Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

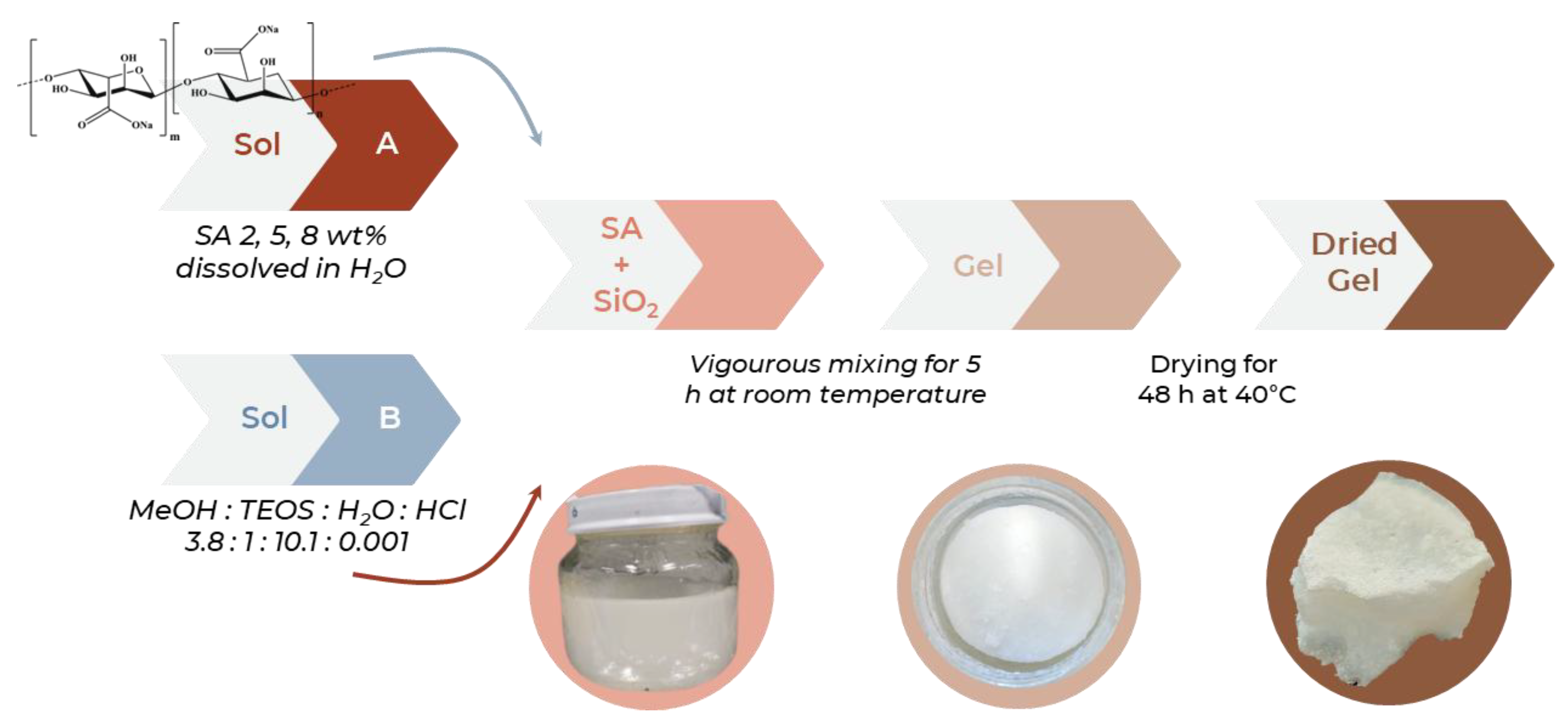

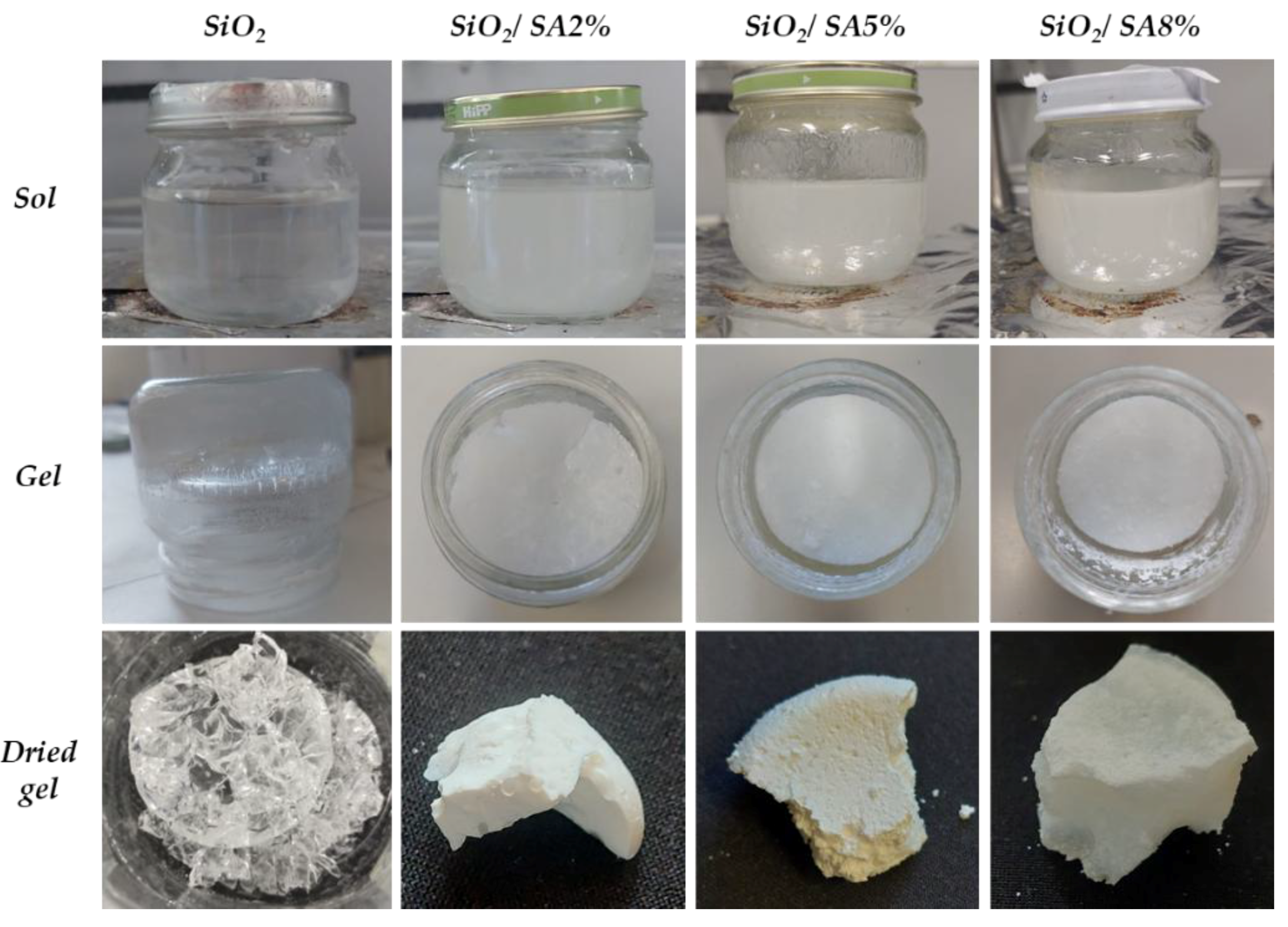

2.1. Sol-Gel Synthesis

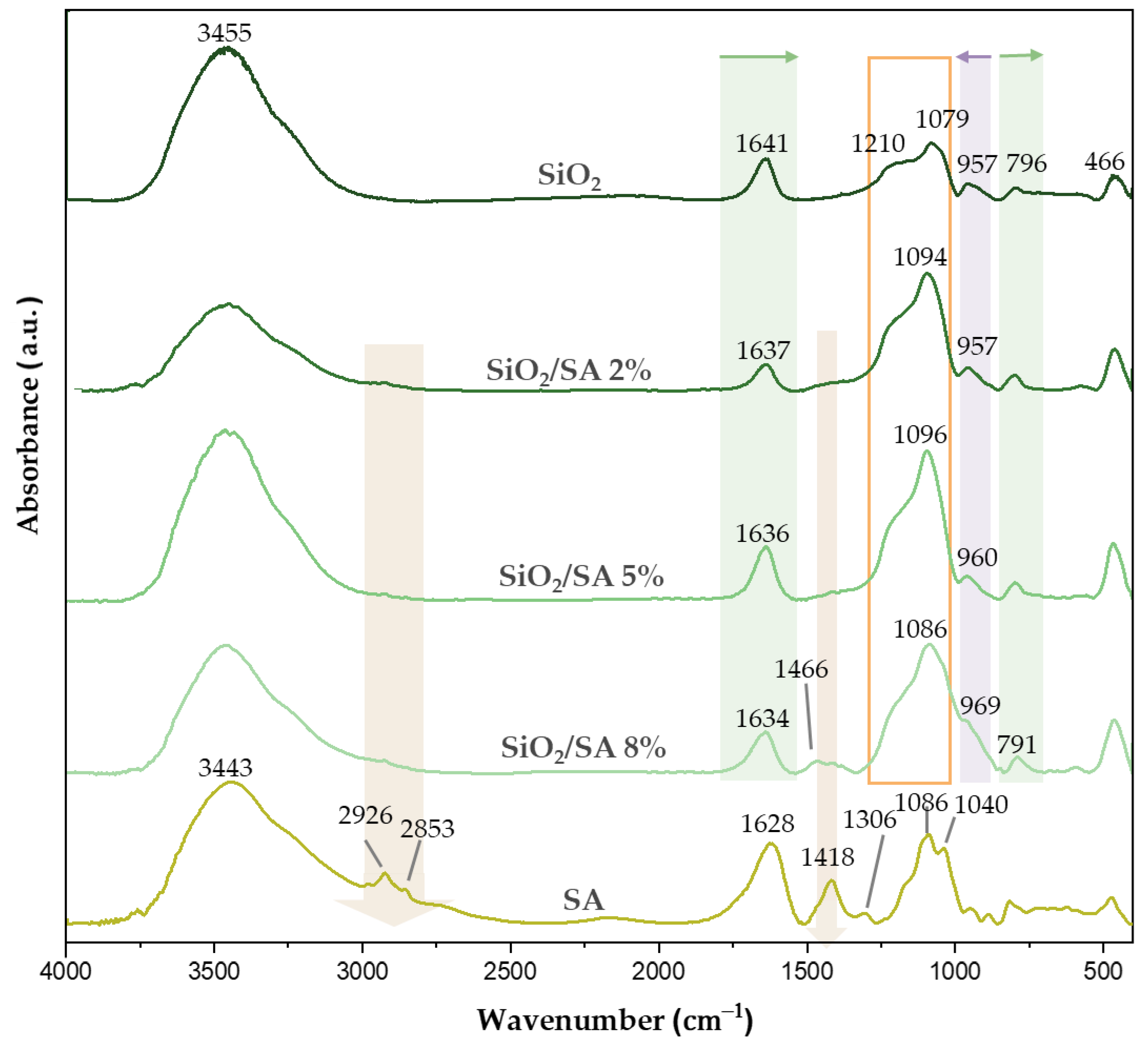

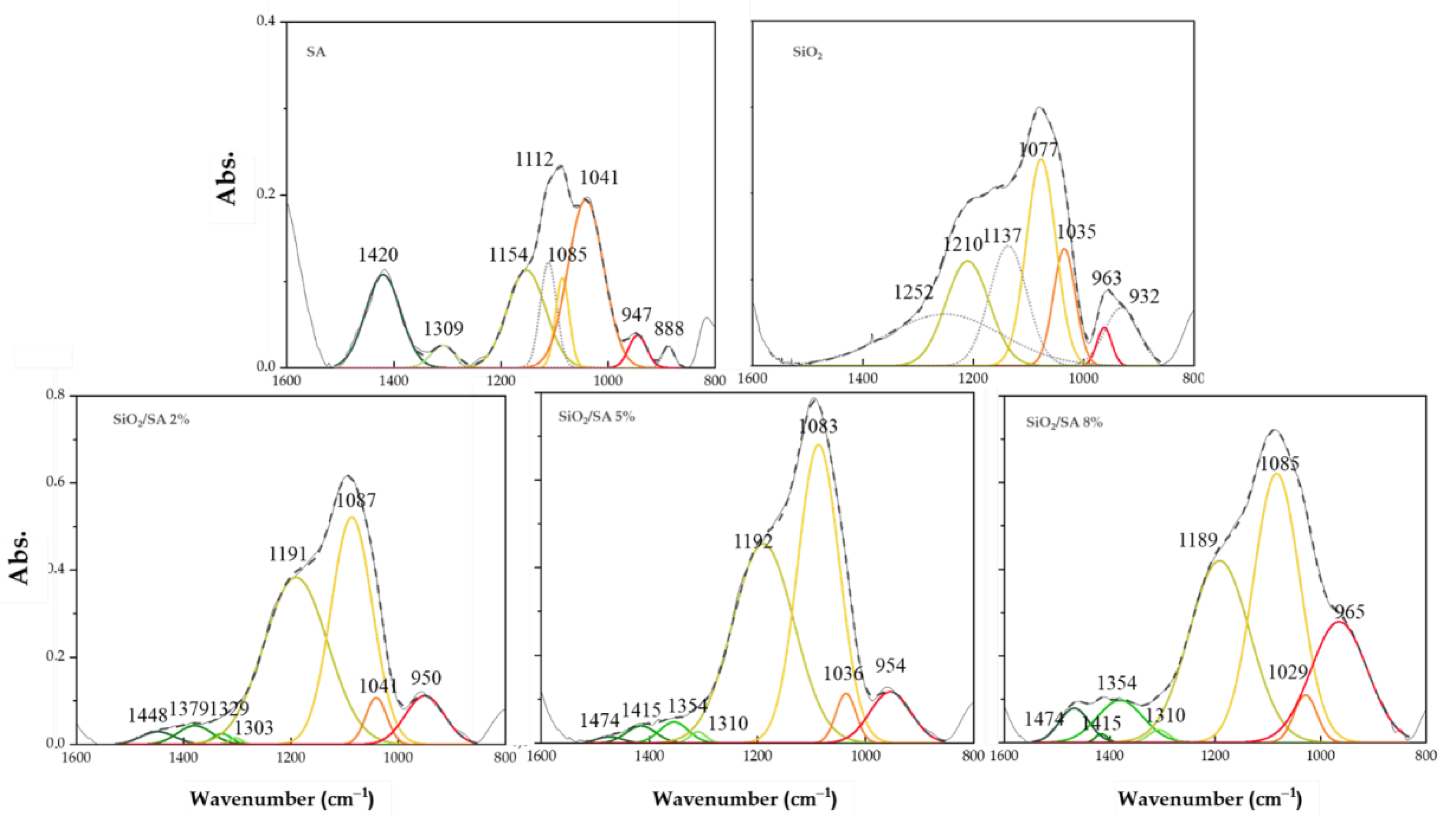

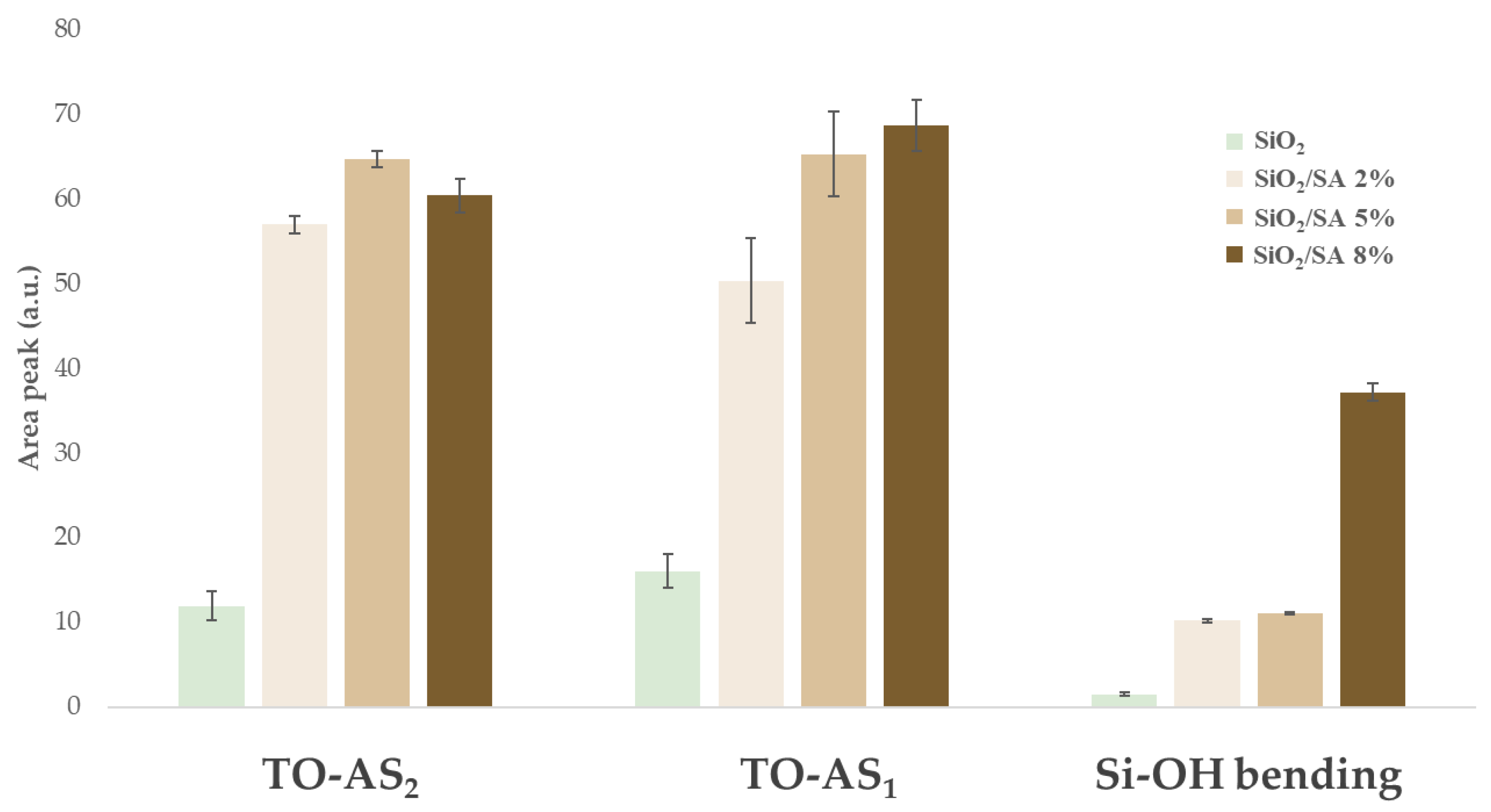

2.2. FTIR Analysis

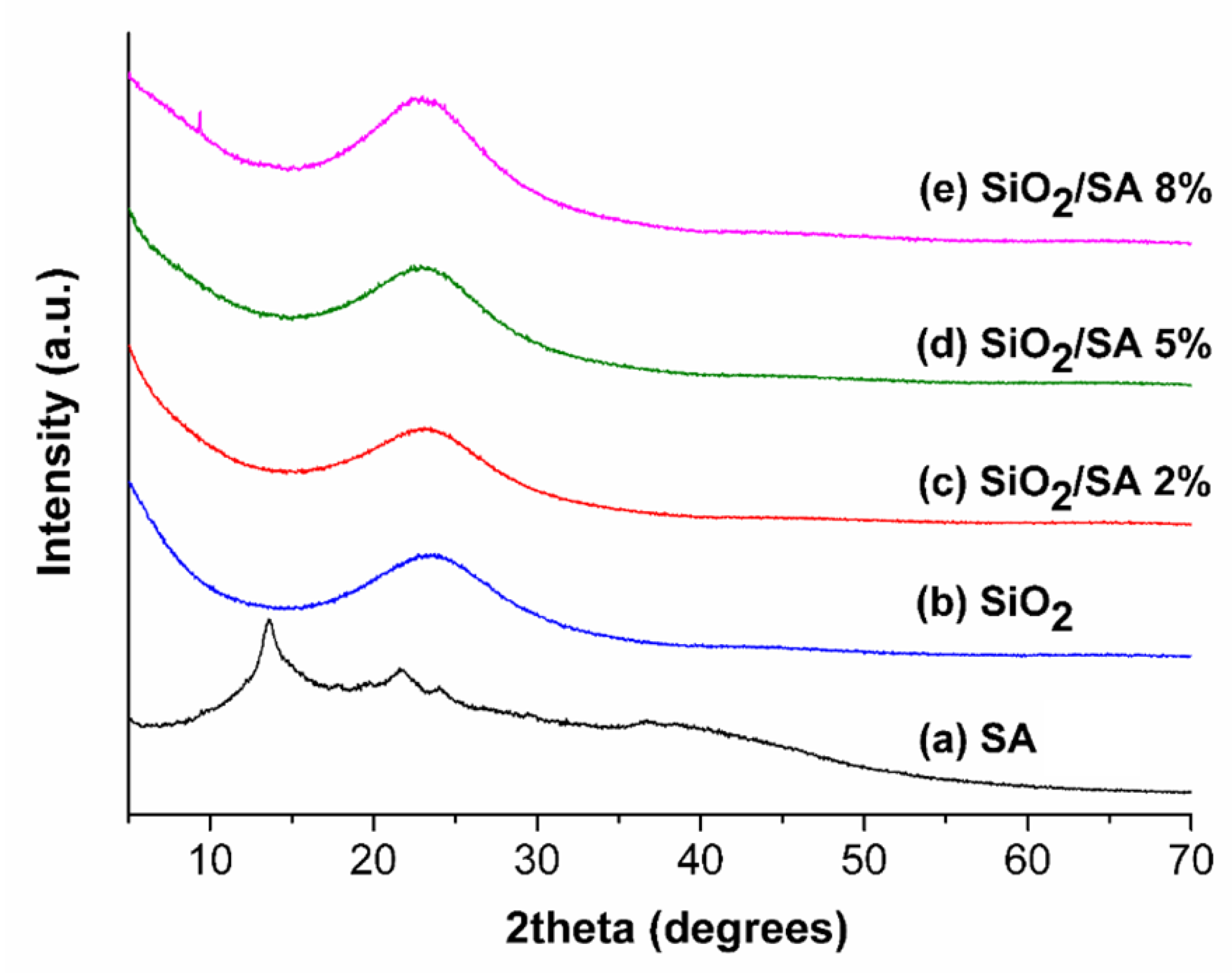

2.3. XRD Analysis

2.4. BET Study

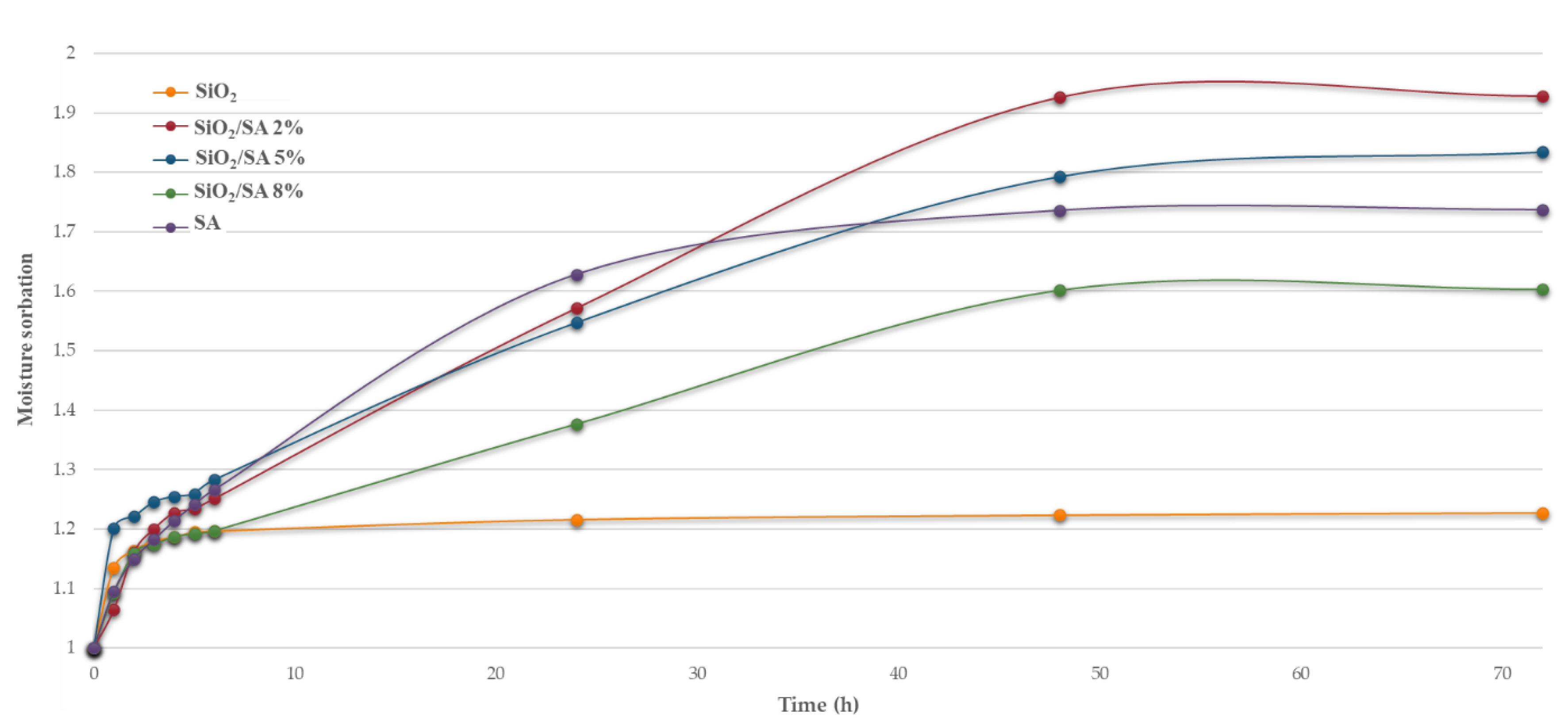

2.5. Moisture Sorption Analysis

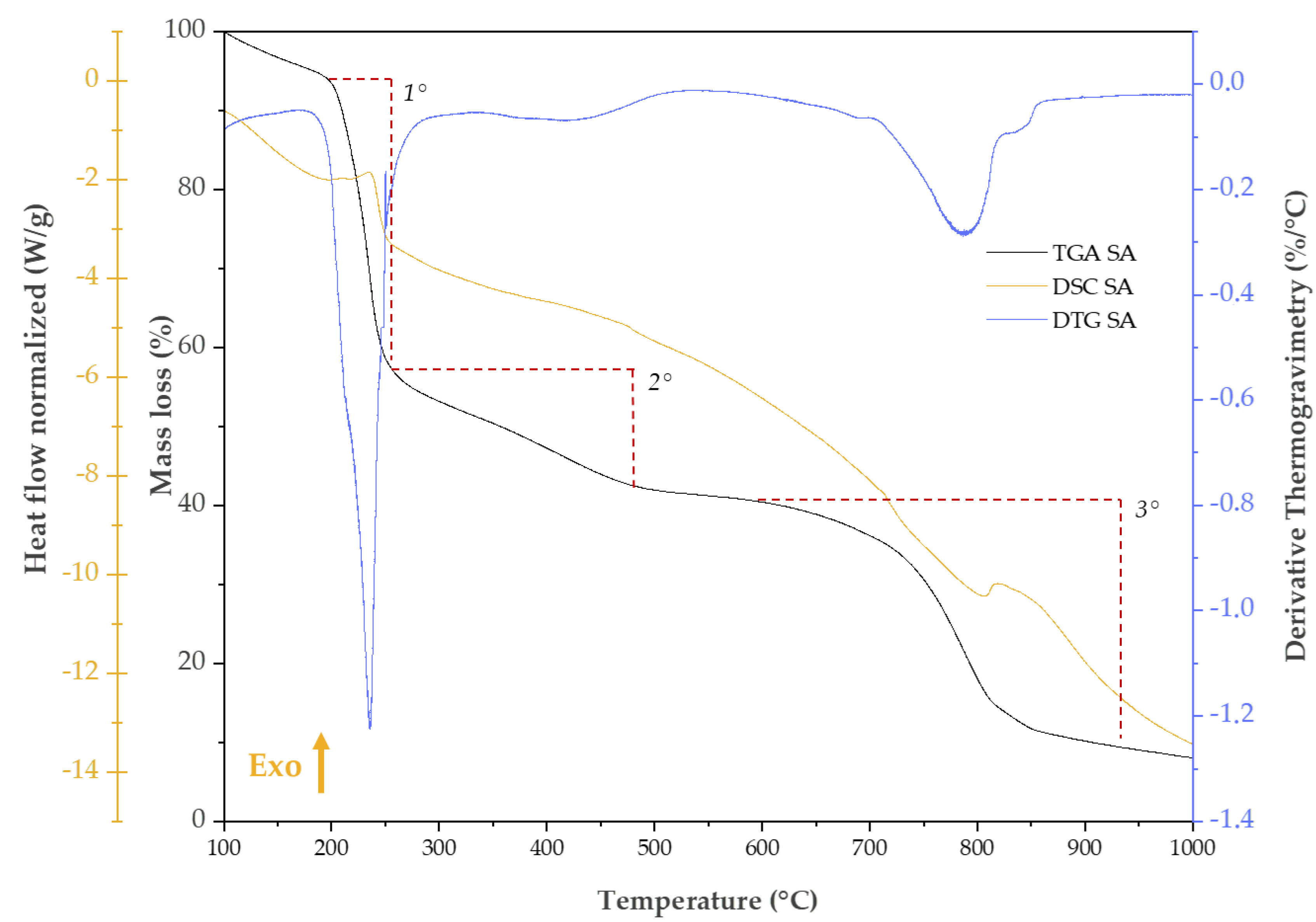

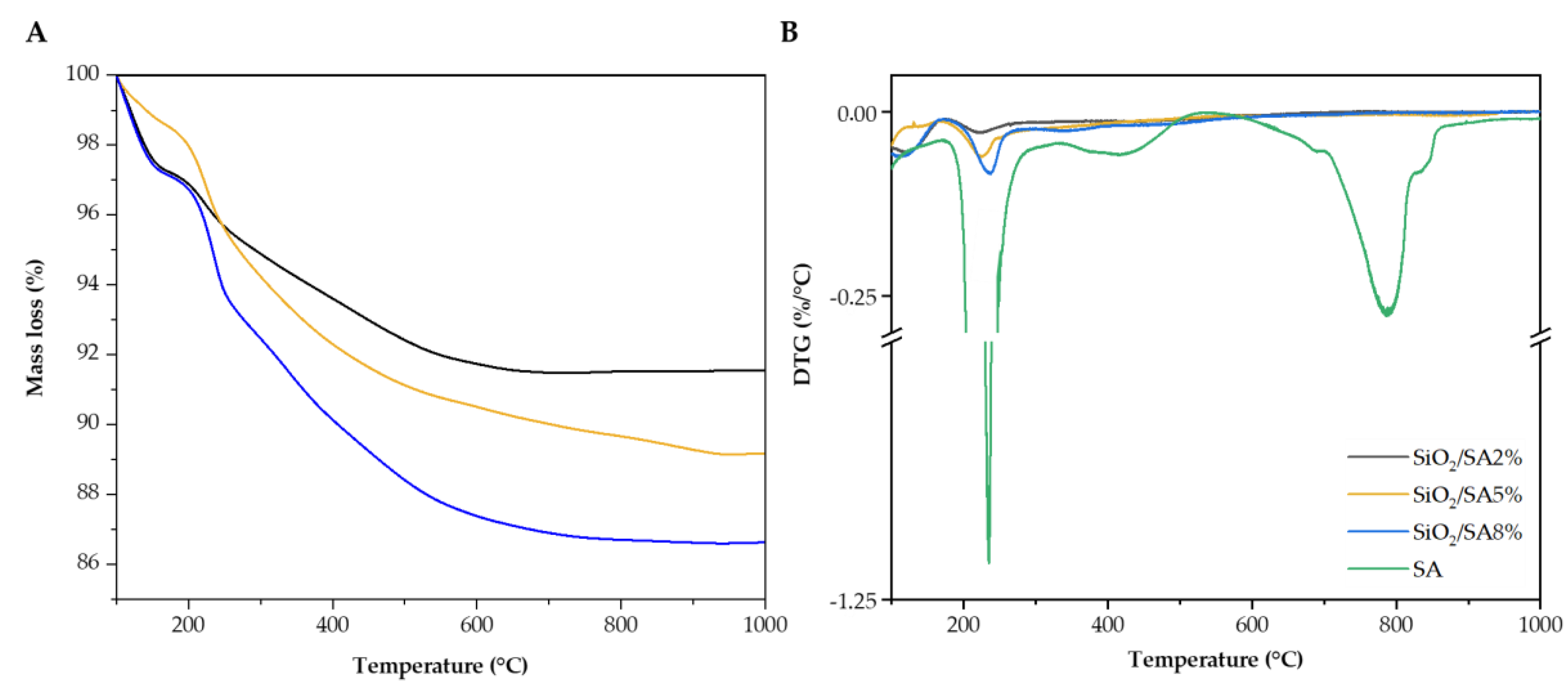

2.5. Thermal Analysis

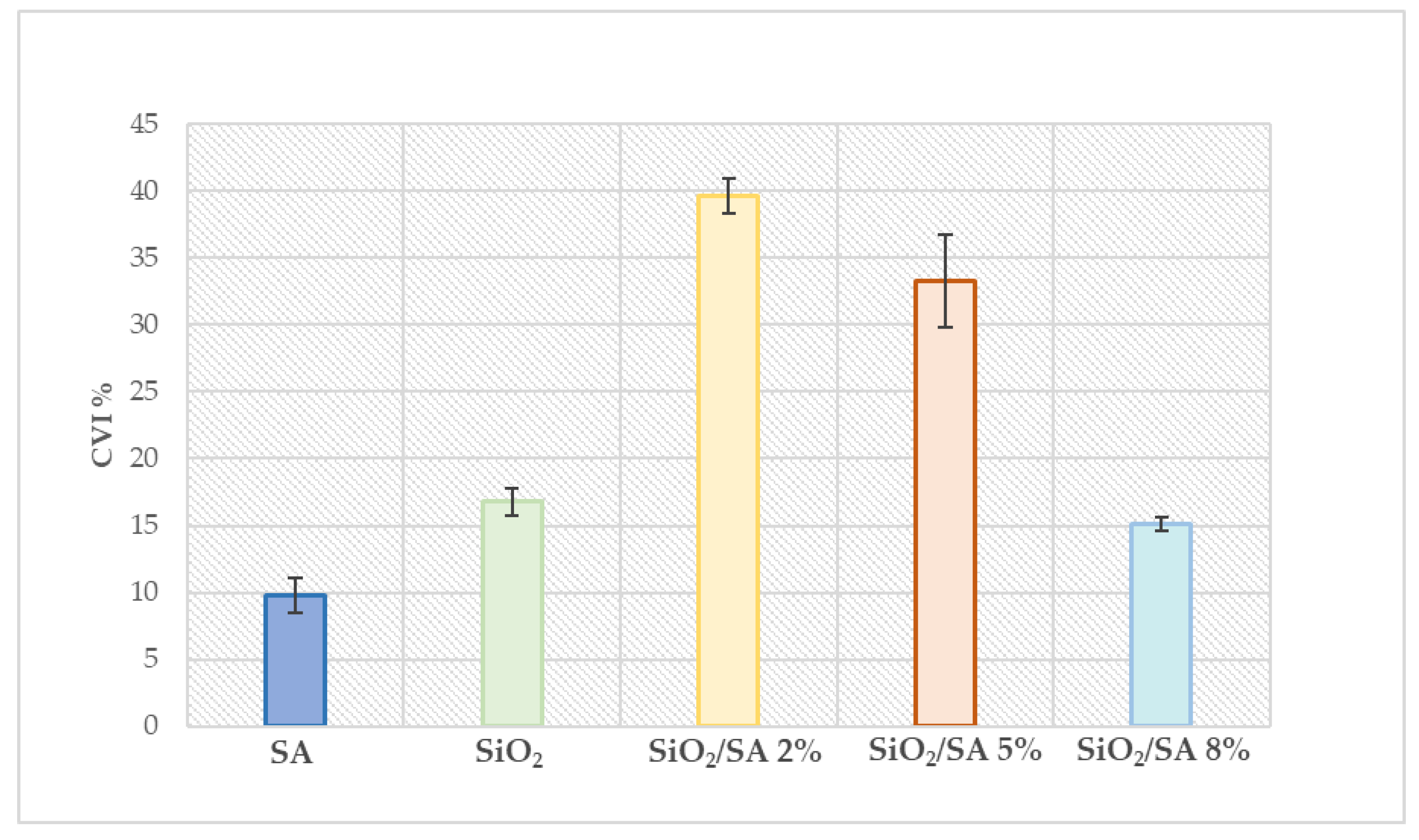

2.6. Cytotoxicity Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sol-Gel Synthesis

3.2. FTIR Analysis

3.3. XRD Analysis

3.4. BET Study

3.5. Moisture Absorption Analysis

3.6. Thermal Analysis

3.7. Cytotoxicity Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langer, R.; Vacanti, J.P. Tissue Engineering. Science 1993, 260, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Han, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liao, B.; Li, X.; Tan, J.; Han, X.; Shen, J.; Bai, D. Smart Responsive Biomaterials for Spatiotemporal Modulation of Functional Tissue Repair. Materials Today Bio 2025, 33, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskaran, P.; Muthiah, B.; Uthirapathy, V. A Systematic Review on Biomaterials and Their Recent Progress in Biomedical Applications: Bone Tissue Engineering. Reviews in Inorganic Chemistry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, S.; Athar Hashmi, F.; Imran, I. Recent Progress in Development and Applications of Biomaterials. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 62, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, P.X. Polymeric Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 2004, 32, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, K.; Kovářík, T.; Křenek, T.; Docheva, D.; Stich, T.; Pola, J. Recent Advances and Future Perspectives of Sol–Gel Derived Porous Bioactive Glasses: A Review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 33782–33835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, N.; Venkatraman, S.K.; Soundhariyaa, T.N.; Mohan, S.; Magesvaran, M.K.; Genasan, K.; Alex, R.A.; Abraham, J.; Swamiappan, S. FUEL-ASSISTED SOL-GEL COMBUSTION SYNTHESIS OF MONTICELLITE: STRUCTURAL, MECHANICAL, AND BIOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION FOR TISSUE ENGINEERING. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 0095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R.K.; Kiick, K.L.; Sullivan, M.O. Encapsulation of Collagen Mimetic Peptide-Tethered Vancomycin Liposomes in Collagen-Based Scaffolds for Infection Control in Wounds. Acta Biomaterialia 2020, 103, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Fiorentino, M.; Viola, V.; Vertuccio, L.; Catauro, M. Effect of Nitric Acid on the Synthesis and Biological Activity of Silica–Quercetin Hybrid Materials via the Sol-Gel Route. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoushtari, M.S.; Hoey, D.; Biak, D.R.A.; Abdullah, N.; Kamarudin, S.; Zainuddin, H.S. Sol–Gel-templated Bioactive Glass Scaffold: A Review. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 40, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niari, S.A.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Geranmayeh, M.H.; Karimipour, M. Biomaterials Patterning Regulates Neural Stem Cells Fate and Behavior: The Interface of Biology and Material Science. J Biomedical Materials Res 2022, 110, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaini, G.; Pirozzi, P.; Catauro, M.; D’Angelo, A. Hybrid Organic–Inorganic Biomaterials as Drug Delivery Systems: A Molecular Dynamics Study of Quercetin Adsorption on Amorphous Silica Surfaces. Coatings 2024, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamula, E.; Kokoszka, J.; Cholewa-Kowalska, K.; Laczka, M.; Kantor, L.; Niedzwiedzki, L.; Reilly, G.C.; Filipowska, J.; Madej, W.; Kolodziejczyk, M.; et al. Degradation, Bioactivity, and Osteogenic Potential of Composites Made of PLGA and Two Different Sol–Gel Bioactive Glasses. Ann Biomed Eng 2011, 39, 2114–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdarta, J.; Jesionowski, T. Silica and Silica-Based Materials for Biotechnology, Polymer Composites, and Environmental Protection. Materials 2022, 15, 7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, M.; Mishra, M.; Joshi, P.A.; Shah, D.O. Study on the Catalytic Properties of Silica Supported Copper Catalysts. Procedia Engineering 2013, 51, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, L.; Turkki, P.; Huynh, N.; Massera, J.M.; Hytönen, V.P. Surface Modification of Bioactive Glass Promotes Cell Attachment and Spreading. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 22635–22642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodium Alginate in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Areas. In Natural Polysaccharides in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 59–100 ISBN 978-0-12-817055-7.

- Ahmad Raus, R.; Wan Nawawi, W.M.F.; Nasaruddin, R.R. Alginate and Alginate Composites for Biomedical Applications. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021, 16, 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.A.; Thomsen, P.; Palmquist, A. Osseointegration and Current Interpretations of the Bone-Implant Interface. Acta Biomaterialia 2019, 84, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, E.; Campardelli, R.; Pettinato, M.; Perego, P. Innovations in Smart Packaging Concepts for Food: An Extensive Review. Foods 2020, 9, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, J.H.; Quevedo, B.V.; Komatsu, D.; Santos, A.R.; De Souza, A.L.; De Rezende Duek, E.A. Development of Silica/Collagen Hybrids Synthesized Via a Simplified Sol-Gel Reaction for Biomaterial Applications. Silicon 2025, 17, 1693–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Shahbazi, M.-A.; Montes, S.; Hosseini, S.H.; Eskandari, M.R.; Zaunschirm, S.; Verwanger, T.; Mathur, S.; Milow, B.; Krammer, B.; et al. Mechanically Strong Silica-Silk Fibroin Bioaerogel: A Hybrid Scaffold with Ordered Honeycomb Micromorphology and Multiscale Porosity for Bone Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 17256–17269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abka-khajouei, R.; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Shen, P.; Peng, Q. Structures, Properties and Application of Alginic Acid: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 162, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, X. Preparation and Characterization of Nanoparticle Reinforced Alginate Fibers with High Porosity for Potential Wound Dressing Application. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 39349–39358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, M.A.A.; Khalifa, H.O.; Ki, M.-R.; Pack, S.P. Nanoengineered Silica-Based Biomaterials for Regenerative Medicine. IJMS 2024, 25, 6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-G.; Park, J.-H.; Oh, C.; Oh, S.-G.; Kim, Y.C. Preparation of Highly Monodispersed Hybrid Silica Spheres Using a One-Step Sol−Gel Reaction in Aqueous Solution. Langmuir 2007, 23, 10875–10878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni Júnior, L.; Da Silva, R.G.; Anjos, C.A.R.; Vieira, R.P.; Alves, R.M.V. Effect of Low Concentrations of SiO2 Nanoparticles on the Physical and Chemical Properties of Sodium Alginate-Based Films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 269, 118286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni Júnior, L.; Fozzatti, C.R.; Jamróz, E.; Vieira, R.P.; Alves, R.M.V. Biopolymer-Based Films from Sodium Alginate and Citrus Pectin Reinforced with SiO2. Materials 2022, 15, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, M.M.; Mabrouk, M.; Soliman, I.E.; Beherei, H.H.; Tohamy, K.M. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Prepared by Different Methods for Biomedical Applications: Comparative Study. IET Nanobiotechnology 2021, 15, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Arotiba, O.A. Synthesis, Swelling and Adsorption Studies of a pH-Responsive Sodium Alginate–Poly(Acrylic Acid) Superabsorbent Hydrogel. Polym. Bull. 2018, 75, 4587–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, S.R.; Hussein, M.H.; El-Naggar, N.E.-A.; Mostafa, S.I.; Shaaban-Dessuuki, S.A. Characterization of Alginate Extracted from Sargassum Latifolium and Its Use in Chlorella Vulgaris Growth Promotion and Riboflavin Drug Delivery. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, A.; Sanagi, M.M.; Abu Naim, A.; Abd Karim, K.J.; Wan Ibrahim, W.A.; Abdulganiyu, U. Alginate Graft Polyacrylonitrile Beads for the Removal of Lead from Aqueous Solutions. Polym. Bull. 2016, 73, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onbas, R.; Yesil-Celiktas, O. Synthesis of Alginate-silica Hybrid Hydrogel for Biocatalytic Conversion by Β-glucosidase in Microreactor. Engineering in Life Sciences 2019, 19, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabish, M.S.; Hanapi, N.S.M.; Ibrahim, W.N.W.; Saim, N.; Yahaya, N. Alginate-Graphene Oxide Biocomposite Sorbent for Rapid and Selective Extraction of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Using Micro-Solid Phase Extraction. Indones. J. Chem. 2019, 19, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkach, S.R.; Voron’ko, N.G.; Sokolan, N.I.; Kolotova, D.S.; Kuchina, Y.A. Interactions between Gelatin and Sodium Alginate: UV and FTIR Studies. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2020, 41, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannier, A.; Soltmann, U.; Soltmann, B.; Altenburger, R.; Schmitt-Jansen, M. Alginate/Silica Hybrid Materials for Immobilization of Green Microalgae Chlorella Vulgaris for Cell-Based Sensor Arrays. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 7896–7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, M.; Piccolella, S.; Gravina, C.; Stinca, A.; Esposito, A.; Catauro, M.; Pacifico, S. Encapsulating Calendula Arvensis (Vaill.) L. Florets: UHPLC-HRMS Insights into Bioactive Compounds Preservation and Oral Bioaccessibility. Molecules 2022, 28, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, G.G.; Mitev, P.D.; Briels, W.J.; Hermansson, K. Red-Shifting and Blue-Shifting OH Groups on Metal Oxide Surfaces – towards a Unified Picture. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 12678–12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tang, X.; Tang, L.; Zhang, B.; Mao, H. Synthesis and Formation Mechanism of Amorphous Silica Particles via Sol–Gel Process with Tetraethylorthosilicate. Ceramics International 2019, 45, 7673–7680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Arcos, T.; Müller, H.; Wang, F.; Damerla, V.R.; Hoppe, C.; Weinberger, C.; Tiemann, M.; Grundmeier, G. Review of Infrared Spectroscopy Techniques for the Determination of Internal Structure in Thin SiO2 Films. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2021, 114, 103256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiercigroch, E.; Szafraniec, E.; Czamara, K.; Pacia, M.Z.; Majzner, K.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M.; Malek, K. Raman and Infrared Spectroscopy of Carbohydrates: A Review. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2017, 185, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacrés, N.A.; Cavalheiro, E.; Schmitt, C.; Venâncio, T.; Alarcón, H.; Valderrama, A. Preparation of Composite Films of Sodium Alginate-Based Extracted from Seaweeds Macrocystis Pyrifera and Lessonia Trabeculata Loaded with Aminoethoxyvinylglycine. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti Borah, S.; Kumar, R.; Prasad Singh, P.; Kumar, V. SnO2 Encapsulated in Alginate Matrix: Evaluation and Optimization of Bioinspired Nanoadsorbents for Azo Dye Removal. ChemBioChem 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundarrajan, P.; Eswaran, P.; Marimuthu, A.; Subhadra, L.B.; Kannaiyan, P. One Pot Synthesis and Characterization of Alginate Stabilized Semiconductor Nanoparticles. Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society 2012, 33, 3218–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortalò, C.; Russo, P.; Miorin, E.; Zin, V.; Paradisi, E.; Leonelli, C. Extruded Composite Films Based on Polylactic Acid and Sodium Alginate. Polymer 2023, 282, 126162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Mortalò, C.; Russo, P.; Zin, V.; Miorin, E.; Montagner, F.; Leonelli, C.; Deambrois, S.M. Facile and Effective Method for the Preparation of Sodium Alginate/TiO2 Bio-Composite Films for Different Applications. Macromolecular Symposia 2024, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwira, A.; Szewczyk, A.; Konopacka, A.; Górska, M.; Majda, D.; Sądej, R.; Prokopowicz, M. Silica-Polymer Composites as the Novel Antibiotic Delivery Systems for Bone Tissue Infection. Pharmaceutics 2019, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebnalwaled, A.A.; Sadek, A.H.; Ismail, S.H.; Mohamed, G.G. Structural, Optical, Dielectric, and Surface Properties of Polyimide Hybrid Nanocomposites Films Embedded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Synthesized from Rice Husk Ash for Optoelectronic Applications. Opt Quant Electron 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liang, J.; Fukuda, S.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S. Sodium Alginate–Silica Composite Aerogels from Rice Husk Ash for Efficient Absorption of Organic Pollutants. Biomass and Bioenergy 2022, 159, 106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, X.; Gu, Z.; Qian, J.; He, C.; Lai, M.; et al. Differential Fiber Optic Humidity Sensor Based on Superhydrophilic SiO2/Polyethylene Glycol Composite Film with Linear Response. Optical Fiber Technology 2025, 90, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ding, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ju, J. Research Progress on Moisture-Sorption Actuators Materials. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Vargas, C.; Ponce, N.M.A.; Stortz, C.A.; Fissore, E.N.; Bonelli, P.; Otálora González, C.M.; Gerschenson, L.N. Pectin Obtention from Agroindustrial Wastes of Malus Domestica Using Green Solvents (Citric Acid and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents). Chemical, Thermal, and Rheological Characterization. Front. Chem. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshaya, S.; Nathanael, A.J. A Review on Hydrophobically Associated Alginates: Approaches and Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4246–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-González, A.C.; Téllez-Jurado, L.; Rodríguez-Lorenzo, L.M. Preparation of Covalently Bonded Silica-Alginate Hybrid Hydrogels by SCHIFF Base and Sol-Gel Reactions. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 267, 118186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Hernández, C.G.; Cornejo-Villegas, M.D.L.A.; Moreno-Martell, A.; Del Real, A. Synthesis of a Biodegradable Polymer of Poly (Sodium Alginate/Ethyl Acrylate). Polymers 2021, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos Araújo, P.; Belini, G.B.; Mambrini, G.P.; Yamaji, F.M.; Waldman, W.R. Thermal Degradation of Calcium and Sodium Alginate: A Greener Synthesis towards Calcium Oxide Micro/Nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 140, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, D.; Wang, D.; Ding, Y.; Wang, G.; Liang, Z.; Shen, Z.; Li, A.; Chen, X.; et al. Sodium Alginate-Derived Porous Carbon: Self-Template Carbonization Mechanism and Application in Capacitive Energy Storage. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 620, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.D.P.; Dos Santos, J.E.; Chierice, G.O.; Cavalheiro, É.T.G. Thermal Behavior of Alginic Acid and Its Sodium Salt. Eclet. Quim. 2004, 29, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Yang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, M.; Wei, W. Low-Temperature Dried Alginate/Silica Hybrid Aerogel Beads with Tunable Surface Functionalities for Removal of Lead Ions from Water. Gels 2025, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, I.P.S.; Jayawardena, T.U.; Sanjeewa, K.K.A.; Wang, L.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Lee, W.W. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Alginic Acid from Sargassum Horneri against Urban Aerosol-Induced Inflammatory Responses in Keratinocytes and Macrophages. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 160, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrogianni, A.; Sotiriou, G.A.; Brambilla, D.; Leroux, J.-C.; Pratsinis, S.E. The Effect of Settling on Cytotoxicity Evaluation of SiO2 Nanoparticles. Journal of Aerosol Science 2017, 108, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, M.; D’Angelo, A.; Vertuccio, L.; Khan, H.; Catauro, M. Characterization of Grape Extract-Colored SiO2 Synthesized via the Sol–Gel Method. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 11697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolella, S.; Fiorentino, M.; Cimmino, G.; Esposito, A.; Pacifico, S. Cilentan Cichorium Intybus L. Organs: UHPLC-QqTOF-MS/MS Analysis for New Antioxidant Scenario, Exploitable Locally and Beyond. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi-Chendouh, N.; Piccolella, S.; Gravina, C.; Fiorentino, M.; Formato, M.; Kheyar, N.; Pacifico, S. Ready-to-Use Nutraceutical Formulations from Edible and Waste Organs of Algerian Artichokes. Foods 2022, 11, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | BET Surface Area (m2/g) |

|---|---|

| SA | 0.2307 ± 0.0067 |

| SiO2 | 9.6861 ± 0.3576 |

| SiO2 / SA 2% | 325.2401 ± 5.3292 |

| SiO2 / SA 5% | 138.6862 ± 2.1163 |

| SiO2 / SA 8% | .0956 |

| Mass loss (%) / DTG (%/°C) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trange/°C | Phenomena | SA | SiO2/SA2% | SiO2/SA5% | SiO2/SA8% |

| 200 – 250 | 1. Decarboxylation (Exo) | 40.34%, 234.78 %/°C |

1.82% 223.01%/°C |

3.57% 224.91 %/°C |

3.61% 237.36 %/°C |

| 350 – 500 | 2. Na2CO3 formation (Exo) | 13.40% 417.37%/°C |

4.21% | 6.86% | 6.93% |

| 550 – 860 | 3. Na2CO3 decomposition (Endo) | 30.81% 786.78%/°C |

- | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).