1. Introduction

Hulless barley (

Hordeum vulgare L. var.

nudum), also known as naked barley, is a dietary staple on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau where it constitutes 95% of cultivated barley [

1]. Renowned for its short growing cycle and adaptability to harsh climates, hulless barley is essential for food security in the region. However, it is highly susceptible to barley leaf stripe disease, a seed-borne fungal disease caused by

Pyrenophora graminea Ito & Kuribayashi [anamorph:

Drechslera graminea (Rabenh.) Shoemaker]. Severe outbreaks can reduce yields by 10%-25% [

2]. Since the disease was first documented in eastern Tibet in the late 1970s [

3], it has spread extensively, posing significant threats to food security and the economic stability of farming communities.

Barley leaf stripe spreads through fungal mycelia that colonize seeds, residing between the pericarp, hull, and seed coat. Upon seed germination, the fungus initiates a new infection cycle [

4,

5]. Chemical seed treatments are commonly used to manage the disease, but these treatments can negatively impact the fragile ecosystems of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Developing disease-resistant hulless barley varieties offers an environmentally sustainable alternative to chemical pesticides. This approach not only reduces environmental harm by preserving soil health and water quality but also lowers production costs and improves yield stability, benefiting both the environment and local farming communities [

6]. Sustainable disease management through resistant varieties ensures long-term agricultural productivity and economic resilience.

Understanding the genetic basis of disease resistance is crucial for developing barley varieties resistant to leaf stripe disease. Genetic mapping has identified specific genes and quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with this trait. The first such gene,

Rdg1a, was mapped to the long arm of chromosome 2H of barley cultivar Vada, which also carries powdery mildew resistance gene

MlLa, derived from

H. laevigatum L. [

7].

Rdg1a was later found in

H. spontaneum C. Koch., a wild barley relative [

8]. Another resistance gene,

Rdg2a, was located on the short arm of chromosome 7H and was precisely mapped using high-resolution techniques [

9]. Additionally, Si et al. [

10] characterized

Rdg3, a distinct leaf stripe resistance gene located on chromosome 7HS. These discoveries demonstrate the genetic diversity that contributes to barley's resistance to leaf stripe disease.

QTL research has further elucidated the genetic architecture of barley’s resistance. Studies using bi-parental populations, progeny derived from crosses of two parental lines, have been instrumental in detecting resistance QTL. For example, Pecchioni et al. [

11] identified a QTL on chromosome 7H conferring partial resistance in the Proctor × Nudinka population. Similarly, Arru et al. [

12,

13] reported a major QTL on chromosome 2H, a minor QTL on chromosome 7H, and five isolate-specific QTL on chromosomes 2H and 3H. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have complemented bi-parental mapping by linking specific genetic markers to barley leaf stripe resistance, further broadening our understanding of resistance loci [

14,

15]. Collectively, these studies emphasize the complexity of resistance regulation and provide a robust framework for targeted breeding initiatives aimed at developing disease-resistant barley varieties.

In hulless barley, bulk segregant analysis combined with RNA-seq (BSR-seq) was applied to identify resistance-associated genes in a Kunlun 14 × Z1141 population [

16]. This approach revealed two genes,

HvnRGA on chromosomes 5H and

HvnWAK on chromosome 6H, which may play significant roles in defense against leaf stripe disease. That study represents an early effort in elucidating the genetic mechanisms underlying resistance to leaf stripe disease in hulless barley.

To expand the resistance resource pool, we evaluated diverse hulless barley germplasm, including landraces, wild accessions indigenous to Tibet, and international varieties [

17,

18]. Among these, the Tibetan landrace Teliteqingke demonstrated strong resistance to two isolates of

P. graminea [

18]. To explore the genetic basis of this resistance, we crossed Teliteqingke with the susceptible landrace Dulihuang, creating a segregating population for genetic analysis. This study examined the inheritance patterns of resistance and utilized BSA-SNP array and RNA-seq to identify candidate genes involved in disease resistance. Additionally, quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was employed to confirm the differential expression of these candidate genes. This research provides a foundational understanding of the genetic basis of resistance in Teliteqingke and establishes valuable tools for the genetic mapping of leaf stripe resistance genes. Furthermore, it contributes to the integration of these resistance traits into breeding programs, facilitating the development of resilient hulless barley varieties. These efforts support sustainable agriculture and food security on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau by enhancing the crop’s ability to withstand leaf stripe disease.

2. Results

2.1. Genetic Analysis of Leaf Stripe Resistance in Teliteqingke

We conducted the inheritance pattern of leaf stripe resistance in Teliteqingke using two sets of F

3 progenies derived from a cross with the susceptible landrace Dulihuang. Both sets were inoculated with the

P. graminea strain FS-18. Teliteqingke consistently displayed resistance, while Dulihuang was susceptible (

Figure 1). In the first test of the segregating population, we observed 141 resistant and 15 susceptible families, which fitted a 15:1 segregation ratio (χ

2=1.60,

P=0.15). The second test confirmed this segregation pattern, also yielding a 15:1 ratio (χ

2=0.05

P=0.74). These results indicate that the resistance in Teliteqingke is likely governed by two dominant genes, consistent with a digenic inheritance pattern.

Table 1.

Genetic analysis of leaf stripe resistance gene in hulless barley landrace Teliteqingke.

Table 1.

Genetic analysis of leaf stripe resistance gene in hulless barley landrace Teliteqingke.

| Parents and cross |

Generations |

Total number of lines |

No. of resistant lines |

No. of susceptible lines |

Expected ratio |

χ2

|

P-value |

| Teliteqingke |

P1 |

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Dulihuang |

P2 |

|

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

| P1 × P2 |

F3

|

155 |

141 |

14 |

15 |

1 |

1.60 |

0.15 |

| P1 × P2 |

F3

|

155 |

137 |

18 |

15 |

1 |

0.05 |

0.74 |

2.2. Identification of Genetic Loci Associated with Leaf Stripe Resistance in Teliteqingke Using BSA-SNP Array

To identify the genetic loci conferring resistance, we performed a 40K Genotyping by Target Sequencing (GBTS) SNP array on two contrasting DNA bulks (BulkR and BulkS) and their parental lines. This analysis generated 11.42 Gb of, high-quality, clean data, representing over 86% of the raw sequencing data. Sequencing quality was robust, with Q20 (bases with ≤1% error probability) and Q30 (bases with ≤1% error probability) metrics exceeding industry standards (

Table 2). Nucleotide composition analysis confirmed a balanced distribution of adenine/thymine (A/T) and guanine/cytosine (G/C) bases, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of downstream analyses. Clean base conversion rates were over 90% for the resistant (BulkR) and susceptible (BulkS) samples and nearly 88% for the parental lines, further validating the dataset’s reliability. These high-quality sequencing results establish a strong basis for identifying genetic loci linked to leaf stripe resistance in Teliteqingke.

The alignment rate of clean reads to the reference genome was high for both Teliteqingke (95.55%) and Dulihuang (95.84%), ensuring reliable data for variant analysis. We identified 517,089 SNPs, including 85,821 synonymous mutations (which do not alter amino acid sequences) and 431,268 non-synonymous SNPs (which result in amino acid changes). Additionally, we detected 39,263 insertion or deletion (InDel) sites, where nucleotides are either inserted or deleted. After applying stringent filtering criteria to focus on high-confidence variants, we reduced the dataset to 8,745 SNPs and 856 InDels for further investigation. At a 95% confidence level, our refined analysis identified 1,376 SNPs and 162 InDels as potential candidates for leaf stripe resistance. Using the SNP-index algorithm, which identifies associations between genetic variants and phenotypic traits, we identified major genetic factors on chromosomes 3H and 7H in Teliteqingke (

Figure 2).

2.3. Identification of Genetic Loci Associated with Leaf Stripe Resistance in Teliteqingke Using RNA-seq

To further investigate the genetic factors conferring resistance to leaf stripe disease in Teliteqingke, we conducted RNA-seq analysis on two contrasting bulks (BulkR and BulkS) and their parental lines. This analysis generated 55 Gb of high-quality, clean data, with Q20 and Q30 scores confirming sequencing accuracy and a balanced GC content ranging from 53.22% to 56.32% (

Table 3). The sequences mapped to the barley reference genome, MorexV3, with an average rate of 95.54%, indicating the reliable data for downstream analysis.

From the initial RNA-seq dataset, we detected 192,398 genetic variants, including 164,232 SNPs and 28,166 InDels. Among the SNPs, 134,073 were non-synonymous mutations that could potentially affect protein function. After applying stringent filtering criteria to improve reliability, we reduced the dataset to 3,870 high-quality SNPs and 294 high-quality InDels. Further refinement at a 95% confidence level yielded 298 SNPs and 20 InDels for detailed analysis. Using the SNP-index algorithm, we conducted an association analysis that localized the primary genetic factors for resistance to leaf stripe disease in Teliteqingke to chromosomes 3H (

Figure 3).

2.4. Co-Localization of Leaf Stripe Resistance-Associated Regions in Teliteqingke

To elucidate the genetic basis of leaf stripe resistance in Teliteqingke, we conducted an integrated analysis combining BSA-SNP array and RNA-seq data (

Figure 4). This approach identified two key candidate regions on chromosome 3H associated with resistance. One region spans a 1.03 Mb interval (28,196,935-29,224,714 bp) and contains 58 genes, while the other spans a 0.19 Mb interval (47,254,165-47,448,374 bp) and included 5 genes.

Within these regions, we identified seven genes likely involved in disease resistance, each encoding proteins with known or putative roles in plant defense mechanisms (

Table 4). These include a RING/U-box superfamily protein (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232110.1) implicated in ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation, an NBS-LRR disease resistance protein (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232120.1) crucial for pathogen recognition, a cysteine-rich receptor kinase (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232550.1) essential for pathogen perception, an ankyrin repeat protein family-like protein (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232140.1) involved in signal transduction, and an RNA recognition motif (RRM) protein (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232180.1) contributing to pathogen defense responses. Additionally, we found a protease HtpX (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232220.1) and a bZIP transcription factor (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232410.1) associated with stress responses. These results provide a detailed understanding of the genetic architecture underlying leaf stripe resistance in Teliteqingke, demonstrating specific genes that can serve as targets for improving barley’s disease resistance.

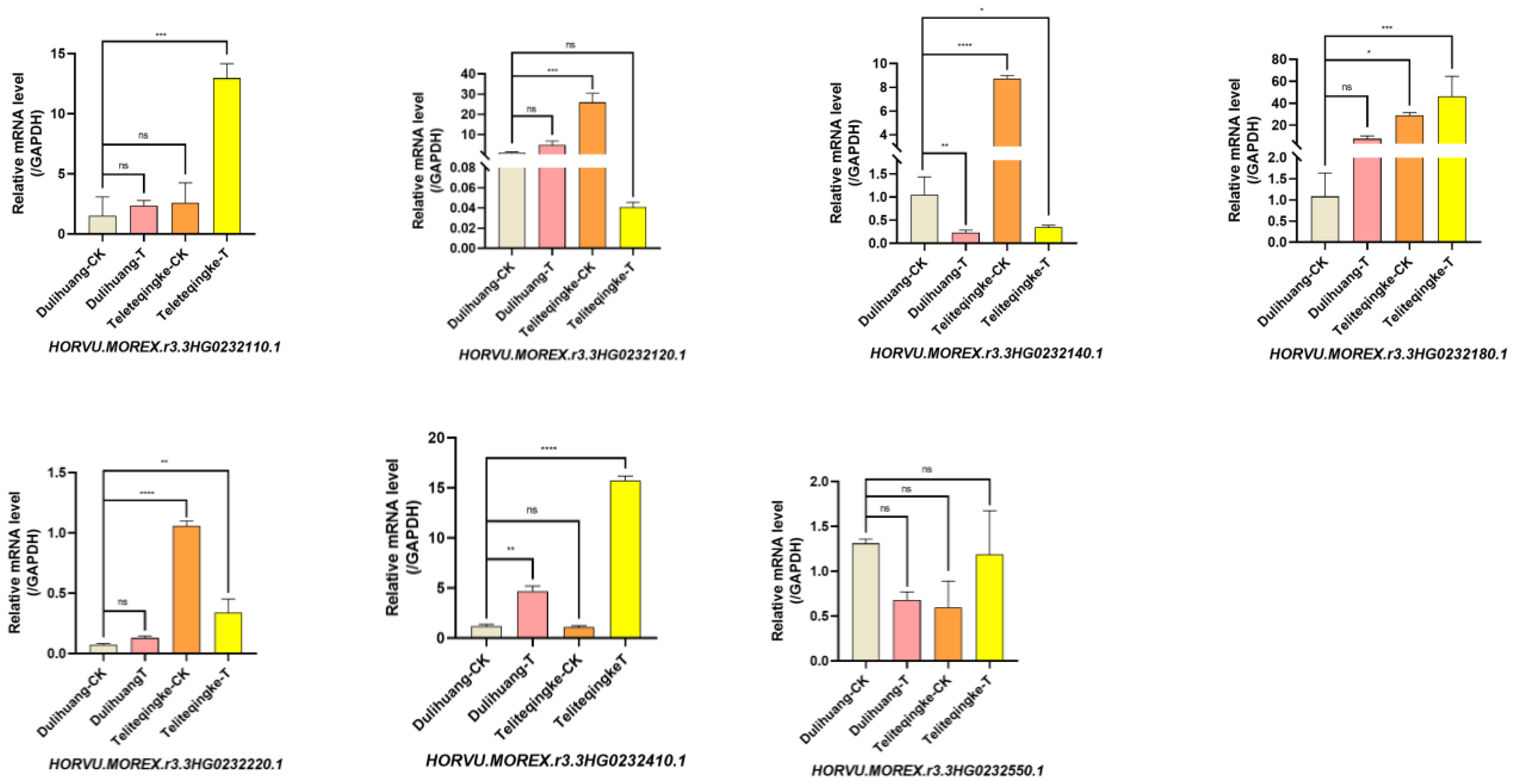

2.5. Expression of the Candidate Genes in Response to P. graminea

The RT-qPCR analysis of seven disease resistance-associated genes in the resistant landrace Teliteqingke and the susceptible landrace Dulihuang revealed distinct expression patterns following inoculation with

P. graminea (

Figure 5). Three genes,

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232110.1,

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232180.1, and

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232410.1, were upregulated in both landraces, with significantly stronger induction observed in Teliteqingke. Specifically,

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232180.1 and

HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232410.1 exhibited expression levels more than 30-fold and 15-fold higher, respectively, in Teliteqingke compared to Dulihuang, suggesting their crucial roles in active resistance mechanisms.

In contrast, two genes, HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232120.1 and HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232140.1, were induced in the susceptible Dulihuang but suppressed in the resistant Teliteqingke following pathogen infection, indicating differential responses between the two landraces. Additionally, in the absence of infection, HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232120.1, HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232180.1, and HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232410.1 were expressed at higher baseline levels in Teliteqingke. This suggests that these genes may contribute to the constitutive defense mechanisms that provide Teliteqingke with its inherent resistance to P. graminea.

3. Discussion

The resistance of barley to leaf stripe disease arise from complex defense mechanisms shaped by co-evolutionary interactions with the pathogen

P. graminea. This dynamic interplay determines the plant’s susceptibility or resistance to the disease [

19,

20]. While previous studies have primarily focused on cultivated barley [

9,

21], the resistance mechanisms in hulless barley, a crop adapted to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, remain underexplored. This study on the hulless barley landrace Teliteqingke contributes to a deeper understanding of the genetic basis of leaf stripe resistance in this distinctive crop.

Our genetic analysis revealed that Teliteqingke’s resistance to leaf stripe disease is controlled by two pairs of dominant genes, suggesting a digenic inheritance pattern. The genetic complexity observed demonstrates the need for advanced genomic tools to unravel resistance mechanisms in hulless barley. Using BSA-SNP array technology, we successfully identified chromosomal regions associated with resistance traits. This method has been widely applied in crops such as wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) to identify resistance loci to diseases like powdery mildew and stripe rust [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Our analysis revealed significant associations with leaf stripe resistance on chromosomes 3H and 7H in Teliteqingke. These results are consistent with the inheritance pattern inferred by our genetic analysis.

To complement the BSA-SNP array results, we performed RNA-seq analysis to identify the genetic factors linked to leaf stripe resistance in Teliteqingke. RNA-seq analysis enables the identification of differentially expressed genes across various samples [

27,

28,

29]. Data from bulked samples with contrasting resistance phenotypes, along with their parental lines, confirmed the association of specific regions on chromosome 3H with disease resistance. This consistency between BSA-SNP and RNA-seq analyses strengthens the reliability of our results. Integrating data from both methods allowed the identification of candidate regions on chromosome 3H containing genes potentially responsible for Teliteqingke’s resistance to leaf stripe disease.

Further validation through RT-qPCR identified seven candidate genes expressed in both Teliteqingke and the susceptible landrace Dulihuang following inoculation with P. graminea. Of these, significant upregulation was observed in Teliteqingke, particularly for HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232110.1, which encodes a RING/U-box s protein involved in uniquitin-mediated degradation, and HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0232120.1, which encodes an NBS-LRR protein critical for pathogen recognition. The later was expressed at higher baseline levels in Teliteqingke but was not induced in response to pathogen infection. These results suggest Teliteqingke employs a combination of active resistance mechanisms and constitutive defenses. Further functional validation using genetic transformation, genome editing, and mutagenesis assays is required to confirm the roles of these candidate genes.

Additionally, we identified a genomic region on chromosome 7H associated with the leaf stripe resistance in Teliteqingke. This region (28-29 Mb) differs from the previously identified

Rdg2a locus (46.50-46.54 Mb), which encodes a CC-NB-LRR-type protein (

HORVU.MOREX.r3.7HG0636710.1) as described by Bulgarelli et al. [

9,

30]. Our results suggest the presence of a novel resistance locus on chromosome 7H, which warrants further genetic mapping to confirm its identity and role in resistance.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant and Fungal Materials

The leaf stripe resistant hulless barley landrace Teliteqingke was obtained from the National Crop Germplasm Resource Bank in Xining, Qinghai province, while the susceptible landrace Dulihuang originated from Gannan Prefecture, Gansu province. Teliteqingke was crossed with Dulihuang to generate an F3 population consisting of 155 lines. Dulihuang served as the susceptible control in the assessment of leaf stripe resistance.

The

P. graminea strain FS-18 (GenBank ID: PQ452354), collected from a hulless barley field at the Xining Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Qinghai province in 2020, was used to evaluate the segregating population. This strain was characterized by morphological observations, phylogenetic analysis with internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences, and Koch's postulates, which confirmed the causal relationship between this strain and the leaf stripe disease [

18].

4.2. Assessment of Disease Resistance

The greenhouse assessment of

P. graminea resistance was conducted using a previously described method [

31]. Briefly, 5-mm diameter plugs of the activated pathogen strain FS-18 were extracted with a cork borer from a pure culture and inoculated into 500 mL conical flasks containing potato dextrose broth (PDB) culture medium, with five plugs per flask. The culture was incubated at 25°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 7-10 d until the mycelium fully colonized the medium. Then, 20 mL of the inoculum was poured into petri dishes containing 48-h germinated and disinfected seeds, and the dishes were incubated at 24°C in the dark for 38 h. Each replicate consisted of 15 seeds in a single pod. The plants were grown in an incubator under a 12-h light (20℃) and 12-h dark (12℃) cycle. To ensure experimental reliability, two sets of disease resistance assessments were conducted. Disease incidence was recorded 25 d post-seeding using a scale based on infection rates [

24]: 0 (immune, I), no infected plant; 1 (high resistance, HR), 0<incidence rate≤5%; 2 (moderate resistance, MR), 5%<incidence rate≤10%; 3 (moderate susceptibility, MS), 10%<incidence rate≤15%; and 4 (high susceptibility, HS), >15% of infected plants. The disease rate was calculated as follows: Disease rate (%) = (number of infected plants/total number of investigated plants) ×100%.

4.3. Analysis of BSA-SNP Array

To identify the disease resistance genes in hulless barley landrace Teliteqingke, we performed a BSA analysis. DNA was extracted from the leaves of the two hulless barley parents and their F

3 lines using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. DNA from 10 resistant and 10 susceptible F3 lines were pooled in equal proportions to create the BulkR (resistant) and BulkS (susceptible) pools. Genotyping by Target Sequencing (GBTS) technology [

29] was conducted by MolBreeding Biotech Ltd. (

https://en.molbreeding.com). The MorexV3 version of the barley genome, available in the Ensembl Plants database (

http://plants.ensembl.org/Hordeum_vulgare), was used as the reference genome.

Sample libraries were sequenced using the Illunima HiSeq sequencing platform. The resulting reads were filtered to obtain high-quality, clean reads suitable for downstream analysis. Mutations were identified using the UnifiedGenotyper module of the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) [

32], while the VariantFiltration module was used to remove unreliable SNP loci and sequence InDels between the test samples and the reference genome.

To identify candidate regions linked to disease resistance traits in Teliteqingke, we calculated the SNP-index for each locus. The SNP-index measures the frequency of SNPs within specific genomic regions. Statistical analysis of changes in the SNP-index [Δ(SNP-index)] was performed to identify genomic regions associated with disease resistance. This methodology enabled comprehensive and accurate mapping of the disease resistance gene in hulless barley [

33].

4.4. RNA-seq Analysis

To identify disease resistance genes in hulless barley Teliteqingke, we conducted RNA-seq analysis on the resistant and susceptible RNA pools, as well as their parental lines. RNA was extracted from the leaves of hulless barley using the Trizol method after full disease symptoms had developed. The quality and concentration of RNA were assessed to ensure that the samples were free from contamination and exhibited high integrity. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq platform by Beijing Novogene Co. Ltd. (

https://cn.novogene.com). The MorexV3 version of the barley genome (

http://plants.ensembl.org/Hordeum_vulgare) was used as the reference genome for analysis.

To evaluate the quality of the sequencing data, we calculated the base sequencing error rate using Phred scores, which indicate the probability of incorrect base calls. Additionally, we analyzed the base distribution and filtered the raw reads to generate high-quality clean reads for downstream analysis. Clean reads from Teliteqingke and Dulihuang were aligned to the MorexV3 reference genome using Hisat2 (version 2.2.1). SNPs and InDels were identified using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) [

32]. After filtering, the SNP-index algorithm was applied to conduct association analysis and identify genetic loci linked to disease resistance.

4.5. Screening and Verification of Genes Related to Leaf Stripe Resistance in Teliteqingke

To identify genes associated with leaf stripe resistance in Teliteqingke, we conducted a RT-qPCR to measure gene expression in response to P. graminea inoculation. Two-week-old seedlings of Teliteqingke and Dulihuang were inoculated with the P. graminea strain FS-18 as treatment groups, while mock-inoculated seedlings served as the control groups. Each treatment and control group included three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Inoculated plants were incubated in a controlled environment with a 12-h light cycle and a temperature alternating between 20°C and 12°C.

RNA was extracted from the leaves using the Trizol method, and cDNA was synthesized with the Prime Script™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). The reverse transcription reaction was conducted at 37°C for 15 min, followed by incubation at 85°C for 5 s, and stored at 4°C. The synthesized cDNA was preserved at -20°C for long-term storage.

Candidate gene sequences were retrieved from the barley reference genome based on their identification (ID) codes. RT-qPCR primers, listed in

Table 5, were designed using Primer premier5 software (

https://www.premierbiosoft.com/primerdesign) and synthesized by Qinghai Kemeiyi Biotechnology (Xining, China). RT-qPCR was performed using TB Green® premix Ex Taq™ II fluorescent Dye and ROX Reference Dye (TaKaRa, Beijing, China), with

18SrRNA serving as the internal reference gene. The reaction mixture (20 µL) consisted of 10.0 µL of the TB Green® premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (2×), 0.8 µL of PCR forward and reverse primers each (10 µmol/L), 0.4 µL of ROX Reference Dye (50×), 2.0 µL of cDNA template, and 6.0 µL of RNase free dH

2O. The amplification conditions included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2

–ΔΔCt method [

34].

4.6. Statistical Analysis

A Chi-squared test was used to determine the goodness of fit for the segregation ratio. Data on relative gene expression levels were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the significant difference was determined using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) method at

P < 0.05 or

P < 0.01). All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prisim8.4.3 software (

https://www.graphpad.com).

5. Conclusion

Our study advances the understanding of the genetic basis of leaf stripe resistance in the hulless barley cultivar Teliteqingke. By integrating BSA-SNP array and RNA-seq technologies, we identified a candidate region on chromosome 3H linked to resistance and detected seven candidate genes likely involved in this resistance mechanism. These results contribute to a deeper understanding of the genetic factors conferring resistance to leaf stripe disease and offer valuable targets for future breeding efforts in hulless barley. Further research is needed to validate the function of these candidate genes using genetic and molecular biological approaches, such as genetic transformation, genomic editing, and other molecular approaches. To facilitate the use of resistance in Teliteqingke for cultivar development, the identification of linked or functional molecular markers will be essential for molecular marker-assisted selection, enabling the efficient transfer of resistance genes to other hulless barley cultivars. Ultimately, this work provides breeders with important genetic resources to improve disease resistance in hulless barley.

Author Contributions

L.H. conceived the project and designed the experiments; Z.T., S.Z., S.K., and S.F. conducted the experiments; Z.T. and S.Z. wrote the manuscript; Y.Q., Z.T., S.Z., and S.K. analyzed the data and prepared the figures; L.H., and S.K. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript and agreed on and consented to the publication in the journal.

Funding

This work was supported by the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Qinghai, China (2022-ZJ-909) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160647).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kang, S.H.; Zhao, K.; Hou, L. Hulless barley leaf stripe pathogen of genetic diversity and its pathogenic variance analysis. Mol. Plant Breed. 2022, 22, 5725–5735. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.W.; Yang, F.; Yan, J.H.; Hou, L.; Weng, H.; Yao, Q. HGenetic diversity analysis of leaf stripe pathogen in Qinghai Province. Barley Cereal Sci. 2020, 37, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, G.C. Acute hulless barley stripe disease found in Tibet. Plant Prot. 1984, 10, 13–13. [Google Scholar]

- Platenkamp, R. Investigations on the infection pathway of Drechslera graminea in germinating barley. Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University Yearbook. 1976, pp. 49–64.

- Haegi, A.; Bonardi, V.; Dall’Aglio, E.; Glissant, D.; Tumino, G.; Collins, N.; Bulgarelli, D.; Infantino, A.; Stanca., A.; Delledonne, M.; Valè, G. Histological and molecular analysis of Rdg2a barley resistance to leaf stripe. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yao, X.H.; An, L.K.; Yao, Y.H.; Bai, Y.X.; Wu, K.L. Cloning and expression analysis of NBS-LRR gene HvtRGA in hulless barley infected with leaf stripe pathogen. Acta Bot. Sin. 2020, 40, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, S.; Jensen, H.; Jensen, J.; Skou, J.; Jørgensen, J. Localization of a resistance gene and identification of sources of resistance to barley leaf stripe. Plant Breed. 1997, 116, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biselli, C.; Urso, S.; Bernardo, L.; Tondelli, A.; Tacconi, G.; Martino, V.; Valè, G. Identification and mapping of the leaf stripe resistance gene Rdg1a in Hordeum spontaneum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 120, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Collins, N.C.; Tacconi, G.; Dellaglio, E.; Brueggeman, R.; Valè, G. High-resolution genetic mapping of the leaf stripe resistance gene Rdg2a in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, E.J.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Y.X.; Li, B.C.; Ma, X.L.; Wang, H.J. Localization of leaf stripe resistance genes in barley. J. Plant Protect. 2019, 46, 723–729. [Google Scholar]

- Pecchioni, N.; Faccioli, P.; Toubia-Rahme, H.; Valè, G.; Terzi, V. Quantitative resistance to barley leaf stripe (Pyrenophora graminea) is dominated by one major locus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1996, 93, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arru, L.; Niks, R.E.; Lindhout, P.; Valè, G.; Francia, E.; Pecchioni, N. Genomic regions determining resistance to leaf stripe (Pyrenophora graminea) in barley. Genome 2002, 45, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arru, L.; Francia, E.; Pecchioni, N. Isolate-specific QTLs of resistance to leaf stripe (Pyrenophora graminea) in the 'Steptoe' × 'Morex' spring barley cross. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003, 106, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, E.J.; Meng, Y.X.; Li, B.C.; Ma, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.J. Correlation analysis of barley leaf stripe resistance and SSR markers. Plant Protect J. 2019, 46, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Si, E.J.; Lai, Y.; Meng, Y.X.; Li, B.C.; Ma, X.L.; Shang, X.W.; Wang, H.J. Analysis of genetic diversity and correlation between SSR markers and barley leaf stripe resistance. Chin. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2015, 23, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Mapping and candidate gene screening of hulless barley leaf stripe resistance genes based on BSR-seq. Qinghai University, 2021.

- Kang, S.H.; Hou, L. Identification of resistance of hulless barley germplasm resources to leaf stripe disease. Plant Protect. 2024, 50, 286–294. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Zhao, K.; Hou, L. Identification of leaf stripe resistance and molecular detection of resistance genes of hulless barley germplasm accessions. Sichuan Agric. 2024, 42, 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Li, Q.R.; Hou, L.; Bai, Y.X.; Jiang, L.L.; Wei, Y.H.; Guo, Q.Y. Genetic analysis of stripe rust resistance genes in adult stage of two spring wheat germplasm resources. J. Zhejiang Agric. Sci. 2021, 33, 595–601. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, L.; Fang, S.Y.; Kang, S.H. Identification method of liquid infection of leaf barley pathogen: CN114375716A [P]., 2022.

- Boulif, M.; Wilcoxson, R.D. Inheritance of resistance to Pyrenophora graminea in barley. Plant Dis. 1988, 72, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Mo, H.J.; Shi, H.R.; Wang, Z.Q.; Lin, Y.; Wu, F.K.; Zheng, Y.L. Construction of wheat genetic map and QTL analysis of important agronomic traits using SNP gene chip technology. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2016, 22, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.P. Expression profile analysis of resistance to Fusarium of wheat variety Wangshuibai based on gene chip technology and cloning of a non-specific lipid transfer protein gene. Nanjing Agric. Univ., 2012.

- Ma, Q.L.; Chen, L.J.; Yang, L.G.; Xia, X.M.; Ma, F.Q.; Fang, M. Preliminary report on identification of local barley varieties resistant to leaf stripe disease in Gansu. Crop Variety Resour. 1991, 3, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.H.; Chen, Y.X.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, C.G.; Liu, Z.Y. Large-scale mapping of wheat powdery mildew resistance genes by SNP chip and BSA. Acta Cropol. Sin., 2018, 44, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bulli, P.; Zhang, J.L.; Chao, S.M.; Chen, X.M.; Pumphrey, M. Genetic architecture of resistance to stripe rust in a global winter wheat germplasm collection. G3 (Bethesda, Md.) 2016, 6, 2237–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, L.L. Transcriptome analysis of cultivated and wild tomato based on RNA-Seq technique. Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, 2017.

- Zhang, N. Research on differential expression gene detection algorithm based on RNA-Seq data [D]. Dalian Maritime University, 2017.

- Xu, Y.B.; Yang, Q.N.; Zheng, H.J.; Xu, Y.F.; Sang, Z.Q.; Guo, Z.F.; Zhang, J.N. Genotyping by target sequencing (GBTS) and its applications. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2020, 53, 2983–3004. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Ruotti, V.; Stewart, R.M. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Fang, S.Y.; Kang, S.H. Identification method of liquid infection of leaf barley pathogen: CN114375716A [P]., 2022.

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, k.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; Depristo, M.A. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.T.; Demarest, B.L.; Bisgrove, B.W.; Gorsi, B.; Su, Y.C.; Yost, H.J. MMAPPR: mutation mapping analysis pipeline for pooled RNA-seq. Genome Res, 2013, 23, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Yang, R.; Zhao, F.K.; Wang, J.L.; Wang, S.H.; Cheng, J.H. Validation of stem loop qRT-PCR method for tomato miRNA. Mol. Plant Breed. 2015, 13, 1867–1871. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).