Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

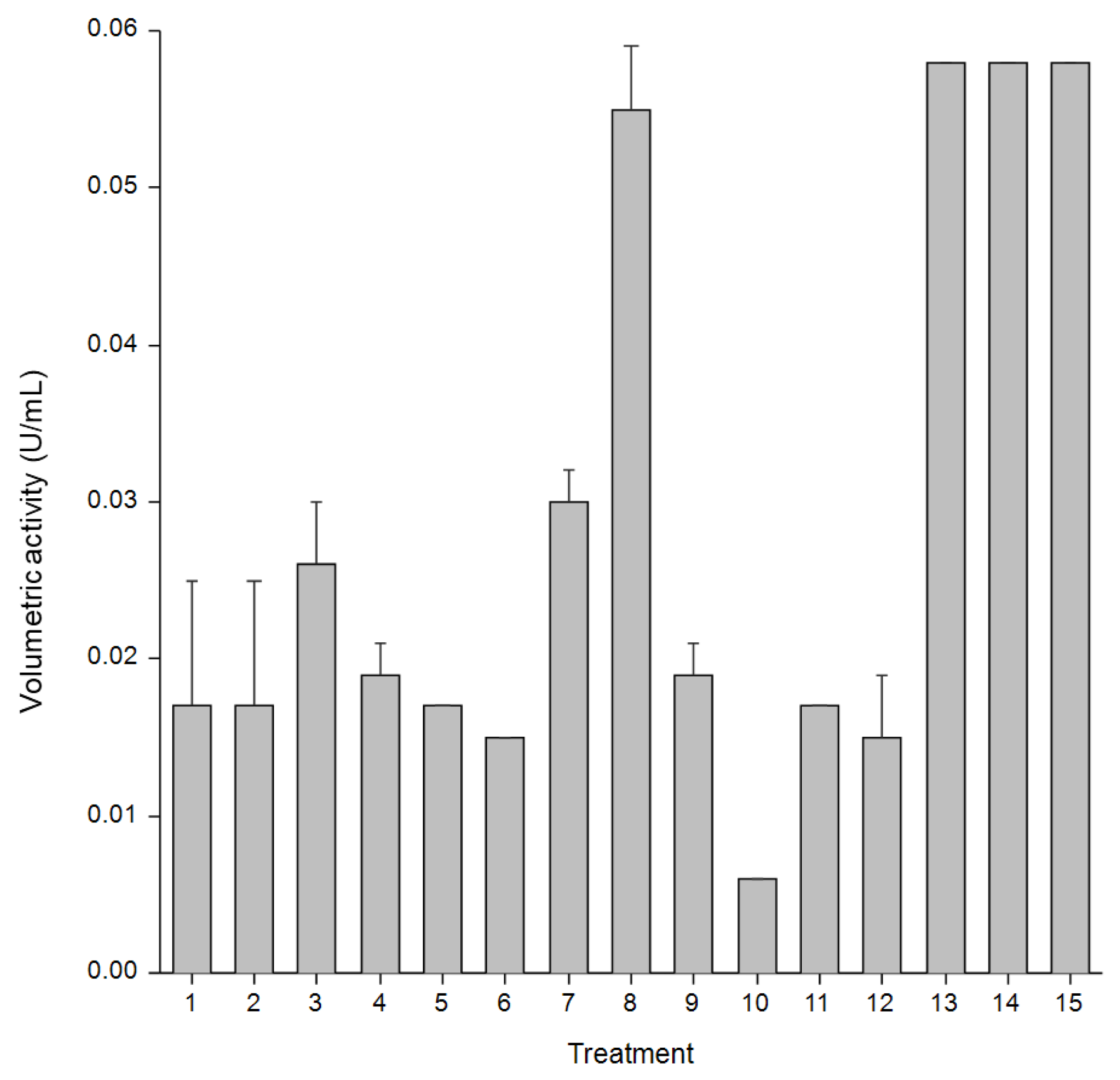

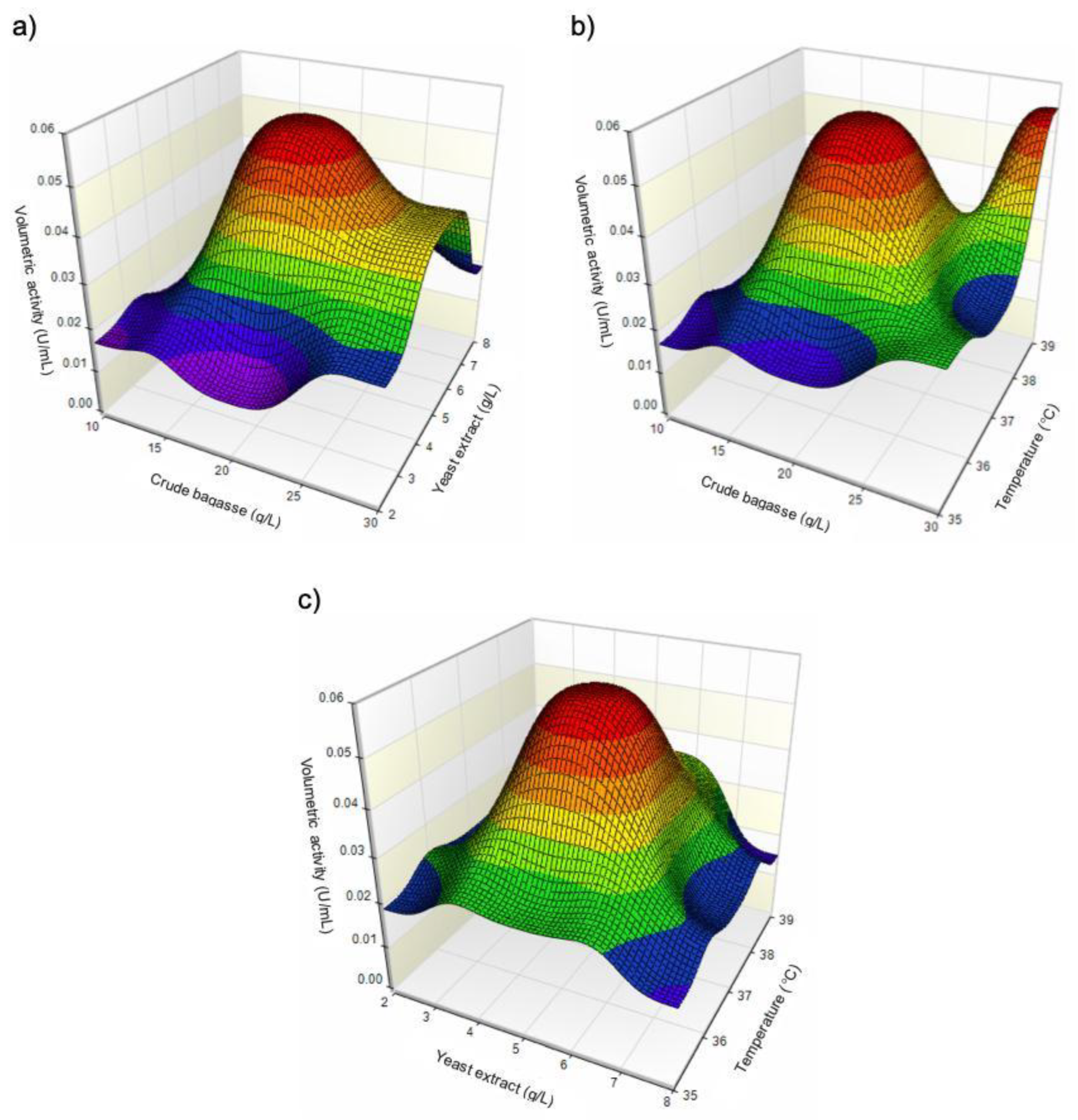

B. siamensis JJC33M produces a b-glucosidase (BglJ33) with transglucosylase activity on cellobiose, and hydrolytic activity on cellulose-derived substrates. B. siamensis JJC33M produces BglJ33 using various agro-industrial residues, untreated sugarcane bagasse enriched with yeast extract as one of the most efficient substrates for enzyme production. Optimization studies have not been carried out for BglJ33 production. Therefore, this study optimized BglJ33 production by B. siamensis JJC33M through the valorization of sugarcane bagasse concentration (10, 20, and 30 g/L), yeast extract concentration (2, 5, and 8 g/L), and temperature (35, 37, and 39°C) using a Box-Behnken experimental design. It was found that increasing the carbon source concentration (from 10 to 30 g/L, with 5 g/L yeast extract at 39°C) increased the volumetric activity on carboxymetilcellulose, from 0.015 to 0.055 U/mL, respectively. Intermediate concentration of yeast extract produced the highest activity, suggesting a balance between nitrogen availability and enzyme expression without causing inhibitory effects. Combination of 20 g/L sugarcane bagasse, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 37 °C resulted in the highest volumetric activity, indicating that this may be the system’s optimal condition. In conclusion, all variables had a significant effect, enhancing process efficiency, while reconsidering sugarcane bagasse to produce high-value-added molecules such as enzymes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Sugarcane Bagasse Treatment

2.2. Characterization of Lignocellulosic Material

2.3. Conservation of B. siamensis JJC33M

2.4. Inoculum and Growth of B. siamensis JJC33M in Raw Sugarcane Bagasse

2.5. Optimization Design for BglJ33 Production Using the Box–Behnken Model

2.6. Determination of Cellulase Volumetric Activity

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Lignocellulosic Material

3.2. Effect of Raw Sugarcane Bagasse Concentration, Yeast Extract, and Temperature on BglJ33 Production

3.3. Optimization of BglJ33 Production

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ungureanu, N.; Vlăduț, V.; Biriș, S. Sustainable Valorization of Waste and By-Products from Sugarcane Processing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021. World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021. Rome: FAO; 2021.

- SADER. Caña de azúcar, una dulce producción. 2025. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/cana-de-azucar-una-dulce-produccion-237168.

- Girio, F.M.; Fonseca, C.; Carvalheiro, F.; Duarte, L.C.; Marques, S.; Bogel-Lukasik, R. Hemicelluloses for fuel ethanol: A review. Bioresour Technol. 2010, 101, 4775–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Sosa, A.; del Moral, S.; Infanzón-Rodriguez, M.I.; Aguilar-Uscanga, M.G. Reappraisal of different agro-industrial waste for the optimization of cellulase production from Aspergillus niger ITV02 in a liquid medium using a Box–Benkhen design. 3 Biotech. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infanzón-Rodríguez, M.I.; del Moral, S.; Gómez-Rodríguez, J.; Faife-Pérez, E.; Aguilar-Uscanga, M.G. Second-Generation Bioethanol Production and Cellulases of Aspergillus niger ITV02 Using Sugarcane Bagasse as Substrate. Bioenergy Res. 2023, 17, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfín-Ruíz, M.E.; Aguilar-Uscanga, M.G.; Gómez-Rodríguez, J. Xylitol Production by Candida tropicalis IEC5-ITV Using Sugarcane Bagasse Acid Pretreated. Sugar Tech. 2023, 25, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Jiang, B.; Chen, H.; Wu, W.; Wu, S.; Jin, Y.; et al. Recent advances in understanding the effects of lignin structural characteristics on enzymatic hydrolysis. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2021, 14, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, O. Assessment of sugarcane industry: Suitability for production, consumption, and utilization. Ann Agrar Sci. 2018, 16, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, E.J.C.; Carvalho, M.; da Silva, D.R.S. Energy, exergy and exergoenvironmental analyses of a sugarcane bagasse power cogeneration system. Energy Convers Manag. 2020, 222, 113232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Salazar, Y.I.; Peña-Montes, C.; del Moral, S.; Aguilar-Uscanga, M.G. Cellulases production from Aspergillus niger-ITV-02 using corn lignocellulosic residues. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química 2022, 21, Alim2772–Alim2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.C.; Nogueira, G.P.; Kendrick, E.; Franco, T.T.; Leak, D.; Dias, M.O.S.; et al. Production of cello-oligosaccharides through the biorefinery concept: A technical-economic and life-cycle assessment. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2021, 15, 1763–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Tian, S.; Du, K.; Xue, X.; Gao, P.; Chen, Z. Preparation and nutritional properties of xylooligosaccharide from agricultural and forestry byproducts: A comprehensive review. Front Nutr. 2022, 13, 977548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, S.; Ramírez-Coutiño, L.P.; García-Gómez, M.J. Aspectos relevantes del uso de enzimas en la industria de los alimentos. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias. Available online: https://www.reibci.org/publicados/2015/mayo/1000102.pdf.

- Montor-Antonio, J.J.; Hernández-Heredia, S.; Ávila-Fernández, Á.; Olvera, C.; Sachman-Ruiz, B.; del Moral, S. Effect of differential processing of the native and recombinant α-amylase from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens JJC33M on specificity and enzyme properties. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, M.; Mittal, A.; Mehta, P.K. Microbial enzymes: Industrial progress in 21st century. Vol. 6, 3 Biotech. Springer Verlag, 2016; 174, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Markets and markets. Enzymes market, 2024. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/enzyme-market-46202020.html.

- Benjamin, S.; Smitha, R.B.; Jisha, V.N.; Pradeep, S.; Sajith, S.; Sreedevi, S.; et al. A monograph on amylases from Bacillus spp. Advances in Bioscience and Biotechnology 2013, 4, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.P.; Lynd, L.R. Toward an aggregated understanding of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose: Noncomplexed cellulase systems. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2004, 88, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Weimer, P.J.; Van Zyl, W.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial Cellulose Utilization: Fundamentals and Biotechnology. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2002, 66, 506–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magwaza, B.; Amobonye, A.; Pillai, S. Microbial β-glucosidases: Recent advances and applications. Biochimie. 2024, 225, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Nasim, F.U.H.; Batool, K.; Bibi, A. Microbial β-Glucosidase: Sources, Production and Applications. J Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017, 5, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, R.R.; Patel, A.K.; Sukumaran, R.K.; Larroche, C.; Pandey, A. Role and significance of beta-glucosidases in the hydrolysis of cellulose for bioethanol production. Bioresour Technol. 2013, 127, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristakopoulus, P.; Goodenough, P.; Kekos, D.; Macris, B.; Claeyssens, M.; Bhat, M. Purification and characterisation of an extracellular beta-glucosidase with transglycosylation and exo-glucosidase activities from Fusarium oxysporum. Eur J Biochem. 1994, 385, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Heredia, S.; Delfín-Ruiz, M.E.; Gerón-Rodríguez, L.; Sachman-Ruíz, B.; Barrera-Figueroa, B.; Panamá, R.W.; et al. Structural analysis of b-glucosidase (BglJ33) from Bacillus siamensis JJC33M, its biological importance and its production in low-cost culture media. In revision. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Montor-Antonio, J.J.; Olvera-Carranza, C.; Reyes-Duarte, D.; Sachman-Ruiz, B.; Ramírez-Coutiño, L.; Del Moral, S. Biochemical characterization of AmiJ33 an amylase from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens isolated of sugarcane soils at the Papaloapan region. Nova Scientia. 2014, 6, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montor-Antonio, J.J.; Sachman-Ruiz, B.; Lozano, L.; del Moral, S. Draft Genome Sequence of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens JJC33M, Isolated from Sugarcane Soils in the Papaloapan Region, Mexico. Genome A. 2015, 3, e01519–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D. Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Laboratory analytical procedure. 2010. TP-510-42618.

- Meddeb-Mouelhi, F.; Moisan, J.; Beauregard, M. A comparison of plate assay methods for detecting extracellular cellulase and xylanase activity. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2014, 66, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alokika, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Singh, B. Cellulosic and hemicellulosic fractions of sugarcane bagasse: Potential, challenges and future perspective. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021, 169, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Velázquez, L.; Salgado-García, S.; Córdova-Sánchez, S.; Valerio-Cárdenas, C.; Ivette Bolio-López, G.; Castañeda-Ceja, R.; Falconi-Calderón, R. Characterization of cellulose and sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) straw from five cultivars grown in the humid tropic of Mexico. Agro Productividad 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatani, S.; Saito, Y.; Alarawi, M.; Gojobori, T.; Mineta, K. Genome sequencing and identification of cellulase genes in Bacillus paralicheniformis strains from the Red Sea. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araujo Ribeiro, G.C.; de Assis, S.A. β-glucosidases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Production, protein precipitation, characterization, and application in the enzymatic hydrolysis of delignified sugarcane bagasse. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2024, 54, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neesa, L.; Islam, R.; Jahan, N.; Zohora, U.S.; Shahedur Rahman, M. Optimization of culture conditions and reaction parameters of β-glucosidase from a new isolate of Bacillus subtilis (B1). Journal of Applied Biotechnology Reports 2020, 7, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, U.U.; Qasim, S.; Zada, N.S.; Ahmad, S.; Shah, A.A.; Badshah, M.; Khan, S. Evaluation of agricultural wastes as a sustainable carbon source for the production of β-glucosidase from Bacillus stercoris, its purification and characterization. Pakistan J Agric Sci 2023, 60, 367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Z.; Yuan, H.; Liu, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, T. Yeast Extract: Characteristics, Production, Applications and Future Perspectives. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Rathour, R.; Jha, S.; Pandey, K.; Srivastava, M.; Thakur, V.K.; Sengar, R.S.; Gupta, V.K.; Mazumder, P.B.; Khan, A.F.; Mishra, P.K. Microbial Beta Glucosidase Enzymes: Recent Advances in Biomass Conversation for Biofuels Application. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 220–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaete, A.V.; Martinazzo, A.P.; de Souza Teodoro, C.E. Cellulase production by Bacillus smithii QT03 using agro-industrial waste as carbon source. Waste Management Bulletin 2025, 3, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettri, D.; Verma, A.K. Statistical optimization of cellulase production from Bacillus sp. YE16 isolated from yak dung of the Sikkim Himalayas for its application in bioethanol production using pretreated sugarcane bagasse. Microbiological Research 2024, 281, 127623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, S.K.; Mahmud, S.; Paul, G.K.; Jabin, T.; Naher, K.; Uddin, M.S.; Saleh, M.A. Fermentation optimization of cellulase production from sugarcane bagasse by Bacillus pseudomycoides and molecular modeling study of cellulase. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2021, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.N.; de Melo, L.F.A.; Luna Finkler, C.L. Optimization of the cultivation conditions of Bacillus licheniformis BCLLNF-01 for cellulase production. Biotechnol 2021, 29, e00599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Xu, Y.; Gruebele, M. Temperature dependence of protein folding kinetics in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109, 17863–17867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Guo, N.; Huang, Y. High temperature delays and low temperature accelerate evolution of a new protein phenotype. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2495–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagar Boopathy, L.R.; Jacob-Tomas, S.; Alecki, C.; Vera, M. Mechanisms tailoring the expression of heat shock proteins to proteostasis challenges. J Biol Chem. 2022, 298, 101796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelain, L.; da Cruz Pradella, J.G.; da Costa, A.C. Mathematical modeling of enzyme production using Trichoderma harzianum P49P11 and sugarcane bagasse as carbon source. Bioresource Technology 2015, 198, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Raw sugarcane bagasse (g/L), X1 |

Yeast extract (g/L), X2 | Temperature (°C), X3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 2 | 37 |

| 2 | 10 | 8 | 37 |

| 3 | 30 | 2 | 37 |

| 4 | 30 | 8 | 37 |

| 5 | 10 | 5 | 35 |

| 6 | 10 | 5 | 39 |

| 7 | 30 | 5 | 35 |

| 8 | 30 | 5 | 39 |

| 9 | 20 | 2 | 35 |

| 10 | 20 | 2 | 39 |

| 11 | 20 | 8 | 35 |

| 12 | 20 | 8 | 39 |

| 13 | 20 | 5 | 37 |

| 14 | 20 | 5 | 37 |

| 15 | 20 | 5 | 37 |

| Source | DG | Sum of squares | Mean square | F - Ratio | P - value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 6 | 0.00425 | 0.00071 | 8.72 | 0.00371 | 86.73 |

| Linear | 3 | 0.00052 | 0.00017 | 2.13 | 0.17429 | 10.60 |

| Quadratic | 3 | 0.00373 | 0.00124 | 15.30 | 0.00112 | 76.12 |

| Total error | 8 | 0.00065 | 8.128E-05 | 13.26 | ||

| Lack of fit | 6 | 0.00065 | 0.00011 | 0.00 | 1.0000 | 13.26 |

| Pure error | 2 | -1.735E-18 | -8.674E-19 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).