1. Introduction

Wound management remains a critical challenge in clinical practice, with various types of wounds requiring tailored approaches for effective healing. Acute wounds, such as surgical incisions and traumatic injuries, typically follow a predictable healing course. In contrast, chronic wounds, including diabetic ulcers, pressure sores, and venous leg ulcers, often exhibit prolonged inflammation and impaired healing, posing significant burdens on patients and healthcare systems [

1,

2]. The wound-healing process is a complex and dynamic sequence of events that involves four overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [

3]. Traditional wound dressings, such as gauze and bandages, primarily serve as protective barriers. However, they often fail to address the complex biological processes of wound healing. Understanding wound healing has led to developing a new generation of bioactive dressings. These dressings are not just physical barriers but active participants in the healing process. They deliver therapeutic agents, maintain a moist wound environment, and promote cellular activity essential for tissue repair [

1,

4].

Furthermore, these dressings may present several forms, including hydrated-state hydrogels, films, and hydrocolloid dressings or solid-state fibers, acrylics, and foams, each tailored to specific wound types and healing stages [

4]. Solid wound dressings offer several advantages over hydrogels and other hydrated materials in wound management. They are typically easier to sterilize and handle and do not require special storage conditions. Due to the low moisture content, they can absorb exudate efficiently, maintaining an optimal wound moisture balance in highly exudative wounds [

5]. Solid-state materials also provide a longer shelf life, are less prone to microbial contamination, and prevent the degradation of unstable bioactive compounds.

Emergent new-generation solid dressings comprise various synthetic and natural polymeric matrices. Synthetic polymers include poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), polyurethane, and polycaprolactone. On the other hand, natural polymers such as alginate, chitosan, and collagen are also frequently explored as wound dressing components [

4,

5]. Some natural polymers possess inherent bioactive properties and offer several advantages over synthetic compounds as they are highly biocompatible and biodegradable, reducing the risk of adverse reactions. Moreover, several natural polymers, such as chitosan and collagen, can be derived from undervalued food industry by-products, potentially making the wound dressing production process more sustainable and eco-friendlier [

6,

7]. Collagen, a primary structural protein in the human extracellular matrix, provides a scaffold that supports cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation, thereby facilitating tissue regeneration [

8]. Several works have mainly presented the potential of marine collagen due to its excellent wound-healing properties and abundant sources [

7,

9,

10]. On the other hand, chitosan has also emerged as a promising polymer for wound dressings, presenting biocompatibility, biodegradability, and antimicrobial activity properties [

6]. Additionally, chitosan could significantly enhance the mechanical robustness of wound dressing materials, ensuring resistance to physical stresses without tearing or losing integrity.

Incorporating bioactive compounds in novel polymeric dressings is crucial for enhancing wound healing outcomes. These bioactive agents, such as antimicrobial peptides, growth factors, and anti-inflammatory molecules, actively participate in the healing process by promoting cell proliferation, reducing infection risks, and modulating the inflammatory response [

4,

5,

11]. Hydroxytyrosol (HT), a phenolic compound usually present in olive oil products and processing sub-products, has garnered significant attention for its potential in wound healing applications. Its distinctive antioxidative properties help to mitigate oxidative stress at the wound site, thereby protecting cells from damage and promoting tissue repair [

12]. HT also exhibits anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities, crucial for reducing inflammation and preventing infections during wound healing [

12,

13]. Several studies have also shown that HT can enhance angiogenesis and collagen synthesis, further accelerating wound closure and improving overall healing outcomes [

13,

14]. These multifaceted benefits make HT a valuable bioactive compound that can be incorporated into advanced wound care products.

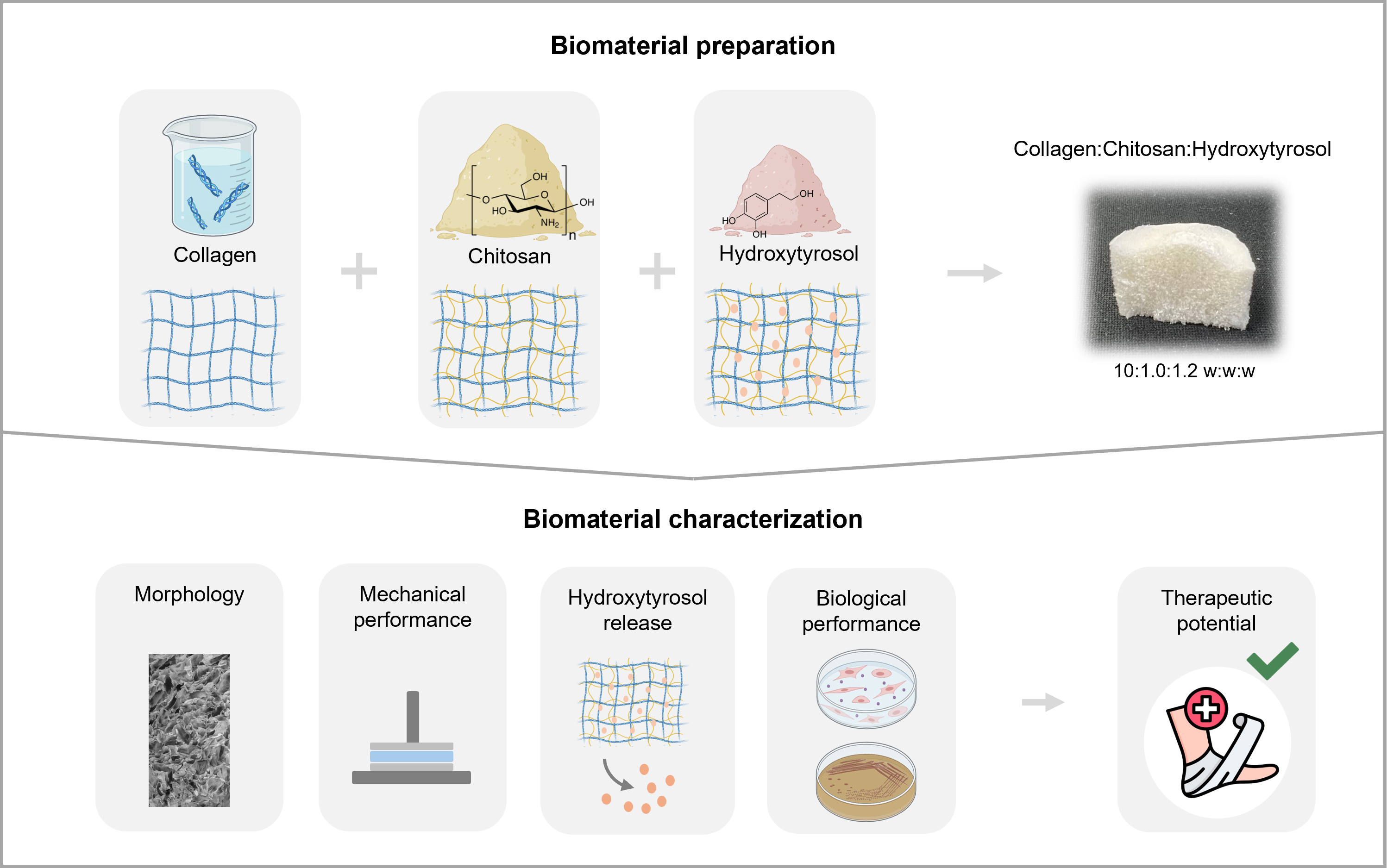

This work explores collagen-chitosan composites’ production and wound-healing potential enhanced with HT for topical applications. The authors intend to combine marine collagen’s structural and regenerative properties with chitosan’s antimicrobial and mechanical robustness, together with the incorporation of HT, to further enhance the therapeutic efficacy of the composites. This study evaluates the morphology, the solid and hydrated-state mechanical properties, and the HT release profile. Bioassays were also conducted to determine the toxicity screening of the skin cells’ contact and assess the compound’s synergic antimicrobial activity against microorganisms recognized as skin commensals and nosocomial pathogens.

3. Results and Discussion

Previously published works describe the production of collagen materials with chitosan and bioactive compounds for biomedical applications [

10,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This article builds on that work and presents a new solid collagen material that leverages the NADES solubility properties of collagen, obtained according to our previous work [

7], together with chitosan, while additionally incorporating a potent antioxidant (HT) barely studied as a biomaterial ingredient for potential biomedical applications. Three different materials composed of collagen (Coll), collagen and chitosan (Coll:Chit), and collagen with chitosan and HT (Coll:Chit:HT) were prepared to understand the influence of incorporating chitosan and HT in the collagen material. Chitosan was incorporated into the collagen extract in a 10:1.0 Coll:Chit w:w ratio, according to several solubilization tests indicating this maximum achievable chitosan incorporation. HT was incorporated according to the MIC obtained in the antimicrobial susceptibility testing performed against

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa (

Table 2). This test was also completed for chitosan to verify that both compounds used and incorporated in the collagen matrix were active antimicrobials against well-recognized skin commensals and nosocomial pathogens [

15,

16].

As expected, chitosan and HT displayed their antibacterial activity against both bacteria. This result agrees with the literature since, unlike collagen, chitosan and HT have a well-established bioactivity against these microorganisms [

6,

12,

13,

33,

34,

35]. HT is known to be unstable in aqueous media. It can degrade over time, especially when exposed to light and oxygen [

36,

37]. Nevertheless, preliminary testing revealed that aged HT solutions (24 h at 37 °C and 60 days at 4 ºC) retained their antimicrobial activities since the MIC remained, at least, the same as a freshly prepared HT solution (Table SM 2).

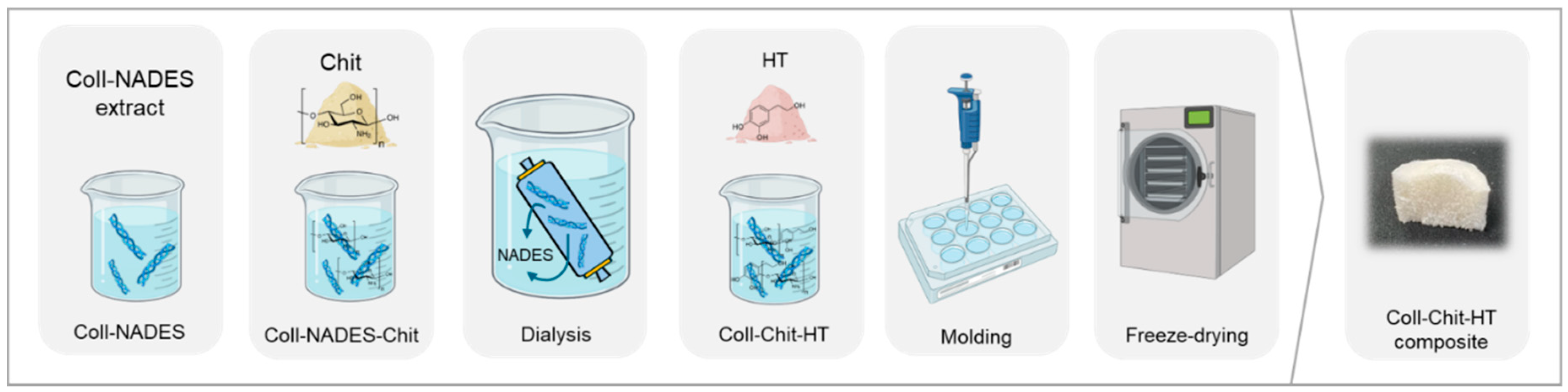

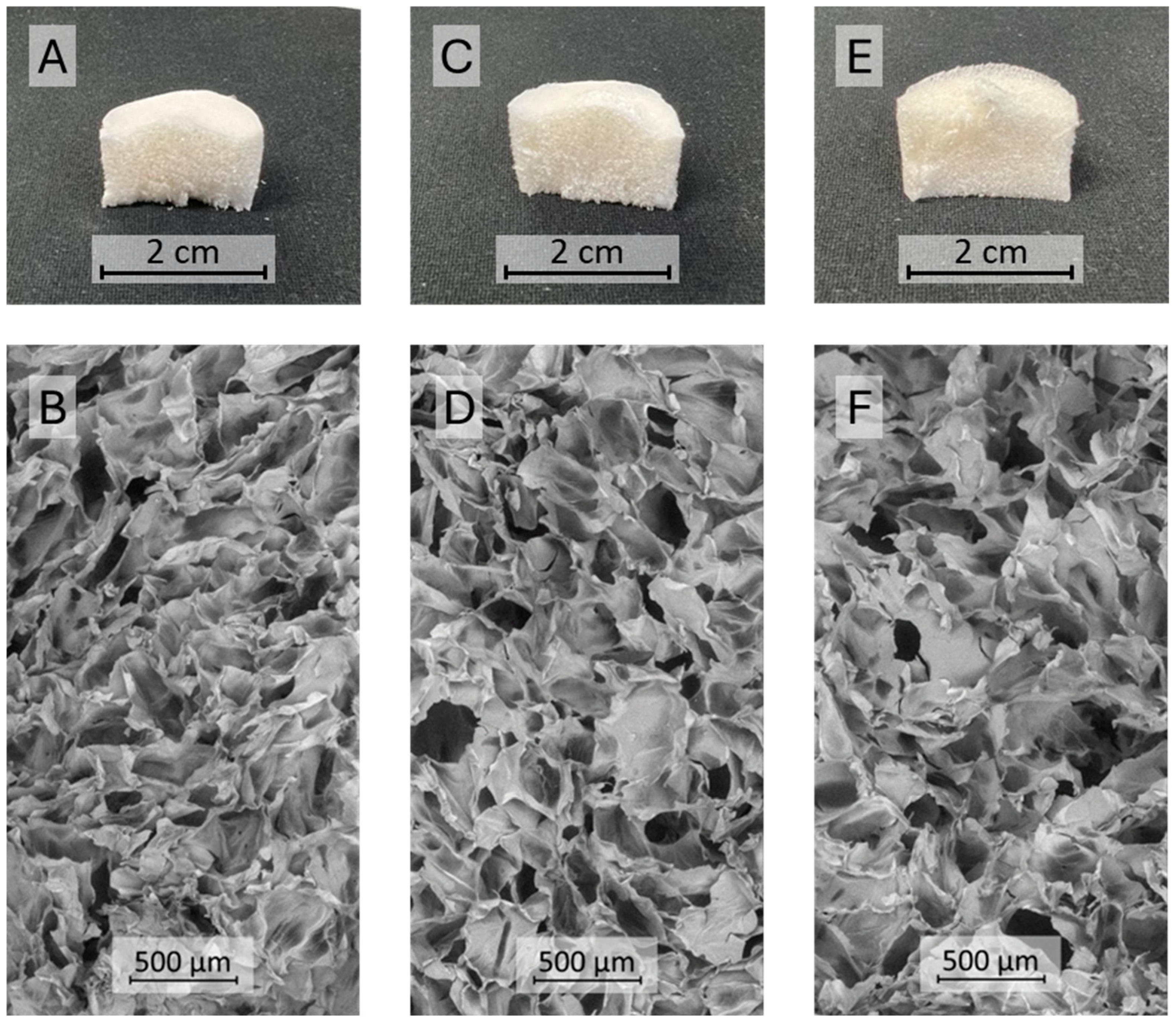

Based on chitosan solubility tests and the highest HT MIC value recorded for both bacteria (1.6 mg/mL), a material composed of collagen, chitosan, and HT was obtained in a 10:1.0:1.2 Coll:Chit:HT w:w:w ratio. The Coll and Coll:Chit materials were obtained by performing the Coll:Chit:HT production process described in the materials and methods section without the HT (Coll:Chit) and the chitosan and HT incorporation steps (Coll). The resulting materials’ macroscale photographs and the corresponding scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs are shown to evaluate the morphology (

Figure 2).

The resulting freeze-dried gels showed a similar monolithic macrostructure with a sponge-like appearance. SEM micrographs revealed that all the materials presented a similar microstructure consisting of large macropores (pore diameter in the range of several μm) with dense areas between pores. Several studies reported that this structure is typical of freeze-dried collagen gel materials [

9,

38]. The similar structure between all produced samples suggests that chitosan and HT did not influence the different collagen materials’ morphology.

Materials for topical application should exhibit acceptable mechanical characteristics and must be easy to apply [

39]. So, mechanical robustness and malleability are important attributes of topical solid dressings for biomedical applications. These features ensure that dressings provide consistent protection against wounds’ external contaminants and maintain their structural integrity during handling [

40,

41]. In this sense, several techniques were applied to determine relevant features that characterize the samples. First, a puncture test was performed to determine the material’s strength to be punctured by a cylindrical probe at a constant speed and the distance at the breaking point. This distance is measured as the length from when the probe contacts the material until it breaks [

42]. The results of the textural analysis of the solid materials are presented in

Table 3.

The analyzed materials showed values of burst strength in the range of 13.9 N to 19.7 N. The solid sample only composed of collagen presented a lower burst strength value, whereas samples with chitosan ruptured at higher force values. Statistical analysis revealed that burst strength value differences are significant between the Coll sample and materials with chitosan. On the other hand, the difference between Coll:Chit and Coll:Chit:HT is not significant. These results suggest incorporating chitosan in the collagen material improved the sample’s mechanical resistance. The material with HT recorded a lower burst strength value than the Coll:Chit sample, which could suggest a plasticizing effect of this compound. However, this difference is not significant, indicating that HT’s presence showed no evident mechanical impact. These results agree with the literature, where several published works demonstrated the positive effect of chitosan in improving the mechanical robustness of collagen materials [

43,

44]. Nonetheless, a straightforward comparison is not easy as the tests implemented are not standardized, and a direct comparison cannot be established. Regarding the distance at burst, a larger distance to achieve the material burst suggests a higher elastic material, whereas smaller distances suggest a more brittle behavior [

45]. However, the texturometer analysis showed similar results between samples with no significant differences, suggesting that chitosan and HT did not contribute to a different elastic behavior of the materials. Overall, the results revealed a higher robustness of materials prepared with chitosan, with the same elastic behavior as the sample only composed of collagen.

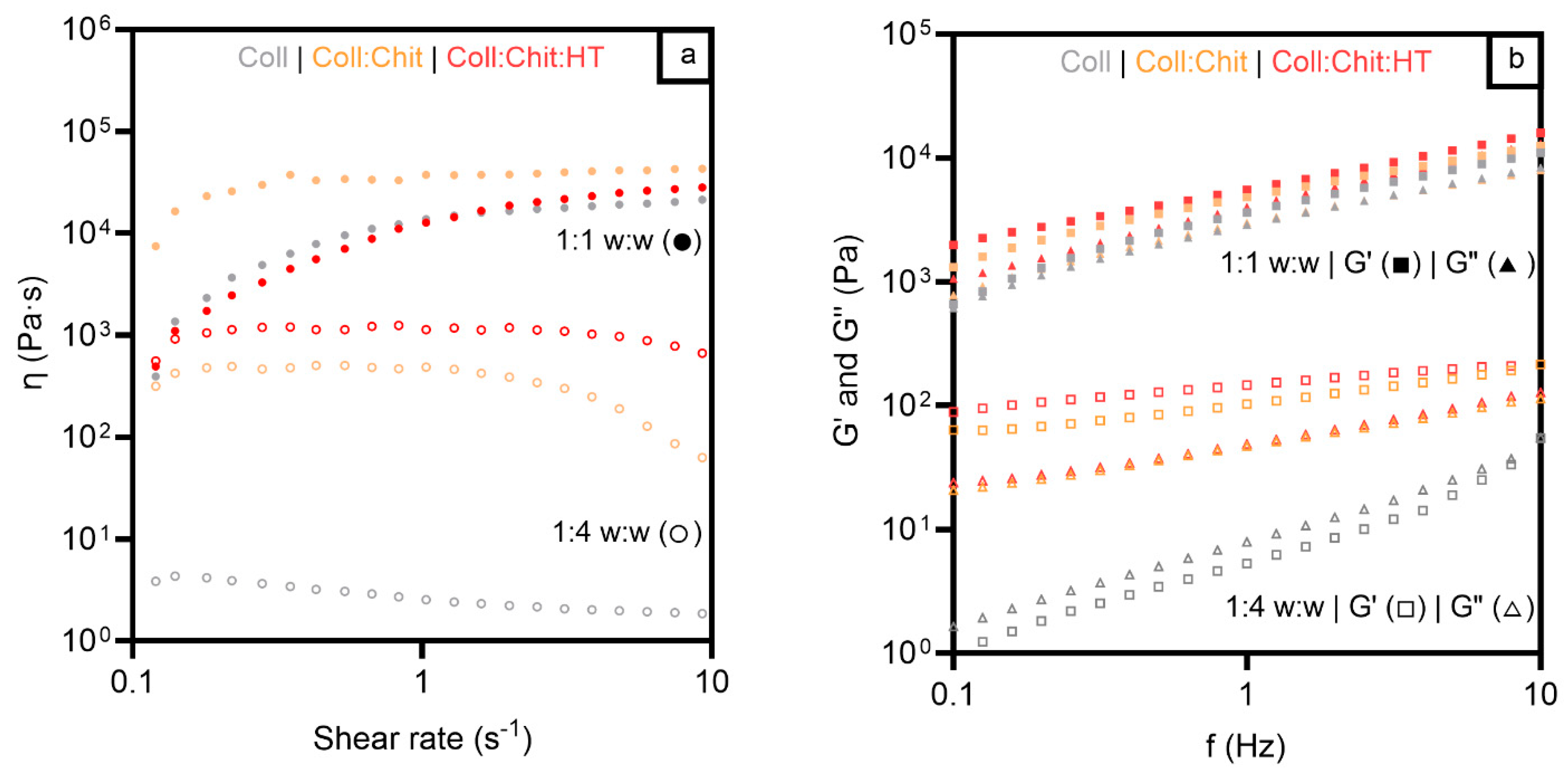

Evaluating the mechanical properties of solid-state materials for topical applications provides important information, particularly for handling dry material. Nonetheless, topical applications, particularly in wound management, may lead to exudate absorption, dramatically changing the material’s mechanical behavior from dry to hydrated. So, the viscosity, viscoelastic behavior, and adhesiveness of the hydrated materials were performed. The materials were characterized in two different mass:solvent proportions (1:1 w:w and 1:4 w:w) to mimic different fluid absorptions in two different wound fluid-draining conditions, from moderate (1:1 w:w) to copious (1:4 w:w) wound exudate volumes, after contact with the wounded skin area [

46,

47].

Figure 3a presents the viscosity results of the three materials in the two hydrated states studied. As expected, all the samples revealed a higher viscosity in the 1:1 w:w condition due to the lower liquid content of the materials. Viscosity behavior as a function of shear rate showed similar profiles for all samples in a 1:1 w:w ratio, with viscosity increasing from 0.1 s

-1 to 1 s

-1 and remaining constant between 1 s

-1 and 10 s

-1. The Coll:Chit sample presented higher viscosities at a lower shear rate than Coll and Coll:Chit:HT samples but tended to the same values at a higher shear rate (20

4 - 50

4 Pa·s at 10 s

-1). On the other hand, the results of the tested samples under a 1:4 w:w ratio showed different viscosity profiles between samples with and without chitosan during all the tested shear rates. Samples containing chitosan exhibited viscosities at least two orders of magnitude higher than those composed solely of collagen. These results suggest that chitosan influenced the internal structure of the collagen materials, unlike HT, which did not change the materials’ viscosity in any of the tested conditions.

To further evaluate the mechanical properties of the prepared materials, the viscoelastic properties of the different hydrated materials were studied and are presented in

Figure 3b.

Concerning the oscillation frequency test, all the samples exhibited predominantly elastic behavior at a higher mass:solvent ratio, evident from the greater magnitude of the elastic module (G′) compared to that of the viscous module (G″). This means that the structure of the gels remained intact through the entire range of frequencies, confirming that all the hydrated materials present a strong network and a solid-like behavior (G′ > G″) [

43]. For the characterization under a lower mass:solvent ratio, all samples presented lower values of the complex shear modulus. However, the samples containing chitosan (Coll: Chit and Coll:Chit:HT) presented a solid-like behavior. In contrast, a transition to liquid-like behavior is observed in the collagen sample since G″ became higher than G′ at higher hydrated treatment. These results agree with the purpose of chitosan incorporation in conferring higher robustness to collagen materials. Viscosity and viscoelastic assessment revealed that the presence of this polymer is required to maintain higher viscosity and preserve a gel structure even in increased water absorption conditions. These rheology test results also suggested an approximated shear-thickening behavior of all materials since the materials’ viscosity increased with the applied stress [

48]. This behavior indicates that the collagen materials could maintain the structural integrity in a wound bed under some stress and provide consistent coverage and protection, as previously described in the literature [

49].

Another important aspect of screening analysis of the material’s potential for wound healing applications concerns its adhesiveness. Materials must be self-supported on the wound, otherwise, there is a need for an additional support dressing. On the other hand, dressings must also be easy to remove, avoiding traumatic and painful dressing removal for the patient, compromising wound healing [

4,

5]. Therefore, a tack and pull-away test was carried out, and the results are shown in

Table 4. This assessment enables the evaluation of a sample’s tackiness and adhesive strength by measuring the peak normal force and area under the force-time curve (with a larger area indicating a stronger adhesive) as two parallel plates are pulled apart [

50]. Tackiness in the context of material behavior is associated with stickiness and may result from adhesive forces between two materials in contact [

51,

52].

As expected, the results revealed that samples with lower water content display more prominent stickiness and adhesive strength with values of area under the force-time curve and absolute normal peak force up to 30 N·s and 15 N, respectively. However, the significant decrease in the sample’s stickiness in the 1:4 w:w treatment could be an interesting achievement. These results indicate that a reduction of material adhesiveness occurs at higher water absorption content, which could facilitate its removal painlessly for the patient. On the other hand, each treatment revealed similar results between samples, with slight differences that were not significant. These results suggest incorporating this chitosan and HT content did not significantly influence the collagen material’s stickiness.

In this study, HT was incorporated into the collagen-chitosan matrix, expecting that the HT release into the wound environment would boost the bioactive properties of the dressing material.

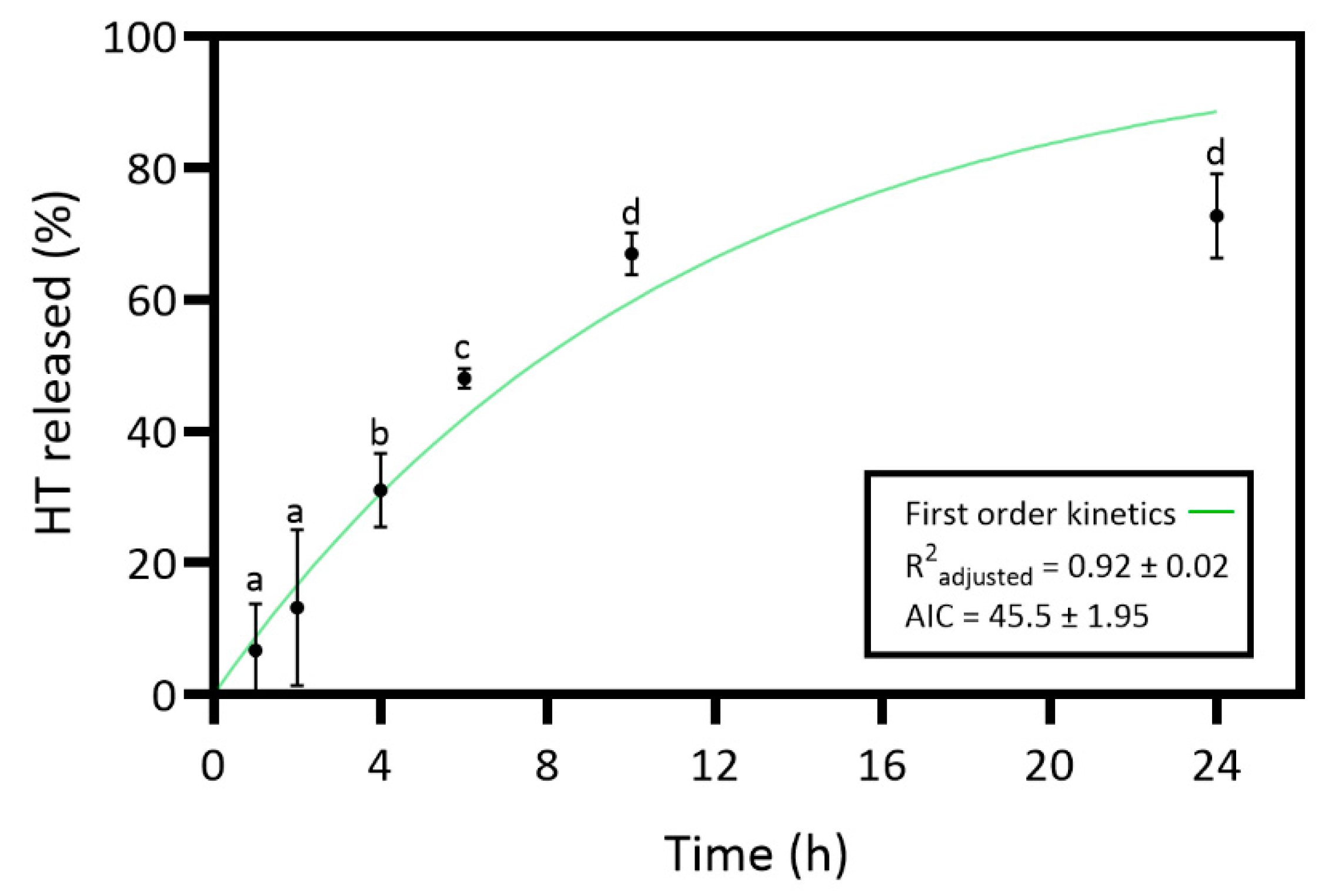

In vitro release studies evaluated the HT release from the collagen-chitosan material over 24 hours. The study aimed to understand the kinetic release profile of HT, and the results are presented in

Figure 4.

Results of HT release revealed an increasing release profile over time and a maximum release percentage (72.7%) at 24 h. However, the slight differences between the 24 h and 10 h time points are not statistically significant. So, the maximum HT release percentage would have already been at 10 h. The HT

in vitro release was curve-fitted to zero-order (Eq. 2), first-order (Eq. 3), Higuchi (Eq. 4), and Korsmeyer-Peppas model (Eq. 5) to understand the release kinetics [

18,

53]. Controlled-release dosage forms are crucial for effective wound healing treatment, requiring an understanding of specific mass transport mechanisms for predicting quantitative kinetics and

in vivo behavior. The release of polymer matrix content can occur by various mechanisms such as diffusion, erosion, and dissolution [

53]. Table SM 1 presents the results of all tested models. The first-order model revealed an R

2 adjusted of 0.92 ± 0.02 and the lowest AIC value of 45.5 ± 1.95. Thus, the release kinetics results suggest that the HT dissolution profile from the hydrated collagen-chitosan matrix is concentration-dependent [

53].

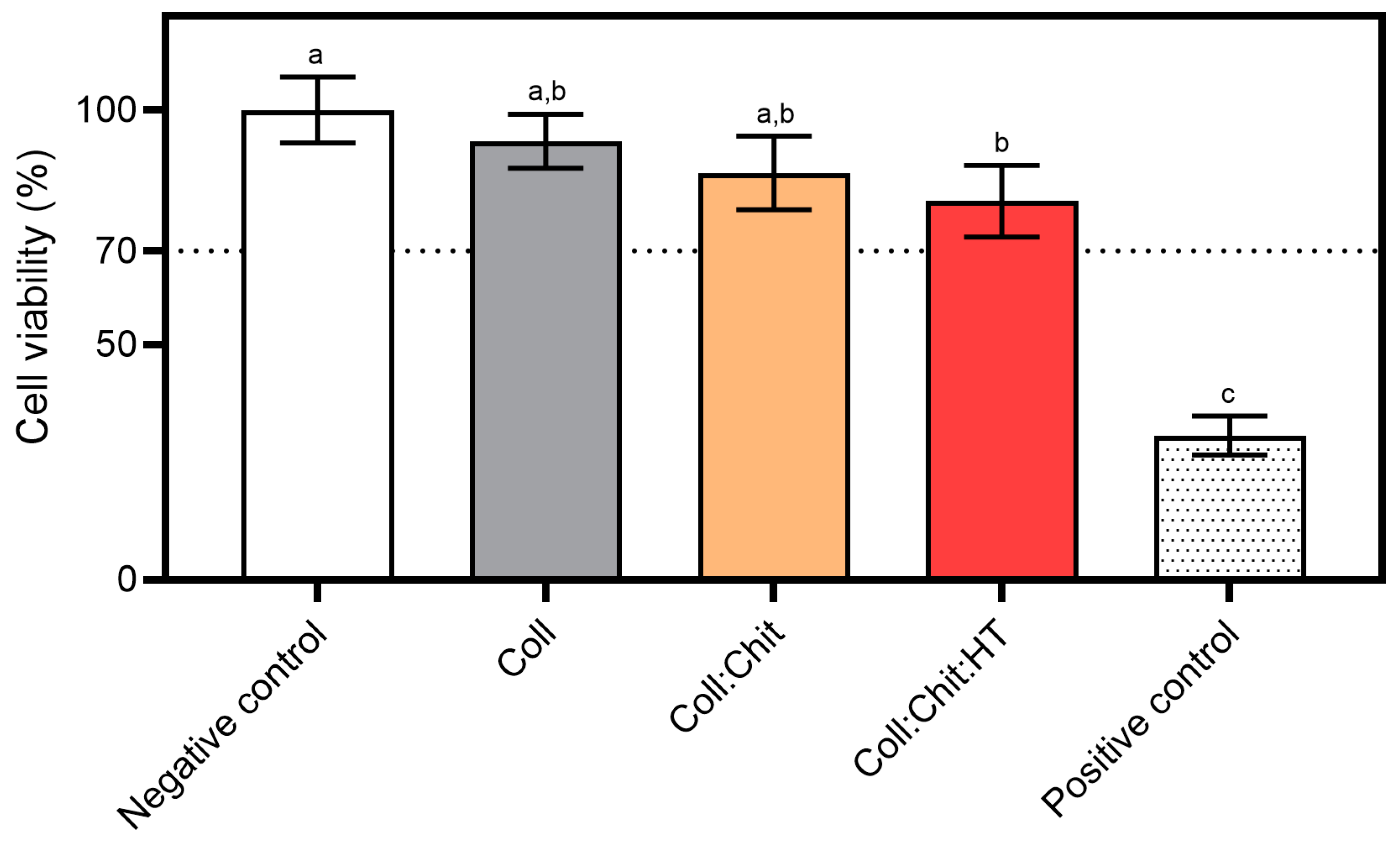

The present work aimed to produce an innovative material for potential biomedical applications involving direct contact with skin cells. The cytotoxicity of the produced samples on a mouse fibroblast cell line was assessed to screen the biocompatible safety of the produced materials for potential wound healing applications.

Figure 5 presents the ISO 10993-5 direct contact methodology results, which involved placing the material in direct contact with cultured cells. This method simulates real-life interactions between the material and skin cells, allowing for the identification of potential toxic effects from the material or its leachables and predicting biocompatibility.

All tested materials present similar cell viability percentages. However, statistical analysis revealed significant differences in cell viability percentages between the negative control (non-treated cells) and the Coll:Chit:HT sample. This is the only sample containing HT, suggesting that the release of this compound could contribute to the significant decrease in cell viability. However, none of the tested samples, including the Coll:Chit:HT sample, exhibited cell viability percentages below the potential cytotoxic effect threshold defined by ISO standard (70%). In this work, the HT concentration incorporated in the material was based on the MIC value of this compound against both bacterial targets selected. However, future works could directly investigate HT cytotoxicity by measuring the half-effective and inhibition concentrations (EC50 and IC50, respectively) if direct information regarding the cytotoxicity of HT is required.

After the materials were found to be non-cytotoxic, their antimicrobial activity was evaluated against

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa. To determine the produced materials’ antimicrobial activity and assess the impact of incorporating chitosan and HT in the collagen matrix, the absorption method outlined in ISO 20743:2013 was performed. This method evaluates the microorganism’s reduction on the material’s surface by measuring the number of viable microorganisms after a specified contact period. It is particularly suitable for assessing the antimicrobial activity of materials intended for wound healing applications by simulating the material’s direct contact with the wound, potentially exposed to various pathogens, and due to its comprehensive and standardized approach. ISO 20743:2013 specifies

K. pneumoniae as the surrogate gram-negative bacterial target to be used in the assay instead of

P. aeruginosa. The scope of this standard is to assess textile antimicrobial efficacy, and the authors agree that

P. aeruginosa is more relevant and adequate representative of gram-negative skin commensals and nosocomial pathogens.

Table 5 shows the antimicrobial activity values according to the absorption method of ISO 20743:2013 and its corresponding efficacy.

Regarding

S. aureus, the determination of antibacterial activity showed the efficacy of all tested materials. Even the sample composed only of collagen presented significant activity. On the other hand, Coll:Chit and Coll:Chit:HT presented strong antibacterial activity against

S. aureus. Regarding

P. aeruginosa, the Coll sample activity value was insufficient to be considered effective. In addition, although both samples containing chitosan revealed efficacy against

P. aeruginosa, only Coll:Chit:HT showed a strong efficacy. These results indicate that the antibacterial activity of collagen materials was improved with chitosan incorporation. Also, the higher efficacy against

P. aeruginosa demonstrates that not only chitosan but also incorporating HT enhances the antibacterial activity of collagen materials. These results agree with the literature’s reported works and the MIC values presented in

Table 2, where these compounds showed antibacterial activity against

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa [

33,

34,

35]. As previously discussed, some HT degradation can occur in the wound-healing fluid environment. However, the antimicrobial evaluation of aged HT solutions (up to 60 days; Table SM 2) suggests that materials incorporated with this compound might maintain their activity against representative skin commensals and nosocomial pathogens and remain effective over time.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Miguel P. Batista: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Margarida Pimenta: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Naiara Fernández: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Ana Rita C. Duarte: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Maria do Rosário Bronze: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision. Joana Marto: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Resources. Frédéric B. Gaspar: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the collagen (Coll)-chitosan (Chit)-hydroxytyrosol (HT) biomaterials production process.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the collagen (Coll)-chitosan (Chit)-hydroxytyrosol (HT) biomaterials production process.

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional photographs (A, C, E) and SEM micrographs (B, D, F) at 100x magnification of the different materials produced with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT): Coll (A, B), Coll:Chit (C, D), and Coll:Chit:HT (E, F).

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional photographs (A, C, E) and SEM micrographs (B, D, F) at 100x magnification of the different materials produced with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT): Coll (A, B), Coll:Chit (C, D), and Coll:Chit:HT (E, F).

Figure 3.

Viscosity vs shear (a) and frequency sweep test (b) for all materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT) in two different mass:solvent (w:w) hydrated states: 1:1 w:w and 1:4 w:w.

Figure 3.

Viscosity vs shear (a) and frequency sweep test (b) for all materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT) in two different mass:solvent (w:w) hydrated states: 1:1 w:w and 1:4 w:w.

Figure 4.

Release profile and corresponding first-order model of hydroxytyrosol (HT) from the collagen (Coll)-chitosan (Chit)-HT biomaterial prepared. Statistically significant differences comparing all time points are indicated by different letters. (Mean ± SD, n=4).

Figure 4.

Release profile and corresponding first-order model of hydroxytyrosol (HT) from the collagen (Coll)-chitosan (Chit)-HT biomaterial prepared. Statistically significant differences comparing all time points are indicated by different letters. (Mean ± SD, n=4).

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity assay using the MTS reagent: materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT) were incubated with NCTC clone 929 cell line for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere (mean ± SD, n = 3). A 10% (v/v) solution of DMSO in cell culture media was used as a positive cytotoxic control. Samples have a cytotoxic potential if viability is reduced to < 70% of the negative control (untreated cells). Statistically significant differences comparing all conditions are indicated by different letters.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity assay using the MTS reagent: materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT) were incubated with NCTC clone 929 cell line for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere (mean ± SD, n = 3). A 10% (v/v) solution of DMSO in cell culture media was used as a positive cytotoxic control. Samples have a cytotoxic potential if viability is reduced to < 70% of the negative control (untreated cells). Statistically significant differences comparing all conditions are indicated by different letters.

Table 1.

Compounds, dissolving agents, and respective highest tested concentrations in the antimicrobial susceptibility testing assays. ddH2O: sterilized double distilled water.

Table 1.

Compounds, dissolving agents, and respective highest tested concentrations in the antimicrobial susceptibility testing assays. ddH2O: sterilized double distilled water.

| Compounds |

Dissolving Agent |

Highest Tested Concentration |

| Chitosan |

HCl 0.1 M |

10 mg/mL |

| Hydroxytyrosol |

ddH2O |

20 mg/mL |

| HCl |

ddH2O |

50 mM |

| Xylitol |

ddH2O |

300 mg/mL |

| Citric acid |

ddH2O |

100 mg/mL |

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing assays against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 (WDCM 00193) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (WDCM 00025) of chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT). Median values of MICs (mg/mL) are presented in this table, while replicate values are available in supplementary materials (Table SM 2).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing assays against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 (WDCM 00193) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (WDCM 00025) of chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT). Median values of MICs (mg/mL) are presented in this table, while replicate values are available in supplementary materials (Table SM 2).

| Tested Compounds |

MICMedian (mg/mL) |

|

S. aureus ATCC 6538 |

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

| Chit |

0.16 |

0.31 |

| HT |

0.39 |

1.56 |

Table 3.

Textural analysis of the solid materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT). Statistically significant differences comparing all samples in each parameter are indicated by different letters.

Table 3.

Textural analysis of the solid materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT). Statistically significant differences comparing all samples in each parameter are indicated by different letters.

| Samples |

Burst Strength (N) |

Distance at Burst (mm) |

| Coll |

13.9 ± 1.82a

|

53.0 ± 0.40a

|

| Coll:Chit |

19.7 ± 3.57b

|

53.5 ± 0.20a

|

| Coll:Chit:HT |

17.1 ± 0.89b

|

53.5 ± 0.18a

|

Table 4.

Adhesive properties for all materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT) in two different mass:solvent hydrated states: 1:1 w:w and 1:4 w:w. Within each evaluated parameter (area under the force-time curve and peak of normal force), statistically significant differences comparing all samples and hydrated states are indicated by different letters.

Table 4.

Adhesive properties for all materials prepared with collagen (Coll), chitosan (Chit), and hydroxytyrosol (HT) in two different mass:solvent hydrated states: 1:1 w:w and 1:4 w:w. Within each evaluated parameter (area under the force-time curve and peak of normal force), statistically significant differences comparing all samples and hydrated states are indicated by different letters.

| |

Area Under Force-Time Curve (N·s) |

Peak of Normal Force (N) |

| |

1:1 w:w |

1:4 w:w |

1:1 w:w |

1:4 w:w |

| Coll |

27.9 ± 2.26a

|

1.44 ± 0.54b

|

-15.4 ± 1.30a

|

-0.12 ± 0.07b

|

| Coll:Chit |

24.4 ± 1.76a

|

1.18 ± 0.54b

|

-12.4 ± 2.01a

|

-0.27 ± 0.13b

|

| Coll:Chit:HT |

25.1 ± 1.53a

|

1.24 ± 0.50b

|

-12.5 ± 1.87a

|

-0.22 ± 0.08b

|

Table 5.

Antimicrobial activity values and corresponding efficacy of the tested materials against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 (WDCM 00193) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (WDCM 00025) from contact with samples at a 2 g/mL concentration during 24 h at 37 °C. Efficacy of antibacterial activity: strong (for antibacterial activity value ≥ 3); significant (for 2 ≤ antibacterial activity value < 3); negligible (for < 2 antibacterial activity value).

Table 5.

Antimicrobial activity values and corresponding efficacy of the tested materials against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 (WDCM 00193) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (WDCM 00025) from contact with samples at a 2 g/mL concentration during 24 h at 37 °C. Efficacy of antibacterial activity: strong (for antibacterial activity value ≥ 3); significant (for 2 ≤ antibacterial activity value < 3); negligible (for < 2 antibacterial activity value).

| Strain |

Sample |

Antibacterial Activity Value |

Efficacy of Antibacterial Activity |

|

S. aureus ATCC 6538 |

Coll |

2.1 ± 0.3 |

Significant |

| Coll:Chit |

6.9 ± 0.1 |

Strong |

| Coll:Chit:HT |

7.1 ± 0.1 |

Strong |

|

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

Coll |

1.7 ± 0.2 |

Negligible |

| Coll:Chit |

2.6 ± 0.2 |

Significant |

| Coll:Chit:HT |

5.8 ± 0.5 |

Strong |