1. Introduction

This study aimed to gather critical data on the effectiveness of localized irrigation in nursery apricot cultivation to obtain robust seedlings. The scientific importance of our research lies in its ability to generate valuable information for orchard specialists and nursery owners. It plays a key role in resource optimization, allowing nursery operators to use water more efficiently—reducing waste and lowering costs without sacrificing the quality of the planting material. The practical application of these findings leads to the production of apricot seedlings that are more vigorously branched, healthier, and better suited for successful establishment in orchards. Ultimately, the research transforms observation and experimentation into practical knowledge that is vital for the development and sustainability of the fruit-growing sector.

The main aim of a nursery is to produce healthy, vigorous and, above all, well-branched seedlings. Producing well-branched seedlings in the nursery represents a fundamental goal for any producer committed to high-quality planting material. Sufficient branching transforms an ordinary seedling into a young tree with a pre-formed crown structure, enabling earlier fruiting and ensuring greater productivity once established in the orchard [

1]. Research in this field provides valuable insights into the factors that govern the formation of branching, such as light, moisture, nutrient levels, hormones, and specific pruning techniques. By optimising these elements, it becomes possible to cultivate seedlings with an optimal crown architecture directly in the nursery—ultimately increasing their value and performance once planted in the orchard. Trees that possess well-developed branching from the moment they are planted in the orchard typically reach fruiting maturity more quickly [

2]. Research aimed at stimulating early branching in the nursery plays a direct role in reducing the non-productive period of orchard trees while accelerating financial returns for growers. Studies focused on branching have demonstrated that a well-formed crown structure—ensuring efficient light distribution, proper air circulation, and maximum fruiting surface—leads to superior fruit quality in terms of size, colour, and sugar content [

3,

4]. Such trees also deliver higher and more uniform yields over time. Additionally, optimally branched seedlings require less intervention for crown formation during the initial years in the orchard, which significantly cuts labour time and associated costs [

5]. Branching is an essential element in the structure of a fruit tree, playing a crucial role in its growth, development, and especially in fruit production. The way branches form and evolve directly affects crown architecture, tree vigour, and the overall efficiency of fruiting [

6].

A proper water regime is crucial for encouraging the branching development of seedlings in the nursery. Insufficient water leads to stress, which suppresses vegetative growth and hinders branching. Conversely, excessive watering can promote the onset of diseases or root rot. Localised irrigation is often the most effective method, delivering water directly to the roots, minimising wastage and providing optimal conditions for growth [

7,

8]. The interaction between water and branch growth in fruit trees, especially in the nursery, is fundamental and complex. Water is not just a simple nutrient, but a key factor directly influencing the physiological and hormonal processes governing the initiation and development of lateral branches. It is also essential for maintaining cell turgor. Well-hydrated cells have a high internal pressure that allows them to expand and divide efficiently. Cell expansion determines the elongation of shoots. In the absence of sufficient turgor pressure, this growth is either slowed or stunted, which in turn negatively impacts the formation of new branches. Rapid and sustained vegetative growth of the main stem is often a precondition for stimulating branching. Even minimal water stress in plants can slow their growth and hinder the formation of lateral shoots [

9].

High temperatures and drought adversely affect the growth of horticultural plants by hindering cell division and cell expansion. These conditions lead to visible changes such as thickening of the leaves and cuticle, a decrease in the number of stomata, and wilting of the plant. Leaves may change position, drop prematurely (abscission), and the number of aquaporins (proteins that help transport water) changes. With wilting, the leaves often turn yellow and develop necrotic areas around the edges, stunting the plant’s growth and reducing its size. Drought accelerates ageing and leaf drop at the base of the plant, reducing total leaf area and transpiration. When faced with significant water deficiency, cells lose turgor pressure, leading to the cessation of growth, diminished gas exchange, and a shift where respiration surpasses photosynthetic activity [

10,

11]. Global climate change causes significant fluctuations in temperature and precipitation, exposing plants to stress. Of these, drought is a major abiotic stress, severely limiting plant growth and productivity. It destructively alters the anatomical, physiological and morphological characteristics of crops, impacting food security. However, temporary soil water deficiency, varying by species, does not have dramatic consequences due to the ability of plants to redistribute water internally. Water is transported from the roots to the aerial organs, and water in the apoplast penetrates into the leaf cells, restoring turgor and providing optimal conditions for metabolism. Additional strategies plants use to minimize water loss during drought stress include thickening of the cuticle, reduced stomatal density, and the build-up of gel-like haemicellulins in cell walls to aid in water retention [

12].

Irrigation primarily serves to stabilize crop yields by helping plants reach their full potential, regardless of soil and weather limitations. Studies conducted locally have consistently shown that inadequate rainfall during critical growth stages can lead to severe yield losses, even resulting in total crop failure [

13]. Consequently, irrigation should be regarded not merely as a developmental enhancement, but as a fundamental requirement for maintaining the consistency and reliability of agricultural output in Romania. In recent years, Romania has experienced increasingly frequent and severe droughts. As a result, irrigation has become indispensable for supplementing natural precipitation, particularly during critical periods of water scarcity that hinder crop development. Practically speaking, irrigation now plays a vital role in mitigating climate-related irregularities that contribute to significant annual yield variability.

Nurseries, which depend on a consistent water supply for optimal seedling development, are particularly vulnerable to drought conditions. Water stress leads to stunted growth, preventing seedlings from reaching the desired vigour and size. It also inhibits lateral branching, resulting in lower-quality planting material. To compensate, irrigation must be applied more frequently and in larger volumes, significantly increasing production costs [

14]. Moreover, prolonged drought lowers the water table, reducing groundwater reserves and limiting access to water from wells and boreholes commonly used in nursery operations. Nursery irrigation is an essential component of the cropping system, representing more than a simple application of water; it is a fundamental agronomic practice, based on complex scientific principles, aimed at ensuring optimal growth and development of the planting material. The success of the irrigation programme depends on a thorough understanding of the interactions between plant, substrate, and environmental conditions to maintain a proper water balance in the root zone [

15]. Various factors affect how much water nursery trees require, the most important among them being the species and the cultivar, the stage of development of the plant, the type of rootstock, the climatic conditions and the physical-chemical characteristics of the growing medium. During their first year of growth, young trees possess underdeveloped root systems, limiting their ability to access water from deeper soil layers. As a result, they require more frequent irrigation to meet their moisture needs and support healthy establishment. As trees develop, absolute water requirements increase, although tolerance to longer intervals between watering may increase. Nursery water management is a fundamental component of modern horticulture, with direct implications for plant viability, resource efficiency and sustainability of operations. A methodical approach grounded in scientific principles is vital for enhancing plant growth and development, reducing production losses, and mitigating adverse environmental effects [

16].

Apricot

(Prunus armeniaca) is a widely valued fruit tree species in Romania, prized for its aromatic and flavourful fruit, suitable for both fresh consumption and processing. However, apricot cultivation in Romania involves notable opportunities and challenges, which are largely dictated by the species’ specific climate and soil requirements, as well as its distinct biological traits. Although mature apricot trees are relatively drought-tolerant, efficiently utilizing winter-stored soil moisture, young seedlings — particularly in nurseries and during the initial years after planting — have specific and sensitive water requirements that demand careful irrigation management. Ensuring an optimal amount of water is fundamental for healthy growth, adequate branching and guaranteed establishment success [

17],. Romania has significant potential for apricot production, ranking among the top producers in the European Union (sixth place in production and third place in productivity per hectare, according to recent data). However, production fluctuates from year to year due to climatic conditions. Although the extent of cultivated areas has declined significantly, recent years have seen a gradual recovery, driven by renewed investments in orchard establishment—many of which are supported by European funding programs. For this reason, there is a need for the production and supply of good quality and vigorous planting material.

This research aims to optimise irrigation strategies to produce high-quality, early-branching, and vigorous apricot seedlings in the nursery—ensuring strong establishment and accelerated growth in the orchard. Monitoring branching development during the nursery phase is critical for evaluating seedling vigour, refining cultivation techniques, and guaranteeing superior planting material. The study investigates how varying irrigation regimes affect branch length, with the goal of cultivating seedlings with a well-balanced structure that supports efficient crown formation in later stages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Environmental Context of the Research: Soil and Climate Conditions

The experimental field lies in the northwestern region of Romania, positioned at 47°03’ N latitude and 21°56’ E longitude. This area features a lowland geomorphology, with elevations between 80 and 190 meters above sea level. Its flat terrain supports a stable distribution of weather patterns throughout the year. The rivers that flow across the plain have shallow channels and are not bordered by terraces. Climatic data are obtained directly from this field, using on-site instruments including a rain gauge and a thermometer to ensure precise measurement of local conditions.

As shown in

Table 1, the average annual temperature was 12.64 °C. August was the warmest month, recording a peak of 24.1 °C, while December marked the coldest period of the year.

In 2024, monthly precipitation varied significantly, with a range of 114.9 mm.

Table 2 indicates that the lowest rainfall was recorded in October, at 12.7 mm, whereas July experienced the highest level at 127.6 mm.

In 2024, precipitation levels were predominantly below average, showing negative deviations ranging from 4 mm to 35 mm. However, four months—most notably June and July—experienced significant rainfall increases, with positive deviations between 21 mm and 80 mm. Following this wetter period, a drier phase emerged, characterized by below-average precipitation compared to multi-year norms. Despite these fluctuations, the year as a whole was considered abundant in precipitation.

Relative humidity was significantly influenced by the prevailing wind regime. The most frequent winds originated from the northeast and southwest, while the strongest gusts came from the south and southeast. Analysing the monthly progression of wind patterns revealed that in November and February, winds from the south and north dominated. From March onward, easterly winds gained prominence, becoming the predominant direction by September.

High wind speeds posed a threat to vegetation, especially where trees were vulnerable at grafting points. Relative humidity exhibited considerable variation throughout the year, ranging from 20% in August to a peak of 92% in December. (

Table 3).

The soil in the experimental field is of the Eutricambosol type, belongs to the cambisols class, it is a moderately texturally differentiated soil with moderately favourable aerobic properties. It has a medium clay content and the soil reaction is moderately weakly acidic.

On the soil profile, horizons show the following characteristics:

- Am 0-30 cm, brown, small glomerular, medium loam

- ABw 30-60 cm, light brown, small angular polyhedral, medium clay loam

- BvG 60- 90 cm, yellowish brown, medium angular polyhedral, medium clayey loam

2.2. Material and Research Method

The study was designed to investigate the primary influence of the irrigation regime and the secondary influence of the cultivar on the analysed variables. This methodological approach allowed the assessment of the predominant impact of water availability, while analysing the differential effects of specific genotypes within each applied water regime. Irrigation was therefore the primary factor of interest, while cultivar was a subordinate factor utilised to refine the understanding of plant-specific interactions and responses. The study was structured as a randomised block experiment with three repetitions per treatment, each repetition involving 10 trees. Four irrigation regimes were implemented: no irrigation, and irrigation levels of 10 mm, 20 mm, and 30 mm. The selected irrigation treatments correspond to the most widely used water volumes tailored to the prevalent soil profiles and climatic conditions found in Romania, underscoring their relevance to prevailing agricultural practices. Irrigation was conducted using a drip tape system with a diameter of 16 mm and a thickness of 0.2 mm, with drippers spaced at 25 cm intervals. The system operated at a pressure of 0.7 bar, delivering water at a rate of 1.5 L/ha. Irrigation scheduling was regulated based on soil moisture dynamics, with the 10 mm treatment timed to coincide with reaching the critical threshold of 19.58% soil moisture. Thus, in the year 2024, irrigation was applied on July 15th, August 10th, August 20th and August 25th. Two Romanian apricot cultivars were used for grafting. During the research, the first-order branching of trees in the nursery was measured. First order branches are the main branches that develop directly from the trunk or axis of the tree. They form the basic structure of the tree. They are the first major branches that grow directly from the trunk or centre axis. They are the thickest and strongest branches in the crown and are essential for supporting the entire tree structure, including the higher order branches, leaves, flowers and fruit. A ruler was employed to determine the length of each first-order branch, measured from its base to the growing tip. In each replicate, a single vigorous, healthy, and well-developed tree was selected for this assessment. Measurements were conducted at the end of the 2024 growing season, in autumn, to capture the total growth achieved.

The initial biological material was grafted with dormant eyes from the Excelsior and Favorit apricot cultivars. The Excelsior variety ripens from August 1st to August 10th; fruit size is large to very large (over 70 g); fruit shape is spherical and elongated; the skin is pubescent (with fine hairs), yellowish on the shaded side and red on the sunny side (on about 40-50 % of the surface). The fruit has a yellow-coloured flesh that is firm and moderately juicy, with a texture that does not readily separate from the stone. Its flavour is well-balanced and intensely aromatic. This variety is suitable both for fresh consumption and for processing into products such as jam, nectar, and compote. The ‘Favorit’ cultivar ripens from August 10th to August 20th; the fruit is large (50-60 g) and ovoid in shape; the skin is thin, orange on the shady side and red on the sunny side (about 40-50 % of the surface). The flesh of the fruit is orange in colour, firm, with medium juiciness, not tender to the stone; balanced, intensely aromatic taste. Like the Excelsior variety, the fruits of the Favorit variety are used for fresh consumption and for processing into jam, jam, nectar, compote [

18].

2.3. Analysis of Water Balance and Water Consumption Under Different Irrigation Conditions in the Experimental Field

During 2024, the initial soil water reserve in April—marking the start of the growing season—recorded values of 2.367-2.458 m

3/ha, equivalent to 84.3-87.54% of the field water capacity, thus ensuring an optimum level for seedling growth (

Table 4).

The April rainfall maintained, at the beginning of May, the soil water supply at values close to those of the previous month, i.e., 2.380-2.443 m3/ha. The abundant rainfall in May and June led to a significant increase in soil moisture, which at the end of June was 2.743-2.784 m3/ha.

High temperatures in July combined with low rainfall resulted in a significant decrease in soil moisture to below the minimum threshold of 2.112 m3/ha. As a result of the circumstances in July, it became necessary to implement an irrigation rate matching that of the three experimental variants of 100, 200 and 300 m3/ha. Under the effect of this watering, the soil water reserve at the end of July was between 2.158 and 2.204 m3/ha.

In August, with weather conditions resembling those in July—marked by elevated temperatures and limited rainfall—the decline in soil moisture intensified, leading to a reduction in the water reserves to 1.491-1.652 m3/ha, well below the minimum threshold. Therefore, to compensate for this significant water deficit, three irrigations, equivalent to irrigation norms of 300, 600 and 900 m3/ha, were applied. The use of irrigation ensured that the soil moisture content was maintained at levels between 1.952-2.391 m3/ha.

During the month of September there was an intensification of the water shortage, which caused a decrease in the soil water supply to levels ranging from 1.494 m3/ha for the non-irrigated version to 2.046 m3/ha for the 30 mm irrigated version. Therefore, in the case of the non-irrigated variant, the water stress conditions in August and September affected the growth and development of seedlings.

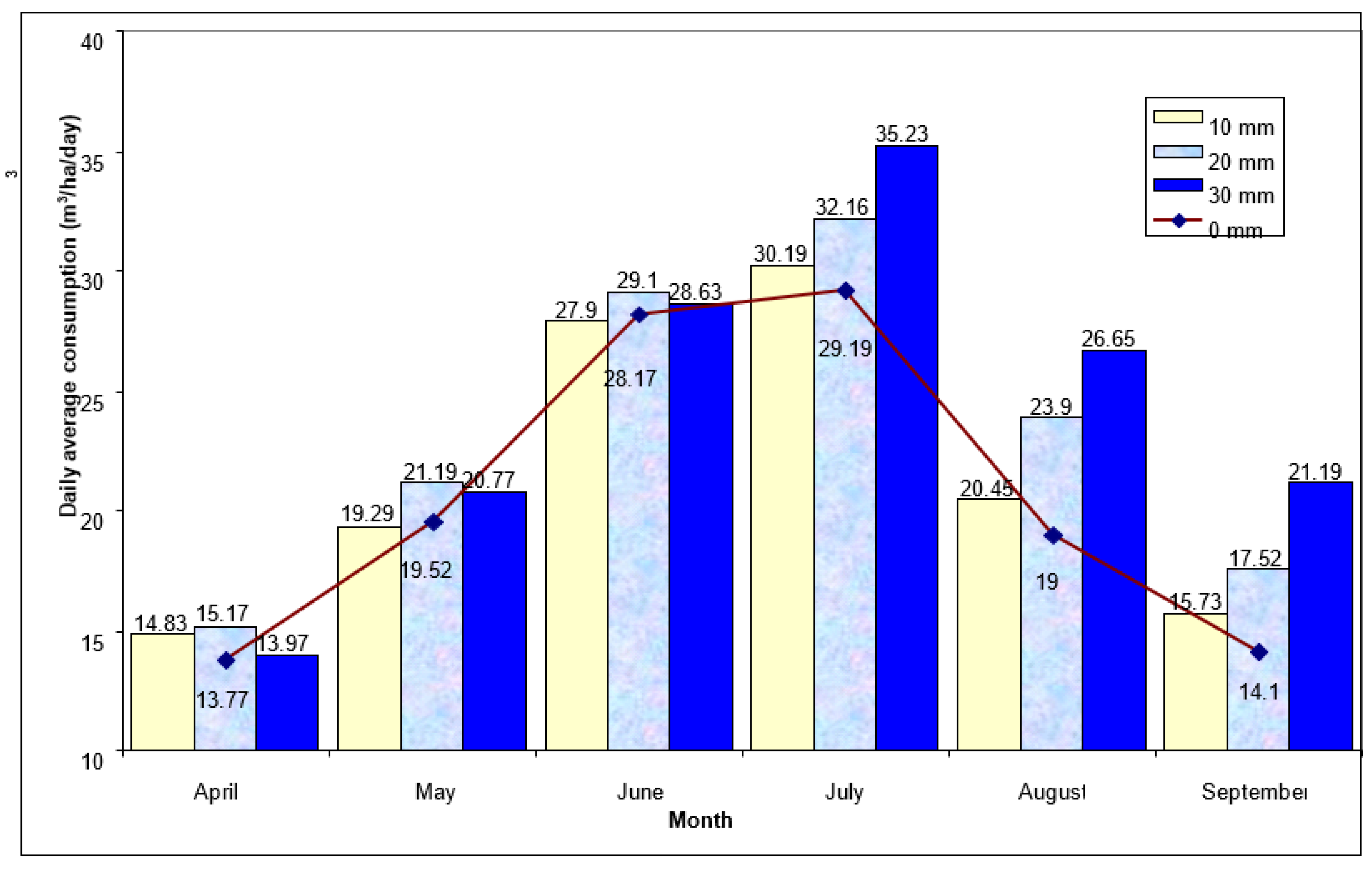

The average daily water consumption at the beginning of the growing season was 13.77-15.17 m

3/ha in April and 19.29-21.19 m

3/ha in May (

Figure 1), respectively, and then gradually increased until August when it reached maximum levels ranging from 29.19 m

3/ha for the non-irrigated variant to 35.23 m

3/ha for the 30 mm watering standard variant.

Water usage in August and September showed a reduction corresponding to the watering rules applied. For the non-irrigated variant, average daily consumption in August fell by about 35 %, compared with the previous month, while for the 30 mm irrigated variant daily consumption fell by only 24 %.

In September, water consumption was intermediate between April and May, ranging from 14.1 m3/ha for the non-irrigated variant to 21.19 m3/ha for the 30 mm irrigated variant. The application of irrigation in July and August led to a variation in water consumption proportional to the applied watering rule.

3. Results

With regard to the one-sided effect of irrigation (

Table 5), the growth of first-order branching showed a range of variation of 183.1 cm/inch, with mean values ranging from 53.1 cm/inch for the non-irrigated variant to 236.2 cm/inch for the 30 mm watering rule, with high variability among the four irrigation treatments. Over the whole experiment under the climatic conditions of 2024, irrigation had a significant effect on branching growth, with increases ranging from 138.98 to 344.82 %. Increasing the watering standard from 10 to 20 mm significantly influenced this characteristic with a 53.19% increase, while changing the watering standard from 20 to 30 mm resulted in a significant 21.5% increase in first-order branching.

Considering the cumulative effect of the cultivar, in the year when the research was conducted (

Table 6), average values of total branching growth were found with limits ranging from 145.9 cm for Excelsior to 159.4 cm/cm for Favorit. As such, in general, the seedlings of the Favorit cultivar had significantly higher first-order branching growth by about 9.3%.

As regards the interaction between cultivars and irrigation (

Table 7), it can be seen that in both cultivars irrigation and showed significantly positive influences on branching growth, amid higher effects in the Favorit cultivar.

Considering the impact of irrigation on branch growth across different cultivars,

Table 4 highlights that for Excelsior, branch length varied significantly—from 22.5 cm under non-irrigated conditions to 231.2 cm with the application of the 30 mm watering protocol.

This irrigation strategy resulted in a dramatic increase of over 460% compared to the non-irrigated control. Moreover, increasing the watering volume from 10 mm to 20 mm led to a marked enhancement in branch development, by 61.5 %. Increasing the watering rate from 20 to 30 mm also resulted in a significant increase of 13.44%.

For the seedlings of the Favorit cultivar, the variability between the effects of irrigation was associated with an amplitude of 157.4 cm, ranging from 83.8 cm under non-irrigated conditions to 241.2 cm for the 30 mm watering protocol.

All three watering standards led to notable increases in branching, with improvements ranging from 52%-187.83%, as shown in

Table 8. Irrigation supplementation from 10 to 20 mm resulted in a significant 45.1 % increase in this characteristic, while changing the dose from 20 to 30 mm showed a significant positive influence of 30.38 %.

Considering the influence of cultivar on first-order branch growth under different irrigation treatments,

Table 9 indicates that growth amplitudes ranged from 1.3 cm under the 10 mm irrigation standard to 61.3 cm in the absence of irrigation.

Based on these differences, it is obvious that the Favorit cultivar exhibited notably greater branching growth under non-irrigated conditions, while the seedlings of the Excelsior variety significantly better exploited the 20 mm irrigation conditions. The response of both cultivars to irrigation followed a consistent upward trend under the 10 mm and 30 mm treatments.

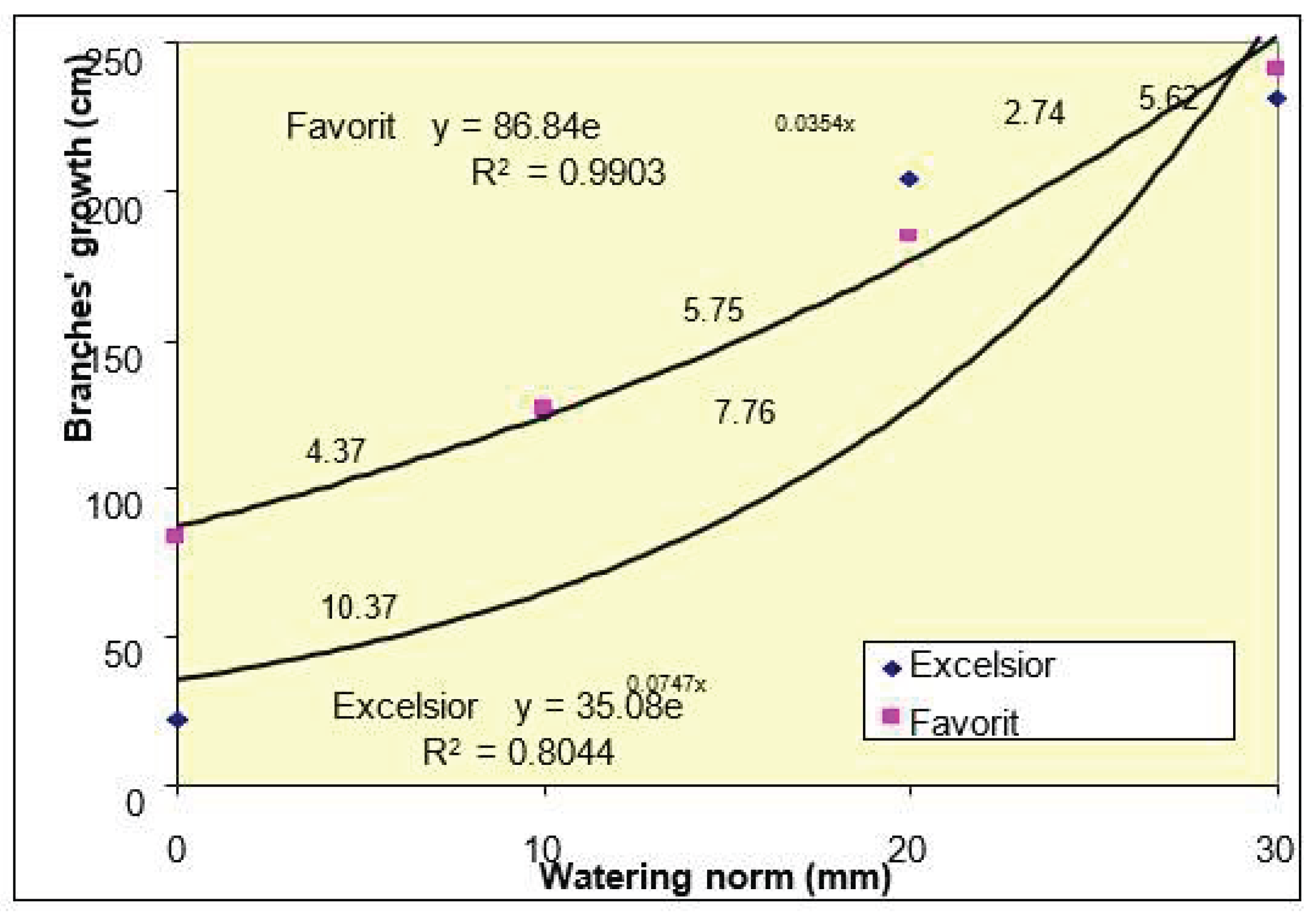

Figure 1 illustrates, based on the exponential regression, that the Favorit cultivar showed an average growth rate of 5.24 cm for each mm of watering. The estimates demonstrate a 99% level of accuracy, assuming an average branch growth of approximately 87 cm under non-irrigated conditions.

Figure 2 illustrates that, for the Excelsior cultivar, irrigation had a pronounced effect on branching growth, with an average increase of 6.95 cm/mm, against a background of higher variations (7.76-10.37 cm/mm) for the first two watering norms and a low variation (2.74 cm/mm) between the 20 mm and the 30 mm norm. The logarithmic regression describing the relationship between irrigation rate and branching growth in the Excelsior cultivar exhibits lower predictability compared to that observed in the other variety, based on an initial value of 35.08 cm/mm, in the absence of irrigation.

4. Discussion

Irrigation management in nursery settings represents a critical, yet highly controllable factor influencing the branching development of apricot seedlings, according to Miller [

19]. Within the regulated conditions of the nursery, where the objective is to cultivate high-quality planting material, optimizing the irrigation regime is essential for promoting seedlings with well-developed crowns and robust root systems. In nursery production, apricot seedlings require sustained and vigorous growth to attain the optimal size and quality for transplantation. Consistent irrigation supports this development by ensuring steady access to water and nutrients, which drives cellular activity and internodal expansion. This, in turn, contributes to the formation of longer, thicker shoots and enhances the branching potential of the seedlings. While the primary objective in nursery cultivation is vegetative development, balanced irrigation can also play a role in promoting flower bud differentiation. Vigorous early branching contributes to a greater number of potential sites for bud formation following transplantation into the orchard. Significant fluctuations in water availability—such as alternating periods of drought and excessive irrigation—can impose physiological stress on seedlings, manifesting in symptoms such as stunted growth, wilting, defoliation, and reduced branching [

20]. To support consistent development in nursery conditions, it is essential to maintain stable humidity levels. Additionally, effective soil drainage is critical to avoid water stagnation, which may cause root asphyxiation and promote the onset of fungal infections, thereby compromising both shoot architecture and overall seedling vitality.

Research into the irrigation of fruit trees in nurseries has consistently highlighted the fundamental role of precise water management in determining the successful cultivation of high-quality planting material. According to Kadyampakeni, optimal hydraulic regime is not merely a necessary condition for plant survival, but a crucial factor directly influencing the morphological and physiological development of seedlings, their capacity to adapt to transplanting, and, consequently, their potential for growth and yield in the orchard. The research has also underscored the stringent necessity for individualizing irrigation schedules [

21]. Parameters such as the fruit tree species and cultivar, its developmental stage (from germination to orchard-ready saplings), the type of growing substrate (which influences water retention capacity and drainage), and the specific microclimatic conditions within the nursery (temperature, relative humidity, wind speed) necessitate continuous adjustments to the quantity and frequency of watering [

22]. For instance, recently transplanted or grafted seedlings require a more constant water supply to support root system regeneration and callusing, while plants reaching a certain stage of maturity may benefit from short periods of controlled stress to stimulate tissue lignification and prepare the plant for field conditions [

23].

Effective irrigation management in nursery operations is critical to produce high-quality planting material, capable of successful establishment and uniform development following transplantation. Efficient water management not only ensures optimal branching growth, but also promotes overall plant health and enhances the economic efficiency of the nursery.