Submitted:

28 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genome Resequencing

2.2. SNP Detection

2.3. Bin Markers

2.4. Genetic Linkage Map

2.5. Linkage Assessment and Collinearity Analysis

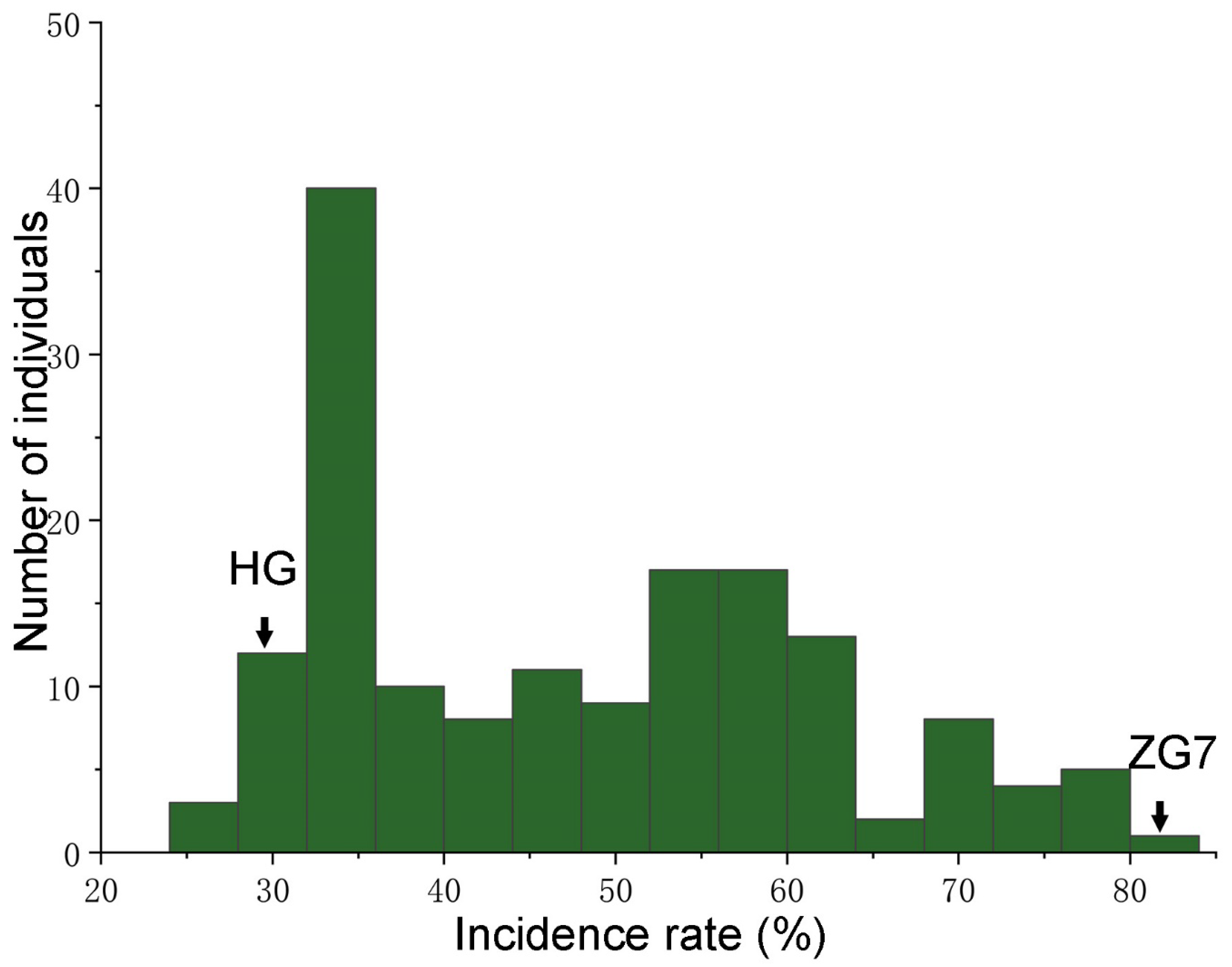

2.6. Analysis of Passion Fruit Stem Rot

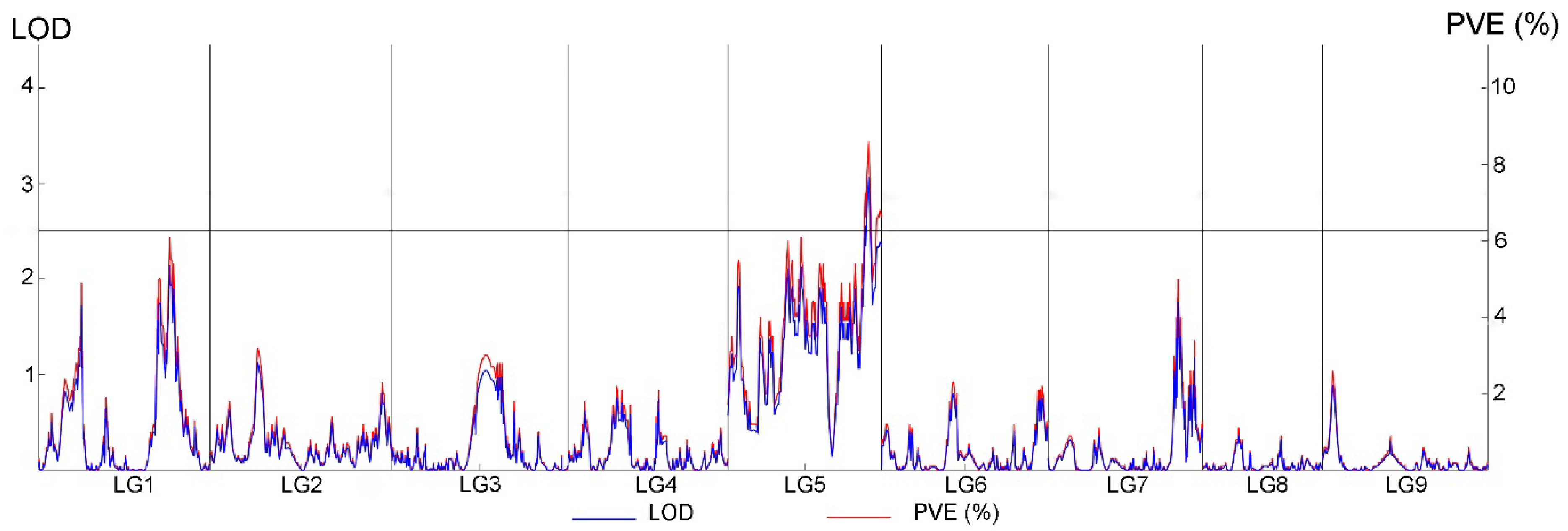

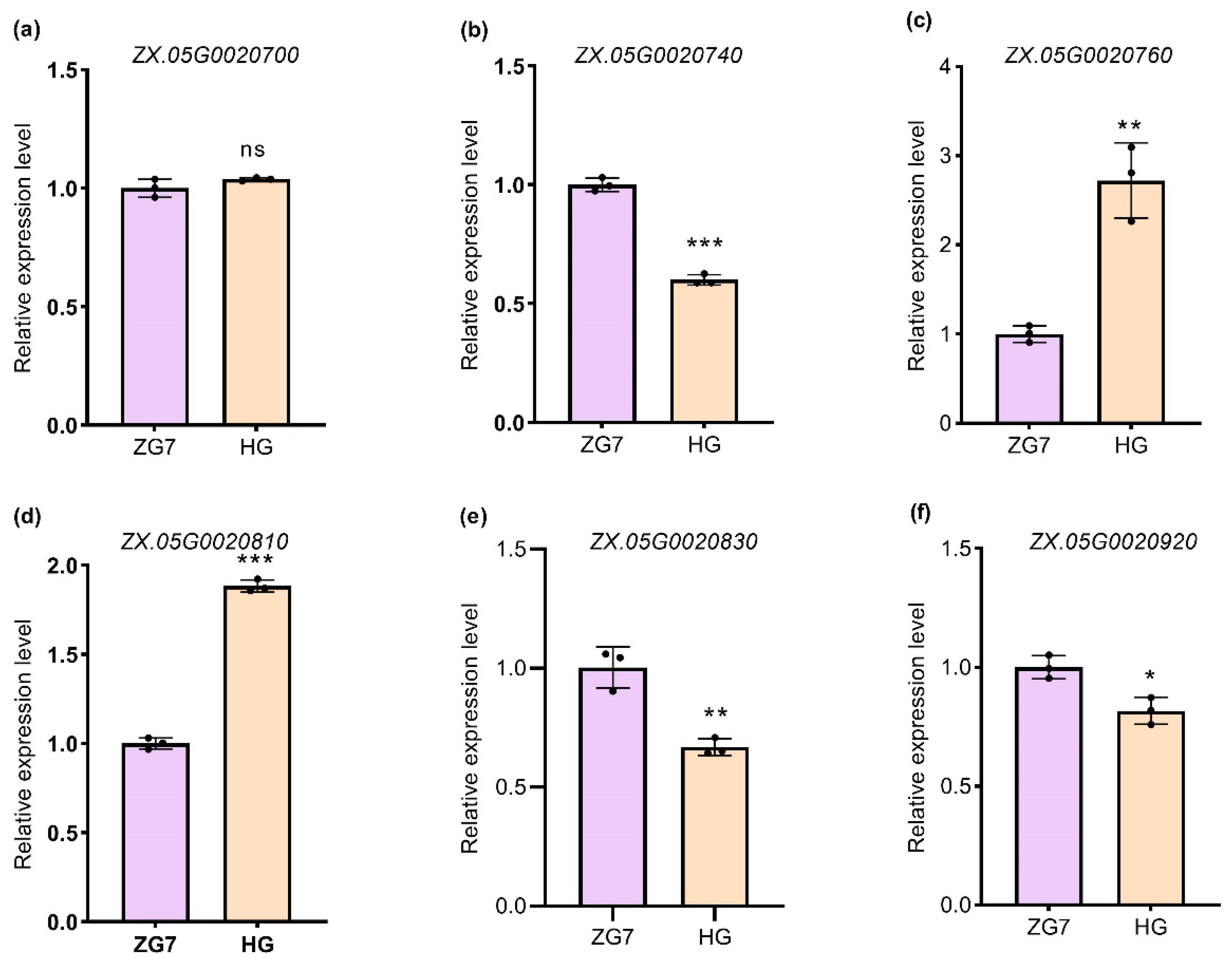

2.7. Mapping of Resistance Loci for Stem Rot and Analysis of Candidate Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. DNA Extraction

4.3. Resequencing and SNP Calling

4.4. Genetic Maping

4.5. QTL Analysis

4.6. Candidate Gene Analysis

4.7. RT-qPCR

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, R.; Wiesner-hanks, T.; Wisser, R.; Balint-kurti, P. Navigating complexity to breed disease-resistant crops. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, M.S.; Camargo, L.E.; Coelho, A.S.; Vencovsky, R.; Rui, P.L.; Stenzel, N.M.; Vieira, M.L. RAPD-based genetic linkage maps of yellow Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims. f. flavicarpa Deg.). Genome 2002, 45, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.; Lopes, M.T.; Carneiro, M.S.; Matta, F.P.; Camargo, L.E.; Vieira, M.L. Linkage and mapping of resistance genes to Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. passiflorae in yellow Passion fruit. Genome 2006, 49, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, E.J.; Vieira, M.; Garcia, A.; Munhoz, C.F.; Margarido, G.; Consoli, L.; Matta, F.P.; Moraes, M.C.; Zucchi, M.I.; Fungaro, M. An integrated molecular map of yellow Passion fruit based on simultaneous Maximum-likelihood estimation of linkage and linkage phases. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 133, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganal, W.; Altmann, T.; Röder, M.S. SNP identification in crop plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa., Z.D.; Munhoz, C.F.; Vieira, M. Report on the development of putative functional SSR and SNP markers in Passion fruits. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, K.; Sorensen, T.R.; Stracke, R.; Torjek, O.; Altmann, T.; Mitchell-olds, T.; Weisshaar, B. Large-scale identification and analysis of genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphisms for mapping in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Ni, P.; Dong, W.; Hu, S.; Zeng, C.; et al. The genomes of oryza sativa: a history of duplications. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareno, A.G.; Dick, C.W.; Lohmann, L.G. Tangled banks: a landscape genomic evaluation of wallace’s riverine barrier hypothesis for three Amazon plant species. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 28, 980–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Dong, S.; Zhang, S.; Wei, X.; Xie, Q.; Ding, Q.; Xia, R.; Zhang, X. Chromosome-level reference genome assembly provides insights into aroma biosynthesis in Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 21, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Chen, L.H.; Fan, B.L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, B.Y.; Gao, M.; Yuan, M.H.; Tahir, U.M.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Integrative multiomics profiling of Passion fruit reveals the genetic basis for fruit color and aroma. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 2491–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Ma, X.; Yao, L.; Liu, Y.; Du, F.; Yang, X.; Xu, M. qRfg3, a novel quantitative resistance locus against gibberella stalk ROT in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Song, F.; Sun, S.; Guo, C.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X. Characterization and molecular mapping of two novel genes resistant to Pythium stalk rot in maize. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Song, J.; Du, W.P.; Xu, L.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, X.L.; Yu, G.R. Identification, mapping, and molecular marker development for Rgsr8.1: a new quantitative trait locus conferring resistance to Gibberella stalk rot in maize (Zea mays L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Sun, M.; Zhang, P.; Ren, X.; Zhao, S.; Li, M.; Ren, Z.; Yuan, M.; Ma, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Genome-wide association studies on Chinese wheat cultivars reveal a novel Fusarium crown rot resistance quantitative trait locus on chromosome 3BL. Plants 2024, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Sun, C.; Chen, F. A loss-of-function of the dirigent gene TaDIR-B1 improves resistance to Fusarium crown rot in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 866–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Yan, X.; Yuan, M.; Chen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, X.; Qiao, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. A cell wall invertase modulates resistance to fusarium crown rot and sharp eyespot in common wheat. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1814–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, N.; Wang, C.; Xu, M. Cytological and molecular characterization of quantitative trait locus qRfg1, which confers resistance to Gibberella stalk rot in maize. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Yang, Q. Transcriptome analysis of maize resistance to Fusarium graminearum. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ma, X.; Song, W.; Zhao, J.; Xu, M. A transposon-directed epigenetic change in ZmCCT underlies quantitative resistance to Gibberella stalk rot in maize. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, D.; Ma, C.; Wang, L.; Yao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, M.; Xu, M. The auxin-regulated protein ZmAuxRP1 coordinates the balance between root growth and stalk rot disease resistance in maize. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, N.; Bai, W.Z.; Wei, W.Q.; Yuan, T.L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.Z.; Tang, W.H. Fungal CFEM effectors negatively regulate a maize wall-associated kinase by interacting with its alternatively-spliced variant to dampen resistance. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Ma, W.; He, R.; Cao, H.; Xing, J.; Zhang, K.; Dong, J. Function of ZmBT2a gene in resistance to pathogen infection in maize. Phytopathol. Res. 2024, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. CUTADAPT removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Feng, Q.; Qian, Q. High-throughput genotyping by whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ma, C.; Hong, W.; Huang, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Zeng, H.; Deng, D.; Xin, H.; Song, J.; et al. Construction and analysis of high-density linkage map using high-throughput sequencing data. PLoS One 2014, 9, e98855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, W.; Tian, Q.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; Yang, X.; Mou, H. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals the cold acclimation during chilling stress in sensitive and resistant Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) cultivars. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Fan, H.; Tu, Z.; Cai, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, A.; Xu, M. Stable reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 5985–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Huang, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; Ma, F.; Wu, B.; Xu, Y.; Xu, B.; Chen, D.; Zou, M.; et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly provides insights into the evolution and flavor synthesis of Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims). Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Yan, S.; Huang, W.; Yang, J.; Dong, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Yang, T.; Mao, X.; Zhu, X.; et al. NAC transcription factor ONAC066 positively regulates disease resistance by suppressing the ABA signaling pathway in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018, 98, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, N.; Altartouri, B.; Hegde, N.; Duggavathi, R.; Nazarian-firouzabadi, F.; Kushalappa, A.C. TaNAC032 transcription factor regulates lignin-biosynthetic genes to combat Fusarium head blight in wheat. Plant Sci. 2021, 304, 110820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jost, M.; Outram, M.A.; Friendship, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, A.; Periyannan, S.; Bartoš, J.; Holušová, K.; Doležel, J.; et al. A pathogen-induced putative NAC transcription factor mediates leaf rust resistance in barley. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bi, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, X.; Gao, Y.; Noman, M.; Li, D.; Song, F. A NAC transcription factor MNAC3-centered regulatory network negatively modulates rice immunity against blast disease. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shi, G.; Zhou, J.; Tian, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, W.; Xia, X.; Mou, H.; Yang, X. Identification and validation of stem rot disease resistance genes in Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). Hortic. Sci. 2025, 52, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Denancé, N.; Ranocha, P.; Oria, N.; Barlet, X.; Rivière, M.P.; Yadeta, K.A.; Hoffmann, L.; Perreau, F.; Clément, G.; Maia-grondard, A.; et al. Arabidopsis wat1 (walls are thin1)-mediated resistance to the bacterial vascular pathogen, Ralstonia solanacearum, is accompanied by cross-regulation of salicylic acid and tryptophan metabolism. Plant J. 2013, 73, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanika, K.; Schipper, D.; Chinnappa, S.; Oortwijn, M.; Schouten, H.J.; Thomma, B.; Bai, Y. Impairment of tomato WAT1 Enhances resistance to Vascular wilt fungi despite severe growth defects. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 721674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rêgo, M.M.; Rêgo, E.R.; Bruckner, C.H.; Silva, E.A.; Finger, F.L.; Pereira, K.C. Pollen tube behavior in yellow Passion fruit following compatible and incompatible crosses. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 101, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, Z.; Guo, T.; Yuan, C.; Liu, J. Construction of a high-density genetic map and QTL localization of body weight and wool production related traits in Alpine Merino sheep based on WGR. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xie, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, S. Construction of the first high-density genetic linkage map and identification of seed yield-related QTLs and candidate genes in Elymus sibiricus, an important forage grass in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Duan, D. High-density SNP-based QTL mapping and candidate gene screening for yield-related blade length and width in Saccharina japonica (Laminariales, Phaeophyta). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelam, K.; Mahajan, R.; Gupta, V.; Bhatia, D.; Gill, B.K.; Komal, R.; Lore, J.S.; Mangat, G.S.; Singh, K. High-resolution genetic mapping of a novel bacterial blight resistance gene xa-45(t) identified from Oryza glaberrima and transferred to Oryza sativa. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ear, S.; Snoek, L.B.; Nijveen, H.; Laj, W.; Jiménez-gómez, J.M.; Hilhorst, H.; Ligterink, W. Construction of a High-Density genetic map from RNA-Seq data for an arabidopsis Bay-0 × shahdara RIL population. Front. Genet. 2017, 8, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Hao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Di, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Yong, H.; et al. Genetic dissection of maize plant architecture with an ultra-high density bin map based on recombinant inbred lines. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Chang, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, D.; Wu, T.; Zhang, X.; Han, Z. A dense SNP genetic map constructed using restriction site-associated DNA sequencing enables detection of QTLs controlling Apple fruit quality. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Sheng, X.; Shen, Y.; Branca, F.; Gu, H. Construction of a High-Density genetic map and identification of LOCI related to hollow stem trait in broccoli (brassic oleracea l. italica). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasawa, K.; Tanaka, M.; Takahata, Y.; Ma, D.; Cao, Q.; Liu, Q.; Zhai, H.; Kwak, S.S.; Cheol, J.J.; Yoon, U.H.; et al. A high-density SNP genetic map consisting of a complete set of homologous groups in autohexaploid sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Ohtani, M.; Mitsuda, N.; Kubo, M.; Ohme-takagi, M.; Fukuda, H.; Demura, T. VND-INTERACTING2, a NAC domain transcription factor, negatively regulates xylem vessel formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, R.; Ma, J.; Xu, Z.; Shang-guan, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Y. The RLCK-VND6 module coordinates secondary cell wall formation and adaptive growth in rice. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Shi, Y.K.; Gao, X.Y.; Zhao, X.F.; Zhang, H.Q.; Zhou, F.L.; Zhang, H.J.; Ma, B.Q.; Zhai, R.; Yang, C.Q.; et al. Transcription factor PbNAC71 regulates xylem and vessel development to control plant height. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor-teeples, M.; Lin, L.; De lucas, M.; Turco, G.; Toal, T.W.; Gaudinier, A.; Young, N.F.; Trabucco, G.M.; Veling, M.T.; Lamothe, R.; et al. An arabidopsis gene regulatory network for secondary cell wall synthesis. Nature 2015, 517, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, K.; Takasaki, H.; Mizoi, J.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-shinozaki, K. NAC transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1819, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.H. Lignin biosynthesis and its diversified roles in disease resistance. Genes (Basel) 2024, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, L.; Zheng, L. Lignins: biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.W.; Choi, S.; Jin, X.; Jung, S.E.; Choi, J.W.; Seo, J.S.; Kim, J.K. Transcriptional activation of rice CINNAMOYL-CoA REDUCTASE 10 by OsNAC5, contributes to drought tolerance by modulating lignin accumulation in Roots. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Yang, S.; Feng, L.; Chu, J.; Dong, H.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Yamamoto, N.; Zheng, A.; et al. Red-light receptor phytochrome B inhibits BZR1-NAC028-CAD8B signaling to negatively regulate rice resistance to sheath blight. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang., B.; Shang-guan, K.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Wu, K.; Xu, Z.; Fu, X.; et al. A gibberellin-mediated DELLA-NAC signaling cascade regulates cellulose synthesis in rice. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Huang, A.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Feng, Y.; Pemberton, E.; Chen, C. OsNAC45 plays complex roles by mediating POD activity and the expression of development-related genes under various abiotic stresses in rice root. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 84, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Huang, L.; Hong, Y.; Ding, X.S.; Nelson, R.S.; Zhou, X.; Song, F. Functions of rice NAC transcriptional factors, ONAC122 and ONAC131, in defense responses against Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Mol Biol 2013, 81, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, D.; Song, F. The NAC transcription factor ONAC083 negatively regulates rice immunity against Magnaporthe oryzae by directly activating transcription of the RING-H2 gene OsRFPH2-6. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 854–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Lin, S.; Wang, Y.; Guo, B.; Song, X.; Ding, S.; Zheng, L.; Feng, R.; Chen, S.; et al. Osa-miR164a targets OsNAC60 and negatively regulates rice immunity against the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant J. 2018, 95, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wei, J.; Song, N.; Wang, N.; Zhao, J.; Kang, Z. A novel wheat NAC transcription factor, TaNAC30, negatively regulates resistance of wheat to stripe rust. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Li, B.; Rizwan, H.M.; Sun, K.; Zeng, J.; Shi, M.; Guo, T.; Chen, F. Genome-wide identification and comprehensive analyses of NAC transcription factor gene family and expression analysis under Fusarium kyushuense and drought stress conditions in Passiflora edulis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranocha, P.; Denancé, N.; Vanholme, R.; Freydier, A.; Martinez, Y.; Hoffmann, L.; Köhler, L.; Pouzet, C.; Renou, J.P.; Sundberg, B.; et al. Walls are thin 1 (WAT1), an Arabidopsis homolog of Medicago truncatula NODULIN21, is a tonoplast-localized protein required for secondary wall formation in fibers. Plant J. 2010, 63, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Dixon, R.A. Current models for transcriptional regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in grasses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglou, E.; Hanika, K.; Mohd, N.M.; Kohlen, W.; Van der wolf, J.M.; Visser, R.; Bai, Y. Inactivation of tomato WAT1 leads to reduced susceptibility to Clavibacter michiganensis through downregulation of bacterial virulence factors. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1082094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Total Clean Reads (bp) | Total Clean Bases (bp) | Q30 (%) | GC content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZG7 | 141877476 | 41987231840 | 94.26 | 42.32 |

| HG | 141115213 | 41852618618 | 94.39 | 42.19 |

| Offspring | 2939344344 | 868334262166 | 93.94 | 41.95 |

| Total | 3222337033 | 952174112624 | 93.95 | 41.96 |

| Sample ID | Clean Reads | Mapped (%) | Properly_mapped (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZG7 | 283754952 | 98.63 | 79.65 |

| HG | 282230426 | 98.75 | 84.35 |

| Offspring (average) | 36970400 | 98.18 | 83.02 |

| Sample ID | Depth | Coverage ratio 1× (%) | Coverage ratio 5× (%) | Coverage ratio 10× (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZG7 | 24 | 99.07 | 97.35 | 90.22 |

| HG | 28 | 82.59 | 74.62 | 69.03 |

| Offspring (average) | 3.92 | 74.87 | 31.87 | 9.14 |

| Sample ID | SNP Number | Transition Numbers | Transverison Numbers | Ti/Tv Ratio | Heterozygosity Number | Homozygosity Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZG7 | 5849756 | 4096174 | 1753582 | 2.34 | 3566274 | 2283482 |

| HG | 5849756 | 4096174 | 1753582 | 2.34 | 946585 | 4903171 |

| Linkage group | Total Bin Marker | Total Distance (cM) | Average Distance (cM) | Max Gap (cM) | Gaps<5 cM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG1 | 956 | 183.92 | 0.19 | 8.65 | 98.12% |

| LG2 | 371 | 196.03 | 0.53 | 7.5 | 98.38% |

| LG3 | 509 | 189.5 | 0.37 | 14.49 | 99.02% |

| LG4 | 308 | 171.98 | 0.56 | 5.95 | 99.67% |

| LG5 | 378 | 165.26 | 0.44 | 5.34 | 99.73% |

| LG6 | 407 | 179.08 | 0.44 | 10.01 | 99.51% |

| LG7 | 537 | 166.35 | 0.31 | 11.9 | 99.44% |

| LG8 | 364 | 129.04 | 0.36 | 10.91 | 99.45% |

| LG9 | 376 | 177.87 | 0.47 | 15.45 | 98.93% |

| Total | 4206 | 1559.03 | 0.37 | 15.45 | 98.12% |

| Gene | Annotation |

|---|---|

| ZX.05G0020700 | NAC domain-containing protein 14 |

| ZX.05G0020740 | NAC domain-containing protein 91 |

| ZX.05G0020760 | DNA/RNA polymerases superfamily protein |

| ZX.05G0020810 | Protein ENHANCED DISEASE RESISTANCE 4 |

| ZX.05G0020830 | B3 domain-containing transcription factor |

| ZX.05G0020920 | WAT1-related protein |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).