1. Introduction

For complex, high-dimensional, and nonlinear optimization problems, it may be challenging to find the optimal solution using traditional optimization algorithms. In contrast, meta-heuristic algorithms do not rely on the specific structure or characteristics of the problem. Instead, they iteratively explore the solution space by simulating natural systems or other phenomena from real life to search for the optimal solution. These algorithms have proven highly effective in addressing such complex problems and have been widely utilized across diverse domains including engineering, science, business and so on. Within the paradigm of meta-heuristics, numerous Swarm Intelligence (SI) techniques and their variants have been proposed, including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Differential Evolution (DE) and others. While they cannot guarantee always finding the global optimum, they provide efficient approximate optimal solutions in scenarios where exact solutions are difficult to obtain [

1,

2,

3].

The RF (Radio Frequency) accelerating structures are crucial components in particle accelerators used to accelerate charged particles to high energies. When RF power is applied, they generate RF electromagnetic field. The optimization challenge inherent to RF accelerating structures entails seeking the optimal solution within a high-dimensional parameter space, given the involvement of numerous geometric parameters, material properties, and other factors. Such optimization problems frequently demonstrate pronounced nonlinearity and multimodality, implying the presence of numerous local optimal solutions. Traditional optimization algorithms frequently encounter difficulties in effectively addressing this complexity. In practice, the optimization of RF accelerating structures typically involves a blend of theoretical analysis and practical experimentation. This involves the repetitive tuning of specific parameters while maintaining others constant. However, structures derived through this approach often represent local optima rather than global optima, despite their satisfactory performance. Moreover, this methodology demands a considerable investment of time and effort from researchers. To enhance optimization efficiency, various swarm intelligence (SI) algorithms have been applied to both single-objective (SOO) and multi-objective optimization (MOO) designs of RF accelerating structures, achieving promising results [

4,

5,

6,

7].

This paper uses the normal-conducting Dielectric Assist Accelerating (DAA) structure as a case study and proposes an improved single-objective optimization strategy based on a progressive exploration method to address the challenges of RF accelerating structures optimization. Among the various algorithms, it can address the issue of premature convergence to local optima caused by a large number of infeasible solutions in the solution space due to multiple stringent constraints, and it achieves rapidly progressive exploration of the solution space from a known feasible solution.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the optimization objectives and constraints involved in the design of RF acceleration structures. It also discusses the reasons for adopting the single-objective optimization algorithm for DAA structure along with the challenges that lurk in this approach.

Section 3 introduces the progressive exploration strategy with the penalty factor to increase the number of feasible solutions. In

Section 4, we analyze the experimental results and the performance of the algorithm. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this work.

2. Optimization of RF Accelerating Structure

2.1. Objectives

In the optimization design of RF accelerating structures, several crucial objectives must be meticulously tuned.

One of the objectives is the shunt impedance, which is given by the following formula:

where

is the accelerating voltage, and

is the power loss. The shunt impedance reflects the efficiency that the power supply transfer energy to the charged particles. Maximizing the shunt impedance can achieve the maximum acceleration of particles for a given available power.

The accelerating voltage is defined as the follows:

where

is the electric field component in the longitudinal direction,

is the angular frequency of the electromagnetic wave,

is the speed of particle and L is the length of the accelerating gap. The power loss

is the result of Ohmic heating, arising from the interaction between the tangential magnetic field and the surface resistance of the metallic walls. It defined as the follows:

Where, represents the surface resistance and represents the tangential component of the magnetic field strength.

Another objective is the quality factor Q_0 which defined as the ratio of the energy stored in the structure to the energy dissipated per radian. It is given by the follows:

where

the resonant frequency and

the stored energy. Maximizing cavity Q means minimizing the power required from the power supply to maintain the same stored energy.

The third crucial optimization objective is R/Q, which is given by the follows:

Higher R/Q ratio reflects the higher efficiency of energy transfer to the charged particles from the stored energy in the RF accelerating structure.

Ideally, achieving the three primary optimization objectives of RF accelerating structures (shunt impedance , quality factor and ) simultaneously would be desirable. However, this is typically infeasible, as the optimization of one objective often compromises another. In practical engineering applications, it is more pragmatic to focus on optimizing a single objective, contingent upon the other two meeting the necessary requirements, tailored to the specific application scenario and cavity type. Due to the extremely low surface impedance in the superconducting state, the power loss of the metal wall is no longer the performance bottleneck of the accelerating structure. Typically, the aim is to maximize the quality factor , while ensuring the peak electric field on the surface remains below a predefined threshold to avert instances of field emission and breakdown. Conversely, in normal conducting accelerating structures, characterized by relatively high surface resistance leading to noticeable energy dissipation, the predominant optimization objective is to maximize the shunt impedance. This type of optimization seeks to enhance the efficiency of energy transfer per unit consumption and achieve the highest possible acceleration gradient. In normal conducting accelerating structures, the peak surface electric field is typically not a focal point, as it always meets the design specifications in almost any situation. Finally, for certain small-scale accelerators like medical radiation therapy devices, there is often a focus on maximizing R/Q. This optimization leads to more efficient energy transfer from the accelerating structure to charged particles, thereby enhancing the cost-effectiveness of the system.

2.2. Constraints

In the optimization of RF accelerating structures, some constraints must be meticulously considered. These constraints confine the solution space within specific boundaries and significantly impact the final design.

Ideally, the operating mode frequency of an RF cavity must exactly match the design frequency. This alignment is fundamental because the cavity's interaction with charged particles relies on the intended frequency. However, achieving perfect coincidence between them is challenging in practical applications due to potential errors in design, manufacturing, and environmental variations such as temperature. Typically, frequency adjustments are made using mechanical methods, but the range of adjustment is often limited. Therefore, during the design phase, it's essential to constrain the frequency within a specific range around the ideal design frequency.

Several other important RF properties must be considered, such as the peak electric field on the surface and the frequency of higher-order modes (HOM). Exceeding certain thresholds of the peak electric field on the surface can lead to undesirable effects such as field emission and breakdown. For RF accelerating structures operating in the fundamental mode, maintaining a sufficient frequency separation between HOM and the fundamental mode is crucial to ensure that HOM can be effectively suppressed using HOM dampers, minimizing the impact of non-operational modes on the beam. This constraint is also significant for structures operating in non-fundamental modes, where the influence of neighboring modes must be carefully managed.

In addition to considering radio frequency characteristics, we must address mechanical constraints. The dimensions of RF accelerating structures and internal components are influenced by factors like available space within accelerator facilities and beam aperture design specifications. Moreover, it's crucial to anticipate increased detuning from Lorentz forces, especially when optimizing RF structures for pulsed beams, because these optimization processes may inadvertently compromise mechanical integrity. This implies that the geometric parameters cannot be arbitrarily optimized for the best RF performance. Furthermore, due to manufacturing tolerances, pursuing excessively precise solutions is impractical. Therefore, it's essential to establish limits on achievable precision.

2.3. Optimizing DAA Accelerating Structure

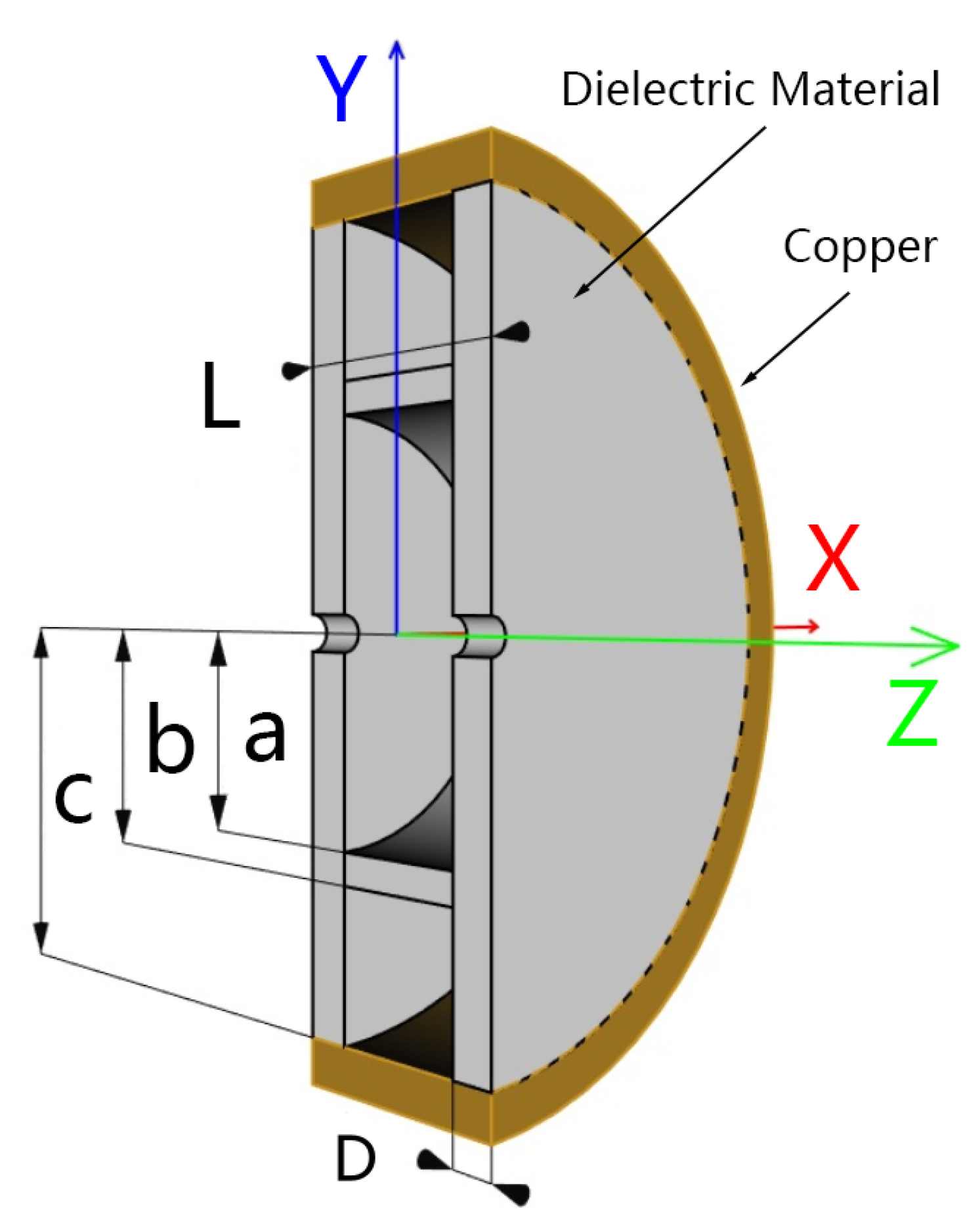

DAA accelerating structure is a novel normal conducting dielectric loaded RF accelerating structure. It’s a TM

020 mode standing wave accelerating structure with ultralow-loss dielectric material for electromagnetic field distribution control. The longitudinal cross-section of the DAA acceleration cell, depicted in

Figure 1, features a constant length, denoted as L, equivalent to half the wavelength. In the design of DAA accelerating structures, the primary objective is typically to maximize the shunt impedance while ensuring that R/Q remains above a specified threshold. Consequently, R/Q can be also treated as a constraint, defining the optimization of the DAA accelerating structure as a single-objective problem with multiple constraints [

8,

9]. Furthermore, another ancillary objective that is the frequency separation between the operating mode and adjacent modes has been overlooked. This objective is chiefly governed by the aperture radius, exhibiting minimal susceptibility to alterations in other geometric parameters. And the aperture radius determined by accelerator physics design maintains a constant value throughout the optimization process.

Therefore, when the material properties are identical, the geometric variables a, b, c, and D define the configuration of the DAA acceleration cell and have a significant impact on its performance.

The PSO, DE and the GA algorithm are the most popular swarm intelligence algorithms. For the RF accelerating structure optimization problem, the distribution of feasible solutions is continuous within the constraint range. Due to the inherent continuity of the PSO and DE algorithm, they are very suitable for solving this type of optimization problem, as particles move continuously according to certain laws. While many studies have reported successful applications of the GA algorithm in such optimization problems, the GA algorithm explores the solution space discretely rather than continuously [

10,

11,

12,

13].

The progressive exploration strategy was applied respectively to three improved single-objective swarm intelligence algorithms: PSO, DE, and GA, for the optimization of the DAA accelerating structure.

3. Progressive Exploration Strategy for Optimization Algorithm

Swarm intelligence algorithms guide stochastic exploration of the solution space by maintaining a population to find the global optimum with the maximum or minimum fitness value. Despite variations among specific algorithms (e.g., PSO, GA, DE), their general procedure can be summarized as follows:

Generate an initial population of agents (Swarm) and assign random vectors in solution space, where each agent represents a candidate solution.

Compute the fitness (objective value) of each agent, and record the best solution.

Update the population according algorithm rules.

Repeat step 2 until a converged optimal solution is obtained or a predefined number of iterations is reached.

3.1. Fitness Function for DAA Structure Optimization

The solution vector of the DAA structure is defined as

, where a, b, c, D represent the geometric parameters as illustrated in

Figure 1, and the

denotes the wavelength. Taking into account some mechanical and physical design limitations, the entire solution space should be limited to a certain size. Based on these variable parameters and other constants, the model is established using commercial electromagnetic numerical simulation software. Its performance is evaluated, including mode frequency, shunt impedance, quality factor, and R/Q.

The DAA structure optimization problem is a maximization problem with constraints aimed at maximizing the shunt impedance. Its fitness function is depicted as the follows:

Because the values of the shunt impedances are much greater than 0, it is reasonable to set the fitness value of infeasible solution to 0. All solutions with R/Q lower than the design value are treated as infeasible solutions. Additionally, imposing constraints on R/Q allows for the elimination of non-TM020 modes. The is the ideal design operation frequency and the is the frequency range that can be tuned. From a practical engineering perspective, if the calculated frequency exceeds the tunable range, the solution should be classified as an infeasible solution. However, this would result in a sharp decrease in the number of feasible solutions, thus causing the PSO algorithm to fail to function properly. Therefore, the penalty factor is introduced to penalize the fitness value by adding a term proportional to the degree of frequency constraint violation, where . is a virtual function, and the , and frequency f are all calculated through numerical simulation software.

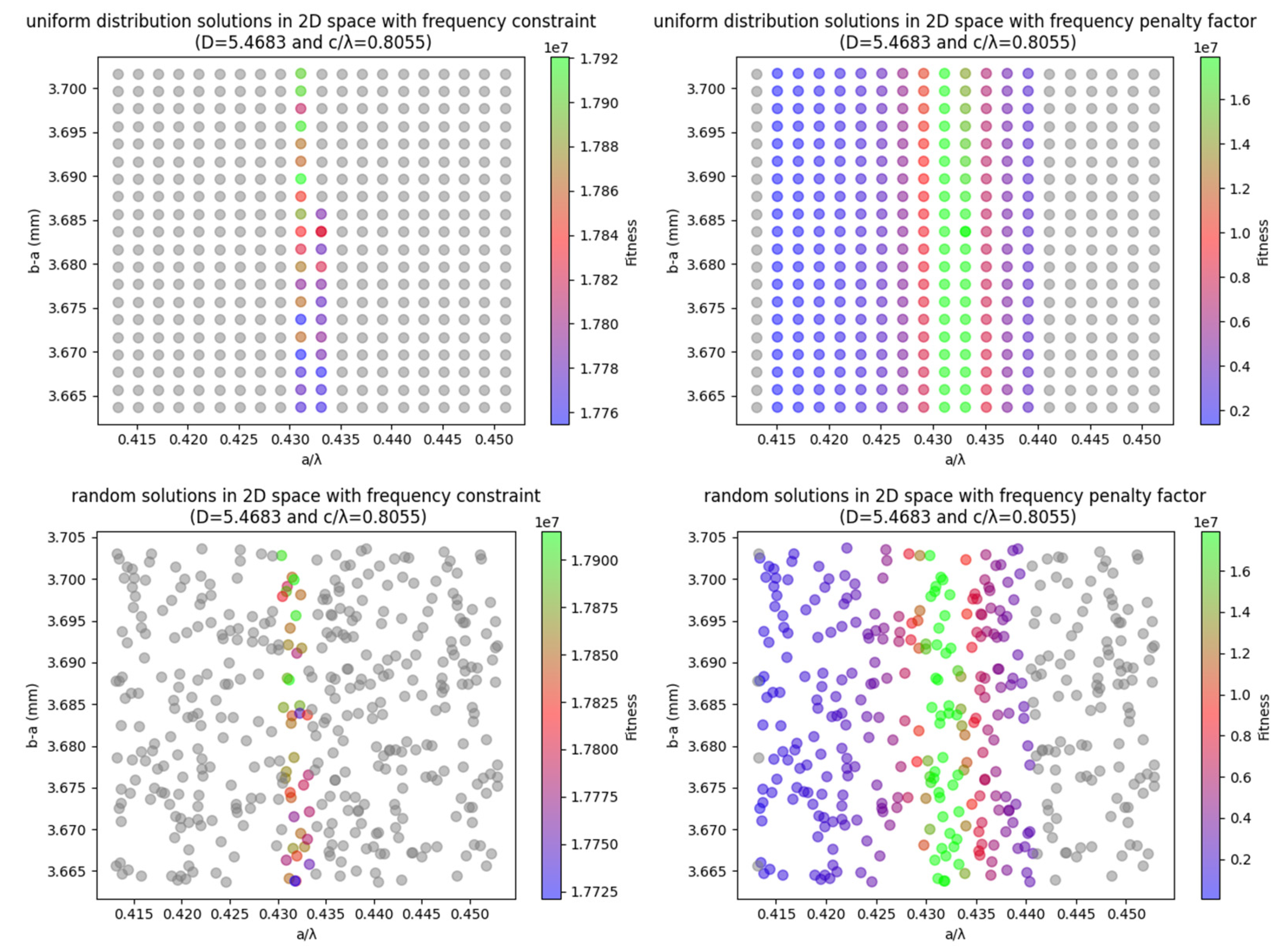

Figure 2 shows the distribution of solutions in a two-dimensional solution space near an initial feasible solution

, while keeping D and

constant. The colored points represent feasible solutions, while the gray points represent infeasible ones. As shown in the figure, replacing the frequency constraint with a penalty factor significantly increases the number of feasible solutions.

3.2. Progressive Exploration Stratege

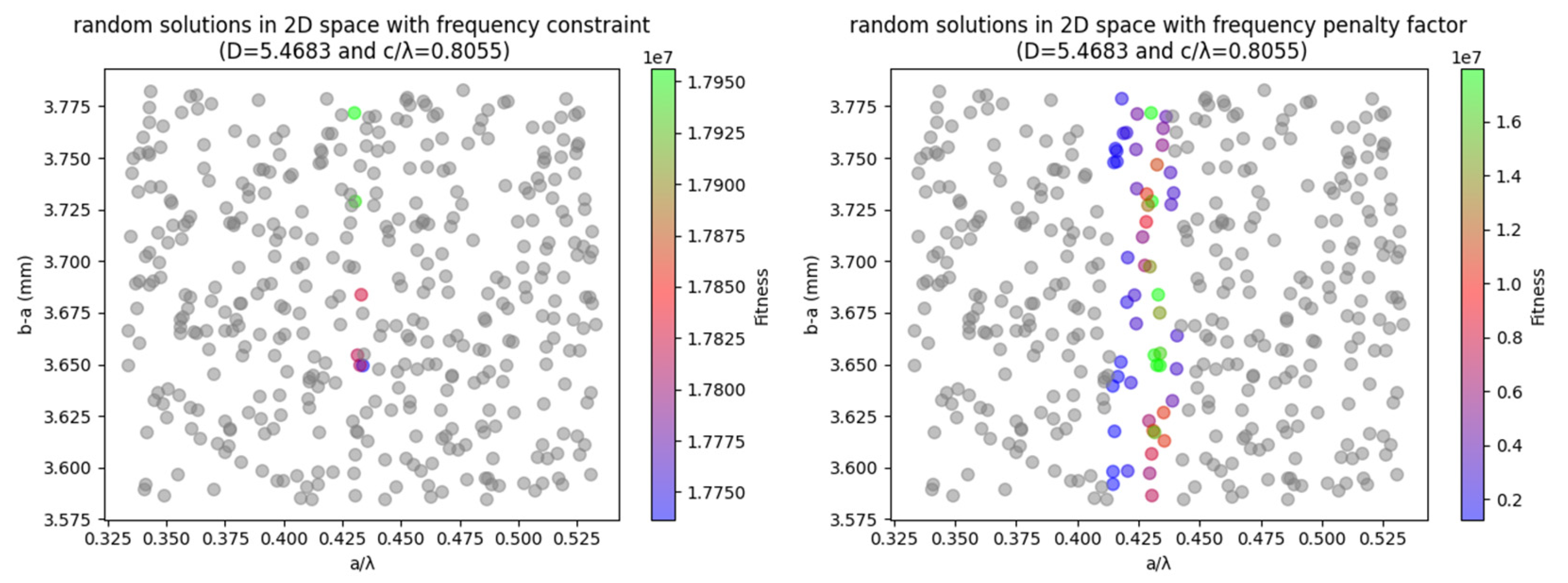

The depicted solution space in

Figure 2 represents a minute fraction of the expansive realm requiring exploration, accounting for approximately 7.4074E-9% of the total solution space. The continuous distribution of feasible solutions is observed, which is consistent with electromagnetic field theory. Consequently, as the explored space expands, the proportion of feasible solutions diminishes.

Figure 3 depicts the distribution of random feasible solutions near the same initial feasible solution, spanning a much larger range, approximately 25 times the solution space illustrated in

Figure 2. Therefore, applying the single-objective optimization algorithm directly to search for the optimal solution across the entire solution space may lead to operational challenges due to the scarcity of feasible solutions, even with the incorporation of a frequency penalty factor.

Based on the characteristics of the feasible solution distribution in the DAA structure optimization problem, and inspired by exploration strategies employed in some improved algorithms, this paper introduces a new progressive exploration strategy for single-objective swarm intelligence optimization algorithm [

14,

15,

16,

17]. This strategy commences its exploration from the vicinity of a feasible solution and gradually moves or expands its search scope, guided by the swarm global best solution and the convergence criteria, until the entirety of the solution space is thoroughly explored. The process of progressive exploration strategy is shown in

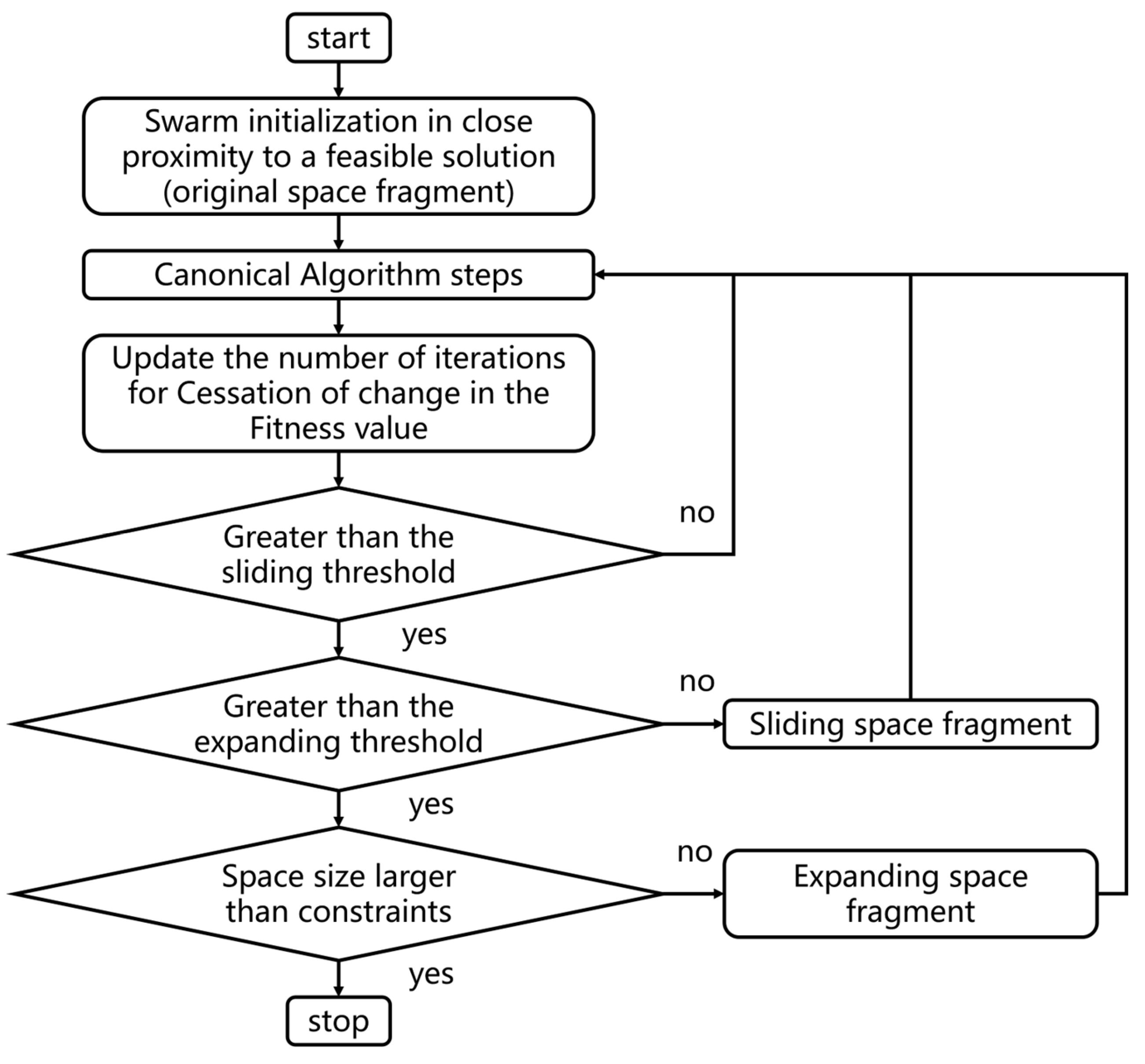

Figure 4.

Firstly, the swarm is initialized in close proximity to a feasible solution within a narrow range called space fragment. To augment the quantity of feasible solution particles, we employ a normal random distribution of particles. The convergence criterion is defined by the cessation of change in the fitness value. Upon sustaining convergence for a predetermined number of iterations, the algorithm is deemed to have discovered a local optimum within the original solution space fragment. Subsequently, the previous solution space fragment is shifted to center around this newfound local optimum, and the entire swarm is reinitialized within it, followed by the execution of the swarm intelligence algorithm once more. We refer to this process as the sliding of space fragments. If the local optimum remains unchanged following the sliding of the space fragment, its scope is expanded. Subsequently, the swarm undergoes reinitialization, followed by the repeated execution of the PSO algorithm. This process is referred to as the expansion of the space fragment. The algorithm will repeat the sliding and expanding process of the space fragment until the entire solution space is explored. At every sliding or expanding process, the global best solution particle from the previous swarm is incorporated into the reinitialized swarm as a guarantee mechanism. This ensures that subsequent iterations can find better solutions.

Figure 5 illustrates the sliding and expansion of the solution space fragment in PSO, DE and GA algorithms. The red rectangle denotes the original solution space fragment, while rectangles of varying colors depict solution space fragments re-initialized at different stages. The black lines and arrows delineate the trajectory of the sliding solution space fragments. From this visual representation, we also observed that the centers of certain sliding space fragments are not within the space fragments before sliding. This behavior arises from the inherent properties of the PSO and DE algorithms, where particle movements and vector updates are not constrained by the initial spatial limits. Such flexibility significantly accelerates convergence compared to GA and other algorithms based on binary encoding. Additionally, occasional overlaps between space fragments are observed, typically occurring when the swarm becomes trapped in a local suboptimal solution. In such scenarios, re-initialization plays a crucial role in restoring diversity within the swarm, enabling it to escape local suboptimalities and prevent premature convergence. This technique is well-established in many improved algorithms maintaining optimization performance.

4. Result and Analysis

With the progressive exploration strategy the swarm intelligence algorithm can explore the entire solution space along the path of feasible solutions rapidly. In the actual algorithm implementation, the swarm is configured to consist of 50 particles, with a maximum of 100 iterations. The distribution of particles during the iteration process is illustrated in

Figure 6, while the distribution of feasible solutions is depicted in

Figure 7. The particle named 'org_x' is the original feasible solution which our exploration start from, and the particle named 'best_x' is the global optimal solution found by the enhanced swarm intelligence algorithm. From these two figures, it can be seen that as the number of iterations increases, the particles gradually disperse throughout the solution space that needs to be explored. Most of the particles gather around the path formed by the feasible solutions and move along this path towards the global optimal solution.

Figure 8 delineates the convergence trajectory of the enhanced swarm intelligence algorithms. The DE algorithm demonstrates superior optimization performance in convergence speed. It rapidly reaches near-optimal fitness within the first few iterations and maintains stability thereafter, indicating strong global search capability and efficient exploitation. The PSO algorithm achieves a competitive final fitness but requires more iterations to converge, suggesting a slower optimization process. In contrast, the GA algorithm exhibits the slowest convergence and lowest fitness improvement, The final converged fitness value achieved by the PSO algorithm amounts to 19,442,656.00, slightly surpassing the DE and GA algorithm's attainments (19430028.00 and 19,441,840.00). Furthermore, the visual representation reveals that the integration of the progressive exploration strategy with both the PSO, DE and GA algorithms effectively enables evasion from the traps of local optimal solutions.

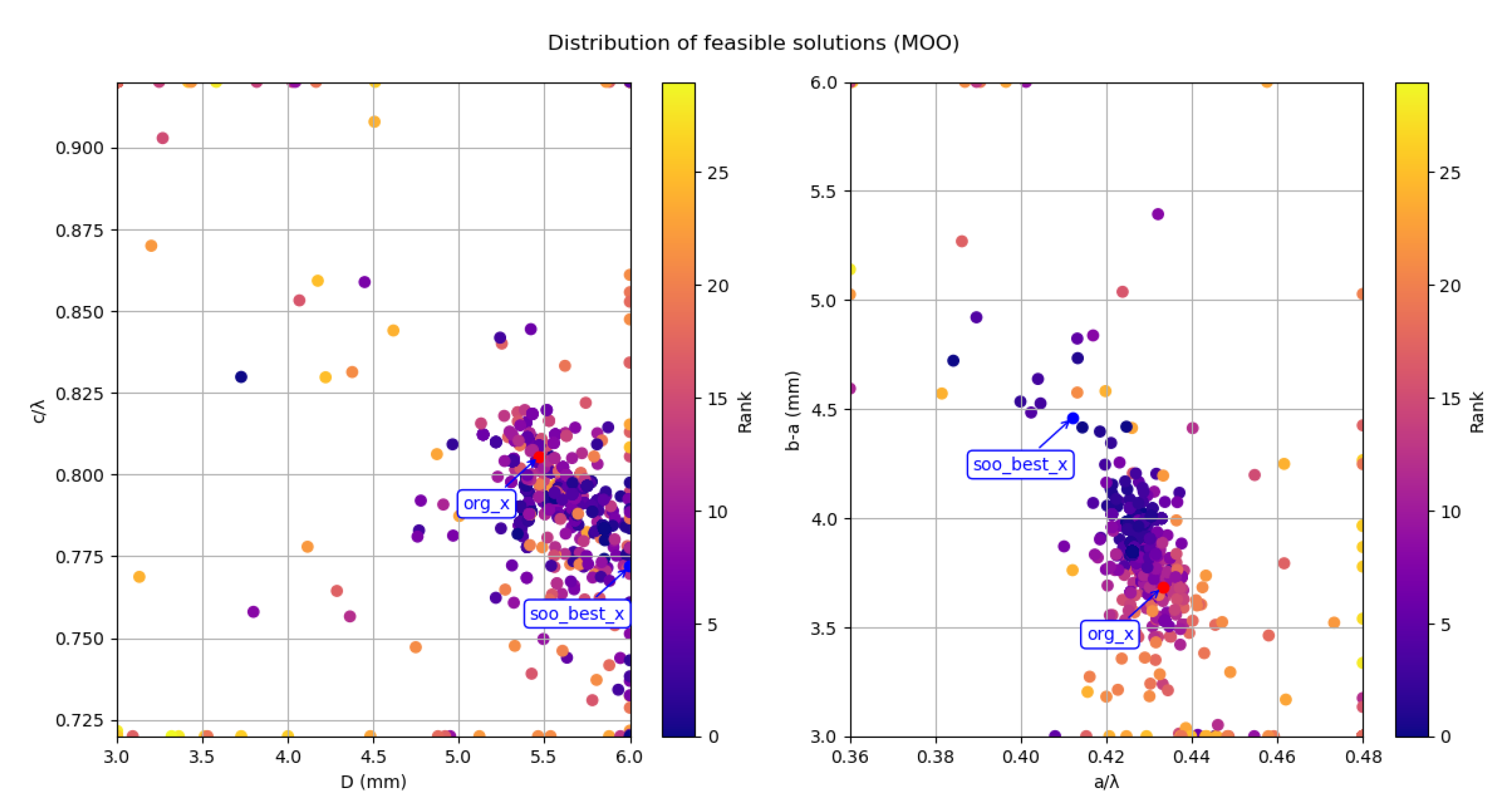

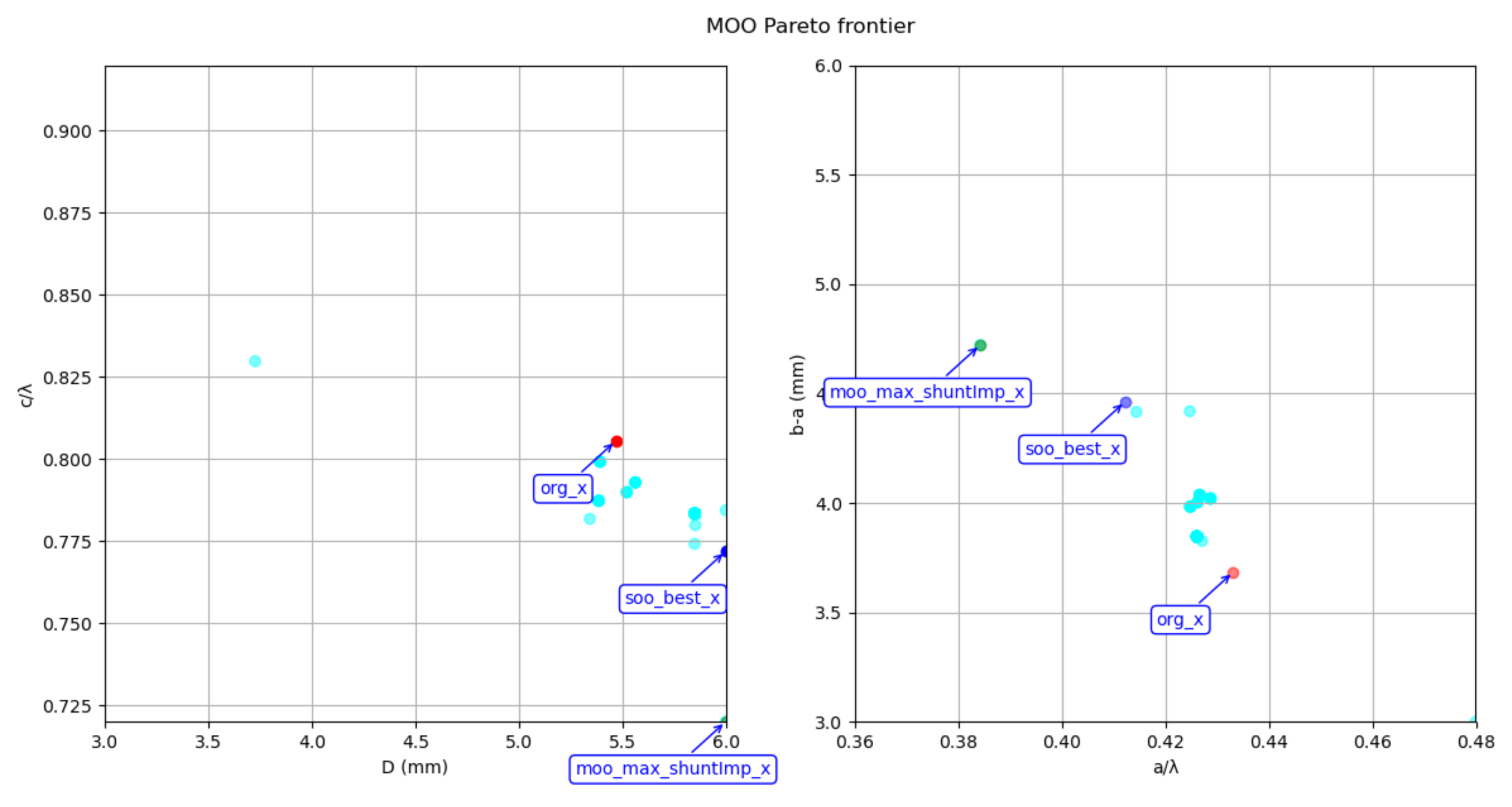

We also applied the Progressive Exploration Strategy to the multi-objective algorithm and optimized the DAA accelerating structure. The distribution of solutions and the resulting Pareto front, in comparison to the optimal solution obtained via the single-objective approach, are illustrated in the solution space in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 respectively.

The SOO optimal solution is close to the MOO Pareto front, but it is not one of the solutions contained within the Pareto front. The feasible solution with the highest shunt impedance found by the MOO algorithm has a shunt impedance of 18377959.0 ohms, and it belongs to the Pareto front. The resonant frequency of the accelerating structure optimized by the MOO approach is closer to 5.71 GHz. However, its shunt impedance and quality factor (170,522.76) are both lower than those of the structure optimized by the SOO algorithm (19,442,656.00 ohms and 171484.6877). Therefore, from the perspective of engineering applications, the SOO-optimized result is clearly the more appropriate choice.

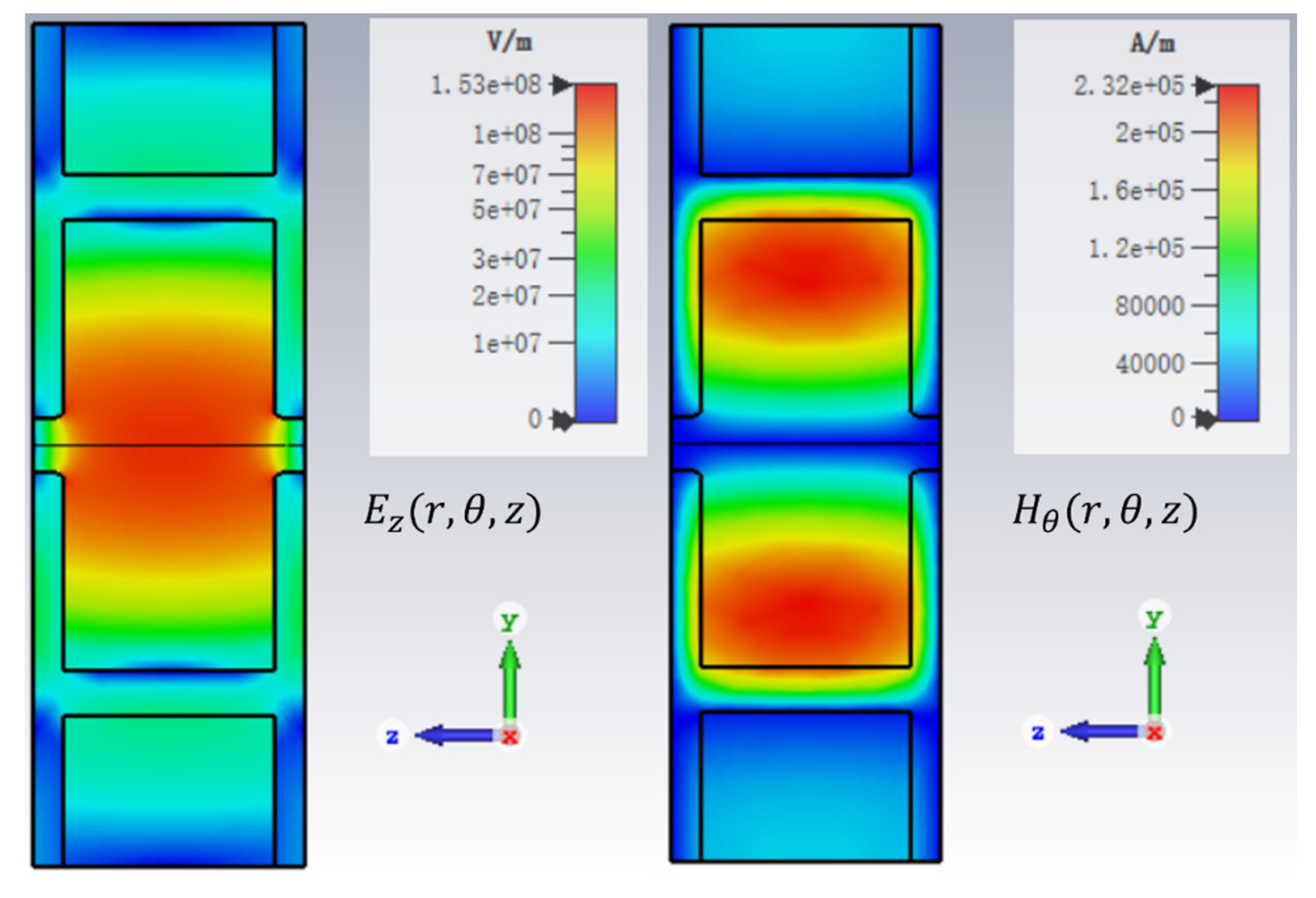

The global optimal solution obtained after the convergence of the optimization algorithm is

. The electric field distribution

and the magnetic field distribution

of the TM020 mode in the optimized DAA accelerating structure are shown in

Figure 11. These contour plots are the results of eigenmode simulation with CST Microwave studio. The RF parameters of the operating mode in the optimized DAA accelerating structure are shown in the

Table 1. In

Table 1,

represents the effective shunt impedance with the transit time factor taken into account. When the influence of the transit time factor is removed, the shunt impedance per accelerating distance

= 1297.71705 MΩ/m. Compared to the shunt impedance per unit length

=797 MΩ/s and Q

0=136000 given for a single cell of the DAA accelerating structure in reference 8, the optimized structure has much higher shunt impedance

and quality factor Q

0.

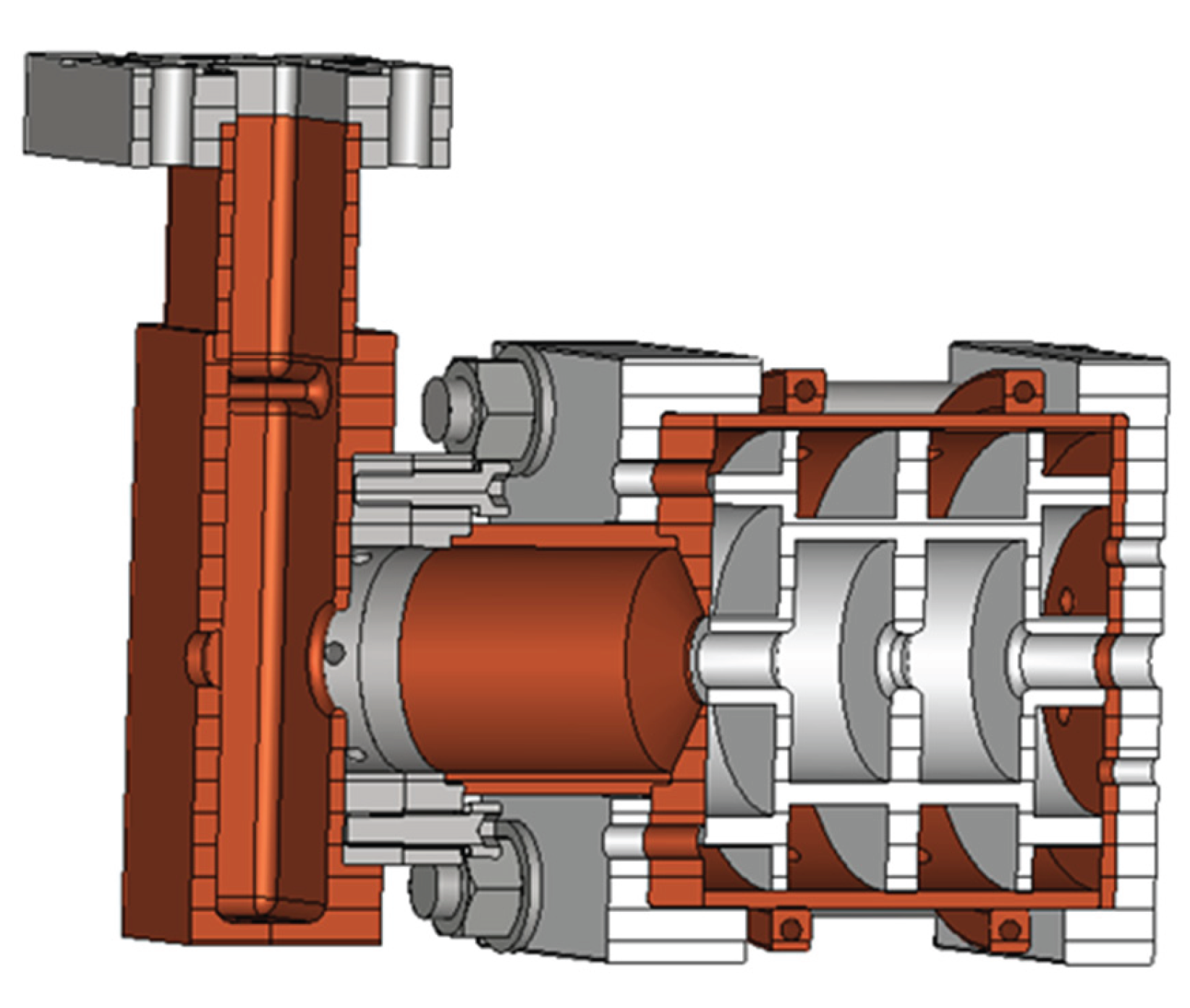

Based on the optimized results of the accelerating structure, we designed and fabricated a 2-cell cavity comprising two accelerating cells and two end cells for cold testing, see the

Figure 12. Since it is difficult and expensive to fabricate a cavity using a dielectric material as high-performance as the TiO₂-doped alumina mentioned in the references, alumina ceramic with a relative permittivity of 10 and a loss tangent of 2×10

-5 was used for the cavity design and manufacture instead. The final simulation results of the complete cavity are: R

sh=15.37 MΩ, f =5.71203 GHz,Q

0 = 73185;R/Q = 210. Due to manufacturing errors, the actual performance of the cavity is inevitably lower than the simulation results. The measured results, which all exceed 90% of the simulated values, are: R

sh=14.14 MΩ, f =5.71203 GHz,Q

0 = 67330, R/Q = 210.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we analyze the characteristics of the optimization problem in RF accelerator structures and propose an enhanced PSO algorithm based on a progressive exploration strategy, considering the continuous distribution of feasible solutions within its solution space. For this type of optimization problem, algorithms based on continuous exploration mechanisms, such as PSO, have an advantage in exploration efficiency compared to algorithms based on discrete exploration mechanisms, such as GA. The enhanced PSO algorithm is applied to optimize the multi-constrained single-objective optimization problem of the DAA single-cell accelerating structure. By introducing a frequency penalty factor in place of frequency constraint conditions, the algorithm mitigates the issue of an insufficient quantity of feasible solutions.

The progressive exploration strategy enables the swarm to slide and expand along a reasonable path within the feasible solution region, thereby accelerating the exploration of the required solution space. During each phase of sliding and expansion, a re-initialization mechanism is introduced to restore swarm diversity, which significantly enhances the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima traps.

The progressive exploration strategy has been applied to various single-objective swarm intelligence algorithms and tested on the optimization of the DAA accelerating structure, all achieving satisfactory results. The strategy demonstrates fast convergence and strong capability in avoiding local optima.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Wei Long, Junyu Zhu and Xiao Li; methodology, Wei Long, Bin Wu, Xuerui Hao and Jian Wu; software, Wei Long and Xuerui Hao; validation, Wei Long, Junyu Zhu and Xiao Li; formal analysis, Wei Long; investigation, Wei Long, Xuerui Hao; resources, Wei Long, Shenghua Liu, Yang Liu, Chunlin Zhang, Shengyi Chen, Xiang Li and Junyu Zhu; data curation, Wei Long; writing—original draft preparation, Wei Long; writing—review and editing, Wei Long, Jun yu Zhu and Xiao Li; visualization, Wei Long; supervision, Xiao Li; project administration, Junyu Zhu and Xiao Li; funding acquisition, Junyu Zhu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 12205168.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my colleagues in the research group for their support in my work, especially Zhu Junyu and Hao Xuerui for their assistance with RF accelerating structure theory and simulation techniques.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SI |

Swarm Intelligence |

| SOO |

Single-Objective Optimization |

| MOO |

multi-objective optimization |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithms |

| PSO |

Particle Swarm Optimization |

| ACO |

Ant Colony Optimization |

| DE |

Differential Evolution |

| RF |

Radio Frequency |

| DAA |

Dielectric Assist Accelerating |

| HOM |

Higher-Order Modes |

References

- Tang J, Liu G, Pan Q. A review on representative swarm intelligence algorithms for solving optimization problems: Applications and trends[J]. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2021, 8, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan D, Cheng R. Competitive Swarm Optimizer: A decade survey[J]. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2024, 87, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Mo Y, Lu Y, et al. Swarm-intelligence optimization method for dynamic optimization problem[J]. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang Z, Pei Y, Pang J. Optimal design of a standing-wave accelerating tube with a high shunt impedance based on a genetic algorithm[J]. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2015, 790, 19–27.

- Smith S, Southerby M, Setiniyaz S, et al. Multiobjective optimization and Pareto front visualization techniques applied to normal conducting rf accelerating structures[J]. Physical Review Accelerators and Beams 2022, 25, 062002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Ye K, Hao X, et al. Combining multi-objective genetic algorithm and neural network dynamically for the complex optimization problems in physics[J]. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 880. [Google Scholar]

- Kranjčević M, Adelmann A, Arbenz P, et al. Multi-objective shape optimization of radio frequency cavities using an evolutionary algorithm[J]. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2019, 920, 106–114.

- Satoh D, Yoshida M, Hayashizaki N. Dielectric assist accelerating structure[J]. Physical Review Accelerators and Beams 2016, 19, 011302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh D, Yoshida M, Hayashizaki N. Fabrication and cold test of dielectric assist accelerating structure[J]. Physical Review Accelerators and Beams 2017, 20, 091302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan R, Cohanim B, De Weck O, et al. A comparison of particle swarm optimization and the genetic algorithm[C]//46th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC structures, structural dynamics and materials conference. 2005: 1897.

- El-Ghandour H A, Elbeltagi E. Comparison of five evolutionary algorithms for optimization of water distribution networks[J]. Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering 2018, 32, 04017066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng H Q, Luo T, Li D, et al. Optimization of RF Cavities Using MOGA for ALS-U[C]//10th Int. Particle Accelerator Conf.(IPAC'19), Melbourne, Australia, 19-24 May 2019. JACOW Publishing, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019: 3007-3010.

- Kim D S, Han I T, Kim W S, et al. Optimization of Wide-Band and Wide Angle Cavity-Backed Microstrip Patch Array Using Genetic Algorithm[J]. Progress In Electromagnetics Research M 2020, 90, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein E H, Gad A G, Hussain K, et al. Major advances in particle swarm optimization: theory, analysis, and application[J]. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2021, 63, 100868.

- Gad A, G. Particle swarm optimization algorithm and its applications: a systematic review[J]. Archives of computational methods in engineering 2022, 29, 2531–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltamaly A M, MH Farh H, S. Al Saud M. Impact of PSO reinitialization on the accuracy of dynamic global maximum power detection of variant partially shaded PV systems[J]. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriy R, Viatcheslav L. A novel multi-epoch particle swarm optimization technique[J]. Cybernetics and Information Technologies 2018, 18, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi N I H, Musa Z. A New Approach of Midrange Exploration Exploitation Searching Particle Swarm Optimization for Optimal Solution[C]//2023 IEEE 8th International Conference On Software Engineering and Computer Systems (ICSECS). IEEE, 2023: 430-434.

- Pu X, Tan X. A novel PSO algorithm based on dual group of dispersing and clustering mechanism[J]. Journal of Computational Information Systems 2015, 11, 547–557. [Google Scholar]

- Lenin K, Reddy B R, Kalavathi M S. Progressive Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Solving Reactive Power Problem[J]. International Journal of Advances in Intelligent Informatics 2015, 1, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).