Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

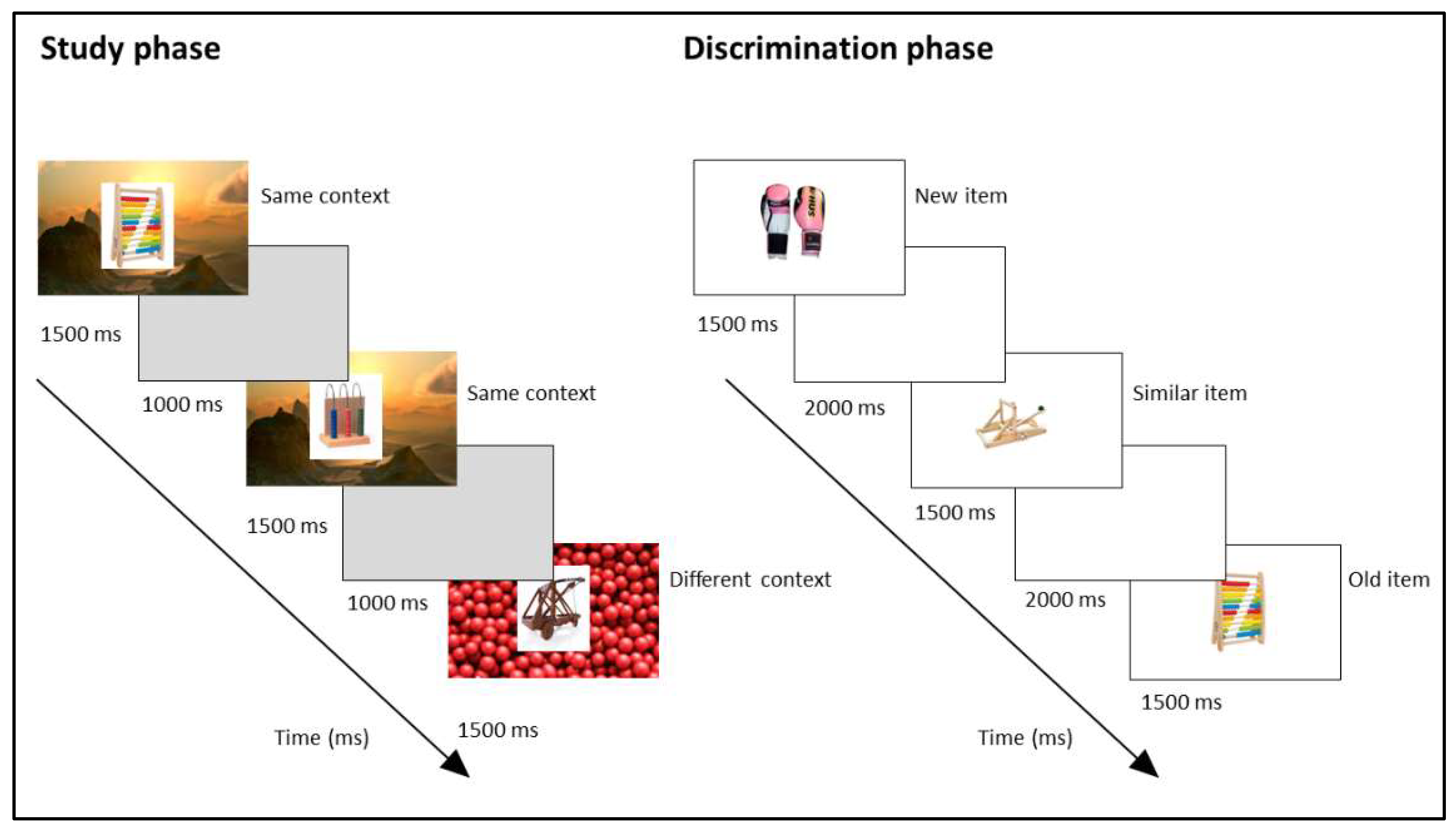

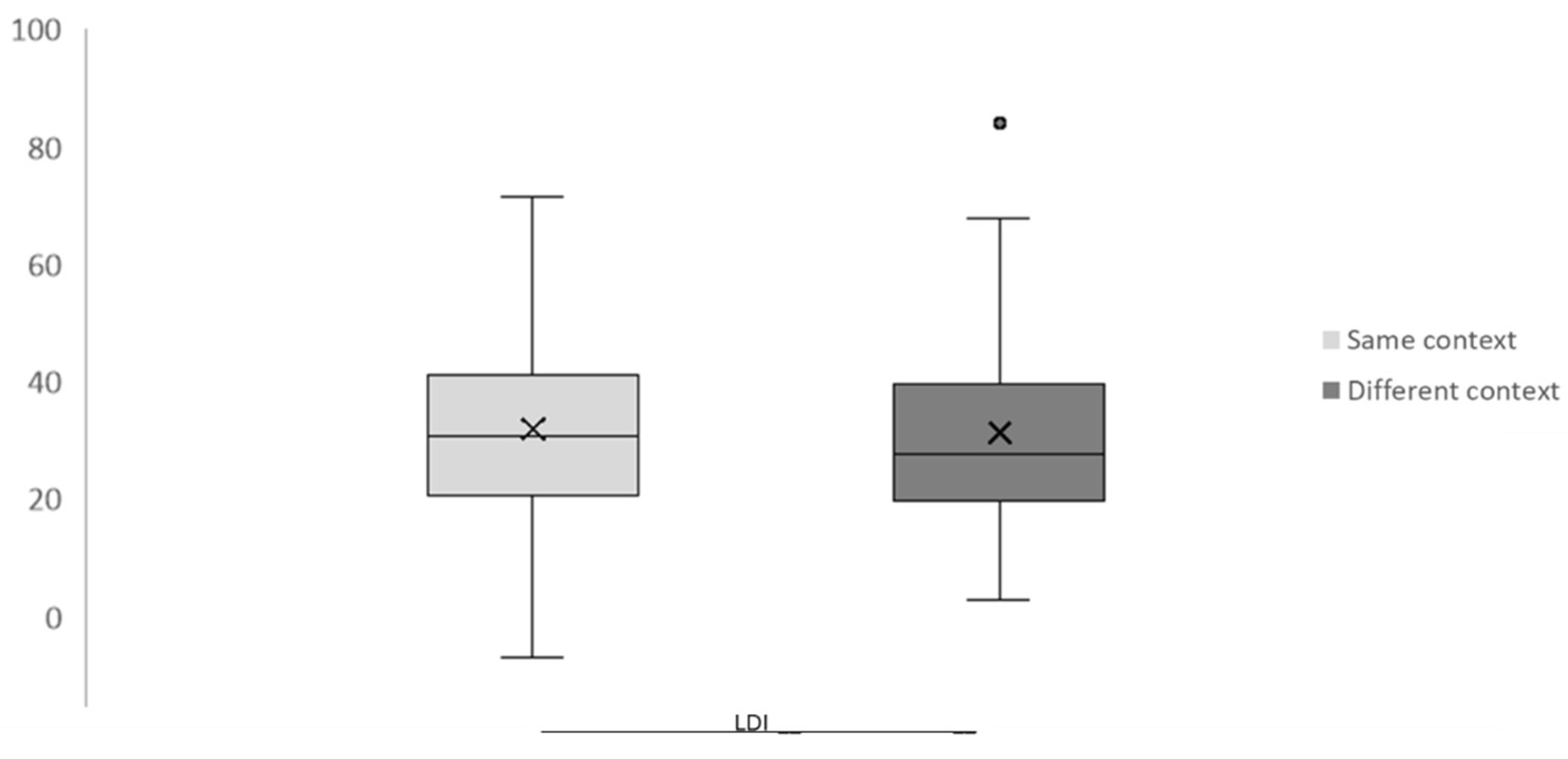

Pattern separation has been studied in relation to both the retrieval and encoding processesis considered a crucial process that allow humans to store and remember allows us to distinguish among the highly similar items. Within this body of research,and overlapping experiences which constitute our episodic memory. Not only different episodes share common features, but it is often the role of case that they share the context in which those similar items are found becomes highly relevant. One hypothesis assertsthey occurred. While there has been a great number of studies investigating pattern separation, and its behavioural counterpart, a process known as mnemonic discrimination, surprisingly, research exploring the influence of context on pattern separation or mnemonic discrimination has been less common. The available evidence showed that similar items with similar context leadled to a failure in pattern separation due to high similarity that triggers overlap between events. In contrast, another hypothesis statesOn the other hand, others have shown that pattern separation can take place even under these conditions, allowing humans to distinguish between events with similar items and contexts, as different hippocampal subfields would play complementary roles in enabling both pattern separation and pattern completion. In the present study, we were interested in testing how stability in context influenced pattern separation. WeDespite the fact that pattern separation is by definition an encoding computation the existing literature has focused on the retrieval phase. Here, we used a subsequent memory paradigm in which we manipulated the similarity of context during encoding. We of visual objects selected from diverse categories. Thus, we manipulated the encoded context of each object category (four items within a category), so that some categories had the same intercategory context (same context) and others had different intercategory contexts (different context).context. This approach allowed us to test not only the items presented, but also include the conditions that entail the greatest demand on pattern separation. After a 20-minute period, participants performed a visual mnemonic discrimination task in which they had to differentiate between old, similar, and new items by providing one of the three options for each item tested. According item. Similarly to the second hypothesis describedprevious studies, we found no interaction between judgments and contexts, and participants were able to discriminate between old and lure items at the behavioural level in both conditions. Moreover, when averaging the ERPs of all the items presented within a category, a significant SME emerged between hits and new misses, but not between hits and old false alarms or similar false alarms. These results suggest that item recognition emerges from the interaction with subsequently encoded information, and not just between item memory strength and retrieval processes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimuli and Procedure

2.3. EEG Acquisition and Processing

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Behavioral Data

2.4.2. EEG Data

2.4.3. Encoding analysis

3. Results

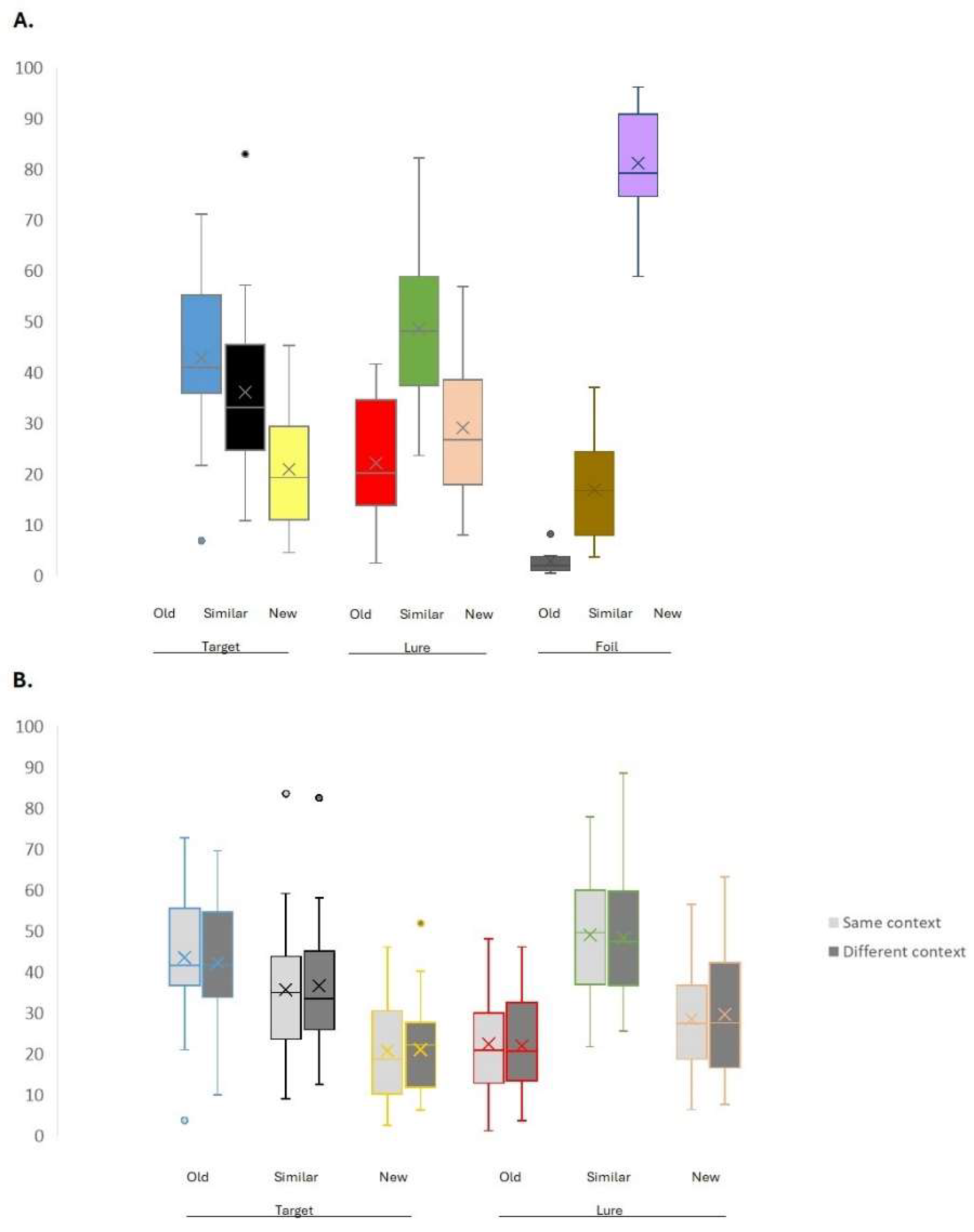

3.1. Behavioral Results

| Table Mean proportion of responses | M | SD | Significant differences* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old response to Target (1) | 42.900 | 2.947 | 2,3,6,7,9 |

| Old response to Lure (2) | 22.209 | 2.245 | 1,3,5,9 |

| Old response to Foil (3) | 1.887 | .473 | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| Similar response to Target (4) | 36.167 | 3.093 | 3,5,6,9 |

| Similar response to Lure (5) | 48.674 | 3.004 | 2,3,4,6,7,8,9 |

| Similar response to Foil (6) | 16.930 | 1.838 | 1,3,4,5,9 |

| New response to Target (7) | 20.933 | 2.258 | 1,3,5,8,9 |

| New response to Lure (8) | 29.117 | 2.692 | 3,5,7,9 |

| New response to Foil (9) | 81.183 | 2.035 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 |

| *See Appendix A for pairwise comparisons |

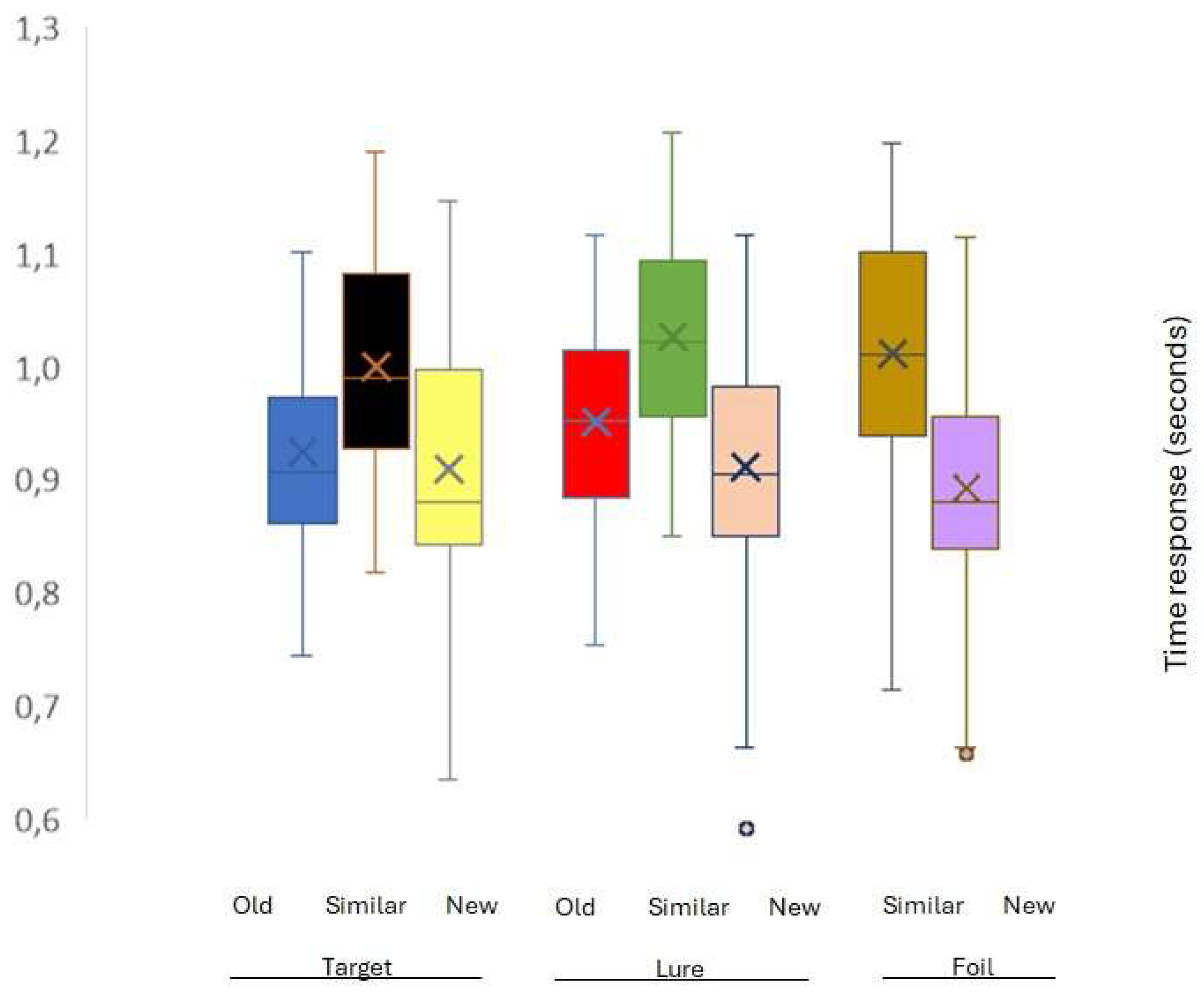

3.2. Reaction time results

| Reaction time responses | M | SD | Significant differences* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old response to Target (1) | 0,962 | 0,083 | 4,5 |

| Old response to Lure (2) | 0,986 | 0,084 | 4 |

| Similar response to Target (3) | 1,030 | 0,087 | 6,4,7,8 |

| Similar response to Lure (4) | 1,054 | 0,079 | 1,3,6,7,8 |

| Similar response to Foil (5) | 1,040 | 0,099 | 1,6,7,8 |

| New response to Target (6) | 0,955 | 0,114 | 3,4,5 |

| New response to Lure (7) | 0,955 | 0,114 | 3,4,5 |

| New response to Foil (8) | 0,933 | 0,100 | 1,6,7,8 |

| *See Appendix B for pairwise comparisons |

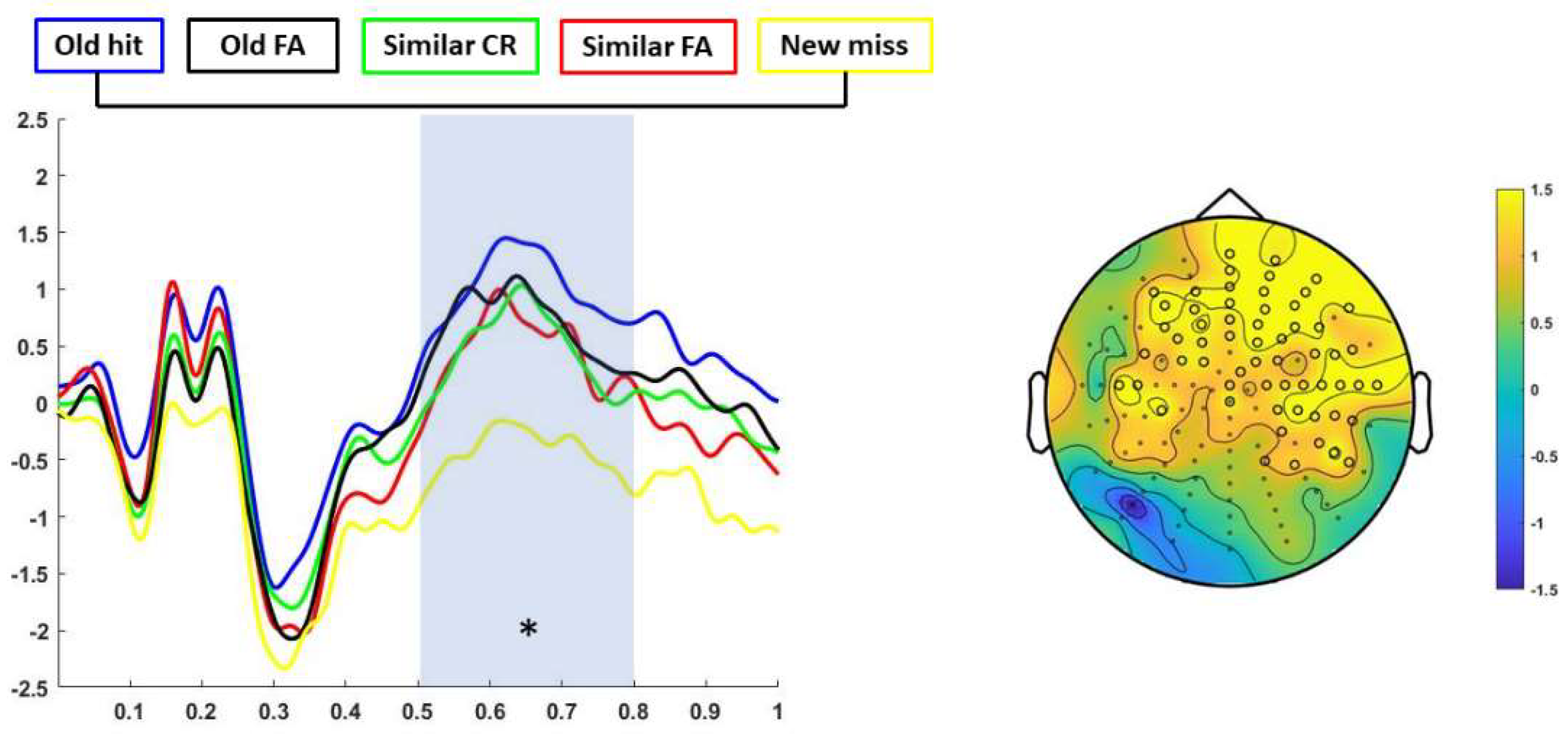

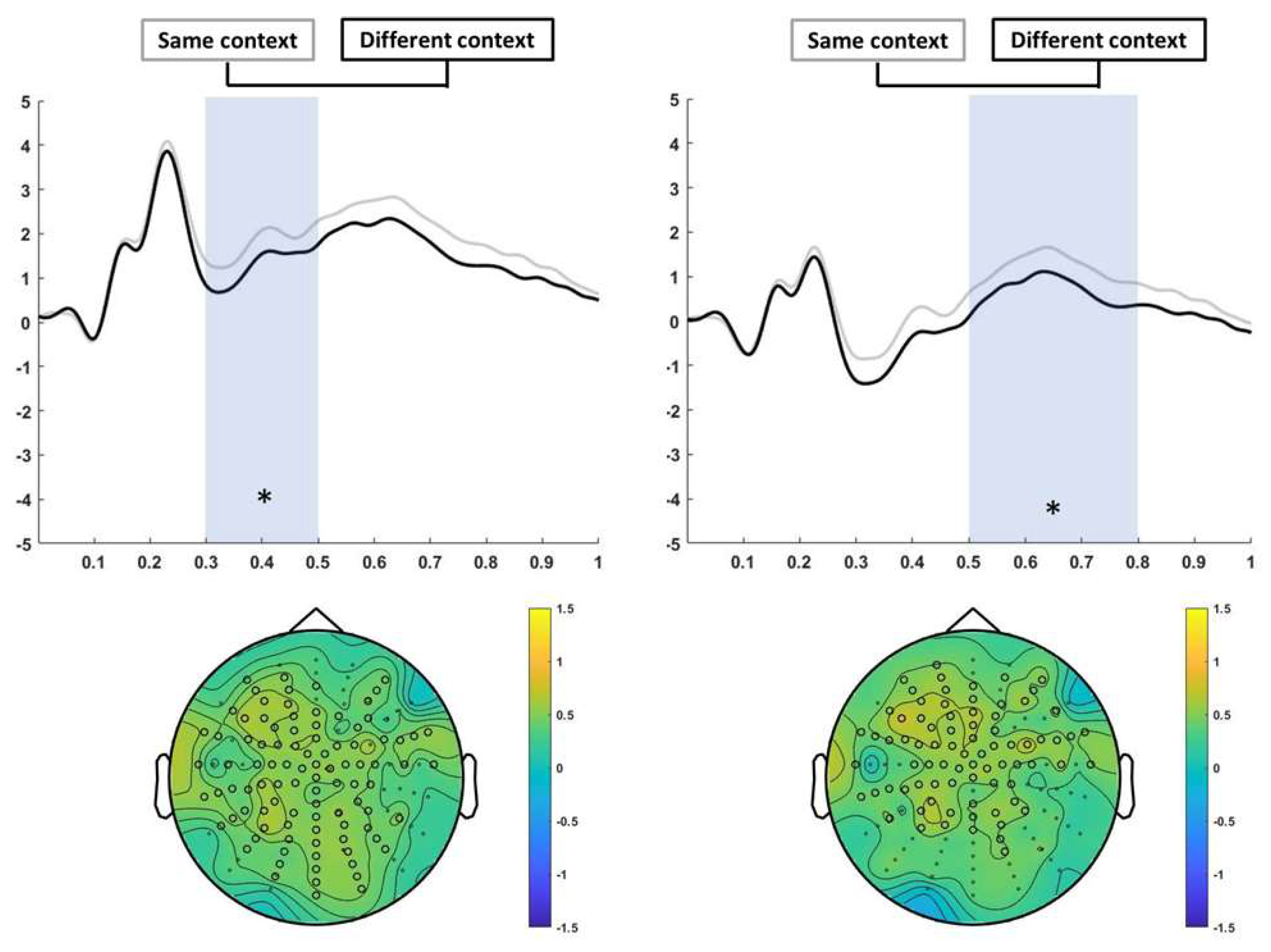

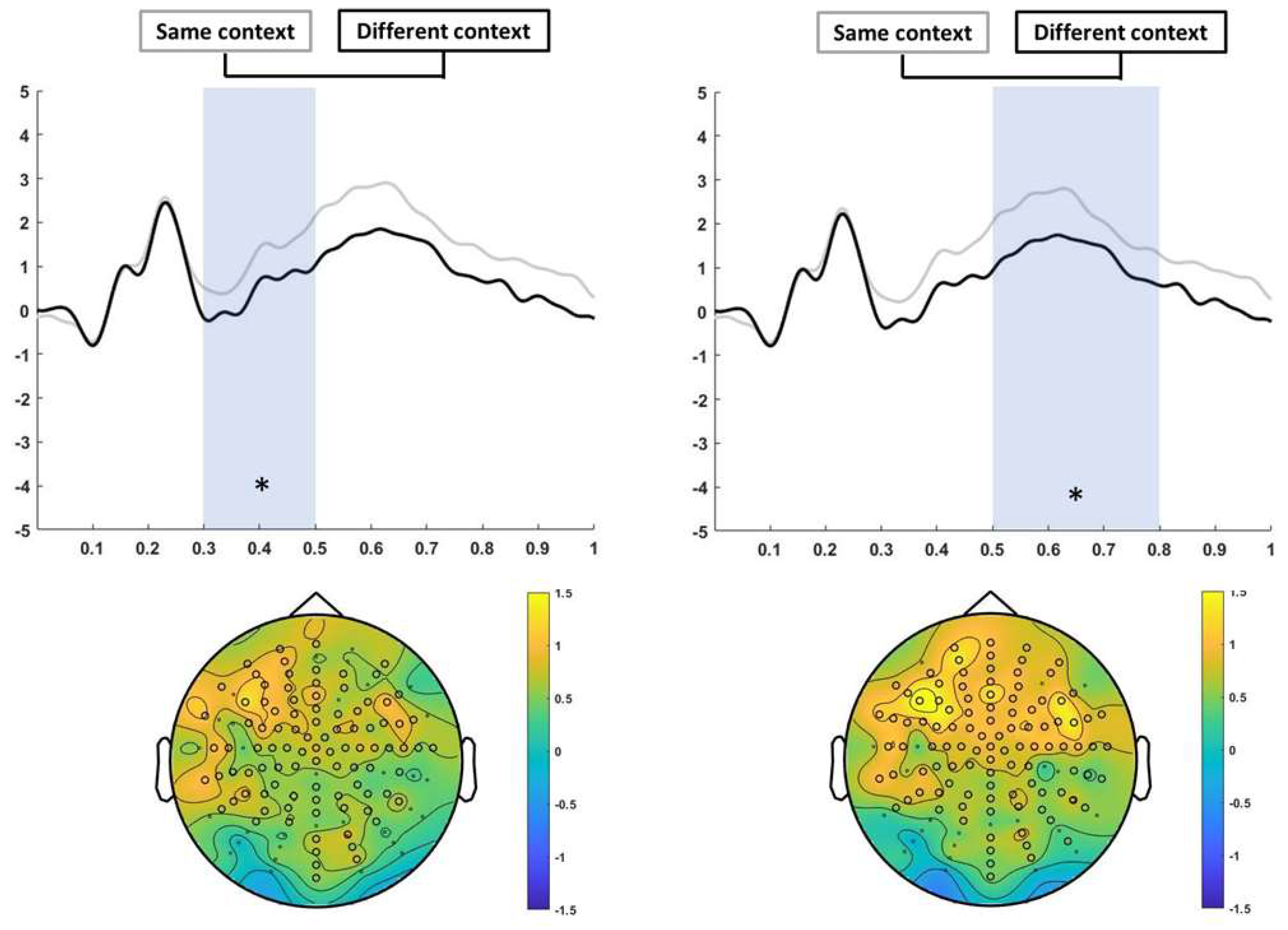

3.3. ERP Results

3.3.1. Encoding

4. Discussion

ERP Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Pairwise comparisons | ||||

| (I)Response | (J)Response | Mean differences (I-J) | Sig.b | |

| Old response to target | New response to target | 21,967* | ,001 | |

| Old response to lure | 20,691* | ,000 | ||

| New response to foil | -38,283* | ,000 | ||

| Similar response to foil | 25,970* | ,000 | ||

| Old response to foil | 41,013* | ,000 | ||

| Similar response to target | Similar response to lure | -12,507* | ,000 | |

| New response to foil | -45,016* | ,000 | ||

| Similar response to foil | 19,237* | ,000 | ||

| Old response to foil | 34,280* | ,000 | ||

| New response to target | Similar response to lure | -27,742* | ,000 | |

| New response to lure | -8,184* | ,000 | ||

| New response to foil | -60,250* | ,000 | ||

| Old response to foil | 19,046* | ,000 | ||

| Similar response to lure | Old response to lure | 26,466* | ,000 | |

| New response to lure | 19,558* | ,036 | ||

| New response to foil | -32,509* | ,000 | ||

| Similar response to foil | 31,745* | ,000 | ||

| Old response to foil | 46,787* | ,000 | ||

| Old response to lure | New response to foil | -58,974* | ,000 | |

| Old response to foil | 20,322* | ,000 | ||

| New response to lure | New response to foil | -52,066* | ,000 | |

| Old response to foil | 27,230* | ,000 | ||

| New response to foil | Similar response to foil | 64,253* | ,000 | |

| Old response to foil | 79,296* | ,000 | ||

| Similar response to foil | Old response to foil | 15,043* | ,000 | |

| b. Adjustment for multiple comparisons: Bonferroni. | ||||

Appendix B

| Pairwise comparisons | ||||

| (I)Response | (J)Response | Mean differences (I-J) | Sig.b | |

| Old response to target | Similar response to lure | -,092* | ,002 | |

| Similar response to foil | -,078* | ,011 | ||

| Similar response to target | New response to target | ,075* | ,003 | |

| Similar response to lure | -,024* | ,004 | ||

| New response to lure | ,075* | ,015 | ||

| New response to foil | ,097* | ,000 | ||

| New response to target | Similar response to lure | -,099* | ,000 | |

| Similar response to foil | -,085* | ,000 | ||

| Similar response to lure | Old response to lure | ,068* | ,041 | |

| New response to lure | ,100* | ,001 | ||

| New response to foil | ,121* | ,000 | ||

| New response to lure | Similar response to foil | -,086* | ,001 | |

| New response to foil | Similar response to foil | -,107* | ,000 | |

| b. Adjustment for multiple comparisons: Bonferroni. | ||||

References

- Tulving, E. Episodic and semantic memory. In Organization of Memory; Tulving, E., Tulving, W., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 382–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kesner, R.P.; Rolls, E.T. A computational theory of hippocampal function, and tests of the theory: New developments. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 48, 92–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachevalier, J.; Nemanic, S.; Alvarado, M.C. The influence of context on recognition memory in monkeys: effects of hippocampal, parahippocampal and perirhinal lesions. Behav. Brain. Res. 2015, 285, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davachi, L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006, 16, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselmo, M.E.; Eichenbaum, H. Hippocampal mechanisms for the context-dependent retrieval of episodes. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 1172–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theves, S.; Grande, X.; Düzel, E.; Doeller, C.F. Pattern completion and the medial temporal lobe memory system. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Memory, Two Volume Pack: Foundations and Applications; Kahana, M.J., Wagner, A.D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 988–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T.; Xue, G.; Love, B.C.; Preston, A.R.; Poldrack, R.A. Global neural pattern similarity as a common basis for categorization and recognition memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 2014, 34, 7472–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- LaRocque, K.F.; Smith, M.E.; Carr, V.A.; Witthoft, N.; Grill-Spector, K.; Wagner, A.D. Global similarity and pattern separation in the human medial temporal lobe predict subsequent memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 2013, 33, 5466–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimsdale-Zucker, H. R. , Ritchey, M. , Ekstrom, A. D., Yonelinas, A. P., Ranganath, C. CA1 and CA3 differentially support spontaneous retrieval of episodic contexts within human hippocampal subfields. Nature Communications, 2018, 9, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rueda, L.; Poch, C.; Campo, P. Forgetting Details in Visual Long-Term Memory: Decay or Interference? Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 2022, 16, 1662–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, C.B.; Stark, C.E. Overcoming interference: an fMRI investigation of pattern separation in the medial temporal lobe. Learn Mem, 2007, 14, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poch, C.; Prieto, A.; Hinojosa, J.A.; Campo, P. The impact of increasing similar interfering experiences on mnemonic discrimination: electrophysiological evidence. Cognitive Neuroscience, 2019, 10, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G. The Neural Representations Underlying Human Episodic Memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2018, 22, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassa, M.A.; Stark, C.E. Pattern separation in the hippocampus. Trends Neurosci, 2011, 34, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, T.; Davachi, L. Extra-hippocampal contributions to pattern separation. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, S.L.; Yassa, M.A. Integrating new findings and examining clinical applications of pattern separation. Nat Neurosci, 2018, 21, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, S.M.; Kirwan, C.B.; Stark CE, L. Mnemonic Similarity Task: A Tool for Assessing Hippocampal Integrity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldi, G.A.; Lange, I.; Gigli, C.; Goossens, L.; Schruers, K.R.; Cosci, F. Validation of the Mnemonic Similarity Task - Context Version. Braz J Psychiatry, 2018, 40, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohm-Hansen, S.; Johansson, M. Mnemonic discrimination of object and context is differentially associated with mental health. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 2020, 173, 107268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, N.; Bukala, B.R.; Kragel, J.E.; Kahana, M.J. Hippocampal activity predicts contextual misattribution of false memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2305292120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollarek, M. Remembering Objects in Contexts: ERP Correlates of a Modified Behavioral Pattern Separation Task. Master Thesis, University of Amsterdam/ Lund University, 2015, 2015; p. 10608753. [Google Scholar]

- Libby, L.A.; Reagh, Z.M.; Bouffard, N.R.; Ragland, J.D.; Ranganath, C. The Hippocampus Generalizes across Memories that Share Item and Context Information. Journal Cognitive Neuroscience 2019, 31, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.M.; Grilli, M.D.; Lawrence, A.V.; Ryan, L. The impact of context on pattern separation for objects among younger and older apolipoprotein ϵ4 carriers and noncarriers. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2023, 29, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racsmány, M.; Bencze, D.; Pajkossy, P.; Szőllősi, Á.; Marián, M. Irrelevant background context decreases mnemonic discrimination and increases false memory. Sci Rep, 2021, 11, 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szőllősi, Á.; Pajkossy, P.; Bencze, D.; Marián, M.; Racsmány, M. Litmus test of rich episodic representations: Context-induced false recognition. Cognition, 2023, 230, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motley, S.E.; Kirwan, C.B. A parametric investigation of pattern separation processes in the medial temporal lobe. J Neurosci, 2012, 32, 13076–13085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Rueda, L.; Poch, C.; Campo, P. Pattern separation during encoding and Subsequent Memory Effect. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 2024, 216, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, L.; Khuu, A.; Bennett, K. Event-related potentials during encoding coincide with subsequent forced-choice mnemonic discrimination. Sci Rep, 2024, 14, 15859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.M.; Nadel, L.; Ryan, L. The effect of scene context on episodic object recognition: parahippocampal cortex mediates memory encoding and retrieval success. Hippocampus, 2007, 17, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, J. The role of memory activation in creating false memories of encoding context. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn, 2010, 36, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, E.A.; Geib, B.R.; Wang, W.C.; Monge, Z.; Davis, S.W.; Cabeza, R. Cortical Overlap and Cortical-Hippocampal Interactions Predict Subsequent True and False Memory. J Neurosci, 2020, 40, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Munoz, A.C.; Alemán-Gómez, Y.; Toledano, R.; Poch, C.; García-Morales, I.; Aledo-Serrano, Á.; Gil-Nagel, A.; Campo, P. Morphometric and microstructural characteristics of hippocampal subfields in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy and their correlates with mnemonic discrimination. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1096873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcom, A.M. Resisting false recognition: An ERP study of lure discrimination. Brain Research 2015, 1624, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.I.; Hodges, C.B.; Muncy, N.M.; Kirwan, C.B. Pattern separation beyond the hippocampus: A high-resolution whole-brain investigation of mnemonic discrimination in healthy adults. Hippocampus, 2021, 31, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pidgeon, L.M.; Morcom, A.M. Cortical pattern separation and item-specific memory encoding. Neuropsychologia, 2016, 85, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, R.F.; Reagh, Z.M.; Chun, A.P.; Murray, E.A.; Yassa, M.A. Pattern Separation and Source Memory Engage Distinct Hippocampal and Neocortical Regions during Retrieval. J Neurosci, 2020, 40, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mecklinger, A.; Kamp, S.M. Observing memory encoding while it unfolds: Functional interpretation and current debates regarding ERP subsequent memory effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2023, 153, 105347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronau, N.; Shachar, M. Contextual consistency facilitates long-term memory of perceptual detail in barely seen images. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform, 2015, 41, 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, W.R.; Dobbelaar, S.; Meeter, M.; Kindt, M.; van Ast, V.A. Episodic memory enhancement versus impairment is determined by contextual similarity across events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.L.; Starns, J.J. Remembering source evidence from associatively related items: explanations from a global matching model. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn, 2006, 32, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melega, G.; Sheldon, S. Conceptual relatedness promotes memory generalization at the cost of detailed recollection. Sci Rep, 2023, 13, 15575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Klaver, P.; Elger, C.E.; Fernandez, G. The interaction of rhinal cortex and hippocampus in human declarative memory formation. Rev Neurosci, 2002, 13, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Klaver, P.; Lehnertz, K.; Grunwald, T.; Schaller, C.; Elger, C.E.; Fernandez, G. Human memory formation is accompanied by rhinal-hippocampal coupling and decoupling. Nat Neurosci, 2001, 4, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, G.; Effern, A.; Grunwald, T.; Pezer, N.; Lehnertz, K.; Dumpelmann, M.; Elger, C.E. Real-time tracking of memory formation in the human rhinal cortex and hippocampus. Science, 1999, 285, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maris, E.; Oostenveld, R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 2007; 164, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouffard, N.R.; Fidalgo, C.; Brunec, I.K.; Lee AC, H.; Barense, M.D. Older adults can use memory for distinctive objects, but not distinctive scenes, to rescue associative memory deficits. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, T.F.; Konkle, T.; Alvarez, G.A.; Oliva, A. Real-world objects are not represented as bound units: independent forgetting of different object details from visual memory. J Exp Psychol Gen, 2013, 142, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragel, J.E.; Ezzyat, Y.; Lega, B.C.; Sperling, M.R.; Worrell, G.A.; Gross, R.E.; Jobst, B.C.; Sheth, S.A.; Zaghloul, K.A.; Stein, J.M.; Kahana, M.J. Distinct cortical systems reinstate the content and context of episodic memories. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.L.; James, J.R.; Kirwan, C.B. An event-related potential investigation of pattern separation and pattern completion processes. Cognitive Neuroscience 2016, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I.C.; Van Buuren, M.; Bovy, L.; Fernández, G. Parallel Engagement of Regions Associated with Encoding and Later Retrieval Forms Durable Memories. Journal of Neuroscience, 2016, 36, 7985–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szőllősi, Á.; Bencze, D.; Racsmány, M. Behavioural pattern separation is strongly associated with familiarity-based decisions. Memory, 2020, 28, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schacter, D.L.; Guerin, S.A.; St Jacques, P.L. Memory distortion: an adaptive perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2011, 15, 467–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.A.; O’Reilly, R.C. Modeling hippocampal and neocortical contributions to recognition memory: a complementary-learning-systems approach. Psychological Review, 2003, 110, 611–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).