1. Introduction

Pectin is a very abundant polysaccharide in nature. The backbone of this this polysaccharide was composed by polygalacturonic acid with different degrees of methyl esterification, acetylation and other modifications. Pectin was widely present in plant cell walls and has important influence on the structural stability of cells. It has significant effects on the processing of beverages such as fruit juices, fruit wines, feeds, and degumming of papermaking, etc [

1]. Pectinase can degrade the long chain of pectin, which is of great significance for food and feed, textile, papermaking, and natural product extraction [

1,

2]. Pectinase with preferential in alkaline environment could be an ideal biocatalyzer to substitute the chemical agency in a wide range of industrial fields in which heavy alkaline was needed to remove the pectin. Adding alkaline pectinase in the papermaking process can improve the pulp effect and reduce the cost of post-bleaching [

3,

4]. Compared with alkali scouring and degumming, biological refining has the advantages of environment-friendly, protecting the fiber, increasing the refining efficiency, and decreasing the energy consumption. And now, enzyme-mediated bio-degumming has becoming a trend in paper industry [

5,

6].

Presently, the alkaline pectinases have been isolated from the fungi such as

Aspergillus luchuensis [

7],

Fusarium decemcellulare [

8],

Sporotrichum thermophile [

9], and some bacteria [

10]. Strains from

Bacillus such as

Bacillus tequilensis [

11],

Bacullus subtilis [

12,

13], and

Bacillus pumilus [

14] were still the main microorganism resources, and the alkaline pectinase genes mining from other bacteria is few mined.

Paenibacillus borealis, in which the nominated species was originally isolated from spruce forest humus in Finland [

15], was a precious but still not be mined resources for industrial enzymes. In order to enrich the alkaline pectinase resources, improving its heterologous expression level in

Pichia pastoris, and facilitated its industrial bioapplication, in this study, a putative pectinase from

Paenibacillus borealis strain was cloned, expressed and enzymatic characterized. The method of improving the gene dosage by constructing the tandem gene expression cassettes were used to improve its expression level, and facilitate its bioapplication in related industrial fields.

2. Results

2.1. Phylogeny Analysis, Structure Alignment and Conservation Analysis of PelA from Paenibacillus and Related Genus.

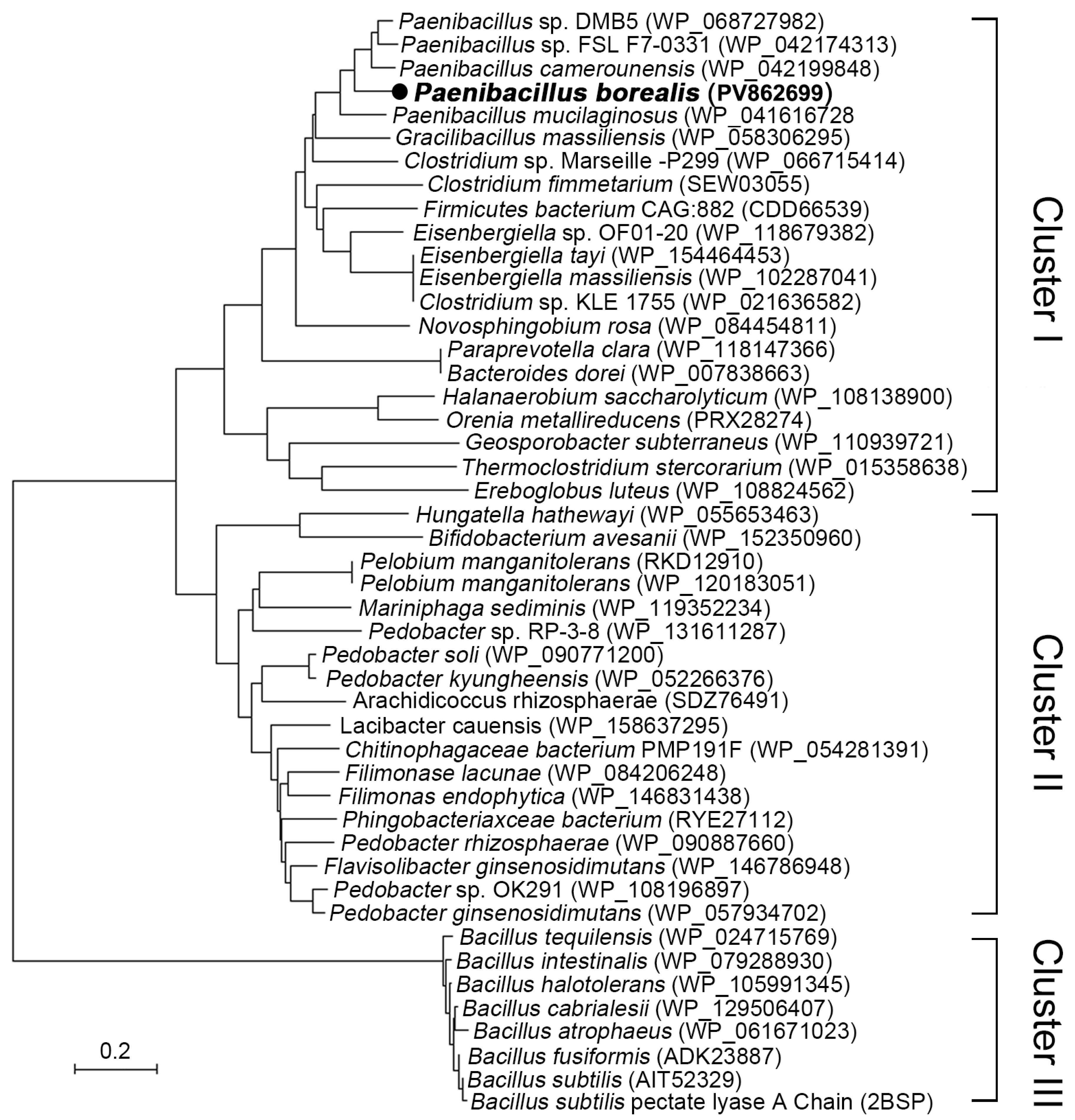

To mine the novel pectate lyase resources, the gene annotation and the evolutionary analysis on the pectate lyase from

Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and the related genus strains was conducted. The phylogeny tree among the putative and the identified B. subtilis pectate lyase was depicted as shown by

Figure 1. As shown by

Figure 1, the pectate lyase of

Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and the related genus were divided into three clusters. Cluster I contains pectate lyases from

Paenibacillus, Gracilibacillus, and

Clostridium, etc., which all come from phylum

Firmicutes. Cluster II contains enzymes from

Pelobium, Pedobacter, and

Filimonase, etc. which come from phylum Bacteroidetes. Except few strains such as

C. fimetarium (SEW03055),

Orenia metallireducens (PRX28274), and

Pelobium manganitolerans (RKD12910) from the Cluster I and Cluster II were previously annotated as polygalacturonase, most of the proteins in these two clusters are uncharacterized, which indicated that strains in these two clusters might contain rich enzyme resources. Cluster III contains the strains from genus of

Bacillus. Phylogeny this cluster divergent from the Cluster I and Cluster II. This cluster contains the 3-D structure resolved pectate lyase (PDB: 2BSP) from

B. subtilis.

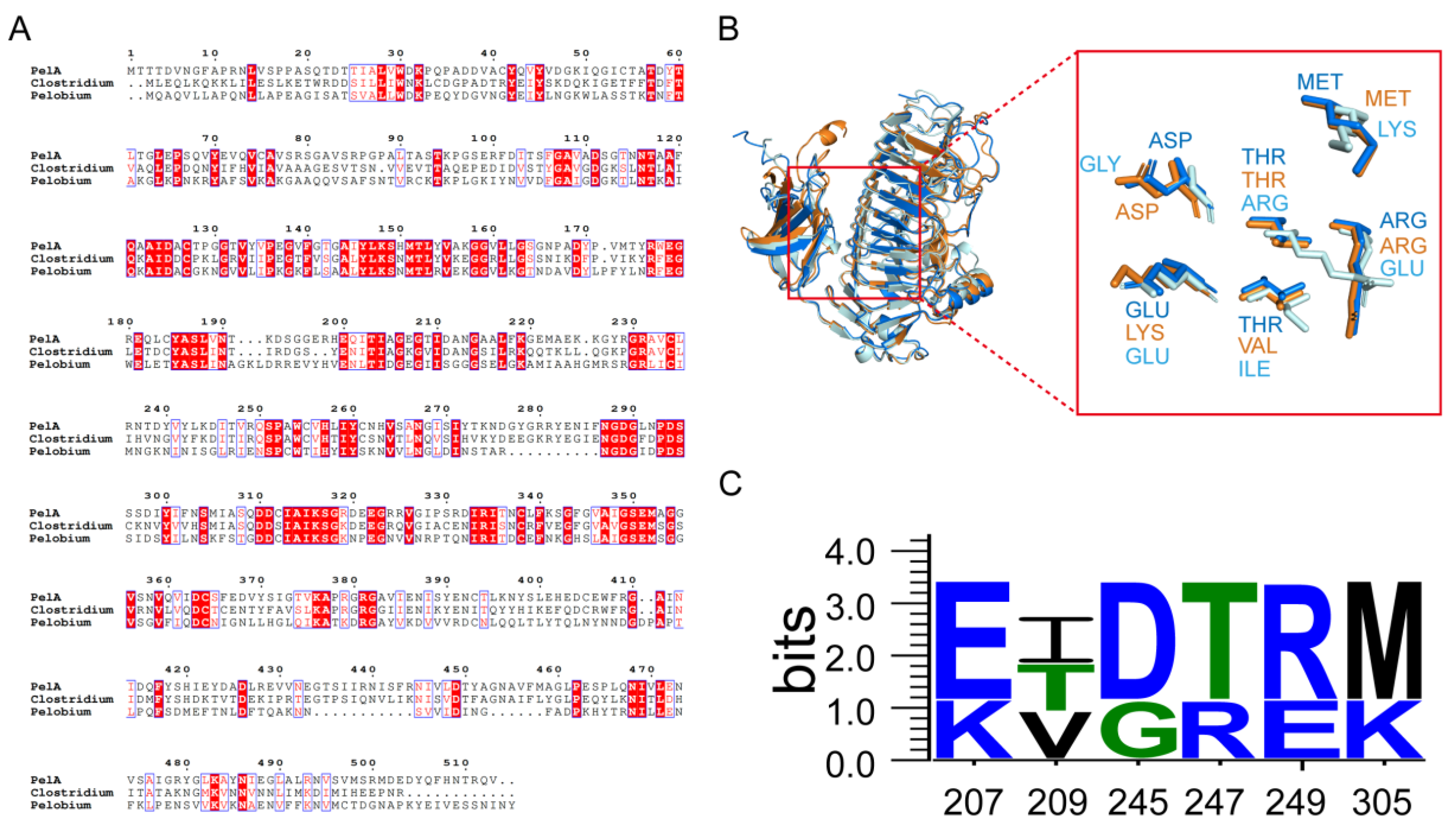

The structural alignment and conservation analysis of amino acid sequences for PelA and three other pectinases,

C. fimetarium SEW03055 (in Cluster I),

P. manganitolerans RKD12910 (in Cluster II), and

B. subtilis 2BSP (in Cluster III) revealed distinct patterns of residue conservation (

Figure 2). Based on the multiple sequence alignment results, enzymes PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910 exhibit a degree of conservation in their amino acid sequences. Enzymes PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910 in Cluster I and II shows differences in certain regions compared to the 2BSP (

Bacillus in Cluster III), potentially reflecting evolutionary or functional divergence among them. The consistency around positions 310-350 which area involved in the enzyme’s active site or substrate binding, while the variability between 420-460 could be linked to species-specific functions (

Figure 2A).

P.borealis PelA is structural homologous to the enzymes from PL family 1 (

Figure 2B). The remarkable structural feature of PelA is a predominate righthanded parallel β-helix formed by three parallel β-sheets. These three parallel b-sheets were connected by the loops or turns to form a deep barrel form structure, and formed a catalytic cleft with adjacent domain. The active amino acids and the substrate binding amino acids lie in the long loop extending from the core structure. In the superimposed structures of clefts, three alkaline amino acid K220, R231, and R249 of PelA acted as the catalytic residues were positioned (

Figure 2B). The adjacent amino acids act for substrate-binding conservatively site along the clefts. Among them, the alkaline amino acids such as K207 (LYS), R247 (ARG), R249 (ARG), and K305 (LYS) have higher ratio (

Figure 2C).

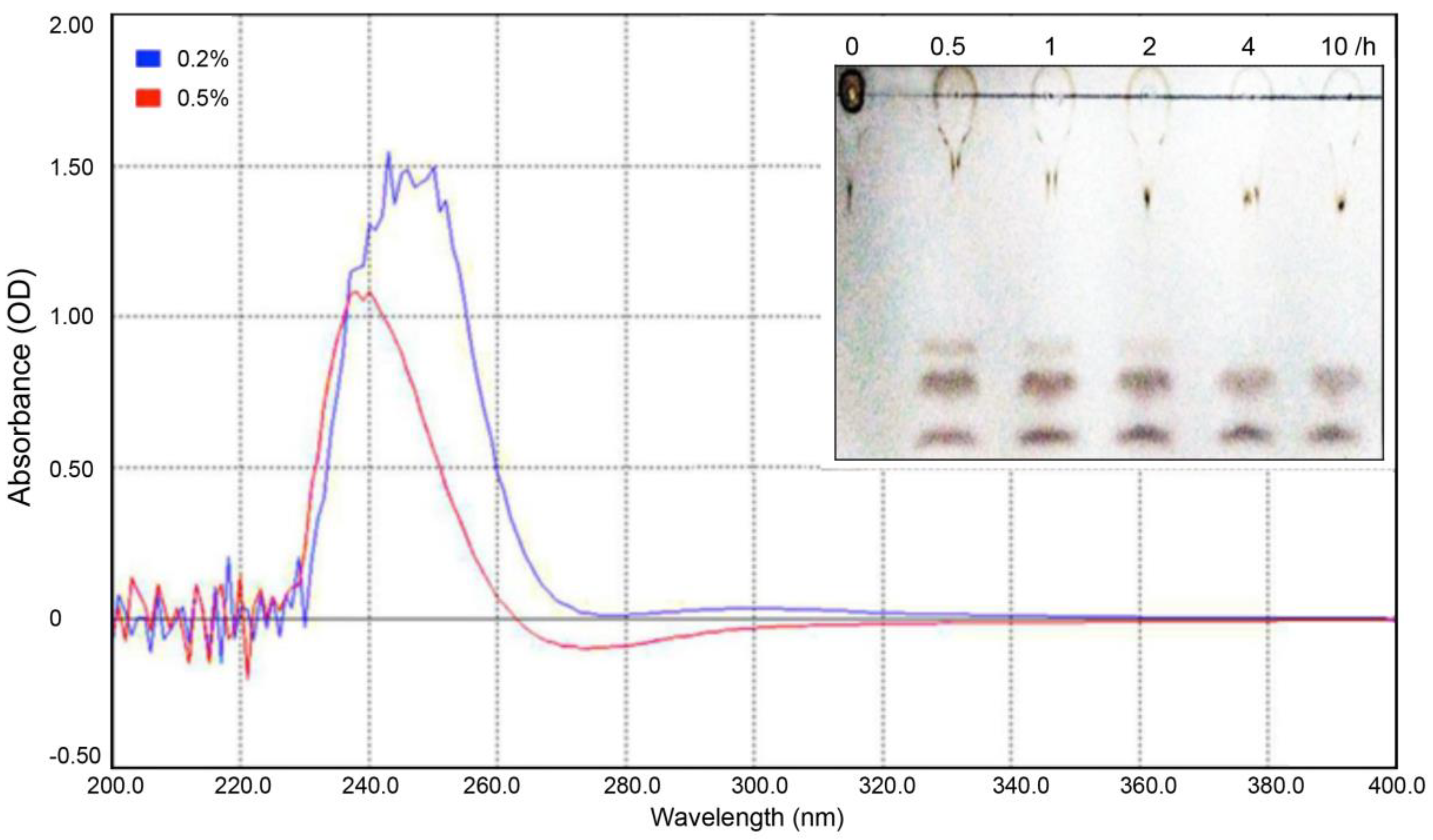

2.2. Enzymatic Definition Reveal PelA Is a Type of Alkaline Endo-Pectate Lyase

The putative pectate lyase gene

pelA from

P. borealis was cloned and expressed. The enzymatic characteristics of PelA were determined in this study (

Figure 3 and 4). To defined the type of this pectate lyase, the polygalacturonic acid (PGA) was used as the substrates, and the digested products were scanned by ultraviolet and visible spectrophotometry with the wavelength of 200-400 nm, and then were analyzed using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). As reported before [

21], the pectate lyase could break the α-1,4 glycosidic bonds of the polygalacturonic acid by trans-elimination mode, produce a C4:C5 Δ-unsaturated products, simultaneously. This Δ4:5 double bond exhibited an absorbance peak among 230-270 nm wavelengths. As shown in

Figure 3, the digested products of PGA (concentration of 0.2% and 0.5%) have strong ultraviolet absorption peak at 240-270 nm, coincided with the above speculation and indicating that the enzyme PelA from

P. borealis could be aligned into pectate lyase clusters. The TLC analysis shown that the digested products of PGA have three bonds, referring to mono-, di-, and tri-saccharide, respectively. This reflected that enzyme PelA could

endo digested on the polygalacturonan to produce the oligogalacturonic products. Thus, enzyme PelA could be described as an

endo pectate lyase.

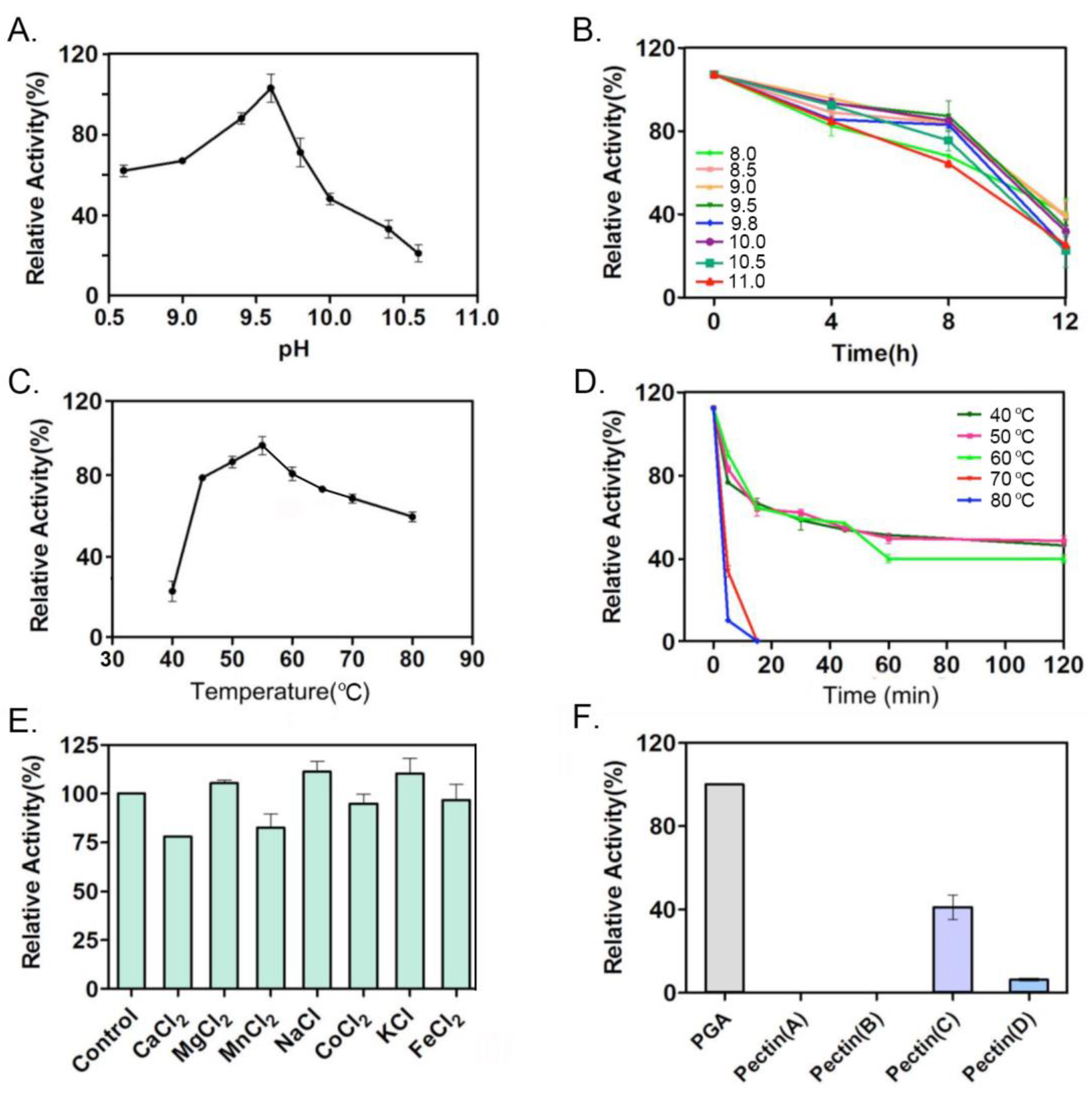

Enzymatic characteristics of PelA were determined in this study. As shown by

Figure 4A and 4B, PelA from

P. borealis is a typical alkaline pectinase, with the optimal pH of 9.5. When it was incubated in alkaline buffer above pH 9.0 up to 4 h, there still has 80% activity remained. PelA has the optimal temperature of 55

℃ (

Figure 4C), and showed a certain degree of thermal stability (

Figure 4D). Metal ion Mg

2+, Na+ and K+ could improve the enzyme activity of 5%, 11%, and 9%, while Ca

2+, Mn

2+ and Co

2+ reduced activity by 23%, 18%, and 6%, respectively (

Figure 4E). Enzyme PelA showed the preference on the pectin substrates with different degrees of esterification (

Figure 4F). It has the highest activity on the substrate PGA. Among the nature pectin with different degree of esterification, the PelA are more prefer the middle-esterified pectin (66%-69%).

2.3. Molecular Docking and Constant-pH Molecular Dynamics Analysis

Molecular docking of PelA with hexagalacturonic acid revealed that PelA binds to the substrate at subsites -3, -2, -1, +1, +2, and +3, forming hydrogen bond interactions at each position, and the binding energy was -8.5 kcal/mol. Similarly, RKD12910 forms hydrogen bonds with the six subsites of the substrate hexagalacturonic acid, with a binding energy of -8.9 kcal/mol (

Figure 5A). The electrostatic potential maps of the four different pectinase structures (PelA, 2BSP, SEW03055, and RKD12910) (

Figure 5B) provide insights into the charge distribution across their surfaces, which is critical for understanding substrate binding and catalytic activity. The maps reveal distinct patterns of positive (blue) and negative (red) charge regions, with neutral areas (green/white) varying among the structures. Enzymes PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910 tend to be neutral while 2BSP has much positive charge in active cleft. These differences likely reflect variations in amino acid composition and protonation states, influenced by the local environment or pH conditions. Regions with concentrated negative charges may indicate potential binding sites for positively charged substrates or cofactors, while positive charge clusters could facilitate interactions with negatively charged pectin components. The heterogeneity in electrostatic potential among the four pectinases suggests structural adaptations that may correlate with their specific catalytic efficiencies or substrate preferences.

The constant-pH molecular dynamics analysis of PelA was performed under pH 5.0 and pH 9.0 conditions, respectively. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) plots indicate that the systems reached equilibrium after approximately 20 ns, with RMSD values stabilizing around 0.2-0.4 nm (

Figure 6A). At pH 9.0, a slight increase in RMSD was observed compared to pH 5.0, suggesting greater conformational flexibility at higher pH values, likely due to altered protonation states of titratable residues of alkaline pectinase PelA. Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis showed that the residue flexibility varied across the protein sequences, particularly in the position of 270-300 aa and 390-440 aa, which lie in the activity cleft and the region for conformational stability, with peaks have higher mobility at pH 9 (

Figure 6B). This suggests that alkaline conditions may enhance local structural dynamics. The radius of gyration (Rg) and the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) plots under pH 5 and 9 clearly shown that the structure of PelA was more pronounced and increase in solvent exposure at pH 9.0, consistent with the observed flexibility in the whole (

Figure 6C and 6D). The λ plot indicated the deprotonated (0) or protonated state (1) under pH 5.0 and pH 9.0 conditions (

Figure 6E). The observed range suggests a mixture of protonation states. At pH 5.0, λ remains relatively stable with minor fluctuations, indicating a consistent protonation environment. In contrast, at pH 9.0, the λ values exhibit more pronounced peaks, suggesting increased protonation state transitions, likely due to the higher pH favoring deprotonation of acidic residues. This pH-dependent behavior reflects the dynamic response of the protein to environmental changes, which may influence its structure and function. The dynamic cross-correlation matrices (DCCM) map highlights differences in inter-residue contacts between the two pH conditions, with notable changes in the 200-400 residue region, underscoring pH-induced structural rearrangements (

Figure 6F).

2.4. Improving the Expression Level of PelA by Tandem Expression Cassettes Construction

To improve the gene dosage of

pelA in host genome, a series of recombinant plasmids carrying tandem

pelA gene expression cassettes, pAO-pelA, pAO-Du-pelA, and pAO-Tri-pelA was constructed (

Figure 7A and 7B). Pichia recombinants with different pelA gene copy number in genome were obtained and quantitatively checked by QPCR (

Table 1). As shown by

Table 1, recombinants AO-2 and AO-4 have one copy pelA in genome. Strains of 2AO-2 and 2AO-4 have two copies and strains of 3AO-3 and 3AO-4 have three copies

pelA in their genome, respectively. Their expression levels of

pelA in these

Pichia recombinants were evaluated in this study. As shown in

Figure 7C and 7D, with the elongation of culture time, the expression level gradually increased and reached the highest level at 96 h. The one-copy pelA carried stains shown the enzyme activity of 280 U/mL culture. The expression level of two-copies recombinants and three-copies recombinants were significantly higher than one copy. The three-copies recombinants generally have the highest enzyme activity at 96 h time point, with the activity of 720 U/mL culture in flask.

2.5. Expression of PelA in Bioreactor

To evaluate the potential for the large-scale production of PelA, the

Pichia recombinant carrying three-copies of

pelA gene were cultivated in a bioreactor. The cultivation parameters such as the dissolved oxygen (DO), gas flow, rotation speed, temperature (T

m) and the pH of the medium were controlled as shown by

Figure 8A. In the early 40 h, the Tm was controlled about 28

℃, later the Tm was kept around 25

℃. The pH of the medium was kept around 5.5 in the whole culture period. The DO was adjusted by cascaded control of the agitation rate, airflow and methanol feeding. The cell density was checked by flow cytometer during the cultivation in bioreactor (

Figure 8B). As shown by the plots, in the early stage, almost all cells are active. While with the elongation of cultivation time, the dead cells could be detected especially at 117 h. Due to better control on the cultivation parameters, the expression of PelA in the bioreactor much better than those in the flasks. As shown in

Figure 8C and 8D, the protein content gradually increased to 1.08 g/L at 117 h and the enzyme activity reach its highest 7520 U/mL culture at 106 h time point (

Figure 8E). This activity was almost ten-fold of those in flasks (see

Figure 7). While at 117 h, the decline of the activity was observed.

3. Discussions

3.1. P. borealis Alkaline Pectinase PelA Represent an Important Cluster Divergent from Bacillus pectinase

Alkaline pectate lyase is an environment-friend biocatalyzer in the degumming and papermaking processes [

6,

14]. Although the alkaline pectate lyase have been isolated from the fungi and some bacteria [

7,

10,

22,

23], the main resources were still come from Bacillus genus such as

B. tequilensis [

11],

B. subtilis [

12,

13,

24],

B. pumilus [

14], and

B. amyloliquefaciens etc [

25]. The alkaline pectinase genes in other bacteria were few mined. According to the previous reports, just two pectinases from

Paenibacillus polymyxa were reported [

26,

27]. According to the phylogeny analysis, we found strains from

Paenibacillus and related genus harbors rich pecinase resources, and could be divided into three clusters, I, II and III (

Figure 1). Except few strains such as

Clostridium fimetarium (SEW03055),

Orenia metallireducens (PRX28274), and

Pelobium manganitolerans (RKD12910) from the Cluster I and Cluster II were previously annotated, most of the proteins in these two clusters are uncharacterized, which indicated that strains in these two clusters might contain rich enzyme resources.

Enzymatic characterization revealed that PelA could digeste polygalacturonic acid into mono-, di-, and tri-saccharide, respectively. As reported before [

21], the pectate lyase could break polygalacturonic acid by trans-elimination mode into C4:C5 Δ-unsaturated products, which exhibited an absorbance peak among 230-270 nm wavelengths. As shown by

Figure 3, the digested products of PGA have strong ultraviolet absorption peak at 240-270 nm, coincided with the above speculation and indicating that the enzyme PelA from

P. borealis is a type of endo-pectate lyase. Further characterization shown that PelA has the optimal pH of 9.6 (

Figure 4). Surprisingly, metal ion Ca

2+ did not shown the stimulate to the improvement on PelA activity as reported on other type of pectinase [

28]. While this phenomenon, the pectinase exerts its potential for enzymatic ramie degumming under alkaline conditions without the requirement for additional Ca

2+ has also reported on alkaline pectate lyase, BspPelA [

29].

3.2. Molecular Charactering Revealed PelA Clusters Were Alkaline Adaptation and Structural Divergent from Bacillus pectinase

Pectinases show a typical parallel β-helix topology, in which the β-strands are folded into a large righthanded coil [

28,

30]. As revealed in this study, the major differences among PelA and related structures exist in the size and conformation of the loops that protrude from and cover the parallel β-helix core. According to the sequence alignment, in the superimposed structures of clefts region, amino acids such as K207 (LYS), R247 (ARG), R249 (ARG), and K305 (LYS) act for substrate-binding conservatively existed site along the clefts (

Figure 2). While the charge distribution revealed by the electrostatic potential maps found that the cleft and adjacent region of PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910 trend to by neutral and

Bacillus pectinase 2BSP is alkaline environments. The heterogeneity in electrostatic potential among the four pectinases suggests structural adaptations that may correlate with their specific catalytic efficiencies or substrate preferences. Furhter molecular dynamic analysis revealed that, most isozymes exert catalytic activity under alkaline conditions with a pH optimum around 9.0 (

Figure 6).

As shown in this study, the Ca

2+ addition into the reaction mixture did not enhance PelA activity, which in a way different from the other type pectate lyases [

28]. Same phenomenon was found on pectinase BspPelA, that the activity measurement of does not require addition of calcium [

29]. As revealed by the structure of PelA and related enzymes, some of the highly conserved Ca

2+ binding residues and secondary structures are altered in PelA, making it difficult to coordinate with Ca

2+ as in the other pectate lyases. On the molecular docking, the interaction between the active cleft of enzyme PelA and hexagalacturonic acid, we found PelA forms some direct enzyme–substrate interactions instead of using Ca

2+ ions bridging in the extremely alkaline environment among these members as PelA and RKD12910 (

Figure 5A).

3.3. Improving the Gene Dosage of PelA and High-Density Cultivation Realized Its High-Level Production

To realize the industrial application, the high-level expression is the prerequisite to improve its economic competent. In order to improve the heterologous expression level of

pelA in

P. pastoris, in this study, the method of improving the gene dosage the hosts genome was used. The gene copy number is an important factor to correlate with the expression of the gene [

31]. Previous works have proved that increasing the copy number of the gene in the host genome could increase its expression level correspondantly [

32]. As shown in this study, by constructing the tandem expression cassettes of

pelA gene, we successfully obtained the

Pichia recombinants carrying one, two or three-copy of

pelA in the genome. Three-copy pelA carried stains almost has three-fold activity of one-copy

pelA stains (

Figure 7), further revealing that improving the gene dosage could efficiently improving the expression level of gene. Due to better parameters control than the flask, after parameters optimization, strains carrying three-copy of

pelA in genome have reach the expression level of 7520 U/mL culture in the bioreactor (

Figure 8). This level apparently higher than those primarily expression of pectate lyase gene from

Bacillus genus stains [

24,

33].

In the cultivation process in bioreactor, we noticed that at the 117 h time point, although the total protein content in the culture was higher than those in 106 h, the enzyme activity was lower than that (

Figure 8). Thus, the cell viability in the whole culture process was checked by flow cytometer. As shown by the

Figure 8B, in the 57 h, the living cells density gradually increased into a high value. Meanwhile, the dead cells just about 2.31% of the total cells. With the elongation of the cultivation time, the ratio of the dead cells gradually increased to 19.6% at 117 h, which was about three-fold of 106 h time point. It was speculated that the decrease in cell viability in the fed batch, which could be owing to either nutrients deficient or buildup of toxic metabolic by-products, is the main reason for the decline of enzyme activity. In the future work, improving the cell viability in bioreactor might be an efficient method to improving the expression of target proteins.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phylogeny Analysis, Structural Alignment and Conservation Analysis of Pectate Lyases

The evolutionary analysis on the pectate lyase from

Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and the related genus strains was conducted by using the MEGA7 software [

16]. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-Joining method, and the evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method, and the phylogeny tree was depicted basing on the evolutionary distance by tree program.

The three-dimensional structures of

P. borealis PelA,

Clostridium fimetarium (SEW03055),

Pelobium manganitolerans (RKD12910) were obtained through modeling with AlphaFold3 (

https://alphafold.com). To align the structures of PelA and the three other pectinases,

B. subtilis (2BSP),

C. fimetarium (SEW03055),

P. manganitolerans (RKD12910) using PyMOL and perform conservation analysis with ESPript 3.0 (

https://espript.ibcp.fr) and WebLogo 3 (

https://weblogo.threeplusone.com). The structure was viewed with PyMOL software (

https://pymol.org).

4.2. Gene Cloning, Expression and Enzymatic Characterizing of PelA

The putative pectate lyase gene

pelA in the genome of

P. borealis was cloned and the sequence has deposited into GenBank with ID: PV862699, and then sub-cloned into

Pastoris pastoris expression vector pAO815 to get the recombinant plasmid pAO-pelA, and transformed into strain GS115 by electroporation. The PelA recombinants colonies were culture and inducible expressed for about 96h in

Pichia as described by Mattanovich et al [

17]. The supernatant of the culture was collected by centrifugation and then gone to purification by Sephadex G-75 (GE Healthcare).

To measure the activity of the PelA enzyme, the reaction mixture was consisted of 900 μL 0.33% (w/v) polygalacturonic acid (PGA) dissolved in Gly-NaOH buffer (pH 9.0) and 100 μL diluted enzyme, and then incubated at 50℃for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by boiling in water for 5 min. The same reaction mixture containing 100 μL of heat-inactivated enzyme was used as the control. To determine the optimal reaction temperature of PelA, a series of temperature as 40℃, 45℃, 50℃, 55℃, 60℃, 65℃, 70℃ and 80℃ were set, and the activity of the PelA under these temperatures was measured. To detect the thermal stability of the enzyme, PelA was incubated at 40℃, 50℃, 60℃, 70℃ and 80℃ for 10 min, 30 min, 60 min, 90 min, 120 min and 240 min, respectively, and then the remaining activity were measured. To investigate the effect of pH on PelA activity, a series of pH of the reaction buffer of 8.0, 8.5, 9.0, 9.5, 9.8, 10.0, 10.5, and 11.0 were set. Correspondently, to detect the pH stability of the enzyme, the PelA was incubated in the above buffer for 4 h, 8 h and 12 h, respectively, and then the remaining activity were measured. To determine the effect of metal ions on enzyme activity, the salts MgCl2, FeCl2, MnCl2, CaCl2, CuCl2, ZnCl2 were dissolved in the Gly-NaOH buffer (pH 9.6) to the final centration of 2 mmol/L. PGA and nature pectin with different esterification degree were dissolved in Gly-NaOH buffer (pH 9.6) and then used as the substrates to investigate the specificity of PelA.

Pectate lyase activity was assayed by measuring the reducing sugars liberated using polygalacturonic acid (PGA) as the substrate. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that liberated 1 μmol of reducing sugar per min under the assay conditions. Enzyme activity was determined by the DNS method. The products liberated from PGA by the enzymes were checked by thin layer chromatography. The developing solvent was a mixture of n-butanol, water and acetic acid with a ratio of Vn:Vw:Va = 5:3:2. The developer was a mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and Ethanol (Vs:Ve=1:19).

4.3. Construction of the Tandem Expression Cassettes of PelA

The pelA gene was inserted into the P. pastoris expression vector pAO815 to get the plasmid pAO-PelA. Then the expression cassette 5’AOX1-PelA-TT was cut from the recombinant plasmid pAO-PelA by Bgl II and BamH I digestion, and then ligated into the vector pAO-PelA to get the plasmid pAO-Du-PelA carrying two expression cassette 5’AOX1-PelA-TT. The three-copy expression cassette plasmid pAO815-Tri-PelA was constructed by inserting the expression cassette 5’AOX1-PelA-TT into the plasmid pAO815-Du-PelA. These recombinant plasmids were then transformed into P. pastoris by electroporation with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.4. Detection of Multiple Copies of the Integration by Quantitative PCR

The real time quantitative PCR (QPCR) method was used to quantify the copy number of

PelA gene in the genome of

P. pastoris. The primers PelF2 (5’-GGACAGGTGCACGTCTACAA-3’) and PelR2 (5’-CCGTTCAACAAGGTACCGGA-3’) were designed according to the sequence of pel AO. The primers gapdF (5’-TTGTCGGTGTCAACGAGGAG-3’) and gapdR (5’-GGTCTTTTGAGTGGC GGTC-3’) were designed based on the sequence of the glyceraldehyde triphosphate dehydrogenase gene (

gapd) (GeneBank Accession No. U62648). The process for QPCR was conducted mainly according to the description by Lee et al and revised by Abad et al [

18,

19].

4.5. Inducible Expression of PelA in Bioreactor and Yeast Cell Viability Counting

The inducible expression of PelA in bioreactor was conducted mainly according to the description of Mattanovich et al [

17] and revised by Yang et al [

20]. In the cultrivation process, the fermentation parameters were maintained as Tm=28

℃, pH=5.5, dissolved oxygen was maintained as >15%. In the methanol induced expression phase, the temperature was set at 25

℃, and the methanol was fed into the broth at a rate of 2 mL /h﹒L

-1 of broth. The cell viability in the bioreactor was checked by flow cytometry method in CytExpert (Beckman, USA). Dead cells could be stained with propidium iodide (PI) and emitted strong red fluorescence at 660 nm wavelength, whereas the living cells could not be stained and only emitted weak autofluorescence. The living cells and the dead cells were separated by comparing the differences in fluorescence intensity.

4.6. Molecular Docking and Constant-pH Molecular Dynamics Analysis

Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina software (

https://vina.scripps.edu). Both the small molecule substrates and enzymes were preprocessed prior to docking. The docking center was set at coordinates x=0.8, y=4.4, and z=-1.9, with a cubic box size of 80 Å edge length and a spacing step of 0.375. Conformations were ranked based on docking scores, and the optimal conformation was selected for binding mode analysis.

Constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) simulations were performed to investigate the pH-dependent behavior of the system. All simulations were conducted using the GROMACS 2023.4 software package with the charmm36 force field (

https://www.gromacs.org). The protonation states of titratable residues were sampled using a hybrid Monte Carlo/molecular dynamics approach as implemented in the CpHMD module. The initial protein structure of PelA was obtained from AlphaFold3. The system was solvated in a cubic box of TIP3P water molecules. Sodium and chloride ions were added to neutralize the system and achieve a physiological ionic strength of 0.15 mol/L. The simulation pH was maintained at pH 5.0 and pH 9.0 using the λ-dynamics method, with protonation state transitions attempted every 1000 steps, respectively. The system was energy-minimized using the steepest descent algorithm until convergence (<1000 kJ/mol/nm). Equilibration was performed in two stages: (1) a 100 ps NVT simulation at 300 K using the Berendsen thermostat, and (2) a 100 ps NPT simulation at 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. Production runs were conducted for 100 ns in the NPT ensemble, with a time step of 2 fs. Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, with a cutoff of 1.0 nm for both electrostatic and van der Waals interactions. All bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the LINCS algorithm.

5. Conclusions

Molecular characterizing a novel alkaline endo-pectate lyase from P. borealis PelA revealed it represent an important cluster divergent from the well-characterized Bacillus pectinase. The strategy of improving the gene dosage by constructing the tandem expression cassettes of gene has successfully improved the secretory level of PelA. After parameters optimization, it can reach the expression level of 7520 U/mL culture in the bioreactor. This study has fulfilled the high-level secretory expression of alkaline pectinase, facilitated its industrial bioapplication and also could be a reference for future work on the heterologous expression of target gene.

Author Contributions

Ying Han: Investigation, Data curation. Xiao-Bo Peng: Investigation, Data curation. Shu-ya Wei: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Visualization. Qi-guo Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization. Jiang-Ke Yang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Plan Project of Hubei Province, China (2024BCB025) and Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation-General Project(2019CFB625).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhongkekeyi (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd. for the technical assistance on the computational simulations in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Uluisik, S.; Seymour, G.B. Pectate lyases: Their role in plants and importance in fruit ripening [J]. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; P. K. Yadav, D.; Yadav, and K. D. S. Yadav. Pectin lyase: A review. [J]. Process Biochem. 2009, 44, 1–10.

- Reid, I.; Ricard, M. Pectinase in papermaking: solving retention problems in mechanical pulps bleached with hydrogen peroxide [J]. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2000, 26, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.S.; Du, Y.M.; Zhang, J.Y. Degumming of ramie fibers by alkalophilic bacteria and their polysaccharide-degrading enzymes [J]. Bioresour Technol. 2001, 78, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoondal, G.S.; Tiwari, R.P.; Tewari, R.; et al. Microbial alkaline pectinases and their industrial applications: a review [J]. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002, 59, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daniell, H.; Ribeiro, T.; Lin, S.; Saha, P.; McMichael, C.; Chowdhary, R.; Agarwal, A. Validation of leaf and microbial pectinases: commercial launching of a new platform technology [J]. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019, 17, 1154–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamijo, J.; Sakai, K.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, K.; Kunitake, E.; Shimizu, M.; Kato, M. Identification and characterization of a thermostable pectate lyase from Aspergillus luchuensis var. saitoi [J]. Food Chem. 2019, 276, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Dubey, A.K.; Anand, G.; Kumar, R.; Yadav, D. Purification and biochemical characterization of an alkaline pectin lyase from Fusarium decemcellulare MTCC 2079 suitable for Crotalaria juncea fiber retting [J]. J Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, S161–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, S.; Satyanarayana, T. Production, characterization and application of a thermostable polygalacturonase of a thermophilic mould Sporotrichum thermophile Apinis [J]. Bioresour Technol. 2004, 94, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Wang, D.; Lv, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gelbic, I.; Ye, X. Archives of microbiology: screening of pectinase-producing bacteria from citrus peel and characterization of a recombinant pectate lyase with applied potential [J]. Arch Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Xin, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, M.; Liu, H. Production of alkaline pectinase: a case study investigating the use of tobacco stalk with the newly isolated strain Bacillus tequilensis CAS-MEI-2-33 [J]. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 19,45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Kang, Z.; Ling, Z.; Cao, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.; Du, G.; Chen, J. High-level extracellular production of alkaline polygalacturonate lyase in Bacillus subtilis with optimized regulatory elements [J]. Bioresour Technol. 2013, 146, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kapoor, M.; Sharma, K.K.; Nair, L.M.; Kuhad, R.C. Production and recovery of an alkaline exo-polygalacturonase from Bacillus subtilis RCK under solid-state fermentation using statistical approach [J]. Bioresour Technol. 2008, 99, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Rathore, M.; Sharma, M. Microbial pectinase: sources, characterization and applications. [J]. Rev Environ Sci Bio. 2013, 12, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Suominen, I.; Kämpfer, P.; Juhanoja, J.; Salkinoja-Salonen, M.; Haahtela, K. Paenibacillus borealis sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing species isolated from spruce forest humus in Finland [J]. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001, 51, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets [J]. Mol Biol Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattanovich, D.; Branduardi, P.; Dato, L.; Gasser, B.; Sauer, M.; Porro, D. Recombinant protein production in yeasts [J]. Methods Mol Biol. 2012, 824, 329–538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Shin, S.G.; et al. Absolute and relative QPCR quantification of plasmid copy number in Escherichia coli [J]. J Biotechnol. 2006, 123, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad, S.; Kitz, K.; Hörmann, A.; et al. Real-time PCR-based determination of gene copy numbers in Pichia pastoris [J]. Biotechnol J. 2010, 5, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.K.; Chen, Q.C.; Zhou, B.; Wang, XJ.; Liu, SQ. Manno-oligosaccharide preparation by the hydrolysis of konjac flour with a thermostable endo-mannanase from Talaromyces cellulolyticus [J]. J Appl Microbiol. 2019, 127, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahuhta, M.; Brunecky, R.; Chandrayan, P.; Kataeva, I.; Adams, MW.; Himmel, ME.; Lunin, VV. The structure and mode of action of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii family 3 pectate lyase in biomass deconstruction [J]. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013, 69, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanasova, L.; Dubey, M.; Grujić, M.; Gudmundsson, M.; Lorenz, C.; Sandgren, M.; Kubicek, C.P.; Jensen, D.F.; Karlsson, M. Evolution and functional characterization of pectate lyase PEL12, a member of a highly expanded Clonostachys rosea polysaccharide lyase 1 family [J]. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wu, P.; Jiang, S.; Selvaraj, J.N.; Yang, S.; Zhang, G. A new cold-active and alkaline pectate lyase from antarctic bacterium with high catalytic efficiency [J]. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5231–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Rao, L.; Xue, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a highly active alkaline pectate lyase from alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. N16-5 [J]. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekli, S.; Aktas, B.; Gencer, D.; Aslim, B. Biochemical and molecular characterizations of a novel ph- and temperature-stable pectate lyase from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens S6 for industrial application [J]. Mol Biotechnol. 2019, 61, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, C.H.; Tsai, C.H.; Tu, J.; Tang, S.H.; Liu, C.C. Expression and thermostability of Paenibacillus campinasensis BL11 pectate lyase and its applications in bast fibre processing. [J]. Ann Appl Biol. 2011, 158, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.F.; Gao, J. A novel PL9 pectate lyase from Paenibacillus polymyxa KF-1: cloning, expression, and its application in pectin degradation [J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 22, 20, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Cao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Liu,W.; Ju, J.; Ma, Y. Structure of an alkaline pectate lyase and rational engineering with improved thermo-alkaline stability for efficient ramie degumming [J]. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 538. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Ye, J.; Xue, Y.; Ma, Y. Directed evolution and structural analysis of alkaline pectate lyase from the alkaliphilic bacterium Bacillus sp. strain N16-5 to improve its thermostability for efficient ramie degumming [J]. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015, 1, 81, 5714–5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Huang, C.H.; Liu, W.; Ko, T.P.; Xue, Y.; Zhou, C.; Guo, R.T.; Ma, Y. Crystal structure and substrate-binding mode of a novel pectate lyase from alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. N16-5 [J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012, 6, 420, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Feulner, P.G.D.; Eizaguirre, C.; Lenz, TL.; Bornberg-Bauer, E.; Milinski, M.; Reusch, TBH.; Chain, FJJ. Genome-wide genotype-expression relationships reveal both copy number and single nucleotide differentiation contribute to differential gene expression between stickleback ecotypes [J]. Genome Biol Evol. 2019, 11, 2344–2359.

- Song, X.; Shao, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, J. Improved the expression level of active transglutaminase by directional increasing copy of mtg gene in Pichia pastoris [J]. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 30, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klug-Santner, B.G.; Schnitzhofer, W.; Vrsanska, M.; et al. Purification and characterization of a new bioscouring pectate lyase from Bacillus pumilus BK2 [J]. J Biotechnol. 2006, 121, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The phylogeny analysis on the pectate lyase from Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and the related genus strains was conducted by using the MEGA7 software. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length=9.13 us shown. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method.

Figure 1.

The phylogeny analysis on the pectate lyase from Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and the related genus strains was conducted by using the MEGA7 software. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length=9.13 us shown. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method.

Figure 2.

The sequence and structural alignment of pectinases. (A) The conservation analysis of PelA (Paenibacillus), SEW03055 (Clostridium), and RKD12910 (Pelobium). Red background indicates fully conserved amino acids, while blue boxes represent specific structural or functional regions. (B) The structural alignment of pectinases PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910. PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910 are represented in blue, orange, and palecyan, respectively. The specific amino acid residues involved in the active site or ligand interactions were highlighted. (C) The conservation analysis of key residues.

Figure 2.

The sequence and structural alignment of pectinases. (A) The conservation analysis of PelA (Paenibacillus), SEW03055 (Clostridium), and RKD12910 (Pelobium). Red background indicates fully conserved amino acids, while blue boxes represent specific structural or functional regions. (B) The structural alignment of pectinases PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910. PelA, SEW03055, and RKD12910 are represented in blue, orange, and palecyan, respectively. The specific amino acid residues involved in the active site or ligand interactions were highlighted. (C) The conservation analysis of key residues.

Figure 3.

Analysis the products of PGA by digested with pectinase PelA. The PGA digested products were scanned at wavelength (200 nm-400 nm). The inserted was the TLC analysis of the PGA products. Line 1 was PGA substrates, line 2-6 were the PGA products digested by PelA at 55℃ for 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 10 h.

Figure 3.

Analysis the products of PGA by digested with pectinase PelA. The PGA digested products were scanned at wavelength (200 nm-400 nm). The inserted was the TLC analysis of the PGA products. Line 1 was PGA substrates, line 2-6 were the PGA products digested by PelA at 55℃ for 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 10 h.

Figure 4.

Enzymatic characteristics of pectinase PelA. ( A ) the optimal pH of PelA and B) the stability of PelA by incubated it in the buffer with different pH and the remaining activity was checked at interval. ( C ) the optimal temperature of PelA and D) the stability of PelA by incubated it under different temperature and the remaining activity was checked at interval. ( E ) The activity of PelA by incubating the enzyme in different metalion, and F) indicated the activity of PelA on different pectin substrates.

Figure 4.

Enzymatic characteristics of pectinase PelA. ( A ) the optimal pH of PelA and B) the stability of PelA by incubated it in the buffer with different pH and the remaining activity was checked at interval. ( C ) the optimal temperature of PelA and D) the stability of PelA by incubated it under different temperature and the remaining activity was checked at interval. ( E ) The activity of PelA by incubating the enzyme in different metalion, and F) indicated the activity of PelA on different pectin substrates.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking of pectinase with substrate hexagalacturonic acid and the electrostatic potential maps of the four different pectinase structures. (A) The molecular docking of pectinases PelA and RKD12910 with hexagalacturonic acid, respectively. (B) The electrostatic diagram of pectinase PelA, 2BSP, SEW03055, and RKD12910. The positive (blue), negative (red), and neutral (green/white) charge regions were marked out.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking of pectinase with substrate hexagalacturonic acid and the electrostatic potential maps of the four different pectinase structures. (A) The molecular docking of pectinases PelA and RKD12910 with hexagalacturonic acid, respectively. (B) The electrostatic diagram of pectinase PelA, 2BSP, SEW03055, and RKD12910. The positive (blue), negative (red), and neutral (green/white) charge regions were marked out.

Figure 6.

The constant-pH molecular dynamics simulations of PelA. The RMSD (A), RMSF (B), Rg (C), SASA (D), λ (E), and DCCM (F) analysis of PelA under pH 5.0 and 9.0, respectively. In DCCM analysis, the upper left is the DCCM of PelA under pH 5.0, and the lower right is pH 9.0. Fig. E shows λ fluctuating around 0 to 0.4 of PelA under pH 5.0 (blue) and pH 9.0 (green) conditions. Values near 0 indicate a predominantly deprotonated state, while values 1 indicate a protonated state. The DCCM map highlights differences in inter-residue contacts between the two pH conditions.

Figure 6.

The constant-pH molecular dynamics simulations of PelA. The RMSD (A), RMSF (B), Rg (C), SASA (D), λ (E), and DCCM (F) analysis of PelA under pH 5.0 and 9.0, respectively. In DCCM analysis, the upper left is the DCCM of PelA under pH 5.0, and the lower right is pH 9.0. Fig. E shows λ fluctuating around 0 to 0.4 of PelA under pH 5.0 (blue) and pH 9.0 (green) conditions. Values near 0 indicate a predominantly deprotonated state, while values 1 indicate a protonated state. The DCCM map highlights differences in inter-residue contacts between the two pH conditions.

Figure 7.

Expression of pectinase PelA by constructing the tandem expression cassettes. (A) Schematic diagram of the organization of PelA gene expression cassettes. (B) Checking the size of the one-, two- and three-copy of the concatemers of expression cassettes. (C) SDS-PAGE checking the proteins the culture of BtChy recombinants. (D) The enzyme activity of the recombinants carrying different pelA gene copies in genome.

Figure 7.

Expression of pectinase PelA by constructing the tandem expression cassettes. (A) Schematic diagram of the organization of PelA gene expression cassettes. (B) Checking the size of the one-, two- and three-copy of the concatemers of expression cassettes. (C) SDS-PAGE checking the proteins the culture of BtChy recombinants. (D) The enzyme activity of the recombinants carrying different pelA gene copies in genome.

Figure 8.

Cultivation of yeast recombinants and the expression of PelA in the 14-L bioreactor. (A) the parameters changed across the whole culture period. (B) The cell counted by flow cytometer during the cultivation in bioreactor. The V1L plot was the proportion of living cells, and V1R plot was the proportion of dead cells. (C) and (D) the proteins profiles and the content in supernatant of culture in the bioreactor. (E) The pectinase activity of the culture in the bioreactor. The samples were aliquoted at interval of 24 h, 48 h, 57 h, 80 h, 96 h, 106 h, and 117 h time points. .

Figure 8.

Cultivation of yeast recombinants and the expression of PelA in the 14-L bioreactor. (A) the parameters changed across the whole culture period. (B) The cell counted by flow cytometer during the cultivation in bioreactor. The V1L plot was the proportion of living cells, and V1R plot was the proportion of dead cells. (C) and (D) the proteins profiles and the content in supernatant of culture in the bioreactor. (E) The pectinase activity of the culture in the bioreactor. The samples were aliquoted at interval of 24 h, 48 h, 57 h, 80 h, 96 h, 106 h, and 117 h time points. .

Table 1.

The copy number of pectate lyase gene pelA in the genome of yeast recombinants detected by Quantitative PCR.

Table 1.

The copy number of pectate lyase gene pelA in the genome of yeast recombinants detected by Quantitative PCR.

| |

Ct mean of pelA gene |

Copy number pelA gene in the reaction |

Ct mean of gapdh gene |

Copy number of gapdh gene in the reaction |

Copy number of pelA in a genome |

| AO-2 |

4.738 |

5.265×10^7 |

16.700 |

4.930×10^7 |

1.068 |

| AO-4 |

5.096 |

5.008×10^7 |

16.501 |

5.090×10^7 |

0.984 |

| 2AO-2 |

3.927 |

9.930×10^7 |

16.503 |

5.010×10^7 |

1.982 |

| 2AO-4 |

3.922 |

9.955×10^7 |

16.495 |

5.079×10^7 |

1.960 |

| 3AO-3 |

3.291 |

1.525×10^8 |

16.498 |

5.095×10^7 |

2.993 |

| 3AO-4 |

3.304 |

1.513×10^8 |

16.501 |

5.058×10^7 |

2.992 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).