Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

17 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

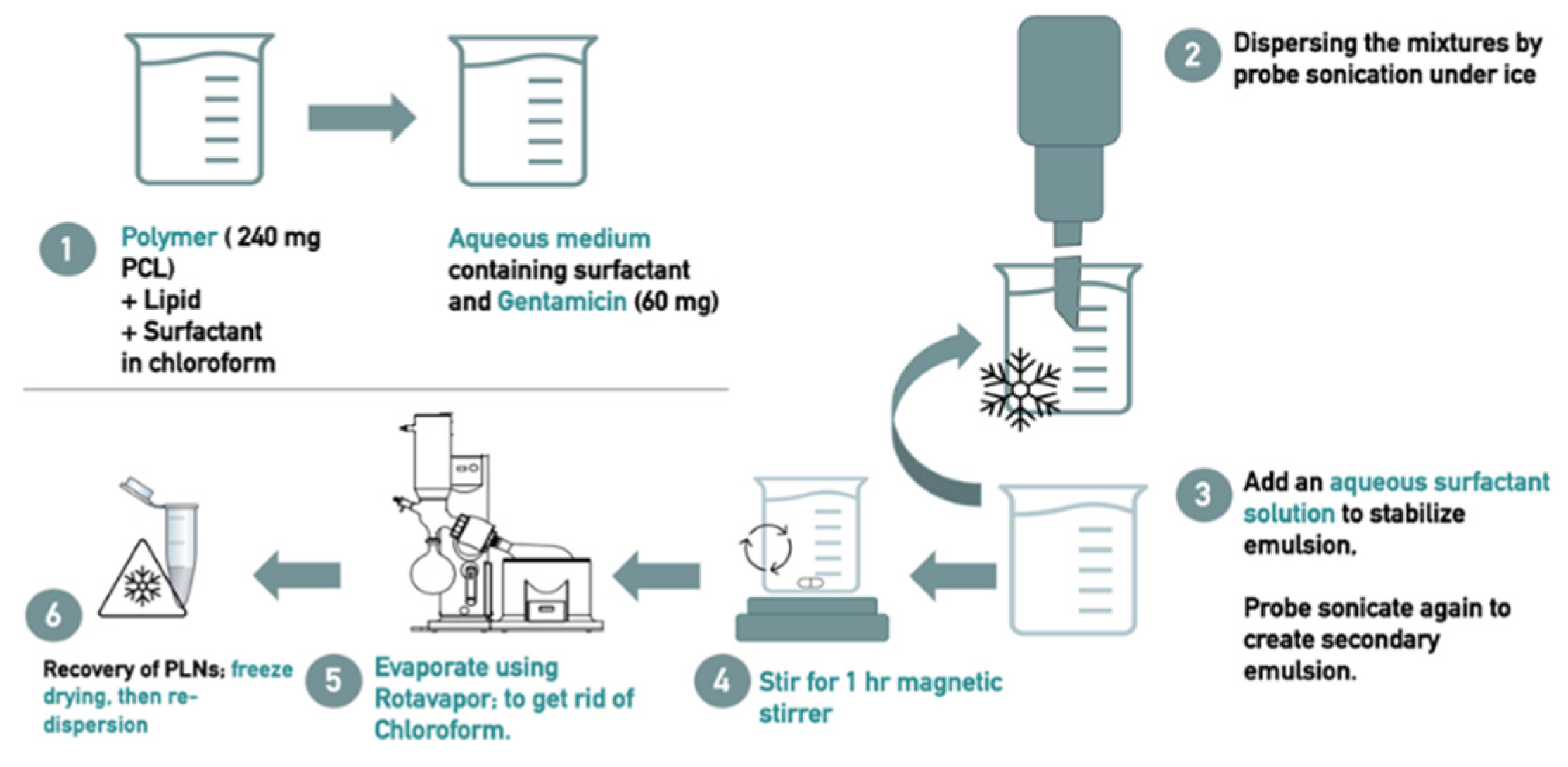

2.2.1. Preparation of PLN Drug Formulation

2.2.2. Evaluation of the Physical Characteristics of the Prepared PLN

- Determination of particle size and Polydispersity index:

- Determination of zeta-potential:

- Particle morphological features:

- Drug loading (DL%) and entrapment efficiency (EE)%

- Physical stability of the prepared PLN:

2.2.3. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity

- Tested bacteria and growth conditions:

- Antibacterial assays

- Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

- 2.

- Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

3. Results

3.1. Formulations and Method Development

3.2. Polymer-Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticle Characterization

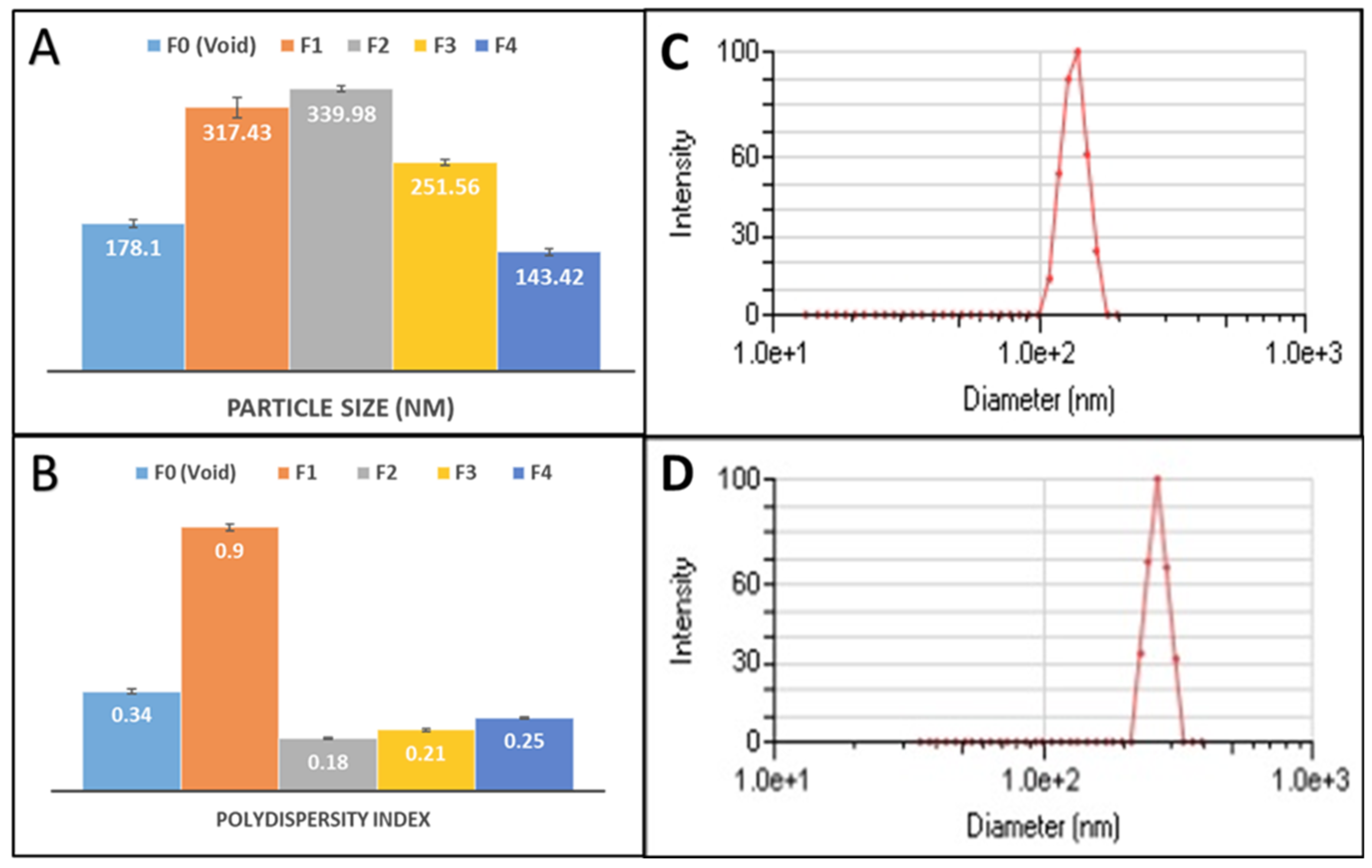

3.2.1. Particle Size and Polydispersity Index

3.2.2. Zeta Potential

3.2.3. Drug Loading (DL%) and Entrapment Efficiency (EE%)

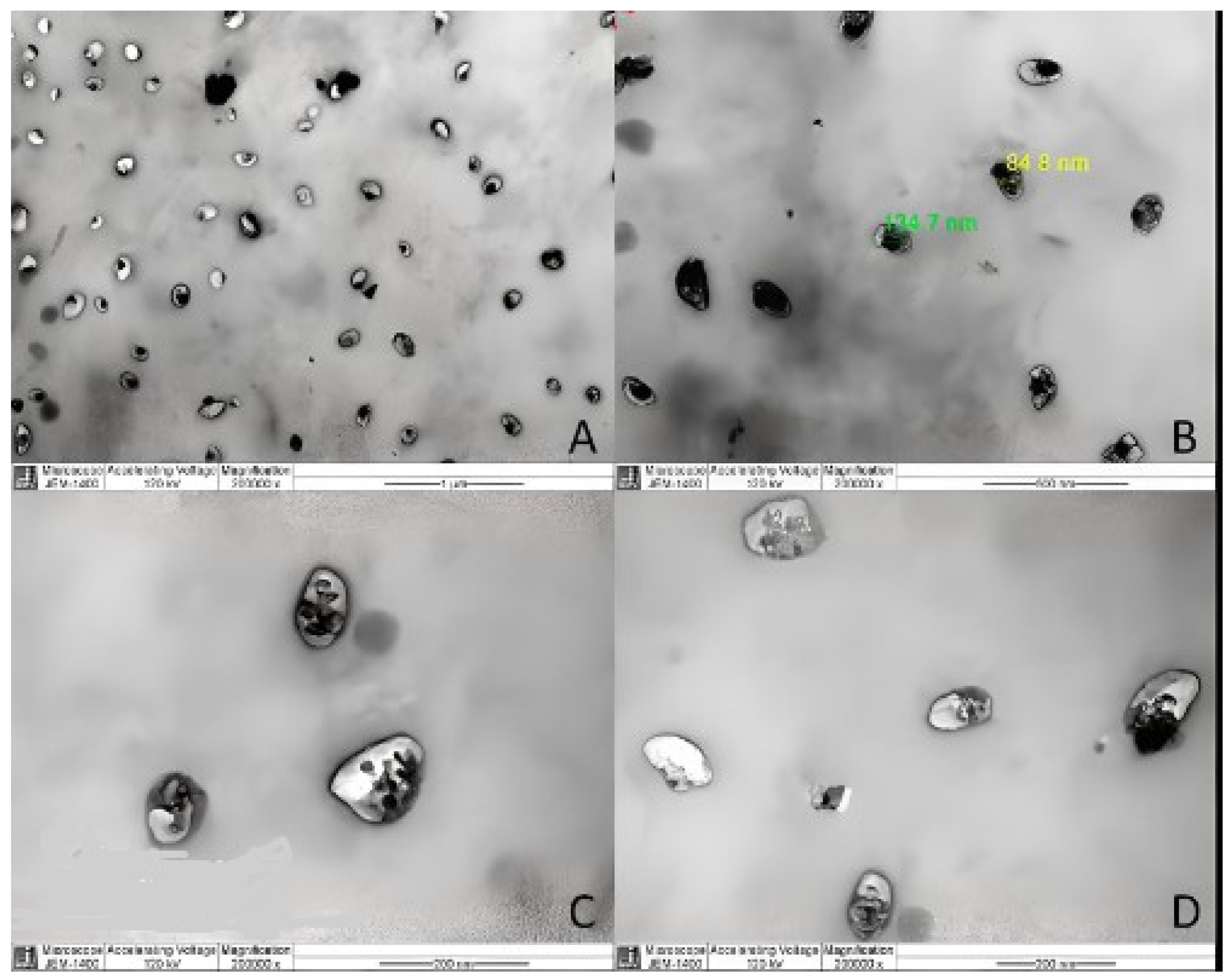

3.2.4. Morphological Analysis

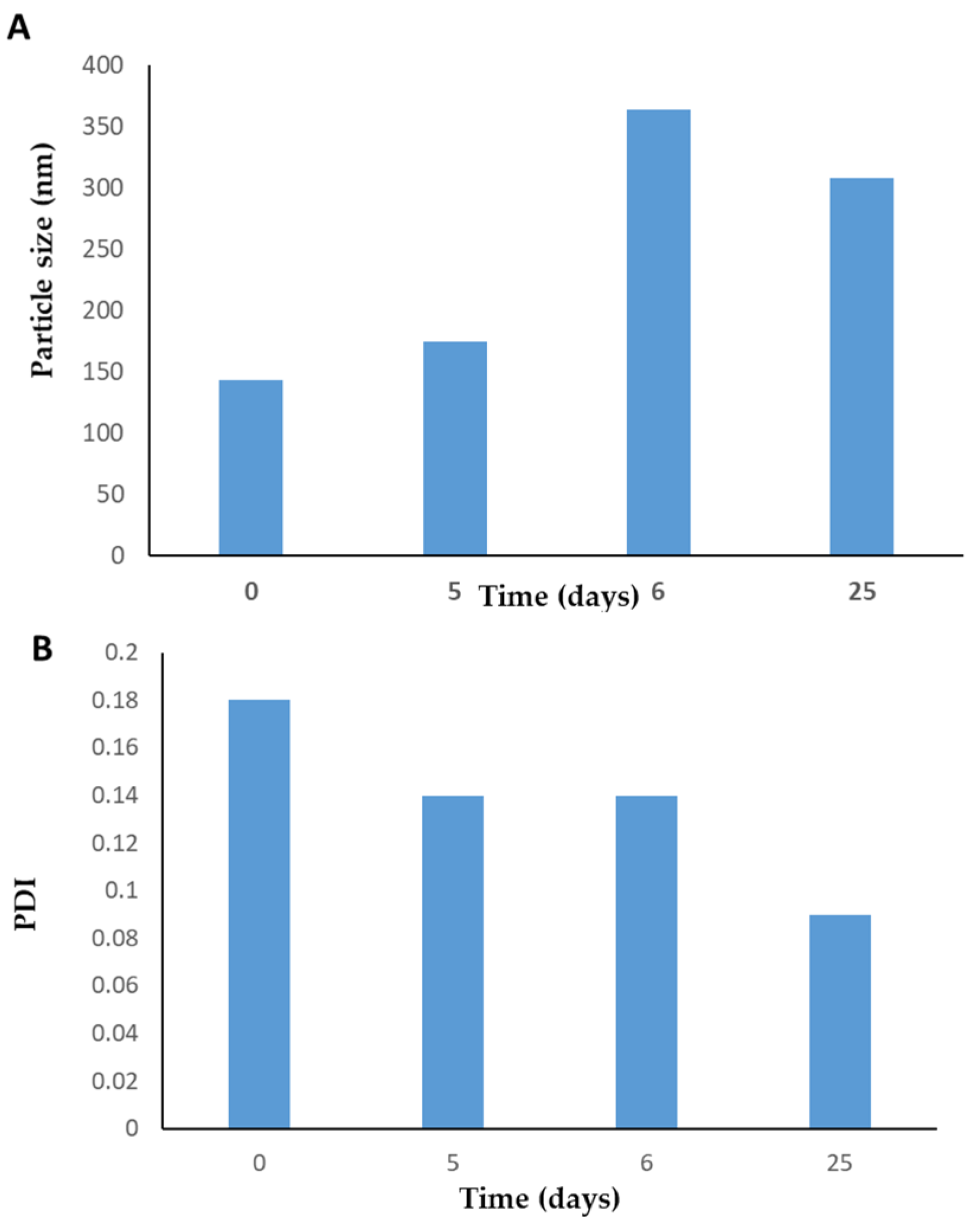

3.3. Physical Stability of PLN

3.4. Antimicrobial Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; et al. ; Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health 2015, 109(7), 309–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19(1), 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. Atlanta: CDC; 2013. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf (accessed on 16-1-2025).

- Antimicrobial Resistance. WHO; 2023; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (Accessed 16-1-2025).

- Chinemerem Nwobodo, D.; Ugwu, M.C.; Oliseloke Anie, C.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Chinedu Ikem, J.; Victor Chigozie, U.; Saki, M. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J Clin Lab Anal 2022, 36(9), e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadgir, C.A.; Biswas, D.A. Antibiotic Resistance and Its Impact on Disease Management. Cureus 2023, 15(4), e38251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepa,s V.; López, Y.; Muñoz E, Rolo D, Ardanuy C, Martí S, et al. Relationship between Biofilm Formation and Antimicrobial Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Microb Drug Resist. 2019 Jan 1;25(1):72–9.

- Sharma S, Mohler J, Mahajan, S.D.; Schwartz, S.A.; Bruggemann, L.; Aalinkeel, R. Microbial Biofilm: A Review on Formation, Infection, Antibiotic Resistance, Control Measures, and Innovative Treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11(6), 1614. [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Geesey, G.G.; Cheng, K.J. How bacteria stick. Sci Am 1978, 238, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S.; Greenberg, E.P. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999, 284, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høiby, N.; Ciofu, O.; Johansen, H.K.; Song, Z.J.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø.; et al. The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. Int J Oral Sci 2011, 3(2), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelis, C.; Grohmann, E. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12(2), 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.M.; Serio, A.W.; Kane, T.R.; Connolly, L.E. Aminoglycosides: An overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016, 6(6), a027029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germovsek, E.; Barker, C.I.; Sharland, M. What do i need to know about aminoglycoside antibiotics? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2017, 102(2), 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernd, B.; Cooper, M.A. Aminoglycosides antibiotics in the 21st century. ACS Chemical Biology 2013, 8(1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Talaska, A.E.; Schacht, J. New developments in aminoglycoside therapy and ototoxicity. Hear Res. [CrossRef]

- Streetman, D.S.; Nafziger, A.N.; Destache, C.J.; Bertino, A.S. Jr. Individualized pharmacokinetic monitoring results in less aminoglycoside-associated nephrotoxicity and fewer associated costs. Pharmacotherapy 2001, 21, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fausti, S.A.; Frey, R.H.; Henry, J.A.; Olson, D.J.; Schaffer, H.I. Early detection of ototoxicity using high-frequency, tone burst-evoked auditory brainstem responses. J Am Acad Audiol 1992, 3, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabourian, P.; Yazdani, G.; Ashraf, S.S.; Frounchi, M.; Mashayekhan, S.; Kiani, S.; et al. Effect of Physico-Chemical Properties of Nanoparticles on Their Intracellular Uptake. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelperina, S.; Kisich, K.; Iseman, M.D.; Heifets, L. The potential advantages of nanoparticle drug delivery systems in chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 172(12), 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, J. K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L. F.; Campos, E. V. R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M. D. P.; Acosta-Torres, L. S.; Diaz-Torres, L. A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M. K.; Sharma, S.; Habtemariam, S.; Shin, H. S. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, A.E.B.; Albekairy, A.; Alkatheri, A.; Sharma, R.K. Anticancer-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles: high potential advancement in chemotherapy. Digest J of Nanomat and Biostructures 2013, 8(2), 905 – 916.

- Rajpoot, K. Solid lipid nanoparticles: a promising nanomaterial in drug delivery. Curr Pharm Des 2019, 25(37), 3943–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers as novel drug delivery systems: applications, advantages and disadvantages. Res Pharm Sci. [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.H.; Mäder, K.; Gohla, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery – a review of the state of the art. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2000, 50(1), 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljihani, S.A.; Alehaideb, Z.; Alarfaj, R.E.; Alghoribi, M.F.; Akiel, M.A.; Alenazi, T.H.; Al-Fahad, A.J.; Al Tamimi, S.M.; Albakr, T.M.; Alshehri, A.; Alyahya, S.M.; Yassin, A.E.B.; Halwani, M.A. Enhancing azithromycin antibacterial activity by encapsulation in liposomes/liposomal-N-acetylcysteine formulations against resistant clinical strains of Escherichia coli. Saudi J Biol Sci 2020, 27(11), 3065–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpe, L.; Catalano, M.G.; Cavalli, R.; Ugazio, E.; Bosco, O.; Canaparo, R.; Muntoni, E.; Frairia, R.; Gasco, M.R.; Eandi, M.; Zara, G.P. Cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs incorporated in solid lipid nanoparticles on HT-29 colorectal cancer cell line. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2004, 58(3), 673–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, L.; Serpe, L.; Muntoni, E.; Zara, G.; Trotta, M.; Gallarate, M. Methotrexate-loaded SLNs prepared by coacervation technique: in vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011, 6(9), 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.; Daear, W.; Löbenberg, R.; Prenner, E. J. Overview of the preparation of organic polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery based on gelatine, chitosan, poly ( d, l -lactide-co-glycolic acid) and polyalkylcyanoacrylate. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. [CrossRef]

- El-say, K. M.; El-sawy, H. S. Polymeric nanoparticles: Promising platform for drug delivery. Int J Pharm 2017, 528, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallan, S.S.; Kaur, P.; Kaur, V.; Mishra, N.; Vaidya, B. Lipid polymer hybrid as emerging tool in nanocarriers for oral drug delivery. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2016, 44(1), 334–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivadasan, D.; Sultan, M.H.; Madkhali, O.; Almoshari, Y.; Thangavel, N. Polymeric Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticles (PLNs) as Emerging Drug Delivery Platform-A Comprehensive Review of Their Properties, Preparation Methods, and Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13(8), 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chan, J.M.; Gu, F.X.; Rhee, J.W.; Wang, A.Z.; Radovic-Moreno, A.F.; et al. Self-assembled lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles: A robust drug delivery platform. ACS Nano 2008, 2(8), 1696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R. J.; Keating, G. M. Aminoglycosides. In Schwartz, L.B., Sutcliffe, A.I. (Eds.), Antibiotics: Discovery and development, Springer International Publishing: New York City, USA, 2017; pp. 45-60.

- Cheow, W.S.; Hadinoto, K. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles with rhamnolipid triggered release capabilities as anti-biofilm drug delivery vehicles. Particuology 2012, 1, 327- 333. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927775710004954.

- Omer, M.E.; Halwani, M.; Alenazi, R.M.; Alharbi, O.; Aljihani, S.; Massadeh, S.; Al Ghoribi, M.; Al Aamery, M.; Yassin, A. E. Novel Self-Assembled Polycaprolactone–Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticles Enhance the Antibacterial Activity of Ciprofloxacin. SLAS TECHNOLOGY: Translating Life Sciences Innovation. [CrossRef]

- CLSI. (2017). M100-S27: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (27th ed.). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (ESCMID). Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterial agents by broth dilution. Clin Microbiol Infect.

- Bolourchian, N.; Shafiee Panah, M. The Effect of Surfactant Type and Concentration on Physicochemical Properties of Carvedilol Solid Dispersions Prepared by Wet Milling Method. Iran J Pharm Res 2022, 21(1), e126913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitayama, Y.; Takigawa, S.; Harada, A. Effect of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Concentration and Chain Length on Polymer Nanogel Formation in Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization. Molecules 2023, 28(8), 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.; Yeğen, G.; Aksu, B.; İlem-Özdemir, D. Preparation and Evaluation of Poly(lactic acid)/Poly(vinyl alcohol) Nanoparticles Using the Quality by Design Approach. ACS Omega 2022, 7(38), 33793–33807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masarudin, M.J.; Cutts, S.M.; Evison, B.J.; Phillips, D.R.; Pigram, P.J. Factors determining the stability, size distribution, and cellular accumulation of small, monodisperse chitosan nanoparticles as candidate vectors for anticancer drug delivery: application to the passive encapsulation of [14C]-doxorubicin. Nanotechnol Sci Appl 2015, 8, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, V.; Hawe, A.; Jiskoot, W. Critical evaluation of Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) by NanoSight for the measurement of nanoparticles and protein aggregates. Pharm Res 2010, 27(5), 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee; S.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Size-Dependent Catalytic Activity of PVA-Stabilized Palladium Nanoparticles in p-Nitrophenol Reduction: Using a Thermoresponsive Nanoreactor. ACS Omega 2021, 6(32), 20746-20757. [CrossRef]

- Xiao-ting, C.; Wang, T. Preparation and characterization of atrazine-loaded biodegradable PLGA nanospheres. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2019, 18(5), 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei, M.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, M.R. . Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10(2), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenthamara, D.; Subramaniam, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.G.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Essa, M.M.; Lin, F.H.; Qoronfleh, M.W. Therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles and routes of administration. Biomater Res 2019, 23, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Kou, J.; Sun, C.; Li, H. Aggregation mechanism of colloidal kaolinite in aqueous solutions with electrolyte and surfactants. PLoS One, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, M.L.; Meireles, M.; Cabane, B.; Guizard, C. 2009; 92. [CrossRef]

- Pulingam, T.; Foroozandeh, P.; Chuah, J-A. ; Sudesh, K. Exploring Various Techniques for the Chemical and Biological Synthesis of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(3), 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohrey, S.; Chourasiya, V.; Pandey, A. Polymeric nanoparticles containing diazepam: preparation, optimization, characterization, in-vitro drug release and release kinetic study. Nano Convergence 2016, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkholief, M.; Kalam, M.A.; Anwer, M.K.; Alshamsan, A. Effect of Solvents, Stabilizers and the Concentration of Stabilizers on the Physical Properties of Poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) Nanoparticles: Encapsulation, In Vitro Release of Indomethacin and Cytotoxicity against HepG2-Cell. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14(4), 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Dong, Q.; Wang, M.; Shi, L.; Wu, Y.; Yu, X.; Shi, Y.; Shan, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, X.; Gu, T.; Chen, Y.; Kong, W. Preparation, characterization, and pharmacodynamics of exenatide-loaded poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2010, 58(11), 1474–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M.A. In vitro evaluation of polyisobutylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles as a controlled drug carrier for theophylline. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 1995, 21(20), 2371–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, K.R.; Salve, R.; Narwade, M.; Sheikh, A.; Kesharwani, P.; Gajbhiye, V. Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: a custom-tailored next-generation approach for cancer therapeutics. Mol Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.H.; Moni, S.S.; Madkhali, O.A.; Bakkari, M.A.; Alshahrani, S.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Mohan, S.; Ghazwani, M.; Bukhary, H.A.; Almoshari, Y.; Salawi, A.; Alshamrani, M. Characterization of cisplatin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles and rituximab-linked surfaces as target-specific injectable nano-formulations for combating cancer. Sci Rep 2022, 12(1), 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Bui, T.A.; Yang, X.; Aksoy, Y.; Goldys, E.M.; Deng, W. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Drug/Gene Delivery: An Overview of the Production Techniques and Difficulties Encountered in Their Industrial Development. ACS Mater Au 2023, 3(6), 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayan, GÖ; Kayan, A. Polycaprolactone Composites/Blends and Their Applications Especially in Water Treatment. Chem Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Musielak, E.; Feliczak-Guzik, A.; Nowak, I. Optimization of the Conditions of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) Synthesis. Molecules 2022, 27(7), 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, H.; Hernández-Parra, H.; Bernal-Chávez, S.A.; Prado-Audelo, M.L.D.; Caballero-Florán, I.H.; Borbolla-Jiménez, F.V.; González-Torres, M. ’; Magaña, J.J.; Leyva-Gómez, G. Non-Ionic Surfactants for Stabilization of Polymeric Nanoparticles for Biomedical Uses. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14(12), 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Pan, Z.; Fan, L.; Zhong, Y.; Pang, R.; Su, Y. Effect of Three Different Amino Acids Plus Gentamicin Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Drug Resist 2023, 16, 4741–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Lu, W.; Gu, X.; Lin, Q. Efficacy of Gentamicin-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Against Staphylococcus aureus Internalized in Osteoblasts. Microb Drug Resist 2024; 30(5), 196-202. [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, S.M.; Quinn, D.J.; Ingram, R.J.; Gilmore, B.F.; Donnelly, R.F.; Taggart, C.C.; Scott, C.J. Gentamicin-loaded nanoparticles show improved antimicrobial effects towards Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Int J Nanomed 2012; 7, 4053-4063. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakeem, M.A.; Abdel Maksoud, A.I.; Aladhadh, M.A.; Almuryif, K.A.; Elsanhoty, R.M.; Elebeedy, D. Gentamicin-Ascorbic Acid Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Improved In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Minimized Cytotoxicity. Antibiotics (Basel), 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangari, A.; Salouti, M.; Heidari, Z.; Kazemizadeh, A.R.; Safari, A.A. Development of gentamicin-gold nanospheres for antimicrobial drug delivery to Staphylococcal infected foci. Drug Deliv 2013, 20, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanta, B.; Chakraborty, A.; Selvara, S.; Roy, A. Bactericidal effect of gentamicin conjugated gold nanoparticles. Micro Nano Lett 2020, 15, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, R.R.; Alkhulaifi, M.M.; Al Jeraisy, M.; Albekairy, A.M.; Ali, R.; Alrfaei, B.M.; Ehaideb, S.N.; Al-Asmari, A.I.; Qahtani, S.A. ; Halwani A, Yassin, A.E.B.; Halwani, M.A.. Enhancing Gentamicin Antibacterial Activity by Co-Encapsulation with Thymoquinone in Liposomal Formulation. Pharmaceutics, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki Dizaj, S.; Lotfipour, F.; Barzegar-Jalali, M.; Zarrintan, M.H.; Adibkia, K. Physicochemical characterization and antimicrobial evaluation of gentamicin-loaded CaCO3 nanoparticles prepared via microemulsion method. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2016, 35, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadowska, U.; Brzychczy-Włoch, M.; Pamuła, E. Gentamicin loaded PLGA nanoparticles as local drug delivery system for the osteomyelitis treatment. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2015, 17, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Formula Code | Drug | Polymer | Lipids | Primary Surfactant and co-surfactant | Secondary Surfactant | |||

| Gen | PCL | Dyansan | SA | Tween 80 | Span 80 | PVA | Tween 80 | |

| F0 (Void) * | 0 | 240 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 50 mg | 50 mg | 15 mL (1%) | X |

| F1 | 5 mg | 150 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 50 mg | X | 30 mL (1%) |

| F2 | 5 mg | 150 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 50 mg | 40mL (1.5%) | X |

| F3 | 40 mg | 150 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 50 mg | 40 mL (1%) | X |

| F4 | 60 mg | 240 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 50 mg | 50 mg | 15 ml (1%) | X |

| Formulation | Drug:Polymer ratio | Mean particle size (nm) (Mean ± SD) | PDI | ZetaPotential (mV) | EE % | DL% |

| F0 (Void) | - | 178.1 (± 4.50) | 0.34 | - | ||

| F1 | 1:30 | 317.43(±11.85) | 0.9 | - 38.0 | 1.7% | 0.04% |

| F2 | 1:30 | 339.98 (± 3.81) | 0.18 | - 38.1 | 2.4% | 0.06% |

| F3 | 1:3.75 | 251.56 (± 3.14) | 0.21 | -11.9 | 4.8% | 0.8% |

| F4 | 1:4 | 143.42 (± 3.69) | 0.25 | - 37.9 | 42.1% | 7.2% |

| No. | Bacteria |

AST Profile |

Free GEN (mg/L) |

F4 Formula (mg/L) |

||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |||

| 1 | Staphylococcus aureusATCC 29213 | Susceptible | 2 | 4 | 0.78 | 1.56 |

| 2 | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus MRSA-59 | Resistant | 256 | 512 | 3.125 | 3.125 |

| 3 | MRSA-60 | Susceptible | 2 | 4 | 1.56 | 3.125 |

| 4 | Escherichia coliATCC 25922 | Susceptible | 2 | 4 | 1.56 | 3.125 |

| 5 | E. coliEC-157 | Susceptible | 2 | 4 | 1.56 | 3.125 |

| 6 | E. coliEC-219 | Resistant | 8 | 16 | 3.125 | 6.25 |

| 7 | Pseudomonas aeruginosaPA-78 | Susceptible | 8 | 16 | 1.56 | 3.125 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).