Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

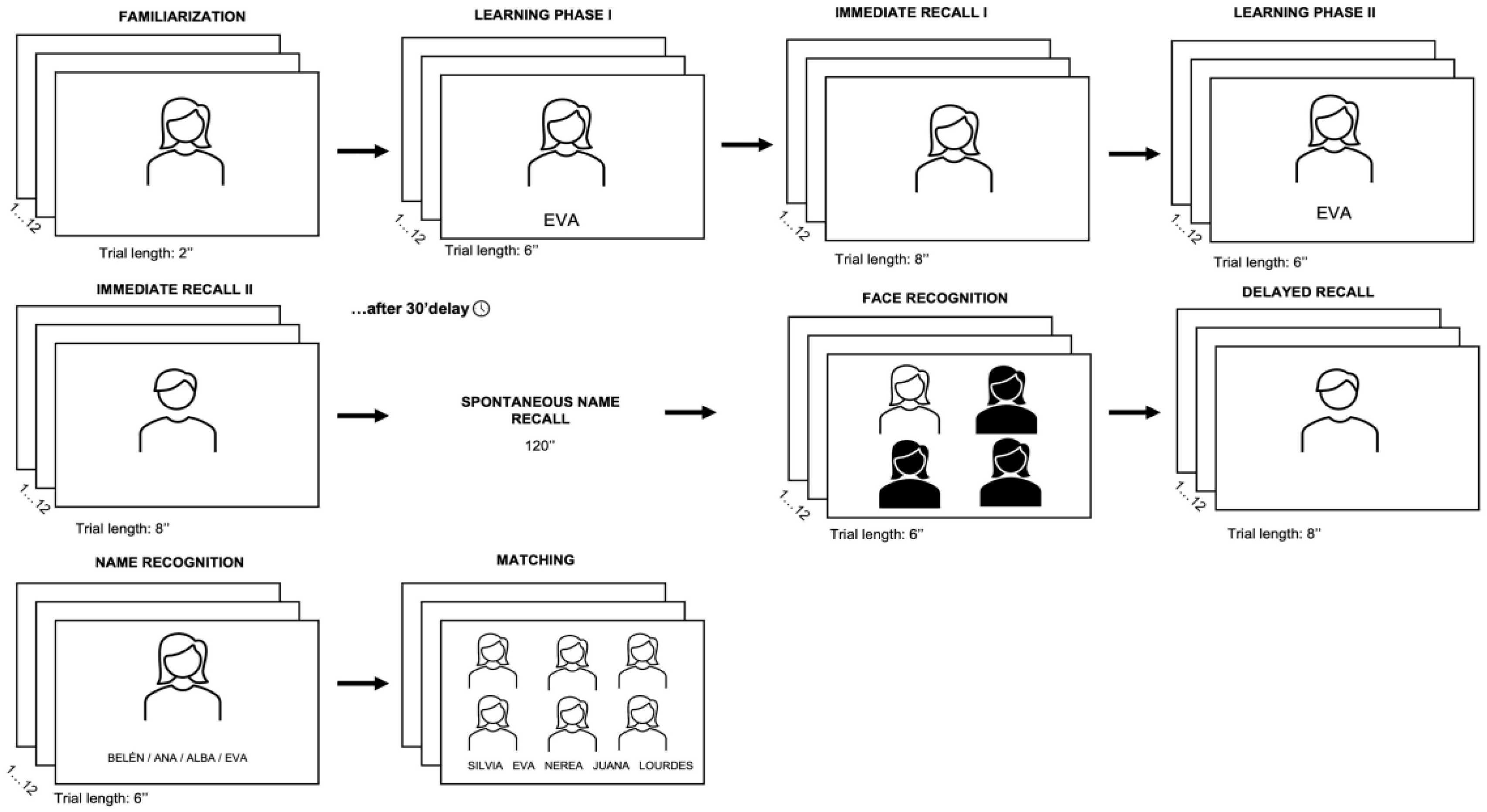

2.3. Material and Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Aspects and Data Security

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (March 31, 2023). Aging and health. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs404/en/.

- Greer, T.L.; Kurian, B.T.; Trivedi, M.H. Defining and Measuring Functional. CNS Drugs 2010, 24, 267-284. [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Thornicroft, G. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1560-1571. [CrossRef]

- Vigo, D.; Thornicroft, G.; Atun, R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 171-178. [CrossRef]

- Butters, M.A.; Young, J.B.; Lopez, O.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Mulsant, B.H.; Reynolds III, C.F.; Becker, J.T. Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 10, 345. [CrossRef]

- Hammar, A.; Ardal, G. Verbal memory functioning in recurrent depression during partial remission and remission-Brief report. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 652. [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.J.; Air, T.; Baune, B. T. The role of cognitive impairment in psychosocial functioning in remitted depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 235, 129-134.. [CrossRef]

- Paelecke-Habermann, Y.; Pohl, J.; Leplow, B. Attention and executive functions in remitted major depression patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 89, 125-135. [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.J.; Gallagher, P.; Thompson, J.M.; Young, A.H. Neurocognitive impairment in drug-free patients with major depressive disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 182, 214-220. [CrossRef]

- Salagre, E.; Solé, B.; Tomioka, Y.; Fernandes, B.S.; Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Garriga, M.; Grande, I. Treatment of neurocognitive symptoms in unipolar depression: A systematic review and future perspectives. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 221, 205-221. [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Che, W.; Min-Wei, W.; Murakami, Y.; Matsumoto, K. (2006). Impairment of the spatial learning and memory induced by learned helplessness and chronic mild stress. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006, 83, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, C.; Hervás, G.; Hernangómez, L.; Romero, N. Modelos cognitivos de la depresión: Una síntesis y nueva propuesta basada en 30 años de investigación. Psicol. Conductual 2010, 18, 139.

- Trivedi, M.H.; Greer, T.L. Cognitive dysfunction in unipolar depression: Implications for treatment. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 152, 19-27. [CrossRef]

- Elgamal, S.; Denburg, S.: Marriott, M.; MacQueen, G. Clinical factors that predict cognitive function in patients with major depression. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2010, 55, 653-661. [CrossRef]

- Hammar, Å.; Ronold, E.H.; Rekkedal, G.Å. Cognitive impairment and neurocognitive profiles in major depression-a clinical perspective. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 764374. [CrossRef]

- James, T.A.; Weiss-Cowie, S.; Hopton, Z.; Verhaeghen, P.; Dotson, V.M.; Duarte, A. Depression and episodic memory across the adult lifespan: A metaanalytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 147, 1184. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, D.G.; Pizzagalli, D.A. Mechanisms of memory disruption in depression. Trends Neurosci. 2018, 41, 137-149. [CrossRef]

- LeMoult, J.; Gotlib, I.H. Depression: A cognitive perspective. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 69, 51-66. [CrossRef]

- Ramponi, C.; Murphy, F.C.; Calder, A.J.; Barnard, P.J. Recognition memory for pictorial material in subclinical depression. Acta Psychol. 2010, 135, 293-301. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, S.S.; Folstein, M.F. Memory complaint, memory performance, and psychiatric diagnosis: A community study. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 1993, 6, 105-111. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.D.; Gerndt, J. Somatization, depression and medical illness in psychiatric inpatients. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1988, 77, 67-73. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Dartigues, J. F.; Mazaux, J.; Dequae, L.; Letenneur, L.; Giroire, J.M.; Barberger-Gateau, P. Self-reported memory complaints and memory performance in elderly french community residents: Results of the PAQUID research program. Neuroepidemiology 1994, 13, 145-154. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, D.W.; Pollitt, P.A.; Roth, M.; Brook, C.P.B.; Reiss, B.B. Memory complaints and impairment in normal, depressed, and demented elderly persons identified in a community survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1990, 47, 224-227. [CrossRef]

- Rohling, M.L.; Green, P.; Allen, L.M.; Iverson, G.L. Depressive symptoms and neurocognitive test scores in patients passing symptom validity tests. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2002, 17, 205-222. [CrossRef]

- Sachs-Ericsson, N.; Carr, D.; Sheffler, J.; Preston, T.J.; Kiosses, D.; Hajcak, G. Cognitive reappraisal and the association between depressive symptoms and perceived social support among older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 453-461. [CrossRef]

- Au, A.; Cheng, C.; Chan, I.; Leung, P.; Li, P.; Heaton, R.K. Subjective memory complaints, mood, and memory deficits among HIV/AIDS patients in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2008, 30, 338-348. [CrossRef]

- Derouesné, C.; Lacomblez, L.; Thibault, S.; LePoncin, M. Memory complaints in young and elderly subjects. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 14, 291-301. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, T.; Cardoso, S.; Guerreiro, M.; Maroco, J.; Silva, D.; Alves, L.; de Mendonça, A. Memory awareness in patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 137, 411-418. [CrossRef]

- Sinforiani, E.; Zucchella, C.; Pasotti, C. Cognitive disturbances in nondemented subjects: Heterogeneity of neuropsychological pictures. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2007, 44, 375-380. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175-1184. [CrossRef]

- Villamarín, F. Papel de la auto-eficacia en los trastornos de ansiedad y depresión. Análisis y Modificación de conducta 1990, 16, 55-79.

- Montejo, P.; Montenegro, M.; Claver, M.; Reinoso, A.; De Andrés, M.; García, A. Quejas subjetivas de memoria en adultos jóvenes y su relación con rendimiento de memoria, depresión, calidad de vida y rasgos de personalidad. Alzheimer (Barc., Internet), 2013, 6-15.

- Randolph, J.J.; Arnett, P.A.; Freske, P. Metamemory in multiple sclerosis: Exploring affective and executive contributors. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2004, 19, 259-279. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, D.J. Self-efficacy and depression. In Schwarzer, R (Ed.) Self-efficacy and depression. Self-efficacy: Thought control of action. Taylor & Francis, 1992, pp. 177-193.

- Lippke, S. Self-Efficacy Theory. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer 2020. [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Meier, L.J. Self-Efficacy and Depression. In Maddux, J.E. (Ed.) Self-Efficacy, Adaptation, and Adjustment. The Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology. Springer 1995. [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, M.; Desrichard, O. Are memory self-efficacy and memory performance related? A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 211. [CrossRef]

- Comijs, H.C.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Dik, M.G.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Jonker, C. Memory complaints; the association with psycho-affective and health problems and the role of personality characteristics: A 6-year follow-up study. J. Affect. Disord. 2002, 72, 157-165. [CrossRef]

- Derouesné, C.; Rapin, J.R.; Lacomblez, L. Memory complaints in 200 subjects meeting the diagnostic criteria for age-associated memory impairment: Psychoaffective and cognitive correlates. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 2004, 2, 67-74.

- Alegret, M.; García-Gutiérrez, F.; Muñoz, N.; Espinosa, A.; Ortega, G.; Lleonart, N.; Boada, M. (2024). FACEmemory®, an innovative online platform for episodic memory pre-screening: Findings from the first 3,000 participants. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 97, 1173-1187. [CrossRef]

- Zandi, T. Relationship between subjective memory complaints, objective memory performance, and depression among older adults. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen. 2004, 19, 353-360. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, S.; Frey, B.N.; Schneider, M.A.; Kapczinski, F.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T. Functional and cognitive impairment in the first episode of depression: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2022, 145, 156–185. [CrossRef]

- Crumley, J.J.; Stetler, C.A.; Horhota, M. Examining the relationship between subjective and objective memory performance in older adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 250. [CrossRef]

- Kriesche, D.; Woll, C.F.; Tschentscher, N.; Engel, R.R.; Karch, S. Neurocognitive deficits in depression: A systematic review of cognitive impairment in the acute and remitted state. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 273, 1105-1128. [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.M. The role of the hippocampus in recognition memory. Cortex 2017, 93, 155-165. [CrossRef]

- Chirico, M.; Custer, J.; Shoyombo, I.; Cooper, C.; Meldrum, S.; Dantzer, R.; Toups, M.S. Kynurenine pathway metabolites selectively associate with impaired associative memory function in depression. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 8, 100126. [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, D. A.; Curiel, R. E.; Duara, R.; Buschke, H. (2017). Novel cognitive paradigms for the detection of memory impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Assessment 2017, 25, 348-359. [CrossRef]

- Rentz, D.M.; Amariglio, R.E.; Becker, J.A.; Frey, M.; Olson, L.E.; Frishe, K.; Sperling, R.A.. Face-name associative memory performance is related to amyloid burden in normal elderly. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 2776-2783. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Cheval, B.; Becker, B.; Herold, F.; Chan, C.C.H.; Delevoye-Turrell, Y.N.; Zou, L. Episodic Memory Encoding and Retrieval in Face-Name Paired Paradigm: An fNIRS Study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 951. [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; Valero, S.; Ortega, G.; Espinosa, A.; Sanabria, A.; Hernández, I.; Boada, M. Validation of the Spanish version of the Face Name Associative Memory Exam (S-FNAME) in cognitively normal older individuals. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2015a, 30, 712-720. doi.: 10.1093/arclin/acv050.

- Alegret, M.; Rodríguez, O.; Espinosa, A.; Ortega, G.; Sanabria, A.; Valero, S.; Boada, M. Concordance between subjective and objective memory impairment in volunteer subjects. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015b, 48, 1109-1117. [CrossRef]

- Amariglio, R.E.; Frishe, K.; Olson, L.E.; Wadsworth, L.P.; Lorius, N.; Sperling, R. A.; Rentz, D. M. Validation of the Face Name Associative Memory Exam in cognitively normal older individuals. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2012, 34, 580-587. [CrossRef]

- Enriquez-Geppert, S.; Flores-Vázquez, J.F.; Lietz, M.; Garcia-Pimenta, M.; Andrés, P. I know your face but can’t remember your name: Age-related differences in the FNAME-12NL. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Vázquez, J.F.; Rubiño, J.; Contreras-López, J.J.; Contreras, C.C.; Sosa-Ortiz, A.L.; Enriquez-Geppert, S.; Andres, P. Worse associative memory recall in healthy older adults compared to young ones, a face-name study in Spain and Mexico. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2021, 43, 558-567. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Vázquez, J.F.; Contreras-López, J.J.; Stegeman, R.; Castellanos-Maya, O.; Ćurčić-Blake, B.; Andrés, P.; Enriquez-Geppert, S. Extended FNAME performance is preserved in subjective cognitive decline but highly affected in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology 2023, 37, 650. [CrossRef]

- Rentz, D.M.; Weiss, B. K.; Jacobs, E.G.; Cherkerzian, S.; Klibanski, A.; Remington; A.; Goldstein, J.M. Sex differences in episodic memory in early midlife: Impact of reproductive aging. Menopause 2017, 24, 400. [CrossRef]

- Rubiño, J.; Andrés, P. The Face-Name Associative Memory Test as a tool for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1464. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.; Simões, M.R.; Alves, L.; Vicente, M.; Santana, I. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Validation study for vascular dementia. J. Int. Neuropsycol. Soc. 2012, 18, 1031-1040. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Dunbar, G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59, 22-33. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Åsberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382-389. [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.; Chamorro, L.; Luque, A.; Dal-Ré, R.; Badia, X.; Baró, E.; Grupo de Validación en Español de Escalas Psicométricas (GVEEP). (2002). Validación de las versiones en español de la Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale y la Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale para la evaluación de la depresión y de la ansiedad. Med. Clin. 2002, 118, 493-499. [CrossRef]

- Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Carmody, T.J.; Arnow, B.; Klein D.K.; Keller M. B. The 16-Item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinical rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 573-583. [CrossRef]

- Gili, M.; Lopez-Navarro, E.; Homar, C.; Castro, A.; García-Toro, M.; Llobera, J.; Roca, M. Psychometric properties of Spanish version of QIDS-SR16 in depressive patients. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2014, 42, 292-299.

- Siquier, A.; Andrés, P. Face name matching and memory complaints in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1051488. [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, A.; Harris, J.E.; Gleave, J. Memory failures in everyday life following severe head injury. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1984, 6, 127-142. [CrossRef]

- Lozoya-Delgado, P.; Ruiz-Sánchez de León, J.M.; Pedrero-Pérez, E.J. Validación de un cuestionario de quejas cognitivas para adultos jóvenes: Relación entre las quejas subjetivas de memoria, la sintomatología prefrontal y el estrés percibido. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 54, 137-50.

- Nasreddine, Z. S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695-699. [CrossRef]

- Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving research involving human subjects. 2013. Available online: Shorturl.at/sNUV4 (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Cohen, J. A power primer. In. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research (4th ed.). APA PsycNet 2016, pp. 279-284. [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.J.; Lyrtzis, E.; Baune, B. T. The association of cognitive deficits with mental and physical Quality of Life in Major Depressive Disorder. Comprehensive psychiatry 2020, 97, 152147. [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S.J.; Juster, R.P.; Raymond, C.; Marin, M.F.. The effects of chronic stress on the human brain: From neurotoxicity, to vulnerability, to opportunity. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 49, 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Schwert, C.; Stohrer, M.; Aschenbrenner, S.; Weisbrod, M.; Schröder, A. (2018). Biased neurocognitive self-perception in depressive and in healthy persons. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 96-102. [CrossRef]

- Dotson, V.M.; McClintock, S.M.; Verhaeghen, P.; Kim, J.U.; Draheim, A.A.; Syzmkowicz, S.M.; Wit, L.D. Depression and cognitive control across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2020, 30, 461-476. [CrossRef]

- Albus, M.; Hubmann, W.; Wahlheim, C.; Sobizack, N.; Franz, U.; Mohr, F. Contrasts in neuropsychological test profile between patients with first-eoisode schizophienia and first-episohe affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1996, 94, 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.; Nicholl, B.I.; Mackay, D.F.; Martin, D.; Ul-Haq, Z.; McIntosh, A.; Smith, D.J. Cognitive function and lifetime features of depression and bipolar disorder in a large population sample: Cross-sectional study of 143,828 UK Biobank participants. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 950-958. [CrossRef]

- Fossati, P.; Ergis, A.M.; Allilaire, J.F.. Qualitative analysis of verbal fluency in depression. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 117, 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Kyte, Z.A.; Goodyer, I.M.; Sahakian, B.J. Selected executive skills in adolescents with recent first episode major depression. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 995-1005. [CrossRef]

- van Eijndhoven, P.; van Wingen, G.; Fernández, G.; Rijpkema, M.; Verkes, R.J.; Buitelaar, J.; Tendolkar, I. Amygdala responsivity related to memory of emotionally neutral stimuli constitutes a trait factor for depression. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 1677-1684. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Gong, B.; Li, H.; Bai, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; He, W.; Li, T.; Wang, YT. Mechanisms of hippocampal long-term depression are required for memory enhancement by novelty exploration. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 11980-11990. [CrossRef]

- Dzib-Goodin, A.; Sanders, L.; Yelizarov, D. Sistemas Neuro-Moleculares necesarios para el proceso de memoria. Cuadernos de Neuropsicología/Panamerican Journal of Neuropsychology 2017, 11.

- Halvorsen, M.; Sundet, K.; Eisemann, M.; Wang, C.E.A. Verbal learning and memory in depression: A 9-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 188, 350-354. [CrossRef]

- Lahr, D.; Beblo, T.; Hartje, W. Cognitive performance and subjective complaints before and after remission of major depression. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 2007, 12, 25-45. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Blasco, M.; Torres, I.J.; Vicent-Gil, M.; Goldberg, X.; Navarra-Ventura, G.; Aguilar, E.; Cardoner, N. Discrepancy between objective and subjective cognition in major depressive disorder. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 46-56. [CrossRef]

- Della Sala, S.; Parra, M.A.; Fabi, K.; Luzzi, S.; Abrahams, S.. Short-term memory binding is impaired in AD but not in non-AD dementias. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 833–840. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Pertzov, Y.; Nicholas, J.M.; Henley, S.M.D.; Crutch, S.; Woodward, F.;Husain, M. Visual short-term memory binding deficit in familial Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 2016, 78, 150–164. [CrossRef]

- Bezdicek, O.; Ballarini, T.; Buschke, H.; Růžicka, F.; Roth, J.; Albrecht, F.;Jech, R. Memory impairment in Parkinson’s disease: The retrieval versus associative deficit hypothesis revisited and reconciled. Neuropsychology 2019, 33, 391-405. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M.; Giannoylis, I.; De Belder, M.; Saint-Cyr, J.A.; McAndrews, M.P. Associative reinstatement memory measures hippocampal function in Parkinson’s Disease. Neuropsychologia 2016, 90, 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Miebach, L.; Wolfsgruber, S.; Frommann, I.; Buckley, R.; Wagner, M. Different Cognitive Complaint Profiles in Memory Clinic and Depressive Patients. Am. J. Geriatr Psychiatry 2018, 26, 463-475. [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, R.; Hänninen, T.; Honkalampi, K.; Hintikka, J.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Viinamäki, H. Mood improvement reduces memory complaints in depressed patients. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2001, 251, 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Velasco, C.; Guillaume, S.; Olié, E.; Alacreu-Crespo, A.; Cazals, A.; Courtet, P. Decision-making in major depressive disorder: Subjective complaint, objective performance, and discrepancy between both. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 270, 102-107. doi; 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.064.

- Farrin, L.; Hull, L.; Unwin, C.; Wykes, T.; David, A. Effects of depressed mood on objective and subjective measures of attention. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 15, 98-104. [CrossRef]

- Mohn, C.; Rund, B.R. Neurocognitive profile in major depressive disorders: Relationship to symptom level and subjective memory complaints. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, S.; Kievit, R.A.; Emery, T.; Henson, R.N. Symptoms of depression in a large healthy population cohort are related to subjective memory complaints and memory performance in negative contexts. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 104-114. [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, J.C.; Murphy, N.Z. Personality and metamemory correlates of memory performance in younger and older adults. Educ. Gerontol. 1986, 12, 385-394. [CrossRef]

- Bhang, I.; Mogle, J.; Hill, N.; Whitaker, E.B.; Bhargava, S. Examining the temporal associations between self-reported memory problems and depressive symptoms in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1864-1871. [CrossRef]

- O'Shea, D.M.; Dotson, V.M.; Fieo, R.A.; Tsapanou, A.; Zahodne, L.; Stern, Y. Older adults with poor self-rated memory have less depressive symptoms and better memory performance when perceived self-efficacy is high. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 783-790. [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.; Coleman, K.; Jesso, S., Jodoin, V.D., Smolewska, K.; Warriner, E.; Pasternak, S.H. Depressive symptoms negatively impact Montreal Cognitive Assessment performance: A memory clinic experience. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 432, 513-517. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Nieto, J.M.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Prevalencia de probable deterioro cognitivo en adultos mayores de una población mexicana utilizando el MMSE y el MoCA. Gerokomos 2021, 32, 168-171.

| FED | HCtrl | p-value | rrb/ η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 3 (20%) | 8 (53.33%) | ||

| Females | 12 (80%) | 7 (46.66%) | ||

| Age | 50.20 (8.04) | 45.07 (8.64) | .06 | .35 |

|

Education (years) MFE-30 MoCA |

10.30 (2.49) 43.33 (25.40) 22.02 (5.21) |

16.27 (3.47) 19.66 (10.12) 53.73 (7.05) |

.001 .05 .22 |

.73 .14 .05 |

| FED | HCtrl | p-value | η 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate Recall I | 5.26 (3.26) | 7.5 (2.25) | .71 | .01 |

| Immediate Recall II | 7 (3.29) | 9.93 (1.98) | .93 | .01 |

| Total IR (I + II) | 12.26 (6.55) | 17.43(4.23) | .87 | .01 |

| Spontaneous name Recall | 8.06 (2.89) | 9.66 (1.98) | .45 | .02 |

| Face recognition | 11.86 (0.35) | 11.86 (0.50) | .96 | .01 |

| Delayed recall | 8.26 (3.39) | 10 (2.06) | .61 | .01 |

| Name recognition | 11.80 (0.41) | 11.93 (0.25) | .50 | .01 |

| Matching (Association) | 9.53 (3.14) | 11.53 (0.72) | .47 | .02 |

| Total score | 61.80 (14.99) | 72.46 (7.65) | .86 | .01 |

| MoCA | TIR | SNR | RD | Matching | Total score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFE-30 | -.08 | -.04 | -.029 | -.032 | -.24 | -.045 |

| MoCA | .66** | .62** | .54** | .49** | .67** | |

| Total IR | .79** | .79** | .70** | .96** | ||

| SNR | .85** | .71** | .90** | |||

| DR | .78** | .90** | ||||

| Matching | .80** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).