Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Strains

2.2. Amino Acid Sequence Alignment

2.3. Gene Cloning, Expression and Purification of TcDAEase

2.4. Enzyme Assay

2.5. Biological Characteristics of TcDAEase

2.6. Substrate Specificity and Kinetic Parameters

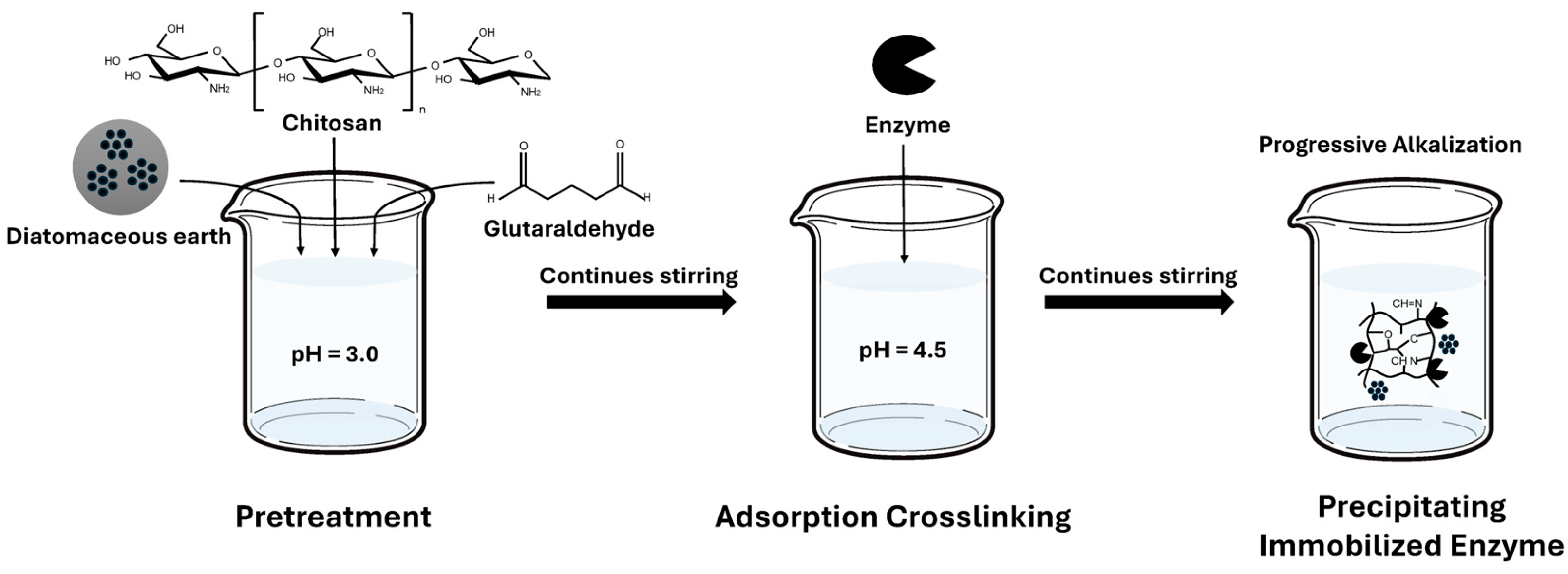

2.7. TcDAEase Immobilization Procedure

2.8. Characterization of Immobilized TcDAEase

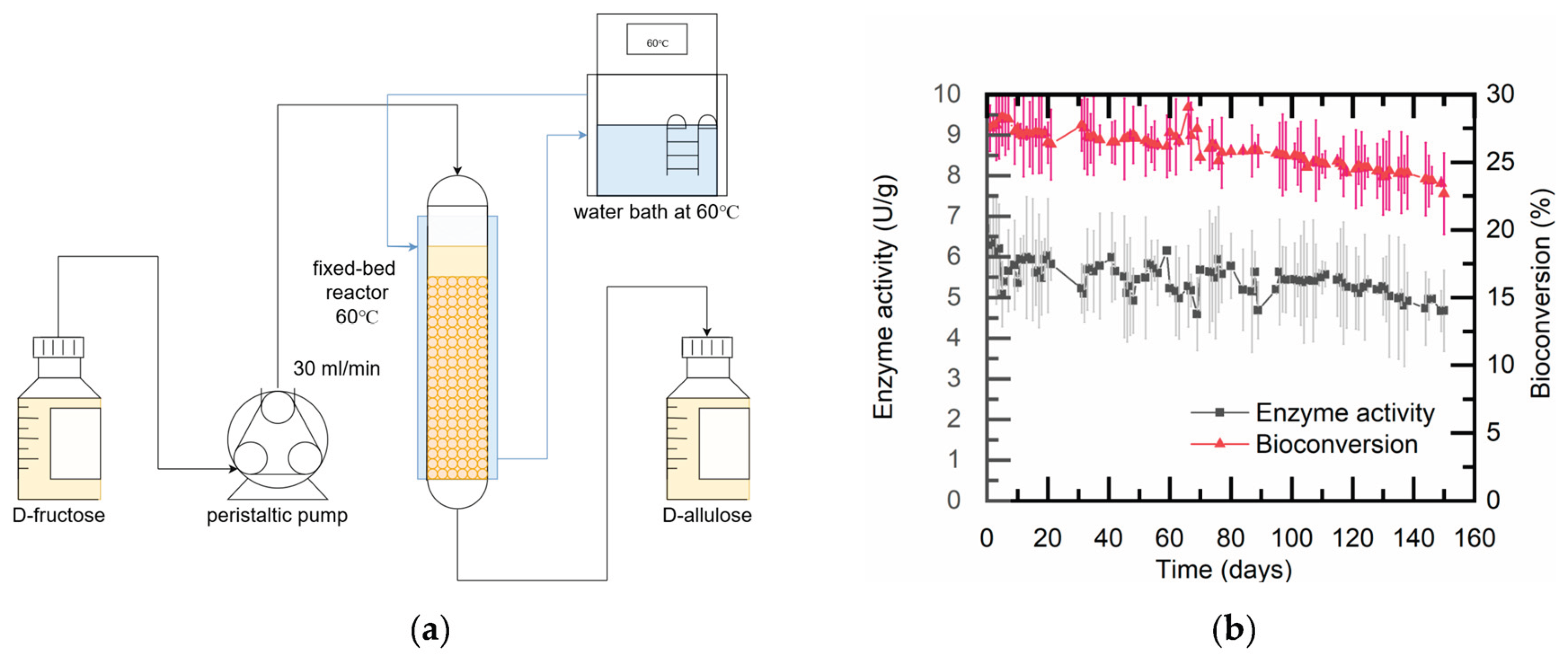

2.8. Production of D-Allulose by a Continuous Packed-Bed Reactor

3. Results and Discussion

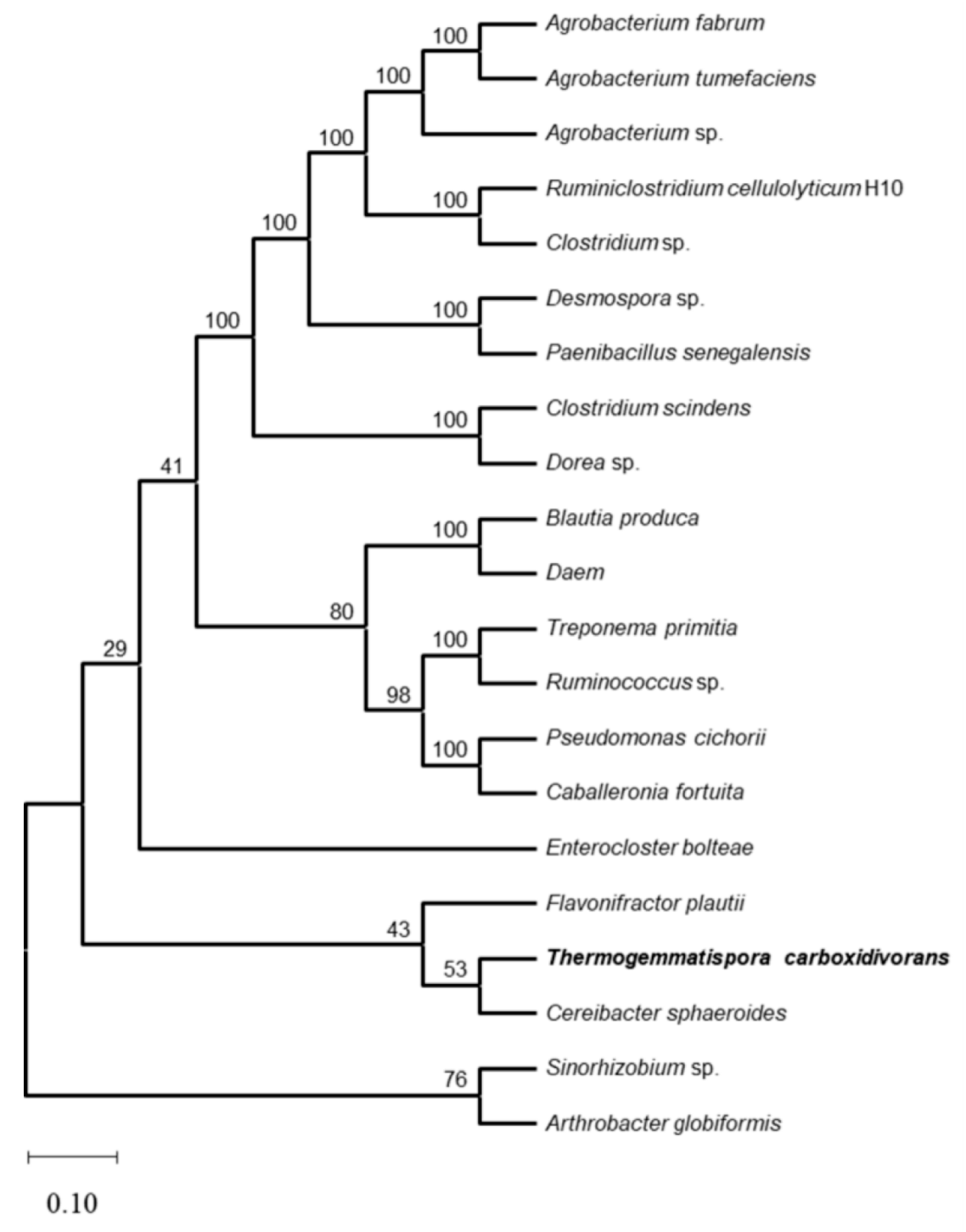

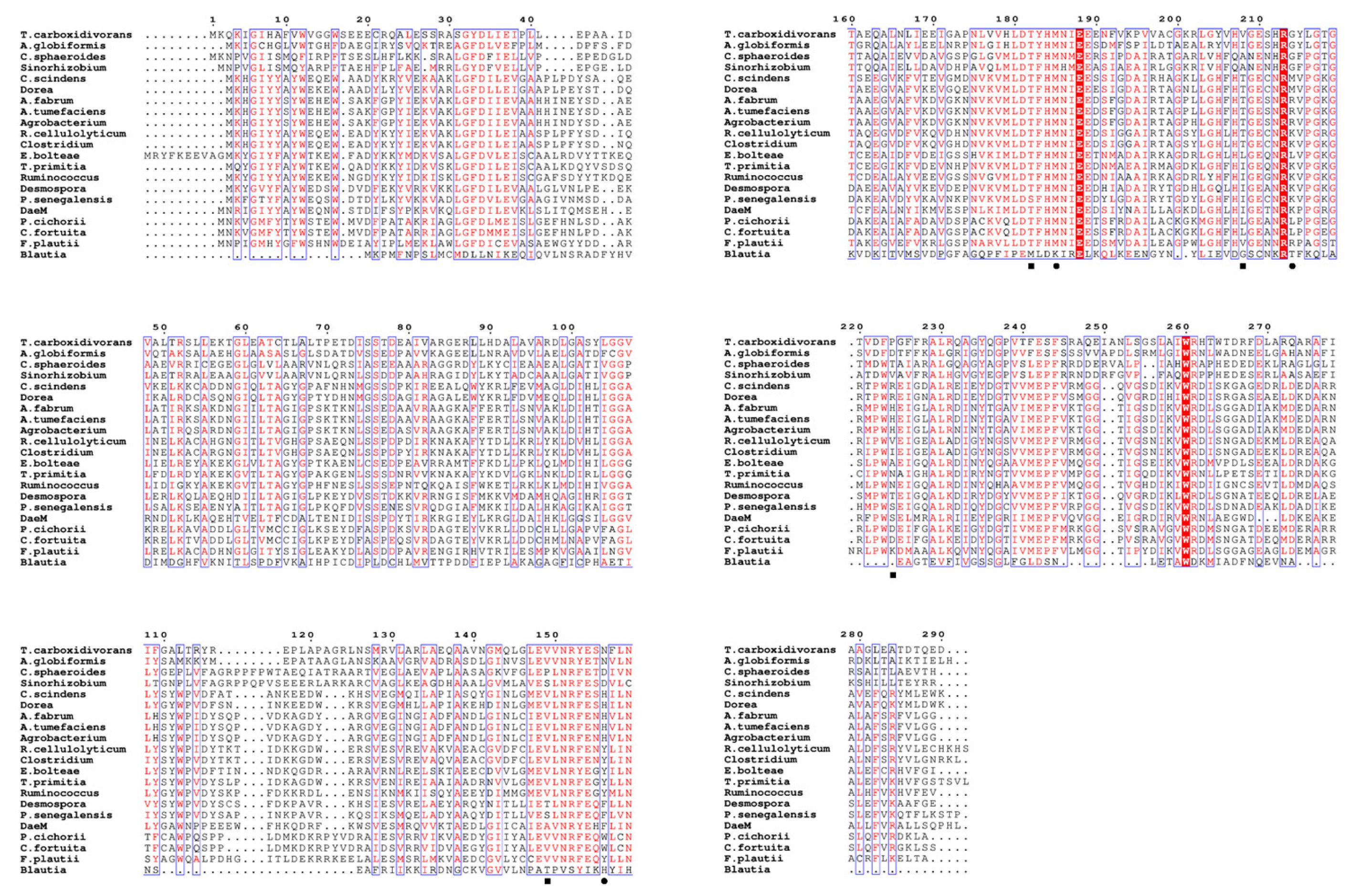

3.1. Amino Acid Sequence Alignment of TcDAEase

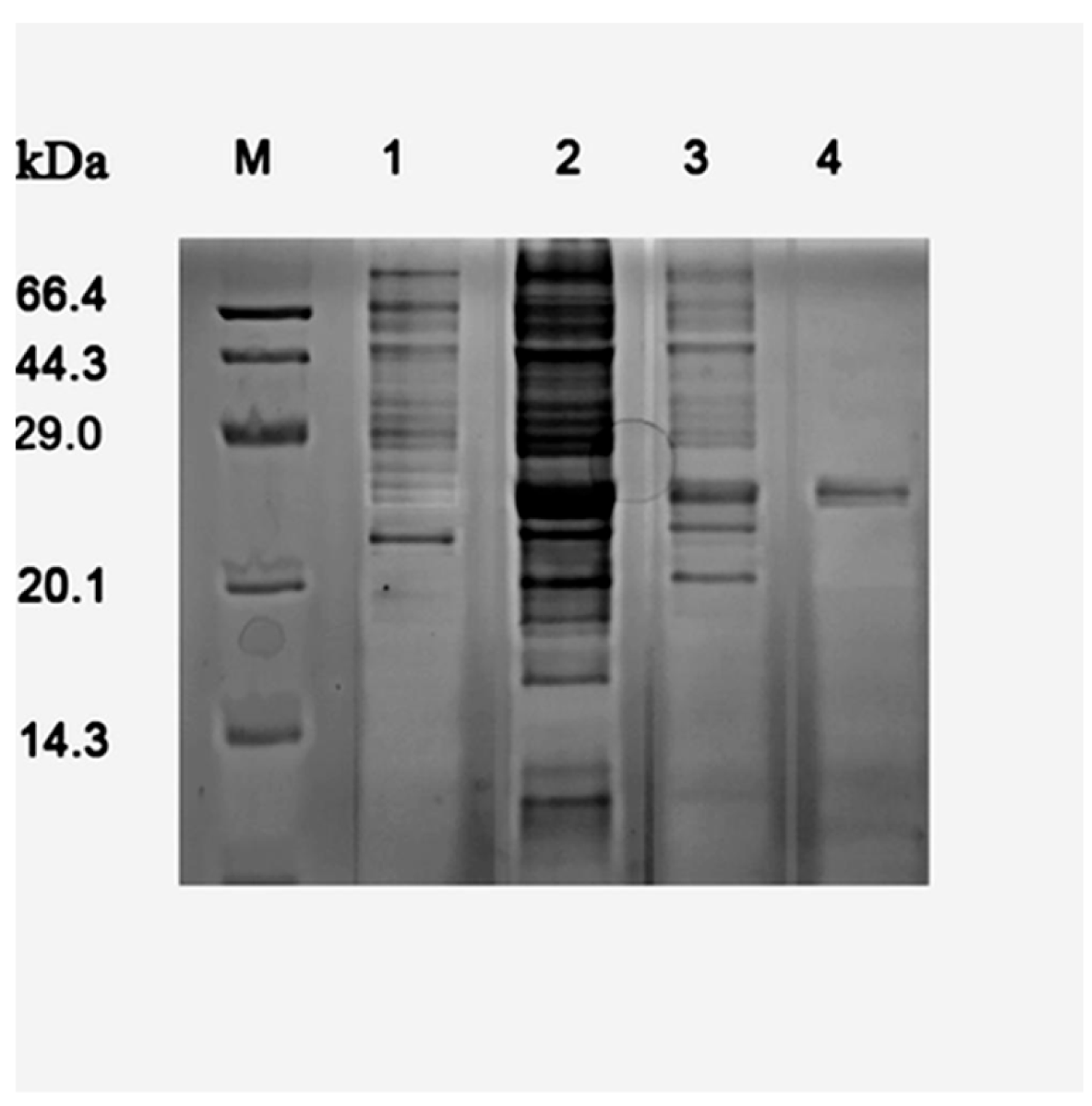

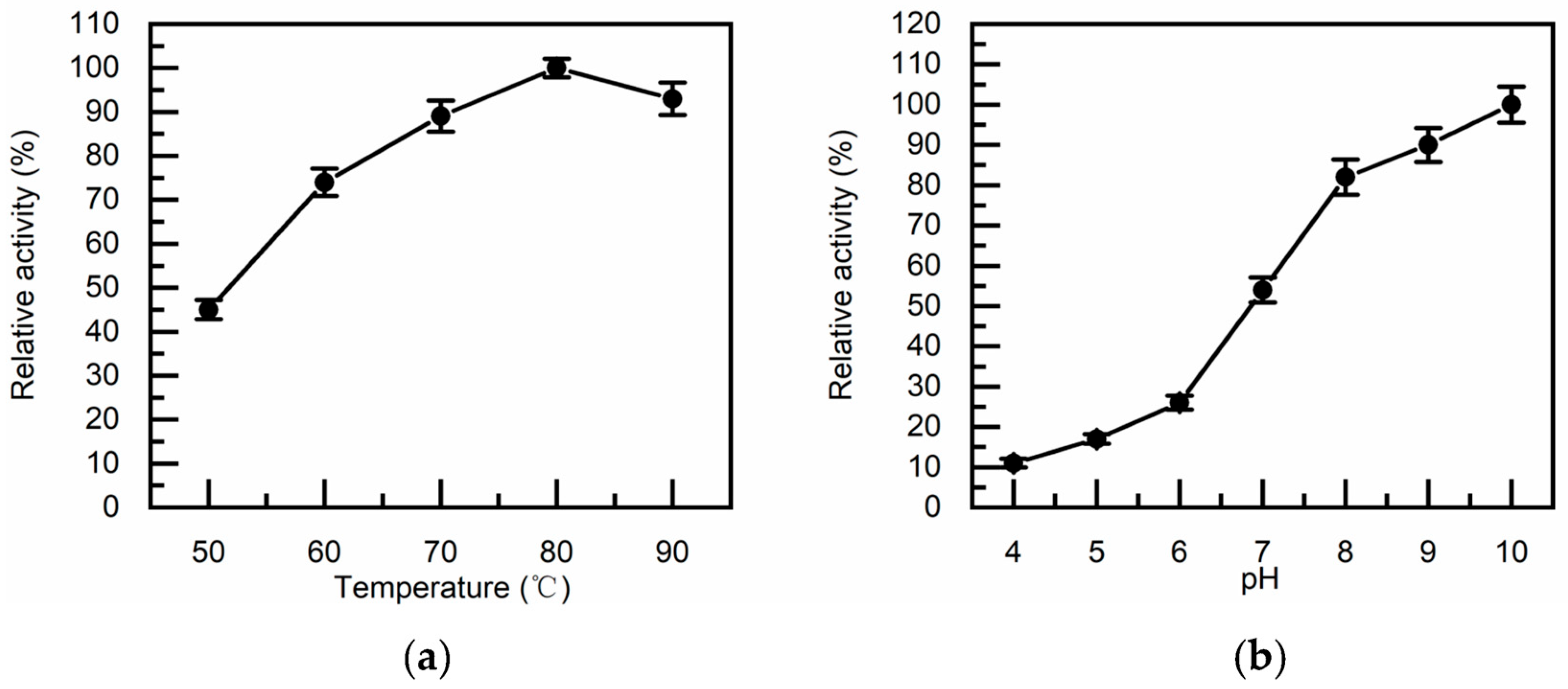

3.2. Recombinant Expression and Biochemical Characterization of TcDAEase

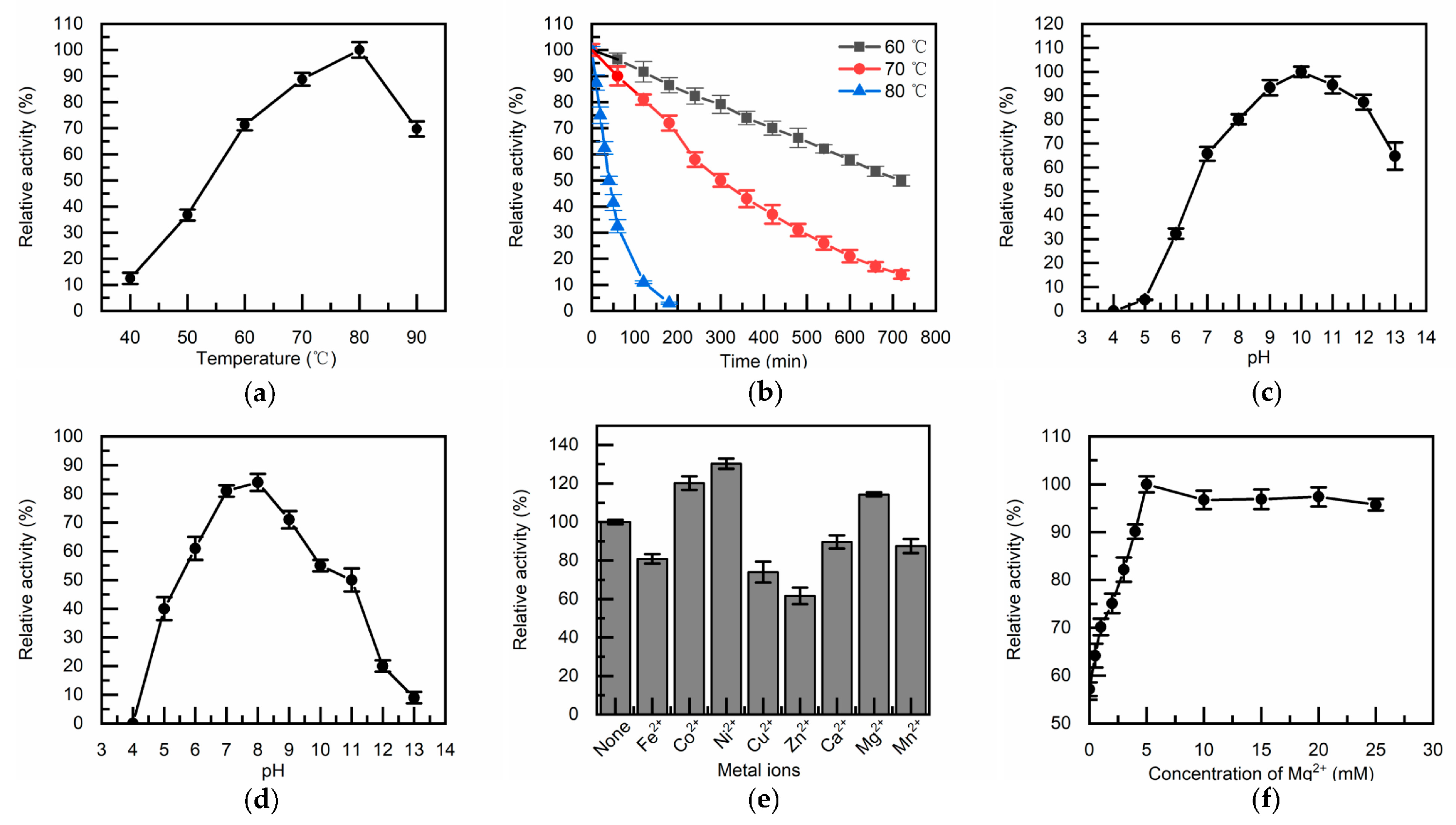

3.3. Thermostability, pH Tolerance and Metal Ion Dependence

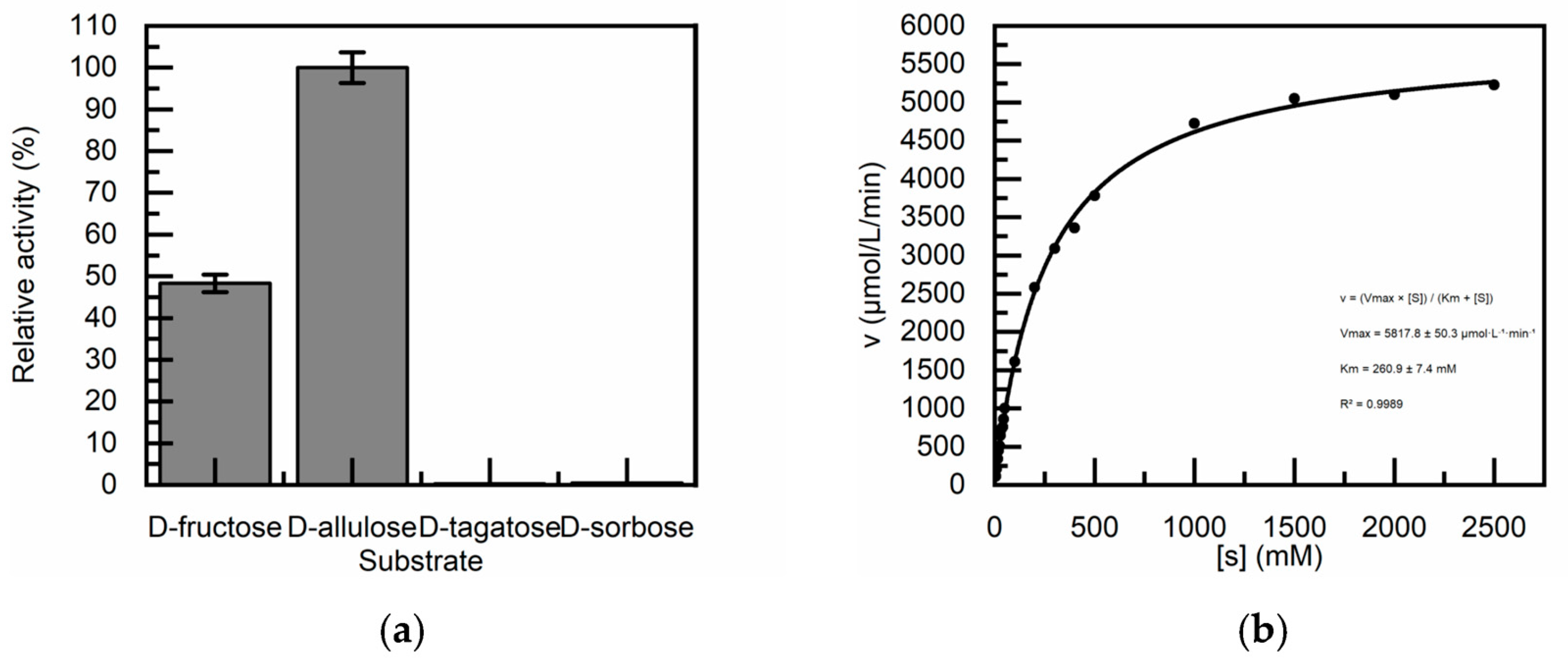

3.4. Substrate Specificity and Kinetic Parameters

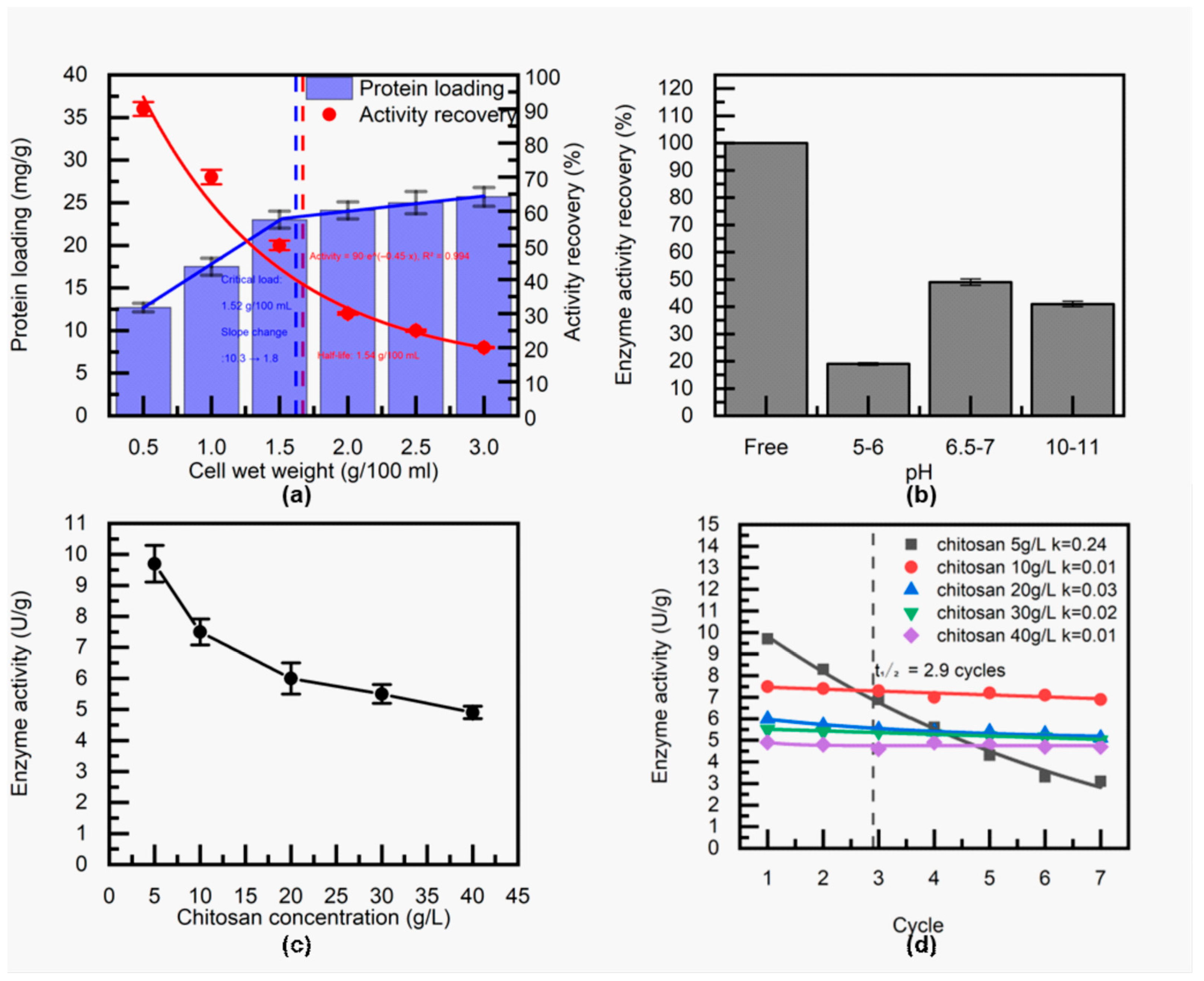

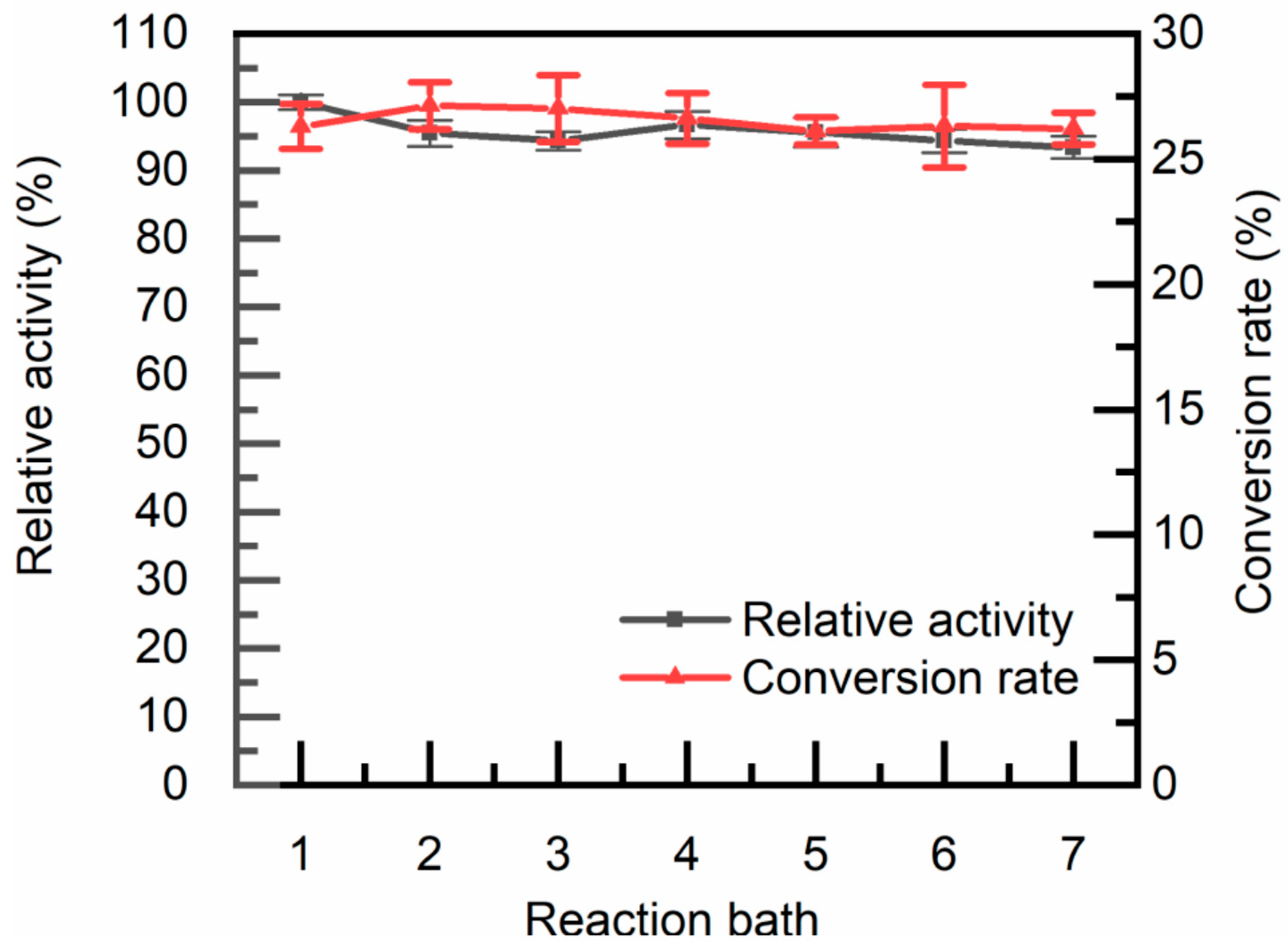

3.5. Immobilization Optimization and Stability Assessment of TcDAease

3.6. Biochemical Properties of the Immobilized TcDAEase

3.7. Long-Term Continuous D-Allulose Production in Packed-Bed Reactor

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ziade, F.; El-Kassas, G. Exploration of the Risk Factors of Generalized and Central Obesity among Adolescents in North Lebanon. J. Environ. Public Heal. 2017, 2017, 2879075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.; Blumberg, B.; Heindel, J.J.; Porta, M.; Govarts, E.; Legler, J.; Trasande, L. Obesity, Diabetes, and Associated Costs of Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in the European Union. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzo, G.; Monsan, P.; Mazarguil, H. [Mechanism of glutaraldehyde-protein bond formation]. Biochimie 1975, 57, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Guang, C.; Chen, D.; Xu, W.; Wu, H.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. D-allulose, a versatile rare sugar: recent biotechnological advances and challenges. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 63, 5661–5679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, T.; Zhao, G.; Lu, X. D-allulose attenuated metaflammation by calming adipose tissue macrophages, boosting intestinal barrier, and modulating gut microbiota in HFD mice. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, D.; Seino, Y.; Han, W.; Yermek, R.; Wang, L.; Kaneko, K.; Yada, T. D-Allulose cooperates with glucagon-like peptide-1 and activates proopiomelanocortin neurons in the arcuate nucleus and central injection inhibits feeding in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 613, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Tokuda, M.; Takehara, I.; Iida, T.; Okuma, K.; Hayashi, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamada, K. Study on the Postprandial Blood Glucose Suppression Effect ofD-Psicose in Borderline Diabetes and the Safety of Long-Term Ingestion by Normal Human Subjects. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beglinger, C.; Weltens, N.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Meyer-Gerspach, A.C.; Teysseire, F.; Bordier, V.; Budzinska, A.; Wölnerhanssen, B.K. Metabolic Effects and Safety Aspects of Acute D-allulose and Erythritol Administration in Healthy Subjects. Nutrients 2023, 15, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Guan, L.; Mao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, T.; Wei, M.; Qi, H.; Qin, H.-M. Engineering of Acid-Resistant d-Allulose 3-Epimerase for Functional Juice Production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 16298–16306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Sun, C.; Peng, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, K.; Cheng, X.; Chen, D. Advances on D - psicose and its synthesis. Food and Fermentation Industries 2021, 47, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Guan, L.; Qin, H.-M.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Lu, F. Two-step biosynthesis of d-allulose via a multienzyme cascade for the bioconversion of fruit juices. Food Chem. 2021, 357, 129746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Li, M.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, T.J.C.r.i.f.s.; safety, f. Bioproduction of D-allulose: Properties, applications, purification, and future perspectives. 2021.

- Yoshihara, A.; Izumori, K.; Ohtani, K.; Akimitsu, K.; Iida, T.; Matsutani, R.; Kozakai, T.; Gullapalli, P.K.; Shintani, T. Purification and characterization of d-allulose 3-epimerase derived from Arthrobacter globiformis M30, a GRAS microorganism. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 123, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, W.; Chu, F.; Zhou, L.L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, B.; Jia, M. A d-psicose 3-epimerase with neutral pH optimum from Clostridium bolteae for d-psicose production: cloning, expression, purification, and characterization. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 98, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Bai, W.; Zhang, L. Overexpression of d-psicose 3-epimerase from Ruminococcus sp. in Escherichia coli and its potential application in d-psicose production. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.N.; Kaushal, G.; Singh, S.P. A Novel d -Allulose 3-Epimerase Gene from the Metagenome of a Thermal Aquatic Habitat and d -Allulose Production by Bacillus subtilis Whole-Cell Catalysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Hussian, C.H.A.; Leong, W.Y.J. Thermostable enzyme research advances: a bibliometric analysis. 2023, 21. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2023, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.; Morgan, B.W.; Deitchman, S.; Devlin, J.J.; Brent, J.; Pomerleau, A.C. Clinical Features, Testing, and Management of Patients with Suspected Prosthetic Hip-Associated Cobalt Toxicity: a Systematic Review of Cases. J. Med Toxicol. 2013, 9, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Mu, W.; Hu, X.; Sun, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.J.F. Research Advances of d-allulose: An Overview of Physiological Functions, Enzymatic Biotransformation Technologies, and Production Processes. 2021, 10. Food 2021, 10, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tu, W.; Ji, Y.; Schwaneberg, U.; Ni, Y.; Guo, Y.; Han, R. Novel multienzyme cascade for efficient synthesis of d-allulose from inexpensive sucrose. Food Biosci. 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, F.; Fan, D.; Han, S. Designable immobilization of D-allulose 3-epimerase on bimetallic organic frameworks based on metal ion compatibility for enhanced D-allulose production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 133027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumori, K.; Takada, G.; Takeshita, K.; Suga, A. Mass Production of D-Psicose from D-Fructose by a Continuous Bioreactor System Using Immobilized D-Tagatose 3-Epimerase. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2000, 90, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumori, K.; Okaya, H.; Tsumura, T.; Khan, A.R. A New Enzyme,D-Ketohexose 3-Epimerase, fromPseudomonassp. ST-24. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1993, 57, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumori, K.; Ishida, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Itoh, H.; Kamiya, T. Cloning and characterization of the d-tagatose 3-epimerase gene from Pseudomonas cichorii ST-24. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1997, 83, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Hyun, E.-K.; Oh, D.-K.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, Y.-S. Characterization of an Agrobacterium tumefaciens d -Psicose 3-Epimerase That Converts d -Fructose to d -Psicose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.-H.; Jung, M.H.; Park, C.-S.; Kim, S.W.; Park, B.W.; Kim, H.-J.; Oh, D.-K.; Ko, M.; Yoon, K.-H. d-Psicose production from d-fructose using an isolated strain, Sinorhizobium sp. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 23, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L. Characterization of d-tagatose-3-epimerase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides that converts d-fructose into d-psicose. Biotechnol. Lett. 2009, 31, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Zhou, L.; Yu, S.; Chu, F.; Mu, W.; Jiang, B. Correction to Cloning, Expression, and Characterization of a d-Psicose 3-Epimerase from Clostridium cellulolyticum H10. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 10408–10408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Zhou, L.; Mu, W.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, T. Characterization of a d-psicose-producing enzyme, d-psicose 3-epimerase, from Clostridium sp. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013, 35, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Xing, Q.; Zhou, L.; Mu, W.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, B. Characterization of a Novel Metal-Dependent D-Psicose 3-Epimerase from Clostridium scindens 35704. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e62987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Zhou, L.; Mu, W.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, T. Characterization of a Metal-Dependent d-Psicose 3-Epimerase from a Novel Strain, Desmospora sp. 8437. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11468–11476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Mu, W.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, B.; Li, H.; Zhang, T. Characterization of a d-psicose 3-epimerase from Dorea sp. CAG317 with an acidic pH optimum and a high specific activity. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2015, 120, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, T. Biochemical characterization of a d-psicose 3-epimerase from Treponema primitiaZAS-1 and its application on enzymatic production of d-psicose. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 96, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Shin, K.-C.; Park, C.-S.; Kim, K.-R.; Hong, S.-H.; Oh, D.-K. D-Allulose Production from D-Fructose by Permeabilized Recombinant Cells of Corynebacterium glutamicum Cells Expressing D-Allulose 3-Epimerase Flavonifractor plautii. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0160044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.-Y.; Hsu, C.-T.; Wang, M.-J.; Chen, C.-N.; Lee, H.-C.; Fang, H.-Y.; Wu, Y.-H.; Tseng, W.-C. Characterization of a recombinant d-allulose 3-epimerase from Agrobacterium sp. ATCC 31749 and identification of an important interfacial residue. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Ren, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tian, C.; Yang, J. Development of food-grade expression system for d-allulose 3-epimerase preparation with tandem isoenzyme genes in Corynebacterium glutamicum and its application in conversion of cane molasses to D-allulose. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 116, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guang, C.; Mu, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, S. Characterization of a d-tagatose 3-epimerase from Caballeronia fortuita and its application in rare sugar production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustriana, E.; Nuryana, I.; Nirwantono, R.; Laksmi, F.A. Expression and characterization of thermostable D-allulose 3-epimerase from Arthrobacter psychrolactophilus (Ap DAEase) with potential catalytic activity for bioconversion of D-allulose from d-fructose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 214, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Tang, X.; Cong, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ravikumar, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, H.; Qi, X.; Iqbal, M.W.; et al. The Characterization of a Novel D-allulose 3-Epimerase from Blautia produca and Its Application in D-allulose Production. Foods 2022, 11, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid; Thakur, A.; Gautam, S.; Kathuria, D. Maillard reaction in different food products: Effect on product quality, human health and mitigation strategies. Food Control. 2023, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulminskaya, A.A.; Ivanova, N.S.; Shvetsova, S.V. Structural and Functional Features of Ketose-3-Epimerases and Their Use for D-Allulose Production. Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2023, 49, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.-H.; Zheng, L.-J.; Luo, X.; Liu, C.-Y.; Gao, X.-Q.; Zheng, H.-D.; Guo, Q.; Deng, L. Engineering Escherichia coli for d-Allulose Production from d-Fructose by Fermentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 13578–13585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.-X.; Zheng, L.-J.; Luo, X.; Guo, Q.; Zheng, H.-D.; Fan, L.-H. Engineering Escherichia coli for D-allulose biosynthesis from glycerol. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 394, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Qin, H.-M.; Wei, C.; Li, C.; Gao, X.; Qi, H. Directional immobilization of D-allulose 3-epimerase using SpyTag/SpyCatcher strategy as a robust biocatalyst for synthesizing D-allulose. Food Chem. 2022, 401, 134199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejar, S.; Plou, F.J.; Bouanane-Darenfed, A.; Ballesteros, A.O.; Neifar, S.; BenHlima, H.; Cervantes, F.V. Immobilization of the glucose isomerase from Caldicoprobacter algeriensis on Sepabeads EC-HA and its efficient application in continuous High Fructose Syrup production using packed bed reactor. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, L.F.; Por, L.Y.; Yam, M.F. Study on Different Molecular Weights of Chitosan as an Immobilization Matrix for a Glucose Biosensor. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e70597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Salmon, S.; Yuan, Y. Developing Enzyme Immobilization with Fibrous Membranes: Longevity and Characterization Considerations. Membranes 2023, 13, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, W.; Wolynes, P.G.; Li, W.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y. Frustration and the Kinetic Repartitioning Mechanism of Substrate Inhibition in Enzyme Catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 6792–6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorza, B.; Arias, C.; Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Acosta, N.; Caballero, A.H.; Civera, M.C. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, C.; Christensen, B.E.; Bourasseau, S.; Courtecuisse, E. Synthesis of linear chitosan-block-dextran copolysaccharides with dihydrazide and dioxyamine linkers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 345, 122576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da S Pereira, A.; Souza, C.P.L.; Moraes, L.B.D.d.; Fontes-Sant’Ana, G.C.; Amaral, P.F.F.J.P. Polymers as Encapsulating Agents and Delivery Vehicles of Enzymes. Polymers 2021, 13, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, M.R.; Hunt, A.J.J. Synthesis and properties of chitosan–silica hybrid aerogels. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2001, 285, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, F.; Han, S.; Lin, Y.; Fan, D. Characterization of D-Allulose-3-Epimerase From Ruminiclostridium papyrosolvens and Immobilization Within Metal-Organic Frameworks. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 869536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, C.; Shao, W.; Sadaqat, B.; Dhanavade, M.J.; Sonawane, K.D.; Mohamed, H.; Song, Y.; Dar, M.A. Modifying Thermostability and Reusability of Hyperthermophilic Mannanase by Immobilization on Glutaraldehyde Cross-Linked Chitosan Beads. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorla, R.; Murthy, P.; Beg, O.A.; Ray, A.K.; B, V. Magneto-bioconvection flow of a casson thin film with nanoparticles over an unsteady stretching sheet. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2019, 29, 4277–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain of enzyme source | Optimal temperature (°C) |

Optimal pH | Metal ion | Half-life | Catalytic activity (U/mg) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. | 60 | 7.0-9.0 | NR | NR | NR | [23] |

| Pseudomonas cichorii | 60 | 7.5 | NR | NR | NR | [24] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | 50 | 8.0 | Mn2+ | 63.5 min/50 °C | 8.89 | [25] |

| Sinorhizobium sp. | 40 | 8.5 | Mn2++ | 11050 min/35 °C, 934 min/40 °C, 251 min/45 °C, 1151 min/50 °C |

NR | [26] |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | 40 | 9.0 | Mn2+ | NR | NR | [27] |

| Clostridium cellulolyticum | 55 | 8.0 | Co2+ | 408 min/60 °C | NR | [28] |

| Ruminococcus sp. | 60 | 7.5-8.0 | Mn2+ | 96 min/60 °C | 8.95 | [15] |

| Clostridium sp. | 65 | 8.0 | Co2+ | 15 min/60 °C | NR | [29] |

| Clostridium scindens | 60 | 7.5 | Mn2+ | 108 min/50 °C | NR | [30] |

| Desmospora sp. | 60 | 7.5 | Co2+ | NR | NR | [31] |

| Clostridium bolteae | 55 | 7.0 | Co2+ | 156 min/55 °C | NR | [14] |

| Dorea sp. | 70 | 6.0 | Co2+ | NR | 803 | [32] |

| Treponema primitia | 70 | 8.0 | Co2+ | 30 min/60 °C | NR | [33] |

| Flavonifractor plautii | 65 | 7.0 | Co2+ | 40 min/65 °C | 20 | [34] |

| Arthrobacter globiformis | 70 | 7.0-8.0 | Mg2+ | NR | 23.6 | [13] |

| Agrobacterium sp. | 55-60 | 7.5-8.0 | Co2+ | 267 min/55 °C, 28.2 min/60 °C,, 3.8 min/65 °C |

90.5 | [35] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | 55 | 8.0 | Mn2+ | 140 min/60 °C | 22.7 | [36] |

| DaeM | 80 | 7.0 | Co2+ | 9900 min/60 °C, 3240 min/70 °C, 49 min/80 °C |

1.14 ± 0.048 | [16] |

| Caballeronia fortuita | 65 | 7.5 | Co2+ | 427.8 min/50 °C, 307.8 min/55 °C, 63 min/60 °C |

270 ± 1.5 | [37] |

| Arthrobacter psychrolactophilus | 70 | 8.5 | Mg2+ | 128.4 min/70 °C | 14.3 | [38] |

| Blautia produca | 55 | 8.0 | Mn2+ | 180 min/55 °C | 1.76 ± 0.099 | [39] |

| Thermogemmatispora carboxidivorans | 80 | 10.0 | Ni2+ | 720 min/60 °C, 300 min/70 °C, 40 min/80 °C |

7.9 ± 0.3 | This work |

| Enzyme source (strain) | kcat (s⁻¹) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (s⁻¹·mM⁻¹) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | 34.46 ± 0.46 | 24 ± 0.15 | 1.41 ± 0.02 | [25] |

| Clostridium cellulolyticum | 55.91 ± 0.787 | 53.5 ± 1.8 | 1.045 ± 0.025 | [28] |

| Ruminococcus sp. | 59.4 ± 0.483 | 216 ± 2 | 0.267 ± 0.017 | [15] |

| Clostridium sp. | 272.87 ± 1.37 | 279 ± 10.8 | 0.978 ± 0.065 | [29] |

| Clostridium scindens | 5.83 ± 0.43 | 40.1 ± 2.5 | 0.145 ± 0.02 | [30] |

| Clostridium bolteae | 59 ± 1 | 59.8 ± 8.2 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | [14] |

| Dorea sp. | 5507.45 | 153 | 3.31 | [32] |

| Treponema primitia | 292.88 ± 6.48 | 279 ± 20.7 | 1.05 ± 0.097 | [33] |

| Flavonifractor plautii | 225280 | 162 | 156 | [34] |

| Arthrobacter globiformis | 41.8 | 37.5 | 1.12 | [13] |

| Agrobacterium sp. | 106.7 | 110 | 1.06 | [35] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | 40.92 ± 0.175 | 366.7 ± 10.5 | 0.11 ± 0.077 | [36] |

| Bacillus subtilis | 41.99 ± 2.3 | 141.43 ± 7.5 | 0.29 ± 0.09 | [16] |

| Caballeronia fortuita | 157.21 ± 0.53 | 81.9 ± 4.3 | 1.30 ± 0.12 | [37] |

| Arthrobacter psychrolactophilus | 2920 | 738.7 | 3.953 | [38] |

| Blautia produca | 65.03 ± 3.56 | 235.7 ± 9.938 | 0.28 ± 0.014 | [39] |

| Thermogemmatispora carboxidivorans | 96.6 ± 0.5 | 260.9 ±7.4 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).