Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

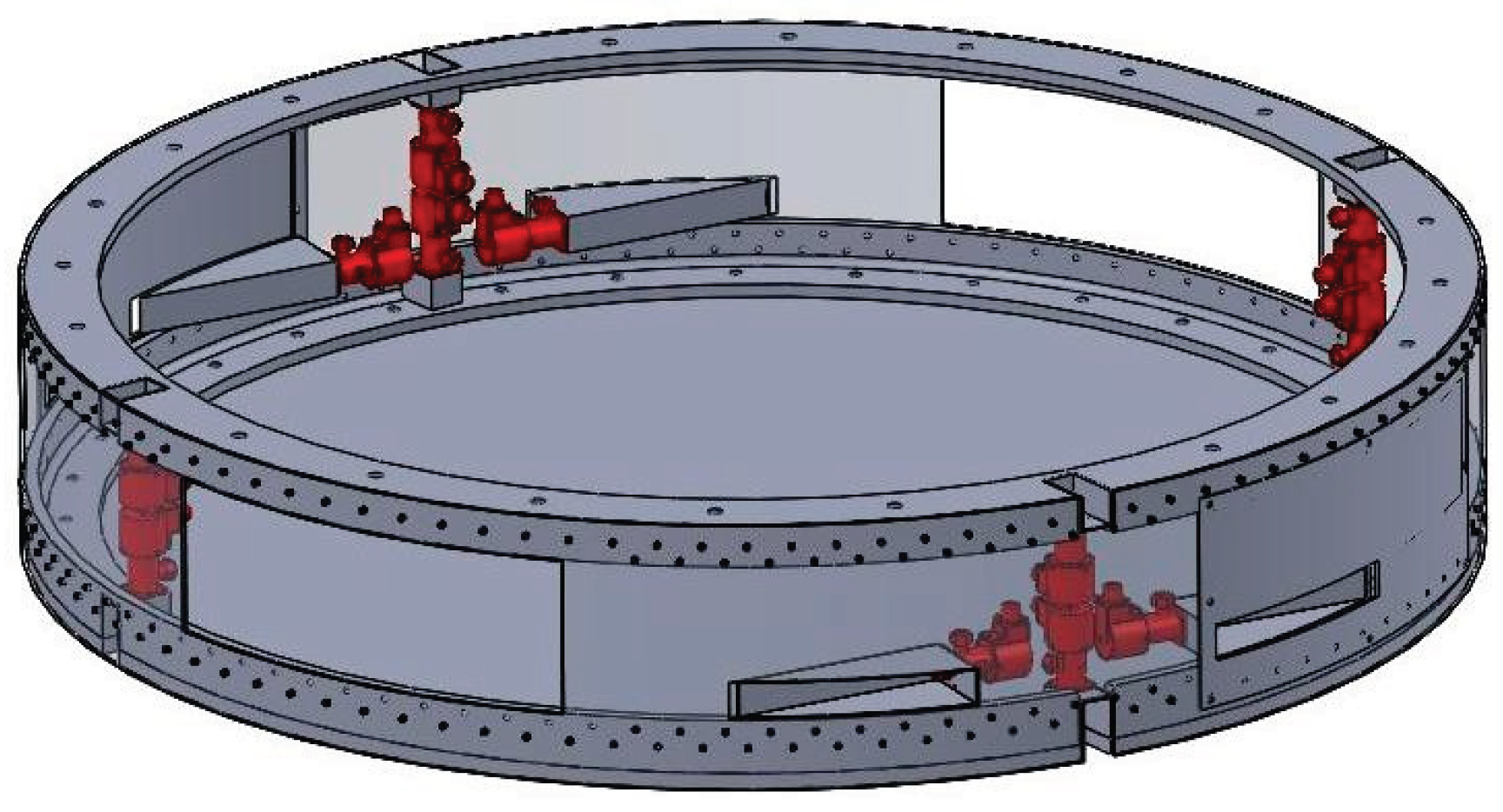

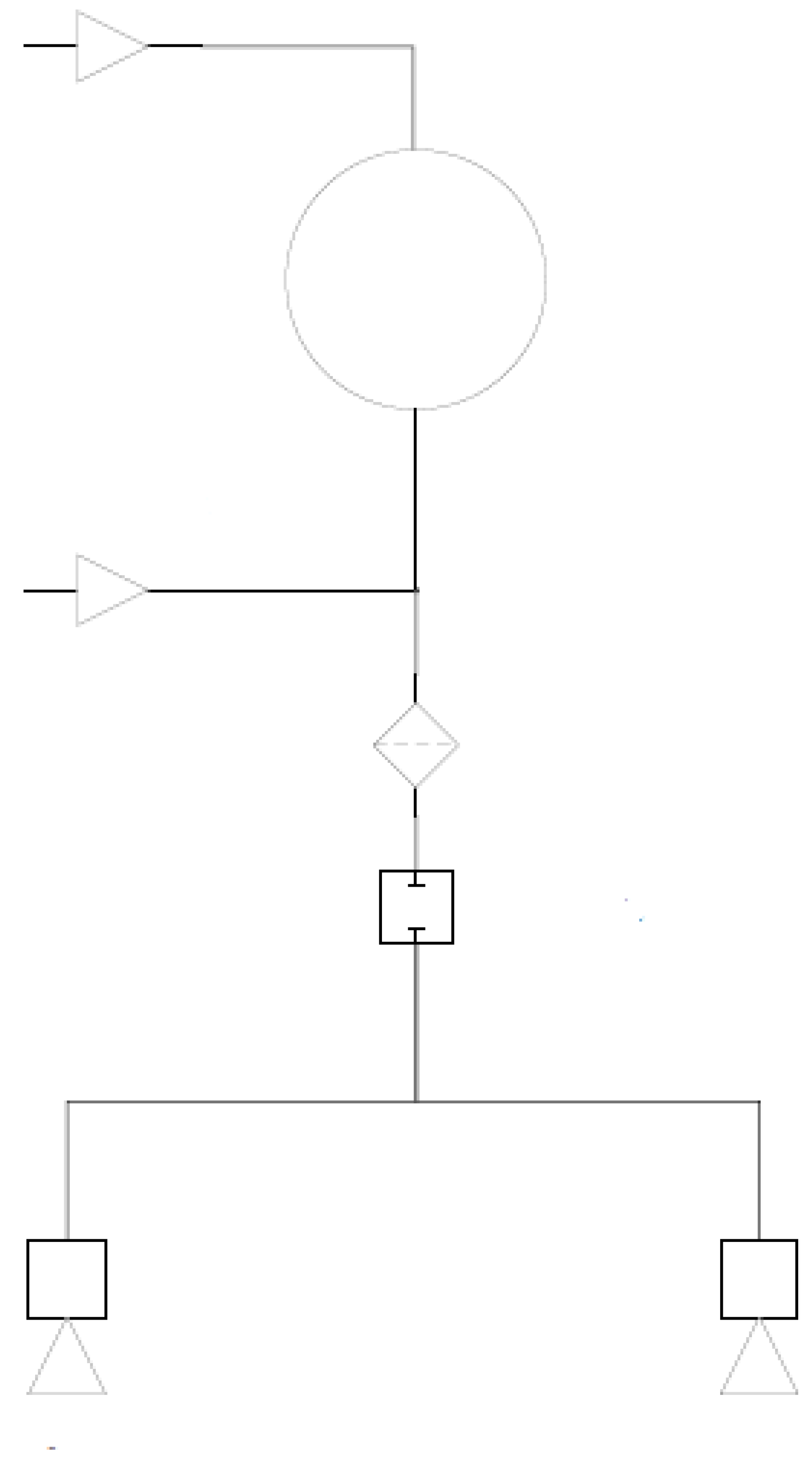

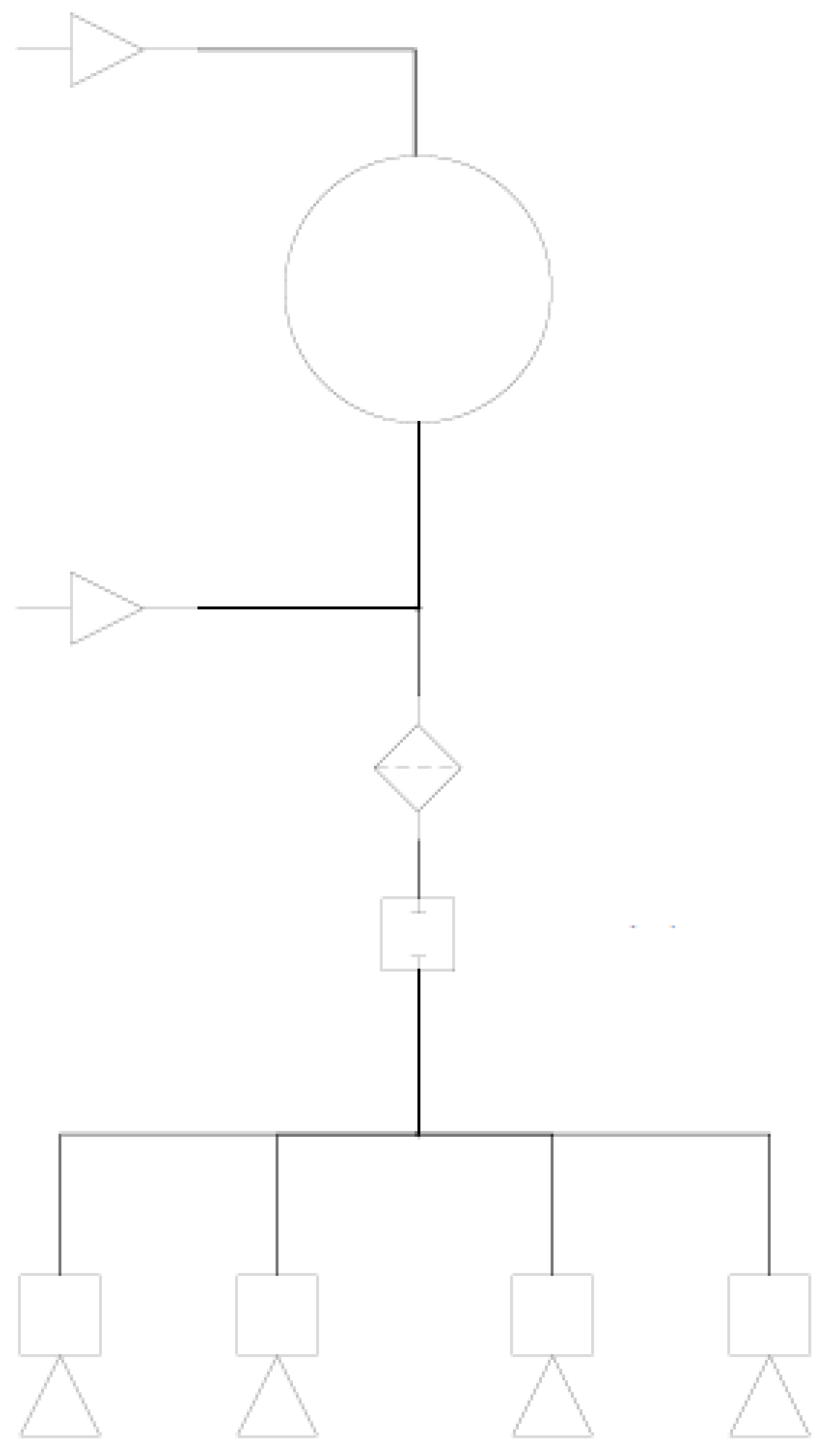

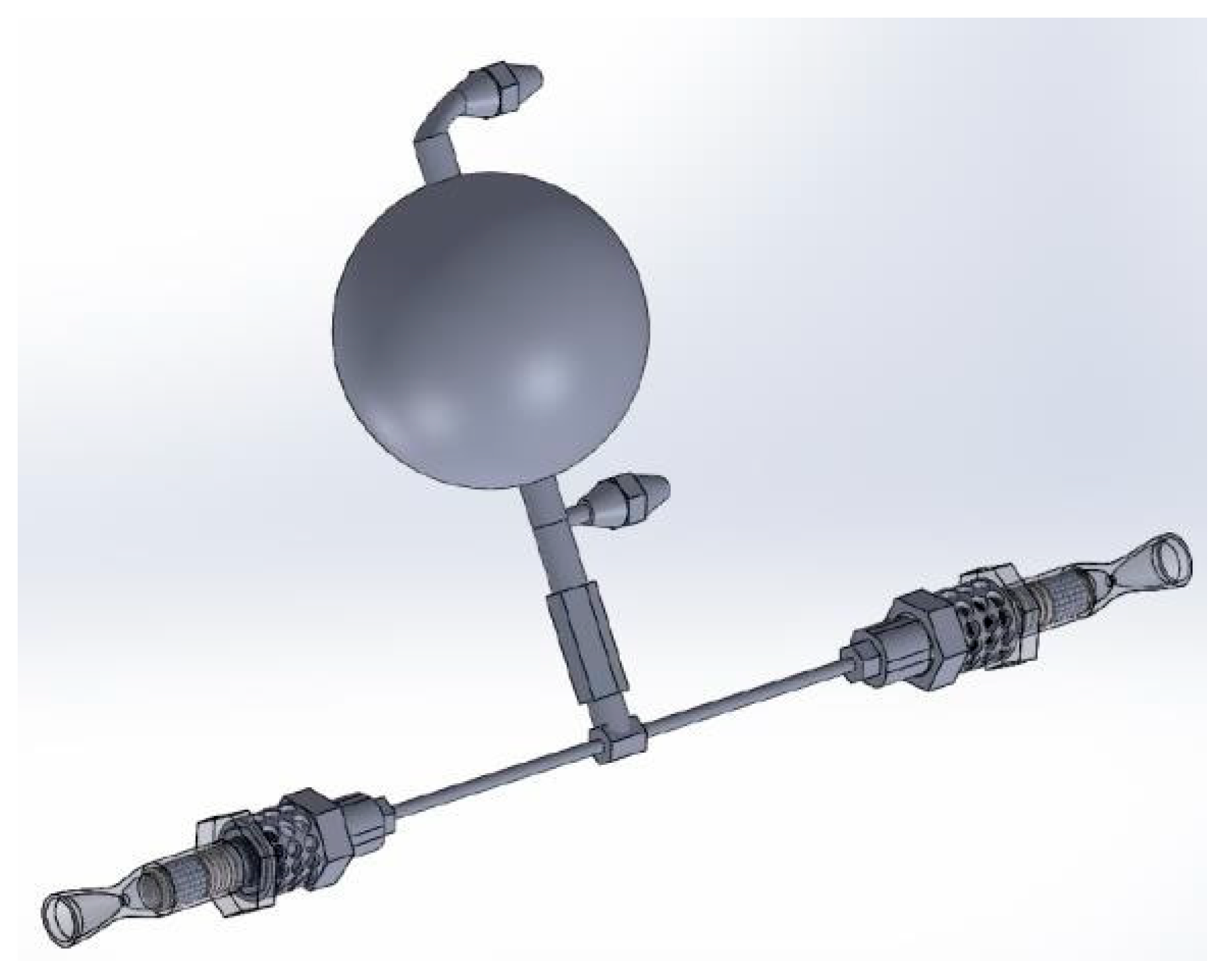

2. Thruster Cluster Design

- Propellant Gas Charge/Discharge Valve: Used for injecting the pressurizing agent gas or for purging the tank during hydrazine charging.

- Hydrazine Propellant Charge/Discharge Valve: Used for injecting propellant into the tank or discharging unused excess propellant.

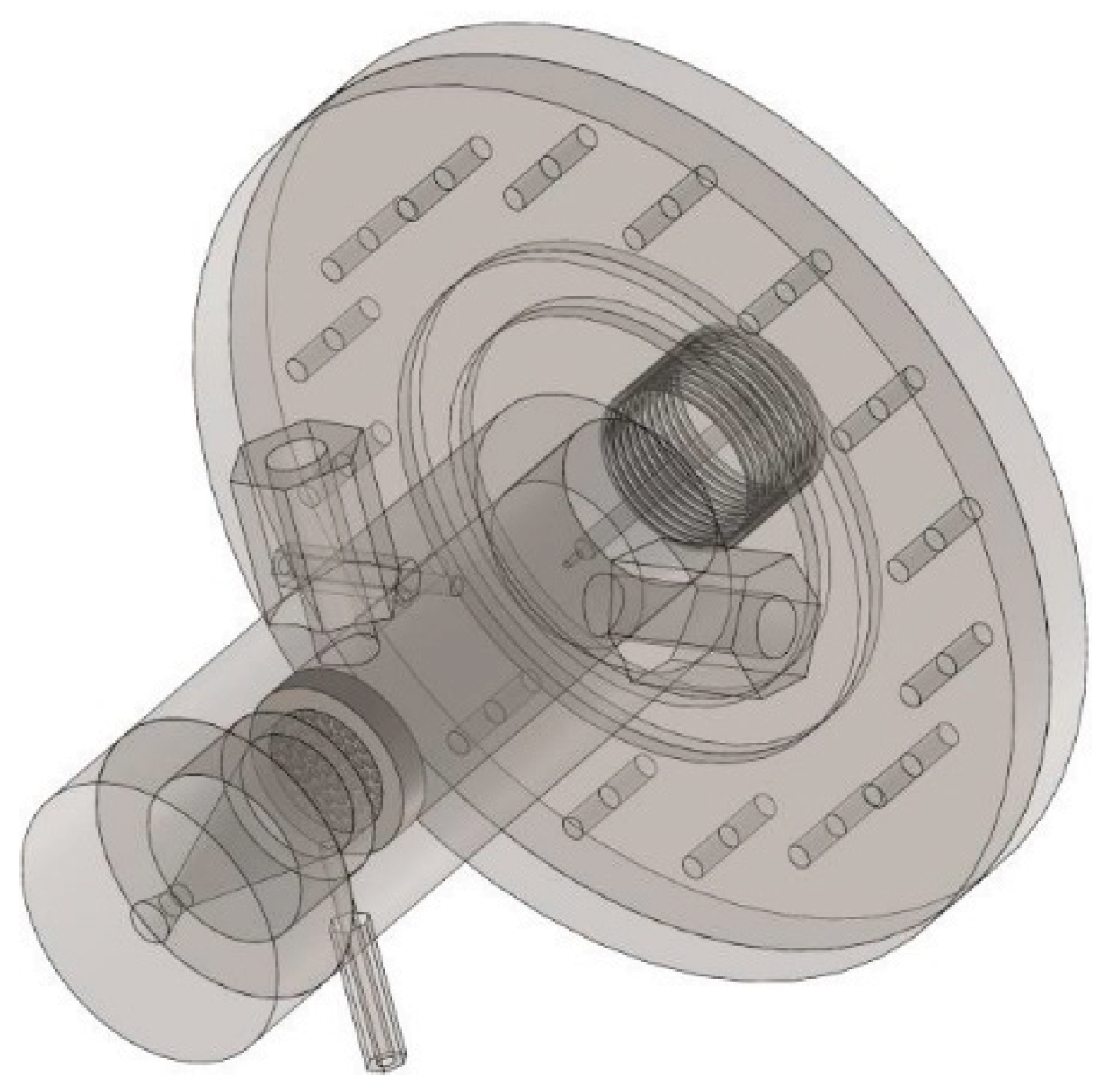

- Tank and PMD (Propellant Management Device): This equipment is essential for safely storing propellant, providing the necessary pressure, and ensuring continuous propellant injection to the actuator's injector head in zero-gravity conditions.

- Filter: Necessary to remove propellant contaminants to prevent clogging of the injector orifice. The filter's flow cross-section is selected to be 40 microns based on the injector orifice size, and its material is compatible with hydrazine.

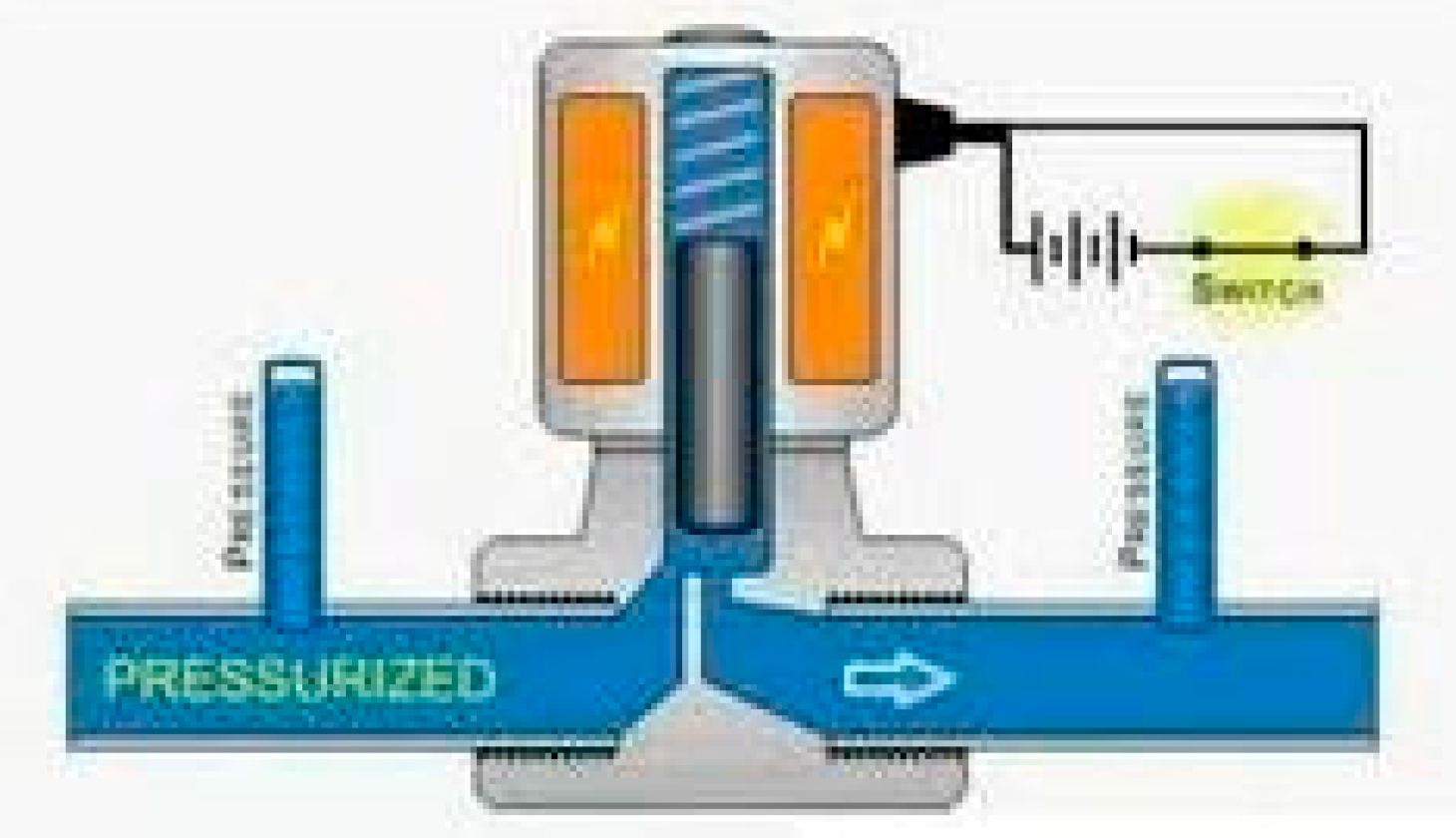

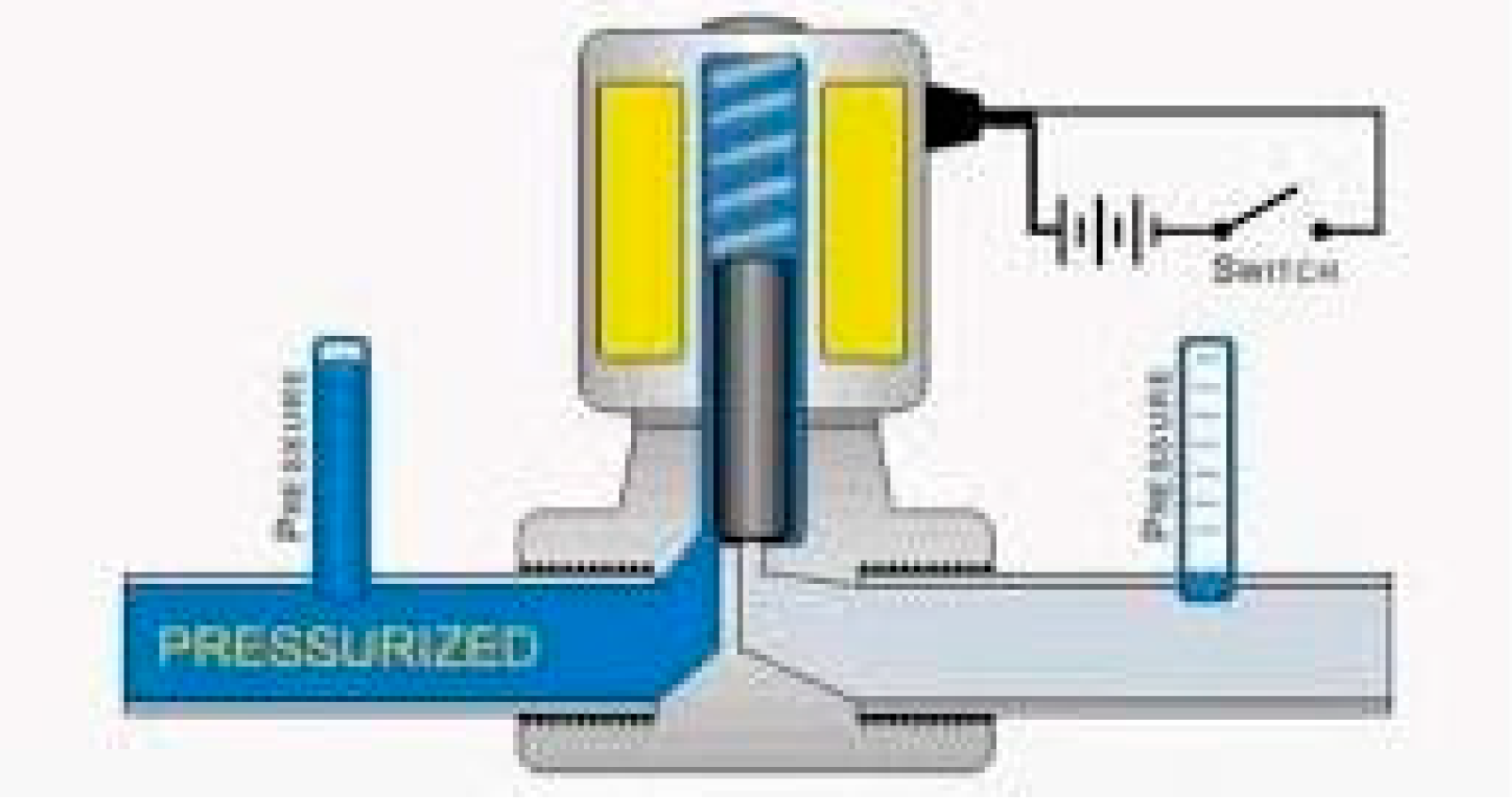

- Flow Control Valve: Used to open and close the flow path to the actuator for thrust control.

- Thruster: Equipment that converts the chemical energy of the propellant into thermal and kinetic energy by spraying hydrazine onto a catalyst.

3. Flow Control Valve

- Flow Type: Divided into two categories: constant flow and variable (adjustable) flow.

- Valve Mechanism Type: Can be poppet or piston, diaphragm, ball, or other types.

- Actuation Type: Can be solenoid, pneumatic, or other types.

- Valves with/without Pressure Compensator System: These are capable of automatically maintaining a constant fluid flow rate despite pressure fluctuations.

- Normally Closed or Normally Open: This refers to the valve's status prior to actuation.

4. Conclusions

References

- Ley, H.; Wittmann, K.; Hallmann, W. Handbook of space technology; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saboohi, Z.; Moradi, A.; Hosseini, S.E.; Karimi, N. Experimental investigation of atmospheric boundary layer using unmanned aerial system equipped with novel measurement system. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2025 1371 2025, 137, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.W. Thruster attitude control system design and performance for Tactical Satellite 4 maneuvers. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2014, 37, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, S.; Ommi, F.; Saboohi, Z.; Hosseini, S.E. Hybrid Multi-Objective Optimization of Gas Turbine Combustor to Reduce Non-Volatile Particulate Matter and Gaseous Emissions. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabohi, Z.; Hosseini, S.E. Advancements in Biogas Production: Process Optimization and Innovative Plant Operations. Clean Energy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Jafaripanah, S.; Saboohi, Z. CFD simulation and aerodynamic optimization of two-stage axial high-pressure turbine blades. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, S.; Hosseini, S.E. A review on the oxygenated fuels on engine performance parameters and emissions of spark ignition engines. OSF 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, D.; Poureyvaz Borazjani, D.; Hosseini, S.E.; Davari, S. Impact of Exhaust Manifold Design on Internal Combustion Engine Performance. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, B.; Kong, X.; Chen, H. Experimental study on the outlet flow field and cooling performance of vane-shaped pre-swirl nozzles in gas turbine engines. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 44, 102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofre-Reche, J.A.; Pulpytel, J.; Fakhouri, H.; Arefi-Khonsari, F.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Surface Treatment of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) with Atmospheric Pressure Rotating Plasma Jet. Modeling and Optimization of the Surface Treatment Conditions. Plasma Process. Polym. 2016, 13, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Deyranlou, A.; Talebizadehsardari, P.; Mohammed, H.I.; Keshmiri, A. Developing a numerical framework to study the cavitation and non-cavitation behaviour of a centrifugal pump inducer. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2024, 16, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Bahonar, H.; Beige, A.A. Experimental investigation of flame state transition in a gas turbine model combustor by analyzing noise characteristics. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, S.; Ommi, F.; Saboohi, Z. Investigating the Effects of Adding Butene, Homopolymer to Gasoline on Engine Performance Parameters and Pollutant Emissions : Empirical Study and Process Optimization. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, F.F.; Mehdi, Z. Design and Analysis of Gimbal Thruster Configurations for 3-Axis Satellite Attitude Control. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 112, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Keshmiri, A. Experimental and numerical investigation of different geometrical parameters in a centrifugal blood pump. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 38, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, S.; Ommi, F.; Saboohi, Z.; Safar, M. Experimental study of the effect of a non-oxygenated additive on spark-ignition engine performance and pollutant emissions. Int. J. Eng. Trans. A Basics 2021, 34, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysanek, F.; Hartmann, J.W.; Applied, A.; Corporation, S.; Ave, P.; Leandro, S.; Rysanek, F. MicroVacuum Arc Thruster Design for a CubeSat Class Satellite. In Proceedings of the Small Satellite Conference; 2002; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo, R.; Manna, M. Effects of the duct thrust on the performance of ducted wind turbines. Energy 2016, 99, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeefard, M.H.; Hosseini, S.E.; Zare, J. Numerical simulation and multi-objective optimization of the centrifugal pump inducer. Modares Mech. Eng. 2018, 17, 205–216. Available online: http://mme.modares.ac.ir/article-15-15078-en.html.

- Hosseini, S.E.; Saboohi, Z. Ducted wind turbines: A review and assessment of different design models. Wind Eng. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaval, M.N.; Jonsdottir, H.R.; Leni, Z.; Keller, A.; Brem, B.T.; Siegerist, F.; Schönenberger, D.; Durdina, L.; Elser, M.; Salathe, M.; et al. Responses of reconstituted human bronchial epithelia from normal and health-compromised donors to non-volatile particulate matter emissions from an aircraft turbofan engine. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Salehi, F. Analyzing overlap ratio effect on performance of a modified Savonius wind turbine. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 125131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwosi, C.O.; Ozoegwu, C.G.; Nwagu, T.N.; Nwobodo, T.N.; Eke, I.E.; Igbokwe, V.C.; Ugwuoji, E.T.; Ugwuodo, C.J. Cattle manure as a sustainable bioenergy source: Prospects and environmental impacts of its utilization as a major feedstock in Nigeria. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2022, 19, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Gyawali, R.; Lens, P.N.L.; Lohani, S.P. Technologies for removal of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from biogas. Emerg. Technol. Biol. Syst. Biogas Upgrad. 2021, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Karimi, O.; AsemanBakhsh, M.A. Experimental investigation and multi-objective optimization of savonius wind turbine based on modified non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm-II. Wind Eng. 2024, 48, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, S.; Ommi, F.; Saboohi, Z.; Hosseini, S.E. Conceptual Design of a Conventional Aero Gas Turbine Combustor for Soot and Gaseous Emissions Reduction. J. Engine Res. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaeefard, M.H.; Hosseini, S.E.; Zare, J. CFD simulation and Pareto-based multi-objective shape optimization of the centrifugal pump inducer applying GMDH neural network, modified NSGA-II, and TOPSIS. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2019, 60, 1509–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Yang, S. Surface modification of PDMS by atmospheric-pressure plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition and analysis of long-lasting surface hydrophilicity. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2012, 162, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, J.; Hosseini, S.E.; Rastan, M.R. Airborne dust-induced performance degradation in NREL phase VI wind turbine: a numerical study. Int. J. Green Energy 2024, 21, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, S.; Ommi, F.; saboohi, Z. Experimental study of the effects of adding methylated homopolymer to gasoline on the engine performance and pollutant emissions. J. Solid Fluid Mech. 2021, 11, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Quantity | Unit |

| Hydrazine Propellant Mass | 1.98 | kg |

| Hydrazine Propellant Volume | 1.94 | lit |

| Nitrogen Pressurant Gas Volume | 0.63 | lit |

| Gas to Liquid Volume Ratio in Tank | 0.33 | - |

| Tank Radius | 8.5 | cm |

| Tank Volume | 2.58 | lit |

| Dry Tank Mass | 0.72 | kg |

| Tank Operating Pressure | 21.5 | bar |

| Maximum Tank Operating Pressure | 25 | bar |

| Tank Burst Pressure | 40 | bar |

| Parameter | Quantity | Unit |

| Hydrazine Propellant Mass | 3.96 | kg |

| Hydrazine Propellant Volume | 3.88 | lit |

| Nitrogen Pressurant Gas Volume | 0.97 | lit |

| Gas to Liquid Volume Ratio in Tank | 0.25 | - |

| Tank Radius | 10.5 | cm |

| Tank Volume | 4.85 | lit |

| Dry Tank Mass | 1.1 | kg |

| Maximum Tank Operating Pressure | 25 | bar |

| Tank Burst Pressure | 40 | bar |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).