1. Introduction

Extensive research is done to develop antimicrobial materials using hydrogels. Hydrogels from natural polysaccharides have unique characteristics compared to other biopolymers because of their ease of availability, non-toxicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. Natural hydrogels are those from natural sources with good bio-mimic properties like biodegradability and biocompatibility but are generally mechanically weak [

1,

2]

.

Hydrogels are three-dimensional hydrophilic polymeric networks with amine, hydroxyl, carboxyl or sulphonic groups in their backbone, capable of absorbing vast quantities of water [

3] Among the natural polysaccharides alginate and cellulose-based polymers are widely used because they are well known for their non-toxicity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, availability and cheap cost [

4,

5].

Alginate is an anionic polysaccharide distributed widely in the cell walls of brown algae, where through binding with water it forms a viscous gum. It is also known as alginic acid or align. Alginic acid is a linear copolymer with homopolymeric blocks of (1−4)-linked β-D-mannuronate (M) and its C−5 epimer α-L-guluronate (G) residues, respectively, covalently linked together in different sequences or blocks. The distribution and sequence of the mannuronic and guluronic acid residues along the polymer chain are critical determinants of its physicochemical properties, including its ability to gel, viscosity, and biocompatibility. These characteristics make sodium alginate an attractive material for various applications in food, pharmaceutical, and biomedical industries [

1].

Cellulose is one of the most abundant naturally occurring polysaccharides which is a glucose derivative in which the glucose units are linked by beta glycosidic linkage. Since cellulose is insoluble in water and many other organic solvents, it is desirable to work with cellulose derivatives like hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), ethyl cellulose (EC), hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) and methylcellulose (MC). One of the commonly used cellulose derivatives is hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC).

HEC is a major derivative of cellulose, where the ethyl group replaces one or more of the three hydroxyl groups present in each glucopyranoside. The properties and behaviour of these polymers are highly influenced by the degree of substitution and their relative distribution within C1, C2 and C6 positions. Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) is a hydrophilic polysaccharide biopolymer with β(1→4) glycosidic linkage [

6].

For practical applications, sodium alginate is usually blended with other polymers to improve the mechanical, thermal and other physical properties and is used in various fields like agriculture, water treatment, tissue engineering applications, and pharmaceuticals. Alginate blended with other polymers could be cross-linked physically or chemically [

7] to make them water-insoluble and improve their mechanical properties. Physical cross-linking is achieved by dipole-dipole interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic or electrostatic forces which is temporary and these hydrogels are reversible, while chemical cross-linking is permanent and involves covalent bonding through the functional groups in the cross-linkers used, making the hydrogels irreversible and more stable [

8,

9]. The commonly used chemical cross-linkers include carbodiimide, citric acid, fumaric acid, 1, 2, 3, 4-butane tetracarboxylic dianhydride, glutaraldehyde, and ethylene diamine tetraacetic dianhydride. Compared to chemical cross-linking, physical cross-linking is preferred in forming biocompatible materials for biomedical applications since no toxic chemicals are used here [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

The carboxyl ( –COOH) or hydroxyl ( –OH) groups of alginate and hydroxyl ( –OH) groups of hydroxyethyl cellulose are helpful in cross-linking and producing excellent materials. The green chemistry approach prefers the bivalent ions crosslinking of sodium alginate since it does not involve any toxic initiators, monomers or cross-linkers [

18,

19]. There are many reports about the alginate cross-linking with bivalent metal ions, including Ca

2+, Ba

2, Fe

2+ Sr

2+, Co

2+, Ni

2+, Zn

2+, and Mn

2+and so on. It is reported that among the bivalent cations, Mg

2+ cannot cross-link alginate to form stable gels, under normal conditions [

20].

Among the bivalent cations as cross-linkers, Ca

2+ and Mg

2+ were chosen for this study aiming to develop biomaterials for bone tissue engineering. It is well known that Ca

2+ cation is extremely important to the human body helping in many functions. Most of it is found in bones and very little in the extracellular fluids. Magnesium (Mg

2+), is the fourth most abundant cation in the human body and a

cofactor in more than 600 enzymatic reactions [

21]

. Sufficient amount of magnesium has a significant effect on the precipitation of calcium carbonate [

22].

We explored the formation of SA/HEC stable gels by cross-linking them with Ca2+, Mg2+, and a combination of Ca2+ and Mg2+. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on alginate and hydroxyethyl cellulose (SA/HEC) blends cross-linked by bivalent cations (mainly Ca2+, Mg2+ and a combination of Ca2+ and Mg2+), in an environmentally friendly way. It is well known that HEC is a reducing as well as a stabilizing agent. Silver nanoparticles were formed in-situ in the SA/HEC hydrogels. The SA/HEC/AgNP hydrogels have excellent antimicrobial property with good mechanical stability. The SA/HEC/AgNP hydrogels with its significant inhibition of the microbial growth could be a promising candidate in wound healing applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All materials of this work are commercially available. Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) was purchased from SIGMA-ALDRICH, Germany. Sodium alginate (SA) was purchased from S.D Fine-Chem (SDFCL) Limited, India. Calcium chloride (CaCl2.H2O) and magnesium chloride (MgCl2.6H2O) were purchased from Philips Harris, England. All the chemicals used in this study were of high purity and without further purification. All the solutions were prepared using millipore water.

2.2. Preparation of SA/HEC hydrogels

Sodium alginate (SA) 2.5 wt% and Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) 3.75 w% were used for this study. These concentrations were chosen to get the solutions of desired viscosity. After weighing the polymers they were dissolved in water and stirred for 12 h at room temperature to get homogeneous solutions. HEC/SA blend solution was prepared by mixing HEC and SA in 1:1 ratio followed by stirring for 12 h at room temperature to get a homogeneous blend solution.

2.3. Cross-linking of SA/HEC hydrogels

Cross-linking was carried out using 0.1 M of CaCl2 and MgCl2 cross-linkers for 10 min. The formation of beads took place in a petri dish (10 cm diameter) which contained 25 mL of 0.1 M of the cross-linkers. Beads were formed using a pipette, by drop casting the HEC/SA blend polymers into a beaker containing the bivalent cation cross-linkers at room temperature. Thin films were produced by taking 10 mL of the HEC/SA blend polymers into a petri dish and pouring 20 mL of the bivalent cation cross-linkers over it. Sponges were produced by freeze drying 25 mL of the HEC/SA solution in a beaker. After that 25 mL of the bivalent cation cross linkers were poured over the freze dried polymers. After 10 min the cross-linked hydrogels were rinsed copiously with ultrapure water. Then the samples were dried at 50 °C overnight for 24 h. These dried samples were used for all the physicochemical characterization. The samples were called SA/HEC-Ca2+, SA/HEC-Ca2+/Mg2+, or, SA/HEC- Mg2+ hydrogels.

2.4. Preparation of SA/HEC/silver nanoparticles (AgNP) and cross-linking of the hydrogel

SA/HEC hydrogels (

Section 2.2) was used to prepare the silver nanoparticles. To a 5 mL of the SA/HEC hydrogel 300 µL of 50 mM AgNO

3 was added and heated at 80 °C for 1 h. The color change from colorless to pale yellow and finally to brown indicated the formation of silver nanoparticles. To cross-link the SA/HEC/AgNP hydrogel with calcium 10 mL of 0.1 M CaCl

2 was taken in a petri dish and the hydrogel was dropped into the CaCl

2 using a syringe. To cross-link the hydrogel with Ca/Mg 5 mL of 0.1 M CaCl

2 and 5 mL of 0.1 M MgCl

2 were taken in a petri dish and the hydrogel was dropped into the CaCl

2/MgCl

2 using a syringe. The hydrogel was cross-linked immediately but it was removed after 10 min and washed with water copiously and dried at 40 °C overnight.

2.5. Characterization of SA/HEC hydrogels

2.5.1. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

To evaluate the structural changes of the hydrogel, the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of the mixture of sodium alginate (SA) hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC), (HEC/SA) and SA/HEC-Ca2+, SA/HEC-Mg2+, SA/HEC-Ca2+/Mg2+ were recorded by FTIR IRPrestige−21 (Shimadzu) spectrometer. The analysis was carried out in a range of 400 to 4000 cm−1 with 128 scans recorded at 4 cm−1 of resolution.

2.5.2. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

Thermo Gravimetric Analyzer (TGA) TG 209F3, NETZSCH, Germany) instrument was used to verify the thermal degeneration attributes of SA/HEC hydrogels. The starting weight of the analysis was 6 mg sample and the analysis was carried out under N2 and the heating rate was 10 °C/min until 700 °C.

2.5.3. Different Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The thermal behavior of the prepared samples was studied by placing them in an aluminum crucible. The heat evolved was recorded at a 10.0 (K/min) heating rate, starting at 50 °C until 250 °C in N2 dynamic atmosphere at a flow rate of 40.0 mL/min until 60.0 mL/min.

2.5.4. Morphological characterizations

Scanning electron microscopy was used on SA/HEC-Ca2+, SA/HEC-Ca2+/Mg2+, and SA/HEC- Mg2+ hydrogels to get the surface morphology and the porous structure at various magnifications. To get the cross-section images the beads, thin films, and freeze-dried hydrogels were carefully cut by using a sharp razor blade, mounted onto the sample holders, coated with gold, and then observed and imaged. The morphologies of the cross-linked SA/HEC hydrogels at room temperature were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM JSM-7800F) with 20 kV accelerating voltage.

2.5.5. X-ray diffractometer (XRD)

The XRD analysis of SA/HEC hydrogels with and without cross-linking was performed using a Philips X’pert PRO automatic diffractometer operating at 40 kV and 40 mA with a scan rate of 2°/min. The XRD spectra were recorded in the 2θ range of 10–70°.

2.5.6. Mechanical testing

The mechanical properties of the cross-linked SA/HEC hydrogel films were studied using a texture analyzer (TA. XT plus, Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, England) using a 5 kg load cell. Tests were done in triplicates. For this study rectangular strips with dimensions 7 mm × 70 mm were placed between two clamps at 60 mm distance. The mechanical properties like tensile strength and elongation at break were obtained directly from the software exponent connect.

2.5.7. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

UV-vis absorption spectra of the silver nanoparticles in the hydrogel were measured by using Spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan) with range of wavelength (300–700) nm. All spectra were recorded in the absorbance mode and the optical spectra were acquired, by using a quartz cuvettes (1 cm) path length.

2.5.8. Stability of SA/HEC hydrogels

The SA/HEC hydrogels beads were immersed in water and monitored for more than six months.

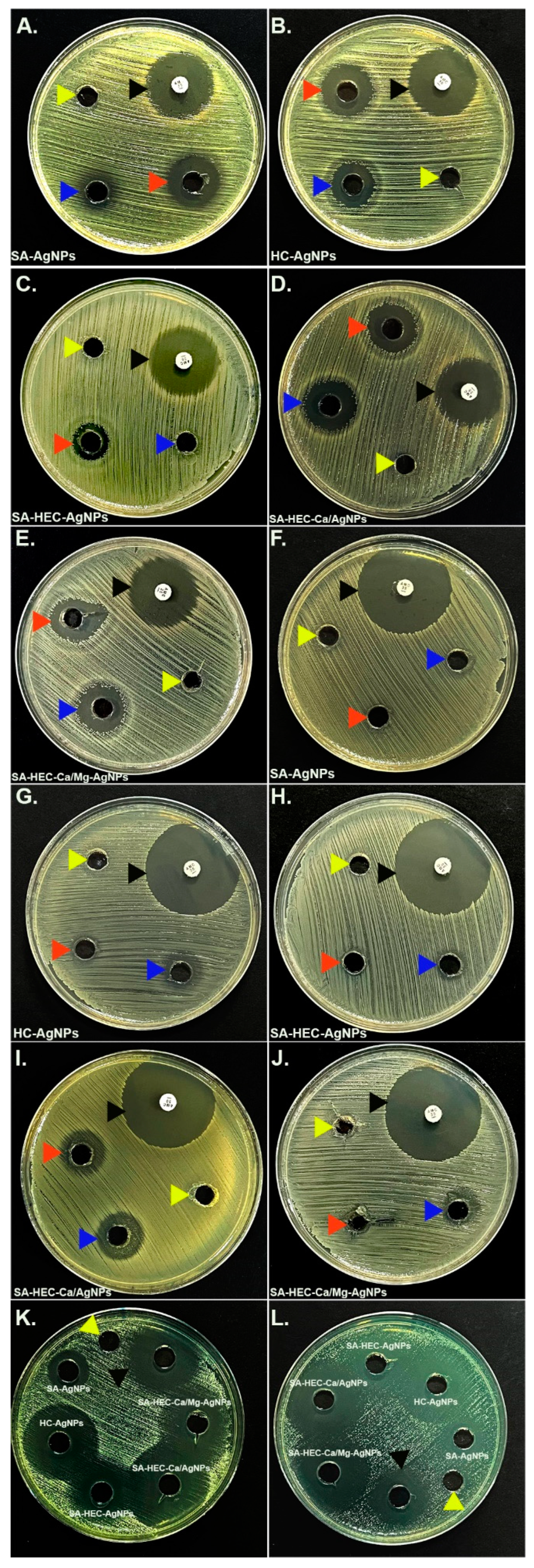

2.5.9. Antimicrobial activities of alginate and cellulosic derived compounds

The invitro antimicrobial activities for all the compounds [Sodium Alginate- Silver nanoparticles (SA-AgNPs); Hydroxyethyl cellulose-silver nanoparticles (HC-AgNPs); Sodium Alginate- Hydroxyethyl cellulose -silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-AgNPs); Sodium Alginate-Hydroxyethyl cellulose—Calcium/silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-Ca/AgNPs); Sodium Alginate- Hydroxyethyl cellulose-Calcium/Magnesium -silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-Ca/Mg-AgNPs)] were performed against the two bacterial strains,

viz Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213,

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and two fungal strains,

viz Candida albicans ATCC 14053),

Candida kruzei ATCC 6258. All the cultures were resourced from the microbiology laboratory, Natural and Medical Sciences Research Center, University of Nizwa, Oman. Well-diffusion technique [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] on 3.8% Muller–Hinton agar (MHA) (Liofilchem, Teramo, Italy) media plates was adopted. Two -three morphologically identical colonies from each of the bacterial and fungal subculture plates were suspended in 5 mL physiological saline (0.9%) followed by the adjustment of their concentration to 0.5% McFarland standard. Following this, 200 µL of each of these solutions were spread on MHA media plate with a sterilized cotton swab. Further, the media plates were bored (bore size = 5 mm) with wells with a sterile metallic plug borer and filled with 20 µL of each of the diluted (2-fold) and undiluted compounds (50%). Ciprofloxacin/Amoxycillin and amphotericin B(S) served as positive control for bacteria and fungus, respectively, while sterile distilled water was used as negative control in both the cases. Bacterial and fungal plates were incubated at 37 °C and 25 °C, respectively in the upright position until zones of inhibition were observed, which was considered an endpoint parameter for the antimicrobial activities. The diameter of the inhibition zones was measured in millimeter using the glass scale.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural aspects of the SA/HEC hydrogels

The bivalent cations Ca

2+, Mg

2+ and Ca

2+/Mg

2+ were chosen for this study. The SA/HEC hydrogels were cross-linked by Ca

2+ and also by a mixture of Ca

2+/Mg

2+ ions The results showed that the Mg

2+ ions failed to cross-link the SA/HEC hydrogels. SA/HEC hydrogels could be cross-linked by the bivalent metals in various forms like gels, beads, sponges and films. For this study the SA/HEC hydrogels cross-linked by Ca

2+ ions were used.

Figure 1. shows the scanning electron microscope images of the SA/HEC hydrogel cross-linked by Ca

2+ ions in various forms like beads, films, and sponges. The morphology of the surface of the beads shows that it is porous with pore size ranging from approximately 2–20 µm. SA/HEC hydrogel formed free-standing films. The thickness of the film is approximately 150 µm. The calcium crystals are seen to be uniformly spread over the surface of the film.

The sponges show beautifully organized pores. The pore size is approximately 200–700 µm, showing that the pores were mesoporous, which is a very important parameter for an excellent scaffold in bone tissue engineering. The calcium crystals are seen inside and along the walls of the pores. Freeze-dried samples have a highly porous structure with an expanded state of the polymeric chains, which is reported by several researchers [

29,

30]. All these images show that S/HEC hydrogels cross-linked by Ca

2+ ions could be used to form excellent scaffold materials for tissue engineering applications in various forms.

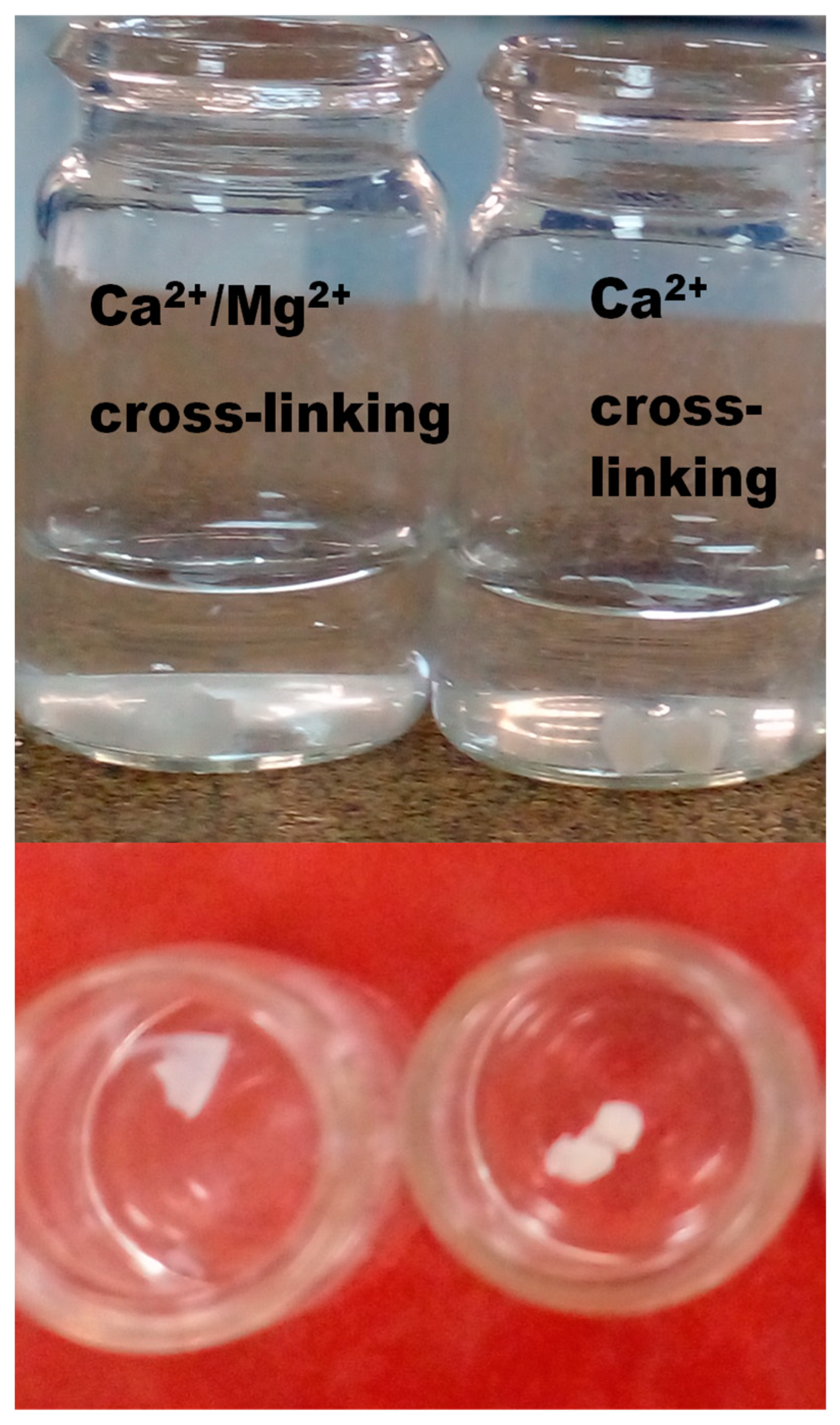

3.2. Physical attributes of the SA/HEC hydrogel

The transparency of the SA/HEC hydrogel films was affected by cross-linking by various metal ions. The films became less transparent with the increase in the cross-linking efficiency. SA/HEC/Ca

2+ showed less transparency compared to to SA/HEC/Ca

2+/Mg

2+, which in turn was less transparent compared to SA/HEC/Mg

2+. The photographs of the films of SA/HEC/X

2+ are shown in

Figure 2. The stiffness of the films decreased in the order of SA/HEC/Ca

2+ > SA/HEC/Ca

2+/Mg

2+ > SA/HEC/Mg

2+, while the flexibility of the films followed the reverse order. It can be seen from

Figure 2, that the SA/HEC/Mg

2+ dried films could not be peeled to get a complete free-standing film.

3.3. Evaluation of FTIR Spectroscopy analysis data.

The FTIR spectra of the SA/HEC, SA/HEC/Ca and SA/HEC/Ca/Mg, are shown in

Figure 3. Peaks seen around 3300 to 3700 cm

−1 are the characteristic peaks of the stretching vibrations of the -OH groups of the polysaccharides of sodium alginate and hydroxyethyl cellulose [

31,

32]. The C=O asymmetric stretching and the -COO-symmetric stretching vibrations of sodium alginate are seen at 1613 cm

−1 and 1415 cm

−1 respectively. The peaks seen at 2900 cm

−1, 1612 cm

−1, and 1055 cm

−1 corresponds to -C-H- stretching vibration, C=O stretching vibration and C-O-C stretching vibration respectively. The strong peaks at 1012 cm

−1 and 952 cm

−1 are attributed to the stretching of C-O and C-C groups respectively [

33,

34,

35].

The peaks after cross-linking are seen at 1061 cm−1 and 611 cm−1. The peaks of the stretching vibrations of the -OH groups of the polysaccharides are reduced after cross-linking. These hydrogels are formed by two types of interactions, hydrogen bonding (between SA and HEC) and ionic interactions (between SA and Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions).

3.4. Mechanical properties of the hydrogels.

A universal testing machine was used to study the mechanical properties of the cross-linked SA/HEC hydrogels. Among the various factors that affect the mechanical properties of the hydrogel films the cross-linking agent and the polymer composition play very important roles. The tensile strength of the SA/HEC hydrogels cross-linked with different bivalent cations is shown in

Table 1. The Young’s modulus for the SA/HEC/Ca

2+ film was better than SA/HEC/Ca

2+/Mg

2+. With Ca

2+ ions the films were harder compared to the films with Ca

2+/Mg

2+.

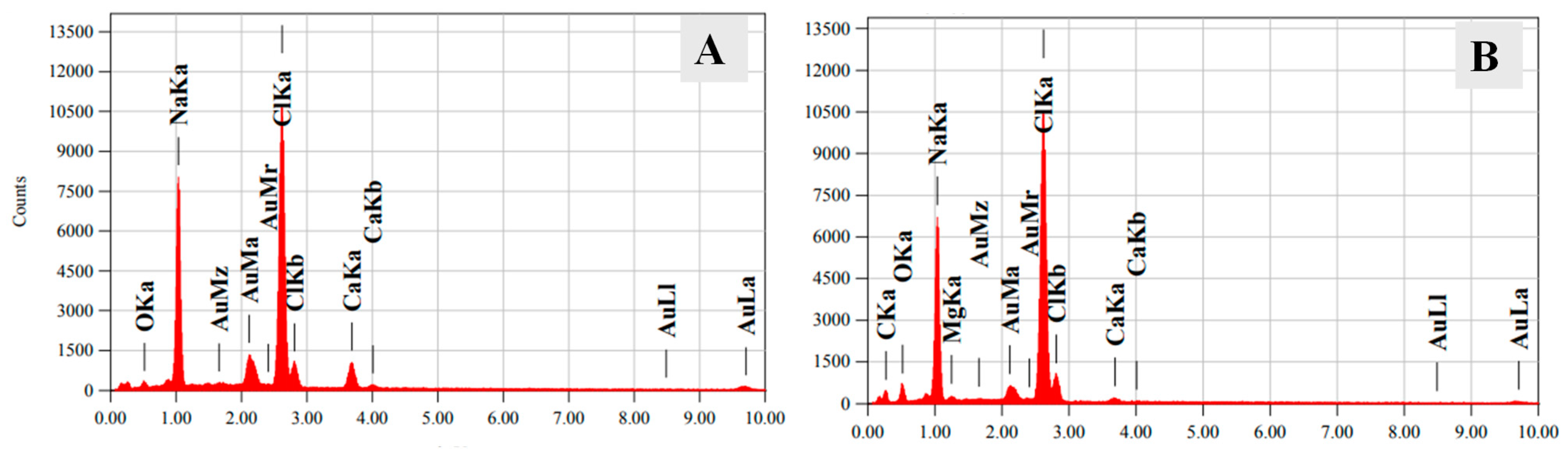

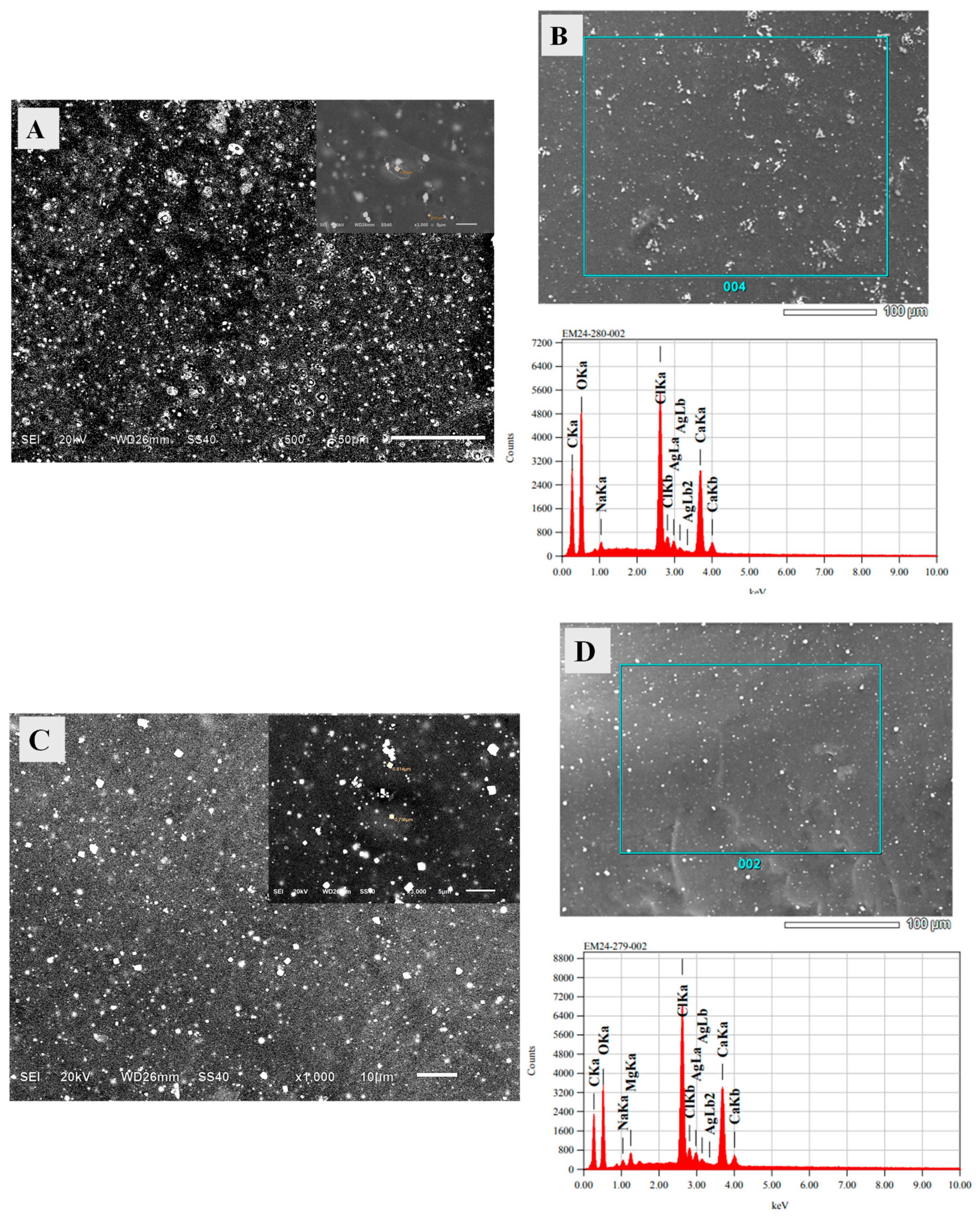

3.5. Evaluation of scanning electron microscopy and EDX analysis data.

The morphology of the cross-linked SA/HEC hydrogels is a very important parameter to be studied. Morphology is generally affected by the synthesis method, cross-linking density, and interfacial tension [

36]. The surface morphology of the scaffolds prepared was examined by using SEM operating at 20 kV accelerating voltage. Since the scaffolds are non-conducting they were coated with gold. The micrographs of SA/HEC hydrogels crosslinked with calcium, and a mixture of calcium and magnesium are shown in

Figure 4. The crystals with various morphologies were seen. As seen in the figure, plenty of crystals are there for the SA/HEC hydrogels cross-linked by the Ca

2+and a mixture of Ca

2+ and Mg

2 Figure 4A shows SA/HEC cross-linked with calcium ions. The length and breadth of the crystals were approximately 5–7 µm and 0.3–0.6 µm respectively. The crystal morphology for SA/HEC co -crosslinked with calcium and magnesium ions is shown in

Figure 4B, which is almost like the calcium crystals with the size ranging from 3–6 µm.

The EDX spectra of the SA/HEC films confirm the presence of Ca, and Mg elements in the hydrogels, as shown in

Figure 5.

3.6. Water stability of the SA/HEC beads crosslinked by Ca2+, and co-crosslinked by Ca2+/Mg2+

The water stability results of the SA/HEC beads crosslinked by Ca

2+ and co-crosslinked by Ca

2+/Mg

2+ are shown in the photographs,

Figure 6. All the beads showed excellent stability except for the one cross-linked by magnesium ions. It is well known that the ion affinity for various bivalent cations towards alginate varies, in which the highest affinity is shown for Pb

2+. Haug et. al., and Smidsrod et al., reported the following ion affinity, Pb

2+ > Cu

2+ > Cd

2+ > Ba

2+ > Sr

2+ > Ca

2+ > Co

2+, Ni

2+, Zn

2+ > Mn

2+ [

37,

38]. A previous study [

39], reported the affinity of some more cations as, GG-blocks: Ba

2+ > Sr

2+ > Ca

2+ > Mg

2+ MM-blocks: Ba

2+ > Sr

2+ ~ Ca

2+ MG-blocks: Ca

2+ > Sr

2+ ~ Ba

2+.

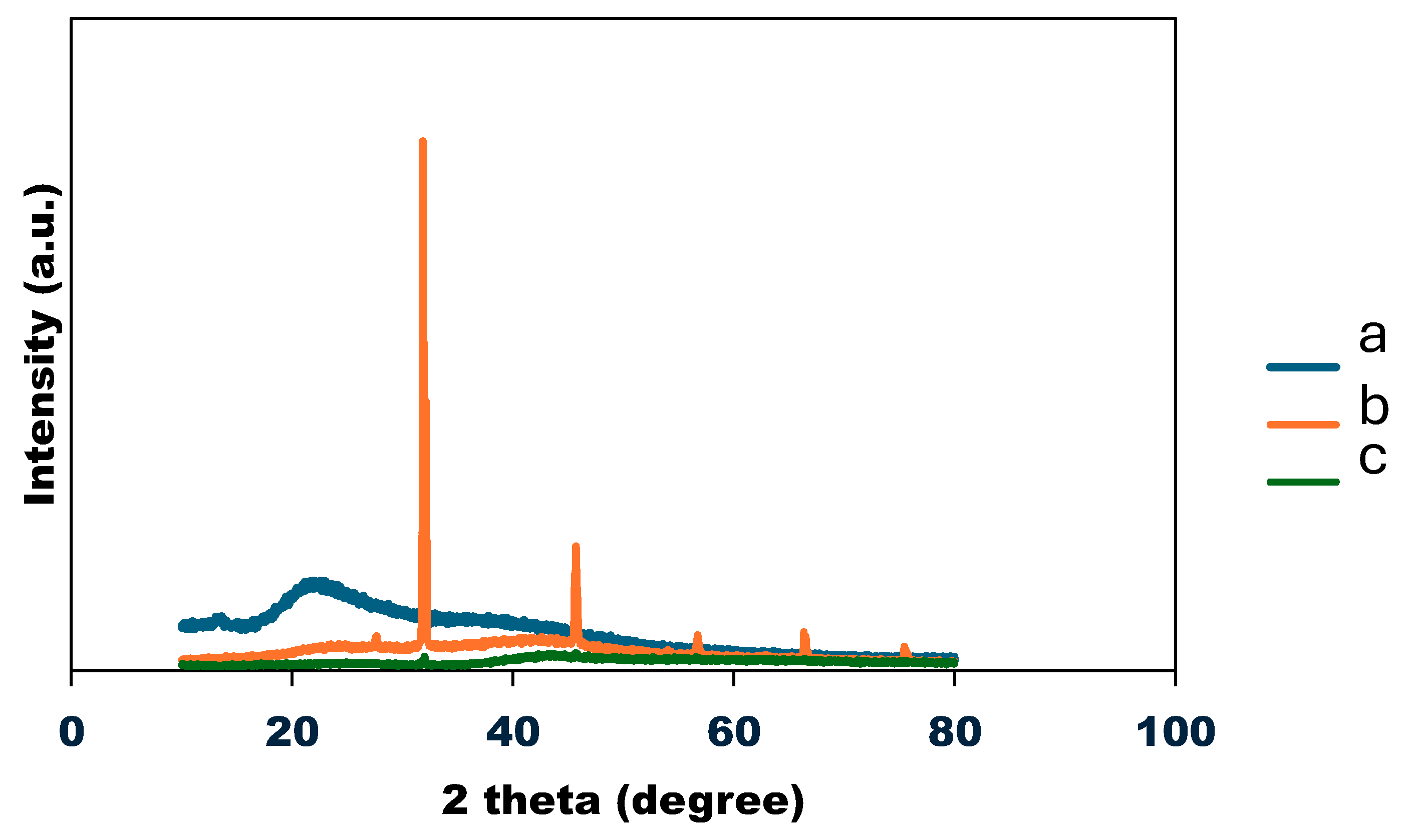

3.7. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis

Figure 7, shows the XRD diffractogram of the SA/HEC before and after cross-linking. The semi-crystalline nature of SA/HEC is shown at peaks 2θ = 21.16 and 42.70°, (Fig. a). The XRD diffractogram of the SA/HEC cross-linked with calcium and a mixture of calcium and magnesium, (Fig. b and c), respectively. For the SA/HEC cross-linked with Ca

2+ ions and co-cross linked with Ca

2+/Mg

2+ ions, multiple peaks ranging from 20–80°. These peaks confirm the in-situ growth of CaCO

3 and MgCO

3 in the SA/HEC hydrogels by mineralization process [

40].

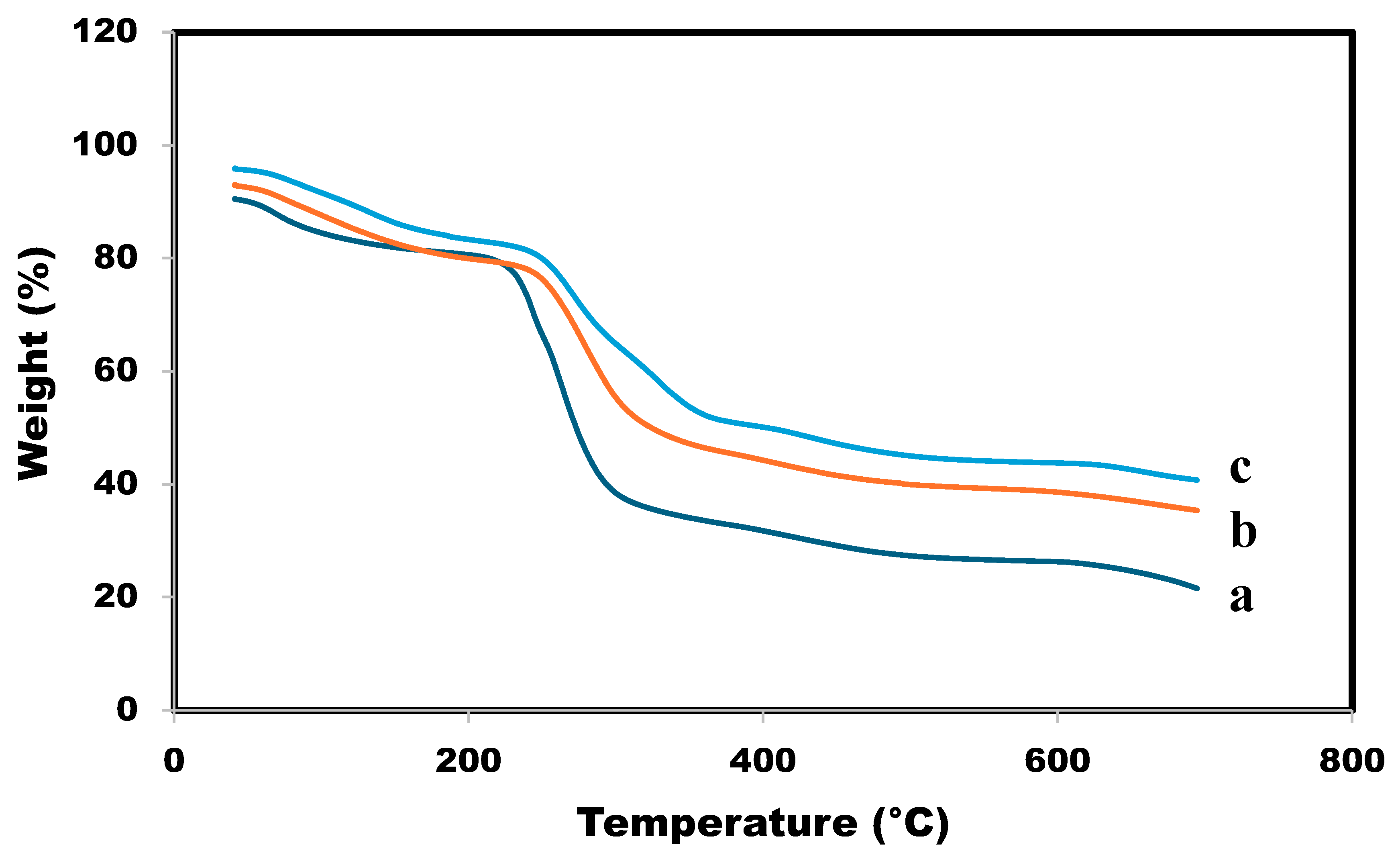

3.8. Thermogravimetric analysis-TGA

The TGA analysis gives information about the thermal stability from which we can understand the temperature changes of the different thermal events [

41,

42]. TGA analysis was used to find the effect of calcium and magnesium ions on the thermal properties of the SA/HEC beads. The TGA curves of the SA/HEC beads before and after cross-linking is shown in

Figure 8. The decline in the TGA plots below 100 °C is generally attributed to the elimination of water molecules that are attached to SA and HEC. Peaks at degradation around 230 °C–250 °C are due to the destruction of glycosidic bonds and degradation of SA and HEC, [

43]. After cross-linking with the Ca

2+ and Ca

2+/Mg

2+ ions the moisture adsorption capacity will be reduced thereby increasing the degradation temperature. The cross-linking slightly improved the thermal stability of the SA/HEC hydrogels at the degradation phase. After cross-linking all the temperatures were higher showing that the thermal stability is increased after cross-linking. The degradation temperatures are shown in

Table 2.

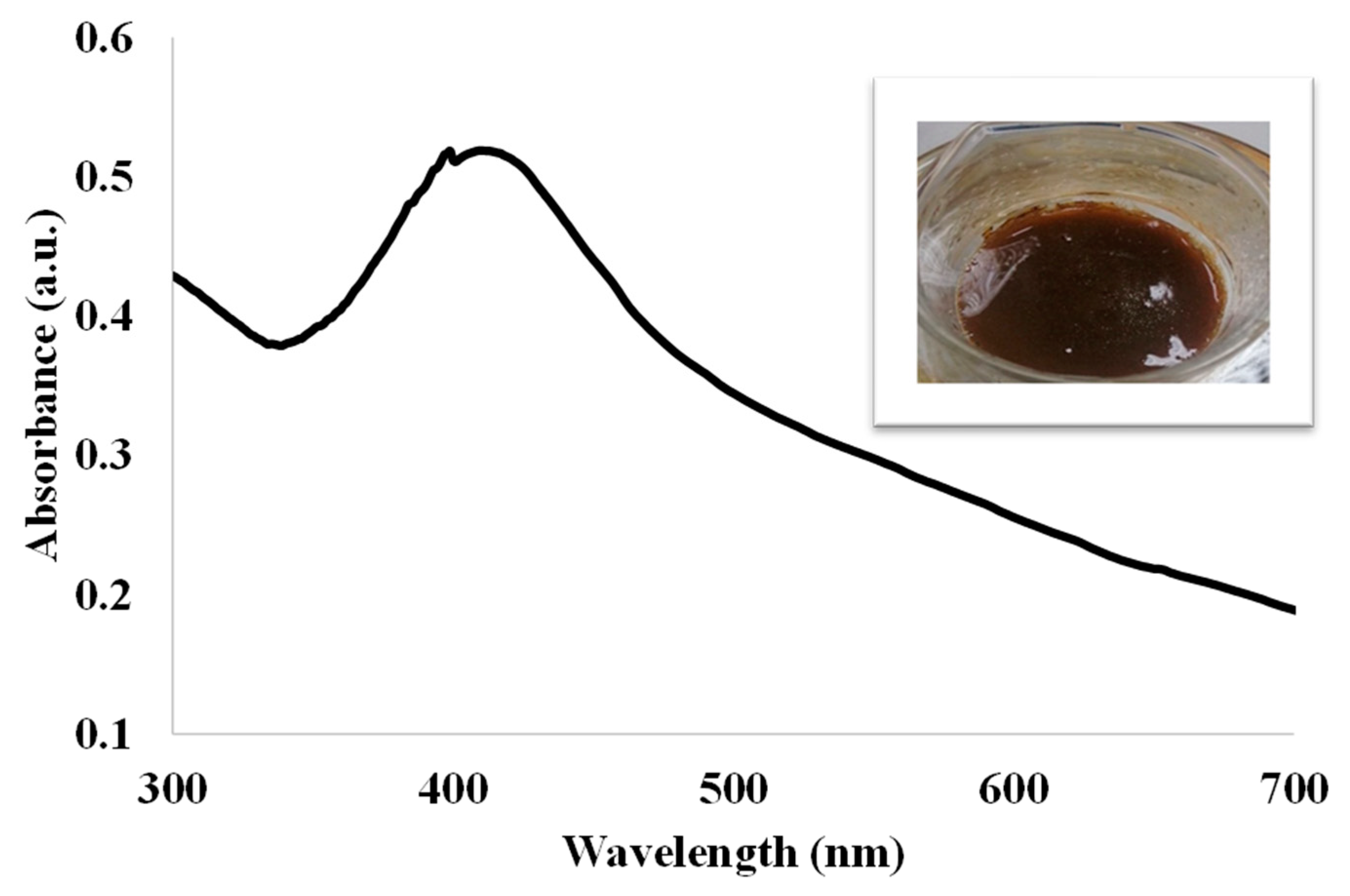

3.9. UV-vis spectroscopy

In this reaction HEC as well as SA acts as the reducing as well as stabilizing agent. The plenty of OH groups in HEC and SA are used to reduce the Ag ions to metallic silver particles. In this reaction the color of the solution changed from colorless to pale yellow in less than 5 min and then to dark yellow, and finally to brown color after 30 min. It is well known that SA and HEC act a reducing as well as stabilizing agents for the formation of silver nanoparticles [

44,

45].

Figure 9 shows the UV-vis spectrum of the SA/HEC/AgNP, the inset shows the photograph of the SA/HEC/AgNP hydrogel. The absorption peak was observed at 416 nm indicating the formation of silver nanoparticle.

3.10. Evaluation of scanning electron microscopy and EDX analysis data for the SA/HEC/AgNP hydrogel cross-linked by Ca2+ and a mixture of Ca2+ and Mg2+

The morphology of the SA/HEC/AgNP/Ca hydrogel beads were examined by using the SEM operating at 20 kV accelerating voltage. The beads were coated with a thin layer of gold using sputtering technique. The micrographs are shown in

Figure 10A. The presence of spherical particles as well as cubic particles were seen. The spherical particles with diameter in the range of 50–200 nm indicates the silver nanoparticles and the cubic particles in the size ranging from 1–5 µm indicates the calcium crystals. The EDX shown in

Figure 10B confirms the presence of Ag and Ca. Similar results were observed for SA/HEC/AgNP/Ca/Mg in which the size of the crystals from Ca and Mg were in the range of 1–5 µm,

Figure 10C and the EDX confirms the presence of Ca, Mg and Ag,

Figure 10D.

3.11. Antimicrobial activities of alginate and cellulosic derived compounds

The

E.

coli ATCC 14053 showed susceptibility against all the diluted (except for SA-HEC-AgNPs) and undiluted compounds with the zones of inhibition ranging from 15–24 mm. All the compounds (except for SA-AgNPs and the undiluted sample of SA-HEC-AgNPs) exhibited antibacterial activities against

S.

aureus ATCC 2913 with the maximum and minimum zone of inhibition observed as 19 and 11 mm, respectively. Notably, strong antifungal activities (maximum zone of inhibition: 45 mm; minimum zone of inhibition: 25 mm) of all the tested compounds were observed against both the fungal strains of

Candida. Concomitantly, all the positive controls [Ciprofloxacin and amphotericin B(S)] exhibited zones of inhibitions, while none of the negative control (sterile water) showed effects (

Figure 11;

Table 3).

4. Conclusions

This study successfully developed highly stable sodium alginate and hydroxyethyl cellulose (SA/HEC) hydrogels in various forms—beads, sponges, and films—using a green chemistry approach with water as the sole solvent. Cross-linking was achieved using bivalent cations, specifically Ca2⁺, Mg2⁺, and Ca2⁺/Mg2⁺. Notably, effective cross-linking only occurred with the combination of Ca2⁺/Mg2⁺, as Mg2⁺ alone failed to cross-link the hydrogel. Characterization using FTIR, SEM, EDX, and XRD confirmed successful crystallization and cross-linking, with enhanced thermal and mechanical properties. SA/HEC sponges displayed high porosity (200–700 µm), and beads exhibited rough surface pores (2–20 µm). In a single, efficient step, biocompatible and biodegradable scaffolds containing both calcium and magnesium were created. The synthesized SA/HEC composites, along with various silver nanoparticle formulations, demonstrated effective antimicrobial properties against E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 29213, C. albicans ATCC 14053, and C. krusei ATCC 6258. This straightforward, eco-friendly approach produces highly stable, antimicrobial, co-crosslinked SA/HEC hydrogels with excellent porosity, positioning them as promising scaffold materials for tissue engineering applications.

Author Contributions

F.S.J.H.: Conceived the concept of this article, Supervision, Data Curation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation, Visualization, Supervision; S.G.: Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation, Visualization; H.S.A.S.: Data Curation, Visualization, Methodology; M.A.-S.: Data Curation, Visualization; I.S.A.A.: Data Curation, Visualization; A.A.H.: Visualization, Conceptualization; A.M.A.A.: Visualization, Conceptualization; A.A.-H.: Data Curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology; S.K.A.-H.: Data Curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology; A.A.-H.: Data Curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the TRC research grant, (BFP/GRG/HSS/23/173). The authors acknowledge the support from the Department of Biological Sciences and Chemistry in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at the University of Nizwa.

Data Availability Statement

Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Department of Biological Sciences and Chemistry, Faculty of Arts and Sciences & Natural and Medical Sciences Research Center, University of Nizwa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. All the authors agreed unconditionally for the publication of this work.

References

- Schmidt, B.V. Hydrophilic polymers. 2019, 11, 693.

- Sharma, B.; Thakur, S.; Mamba, G.; Gupta, R.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Thakur, V.K. Titania modified gum tragacanth based hydrogel nanocomposite for water remediation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Dev, A.; Das, S.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kumar, A.; Thakur, V.K.; Han, S.S. Curcumin-loaded alginate hydrogels for cancer therapy and wound healing applications: A review. International journal of biological macromolecules 2023, 232, 123283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, B.; Koytepe, S.; Ulu, A.; Gurses, C.; Thakur, V.K. Chemistry, structures, and advanced applications of nanocomposites from biorenewable resources. Chemical Reviews 2020, 120, 9304–9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, S.H.; Mohd, N.H.; Suhaili, N.; Anuar, F.H.; Lazim, A.M.; Othaman, R. Preparation of cellulose-based hydrogel: A review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 10, 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, A.; Demitri, C.; Madaghiele, M. Biodegradable cellulose-based hydrogels: design and applications. Materials 2009, 2, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikdar, P.; Uddin, M.M.; Dip, T.M.; Islam, S.; Hoque, M.S.; Dhar, A.K.; Wu, S. Recent advances in the synthesis of smart hydrogels. Materials Advances 2021, 2, 4532–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Murphy, S.B.; McEvoy, H. Fundamentals of hydrogels and gelation. British polymer journal 1986, 18, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Brannon, J.H. Concentration dependence of the distribution coefficient for macromolecules in porous media. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Physics Edition 1981, 19, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Nuvoli, L.; Sanna, D.; Alzari, V.; Nuvoli, D.; Rassu, M.; Malucelli, G. Semi-interpenetrating polymer networks based on crosslinked poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide) and methylcellulose prepared by frontal polymerization. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2018, 56, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellá, M.C.; Lima-Tenório, M.K.; Tenório-Neto, E.T.; Guilherme, M.R.; Muniz, E.C.; Rubira, A.F. Chitosan-based hydrogels: From preparation to biomedical applications. Carbohydrate polymers 2018, 196, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevam, B.R.; dos Santos Vieira, F.F.; Gonçalves, H.L.; Moraes, Â.M.; Fregolente, L.V. Cellulose hydrogels for water removal from diesel and biodiesel: Production, characterization, and efficacy testing. Fuel 2023, 347, 128449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, R.; Mahada, P.; Chhirang, B.; Das, B. Cellulose hydrogels: Green and sustainable soft biomaterials. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 5, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.C.; Leh, C.P.; Goh, C.F. Designing cellulose hydrogels from non-woody biomass. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 264, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyanga, K.A.; Iamphaojeen, Y.; Daoud, W.A. Effect of zinc ion concentration on crosslinking of carboxymethyl cellulose sodium-fumaric acid composite hydrogel. Polymer 2021, 225, 123788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.C.; Saraiva, J.N.; Cavaco, G.; Portela, R.P.; Leal, C.R.; Sobral, R.G.; Almeida, P.L. Crosslinked bacterial cellulose hydrogels for biomedical applications. European Polymer Journal 2022, 177, 111438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotolářová, J.; Vinter, Š.; Filip, J. Cellulose derivatives crosslinked by citric acid on electrode surface as a heavy metal absorption/sensing matrix. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 628, 127242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M. Construction of self-assembled polyelectrolyte complex hydrogel based on oppositely charged polysaccharides for sustained delivery of green tea polyphenols. Food chemistry 2020, 306, 125632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanikireddy, V.; Varaprasad, K.; Jayaramudu, T.; Karthikeyan, C.; Sadiku, R. Carboxymethyl cellulose-based materials for infection control and wound healing: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 164, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gao, J. Investigation on ionical cross-linking of alginate by monovalent cations to fabrication alginate gel for biomedical application. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2023, 183, 105484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mehan, S.; Tiwari, A.; Khan, Z.; Das Gupta, G.; Narula, A.S.; Samant, R. Magnesium (Mg2+): Essential Mineral for Neuronal Health: From Cellular Biochemistry to Cognitive Health and Behavior Regulation. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2024, 30, 3074–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.S.; Nguyen, H.; Illikainen, S.; Alzeer, M.I.; Cunha, S.; Kinnunen, P. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate on the Precipitation Mechanism of Mg Carbonates. Crystal Growth & Design 2024, 24, 7044–7058. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Mathpal, M.C.; Ghosh, S.; Inwati, G.K.; Maze, J.R.; Duvenhage, M.-M.; Roos, W.D.; Swart, H.C. Plasmonic Au nanoparticles embedded in glass: Study of TOF-SIMS, XPS and its enhanced antimicrobial activities. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2022, 909, 164789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpomie, K.G.; Ghosh, S.; Gryzenhout, M.; Conradie, J. One-pot synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles via chemical precipitation for bromophenol blue adsorption and the antifungal activity against filamentous fungi. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Mathpal, M.C.; Inwati, G.K.; Ghosh, S.; Kumar, V.; Roos, W.D.; Swart, H.C. Optical and surface properties of Zn doped CdO nanorods and antimicrobial applications. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 605, 125369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Inwati, G.K.; Mathpal, M.C.; Ghosh, S.; Roos, W.D.; Swart, H.C. Defects induced enhancement of antifungal activities of Zn doped CuO nanostructures. Applied Surface Science 2021, 560, 150026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpomie, K.G.; Ghosh, S.; Gryzenhout, M.; Conradie, J. Ananas comosus peel–mediated green synthesized magnetite nanoparticles and their antifungal activity against four filamentous fungal strains. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 13, 5649–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateyise, N.G.S.; Ghosh, S.; Gryzenhout, M.; Chiyindiko, E.; Conradie, M.M.; Langner, E.H.G.; Conradie, J. Synthesis, characterization, DFT and biological activity of oligothiophene β-diketone and Cu-complexes. Polyhedron 2021, 205, 115290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthus, L.; Estevam, B.R.; Aguila, Z.J.; Maciel, M.R.W.; Fregolente, L.V. Facile tuning of hydrogel properties for efficient water removal from biodiesel: An assessment of alkaline hydrolysis and drying techniques. Chemical Engineering Science 2023, 282, 119224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassanelli, M.; Prosapio, V.; Norton, I.; Mills, T. Role of the drying technique on the low-acyl gellan gum gel structure: molecular and macroscopic investigations. Food and bioprocess technology 2019, 12, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, A.; Choubey, A.; Bajpai, A. Biosorption of chromium ions by calcium alginate nanoparticles. Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society 2018, 63, 4077–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Biochar prepared from co-pyrolysis of municipal sewage sludge and tea waste for the adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solutions: Kinetics, isotherm, thermodynamic and mechanism. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2016, 220, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, N.M.; Hayati, B.; Arami, M. Kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies of ternary system dye removal using a biopolymer. Industrial Crops and Products 2012, 35, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Y. Effects of sodium salt types on the intermolecular interaction of sodium alginate/antarctic krill protein composite fibers. Carbohydrate polymers 2018, 189, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Gao, X.; Xiong, G.; Liang, J. Preparation and antioxidant activity of sodium alginate and carboxymethyl cellulose edible films with epigallocatechin gallate. International journal of biological macromolecules 2019, 134, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoratto, N.; Matricardi, P. Semi-IPNs and IPN-based hydrogels. Polymeric gels 2018, 91–124. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, A.; Smidsrød, O.; Högdahl, B.; Øye, H.; Rasmussen, S.; Sunde, E.; Sørensen, N.A. Selectivity of some anionic polymers for divalent metal ions. Acta chem. scand 1970, 24, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidsrod, O.; Haug, A. Properties of Poly (l, 4-hexuronates) in the Gel State. Acta Chem Scand 1972, 26, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Mørch, Ý.A.; Donati, I.; Strand, B.L.; Skjåk-Bræk, G. Effect of Ca2+, Ba2+, and Sr2+ on alginate microbeads. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Verduijn, J.; Van der Meeren, L.; Huang, Y.; Vallejos, L.C.; Skirtach, A.G.; Parakhonskiy, B.V. Alginate-CaCO3 hybrid colloidal hydrogel with tunable physicochemical properties for cell growth. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 259, 129069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.S.; Estevam, B.R.; Perez, I.D.; Américo-Pinheiro, J.H.P.; Isique, W.D.; Boina, R.F. Sludge from a water treatment plant as an adsorbent of endocrine disruptors. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 108090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F.B., S.; I.D., P.; G.T., G.; M.G., V.; L.V., F.; M.R., W.M. Study of the Kinetics Swelling of Poly(acrylamide-co-acrylonitrile) Hydrogel for Removal of Water Content from Biodiesel. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 2020, 80, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Giz, A.S.; Berberoglu, M.; Bener, S.; Aydelik-Ayazoglu, S.; Bayraktar, H.; Alaca, B.E.; Catalgil-Giz, H. A detailed investigation of the effect of calcium crosslinking and glycerol plasticizing on the physical properties of alginate films. International journal of biological macromolecules 2020, 148, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Pan, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of silver nanoparticles by sodium alginate and their applications in surface-enhanced Raman scattering and catalysis. Acta Materialia 2012, 60, 4753–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, X.; Zheng, C.; Wang, X.; Sun, R. Facile and green synthesis of silver nanoparticles in quaternized carboxymethyl chitosan solution. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 235601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

SEM images of the SA/HEC hydrogels cross-linked by Ca2+ ions, in various forms. The inset shows the photographs of the various forms of the hydrogels.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the SA/HEC hydrogels cross-linked by Ca2+ ions, in various forms. The inset shows the photographs of the various forms of the hydrogels.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the SA/HEC films cross-linked by Ca2+/Mg2+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the SA/HEC films cross-linked by Ca2+/Mg2+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions.

Figure 3.

The FTIR spectra of the SA/HEC, SA/HEC/Ca/Mg, SA/HEC/Ca.

Figure 3.

The FTIR spectra of the SA/HEC, SA/HEC/Ca/Mg, SA/HEC/Ca.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the SA/HEC hydrogels cross-linked by (A) Ca2+ ions and (B) Ca2+/Mg2+ ions.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the SA/HEC hydrogels cross-linked by (A) Ca2+ ions and (B) Ca2+/Mg2+ ions.

Figure 5.

EDX analysis of (A) SA/HEC/Ca/Mg, and SA/HEC/Ca, hydrogels.

Figure 5.

EDX analysis of (A) SA/HEC/Ca/Mg, and SA/HEC/Ca, hydrogels.

Figure 6.

Water Stability of the SA/HEC beads crosslinked by Ca2+ and co-crosslinked by Ca2+/Mg2+.

Figure 6.

Water Stability of the SA/HEC beads crosslinked by Ca2+ and co-crosslinked by Ca2+/Mg2+.

Figure 7.

XRD spectra of (a) SA/HEC, (b) SA/HEC/Ca and (c) SA/HEC/Ca/Mg hydrogels.

Figure 7.

XRD spectra of (a) SA/HEC, (b) SA/HEC/Ca and (c) SA/HEC/Ca/Mg hydrogels.

Figure 8.

Normalized TGA curves (a), SA/HEC (b) SA/HEC/Ca/Mg (c) SA/HEC/Ca.

Figure 8.

Normalized TGA curves (a), SA/HEC (b) SA/HEC/Ca/Mg (c) SA/HEC/Ca.

Figure 9.

UV-Visible absorption spectrum of the SA/HEC/AgNP hydrogel.

Figure 9.

UV-Visible absorption spectrum of the SA/HEC/AgNP hydrogel.

Figure 10.

SEM images of the SA/HEC/AgNP/hydrogels cross-linked by (A) Ca2+ ions, (C) Ca2+/Mg2+ ions and the EDX of SA/HEC/AgNP/Ca hydrogels (B), and SA/HEC/AgNP/Ca/Mg hydrogels (D).

Figure 10.

SEM images of the SA/HEC/AgNP/hydrogels cross-linked by (A) Ca2+ ions, (C) Ca2+/Mg2+ ions and the EDX of SA/HEC/AgNP/Ca hydrogels (B), and SA/HEC/AgNP/Ca/Mg hydrogels (D).

Figure 11.

Media plates showing the inhibition zone across a range of compounds [Sodium Alginate—Silver nanoparticles (SA-AgNPs); Hydroxyethyl cellulose-silver nanoparticles (HC-AgNPs); Sodium Alginate—Hydroxyethyl cellulose—silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-AgNPs); Sodium Alginate-Hydroxyethyl cellulose—Calcium/silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-Ca/AgNPs); Sodium Alginate- Hydroxyethyl cellulose-Calcium/Magnesium -silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-Ca/Mg-AgNPs)] against the bacterial strains E. coli ATCC 25922 (A–E), S. aureus ATCC 29213 (F–J) and fungal strains C. albicans ATCC 14053 (K) and C. kruzei ATCC 6258 (L). The red and blue arrow heads are designated for undiluted and diluted compounds, respectively, while the black indicates the Ciprofloxacin/Amoxycillin positive control for bacteria and amphotericin B(S) positive control for fungi. The yellow arrow heads specify the sterile water negative control.

Figure 11.

Media plates showing the inhibition zone across a range of compounds [Sodium Alginate—Silver nanoparticles (SA-AgNPs); Hydroxyethyl cellulose-silver nanoparticles (HC-AgNPs); Sodium Alginate—Hydroxyethyl cellulose—silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-AgNPs); Sodium Alginate-Hydroxyethyl cellulose—Calcium/silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-Ca/AgNPs); Sodium Alginate- Hydroxyethyl cellulose-Calcium/Magnesium -silver nanoparticles (SA-HEC-Ca/Mg-AgNPs)] against the bacterial strains E. coli ATCC 25922 (A–E), S. aureus ATCC 29213 (F–J) and fungal strains C. albicans ATCC 14053 (K) and C. kruzei ATCC 6258 (L). The red and blue arrow heads are designated for undiluted and diluted compounds, respectively, while the black indicates the Ciprofloxacin/Amoxycillin positive control for bacteria and amphotericin B(S) positive control for fungi. The yellow arrow heads specify the sterile water negative control.

Table 1.

Mechanical characteristics for SA/HEC/Ca2+, and SA/HEC/Ca2+/Mg2+ films.

Table 1.

Mechanical characteristics for SA/HEC/Ca2+, and SA/HEC/Ca2+/Mg2+ films.

| Hydrogel Film |

Modulus (MPa) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Elongation at Break (%) |

| SA/HEC/Ca2+ |

138 |

0.90 |

6.15 |

| SA/HEC/Ca2+/Mg2+ |

118 |

0.19 |

11.4 |

Table 2.

TGA data before and after cross-linking SA/HEC hydrogels.

Table 2.

TGA data before and after cross-linking SA/HEC hydrogels.

| Sample |

Region of |

Temperature |

| |

Decomposition |

Tpeak |

| SA/HEC |

1 |

50.83 |

| |

2 |

215 |

| |

3 |

625.35 |

| SA/HEC/Ca |

1 |

51.23 |

| |

2 |

225 |

| |

3 |

629.85 |

| SA/HEC/Ca/Mg |

1 |

63.83 |

| |

2 |

230 |

| |

3 |

640.02 |

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activities of all the tested compounds.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activities of all the tested compounds.

| Microorganisms |

E. coli ATCC 25922 |

S. aureus ATCC 29213 |

C. albicans ATCC 14053 |

C. kruzei ATCC 6258 |

| Zone of Inhibitions (mm) |

| Positive controls |

29 |

|

36 |

|

40 |

35 |

| Negative controls |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Compounds |

Undiluted |

diluted |

Undiluted |

diluted |

Undiluted |

Undiluted |

|

a SA-AgNPs |

20 |

18 |

- |

- |

25 |

25 |

|

b HEC-AgNPs |

22 |

15 |

16 |

15 |

40 |

40 |

|

c SA-HEC-AgNPs |

14 |

- |

- |

11 |

25 |

30 |

|

d SA-HEC-Ca/AgNPs |

23 |

24 |

19 |

18 |

45 |

45 |

|

e SA-HEC-Ca/Mg-AgNPs |

21 |

18 |

11 |

19 |

30 |

35 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).