Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Propulsion Systems for HAPS

2.1. Combustion Propulsion

2.2. Electric Propulsion

2.3. Hybrid Propulsion

2.4. Future Propulsion Concepts

3. Propellers Theory for HAPS

3.1. Development on Theoretical Background

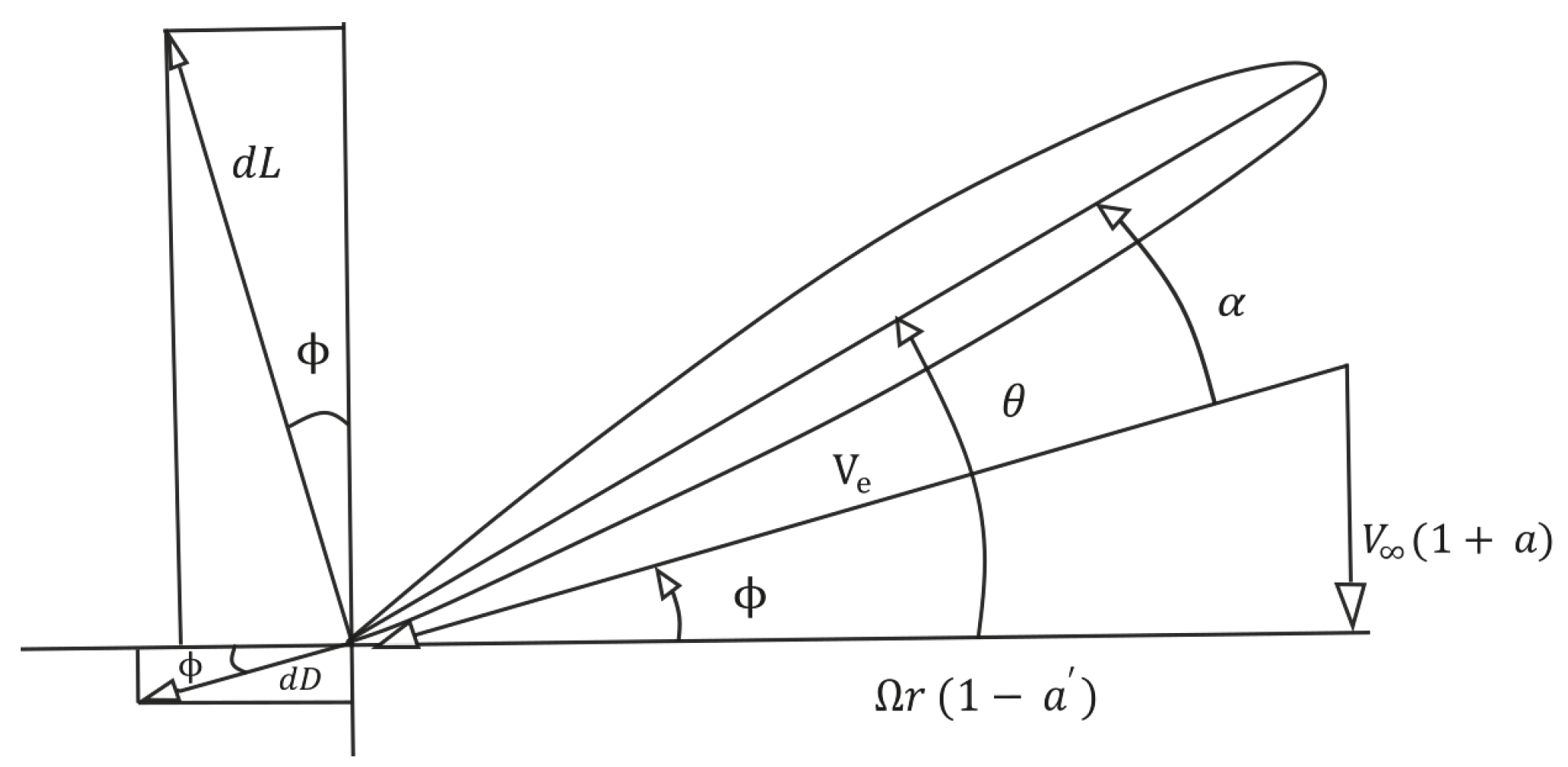

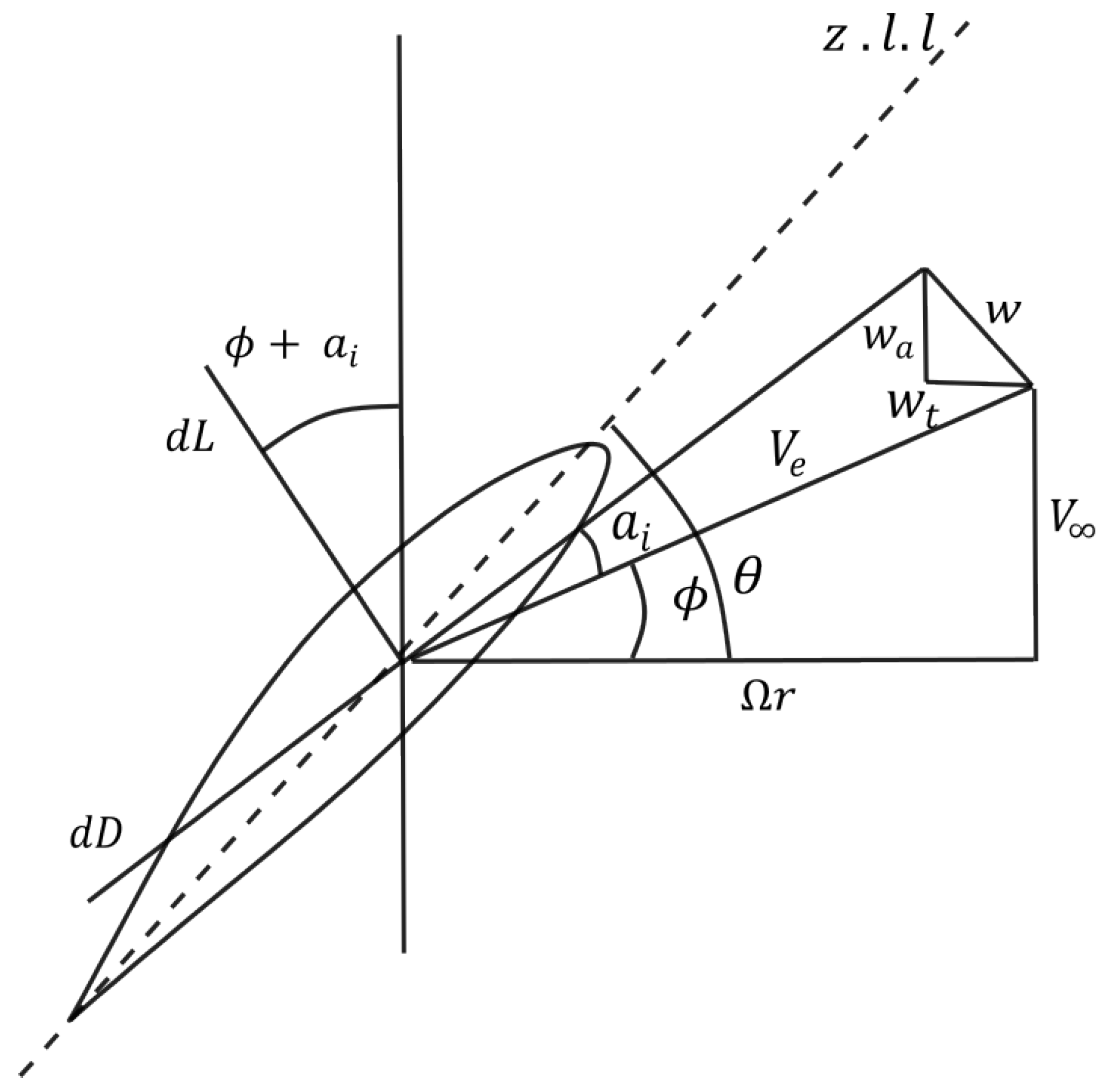

3.2. Blade Element Momentum Theory

3.3. Solidity

3.4. Thrust and Power Coefficient

3.5. Vortex Theory

4. Propellers Design for HAPS operation

4.1. Design Issues for High Altitude Propellers

4.2. Recent Development on Propeller Design Methodology

5. Experimental Methods for Evaluating HAPS Propeller Performance

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Blade Element Momentum Theory | |

| Blade Element Theory | |

| Italian Aerospace Research Centre | |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics | |

| High Altitude Airship | |

| High Altitude Long Endurance | |

| High Altitude Pseudo Satellite | |

| Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems | |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

References

- Botti, J. Airbus Group: A Story of Continuous Innovation. Aeronaut. J. 2016, 120, 3–12.

- BAE Systems. PHASA-35 Completes First Successful Stratospheric Flight. 2024. Available online: https://www.baesystems.com/en/article/phasa-35-completes-first-successful-stratospheric-flight (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Mumford, R. Stratobus Project Takes Off. Microw. J. 2016, 59, 6.

- Sceye. High Altitude Platform Systems (HAPS). 2024. Available online: https://www.sceye.com/platform (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Baraniello, V.R.; Persechino, G.; Borsa, R. Tools for the Conceptual Design of a Stratospheric Hybrid Platform. SAE Tech. Pap. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Baraniello, V.R.; Persechino, G.; Angelino, C.V.; et al. The Application of High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellites for a Rapid Disaster Response. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gallington, R.; Schoenung, S.; Papadales, B. Possibilities for Very High-Altitude Subsonic Propulsion. In Proceedings of the 30th Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA, 27–29 June 1994.

- Hendrick, P.; Hallet, L.; Verstraete, D. Comparison of Propulsion Technologies for a HALE Airship. In Proceedings of the 7th AIAA ATIO Conference, 2nd CEIAT International Conference on Innovation and Integration in Aerospace Sciences, Belfast, Northern Ireland, 18–20 September 2007.

- Young, M. An Overview of Advanced Concepts for Near Space Systems. In Proceedings of the 45th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Denver, Colorado, USA, 2–5 August 2009. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, A.; Jiya, I.N.; Martinson, C.; Bessarabov, D.; Gouws, R. A Comprehensive Review of Energy Sources for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Their Shortfalls and Opportunities for Improvements. Heliyon 2020, 6, 11.

- Deloitte. Research Study on High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellites. 2022. Available online: https://www.frontex.europa.eu/assets/EUresearchprojects/News/2023/Frontex_HAPS_KoM.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Boaretto, N.; Garbayo, I.; Valiyaveettil-SobhanRaj, S.; et al. Lithium Solid-State Batteries: State-of-the-Art and Challenges for Materials, Interfaces and Processing. J. Power Sources 2021, 502, 229919. [CrossRef]

- Amprius. Amprius Technologies Ships First Commercially Available 450 WH/KG, 1150 Wh/L Batteries. 2022. Available online: https://amprius.com/amprius-technologies-ships-first-commercially-available-450-wh-kg-1150-wh-l-batteries (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- MicroLink Devices Recognized as Airbus Key Supplier. 2019. Available online: https://mldevices.com/test-news/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Hydrogen-powered aviation. A fact-based study of hydrogen technology, economics, and climate impact by 2050. Available online: https://www.clean-hydrogen.europa.eu/document/download/754333a6-070d-4954-bda6-9ca4a3637a5d_en?filename=20200720_Hydrogen%20Powered%20Aviation%20report_FINAL%20web.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Alves, P.; Silvestre, M.; Gamboa, P. Aircraft Propellers—Is There a Future? Energies 2020, 13, 4157. [CrossRef]

- Nixon, D. The Boeing Condor. SAE Tech. Pap. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Halawi, S. Zephyr’s Next Chapter, Airbus Trade Media Briefing 2022, Madrid, Spain. 2022. Available online: https://mediaassets.airbus.com/pm_38_602_602492-ie1gtafyip.pdf?dl=true (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Boeing. Boeing Phantom Eye Completes 1st Autonomous Flight. 2012. Available online: https://boeing.mediaroom.com/2012-06-04-Boeing-Phantom-Eye-Completes-1st-Autonomous-Flight (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- NASA. Perseus B. 1999. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/120313main_FS-059-DFRC.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- NASA. Pathfinder: Leading the Way in Solar Flight. 2022. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/120291main_FS-034-DFRC.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- U.S. Air Force. RQ-4 Global Hawk. 2014. Available online: https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/104516/rq-4-global-hawk/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Taylor, M.J.H. World Aircraft & Systems Directory; Brassey’s: London, UK, 1999.

- Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Class C-1e (Landplanes: Take-Off Weight 3000 to 6000 kg) – Altitude. 1988. Available online: https://www.fai.org/record/1388 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Lobner, P. Sceye Stratospheric Airship. 2022. Available online: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sceye_stratospheric-airship-converted.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Colozza, A. High Altitude Propeller Design and Analysis Overview. NASA-CR-1998-208520, 1998.

- Gonzalo, J.; López, D.; Domínguez, D.; et al. On the Capabilities and Limitations of High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellites. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 98, 37–56. [CrossRef]

- NASA. Helios Prototype: The Forerunner of 21st Century Solar-Powered Atmospheric Satellites. 2022. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/120318main_FS-068-DFRC.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Hwang, S.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, C.W.; et al. Aerodynamic Design of the Solar-Powered High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2016, 17, 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerberg, M. The Technology Behind Aquila. 21 July 2016. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/notes/mark-zuckerberg/the-technology-behind-aquila/10153916136506634/ (accessed on 29 November 2017).

- Zephyr. The High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellite. 2017. Available online: http://defence.airbus.com/portfolio/uav/zephyr/ (accessed on 29 November 2017).

- Wong, K. Solar-Electric Cai Hong UAV Conducts Stratospheric Flight. Int. Def. Rev. 2017, June.

- Smith, I.S.; Lee, M. The HiSentinel Airship. In Proceedings of the 7th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration and Operations Conference (ATIO), Belfast, Northern Ireland, 18–20 September 2007.

- Maekawa, S.; Nakadate, M.; Takegaki, A. Structures of the Low Altitude Stationary Flight Test Vehicle. J. Aircr. 2007, 44, 662–666. [CrossRef]

- United States Government Accountability Office. Future Aerostat and Airship Investment Decisions Drive Oversight and Coordination Needs; GAO-13–81; U.S. Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Winslow, J.; Otsuka, H.; Govindarajan, B.; et al. Basic Understanding of Airfoil Characteristics at Low Reynolds Numbers (104–105). J. Aircr. 2018, 55, 1050–1061. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhong, B.; Liu, P. Optimization Design Study of Low-Reynolds-Number High-Lift Airfoils for the High-Efficiency Propeller of Low-Dynamic Vehicles in Stratosphere. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2010, 53, 2792–2807. [CrossRef]

- Maulana, F.A.; Amalia, E.; Moelyadi, M.A. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Based Propeller Design Improvement for High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) UAV. Int. J. Intell. Unmanned Syst. 2023, 11, 425–438. [CrossRef]

- Lissaman, P.B.S. Low-Reynolds-Number Airfoils. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1983, 15, 223–239. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ma, D.; Yang, X. Optimization Design of Propeller for Ultra-High-Altitude Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2364, 012009. [CrossRef]

- Khedr, A.; Castellani, F. Large Eddy Simulation of the Effect of Blade Rotation on Laminar Separation Bubbles in Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 041604. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, J.; Sinnige, T.; Avallone, F.; Ferreira, C. Benchmarking of Aerodynamic Models for Isolated Propellers Operating at Positive and Negative Thrust. AIAA J. 2024, 62, 3758–3775.

- Melani, P.F.; Mohamed, O.S.; Cioni, S.; Balduzzi, F.; Bianchini, A. An Insight into the Capability of the Actuator Line Method to Resolve Tip Vortices. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 601–622. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T.J. Fixed and Flapping Wing Aerodynamics for Micro Air Vehicle Applications; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2001.

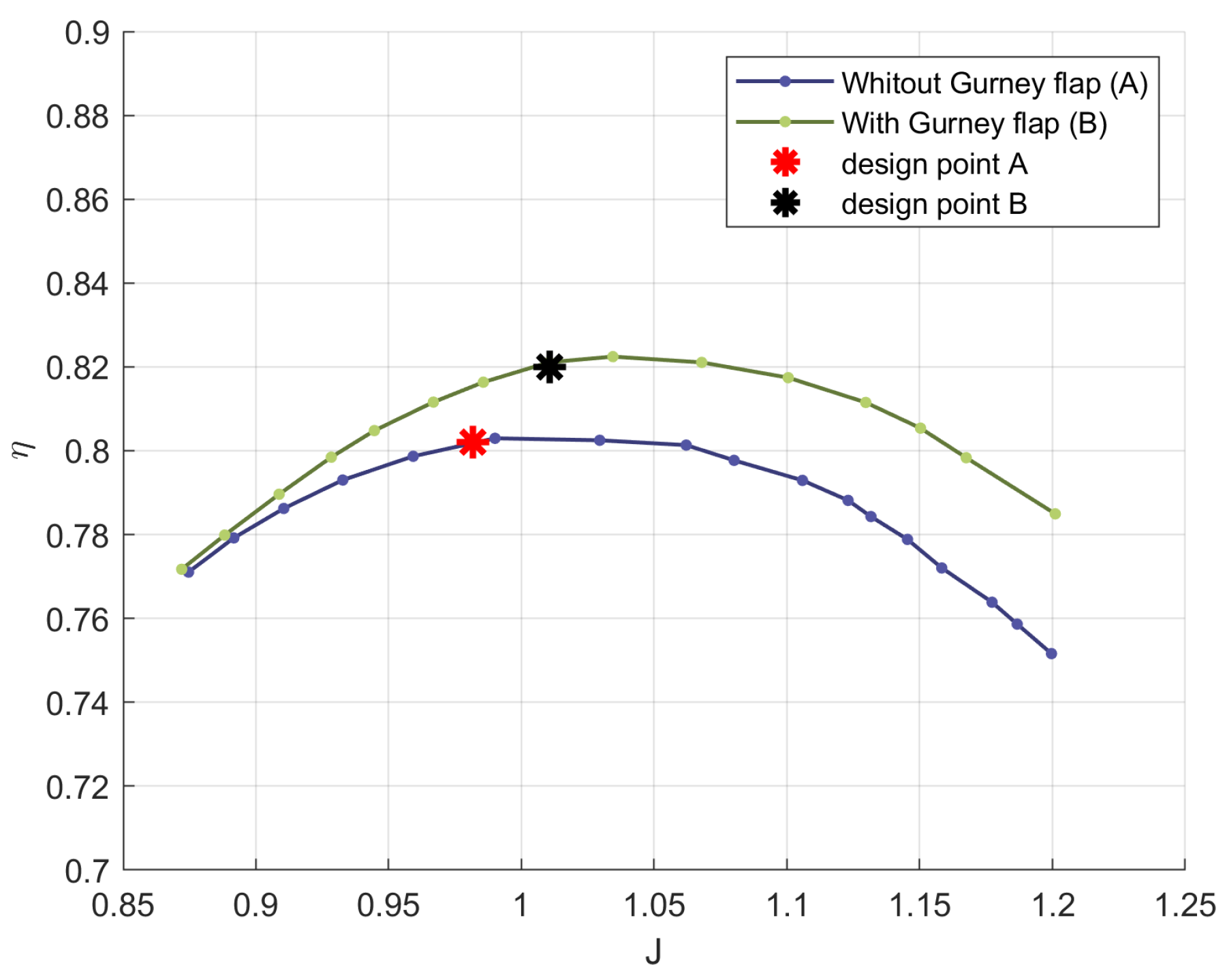

- Yao, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, L.; et al. Aerodynamic Optimization and Analysis of Low Reynolds Number Propeller with Gurney Flap for Ultra-High-Altitude Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3195. [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.S. A Propeller Design and Analysis Capability Evaluation for High Altitude Application. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010.

- Schawe, D.; Rohardt, C.H.; Wichmann, G. Aerodynamic Design Assessment of Strato 2C and Its Potential for Unmanned High Altitude Airborne Platforms. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2002, 6, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- G-520 Egrett. The Perfect Platform for High Altitude Reconnaissance and Surveillance; Grob Company: 1991.

- Egrett II Brochure; E-Systems Greenville Division, 1991.

- Larrabee, E.E. Practical Design of Minimum Induced Loss Propellers. SAE Trans. 1979, 88, 2053–2062.

- Merlin, P.W. Crash Course: Lessons Learned from Accidents Involving Remotely Piloted and Autonomous Aircraft; No. AFRC-E-DAA-TN5128, 2013.

- Morgado, J.; Abdollahzadeh, M.; Silvestre, M.A.R.; et al. High Altitude Propeller Design and Analysis. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 398–407. [CrossRef]

- McCormick, B.W. Aerodynamics, Aeronautics, and Flight Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1979.

- Haque, A.U.; Asrar, W.; Omar, A.A.; et al. Assessment of Engine’s Power Budget for Hydrogen Powered Hybrid Buoyant Aircraft. Propuls. Power Res. 2016, 5, 34–44.

- Harmats, M.; Weihs, D. Hybrid-Propulsion High-Altitude Long-Endurance Remotely Piloted Vehicle. J. Aircr. 1999, 36, 321–331. [CrossRef]

- Bentz, J.C. Fuel Cell Powered Electric Propulsion for HALE Aircraft. In Proceedings of the ASME 1992 International Gas Turbine and Aeroengine Congress and Exposition, Cologne, Germany, 1–4 June 1992; Volume 2.

- Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Song, B. Modeling and Dynamic Simulation Study of Big Inertia Propulsion System of High-Altitude Airship. In Proceedings of the 2011 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Management Science and Electronic Commerce, Dengleng, China, 8–10 August 2011. [CrossRef]

- Colozza, A.J.; Dolce, J. Initial Feasibility Assessment of a High-Altitude Long Endurance Airship; NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS), NASA/CR-2003-212724, 2003.

- Yu, K.; Guo, H.; Sun, Z.; Wu, Z. Efficiency Optimization Control of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor for Electric Propulsion System. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Busan, South Korea, 26–29 October 2013; pp. 56–61; IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Nam, K.; Choi, S.; Kwon, S. Loss Minimizing Control of PMSM with the Use of Polynomial Approximations. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 1071–1082. [CrossRef]

- McElroy, T.; Landrum, D.B. Simulated High-Altitude Testing of a COTS Electric UAV Motor. In Proceedings of the 50th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, Nashville, TN, USA, 9–12 January 2012. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, R.; Scholes, B.; Mustaffer, A.; et al. Design and Experimental Characterization of an Additively Manufactured Heat Exchanger for the Electric Propulsion Unit of a High-Altitude Solar Aircraft. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 September–3 October 2019. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, R.; Scholes, B.; Hussein, A.; et al. A Metal Additively Manufactured (MAM) Heat Exchanger for Electric Motor Thermal Control on a High-Altitude Solar Aircraft—Experimental Characterization. Thermal Sci. Eng. Prog. 2020, 19, 100629. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.; Tashie-Lewis, B.; Laskaridis, P.; et al. Modelling of Distributed-Propulsion Low-Speed HALE UAVs Burning Liquid Hydrogen. SAE Tech. Pap. 2015, No. 2015-01-2467.

- Riboldi, C.; Belan, M.; Cacciola, S.; et al. Preliminary Sizing of High-Altitude Airships Featuring Atmospheric Ionic Thrusters: An Initial Feasibility Assessment. Aerospace 2024, 11, 590. [CrossRef]

- Benford, G.; Benford, J. An Aero-Spacecraft for the Far Upper Atmosphere Supported by Microwaves. Acta Astronaut. 2005, 56, 529–535. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Tao, G.; Wu, Z. Performance Prediction and Design of Stratospheric Propeller. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4698. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, W.; Wei, F. Design of High-Altitude Propeller Using Multilevel Optimization. Int. J. Comput. Methods 2020. [CrossRef]

- Marinus, B.G.; Mourousias, N.; Malim, A. Exploratory Optimizations of Propeller Blades for a High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellite. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2020 Forum, Virtual Event, 15–19 June 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.K.; Wang, X.L.; Cheng, Z.J.; Han, D. The Efficiency Analysis of High-Altitude Propeller Based on Vortex Lattice Lifting Line Theory. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2017, 8, 141–162. [CrossRef]

- Rankine, W.J.M. On the Mechanical Principles of the Action of Propellers. Trans. R. Inst. Nav. Archit. 1865, 6, 13–39.

- Froude, W. On the Elementary Relation between Pitch, Slip, and Propulsive Efficiency. Trans. R. Inst. Nav. Archit. 1878, 19, 22–33.

- Drzewiecki, S. Méthode pour la détermination des éléments mécaniques des propulseurs hélicoïdaux. Bulletin ATM 1892, 3, 11–13.

- Betz, A. Schraubenpropeller mit geringstem Energieverlust. Mit einem Zusatz von L. Prandtl. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen 1919, 193–217.

- Goldstein, S. On the Vortex Theory of Screw Propellers. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1929, 123, 440–465.

- Theodorsen, T. Theory of Propellers; McGraw–Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1948.

- Glauert, H. Airplane Propellers. In Aerodynamic Theory; Durand, W.F., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1935; pp. 169–360.

- Larrabee, E. Propellers of Minimum Induced Loss, and Water Tunnel Tests of Such a Propeller. In Proceedings of the NASA, Ind., Univ., General Aviation Drag Reduction Workshop, Lawrence, Kansas, USA, 14–16 July 1975.

- D’Angelo, S.; Berardi, F.; Minisci, E. Aerodynamic Performances of Propellers with Parametric Considerations on the Optimal Design. Aeronaut. J. 2002, 106, 313–320. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J. Aerodynamic Design of a High Efficient Solar Powered UAV Propeller. Adv. Aeronaut. Sci. Eng. 2020, 11, 02. [CrossRef]

- Ning, A. Using Blade Element Momentum Methods with Gradient-Based Design Optimization. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2021, 64, 991–1014. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, Z. A Method of Propeller Design with Given Thrust Distribution and Its Application. J. Aerosp. Power 2020, 35, 1238–1246. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Gao, Y.; Wei, B. Propeller Design Rule Extraction Based on Rough Set Theory. J. Aerosp. Power 2023, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, W. Performance Calculation and Design of Stratospheric Propeller. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 14358–14368. [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, A.; Gonzalo, J.; Domínguez, D.; et al. Aerodynamic Optimization of Propellers for High Altitude Pseudo-Satellites. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Song, B.F.; Zhang, Y.G.; et al. Optimal Design and Experiment of Propellers for High Altitude Airship. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 232, 1887–1902. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Barakos, G.N.; Foster, M. Multi-Fidelity Aerodynamic Design and Analysis of Propellers for a Heavy-Lift eVTOL. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 135, 108185. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Qing, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Hovering Efficiency Optimization of the Ducted Propeller with Weight Penalty Taken into Account. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 106937. [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Peng, J.; Bai, J.; et al. Aeroacoustic and Aerodynamic Optimization of Propeller Blades. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 826–839. [CrossRef]

- Peters, N.; Silva, C.; Ekaterinaris, J. A Data-Driven Reduced-Order Model for Rotor Optimization. Wind Energy Sci. 2023, 8, 1201–1223. [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Liu, P.; Hu, T.; Akkermans, J. Multi-Fidelity Optimization of a Quiet Propeller Based on Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient and Transfer Learning. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 137, 108288. [CrossRef]

- Kou, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, K.; et al. Aerodynamic Design of High-Altitude Propellers within a Bayesian Optimization Framework. Acta Aerodyn. Sinica 2023, 41, 96–103. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, Z. A Quick Design Method of Propeller Coupled with CFD Correction. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2020, 41, (2).

- Kwon, H.I.; Yi, S.; Choi, S.; et al. Design of Efficient Propellers Using Variable Fidelity Aerodynamic Analysis and Multilevel Optimization. J. Propuls. Power 2015, 31, 1057–1072. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ma, D.; Zhang, L. High-Fidelity Multi-Level Efficiency Optimization of Propeller for High Altitude Long Endurance UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zuo, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W. Multi-Fidelity Neural Network-Based Aerodynamic Optimization Framework for Propeller Design in Electric Aircraft. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 108963. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ning, C.; Wang, W.; et al. Intelligent Fusion Method of Multi-Source Aerodynamic Data for Flight Tests. Acta Aerodyn. Sinica 2023, 41, 12–20. [CrossRef]

- Mourousias, N.; Malim, A.; Marinus, B.G.; et al. Multi-Fidelity Multi-Objective Optimization of a High-Altitude Propeller. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2023 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Drela, M. XFOIL: An Analysis and Design System for Low Reynolds Number Airfoils. In Low Reynolds Number Aerodynamics: Proceedings of the Conference; Mueller, T.J., Ed.; Notre Dame, USA, 1989. [CrossRef]

- Marinus, B.G.; Akila, H.; Constantin, L.; et al. Effect of Rotation on the 3D Boundary Layer around a Propeller Blade. In Proceedings of the 23rd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Denver, Colorado, USA, 5–9 June 2017. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ma, L.; Duan, Z.; et al. Study and Verification on Similarity Theory for Propellers of Stratospheric Airships. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2012, 7, 957.

- Sodja, J.; Stadler, D.; Kosel, T. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of an Optimized Load-Distribution Propeller. J. Aircr. 2012, 49, 955–961. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tao, G. Numerical Simulation of High-Altitude Propeller’s Aerodynamic Characteristics and Wind Tunnel Test. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2013, 39, 1102.

- Nigam, N.; Tyagi, A.; Chen, P.; et al. Multi-Fidelity Multi-Disciplinary Propeller/Rotor Analysis and Design. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Kissimmee, Florida, USA, 5–9 January 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mourousias, N.; García-Gutiérrez, A.; Malim, A.; et al. Uncertainty Quantification Study of the Aerodynamic Performance of High-Altitude Propellers. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, J.; Riffo, S.; Salomon, J. Analysis of the Blade Element Momentum Theory. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2021, 81, 2596–2621. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, K. High-Robustness Nonlinear-Modification Method for Propeller Blade Element Momentum Theory. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2018, 39, 32–45. [CrossRef]

- Mahmuddin, F. Rotor Blade Performance Analysis with Blade Element Momentum Theory. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 1123–1129. [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, E.V.; Oliveira, N.L.; Hallak, P.H.; et al. Evaluation of Low-Fidelity and CFD Methods for the Aerodynamic Performance of a Small Propeller. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 106402. [CrossRef]

- Fiddes, S.P.; Brown, K.; Bunniss, P.C. Optimum Propellers Revisited—Beyond Blade Element Theory. In Proceedings of the 19th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS), Anaheim, California, USA, 18–23 September 1994.

- Adkins, C.N.; Liebeck, R.H. Design of Optimum Propellers. J. Propuls. Power 1994, 10, 676–682. [CrossRef]

- Rwigema, M.K. Propeller Blade Element Momentum Theory with Vortex Wake Deflection. In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress of the Aeronautical Sciences, Nice, France, 19–24 September 2010.

- MacNeill, R.; Verstraete, D. Blade Element Momentum Theory Extended to Model Low Reynolds Number Propeller Performance. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2017, 121, 835–857. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, P.; Hu, T.; et al. Experimental Investigations on High Altitude Airship Propellers with Blade Planform Variations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 232, 2952–2960. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, P.; Qu, Q.; et al. Effect of Advance Ratio and Blade Planform on the Propeller Performance of a High-Altitude Airship. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2016, 9, 2993–3000. [CrossRef]

- Fradenburgh, E.A.; Matuska, D.G. Advancing Tiltrotor State-of-the-Art with Variable Diameter Rotors. In Proceedings of the 48th American Helicopter Society International Annual Forum, Washington, DC, USA, 3–5 June 1992.

- Beemer, J.D. POBAL-S, the Analysis and Design of a High-Altitude Airship; DTIC Document, ADA012292, 1975.

- Okuyama, M.; Shibata, M.; Yokokawa, A.; et al. Study of Propulsion Performance and Propeller Characteristics for Stratospheric Platform Airship. JAXA Res. Dev. Rep. 2006, 5, 1–23.

- Kim, D.M. Korea Stratospheric Airship Program and Current Results. In Proceedings of the AIAA 3rd Annual Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (ATIO) Forum, Denver, Colorado, USA, 17–19 November 2003. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Duan, Z.; Ma, L.; et al. Aerodynamics Properties and Design Method of High Efficiency-Light Propeller of Stratospheric Airships. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Remote Sensing, Environment and Transportation Engineering (RSETE), Nanjing, China, 24–26 June 2011. [CrossRef]

- Dumas, A.; Pancaldi, F.; Anzillotti, F.; et al. High Altitude Platforms for Telecommunications: Design Methodology. SAE Tech. Pap. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, J.D.; Heiser, W.H.; Pratt, D.T. Aircraft Engine Design; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Morgado, J.; Silvestre, M.Â.R.; Páscoa, J.C. Validation of New Formulations for Propeller Analysis. J. Propuls. Power 2015, 31, 467–477. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, S. Navier-Stokes Equations-Based Flow Simulations of Low Reynolds Number Propeller for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 55th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Grapevine, Texas, USA, 9–13 January 2017. [CrossRef]

- Svorcan, J.; Hasan, M.S.; Baltić, M.; et al. Optimal Propeller Design for Future HALE UAV. Sci. Tech. Rev. 2019, 69, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, H.; Cardoş, V.; Dumitrache, A. Modelling of Inboard Stall Delay Due to Rotation. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2007, 75, 012022. [CrossRef]

- Morgado, J.C.P.J.; Vizinho, R.; Silvestre, M.A.R.; et al. XFOIL vs CFD Performance Predictions for High Lift Low Reynolds Number Airfoils. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 52, 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Lee, Y.; Cho, T.; et al. Design and Performance Evaluation of Propeller for Solar-Powered High-Altitude Long-Endurance Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, X.; Duan, D.; Xie, W. Optimization and Analysis of Efficiency for Contra-Rotating Propellers for High-Altitude Airships. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2019, 123, 706–726. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Muñoz, H.; Catalano, F. Aerodynamic Analysis of High Rotation and Low Reynolds Number Propeller. In Proceedings of the 48th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 30 July–1 August 2012. [CrossRef]

- Breton, S.P.; Coton, F.N.; Moe, G. A Study on Rotational Effects and Different Stall Delay Models Using a Prescribed Wake Vortex Scheme and NREL Phase VI Experiment Data. Wind Energy Int. J. Progr. Appl. Wind Power Convers. Technol. 2008, 11, 459–482. [CrossRef]

- Lanzafame, R.; Messina, M. BEM Theory: How to Take into Account the Radial Flow Inside of a 1-D Numerical Code. J. Renew. Energy 2012, 39, 440–446. [CrossRef]

- Bak, C.; Johansen, J.; Andersen, P.B. Three-Dimensional Corrections of Airfoil Characteristics Based on Pressure Distributions. In Proceedings of the 2006 European Wind Energy Conference and Exhibition, Athens, Greece, 27 February–2 March 2006.

- Corrigan, J.J.; Schillings, J.J. Empirical Model for Stall Delay Due to Rotation. In Proceedings of the American Helicopter Society Aeromechanics Specialists Conference, San Francisco, California, USA, 19–21 January 1994.

- Snel, H.; Houwink, R.; Bosschers, J.; et al. Sectional Prediction of 3-D Effects for Stalled Flow on Rotating Blades and Comparison with Measurements. Netherlands Energy Research Foundation (ECN), ECN-RX-93-028, 1993. https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/6222685. Accessed 20 November 2024.

- Du, Z.; Selig, M.S. A 3-D Stall-Delay Model for Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine Performance Prediction. In Proceedings of the 1998 ASME Wind Energy Symposium, Reno, Nevada, USA, 12–15 January 1998. [CrossRef]

- Chaviaropoulos, P.K.; Hansen, M.O.L. Investigating Three-Dimensional and Rotational Effects on Wind Turbine Blades by Means of a Quasi-3D Navier–Stokes Solver. J. Fluids Eng. 2000, 122, 330–336. [CrossRef]

- Wauters, J.; Degroote, J. On the Study of Transitional Low-Reynolds Number Flows over Airfoils Operating at High Angles of Attack and Their Prediction Using Transitional Turbulence Models. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 103, 52–68. [CrossRef]

- Koch, L.D. Design and Performance Calculations of a Propeller for Very High-Altitude Flight. NASA Technical Memorandum NASA-TM-1998-206637, 1998. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19980017535. Accessed 20 November 2024.

- Coiro, D.P.; de Nicola, C. Prediction of Aerodynamic Performance of Airfoils in Low Reynolds Number Flows. In Low Reynolds Number Aerodynamics: Proceedings of the Conference; Mueller, T.J., Ed.; Notre Dame, 1989.

- Mourousias, N.; Malim, A.; Marinus, B.G.; et al. Surrogate-Based Optimization of a High-Altitude Propeller. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2021 Forum, Virtual Event, 2–6 August 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Han, Z.; Song, W.; et al. Efficient Aerodynamic Optimization of Propeller Using Hierarchical Kriging Models. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Song, W.; Yang, X.; et al. Aerodynamic Performance of Variable-Pitch Propellers for High-Altitude UAVs. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mourousias, N.; Malim, A.; Marinus, B.G.; et al. Assessment of Multi-Fidelity Surrogate Models for High-Altitude Propeller Optimization. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2022 Forum, Chicago, IL, USA, 27 June–1 July 2022. [CrossRef]

- Traub, L.W. Considerations in Optimal Propeller Design. J. Aircr. 2021, 58, 950–957. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.H.; Hoyos, J.D.; Echavarría, C.; et al. Exhaustive Analysis on Aircraft Propeller Performance through a BEMT Tool. J. Aeronaut. Astronaut. Aviat. 2022, 54, 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.A.; Erhard, R.M.; Smart, J.T.; et al. Aerodynamic Optimization of Wing-Mounted Propeller Configurations for Distributed Electric Propulsion Architectures. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2021 Forum, 2021, p. 2471.

- Riccio, E.; Giaquinto, C.; Baraniello, V.R.; et al. Preliminary Conceptual Design for a Box-Wing High Altitude Pseudo Satellite. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2025 Forum, 2025, p. 0461.

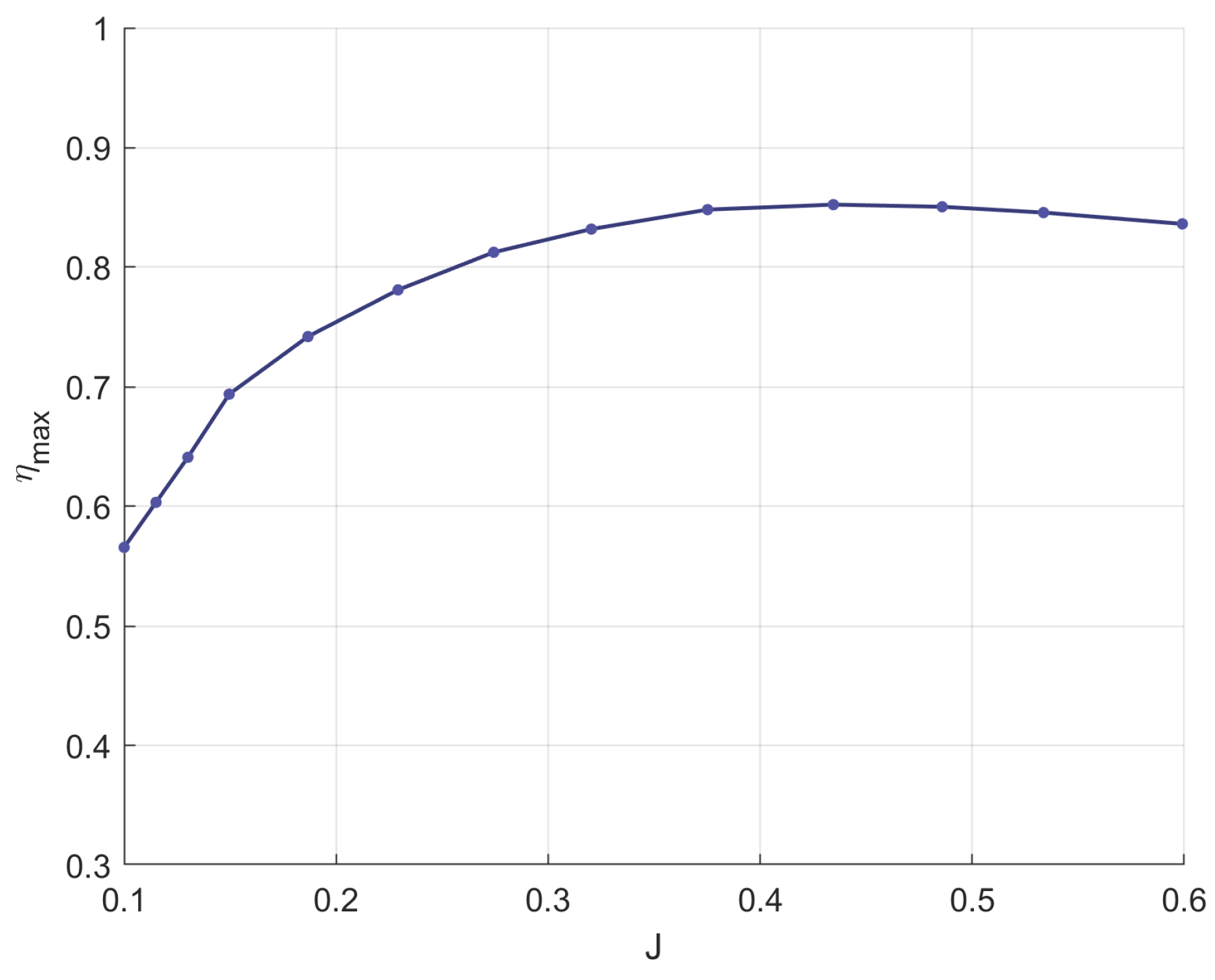

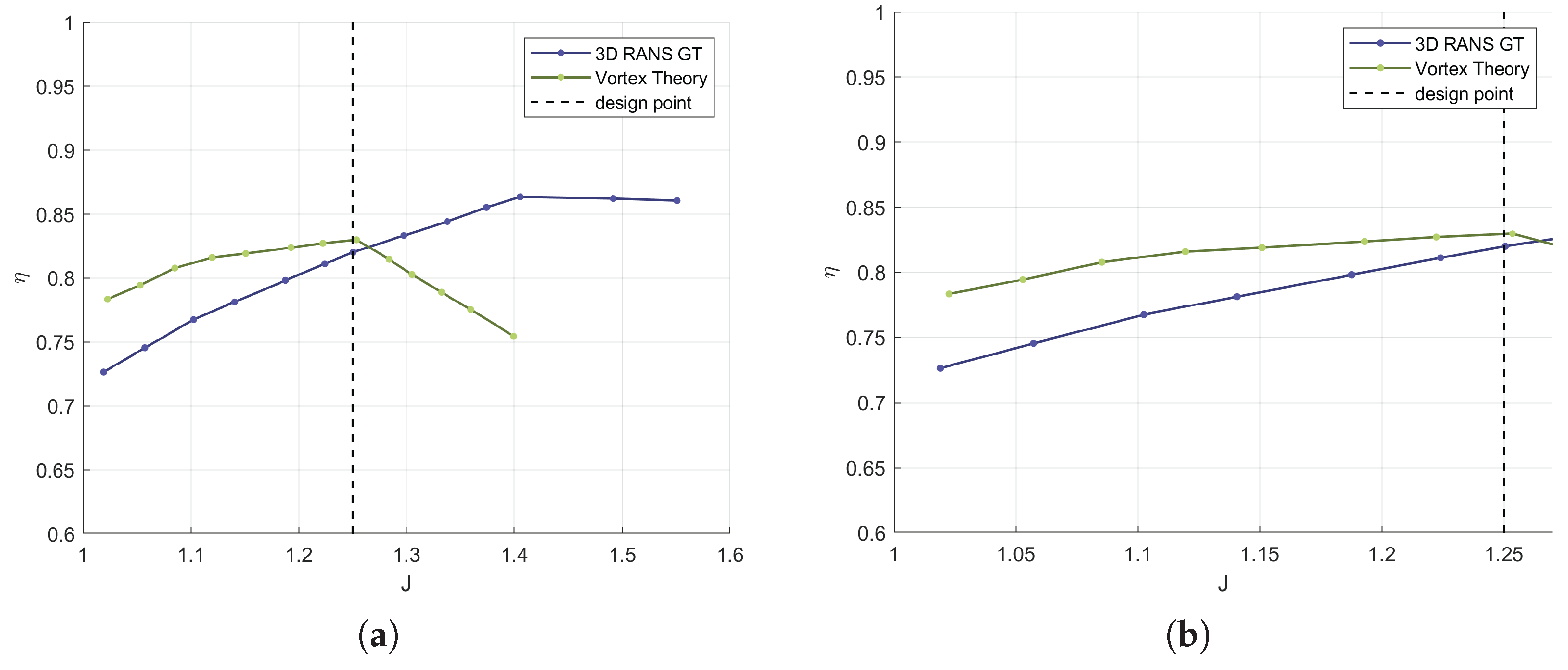

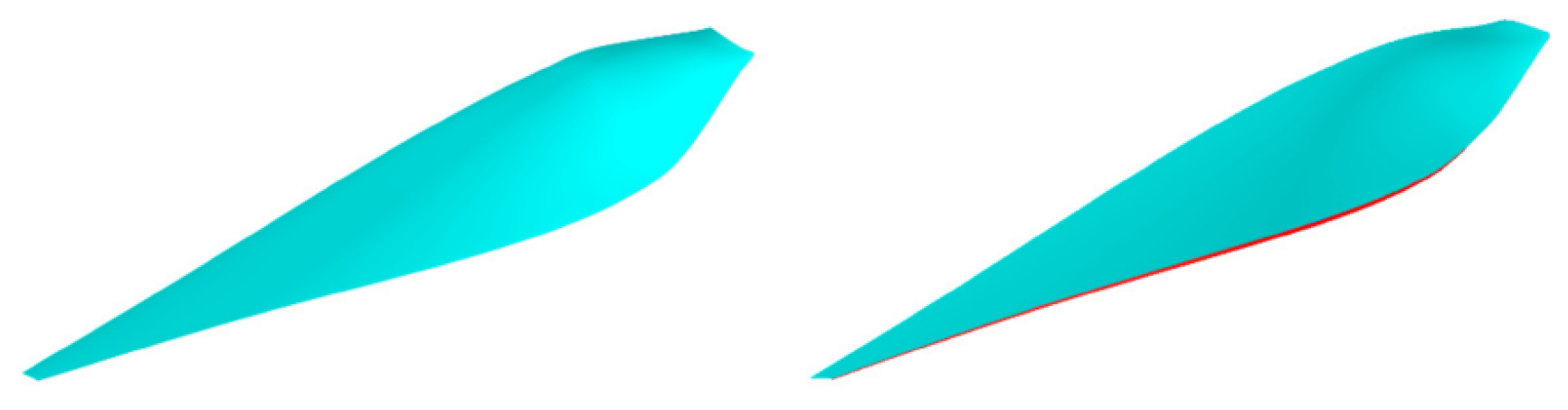

- Mourousias, N.; Marinus, B.G.; Runacres, M.C. A novel multi-fidelity optimization framework for high-altitude propellers. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 109407.

- Wald, Q.R. The aerodynamics of propellers. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2006, 42, 85–128.

- Kerwin, J.E.; Coney, W.B.; Hsin, C. Optimum circulation distributions for single and multi-component propulsors. In Proceedings of the 21st American Towing Tank Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 July 1986.

- Coney, W.B. A method for the design of a class of optimum marine propulsors. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989.

- García-Gutiérrez, A.; Gonzalo, J.; López, D.; Delgado, A. Stochastic design of high-altitude propellers. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, , 106283. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Song, B.; Li, Y. Development of a testing methodology for high-altitude propeller. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Tec. 2017, 9, 1486–1494. [CrossRef]

- Wolowicz, C.H.; Brown Jr, J.S.; Gilbert, W.P. Similitude requirements and scaling relationships as applied to model testing. NASA-TP-1435, 1979. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19790022005. Accessed 20 November 2024.

- Baltazar, J.; Rijpkema, D.; Falcão de Campos, J. Prediction of the propeller performance at different Reynolds number regimes with RANS. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 115. [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.B.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.; Hilbert, G. Scale effects on propellers for large container vessels. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Marine Propulsors - SMP’09, Trondheim, Norway, 22–24 June 2009.

- Wang, X.; Walters, K. Computational analysis of marine-propeller performance using transition-sensitive turbulence modelling. J. Fluids Eng. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, S.; Basnet, P.; Khadka, T.B.; et al. Analysis and Comparison of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle’s Propellers for High Altitude Search and Rescue Missions. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385751605_Analysis_and_Comparison_of_Unmanned_Aerial_Vehicle’s_Propellers_for_High_Altitude_Search_and_Rescue_Missions (accessed on 20 November 2024).

| Year | Aircraft Name | Nominal Thrust [N] | Propeller Diameter [m] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Egrett [48,49] | 2773 | 3.04 |

| 1988 | Condor [26] | 1129 | 4.90 |

| 1993 | Pathfinder [26,46] | 23 | 2.01 |

| 1994 | Perseus [20] | 388 | 4.40 |

| 1995 | Strato2C [46,47] | 2500 | 6.00 |

| 1996 | Theseus [51] | 409 | 2.74 |

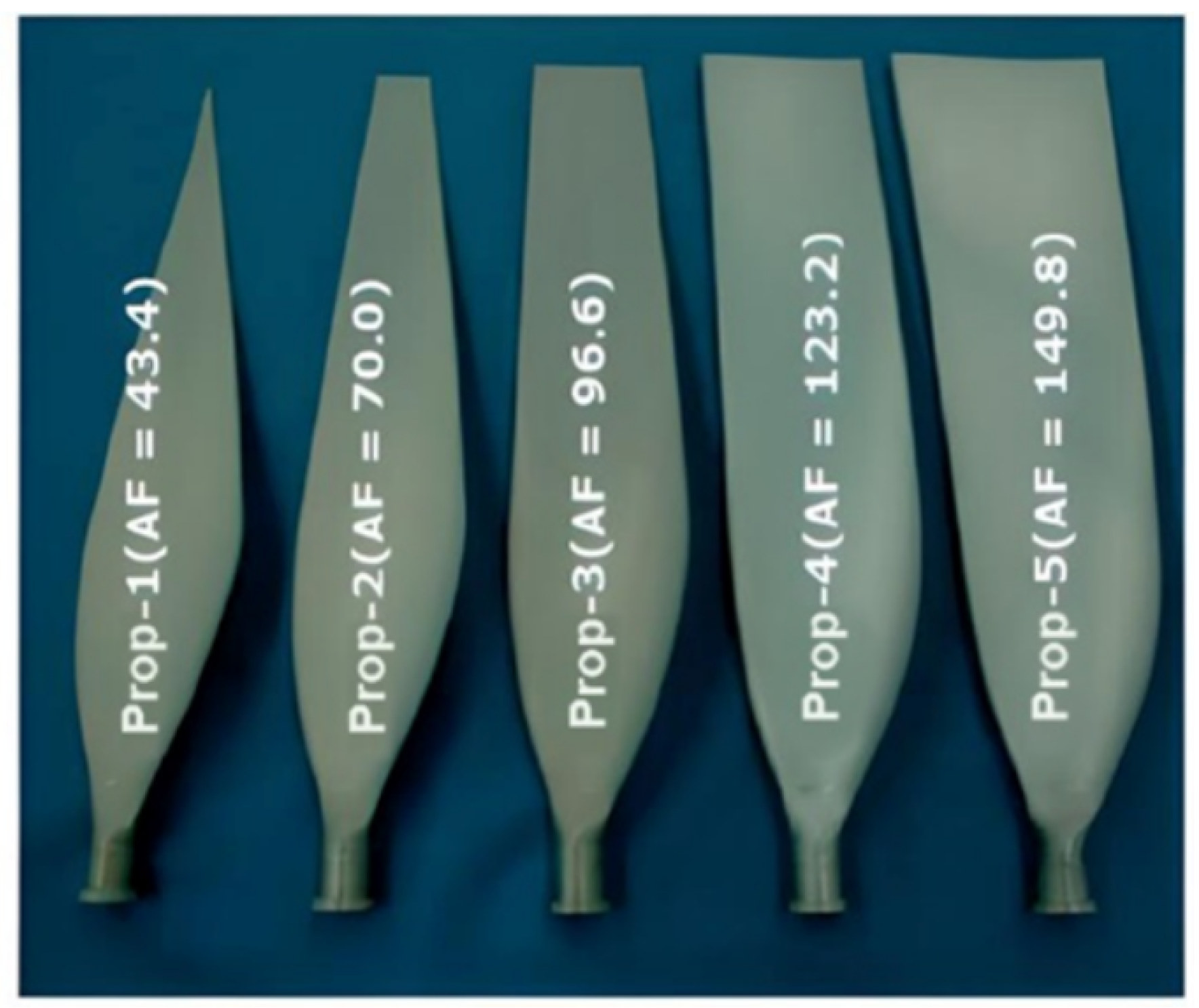

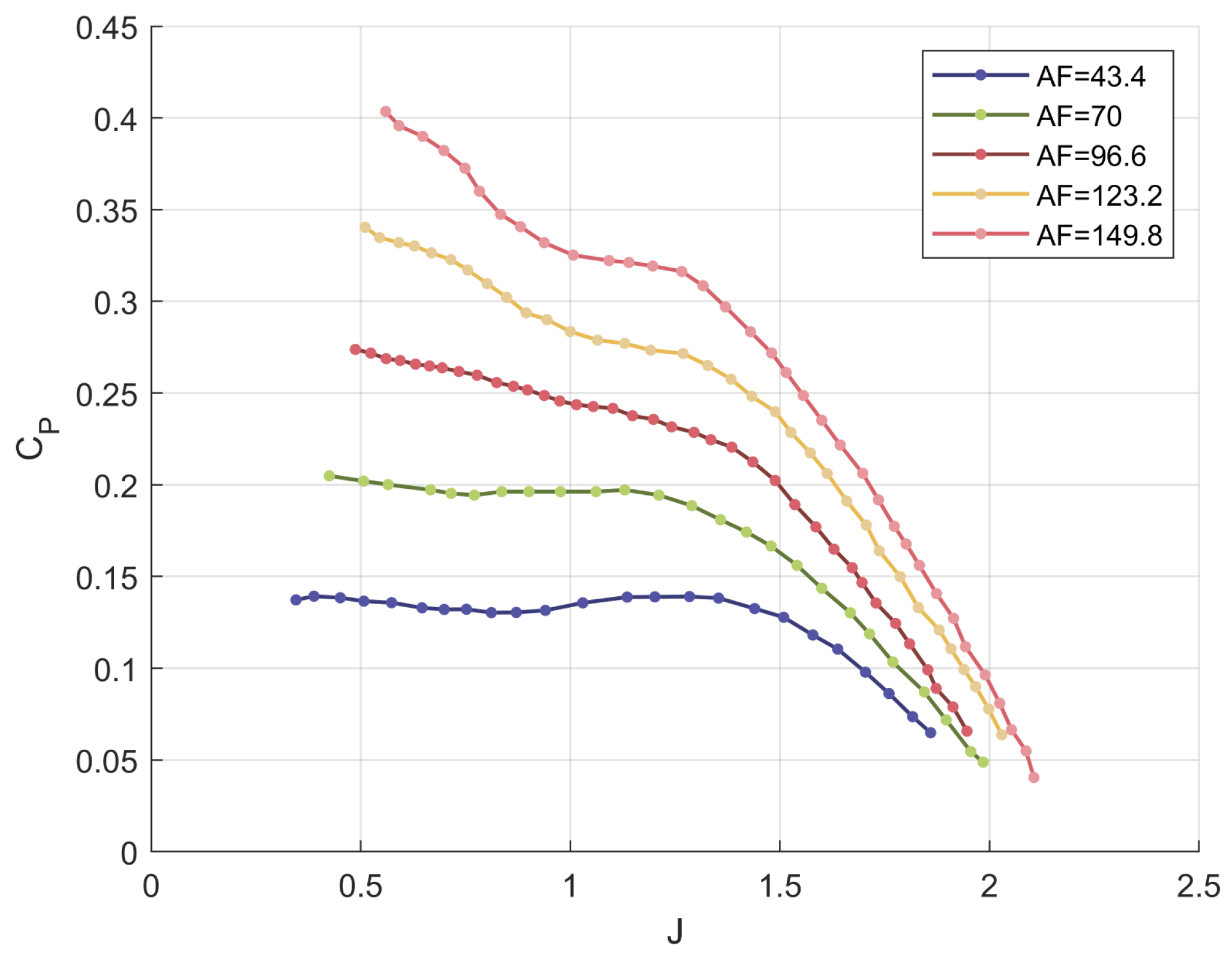

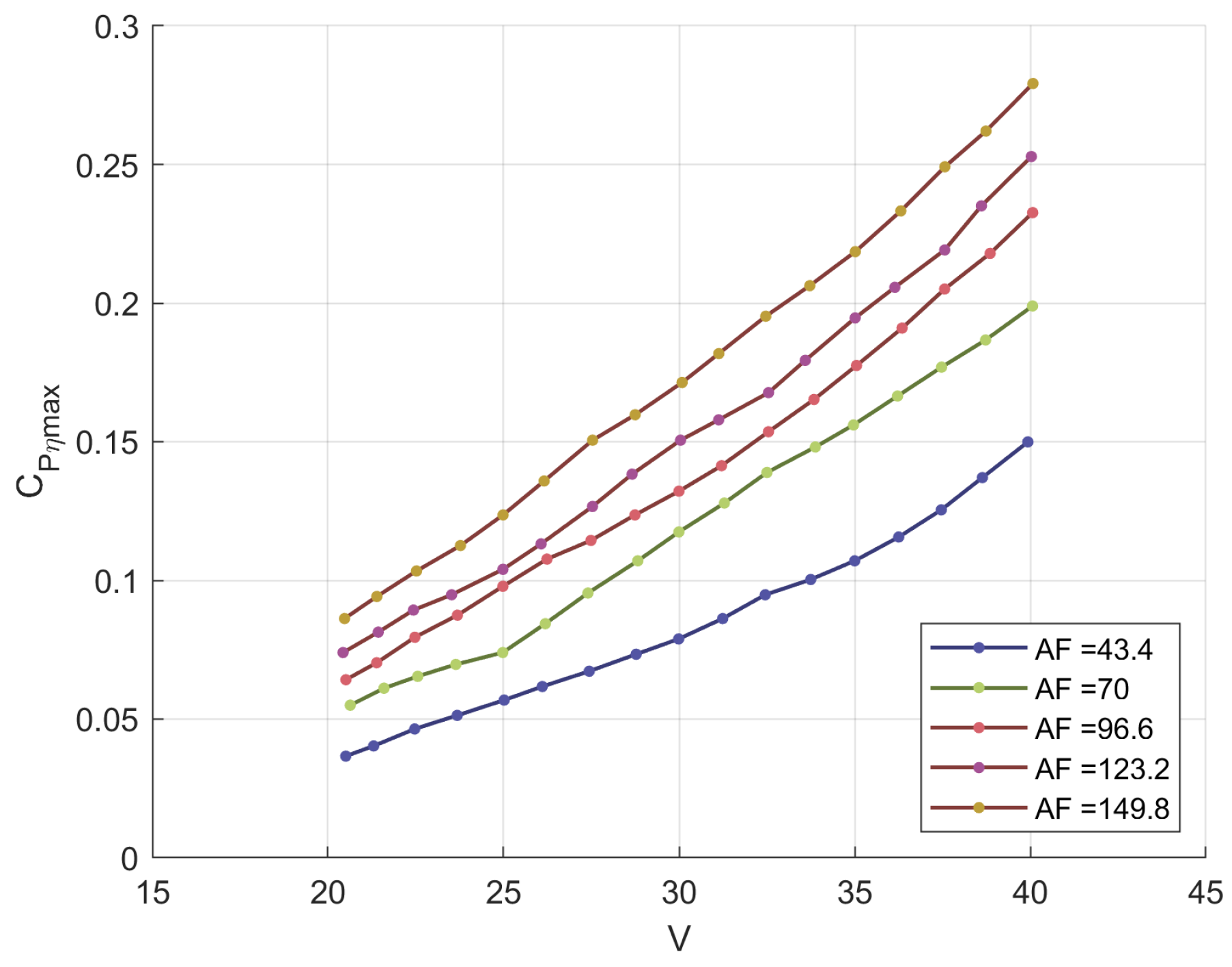

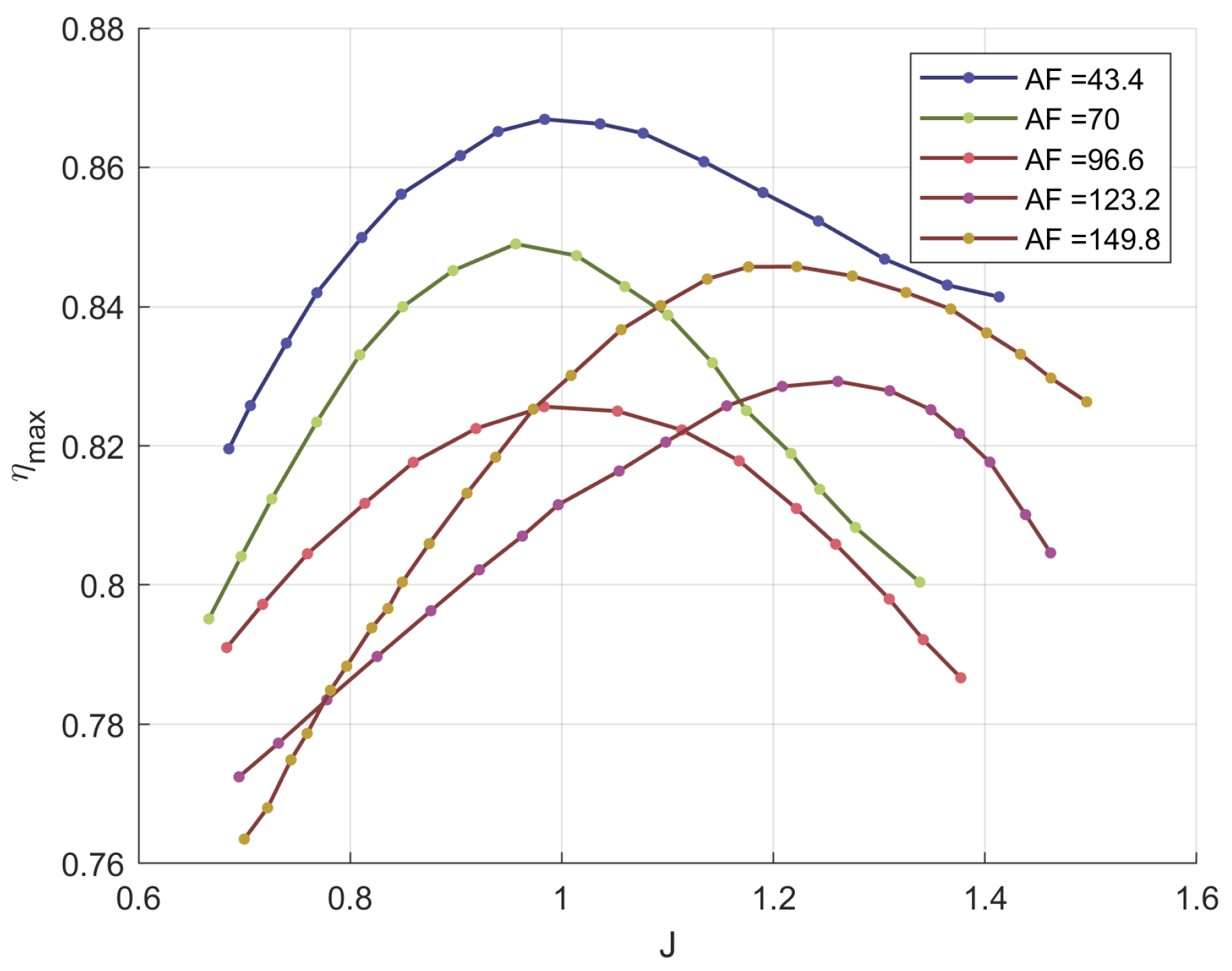

| Propeller | AF | D (m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propeller 1 | 43.4 | 0.85 | 2 | 0.87 |

| Propeller 2 | 70.0 | 0.85 | 2 | 0.85 |

| Propeller 3 | 96.6 | 0.85 | 2 | 0.83 |

| Propeller 4 | 123.2 | 0.85 | 2 | 0.83 |

| Propeller 5 | 149.8 | 0.85 | 2 | 0.85 |

| References | Maximum Efficiency [%] | Optimization Technique and Design Method | Model Used in Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

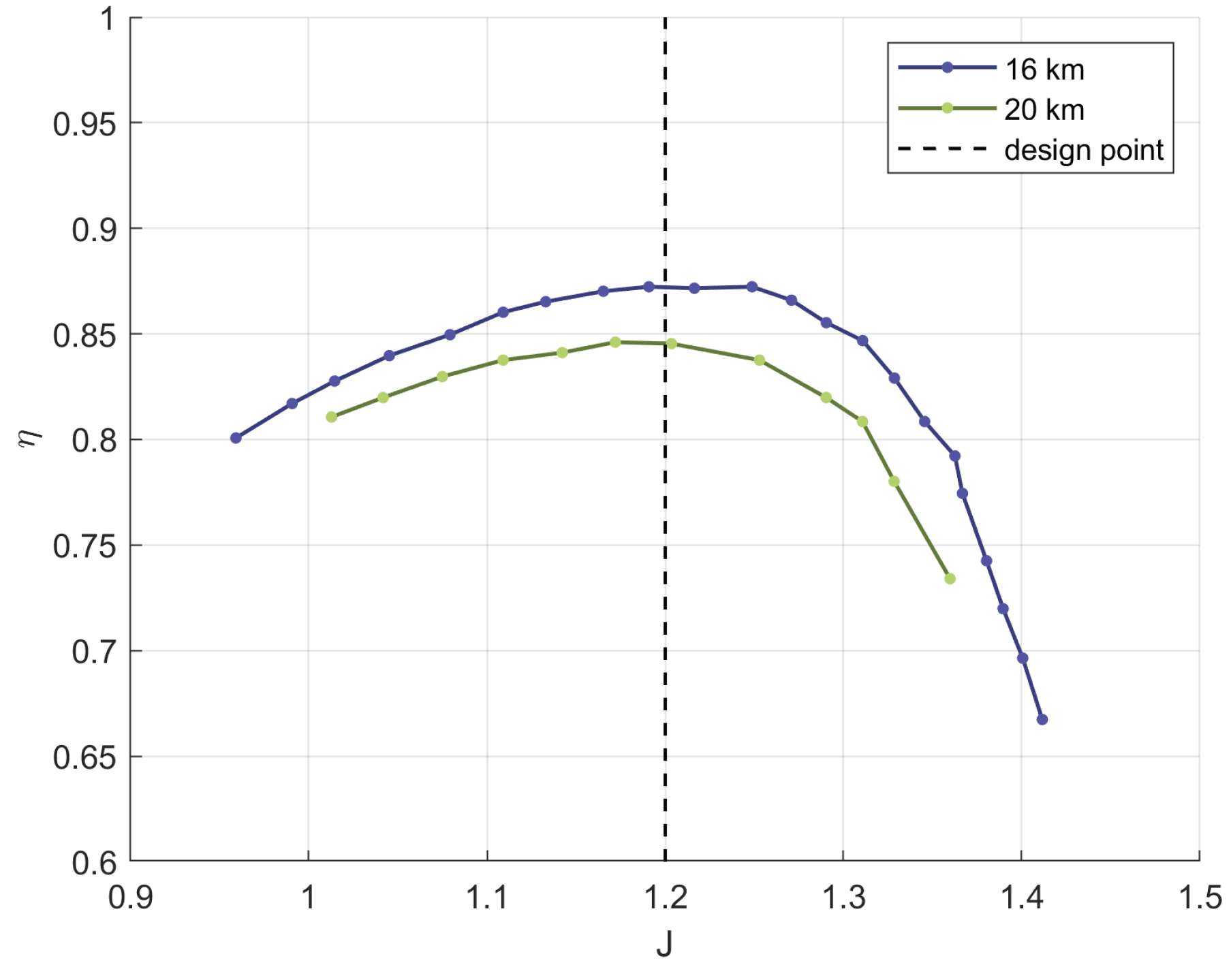

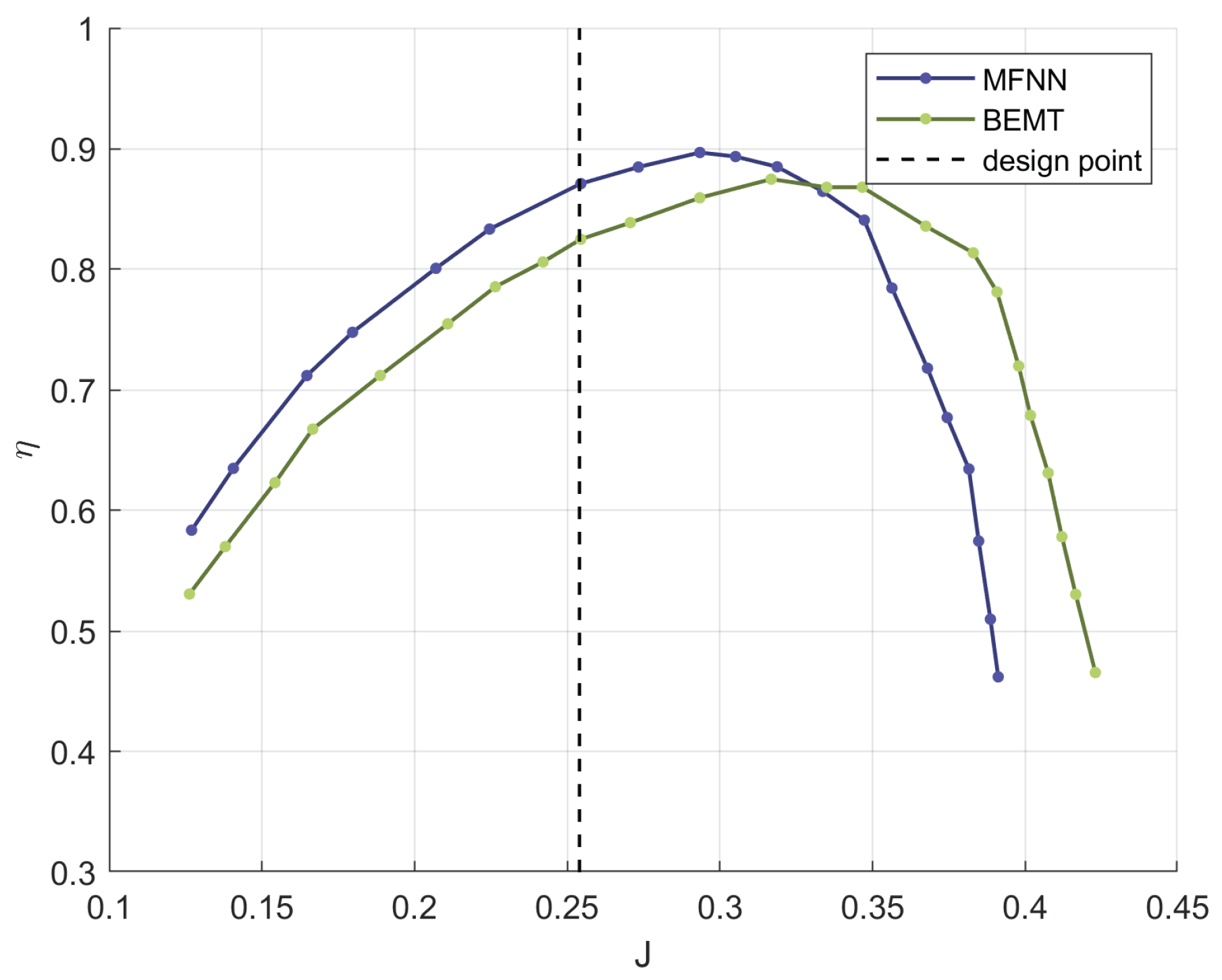

| Wu et al. [96], 2024 | 87.1 | Multi-Fidelity Neural Network (MFNN)-based optimization | 3D RANS / BEMT |

| Mourousias et al. [149], 2024 | 86 | Multi-fidelity multi-objective Bayesian optimization | 3D RANS / Vortex Theory |

| Mourousias et al. [98], 2023 | 85 | Multi-fidelity Bayesian optimization | 3D RANS / Vortex Theory |

| Gutiérrez et al. [85], 2020 | 85 | Based on Wald design method [150] | BEMT |

| Mourousias et al. [144], 2022 | 84.2 | Bayesian optimization | 3D RANS |

| Marinus et al. [69], 2020 | 82.3 | Genetic algorithm (PSO) | Vortex Theory |

| Yao et al. [45], 2022 | 82 | Multi-level: Level 1 Betz method, Level 2 Genetic algorithm, Level 3 Genetic algorithm | 2D RANS / 3D RANS |

| Xu et al. [143], 2019 | 81.84 | Bayesian optimization | 3D RANS |

| Yang et al. [95], 2023 | 79.29 | Multi-level: Level 1 discrete adjoint, Level 2 parametric perturbation, Level 3 flow pattern reconstruction | 2D RANS / 3D RANS / BEMT |

| Tang et al. [129], 2019 | 78.07 (VLM), 65.2 (CFD) | Based on Kerwin’s design method [151] with VLM for contra-rotating propellers | VLM |

| Jiao et al. [86], 2018 | 75 (calculated), 70.5 (experimental scale model) | Genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) | Vortex Theory |

| Zheng et al. [70], 2017 | 73.48 (VLM), 66 (CFD) | Based on Coney’s design method [152] with VLM | VLM |

| Morgado et al. [52], 2015 | 73.2 | Based on Adkins-Liebeck design method | BEMT |

| Park et al. [128], 2018 | 65.4 | Multi-level: Level 1 inverse design based on Adkins and Liebeck, Level 2 RSM and desirability function | BEMT |

| Altitude (km) | Wind speed (m/s) | RPM | Shaft Power | Max Thrust | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 25 | +43.54% | +42.35% | +36.47% | -4.06% |

| 15 | 15 | +112.17% | +112.11% | +75.06% | -17.48% |

| 10 | 10 | +139.89% | +140.66% | +83.14% | -23.85% |

| 5 | 8 | +141.37% | +141.38% | +79.46% | -29.19% |

| 0 | 6 | +156.81% | +159.09% | +78.85% | -30.86% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).