2. Literature Review

The early Ornithopters were developed for the manned flight. The initial work was carried out on the feathers that could be used to make wings for a man to fly and published in Chinese

Book of Han in 19 AD [

3]. Leonardo da Vinci, who studied the flight of birds for the first time and considered to be a pioneer in flapping wing flight, in order to imitate the bird flight, he sketched the design that could be used instead of the flying using the wings attached to the arms. No proper flapping flight was performed until 1929, in which the first successful manned flapping wing flight was achieved. Lippisch, a German engineer, was the first person to achieve the flight driven solely by the muscles of the pilot [

4]. The flights were successful, but the Ornithopter did not have enough wing area, the bird could not fly for greater distance. Fig.2.3. shows the Lippisch manned Ornithopter flight.

After one-year Lippisch and his students manufactured many unmanned Ornithopters with power generated by engine. These were experimentally tested and the longest flight time obtained was 16 minutes. In 1942, Schmidt fabricated a small human-powered flapping wing Ornithopter capable of flying 900 meters at a constant height [

5]. After 5 years, Schmidt built a double seater Ornithopter with the speed range of 100 to 120 kilometers per hour [

6].

Figure 3 shows the Schmidt’s Ornithopter constructed in 1947 [

6].

In 1993, DeLaurier constructed an ornithopter wing and tested it for flexibility to be used os a flappin wing [

7] this wing was used in fabrication of an ornithopter subsequently as shown in

Figure 4. DeLaurier gave a complex aerodynamics model for flapping wing aircraft which is still applicable on the micro-sized aircraft.

The bird sized aircrafts were started to be constructed during the era of Lippisch. Erich von Holst constructed rubber powered ornithopters and obtained greater efficiency. The model proposed by Eric resembled more closely to the natural birds [

8]. In addition to this there are multiple of bird sized aircrafts available in the literature. In 1930, ornithopters were developed that were compressed air powered. These ornithopters, were bird like in shape and developed by Vincenz Chalupsky [

9]. 1958, Percival Spencer manufacture bird shaped ornithopters driven by engines [

10]. Sean Kinkade started a small-scale commercial production of remotely controlled ornithopter [

8]. Some more designs were developed by several other engineers, that include RoboFalcon ornithopters specifically manufactured to chase the flock of birds [

12] is remote controlled (RC) bird is commercially available for customers and foam made RC ornithopters close to the real bird were developed by Robert Musters in order to control the natural birds at airports [

8]. Recently, Festo AG developed an ornithopter, named SmartBird with bending wing capabilities. The flier is controlled via radio and the motion of a seagull is imitated in the design. It only weighs 450 grams and its flight shows remarkable resemblance with nature [

13].

Figure 5.

Festo Smart Bird [

13].

Figure 5.

Festo Smart Bird [

13].

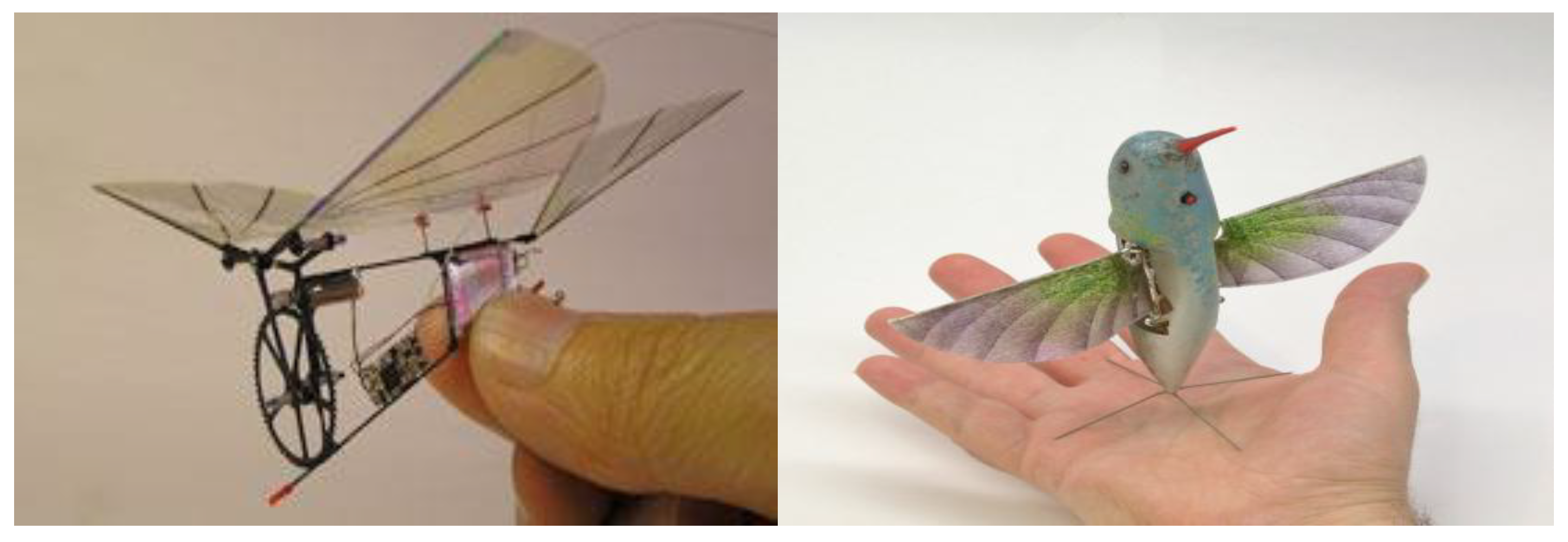

Some micro ornithopters are capable of carrying camera as payload, thus allowing to be used as spy in buildings and remote areas. The idea is to obtain a flapping wing aircraft so small that it resembles the same to insects and small birds. In 1998, Aerovironment & Caltech developed the first micro aerial vehicle (MAV) ornithopter, named MicroBat [

14]. It is of the size of a palm as shown in

Figure 6. Till 2002, no hovering flight was achieved for a MAV ornithopter, when the first hovering ornithopter was developed at University of Toronto [

15]. In 2006, scholars at the Technical University of Delft and Wageningen University developed Delfy, which is capable of forward and hovering transition during flight [

16]. It is also equipped with small video camera thus giving the autonomous navigation ability to the ornithopter]. Nathan Chronister manufactured an ornithopter that can hover and perform quick maneuvers for recreational use in 2007. The size and weight of the ornithopter was same to that of real hummingbird, the smallest bird in the world [

8]. However, the quest of miniaturizing wasn’t over yet. In the same year Petter Muren constructed the world’s smallest ornithopter, which was controlled via radio [

17]. It has the span of 10 cm and weight of 1 gram only. Another huge breakthrough in the field of MAV was the development of Aerovironment’s Nano Hummingbird in 2010, because of its stabilized flight without any tail. The wing was allowed to rotate about 3 axes thus allowed maximum maneuverability capabilities [

18].

For the successful flight of an aircraft, the initial design and analytical working is necessary. For this purpose, the important parameters & performance optimization techniques were studied. Experiments were performed using a motion-tracking technique on free-flying

Drosophila to obtain three-dimensional wing trajectories. Similarly, Walker, Thomas, and Taylor [

19] measured the complete wing trajectories of locusts and hoverflies in a low-speed closed-loop wind tunnel. The experiments were performed on three different desert locusts in order to obtain the important dynamics parameters [

20]. Grätzel [

21] also conducted experiments on

Drosophila using a high-speed camera to capture the flapping motion of the wings. Zhang et al. [

22] employed a Planar Single-Crank Double-Rocker mechanism, developed using ADAMS modeling software, to define the wing motion. Experiments by Ellington [

23] and Ennos [

24] demonstrated that wing motion follows a simple harmonic function. Harijono et al. [

25] developed a kinematic and aerodynamic model by assuming the thin wing to be rigid and the motion to be three-dimensional. Benjamin Y. Leonard [

26] divided the wing kinematics into three motions, that were rotation about each axis and considered the motion to be sinusoidal, however, with some offset and phase lag between the rotations as obtained experimentally. Another scholar, Bierling [

27] assumed the fuselage of ornithopter to be rigid and the wings were attached at a single rotating joint that move with the required motion. Spline interpolation method was used to observe the wing kinematics data, which was further used to obtain the equations of motion of ornithopter. Whitney and R.J. Wood [

28] performed passive-rotation flapping experiments artificial wings driven mathematically to measure the kinematics. This was further used to develop the blade-element aerodynamics model of the flapping wings. Jackson and Bhattacharya [

29] derived the equations of motion of flapping using Eulerian Method. The central body was considered to be a point mass so that the hinges of both the wings was the same and placed at the central body. Two frames of references were used, one for each wing. This estimation eliminated the rotational motion of the central body.

The aerodynamic performance of a flapping wing aircraft cannot be completely defined by conventional aerodynamic theories due to the continuously varying flow field [

30]. Scientists and biologists performed multiple of experiments to understand the flow phenomena around a flapping wing of natural bird. Many experiments were performed to obtain the effects of various parameters on the aerodynamics of already developed flapping wing aircrafts. As a result of these experiments many empirical relations and models for lift and thrust calculation have been generated, so that these models could be used effectively in analytical study of flapping motion. Analytical modelling for the aerodynamics of flapping wing can be categories into Quasi-steady and Unsteady aerodynamics. If the flapping frequency is low, quasi-steady approach can be applied as it ignores the wake effects and for high flapping frequency unsteady aerodynamics is used as it includes the wake effects.

The wing's complex structure also makes it difficult to understand the inertial forces and moments that play dominant role in determining the lift and thrust. Till now a number of attempts have been made to model the aerodynamics of flapping wing air vehicles. Hui Hu et al [

31] performed experiments for aerodynamic performance of flexible membrane wings and discussed the flexibility effect of wings on aerodynamics. Similarly, Fry et al. [

32] performed experiments on Drosophila and studied the kinematics and aerodynamics of bird. For this purpose, they used high speed infrared camera that was capable to capture kinematics for measuring the aerodynamic forces produced due to flapping.

There are several modeling techniques developed by many researchers and scholars, which may include blade element theory, momentum theory, lifting line theory and lifting surface theory, as classified by Smith et al [

33]. Out of these theories, Blade element theory was implemented by DeLaurier [

34] and Wei. Shy [

35] in their ornithopter models. Dae-Kwan Kim et al [

36] studied the aeroelastic analysis of a flexible flapping wing. The model used by them was modified strip theory with the high relative angle of attack and dynamic stall effects inclusion. Guji and Garcia [

37] studied the distribution of forces on morphing wing aircrafts during the turning flight. Peters and his team [

38] used the finite state model in order to obtain the aerodynamic forces and moments by improving the classical aerodynamics model of Theodersen [

39].

Using the modified strip theory M.Y. Zakaria [

40] developed an aerodynamics model and applied the model on commercially available Ornithopters previously done by the flyers considered in their study include

SlowHawk 2 and

Pterosaur Replica. In addition to these two biological flyers are also taken into account including

Corvus monedula and

Larus canus. These birds and ornithopters were previously studied by Daniel

et al [

41]. He investigated the aerodynamics parameters. Valiyff

et al [

42] performed wind tunnel testing on two commercially available ornithopters at low speed at different free stream velocities and flapping frequencies to verify the developed aerodynamics model based on blade element theory.

The final step in analytical modeling is the development of equations of motion of flapping wing aircraft. Very few engineers and scholars have worked to develop the control theory of ornithopter. Bierling [

27], as described before considered the fuselage as rigid body with the wings attached a single joint and presented the complete flight dynamics model for an ornithopter with high flapping frequencies. The aerodynamics model used in the dynamics was the quasi-steady model developed by Fry et al. [

32]. Similarly, Taylor

et al. [

19] examined the desert locust flight and established a fact that this motion confirms the rotary flight due to mass oscillations. Meirovitch [

43] used a system of multi-bodies to obtain the equations of motion for an aircraft using the kinematics, structural parameters and aerodynamics of aircraft. Meirovitch obtained six degrees of freedom system and proposed the solution. Deng et al. [

44] studied the motion of micro aerial flapping wing vehicles and developed the mathematical model of its motion. Focus was given to the difference between fixed wing and flapping wing dynamics. The analytically derived equations were then used to form the algorithms for body dynamics which was then introduced to the wing aerodynamics model, actuator dynamics and the environmental factors in order to make up

Virtual Insect Flight Simulator (VIFS). Some engineers and scientists have worked on the hovering capabilities of an ornithopter and developed equations of motion. Faruque and Humbert [

45] developed the longitudinal hovering dynamics of a flapping insect. Quasi-steady aerodynamics given by Fry et al. [

32] was used with additional hovering parameters after considering the body to be rigid. In the similar manner they studied and developed the lateral equations of motion for the hover flight. The study was carried out for the longitudinal and lateral control of a flying insect. Jared Grauer et al. [

46] used the visual tracking system and obtained the wing trajectory while the ornithopter under consideration was in straight and mean flight. Using the multi-body dynamics, they investigated the kinematics variables and system identification techniques to obtain the aerodynamics model equations of motion. Orlowski [

47] derived the dynamics equations of a flapping wing aircraft by considering rigid wings attached to the rigid body. A study validating the use of 3D-printed aircraft models in subsonic wind tunnels confirmed that additive manufacturing can offer not only quick prototyping but also accurate performance replication [

48]. This approach aligns with the modular and repairable design adopted in our bird-sized flapping wing aircraft, where interchangeable parts like wing spars and faceplates enhance field usability and adaptability. Manufacturing accuracy also plays a direct role in aerodynamic performance. An experimental investigation used point cloud and surface deviation analysis to evaluate discrepancies between the CAD model and actual wing surfaces [

49]. Applying this methodology in ornithopter fabrication can ensure geometric precision in critical aerodynamic surfaces like wings and tail, improving lift symmetry and thrust uniformity during testing and flight.

Recent progress in machine learning and artificial intelligence has brought notable improvements to the field of aerodynamic design and optimization, especially for flapping-wing UAVs. Techniques like convolutional neural networks, generative adversarial networks, and reinforcement learning have enhanced turbulence prediction by approximately 20%, while also significantly cutting down the computational resources and time typically required by conventional CFD methods, which often struggle with capturing complex turbulent flows [

50]. These AI-based methods support automated, multi-objective aerodynamic optimization, allowing for rapid refinement of wing shapes and motion patterns that are essential for efficient flapping flight. Furthermore, adaptive neural networks have proven highly effective in nonlinear aerodynamic challenges, including real-time shape optimization, drag minimization, and enhancing flight efficiency in both commercial and military aerospace applications. These networks help accelerate the design process, improve fuel economy, and increase overall system safety, indicating their strong potential to transform the design and operation of bio-inspired flapping wing UAVs [

51].

3. Materials & Methods

The conceptual design of the ornithopter was developed based on initial design parameters using empirical relations proposed by Wei Shyy [

35]. In addition to geometric parameters, key characteristics such as wingspan, mass, wing surface area, root chord, and flapping frequency were also determined [

35]. After the series of experiments, effects of different parameters are studied on the flight characteristics [

35]. Wing area, airspeed, density and wing loading are interconnected and are related as follows:

Span is approximated to be 1m and on the basis of the span further estimations are made.

| Mass: |

m = (0.85×b) 2.56

|

| |

m = 0.66 kg |

| Wing Area: |

S = 0.16×m0.72

|

| |

S = .1186 m2

|

| Root Chord: |

c = (8×S)/(b×π) |

| |

c = .305 m |

| Flapping Frequency: |

f = 3.87×m−0.33; f = 4.439 Hz |

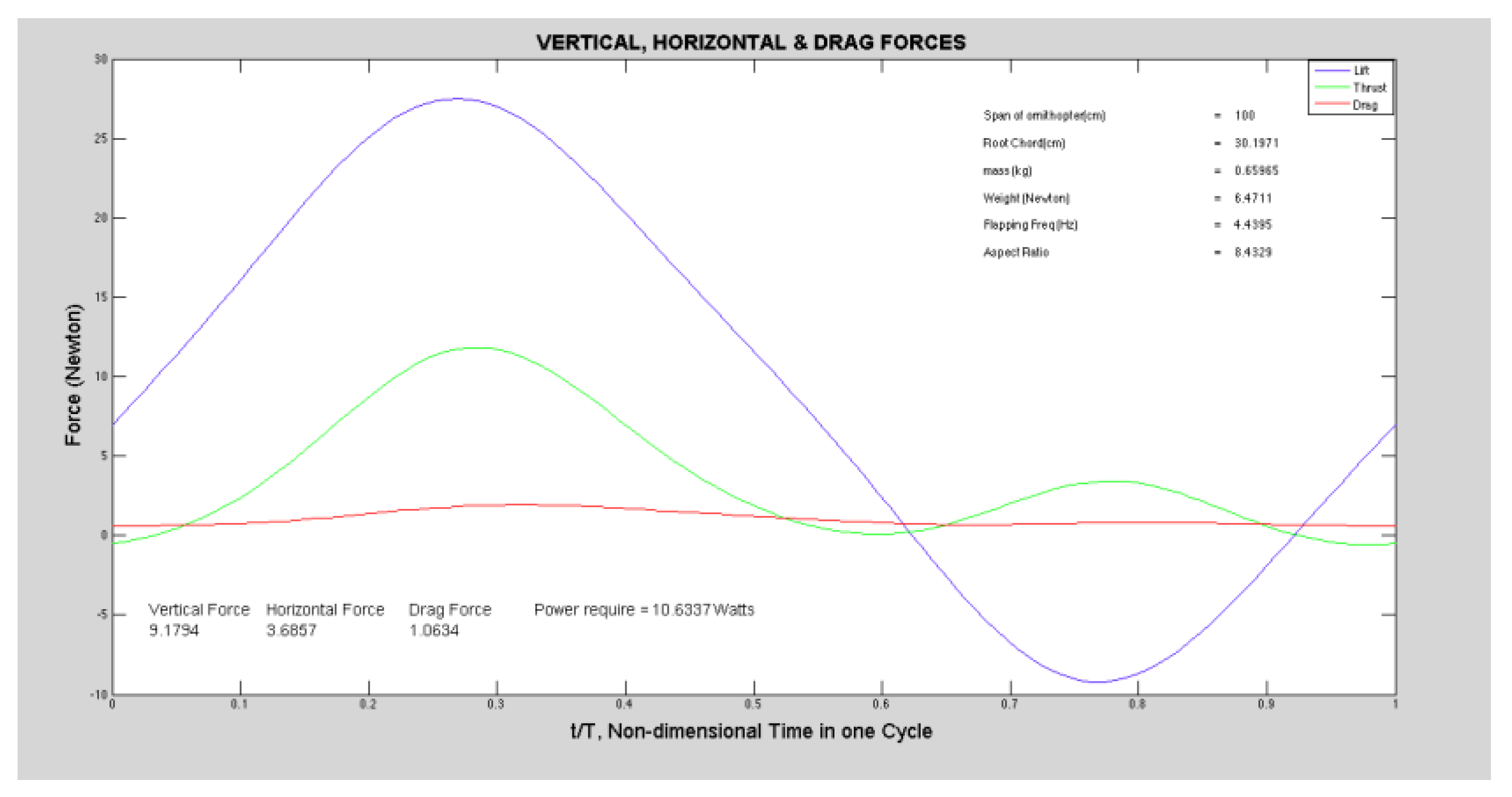

In summarized form these parameters are tabulated in

Table 1.

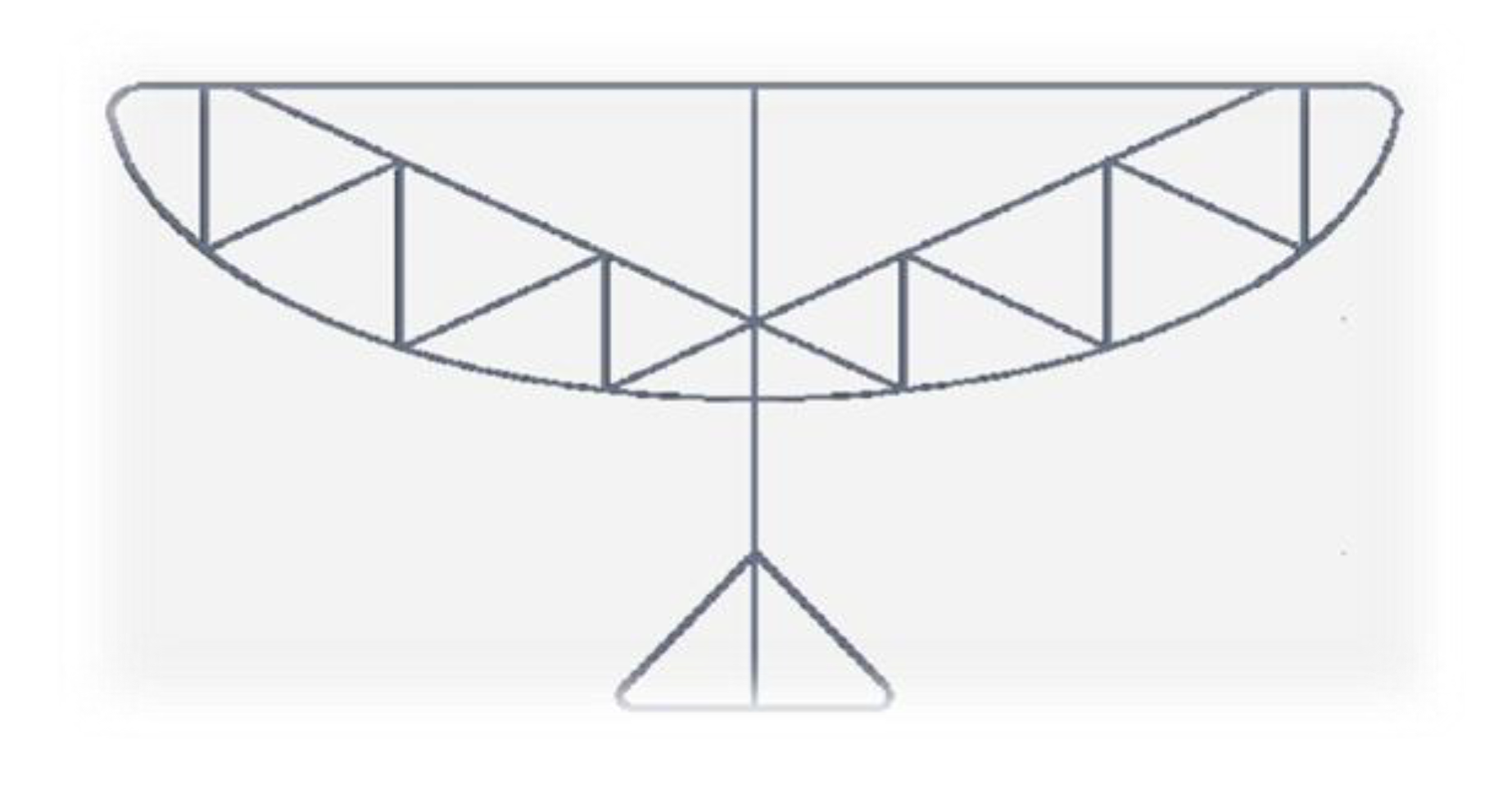

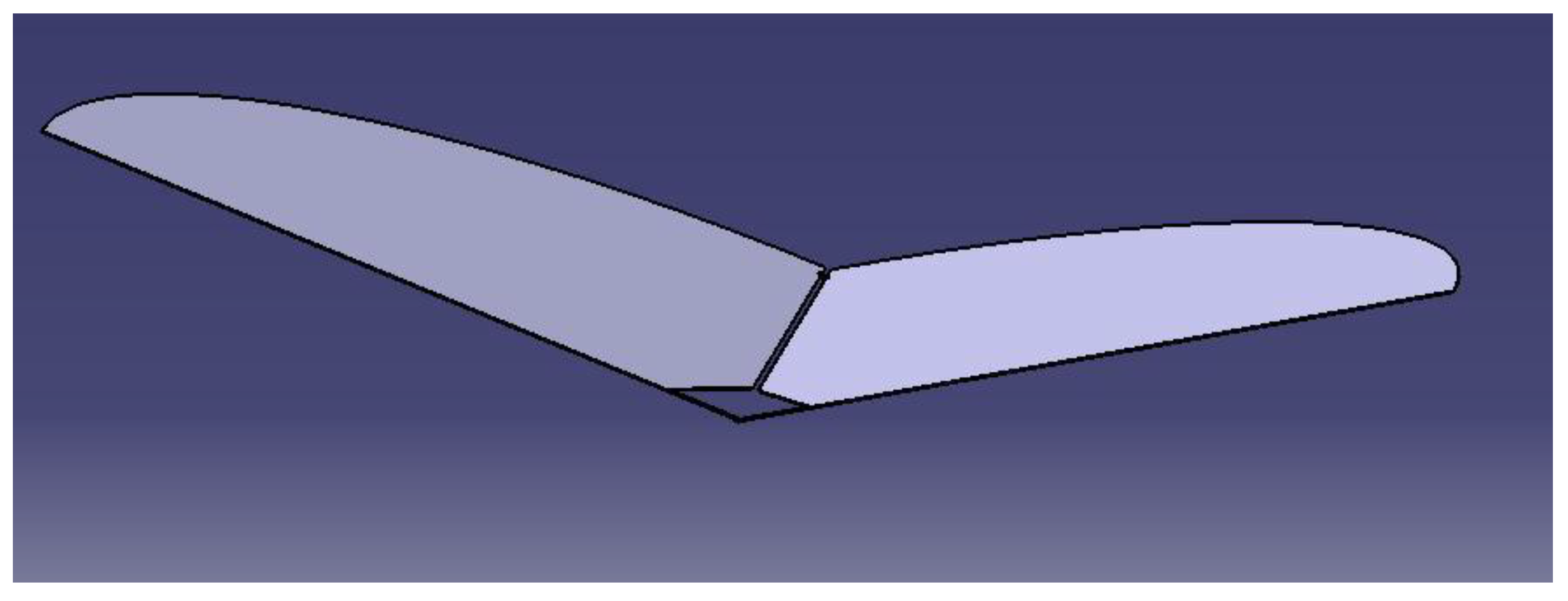

The Kinkade’s Bird Hawk is selected for this study and proposed its geometric parameters as per the requirement. A detailed design of wing and tail are drawn on CATIA based on the proposed parameters that are given in

Table 2.

The ornithopter is modeled on the software CATIA On the basis of geometric parameters CATIA design is made and is shown in

Figure 7 This shows a rough sketch of the design according to the dimensions.

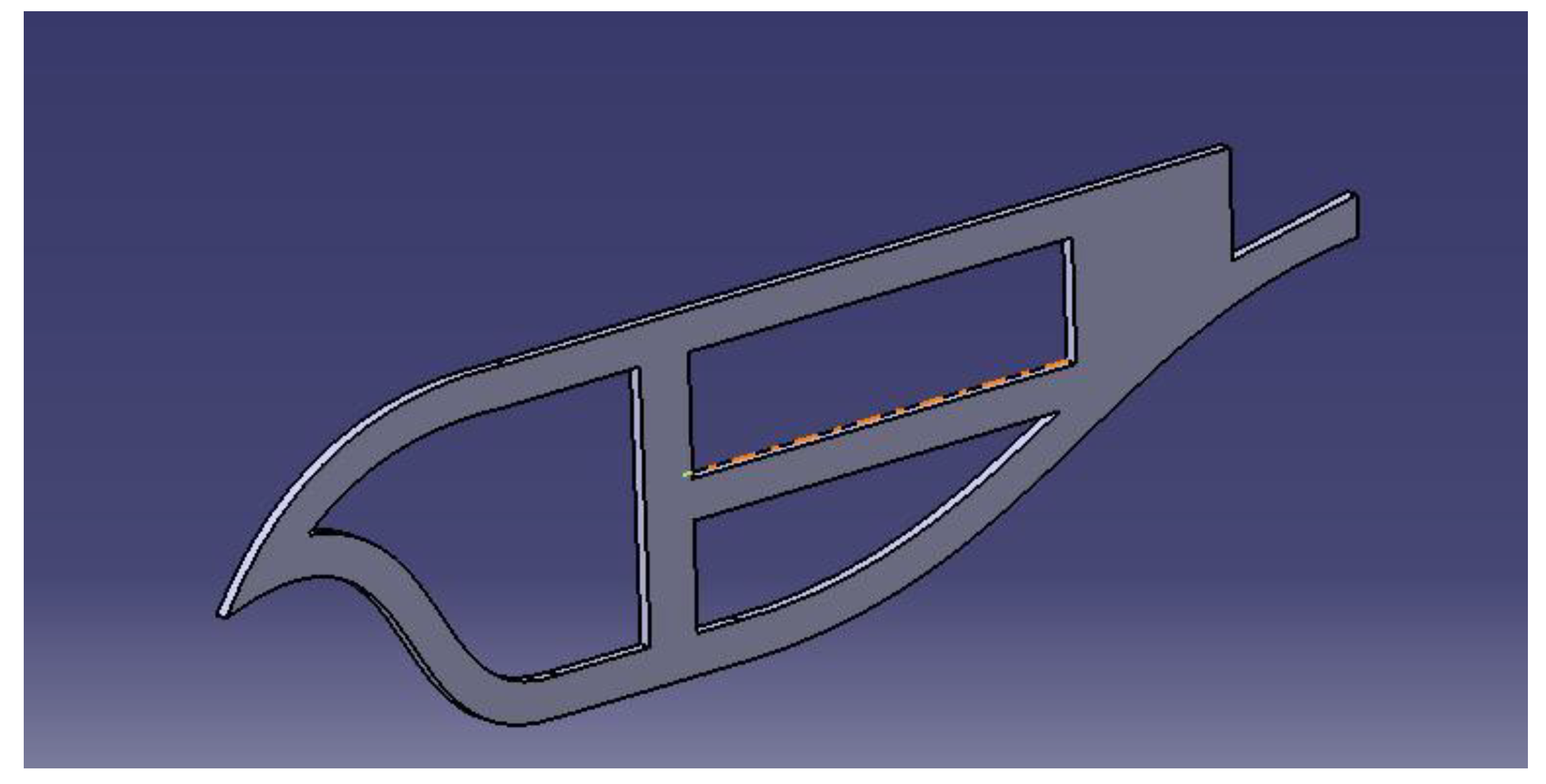

Fuselage is designed according to gear assembly diameter and the length of the ornithopter and is shown in

Figure 8. Fuselage specifications are shown in

Table 3.

Wings are the source of lift and thrust generation so they need to be designed to fulfill these criteria. Wings are designed in such a way that the central portion is stretched and tight whereas the outer portion is flexible. Primary, secondary and tertiary spars are arranged. Arrangement of tertiary spars is the critical part, which allows the flexion in the wing. For the visualization and to use it in the fabrication process the CATIA design is shown in

Figure 9.

Table 4.

Wings Specifications.

Table 4.

Wings Specifications.

| Parameters |

Values |

| Span |

100 cm |

| Root Chord |

30.5 cm |

| Primary Spar |

50 cm |

| Sec. Spar |

46.16 cm |

| Area |

1186 cm2

|

| Aspect Ratio |

8.348 |

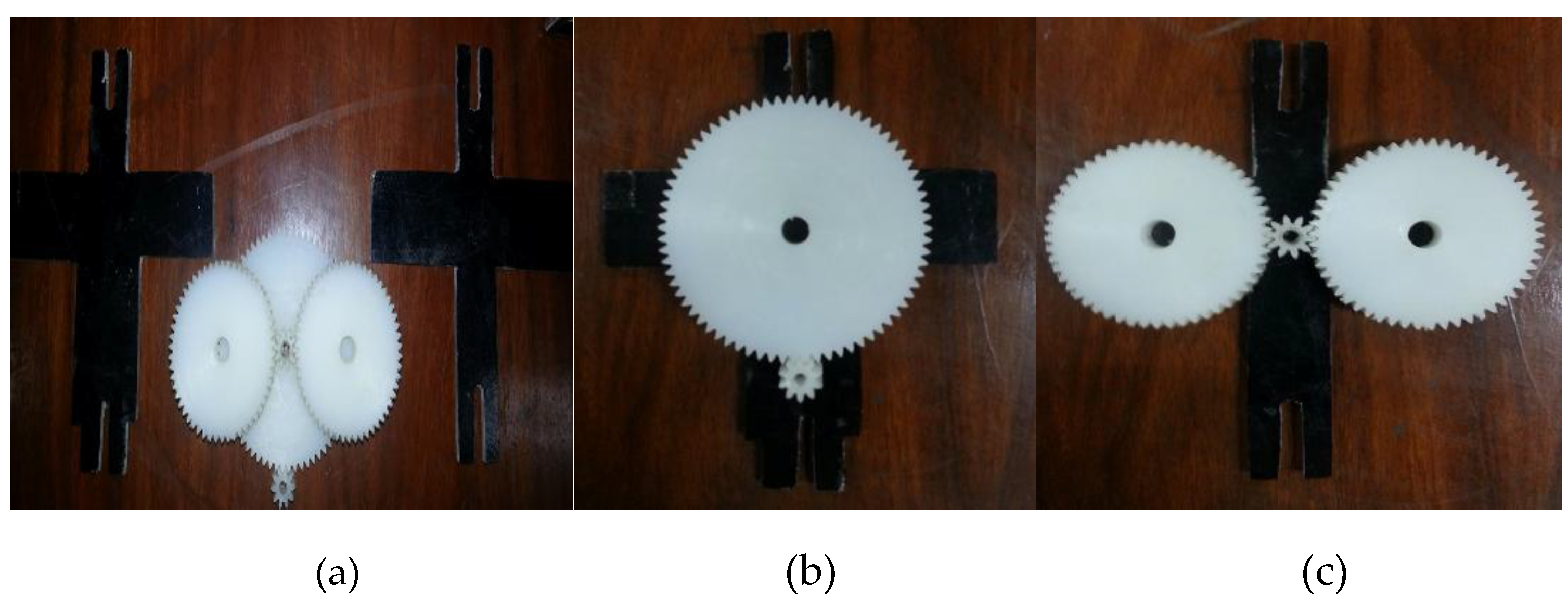

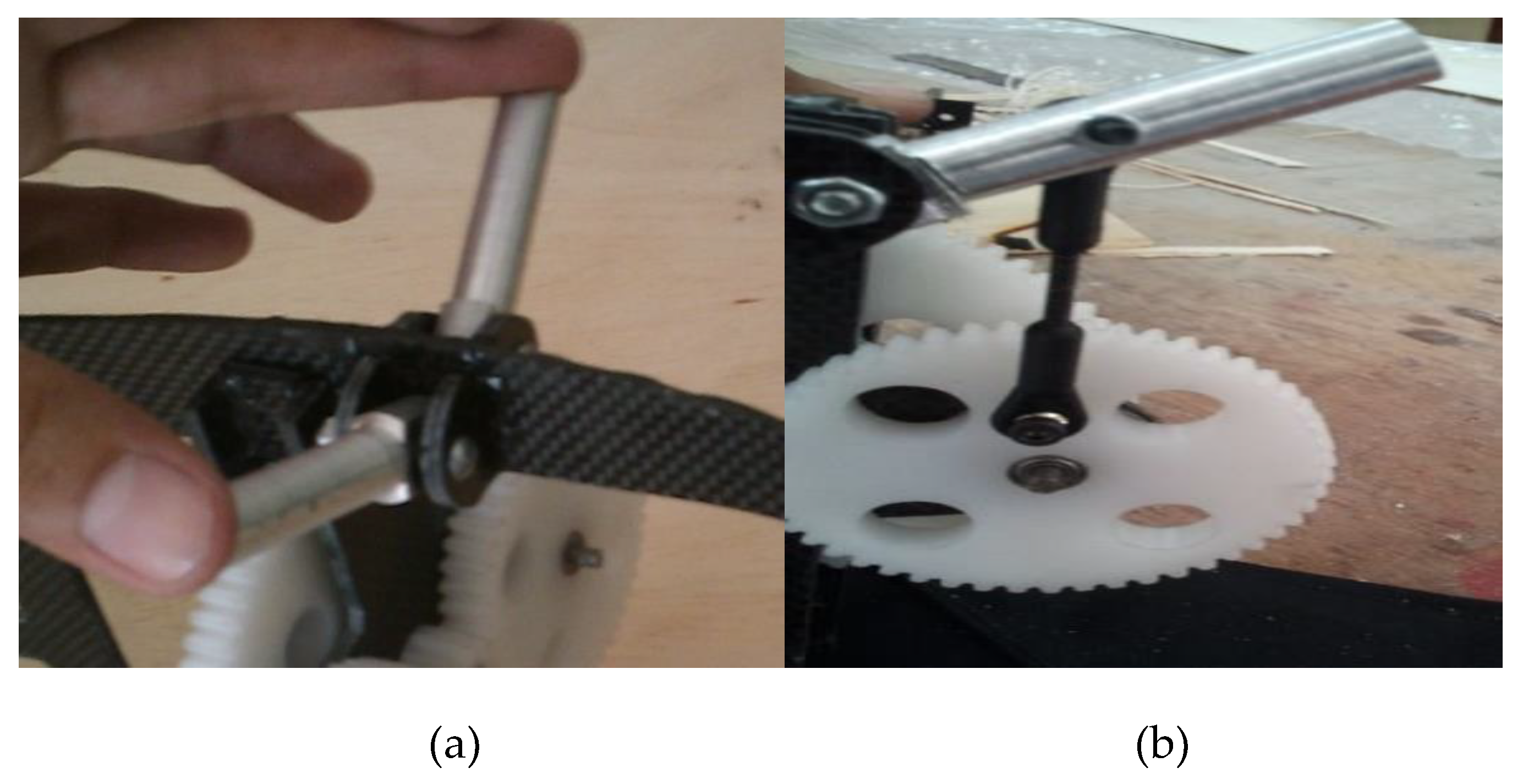

In order to obtain the required flapping frequency i.e., 4.43Hz the gear mechanism is designed with the gear reduction of 43:1. Design specifications of gears are mentioned in the

Table 5.

Tail is designed as the 30% surface area as that of wing. Tail would be able to perform two maneuvers i.e., pitch and yaw. CATIA design of tail is shown in

Table 6.

Figure 10.

(a) CAD Models of Gears; (b) CAD Model of Tail.

Figure 10.

(a) CAD Models of Gears; (b) CAD Model of Tail.

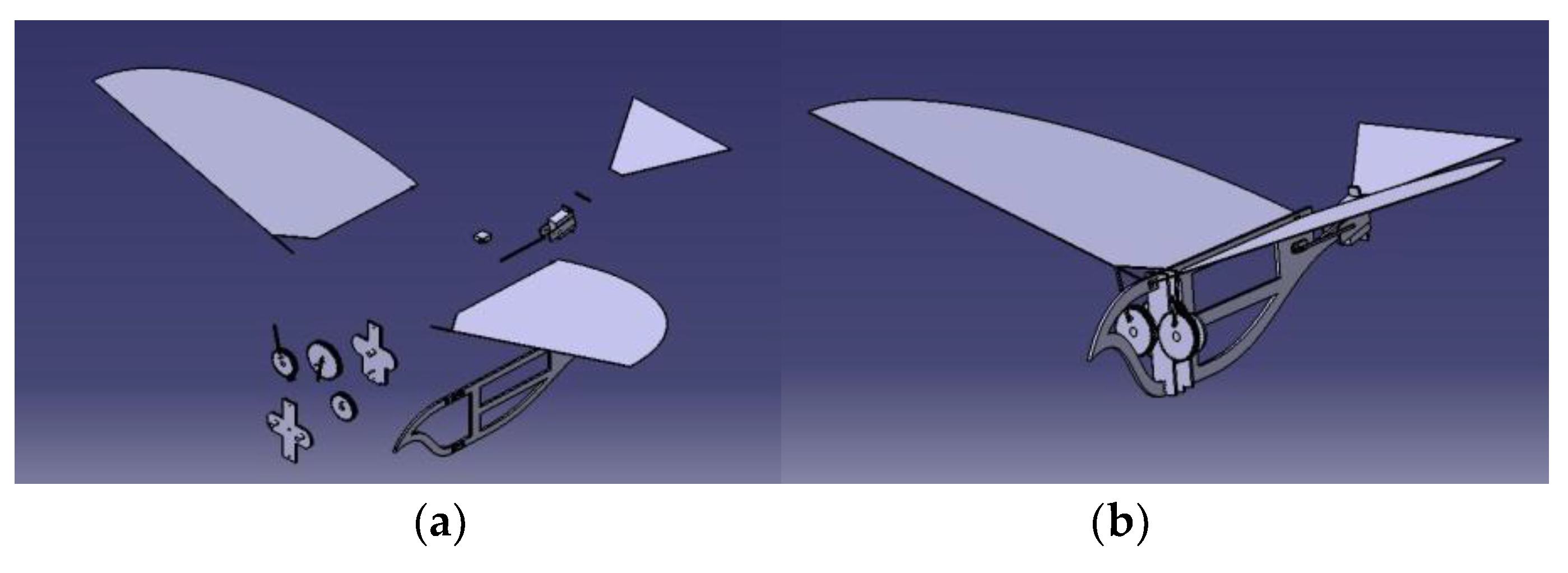

Assembly of bird sized aircraft is performed after designing of all individual parts in CATIA. This 3D model is then simulated to study its flapping mechanism.

Figure 11.

(a) Sub components of final assembly; (b) CAD Model of final assembly.

Figure 11.

(a) Sub components of final assembly; (b) CAD Model of final assembly.

3.1. Kinematics of Flapping Wing & Analytical Modelling of Aerodynamics

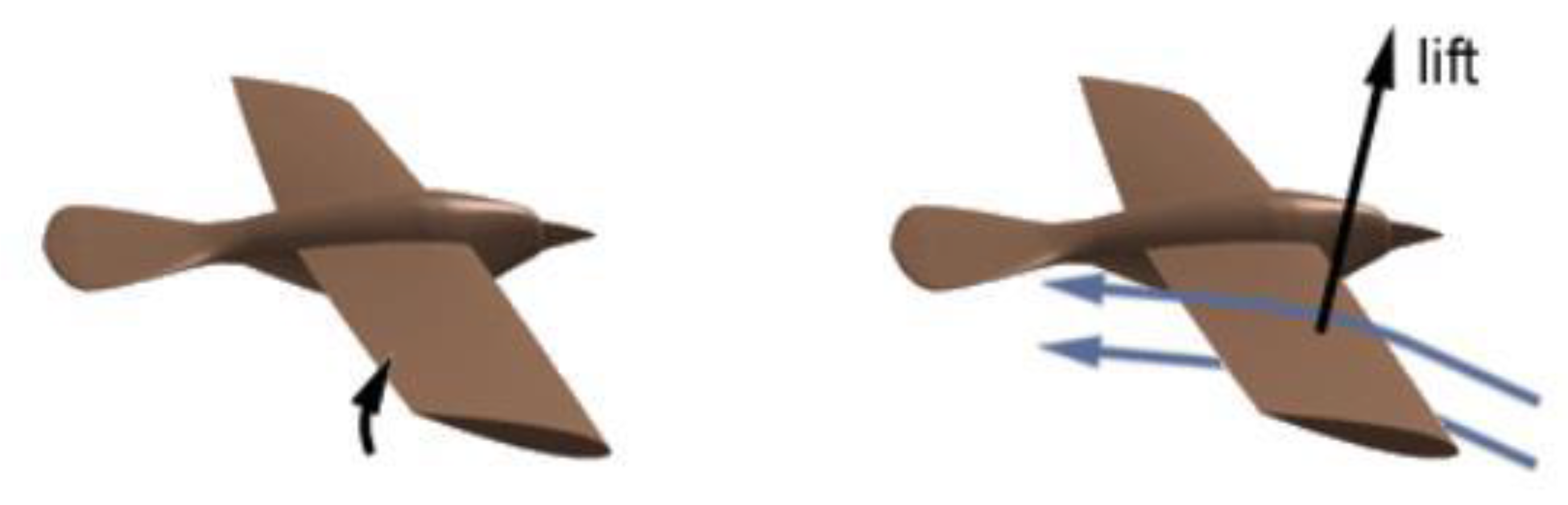

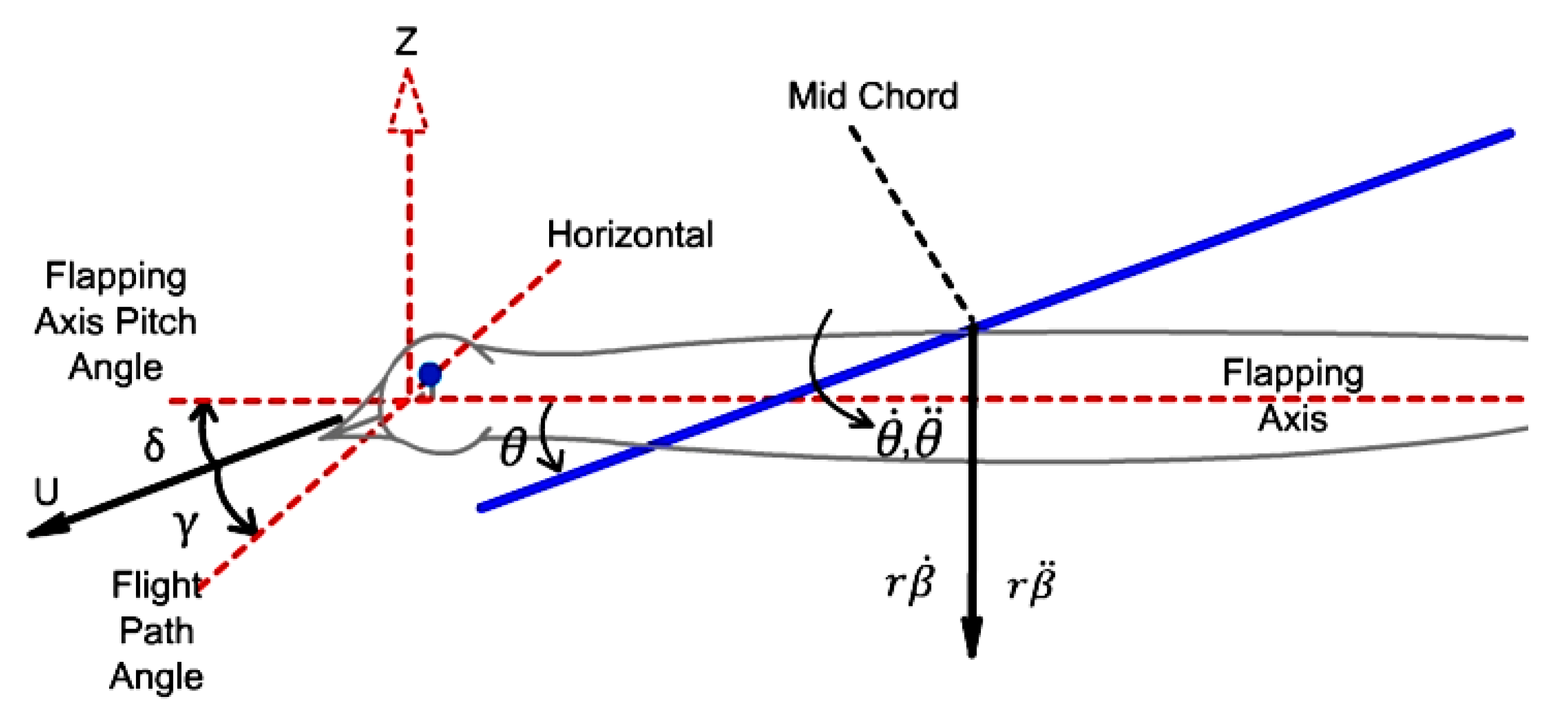

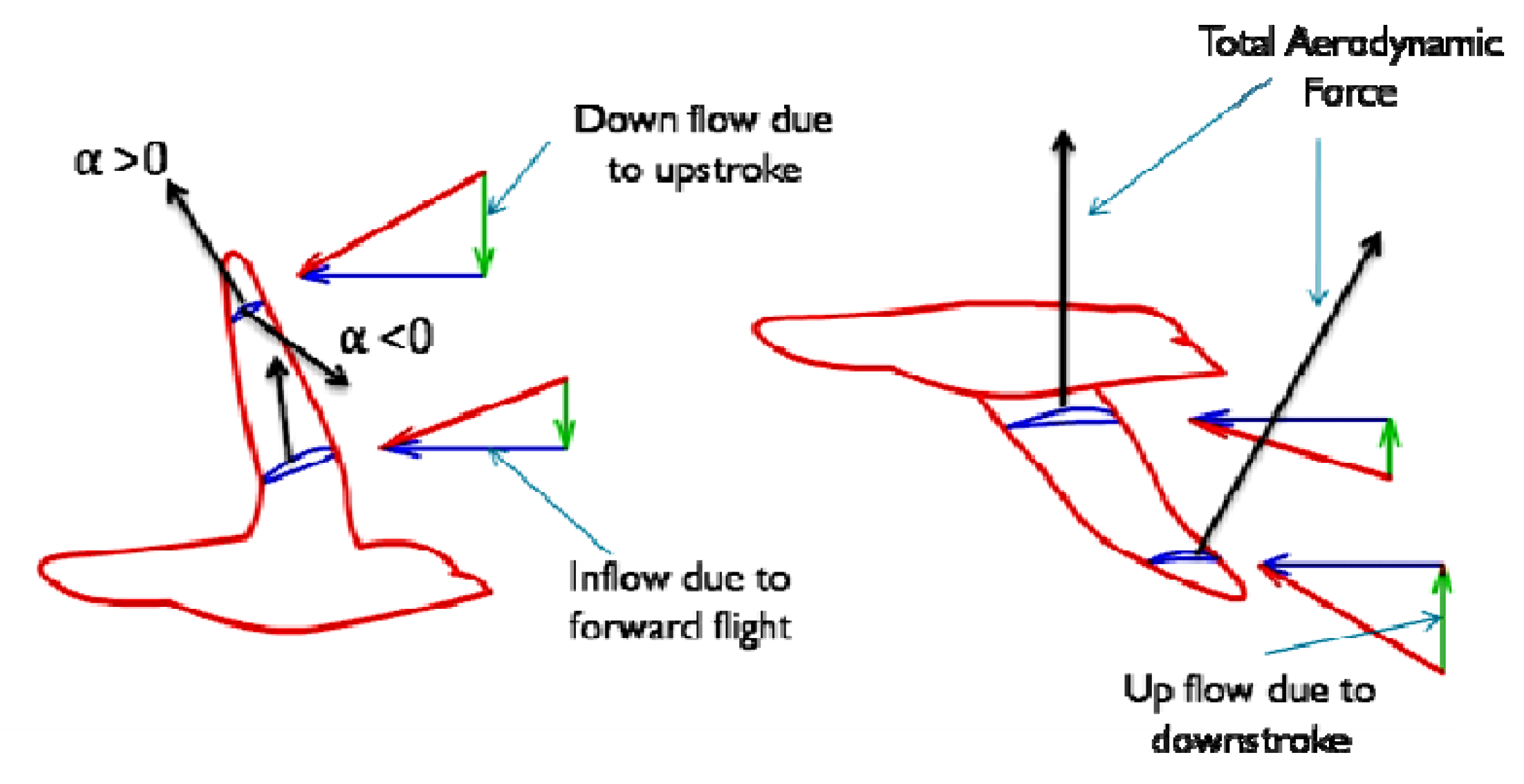

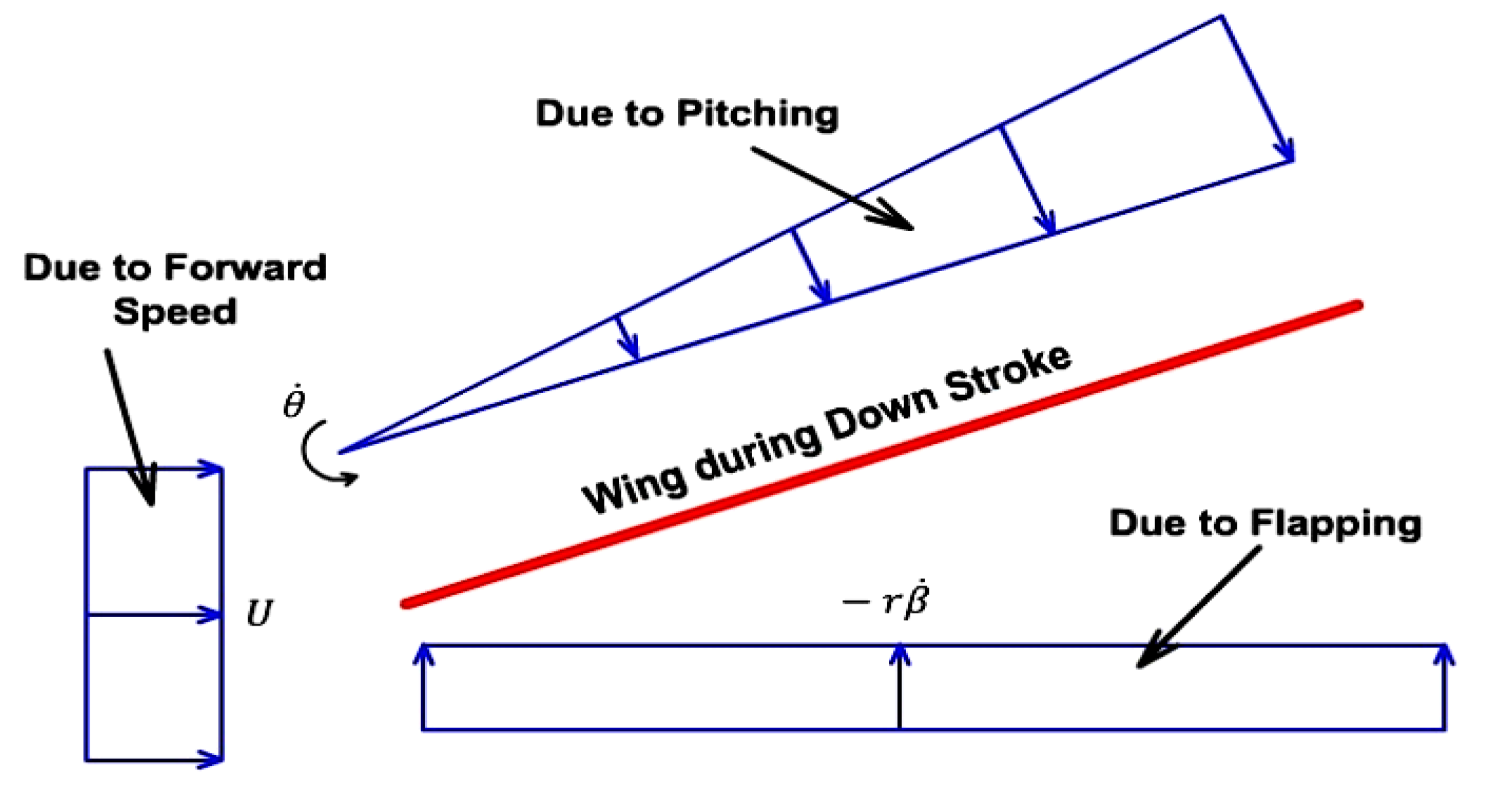

The flapping wing motion of ornithopters and entomopters can generally be categorized into three classes based on wing kinematics and the mechanism of force generation: horizontal stroke plane, inclined stroke plane, and vertical stroke plane. One of the most distinctive features of insect flight is their unique wing kinematics]. Due to their smaller scale and biological design, insects fundamentally differ from birds. In insects, all actuation is performed at the wing root, while birds possess internal skeletons with muscle attachments that enable localized actuation along the wing—such as wing warping—although wing deflection in birds may also occur passively. As a result of these differing kinematic mechanisms, the aerodynamic characteristics of insect flight diverge significantly from those observed in fixed-wing, rotary-wing, or even bird flight. Based on Ellington’s study, the generic wing motion (using a semi-elliptical wing model) can be classified under the inclined stroke plane regime. In this case, the aerodynamic force generated during flapping can be decomposed into vertical and horizontal components—lift, thrust, and drag—across both upstroke and downstroke cycles. In contrast, the horizontal stroke plane produces a greater horizontal thrust component, while the vertical stroke plane, often observed during takeoff or hovering (e.g., butterflies), involves wing motion that is nearly perpendicular to the chord.

During flapping, the vertical component of induced airflow is maximal near the wing tips and diminishes toward the root. Consequently, for a constant forward speed, the relative angle of attack (AOA) decreases from tip to root. To maintain an attached flow at the tip and avoid excessive AOA, the wing must pitch in the direction of flapping. During the downstroke, the total aerodynamic force tilts forward, comprising both lift and thrust components. In the upstroke, the AOA is consistently positive near the root but can vary near the tip depending on the degree of pitching. If the AOA at the tip remains positive, the outer wing regions contribute to positive lift and drag. However, if the AOA becomes negative, they produce negative lift but positive thrust. In the present study’s kinematic modeling of flapping-wing flight in pterosaurs, only periodic flapping and pitching motions are considered. For simplification without loss of generality, the flapping axis is assumed to lie close to the body’s longitudinal axis, while the pitching axis is placed at the leading edge of the wing. Both the upstroke and downstroke motions are illustrated in

Figure 12 which shows an inclined stroke plane characteristic of hovering flight in the long-eared bat (Plecotus auritus) [

48].

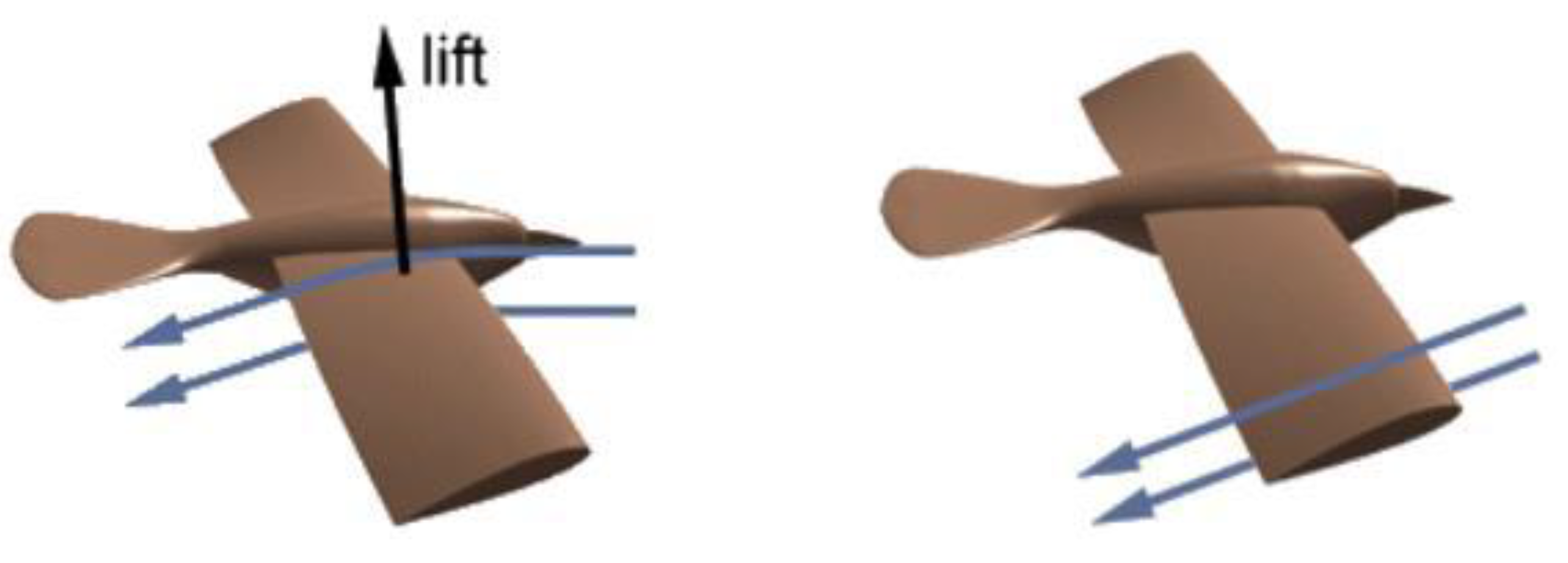

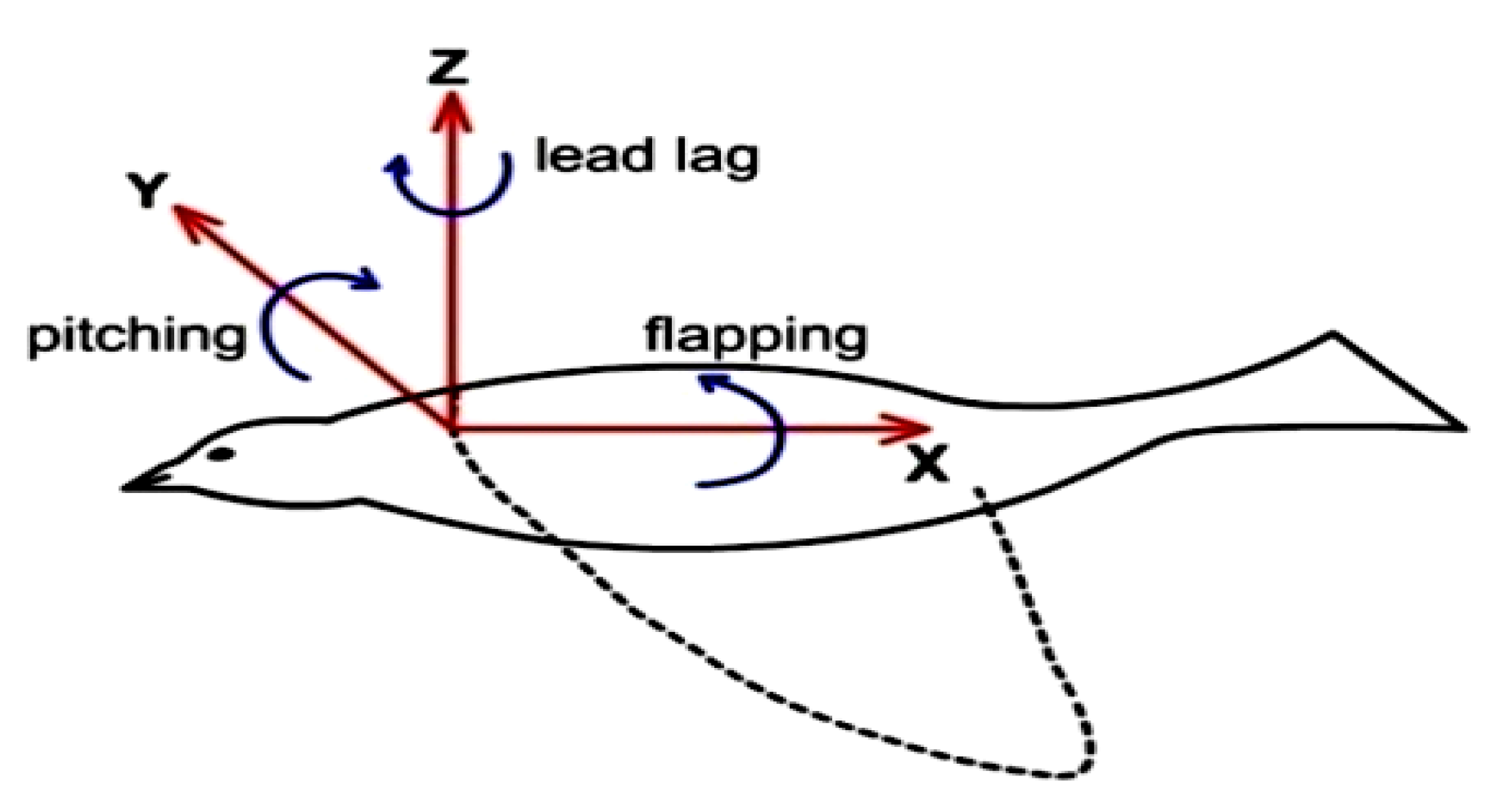

The flapping wing motion consists of three main types:

Flapping: The up-and-down motion generating the majority of the bird's power, with the largest degree of freedom.

Feathering: The pitching motion along the wing span, adjusting the angle of attack for efficient flight.

Lead-lag: The in-plane lateral movement of the wing, resulting from phase differences along the span, aiding in stability [

38].

Figure 13.

Angular Movements of Wing.

Figure 13.

Angular Movements of Wing.

Most of the practical ornithopters only employ flapping motion to generate lift and thrust with passive pitching caused by the aerodynamic and inertial loads because of flexible wings.

Analytical modelling for the aerodynamics of flapping wing is categorized into Quasi-steady and Unsteady aerodynamics [

30]. If the flapping frequency is low, quasi-steady approach can be applied as it ignores the wake effects and for high flapping frequency unsteady aerodynamics is used as it includes the wake effects. The focus of this study was to improve the analytical solution while giving special attention to inertial forces, which plays a vital role in the generation of lift and thrust. Elastic bending moment equation is being used to calculate the inertial forces instead of Newtonian mechanics. Former includes both the elastic effects and material properties whereas later only uses the effect of mass to calculate inertial force. Aerodynamic forces are modeled using Blade Element Analysis (a quasi-steady approach), where the time-dependent problem is converted into a series of steady-state problems. Steady-state aerodynamics are used to calculate the forces. Due to the finite wingspan, unsteady wake effects reduce the net aerodynamic forces, which are accounted for using Theodorsen’s function [

28]. The model simplifies by neglecting leading edge suction effects and other unsteady lift enhancement mechanisms, as they are minimal in ornithopters. This approach, however, is inadequate for simulating the highly unsteady flight of insects. In addition to aerodynamic forces, the inertial effects of airflow also contribute to the lift and thrust of FMAVs.

3.1.1. Assumptions

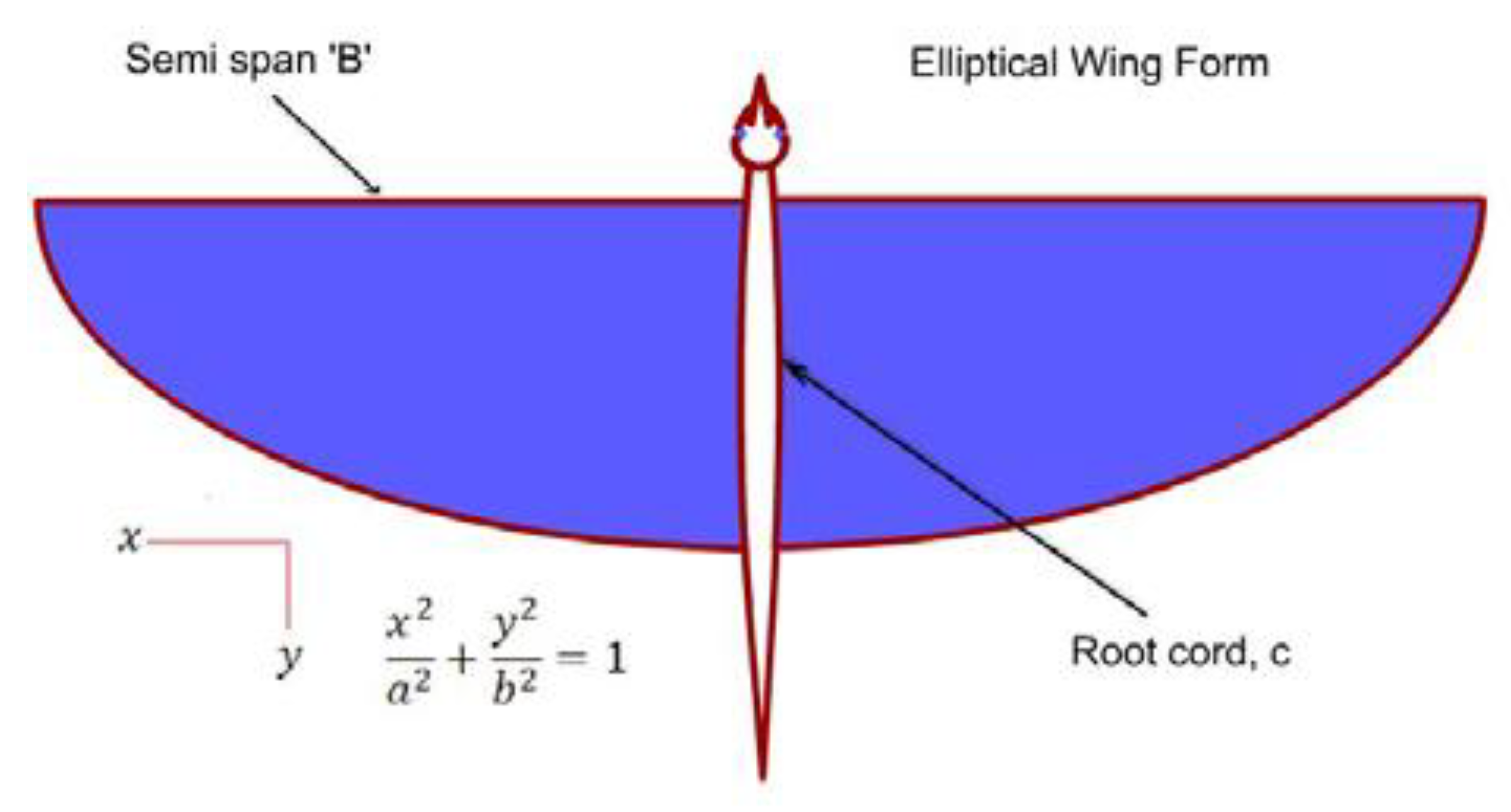

The wings are made of a flexible membrane attached to a spar at the leading edge, with a half-elliptical wing shape.

Only flapping is induced by the powertrain system, with equal up/down flapping angles.

The front spar serves as a pivot for passive pitching movement, driven by aerodynamic and inertial loads.

The flow is assumed to remain attached to the wing.

Both flapping and pitching movements are modeled as sinusoidal functions, with a specified amount of lag.

The upstroke and downstroke have equal durations.

Figure 14 illustrates the analytical model of the wing.

3.1.2. Kinematics

The wing flaps from top to bottom with total flapping angle of 2βmax as shown.

Figure 15.

Front view of Flapping Wings.

Figure 15.

Front view of Flapping Wings.

The flapping angle β varies as sinusoidal function. β and its rate are given by following equations

Here 0 is the maximum pitch angle, is the lag between pitching and flapping angle r is the distance along the span of the wing under consideration

The lag between pitching and flapping angle should be such that when the relative air velocity is maximum, the pitch angle should be maximum (fig. 5.3). It is possible only if the lag is 90o.

Figure 16.

Motion of flapping Wing in Side View.

Figure 16.

Motion of flapping Wing in Side View.

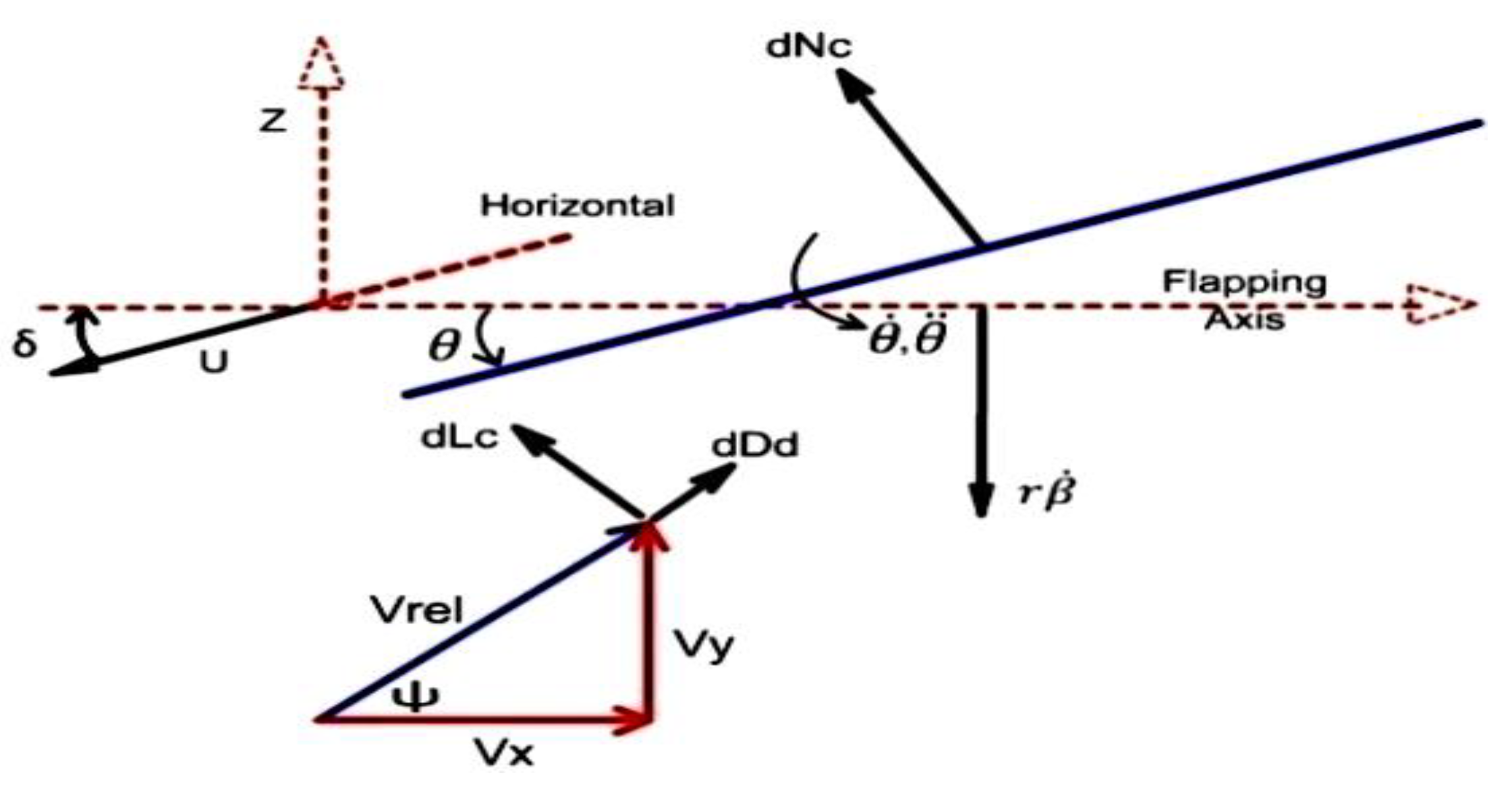

3.1.3. Modelling of Aerodynamic Forces

From

Figure 17 we can find the vertical and horizontal components of relative wind velocity as under: -

For horizontal flight, the flight path angle γ is zero. Also 0.75c

is the relative air effect of the pitching rate

, which is manifested at 75% of the chord length [

28].

Now we can find out the relative velocity, relative angle between the two velocity components ψ and the effective AOA as under:-

The section lift coefficient due to circulation (Kutta-Joukowski condition) for flat plate [

28] is given by

where C(k) is the Theodorsen Lift Deficiency [

17] factor which is a function of reduced frequency k and can be calculated as under

and

are given by: -

The sectional lift dLc can be calculated as

Here c is the chord length and dr is width of the element of wing under consideration.

The apparent mass effect (momentum transferred by accelerating air to the wing) for the section, is perpendicular to the wing, and acts at mid chord [

17], calculated by

The drag force has two components. These are calculated as:-

The total section drag is then given as

Figure 18.

Forces on Each Section of Wing.

Figure 18.

Forces on Each Section of Wing.

The circulatory lift dL

c non-circulatory force dN

nc and drag dD

d for each wing section change direction at each instant during flapping. These forces are resolved into components perpendicular and parallel to the forward velocity in the vertical and horizontal directions, respectively. The vertical and horizontal components of the forces are given as:-

We can determine the lift and thrust of the ornithopter for each time instance. These forces are calculated for all time steps in one flap cycle, and the average values are taken to find the total average lift and thrust. If the wing is divided into ‘n’ strips of equal width and one flap cycle into ‘m’ equal time steps, then

Figure 3.

Schmidt’s Human-Powered Ornithopter.

Figure 3.

Schmidt’s Human-Powered Ornithopter.

Figure 4.

James DeLaurier’s Ornithopter.

Figure 4.

James DeLaurier’s Ornithopter.

Figure 6.

Micro Air Vehicles Ornithopters developed recently.

Figure 6.

Micro Air Vehicles Ornithopters developed recently.

Figure 8.

CAD of fuselage.

Figure 8.

CAD of fuselage.

Figure 12.

Forces Generated During Upstroke and Down stroke.

Figure 12.

Forces Generated During Upstroke and Down stroke.

Figure 14.

Wing Form for the Analytical Study.

Figure 14.

Wing Form for the Analytical Study.

Figure 17.

Relative Air Flow.

Figure 17.

Relative Air Flow.

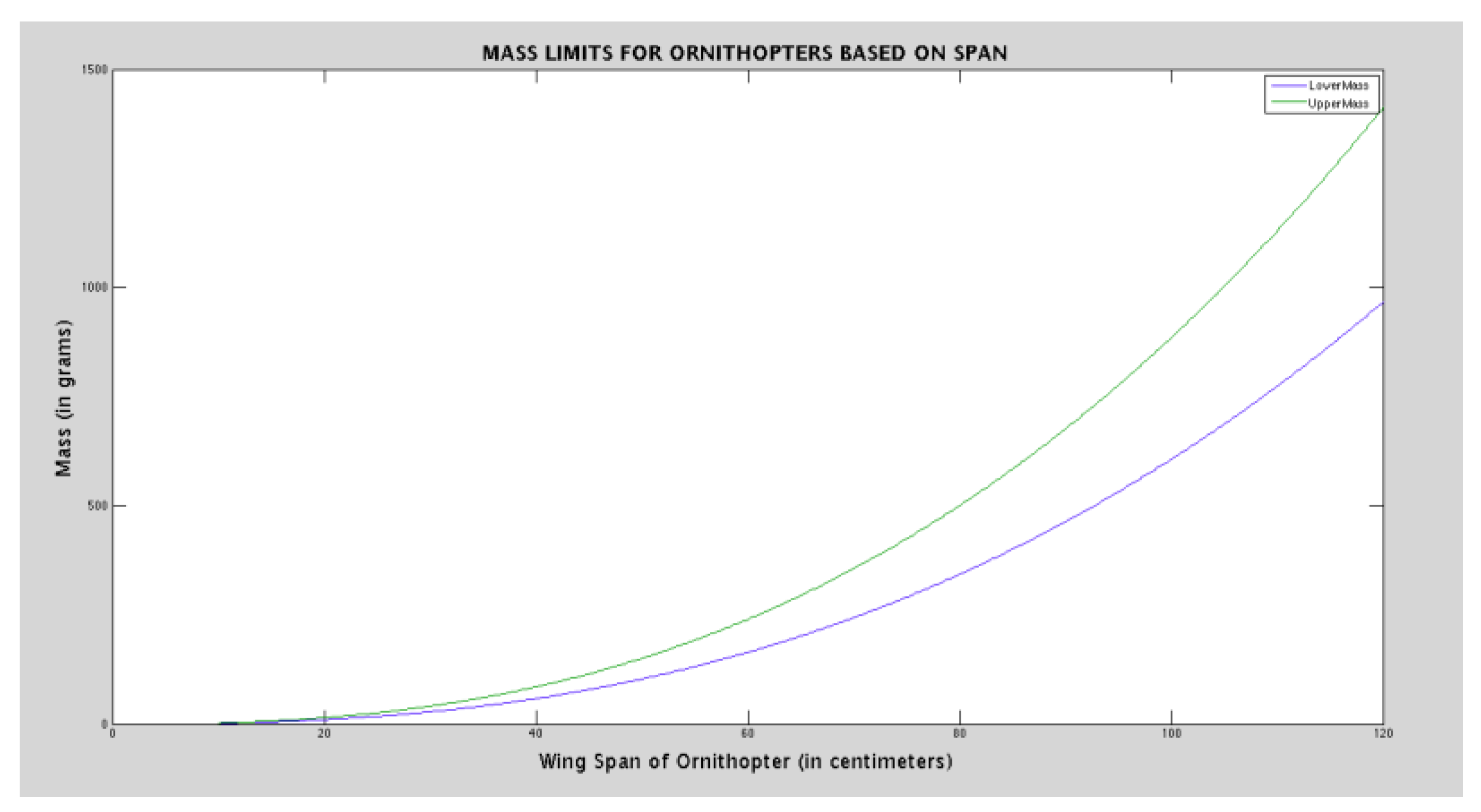

Figure 19.

Mass Limits for Ornithopter.

Figure 19.

Mass Limits for Ornithopter.

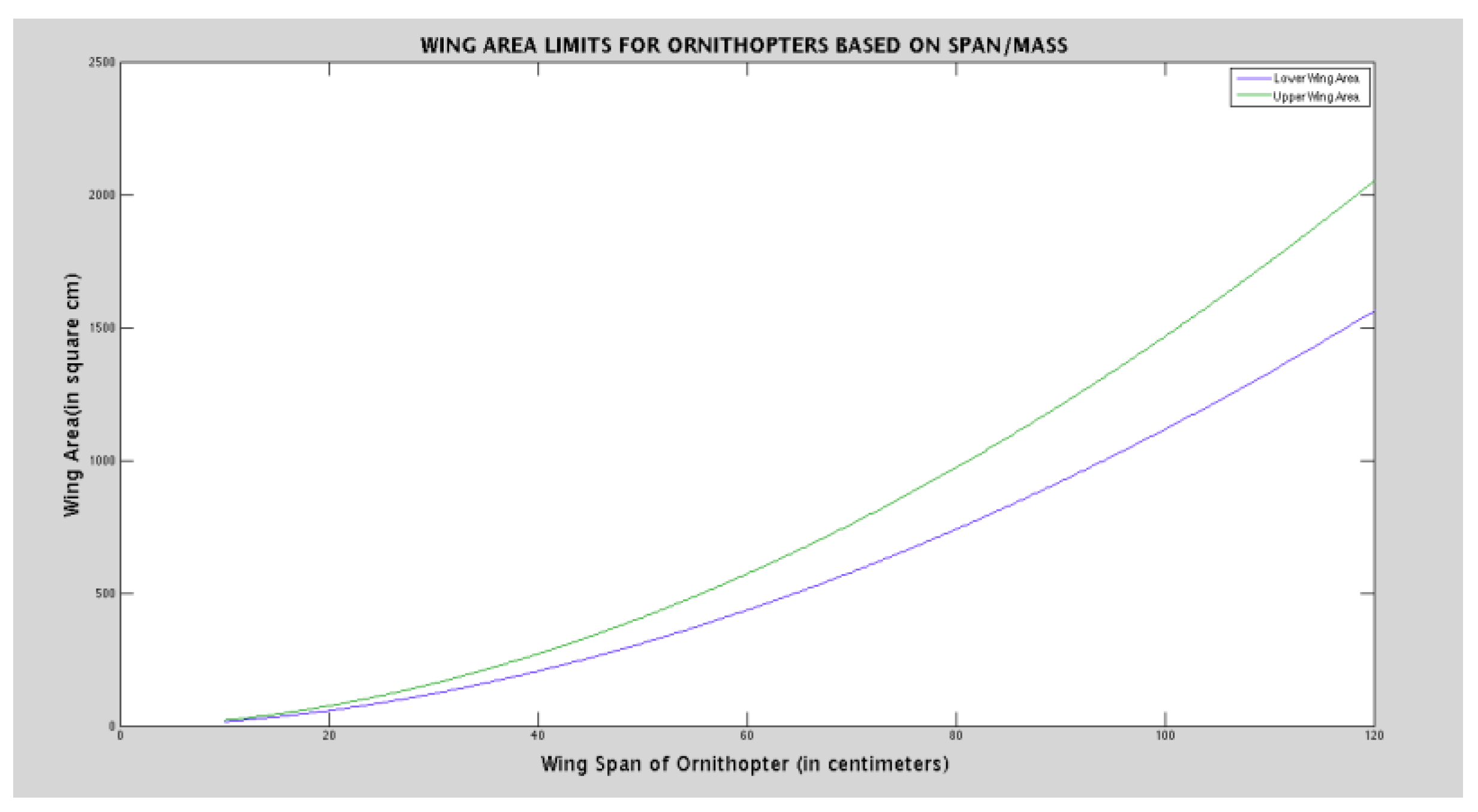

Figure 20.

Wing Area Limits for Ornithopter.

Figure 20.

Wing Area Limits for Ornithopter.

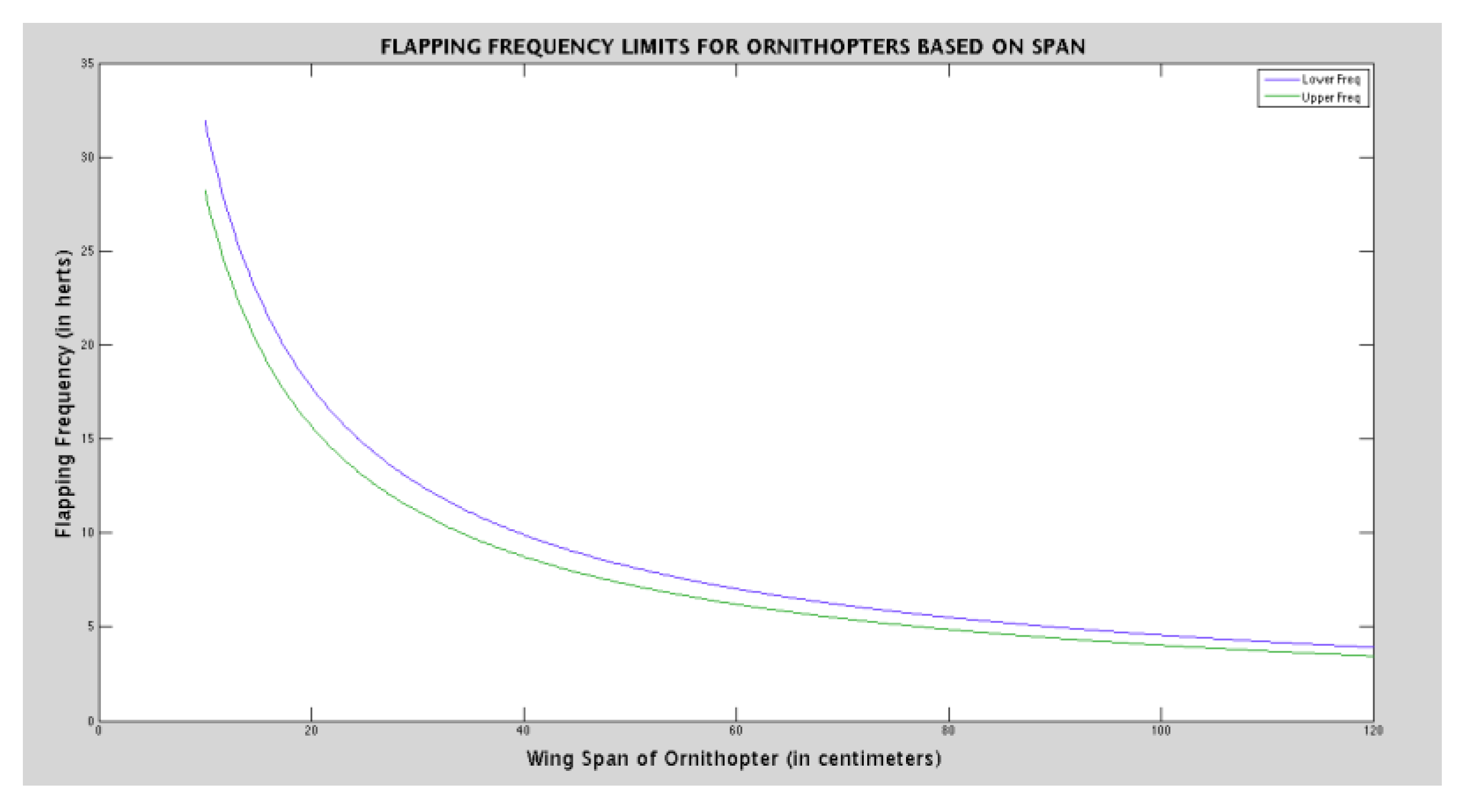

Figure 21.

Flapping Frequency Limit for Ornithopter.

Figure 21.

Flapping Frequency Limit for Ornithopter.

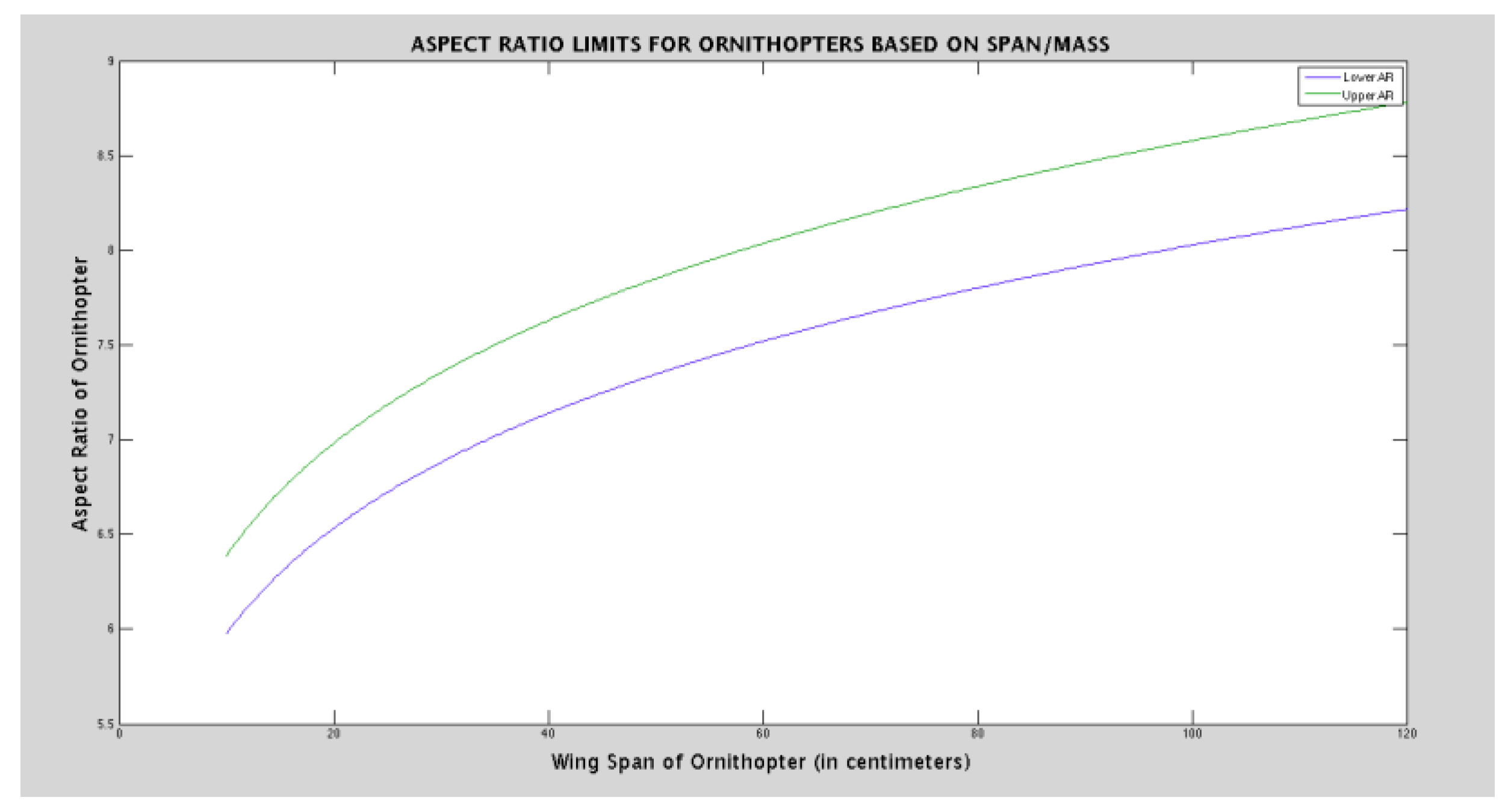

Figure 22.

Aspect Ratio Limits for Ornithopter.

Figure 22.

Aspect Ratio Limits for Ornithopter.

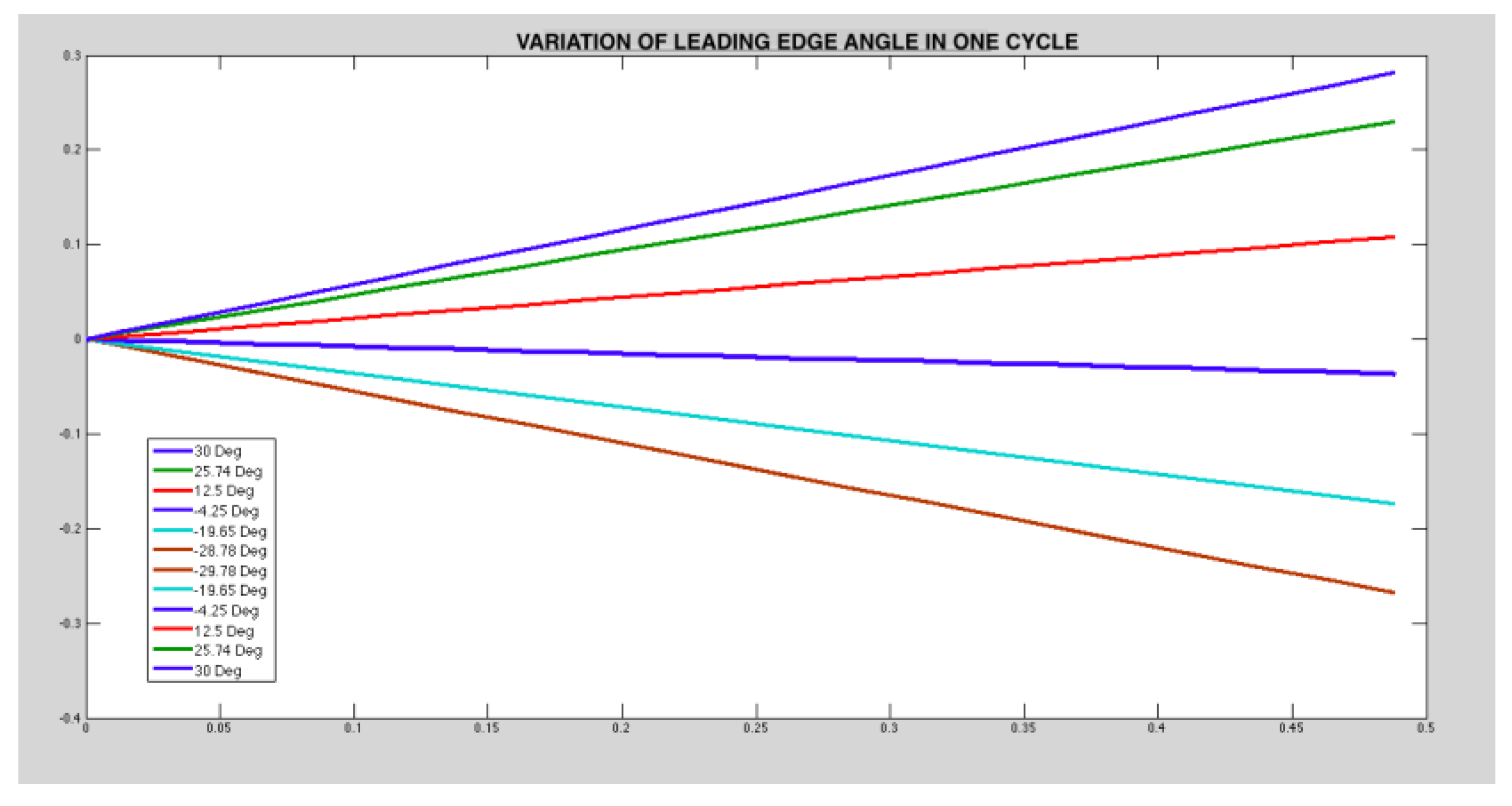

Figure 24.

Variation of leading edge in one complete cycle.

Figure 24.

Variation of leading edge in one complete cycle.

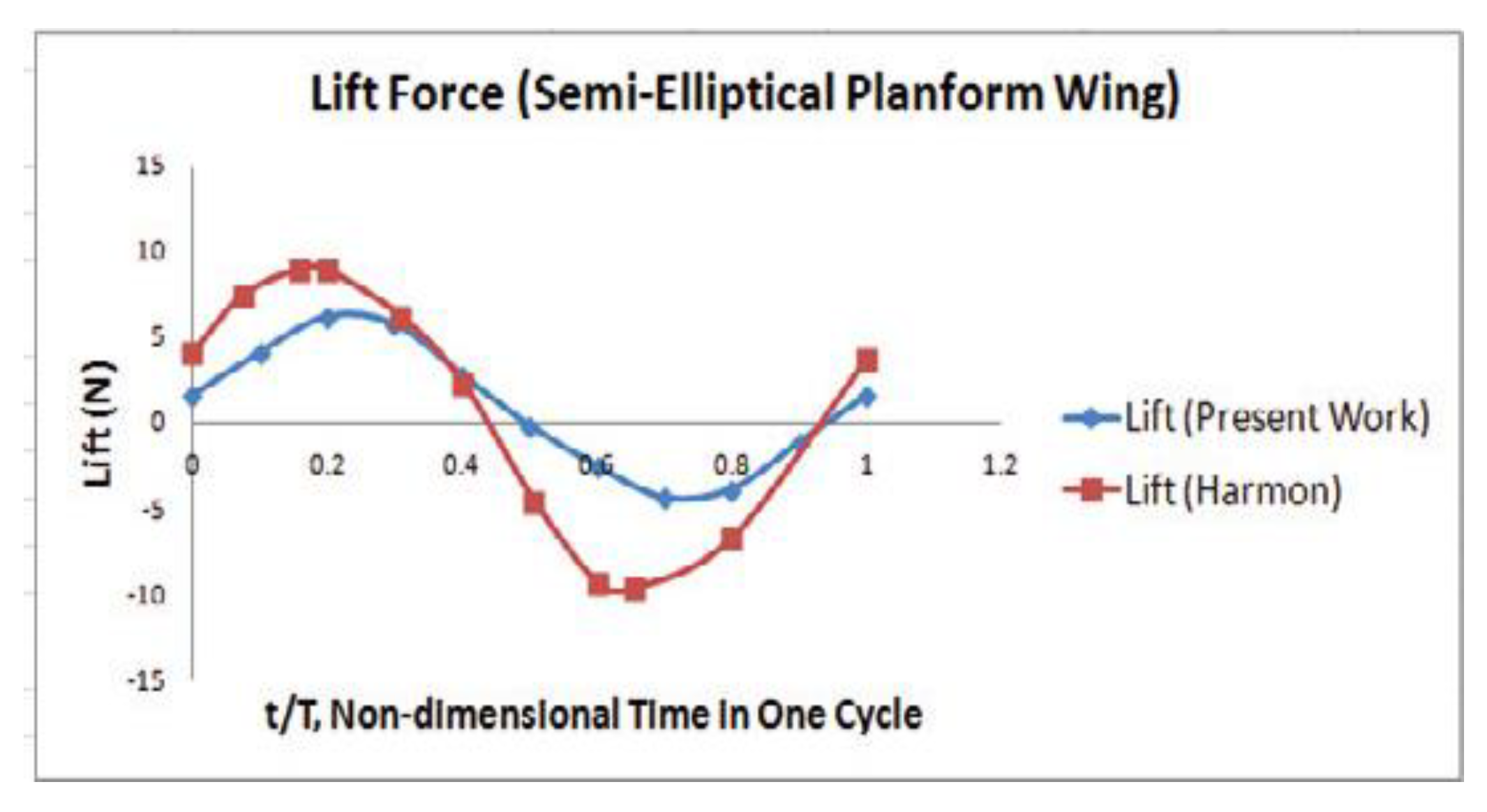

Figure 25.

Lift Force (Present Work vs Harijono [

35]).

Figure 25.

Lift Force (Present Work vs Harijono [

35]).

Figure 26.

Thrust Force (Present Work Vs Harjino [

35]).

Figure 26.

Thrust Force (Present Work Vs Harjino [

35]).

Figure 27.

Brushless Motor.

Figure 27.

Brushless Motor.

Figure 29.

Electronic Speed Controller.

Figure 29.

Electronic Speed Controller.

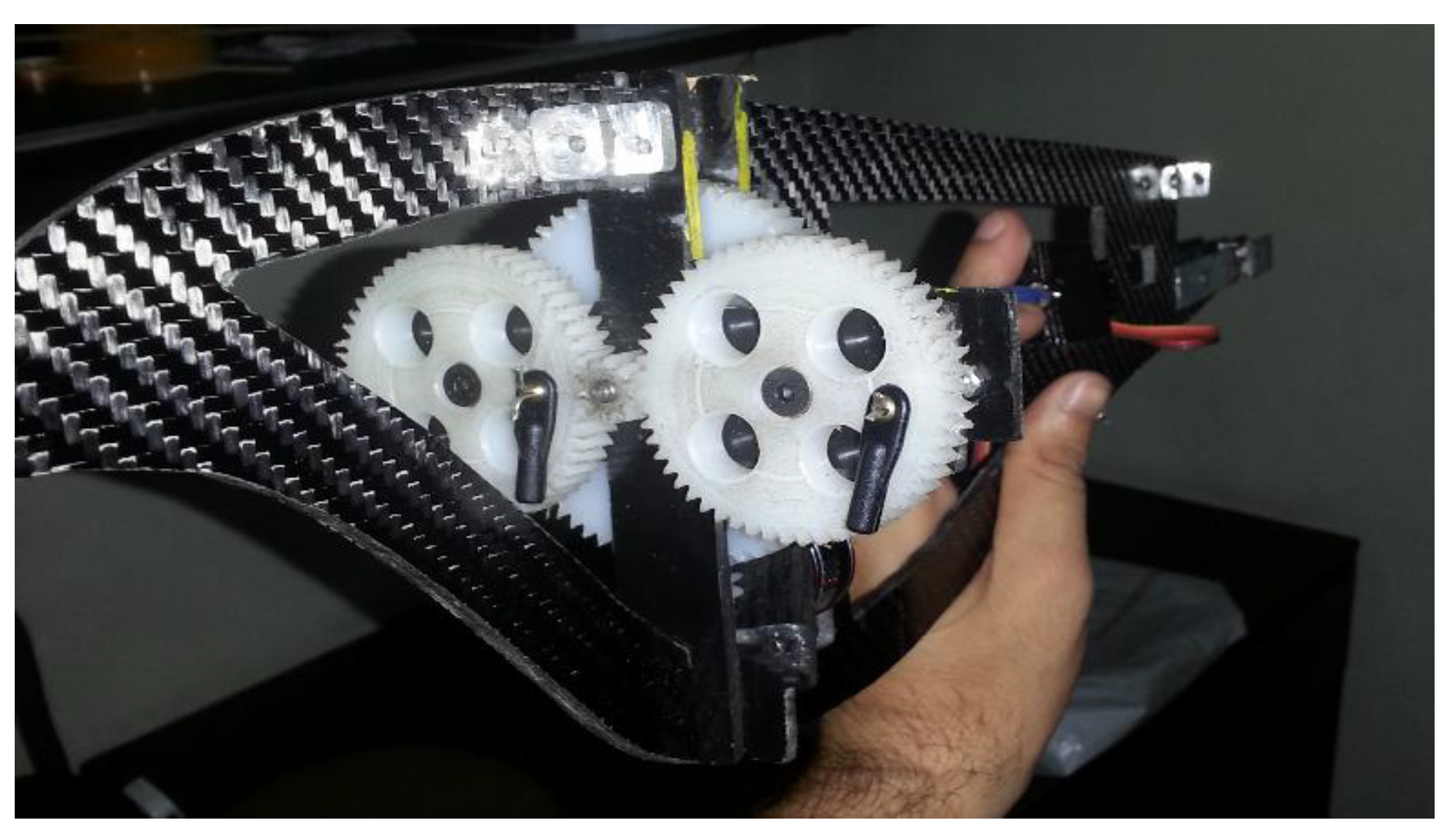

Figure 32.

Gears assembly mounted on fuselage.

Figure 32.

Gears assembly mounted on fuselage.

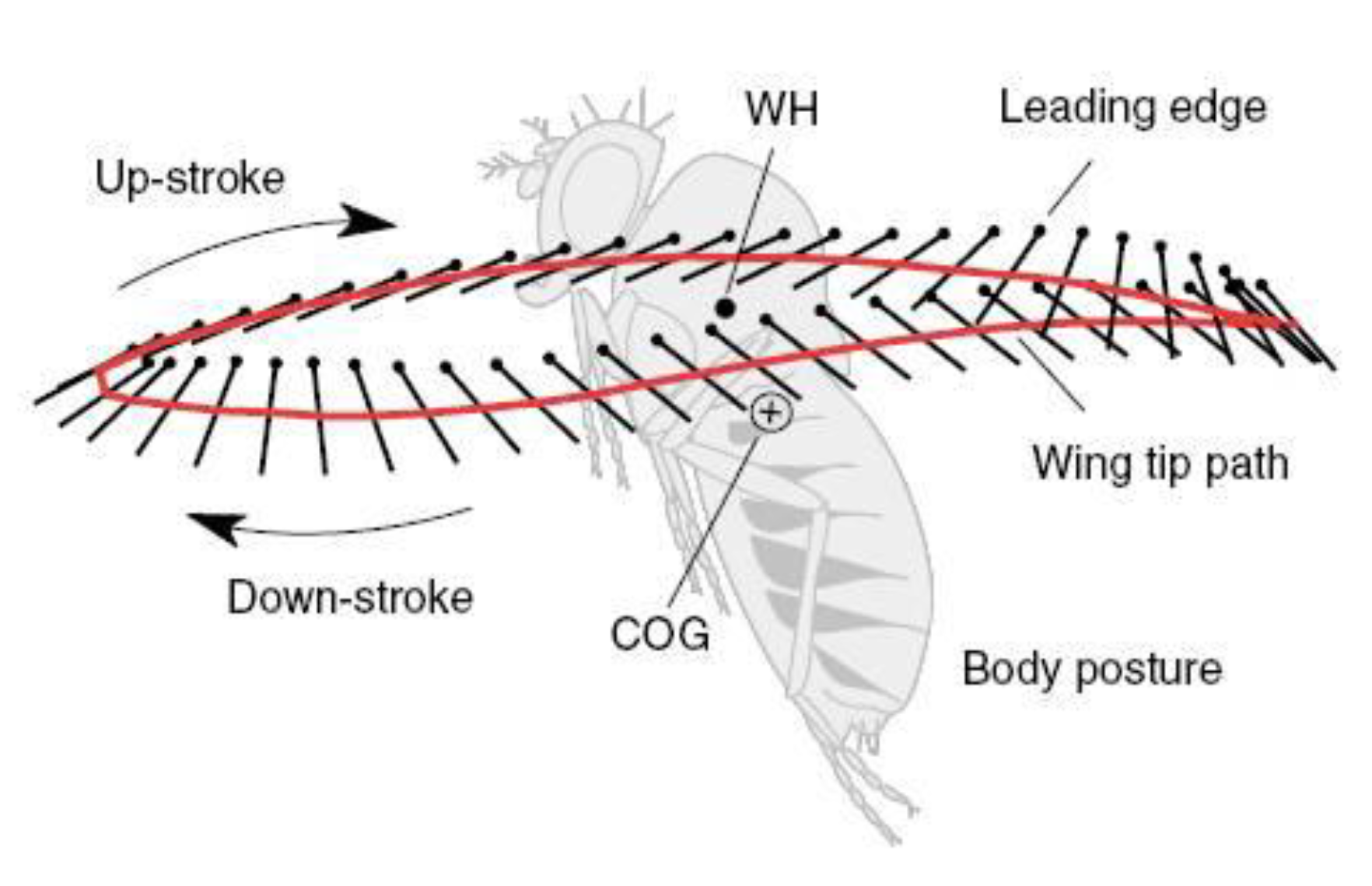

Figure 35.

Wing motion of a fly in hovering flight.

Figure 35.

Wing motion of a fly in hovering flight.

Figure 37.

Wings after complete fabrication process.

Figure 37.

Wings after complete fabrication process.

Figure 39.

Front view of assembled flapping wing micro aerial vehicle.

Figure 39.

Front view of assembled flapping wing micro aerial vehicle.

Figure 40.

Side view of assembled flapping wing micro aerial vehicle.

Figure 40.

Side view of assembled flapping wing micro aerial vehicle.

Table 1.

Important Parameters.

Table 1.

Important Parameters.

| Parameters |

Formulas |

Value |

| Span |

Approx. |

1 m |

| Mass |

(0.85×b)2.56

|

.66 kg |

| Length |

|

.70 m |

| Wing Area |

0.16×m0.72

|

.1186 m2

|

| Root Chord |

(8×S)/(b×π) |

.305 m |

| Flapping Frequency |

3.87×m−0.33

|

4.42 Hz |

| Upstroke angle |

Approx. |

250

|

| Down stroke angle |

Approx. |

300

|

Table 2.

Ornithopter Model Specification.

Table 2.

Ornithopter Model Specification.

| Areas |

Parameters |

Values in cm |

| Fuselage |

Length |

70 |

| Wing |

Span |

100 |

| Chord |

30.5 |

| Primary Spar |

50 |

| Secondary Spar |

46.14 |

| Area |

1198 |

| Aspect Ratio |

8.348 |

| Tail |

Span |

23.59 |

| Chord |

15.25 |

| Area |

359.8 |

Table 3.

Fuselage Specifications.

Table 3.

Fuselage Specifications.

| Parameters |

Values |

| Length |

50 cm |

| Height |

13 cm |

Table 5.

Gears Specifications.

Table 5.

Gears Specifications.

| Gears |

No. of Teeth |

Pitch Diameter |

| GEAR 1 & 3 |

10 |

1.25 cm |

| GEAR 2 |

71 |

8.87 cm |

| GEAR 4 & 5 |

50 |

6.24 cm2

|

Table 6.

Tail Specifications.

Table 6.

Tail Specifications.

| Parameters |

Values |

| Span |

23.60 cm |

| Chord |

15.25 cm |

| Area |

360 cm2

|

Table 7.

Motor Specifications.

Table 7.

Motor Specifications.

| Motor Specifications |

|---|

| RPM/V |

1100RMP/V |

| Weight |

82 gm. |

| Dimension |

28.5mm (Dia.) x 36.5mm (Length) |

| Shaft diameter |

4mm |

| Max thrust |

1200g |

Table 8.

Battery Specifications.

Table 8.

Battery Specifications.

| Battery Specifications |

|---|

| RPM/V |

1100RMP/V |

| Weight |

82 gm. |

| Dimension |

28.5mm (Dia.) x 36.5mm (Length) |

| Shaft diameter |

4mm |

| Max thrust |

1200g |

Table 9.

Specifications of Electronic Speed Controller.

Table 9.

Specifications of Electronic Speed Controller.

| Electronic Speed Controller Specifications |

|---|

| RPM/V |

1100RMP/V |

| Weight |

82 gm. |

| Dimension |

28.5mm (Dia.) x 36.5mm (Length) |

| Shaft diameter |

4mm |

| Max thrust |

1200g |