1. Theoretical Background

In human cognition, the interplay between old and new information often results in memory interference, a key contributor to retrieval failures. Since the early 20th century, interference theory has provided a foundational framework for understanding forgetting, positing that previously or subsequently learned information competes during retrieval(Postman & Underwood, 1973; Underwood, 1957). Proactive interference (PI)—where prior knowledge (e.g., A-B associations) disrupts the encoding or retrieval of new information (e.g., A-C associations)—and retroactive interference (RI)—where newer information impairs older memories—are the two primary types of interference(Anderson, 2003) . The current study focuses on PI, especially its manifestation within paired-associate learning paradigms, where high cue or content similarity between associations intensifies retrieval competition (Mensink, 1988).

PI reflects a core limitation of memory: its constrained ability to manage competing traces, particularly when learned materials share semantic or structural similarities. Underwood (1957) demonstrated that recall accuracy declines as the number of previously learned lists increases, highlighting cumulative PI driven by shared retrieval cues(Underwood, 1957). Conversely, a shift in material category—such as from fruits to professions—can produce a release from PI by reducing competition (Wickens, 1970). These findings emphasize the dual demands placed on the memory system: maintaining stability (retaining prior traces) while remaining adaptable to new inputs. Thus, PI exemplifies the cognitive challenge of balancing persistence of old memories with acquisition of new information.

1.1. Experimental Paradigm and the Role of MMFR

The paired-associate learning paradigm(also known as A-B, A-C paradigm) is a cornerstone of memory interference research(Martin, 1971; Postman & Gray, 1977), especially for studying similarity-based response competition. In the classic A-B, A-C paradigm, participants learn cue-overlap associate pairs (e.g., A-B followed by A-C), while control participants learn unrelated pairs (e.g., E-F followed by G-H). When recall of A-C is impaired relative to G-H, the resulting deficit is attributed to cue-based interference(Postman & Underwood, 1973). To enhance precision, we adapted this paradigm by treating cue overlap as a within-subject variable, controlling for individual differences while measuring PI through differences in recall performance for A-C versus G-H pairs.

Response competition theory posits that retrieval failures arise when multiple memory traces are simultaneously activated by the same cue, leading to interference (Postman & Underwood, 1973). In standard cued-recall tasks, where participants are required to retrieve only the newer List 2 responses (e.g., A-C), PI manifests as intrusions from older List 1 associations (e.g., A-B), which are often attributed to source monitoring failures (Johnson et al., 1993). However, such tasks make it difficult to determine whether the target trace is unavailable or merely inaccessible(Tulving & Pearlstone, 1966). To address this, the Modified Modified Free Recall (MMFR) paradigm(Barnes & Underwood, 1959) was developed. By permitting participants to freely recall both B and C for cue A, MMFR reduces output suppression demands and provides a more direct assessment of memory availability

1.2. Persistent Competition in MMFR and Its Computational Modeling

While MMFR was initially believed to eliminate retrieval competition by removing the need for selective output(Barnes & Underwood, 1959; Greeno et al., 1971; Postman & Stark, 1969) , subsequent research challenged this assumption. Cue overload—the activation of multiple associations by a single cue—and differences in associative strength (e.g., stronger encoding of A-C due to recency) suggest that competition persists even in MMFR (Anderson & Neely, 1996; Crowder, 1976; Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988). Thus, MMFR may reduce—but not abolish—retrieval competition, highlighting the continuing role of memory strength and cue similarity in interference.

The Search of Associative Memory (SAM) model offers a quantitative account of residual competition in MMFR (Raaijmakers, 2008; Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1981). SAM assumes that retrieval involves a sampling process where cues activate memory traces based on their associative strength. A probabilistic selection follows, governed by the ratio rule: P(retrieving item i) = strength of i / total strength of all candidates. Even in MMFR, competition remains when cue A activates both B and C. When associative strengths are similar, choice ambiguity increases, reducing recall accuracy. This is captured in entropy-like formulations of competition(Polyn et al., 2009). In contrast, when one association (e.g., A-B) is much stronger, its dominance reduces competition, improving retrieval efficiency.

In sum, although MMFR minimizes inhibitory demands by allowing both responses to be recalled, response competition remains due to cue overload and strength asymmetries, consistent with SAM predictions (Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988; Polyn et al., 2009). Stronger associations tend to dominate retrieval, delaying or suppressing weaker traces without invoking active inhibition. This non-inhibitory competition explains the persistence of PI in MMFR and underscores the importance of associative strength and cue similarity in shaping memory retrieval dynamics.

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

Building on the SAM model, the present study investigates how the relative encoding strength of pre-existing associations modulates proactive interference in an MMFR context, where both associated responses (B and C) are permitted for retrieval without selective output constraints. Specifically, the study manipulates List 1 encoding strength (A-B pairs) by comparing a single-study condition with a repeated-study condition , while keeping List 2 learning (A-C pairs) constant . Memory for List 2 is tested via MMFR, where cue A prompts free recall of both B and C.

To explore the temporal dynamics of PI and potential effects of memory consolidation, participants also complete a delayed MMFR test 24 hours later. This design enables examination of how encoding strength and temporal delay jointly modulate PI, focusing on retrieval competition absent strong inhibitory demands.

At immediate test, PI is expected to be strongest when both List 1 and List 2 are encoded once. Here, A-B and A-C associations possess comparable strength, maximizing cue-based competition (Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1981). This high ambiguity should reduce A-C recall due to cue overload (Underwood, 1957), resulting in impaired performance relative to a control condition (e.g., G-H pairs).

In contrast, when List 1 is studied three times and List 2 once, the stronger A-B associations are predicted to be retrieved first. According to SAM, this early retrieval reduces competition by resolving cue ambiguity, allowing subsequent retrieval of A-C. Although A-C may be recalled later in the output sequence, its accuracy should remain unaffected due to reduced competitive uncertainty.

In the MMFR paradigm, delayed testing after a 24-hour consolidation interval allows for the investigation of how consolidation-mediated changes in the representational structure of overlapping associations (e.g., A-B and A-C) affect proactive interference. Systems consolidation theory posits that memory traces undergo reorganization post-encoding, shifting from hippocampal to neocortical representations, which become more abstract and integrated (Squire et al., 1993). During this transition, overlapping memories may compete for consolidation resources, influencing their accessibility and competitive relationship.

If consolidation promotes integration between overlapping associations(Tompary & Davachi, 2017), retrieving B from List 1 could facilitate subsequent recall of C from List 2 by serving as an additional retrieval cue, thereby attenuating PI. Conversely, if consolidation enhances differentiation between A-B and A-C (Hulbert & Norman, 2015), retrieval of B may fail to support—and may even hinder—C retrieval. In this case, increased distinctiveness could limit the utility of shared cues and preserve or even intensify PI.

Therefore, the trajectory of PI following consolidation may depend on whether integration or differentiation dominates. Integration should reduce PI through cooperative retrieval, while differentiation may sustain or exacerbate PI via competitive dynamics.

This study aims to elucidate how encoding strength and consolidation jointly shape retrieval competition and PI, refining our understanding of memory dynamics in non-inhibitory recall contexts.

2. Methods

Experiments were approved by Tianjin Normal University’s Institutional Review Board. All participants read and signed an informed consent form and were compensated appropriately upon completion. The experiment was approved by the Ethics Committee of the host institution.

2.1. Participants

Based on prior research and an a priori power analysis (α = .05, power = .80, two-tailed), a sample size of 52 participants was determined to be sufficient to detect a medium effect size (f = 0.25)(Cohen, 2013). A total of 64 undergraduate students were recruited for the experiment. Data from two participants were excluded due to extremely low recall accuracy, leaving 62 participants (27 males, 35 females) in the final analysis. Participants ranged in age from 17 to 26 years (M = 20.21, SD = 1.79). Thirty-two participants were assigned to the one-time study condition for List 1, and 30 participants were assigned to the three-time study condition. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, were tested individually, provided informed consent prior to participation, and received appropriate compensation upon completion of the experiment.

2.2. Design

The experiment employed a 2 × 2 × 2 mixed factorial design. List 1 encoding strength, operationalized as the number of study repetitions for List 1 (one vs. three) was manipulated between participants, while pair type (Cue-overlap vs. Non-overlapping) and test time (immediate vs. 24-hour delayed) were manipulated within participants. The dependent variable was memory performance on the Modified Modified Free Recall (MMFR) test for list 2.

2.3. Materials

The verbal materials were selected from the Chinese Affective Words System(CAWS) (Wang et al., 2008). Thirty-six verbs and thirty-six nouns were chosen, along with 12 buffer words, resulting in a total of 84 words. The 36 verbs and 36 nouns were randomly assigned to four sets of 18 words each, with each set containing 9 verbs and 9 nouns. To ensure equivalence across sets, the average valence and familiarity ratings were obtained from 32 undergraduate students using a 7-point Likert scale. The mean familiarity ratings for the four sets were 5.590 ± 1.574, 5.653 ± 1.592, 5.658 ± 1.523, and 5.623 ± 1.653, with no significant differences among sets, F(3, 68) = 0.279, p = .840. The mean valence ratings were 4.708 ± 0.594, 4.776 ± 0.439, 4.611 ± 0.404, and 4.675 ± 0.385, also showing no significant differences, F(3, 68) = 0.396, p = .756.

The image materials were selected from the Bank of Standardized Stimuli (BOSS; Brodeur et al., 2010)(Brodeur et al., 2010). Sixty-six images depicting common objects and animals were chosen, including 12 buffer images. Of the remaining 54 images, 27 depicted familiar living things (e.g., mammals, birds, insects) and 27 depicted familiar objects (e.g., furniture, clothing, buildings, tools). These were randomly and evenly divided into three sets, each containing 9 living things and 9 objects. Familiarity ratings were obtained from 33 participants using a 7-point Likert scale. The mean familiarity ratings for the three sets were 6.401 ± 0.350, 6.465 ± 0.320, and 6.470 ± 0.337, with no significant differences, F(2, 51) = 0.236, p = .791.

To avoid spurious associations between specific pictures and words, the three picture sets and four word sets were randomly paired to form picture–word associations. In one set, the same pictures appeared in both List 1 and List 2 but were paired with different words to form overlapping A–B and A–C associations. The other two picture sets were paired with two separate word sets to form non-overlap E–F and G–H associations. All picture–word pairs were randomly assigned to different lists and association types.

2.4. Procedure

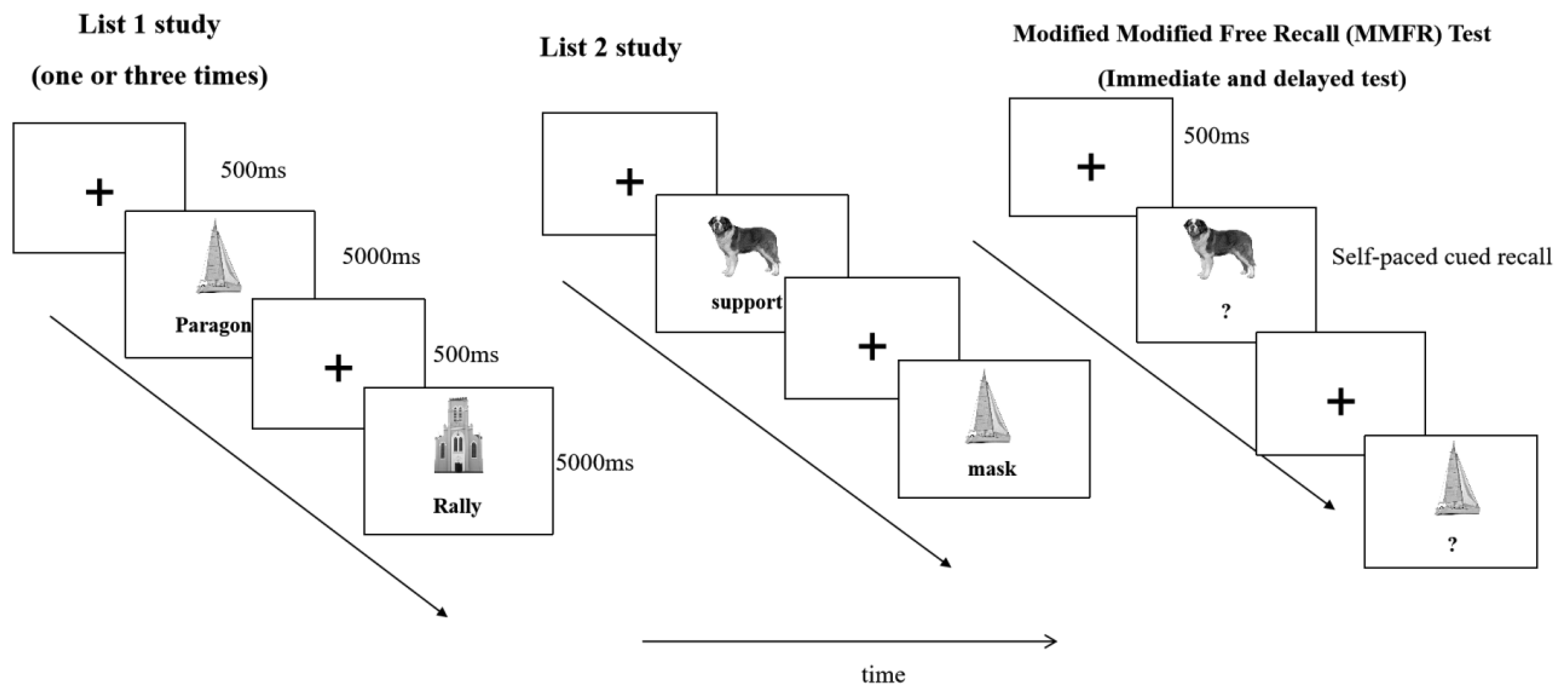

The experiment was programmed using PsychoPy 2024.2.4 and administered on a laptop computer with a 16-inch display (1920 × 1080 resolution; 60 Hz refresh rate). Images were presented in the upper central area of the screen (500 × 500 pixels), and words appeared directly below the images. To minimize primacy and recency effects, the first three and last three trials in the learning phases of both List 1 and List 2 were treated as buffer trials and excluded from statistical analyses. The experimental sequence is illustrated in

Figure 1.

List 1 learning phase. Each trial began with a fixation cross presented for 500 ms, followed by a picture–word pair. The image appeared in the upper central area of the screen, and the word appeared in the lower central area. Each pair remained on the screen for 5000 ms, during which participants were instructed to memorize the association between the picture and the word. Each list contained 42 pairs, with the first and last three pairs serving as buffers and excluded from analysis.

List 2 learning phase. Following List 1 learning, participants completed a 60-second backward counting task to prevent rehearsal. List 2 learning then proceeded in the same format and timing as List 1. In List 2, half of the pairs shared the same images as in List 1 but were paired with different words, forming overlapping A–B and A–C associations. The other half consisted of pairs with entirely new pictures and words, forming nonoverlapping E–F and G–H associations.

Cued recall phase. After List 2 learning, participants completed a 3-minute backward counting task before the cued recall test. In this phase, only the image from each studied pair was presented at the center of the screen. Participants were instructed to recall and type the word(s) associated with that image. If an image had been paired with two different words across List 1 and List 2, participants were allowed to provide both responses. The task was self-paced. Following the immediate cued recall test, participants returned after a 24-hour interval to complete a second cued recall test on the same materials, using identical procedures to assess the effects of consolidation on memory performance.

3. Result

Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.5.0 (R Core Team, 2025)

3.1. Cued Recall Performance for List 2

A 2 (List 1 encoding strength: one vs. three study repetitions) × 2 (pair type: cue-overlap vs. Non-overlap) × 2 (test time: immediate vs. 24-hour delayed) mixed ANOVA on cued-recall accuracy revealed significant main effects of List 1 encoding strength, F(1, 60) = 7.11, p = .010, generalized η² = .057, with higher recall in the three-repetition condition than in the one-repetition condition, and test time, F(1, 60) = 28.54, p < .001, generalized η² = .207, with higher recall at the immediate test than at the delayed test. There was also a significant main effect of pair type, F(1, 60) = 18.73, p < .001, generalized η² = .102, such that non-overlap pairs were recalled more accurately than cue-overlap pairs.

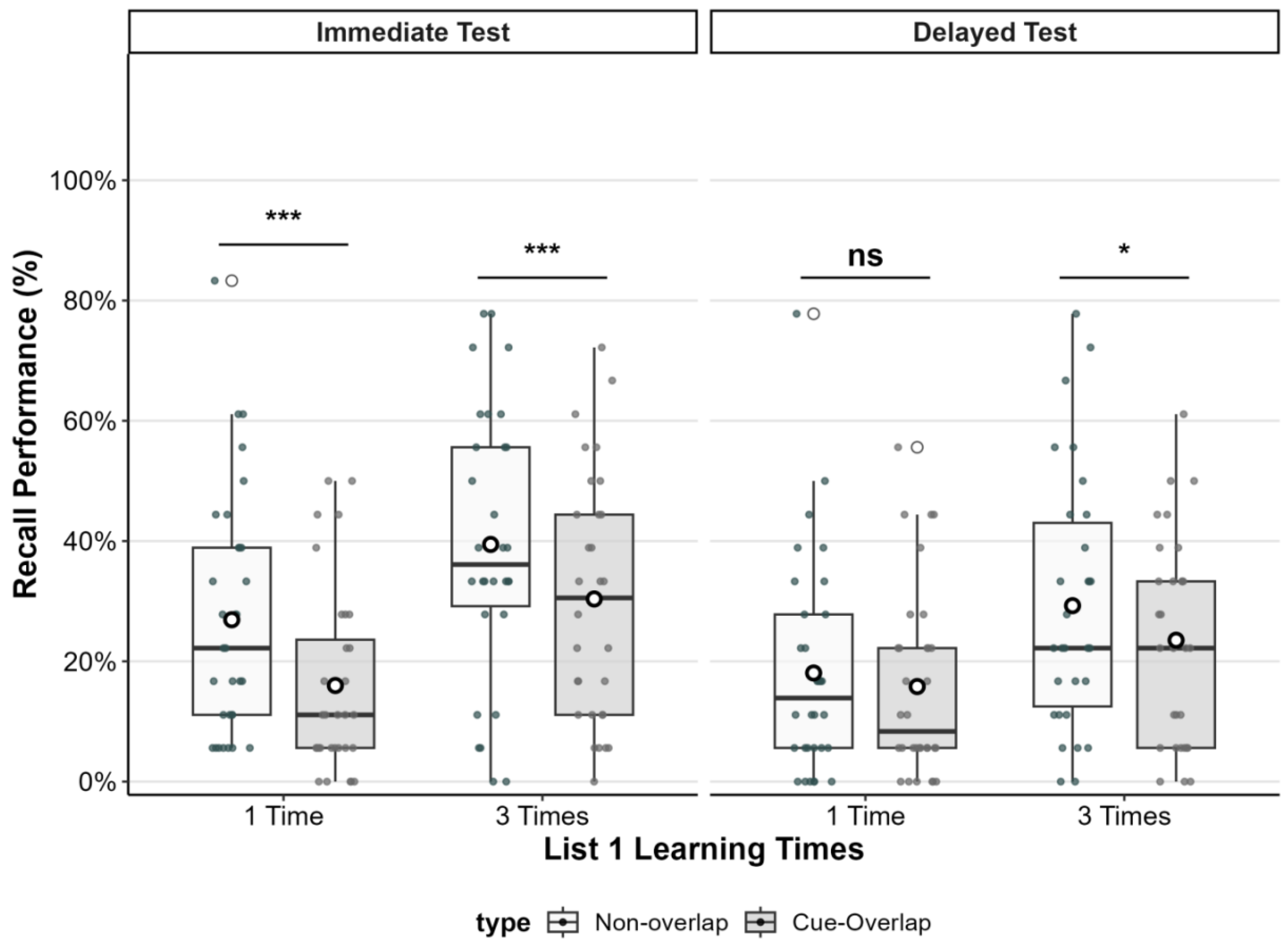

The test time and pair type interaction was significant, F(1, 60) = 11.57, p = .001, generalized η² = .046. Follow-up comparisons showed that the recall advantage for non-overlap over cue-overlap pairs was larger at the immediate test (Mdifference = 0.10, SE = 0.017, t(60) = 5.76, p < .001, Cohen’s d =0.73 ) than at the delayed test (Mdifference = 0.04, SE = 0.019, t(60)=2.06, p = .044, Cohen’s d =0.26).

No other interactions reached significance, including the test time and List 1 encoding strength interaction, F(1, 60) = 2.70, p = .106, the pair type and List 1 encoding strength interaction, F(1, 60) = 0.06, p = .803, and the three-way interaction, F(1, 60) = 2.30, p = .135. Means and standard deviations for all experimental conditions are presented in Table 1, and the magnitude of proactive interference (PI) across conditions is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Mean Proportion of Correct Recall for List 2 as a Function of Cue Overlap and Test Delay.

Table 1.

Mean Proportion of Correct Recall for List 2 as a Function of Cue Overlap and Test Delay.

| List 1 Encoding Strength |

Pair Type |

Immediate Test(IT) |

Delayed Test(DT)

|

| N |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

| One Time |

Cue-Overlap

(A-C) |

32 |

0.160 |

0.154 |

0.158 |

0.157 |

Non-overlap

(G-H) |

32 |

0.269 |

0.202 |

0.181 |

0.179 |

| Three Times |

Cue-Overlap

(A-C) |

30 |

0.304 |

0.207 |

0.235 |

0.174 |

Non-overlap

(G-H) |

30 |

0.394 |

0.227 |

0.293 |

0.213 |

Figure 2.

Proactive interference (PI) effects as a function of List 1 learning repetitions and test time. The boxplots display recall performance (%) for non-overlap (white boxes) and cue-overlap (gray boxes) pairs in the immediate and delayed tests. Circles represent individual participant scores; horizontal lines indicate medians; white dots within boxes represent condition means. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, ns = nonsignificant.

Figure 2.

Proactive interference (PI) effects as a function of List 1 learning repetitions and test time. The boxplots display recall performance (%) for non-overlap (white boxes) and cue-overlap (gray boxes) pairs in the immediate and delayed tests. Circles represent individual participant scores; horizontal lines indicate medians; white dots within boxes represent condition means. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, ns = nonsignificant.

3.2. Effects of List 1 Encoding Strength and Retrieval Delay on Proactive Interference

To further examine whether cue-overlap elicited proactive interference under different learning and testing conditions, pairwise comparisons were conducted between the cue-overlap and non-overlap pairs within each combination of List 1 Encoding Strength (one vs. three) and test time (immediate vs. delayed).

In the immediate test condition, participants recalled significantly fewer items in the cue-overlap condition compared to the non-overlap condition, regardless of list 1 encoding strength. When List 1 was encoded once (matching the List 2 ), recall was significantly lower in the cue-overlap condition (

M difference = 0.11,

SE = 0.024,

t(60) = 4.52,

p < .001, Cohen’s

d = 0.58), indicating a robust proactive interference effect. Similarly, when List 1 was encoded three times, recall was also significantly lower in the cue-overlap condition

In contrast, in the delayed test condition, the interference effect was attenuated. When List 1 was encoded once, there was no significant difference in recall between cue-overlap and non-overlap conditions (M difference = 0.02, SE = 0.027, t(60) = 0.84, p = .41, Cohen’s d = 0.11), indicating that proactive interference was not evident. However, when List 1 was encoded three times, a small but statistically significant interference effect was observed (M difference = 0.06, SE = 0.028, t(60) = 2.06, p = .044, Cohen’s d = 0.26).

These results suggest that proactive interference arising from cue overlap was strongest during immediate testing, particularly when List 1 was encoded once. Delayed testing reduced the magnitude of this interference, and it was no longer evident in the one-repetition condition, although a small residual effect persisted when List 1 was encoded three times.

3.3. Associative Dependency Analysis

To examine whether the joint retrieval of B and C items exceeded the level expected under independent retrieval, we computed a deviation index for each participant by subtracting the expected joint probability (P(B) × P(C)) from the observed co-retrieval probability (P(B ∩ C)). Positive deviation values indicate that B and C were retrieved together more frequently than predicted under the independence assumption.

To assess whether the joint retrieval of items B and C exceeded the level expected under independent recall, separate one-sample t tests were conducted on deviation scores for each combination of encoding strength and test time. Across all conditions, deviation scores were significantly greater than zero, indicating reliable associative dependency between B and C. When List 1 was encoded once and tested immediately, deviation scores were significantly positive (M = 0.016), t(31) = 2.50, p = .018, Cohen’s d = 0.44. When List 1 was encoded once and tested after a delay, a similar significant deviation was observed (M = 0.022), t(31) = 2.95, p = .006, Cohen’s d = 0.52. For participants who encoded List 1 three times and were tested immediately, the deviation was also significant and larger in magnitude (M = 0.026), t(29) = 3.65, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 0.67.

A 2 (List 1 encoding strength: one vs. three study repetitions) × 2 (test time: immediate vs. 24-hour delayed) mixed-design ANOVA on the deviation scores revealed no significant main effect of encoding strength, F(1, 60) = 0.55, p = .461, generalized η² = .008, and no significant main effect of test time, F(1, 60) = 0.86, p = .358, generalized η² = .002. The interaction between encoding strength and test time was also not significant, F(1, 60) = 0.82, p = .368, generalized η² = .002. These results indicate that the degree of dependency between B and C retrieval did not vary as a function of study repetitions or retention interval.

Overall, the findings demonstrate a robust and consistent associative dependency between B and C, with participants recalling the two items together more often than expected under independent retrieval, regardless of encoding strength or retention interval.

4. Discussion

The present study examined how the relative encoding strength of pre-existing associations (A–B) influences proactive interference (PI) in the Modified Modified Free Recall (MMFR) paradigm, and whether memory consolidation modulates this effect over time. We hypothesized that when A–B and A–C associations have comparable strength (one study repetition each), cue-based retrieval competition would be maximal, leading to pronounced PI at immediate test. In contrast, when A–B is more strongly encoded (three repetitions) than A–C (one repetition), the large disparity in associative strength was expected to reduce retrieval competition, thereby attenuating PI in recall accuracy, although A–C might still be recalled later in the output sequence (Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1981; Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988). At delayed test, we further predicted that PI could either persist or diminish depending on whether consolidation promotes integration (reducing competition) or differentiation (maintaining or increasing competition) between overlapping associations (Hulbert & Norman, 2015; Tompary & Davachi, 2017).

The results partially supported these predictions. At immediate test, robust PI was observed under both encoding conditions, but the effect was stronger when A–B and A–C had equal encoding strength, consistent with the Search of Associative Memory (SAM) model’s prediction that competition peaks when associative strengths are similar (Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1980; 1981). When A–B was more strongly encoded, PI was still significant but smaller in magnitude, suggesting that reduced ambiguity following reliable A–B retrieval can facilitate subsequent A–C recall. At delayed test, PI disappeared in the equal-strength condition, consistent with the possibility that consolidation reduced competition or increased integration between overlapping associations (Tompary & Davachi, 2017). However, in the strong A–B condition, a small but significant PI effect persisted, indicating that when a dominant competitor is well established, it may continue to interfere with weaker associations over time (Anderson & Neely, 1996).

Importantly, the co-retrieval analysis revealed significant positive deviations from the independence assumption across all conditions, demonstrating a robust associative dependency between B and C. This suggests that, regardless of encoding strength or retention interval, retrieval of one associate (e.g., B) was more likely to co-occur with retrieval of the other (C) than would be expected by chance. Such dependency is consistent with the notion that overlapping associations can form an interconnected representational network, allowing activation to spread between them during recall(Collins & Quillian, 1995; McClelland et al., 1995) . The persistence of this dependency even when PI was attenuated at delayed test implies that associative links between competing items remain intact and may facilitate cooperative retrieval under certain conditions, especially in a non-selective recall context like MMFR (Barnes & Underwood, 1959; Postman & Stark, 1969).

Taken together, these findings highlight the dual nature of cue-overlap effects in memory retrieval. While overlapping associations can compete during retrieval, producing PI when their strengths are similar, they can also exhibit cooperative retrieval dynamics, as reflected in the consistent associative dependency between B and C. The balance between these competitive and cooperative processes appears to depend on both relative encoding strength and the effects of consolidation over time.

This pattern of concurrent competition and cooperation can be further interpreted within the integration–differentiation framework of memory consolidation. From this perspective, overlapping associations (A–B and A–C) may undergo two partially opposing processes over time. Integration promotes the binding of related traces into a more interconnected network, increasing cross-cue accessibility and enabling cooperative retrieval, as reflected in the robust associative dependency observed across all conditions (Tompary & Davachi, 2017). Differentiation, in contrast, strengthens the distinctiveness of competing traces, reducing cross-association activation but preserving each item’s unique retrieval route, which can maintain or even heighten PI when the stronger competitor remains highly accessible (Hulbert & Norman, 2015; Schlichting & Preston, 2015).

The present results suggest that both processes may operate simultaneously, with their relative influence depending on the interplay between initial encoding strength and consolidation. When A–B and A–C are equally encoded, integration may dominate over time, reducing competition and attenuating PI while preserving associative links that enable co-retrieval. When A–B is substantially stronger, differentiation may prevent B from facilitating access to C, allowing residual competition to persist even after consolidation. This dual-process view helps reconcile the observed persistence of associative dependency with the selective attenuation of PI, emphasizing that cue overlap can yield both interference and facilitation, depending on the balance between integration and differentiation mechanisms.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the present study warrant consideration. First, while the observed co-retrieval patterns are consistent with the possibility that both integration and differentiation processes contribute to the dynamics of proactive interference, the current behavioral data cannot decisively disentangle these mechanisms. Without direct neural or process-tracing evidence (e.g., neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computational modeling), the interpretation of integration versus differentiation remains speculative. Future studies may benefit from incorporating neurocognitive measures (e.g., fMRI pattern similarity analyses or hippocampal activity tracking) to more precisely characterize the nature of representational change across delays.

Second, the MMFR paradigm, although useful for reducing output interference, does not eliminate all task demands or strategic factors. Participants may vary in how they approach retrieval when allowed to report multiple responses, which may confound the measurement of associative dependency. Future research could explore task variants that better isolate automatic versus strategic retrieval dynamics, such as speeded retrieval tasks or confidence-based responding.

Third, our manipulation of encoding strength relied solely on repetition frequency. Other encoding dimensions—such as elaboration, distinctiveness, or associative variability—may influence retrieval competition and consolidation differently. Subsequent investigations might examine whether qualitatively different forms of learning modulation produce similar or divergent patterns of PI and associative dependency.

Finally, while the inclusion of a 24-hour delay enabled a preliminary examination of consolidation effects, more nuanced temporal sampling (e.g., shorter and longer retention intervals) and sleep monitoring would provide stronger evidence for the role of consolidation-related processes. Such extensions could clarify whether integration and differentiation unfold in parallel or sequentially and how they interact with cue overload and retrieval history over time.

6. Conclusion

The present study investigated how the relative encoding strength of overlapping associations and the passage of time jointly shape proactive interference (PI) within a Modified Modified Free Recall (MMFR) paradigm. The findings demonstrate that retrieval competition is modulated by initial encoding conditions and retention interval. Strong PI emerged when competing associations shared similar strength, consistent with the notion of cue-based competition. When one association was more strongly encoded, PI was attenuated, likely due to reduced ambiguity in retrieval. Notably, PI effects diminished after a 24-hour delay in the equal-strength condition, suggesting that consolidation processes can alter competitive retrieval dynamics.

Moreover, across all conditions, associative dependency between overlapping responses remained robust, indicating that co-retrieval of competing items may be supported by an integrated memory structure even when interference is reduced. These results suggest that interference and facilitation can coexist in overlapping associative networks, with their relative expression shaped by encoding history and consolidation.

Taken together, the present findings underscore the complexity of interference phenomena, pointing to the interplay of multiple mechanisms—such as retrieval competition, associative strength, and consolidation-driven representational change. A fuller understanding of PI may therefore require moving beyond unitary models of inhibition or competition toward more integrative accounts that consider both conflict and cooperation in memory retrieval.

Authors' contributions

Yahui Zhang: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Visualization,Writing – original draft. Xiping Liu: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Weihai Tang: Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Normal University (Project identification code: 2024052105) on 21 May 2024.

Consent to participate

All subjects signed informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the final manuscript and consented to its submission.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The analysis code used in this study is available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Open Practices Statement

None of the experiments was preregistered. Data and materials supporting the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

References

- Anderson, M. (2003). Rethinking interference theory: Executive control and the mechanisms of forgetting. Journal of Memory and Language, 49(4), 415–445. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. C., & Neely, J. H. (1996). Interference and Inhibition in Memory Retrieval. In Elsevier eBooks (p. 237). Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J. M., & Underwood, B. J. (1959). “Fate” of first-list associations in transfer theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58(2), 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, M. B., Dionne-Dostie, E., Montreuil, T., & Lepage, M. (2010). The Bank of Standardized Stimuli (BOSS), a New Set of 480 Normative Photos of Objects to Be Used as Visual Stimuli in Cognitive Research. PLOS ONE, 5(5), e10773. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Collins, A. M., & Quillian, M. R. (1995). Retrieval time from semantic memory. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 8(2), 240–247. [CrossRef]

-

Crowder, R. G. (1976).Principles of learning and memory. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Greeno, J. G., James, C. T., & Da Polito, F. J. (1971). A cognitive interpretation of negative transfer and forgetting of paired associates. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 10(4), 331–345. [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, J. C., & Norman, K. A. (2015). Neural Differentiation Tracks Improved Recall of Competing Memories Following Interleaved Study and Retrieval Practice. Cerebral Cortex, 25(10), 3994–4008. [CrossRef]

- McClelland, B, L, McNaughton, R, C, & O’Reilly. (1995). Why there are complementary learning systems in the hippocampus and neocortex: Insights from the successes and failures of connectionist models of learning and memory. Psychological Review.

- Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114(1), 3–28. [CrossRef]

- Martin, E. (1971). Verbal learning theory and independent retrieval phenomena. Psychological Review, 78(4), 314–332. [CrossRef]

- Mensink. (1988). A Model for Interference and Forgetting. Psychological Review, 95(4), 434–455. [CrossRef]

- Polyn, S. M., Norman, K. A., & Kahana, M. J. (2009). A context maintenance and retrieval model of organizational processes in free recall. Psychological Review, 116(1), 129–156. [CrossRef]

- Postman, L., & Gray, W. (1977). Maintenance of Prior Associations and Proactive Inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 3, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Postman, L., & Stark, K. (1969). Role of response availability in transfer and interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 79(1, Pt.1), 168–177. [CrossRef]

- Postman, L., & Underwood, B. J. (1973). Critical issues in interference theory. Memory & Cognition, 1(1), 19–40. [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J. G. W. (2008). Mathematical models of human memory. Learning & Memory a Comprehensive Reference. [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, & Shiffrin, R. M. (1981). Search of associative memory. Psychological Review, 88(2), 93–134. [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, M. L., & Preston, A. R. (2015). Memory integration: Neural mechanisms and implications for behavior. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 1, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Squire, L. R., Knowlton, B., & Musen, G. (1993). The Structure and Organization of Memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(Volume 44, 1993), 453–495. [CrossRef]

- Tompary, A., & Davachi, L. (2017). Consolidation Promotes the Emergence of Representational Overlap in the Hippocampus and Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron, 96(1), 228-241.e5. [CrossRef]

- Tulving, E., & Pearlstone, Z. (1966). Availability versus accessibility of information in memory for words. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 5(4), 381–391. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, J. (1957). INTERFERENCE AND FORGETTING. 64(1), 49–60. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. N., Zhou, L. M., & Luo, Y. J. (2008). The Pilot Establishment and Evaluation of Chinese Affective Words System. Chinese Mental Health Journal. [CrossRef]

- Wickens, D. D. (1970). Encoding categories of words: An empirical approach to meaning. Psychological Review, 77(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).