1. Introduction

Injectable hydrogels have extensive applications in regenerative medicine due to their high tissue-like water content, ability to homogeneously encapsulate cells, efficient mass transfer, and easily manipulated physical properties [

1]. It can be injected into the defect site to encounter any geometrical deformities, and with minimally invasive procedures, unlike the prefabricated scaffold, which needs surgical implantation. Injectable hydrogels, when used at the defect site, deliver the loaded content and then form a gel through transitional properties when a response to a stimulus changes the physical and/or chemical properties. Different types of injectable scaffolds, such as microparticles, hydrogel, nano-composite films, and nanoparticles, have been developed using biomaterials such as natural and synthetic polymers [

2].

Natural polymers used include chitosan, cellulose, gelatin, xyloglucan, alginate, hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate, carrageenan, dextran, pullulan, and their respective derivatives. Synthetic polymer materials comprise poly-N-isopropylacrylamide (PNIPAAM), poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(propylene oxide)-b-poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO/PPO/PEO) block copolymers, poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(D, L-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid)-poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO/PLGA/PEO) triblock copolymers, and amphiphilic tri-block copolymers composed of PEO and poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) (PEO/PCL/PEO) [

3]. Among these two types, natural-based hydrogels are extensively researched due to their outstanding biological features. Among them, chitosan has a wide range of applications owing to its unique physico-chemical and biological properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, nontoxicity, inertness, strong affinity for proteins, and intrinsic antibacterial activity. Other valuable properties encompass moldability into various forms, compatibility with a wide range of delivery materials, drug-carrying capacity, interconnected-porous structure formability, cationic nature, and the ability to engage in electrostatic interactions with anionic glycosaminoglycans (GAG) and proteoglycans, as well as other negatively charged species. However, significant drawbacks of hydrogels made from collagen and/or chitosan are their limited mechanical strength and rapid biodegradation [

4].

One of the strategies dedicated to improving the mechanical properties of the component hydrogel network is the addition of clays and nanoparticles (NPs) to polymer solutions that may act as cross-linkers [

5]. This strategy may allow the formation of composite gels that are mechanically stronger due to the integration of entities supporting dissipative mechanisms [

6]. These nanoparticles either cross-link the hydrogel or adsorb polymer chains by being entrapped within the hydrogel network. The added nanoparticles may give new properties, such as mechanical toughness, large deformability, and high swelling rates, to the gels normally without changing the polymer network structures [

7].

Lately, silica-based nanoparticles have been used extensively for various biomedical applications due to their excellent properties of elastic modulus, strength, and toughness, providing a prime micro-structural design model for the development of new materials. Silica possesses a large surface area and smooth nonporous surface, encouraging strong physical contact between the filler and the polymer matrix [

8]. Recently, many efforts have been spent on the use of silica nanoparticles to fabricate mechanically strong nanocomposite hydrogel networks [

9,

10,

11]. The hypothesis proposed by researchers is that strong polymer/nanofiller interactions might facilitate the formation of non-covalent or pseudo-crosslinks, thereby contributing to improvements in polymer properties [

12].

Commercial silica is produced by the reaction of sodium silicate with organic acids. The manufacture of sodium silicate is expensive. Rice husk is, therefore, utilized as a natural source of sodium silicates for silica production [

13]. It is found that the silica content in rice husk ash, which is prepared by preliminary leaching of rice husks with a solution of hydrochloric acid before their combustion, can be as high as 99.5% [

14]. Fuad et al. [

15] studied the effect of silica, obtained from rice husk ash (RHA-Si), on the mechanical properties of polypropylene. It was found that the tensile strength, elongation at break, and impact strength were found to be decreased. The results were explained by poor polymer-filler interaction between polypropylene and RHA-Si. In the study of Siriwardena et al. [

16], the effect of RHA-Si on the physical properties of ethylene-propylene-diene rubber (EPDM) was investigated. It was concluded that RHA-Si could not reinforce EPDM, although it did not decrease the physical properties of the EPDM. On the other hand, Saowapark et al.’s study found that the mechanical properties of deproteinized natural rubber could be improved by adding RHA-Si. However, the RHA-Si adding in dental materials, such as acrylic resin denture bases, could increase flexural strength, and polymer-filler interaction was used as the explanation [

17].

In this research, the initial objective was to conduct experiments in further support of the pseudo-crosslinking hypothesis using chitosan/collagen hydrogels incorporating RHA-Si as the model system. The injectable thermosensitive chitosan/collagen hydrogel reinforced with silica nanoparticles derived from rice husk ash (RHA-Si) was developed and characterized, focusing on the impact of RHA-Si content on chemical structure, morphology, porosity, mechanical, and rheological behavior of the hydrogel system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Silica Nanoparticles

Rice husk was washed with distilled water and then air-dried at room temperature. The washed rice husk is refluxed with 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl; RCI Labscan, Bangkok, Thailand) at 90 °C for an hour. After that, the HCl solution was completely removed from the rice husk by washing it with distilled water. The refluxed rice husk was dried overnight in an oven at 60 °C, and then it was burnt in an electric furnace at 700 °C for 5 hours. RHA-Si was finally obtained in the form of white ash and was ground into a powder. The chemical composition and structure of RHA-Si were then investigated with an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer to confirm that RHA-Si had a large silica content with an amorphous structure.

2.2. Preparation of Thermosensitive Chitosan/Collagen Hydrogels

Chitosan solution (2% w/v) was prepared by dissolving chitosan (medium molecular weight; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0.1 M acetic acid at room temperature under moderate mechanical stirring for 24 hours. An aqueous solution of atelocollagen (1%) was added to the prepared chitosan solution with a 75/25 % volume ratio of chitosan/collagen. To prepare the nanocomposite hydrogel, RHA-Si was added to the chitosan/collagen mixtures with various loadings of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 % w/v, and then an aqueous solution of β-glycerophosphate (β-GP; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) concentration of 56% w/v was added dropwise to the mixture with 20 % w/v in an ice bath. The prepared hydrogel solution was kept at 4 °C to maintain a liquid state with a pH between 7.0 and 7.4 for the hydrogel formation. The gelation of the hydrogel was achieved by incubating the solution at 37°C.

2.3. Chemical Characterization of Hydrogels by Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

The freeze-dried hydrogels were prepared through lyophilization, a process in which ice is removed via sublimation under vacuum conditions for 48 hours, to investigate the chemical functional group using FTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet is5; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The spectra were recorded at room temperature in the wavenumber range of 600-4000 cm-1.

2.4. Morphological and Porosity Analysis of Hydrogels Using Micro-CT

The morphological structure of the freeze-dried hydrogels was analyzed using Micro-Computed Tomography (SkyScan 1173; Bruker microCT, Kontich, Belgium). The samples were scanned under optimized parameters to capture their morphology, followed by image reconstruction and processing to assess the porosities within the hydrogel network. Additionally, the porosity of the prepared hydrogels was quantified using the SKY SCAN.

2.5. Rheological Measurements

Rheological measurement of chitosan/collagen hydrogel containing RHA-Si was performed using a parallel plate rheometer (HAAKE MARS; Thermo Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany). A time sweep test was conducted to monitor the effect of RHA-Si concentration on the setting time of the hydrogel, which was performed at a temperature of 37°C, frequency of 1 Hz, and strain of 5%. The resultant storage modulus or elastic modulus (G′) and loss modulus or viscous modulus (G″) are recorded for 30 minutes. The strain sweep test (varying from 0.01 – 10%) is carried out to investigate the rheological behavior of the hydrogels in a linear viscoelastic region (LVR) at 37°C and frequency of 1 Hz.

2.6. Mechanical Test

Compression force at a given displacement was used to evaluate the mechanical properties of the freeze-dried hydrogel samples. The sample specimens were prepared in a plastic mold (5 mm diameter, 8 mm height) and kept at 37ºC in at least 37% humidity for 1 hour before and freeze-drying for 2 days. The compressive force of the hydrogel samples was measured by using a universal testing machine (AGS-X; Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min at displacements of 25, 50, and 75%, respectively.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

SPSS was used as the statistical software for data analysis. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc tests. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the measured values were averaged (n=3).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Preparation and Chemical Characterization of Thermosensitive Chitosan/Collagen Hydrogels

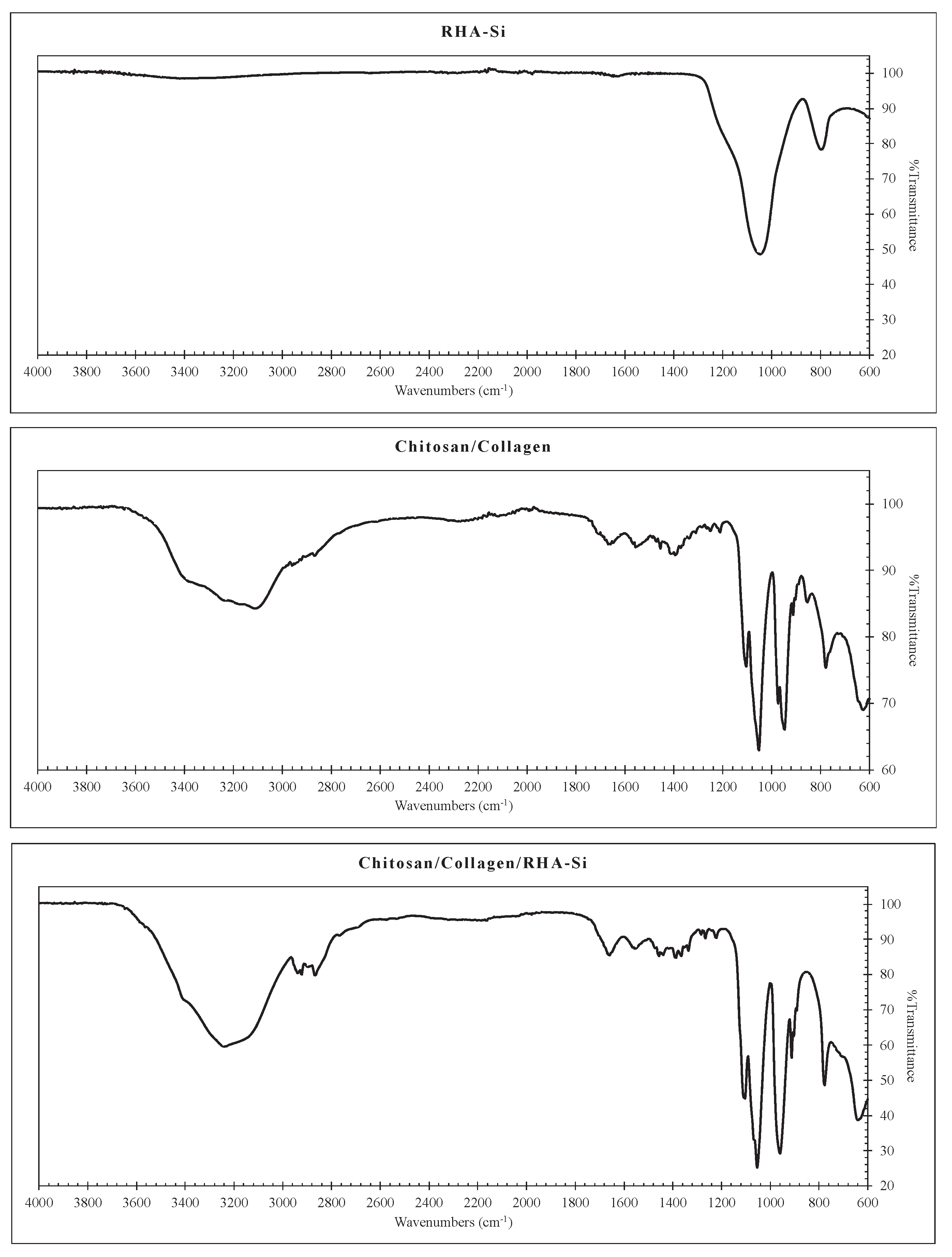

Thermosensitive chitosan/collagen hydrogels were prepared and characterized. The chemical groups of the hydrogels were examined by FTIR, as presented in

Figure 1. It is found that the FTIR spectra of RHA-Si commonly exhibit characteristic peaks due to different vibrational modes of the Si-O and Si-OH bonds. The 3397 cm⁻¹ peak represents the stretching vibration of hydroxyl (-OH) groups, which are present due to surface silanol groups (Si-OH) and adsorbed water on silica. The strong and broad peak at 1045 cm⁻¹ reveals a characteristic of the asymmetric stretching of the Si-O-Si network. The 796 cm⁻¹ peak corresponds to either the symmetric stretching or bending vibrations of Si-O-Si bonds in silica. The FTIR spectra of chitosan/collagen hydrogels reveal distinct vibrational modes reflecting molecular interactions between the two biopolymers. The shoulder peak at 3362 cm⁻¹ corresponds to O-H stretching from hydroxyl groups in chitosan and collagen, enhanced by hydrogen bonding between the polymers. The 3230 and 3101 cm⁻¹ subpeaks represent N-H stretching from amide groups in chitosan and collagen. The 2946 cm⁻¹ peak and 2866 cm⁻¹ peaks correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of CH₂ and CH₃ groups in the chitosan and collagen backbone. Amide-related peaks include 1659 cm⁻¹ (amide I, C=O stretching), 1564 cm⁻¹ (amide II, N-H bending + C-N stretching), and 1301 cm⁻¹ (amide III, C-N stretching + N-H deformation). Saccharide-specific bands appear at 1084 and 1052 cm⁻¹, attributed to C-O-C and C-O stretching in chitosan, while the FTIR peak at 961 cm⁻¹ and 945 cm⁻¹ relate to pyranose ring vibrations in chitosan’s saccharide structure. The minor structural features, such as 779 and 622 cm⁻¹, represent out-of-plane bending and deformation modes. For the FTIR spectra of chitosan/collagen hydrogel filled with RHA-Si, it is noticed that the addition of silica into chitosan/collagen hydrogels does not significantly alter the primary functional groups, as indicated by the similar transmittance at the amide key peaks. This suggests that adding silica into the hydrogel does not represent a chemical interaction [

18,

19]. However, it could be observed that the 945 cm

-1 peak becomes a major peak, replacing the 961 cm

-1 peak by adding silica into the hydrogel. This is because silica physically interacts with chitosan’s glycosidic bonds (C-O-C), suppressing pyranose ring vibrations and reducing the 961 cm

-1 peak [

20]. Silica enhances collagen-silica hydrogen bonding, amplifying collagen-specific vibrations and causing the 945 cm

-1 peak to become apparent. This is consistent with collagen-silica electrostatic stabilization mechanisms observed in hybrid hydrogels [

21]. The effect of silica on hydrogel could also be seen from the shift of the 622 cm⁻¹ peak to 636 cm⁻¹, indicating structural modifications, likely due to interactions between silica and the biopolymer matrix. This peak is associated with out-of-plane C-OH bending (chitosan) and C-C-O deformation (collagen), and its shift suggests that silica may be forming hydrogen bonds or electrostatic interactions with hydroxyl and amide groups, altering the local molecular environment [

22]. Additionally, silica incorporation may influence the hydrogel network’s rigidity, affecting the polymer chain’s vibrational modes. This shift confirms the successful integration of silica into the hydrogel while maintaining the core molecular framework of the chitosan-collagen system.

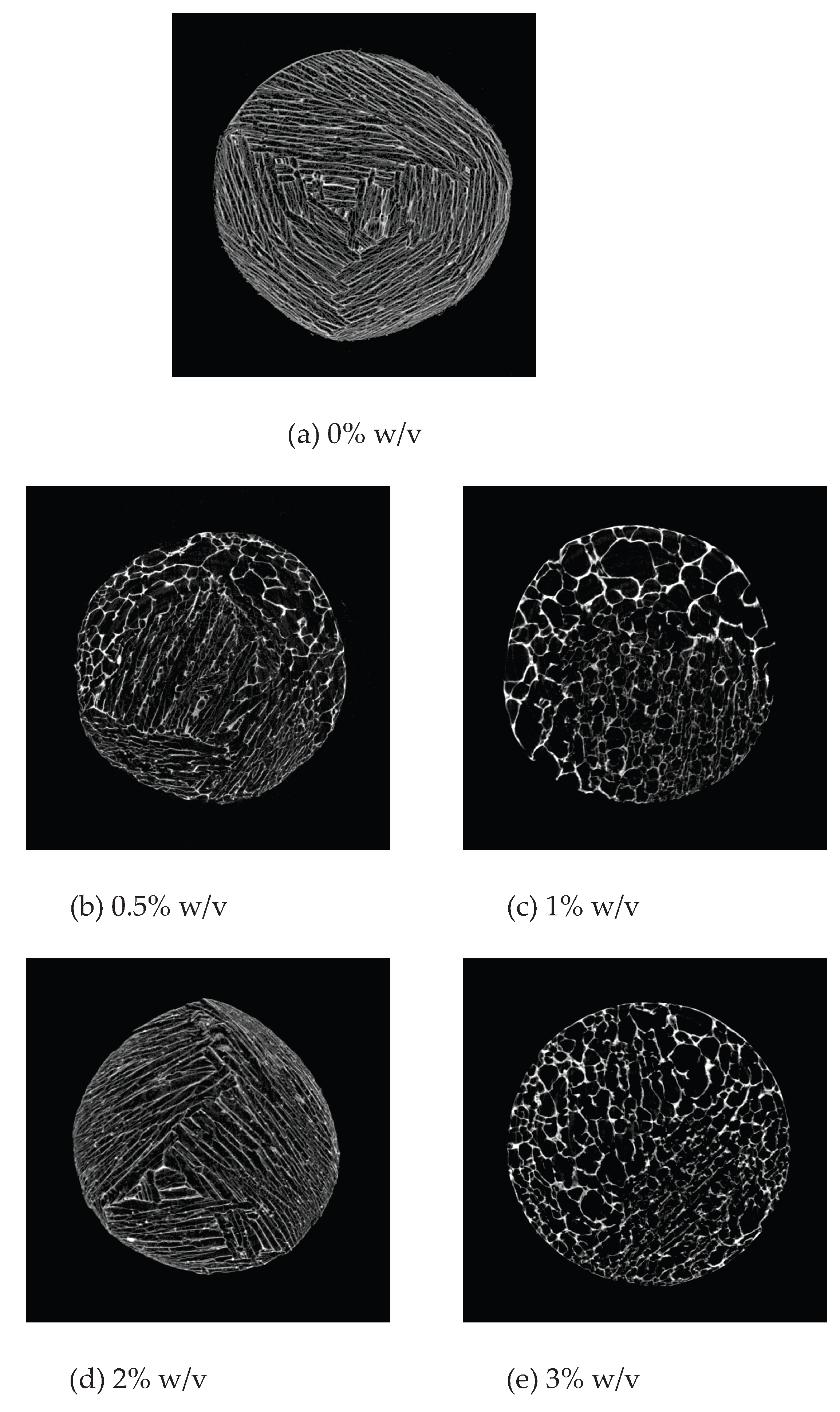

3.2. Morphological and Porosity Analysis of Hydrogels Using Micro-CT

Figure 2 exhibits the cross-section images of the freeze-dried hydrogels captured from image reconstruction of micro-CT analysis. The figure illustrates that incorporating RHA-Si into the chitosan/collagen hydrogel influences its porous structure. At 0% w/v RHA-Si, the freeze-dried hydrogel exhibits predominantly rod-shaped pores, suggesting anisotropic pore formation likely due to the intrinsic alignment of the polymer matrix during fabrication [

23]. During freeze-drying, anisotropic polymer alignment leads to elongated, tubular pores. Interestingly, adding RHA-Si at concentrations of 0.5%, 1.0%, and 3.0% w/v resulted in a noticeable transformation of pore shape from tubular to more spherical pores. This suggests that RHA-Si may act as a structural modifier, promoting spherical pore geometry, isotropic pore formation, possibly by (i) increasing crosslink density via the interaction between silica’s hydroxyl groups with chitosan/collagen, and (ii) limiting polymer mobility through increasing solution viscosity from solid adding [

24,

25].

However, at 2.0% w/v RHA-Si, the pore shape reverted to a tubular morphology, indicating a non-linear effect of RHA-Si concentration on pore structure. This reappearance of tubular pores at an intermediate concentration may reflect a critical threshold where particle-polymer or particle-particle interactions alter the phase separation dynamics or hydrogel freezing behavior. These observations demonstrate that the pore geometry of the chitosan/collagen freeze-dried hydrogels can be finely tuned by adjusting RHA-Si content, which could have important implications for tailoring freeze-dried hydrogel properties such as mechanical strength, fluid transport, and cell infiltration.

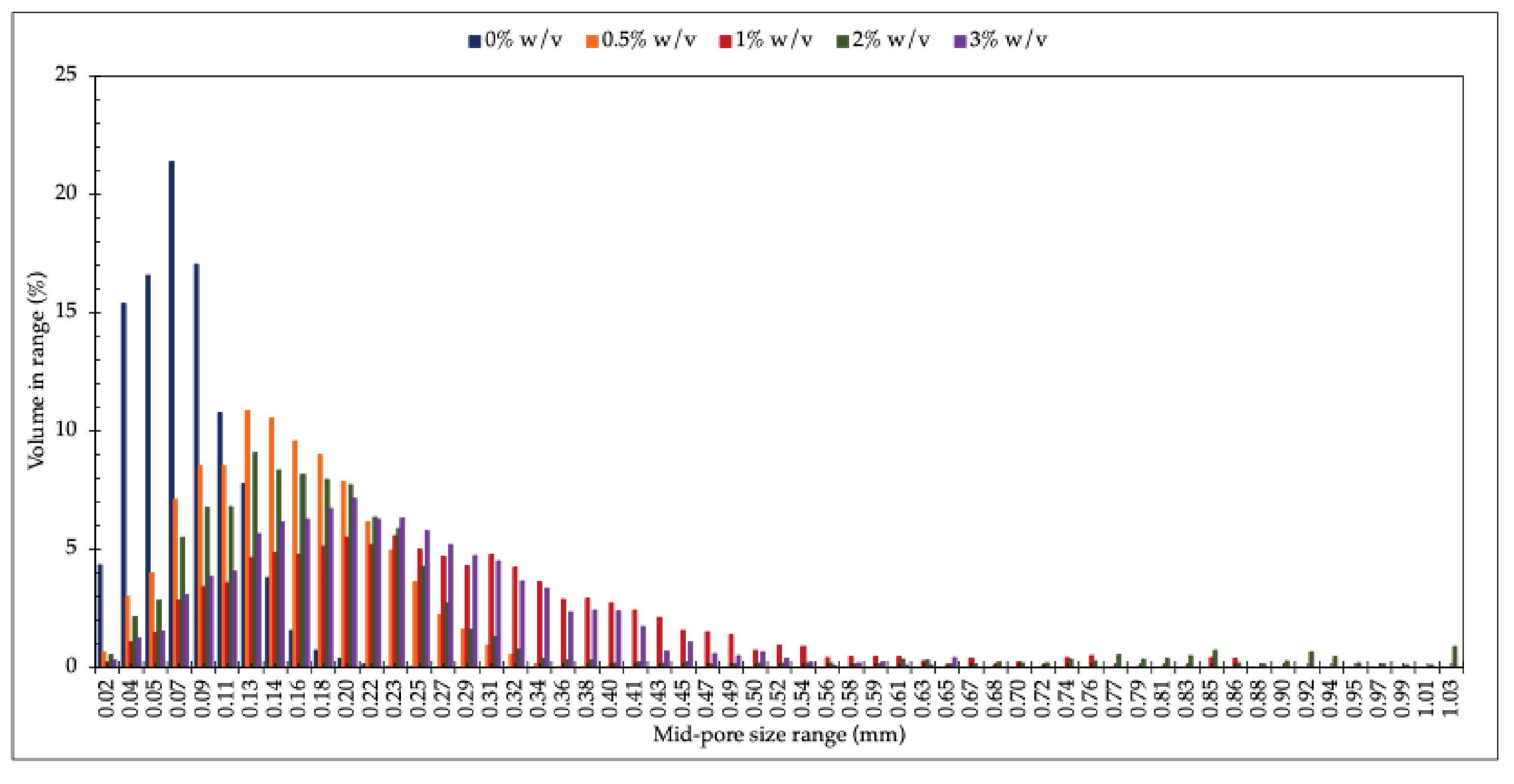

Figure 3 illustrates the pore size and distribution of the freeze-dried hydrogel filled with different RHA-Si concentrations. It is evident that at 0% w/v RHA-Si, the freeze-dried hydrogel possesses the smallest pore size and the most uniformly distributed pores, as shown with the maximum mid-pore size range and standard deviation in

Table 1, respectively. The addition of RHA-Si causes the chitosan/collagen freeze-dried hydrogels to be larger and to have less uniformly distributed pores. Noticeably, the freeze-dried hydrogel filled with RHA-Si concentration of 2% w/v, the pore size decreases and shows the highest variability (the highest SD), indicating a return to more irregular, possibly tubular structures. Interestingly, increasing RHA-Si to 3.0% w/v again produces larger and more uniformly spherical pores. This non-linear trend suggests that RHA-Si acts as a structural modifier, but its effect is concentration-dependent and possibly influenced by dispersion and matrix interaction dynamics, as mentioned previously.

The effect of RHA-Si concentrations on porosity and connectivity of the freeze-dried chitosan/collagen hydrogels is presented in

Table 2. The porosity increases and the connectivity density decreases as RHA-Si concentration increases from 0 to 1.0, indicating a shift from small, well-connected tubular pores to larger, less interconnected spherical pores. Interestingly, at 2.0% RHA-Si, a partial recovery in connectivity density is observed, potentially due to the reformation of tubular pores. At 3.0% RHA-Si, porosity remains high, but connectivity is higher than in the 1% sample. This may reflect well-dispersed but relatively separate pores, possibly spherical. These results highlight the non-linear and concentration-dependent role of RHA-Si in modulating freeze-dried hydrogel microstructure, which could impact mechanical integrity and cellular infiltration.

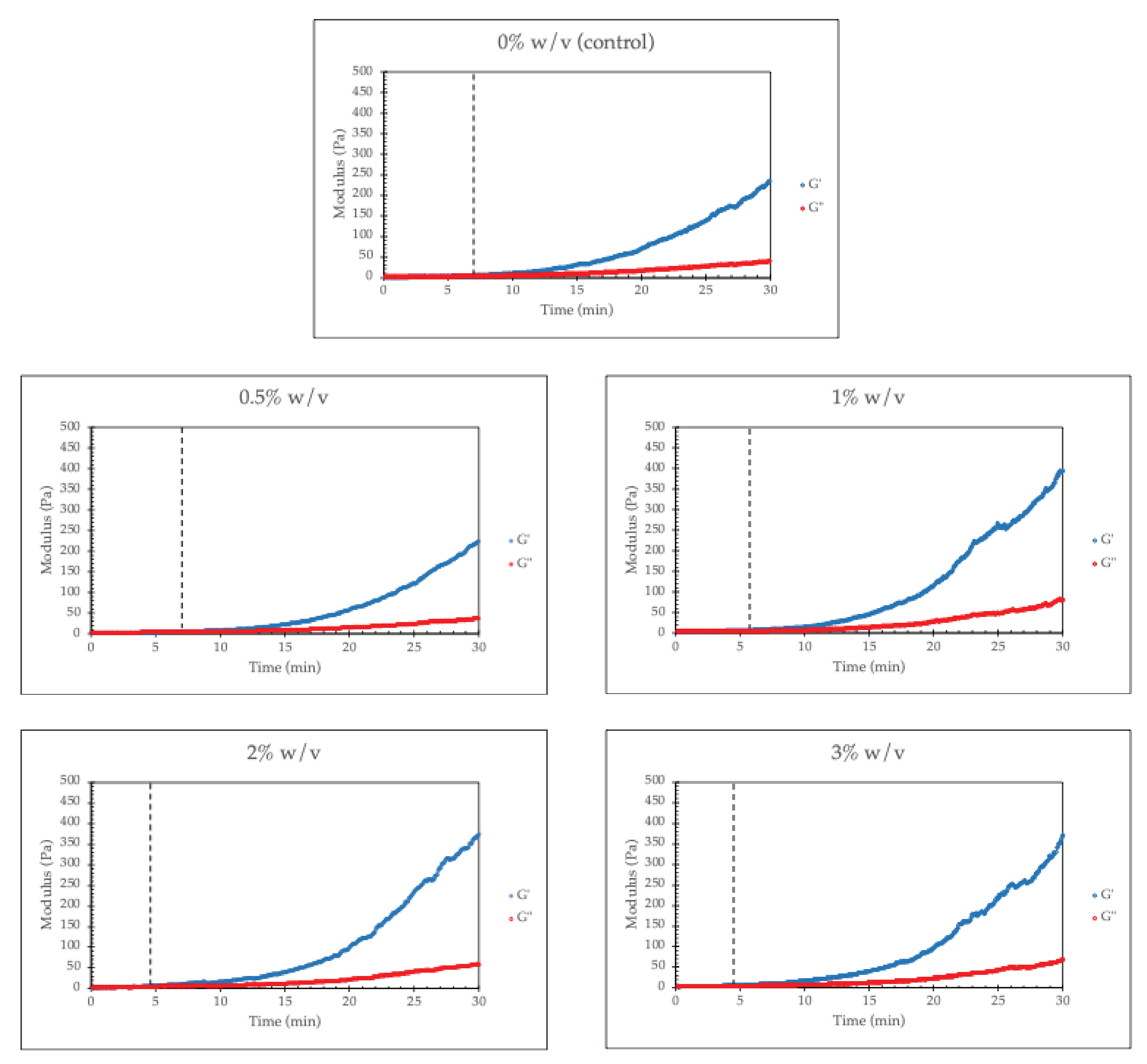

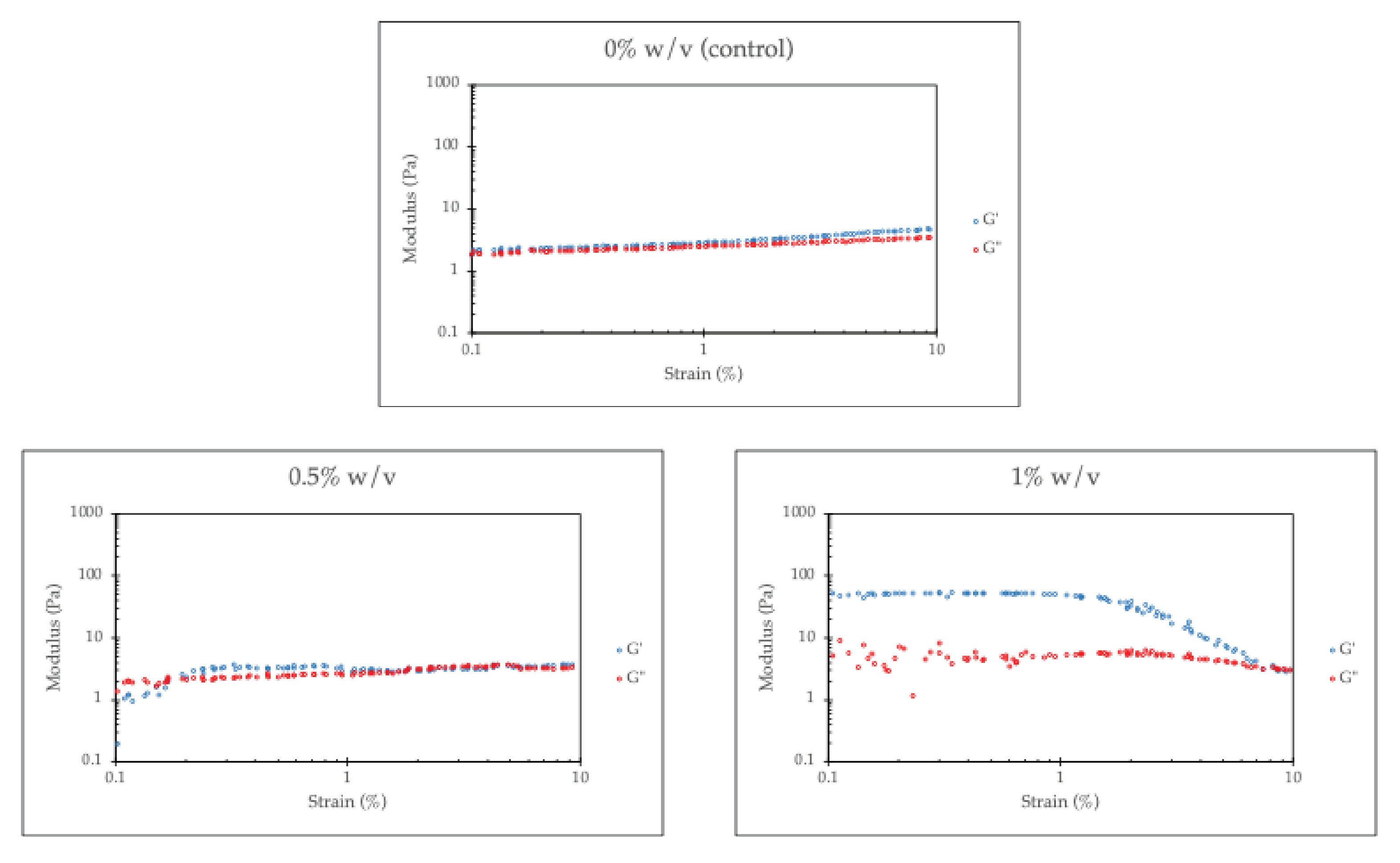

3.3. Rheological Measurements

The rheological behavior of Chitosan/Collagen hydrogel with various concentrations of RHA-Si was investigated. The gelation time of the composite hydrogels was assessed by rheological assays using the time sweep test at 37 °C. The gel point, which is an increase in storage modulus (G′) significantly higher than loss modulus (G″), marks the transition from a liquid state to a solid, gel-like state and is a good indicator of gelation formation. It is utilized to express the gelation time of the hydrogel.

From

Figure 4, the gelation time (time at the dashed line) of the hydrogel decreases with increasing RHA-Si loading. This is due to the crosslink promotion of RHA-Si. As discussed previously, RHA-Si contains silanol, which facilitates interactions with amine groups in chitosan or carboxyl/hydroxyl groups in collagen, promoting faster network stabilization.

Figure 5 presents the G′ and G″ of the hydrogel as a function of strain amplitude. Both the G′ and the G″ of a chitosan/collagen hydrogel without RHA-Si remain nearly constant over a range of strain amplitudes, a well-defined linear viscoelastic region (LVR), indicating a good gel network. It is also found that the G′ is higher than the G″ across the examined strain amplitude range. This behavior can be attributed to the formation of a three-dimensional network due to strong physical interactions between chitosan and collagen associated with a physical crosslinker such as β-glycerophosphate (β-GP). The hydrogel’s ability to retain a higher G′ than G″ throughout strain sweeps demonstrates that the elastic network dominates, with viscous dissipation playing a secondary role.

However, the increasing RHA-Si concentration leads to a higher G′ of the hydrogel, while simultaneously reducing the extent of the LVR. The increase in the storage modulus (G′) of chitosan/collagen hydrogels with higher RHA-Si content can be attributed to the reinforcement effect imparted by the silica particles. Silica, as a rigid inorganic filler, enhances the mechanical strength of soft polymeric hydrogels by forming physical interactions with the surrounding polymer chains. In particular, the silanol groups present on the surface of silica nanoparticles play a critical role in this reinforcement. As mentioned, these silanol groups can form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl, amine, or carboxyl groups of chitosan and collagen, leading to improved interfacial adhesion between the filler and matrix. This enhances stress transfer from the polymer to the filler and restricts the mobility of the polymer chains, thereby increasing the elasticity and G′ of the hydrogel [

26]. As the silica content increases, the network becomes more densely crosslinked.

The results show that the LVR is narrower with higher RHA-Si loading. This behavior is closely related to the Payne effect, which is commonly observed in filled polymers. The Payne effect describes a reduction in storage modulus with increasing strain amplitude, i.e., the structural breakdown in the filler-filler and filler-polymer network [

27].

At higher strains, the physical interactions, especially hydrogen bonding between silanol groups of RHA-Si and polymer chains of chitosan/collagen hydrogel, are disrupted, leading to a decrease in G′. However, it is noticeable that the G″ shows much less sensitivity to strain amplitude, which can be explained by the RHA-Si interaction via physical (non-covalent) bonds. At given strains, these bonds might partially break (reflected in G′ drop), but the polymer chains are still crosslinked or associated, so there’s no significant increase or decrease in energy dissipation.

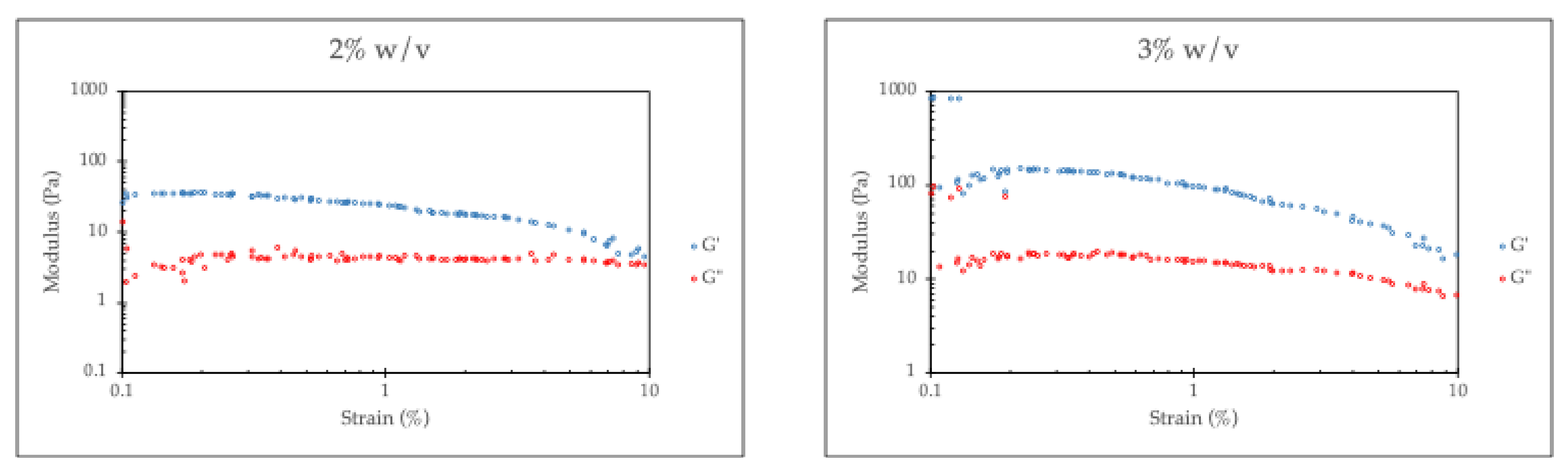

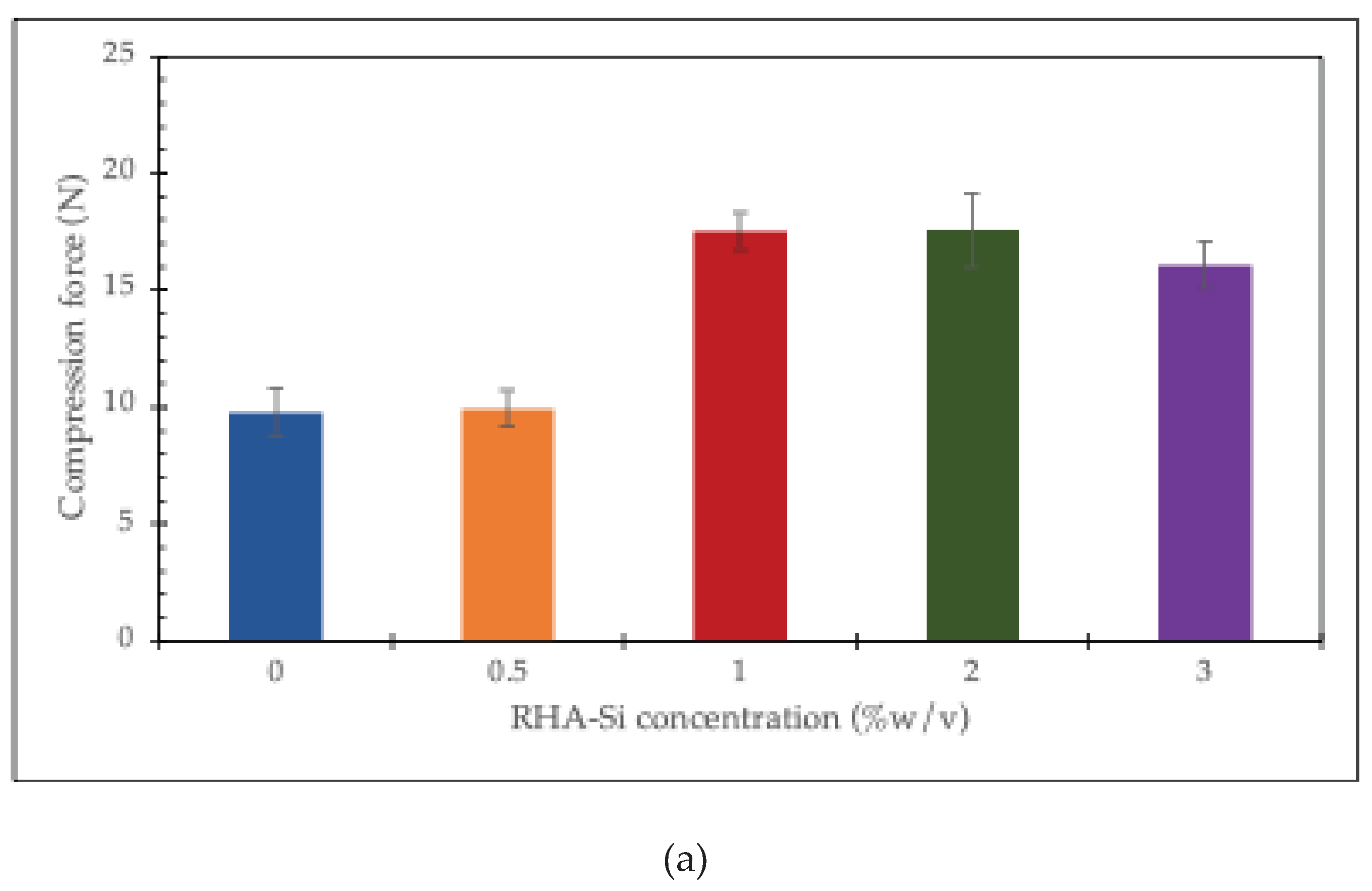

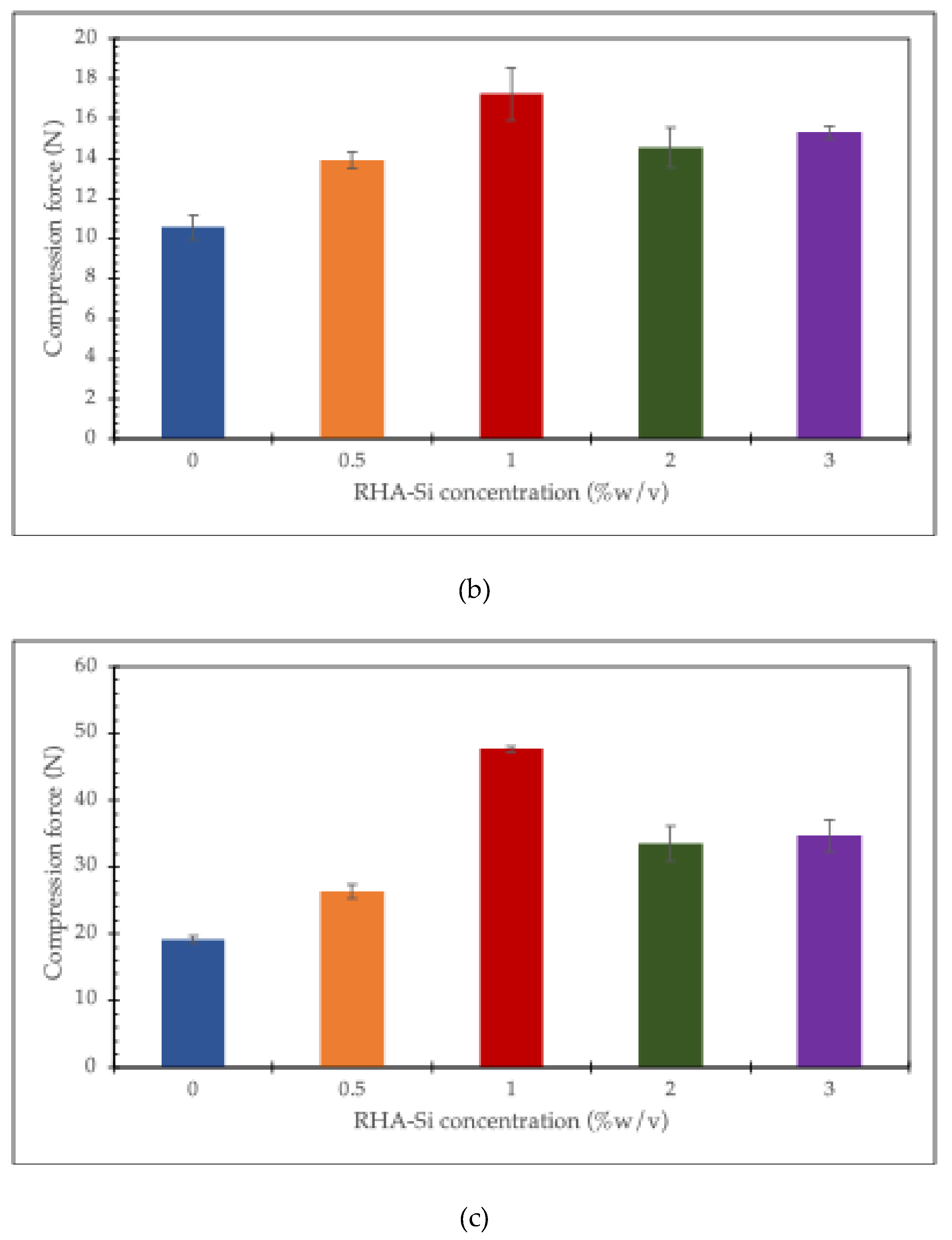

3.4. Mechanical Test

The compression force at a given displacement is utilized to investigate the effect of RHA-Si on the mechanical properties of the chitosan/collagen hydrogel. The results are shown in

Figure 6. It can be seen that the compression force increases with increasing RHA-Si concentrations from 0 to 1% w/v in chitosan/collagen hydrogel, which remains constant at 2 and 3% w/v at a displacement of 25%. However, at higher displacements (50% and 75%), the compression force of hydrogels containing 2 and 3% RHA-Si decreases significantly.

The results show that the compression force of chitosan/collagen hydrogels increases when silica concentration rises from 0 to 1% w/v. This means that a small amount of silica can help strengthen the hydrogel. At 2% and 3% w/v, the compression force remains about the same. This suggests that adding more silica after 1% does not make the hydrogel stronger at a 25% displacement. However, when the hydrogel is compressed more, at 50% and 75% displacement, the samples with 2% and 3% silica show a clear decrease in compression force. This means that high amounts of silica may reduce the flexibility of the hydrogel and make it weaker under large deformation [

28,

29].

4. Conclusions

In this study, thermosensitive chitosan/collagen hydrogels were successfully prepared and reinforced with rice husk ash-derived silica (RHA-Si). The chemical analysis showed that adding RHA-Si did not change the main functional groups of the hydrogel but caused small shifts in the FTIR peaks, indicating physical interactions. The morphology of the freeze-dried hydrogels changed with silica content. RHA-Si helped to form larger and more spherical pores at certain concentrations, but the effect was not linear. Rheological tests showed that silica increased the storage modulus (G′), making the hydrogel stiffer. However, at high strain, the network became weaker due to the Payne effect. The compression test showed that a small amount of silica (1% w/v) improved the strength of the hydrogel at low deformation. But at high deformation, too much silica (2–3% w/v) made the hydrogel less flexible and reduced its strength. Overall, RHA-Si can be used to improve the structure and strength of chitosan/collagen hydrogels, but the amount needs to be optimized for the desired application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., P.N., S.P. and P.W.; methodology, A.P., P.N., S.P. and P.W.; formal analysis, A.P., P.N., S.P. and P.W.; investigation, A.P., P.N., S.P. and P.W.; resources, A.P., S.P. and P.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and P.W.; writing—review and editing, A.P., S.P. and P.W.; project administration, P.W.; funding acquisition, P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Thammasat University Research Fund, Contract No. TUFT 63/2564.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Chanon Somjitkul for his valuable technical support throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Drury, J.L.; Mooney, D.J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: Scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4337–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreifke, M.B.; Ebraheim, N.A.; Jayasuriya, A.C. Investigation of potential injectable polymeric biomaterials for bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101A, 2436–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Chu, C.R.; Payne, K.A.; Marra, K.G. Injectable in situ forming biodegradable chitosan–hyaluronic acid based hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2499–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkmeister, J.A.; Ramshaw, J.A.M.; Glattauer, V.; Hodge, A.J. Biodegradable and injectable cure-on-demand polyurethane scaffolds for regeneration of articular cartilage. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3471–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraguchi, K.; Takehisa, T. Nanocomposite hydrogels: A unique organic–inorganic network structure with extraordinary mechanical, optical, and swelling/de-swelling properties. Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creton, C. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Networks and gels: Soft but dynamic and tough. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 8297–8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.P.; Katsuyama, Y.; Kurokawa, T.; Osada, Y. Double-network hydrogels with extremely high mechanical strength. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Lee, K.J.; Lahann, J. Multifunctional polymer particles with distinct compartments. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 8502–8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Sato, H.; Mie, M.; Kobatake, E. Development of a silica-based double-network hydrogel for high-throughput screening of encapsulated enzymes. Analyst 2009, 134, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Kimura, S.; Wada, M.; Kuga, S. Cellulose–silica nanocomposite aerogels by in situ formation of silica in cellulose gel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2076–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Lin, S.; Zhang, L. Synthetic and viscoelastic behaviors of silica nanoparticle reinforced poly(acrylamide) core–shell nanocomposite hydrogels. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-J.; Wilker, J.J.; Schmidt, G. Robust and adhesive hydrogels from cross-linked poly(ethylene glycol) and silicate for biomedical use. Macromol. Biosci. 2013, 13, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foletto, E.L.; Hoffmann, R.; Hoffmann, M. Conversion of rice hull ash into soluble sodium silicate. Mater. Res. 2006, 9, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, C.; Alcalá, M.D.; Criado, J.M. Preparation of silica from rice husks. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1996, 79, 2012–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuad, M.Y.A.; Ismail, Z.; Ishak, Z.A.M.; Omar, A.K.M. Rice husk ash as fillers in polypropylene: A preliminary study. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 1993, 19, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardena, S.; Ismail, H.; Ishiaku, U.S. A comparison of white rice husk ash and silica as fillers in ethylene–propylene–diene terpolymer vulcanizates. Polym. Int. 2001, 50, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwitthayakool, P.; Meesane, J.; Peampring, C.; Santiwarangkool, K. Flexural strength and dynamic mechanical behavior of rice husk ash silica filled acrylic resin denture base material. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 824, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Barghouthi, M.; Zidan, G.; Obaidat, R.M.; Al-Remawi, M.; Badwan, A. A novel superdisintegrating agent made from physically modified chitosan with silicon dioxide. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2008, 34, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minisha, S.; Sharma, P.; Sahai, R.; Rai, V.K. Impact of SiO₂ nanoparticles on the structure and property of type I collagen in three different forms. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 305, 123520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, X.; Hu, M.; Shi, W. Influence of nanosilica on inner structure and performance of chitosan-based films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 212, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perumal, S.; Nandakumar, A.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Sivanesan, D.; Krishnamurithy, G. Altering the concentration of silica tunes the functional properties of collagen–silica composite scaffolds to suit various clinical requirements. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 52, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamski, R.; Siuta, D. Mechanical, structural, and biological properties of chitosan/hydroxyapatite/silica composites for bone tissue engineering. Molecules 2021, 26, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Ma, Y. Pore architecture and cell viability on freeze-dried 3D recombinant human collagen-peptide (RHC)–chitosan scaffolds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 49, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamski, R.; Siuta, D. Mechanical, structural, and biological properties of chitosan/hydroxyapatite/silica composites for bone tissue engineering. Molecules 2021, 26, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chik, N.; Yaacob, Z.; Ismail, A.F.; Othman, M.H.D. Extraction of silica from rice husk ash and its effect on the properties of the integral membrane. ASM Sci. J. 2022, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, M.; Becerra, N.Y. Silica/protein and silica/polysaccharide interactions and their contributions to the functional properties of derived hybrid wound dressing hydrogels. Int. J. Biomater. 2021, 2021, 6857204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassagnau, P. Payne effect and shear elasticity of silica-filled polymers in concentrated solutions and in molten state. Polymer 2003, 44, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Catargi, B.; Fujii, T.; Hourdet, D.; Marcellan, A. Structure investigation of nanohybrid PDMA/silica hydrogels at rest and under uniaxial deformation. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 5905–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WuLingzi, L.; Xiumei, M.; Chuang, L.; Cheng, L. Effects of silica sol content on the properties of poly(acrylamide)/silica composite hydrogel. Polym. Bull. 2011, 68. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).