Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Wood Microparticles

2.3. Characterization of Wood Particles

2.4. Fabrication of Composite Films

2.5. Characterization of Composite Film

2.5.1. Tensile Testing

2.5.2. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

2.5.3. Measurement of Natural Frequency

2.5.4. Digital Image Correlation (DIC)

2.5.5. Contact Angle Measurement

2.5.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.5.7. Microscopic Analysis of Composite Film

2.6. Development of Film Membrane by Biomimetic

2.7. Computational Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Wood Particles

3.2. Characterization of Developed Film

3.2.1. Tensile Behaviour

3.2.2. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

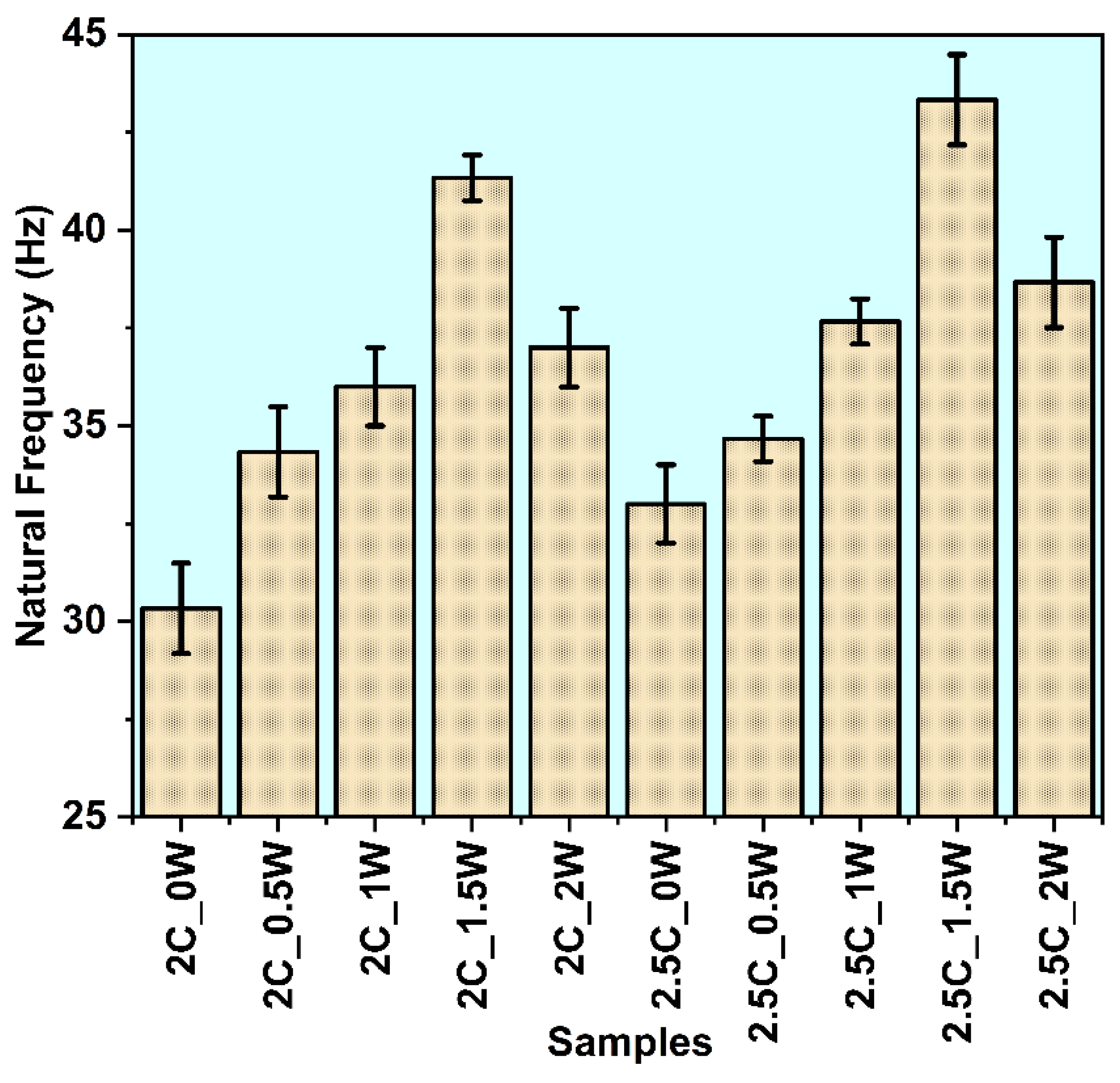

3.2.3. Natural Frequency

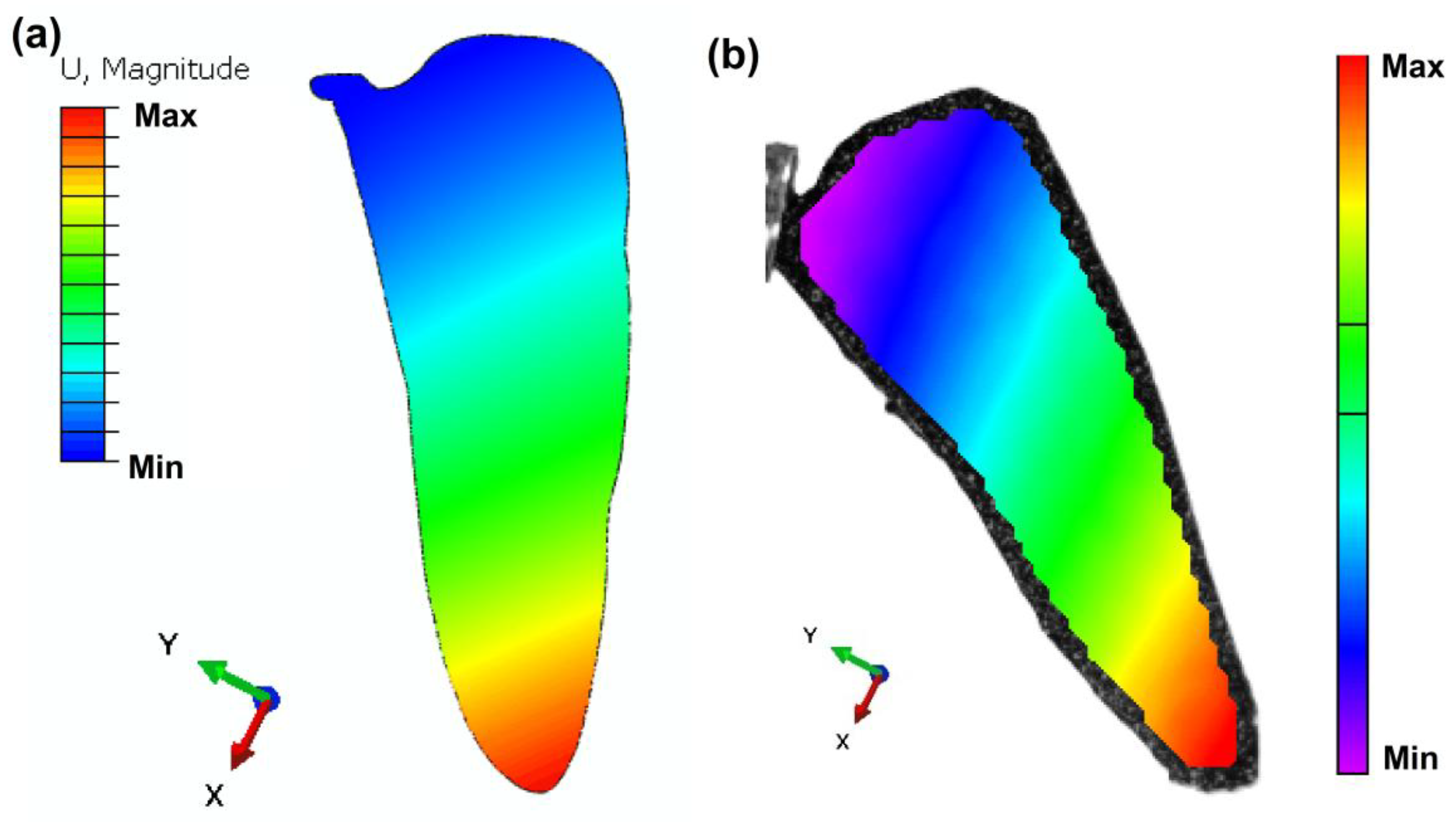

3.2.4. DIC and Computational Analysis of Wing

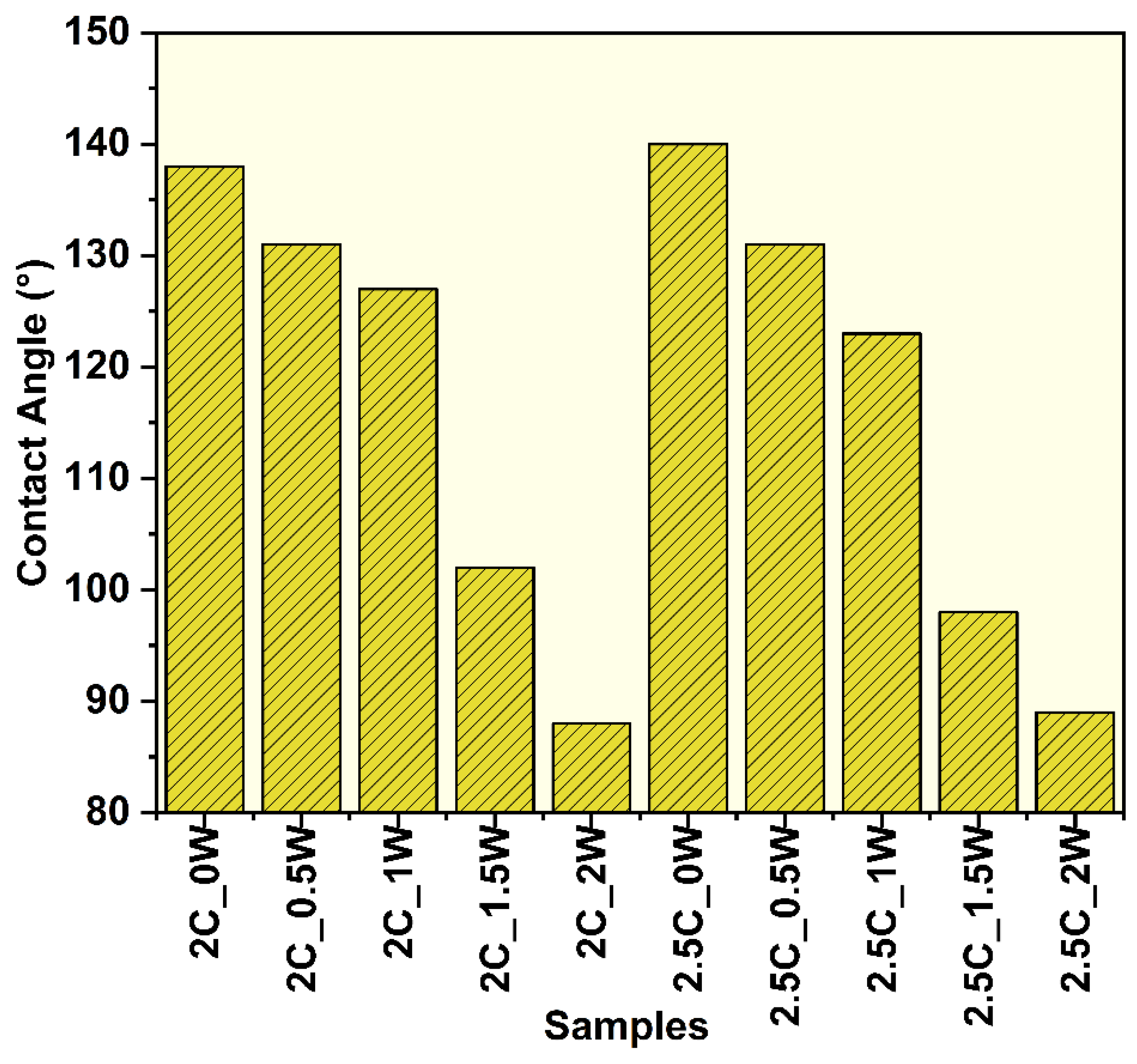

3.2.5. Water Contact Angle Measurements

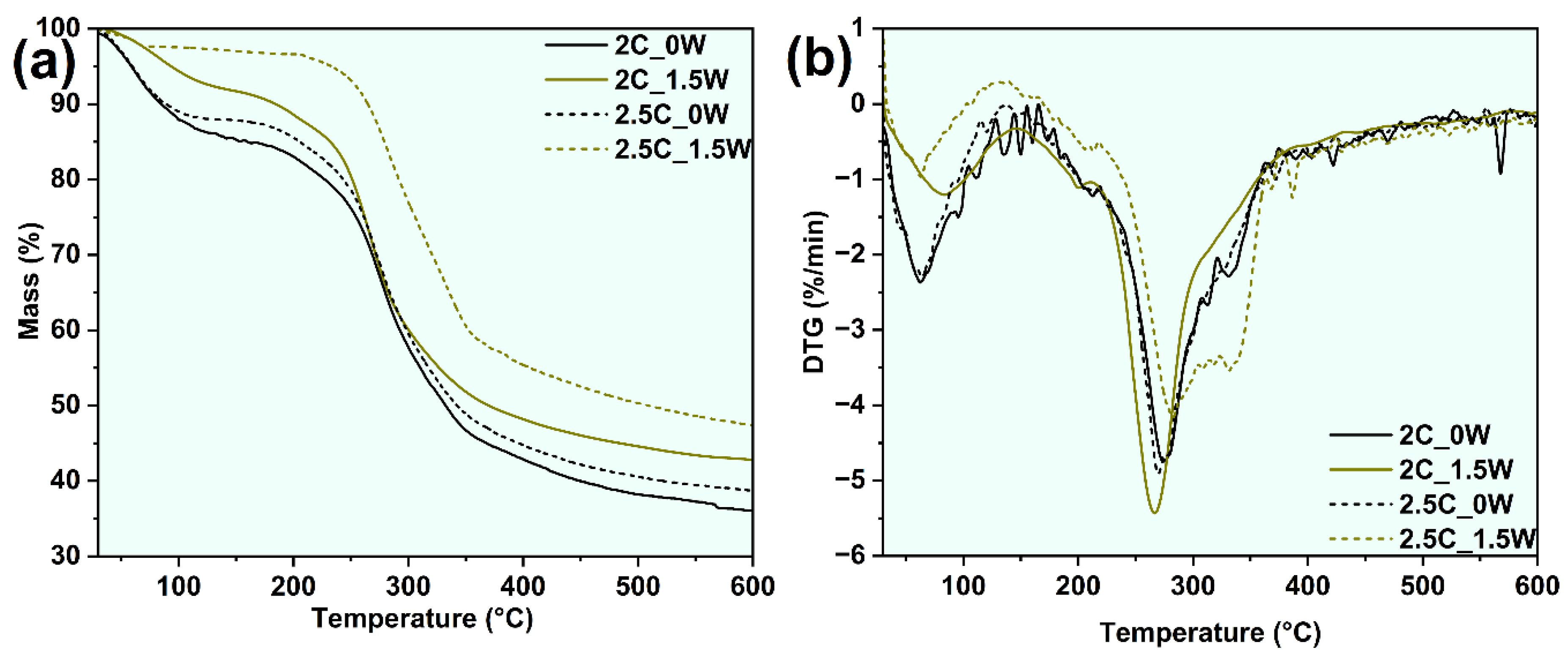

3.2.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis

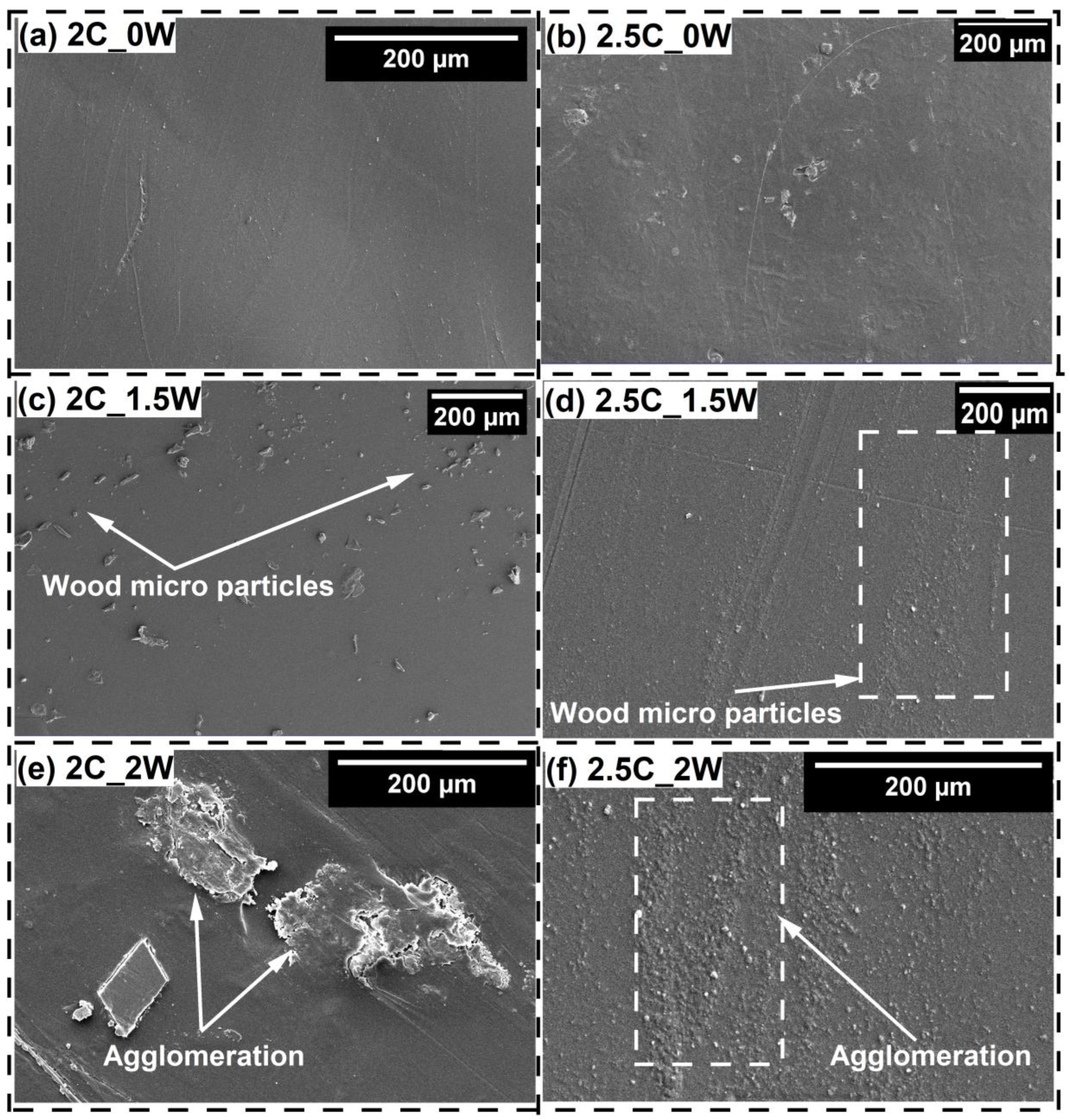

3.2.7. Microscopic Analysis

4. Conclusions

- Treatment of the wood particles with 5% NaOH solution enhanced their crystallinity, and increased their surface roughness, resulted in better mechanical properties of the film.

- Developed composite films showed significant enhancement in elastic modulus and tensile strength as compared to chitosan films. The sample (2.5C_1.5W) exhibited the highest Young’s modulus, and the highest tensile strength.

- The 2.5C_1.5W sample showed the highest storage modulus and lowest damping factor.

- 2.5C_1.5W sample also showed higher natural frequency(40Hz), than the average flapping frequency of a dragonfly wing (20 to 30 Hz).

- First mode shape of the developed bio-mimetic wings was determined using, DIC method, and it was also numerically validated using Abacus software.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

References

- Fan T X, Chow S K and Zhang D. Biomorphic mineralization: From biology to materials. Prog Mater Sci 2009, 54, 542–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes M, Lutz C P, Hirjibehedin C F, Giessibl F J and Heinrich A J. The force needed to move an atom on a surface. Science (1979) 2008, 319, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Marquez J L, Di Marzo Serugendo G, Montagna S, Viroli M and Arcos J L. Description and composition of bio-inspired design patterns: A complete overview. Nat Comput 2013, 12, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren L and Li, X. Functional characteristics of dragonfly wings and its bionic investigation progress. Sci China Technol Sci 2013, 56, 884–897. [Google Scholar]

- Ren L and Liang, Y. Biological couplings: Function, characteristics and implementation mode. Sci China Technol Sci 2010, 53, 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, B. Biomimetics: Lessons from Nature - an overview. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2009, 367, 1445–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput V, Mulay P and Mahajan C M. Bio-inspired algorithms for feature engineering: analysis, applications and future research directions. Inf Discov Deliv 2024.

- Niewiarowski P H, Stark A Y and Dhinojwala A. Sticking to the story: Outstanding challenges in gecko-inspired adhesives. Journal of Experimental Biology 2016, 219, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundanati L, Guarino R and Pugno N M. Stag beetle elytra: Localized shape retention and puncture/wear resistance. Insects 2019, 10.

- Dura H B, Hazell P J, Wang H, Escobedo-Diaz J P and Wang J. Energy absorption of composite 3D-printed fish scale inspired protective structures subjected to low-velocity impact. Compos Sci Technol 2024, 255.

- Wilkins, R.; Bouferrouk, A. Numerical framework for aerodynamic and aeroacoustics of bio-inspired UAV blades.

- Farzana A N, Croix N J D La and Ahmad T. DualLSBStego: Enhanced Steganographic Model Using Dual-LSB in Spatial Domain Images. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering and Systems 2025, 18, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Du R, Li F and Sun J. Bioinspiration of the vein structure of dragonfly wings on its flight characteristics. Microsc Res Tech 2022, 85, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun J and Bhushan, B. The structure and mechanical properties of dragonfly wings and their role on flyability. Comptes Rendus - Mecanique 2012, 340, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Gao K and Wu Z. Bio-inspired flapping wing design via a multi-objective optimization approach based on variable periodic Voronoi tessellation. Int J Mech Sci 2025, 291–292.

- Liu Q, Zhu C, Ru W and Hu Y. Dragonfly morphology-inspired wing design for enhanced micro-aircraft performance. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2025, 47.

- De Manabendra M, Sudhakar Y, Gadde S, Shanmugam D and Vengadesan S. Bio-inspired Flapping Wing Aerodynamics: A Review. J Indian Inst Sci 2024, 104, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare V and Kamle, S. Biomimicking and evaluation of dragonfly wing morphology with polypropylene nanocomposites. Acta Mechanica Sinica/Lixue Xuebao 2022, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D, Yang Z, Chen G, Xu H, Liao L and Chen W. Design and implementation of an independent-drive bionic dragonfly robot. Bioinspir Biomim 2025, 20.

- Kim S, Hsiao Y-H, Ren Z, Huang J and Chen Y. In Acrobatics at the insect scale: A durable, precise, and agile micro-aerial robot; 2025; vol. 10.

- Shang J K, Combes S A, Finio B M and Wood R J. Artificial insect wings of diverse morphology for flapping-wing micro air vehicles. Bioinspir Biomim 2009, 4.

- Liu Z, Yan X, Qi M, Zhu Y, Huang D, Zhang X and Lin L. Artificial insect wings with biomimetic wing morphology and mechanical properties. Bioinspir Biomim 2017, 12.

- Ha N S, Truong Q T, Goo N S and Park H C. Erratum: Relationship between wingbeat frequency and resonant frequency of the wing in insects (Bioinspiration and Biomimetics (2013) 8 (046008)). Bioinspir Biomim 2015, 10.

- Van Truong T, Nguyen Q V and Lee H P. Bio-inspired flexible flappingwings with elastic deformation. Aerospace 2017, 4.

- Hou D, Zhong Z, Yin Y, Pan Y and Zhao H. The Role of Soft Vein Joints in Dragonfly Flight. J Bionic Eng 2017, 14, 738–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Ochiai M, Sunami Y and Hashimoto H. Influence of Microstructures on Aerodynamic Characteristics for Dragonfly Wing in Gliding Flight. J Bionic Eng 2019, 16, 423–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood R, J. Design, fabrication, and analysis of a 3DOF, 3cm flapping-wing MAV.

- Pornsin-sirirak Tn, Lee S, Nassefr H, Grasmeyer J, Tai Y, Ho C and Keennon M. Mems Wing Technology for A Battery-Powered Ornithopter.

- Shang J K, Combes S A, Finio B M and Wood R J. Artificial insect wings of diverse morphology for flapping-wing micro air vehicles. Bioinspir Biomim 2009, 4.

- Richter C and Lipson, H. Untethered hovering flapping flight of a 3D-printed mechanical insect. Artif Life 2011, 17, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. Development and Modal Analysis of Bioinspired CNT/Epoxy Nanocomposite Mav Flapping Wings.

- Combes S A and Daniel T, L. Flexural stiffness in insect wings I. Scaling and the influence of wing venation. Journal of Experimental Biology 2003, 206, 2979–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsman C T, Goosen J F L and Van Keulen F. Design Overview of a Resonant Wing Actuation Mechanism for Application in Flapping Wing MAVs.

- Combes S A and Daniel T, L. Into thin air: Contributions of aerodynamic and inertial-elastic forces to wing bending in the hawkmoth Manduca sexta. Journal of Experimental Biology 2003, 206, 2999–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song F, Lee K L, Soh A K, Zhu F and Bai Y L. Experimental studies of the material properties of the forewing of cicada (Homóptera, Cicàdidae). Journal of Experimental Biology 2004, 207, 3035–42. [CrossRef]

- Anon. The wings of insects contain no muscles. 2000.

- Anon. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2016.

- Mishra A, Omoyeni T, Singh P K, Anandakumar S and Tiwari A. Trends in sustainable chitosan-based hydrogel technology for circular biomedical engineering: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 276.

- Guo Y, Qiao D, Zhao S, Liu P, Xie F and Zhang B. Biofunctional chitosan–biopolymer composites for biomedical applications. Materials Science and Engineering R: Reports 2024, 159.

- Aranaz I, Alcántara A R, Civera M C, Arias C, Elorza B, Caballero A H and Acosta N. Chitosan: An overview of its properties and applications. Polymers 2021, 13.

- Pokhrel S and Yadav P, N. Functionalization of chitosan polymer and their applications. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A: Pure and Applied Chemistry 2019, 56, 450–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash M, Chiellini F, Ottenbrite R M and Chiellini E. Chitosan - A versatile semi-synthetic polymer in biomedical applications. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2011, 36, 981–1014. [CrossRef]

- Saha A and Kumari, P. Effect of alkaline treatment on physical, structural, mechanical and thermal properties of Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) based sustainable green composites. Polym Compos 2023, 44, 2449–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarahmadi A, Dousti B, Karami-Khorramabadi M and Afkhami H. Materials based on biodegradable polymers chitosan/gelatin: a review of potential applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024, 12.

- Rubentheren V, Ward T A, Chee C Y and Nair P. Physical and chemical reinforcement of chitosan film using nanocrystalline cellulose and tannic acid. Cellulose 2015, 22, 2529–41. [CrossRef]

- De Carli C, Aylanc V, Mouffok K M, Santamaria-Echart A, Barreiro F, Tomás A, Pereira C, Rodrigues P, Vilas-Boas M and Falcão S I. Production of chitosan-based biodegradable active films using bio-waste enriched with polyphenol propolis extract envisaging food packaging applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 213, 486–97.

- Kulkarni N D, Saha A and Kumari P. The development of a low-cost, sustainable bamboo-based flexible bio composite for impact sensing and mechanical energy harvesting applications. J Appl Polym Sci 2023, 140.

- Sahu M, Hajra S, Jadhav S, Panigrahi B K, Dubal D and Kim H J. Bio-waste composites for cost-effective self-powered breathing patterns monitoring: An insight into energy harvesting and storage properties. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2022, 32.

- Ilyas R A, Asyraf M R M, Rajeshkumar L, Awais H, Siddique A, Shaker K, Nawab Y and Wahit M U. A review of bio-based nanocellulose epoxy composites. J Environ Chem Eng 2024, 12.

- Kumar S and Saha, A. Utilization of coconut shell biomass residue to develop sustainable biocomposites and characterize the physical, mechanical, thermal, and water absorption properties. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024, 14, 12815–12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni N D and Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda fiber-micro particle reinforced hybrid green composite: A sustainable solution for tomorrow’s challenges in construction and building engineering. Constr Build Mater 2024, 441.

- Kumar S and Saha, A. Graphene nanoplatelets/organic wood dust hybrid composites: physical, mechanical and thermal characterization. Iranian Polymer Journal (English Edition) 2021, 30, 935–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowska A, Rydzkowski T and Laskowska D. Wood-based composite materials in the aspect of structural new generation materials. Recognition research. Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Technical Sciences 2024, 72.

- Czarnecka-Komorowska D, Wachowiak D, Gizelski K, Kanciak W, Ondrušová D and Pajtášová M. Sustainable Composites Containing Post-Production Wood Waste as a Key Element of the Circular Economy: Processing and Physicochemical Properties. Sustainability 2024, 16.

- Saha A and Kumari, P. Functional fibers from Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) and their potential for reinforcing biocomposites. Mater Today Commun 2022, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S F, Shen L, Zhang W De and Tong Y J. Preparation and mechanical properties of chitosan/carbon nanotubes composites. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 3067–72. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi M, Ishak M R and Sultan M T H. Exploring Chemical and Physical Advancements in Surface Modification Techniques of Natural Fiber Reinforced Composite: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Natural Fibers 2024, 21.

- Bhowmik S, Kumar S and Mahakur V K. Various factors affecting the fatigue performance of natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites: a systematic review. Iranian Polymer Journal (English Edition) 2024, 33, 249–71. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni N D, Kumar M and Kumari P. The structural, dielectric, and dynamic properties of NaOH-treated Bambusa tulda reinforced biocomposites—an experimental investigation. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023.

- Saha A, Kulkarni N D, Kumar M and Kumari P. The structural, dielectric, and dynamic properties of NaOH-treated Bambusa tulda reinforced biocomposites—an experimental investigation. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023.

- Saha A, Kumar S and Zindani D. Investigation of the effect of water absorption on thermomechanical and viscoelastic properties of flax-hemp-reinforced hybrid composite. Polym Compos 2021, 42, 4497–516. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumar S and Zindani D. Investigation of the effect of water absorption on thermomechanical and viscoelastic properties of flax-hemp-reinforced hybrid composite. Polym Compos 2021, 42, 4497–516. [CrossRef]

- Khare, V.; Kamle, S. Biomimicking and evaluation of dragonfly wing morphology with polypropylene nanocomposites. Acta Mechanica Sinica/Lixue Xuebao 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen J S, Chen J Y and Chou Y F. On the natural frequencies and mode shapes of dragonfly wings. J Sound Vib 2008, 313, 643–654. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhang X, Wang K, Gan Z, Liu S, Liu X, Jing Z, Cui X, Lu J and Liu J. Effect of Blood Circulation in Veins on Resonance Suppression of the Dragonfly Wing Constructed by Numerical Method. J Bionic Eng 2024, 21, 877–891. [CrossRef]

- Kumar D, Mohite P M and Kamle S. Dragonfly Inspired Nanocomposite Flapping Wing for Micro Air Vehicles. J Bionic Eng 2019, 16, 894–903. [CrossRef]

- Rubentheren V, Ward T A, Chee C Y and Tang C K. Processing and analysis of chitosan nanocomposites reinforced with chitin whiskers and tannic acid as a crosslinker. Carbohydr Polym 2015, 115, 379–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman D J S and Wootton R J. In An Approach to the Mechanics of Pleating in Dragonfly Wings; 1986; vol. 125.

- Jongerius S R and Lentink, D. Structural Analysis of a Dragonfly Wing. Exp Mech 2010, 50, 1323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun J and Bhushan, B. The structure and mechanical properties of dragonfly wings and their role on flyability. Comptes Rendus - Mecanique 2012, 340, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Elwakeel K Z, Mohammad R M, Alghamdi H M and Elgarahy A M. Hybrid adsorbents for pollutants removal: A comprehensive review of chitosan, glycidyl methacrylate and their composites. J Mol Liq 2025, 426.

- Aranaz I, Alcántara A R, Civera M C, Arias C, Elorza B, Caballero A H and Acosta N. Chitosan: An overview of its properties and applications. Polymers 2021, 13.

- Gairola S, Sinha S and Singh I. Improvement of flame retardancy and anti-dripping properties of polypropylene composites via ecofriendly borax cross-linked lignocellulosic fiber. Compos Struct 2025, 354.

- Gairola S, Sinha S and Singh I. Improvement of flame retardancy and anti-dripping properties of polypropylene composites via ecofriendly borax cross-linked lignocellulosic fiber. Compos Struct 2025, 354.

- Gairola S, Sinha S and Singh I. Improvement of flame retardancy and anti-dripping properties of polypropylene composites via ecofriendly borax cross-linked lignocellulosic fiber. Compos Struct 2025, 354.

- Sharma R, Mehrotra N, Singh I and Pal K. Development and characterization of PLA nanocomposites reinforced with bio-ceramic particles for orthognathic implants: Enhanced mechanical and biological properties. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 282.

| Sl. No. | Sample Name | Chitosan (%) (w/v) | Treated Wood Particle (%) (w/v) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2C_0W | 2 | 0 |

| 2. | 2C_0.5W | 2 | 0.5 |

| 3. | 2C_1W | 2 | 1.0 |

| 4. | 2C_1.5W | 2 | 1.5 |

| 5. | 2C_2W | 2 | 2.0 |

| 6. | 2.5C_0W | 2.5 | 0 |

| 7. | 2.5C_0.5W | 2.5 | 0.5 |

| 8. | 2.5C_1W | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| 9. | 2.5C_1.5W | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| 10. | 2.5C_2W | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| Sl. No. | Matrix | Reinforcement | Tensile modulus (GPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Storage Modulus at 1Hz (GPa) | Damping factor at 1Hz | Natural Frequency (Hz) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Chitosan | Wood particle | 1.41 | 48.79 | 3.17 | 0.123 | 40 | Present study (2.5C_1.5W) |

| 2. | PP | Carbon Nanotubes | 1.31 | 24 | 2 | 0.046 | 29.4 | [66] |

| 3. | PP | MWCNT–COOH | 1.2 | 24.5 | 3 | 0.1 | 23.19 | [18] |

| 4. | Chitosan | Nanocrystalline cellulose | 1.5 | 57.2 | -- | -- | -- | [67] |

| 5. | Natural wing | 1.5 | -- | -- | -- | -- | [68] | |

| 6. | Natural wing | 3.75 | -- | -- | -- | -- | [69] | |

| 7. | Natural wing | 2.74 | -- | -- | -- | -- | [70] |

| Sample name | Stage-I mass loss (%) | Stage-II mass loss (%) | Stage-III mass loss (%) | MRDT (°C) | Residual Mass (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2C_0W | 13.5 | 44.0 | 25.7 | 268.1 | 35.9 |

| 2C_1.5W | 7.7 | 42.5 | 19.4 | 269.4 | 42.7 |

| 2.5C_0W | 11.8 | 42.8 | 23.4 | 270.6 | 38.5 |

| 2.5C_1.5W | 2.6 | 34.8 | 25.6 | 283.7 | 47.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).