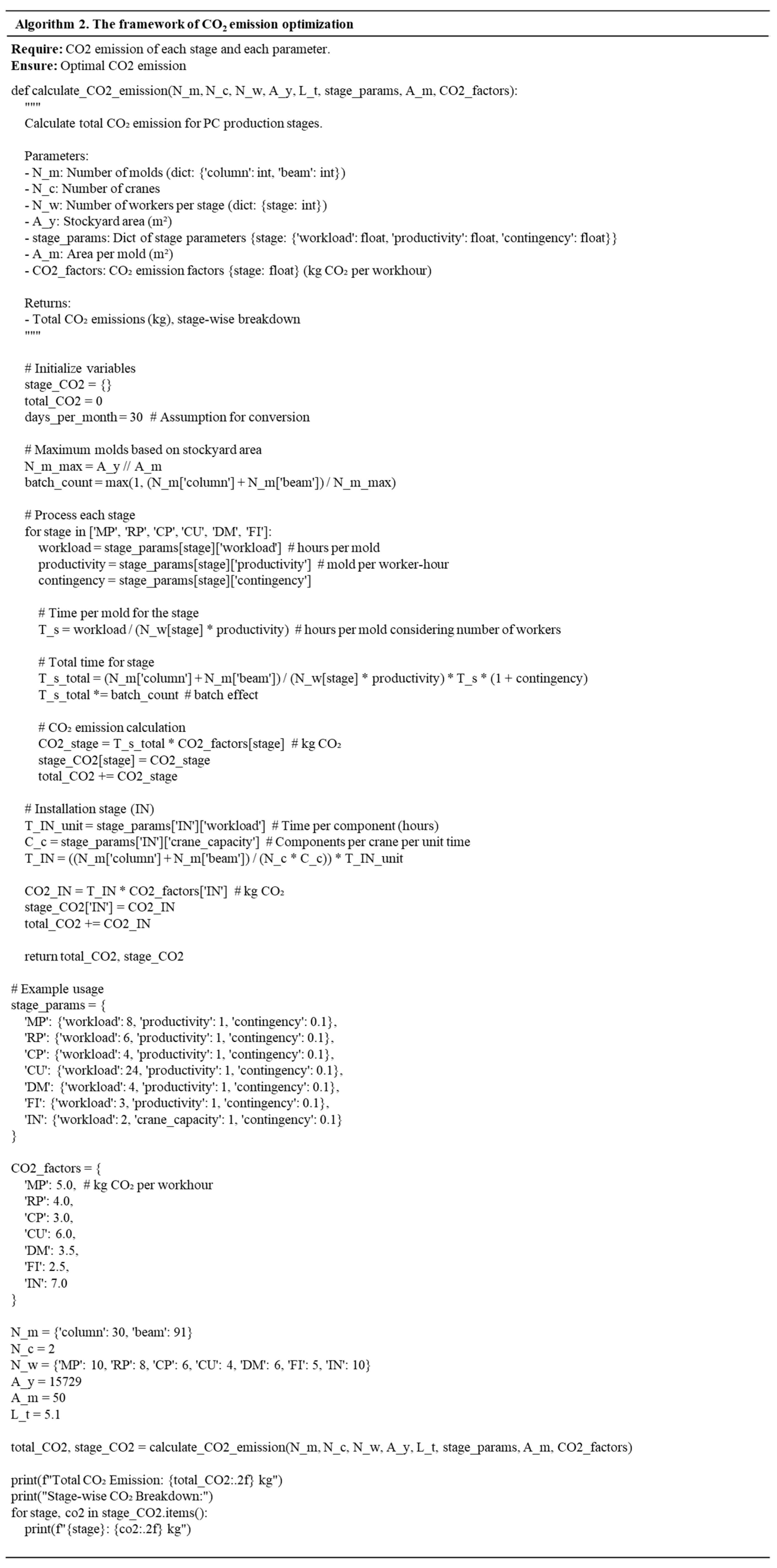

4.2. CO₂ emission Optimization

5. Conclusion

- Integrating real-time sensor data for dynamic feedback control,

- Applying machine learning techniques to improve CO₂ emission forecasting,

- Enhancing safety and risk management through predictive analytics, and

- Developing cloud-based visualization dashboards for intelligent site monitoring.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Merschbrock, C., & Munkvold, B. E. (2024). The digital transformation of the construction industry: A review. Industrial and Commercial Training, 56(2), 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Nyqvist, R., Peltokorpi, A., Lavikka, R., & Ainamo, A. (2025). Building the digital age: management of digital transformation in the construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 43(4), 262-283. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q., & Tao, F. (2021). Digital twins and big data towards smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0: 360-degree comparison. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 59, 101542. [CrossRef]

- Boje, C., Guerriero, A., Kubicki, S., & Rezgui, Y. (2020). Towards a semantic construction digital twin: Directions for future research. Automation in Construction, 114, 103179. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-H., & Kim, G.-H. (2024). Development of BIM Utilization Level Evaluation Model in Construction Management Company. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 25(4), 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., Song, S. H., Lee, C., Ahn, H., Cho, H., & Kang, K.-I. (2024). BIM and OpenAI-based Model for Supporting Initial Construction Planning of Bridges and Tunnels. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 25(6), 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., & Seong, H. (2025). Conceptual Model for Quality Risk Assessment and Reserve Cost Estimation for Construction Projects based on BIM. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 26(2), 62–71. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Nam, J. (2025). Applying BIM Standard Guideline to Expressway BIM Results and Drawing its Improvement Measure for Project Management. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 26(2), 82–88. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I., & Shah, S. H. (2025). A Proposal for Evaluation Criteria of Decision Support System for BIM. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 26(2), 89–102. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R., Brilakis, I., Pikas, E., Xie, H. S., & Girolami, M. (2020). Construction with digital twin information systems. Data-Centric Engineering, 1, e14. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q., Parlikad, A. K., Woodall, P., Ranasinghe, G. D., Xie, Y., Liang, Z., & Konstantinou, E. (2020). Developing a digital twin at building and city levels: Case study of West Cambridge campus. Journal of Management in Engineering, 36(3), 05020004. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Li, M., Guo, D., Wu, W., Zhong, R. Y., & Huang, G. Q. (2022). Digital twin-enabled smart modular integrated construction system for on-site assembly. Computers in Industry, 136, 103594. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Zhao, N., Sun, L. et al. Modular based flexible digital twin for factory design. J Ambient Intell Human Comput 10, 1189–1200 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Al-Kahwati, K., Birk, W., Nilsfors, E. F., & Nilsen, R. (2022, June). Experiences of a digital twin based predictive maintenance solution for belt conveyor systems. In PHM Society European Conference (Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 1-8). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Tan, Y., & Zhang, A. (2023). Integrating digital twin and blockchain for smart building management. Sustainable Cities and Society, 99, 104514. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Joo, J.K.; Lee, G.J.; Kim, S.K. Basic Analysis for Form System of In-situ Production of Precast Concrete Members. In Proceedings of the 2011 Autumn Annual Conference of Construction Engineering and Management, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–30 October 2011; Volume 12, pp. 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.-Y.; Joo, J.-K.; Lee, G.-J.; Kim, S.-K. In-situ Production Analysis of Composite Precast Concrete Members of Green Frame. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2011, 11, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.J.; Lee, S.H.; Joo, J.K.; Kim, S.K. A Basic Study of In-Situ Production Process of PC Members. In Proceeding of the 2011 Autumn Annual Conference of the Architectural Institute of Korea, 2011 Oct 28-29, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011; Volume 31, pp. 263–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.J.; Joo, J.K.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.K. A Basic Study on the Arrangement of In-situ Production Module of the Composite PC Members. In Proceeding of the 2011 Autumn Annual Conference of the Korea Institute of Building Construction, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011 Oct 28-29, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011; Volume 11,pp. 29–30.

- Lim, J.; Kim, J.J. Dynamic optimization model for estimating in-situ production quantity of PC members to minimize environmental loads. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.-K.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. Algorithms for in-situ production layout of composite precast concrete members. Autom. Constr. 2014, 41, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. A process for the efficient in-situ production of precast concrete members. J. Reg. Assoc. Archit. Inst. Korea 2017, 19, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C. Construction Planning Model for In-situ Production and Installation of Composite Precast Concrete Frame. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Son, C.-B.; Kim, S. Scenario-based 4D dynamic simulation model for in-situ production and yard stock of precast concrete members. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2022, 22, 2320–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., & Kim, S. (2024). Environmental Impact Minimization Model for Storage Yard of In-Situ Produced PC Components: Comparison of Dung Beetle Algorithm and Improved Dung Beetle Algorithm. Buildings, 14(12), 3753. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.T.; Lee, M.S. A Study on the Site-production Possibility of the Prefabricated PC Components. In Proceeding of the 1992 Autumn Annual Conference of the Architectural Institute of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992 Oct 24, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992; Volume 12, pp. 629–636.

- Li, H.; Love, P.E. Genetic search for solving construction site-level unequal-area facility layout problems. Autom. Constr. 2000, 9, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, I.; Na, Y.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, S. Energy-efficient algorithms of the steam curing for the in situ production of precast concrete members. Energy Build. 2013, 64, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Kang, K. A Study on the effective inventory management by optimizing lot size in building construction. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2004, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Yu, J.H.; Kim, C.D. A Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) Determination Method considering Stock Yard Size; Korea Institute of Construction Engineering and Management, , Seoul, Republic of Korea: 2007; pp. 549–552.

- Lee, J.M.; Yu, J.H.; Kim, C.D.; Lee, K.J.; Lim, B.S. Order Point Determination Method considering Materials Demand Variation of Construction Site. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2008, 24, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, H.R.; Horman, M.J.; Minchin, R.E.; Chen, D. Improving labor flow reliability for better productivity as lean construction principle. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2003, 129, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-S.; Yu, J.-H.; Kim, C.-D. Economic Order Quantity(EOQ) Determination Process for Construction Material considering Demand Variation and Stockyard Availability. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, D. W., Sourani, A., Sertyesilisik, B., & Tunstall, A. (2013). Sustainable construction: analysis of its costs and benefits. American Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 1(2), 32-38.

- Volk, R., Stengel, J., & Schultmann, F. (2014). Building Information Modeling (BIM) for existing buildings—Literature review and future needs. Automation in Construction, 38, 109–127. [CrossRef]

- Osman, H.M.; Georgy, M.E.; Ibrahim, M.E. A hybrid CAD-based construction site layout planning system using genetic algorithms. Autom. Constr. 2003, 12, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Lam, K.-C.; Lam, M.C.-K. Dynamic construction site layout planning using max-min ant system. Autom. Constr. 2009, 19, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, H.; Wang, C.; Eng, K.S. Repertory grid technique in the development of Tacit-based Decision Support System (TDSS) for sustainable site layout planning. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.J. A Study of In-situ Production Management Model of Composite Precast Concrete Members. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Kim, S. Evaluation of CO2 Emission Reduction Effect Using In-situ Production of Precast Concrete Components. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2020, 19, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, D. G. J., Perera, S., & Osei-Kyei, R. (2021). "Digital Twins for the Built Environment: Learning from Conceptual and Process Models in Manufacturing." Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 10(4), 557–575.

- Kassem, M., Kelly, G., Dawood, N., Serginson, M., & Lockley, S. (2015). "BIM in Facilities Management Applications: A Case Study of a Large University Complex." Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 5(3), 261–277.

- Xu, Q., Wang, J., Gao, W., Ren, S., & Li, Z. (2024, October). Digital Twin: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. In Proceeding of the 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Science and Management Technology (pp. 731-740).

- Chen, C., Zhao, Z., Xiao, J., & Tiong, R. (2021). A conceptual framework for estimating building embodied carbon based on digital twin technology and life cycle assessment. Sustainability, 13(24), 13875.

- Tagliabue, L. C., Brazzalle, T. F., Rinaldi, S., & Dotelli, G. (2023). Cognitive Digital Twin Framework for Life Cycle Assessment Supporting Building Sustainability. In Cognitive Digital Twins for Smart Lifecycle Management of Built Environment and Infrastructure (pp. 177-205). CRC Press.

- Alizadehsalehi, S., Hadavi, A., & Huang, J. C. (2021). "From BIM to Extended Reality in AEC Industry." Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon), 26, 1–17.

- Zhang, Z., Wei, Z., Court, S., Yang, L., Wang, S., Thirunavukarasu, A., & Zhao, Y. (2024). A review of digital twin technologies for enhanced sustainability in the construction industry. Buildings, 14(4), 1113. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, S., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Najafi, M., Rahimian, F., Park, C., & Lee, D. (2024). Digital twin applications for overcoming construction supply chain challenges. Automation in Construction, 167, 105679. [CrossRef]

- Kosse, S., Forman, P., Stindt, J., Hoppe, J., König, M., & Mark, P. (2023, June). Industry 4.0 enabled modular precast concrete components: a case study. In International RILEM Conference on Synergising expertise towards sustainability and robustness of CBMs and concrete structures (pp. 229-240). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Nikoukar, S., & Tavakolan, M. (2025). A simulation-based approach to optimizing resource allocation and logistics in construction projects: a case study. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management.

- Na, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. A process for the efficient in-situ production of precast concrete members. J. Reg. Assoc. Archit. Inst. Korea 2017, 19, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.J. Dynamic simulation model for estimating in-situ production quantity of pc members. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 18, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Park, K.; Son, S.; Kim, S. Cost reduction effects of in-situ PC production for heavily loaded long-span buildings. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2020, 19, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Work | Process | Required labor | Work Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Form work | Mold installation | Two common labors | 2 |

| Cleaning | Two common labors | 2 | |

| Stirrup support installation | Two common labors | 1 | |

| Rebar and insert installation | Four common labors | 50 | |

| Concrete work | Release mold agent application | Two common labors | 2 |

| Concrete casting and compaction | Four common labors | 20 | |

| Surface finishing | Two common labors | 5 | |

| Curing work | Curing sheet installation | Two common labors | 720 |

| Steam curing | Two common labors | ||

| Demolding | One common labors | 10 | |

| Yard-Stock work | Yard-stock preparation | Two common labors | 2 |

| Hoisting | Two common labors | 6 | |

| Dismantling binding | One common labors | 5 | |

| Inspection | Each one of skilled and common labor | 60 | |

| Plastering | Each one of skilled and common labor | 100 | |

| PC installation | Lifting preparation and component binding | Two common labors | 2 |

| Lifting | Two common labors | 6 | |

| Alignment | Two common labors | 19 | |

| Final binding removal | One common labors | 5 |

| Category | Details | |

| Required Construction Duration (month) | 18 | |

| Applied construction Duration (month) | 8 | |

| Quantity (ea) | Column | 1,035 |

| Beam | 1,906 | |

| Production Cycle (day) | 2 | |

| Number of Molds (ea) | Column | 32 |

| Beam | 90 | |

| Lead-time (month) | 5 | |

| Number of Cranes (ea) | 3 | |

| Maximum yard stock area (㎡) | 15,235 m2 | |

| Item | unit | Value | |

| Construction time | month | 6.3 | |

| Number of molds | Column | ea | 22 |

| Beam | ea | 60 | |

| Lead-time | Months | 4.8 | |

| Cranes | ea | 3 | |

| Yard-stock area | ㎡ | 12,342 | |

| Item | unit | Value | |

| CO₂ emission | T-CO₂ | 40,423 | |

| Construction time | month | 6.5 | |

| Number of molds | Column | ea | 30 |

| Beam | ea | 91 | |

| Lead-time | Months | 5.1 | |

| Cranes | ea | 3 | |

| Yard-stock area | ㎡ | 15,729 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).