1. Introduction

Xylan is a representative part of the lignocellulosic mass in plants, and its degradation involves the synergistic action of different enzymes, with endo-β,4-D-xylanases (E.C.3.2.1.8) and

β-D-xylosidases (E.C. 3.2.1.37) being the most important [

1]. Endo-β-1,4-D-xylanases cleave the xylan main chain, producing xylo-oligosaccharides that can be converted to xylose by β-D-xylosidases [

2]. In many biotechnological and industrial applications, bacterial xylanases have shown better performance than fungal xylanases [

3,

4].The significant differences found were low cellulase activity, low cellulase stability, low cellulase activity in the alkaline range, and high cellulase thermostability, among others [

5,

6]. Moreover, superxylanases are very difficult to produce when all these features are combined, implying that most of the available bacterial xylanases have only one or two of these properties, leading industrial processes to depend on expensive and hazardous chemical processes or strategies for designing or engineering superenzymes [

5,

7].

In baking, xylanases are desirable because they improve dough extensibility and bread volume. Cellulase, on the other hand, can degrade cellulose and structural components associated with the wheat cell wall matrix, compromising the gluten network. This results in loss of gas retention, weakened dough, and, consequently, smaller-volume, worse-textured breads. Therefore, xylanases with low or minimal cellulase activity act selectively on the target polysaccharides (arabinoxylans), optimizing dough rheology without causing undesirable side effects on the flour’s technological quality. In short, this allows for better technological performance, to name a few, volume, texture, and tenderness, without compromising the integrity of the protein network that supports the dough structure[

8].

Xylanases have been widely used in the baking industry for decades. They are employed in baking together with α-amylase, maleate amylase, glucose oxidase and proteases. Xylanases breakdown hemicellulose in wheat flour, helping to redistribute water and make the dough softer and easier to knead. During the bread baking process, they generate greater flexibility and elasticity, allowing the dough to grow. The use of xylanases in baking assures an increase in bread volume, better water absorption and greater resistance to fermentation [

9]. In the manufacture of cookies and crackers, xylanase is recommended to make them creamy and lighter and to improve their texture, palatability, and uniformity [

1].

Xylanases are widely used as processing aids in the grain milling industry to produce flour. In this industry, xylanases are often referred to as hemicellulases or pentosanases. Thus, the term hemicellulase refers to the ability of xylanase to hydrolyze insoluble nonstarch compounds found in flour, while the term pentosanase indicates that the substrate for the xylan enzyme is composed of pentose monomers [

10]. Therefore, xylanases can improve the quality of the baking process and bread dough. In

Bacillus sp., for instance, the

xynHB gene encoding xylanase was cloned and inserted into an antibiotic-free vector and integrated into the yeast genome. The yeast strain A13 overexpressing xylanase was applied in baking and showed a reduction in the time required for kneading and an increase in bread dough height and diameter [

10].

Several species, primarily from the Bacillus genus (B. pumilus, B. circulans, B. amyloliquefaciens, B. stearothermophilus, B. halodurans, B. subtilis), as well as Streptomyces, Geobacillus, Actinomadura, Saccharopolyspora, and Thermotoga, are described as producers of thermostable and hyperthermophilic xylanases [

11]. Other genera, such as Micrococcus, Staphylococcus, Paenibacillus, Cellulomonas, Arthrobacter, and Microbacterium, also contribute to the diversity of these enzymes. In practical applications, the xylanase from Aureobasidium pullulans NRRL Y-2311-1 has shown efficacy in gluten-free cookie formulations, improving the rheological properties of the dough and the softness of the product [

12].

Bacterial xylanases mostly belong to the GH10 and GH11 glycosyl hydrolase families, according to the CAZy (Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database) classification [

13]These enzymes present broad functional and structural diversity. GH10 xylanases are generally enzymes with higher molecular mass, more open active sites and the ability to act on highly substituted xylans, while GH11 xylanases have a more compact structure, high specificity and greater catalytic efficiency on linear xylans, which reflects different adaptive strategies and biotechnological applications [

14,

15,

16]. Recent studies demonstrate that variants of these families exhibit additional properties, such as thermostability, halo-tolerance and resistance to adverse industrial conditions, expanding the potential for use in sectors such as baking, biofuels and functional foods [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The genome of

Caulobacter vibrioides Henrici and Johnson 1935 (

C. crescentus heterotipic) [

18]contains eight genes [

19], which are directly involved in biomass degradation and are therefore relevant for biotechnological applications. Among these genes, only one encodes cellulase (

celA1), two encode enzymes with endoxylanase activity (

xynA1-2), and five encode enzymes with β-xylosidase activity (

xynB-xynB5) [

2]. This bacterium is an interesting source for studying hydrolytic enzymes since they are abundant and recurrent throughout the globe. According to the bacterial diversity metadatabase (BacDive) [

20], there are currently records of 6,141

Caulobacter isolates on the planet, of which 2,002 isolates were identified in water bodies, 1,503 in soil, 969 in plants and 1,667 in different animals, of which 731 in humans [

20,

21].

C. vibrioides has traditionally been considered nonpathogenic and assumed to be nontoxic to humans, making it a promising bioengineering vector for environmental remediation, the food industry, and medical applications [

22]

The

C. vibrioides xynA1 gene [

3]was previously characterized through the overexpression and purification from

E. coli. Different properties was defined, highlighting that the recombinant enzyme XynA1 exhibited an optimal pH equal to 6 and peaked at 50 °C. XynA1 has demonstrated remarkable thermal stability for biotechnological applications, retaining 80% of its activity over a span of 4 hours at 50 °C. Studies using thermostable xylanases with an optimum of 50°C is justified by their greater stability and efficiency under typical baking thermal conditions, ensuring better technological performance and a lower risk of contamination in the process [

23]. Then, the present study introduces a novel process approach in which a new strain was engineered in a way that

xynA1 gene cloned express the XynA1 enzyme under control of a xylose inducible promoter and not by the native promoter. This approach allows that in the controlled conditions of a process only

xynA1 gene cloned would be more expressed by the new strain since its native promoter is not regulated by xylose [

24,

25].

As mentioned before,

C. vibrioides possesses a second xylanase encoding by

xynA2 gene that as XynA1 is characterized as GH10 [

4]Although XynB2 display 50% of activity at temperatures ranging from 40 to 90°C, it has an optimum pH of 8 and less than 35% activity at pH 6. In addition to these biochemical characteristics that do not suit applications in baking processes, the

xynA2 gene is regulated by xylose [

24], which would not allow exclusive control of its expression by xylose addition, as is possible with the

xynA1 gene. Thus, in a context in which both genes,

xynA1 and

xynA2, are expressed, it is clear whether the resulting enzymatic activity comes from the expression of the XynA1 or XynA2 enzyme, simply because they have different biochemical analysis parameters. So, in the present work resulting expressed and secreted

C. vibrioides XynA1 was incorporated into flour and applied throughout baking processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growing Conditions

The strains and plasmids used in the present work are described in

Table 1.

Escherichia coli DH5α and S17 bacterial strains [

26] were used for subcloning and conjugation, respectively. Both strains were grown at 37 °C and maintained at 4 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium [

27].

The E. coli strain containing the pAS22-

xynA1 [

29,

30]construct was grown at 37 °C and maintained at 4 °C in LB media supplemented with chloramphenicol (1 µg/mL). The bacterial strain

C. vibrioides NA1000 was grown at 30 °C and maintained at 4 °C in PYE (Peptone–Yeast Extract medium) media (0.2% bactopeptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 1.7 mM MgSO

4, 0.5 mM CaCl

2). The BS-

xynA1 strain was isolated by conjugation with

E. coli-pAS22-

xynA1 at 30 °C. BS-

xynA1 was maintained at 4 °C in PYE media supplemented with chloramphenicol (1 µg/mL) and nalidixic acid (20 µg/mL).

To induce the expression of

xynA1 gene (XynA1) and other enzymes, the wide type NA1000 strain and

C. vibrioides BS-

xynA1 were cultivated at 30 °C and 120 rpm in minimal medium (M2) (Na

2HPO

4 12 mM, NH

4Cl 9 mM, KH

2PO

4 8 mM, MgSO

4 1 mM, CaCl

2 0.5 mM, FeSO

4 10 mM) [

19] supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) glucose or 0.3% (w/v) xylose or 0.3% (w/v) xylose containing different agro-industrial residues at 0.2% (w/v) like corn straw (CS), corn cob (CC), hemicellulose from corn straw (HPM), wheat straw (WS), polisher residue (PR), vacuum cleaner residue from industry (WF); rice flour (RF); sugarcane bagasse (SB); rice straw (RS) and soybean residue (SR).

2.2. Cloning of the xynA1 Gene in the pAS22 Expression Vector

The DNA fragment corresponding to the

xynA1 gene (CCNA_02894) was isolated from the pJET1.2-

xynA1 construct [

3] as described below. The

xynA1 gene of interest containing 1,158 base pairs present in the pJET1.2-

xynA1 construct, along with the priming methionine and its stop codon, was digested with the restriction enzyme

XhoI (Thermo Fischer Scientific

®). This enzyme cleaves this construct only to promote the linearization of the same construct. Then, a reaction with the enzyme DNA Blunting (Fermentas

®) was carried out to obtain a noncohesive end, which allowed the subcloning process in the pAS22 vector to another noncohesive site in subsequent steps. With the gene still partially attached to the pJET1.2 vector at one end but containing a noncohesive end, it was digested with the restriction enzyme

EcoRI (Thermo Fischer Scientific

®). After digestion, the genetic material was resolved by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis in TAE buffer. The 1,793 bp gel band, corresponding to the

xynA1 gene and an untranslated portion of the pJET1.2 blunt plasmid that remained attached after the stop codon of the

xynA1 gene, was cut from the agarose gel using a scalpel and recovered with a DNA extraction kit (

Pure Link Gel Extraction Kit - Invitrogen

®).

The plasmid used for

xynA1 expression [

3]in

C. vibrioides was pAS22 [

29,

30]This plasmid has a xylose-inducible promoter, which allows for an increase in the expression of the cloned xylanase gene upstream of the promoter. Construction planning was based on experimental evidence that the

C. vibrioides xynA1 gene is not regulated by xylose according to transcriptomic analysis [

24,

25]. Furthermore, the gene was also cloned without the control of its original promoter. The increase in gene expression in this case can easily be accompanied by an increase in xylanase activity, dispensing with evidence for the accumulation of essential protein mass in the case of proteins that do not present measurable enzymatic function. Double plasmid digestion was performed with

EcoRI and

EcoRV restriction enzymes (Thermo Fischer Scientific

®). This linearized vector was ligated to the DNA fragment corresponding to the

xynA1 gene (

EcoRI/Blunt) with the aid of T4 DNA Ligase (BioLabs

®). Subsequently, the pAS22-

xynA1 construct was used for transformation of the

E. coli strain DH5α. Transformants were selected by growth in media supplemented with chloramphenicol (1 μg/mL), a resistance marker of the pAS22 vector. After the transformants were selected, the plasmid material was extracted by mini plasmid preparation, double-digested with the restriction enzymes

EcoRI/

KpnI and resolved by 1% (w/v) TAE agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the gene size.

2.3. Construction of the BS-xynA1 Strain

The pAS22-xynA1 construct was used to transform the E. coli strain S17, which has conjugative functions. Transformants were selected by growth in media supplemented with chloramphenicol (1 μg/mL), the resistance marker of the pAS22 vector. After selection of the transformant, plasmid material was extracted by mini plasmid preparation, double-digested with the restriction enzymes EcoRI/KpnI and resolved by 1% (w/v) TAE agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the recombinant size. E. coli S17 transformant strains containing the pAS22-xynA1 construct were used for the transformation of the C. vibrioides NA1000 strain by conjugation. An aliquot of a fresh E. coli strain containing the pAS22-xynA1 vector was mixed with twice the amount of fresh C. vibrioides cells of the NA1000 strain in solid PYE media. After 48 hours of growth at 30 °C, samples of the bacterial cultures grown on the plate were streaked on a new solid PYE plate containing chloramphenicol (1 μg/mL), the pAS22 vector selection mark and nalidixic acid (20/μg mL), a selection mark of the NA1000 strain and not the E. coli strain, at 30 °C for 48 hours. Isolated colonies grown on these plates were again streaked onto a new PYE plate containing the same amount of chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid. Microscopy analysis was carried out to confirm that only C. vibrioides cells were present in the medium. Aliquots of the BS-xynA1 cells were then named BS-xynA1 and stored at -20 °C and 80 °C for subsequent characterization. In parallel to the construction of the BS-xynA1, a control strain of the NA1000 strain was constructed via conjugation of the empty plasmid pAS22 to generate the strain control WT-pAS22.

2.4. Growth, Xylose Consumption and Xylanase Production

C. vibrioides strains Cc-pAS22 and BS-

xynA1 were preinoculated in 10 mL of liquid PYE medium supplemented with chloramphenicol (1 µg/mL) and nalidixic acid (20 µg/mL) and grown for 12 hours at 30 °C and 120 rpm. When the cells reached the stationary phase of growth, they were diluted (OD

λ600 nm= 0.1) in flask of 250 or 500 mL M2 medium supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) xylose and grown at 30 °C and shaking of 120 rpm. Every two hours of growth, a 2 mL aliquot of the growing culture was collected. From this volume, 1 mL was used to measure spectrophotometer cell growth, 1 mL was centrifuged at 15,000 x g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was reserved for extracellular xylanase activity analysis (optimizing for xylanase 1, pH6 and temperature of 50 °C ) in addition to the dosage of xylose consumption by the Orcinol method for pentoses [

31]. Cell precipitates from centrifugation were frozen for further quantification of intracellular xylanase. The frozen cell pellet was lysed with 350 μL of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, under vigorous vortexing until thawing. The samples were kept on ice, and the overall activity levels of xylanolytic enzymes were determined. The assay and dosages were performed in biological and experimental triplicates, respectively.

2.5. XynA1 Production in Different Agro-Industrial Residues

Preinoculation and inoculation were performed as described in the previous section, but the M2 medium was supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) xylose and 0.2% (w/v) different agro-industrial residues. Corn straw (CS); corn cob (CC); hemicellulose from corn straw (HCS); wheat straw (WS), polisher residue (PR), vacuum cleaner residue from the industry (WF), rice flour (RF), Sugarcane bagasse (SB), rice straw (RS) and soybean residue (SR). All residues were prepared as described previously [

25]. Cultures were incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 120 rpm for 18 hours. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were used to quantify XynA1 activity. The supernatant with the highest XynA1 activity was also characterized by the presence of xylanase 2, cellulase, pectinase, α-L-arabinofuranosidase, β-glucosidase, β-xylosidase and α-amylase. Since the bacterium has two genes for xylanases (

xynA1: CCNA_02894 and

xyn2: CCNA_03137), two enzymes can be expressed under induced conditions. In these experiments, the NA1000 strain containing only the pAS22 (Cc-pAS22) vector was used as a control.

2.6. Dosages of Different Enzymes

Reactions to verify XynA1 and XynA2 activity were performed using 1% (w/v) xylan from beechwood (Sigma

®) as substrate (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 for XynA1 and buffer McIvaine pH 8.0 for XynA2) followed by incubation at 50 and 60 °C, respectively. Reactions to verify cellulase and α-amylase activity were performed using 1% (w/v) carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) as the substrate in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.5) and 1% starch as the substrate (w/v) in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.0), respectively, followed by incubation at 40 °C. Reducing sugars were measured using 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) [

32]. Xylanolytic and cellulolytic activities were defined in U/mL as the amount of enzyme capable of releasing 1 μmol of xylose per mL of solution per min of reaction (U). The enzymatic activities of β-glucosidase, β-xylosidase, and α-L-arabinosidase were determined using ρ-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (ρNPG) and ρ-nitrophenyl-β-D-xylopyranoside (ρNPX) reagents and ρ-nitrophenyl-α-L-arabinofuranoside (ρNPA) (Sigma

®), respectively, according to the adapted methodology described by Justo

et al. [

33], estimating the amount of ρ-nitrophenol (ρNP) released from the respective reagents. The total protein concentration was estimated by the Bradford method [

34], which uses bovine serum albumin (BSA; Bio-Rad

®) as a standard.

2.7. Commercially Available Xylanases Versus Xylanase of BS-xynA1

Xylanolytic activity was also measured in different commercial xylanase mixtures available for application in the bakery industry. Among the variants tested were Spring CA 400 (produced by Granotec from Brail S.A. Nutrition and Biotechnology), Mega Cell 899 and Xylamax 292 (produced by Prozin Industrial and Comercial Ltd.). Enzymatic assays were performed as described in the previous section, with varying incubation temperatures (40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90 and 100 °C) and pH 6. The same procedure was performed for the extracellular crude extract containing the C. vibrioides enzyme XynA1.

2.8. Test for Confirmation of the Absence of Viable Bacteria in Enzyme Extracts

The total enzyme extracts produced were centrifuged at 5,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The centrifuged supernatant containing C. vibrioides XynA1 was sterilized with a 0.22 µm polystyrene vacuum filtration system containing sterile, pyrogen-free low protein binding polyether sulfone (Ciencor®). The complete absence of viable bacteria in the extracellular extracts was tested by plating a 100 µl aliquot of extracellular enzymatic crude extract into each of the three PYE media plates at 30 °C and LB at 37 °C followed by incubation for 48 hours for microbial growth investigation. Aliquots of the filtrates and cell-free XynA1was used for enzymatic assay testing after centrifugation and filtration to confirm the maintenance of xylanase activity.

2.9. mRNA xynA1 Gene Expression Analysis: RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Assay

Analysis of

xynA1 and

xynA2 mRNA expression was performed by RT-qPCR using RNA extracted with Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific®) as indicated by the fabricant. The culture growth overnight in PYE medium at 30 °C and shaking at 120 rpm was diluted in M2 minimal culture medium containing different carbon sources separately: 0.2% (v/v) glucose (non-induced control); 0.3% (v/v) xylose; 0.3% (v/v) xylose + 0.2% (w/v) corncob (CC); 0.3% (v/v) xylose + 0.2% corn straw (CS). Parental and BS-

xynA1 strains were grown to OD

λ 600nm=0.8-1.0 and total RNA was extracted. The primers xynA1-Forw (5’tgcgcgtttttcttggagcg3′) and xynA1-Rev (5′tcccgcgccggcgcggccttcag3′) were used to amplify cDNA from the

xynA1 gene, and the primers

xynA2-Forw (5’atgtcacggctcacccgc3’) and

xynA2-Rev (5’ctaccccgacagcacctc3’) were obtained for amplify the xynA2 gene, both after global transcription with Reverse Transcriptase and random bacterial primers. cDNA was synthesized using 5 μg of RNA, 500 ng of random primers and Superscript II, according to the supplier’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific®). Approximately 200 ng of cDNA was used for quantitative amplification in the presence of 10 ρmoles of each oligonucleotide and 10 μl of Platinum SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems®). The reference gene 16S rRNA constitutively expressed in

C. vibrioides was used to normalize the quantities of target genes (16S-rRNA-Forw: gtacggaagaggtatgtggaac and 16S-rRNA-Rev: tatctaatcctgtttgctcccc), and parental strain grown in glucose 0.2% was used as a calibrator in all tests, emphasizing that this sample was used as a basis for the comparative study of the expression results (ΔΔCT) [

35]. All primers were designed using Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems®). The presence of nonspecific products, formation of dimers between the oligonucleotides were verified by the dissociation curve using the StepOne system software (Applied Biosystems®). The relative gene expression, ΔΔCT, was calculated by the ratio of the CT (cycle threshold) of the sample in the presence of glucose or testes conditions (xylose containing or not agroindustrial residue). The data presented in this work are representative of two independent biological experiments performed in duplicate. The relative gene expression level was calculated from a group of replicates and expressed graphically. The variances of the data obtained were analyzed by the Anova test with a significance level of 99% (P = 0.01).

2.10. Software and IA Tools

Proteins and gene sequences were obtained from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [

36]. Restriction map sequence for cloning was carried out using Restriction-Map algorithms from the Bioinformatics Sequence Manipulation Suite [

37]. Primer design was carried out using Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems®).

Glycoside hydrolases families were found according to Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database (CaZY) classification [

13]. XynA1 structure prediction was performed by alpha-fold generative AI [

38].

The literature search was performed using the ScisSpace (2025) platform, which employs artificial intelligence to identify relevant articles (

https://scispace.com/copilot) through the personal signature of correspondent author: ritabioq@icloud.com profile). The detection of similarities and originality in the present academic text was carried out using Turnitin software (

https://www.turnitin.com) through an institutional signature.

To survey bacterial biodiversity in the environmental context, the BacDive platform (Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase) was used [

20]. “The bibliographic references in this article were managed using the Mendeley Reference Manager (Standard Pack).

The AlveoPC alveograph operates with Chopin’s proprietary software referred to as “Alveograph®” (AlveoPC / Alveograph software) — the Chopin package for acquisition analyzes the parameters (P, L, W, toughness, extensibility, baking strength, etc.) and automatically issues the test certificate. RT-qPCR data was analyzed using StepOne/ StepOnePlus Software v2.3 (Thermo®). Anova and Tukey teste was performed using the software Microsoft Excel -v16.100.4/2025 (Microsoft Corporation®). Figure 2B and the graphical abstract of this work were created using the BioRender tool under the personal profile of the corresponding author (Simão, R. profile). The remaining figures were created using Excel and PowerPoint through an institutional license for the Microsoft Office suite.

2.11. Application of C. vibrioides XynA1 Cell-Free in Bread Formulation

To ensure food safety, the C. vibrioides BS-xynA1 was grown in the absence of chloramphenicol since the cells maintained the pAS22 plasmid and xylanase production under the tested conditions for up to three consecutive days. The extracellular enzymatic extracts enriched with recombinant homologous XynA1 from C. vibrioides were filtered with a PES (polyestersulfone) vacuum filtration system of 0.1 μm and 500 mL capacity (431475-Corning®) and cell-free XynA1 was used in the baking assays. Therefore, it is certain that the final product used in the tests meets food safety standards. The xylanolytic activity of enzymatic extracts used as processing aids in the production of white wheat flour bread has been investigated. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of these enzyme extracts on bread quality using a standardized loaf formulation adhering to the guidelines of Art. 661 of the Argentine Food Code.

The baking trials were meticulously executed in triplicate, employing carefully defined formulations. The core ingredients consisted of white wheat flour (as specified), sugar, salt, fresh yeast (Fleischmann®), vegetable shortening (Coamo®), and water. To explore the impact of enzyme extracts, two additional formulations were developed based on an experimental design in which the enzyme extract concentrations were manipulated. Adjustments in water content were made according to the volume of enzyme solution employed, ensuring consistency with the standard formulation. Refer to

Table 2 for a breakdown of the ingredient quantities in each test formulation. The bread dough was mixed in a 25 kg ALI 25 1G3 bivolt Braesi semi-fast tilting mixer.

The dough preparation procedure included distinct phases, each of which contributed to the final bread characteristics: 1. Mixing (Phase I and Phase II): Initial ingredients, including flour, sugar, salt, and water (also incorporating enzymatic solution for tests T2 and T3), were combined in a trough maintained at a temperature of 4 to 6 °C. This mixture was blended at a constant speed (100 rpm) for 3 min. In Phase II, the blend welcomed vegetable fat and fresh yeast, and mixing was continued at 190 rpm until the desired dough consistency was achieved; 2. Division: The resulting dough was divided into uniform 500 g portions with precision, aided by spatulas and scales; 3. Modeling: The modeling phase involved a single pass through a specialized machine designed to roll, fold, stretch, and thereby homogenize the dough. This three-step process ensured an even dough texture and structure, promoting symmetrical bread formation during fermentation and baking; 4. Fermentation and Growth: The molded dough was shaped into standard forms and positioned within a controlled fermentation chamber set at 28 °C. This allowed for an exact fermentation period of 4 hours, promoting optimal dough development; 5. Baking (Final Step): The fully formed, fermented, and grown dough was placed into a preheated oven set at 180 °C. Baking was carried out for 30 min. After baking, the loaves were allowed to cool to room temperature (25 °C). Bread height measurements were acquired using a measuring tape, and cross-sectional observations were made by halving the loaves to assess alveolar structure. Additionally, photographic documentation facilitated a comprehensive comparison between control loaves and loaves subjected to varying enzyme extract concentrations.

2.10. Alveograph Test: Evaluating Dough Viscoelastic Characteristics

The enzymatic impact on the viscoelastic properties of dough is assessed through alveograph, a technique that emulates dough behavior during fermentation by replicating the formation of air pockets (alveoli) generated by yeast-released carbon dioxide (CO

2). This assessment involves the analysis of various parameters to gauge the viscoelastic traits of different dough samples. Employing the Chopin Alveograph model, AlveoPC, crafted by Chopin Technologies (Villeneuve-la-Garenne, France) and adhering to the International Association for Cereal Science and Technology guidelines (

https://icc.or.at/icc-standards/standards-overview), this test method provides precision to the characterization process.

For the enzyme addition experiment (

Table 3), the enzyme extract volume was determined according to the ratio of enzyme extract per kilogram of flour as utilized in baking test T3. The control run, devoid of enzyme supplementation, served as a baseline. Consistency was maintained in both the control and test groups according to the following parameters: humidity, 14.4%; hydration, 50%; and B concentration, 15% H

2O, in line with the AACC methodology recommendations. The preparation involved diluting sodium chloride in sterile water to afford a 2.5% (w/v) saline solution, which was subsequently combined with the enzyme solution in the enzyme addition test. A total of 250 g of flour was introduced into the mixer at 24 ± 2 °C. The process begins, and within 20 seconds, saline solution is added. The mixing continued for one minute, encompassing the 20 seconds prior to saline addition. Following this, the mixer halts, allowing for the clearing of its sides using a spatula – a one-minute procedure. The mixture was mixed for an additional 7 min, resulting in a total of 8 min.

The mixer is then paused to alter the rotation direction of the paddle, leading to the division of the resulting dough into five uniform portions. These portions were placed within an alveograph rest chamber maintained at 25 ± 0.2 °C. Twenty-eight minutes after the initiation of dough mixing, the first portion was placed at the center of the stationary alveograph plate and coated with Vaseline. The lid is positioned and secured, and the plate undergoes two full turns within 20 seconds. Five seconds later, the lid and ring were removed, and the dough was allowed to inflate until a bubble formed. This sequence is repeated for the other four dough portions.

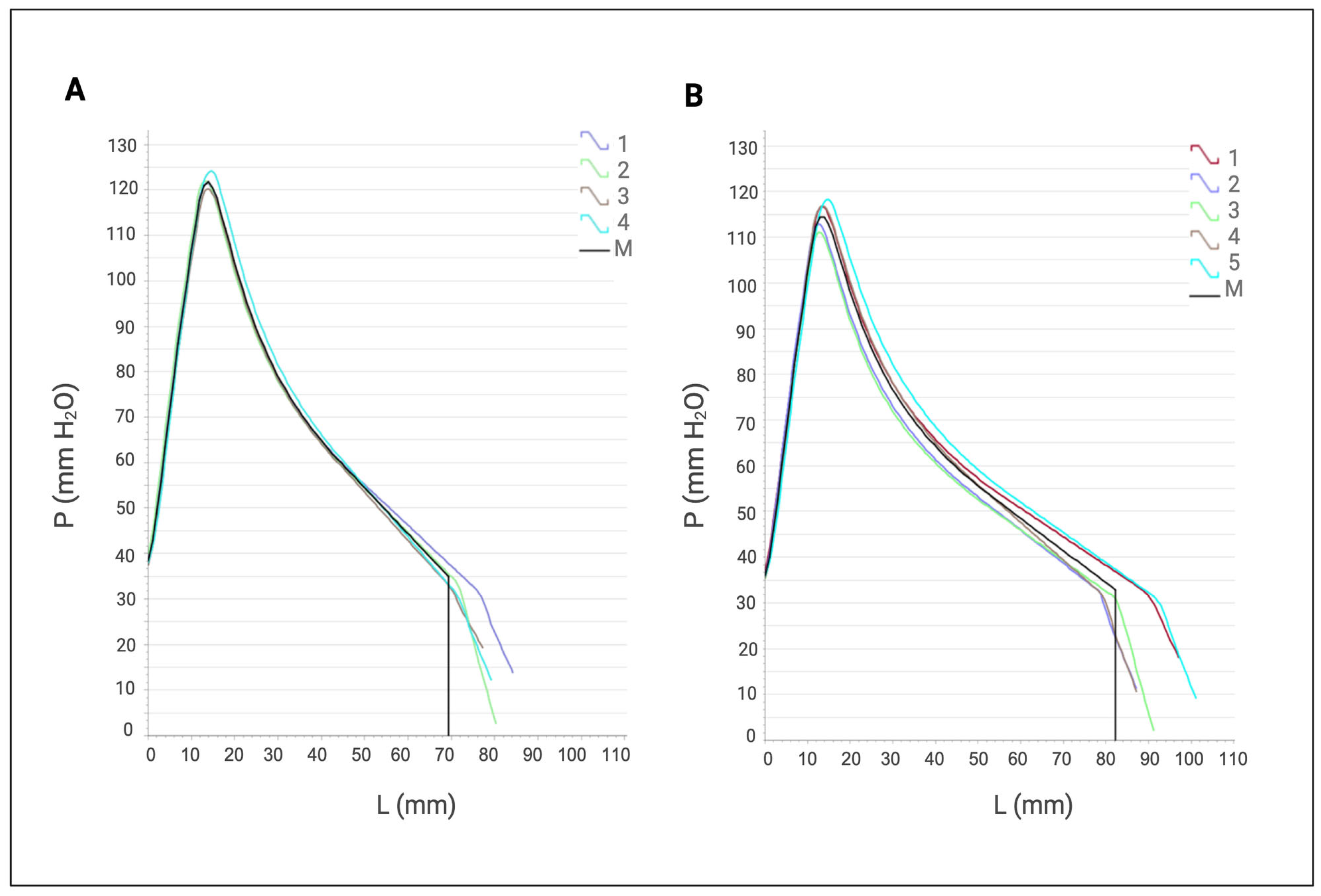

Parameters derived from the alveograph include toughness (P), which represents the peak pressure exerted during mass expansion (measured in millimeters); extensibility (L), which quantifies the length of the curve (measured in millimeters); and mass deformation energy (W), which signifies the mechanical work needed to expand the bubble until rupture, expressed as 10-4 J. The ratio of toughness to extensibility (P/L) offers insight into mass equilibrium, where P signifies the mass’s resistance to deformation, and L indicates mass extensibility.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

For the enzymatic treatment test within the bread formulation that preceding the alveograph analysis, the acquired data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a significance level of 99% (P < 0.01). Subsequently, a Tukey post hoc test was conducted to determine significant differences, maintaining a significance level of 99%.

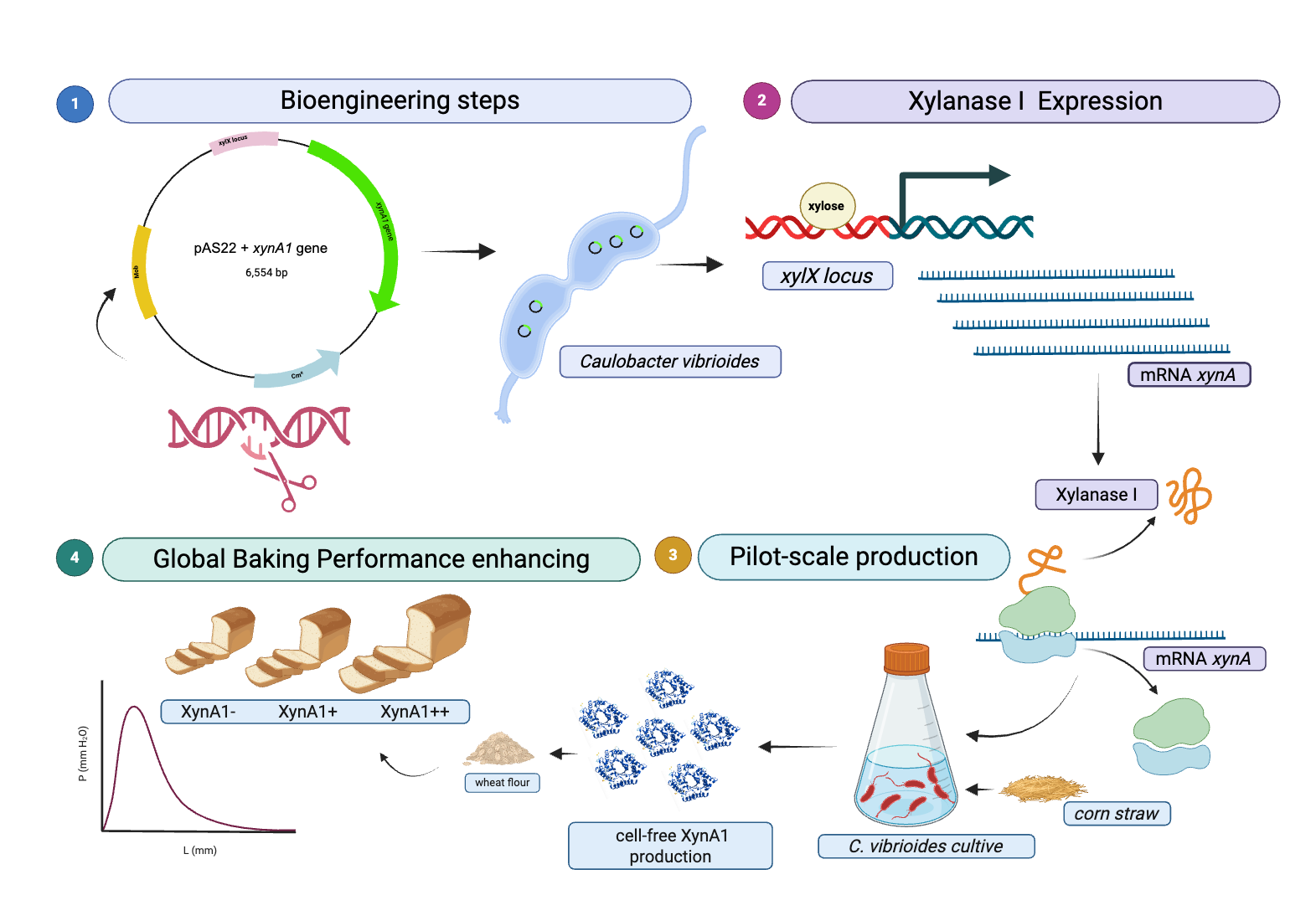

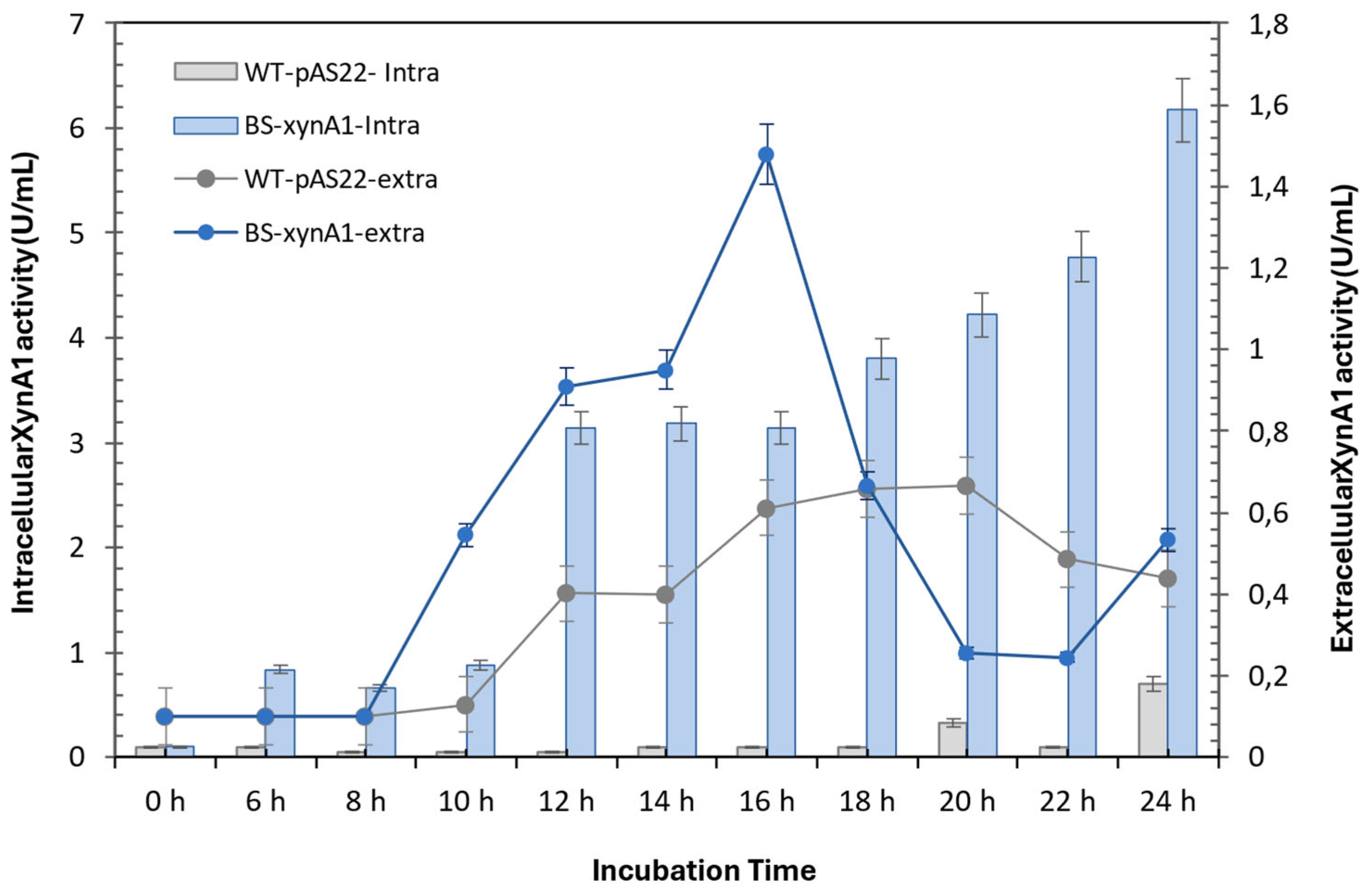

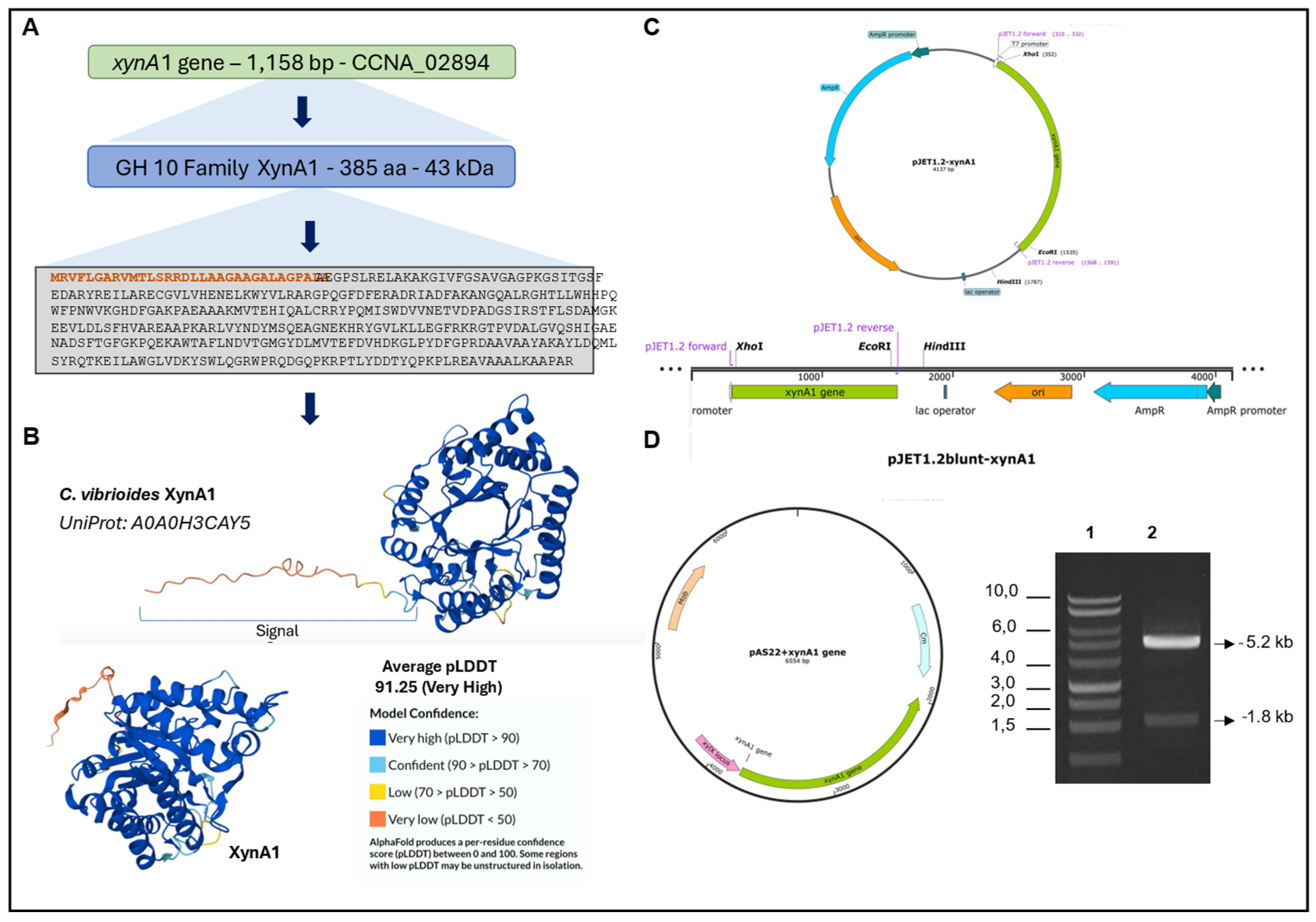

Figure 1.

- Strategies for engineering

C. vibrioides strains that overexpress XynA1 in the strain BS-

xynA1.

(A) The

xynA1 gene (accession number: CCNA_02894) coding a Xylanase that belongs to GH10 family. The amino acid sequence predicted from

xynA1 gene, and the amino terminal signal sequence highlighted in orange.

(B) XynA1 structure prediction using Alpha-Fold Software[

38].

(C) Genetic context of the

xynA1 construct in the pJet1.2-Blunt cloning vector. The pJet1.2-Blunt construct containing the

xynA1 gene was digested with

XhoI and treated to produce blunt-end DNA.

(D) Next, pJet1.2-Blunt-

xynA1 was digested with

EcoRI, and the resulting fragment, containing the complete

xynA1 gene, was subcloned and inserted into the pAS22 vector (

EcoRI/

EcoRV) under the control of a promoter induced by xylose, generating the synthetic strain

BS-xynA1, which expresses XynA1 when 0.3% (w/v) xylose is added. DNA agarose gel electrophoresis on 1% (w/v) TAE gel. 1: Molecular weight marker 1 kb DNA Ladder (Thermo); 2: Construction of pAS22-

xynA1 digested with

EcoRI/

KpnI enzymes.

Figure 1.

- Strategies for engineering

C. vibrioides strains that overexpress XynA1 in the strain BS-

xynA1.

(A) The

xynA1 gene (accession number: CCNA_02894) coding a Xylanase that belongs to GH10 family. The amino acid sequence predicted from

xynA1 gene, and the amino terminal signal sequence highlighted in orange.

(B) XynA1 structure prediction using Alpha-Fold Software[

38].

(C) Genetic context of the

xynA1 construct in the pJet1.2-Blunt cloning vector. The pJet1.2-Blunt construct containing the

xynA1 gene was digested with

XhoI and treated to produce blunt-end DNA.

(D) Next, pJet1.2-Blunt-

xynA1 was digested with

EcoRI, and the resulting fragment, containing the complete

xynA1 gene, was subcloned and inserted into the pAS22 vector (

EcoRI/

EcoRV) under the control of a promoter induced by xylose, generating the synthetic strain

BS-xynA1, which expresses XynA1 when 0.3% (w/v) xylose is added. DNA agarose gel electrophoresis on 1% (w/v) TAE gel. 1: Molecular weight marker 1 kb DNA Ladder (Thermo); 2: Construction of pAS22-

xynA1 digested with

EcoRI/

KpnI enzymes.

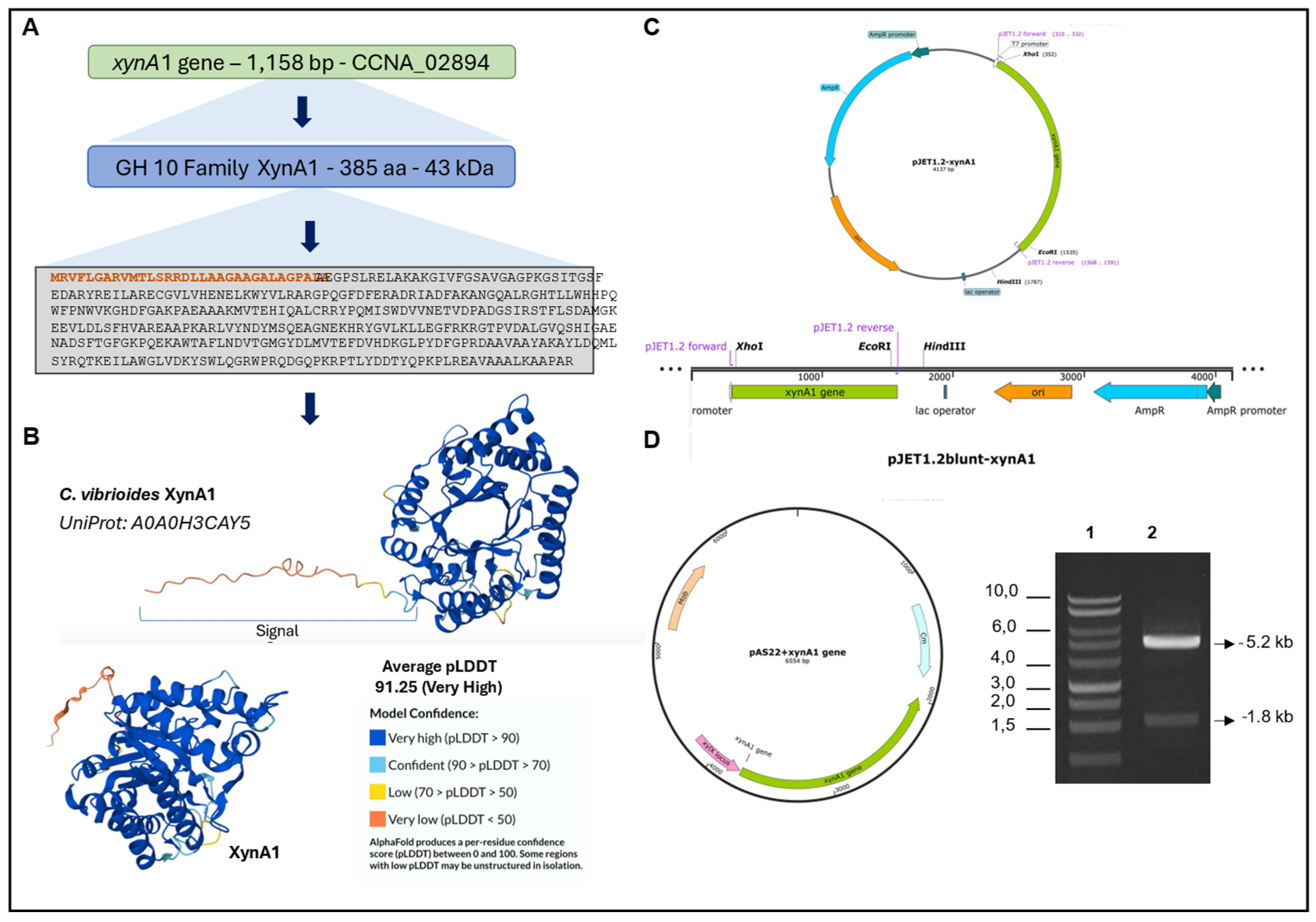

Figure 2.

(A) Xylose consumption and cell growth curves of the wide type of strain (WT-pAS22) and the recombinant strain BS-

xynA1 in M2 media supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) xylose at 30 °C and 120 rpm. Cell growth (gray and blue continuous line) is expressed as the O.D.

λ = 600 nm. The residual xylose content (gray and blue bars) is expressed as a percentage of the total initial sugar content;

(B) Asymmetric life cycle of the bacterium

C. vibrioides. (For more details see the text). (

Figure 2B was created in BioRender. Simão, R. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/9m2r43j).

Figure 2.

(A) Xylose consumption and cell growth curves of the wide type of strain (WT-pAS22) and the recombinant strain BS-

xynA1 in M2 media supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) xylose at 30 °C and 120 rpm. Cell growth (gray and blue continuous line) is expressed as the O.D.

λ = 600 nm. The residual xylose content (gray and blue bars) is expressed as a percentage of the total initial sugar content;

(B) Asymmetric life cycle of the bacterium

C. vibrioides. (For more details see the text). (

Figure 2B was created in BioRender. Simão, R. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/9m2r43j).

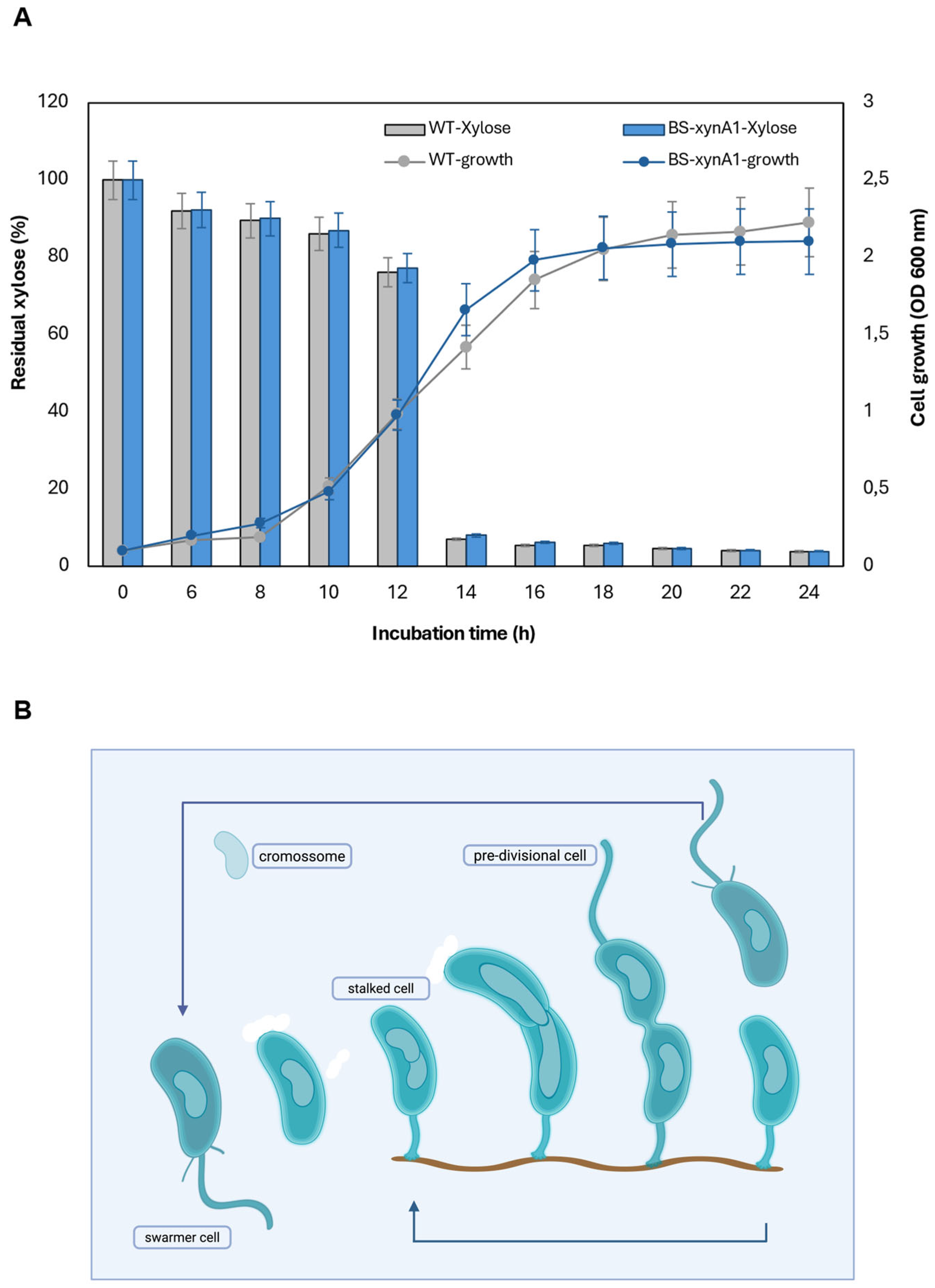

Figure 3.

Intracellular xylanase activity of the wild type of strain (gray continuous line) and BS-xynA1 (blue continuous line). Bacterial cells were grown in M2 media at 30 °C and 120 rpm. Extracellular xylanase activity of the WT (gray bars) and BS-xynA1 (blue bars) strains of C. vibrioides. Bacterial cells were grown in M2 media supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) glucose (WT) and 0.3% (w/v) xylose (BS-xynA1) at 30 °C and 120 rpm for 24 hours. Aliquots of the culture were removed, and xylanolytic activities were measured.

Figure 3.

Intracellular xylanase activity of the wild type of strain (gray continuous line) and BS-xynA1 (blue continuous line). Bacterial cells were grown in M2 media at 30 °C and 120 rpm. Extracellular xylanase activity of the WT (gray bars) and BS-xynA1 (blue bars) strains of C. vibrioides. Bacterial cells were grown in M2 media supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) glucose (WT) and 0.3% (w/v) xylose (BS-xynA1) at 30 °C and 120 rpm for 24 hours. Aliquots of the culture were removed, and xylanolytic activities were measured.

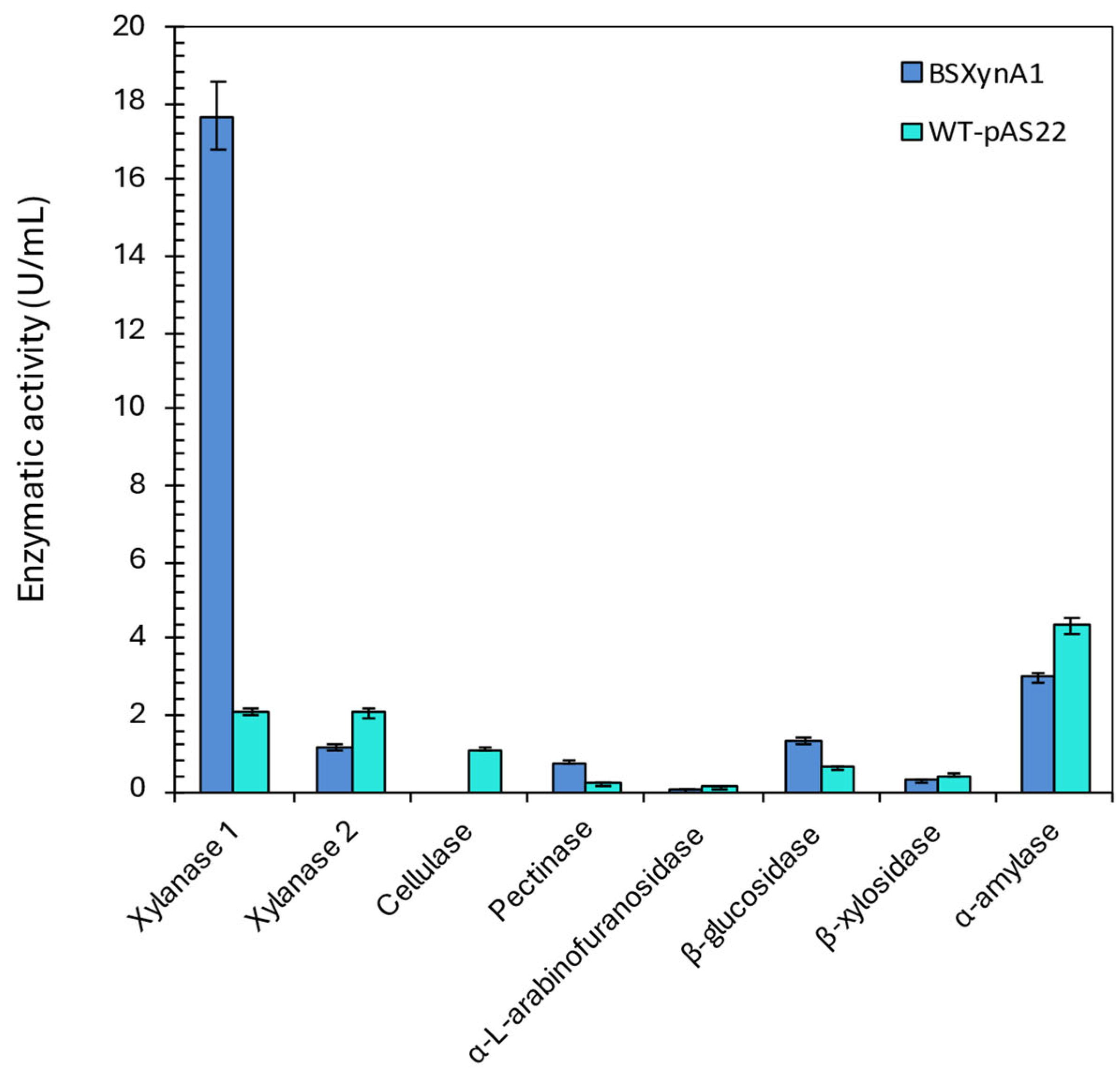

Figure 4.

Enzyme activities produced by different C. vibrioides strains (WT-pAS22 and BS-xynA1) after growth in M2 medium supplemented with 0.3% (v/v) xylose and 0.2% (w/v) corn straw at 30 °C and 120 rpm for 18 hours. [Anova: Degree of freedom: 40; F calculated: 11.70; F critical: 3.12; P value: 5.45 x10-8 (P=0.01)].

Figure 4.

Enzyme activities produced by different C. vibrioides strains (WT-pAS22 and BS-xynA1) after growth in M2 medium supplemented with 0.3% (v/v) xylose and 0.2% (w/v) corn straw at 30 °C and 120 rpm for 18 hours. [Anova: Degree of freedom: 40; F calculated: 11.70; F critical: 3.12; P value: 5.45 x10-8 (P=0.01)].

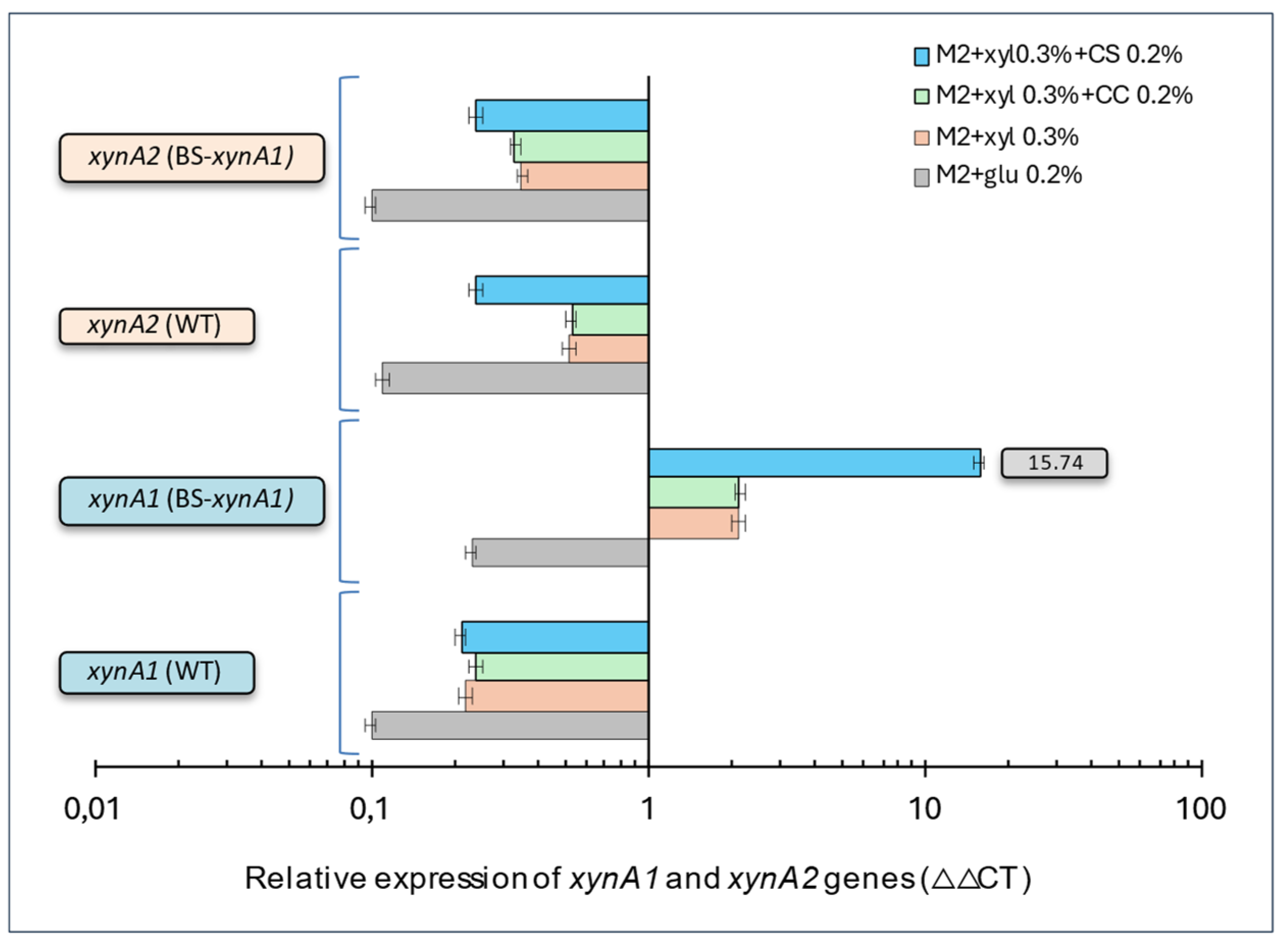

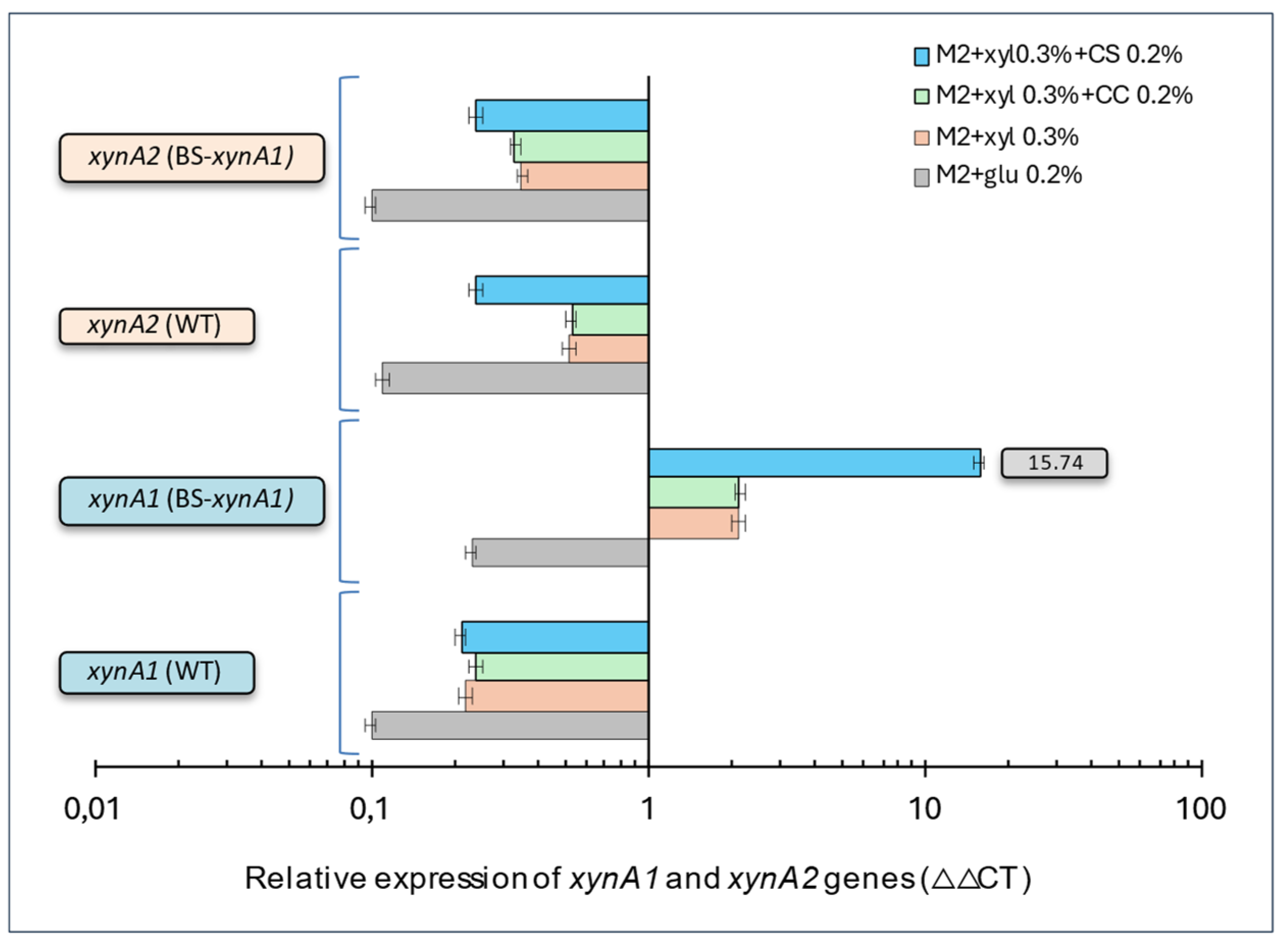

Figure 5.

Relative gene expression of xynA1and xynA2 genes in the C. vibrioides BS-xynA1 strain determined by quantitative real-time PCR (RT‒qPCR). The x-axis shows data on a semi-log scale.This study aimed to understand how nutrient availability and growth conditions affect the expression of the xynA1 and xynA2 genes in C. vibrioides strains. RNA extraction and RT-qPCR protocols followed established procedures. Data normalization was performed using the 16S rRNA gene as an endogenous control, ensuring accuracy and reliability across treatments. Two independent biological experiments with two replicates each were conducted to ensure robustness and consistency. Relative gene expression levels were calculated for treatments under different media conditions. M2 minimum media containing glucose 0.2% (v/v), M2 minimum media containing xylose 0.3% (v/v); M2 minimum media containing xylose 0.3% (v/v) + corn cob (CC) (0.2% w/v); M2 minimum media containing xylose 0.3% (v/v) + corn straw (CS) 0.2% (w/v). [Anova data obtained including xynA1 gene expression profile: degree of freedom: 30; F calculated=11458.62; F critical=3.70 Pvalue 2.98X10-48 (P<0.01)].

Figure 5.

Relative gene expression of xynA1and xynA2 genes in the C. vibrioides BS-xynA1 strain determined by quantitative real-time PCR (RT‒qPCR). The x-axis shows data on a semi-log scale.This study aimed to understand how nutrient availability and growth conditions affect the expression of the xynA1 and xynA2 genes in C. vibrioides strains. RNA extraction and RT-qPCR protocols followed established procedures. Data normalization was performed using the 16S rRNA gene as an endogenous control, ensuring accuracy and reliability across treatments. Two independent biological experiments with two replicates each were conducted to ensure robustness and consistency. Relative gene expression levels were calculated for treatments under different media conditions. M2 minimum media containing glucose 0.2% (v/v), M2 minimum media containing xylose 0.3% (v/v); M2 minimum media containing xylose 0.3% (v/v) + corn cob (CC) (0.2% w/v); M2 minimum media containing xylose 0.3% (v/v) + corn straw (CS) 0.2% (w/v). [Anova data obtained including xynA1 gene expression profile: degree of freedom: 30; F calculated=11458.62; F critical=3.70 Pvalue 2.98X10-48 (P<0.01)].

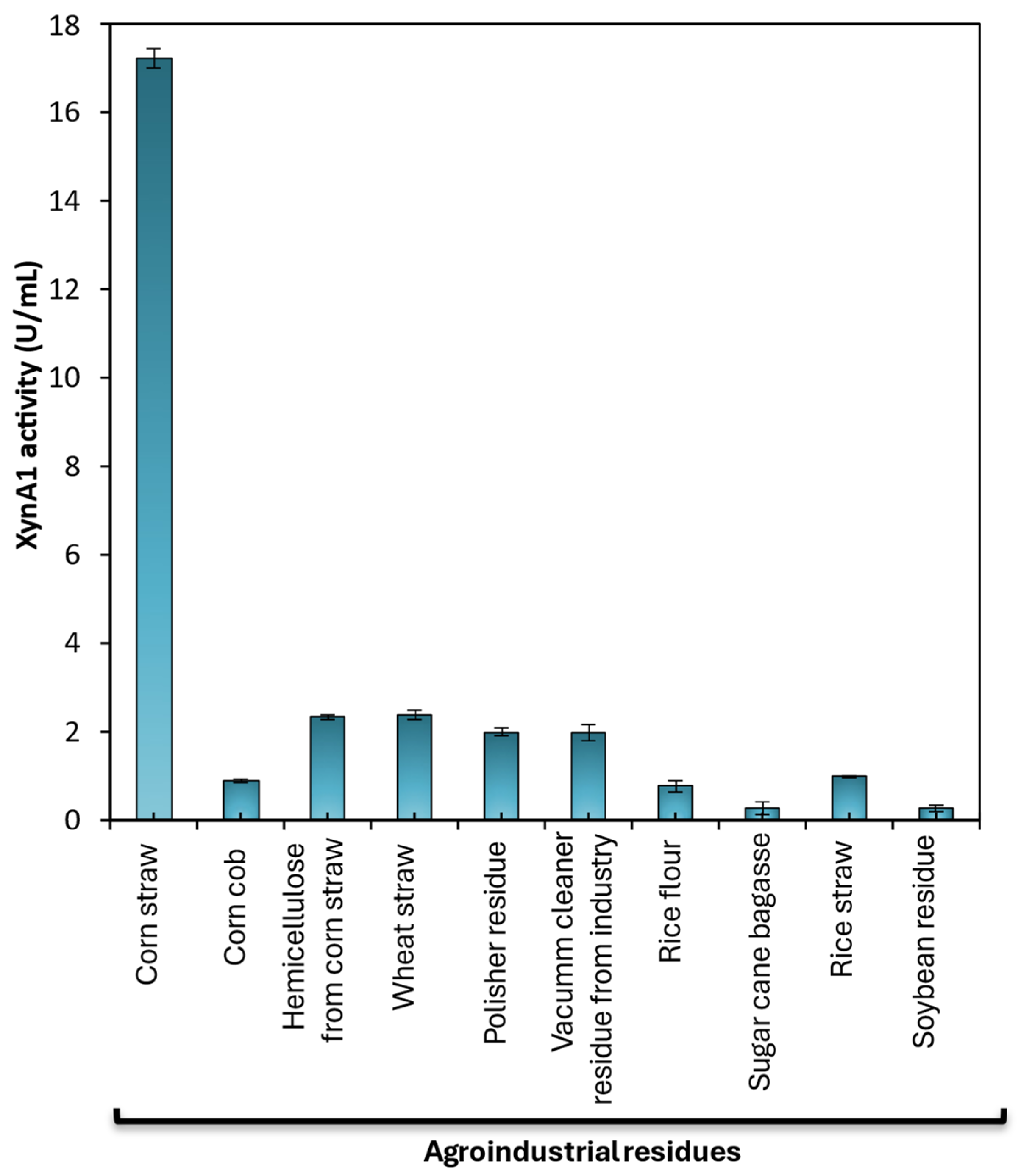

Figure 6.

XynA1production in the presence of different agroindustrial residues. C. vibrioides BS-xynA1 strain cells were grown in minimal M2 medium supplemented with 0.3% (v/v) xylose and supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) agroindustrial residues: corn straw; corn cob; hemicellulose from corn straw; wheat straw; polisher residue, vacuum cleaner residue from industry, rice flour, sugarcane bagasse, rice straw and soybean residue. The inoculum was generated by diluting the cells at the stationary phase to an O.D.λ of 0.1 at 600 nm in the same culture medium containing different carbon sources. Bacterial growth occurred at 30 °C for 18 h with agitation at 120 rpm. [Anova data obtained: degree of freedom=20; F calculated=941.43; F critical =3.36; P value= 2.85 x 10-24 (p<0.01)].

Figure 6.

XynA1production in the presence of different agroindustrial residues. C. vibrioides BS-xynA1 strain cells were grown in minimal M2 medium supplemented with 0.3% (v/v) xylose and supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) agroindustrial residues: corn straw; corn cob; hemicellulose from corn straw; wheat straw; polisher residue, vacuum cleaner residue from industry, rice flour, sugarcane bagasse, rice straw and soybean residue. The inoculum was generated by diluting the cells at the stationary phase to an O.D.λ of 0.1 at 600 nm in the same culture medium containing different carbon sources. Bacterial growth occurred at 30 °C for 18 h with agitation at 120 rpm. [Anova data obtained: degree of freedom=20; F calculated=941.43; F critical =3.36; P value= 2.85 x 10-24 (p<0.01)].

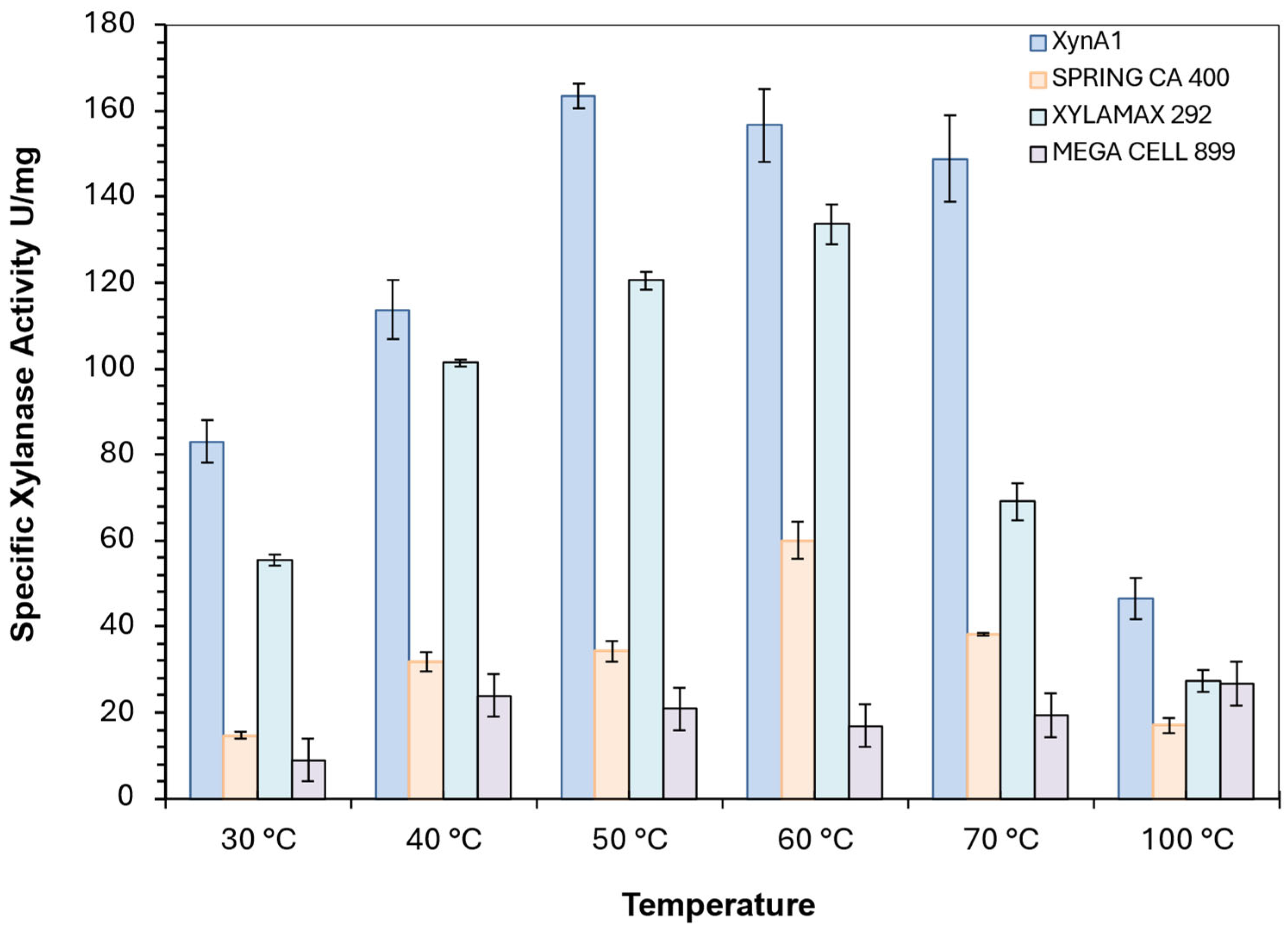

Figure 7.

Comparison between the specific activity (U/mg) of different commercial xylanase, spring CA400 (yellow bars), Xylamax 292 (green bars), Mega Cell 899 (rose bars) and cell-free XynA1 from BS-xynA1 strain (blue bars). [Anova data obtained: degree of freedom: 184; F calculated=14.35; F critical= 2.74; Pvalue=7.88 x10-15 (P<0.01)].

Figure 7.

Comparison between the specific activity (U/mg) of different commercial xylanase, spring CA400 (yellow bars), Xylamax 292 (green bars), Mega Cell 899 (rose bars) and cell-free XynA1 from BS-xynA1 strain (blue bars). [Anova data obtained: degree of freedom: 184; F calculated=14.35; F critical= 2.74; Pvalue=7.88 x10-15 (P<0.01)].

Figure 8.

- Average alveographs provided by the apparatus (alveograph). (A) Control assay. (B) Alveographs obtained after treatment with cell-free XynA1 (30 mL of cell-free XynA1 extract in 250 g of flour). The axis of the abscissa shows the values of elasticity (L) expressed in millimeters (mm). The ordinate axis expresses the toughness (P) values expressed in millimeters of water (mmH2O). The data represent the arithmetic mean of five independent repetitions. The graph is automatically generated by the AlveoPC / Alveograph software/ Chopin Pack.

Figure 8.

- Average alveographs provided by the apparatus (alveograph). (A) Control assay. (B) Alveographs obtained after treatment with cell-free XynA1 (30 mL of cell-free XynA1 extract in 250 g of flour). The axis of the abscissa shows the values of elasticity (L) expressed in millimeters (mm). The ordinate axis expresses the toughness (P) values expressed in millimeters of water (mmH2O). The data represent the arithmetic mean of five independent repetitions. The graph is automatically generated by the AlveoPC / Alveograph software/ Chopin Pack.

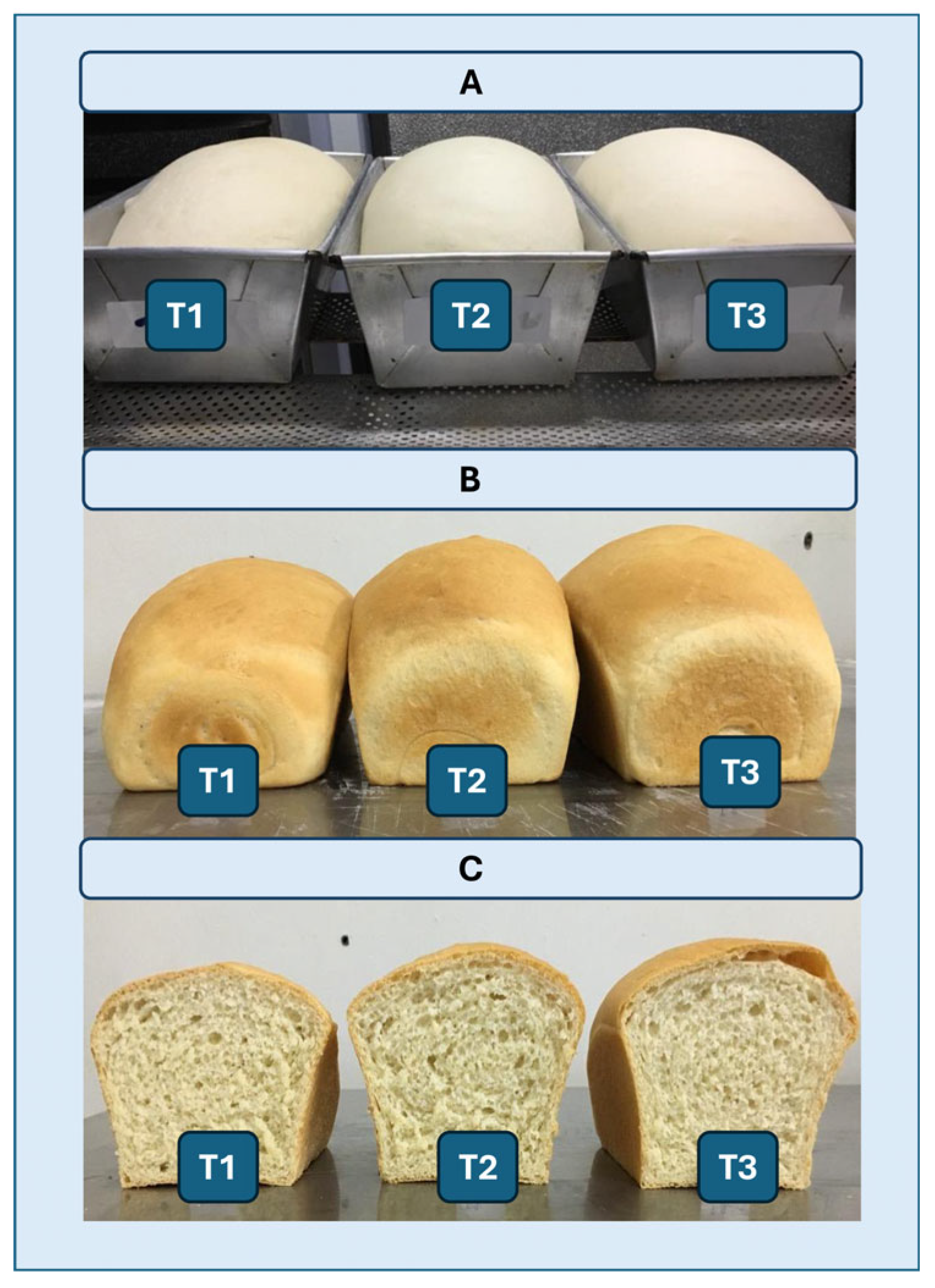

Figure 9.

(A) Representative images of breads after fermentation. (B, C) Images of breads after baking. (B) Whole breads; (C) Breads cut exactly in half. (T1) Control without the addition of the enzyme extract. (T2) Addition of 60 mL of enzyme extract to 1 kg of flour. (T3) A total of 120 mL of enzymatic extract containing cell-free XynA1 (specific activity = 278.64 U/mg) was added to 1 kg of flour.

Figure 9.

(A) Representative images of breads after fermentation. (B, C) Images of breads after baking. (B) Whole breads; (C) Breads cut exactly in half. (T1) Control without the addition of the enzyme extract. (T2) Addition of 60 mL of enzyme extract to 1 kg of flour. (T3) A total of 120 mL of enzymatic extract containing cell-free XynA1 (specific activity = 278.64 U/mg) was added to 1 kg of flour.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the present report.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the present report.

| Strains/Plasmids |

Genotype/Description |

Source/Reference |

| E. coli |

|

|

| DH5α

|

Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 phoA sup144 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 (ɸ80 lacZDM15).

|

Invitrogen®. |

| S17 |

M294::RP4-2 (Tc::Mu) (Km::Tn7)

|

[26] |

| DH5α-pAS22-xynA1

|

E. coli DH5α carrying pAS22-xynA1.

|

This study |

| S17-pAS22-xynA1

|

E. coli S17 carrying pAS22-xynA1

|

This study |

| DH5α-pAS22 |

E. coli DH5α carrying pAS22 |

This study |

| S17-pAS22 |

E. coli S17 carrying pAS22 |

This study |

| C. vibrioides |

|

|

| NA1000 |

Holdfast mutant derivative

of wild-type strain CB15 |

[28] |

| BS-xynA1 |

NA1000 carrying pAS22-xynA1

|

This study |

| WT-pAS22 |

NA1000 carrying pAS22 |

This study |

| Plasmid |

|

|

| pAS22 |

Vector for expression of genes in Caulobacter from the PxylX promoter, ori T, CmR

|

[29] |

| pAS22-xynA1

|

pAS22 containing the xynA1 gene under the control of PxylX promoter |

This study |

Table 2.

Test formulations used in the application of xylanase in bread dough preparation.

Table 2.

Test formulations used in the application of xylanase in bread dough preparation.

| Components |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

| Flour |

1000 g |

1000 g |

1000 g |

| Salt |

20 g |

20 g |

20 g |

| Sugar |

60 g |

60 g |

60 g |

| Vegetable fat |

40 g |

40 g |

40 g |

| Yeast |

20 g |

20 g |

20 g |

| Water |

500 mL |

440 mL |

380 mL |

| Cell-free XynA1 * |

- |

60 mL |

120mL |

Table 3.

Components used in the preparation of bread dough that was subjected to tests using alveograph.

Table 3.

Components used in the preparation of bread dough that was subjected to tests using alveograph.

| Components |

XynA1−

|

XynA1+*

|

| Flour |

250 g |

250 g |

| Water |

127.7 mL |

97.7 mL |

| Sodium Chloride |

3,192.5 g |

3,192.5 g |

| Cell-free XynA1* |

no addition |

30 mL |

Table 4.

Parameters checked on breads and statistical analysis of data obtained in the absence and presence of cell-free XynA1 (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

Table 4.

Parameters checked on breads and statistical analysis of data obtained in the absence and presence of cell-free XynA1 (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

| |

Parameters |

XynA1-

(T1) |

XynA1+

(T2) |

XynA1++

(T3) |

|

| |

Kneading time to get the veil point (min) |

11 |

10 |

10 |

|

| |

Height of bread after fermentation (cm) |

7.9 ± 0.05 |

8.6 ± 0.04 |

9.3 ± 0.05 |

|

| |

Height of bread after baking (cm) |

8.8 ± 0.07 |

9.8 ± 0.08 |

10.4 ± 0.07 |

|

| Anova |

Source of Variation |

dF |

F |

P-value* |

Fc |

| |

Between group |

1 |

980.14 |

2.05 x 10-35

|

7.15 |

| |

Inside group |

52 |

|

|

|

| Tukey Test |

Between groups |

Ma

XynA1-

(T1) |

Ma

XynA1+

(T2) |

Ma

XynA1++

(T3) |

LSD |

| |

Kneading /Fermentation |

3.1 |

1.4 |

0.7 |

1.007995 |

| |

Fermentation/baking |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.007995 |

| |

Kneading /baking |

2.2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

1.007995 |

Table 5.

– Results obtained with alveograph before and after treatment with cell-free-XynA1. The mean data are automatically provided by the alveograph platform and are shown in columns 2 and 3. Anova was performed using data obtained from alveograph and post hoc Tukey test was carried out for compare changes between groups.

Table 5.

– Results obtained with alveograph before and after treatment with cell-free-XynA1. The mean data are automatically provided by the alveograph platform and are shown in columns 2 and 3. Anova was performed using data obtained from alveograph and post hoc Tukey test was carried out for compare changes between groups.

| Parameters |

|

|

Anova |

F |

P value*

|

Fc |

Tukey |

LSD |

| XynA1 |

- |

+ |

dF=117 |

269,38

|

3,6784x10-79

|

2,34

|

Ma |

|

| P (mm H2O) |

134 |

126 |

|

|

|

|

8 |

6,56447705

|

| L (mm) |

69 |

82 |

|

|

|

|

13 |

6,56447705

|

| W (J) |

326 x 10-4

|

353 x 10-4

|

|

|

|

|

27 |

6,56447705

|

| P/L |

1.94 |

1.54 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| eI |

53.6 % |

56.4 % |

|

|

|

|

|

|