Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of F1 Population and Evaluation of SBS Resistance

2.2. Genotyping and Linkage Map Construction

2.3. QTL Mapping

2.4. Annotation and Screening of Candidate Genes

2.5. qRT-PCR Verification of Candidate Genes

3. Results

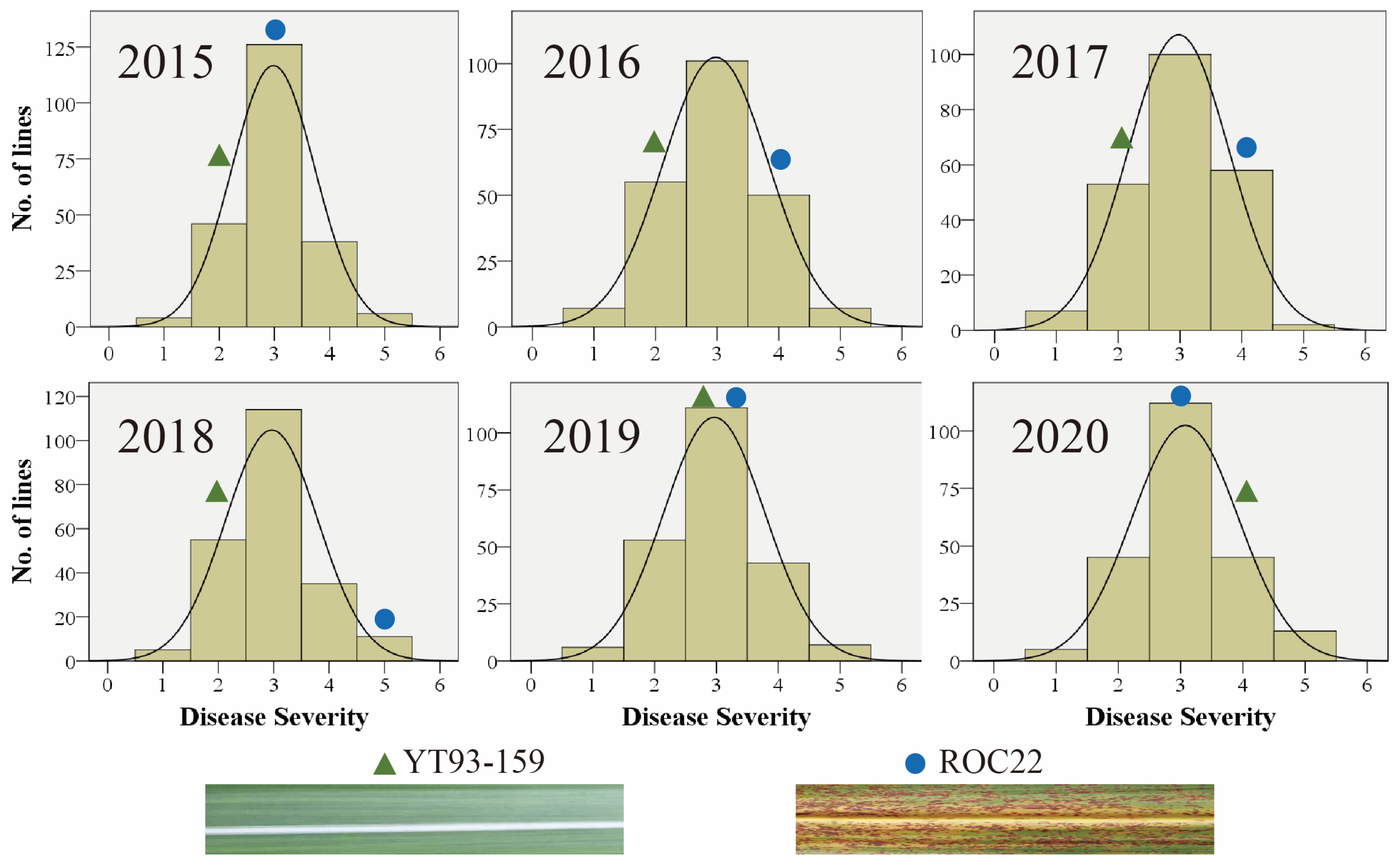

3.1. Phenotypic Data Analysis

3.2. Linkage Map Constructed from the F1 Mapping Population

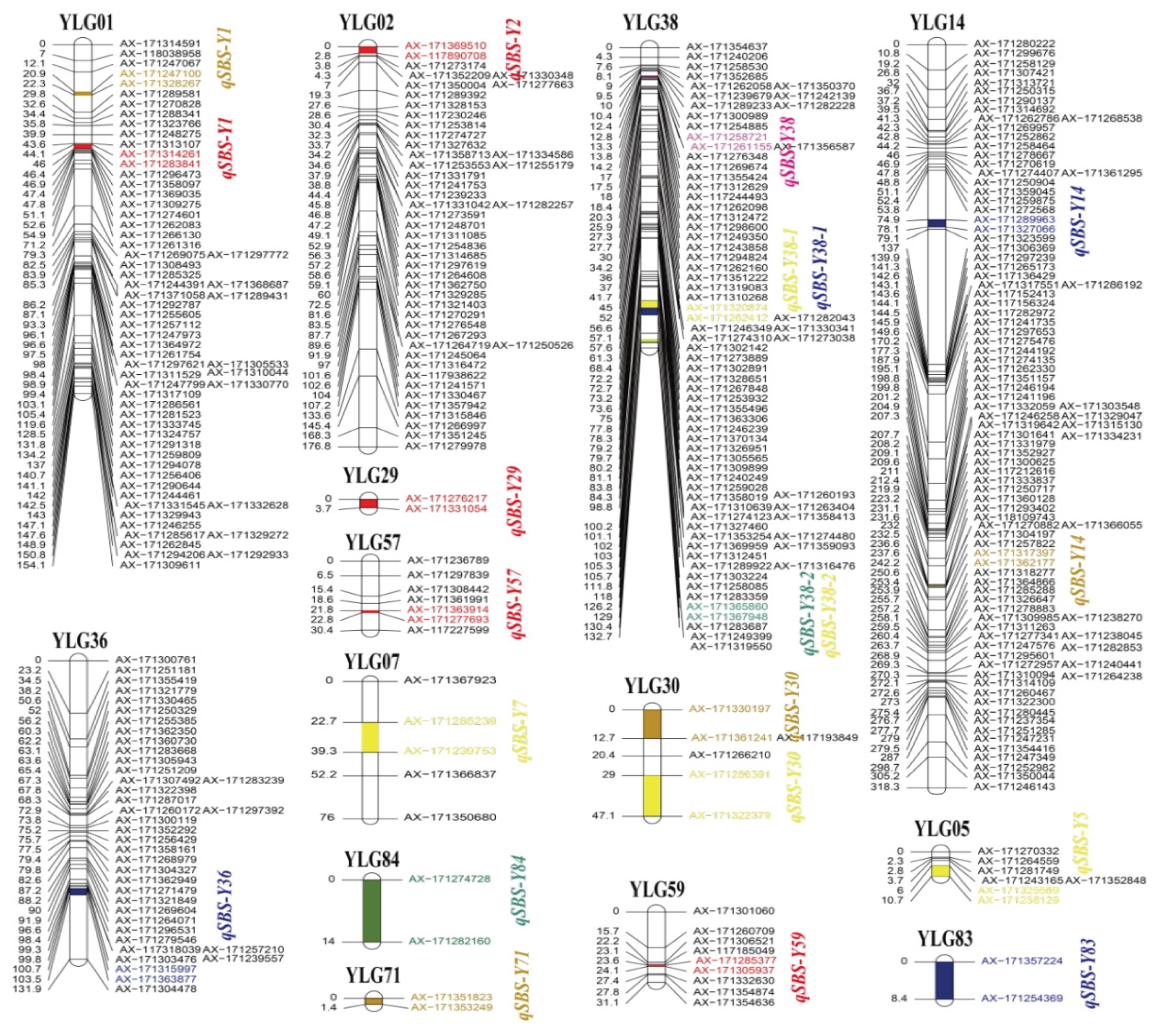

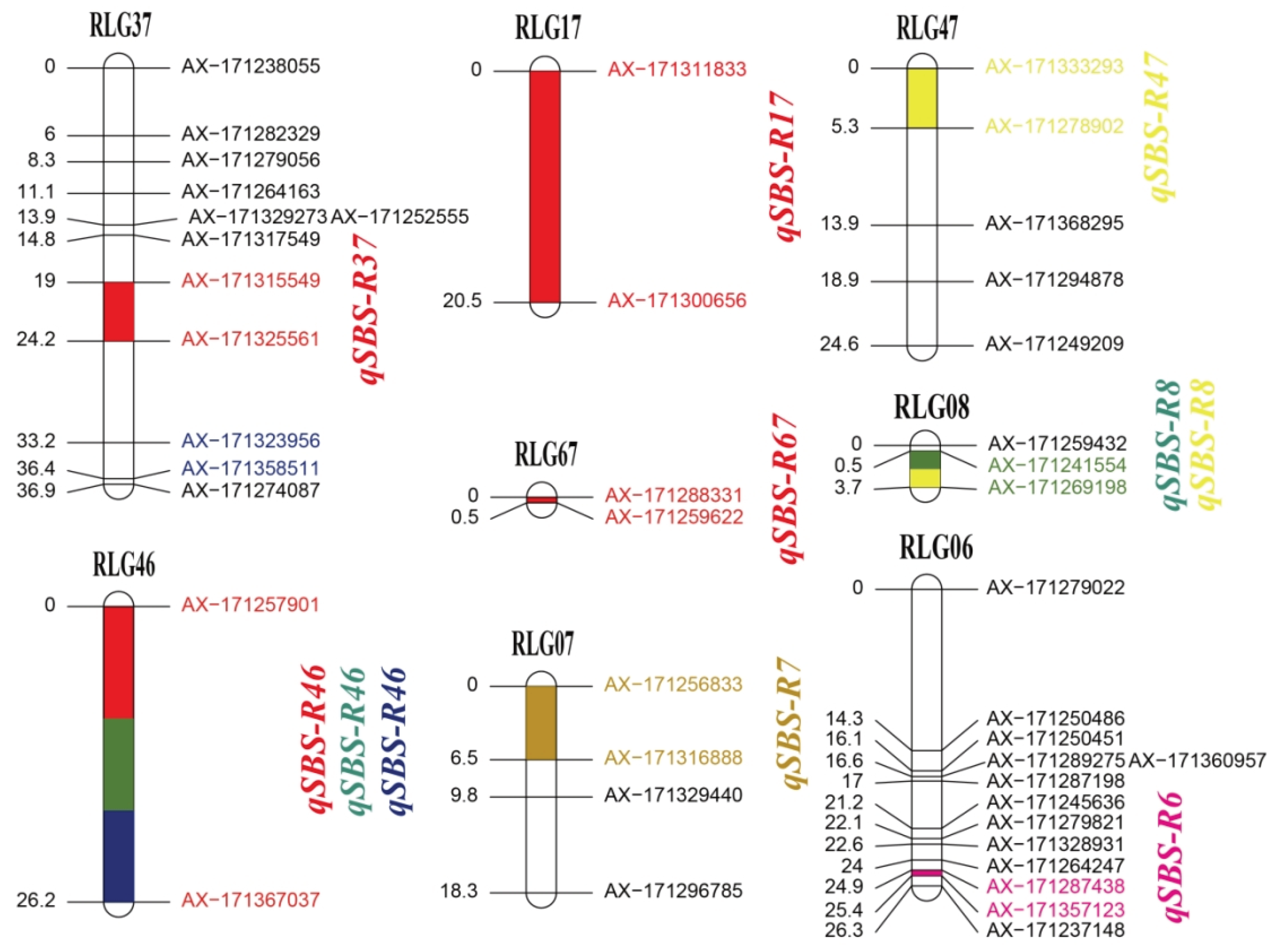

3.3. QTL Analysis of SBS Resistance

3.4. Screening of Critical Genes Associated with SBS Resistance

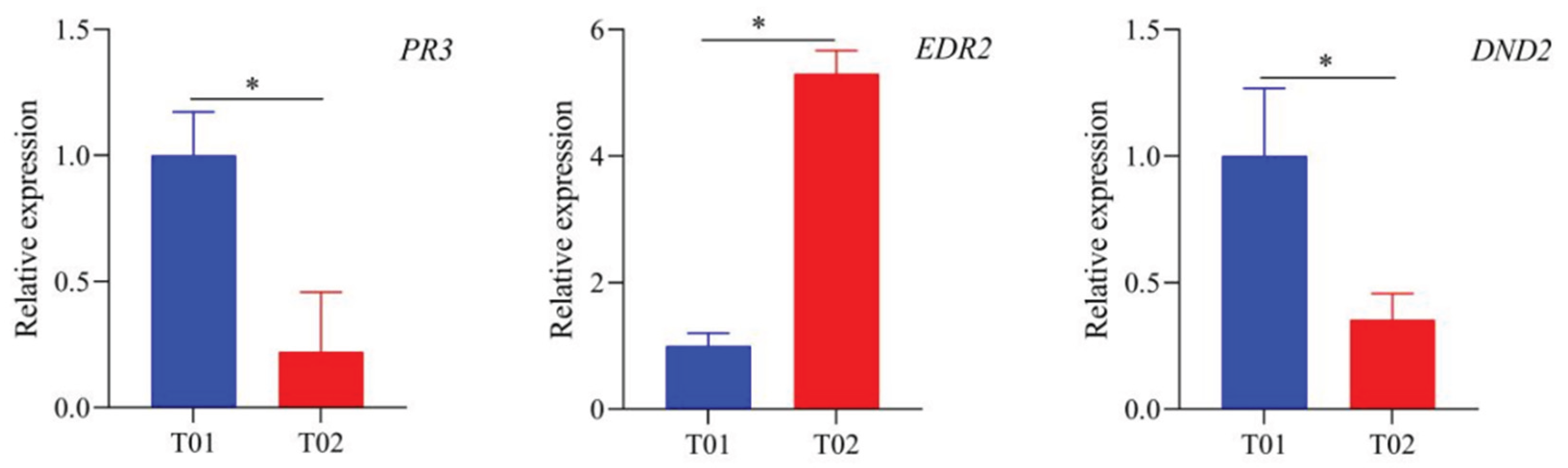

3.5. Expression Analysis of Critical Candidate Genes by qRT-PCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, S.Y.; Feng, X.X.; Zhang, Z.; Hua, X.T.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.J.; Li J.W.; Liu, X.J.; Weng, C.Y.; Chen, B.S.; Zhang, M.Q.; Yao, W.; Tang, H.B.; Ming, R, Zhang, J.S. ScDB: A comprehensive database dedicated to Saccharum, facilitating functional genomics and molecular biology studies in sugarcane. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 3386–3388. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Cang, X.Y.; Qin, W.;Shan, H.L.; Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, C.M.; Li, W.F.; Huang, Y.K. Evaluation of field resistance to brown stripe disease in novel and major cultivated sugarcane varieties in China. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 103, 985–989. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Wang, Z.T.; Xu, F.; Lu, G.L.; Su, Y.C.; Wu, Q.B.; Wang, T.; Que, Y.X.; Xu, L.P. Screening of candidate genes associated with brown stripe resistance in sugarcane via BSR-seq analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15500. [CrossRef]

- Nyvall, R.F. Field crop diseases handbook, 2nd ed.; Springer, Boston, MA, 1989; pp. 97–106.

- Parthasarathy, S.; Thiribhuvanamala, G.; Prabakar, K. Diseases of field crops and their management, 1st ed., CRC Press, London, 1988; pp. 344–351.

- Hoarau, J.Y.; Dumont, T.; Wei, X.M.; Jackson, P.; D’Hont, A. Applications of quantitative genetics and statistical analyses in sugarcane breeding. Sugar Tech. 2022, 24, 320–340. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Q.; Huang, Y.X.; Zhang, L.J.; Zhou, Z.F.; Zhou S, Duan, W.X.; Yang, C.F.; Gao, Y.J.; Li, S.C.; Chen, M.Y.; Li, Y.R.; Yang, X.P.; Zhang, G.M.; Huang D.L. Genome-wide association study unravels quantitative trait loci and genes associated with yield-related traits in sugarcane. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 16815–16826. [CrossRef]

- Awata, L.A.O.; Beyene, Y.; Gowda, M.; Suresh, L.M.; Jumbo, M.B.; Tongoona, P.; Danquah, E.; Ifie, B.E.; Marchelo-Dragga, P.W.; Olsen, M.; Ogugo, V.; Mugo, S.; Prasanna, B.M. Genetic analysis of QTL for resistance to Maize lethal necrosis in multiple mapping populations. Genes. 2019, 11, 32. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, N.; Khan, M.S.; Swapna, M.; Yadav, S.; Tiwari, G.J.; Jena, S.N.; Patel, J.D.; Manimekalai, R.; Kumar, S.; Dattamajuder, S.K.; Kapur, R.; Koebernick, J.C.; Singh, R.K. QTL mapping and identification of candidate genes linked to red rot resistance in sugarcane. 3 Biotech. 2023, 13, 82. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.J.; Zhou, S; Huang, Y.X.; Zhang, B.Q.; Xu, Y.H.; Zhang, G.M.; Lakshmanan P; Yang, R.Z.; Zhou, H.; Huang, D.L.; Liu, J.X.; Tan, H.W.; He, W.Z.; Yang, C.F.; Duan, W.X. Quantitative trait loci mapping and development of KASP marker smut screening assay using high-density genetic map and bulked segregant RNA sequencing in sugarcane (Saccharum spp.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 796189. [CrossRef]

- Le Cunff, L.; Garsmeur; O.; Raboin; L.M.; Pauquet, J.; Telismart, H.; Selvi, A.; Grivet, L.; Philippe, R.; Begum, D.; Deu, M.; Costet, L.; Wing, R.; Glaszmann, J.C.; D’Hont, A. Diploid/polyploid syntenic shuttle mapping and haplotype-specific chromosome walking toward a rust resistance gene (Bru1) in highly polyploid sugarcane (2n∼12x∼115). Genetics. 2008, 180, 649–660. [CrossRef]

- Wirojsirasak, W.; Songsri, P.; Jongrungklang, N.; Tangphatsornruang, S.; Klomsa-Ard, P.; Ukoskit, K. A large-scale candidate-gene association mapping for drought tolerance and agronomic traits in sugarcane. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12801. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.Z.; Chen, Y.L.; Pan, Y.B.; Shi A.N. A genome-wide association study and genomic prediction for fiber and sucrose contents in a mapping population of LCP 85-384 sugarcane. Plants. 2023, 12, 1041. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.L.; Wang, Z.T.; Pan, Y.B.; Wu, Q.B.; Cheng W; Xu F; Dai, S.B.; Li, B.Y.; Que, Y.X.; Xu, L.P. Identification of QTLs and critical genes related to sugarcane mosaic disease resistance. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1107314. [CrossRef]

- Aitken, K.S.; Jackson, P.A.; McIntyre, C.L. A combination of AFLP and SSR markers provides extensive map coverage and identification of homo(eo)logous linkage groups in a sugarcane cultivar. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 789–801. [CrossRef]

- Hearnden, P.R.; Eckermann, P.J.; McMichael, G.L.; Hayden, M.J.; Eglinton, J.K.; Chalmers, K.J. A genetic map of 1,000 SSR and DArT markers in a wide barley cross. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007, 115, 383–391. [CrossRef]

- Maughan, P.J.; Bonifacio, A.; Jellen, E.N.; Stevens, M.R.; Coleman, C.E.; Ricks, M.; Mason, S.L.; Jarvis, D.E.; Gardunia, B.W.; Fairbanks, D.J. A genetic linkage map of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) based on AFLP, RAPD, and SSR markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 1188–1195. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Kim, K.H.; Song, K.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, B.M. Identification and validation of candidate genes conferring resistance to downy mildew in maize (Zea mays L.). Genes. 2020, 11, 191. [CrossRef]

- Klie, M.; Menz, I.; Linde, M.; Debener, T. Strigolactone pathway genes and plant architecture: association analysis and QTL detection for horticultural traits in chrysanthemum. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2016, 291, 957–969. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gill, R.A.; Zaman, Q.U.; Ulhassan, Z.; Zhou W.J. Insights on SNP types, detection methods and their utilization in Brassica species: Recent progress and future perspectives. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 324, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.A.; Liu S.S.; Pei Y.H.; Jiang X.W.; Jaqueth, J.S.; Li B.L.; Han J, Jeffers D, Wang J.B.; Song X.Y. Identification of genetic loci associated with rough dwarf disease resistance in maize by integrating GWAS and linkage mapping. Plant Sci. 2022, 315, 111100. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Chen, Y.L.; Thomas, C.L.; Ding, G.D.; Xu, P.; Shi, D.X.; Grandke, F. Jin, K.M.; Cai, H.M.; Xu, F.S.; Yi, B.; Broadley, M.R.; Shi, L. Genetic variants associated with the root system architecture of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) under contrasting phosphate supply. DNA Res. 2017, 24, 407–417. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.W.; Dong, Z.D.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, F. The Wheat 660K SNP array demonstrates great potential for marker-assisted selection in polyploid wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020, 18, 1354–1360. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.L.; Pan, Y.B.; Wang, Z.T.; Xu, F.; Cheng, W.; Huang, X.G.; Ren, H.; Pang, C.; Que, Y.X.; Xu, L.P. Utilization of a sugarcane100K single nucleotide polymorphisms microarray-derived high-density genetic map in quantitative trait loci mapping and function role prediction of genes related to chlorophyll content in sugarcane. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 817875. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.P.; Islam, M.S.; Sood, S.; Maya, S.; Hanson, E.A.; Comstock, J.; Wang, J.P. Identifying quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and developing diagnostic markers linked to orange rust resistance in sugarcane (Saccharum spp.). Front Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 350. [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Sood, S.; Luo, Z.L.; Liu, H.B.; Islam, M.S.; Zhang, M.Q.; Wang, J.P. Identifying genomic regions controlling ratoon stunting disease resistance in sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) clonal F1 population. Crop J. 2021, 9, 1070–1078. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.T.; Lu, G.L.; Wu, Q.B.; Li, A.T.; Que, Y.X.; Xu L.P. Isolating QTL controlling sugarcane leaf blight resistance using a two-way pseudo-testcross strategy. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1131–1140. [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.R.; Appunu, C.; Arun Kumar, R.; Manimekalai, R.; Vasantha, S.; Krishnappa, G.; Kumar, R.; Pandey, S.K.; Hemaprabha, G. Recent advances in sugarcane genomics, physiology, and phenomics for superior agronomic traits. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 854936. [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Yang, X.P.; Peng, Z.; Islam, M.S.; Sood, S.; Luo, Z.L.; Comstock, J.; Xu, L.P.; Wang, J.P. Development of an Axiom Sugarcane100K SNP array for genetic map construction and QTL identification. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 2829–2845. [CrossRef]

- Mccouch, S.; Cho, Y.G.; Yano, M.; Kinoshita, T. Report on QTL nomenclature. Rice Genetics Newsletter. 1997, 14, 11–13.

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Deng Y.W.; Ning Y.W.; He Z.H.; Wang, G.L. Exploiting broad-spectrum disease resistance in crops: From molecular dissection to breeding. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 575–603. [CrossRef]

- Miedaner, T.; Juroszek, P. Climate change will influence disease resistance breeding in wheat in Northwestern Europe. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1771–1785. [CrossRef]

- Nejat, N.; Rookes, J.; Mantri, N.L.; Cahill, D.M. Plant-pathogen interactions: toward development of next-generation disease-resistant plants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 229–237. [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, M.C.; Newman, T.E.; Thomas, W.J.W.; Batley, J.; Edwards, D. The complex relationship between disease resistance and yield in crops. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2612–2623. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.J.; Kong, R, An, D.S.; Zhang, X.J.; Li, Q.B; Nie, H.Z.; Liu, Y, Su, J.B Evaluation of a sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) hybrid F1 population phenotypic diversity and construction of a rapid sucrose yield estimation model for breeding. Plants. 2023, 12, 647. [CrossRef]

- Healey, A.L.; Garsmeur, O.; Lovell, J.T.; Shengquiang, S.; Sreedasyam, A.; Jenkins, J.; Plott, C.B.; Piperidis, N.; Pompidor, N.; Llaca, V.; Metcalfe, C.J.; Doležel, J.; Cápal, P.; Carlson, J.W.; Hoarau, J.Y.; Hervouet, C.; Zini, C.; Dievart, A.; Lipzen, A.; Williams, M.; Boston, L.B.; Webber, J.; Keymanesh, K.; Tejomurthula, S.; Rajasekar, S.; Suchecki, R.; Furtado, A.; May, G.; Parakkal, P.; Simmons, B.A.; Barry, K.; Henry, R.J.; Grimwood, J.; Aitken, K.S.; Schmutz, J.; D’Hont, A. The complex polyploid genome architecture of sugarcane. Nature. 2024, 628, 804–810. [CrossRef]

- Piperidis, G.; Piperidis, N.; D’Hont, A. Molecular cytogenetic investigation of chromosome composition and transmission in sugarcane. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2010, 284, 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre, T.W.A.; da Silva Pereira, G.; Margarido, G.R.A.; Gazaffi, R.; Barreto, F.Z.; Anoni, C.O.; Cardoso-Silva, C.B.; Costa, E.A.; Mancini, M.C.; Hoffmann, H.P.; de Souza, A.P.; Garcia, A.A.F.; Carneiro, M.S. GBS-based single dosage markers for linkage and QTL mapping allow gene mining for yield-related traits in sugarcane. BMC Genomics. 2017, 18, 72. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, F.; Wang, Z.T; Wu, Q.B.; Cheng, W.; Que, Y.X.; Xu L.P. Mapping of QTLs and screening candidate genes associated with the ability of sugarcane tillering and ratooning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2793. [CrossRef]

- Lowry, D.B.; Lovell, J.T.; Zhang, L.; Bonnette, J; Fay, P.A.; Mitchell, R.B.; Lloyd-Reilley, J.; Boe, A.R.; Wu, Y.Q.; Rouquette Jr, F.M.; Wynia, R.L.; Weng, X.Y.; Behrman, K.D.; Healey, A.; Barry, K.; Lipzen, A.; Bauer, D.; Sharma, A.; Jenkins, J.; Schmutz, J.; Fritschi, F.B.; Juenger, T.E. QTL × environment interactions underlie adaptive divergence in switchgrass across a large latitudinal gradient. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2019, 116, 12933–12941. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Y.; Wang, L.Y.; Wei, K.; Tan, L.Q.; Su, J.J.; Cheng, H. High-density SNP linkage map construction and QTL mapping for flavonoid-related traits in a tea plant (Camellia sinensis) using 2b-RAD sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2018, 19, 955. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.J.; Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, M.; Xie, X.Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, B.C.; Qin, F.; Yang, X.H. QTL mapping for flowering time in a maize-teosinte population under well-watered and water-stressed conditions. Mol. Breed. 2023, 43, 67. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, C.L.; Whan, V.A.; Croft, B.; Magarey, R.; Smith, G.R. Identification and validation of molecular markers associated with pachymetra root rot and brown rust resistance in sugarcane using map- and association-based approaches. Mol. Breeding. 2005, 16, 151–161. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, A.; Deo, J.; Deomano, E.; Wei, X.M.; Jackson, P.; Aitken, K.S.; Manimekalai, R.; Mohanraj, K.; Hemaprabha, G.; Ram, B.; Viswanathan, R.; Lakshmanan, P. Combining genomic selection with genome-wide association analysis identified a large-effect QTL and improved selection for red rot resistance in sugarcane. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1021182. [CrossRef]

- Pinar, H.; Bulbul, C.; Simsek, D.; Shams, M.; Mutlu, N.; Ercisli, S. Development of molecular markers linked to QTL/genes controllıng Zn effıcıency. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 5273–5281. [CrossRef]

- Boava, L.P.; Cristofani-Yaly, M.; Stuart, R.M.; Machado, M.A. Expression of defense-related genes in response to mechanical wounding and phytophthora parasitica infection in poncirus trifoliata and citrus sunki. Physiol. Mol. Plant P. 2011, 76, 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Su, Y.C.; Ling, H. Ahmad, W.; Gao, S.W.; Guo, J.L.; Que Y.X.; Xu L.P. A sugarcane pathogenesis-related protein, ScPR10, plays a positive role in defense responses under Sporisorium scitamineum, SrMV, SA, and MeJA stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 1427–1440. [CrossRef]

- Kaupp, U.B.; Seifert, R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol. Reviews. 2002, 82, 769–824. [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.; DeFalco, T.A.; Moeder, W.; Yoshioka, K. The Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels AtCNGC2 and AtCNGC4 work in the same signaling pathway to regulate pathogen defense and floral transition. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 611–24. [CrossRef]

- Kale, L.; Nakurte, I.; Jalakas, P.; Kunga-Jegere, L.; Brosché, M.; Rostoks, N. Arabidopsis mutant dnd2 exhibits increased auxin and abscisic acid content and reduced stomatal conductance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 140, 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.D.; Liu, S.M.; Ma, Y.Y.; Hu, L.N.; Yan, H.X. Analysis of CNGC family members in Citrus clementina (Hort. ex Tan.) by a genome-wide approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 960. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.Y.; Yin, G.; Chai, M.; Sun, L.; Wei, H.L.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.F.; Fu, X.K.; Li, S.Y. Systematic analysis of CNGCs in cotton and the positive role of GhCNGC32 and GhCNGC35 in salt tolerance. BMC Genomics. 2022, 23, 560. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, A.; Ren, Y.L.; Wu, F.Q.; Wang, G.; Xu, Y.; Lei, C.L.; Zhu, S.S.; Pan, T.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Tan, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.P.; Jin, X.; Luo, S.; Zhou, C.L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.L.; Wang, S.; Meng, L.Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Chen, X.; Lin, Q.B.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.P.; Cheng, Z.J.; Wang, J.L.; Tian, Y.L.; Liu, S.J.; Jiang, L.; Wu, C.Y.; Wang, E.T.; Zhou, J.M.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, H.Y.; Wan, J.M. A cyclic nucleotide-gated channel mediates cytoplasmic calcium elevation and disease resistance in rice. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 820–831. [CrossRef]

- Vorwerk, S.; Schiff, C.; Santamaria, M.; Koh, S.; Nishimura, M.; Vogel, J.; Somerville, C.; Somerville, S. EDR2 negatively regulates salicylic acid-based defenses and cell death during powdery mildew infections of Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 35. [CrossRef]

| Habitats/Crops | 2015/Plant cane | 2016/First ratoon | 2017/Second ratoon | 2018/Plant cane | 2019/First ratoon | 2020/Plant cane |

| 2015/Plant cane 2016/First ratoon 2017/Second ratoon 2018/Plant cane 2019/First ratoon 2020/Plant cane |

1.000 0.63*** 0.54*** 0.60*** 0.61*** 0.42*** |

1.000 0.51*** 0.67*** 0.60*** 0.28*** |

1.000 0.52*** 0.53*** 0.29*** |

1.000 0.57*** 0.31*** |

1.000 0.29*** |

1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).