1. Introduction

Amazonian fruits are a rich source of phenolic compounds, particularly flavonoids (e.g., flavanols, flavones, flavanones, and anthocyanins), phenolic acids, and lignans [

1]. These bioactive molecules are classified as secondary metabolites, synthesized through the pentose phosphate, shikimate, and phenylpropanoid pathways. Numerous studies have demonstrated their therapeutic potential, including antimicrobial and antioxidant properties [

2].

Flavonoids comprise a broad class of natural substances characterized by distinct phenolic structures, and are abundantly found in fruits, vegetables, grains, roots, teas, and wines. In biological systems, flavonoids fulfill diverse roles across microorganisms, plants, and animals. In flora, they are responsible for pigmentation and aroma, facilitating pollinator attraction and seed dispersion. Moreover, they function as allelopathic agents, defense compounds against pathogens, and detoxifying molecules. Several flavonoids exhibit antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic activities that inhibit the proliferation and spread of infectious agents [

3].

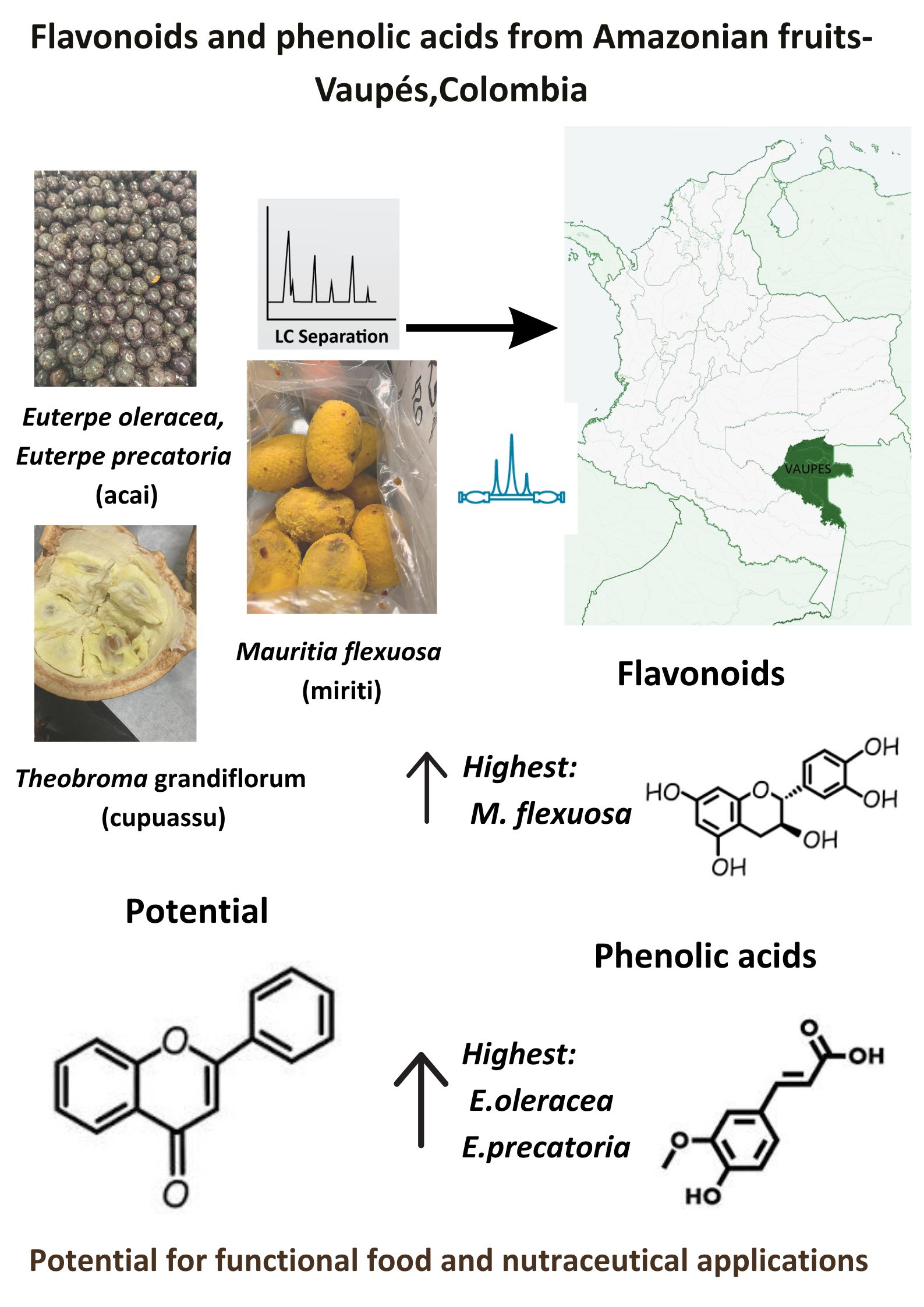

Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart. and Euterpe precatoria Mart.), mirití (Mauritia flexuosa L.), and cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum (Willd. ex Spreng.) Schum.) are native fruits of the Amazon basin. Most existing phytochemical characterizations have been conducted on Brazilian specimens. However, considering the vast geographical scope and ecological variability of the Amazon region, including differences in climate, soil, and biodiversity, it is plausible that the same species in other countries may exhibit distinct profiles and concentrations of flavonoids and phenolic constituents.

The department of Vaupés, located in the Colombian Amazon, spans over 54,000 km² and is renowned for its exceptional biological diversity and favorable environmental conditions, which support the growth of both native and introduced plant species. For centuries, indigenous communities in Vaupés have utilized açaí, mirití, and cupuassu as traditional sources of nutrition and medicine. Despite this longstanding cultural significance, scientific studies on the biochemical composition of these fruits in Colombia remain limited, underscoring the need for further research and dissemination [

4].

Açaí (

E. oleracea and

E. precatoria) is a palm native to lowland tropical regions of South America. Its fruits contain notable levels of macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, dietary fiber, lipids rich in mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids), as well as minerals such as phosphorus (P), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), and zinc (Zn). In addition, they are rich in bioactive compounds including anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and stilbenes—such as resveratrol [

5]. Several studies report therapeutic activities associated with açaí's polyphenolic content, including antiproliferative effects on HT-29 colon cancer cells, hepatoprotection against steatosis, antiplasmodial action, neuroprotective mechanisms, and anti-leukemic activity [

2].

Cupuassu (

T. grandiflorum) is native to Brazilian rainforests and has been successfully introduced into Colombia’s humid tropics. The fruit emits a distinctive aroma due to its volatile ester compounds (e.g., ethyl acetate, ethyl butanoate, ethyl propanoate, and ethyl hexanoate). Its pulp is nutritionally rich, containing carbohydrates—predominantly sucrose—and a high concentration of fatty acids such as palmitic, linoleic, and α-linolenic acids. It also provides essential micronutrients including potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and phosphorus (P) [

6]. Notably, cupuassu demonstrates significant antioxidant capacity due to its elevated content of ascorbic acid and flavonoids, mainly catechin, epicatechin, quercetin, kaempferol, among others [

7].

Mirití (

M. flexuosa) is an endemic palm of the Amazon, widely distributed across South America. Its fruits are nutritionally dense and recognized for their abundance of bioactive molecules. They contain high levels of lipids, proteins, fiber, tannins, phenolics, flavonoids, copper, and potassium. Mirití is also distinguished by its high total carotenoid content, which contributes to antioxidant potential and serves as a precursor of vitamin A. Empirical studies have demonstrated a robust positive correlation between total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in this species [

5,

8,

9].

In recent years, the scientific community has shown growing interest in the characterization of secondary metabolites due to their potential applications across food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. In this context, the primary aim of this study is to characterize the flavonoid and phenolic profiles of three Amazonian fruits—açaí, mirití, and cupuassu—from Vaupés, Colombia, using liquid chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-QqQ-MS).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Flavonoid Contents

The flavonoid and phenolic acid profiles of

Euterpe oleracea,

Mauritia flexuosa, and

Theobroma grandiflorum were analyzed using liquid chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-QqQ-MS).

Table 1 summarizes the flavonoid concentrations quantified in the fruit samples. Among the three species,

M. flexuosa exhibited the highest total flavonoid content. Notably, catechin showed the greatest average concentration (2.18 µg/g), followed by epicatechin (2.07 µg/g) and rutin (1.40 µg/g). At the individual sample level, the highest compound-specific concentrations observed were: rutin in açaí (4.4 µg/g), epicatechin in cupuassu (5.76 µg/g), and catechin in mirití (4.86 µg/g).

These findings align with previous phytochemical reports for E. oleracea and E. precatoria, which have identified flavonoids as dominant secondary metabolites. Dantas et al. (2019) documented concentrations of anthocyanins reaching 198.98 mg/100 g dry weight (DW), flavanols (including catechin and epicatechin) at 50.65 mg/100 g DW, and flavonols such as quercetin-3-glucoside, rutin, kaempferol-glucoside, and naringenin—at 10.88 mg/100 g DW.

In the case of

M. flexuosa and

T. grandiflorum, Carmona-Hernández et al. [

10] reported kaempferol concentrations of 54.43 μg/g DW and 29.4 μg/g DW, respectively. These values are consistent with additional findings that document kaempferol at 41.54 μg/g DW in

M. flexuosa and 44.8 ± 0.1 ng/g DW in the pericarp of

T. grandiflorum [

11,

12].

A total of 14 distinct flavonoids were identified in Euterpe oleracea and Euterpe precatoria (açaí) samples. In E. oleracea, rutin was the predominant compound (4.44 µg/g), followed by catechin (1.35 µg/g), luteolin (0.97 µg/g), and diosmetin (0.72 µg/g). Conversely, in E. precatoria, catechin was the most abundant (3.39 µg/g), followed by luteolin (1.23 µg/g), rutin (0.91 µg/g), and taxifolin (0.59 µg/g), while the remaining compounds were present in concentrations below 0.35 µg/g.

Previous studies have reported higher flavonoid concentrations in commercial açaí products. For instance, Costa et al. (2021) detected luteolin (2.30 ± 0.06 mg/100 g DW), taxifolin-deoxyhexose (33.1 ± 0.5 mg/100 g DW), and cyanidin-3-rutinoside (17.9 mg/100 g DW) in freeze-dried purple açaí powder. The lower concentrations reported in our study may be attributed to genotypic variability among

Euterpe species, environmental factors, or sample processing. Garzón et al. [

13] analyzed pasteurized and frozen Colombian açaí pulp and reported rutin (3.4 ± 0.7 mg/100 g DW), taxifolin (1.2 ± 0.4 mg/100 g DW), and luteolin (0.9 ± 0.3 mg/100 g DW), which are comparable to the values observed in our samples. However, our catechin and epicatechin concentrations were markedly higher, exceeding the detection thresholds established in Garzón’s study. These compounds are widely associated with antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activities [

13,

14,

15].

In

Mauritia flexuosa (mirití), 13 flavonoids were identified. Both ripe and overripe fruits shared similar compound profiles—namely catechin, taxifolin, rutin, and luteolin—but their concentrations differed notably by ripeness stage. Overripe fruits exhibited significantly higher levels: catechin reached 4.86 µg/g (vs. 0.83 µg/g in ripe fruits), rutin 1.22 µg/g (vs. 0.43 µg/g), and luteolin 1.72 µg/g (vs. 0.02 µg/g). Taxifolin concentrations remained relatively constant across stages (~0.82–0.83 µg/g). While Bataglion et al. [

11] reported markedly higher levels of catechin (961.21 ± 2.68 µg/g DW) and luteolin (1060.90 ± 6.95 µg/g DW), Tauchen et al. [

12] documented values more aligned with ours: luteolin (0.055 ± 0.00 µg/g DW) and rutin (3.998 ± 0.11 µg/g DW) from mesocarp tissues. These discrepancies may be attributable to differences in extraction protocols, as highlighted by Rodrigues do Nascimento et al. [

16], or to external factors such as photoperiod, rainfall patterns, and soil composition [

9].

In

Theobroma grandiflorum (cupuassu), 12 flavonoids were detected. Epicatechin was by far the most abundant (5.75 µg/g), followed by catechin (0.56 µg/g), while the remaining compounds were below 0.08 µg/g. Prior research has reported significantly higher values: catechin at 2.20 mg/g DW and epicatechin at 60.40 mg/g DW. Cuéllar Álvarez et al. [

17] similarly found elevated concentrations in cupuassu beans—catechin (10.06 ± 20.11 mg/g) and epicatechin (5.74 ± 5.83 mg/g). These pronounced differences can likely be attributed to variations in extraction techniques. For example, Benlloch-Tinoco et al. [

18] demonstrated that using 12 % ethanol in the extraction solvent maximizes flavonoid recovery from dehydrated pulp. In contrast, the present study employed 80 % ethanol, which may have altered the solvent polarity and thereby reduced the extraction efficiency of certain hydrophilic flavonoids.

2.2. Phenolic Acids Content

The types and concentrations of phenolic acids identified in the analyzed fruit samples are shown in

Table 2. It can be observed that the

E. oleracea and

E. precatoria exhibited the higher values of phenolic acids (612.83 μg/g and 422.35 μg/g) followed by

M. flexuosa (577.02 μg/g).

T. grandiflorum exhibited the lesser value of 17.37 μg/g. Among these, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid was the most abundant with an average concentration of 163.7 µg/g followed by ferulic acid (59.6 µg/g) and 3.5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (49.97 µg/g). The mirití sample showed the highest concentration of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid with 317.8 µg/g, followed by açaí sample species

E. oleracea with 254.3 µg/g and açaí sample species

E. precatoria with 237.0 µg/g. Previous studies have also reported the presence of p-hydroxybenzoic acid, ferulic acid, vanillic acid and syringic acid, for both açaí species fruits [

19] For mirití mesocarp samples Tauchen et al., [

12] reported the presence of ferulic acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, p-Coumaric acid among others. Results reported by Marty et al., [

20] reported the presence of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and ferulic acid in cupuassu pulp.

Phenolic acids have been associated with antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and metabolic process-modulating processes [

21].

For açaí a total of 23 phenolic acids derivatives were identified. Regarding phenolic compounds, the results for açaí indicate that for the species

E. oleracea the concentration of most compounds is higher than that found in samples of the species

E. precatoria. The concentration for 4-hydroxybenzoic acid for the species

E. oleracea was 254.3 µg/g while for the species

E. precatoria was 237.0 µg/g. In the case of 3,5 dihydroxybenzoic acid, the concentration for

E. oleracea was higher with 121.5 µg/g and for

E. precatoria was 40.1 µg/g. As well the concentration of ferulic acid for

E. oleracea was 121.52 µg/g and for

E. precatoria was 70.48 µg/g. Compared to previous studies, the concentrations of p-hydroxybenzoic acid and ferulic acid observed in the present study were higher than those reported by [

19] who documented levels of 1.80 ±0.13 mg/kg of p-hydroxybenzoic acid and 0.98 ±0.10 mg/kg of ferulic acid.

A total of 22 phenolic acid derivatives were identified in the

M. flexuosa samples. Regarding the phenolic substances, the results for the overripe stage showed that the concentration of the compounds is higher than for the ripe stage, indicating a possible increase in phenolic content as the fruit matures. The concentrations for the overripe stage range from 317.8 µg/g to 0.04 µg/g while for the ripe stage they range between 30.1 µg/g to 0.04 µg/g which demonstrates that there are significant differences in concentrations. In the case of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, the concentration was 317.8 µg/g for the overripe stage while for the ripe stage it was 9.02 µg/g. For ferulic acid, the concentration was 99.0 µg/g for the overripe stage and 6.43 µg/g for the ripe stage. Compared to previous studies, the concentration of ferulic acid was higher than those reported by [

12] who detected levels of 93.4 ±0.13 ng/g dw of ferulic acid in mesocarp of miriti. It is also notable that [

12] did not report the presence of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid in their analysis.

In the case of cupuassu, 19 phenolic derivatives were detected. The results of the phenolic compounds for cupuassu indicate that terephthalic acid was the compound with the highest concentration, 12.5 µg/g, followed by 3,5 dihydrobenzoic acid with 1.25 µg/g. The remaining compounds were present at concentrations below 0.68 µg/g. In contrast a study by Tauchen et al., [

12] in cupuassu pericarp did not detect either terephthalic acid or 3,5 dihydroxybenzoic acid. Instead, they reported the presence of other phenolic acids, including ferulic acid (76.8 ±0.2 ng/g dw, gallic acid (6.7 ±0.2 ng/g), salicylic acid (121.6 ±0.4 ng/g) and syringic acid (497.5 ±0.7 ng/g) which were detected at lower concentrations in the present study. Similarly, Marty et al., [

20] did not detect terephthalic acid or 3,5 dihydroxybenzoic acid but identified the presence of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, ferulic acid gallic acid, caffeic acid and syringic acid.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagent and Chemicals

The commercial standards for the identification and relative quantification of phenolic and flavonoid compounds were obtained from MetaSci® (Toronto, Canada). A standard solution with a concentration of 100 ppb was used for this purpose.

3.2. Collection of Fruit and Sample Preparation

Ripe açaí (E.oleracea and E.precatoria), mirití (M.flexuosa) and cupuassu (T. grandiflorum) were collected in Mitú, Vaupes, Colombia (Latitude: 1°14'54.36" N, Longitude: 70°14'24.66" W) between February and May. Selected fruits were washed and disinfected, then immersed in water at ambient temperature for 12 hours to facilitate pulp detachment. Pulp extraction was carried out using a mechanical pulper that separated seeds from the mesocarp. The resulting pulp was transferred into Falcon tubes and stored at −80 °C for 24 hours prior to freeze-drying. For T. grandiflorum pulp was manually extracted by separating it from the woody exocarp. Subsequently, it was stored in plastic bags at −80 °C for 24 hours and subjected to freeze-drying. Only the mature stages were considered for this analysis. The study was approved by the “Collection Framework granted to Universidad de los Andes by Resolution No. 002377, 2024-RCM0014-00-2024 and Addendum No. 2 of the Framework Contract for Access to Genetic Resources and Derived Products No. 288, 2020, file RGE338-2. Post- harvested fruits were placed in plastic bags and transported to the laboratory.

3.3. Extraction Procedures

Free phenolic compounds were extracted using 20 to 25 mg of lyophilized sample in 1 mL of 80% ethanol according to the procedure described by [

22]. The samples were shaken at 200 rpm for 10 minutes at 25 °C and then centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 minutes at the same temperature. The remaining pellet was subjected to alkaline hydrolysis by adding 600 µL of 4 M NaOH and ultrasound treatment for 90 minutes at 40 °C. Subsequently, acid hydrolysis was performed by adjusting the pH to approximately 2 with concentrated HCl, followed by centrifugation at 2000 g for 5 minutes at 25 °C. 1 mL of ethyl acetate was added to the supernatant and centrifuged again. Extracts of phenolic compounds, both free and bound, were evaporated in SpeedVac and resuspended in 500 µL of a mixture of methanol, acetonitrile and Milli-Q water (2:5:93, v/v).

3.4. Phenolic and Flavonoid Compound Profile by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry with a Triple Quadrupole Analyzer (LC-QqQ-MS)

Analysis of phenolic and flavonoids compounds in ripe pulps of açaí, mirití and cupuassu were carried out using an Agilent Technologies 1260® liquid Cromatography coupled to a 6470 triple quadrupole mass analyzer with electrospray ionization®. 3 μL of the sample were injected into a C18 column (InfinityLab Poroshell 120 EC-C18, 2.1 × 150 mm, 2.7 μm) at 30 °C, using a gradient elution composed of: Mobile Phase A (0.1% v/v formic acid in Milli-Q water) and Mobile Phase B (0.1% v/v acetonitrile), at a constant flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The chromatographic gradient began with 20% of Phase B, held constant for the first 6 minutes. It was then gradually increased to reach 80% of Phase B by minute 16. At that point, the conditions were maintained for an additional 4 minutes. Subsequently, the gradient returned to the initial conditions, with a re-equilibration period of 5 minutes. Mass spectrometry detection was performed in MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring) mode at 3000 V, using an ESI source in negative ionization mode. Nitrogen was used as the nebulizing gas at 50 psi, with a drying temperature of 325°C and a flow rate of 8 L/min. The sheath gas temperature was 350°C with a flow rate of 11 L/min. The collision gas used was nitrogen (99.999% purity). The programs MassHunter Acquisition (B.10.0.127), Qualitative (B.10.0.1035.0), and Quantitative (B.10.0.707.0) were used for MRM profiling. The specific MRM transitions (precursor and product ions), along with the fragmentation voltages and retention times for each analyte are presented in

Table S1.

4. Conclusions

The flavonoid and phenolic acid content in lyophilized pulp extracts of E. oleracea, E. precatoria, M. flexuosa and T. grandiflorum samples from Vaupes-Colombia using LC-Qq-MS was evaluated. The results suggest that the average of phenolic content was higher than the flavonoid content, and that the açaí and miriti samples exhibited greater values of flavonoids and phenolic acids compared to cupuassu samples. M.flexuosa exhibited the highest total flavonoid content, with catechin, epicatechin and rutin as the most abundant compounds. Notably, the ripeness stage significantly influenced flavonoid concentrations. Phenolic acid analysis revealed that E.oleracea and E.precatoria contained the highest concentrations with most of the compounds found related to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. When compared to international data, the flavonoid and phenolic acid concentration observed in Colombian samples were generally lower than those reported in Brazilian studies. These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in extraction protocols, environmental conditions, fruit maturity and genetic variability. Despite these differences, the Colombia fruits demonstrated a rich diversity of flavonoids and phenolic acids, including compounds with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. These results represent a contribution to scientific knowledge of bioactive compounds in Colombia and the Amazon region. Future research should focus on evaluating bioavailability and exploring the health benefits of these compounds in clinical settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Collision energy and transitions used in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for the determination of phenolic compounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MSR, IAG and LSP; methodology, LSP, AJML; formal analysis, MSR, LSP and AJML; investigation, MSR, IAG, AJML and LSP; resources, ER,FEL,KM,MSR; data curation, LSP,AJML; writing original draft preparation, MSR,LSP,AJML,IAG; writing-review and editing, MSR, ER; visualization, LSP,ER,FEL,KM; supervision, MSR, LSP, AJM; project administration, MSR,LSP,AJML; funding acquisition, MSR,ER,FEL,KM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sistema General de Regalías, Convocatoria No. 14 del Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación- Minciencias, under the object “Investigación y desarrollo en la identificación y selección de cadenas productivas de alto valor agregado a partir de productos forestales no maderables del Departamento del Vaupés”; executed between the Alliance made by the organizations Universidad de los Andes y la Gobernación de Vaupés.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Centro de Investigación en Metabolómica MetCore, Universidad de los Andes for the metabolomic annotation and chromatographic analysis. They also acknowledge women of AMITLI and La Libertad community in Mitú – Vaupés Colombia. The authors acknowledge GenAI tools for redaction of discussion. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. During the preparation of this manuscript the author(s) used Chat GPT for the purposes of gramary enhance. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DW |

Dry Weight |

| EO |

Euterpe oleracea |

| EP |

Euterpe precatoria |

| TG |

Theobroma grandiflorum |

| MF-OR |

Mauritia flexuosa overripe |

| MF-R |

Mauritia flexuosa ripe |

| nd |

No detection |

References

- Stafussa, A.P.; Maciel, G.M.; Bortolini, D.G.; Maroldi, W.V.; Ribeiro, V.R.; Fachi, M.M.; Pontarolo, R.; Bach, F.; Pedro, A.C.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Bioactivity and Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds from Brazilian Fruit Purees. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100066. [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Rodrigues Batista, C.; de Oliveira, M.S.; Araújo, M.E.; Rodrigues, A.M.C.; Botelho, J.R.S.; da Silva Souza Filho, A.P.; Machado, N.T.; Carvalho, R.N. Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea) Berry Oil: Global Yield, Fatty Acids, Allelopathic Activities, and Determination of Phenolic and Anthocyanins Total Compounds in the Residual Pulp. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 107, 364–369. [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Anmol, A.; Kumar, S.; Wani, A.W.; Bakshi, M.; Dhiman, Z. Exploring Phenolic Compounds as Natural Stress Alleviators in Plants- a Comprehensive Review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 133, 102383. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cortina, A.; Hernández-Carrión, M. Amazonian Fruits in Colombia: Exploring Bioactive Compounds and Their Promising Role in Functional Food Innovation. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106878. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.O.; de Souza, M.O.; Pala, D.; Freitas, R.N. Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Martius) as an Antioxidant. In Pathology; Preedy, V.R., Ed.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 127–133 ISBN 978-0-12-815972-9.

- Ramos, S.; Salazar, M.; Nascimento, L.; Carazzolle, M.; Pereira, G.; Delforno, T.; Nascimento, M.; de Aleluia, T.; Celeghini, R.; Efraim, P. Influence of Pulp on the Microbial Diversity during Cupuassu Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 318, 108465. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.L.F.; Feitosa, W.S.C.; Abreu, V.K.G.; Lemos, T. de O.; Gomes, W.F.; Narain, N.; Rodrigues, S. Impact of Fermentation Conditions on the Quality and Sensory Properties of a Probiotic Cupuassu (Theobroma Grandiflorum) Beverage. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 603–611. [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Naranjo, R.; Paredes-Moreta, J.G.; Granda-Albuja, G.; Iturralde, G.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M. Bioactive Compounds, Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant Capacity and Effectiveness against Lipid Peroxidation of Cell Membranes of Mauritia Flexuosa L. Fruit Extracts from Three Biomes in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05211. [CrossRef]

- Cândido, T.L.N.; Silva, M.R.; Agostini-Costa, T.S. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Buriti (Mauritia Flexuosa L.f.) from the Cerrado and Amazon Biomes. Food Chem. 2015, 177, 313–319. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Hernandez, J.C.; Le, M.; Idárraga-Mejía, A.M.; González-Correa, C.H. Flavonoid/Polyphenol Ratio in Mauritia Flexuosa and Theobroma Grandiflorum as an Indicator of Effective Antioxidant Action. Mol. Basel Switz. 2021, 26, 6431. [CrossRef]

- Bataglion, G.A.; da Silva, F.M.A.; Eberlin, M.N.; Koolen, H.H.F. Simultaneous Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in Buriti Fruit (Mauritia Flexuosa L.f.) by Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2014, 66, 396–400. [CrossRef]

- Tauchen, J.; Bortl, L.; Huml, L.; Miksatkova, P.; Doskocil, I.; Marsik, P.; Villegas, P.P.P.; Flores, Y.B.; Damme, P.V.; Lojka, B.; et al. Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant and Anti-Proliferative Activities of Edible and Medicinal Plants from the Peruvian Amazon. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 728–737. [CrossRef]

- Garzón, G.A.; Narváez-Cuenca, C.-E.; Vincken, J.-P.; Gruppen, H. Polyphenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Açai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) from Colombia. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 364–372. [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Azevedo, D.; Barata, P.; Soares, R.; Guido, L.F.; Carvalho, D.O. Antiangiogenic and Antioxidant In Vitro Properties of Hydroethanolic Extract from Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea) Dietary Powder Supplement. Molecules 2021, 26, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, J.T. da; Rosa, A.P.C. da; Morais, M.G. de; Victoria, F.N.; Costa, J.A.V. An Integrative Review of Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea and Euterpe Precatoria): Traditional Uses, Phytochemical Composition, Market Trends, and Emerging Applications. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113304. [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Silva, N.R.R.; Cavalcante, R.B.M.; da Silva, F.A. Nutritional Properties of Buriti (Mauritia Flexuosa) and Health Benefits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 117, 105092. [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Álvarez, L.; Cuellar-Álvarez, N.; Galeano-García, P.; Suárez-Salazar, J.C. Effect of Fermentation Time on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Potential in Cupuassu (Theobroma Grandiflorum (Willd. Ex Spreng.) K.Schum.) Beans. Acta Agronómica 2017, 66, 473–479.

- Benlloch-Tinoco, M.; Nuñez Ramírez, J.M.; García, P.; Gentile, P.; Girón-Hernández, J. Theobroma Genus: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of T. Grandiflorum and T. Bicolor in Biomedicine - ScienceDirect Available online: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co/science/article/pii/S2212429224011854 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Pacheco-Palencia, L.A.; Duncan, C.E.; Talcott, S.T. Phytochemical Composition and Thermal Stability of Two Commercial Açai Species, Euterpe Oleracea and Euterpe Precatoria. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 1199–1205. [CrossRef]

- Marty, ean-L.; Márcia Beckera, agda; Catanante, G.; Marmol, I.; s Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Mishra, R.K.; Barbosae, S.; r Nunez, O.; Silva Nunes, G. Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Antiproliferative Activity of Ten Exotic Amazonian Fruit. Journal of Food Science & Technology 5(2) (2020) 49-65 Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340917875_Phenolic_Composition_Antioxidant_Capacity_and_Antiproliferative_Activity_of_Ten_Exotic_Amazonian_Fruit_Journal_of_Food_Science_Technology_52_2020_49-65 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Leder, P.J.S.; Junior, H.P. de C.; Pantoja, L.N. da G.; Santanna, J. da S.; Oliveira, E.M. de; Sales, V.H.G. Systematic Review of Scientific Literature on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Potential of Theobroma Grandiflorum. Cuad. Educ. Desarro. 2025, 17, e8734–e8734. [CrossRef]

- MetCore, C. de M. Resultados Metabolómicos; Universidad de los Andes: Bogotá, 2025.

Table 1.

Flavonoid composition of three different amazonian fruits (μg/g fruit sample).

Table 1.

Flavonoid composition of three different amazonian fruits (μg/g fruit sample).

| Compound |

Transition (m/z) |

RT (min) |

EO1 |

EP2 |

TG3 |

MF-OR4 |

MF-R5 |

Mean |

| Flavonoids |

|

|

8.57 |

7.66 |

6.43 |

10.61 |

3.33 |

7.32 |

| (+)-Catechin (Hydrate) |

289.0 -> 245.0 |

1.32 |

1.35 |

3.39 |

0.56 |

4.86 |

0.74 |

2.18 |

| Rutin |

609.0 -> 300.1 |

1.92 |

4.44 |

0.91 |

0.005 |

1.22 |

0.43 |

1.40 |

| (-)-Epicatechin |

289.0 -> 109.0 |

1.50 |

0.33 |

0.13 |

5.75 |

|

|

2.07 |

| Luteolin |

284.9 -> 133.0 |

10.12 |

0.97 |

1.23 |

0.003 |

1.72 |

0.02 |

0.79 |

| (+)-Taxifolin |

303.0 -> 285.0 |

3.18 |

0.19 |

0.59 |

0.08 |

0.82 |

0.83 |

0.50 |

| (+/-)-Naringenin |

270.9 -> 150.9 |

11.37 |

0.29 |

0.34 |

nd |

0.51 |

0.55 |

0.42 |

| Diosmetin |

299.0 -> 284.1 |

11.77 |

0.72 |

0.35 |

0.001 |

0.47 |

0.01 |

0.31 |

| Kaempferol |

284.9 -> 93.1 |

11.69 |

0.04 |

0.52 |

0.01 |

0.73 |

0.04 |

0.27 |

| Morin |

301.0 -> 121.0 |

10.18 |

0.11 |

0.07 |

0.01 |

0.10 |

0.34 |

0.13 |

| Quercetin |

300.9 -> 121.0 |

10.18 |

0.10 |

0.06 |

0.004 |

0.10 |

0.32 |

0.12 |

| Apigenin |

268.9 -> 151.0 |

11.45 |

nd |

0.06 |

nd |

0.07 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

| Naringin |

579.0 -> 271.0 |

3.75 |

|

|

0.01 |

nd |

0.03 |

0.02 |

| Baicalin |

444.9 -> 269.0 |

7.79 |

0.01 |

0.004 |

0.01 |

|

|

0.01 |

| Phloridzin |

435.0 -> 273.0 |

5.89 |

0.01 |

0.002 |

nd |

0.003 |

nd |

0.01 |

| Phloretin |

273.0 -> 167.0 |

11.52 |

0.002 |

0.003 |

nd |

0.004 |

0.002 |

0.003 |

| Biochanin A |

282.9 -> 268.0 |

14.13 |

|

|

0.001 |

|

|

- |

| Hesperidin |

609.0 -> 301.0 |

4.28 |

|

|

nd |

|

|

- |

Table 2.

Phenolic acids composition of three different amazonian fruits (μg/g fruit sample).

Table 2.

Phenolic acids composition of three different amazonian fruits (μg/g fruit sample).

| Compound |

Transition (m/z) |

RT

(min) |

EO1

|

EP2

|

TG3

|

MF-OR4

|

MF-R5

|

Mean |

| Phenolic acids |

|

|

612.83 |

422.35 |

17.37 |

577.02 |

74.12 |

340.74 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid |

137.0 -> 93.0 |

1.64 |

254.34 |

237.02 |

0.49 |

317.83 |

9.02 |

163.74 |

| Ferulic acid |

193.0 -> 134.0 |

2.94 |

121.52 |

70.48 |

0.60 |

98.98 |

6.43 |

59.60 |

| 3.5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |

152.9 -> 108.9 |

1.20 |

122.16 |

40.14 |

1.25 |

56.25 |

30.06 |

49.97 |

| Vanillic acid |

167.0 -> 151.9 |

1.78 |

29.77 |

32.61 |

0.68 |

45.19 |

6.31 |

22.91 |

| p-Coumaric acid |

163.0 -> 119.0 |

2.52 |

53.99 |

15.68 |

0.26 |

22.29 |

1.15 |

18.67 |

| Terephthalic acid |

165.0 -> 121.0 |

1.66 |

11.24 |

9.32 |

12.48 |

12.73 |

15.57 |

12.27 |

| Sinapic acid |

223.0 -> 193.0 |

2.80 |

6.30 |

8.60 |

0.09 |

12.13 |

0.65 |

5.55 |

| Syringic acid |

197.0 -> 182.0 |

1.74 |

2.90 |

5.62 |

0.54 |

7.89 |

1.48 |

3.68 |

| Caffeic acid |

179.0 -> 135.0 |

1.67 |

4.84 |

1.07 |

0.03 |

1.51 |

1.22 |

1.73 |

| 4-Acetocatechol |

151.0 -> 108.0 |

1.75 |

1.39 |

0.33 |

0.01 |

0.44 |

0.11 |

0.45 |

| 2.3.4-Trihydroxybenzoic acid |

168.9 -> 150.9 |

1.29 |

0.86 |

0.34 |

nd |

0.47 |

0.46 |

0.53 |

| Chlorogenic acid |

353.0 -> 191.0 |

1.20 |

1.38 |

0.05 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.24 |

0.37 |

| Salicylic acid |

137.0 -> 93.0 |

5.53 |

0.43 |

0.20 |

0.13 |

0.23 |

0.12 |

0.23 |

| trans-2-Hydroxycinnamic acid |

163.0 -> 119.0 |

4.80 |

0.44 |

0.11 |

0.43 |

0.09 |

nd |

0.27 |

| Gallic acid |

169.0 -> 125.0 |

1.01 |

0.13 |

0.10 |

0.07 |

0.15 |

0.55 |

0.20 |

| Hydroferulic acid |

195.0 -> 136.0 |

2.60 |

0.32 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.15 |

0.16 |

0.15 |

| Dihydrocaffeic acid |

180.9 -> 136.9 |

1.56 |

0.22 |

0.16 |

0.13 |

nd |

0.07 |

0.15 |

| Gentisic acid |

153.0 -> 108.0 |

1.74 |

0.09 |

0.10 |

nd |

0.16 |

0.15 |

0.12 |

| 2.4-Dihydroxybenzoic Acid |

153.0 -> 109.0 |

2.05 |

0.12 |

0.08 |

nd |

0.12 |

0.04 |

0.09 |

| Acetylphloroglucinol |

167.0 -> 123.0 |

3.89 |

nd |

0.10 |

nd |

0.13 |

0.14 |

0.12 |

| m-Coumaric acid |

163.0 -> 119.0 |

3.44 |

0.12 |

0.09 |

0.04 |

0.11 |

nd |

0.09 |

| 2.3-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |

153.0 -> 109.0 |

2.05 |

0.18 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.06 |

| 3.4.5-Trimethoxycinnamic acid |

237.0 -> 102.9 |

9.42 |

|

|

nd |

nd |

0.16 |

0.16 |

| m-Hydrocoumaric acid |

165.0 -> 121.0 |

2.90 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

nd |

0.04 |

nd |

0.05 |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester |

283.0 -> 135.0 |

14.12 |

nd |

nd |

0.005 |

|

|

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).