Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

17 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Formulation Optimization

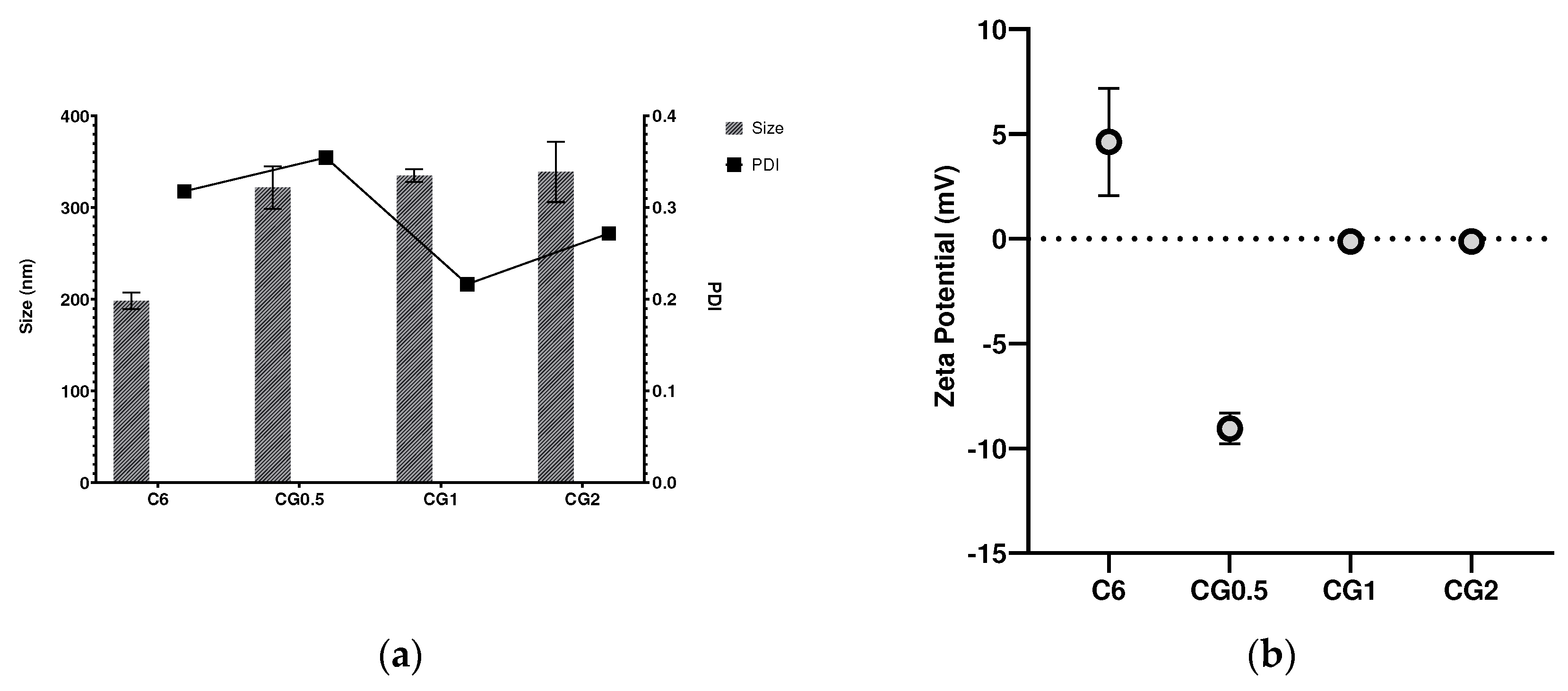

2.2. Effect of drug loading on size, PDI and zeta potential

2.3. Entrapment of gentamicin in the formulation.

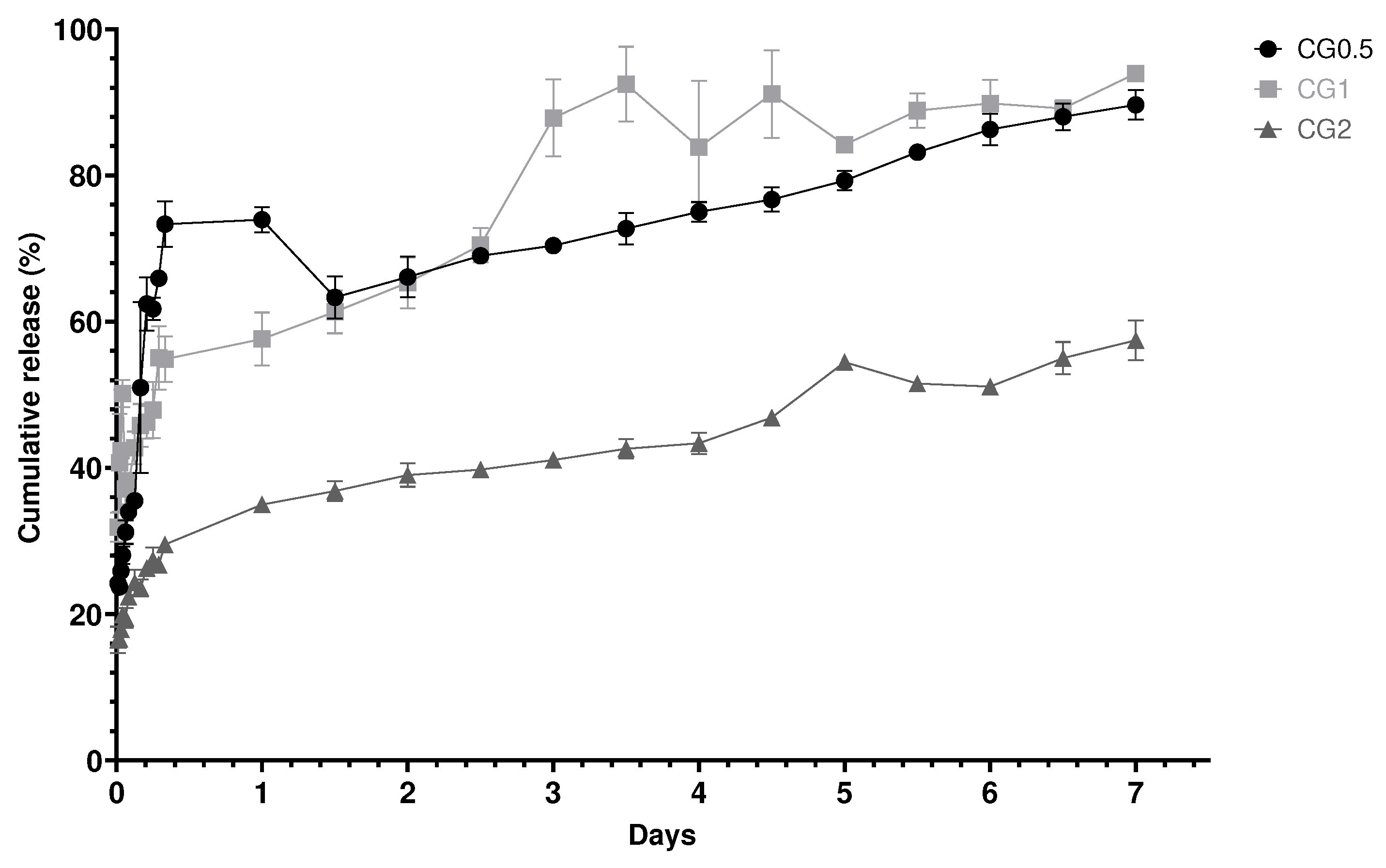

2.4. In vitro Release studies from loaded nanoparticles

2.4.1. In vitro Release Kinetics from chitosan nanoparticles

2.5. Antimicrobial effects of gentamicin leaded chitosan nanoparticles

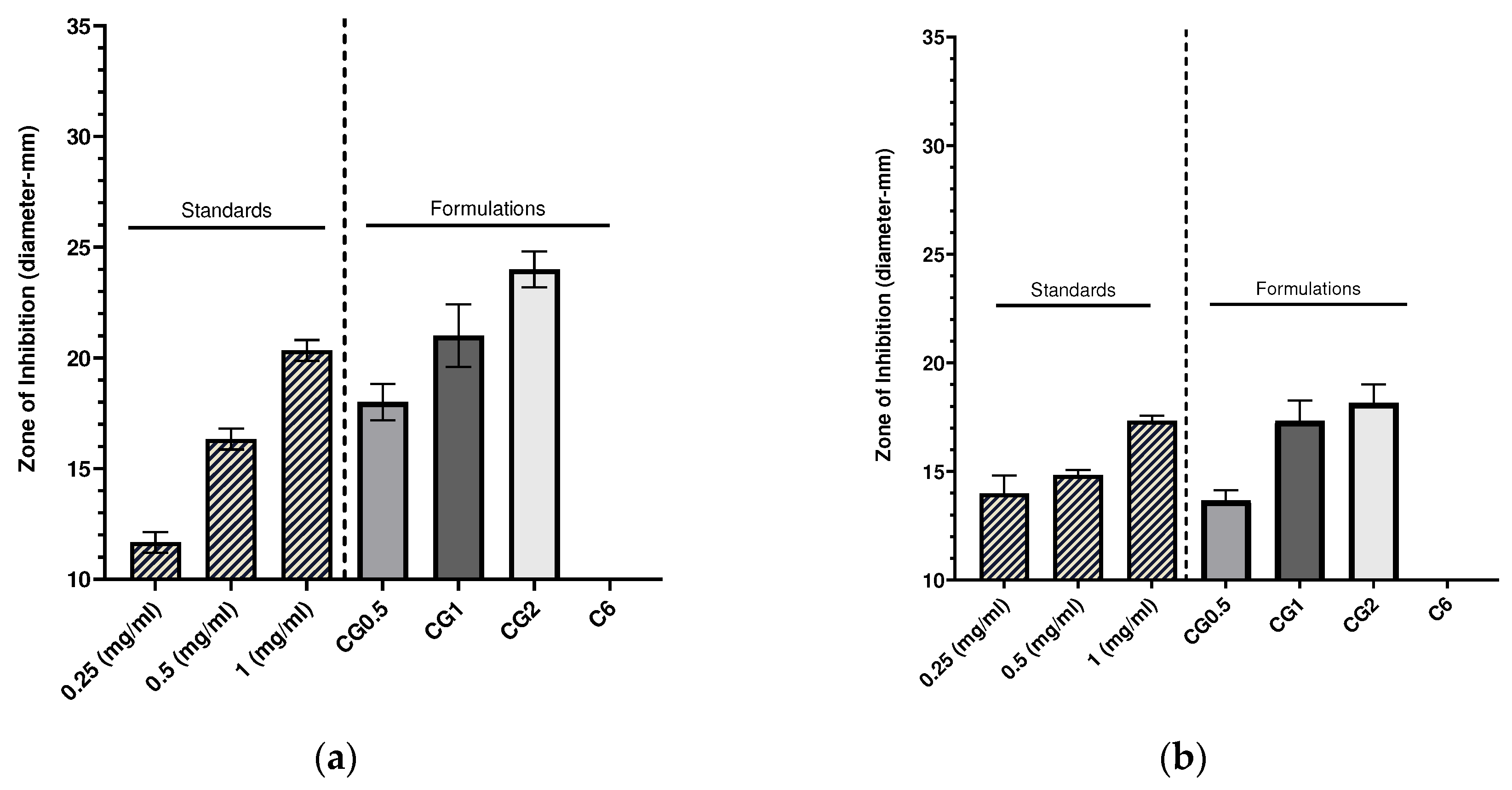

2.5.1. Zones of inhibition produced from gentamicin loaded chitosan nanoparticles by well diffusion assay.

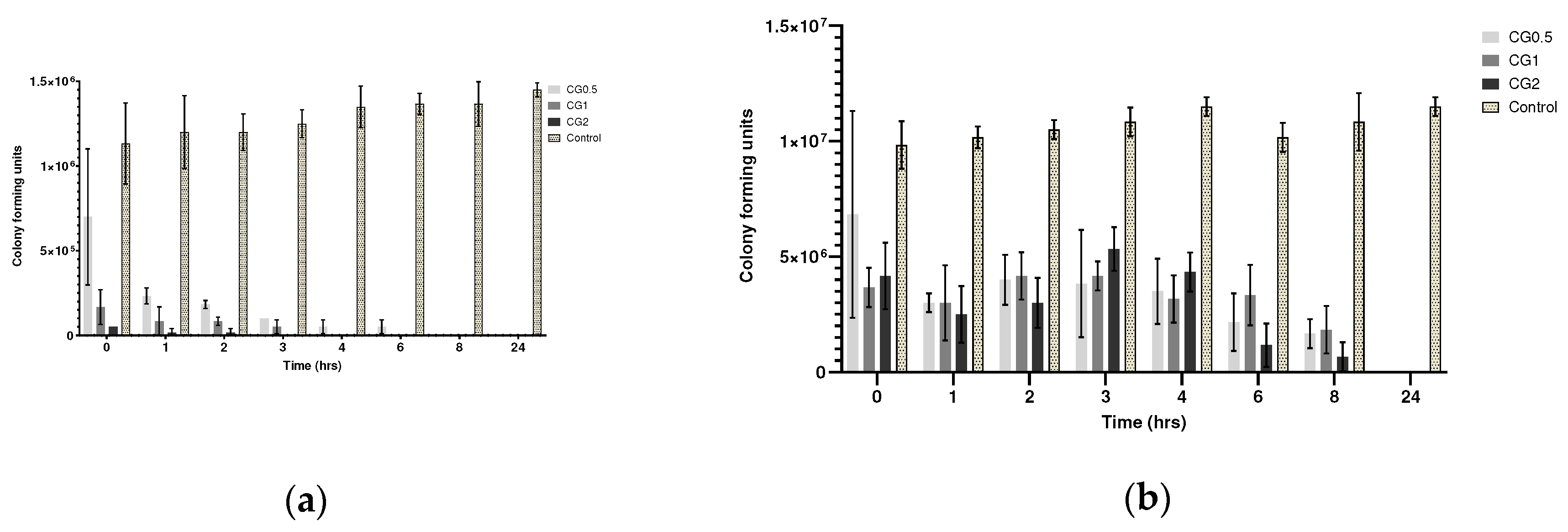

2.5.2. Broth Dilution Assay

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Synthesis of Chitosan Nanoparticles.

4.2.2. In-vitro detection of Gentamicin

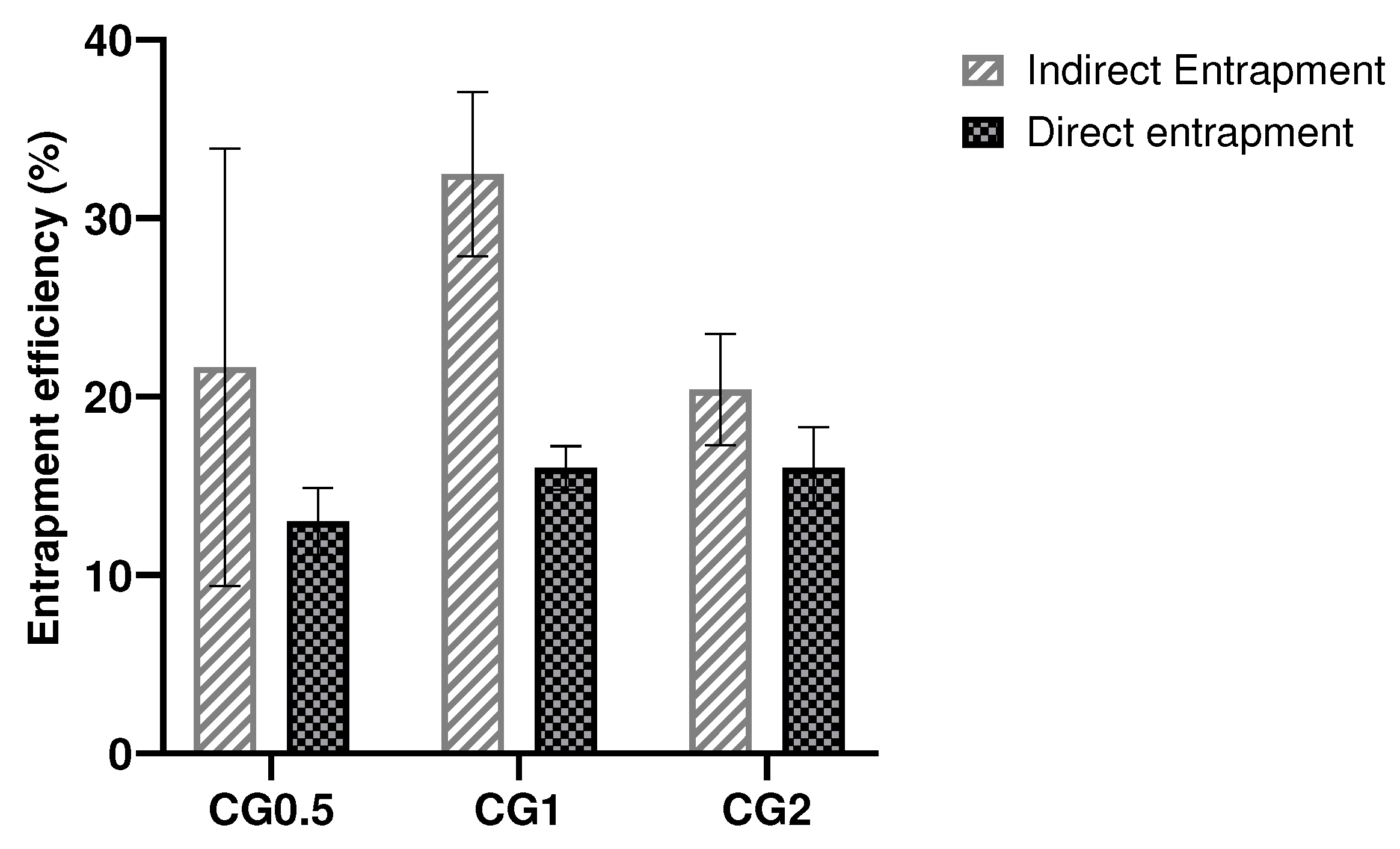

4.2.3. Chitosan nanoparticle Entrapment

4.2.3.1. Indirect entrapment

4.2.3.2. Direct entrapment

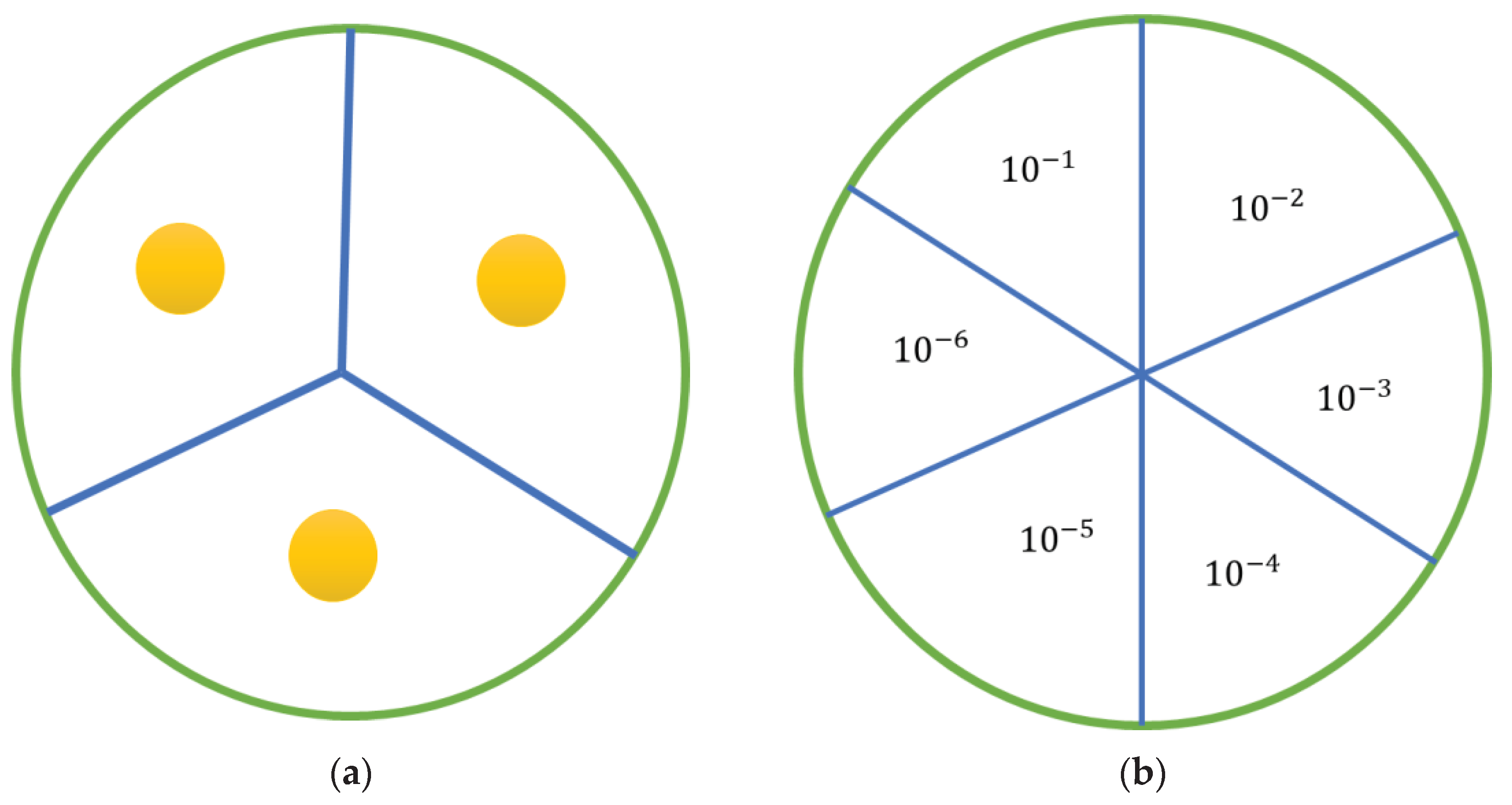

4.2.4. Antimicrobial studies

4.2.4.1. Plating of media

4.2.4.2. Growth of bacterial cultures

4.2.4.3. Zone of Inhibition control Assay

4.2.4.4. Determination of antimicrobial activity of antimicrobial loaded nanoparticles

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puiggalí, J.; Katsarava, R. Chapter 7—Bionanocomposites. In Clay-Polymer Nanocomposites; Jlassi, K., Chehimi, M.M., Thomas, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 239–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.S. 1—Manufacture, types and properties of biotextiles for medical applications. In Biotextiles as Medical Implants; King, M.W., Gupta, B.S., Guidoin, R., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 3–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, N.V.; Kolbe, K.A.; Dresvyanina, E.N.; Grebennikov, S.F.; Dobrovolskaya, I.P.; Yudin, V.E.; Luxbacher, T.; Morganti, P. Effect of Chitin Nanofibrils on Biocompatibility and Bioactivity of the Chitosan-Based Composite Film Matrix Intended for Tissue Engineering. Materials 2019, 12, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, R.C.; Ng, T.B.; Wong, J.H.; Chan, W.Y. Chitosan: An Update on Potential Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5156–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hejazi, R.; Amiji, M. Chitosan-based gastrointestinal delivery systems. J. Control Release 2003, 89, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Tanaka, M.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Chitosan preparations for wounds and burns: Antimicrobial and wound-healing effects. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 857–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Vázquez, M.; Vega-Ruiz, B.; Ramos-Zúñiga, R.; Saldaña-Koppel, D.A.; Quiñones-Olvera, L.F. Chitosan and Its Potential Use as a Scaffold for Tissue Engineering in Regenerative Medicine. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 821279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, M.; Chen, X.G.; Xing, K.; Park, H.J. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and mode of action: A state of the art review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, M.A.; Syeda, J.T.M.; Wasan, K.M.; Wasan, E.K. An Overview of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Its Application in Non-Parenteral Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poth, N.; Seiffart, V.; Gross, G.; Menzel, H.; Dempwolf, W. Biodegradable chitosan nanoparticle coatings on titanium for the delivery of BMP-2. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarudin, M.J.; Cutts, S.M.; Evison, B.J.; Phillips, D.R.; Pigram, P.J. Factors determining the stability, size distribution, and cellular accumulation of small, monodisperse chitosan nanoparticles as candidate vectors for anticancer drug delivery: Application to the passive encapsulation of [(14)C]-doxorubicin. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2015, 8, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershov, K.I.; Rusova, T.V.; Falameeva, O.V.; Sadovoy, M.A.; Aizman, R.I.; Kolosova, N.G. Bone matrix glycosaminoglycans and osteoporosis development in early aging OXYS rats. Adv. Gerontol. 2011, 1, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultankulov, B.; Berillo, D.; Sultankulova, K.; Tokay, T.; Saparov, A. Progress in the Development of Chitosan-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkholy, S.; Yahia, S.; Awad, M.; Elmessiery, M. In vivo evaluation of β-CS/n-HA with different physical properties as a new bone graft material. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2018, 20, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levengood, S.K.L.; Zhang, M. Chitosan-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 3161–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahanta, A.K.; Senapati, S.; Paliwal, P.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Hemalatha, S.; Maiti, P. Nanoparticle-Induced Controlled Drug Delivery Using Chitosan-Based Hydrogel and Scaffold: Application to Bone Regeneration. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellá, M.C.G.; Lima-Tenório, M.K.; Tenório-Neto, E.T.; Guilherme, M.R.; Muniz, E.C.; Rubira, A.F. Chitosan-based hydrogels: From preparation to biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viezzer, C.; Mazzuca, R.; Machado, D.C.; de Camargo Forte, M.M.; Gómez Ribelles, J.L. A new waterborne chitosan-based polyurethane hydrogel as a vehicle to transplant bone marrow mesenchymal cells improved wound healing of ulcers in a diabetic rat model. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 231, 115734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Cheng, Y.; Shi, X.; Zheng, H.; Du, Y.; Xiang, W.; Deng, H. Applications of chitin and chitosan nanofibers in bone regenerative engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, B.; Habib, H.; Abbasi, S.A.; Ihsan, A.; Nasir, H.; Imran, M. Development of Cefotaxime Impregnated Chitosan as Nano-antibiotics: De Novo Strategy to Combat Biofilm Forming Multi-drug Resistant Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 179982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.M.; Hafez, M.M. Enhanced antibacterial effect of ceftriaxone sodium-loaded chitosan nanoparticles against intracellular Salmonella typhimurium. AAPS PharmSciTech 2012, 13, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Cao, J.; Lee, J.; Hlaing, S.P.; Oshi, M.A.; Naeem, M.; Ki, M.H.; Lee, B.L.; Jung, Y.; Yoo, J.W. Bacteria-Targeted Clindamycin Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles: Effect of Surface Charge on Nanoparticle Adhesion to MRSA, Antibacterial Activity, and Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, S.M.; Quinn, D.J.; Ingram, R.J.; Gilmore, B.F.; Donnelly, R.F.; Taggart, C.C.; Scott, C.J. Gentamicin-loaded nanoparticles show improved antimicrobial effects towards Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 4053–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, H.A.K.; Abudayeh, Z.; Abudoleh, S.M.; Alkrad, J.A.; Hussein, M.Z.; Hussein-Al-Ali, S.H. Application of multiple regression analysis in optimization of metronidazole-chitosan nanoparticles. J. Polym. Res. 2019, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safhi, M.; Sivakumar, S.; Jabeen, A.; Zakir, F.; Islam, F.; Barik, B. Chitosan nanoparticles as a sustained delivery of penicillin G prepared by ionic gelation technique. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 8, 1352–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, B.K.; Parikh, R.H.; Aboti, P.S. Development of oral sustained release rifampicin loaded chitosan nanoparticles by design of experiment. J. Drug Deliv. 2013, 2013, 370938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahdestani, S.A.; Shahriari, M.H.; Abdouss, M. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan nanoparticles containing teicoplanin using sol–gel. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenken, K.E.; Smith, J.K.; Skinner, R.A.; Mclaren, S.G.; Bellamy, W.; Gruenwald, M.J.; Spencer, H.J.; Jennings, J.A.; Haggard, W.O.; Smeltzer, M.S. Chitosan coating to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of calcium sulfate-based antibiotic therapy in the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 29, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, R.-j.; Xu, J.-j.; Shen, L.-f.; Gao, J.-q.; Wang, X.-p.; Wang, N.-n.; Shou, D.; Hu, Y. Efficient induction of antimicrobial activity with vancomycin nanoparticle-loaded poly (trimethylene carbonate) localized drug delivery system. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galow, A.M.; Rebl, A.; Koczan, D.; Bonk, S.M.; Baumann, W.; Gimsa, J. Increased osteoblast viability at alkaline pH in vitro provides a new perspective on bone regeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 10, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, E.; Franzblau, S.; Onyuksel, H.; Popescu, C. Preparation of aminoglycoside-loaded chitosan nanoparticles using dextran sulphate as a counterion. J. Microencapsul. 2009, 26, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formulation and Evaluation of Metronidazole Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles. 2016.

- Zhang, H.-l.; Wu, S.-h.; Tao, Y.; Zang, L.-q.; Su, Z.-q. Preparation and Characterization of Water-Soluble Chitosan Nanoparticles as Protein Delivery System. J. Nanomater. 2010, 2010, 898910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lapitsky, Y. Salt-assisted mechanistic analysis of chitosan/tripolyphosphate micro- and nanogel formation. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3868–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobhani, Z.; Mohammadi Samani, S.; Montaseri, H.; Khezri, E. Nanoparticles of Chitosan Loaded Ciprofloxacin: Fabrication and Antimicrobial Activity. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, S.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Moerschbacher, B.M.; Rivera-Rodriguez, G.R. Parameters influencing the size of chitosan-TPP nano- and microparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Atyabi, F.; Dinarvand, R.; Ostad, S.N. Chitosan-Pluronic nanoparticles as oral delivery of anticancer gemcitabine: Preparation and in vitro study. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 1851–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, F.G.; Magalhães, T.C.; Teixeira, N.M.; Gondim, B.L.C.; Carlo, H.L.; Dos Santos, R.L.; de Oliveira, A.R.; Denadai, Â.M.L. Synthesis and characterization of TPP/chitosan nanoparticles: Colloidal mechanism of reaction and antifungal effect on C. albicans biofilm formation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 104, 109885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limsitthichaikoon, S.; Sinsuebpol, C. Electrostatic Effects of Metronidazole Loaded in Chitosan-Pectin Polyelectrolyte Complexes. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 819, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Vinay, C.; Narang, R.; Geeta, A. Comparative mucopenetration ability of metronidazole loaded chitosan and pegylated chitosan nanoparticles. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Hao, S.; Wu, D.; Huang, R.; Xu, Y. Preparation, characterization and in vitro release of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with gentamicin and salicylic acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 85, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Aggarwal, G.; Singla, S.; Arora, R. Transfersomes: A novel vesicular carrier for enhanced transdermal delivery of sertraline: Development, characterization, and performance evaluation. Sci. Pharm. 2012, 80, 1061–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.S.; Woo, P.C.; Luk, W.K.; Yuen, K.Y. Susceptibility testing of Clostridium difficile against metronidazole and vancomycin by disk diffusion and Etest. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razei, A.; Cheraghali, A.M.; Saadati, M.; Fasihi Ramandi, M.; Panahi, Y.; Hajizade, A.; Siadat, S.D.; Behrouzi, A. Gentamicin-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Improve Its Therapeutic Effects on Brucella-Infected J774A.1 Murine Cells. Galen. Med. J. 2019, 8, e1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horváth, G.; Bencsik, T.; Ács, K.; Kocsis, B. Sensitivity of ESBL-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria to Essential Oils, Plant Extracts, and Their Isolated Compounds.

- Henwood, C.J.; Livermore, D.M.; James, D.; Warner, M. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Results of a UK survey and evaluation of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy disc susceptibility test. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 47, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naimi, H.M.; Rasekh, H.; Noori, A.Z.; Bahaduri, M.A. Determination of antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in Staphylococcus aureus strains recovered from patients at two main health facilities in Kabul, Afghanistan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukholm, G.; Mugabe, C.; Azghani, A.O.; Omri, A. Antibacterial activity of liposomal gentamicin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A time-kill study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2006, 27, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galow, A.-M.; Rebl, A.; Koczan, D.; Bonk, S.M.; Baumann, W.; Gimsa, J. Increased osteoblast viability at alkaline pH in vitro provides a new perspective on bone regeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 10, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formulation number | Formulation | Size (nm) | PDI | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C4 | CS 0.5%: TPP 4% | 212.27 ± 19.69 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | -1.80 ± 1.90 |

| C5 | CS 1%: TPP 0.1% | 236. 08 ± 32.05 | 0.30 ± 0.3 | 8.60 ± 2.30 |

| C6 | CS 1%: TPP 1% | 198.28 ± 9.11 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 4.60 ± 2.57 |

| Formulation number | R2 Zero Order | R2 First order | R2 Higuchi Release | Best Fit model |

| CG0.5 | 0.634 | 0.8055 | 0.7502 | First |

| CG1 | 0.8618 | 0.5188 | 0.9366 | Higuchi |

| CG2 | 0.915 | 0.8189 | 0.9739 | Higuchi |

| Drug loading concentration (%w/v) | Formulation number |

|---|---|

| Gentamicin | |

| 0.5 | CG0.5 |

| 1 | CG1 |

| 2 | CG2 |

| Aerobic strains (P. aeruginosa and S. aureus) | |

|---|---|

| Gentamicin concentration plated (mg/ml) | Amount of Gentamicin plated (µg) |

| 0.25 | 12.5 |

| 0.5 | 25 |

| 1 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).