Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Associative Interference in Episodic Memory

1.2. Two-Factor Interference Theory: Retrieval Competition and Associative Unlearning

1.3. Encoding-Based Accounts: Integration, Differentiation, and Similarity-Based Interference

1.4. The Present Work

2. Method

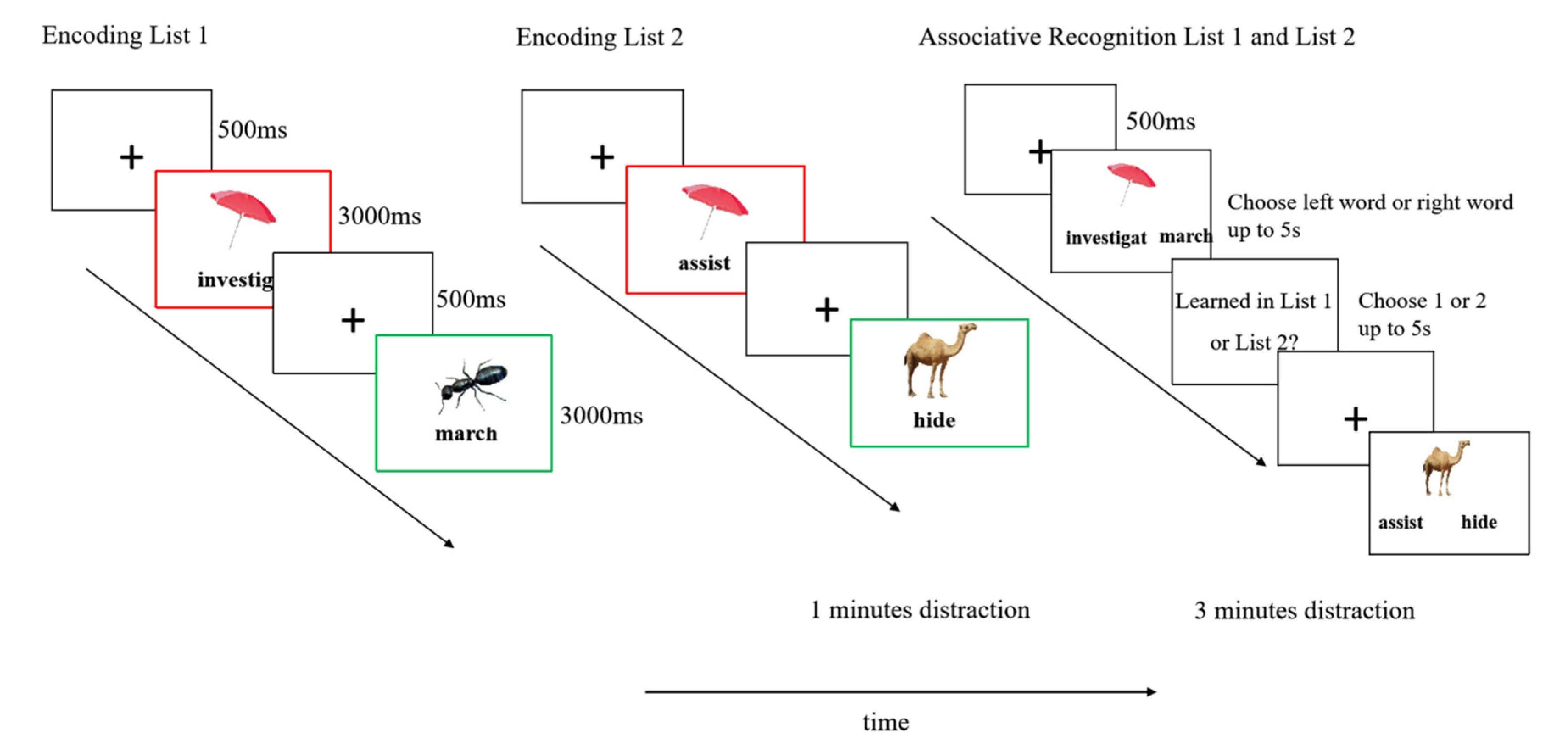

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials

2.4. Experimental Pairings Were as Follows:

2.5. Procedure.

3. Results

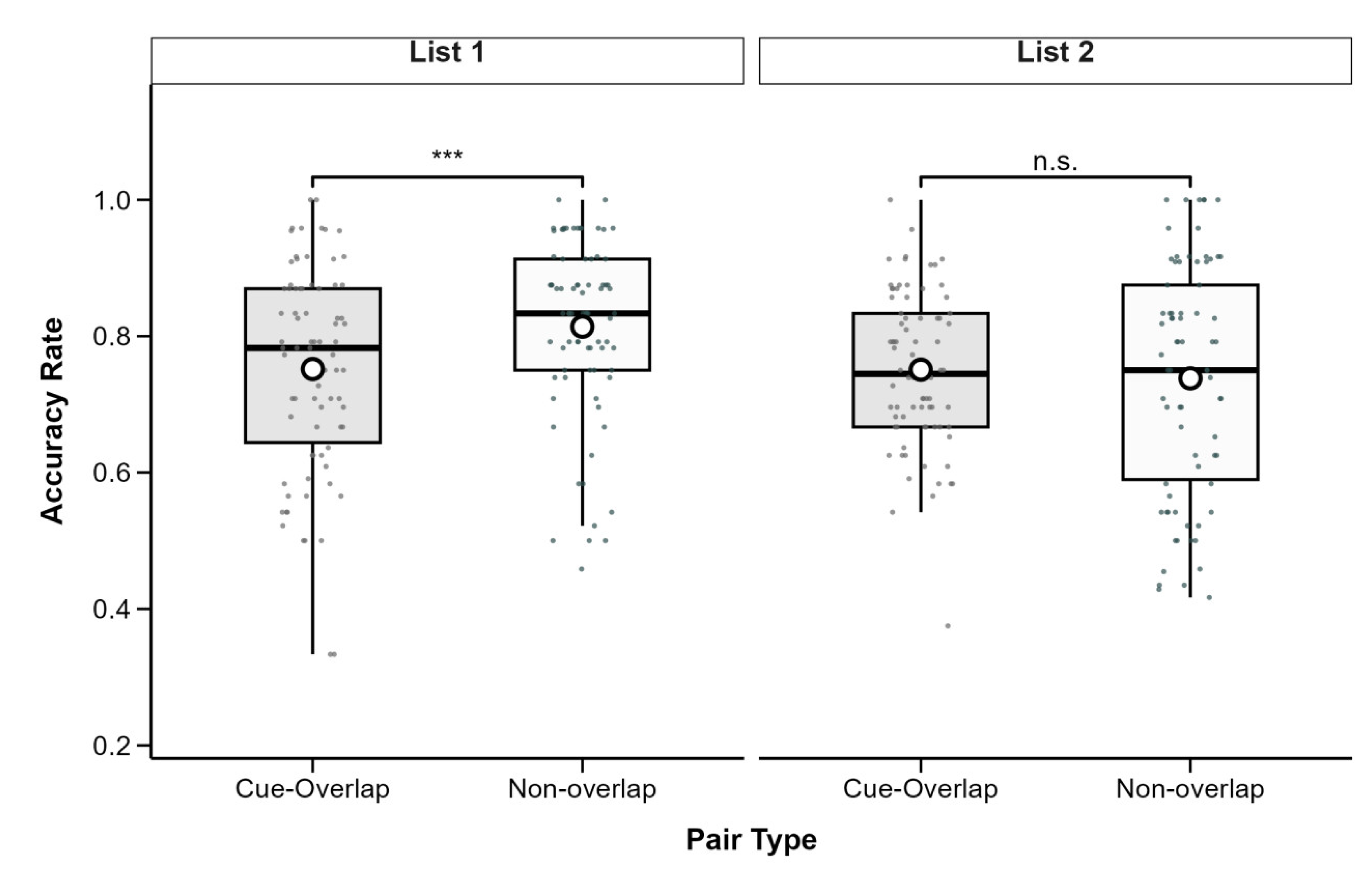

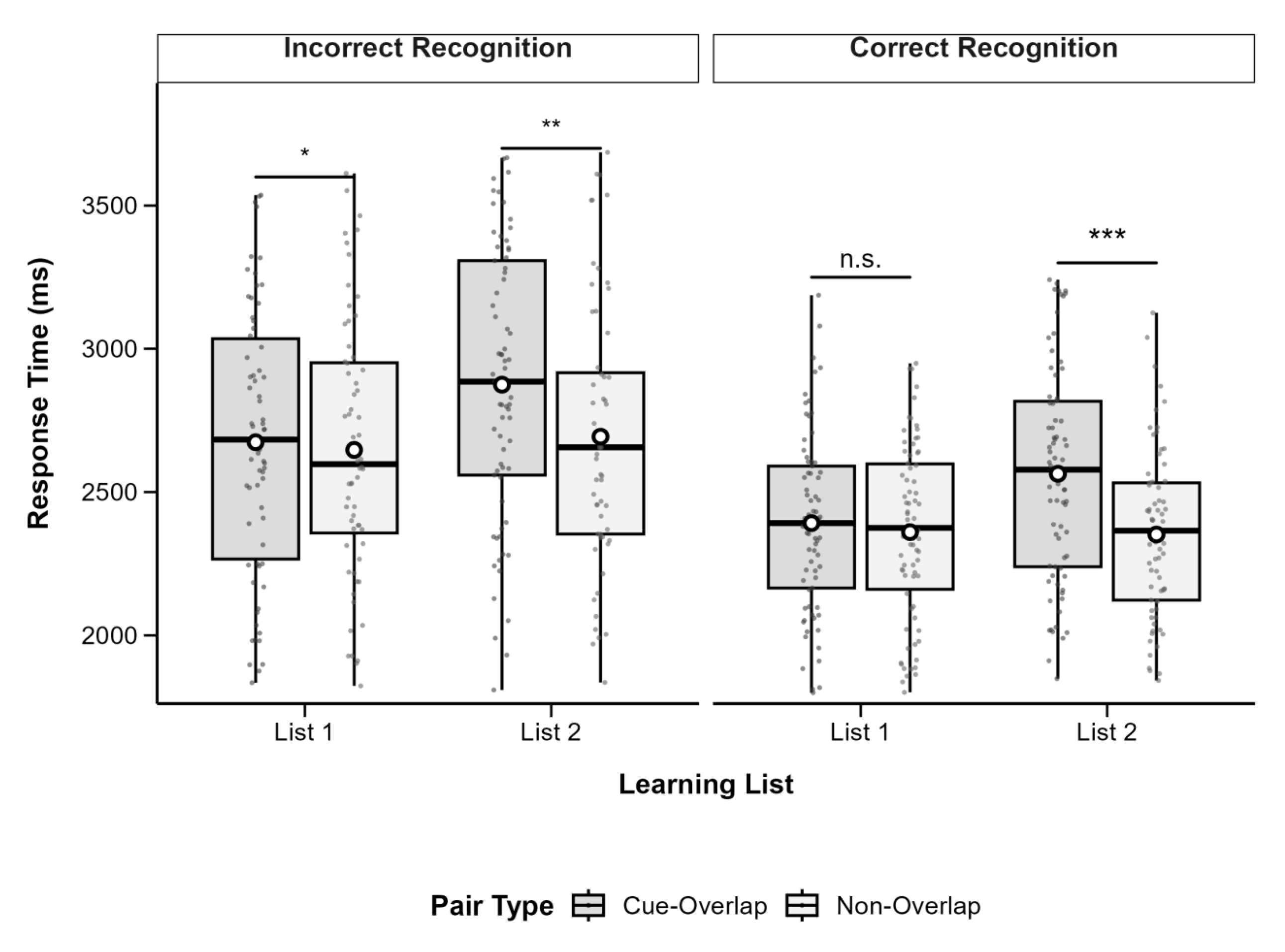

3.1. Associative Recognition Results

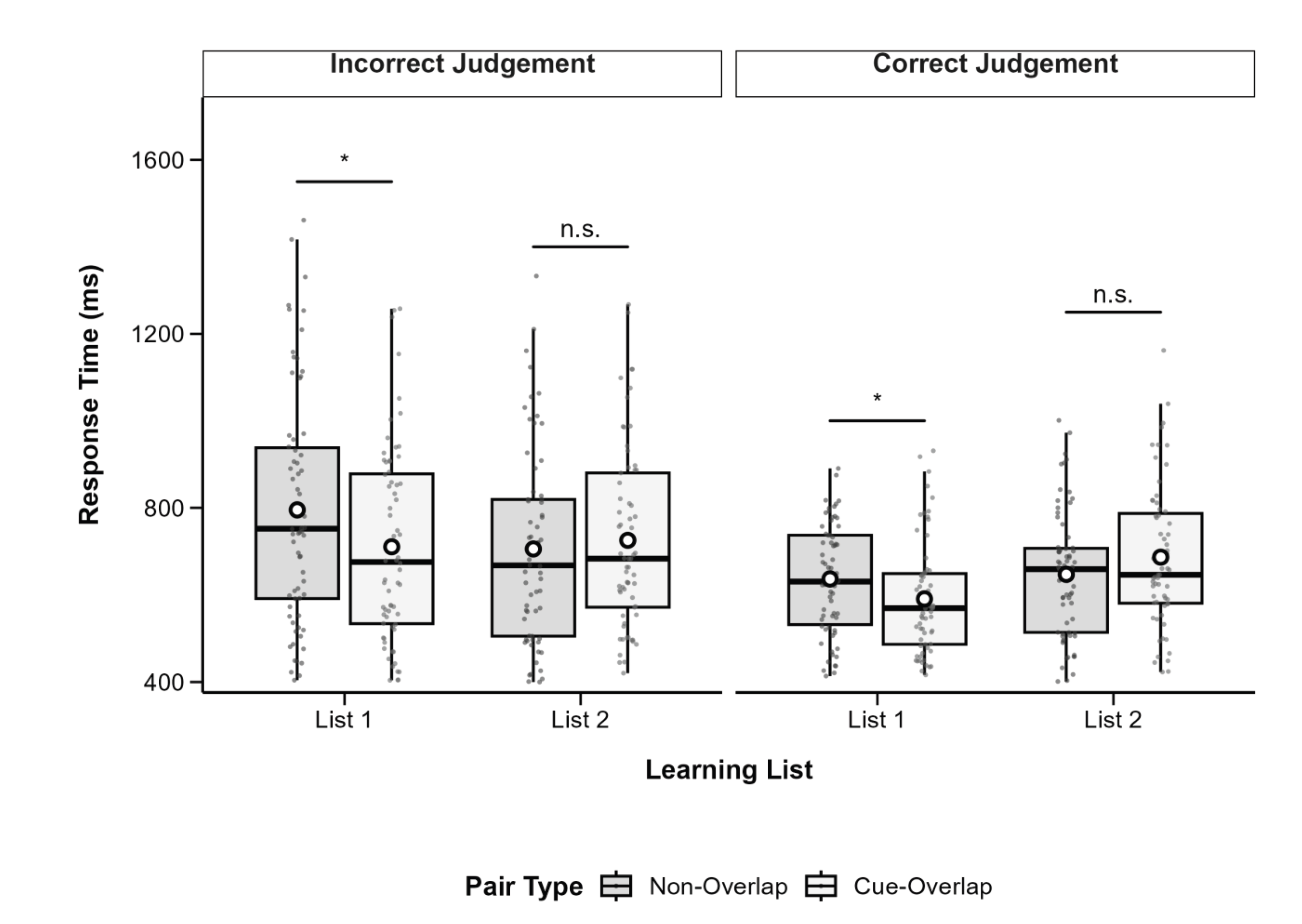

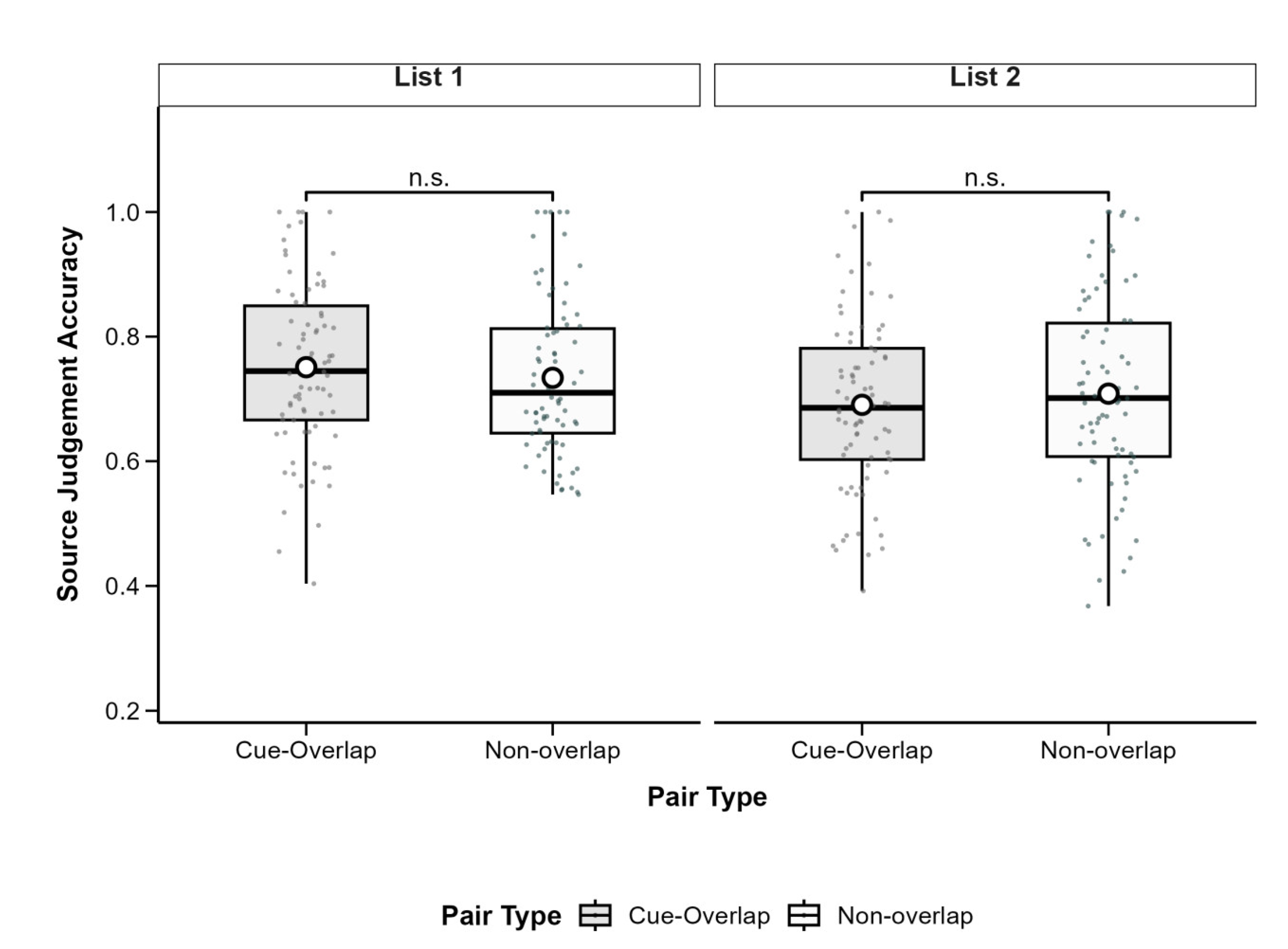

3.2. Source Judgement Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Memory Interference Persists Beyond Retrieval Competition

4.2. The Central Role of Encoding in Interference Mechanisms

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Authors Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, J. R. , & Reder, L. M. (1999). The fan effect: New results and new theories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. C. , Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1994). Remembering can cause forgetting: Retrieval dynamics in long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, M. B. , Dionne-Dostie, E., Montreuil, T., & Lepage, M. (2010). The Bank of Standardized Stimuli (BOSS), a New Set of 480 Normative Photos of Objects to Be Used as Visual Stimuli in Cognitive Research. ( 5(5), e10773. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, G. H. (1972). Stimulus-sampling theory of encoding variability. In A. W. Melton & E. Martin (Eds.), Coding Processes in Human Memory (pp. 85–121). Washington, DC: Winston.

- Chanales, A. J. H. , Dudukovic, N. M., Richter, F. R., & Kuhl, B. A. (2019). Interference between overlapping memories is predicted by neural states during learning. A. ( 10(1), 5363. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. (2019). Short-term memory based on activated long-term memory: A review in response to Norris (2017). Psychological Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M. T. , Cowan, N., & Sala, S. D. (2007). Forgetting Due to Retroactive Interference: A Fusion of Müller and Pilzecker’s (1900) Early Insights into Everyday Forgetting and Recent Research on Anterograde Amnesia. Cortex. [CrossRef]

- Favila, S. E. , Chanales, A. J. H., & Kuhl, B. A. (2016). Experience-dependent hippocampal pattern differentiation prevents interference during subsequent learning. Nature Communications. [CrossRef]

- Favila, S. E. , Lee, H., & Kuhl, B. A. (2020). Transforming the Concept of Memory Reactivation. A. ( 43(12), 939–950. [CrossRef]

- Gabitov, E. , Lungu, O., Albouy, G., & Doyon, J. (2019). Weaker Inter-hemispheric and Local Functional Connectivity of the Somatomotor Cortex During a Motor Skill Acquisition Is Associated With Better Learning. Frontiers in Neurology. [CrossRef]

- Herszage, J. , & Censor, N. (2017). Memory Reactivation Enables Long-Term Prevention of Interference. Current Biology, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, A. J. , Bisby, J. A., Bush, D., Lin, W.-J., & Burgess, N. (2015). Evidence for holistic episodic recollection via hippocampal pattern completion. ( 6(1), 7462. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijbers, W. , Pennartz, C. M., Cabeza, R., & Daselaar, S. M. (2009). When Learning and Remembering Compete: A Functional MRI Study. PLoS Biology, 0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, J. C. , & Norman, K. A. (2015). Neural Differentiation Tracks Improved Recall of Competing Memories Following Interleaved Study and Retrieval Practice. A. ( 25(10), 3994–4008. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. , Norman, K. A., & Turk-Browne, N. B. (2017). Neural Differentiation of Incorrectly Predicted Memories. B. ( 37(8), 2022–2031. [CrossRef]

- Koen, J. D. , & Rugg, M. D. (2016). Memory Reactivation Predicts Resistance to Retroactive Interference: Evidence from Multivariate Classification and Pattern Similarity Analyses. The Journal of Neuroscience, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, B. A. , Bainbridge, W. A., & Chun, M. M. (2012). Neural Reactivation Reveals Mechanisms for Updating Memory. The Journal of Neuroscience, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, B. A. , Rissman, J., Chun, M. M., & Wagner, A. D. (2011). Fidelity of neural reactivation reveals competition between memories. D. ( 108(14), 5903–5908. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, B. A. , Shah, A. T., DuBrow, S., & Wagner, A. D. (2010). Resistance to forgetting associated with hippocampus-mediated reactivation during new learning. Nature Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. J. , & Anderson, M. C. (2002). Inhibitory processes and the control of memory retrieval. C. ( 6(7), 299–305. [CrossRef]

- Luck, S. J. , & Vogel, E. K. (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. K. ( 390(6657), 279–281. [CrossRef]

- Martin, E. (1968). Stimulus meaningfulness and paired-associate transfer: An encoding variability hypothesis. Psychological Review. [CrossRef]

- Martin, E. (1971). Verbal learning theory and independent retrieval phenomena. Psychological Review. [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, J. A. (1932). Forgetting and the law of disuse. Psychological Review. [CrossRef]

- Mensink. (1988). A Model for Interference and Forgetting. ( 95(4), 434–455. [CrossRef]

- Mensink,; Raaijmakers, J. G. W. (1989). A model for contextual fluctuation. G. W. ( 33(2), 172–186. [CrossRef]

- Moscovitch, M. , Cabeza, R., Winocur, G., & Nadel, L. (2016). Episodic Memory and Beyond: The Hippocampus and Neocortex in Transformation. Annual Review of Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Norman, K. A. , Newman, E. L., & Detre, G. (2007). A neural network model of retrieval-induced forgetting. Psychological Review. [CrossRef]

- Norman, K. A. , & O’Reilly, R. C. (2003). Modeling hippocampal and neocortical contributions to recognition memory: A complementary-learning-systems approach. Psychological Review. [CrossRef]

- Polack, C. W. , Jozefowiez, J., & Miller, R. R. (2017). Stepping back from ‘persistence and relapse’ to see the forest: Associative interference. Behavioural Processes. [CrossRef]

- Postman, L. , & Gray, W. (1977). Maintenance of Prior Associations and Proactive Inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. [CrossRef]

- Postman, L. , & Underwood, B. J. (1973). Critical issues in interference theory. Memory & Cognition. [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers,; Shiffrin, R. M. (1981). Search of associative memory. M. ( 88(2), 93–134. [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, C. (2010). Binding items and contexts: The cognitive neuroscience of episodic memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science. [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, R. , & McKoon, G. (2008). The diffusion decision model: Theory and data for two-choice decision tasks. Neural Computation. [CrossRef]

- Renoult, L. , Davidson, P. S. R., Schmitz, E., Park, L., Campbell, K., Moscovitch, M., & Levine, B. (2015). Autobiographically Significant Concepts: More Episodic than Semantic in Nature? An Electrophysiological Investigation of Overlapping Types of Memory. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Richter, F. R. , Chanales, A. J. H., & Kuhl, B. A. (2016). Predicting the integration of overlapping memories by decoding mnemonic processing states during learning. A. ( 124, 323–335. [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, V. J. H. , Nguyen, A., Turk-Browne, N. B., & Norman, K. A. (2024a). A neural network model of differentiation and integration of competing memories. A. ( 12, RP88608. [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, V. J. H. , Nguyen, A., Turk-Browne, N. B., & Norman, K. A. (2024b). Differentiation and Integration of Competing Memories: A Neural Network Model, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, V. J. H. , Turk-Browne, N. B., & Norman, K. A. (2019). Nonmonotonic Plasticity: How Memory Retrieval Drives Learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Sajikumar, S. , Morris, R. G. M., & Korte, M. (2014). Competition between recently potentiated synaptic inputs reveals a winner-take-all phase of synaptic tagging and capture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, M. L. , & Preston, A. R. (2015). Memory integration: Neural mechanisms and implications for behavior. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Shohamy, D. , & Wagner, A. D. (2008). Integrating Memories in the Human Brain: Hippocampal-Midbrain Encoding of Overlapping Events. Neuron. [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, O. J. (1973). Stimulus meaningfulness, encoding variability, and the spacing effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 99(2), 162–166. [CrossRef]

- Victoria, J.H. Ritvo, Nicholas B. Turk-Browne, & Kenneth A. Norman. (2019). Nonmonotonic Plasticity: How Memory Retrieval Drives Learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

- Wang, Y. N. , Zhou, L. M., & Luo, Y. J. (2008). The Pilot Establishment and Evaluation of Chinese Affective Words System. Chinese Mental Health Journal. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, O. C. , & Watkins, M. J. (1975). Buildup of proactive inhibition as a cue-overload effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. [CrossRef]

- Wimber, M. , Rutschmann, R. M., Greenlee, M. W., & Bäuml, K.-H. T. (2009). Retrieval from Episodic Memory: Neural Mechanisms of Interference Resolution. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Wixted, J. T. , & Mickes, L. (2010). A continuous dual-process model of remember/know judgments. Psychological Review, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassa, M. A. , & Stark, C. E. L. (2011). Pattern separation in the hippocampus. E. L. ( 34(10), 515–525. [CrossRef]

- Yonelinas, A. P. (2002). The nature of recollection and familiarity: A review of 30 years of research. Journal of Memory and Language. [CrossRef]

- Zeithamova, D. , & Preston, A. R. (2010). Flexible Memories: Differential Roles for Medial Temporal Lobe and Prefrontal Cortex in Cross-Episode Binding. The Journal of Neuroscience, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithamova, D. , & Preston, A. R. (2017). Temporal Proximity Promotes Integration of Overlapping Events. R. ( 29(8), 1311–1323. [CrossRef]

| List | Pair Type | Recognition Accuracy (M ± SD) | Correct Reaction Time(ms) | Incorrect Reaction Time(ms) |

| List 1 | Cue-overlap | 0.75 ± 0.15 | 2339.94 ± 363.04 | 2667.74 ± 647.66 |

| Non-overlap | 0.81 ± 0.13 | 2319.70 ± 346.73 | 2631.99 ± 645.72 | |

| List 2 | Cue-overlap | 0.75 ± 0.11 | 2513.32 ± 427.81 | 2867.40 ± 572.10 |

| Non-overlap | 0.74 ± 0.17 | 2273.00 ± 354.35 | 2668.13 ± 639.50 |

| List | Pair Type | Source Judgement Accuracy (M ± SD) | Correct Reaction Time(ms) | Incorrect Reaction Time(ms) |

| List 1 | Cue-overlap | 0.75 ± 0.15 | 561.45± 343.75 | 680.074 ± 406.29 |

| Non-overlap | 0.73 ± 0.14 | 608.35 ± 381.49 | 750.08 ± 442.67 | |

| List 2 | Cue-overlap | 0.70 ± 0.15 | 620.62 ± 394.04 | 662.81 ± 427.18 |

| Non-overlap | 0.69 ± 0.16 | 628.75 ± 379.66 | 667.05 ± 427.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).