Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

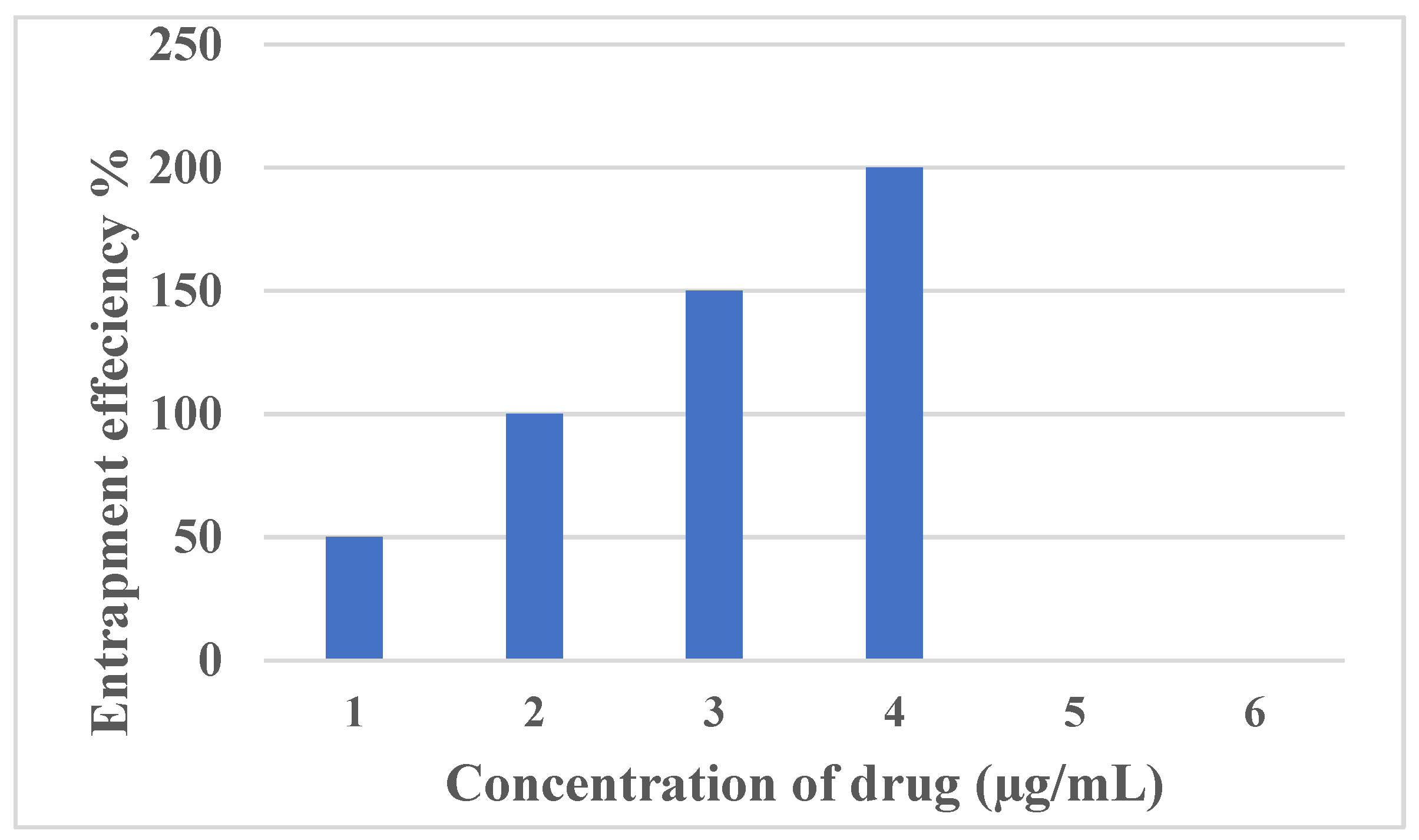

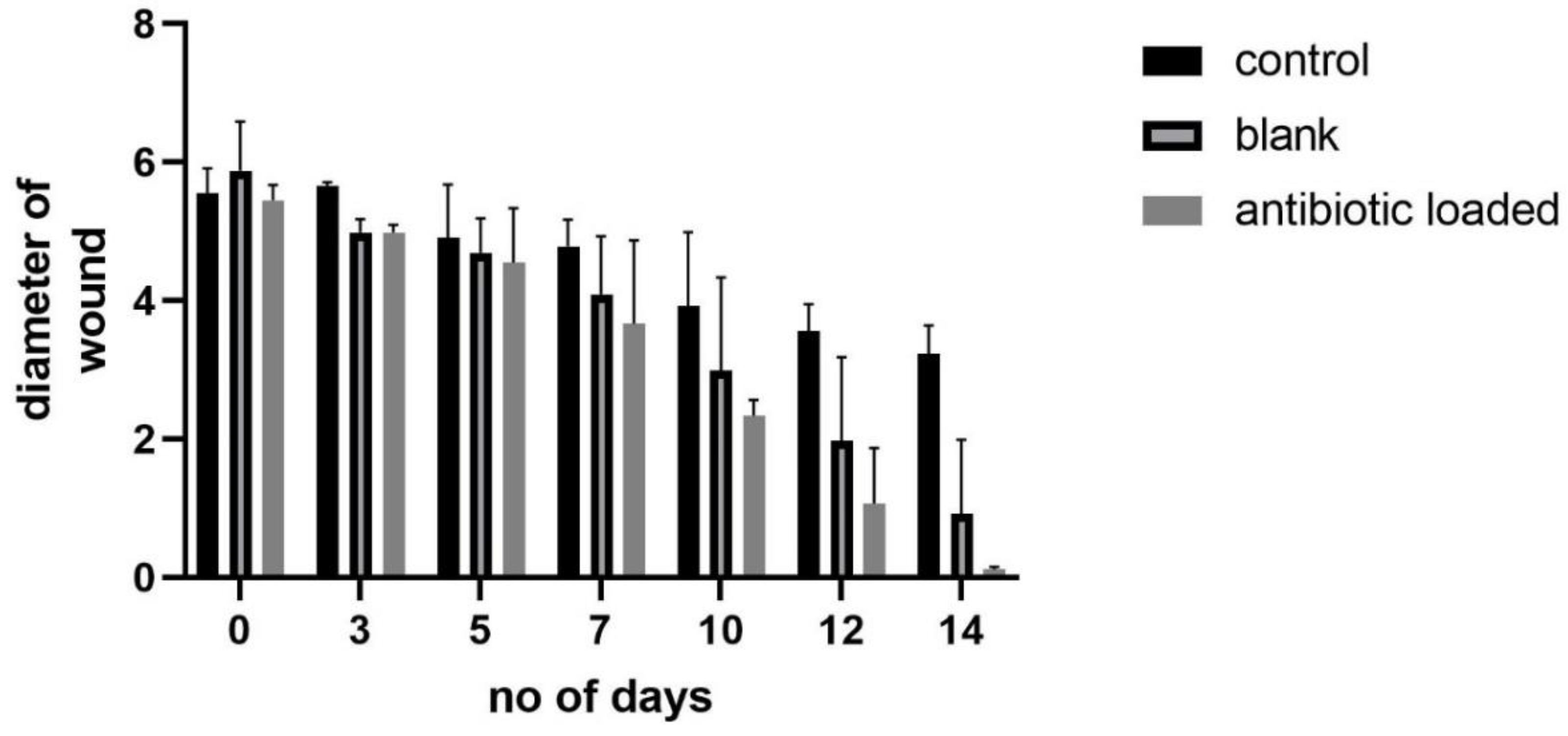

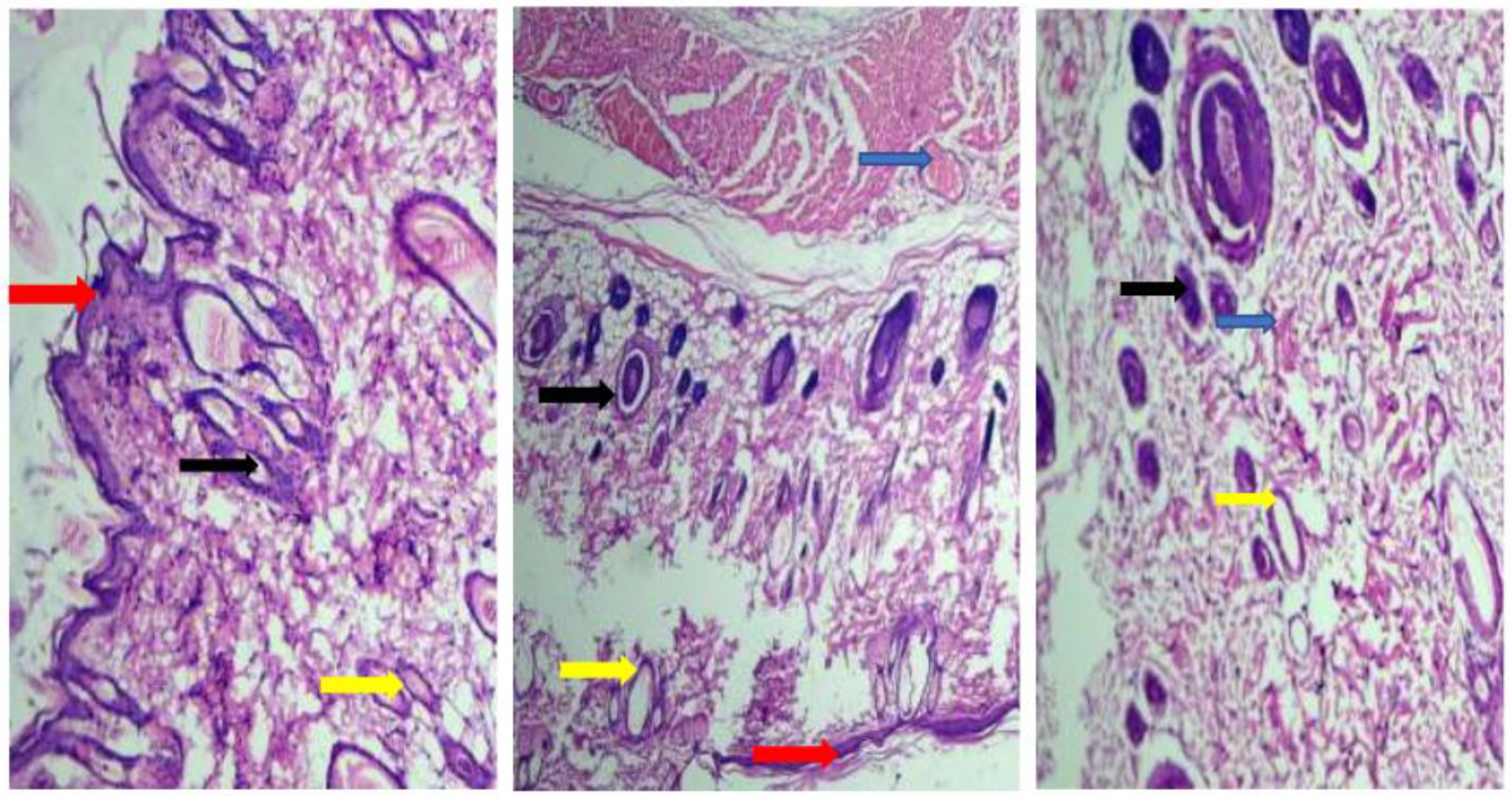

This study revolves around the design/optimization of nanoparticles containing Lincomycin HCl, utilizing chitosan as a polymer and sodium tripolyphosphate as a cross-linker. The ionotropic gelation method was employed for nanoparticle preparation. An optimized formulation was subjected to accelerated stability studies and evaluated through various parameters including particle size (103 ± 43 nm), zeta potential, scanning electron microscopy, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, differential scanning calorimetry, Scanning Electron microscopy (SEM/TEM) and powdered X-ray diffraction. The entrapment efficiency of nanoparticles increased with rising drug concentration up to 0.2 g. FTIR and thermal studies analysis confirmed the absence of interactions between the drug and other components. X-ray diffraction analysis indicated the amorphous nature of Lincomycin HCl within the nanoparticles. Accelerated stability assessment demonstrated the integrity of the formulation. Moreover, Lincomycin HCl effectively prevented rat infections compared to control groups during a two-week study. The LD50 of Lincomycin HCl in rats surpassed 100 mg/kg, with acute toxicity analysis revealing no significant changes between untreated and Lincomycin HCl-treated rats. Histopathological examination indicated no damage to heart, liver, or kidney tissues. Thus, it is reasonable to assert that Lincomycin HCl demonstrated substantial antimicrobial activity in rats, supporting its traditional medicinal usage.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Gel

2.3. Preparation of Calibration Curve

2.4. Characterization Tools for the Gel

2.4.1. Materials-Related to Characterization Techniques

2.4.2. Entrapment Efficiency (EE %) and Loading of Drug (LC %)

2.5. Wound Healing Evaluation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

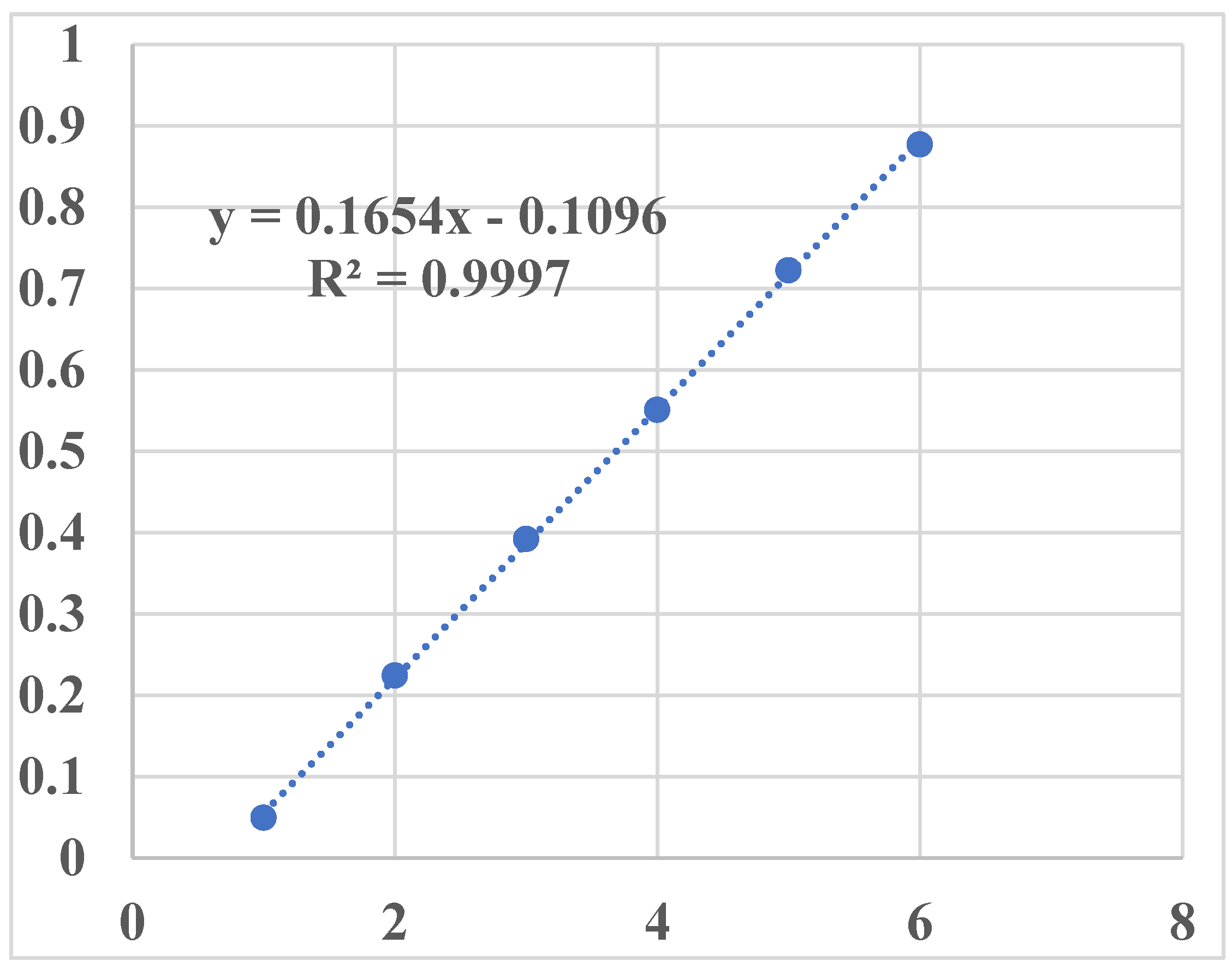

3.1. Generation of Calibration Curve

| Concentration (µg/ml) | Absorbance (au) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0495 |

| 2 | 0.2244 |

| 3 | 0.3922 |

| 4 | 0.551 |

| 5 | 0.7224 |

| 6 | 0.877 |

3.2. Encapsulation Efficiency

3.3. Particle Size and Zeta Potential

3.4. Impact of pH on Chitosan-Based NPs:

3.5. Effect of Stirring Speed on Particle Size and PDI

| Formulations | Chitosan: STPP | Stirring speed (rpm) | Particle size (nm) | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | 50:4 | 700 | 164 ± 57.14 | 0.627 |

| U2 | 50:4 | 800 | 125 ± 64.78 | 0.232 |

| U3 | 50:4 | 900 | 100.04 ± 79 | 0.275 |

| U4 | 50:4 | 1000 | 97.25 ± 71 | 0.39 |

3.6. Impact of Chitosan (CS) Concentration on the Size of Nanoparticles (NPs)

3.7. Zeta Potential

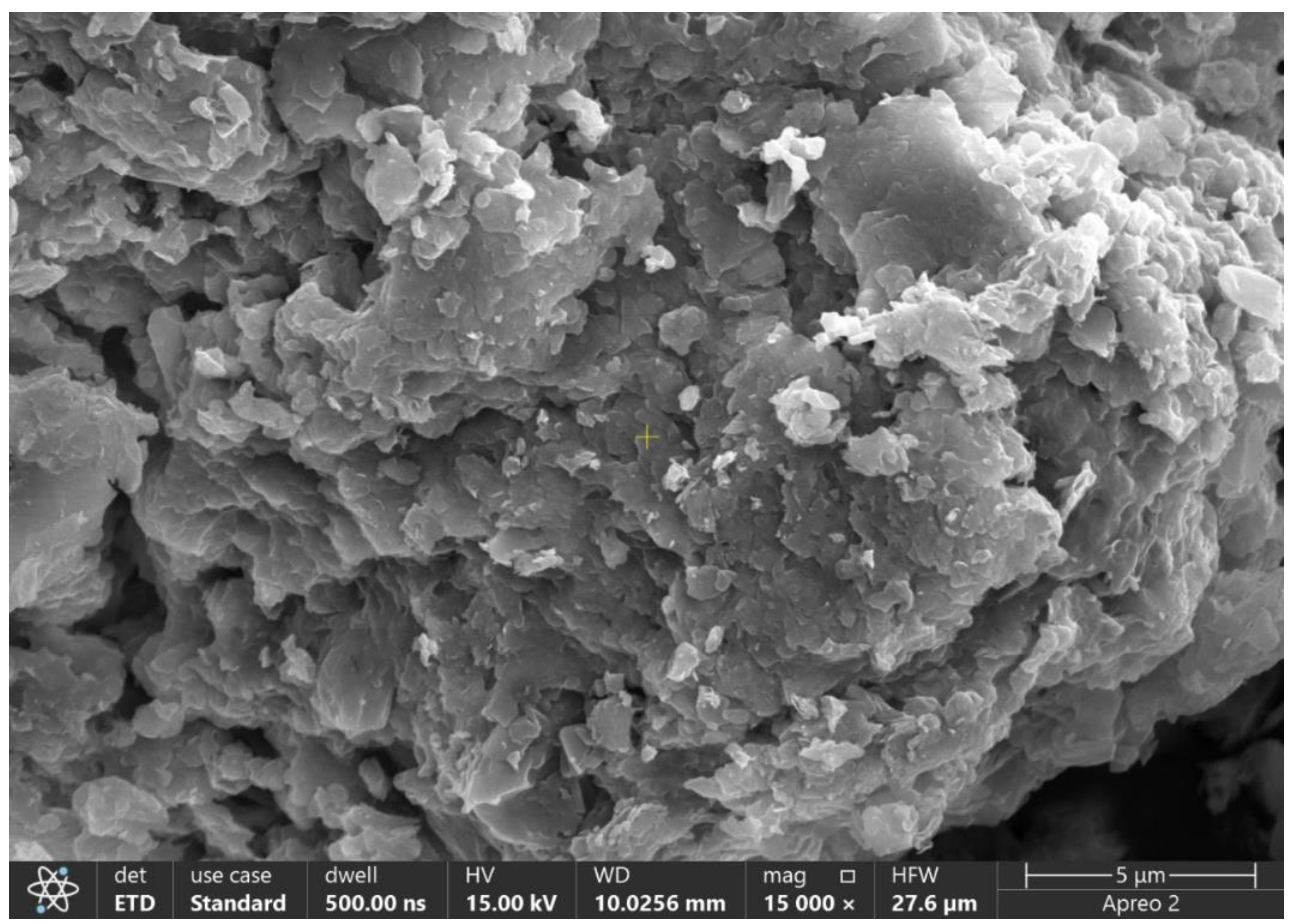

3.8. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM)

3.9. Rheological Studies

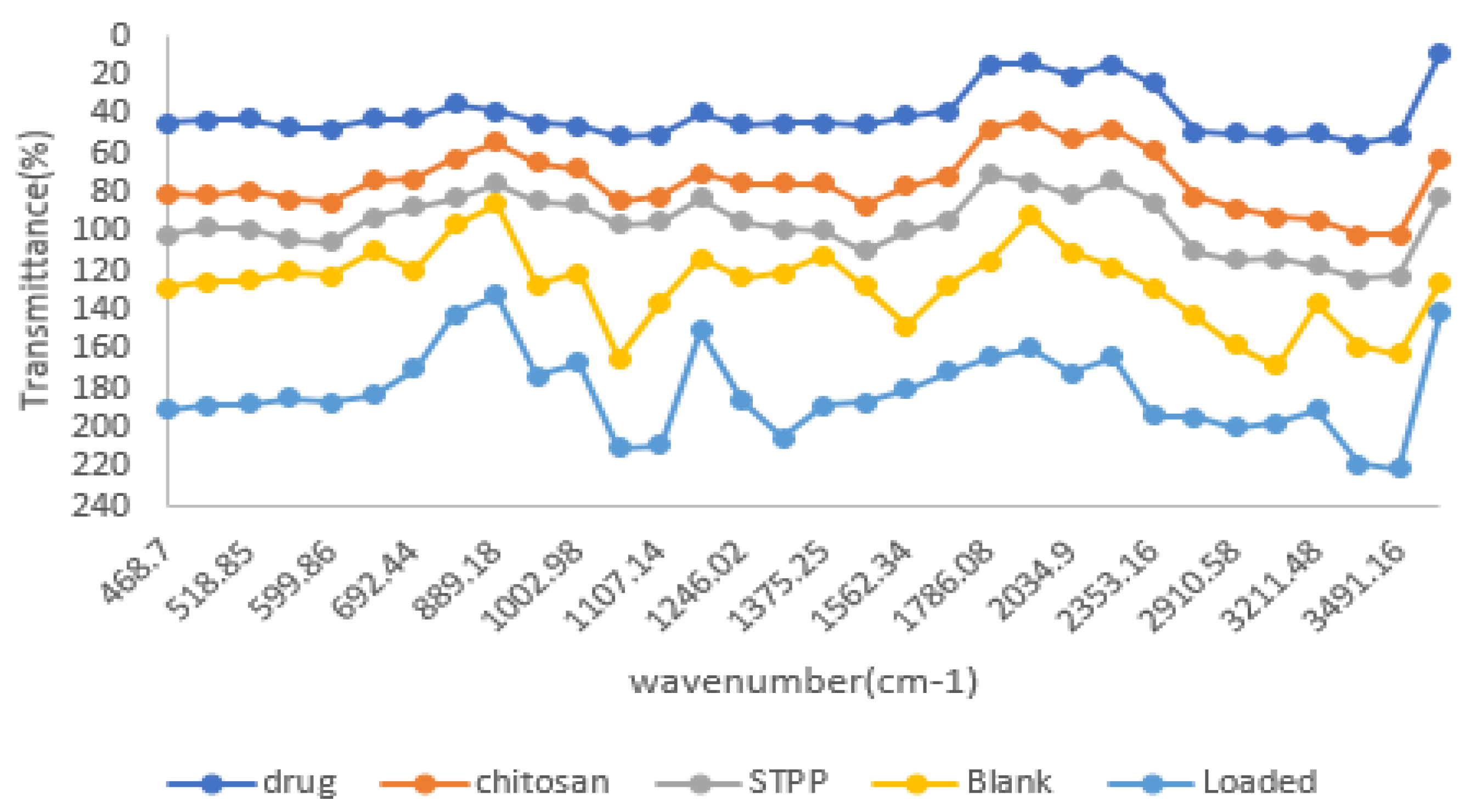

3.11. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

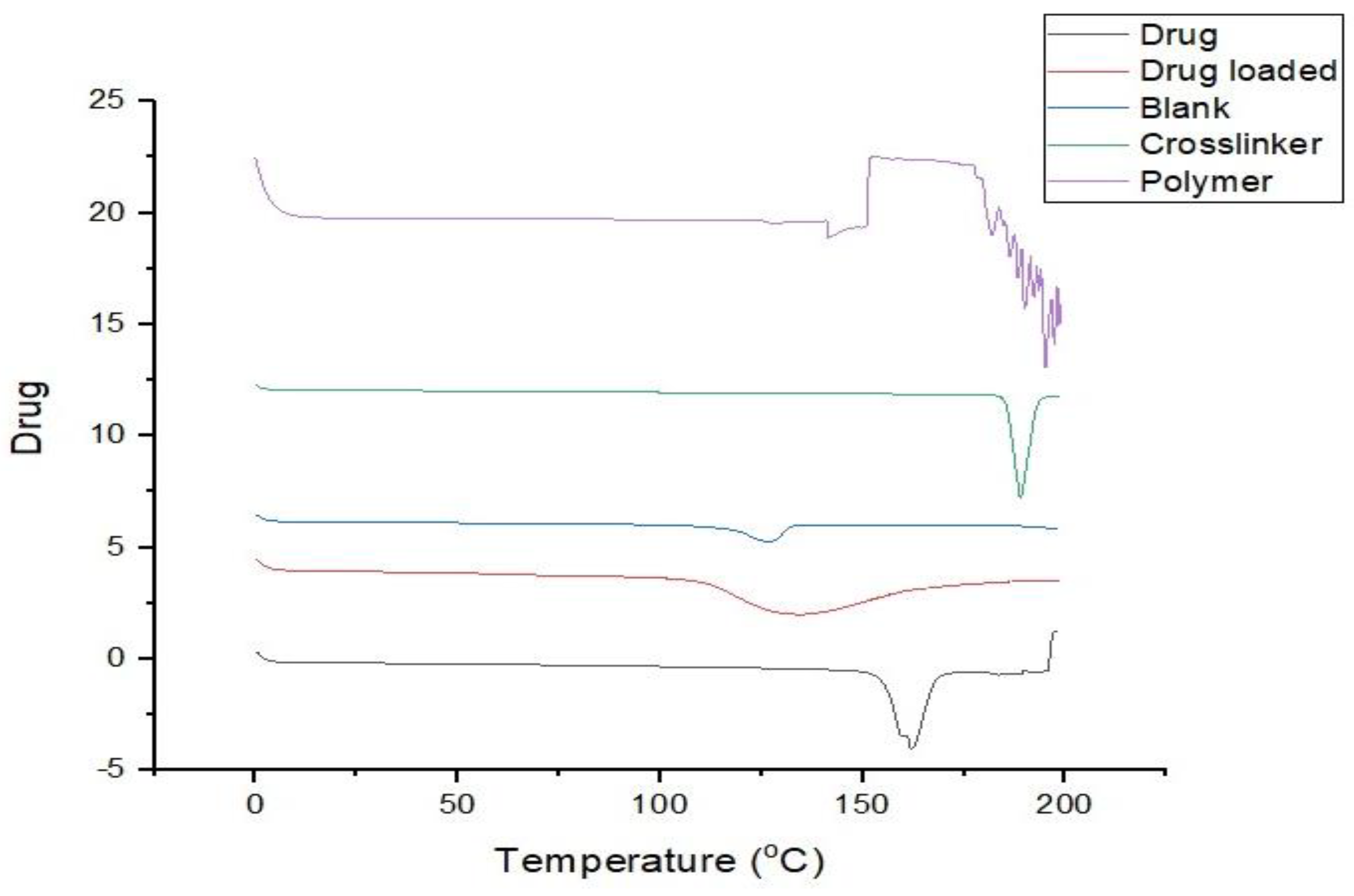

3.12. DSC (Differential Scanning Calorimetry)

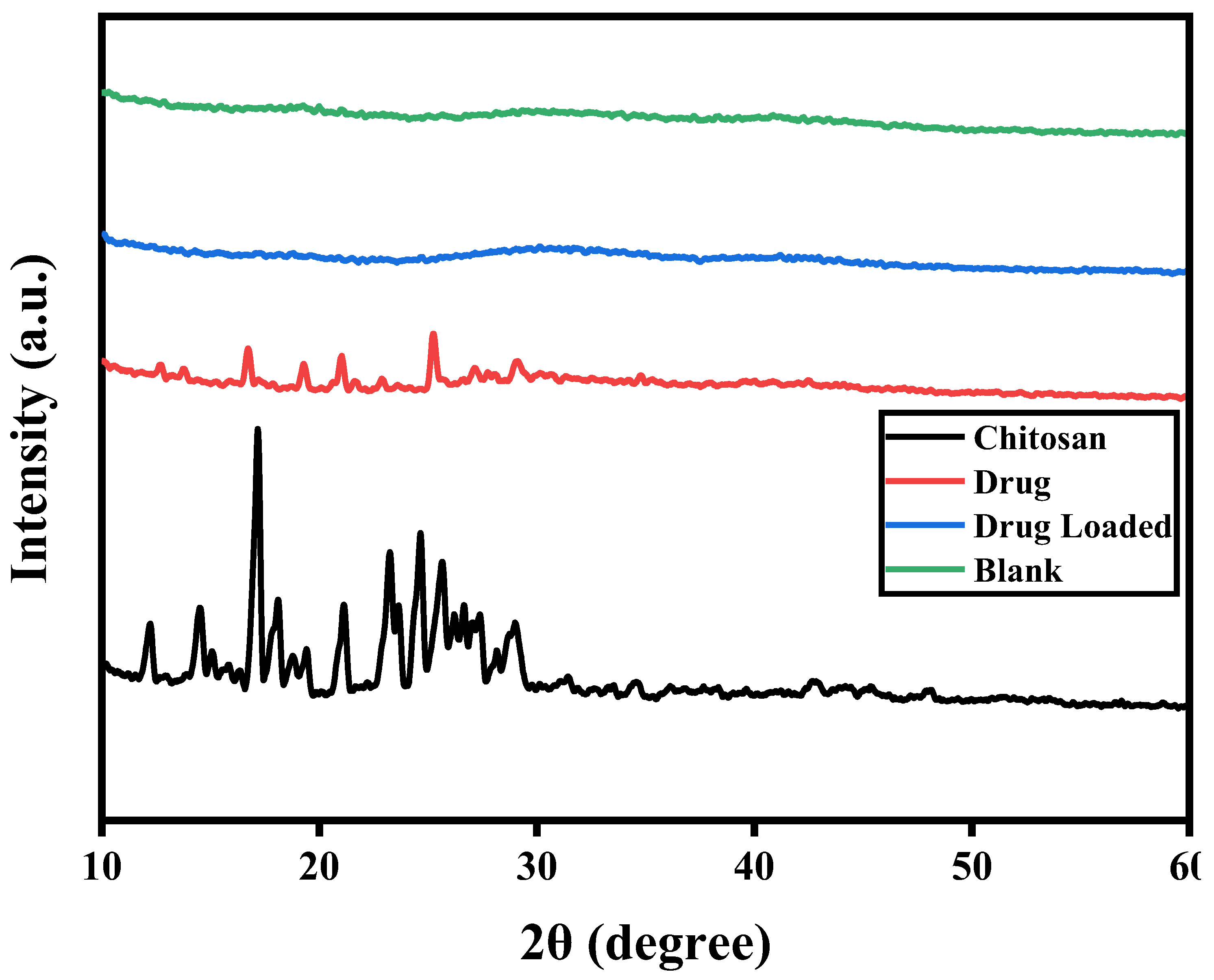

3.13. X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

3.14. Stability Studies

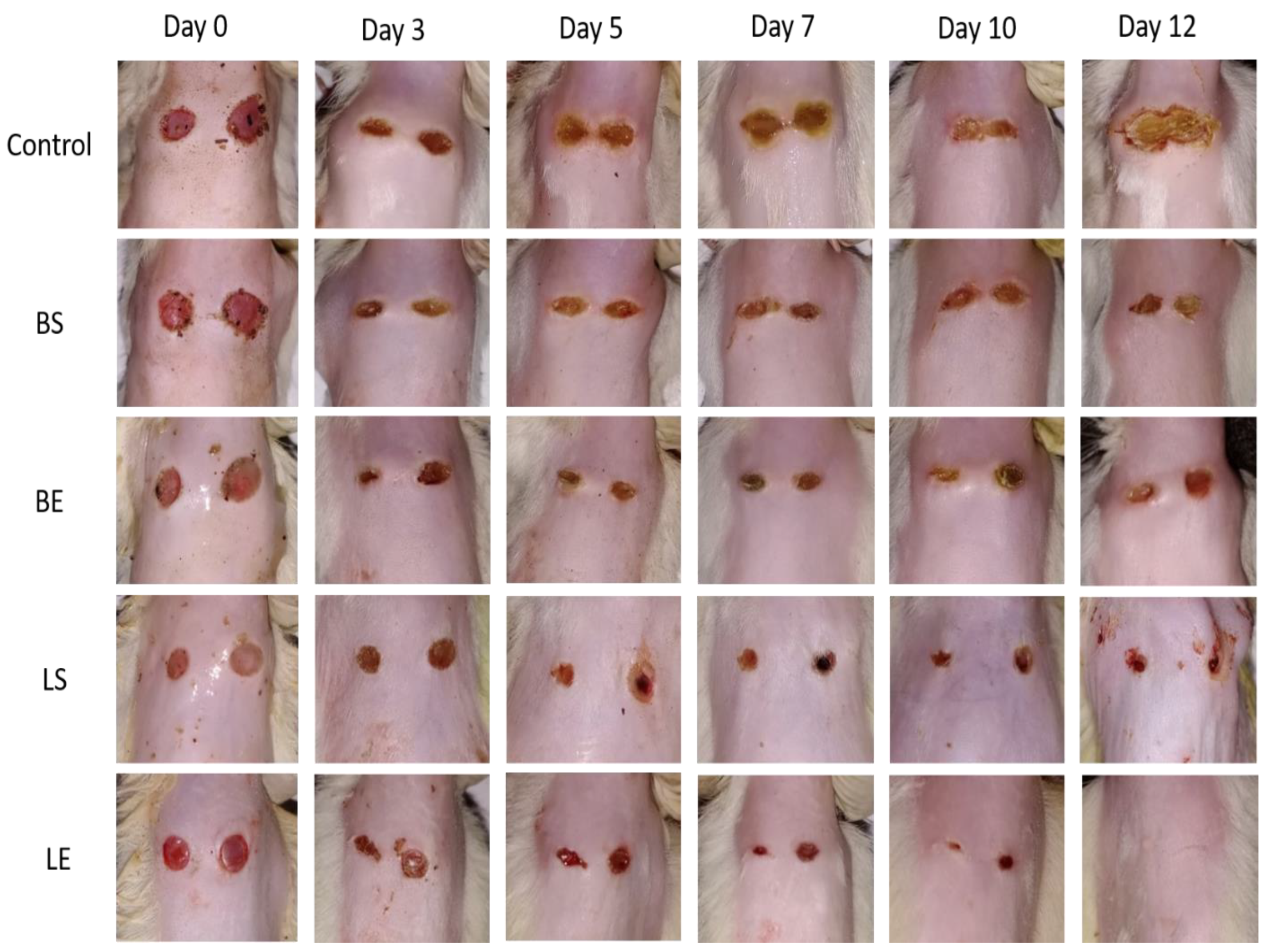

3.15. In Vivo Studies

3.16. Impact on Hematological and Biochemical Parameters in the Course of an Acute Toxicity Investigation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Institution Review Board Statement

Informed Content Statement

Funding

References

- Abd-Allah, H.; Abdel-Aziz, R.T.; Nasr, M. Chitosan nanoparticles making their way to clinical practice: A feasibility study on their topical use for acne treatment. International journal of biological macromolecules 2020, 156, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Zhu, X.; Luo, J.; Shen, M.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, S. Conversion of phosphorus and nitrogen in lincomycin residue during microwave-assisted hydrothermal liquefaction and its application for Pb2+ removal. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 687, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, F.Y.; Aleanizy, F.S.; El Tahir, E.; Alquadeib, B.T.; Alsarra, I.A.; Alanazi, J.S.; Abdelhady, H.G. Preparation, characterization, and antibacterial activity of diclofenac-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2019, 27, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anicuta, S.-G.; Dobre, L.; Stroescu, M.; Jipa, I. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for characterization of antimicrobial films containing chitosan. Analele Universită Ńii din Oradea Fascicula: Ecotoxicologie, Zootehnie şi Tehnologii de Industrie Alimentară 2010, 2010, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, N.; Hussain, A.; Ramteke, A.; Sharma, H.K.; Maji, T.K. Preparation and evaluation of the effect of particle size on the properties of chitosan-montmorillonite nanoparticles loaded with isoniazid. RSC advances 2012, 2, 10519–10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamer Oudih, S.; Tahtat, D.; Nacer Khodja, A.; Mahlous, M.; Hammache, Y.; Guittoum, A.E.; Kebbouche Gana, S. Chitosan nanoparticles with controlled size and zeta potential. Polymer Engineering & Science 2023, 63, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Kim, K.D.; Chun, S.C. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles: A review. Processes 2020, 8, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.; Vijayan, S.; George, T.K.; Jisha, M. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan nanoparticles: Mode of action and factors affecting activity. Fibers and polymers 2017, 18, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Ye, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, T.; . . . Liu, Y. Self-assembled lecithin/chitosan nanoparticles based on phospholipid complex: a feasible strategy to improve entrapment efficiency and transdermal delivery of the poorly lipophilic drug. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2020, 5629–5643.

- El-Hadedy, D.; El-Nour, S.A. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli isolated from Egyptian food by conventional and molecular methods. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2012, 10, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjoo, R.; Soni, S.; Ram, V.; Verma, A. Medium molecular weight chitosan as a carrier for delivery of lincomycin hydrochloride from intra-pocket dental film: Design, development, in vitro and ex vivo characterization. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2016, 6, 008–019. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, U.; Chauhan, S.; Nagaich, U.; Jain, N. Current advances in chitosan nanoparticles based drug delivery and targeting. Advanced pharmaceutical bulletin 2019, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokce, Y.; Cengiz, B.; Yildiz, N.; Calimli, A.; Aktas, Z. Ultrasonication of chitosan nanoparticle suspension: Influence on particle size. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2014, 462, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hadidi, M.; Pouramin, S.; Adinepour, F.; Haghani, S.; Jafari, S.M. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with clove essential oil: Characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 236, 116075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hasan, T.H.; Al-Harmoosh, R.A. Mechanisms of antibiotics resistance in bacteria. Sys Rev Pharm 2020, 11, 817–823. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, S.; Laouini, A.; Fessi, H.; Charcosset, C. Preparation of chitosan–TPP nanoparticles using microengineered membranes–Effect of parameters and encapsulation of tacrine. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2015, 482, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.; Chen, X.; Yin, Y.; Cai, W.; Ke, W.; Kong, Y.; Zheng, H. Preparation and antibacterial properties of O-carboxymethyl chitosan/lincomycin hydrogels. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 2016, 27, 370–384. [Google Scholar]

- Hejjaji, E.M.; Smith, A.M.; Morris, G.A. Evaluation of the mucoadhesive properties of chitosan nanoparticles prepared using different chitosan to tripolyphosphate (CS: TPP) ratios. International journal of biological macromolecules 2018, 120, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Sahudin, S. Preparation, characterisation and colloidal stability of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles: Optimisation of formulation and process parameters. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2016, 8, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, I.A.; Ebeid, H.M.; Kishk, Y.F.; Abdel Fattah, A.F. A. K.; Mahmoud, K.F.; Ibrahim, A.; . . . Mahmoud, K. Effect of grinding and particle size on some physical and rheological properties of chitosan. Arab Universities Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2019, 27, 1513–1527.

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: a natural biopolymer with a wide and varied range of applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonassen, H.; Kjøniksen, A.-L.; Hiorth, M. Effects of ionic strength on the size and compactness of chitosan nanoparticles. Colloid and Polymer Science 2012, 290, 919–929. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, E.A.; Ma, J.; Xiaobin, M.; Jie, Y.; Mengyue, L.; Hong, L.; . . . Liu, A. Safety evaluation study of lincomycin and spectinomycin hydrochloride intramuscular injection in chickens. Toxicology Reports 2022, 9, 204–209.

- Kshirsagar, N. Drug delivery systems. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 32, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Tyagi, C. (2022). PREPARATION AND EVALUATION OF LIPOSOMAL GEL OF LINCOMYCIN HCL.

- Kumar, S.; Maurya, H. An Overview on Advance Vesicles Formulation as a Drug Carrier for NDDS. European Journal of Biomedical 2018, 5, 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S.B.; Marshall, B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nature medicine 2004, 10 (Suppl 12), S122–S129. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Porras, C.; Cruz-Alcantar, P.; Espinosa-Solís, V.; Martínez-Guerra, E.; Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Compean Martínez, I.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Application of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and modulated differential scanning calorimetry (MDSC) in food and drug industries. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; Zhou, J.; Chen, H. Application of nano drug delivery system (NDDS) in cancer therapy: A perspective. Recent patents on anti-cancer drug discovery 2023, 18, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Marei, N.H.; Abd El-Samie, E.; Salah, T.; Saad, G.R.; Elwahy, A.H. Isolation and characterization of chitosan from different local insects in Egypt. International journal of biological macromolecules 2016, 82, 871–877. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, S.; Anderson, B.D. Determination of drug release kinetics from nanoparticles: overcoming pitfalls of the dynamic dialysis method. Molecular pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 3076–3089. [Google Scholar]

- Murugaiyan, J.; Kumar, P.A.; Rao, G.S.; Iskandar, K.; Hawser, S.; Hays, J.P.; . . . Jose, R.A.M. Progress in alternative strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance: Focus on antibiotics. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 200.

- Najim, S.S. (2017). SPECTROPHTOMETERIC DETERMINATION OF LINCOMYCIN IN PHARMACEUTICAL MEDICATION.

- Pan, C.; Qian, J.; Zhao, C.; Yang, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, H. Study on the relationship between crosslinking degree and properties of TPP crosslinked chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 241, 116349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Papathoti, N.K.; Pervaiz, F.; Mushtaq, R.; Noreen, S. Formulation and optimization of terbinafine HCl loaded chitosan/xanthan gum nanoparticles containing gel: Ex-vivo permeation and in-vivo antifungal studies. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021, 66, 102935. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu-Pelin, G.; Fufă, O.; Popescu, R.C.; Savu, D.; Socol, M.; Zgură, I. Popescu-Pelin, G.; Fufă, O.; Popescu, R.C.; Savu, D.; Socol, M.; Zgură, I.; . . . Socol, G. Lincomycin–embedded PANI–based coatings for biomedical applications. Applied Surface Science 2018, 455, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Hu, C.; Zou, X. Preparation and antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydrate research 2004, 339, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, X.; He, G.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Cai, W.; Fan, L.; Fardim, P. Preparation and properties of polyvinyl alcohol/N–succinyl chitosan/lincomycin composite antibacterial hydrogels for wound dressing. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 261, 117875. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Pulido, G.; Medina, D.I. An overview of gastrointestinal mucus rheology under different pH conditions and introduction to pH-dependent rheological interactions with PLGA and chitosan nanoparticles. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2021, 159, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Saadatkhah, N.; Carillo Garcia, A.; Ackermann, S.; Leclerc, P.; Latifi, M.; Samih, S. Saadatkhah, N.; Carillo Garcia, A.; Ackermann, S.; Leclerc, P.; Latifi, M.; Samih, S.; . . . Chaouki, J. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Thermogravimetric analysis—TGA. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2020, 98, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Safari, J.; Zarnegar, Z. Advanced drug delivery systems: Nanotechnology of health design A review. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2014, 18, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva, S.M.; Crespo, A.M.; Vaz, F.; Filipe, M.; Santos, D.; Jacinto, T.A. Saraiva, S.M.; Crespo, A.M.; Vaz, F.; Filipe, M.; Santos, D.; Jacinto, T.A.; . . . Coutinho, P. Development and Characterization of Thermal Water Gel Comprising Helichrysum italicum Essential Oil-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for Skin Care. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, A.; Ahmad, M.; Huma, T.; Khalid, I.; Ahmad, I. Evaluation of low molecular weight cross linked chitosan nanoparticles, to enhance the bioavailability of 5-flourouracil. Dose-Response 2021, 19, 15593258211025353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M. Transdermal and intravenous nano drug delivery systems: present and future Applications of targeted nano drugs and delivery systems (pp. 499–550): Elsevier.

- Shirolkar 2019, M.M.; Athavale, R.; Ravindran, S.; Rale, V.; Kulkarni, A.; Deokar, R. Antibiotics functionalization intervened morphological, chemical and electronic modifications in chitosan nanoparticles. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2021, 25, 100657. [Google Scholar]

- Singh Malik, D.; Mital, N.; Kaur, G. Topical drug delivery systems: a patent review. Expert opinion on therapeutic patents 2016, 26, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sobhani, Z.; Samani, S.M.; Montaseri, H.; Khezri, E. Nanoparticles of chitosan loaded ciprofloxacin: fabrication and antimicrobial activity. Advanced pharmaceutical bulletin 2017, 7, 427. [Google Scholar]

- Tantala, J.; Thumanu, K.; Rachtanapun, C. An assessment of antibacterial mode of action of chitosan on Listeria innocua cells using real-time HATR-FTIR spectroscopy. International journal of biological macromolecules 2019, 135, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thandapani, G.; Prasad, S.; Sudha, P.; Sukumaran, A. Size optimization and in vitro biocom46. patibility studies of chitosan nanoparticles. International journal of biological macromolecules 2017, 104, 1794–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, G.; Tiwari, R.; Sriwastawa, B.; Bhati, L.; Pandey, S.; Pandey, P.; Bannerjee, S.K. Drug delivery systems: An updated review. International journal of pharmaceutical investigation 2012, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, J.; Tong, H.H.; Chow, S.F. In vitro release study of the polymeric drug nanoparticles: development and validation of a novel method. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Allah, H.; Abdel-Aziz, R.T.; Nasr, M. Chitosan nanoparticles making their way to clinical practice: A feasibility study on their topical use for acne treatment. International journal of biological macromolecules 2020, 156, 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, M.; Agarwal, M.K.; Shrivastav, N.; Pandey, S.; Das, R.; Gaur, P. Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles and their in-vitro characterization. International Journal of Life-Sciences Scientific Research 2018, 4, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Zhu, X.; Luo, J.; Shen, M.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, S. Conversion of phosphorus and nitrogen in lincomycin residue during microwave-assisted hydrothermal liquefaction and its application for Pb2+ removal. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 687, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmet, U. Preparation of allantoin loaded chitosan nanoparticles and influence of molecular weight of chitosan on drug release. İnönü Üniversitesi Sağlık Hizmetleri Meslek Yüksek Okulu Dergisi 2020, 8, 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Algharib, S.A.; Dawood, A.; Zhou, K.; Chen, D.; Li, C.; Meng, K.; . . . Huang, L. Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles by ionotropic gelation technique: Effects of formulation parameters and in vitro characterization. Journal of Molecular Structure 2022, 1252, 132129.

- Alqahtani, F.Y.; Aleanizy, F.S.; El Tahir, E.; Alquadeib, B.T.; Alsarra, I.A.; Alanazi, J.S.; Abdelhady, H.G. Preparation, characterization, and antibacterial activity of diclofenac-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Saudi pharmaceutical journal 2019, 27, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, M.S.; Al-Yousef, H.M.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Rehman, M.T.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Almarfidi, O.; . . . Syed, R. Preparation, characterization, and in vitro-in silico biological activities of Jatropha pelargoniifolia extract loaded chitosan nanoparticles. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2021, 606, 120867.

- Athavale, R.; Sapre, N.; Rale, V.; Tongaonkar, S.; Manna, G.; Kulkarni, A.; Shirolkar, M.M. Tuning the surface charge properties of chitosan nanoparticles. Materials Letters 2022, 308, 131114. [Google Scholar]

- Basha, M.; AbouSamra, M.M.; Awad, G.A.; Mansy, S.S. A potential antibacterial wound dressing of cefadroxil chitosan nanoparticles in situ gel: Fabrication, in vitro optimization and in vivo evaluation. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2018, 544, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bin-Jumah, M.; Gilani, S.J.; Jahangir, M.A.; Zafar, A.; Alshehri, S.; Yasir, M.; . . . Imam, S.S. Clarithromycin-loaded ocular chitosan nanoparticle: formulation, optimization, characterization, ocular irritation, and antimicrobial activity. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2020, 7861–7875.

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Kim, K.D.; Chun, S.C. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles: A review. Processes 2020, 8, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, Y.J.; Yunus, M.H. M.; Fauzi, M.B.; Tabata, Y.; Hiraoka, Y.; Phang, S.J.; . . . Yazid, M.D. Gelatin–chitosan–cellulose nanocrystals as an acellular scaffold for wound healing application: fabrication, characterisation and cytocompatibility towards primary human skin cells. Cellulose 2023, 30, 5071–5092.

- Chhibber, T.; Gondil, V.S.; Sinha, V. Development of chitosan-based hydrogel containing antibiofilm agents for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus–infected burn wound in mice. Aaps Pharmscitech 2020, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Divya, K.; Jisha, M. Chitosan nanoparticles preparation and applications. Environmental chemistry letters 2018, 16, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.; Vijayan, S.; George, T.K.; Jisha, M. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan nanoparticles: Mode of action and factors affecting activity. Fibers and polymers 2017, 18, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Sheikh, A.; Abourehab, M.A.; Kesharwani, P. Advancements in polymeric nanocarriers to mediate targeted therapy against triple-negative breast cancer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumezescu, V.; Negut, I.; Gherasim, O.; Birca, A.C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Hudita, A.; . . . Holban, A.M. Antimicrobial applications of MAPLE processed coatings based on PLGA and lincomycin functionalized magnetite nanoparticles. Applied Surface Science 2019, 484, 587–599. [CrossRef]

- Gurses, M.S.; Erkey, C.; Kizilel, S.; Uzun, A. Characterization of sodium tripolyphosphate and sodium citrate dehydrate residues on surfaces. Talanta 2018, 176, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejjaji, E.M.; Smith, A.M.; Morris, G.A. Evaluation of the mucoadhesive properties of chitosan nanoparticles prepared using different chitosan to tripolyphosphate (CS: TPP) ratios. International journal of biological macromolecules 2018, 120, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.K. Drug delivery systems; Springer, 2008; Vol. 251. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, R.M.; El Arini, S.K.; AbouSamra, M.M.; Zaki, H.S.; El-Gazaerly, O.N.; Elbary, A.A. Development of lecithin/chitosan nanoparticles for promoting topical delivery of propranolol hydrochloride: Design, optimization and in-vivo evaluation. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2021, 110, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Yu, H.; Kim, Y.-M. Bactericidal activity of usnic acid-chitosan nanoparticles against persister cells of biofilm-forming pathogenic bacteria. Marine Drugs 2020, 18, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, F.; Xiong, F.; Gu, N. The smart drug delivery system and its clinical potential. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.S.; Biswas, N.; Karim, K.M.; Guha, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Behera, M.; Kuotsu, K. Drug delivery system based on chronobiology—A review. Journal of controlled release 2010, 147, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marei, N.H.; Abd El-Samie, E.; Salah, T.; Saad, G.R.; Elwahy, A.H. Isolation and characterization of chitosan from different local insects in Egypt. International journal of biological macromolecules 2016, 82, 871–877. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, W.; Chu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N. A review on nano-based drug delivery system for cancer chemoimmunotherapy. Nano-micro letters 2020, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Najim, S.S. (2017). SPECTROPHTOMETERIC DETERMINATION OF LINCOMYCIN IN PHARMACEUTICAL MEDICATION.

- Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, T.T. H.; Wang, S.-L.; Vo, T.P. K.; Nguyen, A.D. Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles by TPP ionic gelation combined with spray drying, and the antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles and a chitosan nanoparticle–amoxicillin complex. Research on Chemical Intermediates 2017, 43, 3527–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, S.; Pervaiz, F.; Ashames, A.; Buabeid, M.; Fahelelbom, K.; Shoukat, H.; . . . Murtaza, G. Optimization of novel naproxen-loaded chitosan/carrageenan nanocarrier-based gel for topical delivery: Ex vivo, histopathological, and in vivo evaluation. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 557.

- Pan, C.; Qian, J.; Zhao, C.; Yang, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, H. Study on the relationship between crosslinking degree and properties of TPP crosslinked chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 241, 116349. [Google Scholar]

- Pawar, H.V.; Tetteh, J.; Debrah, P.; Boateng, J.S. Comparison of in vitro antibacterial activity of streptomycin-diclofenac loaded composite biomaterial dressings with commercial silver based antimicrobial wound dressings. International journal of biological macromolecules 2019, 121, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, F.; Mushtaq, R.; Noreen, S. Formulation and optimization of terbinafine HCl loaded chitosan/xanthan gum nanoparticles containing gel: Ex-vivo permeation and in-vivo antifungal studies. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021, 66, 102935. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu-Pelin, G.; Fufă, O.; Popescu, R.; Savu, D.; Socol, M.; Zgură, I.; . . . Socol, G. Lincomycin–embedded PANI–based coatings for biomedical applications. Applied Surface Science 2018, 455, 653–666.

- Qing, X.; He, G.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Cai, W.; Fan, L.; Fardim, P. Preparation and properties of polyvinyl alcohol/N–succinyl chitosan/lincomycin composite antibacterial hydrogels for wound dressing. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 261, 117875. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, N.K.; Kumar, S.S. D.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. A review on nanoparticle based treatment for wound healing. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2018, 44, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Nayak, B.S.; Maddiboyina, B.; Nandi, S. Chitosan based urapidil microparticle development in approach to improve mechanical strength by cold hyperosmotic dextrose solution technique. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2022, 76, 103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, S.M.; Crespo, A.M.; Vaz, F.; Filipe, M.; Santos, D.; Jacinto, T.A.; . . . Coutinho, P. Development and Characterization of Thermal Water Gel Comprising Helichrysum italicum Essential Oil-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for Skin Care. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 8.

- Sethi, A.; Ahmad, M.; Huma, T.; Khalid, I.; Ahmad, I. Evaluation of low molecular weight cross linked chitosan nanoparticles, to enhance the bioavailability of 5-flourouracil. Dose-Response 2021, 19, 15593258211025353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shantier, S.W.; Elimam, M.M.; Mohamed, M.A.; Gadkariem, E.A. Stability studies on lincomycin HCl using validated developed second derivative spectrophotometric method. J Innov Pharm Biol Sci 2017, 4, 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Skwarczynski, M.; Bashiri, S.; Yuan, Y.; Ziora, Z.M.; Nabil, O.; Masuda, K.; . . . Ruktanonchai, U. Antimicrobial activity enhancers: towards smart delivery of antimicrobial agents. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 412.

- Sobhani, Z.; Samani, S.M.; Montaseri, H.; Khezri, E. Nanoparticles of chitosan loaded ciprofloxacin: fabrication and antimicrobial activity. Advanced pharmaceutical bulletin 2017, 7, 427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vikas, K.; Arvind, S.; Ashish, S.; Gourav, J.; Vipasha, D. Recent advances in ndds (novel drug delivery system) for delivery of anti-hypertensive drugs. Int J Drug Dev Res 2011, 3, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Meng, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K. Chitosan derivatives and their application in biomedicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 487. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.; Yang, B.; Chen, K.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Z.; Yin, W.; . . . Sheng, Q. Sodium tripolyphosphate as a selective depressant for separating magnesite from dolomite and its depression mechanism. Powder Technology 2021, 382, 244–253.

- Yassin, A.E.; Albekairy, A.M.; Omer, M.E.; Almutairi, A.; Alotaibi, Y.; Althuwaini, S.; . . . Alluhaim, W. Chitosan-Coated Azithromycin/Ciprofloxacin-Loaded Polycaprolactone Nanoparticles: A Characterization and Potency Study. Nanotechnology Science and Applications 2023, 59–72.

| Formulation | Chitosan: STPP (mg) | Particle size (nm) | PDI | Zeta potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 50:01 | 106.9 | 0.274 | 28 ± 4.91 |

| F2 | 100:01 | 152.4 | 0.382 | 29.4 ± 4.91 |

| F3 | 150:01 | 265 | 0.511 | 22.8 ± 5.54 |

| F4 | 200:01 | 368.4 | 0.997 | 20 ± 46 |

| Formulations | Chitosan: STPP (mg) | particle size | PDI | zeta potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 50:01 | 106.9 | 0.274 | 24.7 ± 6.24 |

| F2 | 50:02 | 125.4 | 0.232 | 22.9 ± 3.95 |

| F3 | 50:03 | 113.2 | 0.465 | 22.6 ± 5.57 |

| F4 | 50:04 | 103.2 | 0.243 | 20 ± 4.16 |

| Parameters | Observations of control and lincomycin HCl treated group | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 minutes | 4 h | 24 h | 7 days | 14 days | |||||||||||

| Control | Blank treated | L.HCL treated | Control | Blank treated | L.Hcl treated | Control | Blank treated | L.treated | Control | Blank treated | Ltreated | Control | Blank treated | L. treated | |

| Eye colour | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Pupil size | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Salivation | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Skin | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Fur | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Urine colour | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Feces consistency | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Convulsions & tremors | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Itching | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Coma | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Sleep | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Somatomotor activity & behavior pattern | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Days | Control | Treatment (100mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | ||

| 1 | 163.6±1.36 | 177.2±1.40 ns |

| 7 | 171.2±1.98 | 174.2±0.86 ns |

| 14 | 192.4±1.60 | 196.4±1.03 ns |

| Parameters | Units | Normal Control | Treatment with a blank formulation | Treatment with loaded formulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | g/dl | 11.4±0.298 | 12.78±0.306ns | 12.6±0.51ns |

| TLC | ×109/l | 11.0±0.70 | 11.9±0.57 ns | 12.0±0.55 ns |

| Total RBC | ×1012/l | 4.20±0.19 | 6.54±0.16 ns | 7.58±0.32 ns |

| HCT (PCV) | % | 40.5±0.58 | 38.8±0.86 ns | 40.6±0.68 ns |

| MCV | Fl | 64.0±1.82 | 52.2±1.77 ns | 53.6±1.34 ns |

| MCH | Pg | 14.6±1.20 | 19.8±0.70 ns | 16.6±0.65 ns |

| MCHC | % | 35.6±0.65 | 35.2±1.00 ns | 31.0±1.30 ns |

| Platelets | ×103/uL | 561.8±5.81 | 614.4±1.6*** | 971±2.0*** |

| Neutrophils | % | 36.9±2.44 | 44.8±1.29 ns | 17±1.79 ns |

| Lymphocytes | % | 23.8±1.65 | 39.6±1.22 ns | 79±1.20 ns |

| Monocytes | % | 2.74±0.73 | 3.2±0.81 ns | 3.0±1.71 ns |

| Eosinophils | % | 1.45±0.31 | 1.32±0.78 | 1.0±0.64 |

| Total WBCs | 103/uL |

14.22±0.29 | 19.18±0.65 | 17±1.56 |

| Parameters | Units | Control | Blank Treated | Lincomycin HCl treated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin | mg/dL | 0.20±0.01 | 0.33±0.017ns | 0.3±0.023 |

| ALT | µ/L | 48.0±1.65 | 76.0±2.43* | 61±2.87 |

| AST | µ/L | 241±1.80 | 331±2.54ns | 272±2.64 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | µ/L | 243±3.03 | 298±3.35 ns | 341±3.84 |

| Protein | g/dL | 7.5±0.23 | 6.7±0.19 ns | 6.9±0.25 |

| Albumin | g/dL | 4.3±0.15 | 3.7±0.09 ns | 4.0±0.04 |

| Globulin | g/dL | 3.2±0.122 | 3.0±0.16 ns | 2.9±0.21 |

| Blood urea | mg/dL | 53.0±1.41 | 49±1.65 ns | 46±1.92 |

| Serum creatinine | mg/dL | 0.42±0.034 | 0.33±0.025 ns | 0.31±0.043 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).