Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Characteristics | Glucose isomerization [a,d] | Cetus two steps process [b] | Inulin hydrolysis [c] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of steps | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Conversion (%) | 50 (limited by the equilibrium) [d] |

99 | 99.5 |

| Raw-materials availability | Glucose from the starch of crops, mollases, cellulose, and food processing byproducts [58,59] | genetically modified chicory crop; cultures of Aspergillus sp. | |

| Impurities in the product | yes | traces | negligibles |

| Reaction type | Enzymatic isomerization | Enzymatic oxidation (step 1), followed by enzymatic reduction (step 2) | Enzymatic hydrolysis |

| Enzyme mobility | Immobilized [d] | Free (suspended) | immobilized |

| Enzyme stability, and other additives | Intra-cellular glucose-isomerase (e.g., Streptomyces murinus) of low stability; metal (Al) salts |

Pyranose 2-oxidase (P2Ox) and catalase (step 1); aldose reductase and NAD(P)H (step 2); enzymes are costly |

Inulinase |

| Temperature | 50-60oC | 25-30oC / 25-30oC |

55oC (40-60oC) |

| Reaction time (h) | 7 | 3-20 (step 1); 25 (step 2) |

13 |

| pH | 7-8.5 | 6.5-7(-8.5); 7-8.5 |

5.5 |

| Reaction steps | 1 isomerization |

2 oxidation (step 1), reduction (step 2) |

1 hydrolysis |

| Coenzyme necessary? | No | yes catalase for (step 1) to prevent P2Ox quick inactivation; NAD(P)H for step 2. NAD(P)H is continuously in-situ regenerated |

No |

| Product purification | Difficult [d] | simple (due to high selectivity) | simple (due to high selectivity) |

| Product purity | 2-5% impurities [d] | High (99.9%) |

High (99.9%) |

| Parameter | Nominal initial value | Remarks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Data set # 1 (DS1) |

[S]o = [kDG]o | 35 mM | Other species initial conc. [P]o = 0; [A(+)]o = [NADP(+)]o = 0; [EA]o = 0 |

|||

| [A]o = [NADPH]o | 35 mM | |||||

| [E]o = [ALR]o | 0.0048 U/mL | |||||

|

Data set # 2 (DS2) |

[S]o = [kDG]o | 35 mM | ||||

| [A]o = [NADPH]o | 35 mM | |||||

| [E]o = [ALR]o | 0.00257 U/mL | |||||

|

Data set # 3 (DS3) |

[S]o = [kDG]o | 35 mM | ||||

| [A]o = [NADPH]o | 6 mM | |||||

| [E]o = [ALR]o | 0.0055 U/mL | |||||

|

Data set # 4 (DS4) |

[S]o = [kDG]o | 15 mM | ||||

| [A]o = [NADPH]o | 35 mM | |||||

| [E]o = [ALR]o | 0.006 U/mL | |||||

| Temperature, pH | 25oC, 7 | pH buffer | ||||

| Optimization limits of initial loads | [S]o ∈ [5-100], mM [NADPH]o ∈ [5-80], mM |

[E]o ∈ [0.003-0.1] U/mL [47] [FDH] ∈ [100-2000] (U/L) [12] |

||||

| NADPH regeneration | [HCOO]o = [kDG]o | Similarly to Maria [57]; Slatner et al. [46] | ||||

| [CO2]o = 0; [FDH]o = 1000 U/L (adopted as an average) | [FDH]o should be determined by optimization | |||||

| Reactor volume (L) | 1 | up to 3 L capacity | ||||

| Batch time (tf) (h) | 24 | For all DS1-DS4 | ||||

| Solubility in water | DG (kDG) | 5-7 M | (25-30oC) [73] | |||

| DF | ca. 22.2 M | 25°C pH= 7 [//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fructose] | ||||

| CO2 solubility, [CO2]* | 31.3 (mM) at (25oC) | [74,75] | ||||

| DG (kDG) water solution viscosity | 1-3 cps (for < 0.3 M) 1000 cps (4.5M, 30oC), Vs.- 1094 cps (molasses, 38oC) |

[64,76] | ||||

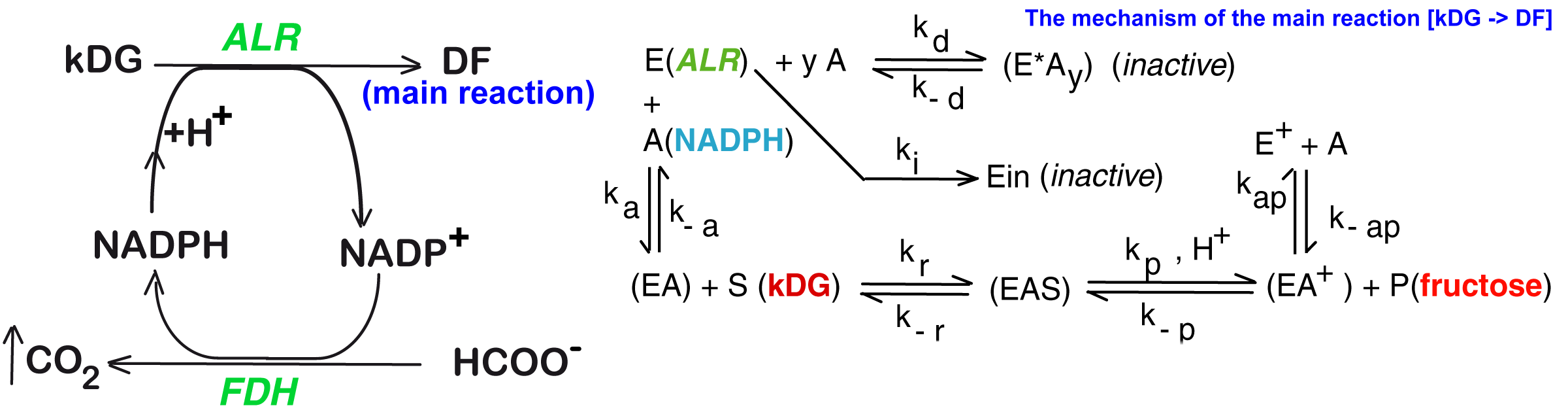

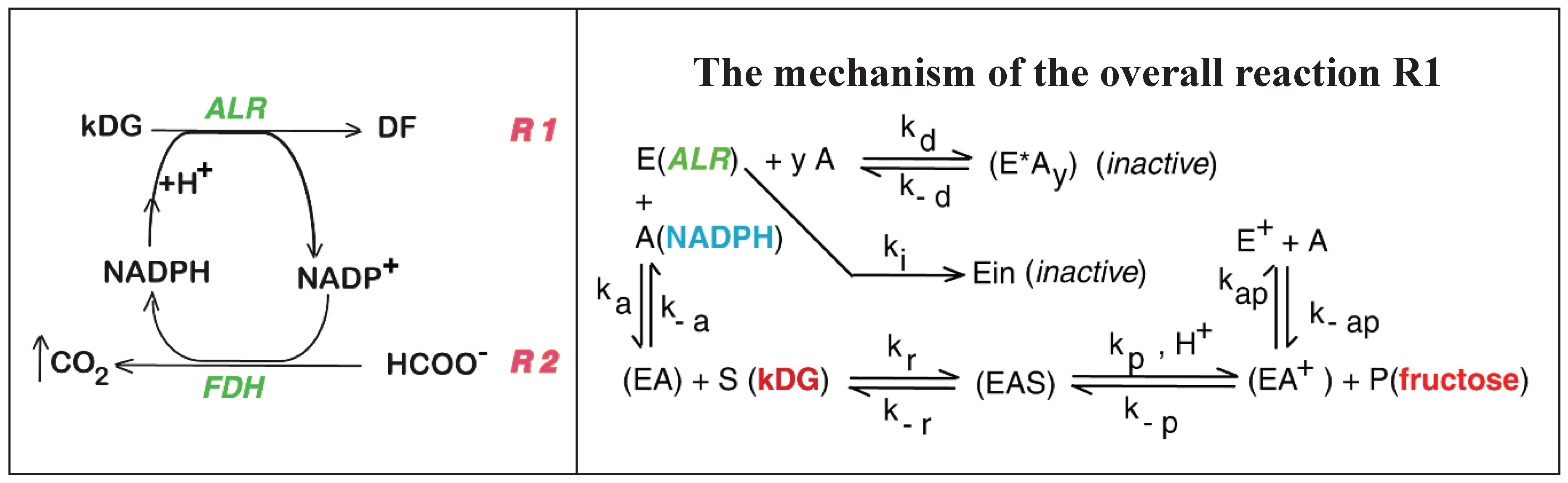

2. The Experimental Enzymatic Reactor

3. Biocatalytic Process Kinetic Model

| The overall reaction R1 of Figure 1 and its attached side-reactions |

|

|

| Rate expressions of the reactions displayed in Figure 1-right, corresponding to the mechanism of the overall reaction R1 |

|

, (successive Bi-Bi mechanism) ; ; ; ; ; |

| Rate constant | Value | Rate constant | Value |

| , mM/min/(U/mL) | 3.9 106 | , 1/(mM min) | 2.07·106 |

| , mM | 65.41 | , 1/min | 858.23 |

| , mM | 1.24 | , mM /(U/mL) | 1.48·104 |

| , mM | 1427 | , 1/min | 7.01·10-2 |

| , mM | 0.886 |

| , (mM/min) |

| kc2 = 0.1387, 1/min/(U/L); KM2 = 8.8047 ×10-2 mM; KHC = 5.0061×10-2 ; KNADP = 90.181 |

4. The BR Enzymatic Reactor Dynamic Model

| Key species mass balances in the BR (corresponding to Equation (1)) | The main experimental conditions of Table 2 |

|---|---|

|

; ; |

“Liquid volume = 1 L Phosphate buffer, pH = 7; 25oC Initial conc. are in the ranges: [kDG] = 15-35 mM [NADPH] = 6-35 mM Initial [ALR] = 2.6-6 U/L [HCOO]o = [kDG]o [63]; [FDH] = 100-2000 U/L ; If [CO2] ≥ [CO2]*, then [CO2] ≈ [CO2]*, and the excess leave the system. FDH inactivation is neglected. Notations: S = substrate (kDG); P = product (fructose); A = NADPH; A(+) = NADP(+); E = ALR The units are in mM, min, and U/L.” |

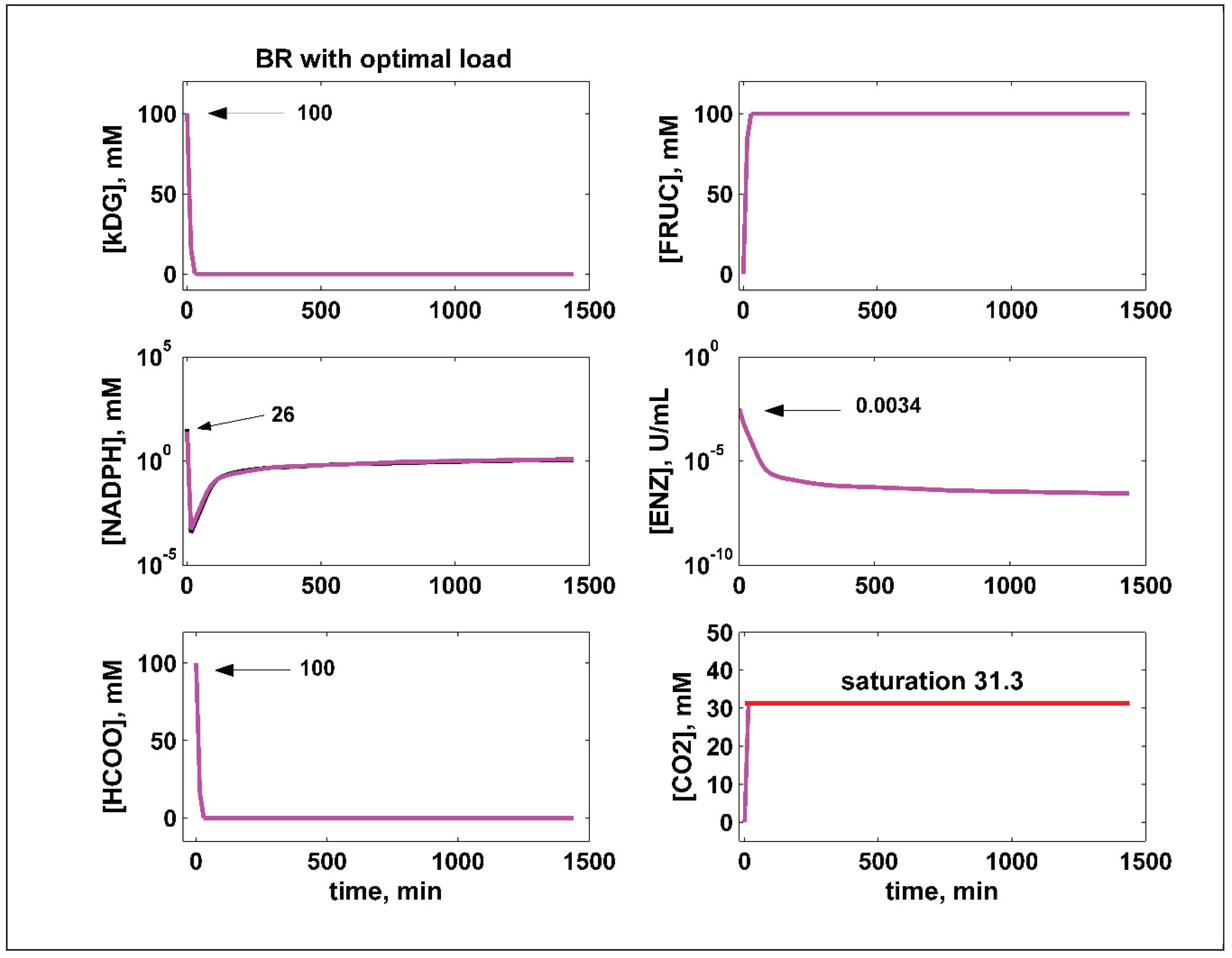

5. BR Simulation and Optimization

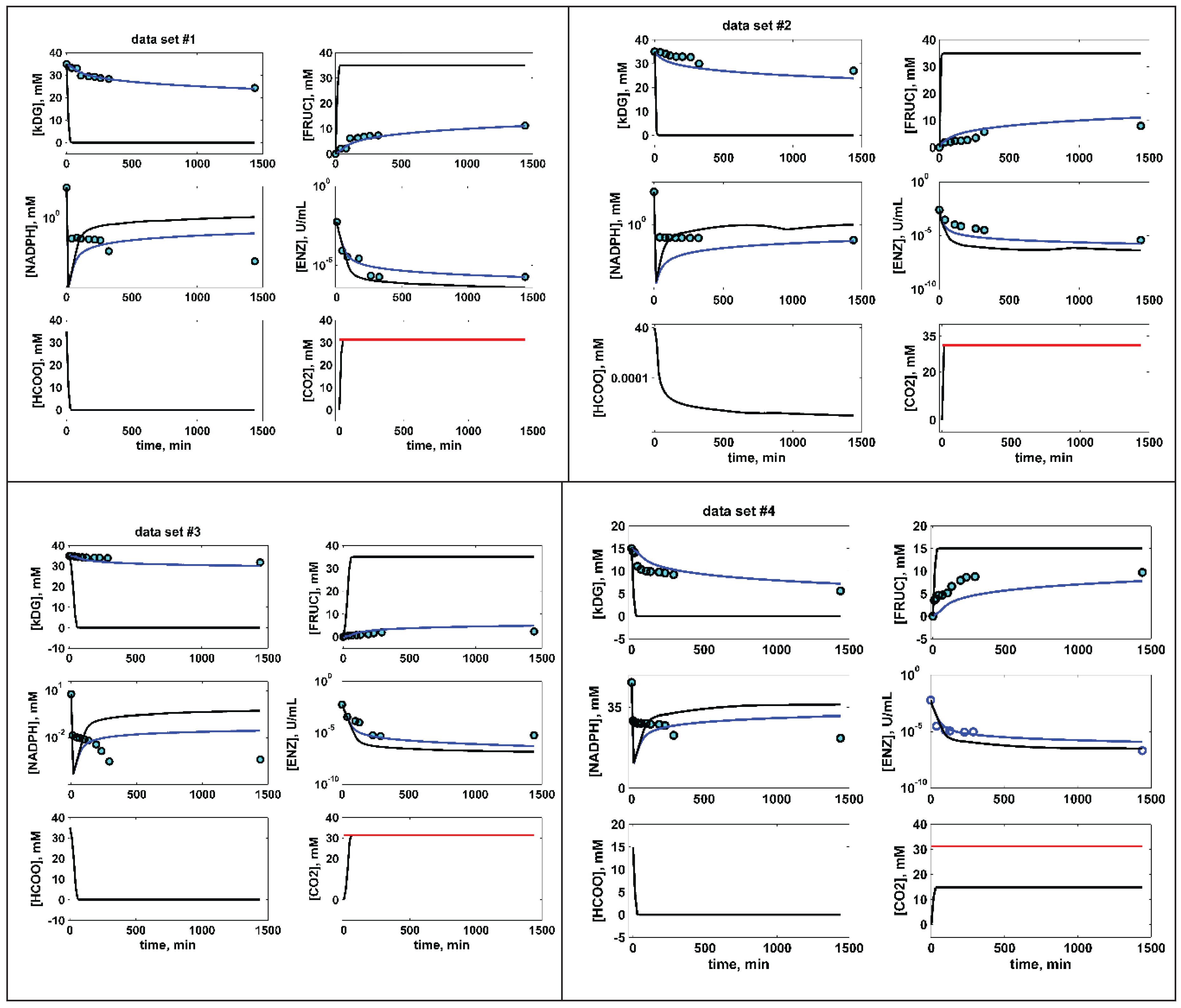

5.1. Nominal BR Simulation, and Control Variables Selection

5.2. Single Objective Function Optimization (NLP) of the BR

5.3. Optimization Problem Constraints

6. Optimization Results and Their Discussion

| Bioreactor operation | Raw material consumption (a,b,c) |

DF prod,mmoles | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kDG,mmoles | NADPH,mmoles | Final NADPH, mmoles | ALR,(U) | FDH,(U) | ||||||||||||||

|

BR Not-optimal experiments [47] |

Without NADPH regeneration, Figure 2 (d) (very poor) |

DS1 | 35 | 35 | 0.18 | 4.8 | - | 11 | ||||||||||

| DS2 | 35 | 35 | 0.18 | 2.57 | - | 11.1 | ||||||||||||

| DS3 | 35 | 6 | 0.03 | 5.5 | - | 4.9 | ||||||||||||

| DS4 | 15 | 35 | 0.29 | 6 | - | 7.8 | ||||||||||||

| With NADPH regeneration, Figure 2 (d) (good) |

DS1 | 35 | 35 | 1.25 | 4.8 | 1000 | 35 | |||||||||||

| DS2 | 35 | 35 | 1.06 | 2.57 | 1000 | 35 | ||||||||||||

| DS3 | 35 | 6 | 0.5 | 5.5 | 1000 | 35 | ||||||||||||

| DS4 | 15 | 35 | 1.19 | 6 | 1000 | 15 | ||||||||||||

|

BR optimal initial load, within limits of Table 2 |

With NADPH regeneration Figure 3 (e,f) (best) |

kDG | 100 | 100 | 26 | 1.17 | 3.38 | 440 | 100 | |||||||||

| NADPH | 26 | |||||||||||||||||

| ALR | 3.38 | |||||||||||||||||

| FDH | 440 | |||||||||||||||||

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

Abbreviations and Notations

| Cj, | - | Species j concentration |

| Kj, kj, y, kc2, KM2 | - | Kinetic model constants |

| k | - | Rate constants vector |

| - | Species j reaction rate | |

| - | Temperature | |

| - | Time | |

| - | Batch time | |

| Ω | - | Optimization objective function |

| [x] | - | Concentration of species ‘x’ |

| Index | ||

| 0,o | - | Initial |

| Abbreviations | ||

| A,A* | - | NADPH, NADP+ |

| ALR | - | Aldose reductase |

| BR | - | Batch reactor |

| DG | - | D-glucose |

| DF | - | D-fructose |

| DS1-DS4 | - | The data sets obtained by Maria and Ene [47] in batch experiments aiming at investigating the kDG conversion to D-fructose |

| “E, ENZ | - | ALR enzyme |

| Ein, E*Ay | - | Inactive forms of the enzyme E |

| FBR | - | Fed-batch reactor |

| FDH | - | Formate dehydrogenase |

| GMO | - | Genetically modified organisms |

| HFCS | - | High fructose-glucose syrup |

| HFS | - | High fructose syrup |

| kDG | - | Keto D-Glucose |

| Max | - | Maximum |

| Min | - | Minimum |

| NADPH | - | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced form |

| NLP | - | Nonlinear programming |

| P | - | Product (D-fructose) |

| P2Ox | - | Pyranose 2-oxidase |

| R1, R2 | - | Main reactions of the 2-nd step of the Cetus process (Figure 1) |

| S | - | Substrate (kDG)” |

References

- Moulijn, J.A.; Makkee, M.; van Diepen, A. Chemical process technology, Wiley: New York, 2001.

- Wang, P. Multi-scale features in recent development of enzymic biocatalyst systems, Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. , 2009, 152, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasic-Racki, D.; Findrik, Z.; Presecki, A.V. , Modelling as a tool of enzyme reaction engineering for enzyme reactor development, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2011, 91, 845-856. 91. [CrossRef]

- Maria, G. , A review of algorithms and trends in kinetic model identification for chemical and biochemical systems, Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q., 2004, 18, 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gernaey, K.V.; Lantz, A.E.; Tufvesson, P.; Woodley, J.M.; Sin, G. , Application of mechanistic models to fermentation and biocatalysis for next-generation processes, Trends in biotechnology, 2010, 28, 346-354. 28. [CrossRef]

- Moser, A. Bioprocess technology - kinetics and reactors, Springer Verlag, Berlin,1988.

- Straathof, A.J.J.; Adlercreutz, P. , Applied biocatalysis, Harwood Academic Publ.: Amsterdam,2005.

- Dutta, R. , Fundamentals of biochemical engineering, Springer: Berlin, 2008.

- Lübbert, A.; Jørgensen, S.B. , Bioreactor performance: a more scientific approach for practice, J. Biotechnol., 2001, 85, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engasser, J.M. , Bioreactor engineering: the design and optimization of reactors with living cells, Chem. Eng. Sci., 1988, 43, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Peptanaru, I.M. Model-based optimization of mannitol production by using a sequence of batch reactors for a coupled bi-enzymatic process – A dynamic approach, Dynamics-Basel, 2021, 1, 134-154. [CrossRef]

- Gijiu, C.L.; Maria, G.; Renea, L. Pareto optimal operating policies of a batch bi-enzymatic reactor for mannitol production, Chemical Engineering and Technology. 2024; 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G. , Enzymatic reactor selection and derivation of the optimal operation policy by using a model-based modular simulation platform, Comput. Chem. Eng. 2012, 36, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G. , Model-based optimization of a fed-batch bioreactor for mAb production using a hybridoma cell culture, Molecules – Organic Chemistry, 2020b, 25, 5648-5674. 25. [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, D.; Srinivasan, B.; Hunkeler, D. , Control and optimization of batch processes, IEEE Control systems magazine, Dec. 26, 2006, 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Primus, C.J.; Bonvin, D.; Ricker, N.L. , Run-to-run optimization via control of generalized constraints, Control Engineering Practice, 2001, 9, 911-919. 9. [CrossRef]

- Dewasme, L.; Amribt, Z.; Santos, L.O.; Hantson, A.L.; Bogaerts, P.; Wouwer, A.V. , Hybridoma cell culture optimization using nonlinear model predictive control, Proc. 12th IFAC symposium on computer applications in biotechnology, Mumbai, India, Dec. 16-18, 2013. Published in: The International Federation of Automatic Control, 2013, 46, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewasme, L.; Cote, F.; Filee, P.; Hantson, A.L.; Wouwer, A.V. , Macroscopic dynamic modeling of sequential batch cultures of hybridoma cells: an experimental validation, Bioengineering (Basel), 2017, 4, 17. 4. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.; Rocha, I.; Pinto, J.P.; Ferreira, E.C.; Rocha, M. , Differential evolution for the offline and online optimization of fed-batch fermentation processes. In: Chakraborty, U.K.(ed.), Advances in differential evolution. Studies in Computational Intelligence, Springer verlag: Berlin, 2008, pp. 299-317.

- Liu, Y.; Gunawan, R. , Bioprocess optimization under uncertainty using ensemble modeling, J. Biotechnol., 2017, 244, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amribt, Z.; Dewasme, L.; Wouwer, A.V.; Bogaerts, P. , Optimization and robustness analysis of hybridoma cell fed-batch cultures using the overflow metabolism model, Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. , 2014, 37, 1637–1652. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppen, D.; Bonvin, D.; Rippin, D.W.T. , Implementation of adaptive optimal operation for a semi-batch reaction system, Comput. Chem. Eng., 1998, 22, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, D. , Optimal operation of batch reactors—a personal view, J. Process Control., 1998, 8, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, I.Y.; Claes, J.E.; November, E.J.; Bastin, G.P.; van Impe, J.F. , Optimal adaptive control of (bio)chemical reactors: past, present and future, J. Process Control., 2004, 14, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, D. , Realtime optimization, MDPI: Basel, 2017.

- Srinivasan, B.; Bonvin, D.; Visser, E.; Palanki, S. , Dynamic optimization of batch processes: II. Role of measurements in handling uncertainty, Comput. Chem. Eng., 2003, 27, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBiasio, D. , Introduction to the control of biological reactors. In: Shuler, M.I. (ed.), Chemical engineering problems in biotechnology, American Institute of Chemical Engineers: New York, 1989, pp. 351-391.

- Martinez, E. , Batch-to-batch optimization of batch processes using the STATSIMPLEX search method, Proc. 2nd Mercosur Congress on Chemical Engineering. Rio de Janeiro, Costa Verde, Brasil, 2005, paper #20.

- Abel, O.; Marquardt, W. , Scenario-integrated on-line optimisation of batch reactors, J. Process Control., 2003, 13, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Weymarn, N. , Process development for mannitol production by lactic acid bacteria, PhD Diss., Helsinki University of Technology, Laboratory of Bioprocess Engineering, 2002, URL: http://lib.tkk.fi/Diss/2002/isbn9512258854/ (last accessing Aug. 07, 2021).

- Song, K.H.; Lee, J.K.; Song, J.Y.; Hong, S.G.; Baek, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Hyun, H.H. Production of mannitol by a novel strain of Candida magnoliae, Biotechnology Letters, 2002, 24, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loesche, W.J.; Kornman, K.S. , Production of mannitol by Streptococcus mutans, Arch. Oral Biol., 1976, 21, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäumchen, C.; Roth, A.H.F.J.; Biedendieck, R.; Malten, M.; Follmann, M.; Sahm, H.; Bringer-Meyer, S.; Jahn, D. , D-Mannitol production by resting state whole cell biotransformation of D-fructose by heterologous mannitol and formate dehydrogenase gene expression in Bacillus megentarium, Biotechnol. J., 2007, 2, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binette, J.C.; Srinivasan, B. , On the use of nonlinear model predictive control without parameter adaptation for batch processes, Processes- Basel, 2016, 4., 27. 4. [CrossRef]

- Franco-Lara, E.; Weuster-Botz, D. , Estimation of optimal feeding strategies for fed-batch bioprocesses, Estimation of optimal feeding strategies for fed-batch bioprocesses, Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng., 2005, 28, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avili, M.G.; Fazaelipoor, M.H.; Jafari, S.A.; Ataei, S.A. , Comparison between batch and fed-batch production of rhamnolipid by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Iranian Journal of Biotechnology, 2012, 10, 263-269. 10.

- Loeblein, C.; Perkins, J.; Srinivasan, B.; Bonvin, D. , Performance analysis of on-line batch optimization systems, Comput. Chem. Eng., 1997, 21, S867–S872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S. , An on-line batch span minimization and quality control strategy for batch and semi-batch processes, Control Eng. Pract., 2001, 9, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Qiu, H. , Process control engineering: a textbook for chemical, mechanical and electrical engineers, Gordon and Breach Science Publ.: Amsterdam, 1993.

- Akinterinwa, O.; Khankal, R.; Cirino, P.C. , Metabolic engineering for bioproduction of sugar alcohols, Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2008, 19, 461–467. 19. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ding, L.; Singleton, M.L.; Idrissi, H.; Hermans, S. E: Synergistic effects altering reaction pathways: The case of glucose hydrogenation over Fe-Ni catalysts, Applied Catalysis B, 2021.

- Liese, A.; Seelbach, K.; Wandrey, C. (Eds), Industrial biotransformations, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2006.

- Myande comp., Fructose syrup production, China. 2024. https://www.myandegroup.com/starch-sugar-technology? 22 March 8242.

- Marianou, A.A.; Michailof, C.M.; Pineda, A.; Iliopoulou, E.F.; Triantafyllidis, K.S.; Lappas, A.A. , Glucose to fructose isomerization in aqueous media over homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, ChemCatChem, 2016, 8, 1100-1110, doi/10.1002/cctc. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hanover, L.M.; White, J.S. Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1993, 58, 724S-732S. [CrossRef]

- [Slatner, M.; Nagl, G.; Haltrich, D.; Kulbe, K.D.; Nidetzky, B. , Enzymatic production of pure D-mannitol at high productivity. Biocatal. Biotransform, 1998, 16, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Ene, M.D. , Modelling enzymatic reduction of 2-keto-D-glucose by suspended aldose reductase, Chemical & Biochemical Engineering Quarterly, 2013, 27, 385–395. , 27,.

- Leitner, C.; Neuhauser, W.; Volc, J.; Kulbe, K.D.; Nidetzky, B.; Haltrich, D. , The Cetus process revisited: A novel enzymatic alternative for the production of aldose-free D-fructose, Biocatal. Biotransform, 1998, 16, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaked, Z.; Wolfe, S. , Stabilization of pyranose 2-oxidase and catalase by chemical modification, Methods Enz. , 1988, 137, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, S.; Rekowski, M.J.; Witte, K.; Heckmann-Pohl, D.M.; Giffhorn, F. , Engineering of pyranose 2-oxidase from Peniophora gigantean towards improved thermostability and catalytic efficiency, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. , 2005, 67, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenault, H.K.; Whitesides, G.M. , Regeneration of nicotinamide cofactors for use in organic synthesis, Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol., 1987, 14, 147–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmentier, S.; Arnaut, F.; Soetaert, W.; Vandamme, E.J. , Enzymatic production of D-mannitol with the Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides mannitol dehydrogenase coupled to a coenzyme regeneration system, Biocatalysis and Biotransformation, 2005, 23, 1-7. 23. [CrossRef]

- Leonida, M.D. , Redox enzymes used in chiral syntheses coupled to coenzyme regeneration, Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2001, 8, 345-369. 8. [CrossRef]

- Bachosz, K.; Zdarta, J.; Bilal, M.; Meyer, A.S.; Jesionowski, T. A: Enzymatic cofactor regeneration systems: A new perspective on efficiency assessment, Science of the total environment, 2023, 868, 161630. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, P. , Cofactor regeneration for sustainable enzymatic biosynthesis, Biotechnology Advances, 2007, 25, 369-384. 25. [CrossRef]

- Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. , New trends in the recycling of NAD(P)H for the design of sustainable asymmetric reductions catalyzed by dehydrogenases, Current Organic Chemistry, 2010, 14, 1000-1021. 14. [CrossRef]

- Maria, G. Model-based optimization of a batch reactor with a coupled bi-enzymatic process for mannitol production, Computers & Chemical Engineering, 2020a, 133, 106628-106635. [CrossRef]

- Kanagasabai, M.; Elango, B.; Balakrishnan, P.; Jayabalan, J. , In: Pandey, R.; Pala-Rosas, I., Contreras, J.L., Eds.; Salmones, J., Ethanol and glycerol chemistry - production, modelling, applications, and technological aspects, IntechOpen: London (UK), 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, M.Y.; Stark, B.C. , Recent trends in bioethanol production from food processing byproducts, Jl. Ind. Microbiol Biotechnol, 2016, 43, 1593–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Xiao, W.; Yao, X. Mechanism of glucose–fructose isomerization over aluminum-based catalysts in methanol media, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2019, 7, 14962-14972. [CrossRef]

- Ricca, E.; Calabro, V.; Curcio, S.; Iorio, G. The state of the art in the production of fructose from inulin enzymatic hydrolysis, Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 2007, 27, 129–145. [CrossRef]

- Leskovac, V.; Trivic, S.; Wohlfahrt, G.; Kandrac, J.; Pericin, D. , Glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger: the mechanism of action with molecular oxygen, quinones, and one-electron acceptors, The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 2005, 37, 731–750. [CrossRef]

- Slatner, M.; Nagl, G.; Haltrich, D.; Kulbe, K.D.; Nidetzky, B. , Enzymatic synthesis of mannitol. Reaction engineering for a recombinant mannitol dehydrogenase, Annals New York Academy of Sciences, 1998b, 864, 450-453. 864. [CrossRef]

- Laos, K.; Harak, M. ; The viscosity of supersaturated aqueous glucose, fructose and glucose-fructose solutions, J. Food Physics, 2014, 27, 27–30, URL: http://www.foodphysics.net/journal/2014/paper_4.pdf , (last accessing 7 July,2025). [Google Scholar]

- Roberfroid, M. , Inulin-type fructans, CRC press: Boca Raton, 2005.

- Rocha, J.R.; Catana, R.; Ferreira, B.S.; Cabral, J.M.S.; Fernandes, P. , Design and characterisation of an enzyme system for inulin hydrolysis, Food Chemistry, 2006, 95, 77–82. 95. [CrossRef]

- Ricca, E.; Calabro, V.; Curcio, S.; Iorio, G. , Fructose production by chicory inulin enzymatic hydrolysis: A kinetic study and reaction mechanism, Process Biochemistry, 2009a, 44, 466–470. 44. [CrossRef]

- Ricca, E.; Calabro, V.; Curcio, S.; Iorio, G. , Optimization of inulin hydrolysis by inulinase accounting for enzyme time- and temperature-dependent deactivation. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 48. [CrossRef]

- Tewari, Y.B.; Goldberg, R.N. , Thermodynamics of the conversion of aqueous glucose to fructose, Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 1985, 11, 17-24. 11. [CrossRef]

- Illanes, A.; Zuniga, M.E.; Contreras, S.; Guerrero, A. , Reactor design for the enzymatic isomerization of glucose to fructose, Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 1992, 7, 199-204. 7. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Hong, J. , Kinetics of glucose isomerization to fructose by immobilized glucose isomerase: anomeric reactivity of D-glucose in kinetic model. Journal of Biotechnology, 2000, 84, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehkordi, A.M.; Safari, I.; Karima, M.M. , Experimental and modeling study of catalytic reaction of glucose isomerization: Kinetics and packed-bed dynamic modelling, AIChE Jl., 2008, 54, 1333-1343. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M. , An introduction to chemistry, Chiral publ., 2013, URL: https://preparatorychemistry.com/Bishop_contact.html (last accessing 7 July, 2025).

- Carroll, J.J.; Mather, A.E. , The system carbon dioxide-water and the Krichevsky-Kasarnovsky equation, J. Solut. Chem., 1992, 21, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Prausnitz, J.M.; Poling, B.E. , The properties of gases and liquids, McGraw-Hill: Boston, 1987.

- Zaykovskaya, A.; Amano, B.; Louhi-Kultanen, M. , Influence of viscosity on variously scaled batch cooling crystallization from aqueous erythritol, glucose, xylitol, and xylose solutions, Cryst. Growth Des., 2024, 24, 2700–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenault, H.K.; Simon, E.S.; Whitesides, G.M. Cofactor regeneration for enzyme-catalysed synthesis, Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews, 2013, 6, 221-270. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.W.; Chen, Q.; Pan, J.; Zheng, G.W.; Xu, J.H. Rational engineering of formate dehydrogenase substrate/cofactor affinity for better performance in NADPH regeneration, Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2020, 192, 530–543. [CrossRef]

- Ansorge-Schumacher, M.B.; Steinsiek, S.; Eberhard, W.; Keramidas, N.; Erkens, K.; Hartmeier, W.; Buechs, J. , Assaying CO2 release for determination of formate dehydrogenase activity in entrapment matrices and aqueous-Organic two-phase systems, Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2006, 95, 199-203, DOI 10. 1002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Saba, T.; Yiu, H.H.P.; Howe, R.F.; Anderson, J.A.; Shi, J. Cofactor NAD(P)H regeneration inspired by heterogeneous pathways, Chem, 2017, 2, 621–654. [CrossRef]

- Brenda. 2025. Enzyme database, URL: www.brenda-enzymes.org, (last accessing March 25, 2025).

- Nasliyan, M.V.; Bereketoglu, S.; Yildirim, O. , Optimization of immobilized aldose reductase isolated from bovine liver, Turk J Pharm Sci. , 2019, 16, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Tosa, T.; Kobayashi, T. (Eds.) , Industrial applications of immobilized catalysts, Marcel Dekkwer: New York,1993.

- Guisan, J.M. (Ed.) , Immobilization of enzymes and cells, Humana Press: Totowa, New Jersey, 2006.

- Maria, G.; Ene, M.D.; Jipa, I. , Modelling enzymatic oxidation of D-glucose with pyranose 2-oxidase in the presence of catalase, Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2012, 74, 209-218. 74. [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Crisan, M. , Operation of a mechanically agitated semi-continuous multi-enzymatic reactor by using the Pareto-optimal multiple front method, Journal of Process Control, 2017, 53, 95-105. 53. [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, J.; Georgakis, C.; Stenger jr., H. G. , Uncertainty issues in the modeling and optimization of batch reactors with tendency models, Chem. Eng. Sci., 1994, 49, 5533–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S. , Engineering optimization—Theory and practice, Wiley: New York, 1993.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).